Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) pose a major burden in Africa, but data on temporal trends in disease burden are lacking. We assessed trends in CVD admissions and outcomes in central Ghana using a retrospective analysis of data from January 2004 to December 2015 among patients admitted to the medical wards of a tertiary medical center in Kumasi, Ghana. Rates of admissions and mortality were expressed as CVD admissions and deaths divided by the total number of medical admissions and deaths, respectively. Case fatality rates per specific cardiac disease diagnosis were also computed. Over the period, there were 4226 CVD admissions, with a male‐to‐female ratio of 1.1 to 1. There was a progressive increase in percentage of CVD admissions from 4.6% to 8.2%, representing an 78% increase, between 2004 and 2014. Of the 2170 CVD cases whose data were available, the top 3 causes of CVD admissions were heart failure (HF; 88.3%), ischemic heart disease (IHD; 7.2%), and dysrhythmias (1.9%). Of all HF admissions, 52% were associated with hypertension. IHD prevalence rose by 250% between 2005 and 2015. There were 976 deaths (23%), with an increase in percentage of hospital deaths that were cardiovascular in nature from 3.6% to 7.3% between 2004 and 2014, representing a 102% increase. Cardiac disease admissions and mortality have increased progressively over the past decade, with HF as the most common cause of admission. Once rare, IHD is emerging as a significant contributor to the CVD burden in sub‐Saharan Africa.

Keywords: Cardiac Disease, CVDs, Ghana, Heart Failure, Hypertension, IHD, SSA

1. INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) globally accounts for the number‐one cause of death, with more people dying from CVD than from any other cause. More than three‐quarters of such deaths occur in low and middle‐income countries (LMICs).1 Sub‐Saharan Africa (SSA) is already saddled with the double burden of disease; and even as infectious disease currently outweighs noncommunicable diseases, the latter is projected to outstrip the former by 2035.2 On a continent already grappling with significant resource constraints, this could have a telling impact on healthcare delivery.

CVD, as previously reported, constitutes about one‐tenth of all medical admissions in Africa, with heart failure (HF) accounting for the majority of those admissions.3, 4 Emerging evidence suggests a rising proportion of CVD admissions with a corresponding increase in CVD mortality.5 In one study, as much as a 5‐fold increase in the proportion of hospital admissions due to CVD was observed between 1950 and 2010 in Africa.6

There is considerable variation in the spectrum of CVD across different jurisdictions of society. As most high‐income countries battle ischemic heart diseases (IHD), among others, LMICs largely have had to contend with the debilitating sequelae of poorly controlled hypertension (HTN), such as stroke and HF, on the cardiovascular landscape.7, 8

In a setting where there is a lack of reliable community‐based studies to provide adequate data on the specific causes and the burden of CVDs, a hospital‐based study could serve as a good barometer to gauge the health status of the people the hospital seeks to serve by providing relevant information on the changing pattern of diseases affecting the community to help prioritize resources and disease‐specific interventions.

Therefore, the main aim of this study was to assess the current trends in cardiac disease admissions and determinants of outcomes over a 12‐year period in a teaching hospital in Ghana.

2. METHODS

This is a retrospective study carried out from January 2004 to December 2015 on patients who were admitted to the medical wards of the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH), a leading tertiary referral institution in Ghana serving an estimated population of 10 million from 6 out of the 10 administrative regions of Ghana. A review of hospital admissions and deaths from 2004 to 2015 was performed at the hospital registry. Cardiac disease admissions were obtained from tally sheets and the relevant available data were extracted.

All patients who were admitted to the medical wards during the study period and whose records were documented in the admission and discharge registers were included. The patient information in the registers included dates of admission and discharge (or death, referral/transfer, or left against medical advice); name, address, age, and sex; initial diagnosis (presenting or admission diagnosis); final diagnosis; and duration of hospital stay. Outcome variables such as discharge transfer to other wards, referral to other hospitals, death, and duration of hospital stay were noted. In this study, CVD was defined as disease that affects the heart and blood vessels, and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10)9 was used to sort out the final diagnoses in the register to group them into diseases.

