Abstract

The synthesis and biological evaluation of semisynthetic anhydrotetracycline analogues as small molecule inhibitors of tetracycline-inactivating enzymes are reported. Inhibitor potency was found to vary as a function of enzyme (major) and substrate-inhibitor pair (minor), and anhydrotetracycline analog stability to enzymatic and non-enzymatic degradation in solution contributes to their ability to rescue tetracycline activity in whole cell E. coli expressing tetracycline destructase enzymes. Taken collectively, these results provide the framework for the rational design of next-generation inhibitor libraries en route to a viable and proactive adjuvant approach to combat the enzymatic degradation of tetracycline antibiotics.

Keywords: tetracyclines, anhydrotetracycline, tetracycline destructases, Tet(X), antibiotic resistance, inactivating enzymes, enzymology, antibiotic adjuvants, tigecycline, eravacycline, omadacycline

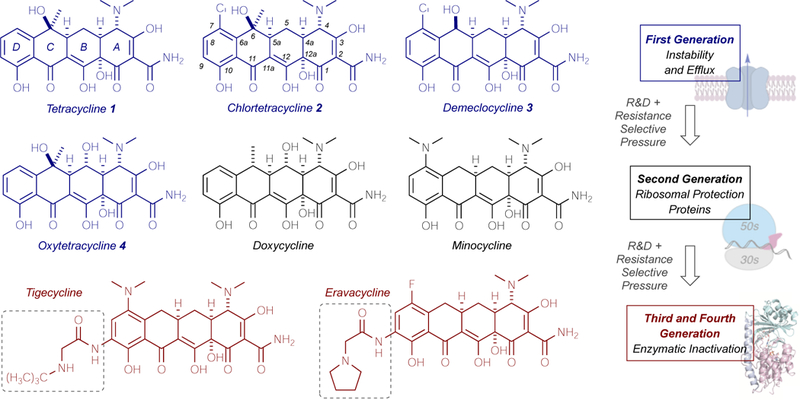

Since the isolation of chlortetracycline (2, aureomycin) from Streptomyces aureofaciens in 1948,1 the tetracycline family of broad-spectrum antibiotics has served as essential medicines for the treatment of bacterial infections in hospital and agricultural settings (Figure 1).2,3,4,5,6,7,8 Driven by challenges with stability, toxicity, and rising antibiotic resistance, the development of more effective, semisynthetic tetracycline variants has led to the introduction of next-generation tetracycline antibiotics tailored to overcome emerging resistance mechanisms.9,10,11,12 In this regard, the majority of current treatment strategies employ the use of second-generation C6-deoxy-tetracyclines (i.e. doxycycline and minocycline), which were developed to overcome efflux and stability issues,9 and third-generation glycylcyclines (tigecycline,13,14 eravacycline,15,16 and omadacycline17), which were designed to evade efflux and ribosomal protection9,18 and are used as last resort treatments for multi-drug resistant infections (Figure 1).19,20,21 While the most common, clinically relevant resistance mechanisms for tetracycline antibiotics include efflux and ribosomal protection,9,22,23 those mechanisms which facilitate intra- and extra-cellular antibiotic clearance—often through the enzymatic, irreversible inactivation of antibiotic scaffolds—frequently pervade resistance landscapes as the most efficient means of achieving resistance.24,25 Historically, the enzymatic inactivation of beta-lactam antibiotics has been well-studied,26,27,28 and strategies aimed at combatting this resistance using an adjuvant approach—where the antibiotic is co-administered with a small molecule inhibitor of the inactivating enzyme—have emerged as fundamentally useful tools for the rescue of beta-lactam antibiotics in the clinic.29,30,31,32 With the discovery and characterization of 10 tetracycline-inactivating enzymes with varying resistance profiles,33,34 the development of small molecule inhibitors of tetracycline destructase enzymes stands at the forefront of strategies aimed at combatting the imminent clinical emergence of this resistance mechanism in multi-drug resistant infections. We herein report preliminary findings focused on understanding the factors that influence inhibitor potency and stability en route to the development of viable adjuvant approaches to counter tetracycline resistance by enzymatic inactivation.

Figure 1.

Tetracycline development and parallel emergence of resistance mechanisms.

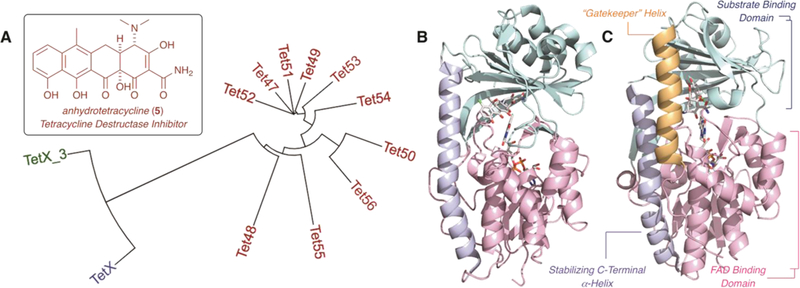

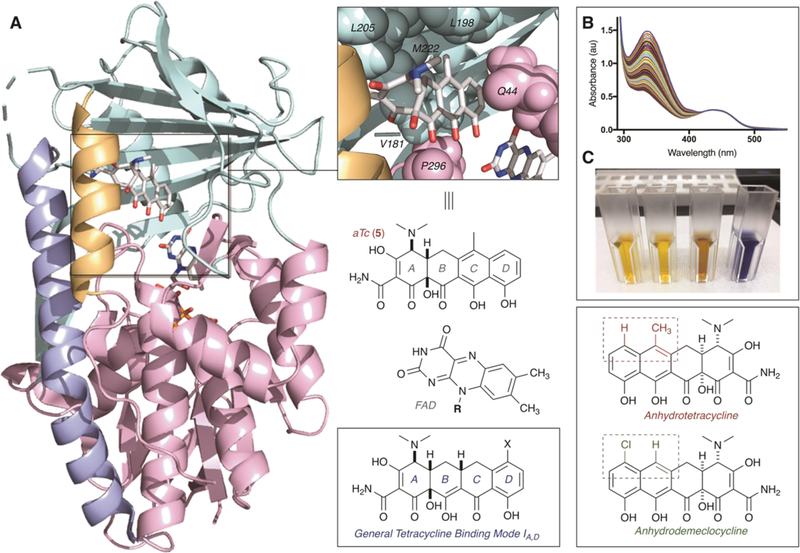

Tetracycline-inactivating enzymes, including the most studied tetracycline destructase, Tet(X),33 and the subsequently identified enzymes Tet(47)–Tet(56),34 are Class A flavin-dependent monooxygenase enzymes confirmed to confer tetracycline resistance by the non-reversible functionalization of the tetracycline scaffolds (Figure 2A). Gut-derived Tet(X) and soil-derived Tet(47)–Tet(56) possess unique three-dimensional structures which directly contribute to the observed variation in phenotypic tetracycline resistance profiles across enzyme clades (Figure 2B, 2C).35,36,37 In general, tetracycline destructase enzymes are composed of at least three functional domains: a substrate-binding domain, an FAD-binding domain, and a C-terminal alpha-helix that stabilizes the association of the two. The presence of a second C-terminal alpha-helix, termed the “Gatekeeper” helix, was also observed for the soil-derived tetracycline destructases [Tet(47)–Tet(56)] and is thought to facilitate substrate recognition and binding. 37

Figure 2.

Introduction to the tetracycline destructase family of FMO enzymes and structure of the first inhibitor, anhydrotetracycline (5). A. Phylogenetic tree [aligned with Clustal Omega and viewed using iTOL software]. B. X-ray crystal structure of chlortetracycline bound to Tet(X) (PDB ID 2y6r). C. X-ray crystal structure of chlortetracycline bound to Tet(50) (PDB ID 5tui).

A variety of substrate binding modes have been observed for TetX and the tetracycline destructases. A search for competitive inhibitors identified anhydrotetracycline (aTC, 5), a tetracycline biosynthetic precursor, as a potential broad-spectrum inhibitor (Figures 1, 2).37 aTC showed dose-dependent and potent inhibition of tetracycline destructases in vitro and rescued tetracycline antibiotic activity against E. coli overexpressing the resistance enzymes on an inducible plasmid. The crystal structure of aTC bound to Tet50 revealed a novel inhibitor binding mode that pushes the FAD cofactor out of the active site to stabilize an inactive enzyme conformation.37 Based upon these preliminary results, we crafted two hypotheses with regards to tetracycline destructase inhibition. Because of the variability observed in phenotypic resistance profiles between tetracycline destructase enzymes and phylogenetic clades, we hypothesized that inhibitor potency would also vary as a function of enzyme and inhibitor-substrate pairing; thus, a library of inhibitors may be required to preserve the viability and effectiveness of an adjuvant approach. This has proven to be the case with beta-lactam adjuvants, where multiple generations of inhibitors are required to cover the diverse families of beta-lactamase resistance enzymes (classes A–D) present in the clinic.29 In addition, we proposed that aTc, in particular, could serve as a privileged scaffold about which to design inhibitor libraries. Thus, we herein report the generation and biological evaluation of 4 semisynthetic derivatives of anhydrotetracycline as potential inhibitors of tetracycline destructase enzymes. In order to identify the factors affecting the inhibition of tetracycline-inactivating enzymes, we assessed the inhibitory activity of the aTc analog library, in reference to aTc, against the degradation of first-generation tetracyclines by three representative tetracycline destructase enzymes (Figure 1). Taken collectively, these results highlight the factors that influence inhibitor potency and stability and provide the framework for the rational design of next-generation inhibitor libraries.

