Summary

Aims

To evaluate whether visual field impairment (VFI) can predict stroke recurrence in patients with vertebral‐basilar (VB) stroke.

Methods

A total of 326 patients were eligible for a VFI evaluation within 1 week of stroke onset. One‐year follow‐up data were obtained after VB stroke and other vascular events. All predictors were determined using Cox regression models.

Results

The overall incidence of recurrent VB stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) was 29% (n = 92). After multivariate adjustment, severe and moderate VFI were predictors of recurrent VB stroke and TIA.

Conclusions

VFI is an independent predictor of recurrent VB stroke and TIA.

Keywords: posterior circulation, prognosis, stroke, transient ischemic attack, vertebral‐basilar stroke, visual field impairment

1. INTRODUCTION

Posterior circulation territory or vertebral‐basilar (VB) stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) accounts for 20% of all strokes.1 The probability of recurrent VB stroke is lower than that for anterior circulation stroke; thus, VB stroke studies have received less attention than carotid artery disease studies. However, for VB stroke, recent studies demonstrated a high early risk of recurrence.2, 3

Some researches about prediction of recurrent ischemic stroke are based on plaque morphology4 and small vessel.5 In addition, the eyes are embryological extension of the central nervous system (CNS) and can be detected easily. They have many similar neurophysiological properties to the cerebral cortex. Changes in the retinal vasculature have been studied as a biomarker for stroke.6 Furthermore, visual field impairment (VFI) has been extensively studied in patients with neurological diseases, such as multiple sclerosis,7 brain tumor,8 and stroke.9, 10, 11, 12 Approximately 8%‐67% of patients with ischemic stroke or TIA experience VFI before or after symptom onset. Moreover, the visual symptoms vary widely; some experience blurred vision, reading difficulty, and diplopia, while others have no visual symptoms.13 Previous studies have focused on characterizing the many types of VFI, such as homonymous hemianopia in which patients have lost the same half of the bilateral visual field (VF),14, 15, 16 quadrantanopia, constricted VF, scotomas, and altitudinal defects.17 Few studies showed a link between VFI and stroke prognosis,18 and none evaluated whether VFI was predictive of subsequent cerebrovascular events after ischemic stroke.

Our goal here was to investigate VFI in a cohort with posterior circulation ischemic stroke and TIA. Specifically, we investigate the relationship between VFI and stroke recurrence, as well as other subsequent composite vascular events, after acute posterior ischemic stroke and TIA. Further, we evaluate whether VFI can predict recurrence in patients with posterior circulation stroke in a longitudinal cohort with 1 year of follow‐up.

