Abstract

Background

Prolonged QT corrected (QTc) intervals are associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes both in healthy and high‐risk populations. Our objective was to evaluate the QTc intervals during a takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) episodes and their potential prognostic role.

Hypothesis

Dynamic changes of QTc interval during hospitalization for TTC could be associated with outcome at follow‐up.

Methods

Fifty‐two consecutive patients hospitalized for TTC were enrolled. Twelve‐lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed within 3 h after admission and repeated after 3, 5, and 7 days. Patients were classified in 2 groups: group 1 presented the maximal QTc interval length at admission and group 2 developed maximal QTc interval length after admission.

Results

Mean admission QTc interval was 493 ± 71 ms and mean QTc peak interval was 550 ± 76 ms (P < 0.001). Seventeen (33%) patients were included in group 1 and 35 (67%) patients in group 2. There were no differences for cardiovascular risk factors and in terms of ECG findings such as ST elevation, ST depression, and inverted T waves. Rates of adverse events during hospitalization among patients of group 1 and 2 were different although not significantly (20% vs 6%, P = 0.22). After 647 days follow‐up, patients of group 1 presented higher risk of cardiovascular rehospitalization (31% vs 6%, P = 0.013; log‐rank, P < 0.01). At multivariate analysis, including age and gender, a prolonged QTc interval at admission was significantly associated with higher risk of rehospitalization at follow‐up (hazard ratio: 1.07 every 10 ms, 95% confidence interval: 1.003‐1.14, P = 0.04).

Conclusions

Prolonged QTc intervals at admission during a TTC episode could be associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular rehospitalization at follow‐up. Dynamic increase of QTc intervals after admission are characterized by a trend toward a better prognosis.

Keywords: Follow‐up, Prolonged QT, QT interval, Stress Cardiomyopathy, Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy

1. INTRODUCTION

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) is an acute and reversible form of heart failure,1 which can mimic an acute myocardial infarction. Its pathophysiology is not still well elucidated; yet, increased catecholamine levels have been proposed as one of the main driving mechanisms.2, 3 TTC is featured by a high rate of in‐hospital complications4 and by an annual rate of 9.9% of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events at long‐term follow‐up.5 Therefore, a prompt prognostic evaluation is crucial in these patients.

During TTC episodes, different electrocardiographic patterns, including ST elevation, prolonged QT corrected (QTc) interval, and deep negative T waves have been reported.6 Several algorithms based on the use of electrocardiogram have been proposed for the diagnosis of TTC, but no study has evaluated the prognostic role of QTc interval dynamic changes among patients admitted for TTC.

The aim of the study was therefore to evaluate QTc interval changes during a TTC episode and their potential prognostic role during hospitalization and at follow‐up.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

We prospectively evaluated 52 consecutive patients with a diagnosis of TTC from January 2012 to December 2014 at the Department of Cardiology, University Hospital of Foggia, Foggia, Italy. After a careful examination of electrocardiogram (ECG) recordings at the end of the hospital stay, patients were divided in 2 groups according to QTc interval measurement. Included in group 1 were those patients who presented maximal QTc interval length at admission, and in group 2 were those who developed maximal QTc interval length during hospitalization.

2.2. Inclusion criteria

The diagnosis of TTC was based on Mayo Clinic criteria7: (1) transient hypokinesis, akinesis, or dyskinesis of the left ventricular (LV) mid segments, with or without apical involvement; the regional wall‐motion abnormalities extend beyond a single epicardial vascular distribution; a stressful trigger is often, but not always, present; (2) absence of obstructive coronary disease or angiographic evidence of acute plaque rupture; (3) new electrocardiographic abnormalities, either ST‐segment elevation and/or T‐wave inversion, or modest elevation in cardiac troponin; (4) absence of pheochromocytoma and myocarditis. The diagnosis of pheochromocytoma was performed under endocrinological evaluation, including blood and imaging test, whereas myocarditis was excluded through cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

2.3. Exclusion criteria

Patients who were taking antiarrhythmic medications or medications that might prolong the QT interval were excluded from the study. Patients with time lags between hospitalization and ECG recording >3 h and time between with symptoms onset and ECG recording >6 h were also excluded from the study.

2.4. Clinical and echocardiographic examination

All patients underwent a clinical examination; a 2‐dimensional Doppler echocardiographic examination on the day of admission, on the third day, and at discharge was performed.

