Abstract

Background

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) downregulates low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors, thereby leading to a rise in circulating LDL cholesterol (LDL‐C). RG7652 is a fully human monoclonal antibody against PCSK9. This placebo‐controlled, phase 1 ascending‐dose study in healthy subjects evaluated the safety of RG7652 and its efficacy as a potential LDL‐C–lowering drug.

Hypothesis

Anti‐PCSK9 antibody therapy safely and effectively reduces LDL‐C.

Methods

Subjects (N = 80) were randomized into 10 cohorts. Six sequential single‐dose cohorts received 10, 40, 150, 300, 600, or 800 mg of RG7652 via subcutaneous injection. Four multiple‐dose cohorts received 40 or 150 mg of RG7652 once weekly for 4 weeks, either with or without statin therapy (atorvastatin).

Results

Adverse events (AEs) were generally mild; the most common AEs were temporary injection‐site reactions. No serious AEs, severe AEs, AEs leading to study‐drug discontinuation, or dose‐limiting toxicities were reported. RG7652 monotherapy reduced mean LDL‐C levels by up to 64% and as much as 100 mg/dL at week 2; the effect magnitude and duration increased with dose (≥57 days following a single RG7652 dose ≥300 mg). Exploratory analyses showed reduced oxidized LDL, lipoprotein(a), and lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 with RG7652. Antidrug antibody against RG7652 tested positive in 2 of 60 (3.3%) RG7652‐treated and in 4 of 20 (20.0%) placebo‐treated subjects. Simultaneous atorvastatin administration did not appear to impact the pharmacokinetic profile or lipid‐lowering effects of RG7652.

Conclusions

Overall, RG7652 elicited substantial and sustained dose‐related LDL‐C reductions with an acceptable safety profile and minimal immunogenicity.

Keywords: Clinical trial, cholesterol, antibody drug, phase 1, RG7652, PCSK9 inhibitors, LDL receptor

1. INTRODUCTION

Elevated low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) levels are associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD).1 The LDL receptor (LDLR) is the primary pathway for the removal of cholesterol from circulation, whereas proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) binds to LDLRs and targets these receptors for degradation.2 Consistent with a role for PCSK9 in reducing cholesterol clearance by promoting LDLR degradation, gain‐of‐function genetic mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal‐dominant hypercholesterolemia, including premature CHD, whereas loss‐of‐function mutations are associated with lower LDL‐C levels and decreased risk for coronary events.3, 4

RG7652 (MPSK3169A) is a fully human immunoglobulin 1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody directed against PCSK9 that blocks the interaction between PCSK9 and LDLR. The potential importance of a fully human antibody drug with respect to immune response has recently been highlighted by others.5 The lead antibody was selected based on its unique solubility characteristics that enabled formulation at high concentration of up to 200 mg/mL. Based on favorable preclinical, safety, and efficacy data,6, 7 a first‐in‐human study was initiated and reported here to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacodynamics, and LDL‐C–lowering effects of RG7652 in otherwise‐healthy individuals with elevated LDL‐C.

2. METHODS

2.1. Subjects

Eligible subjects were men and women age 18 to 65 years with fasting serum LDL‐C levels of 130 to 220 mg/dL, body mass index (BMI) of 18.0 to 37.0 kg/m2, and weight ≥45 kg. Key exclusion criteria included CHD or CHD risk equivalents, familial hypercholesterolemia or secondary hyperlipidemia, and statin intolerance or statin therapy within 14 days of screening.

2.2. Study design and treatments

This was a phase 1, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, ascending‐dose study of RG7652. The primary objective was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of single and multiple doses of RG7652 administered via subcutaneous injection. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines, consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards. All subjects provided written informed consent.