The Committee on Human Research Publication and Ethics (CHRPE) of the School of Medical Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, and KATH Kumasi approved this study. Patient records and information were anonymized and de‐identified prior to analysis.

2.1. Statistical analysis

Means and medians were compared using either the Student t test or Mann–Whitney U test for paired comparisons and ANOVA or the Kruskal‐Wallis test for >2 group comparisons, depending on whether continuous variables were parametric or nonparametric. Rates of admissions and mortality were expressed as CVD admissions and deaths divided by the total number of medical admissions and deaths. Yearly crude fatality rates from cardiac diseases were calculated by dividing the number of CVD‐related deaths by the number of CVD admissions. A 2‐sided P value of <0.05 was considered significant in all statistical analyses. Age and sex differences between various cardiac diseases were also assessed.

3. RESULTS

3.1. CVD admissions and death rates

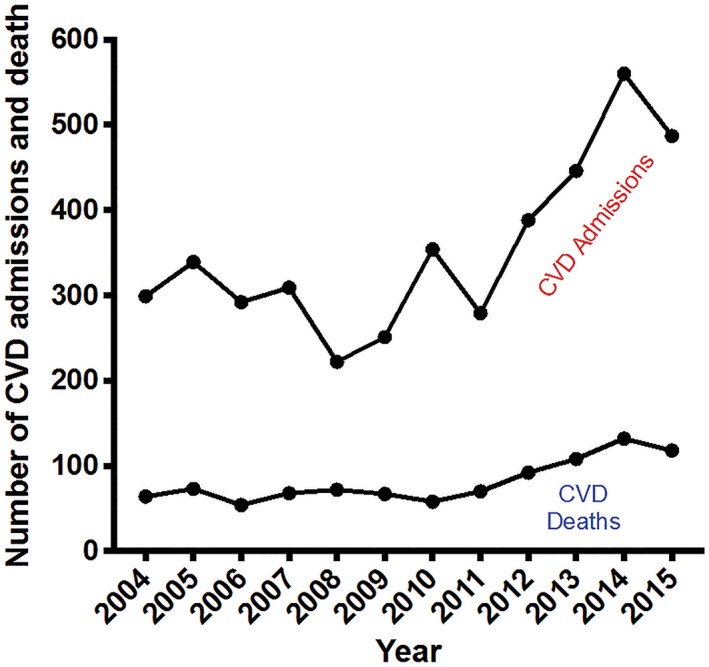

There was a trend toward a progressive increase in the number of CVD admissions over the period under review (Figure 1), as well as the number of CVD deaths (P trend < 0.001 for CVD admissions and death). Generally, there was a gradual increase between 2004 and 2010, followed by a steep rise in CVD admissions between 2011 and 2014. For the same period of sudden rise in CVD admissions, there was also a rise in CVD deaths, followed by a slight dip in the numbers in 2015.

Figure 1.

CVD admissions and deaths at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital between 2004 and 2015. P trend < 0.001 for CVD admissions; P trend < 0.001 for CVD deaths. Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease

Table 1 depicts the progressive increase in CVD admissions, with almost a doubling of admissions over the decade of 2004 to 2014; this represents an 87% increase in the number of CVD admissions over the period. Similarly, there was an increase in the percentage of medical admissions due to cardiac diseases, from 4.6% in 2004 to 8.2% in 2014, representing a 78% increase over the decade. The number of CVD deaths more than doubled, from 64 in 2004 to 132 in 2014, corresponding to an increase in the rate of CVD mortality from 3.6% to 7.3% in same period, an increase of 102%. Although the absolute numbers of CVD admissions and deaths increased over the period, the CVD case fatality rate for most years ranged between 21% and 26%, with the lowest fatality rate at 16.4% in 2010 and the highest at 32.4% in 2008.

