Abstract

Background

Correlation of increased copeptin levels with various cardiovascular diseases has been described. The clinical use of copeptin levels in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) has not been investigated before.

Hypothesis

In this study, we aimed to investigate the prognostic value of copeptin levels in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

Methods

HCM was defined as presence of left ventricular wall thickness ≥15 mm in a subject without any concomitant disease that may cause left ventricular hypertrophy. Levels of copeptin and plasma N‐terminal probrain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) were evaluated prospectively in 24 obstructive HCM patients, 36 nonobstructive HCM patients, and 36 age‐ and sex‐matched control subjects. Blood samples were collected in the morning between 7 and 9 am after overnight fasting. Patients were followed for 24 months. Hospitalization with diagnosis of heart failure/arrhythmia, implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator implantation, and cardiac mortality were accepted as adverse cardiac events.

Results

Copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels were higher in the HCM group compared with controls (14.1 vs 8.4 pmol/L, P < 0.01; and 383 vs 44 pg/mL, P < 0.01, respectively). Copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels were higher in the obstructive HCM subgroup compared with the nonobstructive HCM subgroup (18.3 vs 13.1 pmol/L, P < 0.01; and 717 vs 223 pg/mL, P < 0.01, respectively). In multivariable logistic regression analysis, copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels remained as independent predictors of heart failure (P < 0.01 for both) and adverse cardiac events (P < 0.01 for both).

Conclusions

Copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels were significantly higher in patients with obstructive HCM, and higher levels were associated with worse outcome.

Keywords: Heart failure/cardiac transplantation/cardiomyopathy/myocarditis, Imaging, echocardiography, Cardiovascular, biochemistry

1. Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a complex, genetic cardiac disease caused by a variety of mutations in genes encoding sarcomeric proteins with a marked heterogeneity in clinical expression, natural history, and prognosis. HCM is characterized by cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, myofibrillar disarray, and interstitial fibrosis, resulting in regional and global abnormal generation of contractile force, hindered relaxation, and abnormal diastolic filling.1

Plasma levels of N‐terminal probrain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) have been reported to be correlated with the severity of left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) gradient, and adverse cardiovascular events in HCM patients.2, 3 The clinical use of other neurohormones such as atrial natriuretic peptide,4 endothelin‐15 and adrenomedullin5 has also been investigated in HCM.

Arginine vasopressin (AVP), also termed antidiuretic hormone, has an important role in cardiovascular homeostasis. However, measurement of AVP levels is technically challenging due to its small size, short plasma half‐life, and interaction with platelets in the serum.6 Copeptin is the stable C‐terminal part of pro‐AVP, which is released with AVP after hemodynamic or osmotic stimuli and is also an endocrine stress hormone.7 Plasma copeptin level is more feasible to measure and may be used to estimate the AVP activity. Increased copeptin levels are associated with acute dyspnea,8 sepsis,9 and diabetes mellitus (DM),10 and poor prognosis in acute myocardial infarction (MI)11 and heart failure (HF).12 The correlation of copeptin levels with presence of HCM and adverse cardiac events in HCM has not yet been investigated in the literature.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

We screened hospital records between January 2011 and January 2013, and 79 patients with a diagnosis of HCM were recruited. The medical records of these subjects were further investigated for study inclusion. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was defined as LV hypertrophy (LV wall thickness ≥15 mm) in the absence of any other concomitant disease that may cause LV hypertrophy. Patients with acute exacerbation of HF, decreased ejection fraction (<50%), significant coronary artery disease (CAD), severe renal dysfunction (estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min/m2), or uncontrolled hypertension (HTN; blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg with or without antihypertensive medications) were excluded. Finally, 60 subjects were included in the study group. For a control group, 36 patients who underwent transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) examination and were found to have normal LV thickness were recruited. Patients with established CAD, uncontrolled HTN, or renal dysfunction and patients with symptoms of HF corresponding to New York Heart Association (NYHA) class ≥ III were not included in the control group. In the control group, only 2 patients had NYHA class II symptoms and the regarding subjects were in NYHA class I.