2.5. Blood sample collection

Circulating levels of N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP), high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (CRP), and troponin I were obtained on admission, on the third day during hospitalization, and at discharge. The upper limit of normal for apparently healthy persons (95th percentile) was 125 pg/mL for NT‐proBNP. Normal values were <0.5 ng/mL for troponin‐I, and <5 mg/L for CRP.

2.6. Electrocardiogram analysis

Standard 12‐lead ECGs were serially recorded within 3 h after admission and then repeated after 3, 5, and 7 days. The QT and RR interval were measured in 3 consecutive beats and then averaged. Hard copies of the ECG were analyzed simultaneously by 2 investigators blinded to the patient's data.

QT interval was measured with electronic calipers, from the onset of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave. This value was adjusted by gender, heart rate, and QRS duration as per the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation/Heart Rhythm Society recommendations.8 For our analysis, we used the ECG lead with the longest QT interval in which a prominent U wave was absent.

QT dispersion was calculated as the difference between maximal and minimal QTc intervals between the different leads of the surface 12‐lead ECG.

2.7. Follow‐up and definition of outcome

Mean follow‐up was 647 ± 497 days. Complete follow‐up data were available in all 52 patients with a follow‐up of at least 3 months from study inclusion. Clinical end points included in‐hospital complications (cardiogenic shock, pulmonary edema, stroke) and rehospitalization for TTC recurrence, heart failure, or cardiac arrhythmias.

All patients gave a written informed consent. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Continuous variable were reported as means ± standard deviation and compared with the Student t test for either paired or unpaired groups as required, dichotomic variables as percentage, and compared with the χ2 test or Fisher test as required. Repeated measures were analyzed with analysis of variance (ANOVA). Survival rate was reported on a Kaplan–Meier plot and analyzed with a log‐rank test and multiple stepwise Cox analysis. Hazard ratio with 95% confidence interval was therefore calculated. A P value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients' characteristics

Fifty patients were female (96%), and the mean age was 73 ± 14 years. The left ventricular ejection fraction at diagnosis was 33% ± 8% and at discharge was 50% ± 7% (P < 0.001). The mean QTc interval at admission was 493 ± 71 ms, and the mean maximal QTc interval throughout hospital stay was 548 ± 77 ms (P < 0.001).

3.2. QT changes during hospitalization

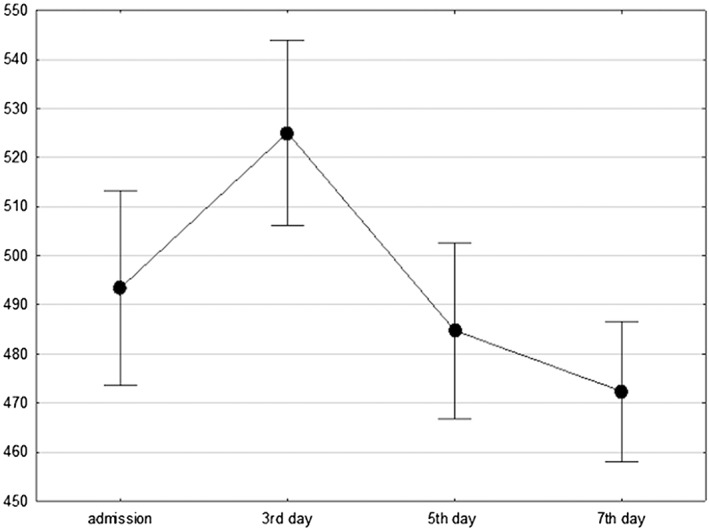

As shown in Figure 1, patients with admission diagnosis of TTC presented increased values of QTc intervals 493 ± 71 ms. During the third day of hospitalization, QTc interval reached its peak (mean values 525 ± 67 ms), than slightly decreased during the fifth (485 ± 63 ms) and the seventh day of hospitalization (472 ± 43 ms) (ANOVA, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

QTc interval changes during TTC hospitalization in the population's study (analysis of variance, P < 0.001). QTc = QT corrected