2. METHODS

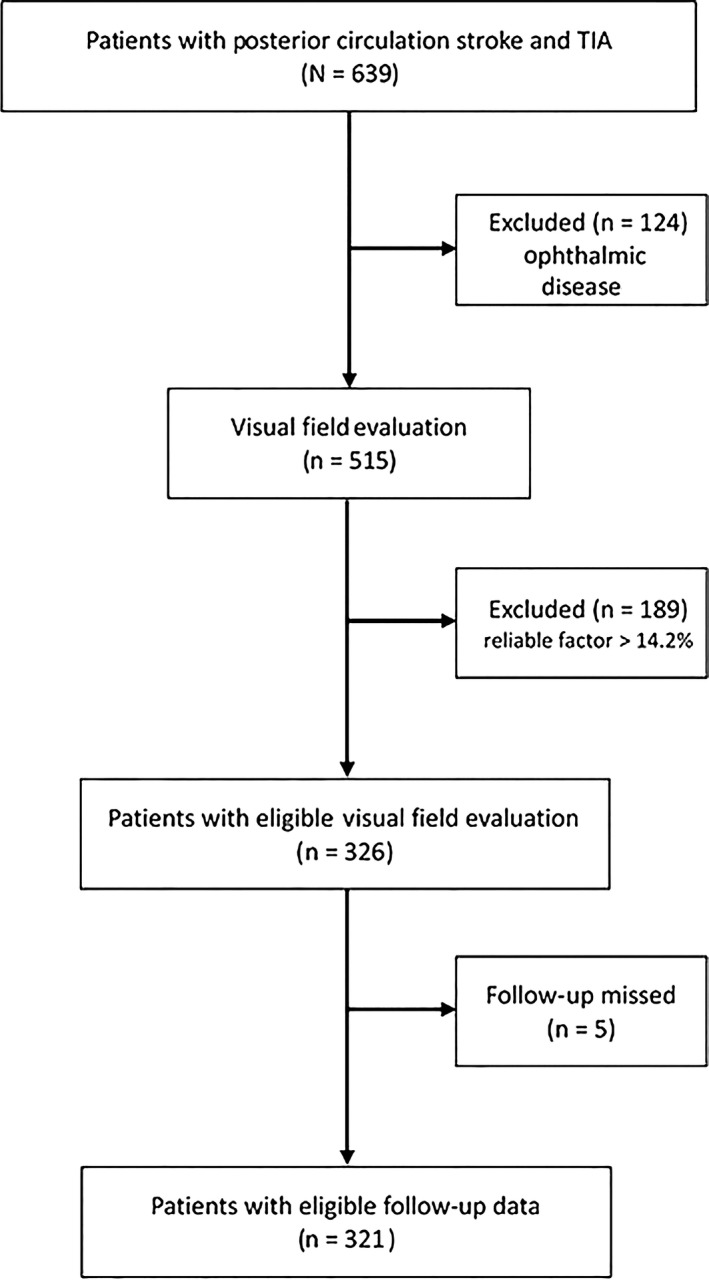

Six hundred and thirty‐nine patients were recruited in our study with acute posterior circulation stroke and TIA, who were diagnosed by clinical examination, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and diffusion‐weighted imaging (DWI). All of them involved underwent visual test, VF assessment, and follow‐up assessment. In the visual test, 124 had an aforementioned severe ophthalmic disease, 189 had a low reliable factor (>14.2%) and thus were excluded, while 326 were eligible for VF evaluation (Figure 1). Furthermore, 5 patients missed the follow‐up. Our statistical analysis involved 321 patients.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for recruitment of patients with acute posterior circulation stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA)

2.1. Study population

The present investigation was a prospective hospital‐based study that included patients who were consecutively diagnosed with an acute posterior circulation ischemia and admitted to the Neurology Department of the Beijing Tiantan Hospital between November 2014 and May 2016. On the first day after hospital admission, all patients underwent a clinical examination that included blood sampling under fasting conditions to test blood glucose concentration. Patient smoking habits were recorded as either a current or a former smoker (ie, no smoking for ≥5 years). Blood pressure was measured under standardized conditions. Arterial hypertension was defined as a history of hypertension with current antihypertensive medication treatment, or a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg, or a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a history of diabetes, or a fasting blood glucose concentration >7.0 mmol L−1, or 2 randomly examined blood glucose concentrations that were >11.1 mmol L−1. Atrial fibrillation (AF) was defined as a history of persistent AF or paroxysmal AF, based on electrocardiography and/or 24‐hour electrocardiography.

2.2. Stroke assessment

All patients had acute posterior circulation ischemia, including stroke that was defined based on the classification of the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project.19 That is, the patients had either a clinically relevant hyperintense lesion in posterior circulation brain structures such as the medulla oblongata, pons, midbrain, thalamus, and areas of temporal and occipital cortex, or a VB artery territory TIA via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) diffusion‐weighted imaging (DWI). Responsible artery stenosis degree was diagnosed by the WASID trial (Warfarin Versus Aspirin for Symptomatic Intracranial Disease) criteria, severe atherosclerotic stenosis ≥70%,moderate stenosis ≥50% and <70%,and mild stenosis <50%.20 Stroke was subtyped using the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke (TOAST) classification. For diagnosis of all patients, 2 experienced neurologists interpreted the patient imaging data; the neurologists were blinded to each other and to the patient information. In addition, median time from onset to admission, median NIHSS at admission, and antithrombotics treatment at discharge were collected for further analysis.

2.3. Visual test and VF assessment

Within 1 week of stroke onset, all patients underwent an elaborative and comprehensive examination including best‐corrected visual acuities, slit‐lamp examination, wide field fundus imaging, and eye pressure measurement. We excluded patients with strabismus, ocular motility disorder, glaucoma, diseases of the retina, glaucoma suspect, macular degeneration, or an intraocular pressure (IOP) greater than 21 mm Hg.

An experienced ophthalmologist evaluated the best‐corrected visual fields using an Octopus 900 Perimeter (Haag‐Streit, Inc., Koeniz, Switzerland) with background luminance at 31.5 apostilbs. Semi‐automatic kinetic perimetry used up to 90° white stimuli (Goldmann III 4e and V4e with a constant angular velocity of 38/s). Stimuli were presented at meridians separated by 15°. We used a reliable factor of ≤14.2%, following the recommendations of the Octopus Perimeter instruments.21 If the reliable factor was >14.2%,the test was repeated, and we excluded the patients from the study after 2 failed tests.