Results and Discussion

Michaelis-Menten Kinetics Highlight Enzyme Differences

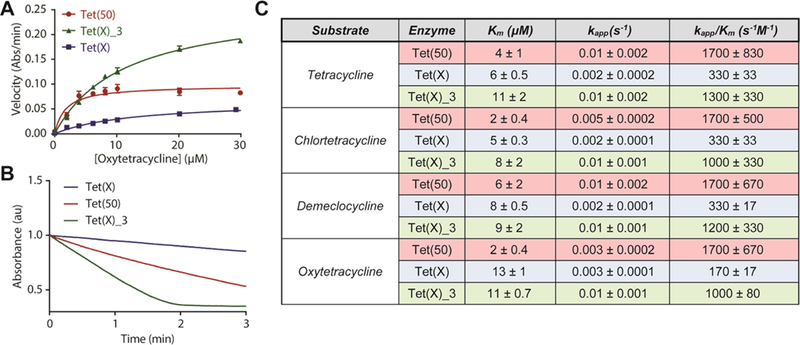

Three representative tetracycline destructase enzymes were chosen based upon observed phenotypic resistance profiles and phylogenetic clustering.34 These enzymes—soil-derived Tet(50) and gut-derived Tet(X) and Tet(X)_3 [GenBank KU547176.1]—were recombinantly expressed and purified from BL21-Star (DE3) competent E. coli. For each enzyme, the in vitro enzyme-dependent inactivation of first-generation tetracyclines was characterized using an optical absorbance kinetic assay developed in our laboratory.34,37 Apparent Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters were determined from the enzyme- and time-dependent degradation of tetracycline (1), chlortetracycline (2), demeclocycline (3), and oxytetracycline (4). Representative Michaelis-Menten plots for the enzymatic degradation of oxytetracycline are shown in Figure 3A.

Figure 3.

Michaelis-Menten kinetics of tetracycline destructase degradation of first generation tetracyclines. A. Representative Michaelis-Menten plot of tetracycline destructase degradation of oxytetracycline. B. Representative optical absorbance kinetic plots for the degradation of oxytetracycline by tetracycline destructase enzymes [as observed at 400 nm for Tet(50) and Tet(X)_3; 380 nm for Tet(X)]. C. Apparent Km, kapp, and catalytic efficiencies for the tetracycline destructase-mediated degradation of tetracycline, chlortetracycline, demeclocycline, and oxytetracycline. Error bars represent standard deviation for two independent trials.

Consistent with previous reports,37 micromolar (μM) apparent binding affinities (Km), ranging from 2 μM to 13 μM, were observed across all enzyme-substrate combinations (Figure 3). Apparent rate (kapp) of tetracycline degradation was highest for Tet(X)_3, followed closely by Tet(50), and lastly by Tet(X); this variation in apparent rate is highlighted in the deviation in shape and slope of the raw plots of enzyme-dependent tetracycline degradation, observed as the change in the absorbance at 400 nm over time (Figure 3B). Conversely, apparent catalytic efficiency (kapp/Km) was highest for Tet(50) over Tet(X)_3—due to a 2–10 fold difference in apparent Km. This trend is consistent with the hypothesis that Gatekeeper helix-facilitated substrate recognition results in an increase in substrate specificity and turnover for the soil-derived tetracycline destructases (Figure 2).37 The second, C-terminal gatekeeper helix is notably absent in X-ray crystal structures of gut-derived, canonical tetracycline-inactivating enzyme, Tet(X) (Figure 2),35 and the presence or absence of a similar helix in Tet(X)_3—which clusters closely with Tet(X)—is currently unknown. Similar apparent binding affinities (Km) were observed for phylogenetically clustered Tet(X)_3 and Tet(X), though 5- to 8-fold differences in apparent rate results in drastically different catalytic efficiencies for the two gut-derived enzymes (Figure 3C). The paradoxical functional similarities of Tet(X)_3 to both Tet(50) in apparent rate and Tet(X) in binding affinity and resistance phenotype, vide infra, has garnered interest in the unique facets of its three-dimensional structure that allows for accelerated turnover and broad substrate scope; efforts to resolve an X-ray crystal structure of Tet(X)_3 are currently on-going in our laboratories and will be reported in due course. Taken collectively, the variability in binding affinity and catalytic efficiency highlights both enzyme-to-enzyme and substrate-to-substrate differences across the tetracycline destructase family of enzymes. In this light, we hypothesized this same variability would manifest in inhibitor potency fluctuation as a function of enzyme and inhibitor-substrate pairing.

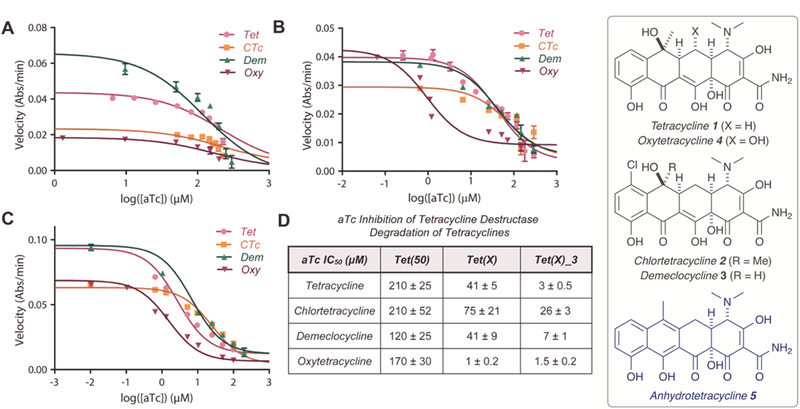

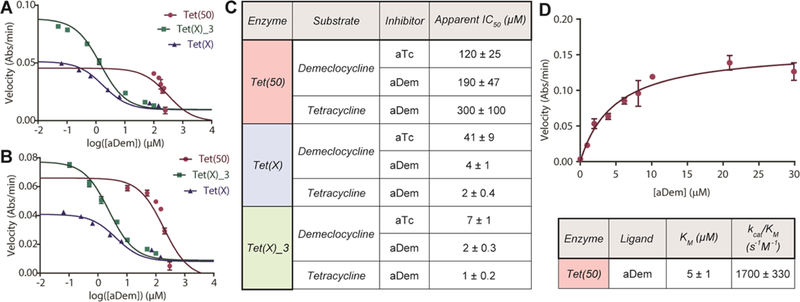

aTc Inhibitory Activity Varies as a Function of Enzyme and Antibiotic Pair

To evaluate the hypothesis that inhibitor potency will vary as a function of enzyme and antibiotic pair, we assessed the in vitro inhibitory activity of aTc against the tetracycline destructase-mediated degradation of first-generation tetracycline antibiotics, the results of which are displayed in Figure 4 (A–D). In general, the apparent half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) for the aTc inhibition of Tet(50) were higher than those observed for Tet(X) [5- to 10-fold], with the most potent inhibition observed for Tet(X)_3. Surprisingly, the apparent IC50s observed for the aTc inhibition of tetracycline destructase-mediated degradation of tetracyclines varied modestly as a function of inhibitor-substrate pair within the context of a single enzyme (Figure 4D). However, the half-maximal inhibitory concentrations of aTc inhibition of CTc were notably higher than those observed for the enzymatic degradation of the other first-generation tetracyclines. In addition, the IC50 associated with aTc inhibition of the Tet(X) degradation of oxytetracycline was over an order of magnitude lower than other aTc-tetracycline pairs for the gut-derived enzyme. It is unclear what factors contribute to this effect; however, the combination of lower binding affinity (higher Km, Figure 3C) and the polyhydroxylated nature of oxytetracycline may allow for more favorable inhibitor competition for the substrate binding pocket—since oxytetracycline may appear more Tet(X) product-like than other tetracycline substrates vide infra.33

Figure 4.

in vitro aTc inhibition of tetracycline destructase degradation of first-generation tetracycline antibiotics as observed via an optical absorbance kinetic assay. A. aTc inhibition of Tet(50) degradation of tetracyclines. B. aTc inhibition of Tet(X) degradation of tetracyclines. C. aTc inhibition of Tet(X)_3 degradation of tetracyclines. D. Apparent IC50 for aTc inhibition (denoted for each substrate and enzyme). Error bars represent standard deviation for three independent trials. All data points possess error bars, though some are not visible at the plotted scale.

Analysis of Lineweaver-Burk plots of the aTc inhibition of tetracycline destructase-mediated degradation of tetracycline support the idea of a mixed competitive/non-competitive inhibition model (Supporting Information Figure 2). Taken collectively, these results suggest that aTc inhibition involves more than a contest of competitive binding and catalytic efficiency, which is consistent with multicomponent enzyme processes and substrate/inhibitor binding mode flexibility observed for the tetracycline destructase enzymes.36,38,39,40,41,42 Consequently, because inhibition model ambiguity and binding mode flexibility can complicate broad computational docking to direct the rational design of inhibitors, direct modification of the aTc scaffold may be the most efficient way to aid in the generation of larger inhibitor libraries by determining empirical inhibitor structure-activity relationships (SAR).

Semisynthesis of aTc Analogues

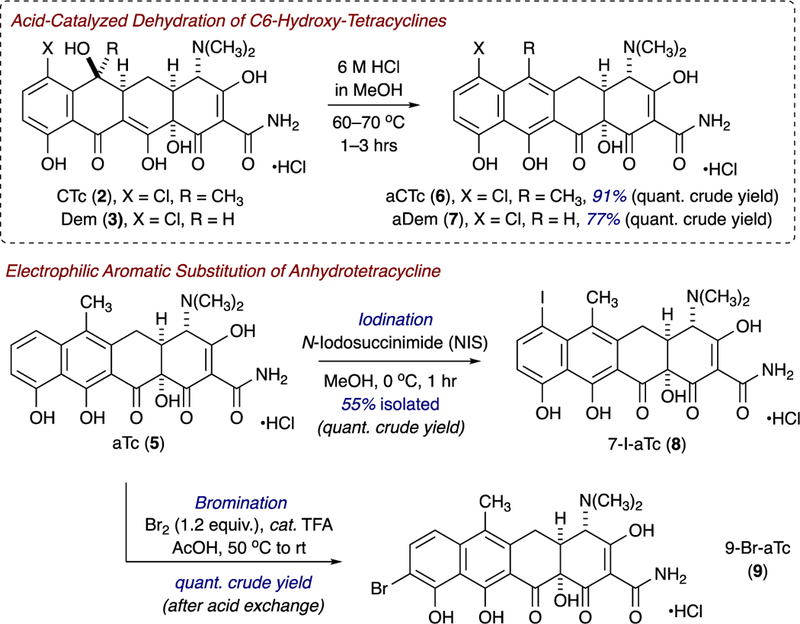

Inspired by the seminal work of Nelson and coworkers, as well as Gmeiner and coworkers, involving semisynthetic strategies to tetracycline and anhydrotetracycline analogues,43,44 we synthesized four aTc analogues from parent tetracyclines to evaluate the potential for aTc to serve as a privileged scaffold for the development of tetracycline-inactivating enzyme inhibitors. Acid-catalyzed dehydration of C6-hydroxy-tetracyclines, chlortetracycline (CTc, 2) and demeclocycline (Dem, 3), provided the corresponding anhydrotetracycline variants, anhydrochlortetracycline (aCTc, 6) and anhydrodemeclocycline (aDem, 7) in quantitative crude yields and excellent isolated yields (C18-silica gel, reverse phase preparative HPLC). Correspondingly, electrophilic aromatic substitution of anhydrotetracycline (aTc, 5) with either N-iodosuccinimide (NIS) or molecular bromine (in acid) afforded C7-iodoanhydrotetracycline (7-I-aTc, 8) and C9-Br-anhydrotetracycline (9-Br-aTc, 9) in excellent crude and isolated yields. These brightly colored solids were storable at low temperatures (−20 °C), away from light, with little decomposition observed over 6-month periods (by high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, LCMS), and stability and longevity improved when the compounds were stored at low temperature under argon atmosphere. However, triturations with methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) of analogues with trace impurities, followed by filtration, allowed for re-isolation of greater than 90–95% purity material as determined by LCMS and NMR.