3.3. QTc interval dynamic changes

Seventeen (33%) patients were included in group 1 and 35 (67%) patients in group 2; patients did not differ in terms of age, gender, and cardiovascular risk factors (Table 1). Although not statistically significant, a trend of higher prevalence of noncardiovascular comorbidities was present in group 1 (history of neurological disorders 31% vs 6%, P = 0.53; and respiratory diseases 35% vs 8%, P = 0.52). There were no differences in terms of ECG findings for ST elevation, ST depression, and inverted T waves, but there was a difference for QT dispersion at admission (87 ± 46 ms in group 1 vs 51 ± 21 ms in group 2, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical features and electrocardiographic finding during hospitalization in group 1 (patients with maximal QTc interval length at admission) and group 2 (patients with maximal QTc interval length after admission)

| Group 1 | Group 2 | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| no. of patients | 17 | 35 | |||

| Age, y | 74 | ±17 | 70 | ±13 | 0.34 |

| Male | 6% | 3% | 0.60 | ||

| CV risk factors | |||||

| Hypertension | 76% | 77% | 0.87 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 53% | 40% | 0.51 | ||

| Obesity | 24% | 11% | 0.50 | ||

| Smoker | 18% | 11% | 0.49 | ||

| Diabetes | 41% | 23% | 0.28 | ||

| Clinical presentation | |||||

| No chest pain | 53% | 31% | 0.44 | ||

| Angina | 35% | 51% | 0.28 | ||

| Atypical chest pain | 24% | 11% | 0.23 | ||

| Dyspnea | 35% | 31% | 0.78 | ||

| Precipitating stressor | |||||

| Emotional stressors | 35% | 25% | 0.35 | ||

| Physical stressors | 35% | 51% | 0.28 | ||

| No stressors | 29% | 26% | 0.78 | ||

| Laboratory and echocardiogram findings | |||||

| Admission EF% | 31 | ±7 | 35% | ±8 | 0.13 |

| NT‐proBNP admission (pg/mL) | 11 877 | ±8305 | 11 896 | ±10 613 | 0.99 |

| Troponin I peak (ng/mL) | 2.74 | ±2.3 | 4.1 | ±8.1 | 0.5 |

| CRP peak (mg/L) | 48 | ±63 | 54 | ±82 | 0.45 |

| Discharge EF% | 48% | ±8 | 51% | ±5 | 0.22 |

| ECG findings | |||||

| Admission QTC interval (ms) | 549 | ±88 | 466 | ±40 | 0.01 |

| QT dispersion at admission (ms) | 87 | ±46 | 51 | ±21 | 0.01 |

| 3rd‐day QTC interval (ms) | 493 | ±57 | 539 | ±67 | 0.02 |

| 5th‐day QTc interval (ms) | 462 | ±65 | 495 | ±52 | 0.09 |

| 7th‐day QTC interval (ms) | 460 | ±41 | 476 | ±44 | 0.35 |

| ST elevation at admission | 59% | 46% | 0.38 | ||

| Inverted T waves at admission | 53% | 49% | 0.77 | ||

| ST depression at admission | 0 | 0 | — | ||

| ST elevation day 3 | 31% | 14% | 0.51 | ||

| Inverted T waves day 3 | 87% | 94% | 0.41 | ||

| ST depression day 3 | 0 | 11% | 0.16 | ||

Abbreviations: CRP, C‐reactive protein; CV, cardiovascular; ECG, electrocardiogram; EF, ejection fraction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; QTc, QT corrected; SD, standard deviation.

Ventricular arrhythmias, including premature ventricular contractions, sustained and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, and torsade de pointes were equally distributed between the 2 groups at admission, after 72 h, and at discharge.

Furthermore, patients in group 1 showed higher, although not significantly given the small population of patients enrolled, rates of adverse events during hospitalization (20% vs 6%, P = 0.22) and similar hospitalization duration (8 ± 3 vs 9 ± 3 days, P = 0.6).