All of the patients were recalled for the study, and the clinical properties, symptoms, NYHA class, and medications used were recorded. In addition, HCM patients had undergone physical examination, TTE, and 24‐hour ambulatory electrocardiographic (ECG) recording. Patients were checked every 3 months, and physical examination findings and ECGs were recorded. In case of symptoms, physical examination, TTE, and 24‐hour ambulatory ECGs were performed. Patients with acute HF or arrhythmias causing hemodynamic compromise were hospitalized for further investigation and treatment. All participants provided a written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee.

2.2. Definitions

HTN was defined as a systolic pressure >140 mm Hg and/or a diastolic pressure >90 mm Hg, or if the individual was taking antihypertensive medications. DM was defined as a fasting glucose level >126 mg/dL and/or if the patient was taking antidiabetic medication. Hyperlipidemia was defined as elevated total serum cholesterol levels >240 mg/dL. Individuals who reported smoking ≥1 cigarette per day during the year before examination were classified as smokers. The functional capacity of the subjects was defined according to the NYHA classification of HF. Adverse cardiovascular events were defined as hospitalization due to heart failure/arrhythmias, implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator (ICD) implantation, and cardiac mortality.

2.3. Echocardiographic Examination

All individuals were examined by 2 experienced echocardiographers who were blinded to the laboratory data and clinical properties of the subjects. The studies were performed with the iE33 xMATRIX Echocardiography System (Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). The standard evaluation included M‐mode, 2‐dimensional, and Doppler studies according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography.13 LVOT obstruction was defined as presence of a peak instantaneous outflow gradient of ≥30 mm Hg under basal (at rest) conditions or with physiologic provocation (Valsalva maneuver or exercise). Mitral septal early annular velocity (e′) was measured using tissue Doppler imaging and the ratio of E to e′ velocity (E/e′) was calculated.

2.4. Copeptin and NT‐pro BNP Levels

Venous blood samples were obtained from subjects between 7 and 9 am after overnight fasting. Serum copeptin concentrations were measured on the principle of competitive enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Wuhan ElAab Science Co. Ltd., Wuhan, China). Serum NT‐proBNP levels were measured by immunoassay with detection by electrochemiluminescence (Roche Diagnostics, São Paulo, SP, Brazil) using 20 μL of serum and polyclonal antibodies that detect epitopes in the N‐terminal region (amino acids 1–76) of the proBNP (108 amino acids). The assay is fully automated using the Elecsys 2010 automated analyzer (Roche Diagnostics).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range, 25th‐75th percentile) for parametric variables, and as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Continuous variables were checked for the normal distribution assumption using Kolmogorov‐Smirnov statistics. Categorical variables were tested by the Pearson χ2 test and Fisher exact test. Differences between patients and control subjects were evaluated using the Kolmogorov‐Smirnov test or the Student t test when appropriate. Receiver operating curves (ROC) were analyzed to assess the best cutoff values of copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels to discriminate HCM in the study population. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the univariate and multivariate predictors of adverse cardiovascular events and were reported as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for 1‐unit increase of each numerical parameter. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical studies were carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences software version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

3. Results

A total of 60 patients with HCM and 36 control subjects were included in the study. Demographic and clinical properties of the study groups are presented in Table 1. The groups were comparable regarding age, sex, and frequency of HTN, DM, and hyperlipidemia. In the HCM group, 11 patients had family history positive for HCM, 5 patients had syncope, and 7 patients had atrial fibrillation. Forty‐one patients had NYHA class I, 14 patients had class II, and 5 patients had class III symptoms in the HCM group; in the control group, 2 patients had NYHA class II symptoms and 34 patients had class I symptoms (P < 0.01). The frequency of β‐blocker usage was higher in the HCM group (P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic and clinical properties between the HCM and control groups

| HCM Group, n = 60 | Control Group, n = 36 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 42.7 ± 13.3 | 40.1 ± 8.9 | 0.33 |

| Male sex | 31 (51) | 17 (47) | 0.83 |

| HTN | 18 (30) | 12 (33) | 0.65 |

| DM | 9 (15) | 5 (14) | 0.38 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 15 (25) | 10 (28) | 0.82 |

