Abstract

Use of recreational drugs is associated with a number of histologic changes. These may be related to the method of administration or due to systemic effects of the drugs. This paper reviews the histopathological features seen following recreational drug use. With injection, there may be local effects from abscess formation and systemic effects may result in amyloidosis. Injections have been associated with necrotizing fasciitis, anthrax, and clostridial infections. Systemic effects include infective endocarditis, with the risk of embolization, and abscesses may be seen in organs in the absence of infective endocarditis. Viral complications of injection include hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Injecting crushed tablets can result in intravascular granulomata in the lungs. Smoking drugs is associated with intraalveolar changes, including blackand brown-pigmented macrophages in crack cocaine and cannabis smoking, respectively. Snorting may result in intraalveolar granulomata forming when crush tablets are used and there may be systemic granulomata. Stimulants are associated with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular pathology, including contraction band necrosis and myocardial fibrosis, as well as coronary artery dissection. Stimulants may cause hyperpyrexia and rhabdomyolysis, which may be associated with changes in multiple organs including myoglobin casts in the kidney. Opioids cause respiratory depression and this can be associated with inhalational pneumonia and hypoxia in other organs if there is resuscitation and a period of survival. Ketamine use has been associated with changes in the urothelium and the liver. This paper reviews histology changes that may be seen in drug-related deaths using illustrative cases.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Drugs, Histology, Pathology, Abuse, Organ

Introduction

Recreational drug abuse is extensive in multiple societies (1) and can have both physiological and psychological effects (2, 3). Substances used vary between different countries and over time, but wherever used, there are often pathologic changes seen in tissues following both acute and chronic use. Pathology associated with recreational drug use may be related to the methods used to administer the substances and also the direct pharmacological effects of the drug (2, 3).

This paper provides a brief review of organ histology associated with drugs of abuse other than ethanol, which has its own distinct pathology (4–5). Drugs typically associated with pathologic changes discussed in this article include use of opiates/opioids; stimulant drugs including cocaine, amphetamine, amphetamine derivatives, and synthetic cathinones; as well as the dissociative anesthetic agent ketamine. Cannabis is briefly discussed. Many drugs are not associated with any specific pathology, particularly opioids, though the respiratory depression associated with opioid overdose may cause pneumonia (see below) and hypoxic brain damage in those resuscitated (3). Other systemic complications include hyperpyrexia that may be induced by drugs, as well as by environmental conditions, and the pathology seen in drug use and environmentally induced hyperpyrexia is similar (6 –9). This review uses case studies to illustrate the possible patterns of histopathology that can be seen with recreational drug use.

Discussion

Organ Histopathology Associated with Routes of Administration

The main routes of administration of recreational drugs are injection, smoking, insufflation (snorting), and oral ingestion. The latter typically leaves no his-topathological features, but the other routes may have local and systemic effects.

Injection

Injection is a common method of administering drugs. The principal complication of injecting drugs is infection, both locally at the site of administration and systemically (10 –12). Injection is typically intravenous, but may be subcutaneous (“popping”) and intraarterial. The main local complications are infection, which may result in abscess formation, phlebitis with occlusion of veins requiring new sites of injection, and rarely other complications including necrotizing fasciitis, anthrax, botulism, and clostridial infections (13 –19). When the groin is injected, sinus tracks may form between the skin and the femoral vein. Local abscess formation may form the nidus for systemic complications including amyloidosis (20, 21).

Systemic effects may occur from the introduction of bacterial infections, the most common being systemic sepsis and infective endocarditis (22 –25). This may be complicated by systemic embolization with the development of mycotic aneurysms. Sepsis with septicemia resulting in abscess formation in distant organs may also rarely occur (see illustrative case). Viral infections, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), are common and there is a high incidence of hepatitis C infection in intravenous drug users (26 –31).

Illustrative Case—Injection with Necrotizing Fasciitis

A 54-year-old man with a history of drug use, hepatitis C, and chronic pain from osteoarthritis presented to the emergency department requesting pain killers. He reported the pain had been so bad he had a friend inject him with a pain killer. He was given opioids, including a fentanyl patch, as well as clindamycin as he had cellulitis at the injection site. He was discharged home but re-presented 17 hours later. He was hypotensive with tachycardia and rapidly went into cardiac arrest. Investigations revealed a white cell count of 3.1 x 109/L with a markedly elevated creatine kinase of 11356 U/L. He could not be resuscitated.