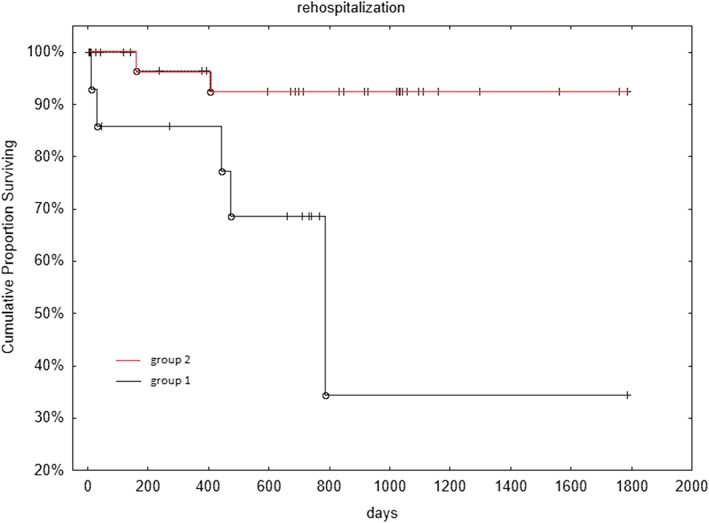

After a mean follow‐up of 647 days, 7 patients experienced rehospitalization for cardiovascular events; patients of group 1 had a higher incidence of rehospitalizations (31% vs 6%, P = 0.013). Kaplan–Meier estimates for survival free from adverse events curves were significantly different between group 1 and 2 (log‐rank, P < 0.01) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival free from cardiovascular rehospitalization: group 1 (patients with maximal QTc interval length at admission) vs group 2 (patients with maximal QTc interval length after admission) (log‐rank P < 0.01). QTc = QT corrected

Admission QTc levels, however, were significant predictors of rehospitalization at follow‐up, even after correction for age and gender at multivariable analysis (hazard ratio: 1.07 every 10 ms, 95% confidence interval: 1.003‐1.14, P = 0.04). Peak QTc levels during hospitalization were not related to outcomes at follow‐up.

4. DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluated the prognostic role of QTc intervals dynamic changes during hospitalization for a TTC episode. We found that patients with prolonged QTc intervals at admission have a higher risk of cardiovascular rehospitalization at follow‐up and those with dynamic increase of QTc intervals after admission are characterized by a trend toward a better prognosis.

TTC has been long considered a benign disease because of the completely reversible nature of the distinct wall motion abnormalities. However, several clinical studies have clearly established that TTC is a serious form of acute heart failure that can be associated with life‐threatening complications.9 Mortality rates similar or even higher than in myocardial infarction10 point to the need for comprehensive risk assessment including clinical and ECG features.

4.1. Physiological basis of QT interval

QT interval represents the total duration of electrical activity of the ventricles, from the beginning of depolarization to the end of repolarization. It is strongly related with central nervous system interactions; sympathetic stimulation can secondarily decrease the QT interval, whereas parasympathetic stimulation, by decreasing heart rate, can increase the QT interval.11

Elevated catecholamine levels in healthy subjects typically result in QT interval prolongation through a combination of α1‐ and β‐adrenergic effects. α1‐adrenergic stimulation reduces the amplitude of the transient outward and other K+ currents; meanwhile, β‐adrenergic stimulation promotes cellular calcium influx.12

4.2. QT interval and cardiovascular events

QT interval prolongation has been associated with sudden death and cardiovascular mortality in high‐risk individuals with hypertension, diabetes, or following myocardial infarction.13 However, also in a healthy population, a higher risk of incident cardiovascular events has been associated with prolonged QTc interval.14

4.3. ECG changes and QTc in TTC

ECG changes during the acute phase of TTC have been previously described. Initially after symptom onset, ST‐segment elevation can be observed, followed by deep T‐wave inversion with partial resolution of ST‐segment elevation (after 48–72 h). During the subacute period of TTC, a transient improvement in T‐wave inversion can be found, and later on a second deeper T‐wave inversion, which may resolve early or persist for a long time.15

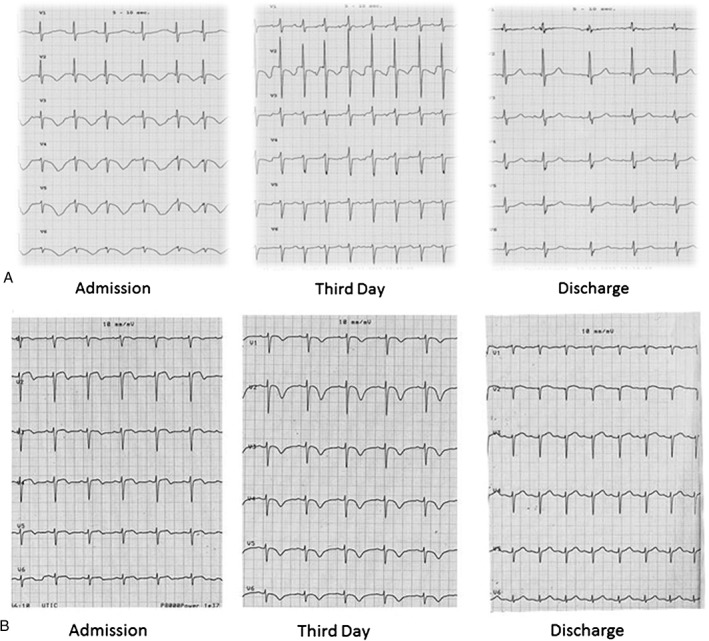

QTc prolonged interval is a relatively common electrocardiographic finding in TTC. QTc dynamic changes during a TTC episode have been described in several articles,16, 17 and are in line with our data (Figure 3A,B). Patients with TTC present mainly with a slight prolonged QTc at admission, which reaches its peak during the third day of hospitalization and slowly decreases with partial normalization.