Table 1.

CVD admission and mortality rates at KATH between 2004 and 2015

| Year | Medical Admissions, N | CVD Admissionsa, n (%) | Medical Deaths, N | CVD Deathsb, n (%) | CVD Case Fatality Rate, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 6437 | 299 (4.6) | 1795 | 64 (3.6) | 21.4 |

| 2005 | 6679 | 339 (5.1) | 1908 | 73 (4.1) | 21.5 |

| 2006 | 6275 | 292 (4.7) | 1854 | 54 (3.0) | 18.5 |

| 2007 | 7124 | 309 (4.3) | 1934 | 68 (3.8) | 22.0 |

| 2008 | 7286 | 222 (3.0) | 1978 | 72 (4.0) | 32.4 |

| 2009 | 7102 | 251 (3.5) | 1865 | 67 (3.7) | 26.7 |

| 2010 | 7306 | 354 (4.8) | 1907 | 58 (3.2) | 16.4 |

| 2011 | 7266 | 279 (3.8) | 1729 | 70 (3.9) | 25.1 |

| 2012 | 7279 | 388 (5.3) | 1722 | 92 (5.1) | 23.7 |

| 2013 | 6947 | 446 (6.4) | 1543 | 108 (6.0) | 24.2 |

| 2014 | 6861 | 560 (8.2) | 1527 | 132 (7.3) | 23.6 |

| 2015 | 6338 | 487 (7.7) | 1453 | 118 (6.6) | 24.2 |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; KATH, Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital.

P trend < 0.001 for CVD admissions.

P trend < 0.001 for CVD deaths.

3.2. Age and sex distribution of cardiac diseases

The majority of patients admitted over the study period (82%) were age > 40 years. Disease conditions such as pericardial diseases, infective endocarditis, and congenital heart diseases were significantly present in younger patients between the ages of 12 and 40 years (see Supporting Information, Table 1, in the online version of this article). Although more males (1160) than females (1010) were studied, with a male‐to‐female ratio of 1.1 to 1, 91.3% of all females admitted with cardiac diseases had HF, as opposed to 85.7% of all males admitted with cardiac diseases. Of the 2170 patients who had complete data for analysis, 88.3% were admitted with HF as the main diagnosis, followed by IHD at 7.2%, with a male preponderance of almost 10% (Table 2). The mean age of male patients who presented with cor pulmonale was significantly higher than that of the female counterparts. However, there was no difference in the mean ages between males and females for the other cardiac diseases studied.

Table 2.

Demographics and baseline comorbidities for cardiac diseases

| Diagnosis | Admissions, N | % of CVD | Males, n | Females, n | P Value | Male Proportions | Female Proportions | Age, ya | Male Age, ya | Female Age, ya | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | 1916 | 88.3 | 994 | 922 | <0.0001 | 85.7 | 91.3 | 59 ± 18.45 | 59.4 ± 17.32 | 58.6 ± 19.6 | 0.343 |

| Causes of HF | |||||||||||

| HTN | 1005 | 52.3 | 523 | 482 | 0.891 | 52.5 | 51.9 | 61.2 ± 16.92 | 60.9 ± 15.66 | 61.5 ± 18.19 | 0.575 |

| DM | 169 | 10.3 | 91 | 77 | 0.223 | 10.7 | 9.8 | 65.1 ± 11.95 | 65.4 ± 10.89 | 64.6 ± 13.18 | 0.667 |

| KD (with or without anemia) | 80 | 4.9 | 35 | 45 | 0.138 | 4.1 | 5.7 | 44 ± 19.03 | 44.1 ± 17.90 | 43.9 ± 20.06 | 0.963 |