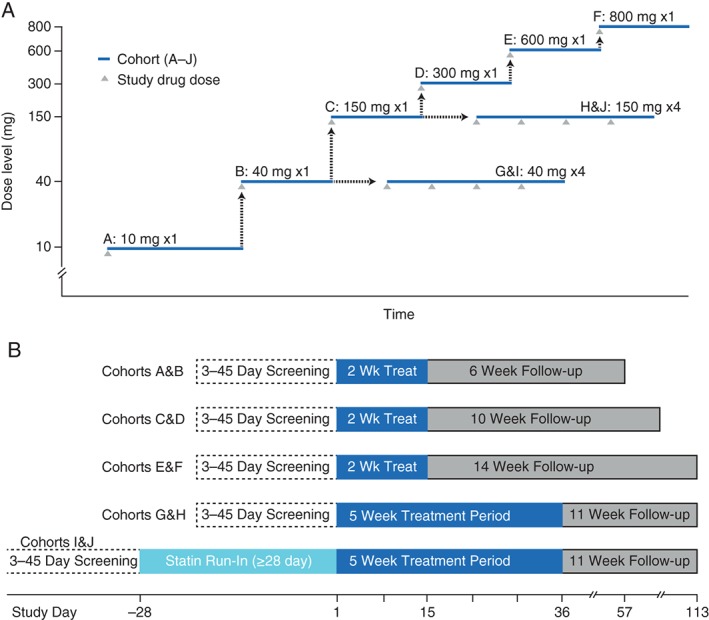

Subjects within 6 sequential single‐dose cohorts (A–F) and 4 multiple‐dose cohorts (G–J) were randomized to receive RG7652 or placebo in a 3:1 ratio (6 active treatment, 2 placebo per cohort; Figure 1). (See also Supporting Information, Methods, in the online version of this article).

Figure 1.

Design of phase 1 study of RG7652 in subjects with elevated LDL‐C. (A) Dose‐escalation scheme. Black arrows represent safety assessments prior to initiating dose administration in the next cohort. (B) Subject timelines by cohort. Treatment time included 2 weeks following last dose. Abbreviations: LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol.

2.3. Safety and immunogenicity assessments

Subjects were monitored for 8 to 16 weeks following the initiation of RG7652 treatment. Safety assessments consisted of the incidence, nature, severity (mild, moderate, or severe), and seriousness of adverse events (AEs), as well as dose‐limiting toxicities, changes in vital signs, electrocardiograms, and clinical laboratory results, including the incidence of antidrug antibody (ADA) against RG7652. Serum ADAs were tested in blood samples collected pre‐dose during the treatment period by a validated enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay8; any subject confirmed to have an ADA‐positive sample after receiving the study drug was considered positive for ADAs, regardless of baseline status.

2.4. PCSK9, lipid panel, and biomarker analyses

Blood samples were analyzed for biomarkers and lipid profiles as described (see Supporting Information, Methods, in the online version of this article).

2.5. Statistical analyses

The safety population consisted of all subjects who received ≥1 dose of study drug and had ≥1 post‐dose safety assessment (see Supporting Information, Methods, in the online version of this article).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Phase 1 study population

A total of 80 subjects (mean age, 45 years; 48% male; body mass index [BMI] 19.8–36.2 kg/m2) eligible to enter the study were randomized and received study treatment within 6 single‐dose (A–F) and 4 multiple‐dose (G–J) cohorts (Figure 1). One subject each from cohorts J and E chose to withdraw (for reasons other than AEs), at days 43 and 82, respectively; the remaining 78 subjects completed the study. Baseline characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline subject characteristics

| Overall | Overall | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Dose Cohorts | Cohort A, 10 mg, n = 6 | Cohort B, 40 mg, n = 6 | Cohort C, 150 mg, n = 6 | Cohort E, 600 mg, n = 6 | Cohort F, 800 mg, n = 6 | Placebo, N = 12 | RG7652, N = 36 |

| Age, y, mean (range) | 47 (35–56) | 44 (32–58) | 51 (38–63) | 49 (19–64) | 35 (24–44) | 49 (27–62) | 44 (19–64) |

| Weight, kg, mean | 88.2 | 89.1 | 82.2 | 92.5 | 98.2 | 77.8 | 86.0 |

| Height, cm, mean | 176.8 | 168.0 | 170.1 | 168.0 | 180.0 | 167.7 | 170.9 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean | 28.0 | 31.2 | 28.1 | 32.6 | 30.4 | 27.6 | 29.2 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 5 (83.3) | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (83.3) | 3 (25.0) | 21 (58.3) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| White | 6 (100.0) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 7 (58.3) | 21 (58.3) |

| Black or African American | 0 (0.0) | 5 (83.3) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (33.3) | 14 (38.9) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (2.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (16.7) | 3 (8.3) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 10 (83.3) | 33 (91.7) |

| Baseline LDL‐C levels, mean (SD) | 175 (24) | 169 (41) | 162 (43) | 163 (26) | 157 (29) | 150 (25) | 163 (30) |

