Abstract

Protein and peptide oligomers are thought to play important roles in the pathogenesis of a number of neurodegenerative diseases. For this reason, considerable effort has been devoted to understanding the oligomerization process and to determining structure-activity relationships among the many types of oligomers that have been described. We discuss here a method for producing pure populations of amyloid β-protein (Aβ) of specific sizes using the most pathologic form of the peptide, Aβ42. This work was necessitated because Aβ oligomerization produces oligomers of many different sizes that are non-covalently associated, which means that dissociation or further assembly may occur. These characteristics preclude rigorous structure-activity determinations. In studies of Aβ40, we have used the method of photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins (PICUP) to produce zero-length carbon-carbon bonds among the monomers comprising each oligomer, thus stabilizing the oligomers. We then isolated pure populations of oligomers by fractionating the oligomers by size using SDS-PAGE and then extracting each population from the stained gel bands. Although this procedure worked well with the shorter Aβ40 peptide, we found that a significant percentage of Aβ42 oligomers had not been stabilized. Here, we discuss a new method capable of yielding stable Aβ42 oligomers of sizes from dimer through dodecamer.

Keywords: Amyloid β-protein, Oligomers, PICUP, Purification

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the formation of extracellular amyloid deposits formed by the amyloid β-protein (Aβ) in the brain parenchyma and vasculature and by formation of intraneuronal paired helical filaments by the protein tau [1, 2]. An important current working hypothesis of AD causation posits that Aβ oligomers are the proximate pathologic agents [3–5]. In vivo and in vitro studies have revealed a diversity of such assemblies [6, 7], including dimers [8], Aβ⋆56 [9], Aβ-derived diffusible ligands (ADDLs) [10], low molecular weight (LMW) oligomers [11], high molecular weight (HMW) oligomers [11], paranuclei [12], protofibrils [13, 14], globulomers [15, 16], and amylospheroids [17]. To establish how each of these assemblies is involved in disease causation, structure–activity correlations must be established. However, achievement of this goal has been difficult due to the complexity of Aβ assembly, the metastability of Aβ oligomers, and the polydispersity of the oligomer population [6, 18].

Bitan et al. [19] applied the method of photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins (PICUP) [20, 21] to “freeze” the oligomer equilibria and allow analytical studies of Aβ oligomerization. PICUP is a highly efficient, zero-length cross-linking method that can be applied to native (no pre facto protein modification is required) Aβ populations. Following cross-linking, monomer interchange among cross-linked oligomer species does not occur because the monomers are covalently bound to each other. This eliminates the metastability problem discussed above and allows quantitative determination of the polydispersity of the population. Bitan et al. observed that the shorter isoform of Aβ, Aβ40, and the longer isoform, Aβ42, each produced distinct oligomer distributions [12]. These oligomerization differences may explain the particularly strong linkage of Aβ42 to AD [22].

The successful application of PICUP to the problem of quantitatively determining the Aβ oligomer size distribution suggested that PICUP could be incorporated into a protocol for the production of Aβ oligomers of defined order. To do so, PICUP was combined with SDS-PAGE to separate oligomers by size and then pure populations of oligomers were produced by the extraction of the different oligomer populations from the gel matrix. The ability to produce pure populations of oligomers of specific order enabled Ono et al. to determine the structure and neurotoxic properties of pure forms of Aβ40 monomer through tetramer [23]. Subsequently, to facilitate production of large amounts of pure oligomers, a continuous flow reaction system was developed [24]. Using this system, Aβ42 structure-activity relationship determinations were initiated. Surprisingly, unlike oligomers of Aβ40, the Aβ42 oligomer populations were not entirely stable. We were able to overcome this problem by developing a sequence variant of Aβ42 [25] and a new oligomer purification protocol [26]. We present here the use of these new methods.