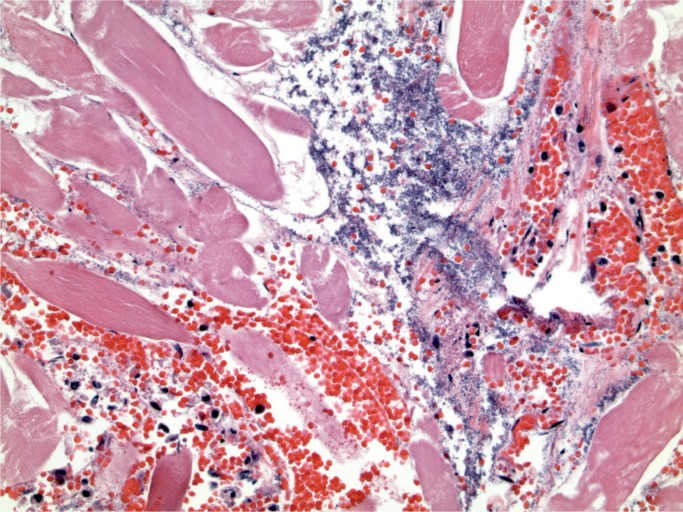

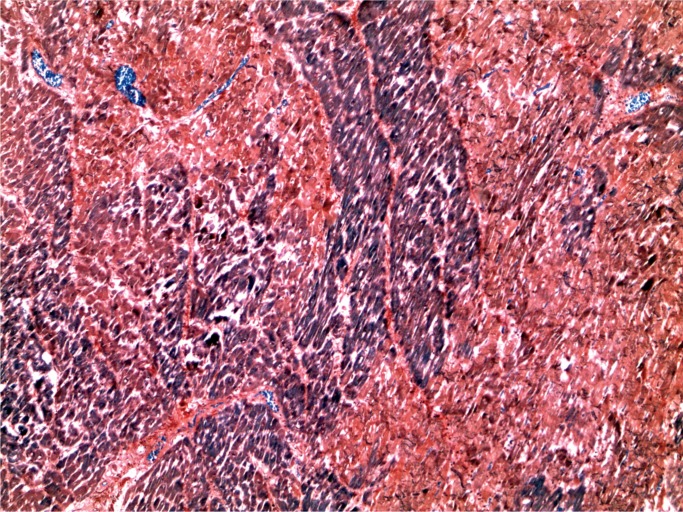

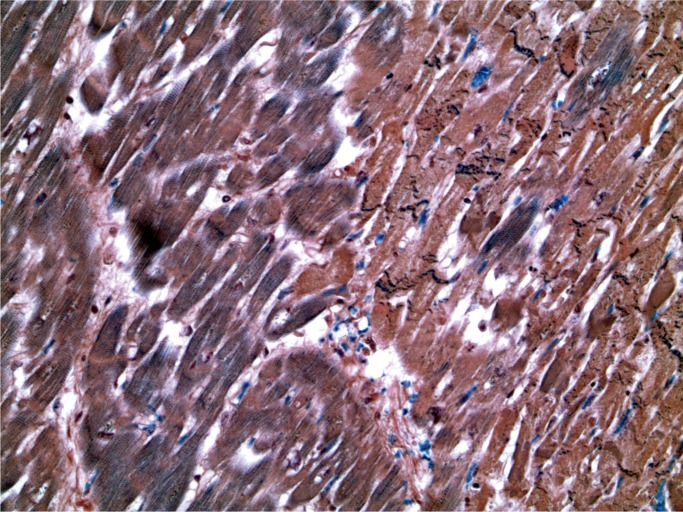

At autopsy, he was noted to have a red, swollen right arm and a culture from the arm grew Group A streptococcus organisms. Histology of the arm revealed necrotizing fasciitis with Gram-positive cocci (Images 1 and 2). Toxicology revealed hydromorphone, oxycodone, cocaine, and quetiapine.

Image 1:

Necrotizing fasciitis (H&E, x200).

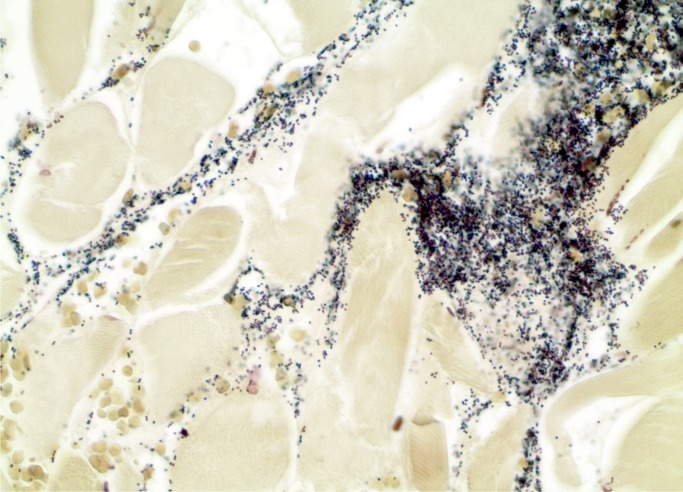

Image 2:

Necrotizing fasciitis. Gram-positive cocci (Gram, x400).