| No Statin | No statin | With Statin | With statin | Overall | Overall | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple dose cohorts | Cohort G, 40 mg, n = 6 | Cohort H, 150 mg, n = 6 | Cohort I, 40 mg, n = 6 | Cohort J, 150 mg, n = 6 | Placebo, N = 8 | RG7652 Alone, N = 12 | RG7652 and Statin, N = 12 |

| Age, y, mean (range) | 43 (22–63) | 40 (20–51) | 44 (33–62) | 48 (34–60) | 49 (39–61) | 41 (20–63) | 46 (33–62) |

| Weight, kg, mean | 81.8 | 76.5 | 76.5 | 81.5 | 82.6 | 79.2 | 79.0 |

| Height, cm, mean | 169.4 | 164.3 | 164.3 | 171.3 | 168.1 | 166.8 | 167.8 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean | 28.5 | 28.4 | 28.5 | 27.6 | 29.0 | 28.4 | 28.0 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (41.7) | 6 (50.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| White | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 5 (83.3) | 4 (66.7) | 4 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | 9 (75.0) |

| Black or African American | 4 (66.7) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (50.0) | 5 (41.7) | 3 (25.0) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 0 (0.0) | 4 (66.7) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (12.5) | 4 (33.3) | 2 (16.7) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 6 (100) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) | 7 (87.5) | 8 (66.7) | 10 (83.3) |

| Baseline LDL‐C, mean (SD)1 | 145 (21) | 129 (42) | 81 (14) | 82 (26) | 151 (15),2 89 (26)3 | 136 (34) | 82 (20) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (Friedewald calculated); PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9; SD, standard deviation.

Mean (SD) LDL‐C at screening (prior to atorvastatin initiation) for cohorts I, J, and placebo was 153 (27), 162 (12), and 171 (22), respectively.

Baseline LDL‐C presented separately for placebo alone.

Baseline LDL‐C presented separately for placebo with background atorvastatin.

RG7652 and atorvastatin were discontinued due to direct LDL‐C levels <25 mg/dL in 1 actively treated subject from cohort I (day 9), 4 actively treated subjects from cohort J (days 12 [2 subjects], 13, and 14), and 1 placebo‐treated subject in cohort J (day 10, LDL‐C <25 mg/dL possibly due to a sample error). These subjects continued in the study and were assessed for the study duration.

3.2. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity

3.2.1. Single dose

A total of 37 AEs were reported with RG7652 in 23 of 36 subjects, and 11 with placebo in 5 of 12 subjects, following single‐dose administration. All AEs were classified by the investigator as mild except for 2 moderate AEs (headache [n = 1] and fractured radius [n = 1]), both of which were considered unrelated to the study drug by the investigator. The most commonly reported AE was local injection‐site reaction (3/20 or 15.0% of placebo subjects; 13/60 or 21.7% of treatment subjects), which most often consisted of mild hemorrhage and/or erythema. AEs occurring in ≥2 subjects are shown in Table 2. No clinically significant AEs were identified in subjects with direct LDL‐C ≤25 mg/dL.

Table 2.

Adverse events occurring in ≥2 subjects

| Adverse Event1, n (%) of Subjects | Placebo, n = 20 | Active Treatment, n = 60 | All Subjects, N = 80 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Injection‐site reactions | 3 (15.0) | 13 (21.7) | 16 (20.0) |

| Headache | 2 (10.0) | 4 (6.7) | 6 (7.5) |

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection | 2 (10.0) | 3 (5.0) | 5 (6.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | — | 2 (3.3) | 2 (2.5) |

| Cough | 1 (5.0) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (2.5) |

| Nasal congestion | 1 (5.0) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (2.5) |

| Sinusitis | — | 2 (3.3) | 2 (2.5) |

| Diarrhea | — | 2 (3.3) | 2 (2.5) |

| Pruritus | — | 2 (3.3) | 2 (2.5) |

| Dizziness | 1 (5.0) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (2.5) |

| Contusion | 1 (5.0) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (2.5) |

All were mild in severity except for 1 moderate headache. None led to study‐drug discontinuation.

No serious AEs, severe AEs, AEs leading to study‐drug discontinuation, or dose‐limiting toxicities were reported. Sporadic out‐of‐range values occurred in several subjects for various laboratory parameters; none were considered to be clinically significant by the investigator and there were no apparent treatment‐related trends, with the exception of lipid‐panel data. The majority of AEs (65.2%) were considered unrelated to the study drug by investigators; for data on AEs by treatment group and relationship to study drug, see Supporting Information, Table 1, in the online version of this article.