Biological Evaluation of aTc Analog Library

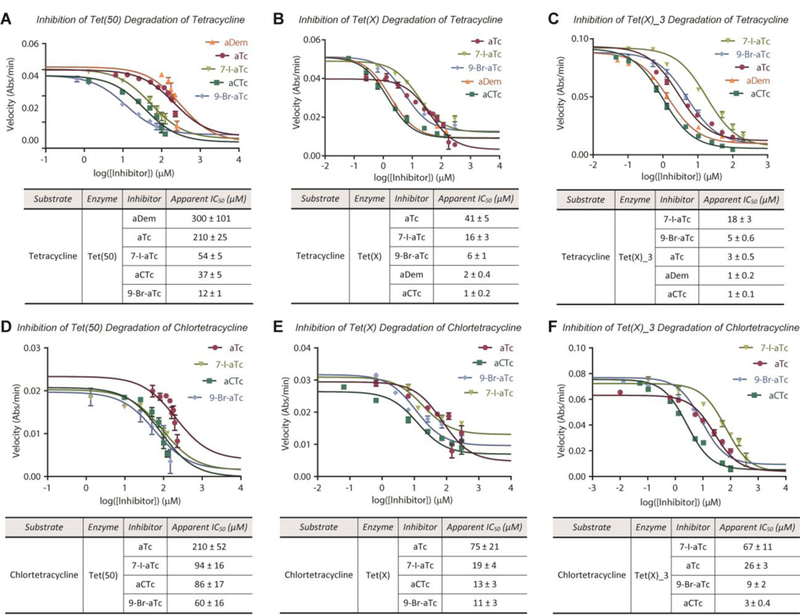

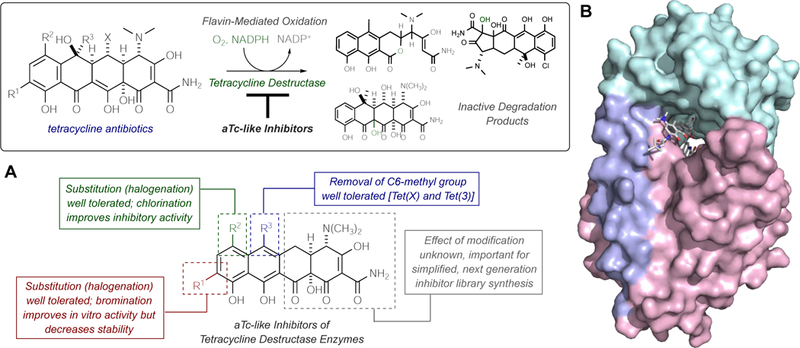

With a scalable synthetic route in hand, we evaluated the ability of the aTc analogues to inhibit tetracycline-destructase enzymes via an in vitro optical absorbance kinetic assay and referenced the results to those obtained for known inhibitor, aTc, in parallel scenarios (Figure 5). In general, inhibitor potency varied in an enzyme-dependent manner that was consistent with what was previously observed with aTC, vide supra. Apparent half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) were highest for the Tet(50)-mediated degradation of tetracycline and chlortetracycline (Figure 5A,D), followed by Tet(X) (Figure 5B,E) and Tet(X)_3 (Figure 5C,F), respectively. Inhibitor potency decreased (2- to 10-fold) when inhibitors were coadministered with CTc (Figure 5D–F) over tetracycline (Figure 5A–C), and chlorinated aTc analogs, aCTc and aDem, performed marginally better than aTC when coadministered with tetracycline, suggesting little significant cooperativity/synergism of structurally similar inhibitor-substrate pairs. In general, halogenation of the D-ring improved in vitro inhibitory activity, though the enhancement observed for C7-chlorination is more pronounced across all enzyme-antibiotic combinations. Removal of the C6-methyl group was well tolerated for the inhibition of Tet(X) and Tet(X)-homolog, Tet(X)_3; however, aDem performed poorly against tetracycline destructase Tet(50). Proposed reasoning for this phenomenon is discussed later in this report, vide infra.

Figure 5.

In vitro inhibition of tetracycline destructase degradation of first-generation tetracycline antibiotics as observed via optical absorbance kinetic assay. A. Inhibitory activity of aTc library against Tet(50) degradation of tetracycline. B. Inhibitory activity of aTc library against Tet(X) degradation of tetracycline. C. Inhibitory activity of aTc library against Tet(X)_3 degradation of tetracycline. D. Inhibitory activity of aTc library against Tet(50) degradation of chlortetracycline. E. Inhibitory activity of aTc library against Tet(X) degradation of chlortetracycline. F. Inhibitory activity of aTc library against Tet(X)_3 degradation of chlortetracycline. Error bars represent standard deviation for three independent trials. All data points possess error bars, though some are not visible at the plotted scale.

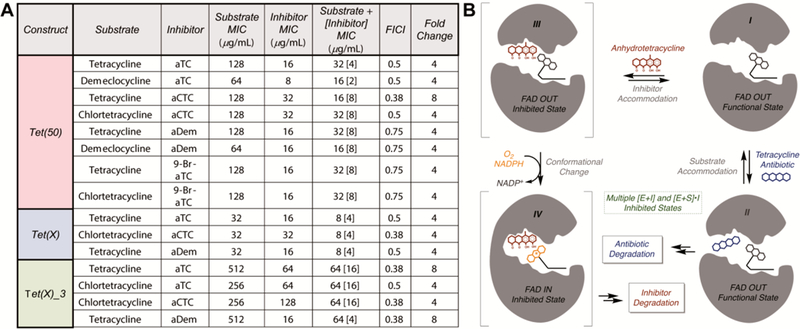

With in vitro inhibitor potencies established, we next tested the ability of the aTc analogues to rescue tetracycline activity in whole cell inhibition assays of E. coli expressing tetracycline destructase enzymes. By varying concentrations of the tetracycline-inhibitor combinations in a checkboard broth microdilution antibiotic susceptibility assay, we were able to identify the lowest concentration of inhibitor that results in at least a 4-fold change in the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the tetracycline alone; highlights of the checkerboard assay are shown in Figure 6A. Several—not all—tetracycline-inhibitor pairs showed enhanced antibiotic activity when tetracycline substrates were co-administered with small doses of various inhibitors (4- to 8-fold enhancement over antibiotic alone, Figure 6A). Notably, though aTc was, in general, the least potent of the inhibitor library, it performs well—and on par with the chlorinated analogues, aCTc and aDem—in the whole cell rescue of tetracycline activity. It is important to note that, while some of the aTc analogs possess baseline antibiotic activity alone, antibiotic synergistic killing and destructase inhibition may not be mutually exclusive (Figure 6A), and it is not entirely clear how much of a contribution is made by each mechanism for each combination. The calculated fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) is provided for reference.45 However, the enhancements in MIC observed for several anhydrotetracycline-variant/antibiotic combinations are modest yet promising, and potent in vitro destructase inhibition by each of the aTc variants—in combination with these results—suggests that whole cell adjuvant activity could be optimized in the future second generation synthesis of larger aTc-like inhibitor libraries.

Figure 6.

A. Whole cell inhibition of E. coli expressing tetracycline destructase enzymes including calculated FICI and observed fold change enhancements. B. Working model of the inhibition of tetracycline destructase enzymes by aTc-like small molecules (competitive inhibitor versus sacrificial substrate).

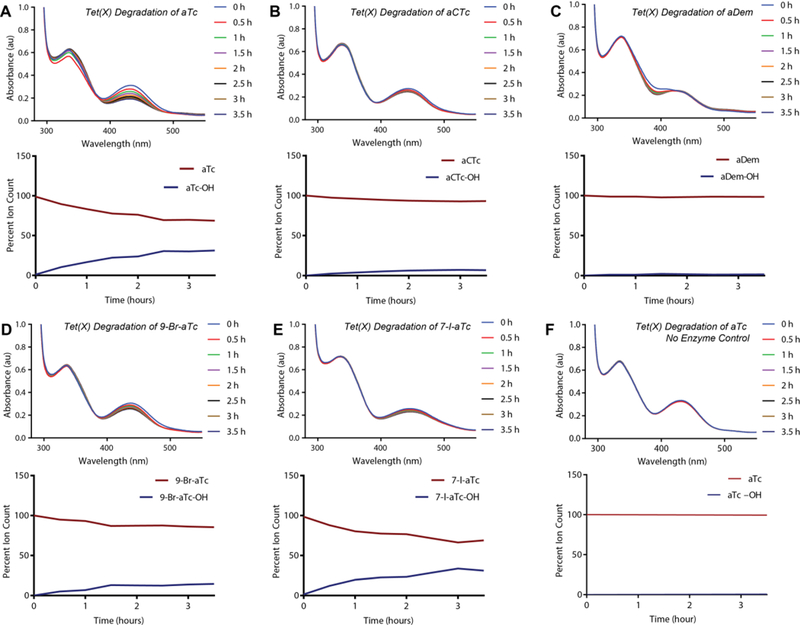

While 9-Br-aTc and 7-I-aTc possess potent in vitro destructase inhibitory activity, the analogues showed limited activity in whole cell inhibition studies, potentially due to increased instability in solution over time and/or increased reactivity toward enzymatic degradation. In particular, 7-I-aTc showed no inhibitory activity with any enzyme-antibiotic combination against whole cell E. coli expressing destructase enzymes. We hypothesized that the instability of 7-I-aTc was contributing to this phenomenon, as the non-enzymatic degradation of 7-I-aTc in solution was observed by LCMS (overnight) and during extended 13C NMR experiments. Because the o/p-substitution of phenols with heavy halogens is known to increase the rate of non-enzymatic photooxidation,46,47,48,49 the incorporation of D-ring halogens to future inhibitor libraries may be limited to chlorination and fluorination to preserve inhibitor stability. However, the Br- and I-substituents present in 7-I-aTc and 9-Br-aTc may serve as useful functional handles to access more structurally diverse and stable inhibitor scaffolds. While we propose that disparities in in vitro inhibitor potency and whole cell rescue of tetracycline activity are largely due to problems with inhibitor stability, vide infra, the potent in vitro inhibition of tetracycline destructase enzymes suggests structural modifications that promote inhibitor stability and maintain potency could improve whole cell performance.

