Abstract

Background

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is common in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). However, the impact of CAD distribution before TAVR on short‐ and long‐term prognosis remains unclear.

Hypothesis

We hypothesized that the long‐term clinical impact differs according to CAD distribution in patients undergoing TAVR using the FRench Aortic National CoreValve and Edwards (FRANCE‐2) registry.

Methods

FRANCE‐2 is a national French registry including all consecutive TAVR performed between 2010 and 2012 in 34 centers. Three‐year mortality was assessed in relation to CAD status. CAD was defined as at least 1 coronary stenosis >50%.

Results

A total of 4201 patients were enrolled in the registry. For the present analysis, we excluded patients with a history of coronary artery bypass. CAD was reported in 1252 patients (30%). Half of the patients presented with coronary multivessel disease. CAD extent was associated with an increase in cardiovascular risk profile and in logistic EuroSCORE (European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation) (from 19.3% ± 12.8% to 21.9% ± 13.5%, P < 0.001). Mortality at 30 days and 3 years was 9% and 44%, respectively, in the overall population. In multivariate analyses, neither the presence nor the extent of CAD was associated with mortality at 3 years (presence of CAD, hazard ratio [HR]: 0.90; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.78‐1.07). A significant lesion of the left anterior descending (LAD) was associated with higher 3‐year mortality (HR: 1.42; 95% CI: 1.10‐1.87).

Conclusions

CAD is not associated with decreased short‐ and long‐term survival in patients undergoing TAVR. The potential deleterious effect of LAD disease on long‐term survival and the need for revascularization before or at the time of TAVR should be validated in a randomized control trial.

Keywords: Coronary Artery Disease, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is frequently present in patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) because risk factors have been shown to be very similar in both diseases.1, 2, 3 In patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), the prevalence of significant CAD (ie,. >50% stenosis) is reported between 30% to 75%.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 The impact of CAD severity defined with a high SYNTAX (Synergy between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery) score has been recently shown, with impaired clinical outcomes at 1 year after TAVR.22 To our knowledge, few studies have analyzed outcomes according to CAD distribution.23 Therefore, we aimed to assess the long‐term clinical outcomes according to presence, number, and location of CAD before TAVR using the FRench Aortic National CoreValve and Edwards (FRANCE‐2) registry.

2. METHODS

2.1. FRANCE‐2 registry

The FRANCE‐2 registry is a prospective multicenter registry conducted in France and in Monaco between January 2010 and January 2012 in 34 centers, including consecutive symptomatic adults (New York Heart Association [NYHA] functional class ≥II) requiring TAVR for severe aortic stenosis (AS), in whom surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR) was contraindicated or considered high risk according to heart team discussion. Details of the methodology have been previously described.6, 20 Severe AS was defined as aortic valve area < 0.8 cm2, mean aortic valve gradient ≥40 mmHg, or peak aortic jet velocity ≥ 4.0 m/s. The main objective of this registry was to assess TAVR management in routine practice and to measure their association with outcomes over a 5‐year follow‐up. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the French Ministry of Health. All patients provided written informed consent for anonymous processing of their data.

2.2. Procedures

TAVR systems used in the FRANCE‐2 registry were a self‐expandable prosthesis (Medtronic CoreValve ReValving System; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) and a balloon‐expandable prosthesis (Edwards SAPIEN valve; Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA).6, 20 Both were used in most centers, and the choice was left to the discretion of the investigators. No prespecified recommendations were made regarding use of a transfemoral, transapical, or subclavian approach. All patients received aspirin and clopidogrel before the procedure and aspirin alone after 1 to 6 months of dual therapy. The choice between general and local anesthesia for transfemoral implantation was left to the individual team.

2.3. Data collection

An independent clinical events committee adjudicated mortality. All adverse events were adjudicated according to the Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC) classification system.24 Data were recorded on a standardized electronic case report form and sent to a central database (Axonal) over the Internet. Database quality control was performed by checking data against source documents for 10% of patients in randomly selected centers. All fields were examined for missing data or outliers, and teams were asked to complete or correct data wherever possible. Outlying data were checked and excluded if they were erroneous; such exclusion applied to <1% of data.

