Abstract

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) remains the leading cause of mortality in women. Historically, medical research has focused on male patients, and subsequently, there has been decreased awareness of the burden of ASCVD in females until recent years. The biological differences between sexes and differences in societal expectations defined by gender roles contribute to gender differences in ASCVD risk factors. With these differing risk profiles, risk assessment, risk stratification, and primary preventive measures of ASCVD are different in women and men. In this review article, clinicians will understand the risk factors unique to women, such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, and those that disproportionately affect them such as autoimmune disorders. With these conditions in mind, the approach to ASCVD risk assessment and stratification in women will be discussed. Furthermore, the literature behind the effects of primary preventive measures in women, including lifestyle modifications, aspirin, statins, and anticoagulation, will be reviewed. The aim of this review article was to ultimately improve ASCVD primary prevention by reducing gender disparities through education of physicians.

Keywords: Cardiovascular Disease, Disparities, Prevention, Women

1. INTRODUCTION

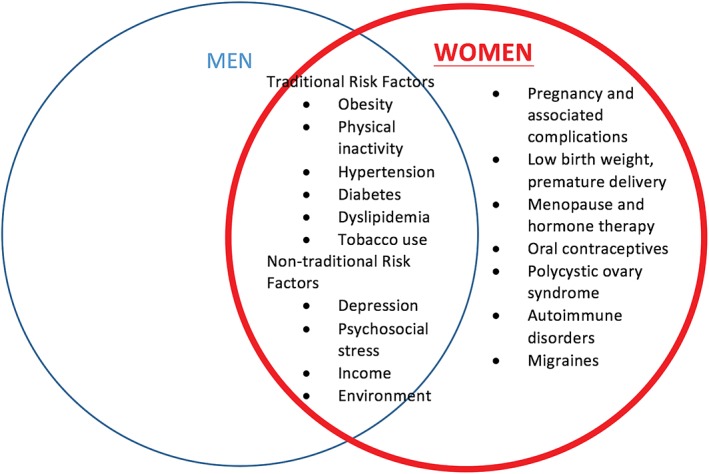

Although traditionally misconceived as a “man's disease,” atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) remains the leading cause of death among women. With an increase in awareness and appropriate therapies, ASCVD‐associated deaths among both genders >65 years of age in the United States have declined.1 However, there has been an increase in the average annual rate of death from coronary heart disease (CHD) among young women aged 35 to 54 years, whereas there has been a decrease in the annual rate of death in men of the same age group.1 The gender differences in ASCVD risk profiles (Figure 1) are, therefore, important to understand to reduce this burden on women. These differences range from varying sex‐chromosome–related gene expression to differing behaviors, lifestyles, environment, and expectations arising from sociocultural practices according to gender. Based on these differences, the American Heart Association (AHA) published guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular (CV) disease in women in 2011.2 A high‐level overview of these guidelines in conjunction with additional evidence on prevention of ASCVD that has emerged since 2011 will be discussed to provide a comprehensive approach to risk assessment and stratification of ASCVD in women, as well as a review of effective preventive measures.

Figure 1.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors in women

2. RISK FACTORS FOR CV DISEASE UNIQUE TO WOMEN

2.1. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

Although gestational hypertension and preeclampsia resolve within 3 months postpartum, they are associated with residual vascular dysfunction and increased ASCVD risk in women, recognized as a major risk factor by the 2011 AHA guidelines.2

The placenta is hypoperfused, and inflammatory cytokines and antiangiogenic proteins are released in preeclampsia, leading to systemic endothelial dysfunction, vasoconstriction, and reduced perfusion to various organ systems. The CHAMPS (Cardiovascular Health After Maternal Placental Syndromes) study of 1.03 million women showed a 12‐fold higher risk of ASCVD in women with a history of preeclampsia and metabolic syndrome compared to those without either condition.3