Working Inhibition Model

The tetracycline destructase enzymes are class A flavin-monooxygenase (FMO) enzymes that catalyze NADPH- and oxygen-dependent, multicomponent transformations via a series of complex and dynamic conformational changes involving a mobile flavin cofactor.33,34,38,39 While the precise sequence of events is currently unknown, the proposed degradation process involves substrate recognition and binding to FAD-OUT enzyme conformation I (Figure 6B), followed by rapid flavin reduction (FAD to FADH2) by NADPH. Through discrete conformational changes, the reduced flavin cofactor is pushed toward the newly bound substrate and reacts with molecular oxygen to generate the reactive C4a-hydroperoxyflavin in the solvent-protected FAD-IN conformation. The hydroperoxyflavin then reacts with the tetracycline substrate,33,34,36,39 and another series of conformational changes allows for release of the degradation product and dehydration of the resultant C4a-hydroxyflavin to regenerate FAD-OUT conformer I.

Based upon the findings presented herein, in combination with previous studies,33,34,37 we developed a working model for inhibition of tetracycline destructase enzymes in the context of the proposed degradation process (Figure 6B). In the event that inhibition occurs competitively, inhibitor could bind to substrate unbound enzyme and exclude accommodation of substrate into the active site; this inhibited state (III) could be a stalled state (non-productive) or the inhibitor could react with the enzyme as a sacrificial substrate (moving through inhibited state IV and multiple successive inhibited states en route to the enzymatic degradation of the inhibitor, Figure 6B). Alternatively, inhibition could occur non-competitively, where inhibitor binds to substrate-bound enzyme complex (Intermediate II or successive substrate-bound functional enzyme states) and restrains the conformational flexibility of the enzyme to impede productive turnover. Because degradation is a complex, multicomponent process involving a number of discrete enzyme conformational changes, none of the multiple inhibited states derived from substrate-bound and substrate-unbound functional enzyme states can implicitly be excluded. Therefore, to assess the potential of the generated aTc analogues to undergo enzymatic degradation as sacrificial substrates, we chose to evaluate the in vitro degradation of the inhibitor library by canonical tetracycline-inactivating enzyme, Tet(X), which is known to degrade aTc, albeit slowly.34

aTc Analogues as Substrates for Destructase Enzymes

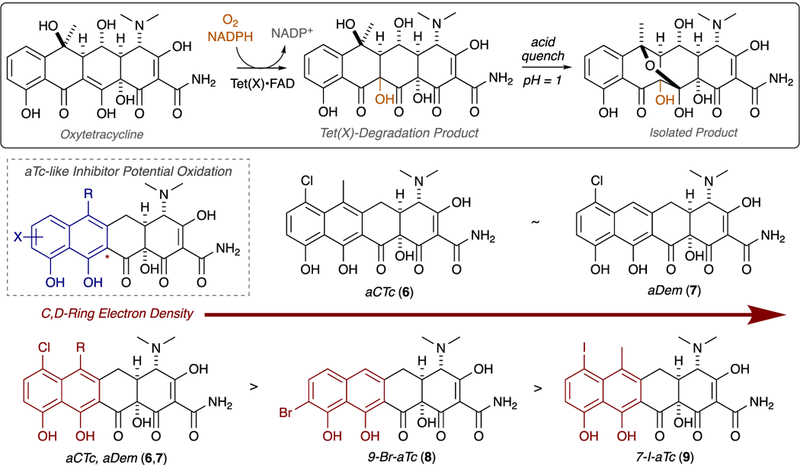

Using Tet(X) as a model system, we assessed the potential for the aTc analogues to serve as sacrificial substrates via an in vitro, broad-scan optical absorbance kinetic assay coupled to LCMS, as previously reported for the Tet(X)-mediated degradation of aTc.34 The results of the Tet(X)-mediated aTc analog degradation assays are summarized below (Figure 7). We confirmed that aTc is a substrate for Tet(X), indicated by the time- and enzyme-dependent decrease in the 440 nm absorption band and aTc extracted mass (LCMS), and used this result as a positive control for the enzymatic degradation of the aTc scaffold. In general, aTc analog stability increased with D-ring halogenation, and chlorination provided the most “protection” against enzymatic degradation. Moreover, observed stability tracks with degree of electron deficiency and the electron-withdrawing nature of the added substituent (i.e. aCTc is more stable than 9-Br-aTc, which is more stable than 7-I-aTc and aTc, respectively). We hypothesize that this stability is due to decreased nucleophilicity of the C,D-ring aromatic framework, which would be fundamentally important to an enzyme-mediated electrophilic hydroxylation event similar to that determined by Wright and coworkers in 2004 for Tet(X) degradation of oxytetracycline (Figure 8).33

Figure 7.

Tet(X)-mediated degradation of aTc and aTc analogues. A–F. Each panel depicts the degradation of the denoted aTc as observed via optical absorbance spectroscopy and plots of monitored extracted mass counts from LCMS. Each represents a reaction containing purified Tet(X) enzyme (or none, in the case of the control), aTc analog, and an NADPH regenerating system [including MgCl2]. The plots represent extracted ion counts normalized to an internal standard (Fmoc-alanine) and depicted as a percent of the total ion count [aTc+aTc–OH].

Figure 8.

Tet(X)-mediated degradation of oxytetracycline as a model for the degradation of aTc-like sacrificial substrates.

Anhydrodemeclocycline, a Special Case

As detailed above, chlorinated aTc analog anhydrodemeclocycline (aDem, 7) possesses potent in vitro inhibitory activity against the Tet(X)- and Tet(X)_3-mediated degradation of tetracycline antibiotics (apparent IC50s 1–4 µM, Figure 9A–C) and rescues tetracycline activity in whole cell E. coli expressing these enzymes (Figure 6A); however, 7 was found to possess poor in vitro inhibitory activity against the enzymatic degradation of both tetracycline and demeclocycline by soil-derived tetracycline destructase Tet(50). Moreover, when aDem was exposed to Tet(50) in the presence of NADPH and absence of tetracycline in an optical absorbance kinetic assay, a steady, observable decrease in the absorbance at 400 nm was observed, suggesting that aDem itself was a substrate for Tet(50). To expand upon this observation, we determined kinetic parameters for the aDem dose-dependent response, similar to the Michaelis-Menten parameters previously described (Figure 9D); however, LCMS-coupled experiments for the reaction showed no measurable decrease in aDem extracted mass over time (Supporting Information Figure 3)—suggesting that the decrease in absorbance at 400 nm was the result of rapid, aDem-dependent Tet(50)-mediated consumption of NADPH (broad absorbance band at 340 nm) and not the enzymatic degradation of aDem 7.

Figure 9.

aDem inhibition of tetracycline destructase-mediated degradation of first generation tetracyclines. A. aDem inhibition of tetracycline destructase degradation of tetracycline. B. aDem inhibition of tetracycline destructase degradation of demeclocycline. C. Apparent IC50 for the in vitro inhibition of tetracycline and demeclocycline degradation by tetracycline destructase enzymes with aTc and aDem. D. Michaelis-Menten plot of dose-dependent aDem acceleration of Tet(50) consumption of NADPH, apparent Km, and calculated catalytic efficiency. Error bars represent standard deviation for two to three independent trials. All data points possess error bars, though some are not visible at the plotted scale.

The previously reported X-ray crystal structure of aTc bound to Tet(50) revealed a unique inhibitor binding mode, denoted Mode IA,D,42 resulting from the non-covalent interaction of aTc with residues in both the substrate binding domain and the FAD binding domains of the enzyme (Figure 10A).37 In particular, the C6-methyl substituent on aTc occupies a small hydrophobic pocket between lysine 198, lysine 205, methionine 222 of the substrate binding domain. Because this substituent is notably absent in aDem, we hypothesized that binding mode flexibility previously observed for tetracycline-inactivating enzymes could allow for the accommodation of aDem in a unique, non-reactive binding mode to promote the NADPH-dependent reduction of the mobile flavin element without providing a productive pathway for the degradation of enzyme-bound aDem. Moreover, because the addition of aDem promotes the Tet(50)-mediated consumption of NADPH without resulting in the degradation of aDem itself, we hypothesized that the formation of a reactive hydroperoxyflavin cofactor in the absence of a viable substrate would lead to the release of hydrogen peroxide generated from the non-specific oxidation of water. The NADPH-dependent formation of hydrogen peroxide from FMOs has been reported previously.50,51 Thus, we characterized the aDem-promoted, Tet(50)-mediated consumption of NADPH using a broad-scan optical absorbance kinetic assay (Figure 10B) and confirmed the formation of hydrogen peroxide using a colorimetric detection method (Pierce™ Quantitative Peroxide Assay, ThermoScientific, Figure 10C). The non-specific formation of hydrogen peroxide was not unique to aDem, as it was also observed in the Tet(50)-mediated degradation of tetracycline (See Supporting Information Figures 4, 5), confirming that “ligand” binding to the substrate-binding domain promotes the consumption of NADPH and reduction of the mobile flavin cofactor (as is canonical with Class A FMO enzymes).38 This mode of inhibition is under further investigation in our lab and might prove to be effective against pathogens expressing tetracycline destructases, as a method of inducing oxidative stress by stimulating flavin reduction and release of hydrogen peroxide inside the cell.

Figure 10.