We quantitatively measured VFI using VF mean deviation (MD). The MD is a necessary and important index used in both the Hodapp‐Parrish‐Anderson and Brusini glaucoma staging systems.22, 23, 24 In addition, we defined the VFI scale as the Hodapp‐Parrish‐Anderson system, where none/mild VF defects are characterized by an MD of up to 6 dB (MD ≤ 6.0), moderate VF defects are characterized by an MD ranging from 6 to 12 dB (6.0 < MD ≤ 12), and severe VF defects have an MD worse than 12 dB (MD > 12). If 2 eyes of a patient were in different scales, we used the higher scale.

2.4. Follow‐up assessment

The follow‐up data that are 1 year after the first hospital discharge were obtained from the patient or direct relatives by a consultant neurologist/stroke physician who clarified and verified the presence of stroke and TIA in the VB territory as well as the composite vascular events, such as a coronary event (ie, a fatal and nonfatal angina or myocardial infarction), vascular death from stroke or myocardial infarction, and composite vascular events (ie, stroke in any arterial territory and coronary). If a recurrent stroke was suspected, the patient underwent brain computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. All patients were formally reviewed at 1 year. Patients who lost the follow‐up appointment were interviewed by phone. All patients were treated with a standard regimen of aspirin (75 mg) in combination with clopidogrel (75 mg) for 3 weeks and either one of them after 3 weeks.25 Fourteen patients with vertebral artery and subclavian artery stenosis received stenting.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (SPSS for Windows, version 17.0, Chicago, IL, USA). Cumulative incidence rates were calculated using Kaplan‐Meier estimation. Cox regression was used to examine the association between VFI and recurrence of vascular events. To adjust for potential confounders on this association, for model 1, we adjusted for age (years) and sex, and for model 2, age, sex, hypertension, smoke, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, admission NIHSS score, stenosis degree, and antithrombotics treatment were adjusted. We report the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

The baseline factors of those patients who were excluded for unable to tolerate the VF examination or too severe to finish VF examination were compared with those of patients included in this study. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups.

2.6. Ethical approval

The protocol and data collection of the study were performed in accordance with the guidelines from the Helsinki Declaration and were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Beijing Tiantan Hospital.

3. RESULTS

Among the 639 patients with acute posterior circulation stroke and TIA who were recruited between November 2014 and May 2016, 124 had an aforementioned (see Methods) severe ophthalmic disease, 189 had a low reliable factor (>14.2%) and thus were excluded, while 326 were eligible for VF evaluation (Figure 1). In addition, 5 patients missed the follow‐up. In the remaining cohort of 321 patients, the mean age ± SD was 63 ± 10 years. There was no significant difference between patients who were excluded and included in this study (Table 1). Most patients were male (71%) and had large‐vessel disease based on the TOAST classification (48%) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients excluded for unable to tolerate the VF examination or too severe to finish VF examination

| All | Excluded patientsN = 124 | Included patientsN = 326 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 63 ± 10 | 63 ± 10 | 61 ± 11 | 0.258 |

| Men, % | 71 | 70 | 71 | 0.807 |

| Hypertension, % | 48 | 50 | 47 | 0.580 |

| Diabetes, % | 18 | 18 | 18 | 0.994 |

| Atrial fibrillation, % | 16 | 15 | 16 | 0.665 |

| Smoker, % | 53 | 54 | 53 | 0.740 |

| TOAST classification, % | ||||

| Large vessel | 49 | 51 | 48 | 0.845 |

| Small vessel | 39 | 39 | 40 | |

| Cardioembolic | 9 | 8 | 9 | |

| VFI scale, % | ||||

| None/Mild | 44 | 47 | 42 | 0.577 |

| Moderate | 36 | 34 | 37 | |

| Severe | 20 | 19 | 20 | |

| Responsible artery stenosis degree, % | ||||

| None/Mild | 39 | 38 | 39 | 0.899 |

| Moderate | 36 | 38 | 36 | |

| Severe | 25 | 24 | 26 | |

| Median NIHSS at admission | 5 (3‐8) | 5 (3‐8) | 5 (3‐8) | 0.820 |

| Median time from onset to admission (d) | 4 (2‐9) | 4 (2‐8) | 4 (2‐9) | 0.538 |

| Antithrombotics treatment at discharge, % | 45 | 43 | 46 | 0.564 |

VF, visual field; VFI, visual field impairment.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the overall study cohort based on subgroups with recurrent vascular events

| All (n = 321) | VB stroke and TIA | Vascular death | Coronary events | Composite vascular events | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 92) | No (N = 229) | P | Yes (n = 20) | No (N = 301) | P | Yes (n = 23) | No (N = 298) | P | Yes (n = 110) | No (N = 211) | P | ||