A systematic review of prospective and retrospective cohort studies showed women with preeclampsia had an increased risk of developing hypertension at 14 years (relative risk [RR]: 3.7; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.7‐5.05), ischemic heart disease at 12 years (RR: 2.16; 95% CI: 1.86‐2.52), and stroke at 10 years (RR: 1.81; 95% CI: 1.45‐ 2.27). The relative risk of overall mortality after 14.5 years in women with preeclampsia was increased at 1.49 (95% CI: 1.05‐2.14).4 However, only 3 of the 25 studies adjusted for diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and smoking, and most only adjusted for age. It is unclear if there is a common cause for preeclampsia and ASCVD, or if preeclampsia leads to ASCVD development, or both. However, as evidence shows an undeniable association between preeclampsia and ASCVD, pregnancy histories should be obtained, and those with a history of preeclampsia should be considered at risk for ASCVD and undergo appropriate education, counseling, and preventive interventions.

2.2. Gestational diabetes

In addition to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, gestational diabetes independently increased the risk of ASCVD (odds ratio [OR]: 1.26; 95% CI: 0.95‐1.68) in a prospective cohort of 3416 women in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children.5 However, in another study of gestational diabetes mellitus patients, after controlling for subsequent diabetes mellitus, the relative risk of ASCVD decreased from 1.7 (95% CI: 1.08‐2.69) to 1.13 (95% CI: 0.67‐1.89) and lost statistical significance,6 indicating the increased risk is likely secondary to the development of diabetes, a traditional risk factor of ASCVD.

2.3. Oral contraceptives

Oral contraceptives (OC) have been thought to increase the risk of ASCVD by a thrombotic mechanism. A large cohort study of hormonal contraception including over 1.6 million Danish women from the ages of 15 to 49 years showed that ethinyl estradiol doses of 20 μg or 30 to 40 μg were associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) (RR: 1.4 and 1.88, respectively). The risks did not differ significantly between the types of progestin.7 However, as MI is extremely rare in healthy, premenopausal women, doubling the risk results in an extremely low population attributable risk.7 On the other hand, OC should not be prescribed for women who are over the age of 35 years and smoke, per the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.8 Furthermore, they should be prescribed with caution if they have any other CV risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

2.4. Menopause and menopausal hormone therapy

The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/AHA identifies postmenopausal status as a risk factor for ASCVD.2 However, an important confounding variable to this association is the increase in the traditional ASCVD risk factors in postmenopausal women.

With observational studies in the late 1980s showing protective effects of estrogen on the heart and menopause's contribution to a higher risk of ASCVD, physicians began prescribing long‐term estrogen therapy as primary prevention for CHD. Estrogen modulates the nitric oxide and vasodilation pathway after binding to estrogen receptor‐α on endothelial cells, and thereby improves endothelial function.8 However, the results of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) and the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) shifted this paradigm. The combined estrogen–progestin therapy group of the WHI was at increased risk for total ASCVD, including CHD (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.29; 95% CI: 1.02‐1.63), stroke (HR: 1.41; 95% CI: 1.07‐1.85), and total CV disease (HR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.09‐1.36) over an average follow‐up of 5.2 years.9 The use of unopposed estrogen did not affect CHD (HR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.75‐1.12), but increased the risk of stroke (HR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.10‐1.77) and total CV disease (HR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.01‐1.24).10 There was no difference in incidence of CHD events between the estrogen–progestin and placebo group in the HERS trial, despite a decrease in low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) and an increase in high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) in the experimental group.11 Based on these results, the current recommendation of the US Preventive Services Task Force is against the use of combined estrogen and progestin or estrogen alone for prevention of ASCVD in menopausal women.