| Family history | 11 (18) | 0 | — |

| AF | 7 (12) | 0 | — |

| Syncope | 5 (8) | 0 | — |

| Obstructive HCM | 24 (40) | — | — |

| NYHA class | |||

| I | 41 (68) | 34 (95) | |

| II | 14 (24) | 2 (5) | <0.01 |

| III | 5 (8) | 0 | |

| β‐Blocker used | 51 (85) | 8 (13) | <0.01 |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; DM, diabetes mellitus; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HTN, hypertension; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SD, standard deviation.

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise noted.

The echocardiographic properties of the study groups are depicted in Table 2. The mean thickness of the interventricular septum (IVS) was 20.5 ± 4.7 mm, and of the posterior wall 14.6 ± 3.6 mm, which were significantly higher in the HCM group. The left ventricular diastolic diameter and left ventricular systolic diameter were smaller and the left atrial (LA) anteroposterior diameter was larger in the HCM group compared with the controls. In addition, the E/A ratio was lower and E/e′ was higher in the HCM group. The clinical and echocardiographic parameters of subjects in obstructive and nonobstructive HCM groups are summarized in Table 3. In 24 patients (40%), the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) gradient was ≥30 mm Hg, compatible with obstructive HCM. The median LVOT gradient was 53 (40‐70) mm Hg in the obstructive HCM group and 10 (7‐12) mm Hg in the nonobstructive HCM group. The mean IVS diameter and E/e′ ratio were significantly higher in obstructive HCM group. The other echocardiographic parameters were similar between the 2 groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of echocardiographic parameters and NT‐proBNP and copeptin levels in control and HCM groups

| HCM Group, n = 60 | Control Group, n = 36 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiographic parameters | |||

| LVDD, mm | 44.7 ± 4.6 | 47.2 ± 3.9 | <0.01 |

| LVSD, mm | 27.5 ± 3.6 | 31.6 ± 3.6 | <0.01 |

| IVS thickness, mm | 20.5 ± 4.7 | 9.5 ± 0.9 | <0.01 |

| PW thickness, mm | 14.6 ± 3.6 | 8.9 ± 0.8 | <0.01 |

| LVEF, % | 61.9 ± 4.1 | 60.5 ± 2.2 | 0.12 |

| LA‐AP diameter, mm | 38.7 ± 6.1 | 30.1 ± 2.1 | <0.01 |

| Mitral regurgitation | |||

| +1 | 36 (60) | 7 (19) | <0.01 |

| +2 | 7 (12) | 1 (3) | |

| E/A | 0.85 ± 0.31 | 1.26 ± 0.28 | <0.01 |

| E/e′ | 13.1 ± 3.2 | 7.1 ± 0.6 | <0.01 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 31.8 ± 8.4 | 29.7 ± 4.2 | 0.17 |

| Cr, mg/dL | 0.88 ± 0.17 | 0.83 ± 0.11 | 0.06 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 98 ± 9 | 96 ± 8 | 0.19 |

| Copeptin, pmol/L | 14.1 (11.4‐22.1) | 8.4 (7.7‐9.2) | <0.01 |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 383 (170‐889) | 44 (17‐111) | <0.01 |

Abbreviations: A, peak late diastolic transmitral flow velocity; Cr, creatinine; E, peak early diastolic transmitral flow velocity; e′, peak early diastolic mitral annular velocity; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; IQR, interquartile range; IVS, interventricular septum; LA‐AP, left atrial anteroposterior diameter; LVDD, left ventricular diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVSD, left ventricular systolic diameter; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal probrain natriuretic peptide; PW, posterior wall.

Data are presented as n (%), mean ± SD, or median (IQR).

Table 3.