2. Materials

2.1. Photo-Induced Cross-Linking of Unmodified Proteins (PICUP)

40 mM (9.12 mg/ml) ammonium persulfate (APS): Use 18 MΩ/cm water (Milli-Q, Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA). Vortex to dissolve, place on ice, and use immediately thereafter.

2 mM (1.49 mg/ml) Tris (2,2′-bipyridyl)dichlororuthenium (II) hexahydrate (Ru(Bpy)) in water: Vortex to dissolve, wrap the tube in aluminum foil to protect it from light, place on ice, and use immediately thereafter.

60 mM (2.4 g/l) sodium hydroxide (NaOH) in water: The pH should be ≈11.

20 mM (2.84 g/l) sodium phosphate, dibasic buffer (Na2HPO4) in water: Adjust pH to 7.4. Store at room temperature.

5% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol in 2× sample buffer (Cat. Num. LC1676, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

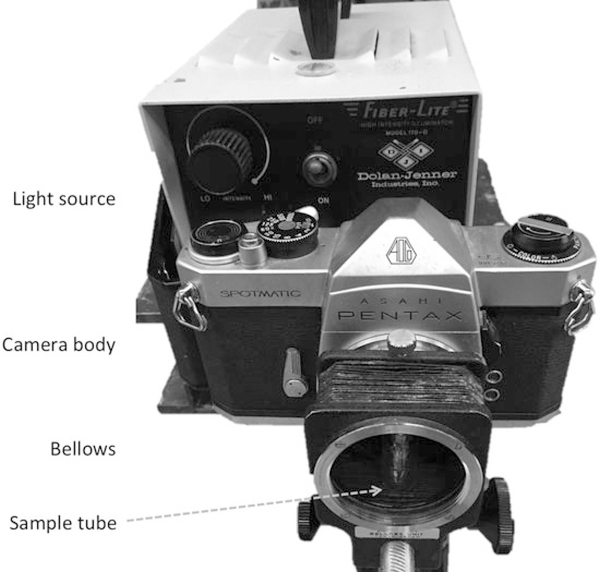

Illuminator: A 200-watt incandescent lamp (model 170-D;Dolan-Jenner, Lawrence, MA) is an appropriate light source. Any equivalent system also should be satisfactory (see Note 1 and Fig. 1).

Sonicator (model 1510R-DTH; Branson Ultrasonics or equivalent).

Fig. 1.

A typical PICUP setup. A light source is placed behind a 35 mm camera with its film compartment open. Light thus impinges upon the shutter continuously. A bellows replaces the lens of the camera. Sample tubes are placed in a glass vial (to keep the tubes upright) and the vial is placed within the bellows, which then is capped to eliminate ambient light. Photolysis is performed by opening the shutter for the desired amount of time

2.2. SDS-PAGE, Gel Staining, Electro-Elution, and Image Analysis

SDS-PAGE gel #1: 10–20% tricine gels, 1 mm thick, 12 wells (Cat. Num. EC6625BOX, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA): Store at 4°C.

Tricine SDS Running Buffer (Cat. Num. LC1675, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA): Dilute 50 ml of 10× buffer in 450 ml water. Mix thoroughly. Store at room temperature.

Mark12 unstained standard: protein standard (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA): These comprise marker proteins of 2.5–200 kDa molecular mass. Store at 4°C.

2× Tricine sample buffer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

SDS-PAGE gel #2, with Urea: 1.5 mm thick PROTEAN II xi Cell gel (Bio-Rad, Irvine, CA, USA) comprising an 18% T separating gel and a 4% stacking gel, each containing 6 M urea.

Orbital shaker: “Tabotron” orbital agitator plate (Infors AG, Bottmingen, SUI; or equivalent).

Zn stain: 200 mM imidazole and 200 mM zinc sulfate in water. Filter through a 0.22 μm pore size vacuum filter system with a polyethersulfone membrane (Corning, Corning, NY, USA).

Silver stain: Silver X-press kit (Life Technologies).

Peristaltic pump: Econo Pump, (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA) or similar variable speed pump.