3. RISK FACTORS FOR CV DISEASE THAT DISPROPORTIONATELY AFFECT WOMEN

3.1. Autoimmune disorders

Systemic autoimmune disorders occur predominantly in women, which predisposes them to chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and accelerated atherosclerosis. Women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) between the ages of 35 and 44 years were found to be more likely to have an MI, compared to their age‐matched counterparts in the Framingham cohort (RR: 52.43; 95% CI: 21.6‐98.5).12

4. GENDER DISPARITIES IN TRADITIONAL ASCVD RISK FACTORS

In both women and men, the traditional risk factors, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and smoking, are strongly associated with ASCVD risk. However, there are sex differences in prevalence and magnitude of associated ASCVD risk (Table 1). Obesity and sedentary behavior are more common in women.13 Weight gain during pregnancy may contribute to the sex difference in the prevalence of obesity, whereas barriers to physical activity (PA) are different in women than in men, in part because of traditional female gender roles such as caretaker responsibilities.14 Smoking is more prevalent in men (20.5%) than in women (15.9%),1 but the relative risk of CHD associated with smoking is 25% greater in women than in men, even after adjustment for other CV risk factors.15 The reason for this discrepancy is not known. Differences in nicotine metabolism and smoking behavior have been suggested as possible mechanisms.

Table 1.

Traditional ASCVD risk factors in women

| Risk Factor | Sex‐Based Differences | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | Diabetic women are more likely to develop and die from CVD than their male counterparts. | Women with DM should have aggressive management of their CVD risk factors, including statin and aspirin initiation. |

| Hypertension | Over the age of 60 years, hypertension is more prevalent in women than men. | 2013 JNC8 hypertension guidelines call for a BP goal of either 140/90 or 150/90 mmHg depending on age, presence of diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. |

| Women have less optimization of their hypertension compared to men. | Encourage lifestyle modifications. | |

| Dyslipidemia | Dyslipidemia has the highest PAR of 47.1%, compared to other risk factors, in women. | Statins are recommended for primary prevention in women according to the 2013 ACC guidelines, although randomized trial evidence is limited. |

| Statins are effective for secondary prevention in both women and men. | ||

| Obesity, physical inactivity | In the United States, obesity is more common in women than in men (35.5% vs 33.8%). | For weight loss, or sustaining weight loss, women must exercise a minimum of 60 to 90 min of at least moderate‐intensity on most and preferably all days of the week. |

| Obesity poses a greater risk of CHD in women. | ||

| Smoking | There is 25% greater relative risk of CHD with smoking in women than in men. | Women should be advised not to smoke and to avoid secondhand smoke. |

| Counseling, nicotine replacement, and medical and/or behavioral therapy should be provided. |

Abbreviations: ACC, American College of Cardiology; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BP, blood pressure; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; JNC8, 8th Joint National Committee; PAR, population‐attributable risk.

Diabetic women are more likely to both develop and die from CVD than their male counterparts.16 In fact, impaired fasting glucose alone causes increased CHD risk in women to a similar extent as diabetes does, an association not observed in men.17 Despite this, diabetic women with CHD are less likely to be treated with aspirin and less likely to have their hyperlipidemia and hypertension optimized than similarly affected men.18 Women are also less likely to have their hypertension controlled compared to men (54% vs 58.7%, respectively; P < 0.02), especially with older age (53.4% vs 63.2% for ages 65–80 years; P < 0.005).19

5. GENDER DISPARITIES IN NONTRADITIONAL ASCVD RISK FACTORS

5.1. Depression

Depression is associated with increased mortality following MI and moderately increased risk for future major adverse cardiac events.20 In the large, international case–control study INTERHEART (The Effect of Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors Associated with Myocardial Infarctionin 52 countries), psychosocial factors had significant gender differences: women had higher contributions from psychosocial risk factors (45.2% vs 28.8% in men).21 A study of 3237 patients found that depressive symptoms predicted the presence of coronary artery disease (CAD) in women ≤55 years old (OR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.02‐1.13) and increased risk of death in this group of women (adjusted HR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.02‐1.14).22

5.2. Social determinants of health

Psychosocial stressors, such as perceived stress, life events, have been associated with increased ASCVD risk.21 Women are especially vulnerable, as they represent 60% of the world's poor and 66% of illiterate adults,23 given the differential distribution of income in men vs women. The WISE (Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation) study showed that income was a significant predictor of CV death or MI, after adjusting for angiographic coronary disease, chest pain symptoms, and traditional risk factors.24