A. X-ray crystal structure of aTc bound to Tet(50) [PDB ID: 5TUF] and corresponding binding mode identifier; B. Time- and aDem-dependent degradation of NADPH by Tet(50) observed using a broad-scan optical absorbance kinetic assay; C. Hydrogen peroxide colorimetric detection experiments, from left to right: NADPH (no enzyme) control, no enzyme control (NADPH+aDem), Tet(50)+NADPH [no aDem] reaction mixture, and Tet(50)+NADPH+aDem reaction mixture.

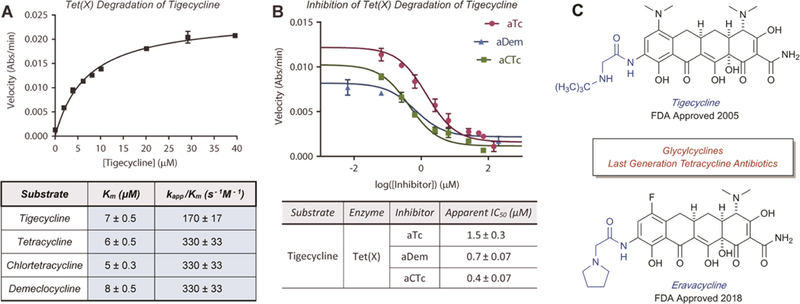

Inhibiting Tet(X) Degradation of Third Generation Tetracycline, Tigecycline

The rise of multi-drug resistant, superinfections has cultivated a renaissance for tetracycline antibiotics as last resort treatments.19 In 2005, the first member of the third-generation tetracyclines tigecycline was FDA approved for the treatment of skin and intra-abdominal infections and pneumonia.52 Earlier this year, two additional third-generation tetracyclines, eravacycline and omadacycline, were FDA approved for similar treatment strategies (Figure 11C).53,54 In this report, we used first-generation tetracyclines as model systems for tetracycline-inactivating enzyme activity; however, with the advent of tigecycline, eravacycline, and omadacycline, the enzymatic degradation of last-generation tetracyclines is fundamentally important to study since new resistance mechanisms, including antibiotic inactivation, are certain to emerge upon widespread antibiotic deployment. The third-generation tetracyclines were strategically designed to overcome resistance due to efflux and ribosome protection, making antibiotic inactivation a likely candidate for future clinical resistance. Previous reports have identified that Tet(X) can degrade tigecycline and eravacycline, albeit slowly, to achieve resistance to these last-generation tetracyclines.55,56,57 Resistance to tigecycline was not observed with the soil-derived tetracycline destructase enzymes, including Tet(50), presumably because the presence of the “Gatekeeper helix” excludes productive accommodation of tetracyclines with bulky D-ring substituents (Figure 2C).34,37 Building upon previous reports, we confirmed and characterized the Tet(X)-mediated degradation of tigecycline and determined Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters using an optical absorbance kinetic assay (Figure 11A). After identifying the most promising inhibitor candidates from previously described in vitro and whole cell inhibition assays, we evaluated the in vitro inhibitory activity of aTc, aCTc, and aDem against the Tet(X)-mediated degradation of tigecycline and found all to be potently inhibitory (apparent IC50s ~0.4 to 1.5 μM). Unfortunately, in our hands, whole cell E. coli expressing Tet(X) displays minimal resistance to tigecycline (2-fold increase over empty vector controls); thus, it was difficult to identify inhibition profiles from variations in the limited resistance response. However, the potent in vitro inhibition of aTc, aCTc, and aDem against Tet(X) degradation of tigecycline are promising preliminary results for further development of adjuvant approaches to combat the enzymatic degradation of last generation tetracyclines. Moreover, because of the functional similarities and phylogenetic clustering of the gut-derived enzymes, we hypothesize that Tet(X)_3 may possess similar abilities to degrade last-generation tetracyclines with velocities more amenable to both in vitro and whole cell inhibition assays—though full characterization of Tet(X)_3 was somewhat beyond the scope of this report. Studies focused on the resistance profile and microbial evolution of tetracycline-inactivating enzyme Tet(X)_3 are currently ongoing in our laboratories and will be reported in due course.

Figure 11.

Michaelis-Menten kinetics of tetracycline destructase-mediated degradation of last generation tetracyclines. A. Michaelis-Menten plot and apparent kinetic parameters (Km, kapp, and catalytic efficiencies) for the Tet(X)-mediated degradation of tigecycline. C. Last generation tetracycline antibiotics tigecycline and eravacycline. Error bars represent standard deviation for three independent trials. All data points possess error bars, though some are not visible at the plotted scale.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the synthesis and biological evaluation of aTc-like small molecule inhibitors of tetracycline-inactivating enzymes is reported (Figure 12A). The four analogues were screened for inhibitory activity against the enzymatic degradation of tetracycline antibiotics by three representative tetracycline destructase enzymes via both in vitro and whole cell-based inhibition assays. All synthesized analogues were found to possess in vitro inhibitory activity to some degree, and inhibitor potency was found to vary largely as a function of enzyme and moderately as a function of inhibitor-substrate pairing within the context of a single enzyme. The addition of electron-withdrawing groups to the D-ring of aTc was found to improve both the enzymatic and non-enzymatic stability of the aTc analogues, and potent in vitro inhibitory activity of this small library shows promise for the rational design of larger tetracycline-inactivating enzyme inhibitor libraries. Notably, aTc and chlorinated analogues aCTc and aDem were found to inhibit the Tet(X)-mediated degradation of last-generation tetracycline, tigecycline. Further development of small molecule inhibitors of glycylcycline-inactivating enzymes like Tet(X), with open active sites that can accommodate large D-ring substituents on tetracycline substrates (Figure 12B),35 are fundamentally important to establishing viable adjuvant approaches that combat the imminent emergence of this resistance mechanism in multi-drug resistant infections. Efforts aimed at improving inhibitor stability while maintaining potency are currently ongoing in our laboratories and will be reported in due course.

Figure 12.

Toward extended library synthesis of aTc-like inhibitors of tetracycline destructase enzymes. A. An adjuvant approach to combat enzymatic inactivation of tetracycline antibiotics and summary of preliminary structure-activity information. B. Surface view of X-ray crystal structure of Tet(X) bound to tigecycline (PDB ID 4a6n) highlights importance of open active site to accommodate bulky D-ring substituents, suggesting further use of glycylcycline antibiotics may drive selective pressure of tetracycline destructase-involved resistance mechanisms.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General methods.

Unless stated, all synthetic reactions were performed under inert, argon atmosphere, and all in vitro kinetic assays were prepared actively open to air (in non-degassed solvents). All solvents—including deuterated NMR solvents—and reagent chemicals used in preparation or analysis of the aTc analogue library were obtained commercially and used without further purification. IR spectroscopy was performed on a Bruker Alpha FTIR machine with a Pt-ATR diamond, and IR data was analyzed using Bruker OPUS 7.5. Melting points were observed using a Stuart SMP10 digital melting point apparatus. NMR spectra were obtained on a Varian Unity-Plus 300 MHz, Varian Unity-Inova 500 MHz, or Agilent PremiumCompact+ 600 MHz spectrometer. All FIDs were processed using Mestrenova version 11.0.4 software. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in ppm and referenced to residual non-deuterated solvent. Coupling constants (J) are reported in hertz (Hz). High-resolution mass spectrometry data was obtained at the Danforth Plant Science Center (DPSC) in St. Louis, MO, by direct infusion using an Advion Nanomate Triversa robot into a Thermo-Fisher Scientific Q-Exactive mass spectrometer, and mass spectra were recorded in positive ion mode from m/z 150–500 and a resolution setting of 140,000 (at m/z 200). In vitro degradation experiments monitored by optical absorbance spectroscopy were performed on an Agilent Cary 50 UV-visible spectrophotometer. In vitro degradation experiments monitored by LCMS were performed using an Agilent 6130 single quadrupole instrument with G1313 autosampler, G1315 diode array detector, and 1200 series solvent module and separated using a Phenomenex Gemini C18 column, 50 × 2 mm (5 μm) with guard column cassette and a linear gradient of 0% acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid to 95% acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid over 20 min at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min before analysis by electrospray ionization (ESI+). Whole cell assays were performed using Difco BBL Mueller-Hinton broth in Costar 96 well plates at 37˚ C. Endpoint growth was assayed at OD600 using a Synergy H1 plate reader (BioTek, Inc.).

Cloning, expression, and purification of tetracycline-destructase enzymes.

All genes corresponding to the tetracycline destructases34, 37 used in this report (For Tet(X)_3, see Supporting Information Table 1) were cloned into pET28b(+) vectors (Novagen) as previously described (BamHI and NdeI restriction sites)34,37 and transformed into BL21-Star (DE3) competent cells (Life Technologies). Cells were cultured at 37 °C in lysogeny broth (LB) containing kanamycin (0.03 mg/mL); once the uninduced culture reached an OD600 of 0.6, the cells were cooled to 0 °C, induced with 1 mM IPTG, and allowed to grow at 15 °C for 12–15 hours (harvest OD600 varied by tetracycline destructase expressed, but on average, harvest OD600<4.5 resulted in greater isolated enzyme yield). To harvest, the induced cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 15 minutes (4 °C) and resuspended in cold 40 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM K2HPO4, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 8.0) containing SIGMAFAST protease inhibitor. The cells were transferred to falcon tubes, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. To harvest, the cells were thawed and mechanically lysed using an Avestin EmulsiFlex-C5 cell disruptor, and the resultant lysate was centrifuged at 45,000 rpm for 35 minutes. The supernatant was transferred to a column containing pre-washed Ni-NTA resin and incubated for 30–45 minutes; at which point, the resin was washed with lysis buffer (2 × 40 mL), and the protein was eluted from the resin with fractions of elution buffer (5 × 10 mL, 50 mM K2HPO4, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 300 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, pH 8.0). The fractions were combined in 10,000 MWCO Snakeskin dialysis tubing (ThermoScientific) and soaked in buffer (50 mM K2HPO4 pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT) overnight to minimize imidazole concentration. To isolate the desired protein, the dialyzed solution was concentrated using a 30K MWCO Amicon centrifugal filter (Millipore-Sigma), and concentrated protein solution was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen (50 μL portions) and stored at −80 °C.

Kinetic characterization of tetracycline inactivation.