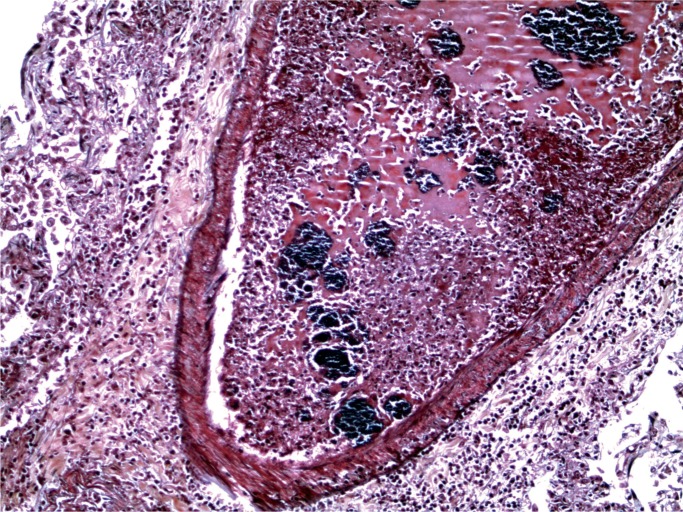

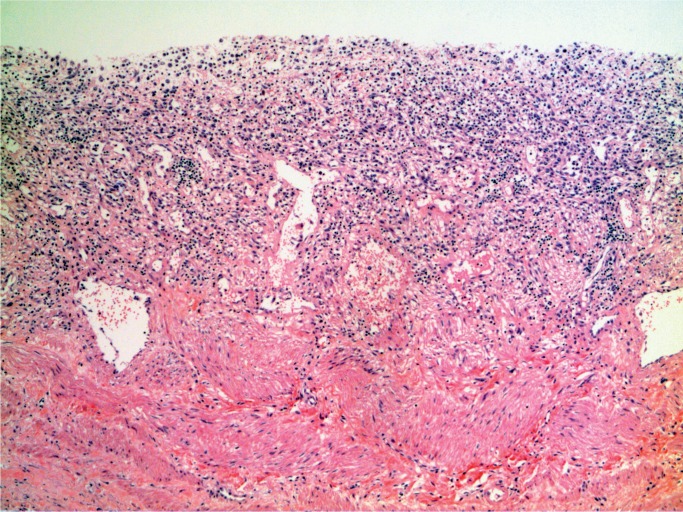

Illustrative Case—Infective Endocarditis

A 52-year-old woman with a history of intravenous drug use was said to have been feeling generally ill, weak, and eating little. She became drowsy and emergency services were called, but she went into cardiac arrest and could not be resuscitated.