5.3. Risk markers for atherosclerosis

The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines recommend addressing novel markers to enhance risk classification in individuals at intermediate risk.25 Inflammatory markers, such as high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hsCRP), are thought to be subclinical markers associated with increased CV risk independent of a woman's lipid profile.26 hsCRP is the most extensively examined of the novel markers addressing CV risk. In the JUPITER (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin) trial, asymptomatic women ≥60 years old and men ≥50 years old with elevated hsCRP (≥2 mg/L), low LDL levels (<130 mg/dL), and triglyceride levels <500 mg/dL were randomized to receive statin or placebo therapy. In those treated with statin therapy, incident ASCVD was reduced by 44% and all‐cause mortality by 20%.26

The coronary artery calcium (CAC) score was developed as a noninvasive marker for vascular disease. Calcification of the coronary arteries is measured in Hounsfield units in gated computed tomography imaging, and is converted to an Agatston score (area × density). In the MESA (Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) study, the relative risk for developing CAC in those deemed intermediate to high risk (>10%) by the Framingham Risk Score, compared to low risk (<10%) was 2.41 (95% CI: 1.57‐3.72) in women and 1.62 (95% CI: 1.16‐2.27) in men (P value for interaction 0.07).27 Although currently not endorsed for routine screening by the guidelines, a CAC score can be a useful method to reclassify risk assessment when a patient's risk based on ASCVD pooled cohort equation is unclear or intermediate.25

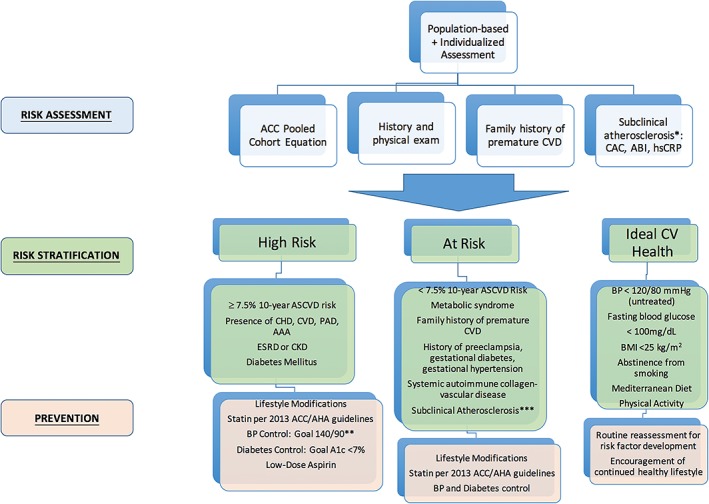

6. RISK ASSESSMENT AND STRATIFICATION

The Framingham Risk Score is a clinical tool of standard risk classification that is limited to assessing only short‐term (10‐year) risk of adverse cardiac events in patients without known CAD and where a high prevalence of subclinical ASCVD was found in women categorized as low risk.28 In 2011, based on clinical data on women at high risk and healthy women, the AHA established guidelines for cardiac risk assessment to target the prevention of ASCVD in women (Figure 2), with preeclampsia, and SLE gaining recognition in their contribution to female CV risk assessment.2 Expanding the ASCVD composite to include stroke and CHD, serious nonfatal outcome events, and mortality, the pooled cohort ASCVD risk equation was then derived in 2013 and incorporated traditional ASCVD risk factors. Although this risk stratification method was not developed specifically for women, as the 2011 guidelines were, it has been internally validated for several cohorts of women, including those from the WHI, ranging from 40 to 79 years, and provides a 10‐year ASCVD risk estimate and lifetime risk estimate.25 Therefore, risk stratification of female patients should include both the 2013 ACC pooled cohort equation and assessment for risk factors unique to or predominant in women, such as pregnancy complications and autoimmune disease, according to the 2011 guidelines.

Figure 2.