Figure 3.

(A) ECG presentation in a patient of group 1, which presented with a prolonged QTc interval and diffuse negative T waves on admission, slight reduction of QTc interval on the third day of hospitalization, and complete normalization at discharge. (B) ECG presentation in a patient in group 2, who presented with a slight prolonged QTc interval on admission, longer QTc interval associated with diffuse deep negative T waves on third day of hospitalization, and complete normalization at discharge. Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; QTc = QT corrected

However, the mechanism leading to QTc interval prolongation in TTC is still unclear. In 20 patients with a mean age of 65 years who experienced TTC mainly for an emotional stressor and received MRI during their third day of hospitalization, Perazzolo Marra et al. hypothesized that QT prolongation could reflect the edema induced in the apical segments and the dispersion of repolarization between apical and basal LV regions.18

In a study by Dib et al.,19 109 patients with TTC were divided into 3 groups according to admission ECG: ST‐segment elevation or new left bundle branch block, T‐wave inversion, and nonspecific ST‐T abnormalities or normal ECG. Authors found that in the hospital, long‐term mortality was not different between the groups and concluded that the ECG in patients with TTC does not provide significant prognostic information.

However, some recent studies found that admission QTc interval has a prognostic role in TTC,20 and in a European position statement, admission QT interval > 500 ms was considered one of the minor risk factor for adverse events.21

Pickham et al. found, among patients admitted in the intensive care unit, that prolonged QT interval has a high prevalence (24%). Predictors of QT prolongation were being female, on QT‐prolonging drugs, electrolyte imbalance, history of stroking, and hypothyroidism. Patients with QT prolongation had longer hospitalization and 3 times the odds for all‐cause in‐hospital mortality compared to patients without QT prolongation.22

In our study, when comparing patients who developed maximal length of QTc interval at admission (group 1) and after admission (group 2), differences were not significant in terms of ECG finding on ST elevation, ST depression, and inverted T waves, but only in terms of QT dispersion at admission.

Patients with prolonged QT at admission presented higher QT dispersion, a parameter that is a predictor of events especially in patients with cerebrovascular disease.23 These data reinforce the concept that although TTC is a cardiomyopathy, the interaction between heart and sympathetic nervous system may play an important role.

We found that patients with dynamic increase QTc interval after admission are characterized by a trend toward a better prognosis. These data could be in line with some findings during acute myocardial infarction. Obayashi et al.,24 evaluated 34 patients with anterior myocardial infarction who underwent single‐photon emission computed tomography imaging 3 to 5 days after the onset of acute myocardial infarction. They found that when QTc interval prolongation appears transiently and reaches its peak after 36 h, it indicates scintigraphically the presence of salvaged myocardium.

Moreover, myocardial edema during the third day of hospitalization for a TTC episode, detected through MRI, has a prevalence of 82%.25 Migliore et al. found that isolated myocardial edema observed in TTC patients with T‐wave inversion/QTc prolongation predicts reversible LV dysfunction and benign long‐term outcome.26

In our study, dynamic changes of QTc intervals in TTC could be associated with 2 different pathogenic mechanisms. Prolonged admission QTc interval could reflect comorbidities of the patients that are well known prognostic risk factors in TTC27 and increased sympathetic activity. Underlying comorbid conditions may be associated with higher circulating levels of catecholamine that could result in a prolonged QTc interval. Moreover, in the present study, higher rates of subjects with comorbidities, although not statistically significant, were present in the group 1, thus suggesting a possible link between such conditions and an early QT peak. By the opposite transient QTc interval increasing during hospitalization could reflect the development of myocardial edema and stunning that could be associated with a better outcome. Therefore, patients with prolonged QTc interval at admission should be followed up more closely to avoid the risk of cardiovascular rehospitalization.

4.4. Limitations

These are preliminary results needing to be confirmed in larger cohorts of patients. Several differences are not statistically significant because of the small number of patients enrolled. Given the observed differences in event rates, 2 groups of 90 subjects would be adequately powered to detect significant differences. Further and more adequately powered prospective studies are warranted to clarify the assay standardization, the optimal cutoff, and the prognostic value of QTc interval.