2.4. Definition of CAD

CAD was defined as a stenosis of >50% of the luminal diameter of the left main stem or the 3 main coronary arteries or their major epicardial branches as assessed during coronary angiography before TAVR. Patients with a history of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) (n = 737) were excluded from the analysis. To define CAD extent, all 3 coronary arteries were assigned 1 point each and 2 points for left main coronary artery (LMCA), whatever the status of left anterior descending (LAD) and left circumflex (LCX), resulting in a maximum score of 3 in patients without a history of CABG. Multivessel CAD was defined as a score of 2 or more. Myocardial revascularization before TAVR was performed according to the decisions of heart teams.

2.5. Study endpoints and follow up

The primary endpoint was death from any cause at 3 years. Secondary safety endpoints were major adverse cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events, cardiac events, cardiac or vascular surgery, bleeding or stroke during follow‐up, and NYHA functional class. Secondary efficacy endpoints were success rate and complications on the VARC criteria.24 Periodic echocardiographic assessments of aortic valve function were performed during the first 3 years, including evaluation of mean gradient and valve area, as well as screening for the presence and severity of aortic or mitral regurgitation. Regurgitation severity was graded on a scale from 0 to 4, with higher grades indicating greater severity. Follow‐up was scheduled in the protocol at 30 days, 6 months, and 1, 2, and 3 years on the basis of consultations with recording of clinical status, events, and echocardiography. Vital status was available for 97.2% of patients at 3 years.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS premium statistics 23.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY). For the main analyses, we compared patients who at the time of TAVR had significant CAD versus patients who had not. In addition, we assessed clinical outcomes according to the extent of CAD (ie, 1‐ to 3‐vessel disease). For quantitative variables, mean and standard deviation were calculated. In addition, median with interquartile range (IQR) was calculated when appropriate. Discrete variables are presented as number of events and percentages. Comparisons were made with χ2 or Fisher exact tests for discrete variables, and by unpaired t tests, Mann–Whitney tests, Kruskall‐Wallis tests, or 1‐way analysis of variance for continuous variables. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier estimators and compared using log‐rank tests. In addition, a propensity score in patients with significant CAD (LAD disease versus no LAD disease) was calculated using multiple logistic regressions and used to build 2 cohorts of patients (428 patients each) matched on the propensity score. Multivariate analyses of predictors of 30‐day mortality were made using backward, stepwise multiple logistic regressions. Correlates of long‐term survival were determined using a multivariate backward stepwise Cox analysis. Variables included in the final multivariate models were selected ad hoc, based upon their physiological relevance and potential to be associated with outcomes. Cumulative hazard functions were computed to assess proportionality. Two models were used: model 1, adjusted on the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE‐1); and model 2, adjusted on clinical characteristics and procedures. For all analyses, a P value <0.05 was considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics and procedures according to CAD extent

CAD was identified in one‐third of the TAVR population after exclusion of CABG patients (Table 1). Multivessel disease defined as a score of 2 or more was observed in half of CAD patients. The severity of CAD was associated with an increase in cardiovascular risk profile including logistic EuroSCORE and left ventricular systolic dysfunction. The mean aortic valve gradient decreased progressively from 50 ± 17 mmHg in patients without CAD to 45 ± 15 mmHg in with 3‐vessel disease.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at baseline according to extent of coronary artery disease

| 0, n = 2192 | 1, n = 650 | 2, n = 397 | 3, n = 205 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 82.6 ± 7.4 | 84.0 ± 6.4 | 82.8 ± 7.0 | 82.6 ± 7.1 | <0.001 |

| Male | 881 (40) | 315 (48) | 223 (56) | 124 (60) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m² | 25.9 ± 5.3 | 25.6 ± 4.6 | 25.9 ± 4.64.6 | 26.1 ± 4.4 | 0.488 |