Electroeluters: Model 422 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Electroelution buffer: 25 mM Tris-glycine, pH 8.4, containing192 mM glycine and 0.1% (w/v) SDS.

Power supply: Thermo Scientific, EC 150 (Waltham, MA).

Gel drying: DryEase® Mini-Gel Drying system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Densitometer: “CanoScan 9950F” (Canon, Melville, NY).

Image analysis software: Image J <http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/>.

3. Methods

The method described involves the photochemical cross-linking of multiple samples of an Aβ42 peptide containing two amino acid substitutions, pooling the resultant mixtures of cross-linked and non-cross-linked oligomers, treating the oligomer mixtures with DMSO, fractioning the oligomers by size using SDS-PAGE, negatively staining the gel with Zn/imidazole, excision and dicing of bands, re-electrophoresis of the gel pieces in a second SDS gel in the presence of 6 M urea, negatively staining the second gel with Zn/imidazole, excising the bands, electro-elution of protein from the gel pieces, and dialysis of the resulting electro-eluted material (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Method for the isolation of pure populations of cross-linked oligomers of specific size. Aβ42 is cross-linked using PICUP. DMSO (100% v/v) is added to the solution of cross-linked protein to produce a final DMSO concentration of 25%. The solution then is fractionated by SDS-PAGE. Individual oligomer bands are excised and separated on a second SDS-PAGE gel containing 6 M urea. Oligomer bands of interest are excised and their component oligomers are obtained by electro-elution, with or without dialysis. Reprinted from Hayden et al., Analytical Biochemistry, 2017, Vol. 518, Pages 78–85, with permission from Elsevier

3.1. PICUP

Dissolve ≈160 μg of [F10,Y42]Aβ42 (see Note 2) in 25 μl of 60 mM NaOH. Immediately add 112.5 μl of water and 112.5 μl of 22.2 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4 (see Note 3).

Sonicate for 1 min at room temperature (RT) (see Note 4).

Determine protein concentration by UV absorbance using ε274 = 1280 cm−1 M−1.

Adjust protein concentration to 80 μM using 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4.

For each cross-linking reaction, place 54 μl of peptide solution intoa0.2mlclear,thin-walledPCR tube.Add3μlof 2mM Tris (2,2′-bipyridyl)-dichlororuthenium (II) hexahydrate [Ru (Bpy)] and 3 μl of 40 mM ammonium persulfate. Vortex briefly.

Immediately place the tube into a small glass vial to keep it upright and insert the vial into the camera bellows in the irradiation system (Fig. 2), cap the end of the bellows, and irradiate the tube for 1 s.

Remove the tube and quench the reaction by adding 1 μl of 2-mercaptoethanol in water and then briefly vortex.

Multiple reactions may be done to produce larger amounts of cross-linked peptide. These reactions may be pooled and stored at −20 °C if subsequent experiments are not to be done immediately (see Note 5).

3.2. SDS-PAGE #1

The precast 10–20% 12-lane tricine gel is modified to create a two-lane gel. To do so, use a scalpel or equivalent device to remove the gel areas forming the sides of 11 contiguous wells. Wash the two resulting wells with running buffer and assemble the gel system.

Add 100% DMSO and 2X Tricine Sample buffer (100 μL cross-linked protein + 50 μL DMSO + 50 μL 2X Tricine Sample buffer) to yield 25% DMSO, and then heat the cross-linked oligomers at 100 °C for 10 min. Centrifuge the cross-linked oligomers briefly at RT in a microcentrifuge (16,000 × g).

Load 10 μl of the Mark 12 molecular weight markers into the small well and the mixtures of cross-linked oligomers into the large well (see Note 6).

Electrophorese at 100 V, constant voltage, until the dye front has reached the bottom of the gel (≈90 min).

Remove the gel from the gel cartridge by prying the cartridge open with a spatula or equivalent tool. Carefully detach the gel from the plate into a staining tray containing 200 M imidazole (see Note 7).