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 63 ± 10 | 63 ± 11 | 62 ± 9 | 0.878 | 67 ± 9 | 62 ± 10 | 0.057 | 58 ± 10 | 63.36 ± 9 | 0.013 | 62 ± 10 | 63 ± 9 | 0.967 |

| Men, % | 71 | 69 | 73 | 0.472 | 80 | 71 | 0.376 | 52 | 73 | 0.035 | 69 | 73 | 0.520 |

| Hypertension, % | 47 | 50 | 46 | 0.501 | 50 | 47 | 0.784 | 39 | 48 | 0.430 | 45 | 48 | 0.518 |

| Diabetes, % | 18 | 17 | 18 | 0.913 | 10 | 18 | 0.525 | 30 | 17 | 0.171 | 21 | 16 | 0.286 |

| Atrial fibrillation, % | 17 | 21 | 15 | 0.205 | 15 | 17 | <0.001 | 17 | 16 | <0.001 | 21 | 14 | 0.125 |

| Smoker, % | 52 | 57 | 51 | 0.341 | 55 | 52 | 0.805 | 61 | 52 | 0.395 | 58 | 49 | 0.130 |

| TOAST classification, % | |||||||||||||

| Large vessel | 48 | 66 | 41 | 0.035 | 40 | 49 | 0.223 | 48 | 48 | 0.816 | 50 | 47 | 0.562 |

| Small vessel | 40 | 31 | 45 | 35 | 40 | 39 | 40 | 37 | 41 | ||||

| Cardioembolic | 9 | 6 | 10 | 20 | 8 | 13 | 9 | 11 | 8 | ||||

| VFI scale, % | |||||||||||||

| None/Mild | 42 | 15 | 53 | 0.005 | 15 | 44 | 0.003 | 30 | 43 | 0.459 | 27 | 50 | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 37 | 40 | 36 | 35 | 37 | 48 | 37 | 44 | 34 | ||||

| Severe | 21 | 45 | 11 | 50 | 19 | 22 | 20 | 29 | 16 | ||||

| Responsible artery stenosis degree, % | |||||||||||||

| None/Mild | 39 | 36 | 40 | 0.770 | 35 | 39 | 0.881 | 26 | 40 | 0.348 | 36 | 41 | 0.393 |

| Moderate | 36 | 37 | 35 | 35 | 36 | 48 | 35 | 34 | 36 | ||||

| Severe | 25 | 27 | 25 | 30 | 25 | 26 | 25 | 30 | 23 | ||||

| Median NIHSS at admission | 5 (3‐8) | 4 (3‐8) | 6 (3‐8) | 0.074 | 5 (2‐8) | 5 (3‐8) | 0.360 | 4 (3‐8) | 5 (3‐8) | 0.647 | 6 (3‐8) | 5 (3‐8) | 0.453 |

| Median time from onset to admission (d) | 4 (2‐9) | 5 (2‐11) | 4 (2‐8) | 0.222 | 5 (2‐7) | 4 (2‐9) | 0.980 | 5 (1‐10) | 4 (2‐9) | 0.946 | 4 (2‐9) | 4 (3‐9) | 0.426 |

| Antithrombotics treatment at discharge, % | 89 | 84 | 91 | 0.067 | 80 | 89 | 0.358 | 78 | 90 | 0.188 | 87 | 90 | 0.525 |

VB, vertebral‐basilar; VFI, visual field impairment; TIA, transient ischemic stroke; TOAST, Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke.

The overall incidence of recurrent VB stroke and TIA was 29% (n = 92), the incidence of a subsequent coronary event was 6% (n = 23), the incidence of vascular death was 6% (n = 20), and the incidence of any composite vascular event was 34% (n = 110). The TOAST classification baseline and VFI scale had a strong association with recurrent VB stroke and TIA (Table 2). In addition, responsible artery stenosis degree,median time from onset to admission, median NIHSS at admission, and antithrombotics treatment at discharge were compared between patients with and without recurrent VB stroke and TIA. There was no difference between 2 groups (Table 2).

The prevalence of normal or mild VFI, moderate VFI, and severe VFI was 42%, 37%, and 21%, respectively. Patients with severe large‐vessel stenosis were more likely to have recurrent VB stroke and TIA (HR 1.97, 95% CI 1.05‐8.32) than those with small‐vessel disease (Table 3). Patients with severe VFI (HR 4.03, 95% CI 2.02‐8.057) or moderate VFI (HR 3.20, 95% CI 1.65‐6.21) were more likely to have recurrent VB stroke and TIA.

Table 3.