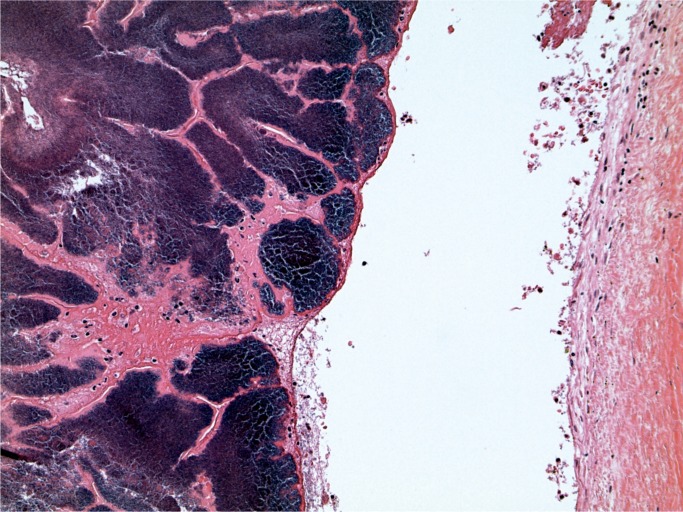

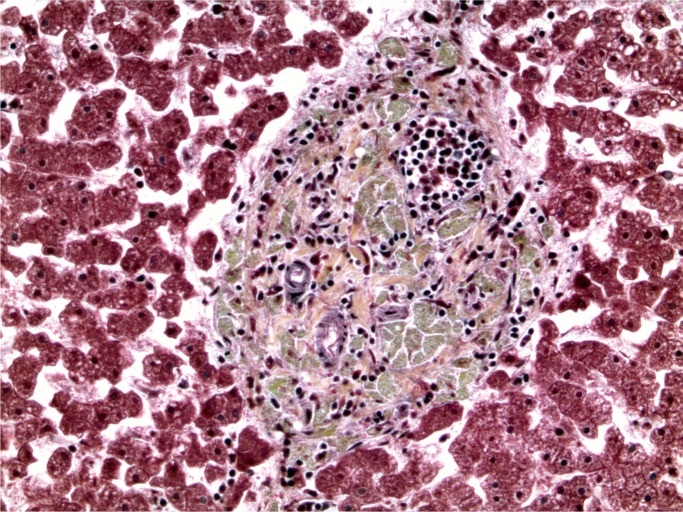

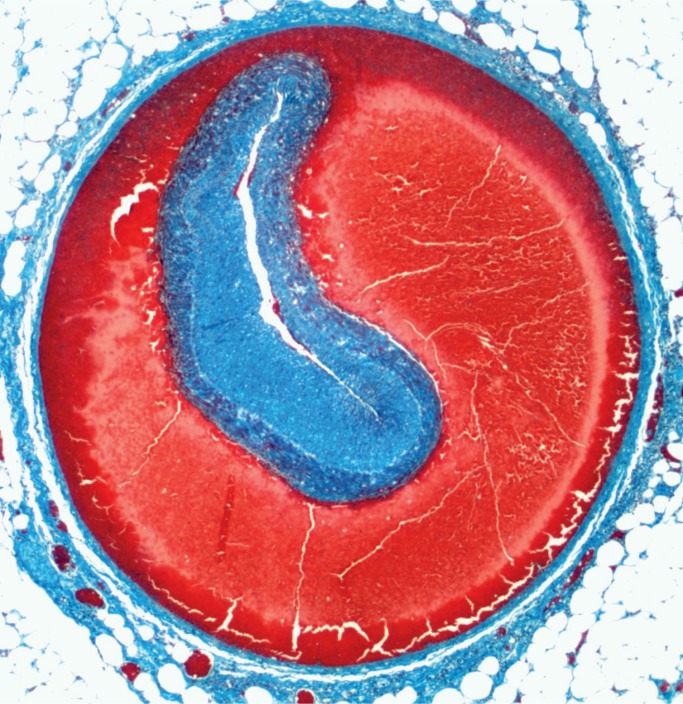

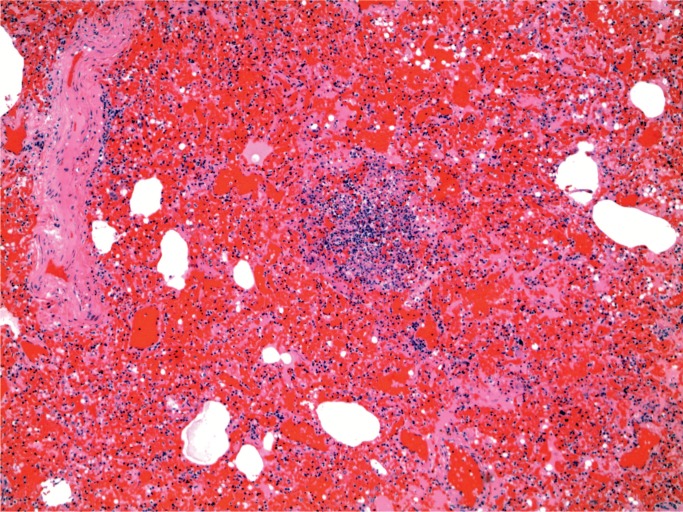

At autopsy, there were multiple injection sites on the forearms with bruising present. Vegetations were on the mitral valve that grew Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus viridians (Images 3 and 4). Septic emboli were in the kidneys (Image 5) and clumps of bacteria in the liver and spleen. In addition to systemic emboli, septic emboli were in the pulmonary circulation, in association with pulmonary infarcts (Images 6 and 7).

Image 3:

Endocarditis vegetation (H&E, x50).

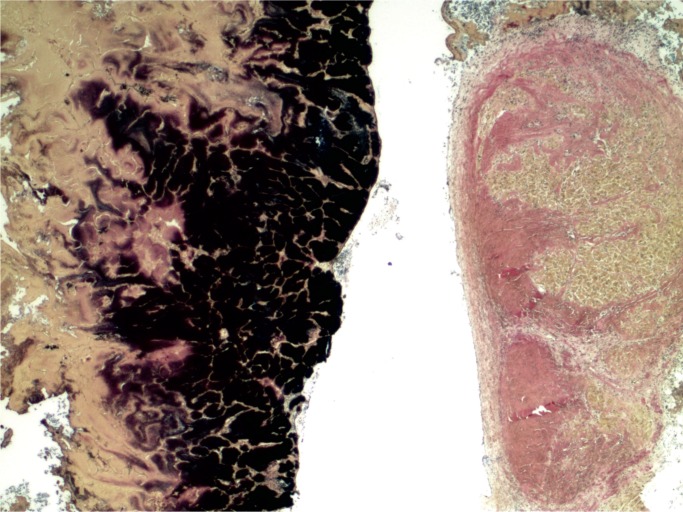

Image 4:

Endocarditis vegetation (Gram, x50).

Image 5:

Kidney with embolic abscess (H&E, x50).

Image 6:

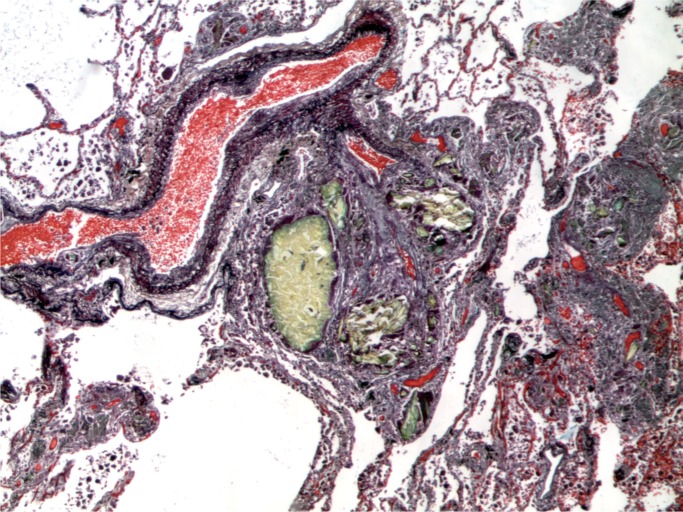

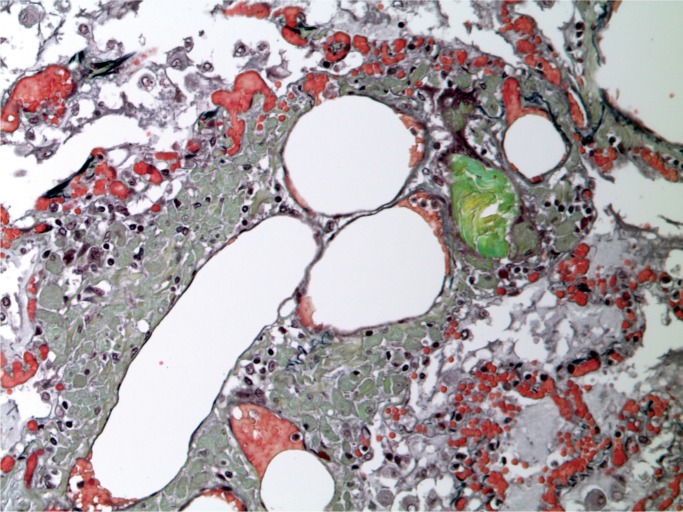

Lung with septic emboli (Movat, x100).