| CMP | 380 | 19.8 | 185 | 195 | 0.169 | 18.6 | 21 | 54.4 ± 19.08 | 56.9 ± 17.15 | 52.1 ± 20.6 | 0.014 |

| VHD | 147 | 7.6 | 76 | 71 | >0.999 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 47.7 ± 21.17 | 45.8 ± 21.1 | 49.7 ± 21.36 | 0.268 |

| IHD | 77 | 4.0 | 48 | 29 | 0.063 | 4.8 | 3.1 | 68.7 ± 13.32 | 68.2 ± 13.11 | 69.5 ± 13.85 | 0.681 |

| Dysrhythmias | 26 | 1.4 | 16 | 10 | 0.429 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 70.6 ± 9.50 | 70.1 ± 9.50 | 70.7 ± 21.33 | 0.922 |

| CHD | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0 | >0.999 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 18 | 18 | NA | — |

| Others/unknown | 280 | 14.6 | 145 | 135 | >0.999 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 59.1 ± 18.87 | 60.0 ± 18.66 | 59.1 ± 18.87 | 0.688 |

| IHD | 157 | 7.2 | 113 | 44 | <0.0001 | 9.7 | 4.4 | 61 ± 15.73 | 61.1 ± 15.97 | 60.7 ± 15.29 | 0.887 |

| Pericardial disease | 17 | 0.8 | 13 | 4 | 0.08 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 43 ± 18.12 | 39.4 ± 15.52 | 56 ± 22.49 | 0.111 |

| Dysrhythmias | 41 | 1.9 | 17 | 24 | 0.154 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 63 ± 19.67 | 59.2 ± 17.71 | 65.8 ± 20.88 | 0.295 |

| Cor pulmonale | 15 | 0.7 | 12 | 3 | 0.065 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 62 ± 20.63 | 67.9 ± 18.92 | 39.7 ± 7.23 | 0.028 |

| CHD | 9 | 0.4 | 3 | 6 | 0.319 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 23 ± 13.37) | 28.7 ± 10.69 | 19.7 ± 14.42 | 0.376 |

| IE | 7 | 0.3 | 4 | 3 | >0.999 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 37 ± 19.21 | 33.5 ± 14.15 | 41.3 ± 27.47 | 0.64 |

| VTE | 8 | 0.4 | 4 | 4 | >0.999 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 66 ± 10.13 | 68.8 ± 10.5 | 63.5 ± 10.54 | 0.503 |

| Total | 2170 | — | 1160 | 1010 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Abbreviations: CHD, congenital heart disease; CMP, cardiomyopathy; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HF, heart failure; HTN, hypertension; IE, infective endocarditis; IHD, ischemic heart disease; KD, kidney dysfunction; NA, not applicable; SD, standard deviation; VTE, venous thromboembolism; VHD, valvular heart disease.

Data presented as mean ± SD.