Predictive value of demographic, vascular risk factors, and severity of VFI for recurrent VB stroke or TIA

| Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Stroke | P | |

| Age (years) | 1.01 (0.99‐1.03) | 0.455 |

| Men | 0.83 (0.52‐1.31) | 0.423 |

| Hypertension | 0.84 (0.53‐1.32) | 0.449 |

| Diabetes | 0.93 (0.52‐1.64) | 0.794 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.23 (0.64‐2.39) | 0.531 |

| Severity of visual field impairment | ||

| Absent/mild | Reference | |

| Moderate | 3.20 (1.65‐6.21) | 0.001 |

| Severe | 4.03 (2.02‐8.05) | 0.000 |

| TOAST classification | ||

| Small‐vessel | Reference | |

| Large‐vessel | 1.97 (1.50‐8.32) | 0.033 |

| Cardioembolic | 2.34 (0.57‐9.64) | 0.241 |

| Other etiology | 0 | |

| Unknown | 2.44 (0.49‐12.22) | 0.279 |

VFI = visual field impairment; VB = vertebral‐basilar; TOAST = Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke.

Bold indicates there is a significant correlation between recurrent rate and severity of visual field impairment or TOAST classification (P < .05).

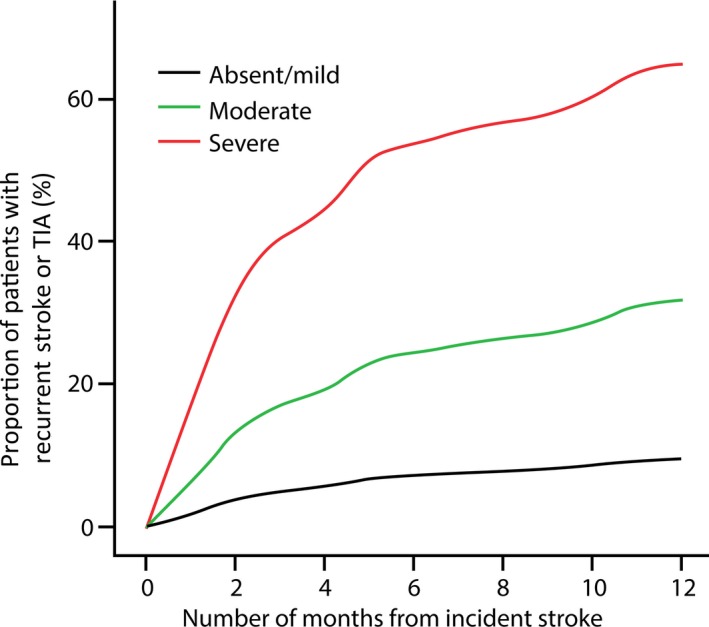

The cumulative incidence of recurrent VB stroke and TIA was 45% among patients with severe VFI, 40% among those with moderate VFI, and 15% among those with mild VFI or without VFI. After multivariate adjustment for age and sex, severe VFI (HR 4.13, 95% CI 2.01‐8.47) and moderate VFI (HR 3.25, 95% CI 1.66‐6.36) were predictors of recurrent VB stroke and TIA (Table 4). After multivariate adjustment for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and stroke subtype, severe VFI (HR 4.16, 95% CI 1.98‐8.76) and moderate VFI (HR 3.02, 95% CI 1.18‐7.73) were also predictors of recurrent VB stroke and TIA (Table 4, Figure 2).

Table 4.

Adjusted predictive value of demographic, vascular risk factors, and severity of VFI for recurrent VB stroke

| Stroke (n = 92)HR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| %a | Model 1b | Model 2c | |

| VFI | |||

| Absent/mild | 15 | Reference | |

| Moderate | 40 | 3.25 (1.66‐6.36) | 3.02 (1.18‐7.73) |

| Severe | 45 | 4.13 (2.01‐8.47) | 6.37 (2.39‐16.96) |

VFI, visual field impairment; VB, vertebral‐basilar; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Cumulative incidence.

Model 1: Cox regression adjusted for age and sex.

Model 2: Cox regression adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, smoke, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, admission NIHSS score, stenosis degree, antithrombotics treatment.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of recurrent vertebral‐basilar (VB) stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) with respect to visual field impairment (VFI) severity based on a Cox regression with adjustment for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation

4. DISCUSSION

In our prospective study of patients with acute posterior circulation stroke and TIA, VFI was an independent predictor of recurrent VB stroke and TIA. Patients with moderate or severe VFI were also more likely to have recurrent VB stroke and TIA, composite vascular events, and vascular death.