Comparison of clinical properties and echocardiographic parameters between obstructive and nonobstructive HCM subgroups

| Obstructive HCM, n = 24 | Nonobstructive HCM, n = 36 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 41.1 ± 12.9 | 43.8 ± 15.3 | 0.48 |

| Male sex | 12 (50) | 19 (53) | 0.83 |

| HTN | 8 (33) | 9 (25) | 0.48 |

| DM | 5 (21) | 4 (11) | 0.71 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 7 (29) | 8 (22) | 0.75 |

| Family history | 7 (29) | 4 (11) | 0.09 |

| AF | 7 (29) | 0 | — |

| Syncope | 4 (17) | 1 (3) | 0.35 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | |||

| LVDD, mm | 44.5 ± 4.4 | 44.8 ± 4.9 | 0.92 |

| LVSD, mm | 26.5 ± 3.2 | 28.1 ± 3.8 | 0.10 |

| IVS thickness, mm | 22.6 ± 4.6 | 19.2 ± 4.3 | 0.04 |

| PW thickness, mm | 14.2 ± 3.2 | 14.7 ± 3.8 | 0.46 |

| LA‐AP, mm | 37.7 ± 4.5 | 39.4 ± 6.8 | 0.29 |

| LVOT gradient, mm Hg | 53 (40‐70) | 10 (7‐12) | <0.01 |

| E/A | 0.82 ± 0.29 | 0.86 ± 0.32 | 0.65 |

| E/e′ | 14.6 ± 3.7 | 12.2 ± 2.4 | <0.01 |

| Copeptin, pmol/L | 18.3 (13.5‐23.6) | 13.1 (9.1‐17.7) | <0.01 |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 717 (380‐1161) | 223 (134‐719) | <0.01 |

| Adverse events during follow‐up | |||

| Acute HF | 9 (37) | 7 (19) | 0.12 |

| ICD implantation | 6 (25) | 3 (8) | 0.07 |

| Hospitalization | 10 (42) | 9 (25) | 0.17 |

| Cardiac mortality | 3 (12) | 4 (11) | 0.87 |

| Adverse cardiac events | 10 (42) | 10 (28) | 0.26 |

Abbreviations: A, peak late diastolic transmitral flow velocity; AF, atrial fibrillation; DM, diabetes mellitus; E, peak early diastolic transmitral flow velocity; e′, peak early diastolic mitral annular velocity; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HF, heart failure; HTN, hypertension; ICD, implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator; IQR, interquartile range; IVS, interventricular septum; LA‐AP, left atrial anteroposterior diameter; LVDD, left ventricular diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; LVSD, left ventricular systolic diameter; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal probrain natriuretic peptide; SD, standard deviation; PW, posterior wall.

Data are presented as n (%), mean ± SD, or median (IQR).

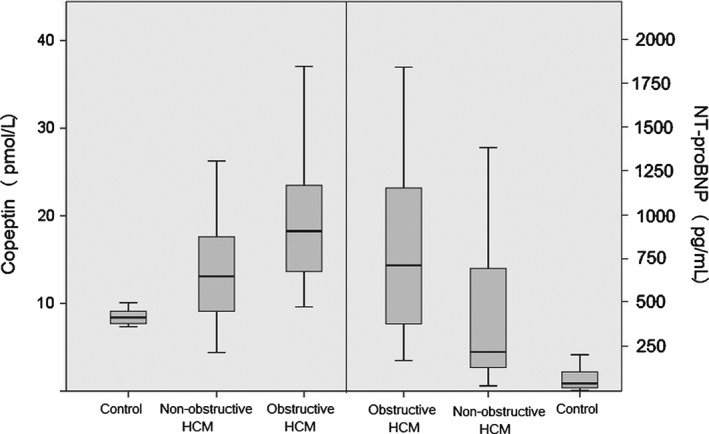

Copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels were significantly higher in the HCM group compared with the controls (14.1 (11.4‐22.1) vs 8.4 (7.7‐9.2) pmol/L, P < 0.01; and 383 (170‐889) vs 44 (17‐111) pg/mL, P < 0.01, respectively; Figure 1). In subgroup analysis, copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels were significantly higher in the obstructive HCM subgroup compared with the nonobstructive HCM subgroup (18.3 (13.5‐23.6) vs 13.1 (9.1‐17.7) pmol/L, P < 0.01; and 717 (380‐1161) vs 223 (134‐719) pg/mL, P < 0.01, respectively; Table 3). Patients with NYHA class II symptoms had significantly higher copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels compared with patients with class I symptoms (17.8 [9.9] vs 14.1 [11.2] pmol/L, P < 0.01; and 769 [935] vs 359 [547] pg/mL, P < 0.01, respectively).