Image 7:

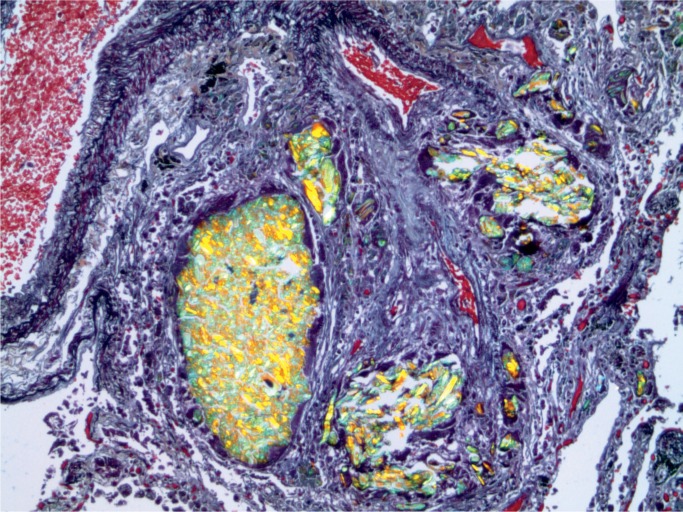

Lung with septic emboli (Gram, x100).

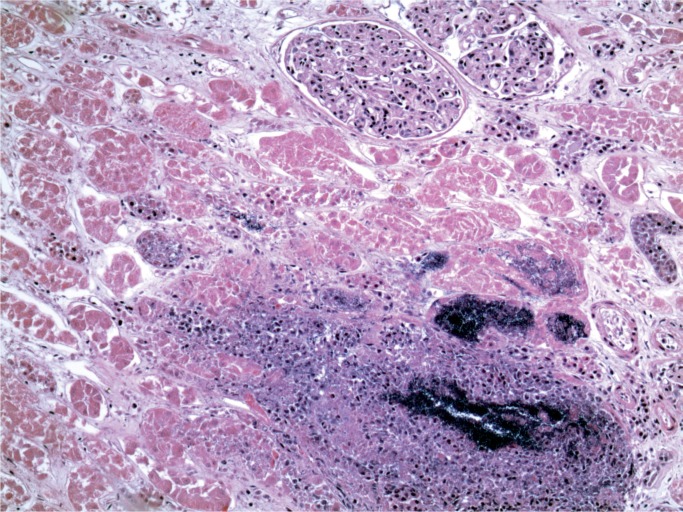

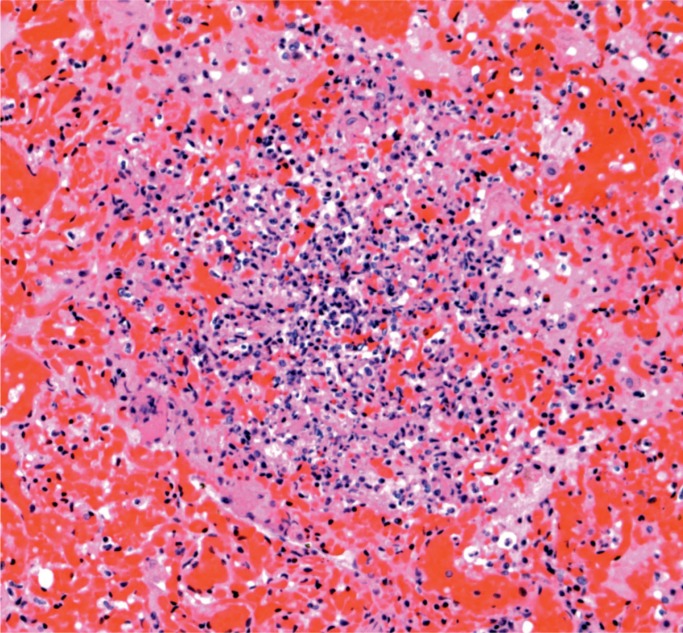

Illustrative Case—Systemic Infection with Cardiac Abscesses

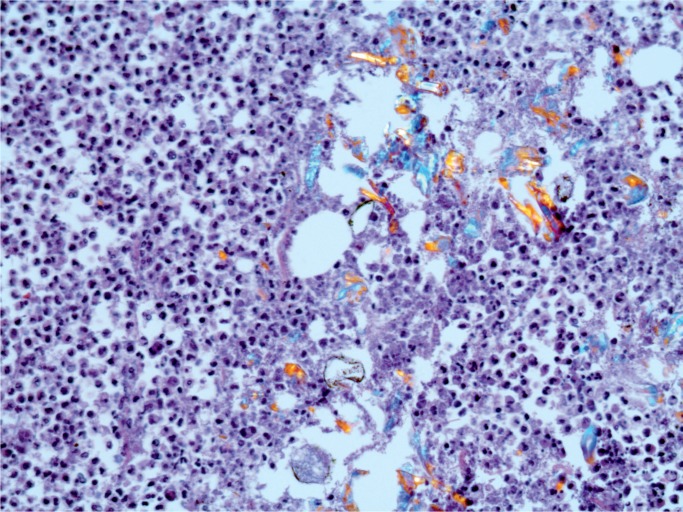

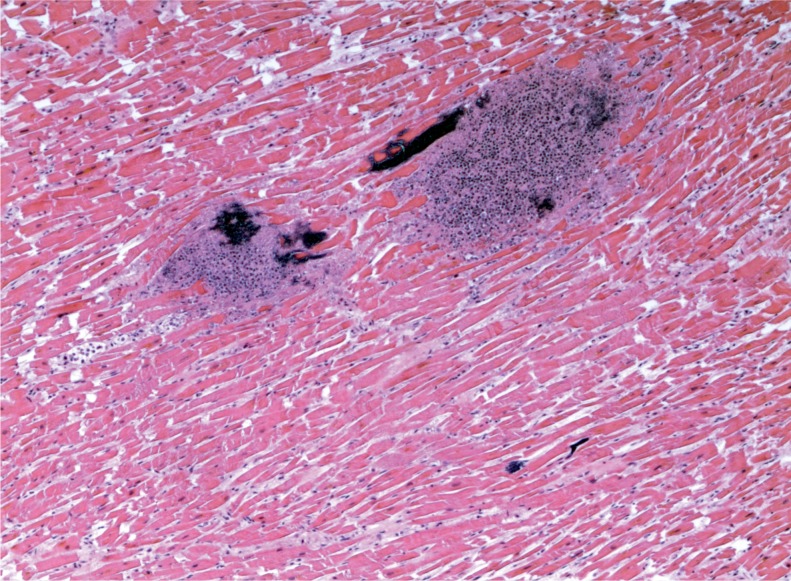

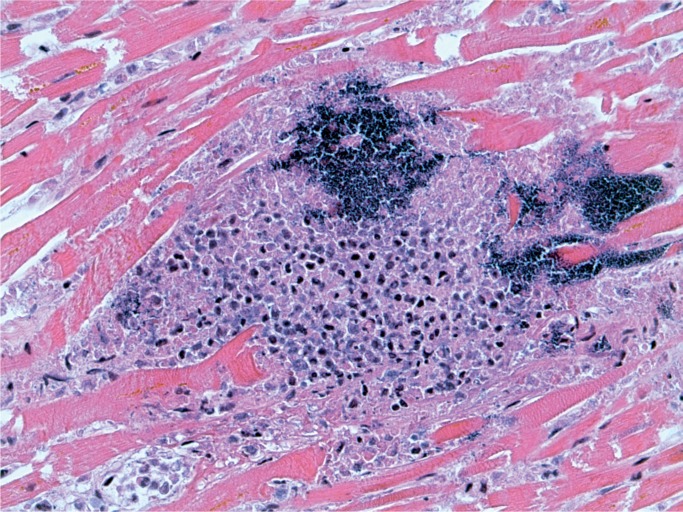

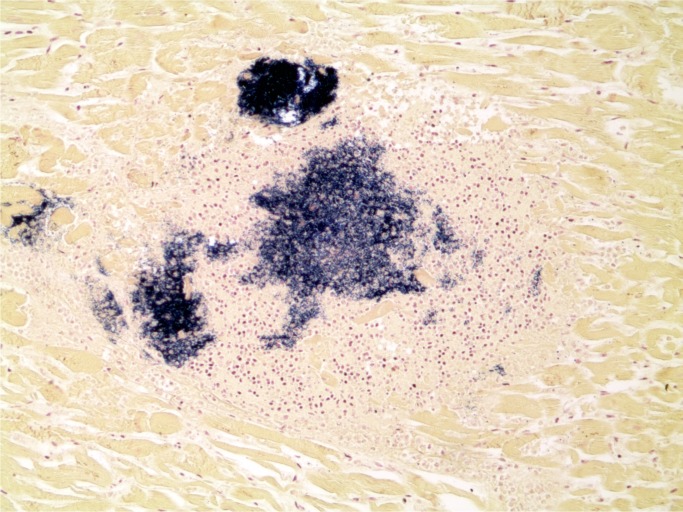

A 44-year-old woman was found with a decreased level of consciousness. She was brought to hospital and diagnosed with fever, tachycardia, and tachypnea. A troponin was elevated at 25.12 µg/L and her white blood cell count was elevated at 16.7 x 109/L with a neutrophil count of 13.86 x 109/L. She was a known drug user with track marks on her legs. A recent echocardiogram did not show any evidence of infective endocarditis and none was seen at autopsy. Histology of an injection site revealed abscess formation and foreign body material (Images 8 and 9). Multiple abscesses were in the myocardium, kidney, and liver (Images 10 to 12).

Image 8:

Skin with abscess at injection site (H&E, x25).

Image 9:

Skin with abscess at injection site with birefringent material (H&E, x200).