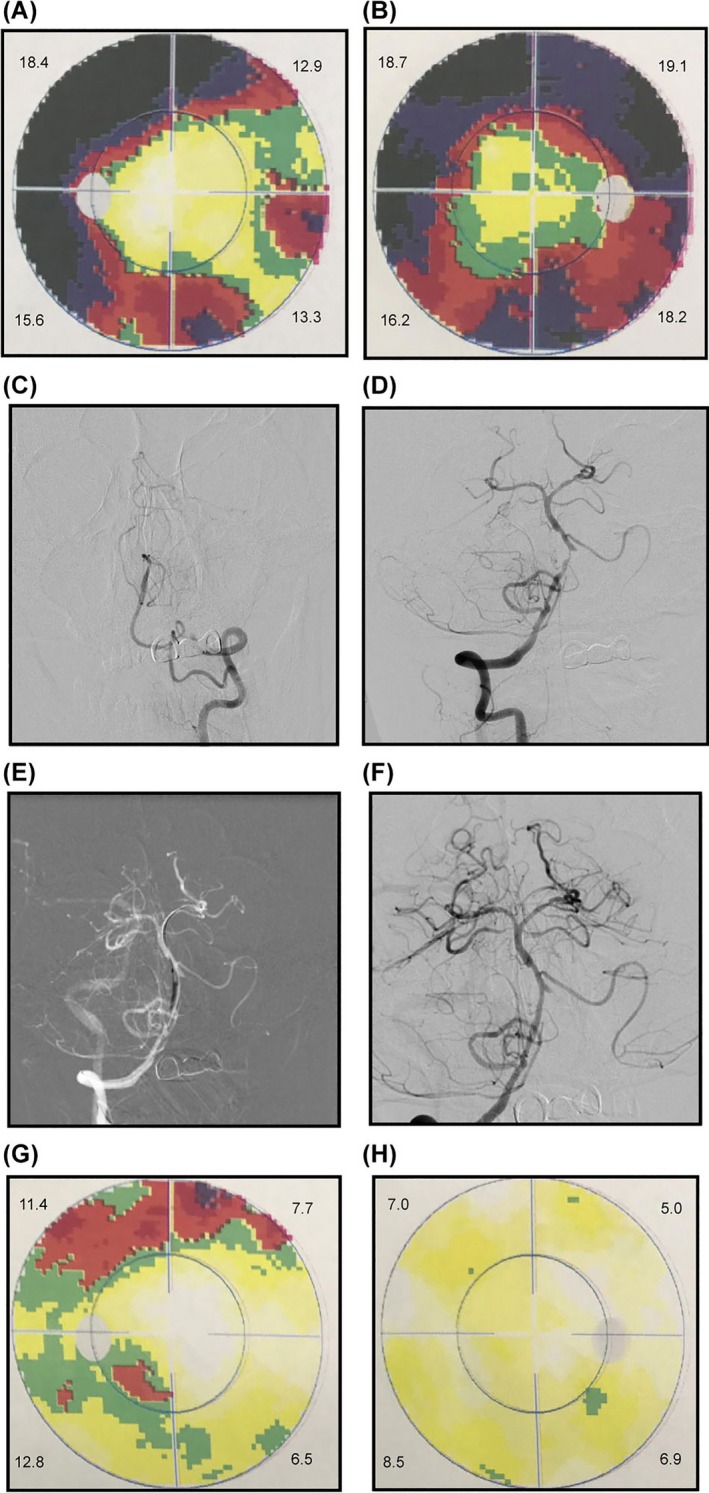

VFI after stroke profoundly influences patient quality of life.26 Afflicted patients have an increased risk of falling, difficulty in reading, depression, and higher levels of institutionalization.27, 28, 29 VFI deters the ability of patients to participate in rehabilitation, resulting in a longer recovery period. Moreover, the presence of homonymous hemianopia is related to a poor survival.18 Early studies showed that stroke‐induced VFI is associated with an occipital infarct.30, 31 A more recent study reported that 40% of the patients with VFI had occipital lobe impairment, 30% had parietal lobe impairment, 25% had temporal lobe impairment, and 5% had optic tract and lateral geniculate nucleus impairment.32 Further studies demonstrated that 54% of the patients with VFI after stroke had a lesion area in the occipital lobe, 33% in the optic radiations, and 5% with multiple pathway segment involvement.16 The posterior circulation territory or VB vessel system supplies the blood to most these areas. Patients with VFI exhibited a lower brain parenchymal volume based on MR compared to those with a normal VF and multiple sclerosis.7 In the studied cohort, 14 patients with vertebral artery and subclavian artery stenosis received stenting, and a VF examination was performed again 3 days after the operation. Ten of patients (71.43%) had a dramatically improved VF test result poststenting (Figure 3); in other words, by improving the blood supply via stenting the stenosis vessel, the pretreatment VFI can be relieved. Although the number of the patient cases receiving stenting is small, our result indicated that VFI might be related to large‐vessel stenosis in the VB territory and thus implicated the predictive value of VFI for recurrent VB stroke and TIA.33 We hypothesized that VB stenosis may cause atrophy and dysfunction of the occipital lobe, which affects visual performance. Once recanalization is successfully performed, the patient's VF can be improved rapidly, as many patients report an improvement in visual function immediately after the recanalization procedure. Such patients described their visual perception as brighter or more colorful after, than before, the procedure.