| Tobacco | 70 (3) | 17 (3) | 15 (4) | 13 (6) | 0.067 |

| Hypertension | 1452 (66) | 478 (73) | 275 (69) | 151 (74) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 472 (21) | 175 (27) | 112 (28) | 71 (35) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 821 (37) | 325 (50) | 213 (54) | 123 (60) | <0.001 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 19.3 ± 12.8 | 20.7 ± 13.0 | 21.5 ± 13.3 | 21.9 ± 13.5 | <0.001 |

| NYHA functional class III or IV | 1675 (77) | 501 (77) | 317 (80) | 152 (75) | 0.468 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 97 (4) | 115 (18) | 100 (25) | 52 (25) | <0.001 |

| Previous balloon aortic valvuloplasty | 351 (16) | 108 (17) | 104 (26) | 46 (22) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 217 (10) | 68 (10) | 41 (10) | 26 (13) | 0.649 |

| Aortic abdominal aneurysm | 69 (3) | 30 (5) | 22 (5) | 21 (10) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 305 (14) | 120 (18) | 92 (23) | 67 (33) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 557 (25) | 159 (24) | 90 (23) | 39 (19) | 0.166 |

| Dialysis | 57 (3) | 21 (3) | 10 (2) | 7 (3) | 0.763 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 607 (28) | 155 (24) | 80 (21) | 53 (26) | 0.010 |

| Permanent pacemaker | 312 (14) | 93 (14) | 58 (15) | 25 (12) | 0.853 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 426 (19) | 97 (15) | 61 (15) | 27 (13) | 0.009 |

| Extensively calcified aorta | 154 (7) | 39 (6) | 37 (9) | 36 (18) | <0.001 |

| Prior chest‐wall irradiation | 142 (6) | 38 (6) | 32 (8) | 7 (3) | 0.154 |

| Chest wall deformity | 59 (3) | 14 (2) | 12 (3) | 1 (1) | 0.211 |

| Previous AVR surgery | 40 (2) | 2 (<1) | 4 (1) | 1 (<1) | 0.016 |

| Device | 0.229 | ||||

| Balloon expandable | 1423 (65) | 447 (69) | 270 (68) | 134 (65) | |

| Medtronic CoreValve | 765 (35) | 201 (31) | 126 (32) | 71 (35) | |

| Significant stenosis | |||||

| LMCA | — | — | 47 (12) | 24 (49) | <0.001 |

| LAD | — | 319 (49) | 300 (76) | 189 (92) | <0.001 |

| LCX | — | 122 (19) | 233 (59) | 233 (87) | <0.001 |

| RCA | — | 209 (32) | 214 (54) | 205 (100) | <0.001 |

| Echocardiographic findings | |||||

| Aortic valve area, cm² | 0.66 ± 0.18 | 0.68 ± 0.19 | 0.68 ± 0.18 | 0.68 ± 0.18 | 0.122 |

| Mean aortic valve gradient, mm Hg | 50.2 ± 17.1 | 47.3 ± 15.6 | 46.1 ± 16.1 | 45.2 ± 15.2 | <0.001 |

| LVEF, % | 54.8 ± 14.0 | 53.6 ± 14.1 | 50.6 ± 15.2 | 50.5 ± 13.9 | <0.001 |

| Moderate or severe mitral regurgitation (grade ≥3/4) | 40 (2) | 13 (2) | 7 (2) | 1 (<1) | 0.387 |

| TAVR approach | <0.001 | ||||

| Transfemoral approach | 1716 (79) | 482 (74) | 281 (71) | 121 (59) | |

| Transapical approach | 283 (13) | 113 (17) | 66 (17) | 44 (22) | |

| Subclavian approach | 116 6) | 28 (4) | 24 (6) | 22 (22) | |

| Other | 62 (3) | 24 (4) | 24 (6) | 17 (8) | |

| Procedural success | 2135 (97) | 627 (97) | 386 (97) | 199 (97) | 0.882 |

| Hospitalization stay, d | 11.3 ± 8.6 | 11.1 ± 8.8 | 11.3 ± 9.3 | 10.9 ± 7.3 | 0.940 |

Abbreviations: AVR, aortic valve replacement; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LAD, left anterior coronary artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; LMCA, left main coronary artery; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RCA, right coronary artery; SD, standard deviation; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Data are presented as no. (%) or mean ± SD.