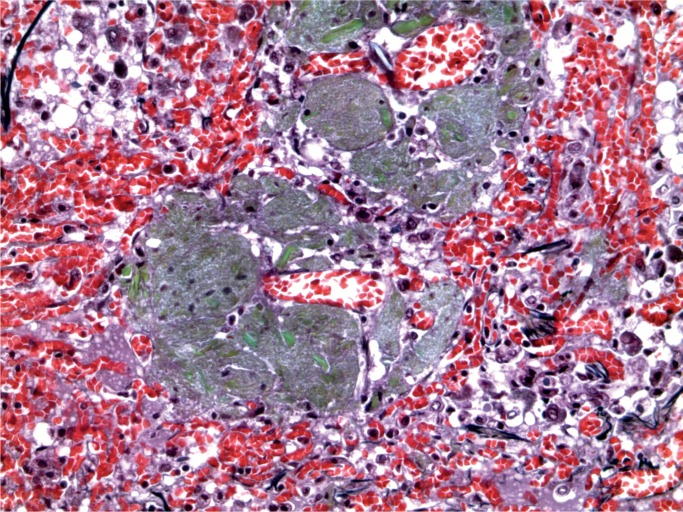

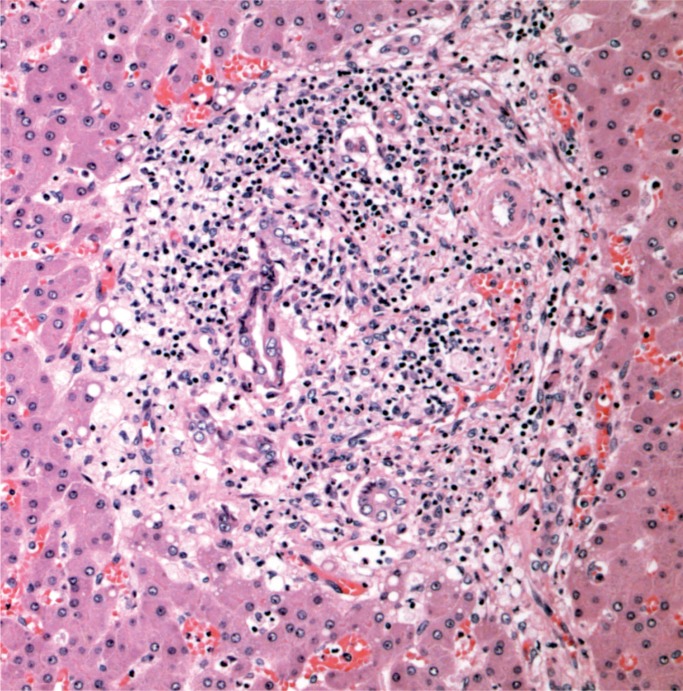

Image 10:

Cardiac abscesses (H&E, x50).

Image 11:

Cardiac abscess (H&E, x200).

Image 12:

Cardiac abscess with Gram-positive cocci (Gram, x100).

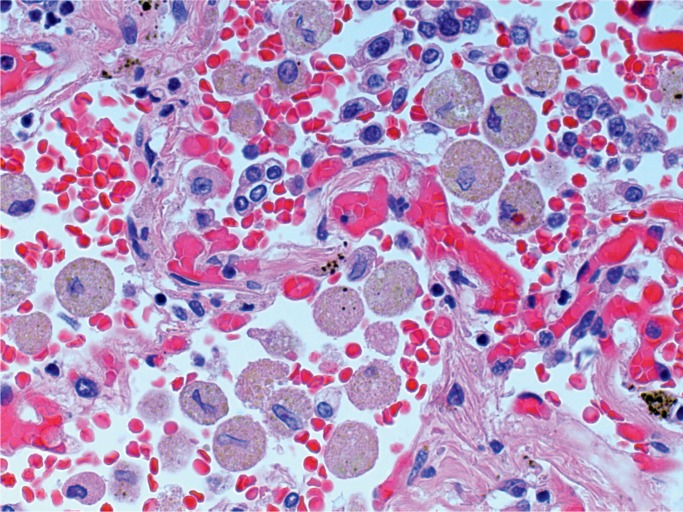

Noninfectious Complications

A noninfectious complication of injection is the development of intravascular granulomata in the lungs (32 –36). This most commonly occurs when tablets are crushed and injected. A particular problem may be encountered when patients have indwelling intravenous catheters, which facilitate the injecting habit. These catheters may be placed because of the need for repeated administration of drugs, such as treating infectious endocarditis with intravenous antibiotics. Tablets are made with bulking agents, also known as excipients. These substances include starch, talc, microcrystalline cellulose, and crospovidone. All but the latter can be seen by polarizing light and a number of stains can be helpful including Movat pentachrome (all but starch), periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) (microcrystalline cellulose and crospovidone), and Congo red (microcrystalline cellulose) (37). When injected in arteries rather than veins, ischemic limbs may result (38–39).

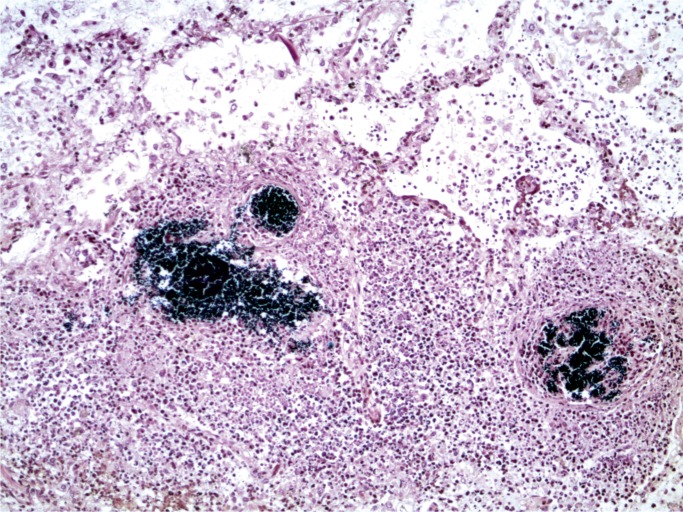

Illustrative Case—Intravascular Granulomata

A 44-year-old woman had been treated in hospital for polymicobial sepsis. She was discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line in place for antibiotic therapy. She had admitted to crushing tablets and injecting them and was later found collapsed at home and could not be resuscitated.