Figure 1.

Box‐plot graph showing the copeptin (left side) and NT‐proBNP (right side) levels in obstructive HCM, nonobstructive HCM, and control groups. Abbreviations: HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal probrain natriuretic peptide.

In univariate correlation analysis, copeptin levels were significantly correlated with NT‐proBNP levels (r = 0.287, P < 0.01), LVOT gradient (r = 0.370, P < 0.01), IVS diameter (r = 0.445, P < 0.01), LA diameter (r = 0.253, P < 0.01), and E/e′ ratio (r = 0.469, P < 0.01). Plasma NTproBNP levels were significantly correlated with LVOT gradient (r = 0.482, P < 0.01), IVS diameter (r = 0.456, P < 0.01), LA diameter (r = 0.253, P < 0.01), and E/e′ ratio (r = 0.529, P < 0.01).

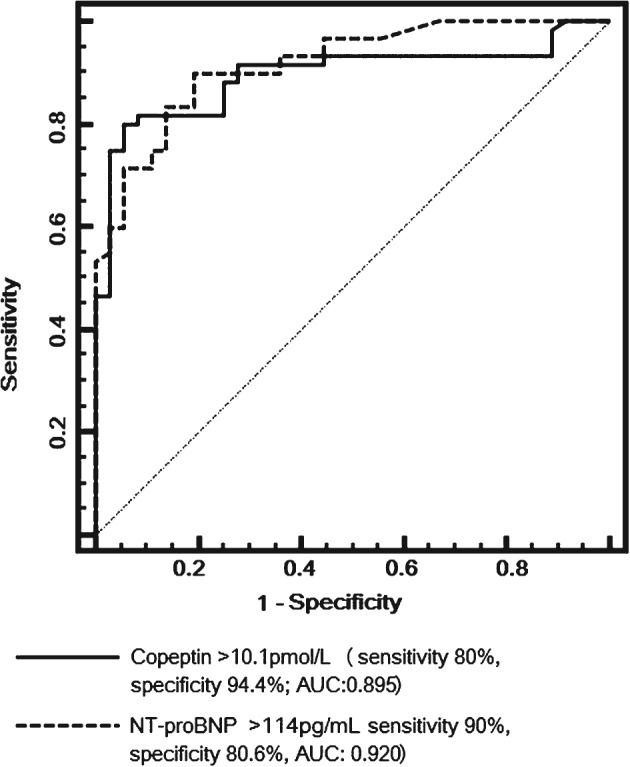

In ROC analysis, copeptin levels >10.1 pmol/L (sensitivity 80%, specificity 94.4%, AUC: 0.895, P = 0.01) and NT‐proBNP levels > 114 pg/mL (sensitivity 90%, specificity 80.6%, AUC: 0.920, P = 0.01) predicted HCM in the study population (Figure 2). When AUCs were compared, the discriminative properties of copeptin and NT‐proBNP measurements were not statistically different (P = 0.63).

Figure 2.

ROC curve analysis of copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels for diagnosis of HCM in the study population. Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal probrain natriuretic peptide; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