Kinetic characterization of tetracycline inactivation was achieved in a manner similar to previously reported procedures. 37 In brief, reaction samples were prepared in TAPS buffer (100 mM, pH 8.5) with 504 μM NADPH, 5.04 mM MgCl2, varying concentrations of tetracycline substrate (typically, 0–40 μM), and 0.4 μM enzyme. After the addition of enzyme, the reactions (in duplicate or triplicate) were mixed, manually by pipette, and the reaction was monitored continuously in a single frame by optical absorbance spectroscopy (absorbance at 380 nm, Carey UV-Visible spectrophotometer) for 3–4 minutes. Initial enzyme velocities were determined by linear regression using Agilent Cary WinUV Software over the linear range of the reaction, and the velocities were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation58,59,60 using GraphPad Prism6.

Synthesis and characterization of aTc analogues 5–8.

(4S,4aS,12aS)-7-chloro-4-(dimethylamino)-3,10,11,12a-tetrahydroxy-6-methyl-1,12-dioxo-1,4,4a,5,12,12a-hexahydrotetracene-2-carboxamide hydrochloride (aCTc, 6):

To a clean, dry round bottom flask, equipped with stirbar and reflux condenser, was added chlortetracycline hydrochloride (50 mg, 0.10 mmol) and 6 N HCl in methanol (5 mL) under argon atmosphere. The reaction was heated to 60 °C and allowed to stir at 60 °C for 1.5 hours (monitored by LCMS). When the reaction was complete, the reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure to provide crude product (50 mg, 0.10 mmol, 100% crude yield) as an orange solid [clean by NMR]. Purification by preparative HPLC (Si-C18 reverse phase column, gradient 0–95% CH3CN/H2O with 0.1% formic acid, tR = 16 min) provided (4S,4aS,12aS)-7-chloro-4-(dimethylamino)-3,10,11,12a-tetrahydroxy-6-methyl-1,12-dioxo-1,4,4a,5,12,12a-hexahydro-tetracene-2-carboxamide, which was reconstituted as the hydrochloride salt to provide the title compound as an orange solid (44 mg, 0.089 mmol, 91% yield). FTIR (neat) 3306, 3042, 1621, 1583, 1565, 1531, 1464, 1375, 1217, 1137, 1058, 820, 560 cm−1; M.p. 211–212 °C (decomposed); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.68 (s, 1H), 9.22 (s, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.46 (ddt, J = 18.0, 14.2, 4.9 Hz, 2H), 3.15 (dd, J = 16.8, 8.9 Hz, 1H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 2.63 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 199.7, 192.7, 187.4, 172.1, 163.2, 157.6, 136.2, 135.9, 134.1, 121.5, 119.3, 114.6, 111.8, 109.2, 97.6, 76.2, 66.9, 42.9 (2C), 35.8, 29.6, 19.2; HRMS (TOF MS ES+) calcd for C22H22ClN2O7 [M+H]+ 461.1116; found 461.1115.

(4S,4aS,12aS)-7-chloro-4-(dimethylamino)-3,10,11,12a-tetrahydroxy-1,12-dioxo-1,4,4a,5,12,12a-hexahydrotetracene-2-carboxamide hydrochloride (aDem, 7):

To a clean, dry round bottom flask, equipped with stirbar and reflux condenser, was added demeclocycline hydrochloride (50 mg, 0.10 mmol) and 6 N HCl in methanol (5 mL) under argon atmosphere. The reaction was heated to 70 °C and allowed to stir at 60 °C for 3 hours (monitored by LCMS). When the reaction was complete, the reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure to provide crude product (54 mg, 0.11 mmol, quant. yield) as a yellow-orange solid (clean by NMR). Purification by preparative HPLC (Si-C18 reverse phase column, gradient 0–95% CH3CN/H2O with 0.1% formic acid, tR = 15 min) to provide (4S,4aS,12aS)-7-chloro-4-(dimethylamino)-3,10,11,12a-tetrahydroxy-1,12-dioxo-1,4,4a,5,12,12a-hexahydrotetracene-2-carboxamide, which was reconstituted as the hydrochloride salt to provide the title compound as a light orange solid (37 mg, 0.077 mmol, 77% yield). FTIR (neat) 3301, 3076, 1619, 1567, 1533, 1444, 1375, 1353, 1202, 1188, 1071, 993, 820, 685 cm−1; M.p. 213–214 °C (decomposed); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.69 (s, 1H), 9.29 (s, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (s, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.58 (dd, J = 17.3, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.53 – 3.39 (m, 2H), 2.89 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 198.3, 193.1, 187.2, 172.2, 165.2, 157.2, 135.9, 135.2, 132.7, 119.2, 113.9, 113.5, 111.3, 109.7, 97.5, 76.8, 66.4, 42.3, 41.6, 37.2, 29.5; HRMS (TOF MS ES+) calcd for C21H20ClN2O7 [M+H]+ 447.0959; found 447.0958.

(4S,4aS,12aS)-4-(dimethylamino)-3,10,11,12a-tetrahydroxy-7-iodo-6-methyl-1,12-dioxo-1,4,4a,5,12,12a-hexahydrotetracene-2-carboxamide hydrochloride (7-I-aTc, 8):

Procedure A –

To a clean, dry round bottom flask, equipped with stirbar, was added anhydrotetracycline hydrochloride (100 mg, 0.216 mmol) and methanol (2.2 mL) under argon atmosphere. The flask was cooled to –10 °C, and N-iodosuccinimide (58.3 mg, 0.259 mmol) was added in one portion. The reaction was allowed to warm to room 0 °C over 2 hours, then stirred at 0 °C for 1 hour (monitored by LCMS). When the reaction was complete, the reaction was diluted with methanol (to 10 mL total volume) and immediately purified by preparative HPLC (Si-C18 reverse phase column, gradient 0–95% CH3CN/H2O with 0.1% formic acid, tR = 16 min) to provide (4S,4aS,12aS)-4-(dimethylamino)-3,10,11,12a-tetrahydroxy-7-iodo-6-methyl-1,12-dioxo-1,4,4a,5,12,12a-hexahydrotetracene-2-carboxamide, which was reconstituted as the hydrochloride salt to provide the title compound as an orange solid (70.0 mg, 0.119 mmol, 55% yield).

Procedure B –

To a clean, dry round bottom flask, equipped with stirbar, was added anhydrotetracycline hydrochloride (250 mg, 0.540 mmol) and methanol (25 mL) under argon atmosphere. The flask was cooled to 0 °C and solid N-iodosuccinimide (0.134 g) was added, in one portion. The reaction stirred at 0 °C for 1 hour (monitored by LCMS), and the reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure (no heating) to yield a crude brown solid. The solid was triturated with tert-butylmethylether (TBME) for 30 minutes protected from light; filtration provided the title product (0.3178 g, 0.540 mmol, quantitative crude yield) as a green-brown solid. FTIR (neat) 3307, 3078, 1660, 1615, 1556, 1396, 1377, 1321, 1228, 1131, 1075, 1058, 810, 702, 618 cm−1; M.p. 188–189 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.62 (s, 1H), 9.23 (s, 1H), 8.01 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 4.38 (s, 1H), 3.57 – 3.36 (m, 3H), 3.16 (s, 1H), 2.89 (s, 6H), 2.56 (s, 1H), 2.40 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 199.5, 192.9, 187.2, 179.3, 163.7, 156.2, 141.4, 138.5, 130.5, 121.6, 117.2, 112.2, 108.7, 97.4, 79.6, 76.3, 67.0, 42.1 (2C), 35.8, 29.5, 14.1; HRMS (TOF MS ES+) calcd for C22H22IN2O7 [M+H]+ 553.0472; found 553.0469.

(4S,4aS,12aS)-9-bromo-4-(dimethylamino)-3,10,11,12a-tetrahydroxy-6-methyl-1,12-dioxo-1,4,4a,5,12,12a-hexahydrotetracene-2-carboxamide hydrochloride (9-Br-aTc, 9):

To a clean, dry round bottom flask, equipped with a stirbar and argon inlet, was added liquid bromine (13 μL, 0.2592 mmol, 1.2 equiv.), acetic acid (10 mL), and trifluoroacetic acid (2 μL, 0.0216 mmol, 0.1 equiv.). The mixture was heated to 50 °C (over 20 minutes), at which point anhydrotetracycline hydrochloride (100 mg, 0.216 mmol) was added in one portion. The reaction mixture stirred at 50 °C for 30 minutes; then, the reaction was cooled to room temperature and stirred at room temperature for 4 hours (monitored by LCMS). After the reaction was complete, the crude mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure to provide the crude product, which was reconstituted with aqueous HCl to provide the title compound (0.1165 g, 0.215 mmol, quantitative crude yield) as an orange solid HCl salt. FTIR (neat) 3295, 3078, 1618, 1553, 1393, 1373, 1317, 1224, 1124, 1058, 699, 620 cm−1; M.p. 203–204°C (decomposed); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.64 (s, 1H), 9.22 (s, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.56 (dd, J = 17.7, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 3.46 (dd, J = 9.9, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 3.07 (d, J = 14.5 Hz, 1H), 2.91 (s, 6H), 2.39 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 200.6, 192.7, 187.0, 172.1, 161.8, 153.4, 137.7, 135.8, 131.6, 122.3, 116.7, 112.6, 109.3, 104.5, 97.3, 76.4, 67.0, 42.1 (2C), 35.3, 21.1, 14.0; HRMS (TOF MS ES+) calcd for C22H22BrN2O7 [M+H]+ 505.0610; found 505.0610.

In vitro characterization of aTc and aTc analog inhibition.