The transfemoral approach was less frequently used as the severity of CAD increased. Balloon‐ and self‐expandable devices were similarly implanted, and the procedural success was similar in all groups (97%). Clinical and procedural characteristics according to the localization of CAD (ie, LMCA, LAD, LCX, and right coronary artery [RCA]) are presented in Supporting Tables 1 and 2 in the online version of this article.

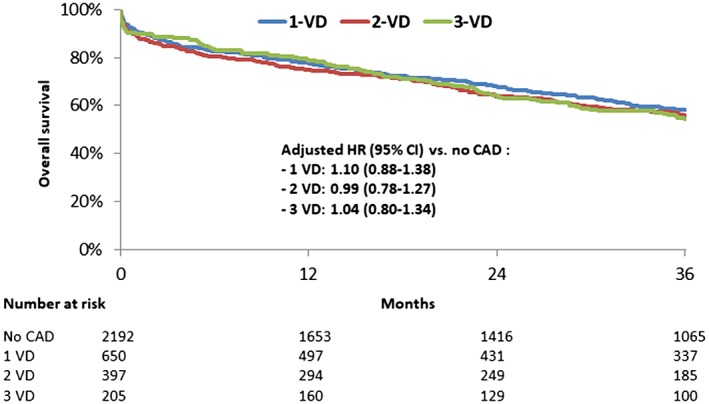

3.2. Clinical outcomes according to the extent of CAD

The rate of complications including periprosthetic aortic regurgitation (ie, ≥2) and the need for a new pacemaker was similar in all subgroups as well as the 30‐day mortality (Table 2). The mortality rate at the 3‐year follow‐up was 41%, 44%, and 45% in patients with 1‐, 2‐ and 3‐vessel disease, respectively (Figure 1). In Cox multivariate analyses, CAD was not associated with higher mortality at 3 years after full adjustment (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.91; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.81‐1.03; P = 0.12). Conversely, the extent of CAD was not associated with higher mortality at 3 years (no CAD vs 1‐vessel disease [VD]: HR: 1.10; 95% CI: 0.88‐1.38; P = 0.40; no CAD vs 2 VD: HR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.78‐1.27; P = 0.96; no CAD vs 3 VD: HR: 1.04; 95% CI: 0.80‐1.34; P = 0.79).

Table 2.

Cardiovascular events according to extent of coronary artery disease

| 0, n = 2192 | 1, n = 650 | 2, n = 397 | 3, n = 205 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke/TIA | 127 (6) | 43 (7) | 23 (6) | 17 (8) | 0.49 |

| Myocardial infarction | 28 (1) | 10 (2) | 5 (1) | 7 (3) | 0.11 |

| Major bleeding | 244 (11) | 69 (11) | 47 (12) | 27 (13) | 0.76 |

| Major vascular events | 143 (7) | 52 (8) | 25 (6) | 14 (7) | 0.59 |

| Endocarditis | 26 (1) | 5 (1) | 4 (1) | 1 (<1) | 0.68 |

| 30‐day mortality | 199 (9) | 58 (9) | 43 (11) | 20 (10) | 0.70 |

| 3‐year mortality | |||||

| From any cause | 925 (42) | 266 (41) | 173 (44) | 92 (45) | 0.72 |

| From cardiovascular cause | 294 (16) | 91 (16) | 68 (20.5) | 34 (19.5) | 0.25 |

| AR ≥2 | 302 (16) | 83 (15) | 50 (15) | 23 (13) | 0.62 |

| Need for new PM | 376 (20) | 129 (23) | 79 (23) | 45 (25) | 0.16 |

Abbreviations: AR, aortic regurgitation; PM, pacemaker; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Data are presented as % (n) or mean ± SD

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival at 3‐year follow‐up according to CAD. Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; VD, vessel disease