Figure 3.

A 65‐year‐old man with a history of diabetes and hypertension who presented with blurred vision. DSA revealed occlusion of the left vertebral artery (C), and severe stenosis of the intracranial vertebral artery (D). A self‐expanding stent placed (F) after balloon dilatation (E). Grayscales on left eye, MD = 14.8 (A) and right eye, MD = 17.9 (B) before procedure. Grayscales on left eye, MD = 9.4 (F) and right eye, MD = 6.9 (G) VF test result on left eye, MD = 9.4. (H) and right eye, MD = 6.9

Although case reports of vertebral stenting are common, related clinical randomized control trials are few. Some studies report that the major periprocedural vascular complication that is associated with vertebral stenting is lower for extracranial stenosis compared to intracranial stenosis.34, 35 Our results suggested that VB stroke and TIA with intracranial stenosis may particularly benefit from stenting. The Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMPRAS) trial found that for intracranial stenosis, the best medical treatment was better than stenting.36 However, a random clinical trial, the Vertebral Artery Stenting Trial (VAST), found that symptomatic vertebral artery stenosis is associated with a 5% risk of a major periprocedural vascular complication associated with stenting. Another study in China on stenting for symptomatic intracranial artery stenosis found that the 30‐day rate of stroke, TIA, and death was only 4.3%, which is acceptable.37

Our study proposed a prospective design with big sample size and good follow‐up rate. A possible relationship between recanalization of VB stenosis and VFI improvement was found, and the VFI was confirmed as an independent predictor of recurrent VB stroke and TIA. Our findings showed the potential of VF assessment in assisting earlier detection of recurrent VB stroke. It is less expensive, easier, and faster on large cohort of patients and might serve as a substitute for MRI for selected patients. For instance, our study did not include patients who were unable to tolerate the VF examination and patients with strabismus and ocular motility due to brainstem dysfunction; thus, our findings may not be applicable to patients with severe stroke, due to their poor survival prognosis. In the current study, we did not adjust for the duration and level of traditional stroke risk factors, and we did not distinguish the subtypes of recurrent strokes. These studies are currently undergoing in our center, aiming to determine whether the predictive value of VFI is associated with a specific recurrent stroke etiology in the future.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our study is the first to show that VFI is a predictor of recurrent VB stroke and TIA. Thus, patients with VB stroke and those with TIA with severe VFI have a greater probability of relapse and may need aggressive treatment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge and thank the subjects involved in the study. This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81671776, 81371290, 81471752); Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (grant numbers Z161100001116122); and Beijing Nova Program (Grant No. Z171100001117057).

Deng Y‐M, Chen D‐D, Wang L‐Y, et al. Visual field impairment predicts recurrent stroke after acute posterior circulation stroke and transient ischemic attack. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:154–161. 10.1111/cns.12787

The first two authors contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Tian‐Yi Yan, Email: yantianyi@bit.edu.cn.