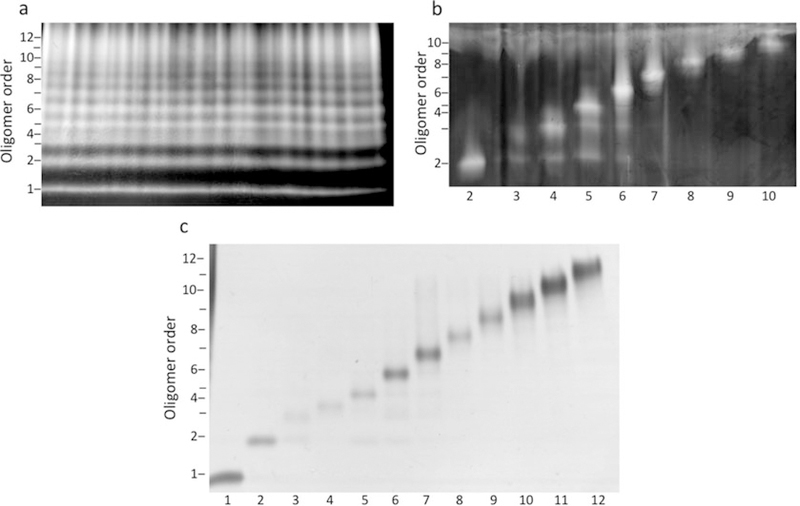

Agitate the gel using an orbital shaker at 60–70 rpm for 20 min at RT. Wash briefly with water and then visualize the bands by transferring the gel into a solution of 200 mM zinc sulfate (Fig. 3a). Stopthe staining process by placingthe gel into water.

Excise gel bands using #10 feather surgical scalpel blade and slice the bands into small rectangular pieces (e.g., 1 × 1 × 10 mm). Place the gel pieces into siliconized microcentrifuge tubes (see Note 8).

Fig. 3.

Purity of oligomers at each step of the purification procedure. (a) Cross-linked [F10,Y42]Aβ42 was treated with DMSO, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the gel was stained using the zinc/imidazole method. The zinc/imidazole is a negative stain, thus the protein bands remain translucent upon visualization. (b) Oligomer bands were excised and electrophoresed on a second SDS-PAGE, containing 6 M urea, after which the gel was stained using zinc/imidazole. Numbers below the images correspond to oligomer order (i.e., 2 is dimer, 3 is trimer, etc.). (c) Oligomer bands were excised from the urea containing gel and subjected to electro-elution. The isolated oligomers then were characterized by SDS-PAGE and silver staining. Reprinted from Hayden et al., Analytical Biochemistry, 2017, Vol. 518, Pages 78–85, with permission from Elsevier

3.3. SDS-PAGE #2

Add 200 μl of sample buffer to each tube and then heat for 10 min at 100 °C. Briefly centrifuge after heating to ensure that the gel pieces and all fluid are at the bottom of the tube.

Load the gel pieces into 1 cm wide lanes and then add 35 μl of 2 × tricine sample buffer. Add 8 μl of Mark 12 markers into one lane.

Electrophorese at 45 V for 90 min at RTand then continue the electrophoresis for 17–19 h at a voltage of 75 (see Note 9).

Following electrophoresis, stain and excise the bands asdescribed in Subheading 3.2 (Fig. 3b). Chop the bands into pieces of size ≈1.5 × 2 × 2 mm (see Note 10).

3.4. Electro-Elution

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of NIH grants AG027818, NS038328, and AG041295, the Jim Easton Consortium for Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery and Biomarkers at UCLA, and the California Department of Public Health, Alzheimer’s Disease Program, grant #07–65806.