5. CONCLUSION

Prolonged QTc interval at admission during a TTC episode could be associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular rehospitalization at follow‐up. Dynamic increase of QTc intervals after admission is characterized by a trend toward a better prognosis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Santoro F, Brunetti ND, Tarantino N, et al. Dynamic changes of QTc interval and prognostic significance in takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:1116–1122. 10.1002/clc.22798

REFERENCES

- 1. Elliott P, Andersson B, Arbustini E, et al. Classification of the cardiomyopathies: a position statement from the European Society Of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Santoro F, Tarantino N, Ferraretti A, et al. Serum interleukin 6 and 10 levels in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: increased admission levels may predict adverse events at follow‐up. Atherosclerosis. 2016:254;28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schneider B, Athanasiadis A, Schwab J, et al. Complications in the clinical course of tako‐tsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Santoro F, Ieva R, Ferraretti A, et al. Diffuse ST‐elevation following J‐wave presentation as an uncommon electrocardiogram pattern of Tako‐Tsubo cardiomyopathy. Heart Lung. 2013;42:375–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (Tako‐ Tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): a mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2008;155:408–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rautaharju PM, Surawicz B, Gettes LS, et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part IV: the ST segment, T and U waves, and the QT interval. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:982–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Madhavan M, Rihal CS, Lerman A, Prasad A. Acute heart failure in apical ballooning syndrome (TakoTsubo/stress cardiomyopathy): clinical correlates and Mayo Clinic risk score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1400–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stiermaier T, Moeller C, Oehler K, et al. Long‐term excess mortality in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: predictors, causes and clinical consequences. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Samuels MA. The brain–heart connection. Circulation. 2007;116:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hartzell HC, Mery PF, Fischmeister R, Szabo G. Sympathetic regulation of cardiac calcium current is due exclusively to cAMP‐dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1991;351:573–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Straus SM, Kors JA, De Bruin ML, et al. Prolonged QTc interval and risk of sudden cardiac death in a population of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beinart R, Zhang Y, Lima JA, et al. The QT interval is associated with incident cardiovascular events: the MESA study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2111–2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thakar S, Chandra P, Hollander G, Lichstein E. Electrocardiographic changes in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2011;34:1278–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rotondi F, Manganelli F. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and arrhythmic risk: the dark side of the moon. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kurisu S, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, et al. Time course of electrocardiographic changes in patients with tako tsubo syndrome: comparison with acute myocardial infarction with minimal enzymatic release. Circ J. 2004;68:77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perazzolo Marra M, Zorzi A, Corbetti F, et al. Apicobasal gradient of left ventricular myocardial edema underlies transient T‐wave inversion and QT interval prolongation (Wellens' ECG pattern) in Tako‐Tsubo cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dib C, Asirvatham S, Elesber A, et al. Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of electrocardiographic abnormalities in apical ballooning syndrome. Am Heart J. 2009;157:933–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Imran TF, Rahman I, Dikdan S, et al. QT prolongation and clinical outcomes in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2016;39:607–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lyon AR, Bossone E, Schneider B, et al. Current state of knowledge on Takotsubo syndrome: a position statement from the Taskforce on Takotsubo Syndrome of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pickham D, Helfenbein E, Shinn JA, et al. High prevalence of corrected QT interval prolongation in acutely ill patients is associated with mortality: results of the QT in Practice Study. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:394–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lederman YS, Balucani C, Lazar J, et al. Relationship between QT interval dispersion in acute stroke and stroke prognosis: a systematic review. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:2467–2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Obayashi T, Tokunaga T, Iiizumi, T , Shiigai T, Hiroe, M , Marumo F. Transient QT interval prolongation with inverted T waves indicates myocardial salvage on dual radionuclide single‐photon emission computed tomography in acute anterior myocardial infarction. Jpn Circ J. 2001;65:7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eitel I, von Knobelsdorff‐Brenkenhoff F, Bernhardt P, et al. Clinical characteristics and cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings in stress cardiomyopathy. JAMA. 2011;306:277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Migliore F, Zorzi A, Perazzolo Marra M, Iliceto S, Corrado D. Myocardial edema as a substrate of electrocardiographic abnormalities and life‐threatening arrhythmias in reversible ventricular dysfunction of takotsubo cardiomyopathy: imaging evidence, presumed mechanisms and implications for therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1867–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Santoro F, Ferraretti A, Ieva R, et al. Renal impairment and outcome in patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:548–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]