Half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) for the aTc and aTc analog inhibition of Tet(50), Tet(X), and Tet(X)_3 were determined from the non-linear regression analysis of initial velocities of tetracycline degradation in the presence of varying concentrations of chosen inhibitor. Reaction samples were prepared in 100 mM TAPS buffer (pH 8.5) with 504 μM NADPH, 5.04 mM MgCl2, 25.3 μM tetracycline substrate, varying concentrations of inhibitor (μΜ), and 0.4 μM enzyme. After the addition of enzyme, the reactions (in triplicate) were mixed manually by pipette, and the reaction was monitored, continuously in a single frame, by optical absorbance spectroscopy (absorbance at 380 or 400 nm, Carey UV-Visible spectrophotometer) for 4 minutes. Initial enzyme velocities were determined by linear regression using Agilent Cary WinUV Software over the linear range of the reaction. The velocities were plotted against the logarithm of inhibitor concentration, and IC50s were determined using non-linear regression analysis in Graphpad Prism 6. Plus/minus error values were determined using linear regression analysis of initial velocities versus concentrations of inhibitor in Graphpad Prism 6. Each set of experiments was accompanied by a variety of controls, including a no enzyme control (NADPH+Tet+Inhibitor)—which was used to simulate full enzyme inhibition and assigned to inhibitor concentration of 1 × 1015, and a no inhibitor control (NADPH+Tet+Enzyme)—which was assigned an inhibitor concentration of 1 × 10−15. A no substrate control (NADPH+Inhibitor+Tet) was also performed to identify competitive background signals from the enzymatic degradation of the inhibitor itself. For all inhibitor-enzyme combinations (except for Tet(50)-aDem), the initial velocities of the no substrate controls were negligible.

Checkerboard whole cell inhibition assay.

Substrates and inhibitors were dissolved DMSO before being diluted to working concentrations in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin. A two-fold dilution series of each drug was made independently across 8 rows of a 96 well master plate before 100 μL of each drug dilution series were combined into a 96 well culture plate (Costar), with rows included for no-drug and no-inocula controls. The plates were inoculated with ~1 μL of tetracycline destructase expressing E. coli MegaX (Invitrogen) diluted to OD600 0.1 using a sterile 96-pin replicator (Scinomix). Plates were sealed with Breathe-Easy membranes (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated at 37 ˚C with shaking at 220 rpm. Endpoint growth was assayed at OD600 at 20 and 36 hours of growth using a Synergy H1 plate reader (BioTek, Inc.). Three independent replicates were performed for each strain/drug combination. Highlighted MIC data was refined from a complete raw data set to identify mixtures resulting in the largest MIC fold change (at least 4-fold) with the least amount of inhibitor (fold change/inhibitor dose) (See Figure 6A and Supporting Information Tables 2a–2c). Synergy of inhibitor and tetracycline combinations was determined using the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) method,45

| (Eq. 1) |

where FICI>1 indicates antagonism, FICI = 1 indicates additivity, and FICI <1 indicates synergy.

Kinetic characterization of aTc and aTc analog degradation by Tet(X).

The kinetic characterization of the degradation of aTc and aTc analogues by Tet(X) was monitored by optical absorbance spectroscopy (Carey UV-Visible spectrophotometer) coupled to LCMS detection (Agilent 6130 single quadrupole instrument with G1313 autosampler, G1315 diode array detector, and 1200 series solvent module and separated using a Phenomenex Gemini C18 column, 50 × 2 mm (5 μm) with guard column cassette and a linear gradient of 0% acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid to 95% acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid over 20 min at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min before analysis by electrospray ionization (ESI+)). Reactions (in duplicate) were prepared in 100 mM TAPS buffer (pH 8.5) with an NADPH regenerating system (40 mM glucose-6-phosphate, 4 mM NADP+, 1 mM MgCl2, 4 U/mL glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase), 28.0 μM substrate (aTc or corresponding analog), and 0.24 μM enzyme. Reaction progress was monitored by Optical absorbance spectroscopy (280–550 nm, 1 nm and 30 min intervals) over 3.5 hours, where 150 μL of reaction sample were removed at 30-minute intervals and quenched with 600 μL volumes of quench solution (1:1 acetonitrile:0.25M aqueous HCl). The quenched samples were centrifuged (5000 rpm, room temperature) for 5 minutes, and 600 μL of supernatant was transferred to an LCMS-compatible vial containing Fmoc-alanine internal standard (2.21 μM final concentration) and analyzed by LC-MS (reverse-phase HPLC, C18-silica, gradient 0–95% CH3CN/H2O, 0.5 mL/min flow rate). Substrate masses [M+H]+ and hydroxylated product masses [M–OH+H]+ were extracted from the crude mass chromatogram and normalized to the internal standard [M+H]+ counts. No enzyme controls were performed for each aTc analog screened and showed no significant non-enzymatic degradation over the course of the observable reaction. Degradation of 7-I-aTc and 9-Br-aTc at extended solution times (overnight) showed a decrease in LCMS extracted ion counts for both analogues, suggesting some non-enzymatic degradation over longer reaction times.

Qualitative detection of aDem-promoted hydrogen peroxide formation by Tet(50).

Qualitative colorimetric detection of aDem-promoted hydrogen peroxide formation by Tet(50) was performed using an aqueous Pierce™ Quantitative Peroxide Assay kit (ThermoScientific). Reaction samples were prepared in 100 mM TAPS buffer (pH 8.5) with 252 μM NADPH, 2.52 mM MgCl2, 25 μM substrate (either aDem or Tet), and 0.4 μM enzyme. After the addition of enzyme, the reaction was mixed manually by pipette, and the reaction was monitored by Optical absorbance spectroscopy (280–550 nm, 1nm and 0.1 min scan intervals) over 8 minutes. At 8 minutes, 100 μL of reaction solution was added to a detection Eppendorf containing 1000 μL of Working Reagent (prepared according to specifications for Pierce Quantitative Peroxide Assay kit). The detection Eppendorf was incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature to result in the observed color changes reported in the main text (see Figure 10C and Supporting Information Figure 5).

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Semisynthetic strategies toward aTc analogs 6–9.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Washington University in St. Louis, Washington University School of Medicine, and the National Institutes of Health for their support of this research and our programs. In particular, N Tolia would like to thank the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health for the support of his program. We would also like to acknowledge J Kao and M Singh (WUSTL, Department of Chemistry) for their assistance with NMR experiments and B Evans (Danforth Plant Science Center, St. Louis, MO) and his team for their assistance in acquiring high-resolution mass spectra for all synthesized compounds. In addition, JL Markley would like to acknowledge the WM Keck Postdoctoral Program in Molecular Medicine for funding support of her postdoctoral fellowship.

Funding Sources

This research is supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID-NIH R01–123394). N Tolia is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. JL Markley is supported by the WM Keck Program in Molecular Medicine.

8. ABBREVIATIONS

- Tet

tetracycline

- CTc

chlortetracycline

- Dem

demeclocycline

- Oxy

oxytetracycline

- aTc

anhydrotetracycline

- aCTc

anhydrochlortetracycline

- aDem

anhydrodemeclocycline

- 7-I-aTc

7-iodoanhydrotetracycline

- 9-Br-aTc

9-bromoanhydrotetracycline

- FMO

flavin-dependent monooxygenases

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced form

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- LCMS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- IR

infrared spectroscopy

- Mp

melting point

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. A Supporting Information file, including relevant strains, sequences, plasmids and primers, SDS-Page gel images of purified enzyme, Lineweaver-Burk plots and methods for the aTc inhibition of the tetracycline destructase-mediated degradation of tetracycline, expanded data tables for whole cell inhibition assays of E. coli expressing tetracycline destructase enzymes, in vitro characterization of the aDem- and Tet-promoted consumption of NADPH by Tet(50), images for the qualitative colorimetric detection of Tet- and aDem-promoted hydrogen peroxide formation by Tet(50), and NMR spectra of synthesized compounds 6–9, is available free of charge (PDF).

Notes

The authors have submitted a patent application for the use of anhydrotetracycline and aTc-like small molecules as inhibitors of tetracycline destructase enzymes (US Patent Application 20170369864).