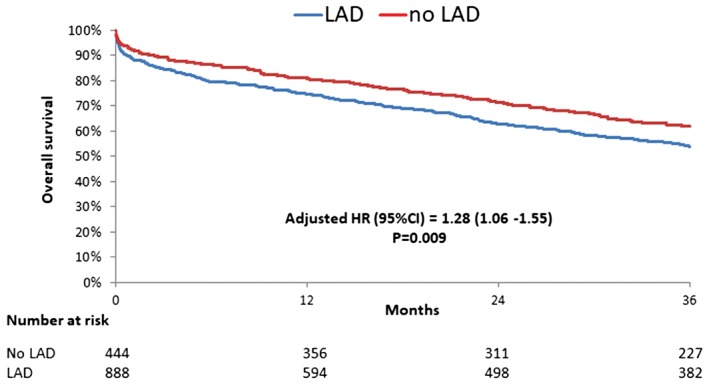

Significant LAD disease was associated with higher mortality rates at 3 years (adjusted HR: 1.28; 95% CI: 1.06‐1.55; P = 0.009) (Figure 2) as opposed to non‐LAD lesion (LCX, HR: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.75‐1.07; P = 0.22; RCA, HR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.82‐1.18; P = 0.85). Male gender (HR: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.09‐1.57; P = 0.003), EuroSCORE‐1 (HR: 1.02; 95% CI: 1.01‐1.02; P < 0.001), and chronic kidney disease (HR: 1.42; 95% CI: 1.09‐1.87; P = 0.01) were associated with higher mortality at 3 years, whereas the transfemoral approach was associated with a lower rate of 3‐year mortality (HR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.65‐0.95; P = 0.01).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival at 3‐year follow‐up according to LAD artery disease (in patients with coronary artery disease). Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LAD, left anterior descending

Propensity score matching was performed to build 2 matched cohorts of 428 patients, with similar baseline characteristics (see Supporting Table 4 in the online version of this article. Similarly, significant LAD disease was associated with higher mortality rates at 3 years (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article.

4. DISCUSSION

The present analysis of the FRANCE‐2 nationwide registry indicates that CAD is identified in one‐third of patients undergoing TAVR but is not associated with mortality after adjustment for clinical presentation and management. This finding was observed irrespective of CAD extent. However, significant LAD disease was associated with higher mortality rates at 3 years, raising the question of routine percutaneous revascularization prior to TAVR.

4.1. Prevalence of CAD in patients with AS

CAD and AS share pathophysiological mechanisms accounting for their coexistence.25 We report a prevalence of CAD similar to other TAVR registries but much higher than in the surgical literature.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 This relatively low prevalence may be explained by the exclusion of CABG patients. As previously described, CAD was associated with more comorbidity including male gender, diabetes mellitus, extracardiac arterial disease and ascending aorta calcification, higher Canadian Cardiovascular Society class, lower ejection fraction, and higher median logistic EuroSCORE.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23

4.2. Prognosis according to extent of CAD

After multivariate adjustment, the presence and extent of CAD were not associated with survival, either at 30 days or over the longer term (3 years). These data are consistent with smaller studies, and a recent meta‐analysis of 2472 patients26 where follow‐up was short (mean 452 days, IQR: 357–585 days). In contrast, another study performed in the United States demonstrated that concomitant CAD, defined as patients with a history of either surgical or percutaneous revascularization, had higher 30‐day mortality than those without a history of coronary intervention.27

4.3. Independent factors related to CAD associated with clinical impact

Recently, the angiographic SYNTAX score has been used to assess the impact of CAD severity on clinical outcomes in 445 patients.22 Stefanini et al. demonstrated that patients with SYNTAX scores >22 receive less complete revascularization and have a higher risk of cardiovascular death, stroke, or myocardial infarction than patients without CAD or low SYNTAX scores at 30 days (HR: 1.44; 95% CI: 0.58‐3.58) and at 1 year (HR: 2.24; 95% CI: 1.18‐4.23). The SYNTAX score was unfortunately not collected in the FRANCE‐2 registry. However, CAD extent was not a prognostic indicator, and only the presence of a significant lesion of the LAD was associated with higher long‐term mortality. To our knowledge, this is the first study that shows that the localization of CAD could have a clinical impact in patients undoing TAVR.