During a follow‐up period of 24 months, 16 (27%) patients had an episode of acute HF, 9 (15%) patients had ICD implantation, 19 (32%) patients were hospitalized due to cardiac diseases, and 7 (11.6%) patients died. The composite endpoint of hospitalization, ICD implantation, and death occurred in 20 HCM patients (33%). In the HCM subgroup, when deceased patients were compared with the surviving ones, copeptin levels were significantly higher but NT‐proBNP levels were not significantly different (22.4 [9.3] vs 13.5 [9.2] pmol/L, P = 0.01; and 490 [1052] vs 370 [681] pg/mL, P = 0.78, respectively). When patients who had an episode of acute HF were compared with the patients who did not, copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels were significantly higher in the HCM group compared with the controls (22.6 [9.3] vs 13.5 [8.5] pmol/L, P = 0.02; and 838 [800] vs 285 [595] pg/mL, P < 0.01, respectively). In addition, in patients with an adverse cardiac event (20 cases), copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels were significantly higher compared with adverse event–free patients (18.6 [9.2] vs 13.1 [8.3] pmol/L, P < 0.01; and 749 [838] vs 285 [570] pg/mL, P < 0.01, respectively). When HCM patients were categorized according to the mean copeptin level in HCM group (< and ≥14.1pmol/L), patients in the high copeptin group experienced higher rates of mortality (7 vs 0 cases), acute HF (13 vs 3 cases), ICD implantation (8 vs 1 cases), hospitalization (15 vs 4 cases), and adverse cardiac events (16 vs 4 cases).

In binary logistic regression analysis, using a model adjusted for age, sex, IVS thickness, LVOT gradient, presence of HTN, and copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels, the copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels remained as the independent predictors of risk for acute HF (OR: 1.22, 95% CI: 1.06‐1.42, P < 0.01; and OR: 1.004, 95% CI: 1.001‐1.006, P < 0.01, respectively) and risk for adverse cardiac events (OR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.04‐1.31, P < 0.01; and OR: 1.003, 95% CI: 1.001‐1.004, P < 0.01, respectively). However, none of the parameters remained independently correlated with cardiac mortality (for copeptin: OR: 1.11, 95% CI: 0.98‐1.25, P = 0.09; and for NT‐proBNP: OR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.99‐1.002, P = 0.91).

4. Discussion

The major findings of this study are (1) copeptin levels are significantly higher in HCM patients, and especially in the obstructive HCM subgroup; (2) copeptin levels are strongly correlated with NT‐proBNP levels and echocardiographic indices of HCM, such as IVS thickness, LA diameter, and LVOT gradient; and (3) copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels independently predicted long‐term adverse cardiac events in HCM patients.

Arginine vasopressin (AVP) derives from a larger precursor peptide (pre‐pro‐vasopressin) along with copeptin, which is released in an equimolar ratio to AVP and is more stable in the circulation.14 The physiologic relevance of copeptin is still unsolved and copeptin levels are usually used to estimate the AVP levels. AVP, through its V1a and V2 receptor–mediated effects, seems to contribute to the progression of LV dysfunction by aggravating systolic and diastolic wall stress and by directly stimulating ventricular hypertrophy and myocardial remodeling.15 Also, AVP increases nitric oxide system activity in cardiac fibroblasts through nuclear factor κB activation, and its relation with myocardial fibrosis and vascular smooth‐muscle cells has been reported.16 Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a heterogeneous genetic disorder of myocardium, and fibrosis constitutes a major role in the pathophysiological mechanism of the disease. Thus, mechanisms associated with AVP and also copeptin may possibly be correlated with disease severity and clinical outcome in HCM. As previously reported, LV diastolic dysfunction is common in patients with HCM, which is a consequence of LV hypertrophy and fibrotic changes.17, 18, 19

Biomarkers providing additional prognostic information for HCM patients could be useful to assess the risk of arrhythmia, HF, and sudden cardiac death.20, 21, 22, 23 Plasma levels of natriuretic peptides and troponins (Tn) correlate with established disease markers, including LV thickness, symptom status, and LV hemodynamics by Doppler measurements. Both natriuretic peptides and Tns predict clinical risk in HCM independent of established risk factors, and their prognostic power is additive.24, 25, 26 In this study, we have found that copeptin levels are also associated with severity of the disease, and also higher copeptin levels may predict risk for adverse cardiac events. Even though we could not find an independent predictor of mortality in our study population, the risk for acute HF and adverse cardiac events was higher in patients with higher copeptin and NT‐proBNP levels. These finding are complementary to previous reports and also show the prognostic use of copeptin in risk stratification of HCM patients.