Approach to comprehensive risk assessment, risk stratification, and primary prevention of ASCVD in women. Abbreviations: AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; ABI, ankle‐brachial index; ACC, American College of Cardiology; ACC/AHA, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CAC, coronary artery calcium; CV, cardiovascular; CHD, coronary heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ESRD, end‐stage renal disease; hsCRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; PAD, peripheral artery disease

7. PREVENTIVE MEASURES

7.1. Lifestyle modifications

The AHA/ACC recommends all adults consume a high intake of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, as well as low‐fat dairy products, poultry, fish, legumes, nontropical vegetable oils, and nuts. Three to 4 sessions per week of aerobic PA lasting an average of 40 min, at a moderate to vigorous intensity, for all adults is also recommended.29 Women may benefit more from PA than men, as the median ASCVD risk reduction associated with PA between most active women and least active women is 40%, whereas in men it is 30%.13 Therefore, the 2011 AHA guidelines for women recommend at least 150 min of moderate exercise per week or 75 min of vigorous exercise per week or a combination of both. Episodes of at least 10 min of aerobic activity spread throughout the week is also advised. For women who need to lose weight or sustain weight loss, a minimum of 60 to 90 min of at least moderate‐intensity PA on most and preferably all days of the week is recommended.2 The 2013 AHA/ACC guidelines on lifestyle management may be used for all female patients, but some may find more benefit in the women‐specific 2011 guidelines, especially those on weight loss. Women may also profit from attending female‐only classes, as women have reported improved diet behavior and less depressive symptoms, compared to women attending mixed‐sex classes.30

Solutions must be sought to reconcile the gap between current understanding of exercise's CV benefits and implementation of exercise to reap those benefits. For instance, treating exercise frequency as a vital sign that is recorded routinely at doctors' visits, viewing PA as a multidisease‐targeting pharmaceutical equivalent that can be prescribed are ways in which PA can be incorporated into a complete care plan.

7.2. Aspirin

The Women's Health Study sought to evaluate the use of aspirin for primary prevention of ASCVD.31 Of the 40 000 healthy women, those who received 100 mg of aspirin every other day experienced a reduction in the risk of total strokes and ischemic strokes, with no difference in the risk of MI or death from CV events during a follow‐up period of 10 years. However, women ≥65 years old exhibited the most consistent benefit of aspirin, with a significantly reduced risk of both MI (RR: 0.66; 95% CI: 0.44‐0.97; P = 0.04) and ischemic stroke (RR: 0.7; 95% CI: 0.49‐1; P = 0.05) when compared to placebos (Table 2). The Hypertension Optimal Treatment study32 had similar results, but the mechanisms remain unclear.

Table 2.

Summary of evidence for primary prevention with aspirin and statins in women

| Study | Study Type | Population | Intervention | Outcomes | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | Women's Health Study 2005 | Randomized controlled trial | 40 000 healthy women | 100 mg of aspirin every other day vs placebo | Stroke: RR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.69‐0.99, P = 0.04 Ischemic stroke: RR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.63‐0.93, P = 0.009 No significant difference in risk of MI or death from CV events Women age 65 years or older had significantly reduced risk of major cardiovascular events, ischemic stroke, and MI on aspirin. |

Aspirin lowered the risk of stroke, but did not reduce the risk of MI in women younger than the age 65 years. |

| Statins | JUPITER 2008 | Randomized controlled trial | 6801 healthy women (38.2% of study population) | 20 mg of rosuvastatin daily vs placebo | MI: HR: 0.46; 95% CI: 0.3‐0.7, P = 0.0002 Stroke: HR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.34‐0.79, P = 0.002 Revascularization or unstable angina: HR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.4‐0.7; P < 0.00001 Combined endpoint of MI, stroke, or death from CV causes: HR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.40‐0.69, P < 0.00001 |

Rosuvastatin significantly reduced the incidence of major cardiovascular events. |

| Walsh et al. 2004 | Meta‐analysis | 6 trials of 11 435 women without CVD | Lipid‐lowering medications (1 trial used colestipol; others used lovastatin, simvastatin, pravastatin, atorvastatin) | Total mortality: RR: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.62‐1.46 CHD mortality: RR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.47‐2.40 Nonfatal MI: RR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.22‐1.68 Revascularization: RR: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.33‐2.31 CHD events: RR: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.69‐1.09 |

For primary prevention, lipid lowering did not affect total or CHD mortality or major cardiovascular events. |

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio; MI, myocardial infarction; RR, relative risk.