3.3. Cardiac disease trends

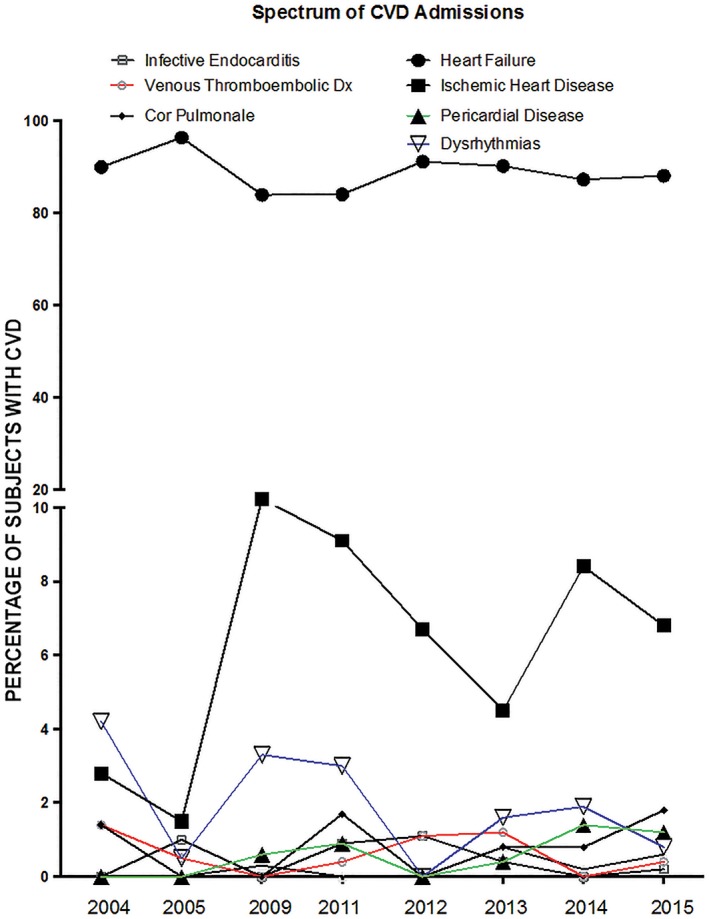

Figure 2 shows the trends in CVD admissions over the study period, with HF consistently the top cause of CVD admissions, constituting ≥80% of all CVD admissions. This is remotely followed by IHD as the second‐highest cause. There was a sharp rise in cases of IHD in 2009 and then in 2014, with the trend appearing to be sustained, albeit at a lower level, in subsequent years.

Figure 2.

Trends in CVD types between 2004 and 2015. P trend for CVD types: heart failure, 0.126; ischemic heart disease, 0.185; pericardial disease, 0.062; dysrhythmias, 0.198; cor pulmonale, 0.049; congenital heart disease, 0.605; infective endocarditis, 0.229; and venous thromboembolic disease, 0.193. Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease

3.4. HF causes and demography

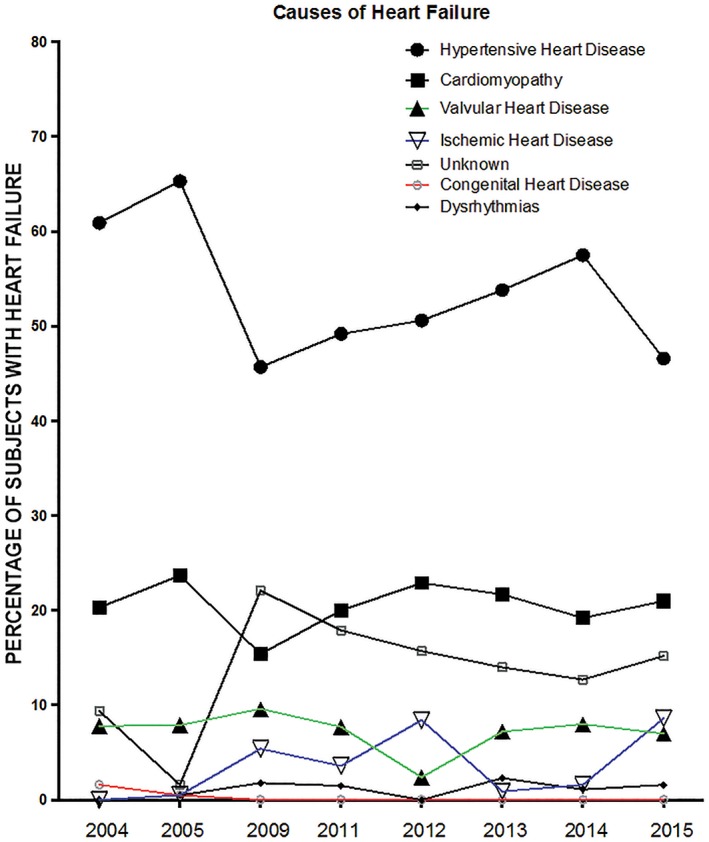

Table 2 and Figure 3 show HTN as the most common cause of HF admissions, accounting for 46% in 2009 and 65% in 2005 and an overall 52.3% of all HF admissions. Cardiomyopathy and valvular heart disease remotely follow HTN as the second‐highest (20%) and third‐highest (8%) causes of HF admissions.