Previous studies have shown the clinical use of elevated copeptin levels in various cardiovascular diseases such as acute MI,11 HF,12 acute ischemic stroke,27 and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.28 Most of the studies focused on the use of copeptin as an early marker of myocardial ischemia in the emergency department. A recent meta‐analysis has shown that measurement of copeptin levels in addition to Tn improves the sensitivity and negative likelihood ratio for diagnosis of acute MI compared with Tn alone.29 Two landmark trials by Keller et al and Reichlin et al reported that copeptin levels >9.8 pmol/L and 14 pmol/L may be used as a diagnostic tool for acute coronary syndrome.30, 31 In our study, ROC analysis revealed that copeptin levels >10.1 pmol/L predict HCM, which is similar to the value suggested for diagnosis of MI. In addition, when HCM patients were categorized according to the mean copeptin level (≥14.1 pmol/L), we found that risk of adverse clinical events was higher in the high‐copeptin group. Even if the cutoff values in our study are close to those in previous reports, it is obvious that CAD and HCM are diverse clinical entities, and a possible common pathophysiological basis cannot be supposed using copeptin metabolism in this situation.

Copeptin levels have not been extensively investigated in patients with HCM. Liebetrau et al investigated copeptin‐release hemodynamics in 21 patients with HCM treated with transcoronary ablation of septal hypertrophy.32 They found that copeptin levels increased significantly 30 minutes after induction of MI and peaked at 90 minutes. Elmas et al assessed the correlation of various biochemical parameters, including copeptin, with cardiac fibrosis detected by magnetic resonance imaging in 40 patients with HCM.33 They did not find a relation between copeptin levels and degree of cardiac fibrosis in HCM. They found that LV and LA diameters and IVS thickness were higher in patients with cardiac fibrosis, but they did not classify patients as obstructive and nonobstructive HCM. In addition, they did not report any parameters regarding TTE, which is widely used in evaluation of patients with HCM. In our study, we have found that copeptin levels were correlated with NT‐proBNP levels and also echocardiographic parameters such as IVS thickness, LA diameter, and LVOT gradient, which are closely related with the severity of the disease. In addition, we found that copeptin levels may predict adverse cardiac events in HCM patients.

4.1. Study Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, the study population was relatively small. We have obtained only 1 measurement for copeptin and NT‐proBNP. Our findings do not imply a causal relationship between copeptin levels and HCM. The prognostic use of copeptin measurements for prediction of adverse events and especially risk of mortality warrants prospective studies with larger sample sizes.

5. Conclusion

Copeptin is a novel biochemical parameter that has clinical use in myocardial ischemia and HF. Our findings indicate that copeptin levels are elevated in patients with obstructive and nonobstructive HCM, and patients with higher copeptin levels may have a higher risk for future adverse cardiac events.

5.1. Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Sahin I, Gungor B, Ozkaynak B, Uzun F, Küçük SH, Avci II, Ozal E, Ayça B, Cetın S, Okuyan E and Dinckal MH. Higher copeptin levels are associated with worse outcome in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Clin Cardiol, 2017;40(1):32–37.