Zhong‐Rong Miao, Email: zhongrongm@126.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Giles MF, Rothwell PM. Risk of stroke early after transient ischaemic attack: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:1063‐1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flossmann E, Rothwell PM. Prognosis of vertebrobasilar transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke. Brain. 2003;126:1940‐1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gulli G, Khan S, Markus HS. Vertebrobasilar stenosis predicts high early recurrent stroke risk in posterior circulation stroke and TIA. Stroke. 2009;40:2732‐2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thammongkolchai T, Riaz A, Sundararajan S. Carotid stenosis: role of plaque morphology in recurrent stroke risk. Stroke. 2017;48:e197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lau KK, Li L, Schulz U, et al. Total small vessel disease score and risk of recurrent stroke: validation in 2 large cohorts. Neurology. 2017;88:2260‐2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nguyen CT, Hui F, Charng J, et al. Retinal biomarkers provide “insight” into cortical pharmacology and disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;175:151‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ortiz‐Perez S, Andorra M, Sanchez‐Dalmau B, et al. Visual field impairment captures disease burden in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2016;263:695‐702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ogra S, Nichols AD, Stylli S, Kaye AH, Savino PJ, Danesh‐Meyer HV. Visual acuity and pattern of visual field loss at presentation in pituitary adenoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2014;21:735‐740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Falke P, Abela BM Jr, Krakau CE, et al. High frequency of asymptomatic visual field defects in subjects with transient ischaemic attacks or minor strokes. J Intern Med. 1991;229:521‐525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gilhotra JS, Mitchell P, Healey PR, Cumming RG, Currie J. Homonymous visual field defects and stroke in an older population. Stroke. 2002;33:2417‐2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang X, Kedar S, Lynn MJ, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Homonymous hemianopia in stroke. J Neuroophthalmol. 2006;26:180‐183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rowe F, Brand D, Jackson CA, et al. Visual impairment following stroke: do stroke patients require vision assessment? Age Ageing. 2009;38:188‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rowe FJ, Wright D, Brand D, et al. A prospective profile of visual field loss following stroke: prevalence, type, rehabilitation, and outcome. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:719096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pambakian AL, Wooding DS, Patel N, Morland AB, Kennard C, Mannan SK. Scanning the visual world: a study of patients with homonymous hemianopia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:751‐759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang X, Kedar S, Lynn MJ, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Natural history of homonymous hemianopia. Neurology. 2006;66:901‐905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang X, Kedar S, Lynn MJ, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Homonymous hemianopias: clinical‐anatomic correlations in 904 cases. Neurology. 2006;66:906‐910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Han SW, Sohn YH, Lee PH, Suh BC, Choi IS. Pure homonymous hemianopia due to anterior choroidal artery territory infarction. Eur Neurol. 2000;43:35‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gray CS, French JM, Bates D, Cartlidge NE, Venables GS, James OF. Recovery of visual fields in acute stroke: homonymous hemianopia associated with adverse prognosis. Age Ageing. 1989;18:419‐421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bamford J, Sandercock P, Dennis M, Burn J, Warlow C. Classification and natural history of clinically identifiable subtypes of cerebral infarction. Lancet. 1991;337:1521‐1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett‐Smith H, et al. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1305‐1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Racette L, Fischer M, Bebie H, Holló G, Johnson CA, Matsumoto C. Visual Field Digest: A guide to Perimetry and the Octopus Perimeter, 6th edn Köniz, Switzerland: Haag‐Streit AG; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hodapp E, Parrish RK, Anderson DR. Clinical Decisions in Glaucoma, 1st edn St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Susanna R Jr, Vessani RM. Staging glaucoma patient: why and how? Open Ophthalmol J. 2009;3:59‐64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Naghizadeh F, Holl G. Detection of early glaucomatous progression with octopus cluster trend analysis. J Glaucoma. 2014;23:269‐275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Y, Johnston SC, Wang Y. Clopidogrel with aspirin in minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1376‐1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jones SA, Shinton RA. Improving outcome in stroke patients with visual problems. Age Ageing. 2006;35:560‐565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leff AP, Scott SK, Crewes H, et al. Impaired reading in patients with right hemianopia. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:171‐178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ramrattan RS, Wolfs RC, Panda‐Jonas S, et al. Prevalence and causes of visual field loss in the elderly and associations with impairment in daily functioning: the Rotterdam Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1788‐1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ribeiro MV, Hasten‐Reiter Júnior HN, Ribeiro EA, Jucá MJ, Barbosa FT, Sousa‐Rodrigues CF. Association between visual impairment and depression in the elderly: a systematic review. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2015;78:197‐201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith JL. Homonymous hemianopia. A review of one hundred cases. Am J Ophthalmol. 1962;54:616‐623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schwarz MD, Li M, Tsao J, et al. Isolated homonymous hemianopia. A review of 104 cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;89:377‐381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pambakian ALM, Kennard C. Can visual function be restored in patients with homonymous hemianopia? Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:324‐328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gulli G, Marquardt L, Rothwell PM, Markus HS. Stroke risk after posterior circulation stroke/transient ischemic attack and its relationship to site of vertebrobasilar stenosis: pooled data analysis from prospective studies. Stroke. 2013;44:598‐604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eberhardt O, Naegele T, Raygrotzki S, Weller M, Ernemann U. Stenting of vertebrobasilar arteries in symptomatic atherosclerotic disease and acute occlusion: case series and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg. 2006. Jun;43:1145‐1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stayman AN, Nogueira RG, Gupta R. A systematic review of stenting and angioplasty of symptomatic extracranial vertebral artery stenosis. Stroke. 2011;42:2212‐2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:993‐1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miao Z, Zhang Y, Shuai J, et al. Thirty‐day outcome of a multicenter registry study of stenting for symptomatic intracranial artery stenosis in China. Stroke. 2015;46:2822‐2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]