Figure 3.

Trends in causes of heart failure between 2004 and 2015. P trend for hypertensive heart disease, 0.015; cardiomyopathy, 0.936; valvular heart disease, 0.480; ischemic heart disease, 0.003; dysrhythmias, 0.315; congenital heart disease, 0.002; and unknown, 0.026

There is a higher proportion of females (21% vs 18.6%) presenting with cardiomyopathy as the cause of HF, with a mean age significantly lower than that of their male counterparts (52.1 vs 56.9 years, P = 0.014; Table 2). No significant age or sex difference was observed in the other causes of HF.

3.5. Cardiac disease case fatality

Although it remotely trailed HF as the second‐highest cause of CVD admissions, IHD appears to have a higher case fatality rate than HF (see Supporting Information, Figure 1, in the online version of this article). The smallest case fatality rate was seen among patients with congenital heart disease.

4. DISCUSSION

This work, to our knowledge, is the largest hospital‐based study examining the trajectory of CVD admissions and deaths in West Africa. It has been previously shown that CVD accounts for approximately 7% to 10% of all adult medical admissions within Africa10 and that the burden of CVD admissions and deaths has been on the increase among Ghanaians over the last decade, affecting predominantly the middle‐aged population.11 This is reflected by an increase in both the absolute numbers of CVD admissions and mortality recorded over the period in our current study. These findings are comparable to similar hospital‐based studies conducted in SSA.5, 6

The upsurge in the burden of cardiac diseases is largely attributable to the phenomenon of globalization, resulting in increased interconnectedness and interdependence of peoples, cultures, and countries.12 The attainment of LMIC status by Ghana in 2010, with its attendant modest improvements in socioeconomic indicators, has provided the necessary platform to drive this phenomenon largely plaguing LMICs. Indeed, Ghana has enjoyed a steadily increasing economic growth of >7% per year, on average, since 2005, with a double‐digit growth rate in 2011 following income from offshore oil reserves discovered in 2007. Income growth has brought about rapid reduction in monetary poverty from 51.7% of the population to 24.2% in 2013, thus achieving Millennium Development Goal 1.13 Life expectancy in SSA has also surged, up by between 20% and 42% since 2000.14 SSA, which is already home to about 80% of CVD‐related mortality and about 87% of CVD‐related disability, has remained as about the only part of the world where CVD‐related deaths have increased over the period between 1990 and 2013 as a result of population growth, epidemiological transition, and aging populations.15 Our trend analysis in the middle belt of Ghana has corroborated this finding and has shown an increment of 87% in number of CVD admissions and 102% increment in CVD mortality between 2004 and 2014. This has important clinical and public health implications in our quest to stem the burgeoning tide of CVD as developing countries already saddled with an enormous burden of infectious diseases.

Overall, we observed a nearly equal distribution of CVD admissions by sex; however, HF, the most common cause of CVD admissions, was more preponderant among middle‐aged females. This might be due to the increased CVD risk among postmenopausal women. However, 2 previous studies in Accra and Kumasi, both in Ghana, showed a similar sex distribution.16, 17 IHD follows as the second most common cause of CVD admissions, constituting 7.2%, with a generally observed stepwise increase in trend over the study period and a case fatality rate of about 17%. The sharp rise in IHD cases from 2005 is possibly due to the heightened awareness created in the diagnosis and management of cardiac cases at the study site, which now has at least 5 cardiologists. About 10% of all males over the period under review presented with IHD. It has been suggested that the surge in IHD among Africans could be due the rise in CVD risk factors, particularly HTN,18 and the adverse sequel of behavioral and lifestyle changes associated with urbanization and epidemiologic transition.19 These modifiable risk factors contribute to a 90% population‐attributable risk for acute myocardial infarction in the INTERHEART African study.20 Thus, there is a window of opportunity for the prevention of this emerging threat of IHD in SSA.