3.2.2. Multiple doses

Following multiple‐dose administration of RG7652, a total of 12 AEs, all mild, were reported by 7 of 12 subjects, with the majority occurring in the 150‐mg dose group (7 AEs in 5 subjects). In subjects co‐administered with atorvastatin, 7 mild AEs were reported in each of the 40‐mg and 150‐mg RG7652 treatment groups (14 AEs in 7/12 RG7652 + statin subjects). The placebo group reported 13 AEs in 6 of 8 subjects.

3.3. Clinical evaluations

In the single‐ and multiple‐dose cohorts, no clinically significant changes or findings were noted from nonlipid clinical laboratory evaluations, vital‐sign measurements, physical examinations, or 12‐lead electrocardiograms during this study, including the cardiac risk factors of blood pressure, heart rate, and glucose levels.

3.4. Immunogenicity

ADAs against RG7652 were detected in subjects at baseline prior to administration of RG7652 (n = 1) or placebo (n = 2). After treatment, ADAs were detected in 2 of 60 (3.3%) RG7652‐treated subjects and in 4 of 20 (20.0%) placebo‐treated subjects. ADAs were not detected at any post‐baseline time point in the single RG7652‐treated subject with ADAs detected at baseline. In subjects who were ADA‐positive during the study, the observed AEs were few in number and did not suggest an immunologic reaction or other concerning pattern. The concentrations of RG7652 and the magnitude of the LDL‐C response over time were not qualitatively altered at the time of the ADA‐positive result, nor did they appear to differ from ADA‐negative subjects.

3.5. Pharmacokinetics and total PCSK9

RG7652 serum concentrations increased more than proportionally over the dose range of 10 to 800 mg, indicating faster clearance of RG7652 at lower doses (Figure 2A,B). However, RG7652 serum concentrations were dose‐proportional in the 300‐ to 800‐mg range, suggesting ≥2 clearance mechanisms, with ≥1 saturating at higher doses (see Supporting Information, Table 2, in the online version of this article). Simultaneous atorvastatin administration did not appear to impact the pharmacokinetic profile of RG7652.

Figure 2.

RG7652 pharmacokinetics, plasma PCSK9 concentrations, and LDL‐C levels in single‐dose and multiple‐dose cohorts. Mean (standard deviation) serum RG7652 (MPSK3169A) concentration‐time profiles from (A) single‐dose cohorts and (B) multiple‐dose cohorts. (Note: Subjects no. 1803 [cohort H] and 1904, 1906, 1907, and 1908 [cohort I] discontinued RG7652 and atorva dosing due to reported LDL‐C values <25 mg/dL. As a result, all pharmacokinetic data from these subjects were excluded after day 14 [pre‐dose]). Mean (standard deviation) plasma PCSK9 concentrations of (C) single‐dose and (D) multiple‐dose RG7652 cohorts. Percent change in LDL‐C in (E) single‐dose and (F) multiple‐dose cohorts. *Data from cohort J (150 mg QWx4 + atorva) are presented up to day 10 because multiple subjects were discontinued after day 10 due to LDL‐C values <25 mg/dL. Abbreviations: atorva, atorvastatin 40 mg daily; CI, confidence interval; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9; QW, every week; SD, single dose.

Following RG7652 administration, dose‐related increases in total PCSK9 levels were observed by day 6, with levels gradually returning to baseline between days 85 and 113 (Figure 2C,D). In the highest single‐dose cohort (F; RG7652 800 mg), total PCSK9 was increased 16‐fold from baseline on day 15. There was no significant difference in peak total PCSK9 levels or the absolute change from baseline between the statin‐treated and statin‐naïve subgroups.

3.6. Efficacy endpoints

LDL‐C levels decreased from baseline following RG7652 administration in all single‐ and multiple‐dose cohorts (Figure 2E,F; see also Supporting Information, Figure 1 and Table 3, in the online version of this article). Individual subject data showed decreases in LDL‐C levels from baseline for all subjects treated with RG7652, with substantial variability in the magnitude of effect across individuals (see Supporting Information, Figure 2, in the online version of this article). The magnitude of the decrease in LDL‐C levels increased with RG7652 doses between 10 mg and 300 mg in the single‐dose cohorts, whereas the effect duration continued to increase with dose up to the highest dose tested (800 mg). The 3 highest single doses of RG7652 (300, 600, and 800 mg) decreased mean LDL‐C levels from baseline by 84 to 100 mg/dL (53%–64%) at day 15 compared with 11 mg/dL (6.6%) with placebo (see Supporting Information, Table 3, in the online version of this article). Individual subject data showed that the minimum individual response to RG7652 administered at doses of ≥300 mg was a reduction of LDL‐C by 56 mg/dL (34%) at day 15. Mean LDL‐C values were ≥2 SDs below baseline through day 57 for the 3 highest single doses and remained below baseline and below placebo values on day 113 in the 600‐mg and 800‐mg RG7652 dose cohorts. The time of maximal LDL‐C decrease was observed on days 8, 15, 22, 15, 22, and 29 for the 10‐, 40‐, 150‐, 300‐, 600‐, and 800‐mg dose cohorts, respectively. The LDL‐C–lowering effects of RG7652 in this small study were consistent across key subgroups, including male and female subjects, African Americans, subjects of different ages, and those with low and high BMI.

Similar to the effects observed for calculated LDL‐C, dose‐dependent decreases from baseline were also observed for directly measured LDL‐C, non–high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (non–HDL‐C), total cholesterol, and for the cholesterol‐to‐HDL ratio following single doses of RG7652 (see Supporting Information, Table 3, in the online version of this article) and multiple doses of RG7652 alone and with atorvastatin (data not shown). No significant changes in triglyceride or direct HDL‐C levels were observed.

Weekly doses of RG7652 at 40 mg and 150 mg through day 22 maintained the LDL‐C–lowering effects through at least day 36 without any apparent return to baseline (Figure 2F), and the effect on magnitude and duration increased with doses from 40 mg to 150 mg. With weekly 150‐mg doses of RG7652 without atorvastatin (cohort H), the mean decrease in LDL‐C from baseline at day 36 reached 75 mg/dL (90% confidence interval [CI]: 56–94 mg/dL, 58%) compared with 14 mg/dL (90% CI: 8–20 mg/dL, 9%) with placebo. Background atorvastatin therapy did not significantly affect the reduction in LDL‐C from baseline with weekly RG7652 at 40 mg (at day 36) or 150 mg (at day 10).

The efficacy and potency of RG7652 on LDL metabolism was also assessed in vitro in human liver cells (see Supporting Information, Methods, in the online version of this article). RG7652 concentrations needed for marked LDL‐uptake response in the HepG2 cell assay were consistent with exposure levels associated with robust LDL lowering in vivo (see Supporting Information, Results and Figure 3, in the online version of this article).

Figure 3.

Changes in cardiac biomarkers in response to single doses of RG7652. (A) Mean percentage change (± SE) over time in levels of ApoB, oxLDL‐C, Lp(a), and Lp‐PLA2 in the single‐dose cohorts. (B) Correlation in percentage change from baseline between the indicated biomarkers and LDL‐C in the RG7652‐treated single‐dose cohorts (day 1 to 36). Abbreviations: ApoB, apolipoprotein B; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); Lp‐PLA2, lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2; oxLDL‐C, oxidized low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; SE, standard error.

3.7. Biomarker analyses

In exploratory analyses, RG7652 treatment resulted in significant dose‐dependent reductions in apolipoprotein B (ApoB), oxidized low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (oxLDL), lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]), and lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 (Lp‐PLA2) vs placebo in both the single‐ and multiple‐dose cohorts (Figure 3; see also Supporting Information, Table 3, in the online version of this article). A single 800‐mg dose of RG7652 reduced levels of ApoB and oxLDL by up to 50% from baseline at day 15, and mean levels remained suppressed by 45% at 2 months after RG7652 administration. Single doses of RG7652 reduced serum Lp(a) levels in a dose‐related manner, with a mean reduction of 45% following an 800‐mg dose. Treatment with RG7652 also decreased serum Lp‐PLA2 mass levels by up to 30%. In the 800‐mg dose cohort, the mean Lp‐PLA2 levels remained suppressed for 2 months. The absolute levels of ApoB, oxLDL, and Lp‐PLA2 correlated with LDL‐C levels between days 1 and 36 (r2 = 0.88, 0.82, and 0.15, respectively; all P < 0.001), and the magnitude of the RG7652‐related changes in these biomarkers correlated with the change in LDL‐C (r2 = 0.87, 0.79, and 0.21, respectively; all P < 0.001). Although the absolute levels of Lp(a) did not correlate with LDL‐C levels (r2 = 0.01; P = 0.13), there was a correlation between the magnitudes of the percentage changes in Lp(a) and LDL‐C with RG7652 (r2 = 0.20; P < 0.001; Figure 3). No significant changes in apolipoprotein A1 or C‐reactive protein levels following treatment with RG7652 were detected in this small study.

4. DISCUSSION

The LDL‐C–lowering effects of RG7652 were generally consistent across key subgroups (sex, race, BMI, age) in this small study; all subjects treated with RG7652 doses ≥40 mg (± statin) had a reduction in LDL‐C of >18 mg/dL at 2 weeks after the first dose, similar to the effects achieved by AMG145 in a phase 1a study in healthy subjects.9 The duration of the effect increased with RG7652 dose and, as expected, the effect was maintained with weekly dosing.

The safety profile and maximal LDL‐C–lowering effects observed with RG7652 in this study were similar to previous studies with other anti‐PCSK9 antibodies.9, 10, 11, 12 However, the prolonged LDL‐C–lowering effects and safety profiles of high single subcutaneous doses of RG7652 (600 and 800 mg) have not to our knowledge been reported previously. RG7652 pharmacokinetic data suggest that a key to achieving prolonged effects is saturating ≥1 clearance mechanism, which may represent clearance mediated by drug‐PCSK9 complexes. As with RG7652, the lipid‐lowering effectiveness of other anti‐PCSK9 agents was not diminished in patients receiving statins.9, 10, 12 The substantial reduction of LDL‐C achievable with anti‐PCSK9 antibodies makes them well suited for trials to test whether LDL‐C reduction beyond the effect of statins yields a reduction in risk of cardiovascular disease.

In addition to traditional lipid risk factors (LDL‐C, total cholesterol, non–HDL‐C, cholesterol‐to‐HDL ratio, and ApoB), RG7652 also reduced the levels of oxLDL,13 Lp(a),14 and Lp‐PLA2,15 each of which have been shown to be independent predictors of cardiovascular risk. The observed PCSK9 antibody‐related reductions in Lp‐PLA2 mass and oxLDL levels are novel findings. The reduction in Lp‐PLA2 mass likely represents the clearance of Lp‐PLA2 bound to LDL‐C particles.16

The reduction of Lp(a) has been reported with other anti‐PCSK9 antibodies as well.10, 11, 12 Although the ability of PCSK9‐based therapies to lower plasma Lp(a) contradicts data supporting the absence of any major role for LDL receptor in Lp(a) catabolism,17 recent experimental data have suggested that LDL receptors can directly bind and internalize Lp(a) particles and that PCSK9 inhibition further amplifies this process.18 Hence, although LDL receptors may not be a major route of clearance of Lp(a) under most circumstances, their importance may increase in the setting of supraphysiological levels of the LDL receptors, such as is the case with the use of inhibitory molecules against PCSK9.18, 19

Two unique features of RG7652 offer a potential advantage over existing anti‐PCSK9 reagents. First, high solubility of RG7652 allows administration of higher doses of up to 800 mg. This unique characteristic of RG7652 enables more flexibility with dosing regimens and may support once‐per‐quarter administration. Second, the extremely low immunogenicity of RG7652 supports long‐term dosing without loss of exposure or the presence of immune complexes.

4.1. Study limitations

This study has several limitations: (1) a relatively small sample size in the treatment cohorts; (2) a short treatment duration in the multiple ascending dose study; (3) the study was performed with healthy subjects with low cardiovascular risk, which differs from the patient population most likely to benefit from such treatment; and (4) the limited number of multi‐dose regimens. Phase 2 is designed to further test different dosing regimens as well as pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics following 6 months’ dosing of RG7652 in patients with dyslipidemia and high cardiovascular risk.

5. CONCLUSION

Overall, RG7652 elicited substantial and sustained dose‐related LDL‐C reductions with an acceptable safety profile and minimal immunogenicity.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the subjects who participated in this study and the staff at the investigative sites, led by Drs Stoltz and Kissling. The authors thank Monica Kong‐Beltran for performing the HepG2 cell assay and Paul Moran for providing recombinant PCSK9. The authors also thank Kate Peng for her support in guiding the immunogenicity strategy and immunoassay development, Robert Hendricks for ensuring assay validation and sample analysis support for this study, and Sofia Mosesova for statistical review. This study was funded by Genentech Inc. Medical writing support was provided by Genentech Inc.

Author Contributions

WGT and RSK: Study conception, design, and implementation; data analysis and interpretation; manuscript drafting. DL and ML: Study conception and design; data analysis and interpretation; manuscript drafting. AB: Study conception, design, and implementation; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; manuscript drafting. KJC and JCD: Study conception and design; data interpretation; manuscript drafting. NRB: Study design; data analysis and interpretation; manuscript drafting. DK and AP: Study conception; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; manuscript drafting.

Conflicts of interest

All authors are employees of Genentech Inc., South San Francisco, CA. The authors declare no other potential conflicts of interest.

Baruch A, Luca D, Kahn RS, Cowan KJ, Leabman M, Budha NR, Chiu CPC, Wu Y, Kirchhofer D, Peterson A, Davis JC Jr and Tingley WG. A phase 1 study to evaluate the safety and LDL cholesterol–lowering effects of RG7652, a fully human monoclonal antibody against proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, Clin Cardiol, 2017;40:503–511. 10.1002/clc.22687

Funding information This study was funded by Genentech Inc. Medical writing support was provided by Genentech Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ference BA, Yoo W, Alesh I, et al. Effect of long‐term exposure to lower low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol beginning early in life on the risk of coronary heart disease: a Mendelian randomization analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2631–2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lagace TA, Curtis DE, Garuti R, et al. Secreted PCSK9 decreases the number of LDL receptors in hepatocytes and in livers of parabiotic mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2995–3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abifadel M, Varret M, Rabès JP, et al. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat Genet. 2003;34:154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH Jr, et al. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1264–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferri N, Corsini A, Sirtori CR, et al. Bococizumab for the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2017;17:237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berger JM, Vaillant N, Le May C, et al. PCSK9‐deficiency does not alter blood pressure and sodium balance in mouse models of hypertension. Atherosclerosis. 2015;239:252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gelzleichter TR, Halpern W, Erwin R, et al. Combined administration of RG7652, a recombinant human monoclonal antibody against PCSK9, and atorvastatin does not result in reduction of immune function. Toxicol Sci. 2014;140:470–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peng K, Xu K, Liu L, et al. Critical role of bioanalytical strategies in investigation of clinical PK observations: a phase I case study. MAbs. 2014;6:1500–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dias CS, Shaywitz AJ, Wasserman SM, et al. Effects of AMG 145 on low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol levels: results from 2 randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, ascending‐dose phase 1 studies in healthy volunteers and hypercholesterolemic subjects on statins. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1888–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang Y, Eigenbrot C, Zhou L, et al. Identification of a small peptide that inhibits PCSK9 protein binding to the low density lipoprotein receptor. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:942–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stein EA, Mellis S, Yancopoulos GD, et al. Effect of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9 on LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1108–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giugliano RP, Desai NR, Kohli P, et al; LAPLACE‐TIMI 57 Investigators . Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 in combination with a statin in patients with hypercholesterolaemia (LAPLACE‐TIMI 57): a randomised, placebo‐controlled, dose‐ranging, phase 2 study. Lancet . 2012;380:2007–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koren MJ, Scott R, Kim JB, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 as monotherapy in patients with hypercholesterolaemia (MENDEL): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet. 2012;380:1995–2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meisinger C, Baumert J, Khuseyinova N, et al. Plasma oxidized low‐density lipoprotein, a strong predictor for acute coronary heart disease events in apparently healthy, middle‐aged men from the general population. Circulation. 2005;112:651–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Erqou S, Kaptoge S, Perry PL, et al; Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration . Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. JAMA . 2009;302:412–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thompson A, Gao P, Orfei L, et al. Lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A(2) and risk of coronary disease, stroke, and mortality: collaborative analysis of 32 prospective studies. Lancet. 2010;375:1536–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rader DJ, Mann WA, Cain W, et al. The low density lipoprotein receptor is not required for normal catabolism of Lp(a) in humans. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1403–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Romagnuolo R, Scipione CA, Boffa MB, et al. Lipoprotein(a) catabolism is regulated by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 through the low density lipoprotein receptor. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:11649–11662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Merki E, Graham MJ, Mullick AE, et al. Antisense oligonucleotide directed to human apolipoprotein B‐100 reduces lipoprotein(a) levels and oxidized phospholipids on human apolipoprotein B‐100 particles in lipoprotein(a) transgenic mice. Circulation. 2008;118:743–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1