7.3. Statins

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study showed that elevated LDL and low HDL are independent risk factors for CHD in women, as are elevated triglyceride levels, which were not shown to have a similar association to CHD in men; these risk factors provided a larger relative risk of CHD in women than men.33 However, in primary prevention trials, lipid‐lowering medications did not reduce total mortality, CHD mortality, MI, revascularization, or CHD events in women, despite lowering of cholesterol in both sexes (Table 2).34 The wider confidence intervals of these aforementioned endpoints in women are likely secondary to the overall lower incidence of CHD in women and their under‐representation in these trials. With a large number of female participants (38.2%), the JUPITER trial concluded that women without overt dyslipidemia with increased hsCRP experienced a greater reduction in major adverse cardiac events than similarly affected men when placed on high‐intensity rosuvastatin (Table 2).35 A 2015 meta‐analysis of 6 clinical trials, however, showed no significant difference in statin‐related ASCVD benefits between the sexes.36 Given its lack of differing gender recommendations, the current 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines of treatment with statins37 should be considered for female patients, despite the existing, equivocal data on statins' primary prevention benefits in women.

7.4. Anticoagulation

Men have a greater risk of developing atrial fibrillation, but female gender is an independent risk for stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Some meta‐analyses have demonstrated an increased stroke risk of 1.31 (95% CI: 1.18‐1.46) for women with atrial fibrillation compared to men,38 leading to recommendation of the use of the CHA2DS2‐VASc (Congestive heart failure,

Hypertension, Age ≥ 75 years, Diabetes mellitus, Stroke or transient ischemic attack, Vascular disease, Age 65–74 years, Sex category), which incorporates a point for female sex.39 The reasons for this increased risk are most likely due to the comorbidities that increase the risk of thromboembolic events. With the advancement of direct oral anticoagulants, 4 studies have specifically investigated sex difference in efficacy of treatment,38 which illustrated no significant difference in stroke prevention with direct oral anticoagulants between females and males.

8. GAPS, BARRIERS, AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

After extensive efforts by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the AHA's Go Red for Women campaign, awareness of ASCVD in women increased from 30% in 1997 to 57% in 2006, but plateaued in 2009 with a lower rate among ethnic minorities.14 Some barriers to adherence women have cited are responsibilities as a caretaker and confusion in the media.14 Unfortunately, decreased awareness is also pervasive among physicians. Intermediate‐risk women were more likely to be assessed as lower risk by primary care physicians, obstetricians/gynecologists, and cardiologists than men with identical risk profiles.40 Therefore, a focus on education of patients and physicians on primary prevention in women is necessary to decrease the persistently large global burden of ASCVD. Furthermore, additional women‐specific clinical research is needed, as the majority of ASCVD trials have been in men. Updated guidelines on prevention of CV diseases in women are needed to assist with accurate clinical decisions and to optimize ASCVD prevention in half of the world's population.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Lee S K, Khambhati J, Varghese T et al. Comprehensive primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:832–838. 10.1002/clc.22767