The spectrum of cardiac diseases presented in this study aptly mirrors the dramatic changes in health outcomes that have accompanied economic development, specialized labor, and systematic industrialization in most LMICs, resulting in the increasing prevalence of CVDs. In the present study, HF remains the leading cause of CVD admissions, with HTN as the major cause, contributing 52.3%, in keeping with previous reports in the same hospital17, 21 and elsewhere within the country.16 Similar findings were documented in the largest African acute HF registry, The Sub‐Saharan Africa Survey of Heart Failure (THESUS‐HF) trial, in which HTN, cardiomyopathies, and valvular heart diseases accounted for 76% of HF cases, compared with 79% in the current study.22 One of the striking features of this study, which was also observed in THESUS‐HF, is the relatively young age of affected patients (mean age, 59 years), in sharp contrast to a mean age of 72 years in high‐income countries.23 HF thus appears to rob Africa of its productive population and, inevitably, its economic potential. This finding could be due to the significant contribution of valvular heart diseases and cardiomyopathy, as these tended to occur at earlier ages compared with other causes of HF. In Africa, HF has emerged as a dominant form of CVD, with the causes largely nonischemic in origin and accounting for significant morbidity and premature mortality, a looming public health crisis indeed. Hypertensive heart disease complications occur more frequently in Africans than in other populations.8

IHD, an entity that has long been regarded as extremely rare in SSA,24 is slowly but steadily emerging as an important disease entity. This study has demonstrated that IHD is the second most common cause of CVD admissions (7.2%) and the fourth most common cause of HF (4%), similar to previous work in SSA reported by Bloomfield et al.24 Indeed, it is possible that the burden and trend of IHD may have been underestimated owing to limited diagnostic tools in our setting. However, the signal is quite clear that as Africa makes socioeconomic gains and adopts adverse lifestyle and dietary changes, the burden of IHD will undoubtedly grow, putting immeasurable strain on the limited capacity to better manage the dire consequences as countries continue to struggle with the double burden of diseases. Not surprisingly, the case fatality rate of IHD in this cohort supersedes that of HF. This serves as a wake‐up call for the institution of massive, intensive, and pragmatic public health interventions to curb this menace. Needless to say, the practice of cardiology in resource‐poor settings is constrained by limited diagnostic support juxtaposed with a heavy CVD burden. Going forward, as more cardiologists become trained and the subspecialty develops with research at its center, a clearer picture of the etiology and spectrum of CVDs and determinants of outcomes will be invaluable in shaping policy at both individual and population levels. The key drivers of CVDs are largely preventable globally, and with a concerted multilevel, multidimensional approach, the current debilitating CVD trajectory can be reversed, or at least significantly curtailed.

5. CONCLUSION

We show in this study that the absolute and proportionate numbers of CVD admissions and mortality have increased steadily over the past decade in central Ghana. HF, a large and global public health concern, is the preponderant cause of CVD admissions, with HTN as the most common cause of HF in this cohort. IHD is significantly emerging both as a cause of CVD admissions and also as a cause of HF. Targeted, sustained, systematic, and effective interventions, focusing on both the traditional nonischemic and the emerging ischemic CVD risk factors within the subregion, are required to stem the scourge of these largely preventable cardiac diseases.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary Figure 1. Case fatality rate per CVD

Supplementary Table 1. Age distribution of CVDs

Appiah LT, Sarfo FS, Agyemang C, et al. Current trends in admissions and outcomes of cardiac diseases in Ghana. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:783–788. 10.1002/clc.22753

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . Fact sheet on cardiovascular diseases. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/. Updated May 2017. Accessed December 27, 2016.