4 Notes

The camera body/bellows system is a convenient means of precisely irradiating samples for chosen amounts of time. Any system that can accomplish the same thing can be used. The incandescent lamp provides visible light to photooxidize the Ru(II) in the Ru(Bpy) complex to Ru(III). The critical considerations here are the wavelength distribution of the light source and the photon flux. Adjustments to these parameters generally are not possible, but modification of irradiation time is a simple and effective method for optimizing cross-linking efficiency and minimizing radical damage to the protein to be cross-linked (see [19] for a complete discussion of these points).

The Aβ42 peptide used in our experiments was synthesized “in house,” as described [23]. The peptide contains two amino acid substitutions, Tyr11Phe and Ala42Tyr, that we found increased the stability of the oligomers following cross-linking, without changing peptide secondary structure, assembly kinetics, or morphology [25, 27].

The amount of material specified here is sufficient to run two gels of cross-linked material, but it can be scaled up or down to fit the needs of the user.

Insoluble material should be removed by centrifugation for15 min at 16,000 × g at RT.

It is important to do one reaction at a time. Do not add the APS and Ru(Bpy) reagents to all the tubes and then irradiate them one at a time. Only add reagents to a tube once the irradiation and quenching of the prior tube has been completed. A maximum of 54 μl per PCR tube is recommended to ensure that the entire volume is uniformly irradiated.

One gel can hold up to 400 μl of fluid in its large well. The technique will work if lower volumes are loaded. The effect simply will be that lower amounts of material will be obtained at the end of the entire process.

Fill the tray with a volume of staining solution sufficient to completely immerse the gel.

The total volume of gel pieces in a 1.5 ml tube should not exceed 500 μl so that, upon addition of 200 μl of 2× sample buffer, each gel piece is submerged in liquid. Cutting the bands carefully and accurately is critical to achieving excellent purity oligomers. The negatively stained gel should be placed on a (clean) dark background to maximize the ability to distinguish bands. The most important aspect of cutting is to ensure separation of oligomer bands. We found that cutting into the opaque regions, which do not contain protein, is not problematic so long as all of the gel pieces can carefully be placed to fit into the larger urea-containing gel wells. Diced gel pieces can be stored at −20 °C for several weeks prior to use.

To prevent excessive heating of the gel at higher voltage, it is important to cool the gel. This can be done in a variety of ways, one of which is to recirculate cold water through a cooling coil immersed in an ice bath and then through the gel apparatus.

Each electro-eluter tube should only be filled about halfway to the top with gel pieces. We found the easiest way to cut the bands accurately is to print a black and white copy of the scanned image, and encircle the outer edges of each band of interest with a thick black marker. The print with circled bands is then placed on the bench top, a clean glass plate is placed on the top of the print, and finally, the negatively stained gel is situated on the glass so that it is properly aligned with the print. Using a sharp scalpel, rectangular bands were cut following the outer edge of the encircled gel image below the glass plate. The large rectangles were cut into smaller pieces of ≈1.5 × 2 × 2 mm.

Each electro-eluter unit generally yields ≈400 μl of oligomer solution. The eluates can be used immediately in experiments if the electro-elution buffer is compatible with the buffer requirements of the experiment. Alternatively, the solutions can be buffer exchanged by dialysis or equivalent methods. Oligomer solutions may be stored at −20 °C or in an ultra cold freezer (85 C). Storage at −20 °C should be done in a freezer that does not undergo auto defrosting, as this causes freeze-thaw cycles with the potential to alter the state of the oligomers. Figure 3c shows the results of SDS-PAGE and silver staining of oligomer preparations ranging in size from dimer through dodecamer.