REFERENCES

- 1. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:399‐410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Effectiveness‐based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women—2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:1243–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA. Cardiovascular health after maternal placental syndromes (CHAMPS): population‐based retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005;366:1797–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre‐eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2007;335:974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fraser A, Nelson SM, Macdonald‐Wallis C, et al. Associations of pregnancy complications with calculated cardiovascular disease risk and cardiovascular risk factors in middle age: the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Circulation. 2012;125:1367–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shah BR, Retnakaran R, Booth GL. Increased risk of cardiovascular disease in young women following gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1668–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lidegaard O, Lokkegaard E, Jensen A, Skovlund CW, Keiding N. Thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2257–2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shufelt CL, Bairey Merz CN. Contraceptive hormone use and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:221–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Investigators WHI. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280:605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Manzi S, Meilahn EN, Rairie JE, et al. Age‐specific incidence rates of myocardial infarction and angina in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with the Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shiroma EJ, Lee IM. Physical activity and cardiovascular health: lessons learned from epidemiological studies across age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Circulation. 2010;122:743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mosca L, Mochari‐Greenberger H, Dolor RJ, Newby LK, Robb KJ. Twelve‐year follow‐up of American women's awareness of cardiovascular disease risk and barriers to heart health. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huxley RR, Woodward M. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of prospective cohort studies. Lancet. 2011;378:1297–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Franco OH, Steyerberg EW, Hu FB, Mackenbach J, Nusselder W. Associations of diabetes mellitus with total life expectancy and life expectancy with and without cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1145–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levitzky YS, Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, et al. Impact of impaired fasting glucose on cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wexler DJ, Grant RW, Meigs JB, Nathan DM, Cagliero E. Sex disparities in treatment of cardiac risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keyhani S, Scobie JV, Hebert PL, McLaughlin MA. Gender disparities in blood pressure control and cardiovascular care in a national sample of ambulatory care visits. Hypertension. 2008;51:1149–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ye S, Muntner P, Shimbo D, et al. Behavioral mechanisms, elevated depressive symptoms, and the risk for myocardial infarction or death in individuals with coronary heart disease: the REGARDS (Reason for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:622–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case‐control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shah AJ, Ghasemzadeh N, Zaragoza‐Macias E, et al. Sex and age differences in the association of depression with obstructive coronary artery disease and adverse cardiovascular events. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization . Global status report on noncommunicable diseases: a priority for women's health and development. http://www.who.int/pmnch/topics/maternal/2011_women_ncd_report.pdf.pdf.

- 24. Shaw LJ, Merz CN, Bittner V, et al. Importance of socioeconomic status as a predictor of cardiovascular outcome and costs of care in women with suspected myocardial ischemia. Results from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute‐sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). J Womens Health 2008;17:1081–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report on the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2935–2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mora S, Glynn RJ, Hsia J, MacFadyen JG, Genest J, Ridker PM. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in women with elevated high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein or dyslipidemia: results from the Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER) and meta‐analysis of women from primary prevention trials. Circulation. 2010;121:1069–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. DeFilippis AP, Blaha MJ, Ndumele CE, et al. The association of Framingham and Reynolds risk scores with incidence and progression of coronary artery calcification in MESA (Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2076–2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lakoski SG, Greenland P, Wong ND, et al. Coronary artery calcium scores and risk for cardiovascular events in women classified as “low risk” based on Framingham Risk Score: the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2347–2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013. AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2960–2984. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30. Midence L, Arthur HM, Oh P, Stewart DE, Grace SL. Women's health behaviours and psychosocial well‐being by cardiac rehabilitation program model: a randomized controlled trial. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:956–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ridker PM1, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. A randomized trial of low‐dose aspirin in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1293–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. Effects of intensive blood‐pressure lowering and low‐dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet. 1998;351:1755–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sharrett AR, Ballantyne CM, Coady SA, et al. Coronary heart disease prediction from lipoprotein cholesterol levels, triglycerides, lipoprotein(a), apolipoproteins A‐I and B, and HDL density subfractions: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation. 2001;104:1108–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Walsh JM, Pignone M. Drug treatment of hyperlipidemia in women. JAMA. 2004;291:2243–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C‐reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2195–2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hsue PY, Bittner VA, Betteridge J, et al. Impact of female sex on lipid lowering, clinical outcomes, and adverse effects in atorvastatin trials. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2889–2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cheng EY, Kong MH. Gender differences of thromboembolic events in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:1021–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor‐based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mosca L, Linfante AH, Benjamin EJ, et al. National study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines. Circulation. 2005;111:499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]