- 2. Nyirenda MJ. Non‐communicable diseases in sub‐Saharan Africa: understanding the drivers of the epidemic to inform intervention strategies. Int Health. 2016;8:157–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oyoo GO, Ogola EN. Clinical and sociodemographic aspects of congestive heart failure patients at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J. 1999;76:23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Antony KK. Pattern of cardiac failure in Northern Savanna Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med. 1980;32:118–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ajayi EA, Ajayi OA, Adeoti OA, et al. A five‐year review of the pattern and outcome of cardiovascular diseases admissions at the Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria. Nig J Cardiol. 2014;1:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Etyang AO, Scott JA. Medical causes of admissions to hospital among adults in Africa: a systematic review. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1269–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ntusi NB, Mayosi BM. Epidemiology of heart failure in sub‐Saharan Africa. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2009;7:169–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Quest Diagnostics . ICD‐9‐CM to ICD‐10 Common Codes for Cardiovascular Disease https://www.questdiagnostics.com/dms/Documents/Other/PDF_MI4632_ICD_9‐10_Codes_for_Cardio_38365_062915.pdf. Accessed December 28, 2016.

- 10. Mocumbi AO. Lack of focus on cardiovascular disease in sub‐Saharan Africa. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2012;2:74–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mbewu A, Mbanya JC. Cardiovascular disease In: Jamison DT, Feachem RG, Makgoba MW, et al, eds. Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality in Sub‐Saharan Africa. 2nd ed Washington, DC: World Bank; 2006. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2294/. [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization . Health topics: Globalization. http://www.who.int/topics/globalization/en/. Updated 2017. Accessed May 7, 2017.

- 13. Cooke E, Hague S, McKay A. The Ghana Poverty and Inequality Report, 2016. https://www.unicef.org/ghana/Ghana_Poverty_and_Inequality_Analysis_FINAL_Match_2016(1).pdf. Accessed May 7, 2017.

- 14. Johnson S. Africa's life expectancy jumps dramatically. Financial Times. April 26, 2016. https://www.ft.com/content/38c2ad3e‐0874‐11e6‐b6d3‐746f8e9cdd33. Accessed May 6, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roth GA, Forouzanfar MH, Moran AE, et al. Demographic and epidemiologic drivers of global cardiovascular mortality. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1333–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amoah AG, Kallen C. Aetiology of heart failure as seen from a National Cardiac Referral Centre in Africa. Cardiology. 2000;93:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Owusu IK. Causes of heart failure as seen in Kumasi, Ghana. Internet J Third World Med. 2006. https://print.ispub.com/api/0/ispub‐article/9012. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Onen CL. Epidemiology of ischaemic heart disease in sub‐Saharan Africa. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2013;24:34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mensah GA. Ischaemic heart disease in Africa. Heart. 2008;94:836–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Steyn K, Sliwa K, Hawken S, et al; INTERHEART Investigators in Africa . Risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in Africa: the INTERHEART Africa Study. Circulation. 2005;112:3554–3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Owusu IK, Adu‐Boakye Y. Prevalence and aetiology of heart failure in patients seen at a teaching hospital in Ghana. J Cardiovasc Dis Diagn. 2013;1:131 https://www.esciencecentral.org/journals/prevalence‐and‐aetiology‐of‐heart‐failure‐in‐patients‐seen‐at‐a‐teaching‐hospital‐in‐ghana‐2329‐9517.1000131.php?aid=20541. Accessed March 24, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Damasceno A, Mayosi BM, Sani M, et al. The causes, treatment, and outcome of acute heart failure in 1006 Africans from 9 countries. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1386–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adams KF Jr, Fonarow GC, Emerman CL, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for heart failure in the United States: rationale, design, and preliminary observations from the first 100 000 cases in the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE). Am Heart J. 2005;149:209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bloomfield GS, Barasa FA, Doll JA, et al. Heart failure in Sub‐Saharan Africa. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2013;9:157–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Case fatality rate per CVD

Supplementary Table 1. Age distribution of CVDs