4.4. Myocardial revascularization before TAVR

Current guidelines recommend treatment of significant CAD by concomitant CABG in patients undergoing surgical AVR.28, 29 However, there is no consensus on the optimal treatment of CAD in high‐risk patients requiring TAVR. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) should be considered in patients with an indication for TAVR in whom coronary artery diameter stenosis is >70% in proximal segments.28 In this population, incomplete coronary revascularization is, however, a dominant baseline feature. In practice, chronic total occlusion, distal lesions, or small arteries are not likely to have been treated in such a population, again without difference according to the vessel involved. The current ACTIVATION trial (Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Prior to Transaortic Valve Implantation: A Randomized Controlled Trial; ISRCTN75836930) tests the hypothesis of noninferiority of pre‐TAVR PCI vs medical management of significant coronary lesions.30 Other randomized trials such as SURTAVI (Surgical Replacement and TransAortic Valve Implantation) and PARTNER II (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves), have recently demonstrated that percutaneous strategy for the treatment of AS and CAD are noninferior with surgical strategies.31, 32

4.5. Strengths and limitations

Our study displays the same limitations as all observational studies precluding any causality between parameters that are correlated. Comparisons between patients according to CAD status were obviously not randomized, and despite careful adjustments on a large number of potentially confounding variables, and the use of statistical adjustment, the results can only be considered as hypothesis generating. The SYNTAX score and precise localization of the lesions in each artery were not available. In addition, previous history of PCI and data related to myocardial revascularization before TAVR were not available in the database, which represents the main limitation of the present study. However, we can consider that pre‐TAVR PCI was performed according to each heart team's decisions, and that only severe stenoses (ie, >70%) were treated with little difference in the indications according to the 3 major epicardial vessels (LAD, LCX, and RCA).

5. CONCLUSION

In the FRANCE‐2 registry, the presence and extent of CAD were not associated with higher early and long‐term mortality in patients undergoing TAVR. Several studies reported that incomplete coronary revascularization is a dominant baseline feature in this high‐risk population. However, our data suggest that only a significant lesion of the LAD is associated with higher mortality. This latter finding raises the question of the opportunity of routine revascularization of the LAD in patients undergoing TAVR.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Supplementary File

Table S1. Patient Characteristics at Baseline According to Localization of Coronary Artery Disease.

Table S2. Patient Characteristics at Baseline According to Localization of Coronary Artery Disease

Table S3. Patient Characteristics at Baseline according to Left Anterior Descending Disease in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease Before Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are deeply indebted to the patients who participated and to all of the physicians who took care of them.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Puymirat E, Didier R, Eltchaninoff H, et al. Impact of coronary artery disease in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement: Insights from the FRANCE‐2 registry. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:1316–1322. 10.1002/clc.22830

Author contributions: Etienne Puymirat, Romain Didie, Martine Gillard, and Didier Blanchard contributed equally to the work.

Funding information Edwards Lifesciences, Grant/Award number: Grant; Medtronic, Grant/Award number: Grant; The FRANCE‐2 registry was supported by Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic.