REFERENCES

- (1).Paine TF Jr.; Collins HS; Finland M Bacteriologic Studies on Aureomycin. J. Bacteriol 1948, 56, 489–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).The history of tetracycline antibiotics in the treatment of human and livestock has been extensively reviewed. For some recent reviews, see: Nelson ML; Levy SB The History of the Tetracyclines. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 2011, 1241, 17–32. DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Bahrami F; Morris DL; Pourgholami MH Tetracyclines: Drugs with Huge Therapeutic Potential. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem 2012, 12, 44–52. DOI: 10.2174/138955712798868977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Griffin MO; Fricovsky E; Cabellas G; Villarreal F Tetracyclines: a Pleitropic Family of Compounds with Promising Therapeutic Properties. Review of the Literature. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol 2010, 299, C539–C548. DOI: 10.1152/ajpcell.00047.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Grossman TH Tetracycline Antibiotics and Resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 2016, 6, a025387 DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a025387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Nguyen F; Starosta AL; Arenz S; Sohmen D; Donhofer A; Wilson DN Tetracycline Antibiotics and Resistance Mechanisms. Biol. Chem 2014, 295, 559–575. DOI: 10.1515/hsz-2013-0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Daghrir R; Drogui P Tetracycline Antibiotics in the Environment: a Review. Env. Chem. Lett 2013, 11, 209–227. DOI: 10.1007/s10311-013-0404-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Zakeri B; Wright GD Chemical Biology of Tetracycline Antibiotics. Biochem. Cell Biol 2008, 86, 124–136. DOI: 10.1139/O08-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Thaker M; Spanogiannopoulos P; Wright GD The Tetracycline Resistome. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 2010, 67, 419–431. DOI: 10.1007/s00018-009-0172-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Liu F; Myers AG Development of a Platform for the Discovery and Practical Synthesis of New Tetracycline Antibiotics. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2016, 32, 48–57. DOI: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Burke MD Flexible Tetracycline Synthesis Yields Promising Antibiotics. Nat. Chem. Biol 2009, 5, 77–79. DOI: 10.1038/nchembio0209-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Chopra I; Roberts M Tetracycline Antibiotics: Mode of Action, Applications, Molecular Biology, and Epidemiology of Bacterial Resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 2001, 65, 232–260. DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kasbekar N Tigecycline: A New Glycylcycline Antimicrobial Agent. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm 2006, 63, 1235–1243. DOI: 10.2146/ajhp050487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Rose WE; Rybak MJ Tigecycline: First of a New Class of Antimicrobial Agents. Pharmacotherapy 2006, 26, 1099–1110. DOI: 10.1592/phco.26.8.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Sutcliffe JA; O’Brien W; Fyfe C; Grossman TH Antibacterial Activity of Eravacycline (TP-434), a Novel Fluorocycline, Against Hospital and Community Pathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 5548–5558. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01288-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ronn M; Zhu Z; Hogan PC; Zhang W-Y; Niu J; Katz CE; Dunwoody N; Gilicky O; Dent Y; Hunt DK; He M; Chen C-L; Sun C; Clark RB; Xiao X-Y Process R&D of Eravacycline: the First Fully Synthetic Fluorocycline in Clinical Development. Org. Process Res. Dev 2013, 17, 838–845. DOI: 10.1021/op4000219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Macone AB; Caruso BK; Leahy RG; Donatelli J; Weir S; Draper MP; Tanaka SK; Levy SB In Vitro and In Vivo Antibacterial Activities of Omadacycline, a Novel Aminomethylcycline. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 1127–1135. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01242-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Zhanel GG; Homenuik K; Nichol K; Noreddin A; Vercaigne L; Embil J; Gin A; Karlowsky JA; Hoban DJ The Glycylcyclines: a Comparative Review with the Tetracyclines. Drugs 2004, 64, 63–88. DOI: 10.2165/00003495-200464010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ruhe JJ; Monson T; Bradsher RW; Menon A Use of Long-Acting Tetracyclines for Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections: Case Series and Review of the Literature. Clin. Infect. Dis 2005, 40, 1429–34. DOI: 10.1086/429628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Huttner B; Jones M; Rubin MA; Neuhauser MM; Gundlapalli A; Samore M Drugs of Last Resort? The Use of Polymyxins and Tigecycline at US Veterans Affairs Medical Centers, 2005–2010. PLoS One 2012, 7, e36649 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Theuretzbacher U; Van Bambeke F; Canton R; Giske CG; Mouton JW; Nation RL; Paul M; Turnidge JD; Kahlmeter G Reviving Old Antibiotics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2015, 70, 2177–2181. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkv157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Connell SR; Tracz DM; Nierhaus KH; Taylor DE Ribosomal Protection Proteins and Their Mechanism of Tetracycline Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2003, 47, 3675–3681. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3675-3681.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Piddock LJV Clinically Relevant Chromosomally Encoded Multidrug Resistance Efflux Pumps in Bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2006, 19, 283–402. DOI: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.382-402.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Davies J Inactivation of Antibiotics and the Dissemination of Resistance Genes. Science 1994, 264, 375–382. DOI: 10.1126/science.8153624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Wright GD Bacterial Resistance to Antibiotics: Enzymatic Degradation and Modification. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2005, 57, 1451–1470. DOI: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Bush K; Jacoby GA Updated Functional Classification of beta-Lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2010, 54, 969–976. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01009-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Brandt C; Braun SD; Stein C; Slickers P; Ehricht R; Pletz MW; Makarewicz O In Silico Serine beta-Lactamases Analysis Reveals a Huge Potential Resistome in Environmental and Pathogenic Species. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 43232 DOI: 10.1038/srep43232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kong K-F; Schneper L; Mathee K Beta-Lactam Antibiotics: From Antibiosis to Resistance and Bacteriology. APMIS 2010, 118, 1–36. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2009.02563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Perez-Llarena FJ; Bou G Beta-Lactamase Inhibitors: The Story So Far. Curr. Med. Chem 2009, 16, 3740–3765. DOI: 10.2174/092986709789104957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Drawz SM; Bonomo RA Three Decades of beta-Lactamase Inhibitors. Clin. Microb. Rev 2010, 23, 160–201. DOI: 10.1128/CMR.00037-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Drawz SM; Papp-Wallace KM; Bonomo RA New beta-Lactamase Inhibitors: a Therapeutic Renaissance in an MDR World. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 1835–1846. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00826-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Bush K; Bradford PA beta-Lactams and beta-Lactamase Inhibitors: An Overview. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 2016, 6, a025247 DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a025247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Yang W; Moore IF; Koteva KP; Bareich DC; Hughes DW; Wright GD TetX is a Flavin-Dependent Monooxygenase Conferring Resistance to Tetracycline Antibiotics. J. Biol. Chem 2004, 279, 52346–52352. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M409573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Forsberg KJ; Patel S; Wencewicz TA; Dantas G The Tetracycline Destructases: A Novel Family of Tetracycline-Inactivating Enzymes. Chem. Biol 2015, 22, 888–897. DOI: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Volkers G; Palm GJ; Weiss MS; Wright GD; Hinrichs W Structural Basis for a New Tetracycline Resistance Mechanism Relying on the TetX Monooxygenase. FEBS Lett 2011, 585, 1061–1066. DOI: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Volkers G; Damas JM; Palm GJ; Panjikar S; Soares CM; Hinrichs W Putative Dioxygen-Binding Sites and Recognition of Tigecycline and Minocycline in the Tetracycline-Degrading Monooxygenase TetX. Acta Cryst 2013, D69, 1758–1767. DOI: 10.1107/S0907444913013802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Park J; Gasparrini AJ; Reck MR; Symister CT; Elliott JL; Vogel JP; Wencewicz TA; Dantas G; Tolia NH Plasticity, Dynamics, and Inhibition of Emerging Resistance Enzymes. Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13, 730–736. DOI: 10.1038/nchembio.2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).van Berkel WJ; Kamerbeek NM; Fraaije MW Flavoprotein Monooxygenases, a Diverse Class of Oxidative Biocatalysts. J. Biotechnol 2006, 124, 670–689. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Montersino S; van Berkel WJ “The flavin monooxygenases,” in Handbook of Flavoproteins Vol. II: Complex Flavoproteins, Dehydrogenases and Physical Methods, Eds Hille R, Miller S, and Palfey B, Berlin: De Gruyter, 51–72. DOI: 10.1515/9783110298345.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Huijbers MME; Montersino S; Westphal AH; Tischler D; van Berkel WJH Flavin Dependent Monooxygenases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 2014, 544, 2–17. DOI: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Romero E; Gomez Castellanos JR; Gadda G; Fraaije MW; Mattevi A Same Substrate, Many Reactions: Oxygen Activation in Flavoenzymes. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 1742–1769. DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Markley JL; Wencewicz TA Tetracycline-Inactivating Enzymes. Front. Microbiol 2018, 9, 1058 DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Nelson ML; Ismail MY; McIntyre L; Bhatia B; Viski P; Hawkins P; Rennie G; Andorsky D; Messersmith D; Stapleton K; Dumornay J; Sheahan P; Verma AK; Warchol T; Levy SB Versatile and Facile Synthesis of Diverse Semisynthetic Tetracycline Derivatives via Pd-Catalyzed Reactions. J. Org. Chem 2003, 68, 5838–5851. DOI: 10.1021/jo030047d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Berens C; Lochner S; Lober S; Usai I; Schmidt A; Drueppel L; Hillen W; Gmeiner P Subtype Selective Tetracycline Agonists and their Application for a Two-Stage Regulatory System. ChemBioChem 2006, 7, 1320–1324. DOI: 10.1002/cbic.200600226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Berenbaum MC A Method for Testing Synergy with Any Number of Agents. J. Infect. Dis 1978, 137, 122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Luiz M; Gutierrez MI; Bocco G; Garcia NA Solvent Effect on the Reactivity of Monosubstituted Phenols Toward Singlet Molecular Oxygen in Alkaline Media. Can. J. Chem 1993, 71, 1247–1252. DOI: 10.1139/v93-160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Juretic D; Puric J; Kusic H; Marin V; Bozic AL Structural Influence on Photooxidation Degradation of Halogenated Phenols. Water Air Soil Pollut 2014, 225, 2143 DOI: 10.1007/s11270-014-2143-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Gomez-Pacheco CV; Sanchez-Polo M; Rivera-Utrilla J; Lopez-Penalver JJ Tetracycline Degradation in Aqueous Phase by Ultraviolet Radiation. Chem. Eng. J 2012, 187, 89–95. DOI: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.01.096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Miskoski S; Sanchez E; Garavano M; Lopez M; Soltermann AT; Garcia NA Singlet Molecular Oxygen-mediated Photo-oxidation of Tetracyclines: Kinetics, Mechanism and Microbiological Implications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol 1998, 43, 164–171. DOI: 10.1016/S1011-1344(98)00104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Siddens LK; Krueger SK; Henderson MC; Williams DE Mammalian Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase (FMO) as a Source of Hydrogen Peroxide. Biochem. Pharmacol 2014, 89, 141–147. DOI: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Tynes RE; Sabourin PJ; Hodgson E; Philpot RM Formation of Hydrogen Peroxide and N-Hydroxylated Amines Catalyzed by Pulmonary Flavin-Containing Monooxygenases in the Presence of Primary Alkylamines. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 1986, 251, 654–664. DOI: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90375-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Drug Approval Package: Tygacil (tigecycline) for Injection. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: U.S. Food and Drug Administration https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2005/21-821_Tygacil.cfm (Accessed October 24, 2018).

- (53).Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals Announces FDA Approval of XeravaTM (Eravacycline) for Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections (CIAI). Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals https://ir.tphase.com/news-releases/news-release-details/tetraphase-pharmaceuticals-announces-fda-approval-xeravatm (Accessed October 24, 2018).

- (54).News Release: Paratek Announces FDA Approval of NuzyraTM (Omadacycline). http://investor.paratekpharm.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=253770&p=irol-newsArticle&cat=news&id=2369985 (Accessed October 24, 2018).

- (55).Grossman TH; Starosta AL; Fyfe C; O’Brien W; Rothstein D; Mikolajka A; Wilson DN; Sutcliffe JA Target- and Resistance-Based Mechanistic Studies with TP-434, a Novel Fluorocycline Antibiotic. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2012, 56, 2559–2564. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.06187-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Sutcliffe JA; O’Brien W; Fyfe C; Grossman TH Antibacterial Activity of Eravacycline (TP-434), a Novel Fluorocycline, against Hospital and Community Pathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 5548–5558. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01288-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Linkevicius M, Sandegren L, and Andersson DI Potential of Tetracycline Resistance Proteins to Evolve Tigecycline Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 789–796. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.02465-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Michaelis L; Menten ML Die Kinetik der Invertinwirkung. Biochem Z 1913, 49, 333–369. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Johnson KA; Goody RS The Original Michaelis Constant: Translation of the 1913 Michaelis-Menten Paper. Biochem 2011, 50, 8264–8269. DOI: 10.1021/bi201284u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Chen WW; Niepel M; Sorger PK Classic and Contemporary Approaches to Modeling Biochemical Reactions. Genes & Dev 2010, 24, 1861–1875. DOI: 10.1101/gad.1945410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.