References

- 1. Maron MS, Olivotto I, Zenovich AG, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is predominantly a disease of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Circulation. 2006;114:2232–2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arteaga E, Araujo AQ, Buck P, et al. Plasma amino‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide quantification in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 2005;150:1228–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. D'Amato R, Tomberli B, Castelli G, et al. Prognostic value of N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide in outpatients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:1190–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Safrygina IuV, Gabrusenko SA, Ovchinnikov AG, et al. Cardiac natriuretic peptides in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [article in Russian]. Kardiologiia. 2007;47:50–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hamada M, Shigematsu Y, Kawakami H, et al. Increased plasma levels of adrenomedullin in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: its relation to endothelin‐I, natriuretic peptides and noradrenaline [published correction appears in Clin Sci (Lond). 1998;94:333]. Clin Sci (Lond). 1998;94:21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Singh Ranger G. The physiology and emerging roles of antidiuretic hormone. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56:777–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robertson GL, Mahr EA, Athar S et al. Development and clinical application of a new method for the radioimmunoassay of arginine vasopressin in human plasma. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:2340–2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Potocki M, Breidthardt T, Mueller A, et al. Copeptin and risk stratification in patients with acute dyspnea. Crit Care. 2010;14:R213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Struck J, Morgenthaler NG, Bergmann A. Copeptin, a stable peptide derived from the vasopressin precursor, is elevated in serum of sepsis patients. Peptides. 2005;26:2500–2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Enhörning S, Wang TJ, Nilsson PM, et al. Plasma copeptin and the risk of diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2010;121:2102–2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khan SQ, Dhillon O, Struck J, et al. C‐terminal pro‐endothelin‐1 offers additional prognostic information in patients after acute myocardial infarction: Leicester Acute Myocardial Infarction Peptide (LAMP) Study. Am Heart J. 2007;154:736–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Neuhold S, Huelsmann M, Strunk G, et al. Comparison of copeptin, B‐type natriuretic peptide, and amino‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide in patients with chronic heart failure: prediction of death at different stages of the disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sahn DJ, DeMaria A, Kisslo J et al. Recommendations regarding quantification in M‐mode echocardiography: results of a survey of echocardiographic measurements. Circulation. 1978;58:1072–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morgenthaler NG, Struck J, Alonso C, et al. Assay for the measurement of copeptin, a stable peptide derived from the precursor of vasopressin. Clin Chem. 2006;52:112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morgenthaler NG. Copeptin: a biomarker of cardiovascular and renal function. Congest Heart Fail. 2010;16(suppl 1):S37‐S44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fan YH, Zhao LY, Zheng QS, et al. Arginine vasopressin increases iNOS‐NO system activity in cardiac fibroblasts through NF‐κB activation and its relation with myocardial fibrosis. Life Sci. 2007;81:327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lorell BH, Carabello BA. Left ventricular hypertrophy: pathogenesis, detection, and prognosis. Circulation. 2000;102:470–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Galderisi M. Diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure: diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic aspects. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2005;3:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burlew BS, Weber KT. Cardiac fibrosis as a cause of diastolic dysfunction. Herz. 2002;27:92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geske JB, McKie PM, Ommen SR, et al. B‐type natriuretic peptide and survival in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2456–2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kubo T, Kitaoka H, Okawa M, et al. Serum cardiac troponin I is related to increased left ventricular wall thickness, left ventricular dysfunction, and male gender in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:E1–E7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maron BJ, Tholakanahalli VN, Zenovich AG, et al. Usefulness of B‐type natriuretic peptide assay in the assessment of symptomatic state in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2004;109:984–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nishigaki K, Tomita M, Kagawa K, et al. Marked expression of plasma brain natriuretic peptide is a special feature of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:1234–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hasegawa K, Fujiwara H, Doyama K, et al. Ventricular expression of brain natriuretic peptide in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1993;88:372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Varnava AM, Elliott PM, Baboonian C, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: histopathological features of sudden death in cardiac troponin T disease. Circulation. 2001;104:1380–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kubo T, Kitaoka H, Okawa M, et al. Combined measurements of cardiac troponin I and brain natriuretic peptide are useful for predicting adverse outcomes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2011;75:919–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Katan M, Fluri F, Morgenthaler NG, et al. Copeptin: a novel, independent prognostic marker in patients with ischemic stroke [published correction appears in Ann Neurol. 2010;67:277–281]. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meissner J, Nef H, Darga J, et al. Endogenous stress response in Tako‐Tsubo cardiomyopathy and acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41:964–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lipinski MJ, Escárcega RO, D'Ascenzo F, et al. A systematic review and collaborative meta‐analysis to determine the incremental value of copeptin for rapid rule‐out of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:1581–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Keller T, Tzikas S, Zeller T, et al. Copeptin improves early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2096–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Stelzig C, et al. Incremental value of copeptin for rapid rule out of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liebetrau C, Nef H, Szardien S, et al. Release kinetics of copeptin in patients undergoing transcoronary ablation of septal hypertrophy. Clin Chem. 2013;59:566–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Elmas E, Doesch C, Fluechter S, et al. Midregional pro‐atrial natriuretic peptide: a novel marker of myocardial fibrosis in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;27:547–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]