REFERENCES

- 1. Otto CM, Lind BK, KitzmanDW, et al. Association of aortic‐valve sclerosis with cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:142–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carabello BA, Paulus WJ. Aortic stenosis. Lancet. 2009;373:956–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goel SS, Ige M, Tuzcu EM, et al. Severe aortic stenosis and coronary artery disease implications for management in the transcatheter aortic valve replacement era: a comprehensive review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter aortic‐valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic‐valve replacement in high‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2187–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eltchaninoff H, Prat A, Gilard M, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: early results of the FRANCE (FRench Aortic National CoreValve and Edwards) registry. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rodes‐Cabau J, Webb JG, Cheung A, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for the treatment of severe symptomatic aortic stenosis in patients at very high or prohibitive surgical risk: acute and late outcomes of the multicenter Canadian experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1080–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomas M, Schymik G, Walther T, et al. One‐year outcomes of cohort 1 in the Edwards SAPIEN Aortic Bioprosthesis European Outcome (SOURCE) registry: the European registry of transcatheter aortic valve implantation using the Edwards SAPIEN valve. Circulation. 2011;124:425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Himbert D, Descoutures F, Al‐Attar N, et al. Results of transfemoral or transapical aortic valve implantation following a uniform assessment in high‐risk patients with aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lefevre T, Kappetein AP, Wolner E, et al. One year follow‐up of the multi‐centre European PARTNER transcatheter heart valve study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Walther T, Kasimir MT, Doss M, et al. One‐year interim follow‐up results of the TRAVERCE trial: the initial feasibility study for transapical aortic‐valve implantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:532–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Svensson LG, Dewey T, Kapadia S, et al. United States feasibility study of transcatheter insertion of a stented aortic valve by the left ventricular apex. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grube E, Buellesfeld L, Mueller R, et al. Progress and current status of percutaneous aortic valve replacement: results of three device generations of the CoreValve Revalving system. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Petronio AS, De Carlo M, Bedogni F, et al. Safety and efficacy of the subclavian approach for transcatheter aortic valve implantation with the CoreValve revalving system. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Piazza N, Grube E, Gerckens U, et al. Procedural and 30‐day outcomes following transcatheter aortic valve implantation using the third generation (18 Fr) corevalve revalving system: results from the multicentre, expanded evaluation registry 1‐year following CE mark approval. EuroIntervention. 2008;4:242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zahn R, Gerckens U, Grube E, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: first results from a multi‐centre real‐world registry. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tamburino C, Capodanno D, Ramondo A, et al. Incidence and predictors of early and late mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation in 663 patients with severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2011;123:299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moat NE, Ludman P, de Belder MA, et al. Long‐term outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation in high‐risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: the U.K. TAVI (United Kingdom Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation) Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2130–2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wenaweser P, Pilgrim T, Kadner A, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with severe aortic stenosis at increased surgical risk according to treatment modality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2151–2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gilard M, Eltchaninoff H, Iung B, et al. Registry of transcatheter aortic‐valve implantation in high‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1705–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beckmann A, Hamm C, Figulla HR, et al. The German Aortic Valve Registry (GARY): a nationwide registry for patients undergoing invasive therapy for severe aortic valve stenosis. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;60:319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stefanini GG, Stortecky S, Cao D, et al. Coronary artery disease severity and aortic stenosis: clinical outcomes according to SYNTAX score in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2530–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Snow TM, Ludman P, Banya W, et al. Management of concomitant coronary artery disease in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the United Kingdom TAVI Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2015;199:253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leon MB, Piazza N, Nikolsky E, et al. Standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation clinical trials: a consensus report from the Valve Academic Research Consortium. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:205–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Otto CM, Kuusisto J, Reichenbach DD, et al. Characterization of the early lesion of 'degenerative' valvular aortic stenosis. Histological and immunohistochemical studies. Circulation. 1994;90:844–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. D'Ascenzo F, Conrotto F, Giordana F, et al. Mid‐term prognostic value of coronary artery disease in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a meta‐analysis of adjusted observational results. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2528–2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dewey TM, Brown DL, Herbert MA, et al. Effect of concomitant coronary artery disease on procedural and late outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:758–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Members Authors/Task Force, Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al. 2014. ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio‐Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541–2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017. AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:252–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Khawaja MZ, Wang D, Pocock S, et al. The percutaneous coronary intervention prior to transcatheter aortic valve implantation (ACTIVATION) trial: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, et al; SURTAVI Investigators. Surgical or transcatheter aortic‐valve replacement in intermediate‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1321–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moat NE. Will TAVR become the predominant method for treating severe aortic stenosis? N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1682–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Supplementary File

Table S1. Patient Characteristics at Baseline According to Localization of Coronary Artery Disease.

Table S2. Patient Characteristics at Baseline According to Localization of Coronary Artery Disease

Table S3. Patient Characteristics at Baseline according to Left Anterior Descending Disease in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease Before Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement