Abstract

Background

The present European guidelines suggest a diagnostic electrophysiological (EP) study to determine indication for cardiac pacing in patients with bundle branch block and unexplained syncope. We evaluated the prognostic relevance of an EP study for mortality and the development of permanent complete atrioventricular (AV) block in patients with symptomatic bifascicular block and first‐degree AV block.

Hypothesis

The HV interval is a poor prognostic marker to predict the development of permanent AV block in patients with symptomatic bifascicular block (BFB) and AV block I°.

Methods

Thirty consecutive patients (mean age, 74.8 ± 8.6 years; 25 males) with symptomatic BFB and first‐degree AV block underwent an EP study before device implantation, according to current guidelines. For 53 ± 31 months, patients underwent yearly follow‐up screening for syncope or higher‐degree AV block.

Results

Thirty patients presented with prolonged HV interval during the EP study (mean, 82.2 ± 20.1 ms; range, 57–142 ms), classified into 3 groups: group 1, <70 ms (mean, 62 ± 4 ms; range, 57–67 ms; n = 7), group 2, >70 to ≤100 ms (mean, 80 ± 8 ms; range, 70–97 ms; n = 18), and group 3, >100 ms (mean, 119 ± 14 ms; range, 107–142 ms; n = 5). According to the guidelines, patients in groups 2 and 3 received a pacemaker. The length of the HV interval was not associated with the later development of third‐degree AV block or with increased mortality.

Conclusions

Our present study suggests that an indication for pacemaker implantation based solely on a diagnostic EP study with prolongation of the HV interval is not justified.

Keywords: HV Interval, Bifascicular Block, AV Block, SYNCOPE, PACEMAKER, Implantable Loop Recorder

1. INTRODUCTION

Patients with bifascicular block (BFB) have previously been shown to have an increased risk for the occurrence of higher‐degree atrioventricular (AV) block associated with an increased morbidity and mortality,1 coronary artery disease, and an increased risk for the development of heart failure.2

Therefore, the present European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Heart Rhythm Association guidelines see an indication for cardiac pacing in patients with bundle branch block (BBB), unexplained syncope, and abnormal electrophysiological (EP) study, with a class I recommendation.3 The EP study comprises measurement of an HV interval >70 ms or second‐ or third‐degree His‐Purkinje block during incremental pacing or pharmacological blockade with class I antiarrhythmic medication. A nondiagnostic EP study or simply omitting the EP study leads to a downgrade for cardiac pacing in patients with BBB from a class I to a class IIb indication. Interestingly, this class I recommendation is backed up by only 2 references.4, 5

On the basis of these findings, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the prognostic relevance of an EP study for the development of high‐degree AV block in patients with symptomatic BFB and first‐degree AV block.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study patients and ECG analysis

Thirty consecutive patients with symptomatic right bundle branch block (RBBB), left anterior hemiblock (LAH), and first‐degree AV block were included in the present observational study, which spanned April 2008 to June 2010. All patients underwent an EP study. Symptoms were defined as the occurrence of presyncope (n = 3), syncope (n = 21), documented asystole of >6 seconds (n = 2), advanced structural heart disease, or a combination of these factors (n = 4). Patients were followed for 5 years, with yearly follow‐up visits focusing on the occurrence of syncope or higher‐degree AV block. In case of death, cause of death was classified on the basis of available source documents.

The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from each patient before the study.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean ± SD. Data were entered into a computerized database (Excel; Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and tested for normal distribution employing the Shapiro‐Wilk test. The t test was used to determine differences between groups, with significance set at P < 0.05 (2‐sided).

3. RESULTS

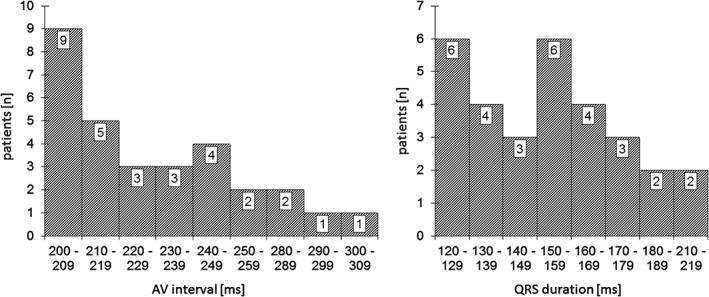

Thirty consecutive patients (mean age, 74.8 ± 8.6 years; 25 males [83%]) were enrolled in the study over a period of 42 months. Baseline clinical characteristics of the study patients are presented in Table 1. All patients presented with RBBB + LAH and first‐degree AV block (Figure 1). Figure 2 depicts the distribution of AV intervals and the range of the QRS durations. Furthermore, all patients displayed a prolonged HV interval during the EP study (mean, 82.2 ± 20.1 ms; range, 57–142 ms). Patients were classified into 3 groups, according to HV interval: group 1, <70 ms (mean, 62 ± 4 ms; range, 57–67 ms; n = 7), group 2, >70 to ≤100 ms (mean, 80 ± 8 ms; range, 70–97 ms; n = 18), and group 3, >100 ms (mean, 119 ± 14 ms; range, 107–142 ms; n = 5; Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics I

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 30 | 100 |

| Male sex | 25 | 83 |

| Age, y | ||

| 50–69 | 8 | 26 |

| 70–79 | 11 | 37 |

| ≥80 | 11 | 37 |

| Medications | ||

| ACEI/ARB | 30 | 100 |

| β‐Blocker | 21 | 70 |

| Thiazide diuretic | 15 | 50 |

| Loop diuretic | 12 | 40 |

| LVEF, % | ||

| ≥55 | 15 | 50 |

| 30–55 | 13 | 43 |

| <30 | 2 | 7 |

| CV risk factors | ||

| None | 2 | 7 |

| HTN | 25 | 83 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 14 | 47 |

| DM | 12 | 40 |

| Smoking | 2 | 7 |

| Structural heart disease | ||

| CHD | 14 | 56 |

| Valvular heart disease | 6 | 24 |

| DCM | 3 | 12 |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; CHD, coronary heart disease; CV, cardiovascular; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; LV, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Figure 1.

Distribution of AV interval and QRS duration. Abbreviations: AV, atrioventricular; QRS, QRS complex.

Figure 2.

Electrocardiogram examples for patients in (1A, 1B) group 1, (2A, 2B) group 2, and (3A, 3B) group 3.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics II

| Group 1, n = 7 | Group 2, n = 18 | Group 3, n = 5 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HV interval , ms | 62.3 ± 4.1 (57 to 67) | 79.6 ± 7.7 (70 to 97) | 119.4 ± 14.4 (107 to 142) | 0.001 |

| Age, y | 78.1 ± 6.9 (66 to 86) | 74 ± 8.8 (52 to 86) | 73.2 ± 11.8 (54 to 84) | 0.42 |

| QRS width, ms | 144.4 ± 33.8 (120 to 215) | 154.6 ± 19.3 (120 to 184) | 161 ± 31.8 (122 to 210) | 0.29 |

| QRS axis, degrees | −55.7 ± 16.9 (−80 to −30) | −64.4 ± 15.5 (−85 to −30) | −68 ± 13 (−90 to −60) | 0.37 |

| LVEF, % | 50 ± 12.6 (25 to 60) | 51.3 ± 10.4 (30 to 60) | 40 ± 13.7 (20 to 55) | 0.17 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; QRS, QRS complex; SD, standard deviation.

Data are presented as mean ± SD (IQR).

The prolongation of the HV interval was associated with decreased left ventricular (LV) function (Table 2). The indication for pacemaker (PM) implantation was independently evaluated in all patients according to the ESC guidelines for pacing and resynchronization. As a result, 22 patients (73%) subsequently received a device. All patients in groups 2 and 3 were implanted, except for 1 patient who denied PM implantation.

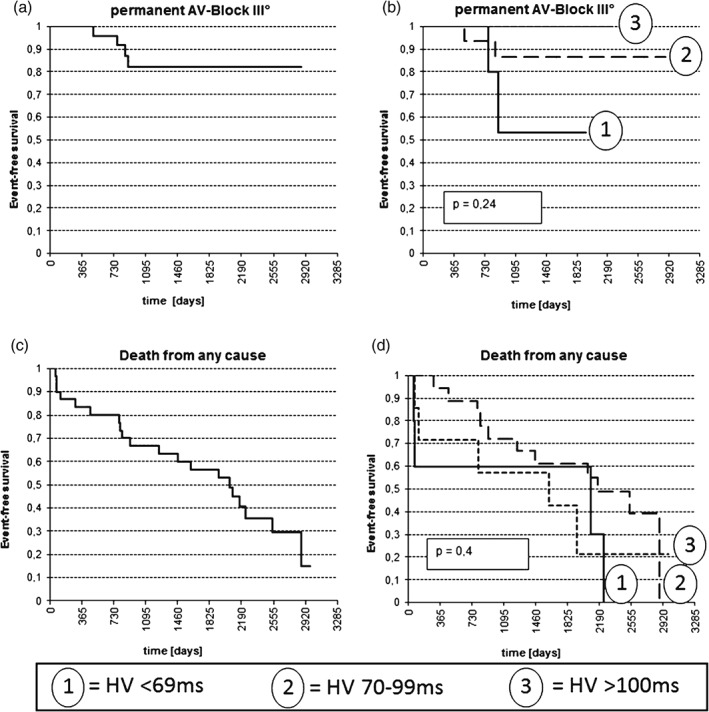

The mean follow‐up duration was 53 ± 31 months. During follow‐up, no further syncope occurred in this patient cohort. Four patients (13%) developed a permanent third‐degree AV block (Figure 3). Of note, 3 of these 4 patients had previously received a device. Hence, 19 patients with PM developed no high‐degree AV block during this long‐term follow‐up.

Figure 3.

Kaplan‐Meier curves regarding development of (A,B) permanent AV block and (C,D) event‐free survival in (A,C) all patients and in (B,D) the different HV interval groups. Abbreviations: AV, atrioventricular.

Twenty patients (67%) died during follow‐up. The exact length of the HV interval was not associated with the later development of third‐degree AV block or with an increased mortality (Figure 3). However, patients with moderately to severely impaired LV function had a significantly reduced life expectancy, with a median survival time of 915 days, as compared with 2538 days for patients with normal systolic LV function (P = 0.01). In this context, HV interval demonstrated a slight negative correlation to systolic LV function (Rs = −0.32), which was significant (P = 0.04). Of note, this patient cohort was rather old; the mean age of death was 80.6 years.

Regarding mortality, 65% of patients who died during follow‐up died from noncardiac causes. Among the remaining patients who died from cardiac causes, 1 patient died suddenly, whereas all other remaining patients died from progression of heart failure.

4. DISCUSSION

The results of the present study underline that in symptomatic patients with BFB, an additional first‐degree AV block most likely results from an infrahisian conduction delay. The progression rate to a permanent third‐degree AV block is independent from the measured HV interval and remains rather low. Total mortality and cardiac mortality were associated with a reduced LV function, whereas no association with the length of the HV interval was observed. In contrast to previous studies, duration of follow‐up was significantly longer in the present study. Furthermore, all patients presented a prolonged HV interval without pharmacologic provocation testing or atrial pacing, which have been employed in the previously referred studies.4, 5 The first study, by Twidale et al,4 determined a cutoff value of 60 ms for an increased HV interval and observed that none of the EP study maneuvers induced third‐degree AV block. In contrast, procainamide induced transient AV block in 7 of 89 patients. Only 3 of these 7 patients, however, developed AV block during an observation period of up to 10 years, with a mean observation period of 46 months. The second reference shows that a prolonged HV interval, an infrahisian block with atrial pacing, or a class Ic antiarrhythmic drug challenge during EP study has acceptable specificity but a low sensitivity for the diagnosis of syncope.5 This is supported by the fact that nearly half of the patients with negative EP study (45%) later display arrhythmias in the implantable loop recorder. These findings were underlined by studies from the 1980s and ’90s.6, 7, 8

In their study, Martí‐Almor and colleagues demonstrated a similar follow‐up period of 4.5 years.9 Their patient cohort was of comparable age (73 ± 9 years vs 75 ± 9 years, respectively) but included more women (33% vs 17%, respectively). The study by Martí‐Almor et al described 23% of patients with “significant AV block,” compared with only 13% with complete AV block in our study. In contrast to our study, they also included patients with complete left bundle branch block and RBBB plus left posterior hemiblock, which showed a higher need for PM (46% and 57%, respectively), compared with patients with RBBB+ LAH (35%), as recruited in our study. Furthermore, our definitions of AV block were different.

These results challenge the recommendations of the current ESC guidelines for cardiac pacing and resynchronization. Here, a class Ib recommendation for PM implantation was issued for patients with BBB and a positive EP study exclusively based on 2 studies. The first is nearly 30 years old,4 whereas the second and more recent reference admits that the sensitivity and specificity of a prolonged HV interval is rather low regarding the development of permanent AV block.5

The present guidelines for syncope in patients with BBB also state that the risk for development of AV block in BBB patients may depend on a history of syncope and a prolonged HV interval.10 However, about one‐third of the patients with negative EP study who received an implantable loop recorder developed intermittent or permanent AV block during follow‐up.11 The authors of the current ESC guidelines for syncope therefore concluded that EP study in general has a low sensitivity and specificity for development of permanent AV block. This is in line with our findings, which did not show any discriminatory value of HV interval for the development of permanent AV block.

Interestingly, the landmark study of Scheinman et al12 does not show an increased risk of developing AV block for patients with an HV interval up to 70 ms, with 4% and 2%, respectively, for HV intervals of <55 ms and 56 ms to 69 ms. For patients with an HV interval of 70 to 100 ms and >100 ms, the risk for developing permanent AV block increased to 10% and 24%, respectively.12 In contrast to our own study, all patients were asymptomatic and showed no differences in mortality, whether they consecutively received PM implantation or not. Patients with PM implantation were only relieved from neurological symptoms. Thus, the prognostic value of a prolonged HV interval in the presence of a BFB involving the RBBB remains controversial. Dhingra et al13 see no difference in the development of AV block between patients with prolonged and normal HV intervals in the pre–loop recorder era, whereas Moya et al5 report asymptomatic paroxysmal higher‐degree AV block episodes in almost 70% of patients.

In our own study, an increased HV interval predicted neither an increase in permanent AV block nor an increased mortality due to rhythm disorders. HV interval, however, correlated with increased heart insufficiency.

4.1. Study limitations

The main limitation of this study is the rather small sample size. Furthermore, our definition of AV block as stimulation >95% or ECG documentation distinctively excludes paroxysmal AV block. In our study, we also do not sufficiently examine the quality of life in older people, which might be affected by paroxysmal AV block, even if it does not affect mortality. In older patients where not many device replacements are expected, a PM implantation might be less burdensome than the more academic diagnostic affirmation by implantable loop recorder with sequential PM implantation and might be therefore preferable.

5. CONCLUSION

Our present study suggests that an indication for PM implantation based on a prolongation of the HV interval is not justified. Previous landmark studies showed a correlation between HV interval and permanent AV block; however, they fell short of showing any increase in mortality due to heart block. As in our study, many previous studies also proved that EP study is not a sufficiently sensitive means to predict those patients who will benefit from PM implantation. Here the implantable loop recorder provides clearly superior results. Perhaps now is the time for the implantable loop recorder to receive its proper place in the guidelines for pacing and to release the EP study, as the stress ECG has been replaced in the noninvasive ischemia diagnosis by far more sensitive methods, to secure a more patient‐tailored approach.

5.1. Author Contributions

Harilaos Bogossian, MD, and Gerrit Frommeyer, MD, contributed equally to this article.

5.2. Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Bogossian H, Frommeyer G, Göbbert K, et al. Is there a prognostic relevance of electrophysiological studies in bundle branch block patients?. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:575–579. 10.1002/clc.22700

REFERENCES

- 1. Pine MB, Oren M, Ciafone R, et al. Excess mortality and morbidity associated with right bundle branch and left anterior fascicular block. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;1:1207–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang ZM, Rautaharju PM, Soliman EZ, et al. Mortality risk associated with bundle branch blocks and related repolarization abnormalities (from the Women's Health Initiative [WHI]). Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:1489–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brignole M, Auricchio A, Baron‐Esquivias G, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the task force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) . Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Europace. 2013;15:1070–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Twidale N, Heddle WF, Tonkin AM. Procainamide administration during electrophysiology study—utility as a provocative test for intermittent atrioventricular block. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1988;11:1388–1397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moya A, García‐Civera R, Croci F, et al; Bradycardia Detection in Bundle Branch Block (B4) Study . Diagnosis, management, and outcomes of patients with syncope and bundle branch block. Eur Heart J . 2011;32:1535–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scheinman MM, Peters RW, Morady F, et al. Electrophysiologic studies in patients with bundle branch block. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol . 1983;6(5 part 2):1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Petrac D, Radić B, Birtić K, et al. Prospective evaluation of infrahisal second‐degree AV block induced by atrial pacing in the presence of chronic bundle branch block and syncope. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1996;19:784–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Englund A, Bergfeldt L, Rosenqvist M. Disopyramide stress test: a sensitive and specific tool for predicting impending high‐degree atrioventricular block in patients with bifascicular block. Br Heart J. 1995;74:650–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martí‐Almor J, Cladellas M, Bazán V, et al. Novel predictors of progression of atrioventricular block in patients with chronic bifascicular block [article in Spanish]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2010;63:400 – 408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2631–2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brignole M, Menozzi C, Moya A, et al; International Study on Syncope of Uncertain Etiology (ISSUE) Investigators. Mechanism of syncope in patients with bundle branch block and negative electrophysiological test. Circulation . 2001;104:2045–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scheinman MM, Peters RW, Suavé MJ, et al. Value of the H‐Q interval in patients with bundle branch block and the role of prophylactic permanent pacing. Am J Cardiol. 1982;50:1316–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dhingra RC, Palileo E, Strasberg B, et al. Significance of the HV interval in 517 patients with chronic bifascicular block. Circulation. 1981;64:1265–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]