References

- 1.Selkoe DJ (1991) The molecular pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 6(4):487–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selkoe DJ (1994) Cell biology of the amyloid β-protein precursor and the mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Cell Biol 10:373–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haass C, Selkoe DJ (2007) Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8(2):101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirkitadze MD, Bitan G, Teplow DB (2002) Paradigm shifts in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders: the emerging role of oligomeric assemblies. J Neurosci Res 69(5):567–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ (2007) Aβ oligomers – a decade of discovery. J Neurochem 101 (5):1172–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roychaudhuri R, Yang M, Hoshi MM, Teplow DB (2009) Amyloid β-protein assembly and Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 284 (8):4749–4753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benilova I, Karran E, De Strooper B (2012) The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: an emperor in need of clothes. Nat Neurosci 15 (3):349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, Farrell MA, Rowan MJ, Lemere CA, Regan CM, Walsh DM, Sabatini BL, Selkoe DJ (2008) Amyloid-β protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med 14(8):837–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lesne S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe KH (2006) A specific amyloid-β protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature 440(7082):352–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL (1998) Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95(11):6448–6453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang T, Li S, Xu H, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ (2017) Large soluble oligomers of amyloid β-protein from Alzheimer brain are far less neuroactive than the smaller oligomers to which they dissociate. J Neurosci 37(1):152–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bitan G, Kirkitadze MD, Lomakin A, Vollers SS, Benedek GB, Teplow DB (2003) Amyloid β-protein (Aβ) assembly: Aβ40 and Aβ42 oligomerize through distinct pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100(1):330–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harper JD, Wong SS, Lieber CM, Lansbury PT (1997) Observation of metastable Aβ amyloid protofibrils by atomic force microscopy. Chem Biol 4(2):119–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh DM, Lomakin A, Benedek GB, Condron MM, Teplow DB (1997) Amyloid β-protein fibrillogenesis. Detection of a protofibrillar intermediate. J Biol Chem 272 (35):22364–22372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barghorn S, Nimmrich V, Striebinger A, Krantz C, Keller P, Janson B, Bahr M, Schmidt M, Bitner RS, Harlan J, Barlow E, Ebert U, Hillen H (2005) Globular amyloid β-peptide oligomer – a homogenous and stable neuropathological protein in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 95(3):834–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gellermann GP, Byrnes H, Striebinger A, Ullrich K, Mueller R, Hillen H, Barghorn S (2008) Aβ-globulomers are formed independently of the fibril pathway. Neurobiol Dis 30 (2):212–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoshi M, Sato M, Matsumoto S, Noguchi A, Yasutake K, Yoshida N, Sato K (2003) Spherical aggregates of β-amyloid (amylospheroid) show high neurotoxicity and activate tau protein kinase I/glycogen synthase kinase-3β. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100(11):6370–6375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teplow DB (2006) Preparation of amyloid β-protein for structural and functional studies. Methods Enzymol 413:20–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bitan G, Lomakin A, Teplow DB (2001) Amyloid β-protein oligomerization: prenucleation interactions revealed by photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins. J Biol Chem 276(37):35176–35184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fancy DA (2000) Elucidation of protein-protein interactions using chemical cross-linking or label transfer techniques. Curr Opin Chem Biol 4(1):28–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fancy DA, Kodadek T (1999) Chemistry for the analysis of protein-protein interactions: rapid and efficient cross-linking triggered by long wavelength light. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96(11):6020–6024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younkin SG (1995) Evidence that Aβ42 is the real culprit in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 37(3):287–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ono K, Condron MM, Teplow DB (2009) Structure-neurotoxicity relationships of amyloid β-protein oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106(35):14745–14750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayden EY, Teplow DB (2012) Continuous flow reactor for the production of stable amyloid protein oligomers. Biochemist 51 (32):6342–6349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamin G, Huynh TP, Teplow DB (2015) Design and characterization of chemically stabilized Aβ42 oligomers. Biochemist 54 (34):5315–5321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayden EY, Conovaloff JL, Mason A, Bitan G, Teplow DB (2017) Preparation of pure populations of covalently stabilized amyloid β-protein oligomers of specific sizes. Anal Biochem 518:78–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maji SK, Ogorzalek Loo RR, Inayathullah M, Spring SM, Vollers SS, Condron MM, Bitan G, Loo JA, Teplow DB (2009) Amino acid position-specific contributions to amyloid β-protein oligomerization. J Biol Chem 284 (35):23580–23591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]