At autopsy, a PICC line was present. Examination of the cut surface of the lungs revealed multiple white nodules 1-2 mm in diameter. Microscopic examination of the lungs revealed multiple foreign body intra-venous granulomata (Images 13 and 14).

Image 13:

Intravascular foreign body granulomata (Movat, x50).

Image 14:

Lung with intravascular foreign body granulomata with polarization (Movat, x100).

Insufflation

Insufflation, also known as snorting, is another common method of self-administration of drugs. Snorting of some drugs may lead to local effects, such as nasal perforation in cocaine use (2, 3). These are often photographed at autopsy but not usually subject to histology. If tablets are crushed and snorted, then a reaction to the tablet material may be seen in the lungs on routine autopsy histology.

Illustrative Case—Insufflation (Snorting)

A 42-year-old man had a history of a psychotic mood disorder and was prescribed olanzapine, citalopram, and clonazepam, but was thought to have run out four days before his death. He was found in the afternoon lying on the floor talking incoherently. He was brought to the ambulance walking with assistance, but suffered cardiac arrest in the ambulance. He was recorded in the ambulance as having a core temperature of 41℃ (105.8℉). Microscopic examination of the lungs revealed intraalveolar and perivascular macrophages with foreign birefringent material, best demonstrated on a Movat stain (Images 15 to 17). In the liver, there were increased neutrophils in the sinusoids with focal hepatocyte necrosis and a predominantly microvesicular fatty change, findings reported in hyperpyrexia (Images 18 and 19). There were also foreign body ganulomata in portal tracts and sinusoids similar to those seen in the lung (Images 20 and 21). Toxicological analysis revealed methylenedi-oxypyrovalerone (MDPV) at a concentration of 5.8 mg/L.

Image 15:

Lung with intraalveolar foreign body granulomata (Movat, x200).

Image 16:

Lung with perivascular foreign body granulomata (H&E, x200).

Image 17:

Lung with perivascular foreign body granulomata (Movat, x200).

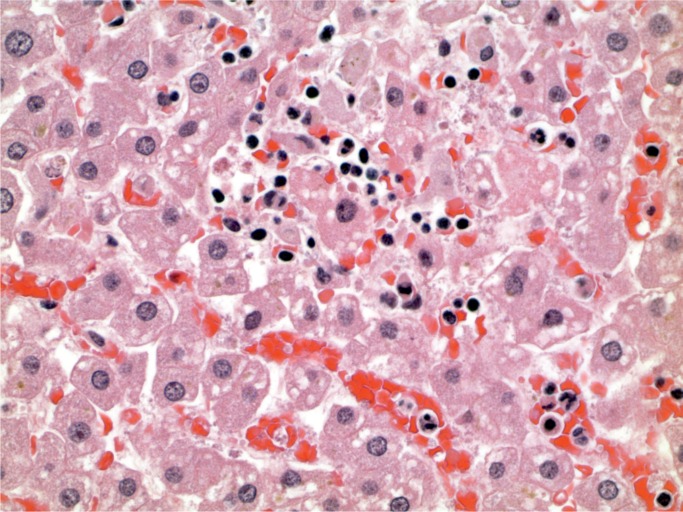

Image 18:

Liver with predominantly microvesicular steatosis (H&E, x400).

Image 19:

Liver with hepatocyte necrosis and neutrophil reaction (H&E, x400).

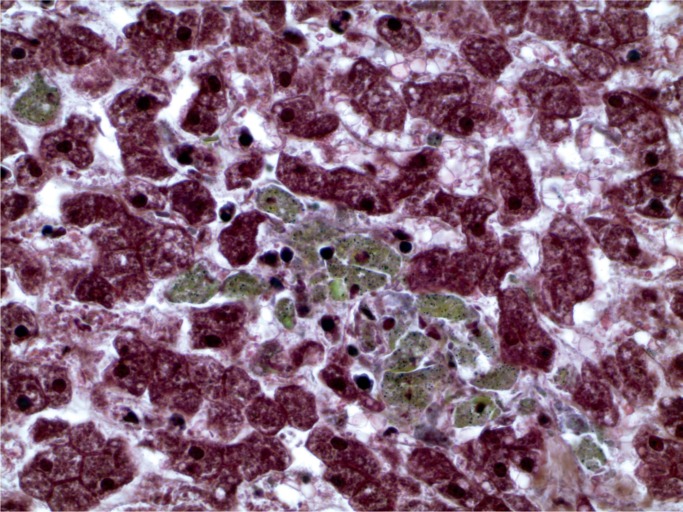

Image 20:

Liver with foreign body granulomata in portal tract (Movat, x200).

Image 21:

Liver with macrophages in sinsusoids containing foreign material (Movat, x400).

Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Complications of Stimulants

Cocaine, methamphetamine, and 3,4-methylenedi-oxymethamphetamine (MDMA) are frequently en-countered stimulant drugs that are associated with cardiovascular complications, including coronary artery atherosclerosis at a younger age, myocardi-al fibrosis, cardiomegaly, and myocardial infarction (40 –49). Other complications include coronary artery dissection (50–51) (Image 22), aortic dissection (52, 53), and thrombosis of other vessels, including effects on the gastrointestinal tract (54). Acute stimulant use may result in myocardial contraction band necrosis (see illustrative case). In the absence of resuscitation, this can be a useful finding to show that a stimulant drug has exerted cardiovascular effects. Cerebrovascular effects include cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, and rupture of berry aneurysms (55 –65).

Image 22:

Coronary artery dissection (Masson trichrome, x12.5).

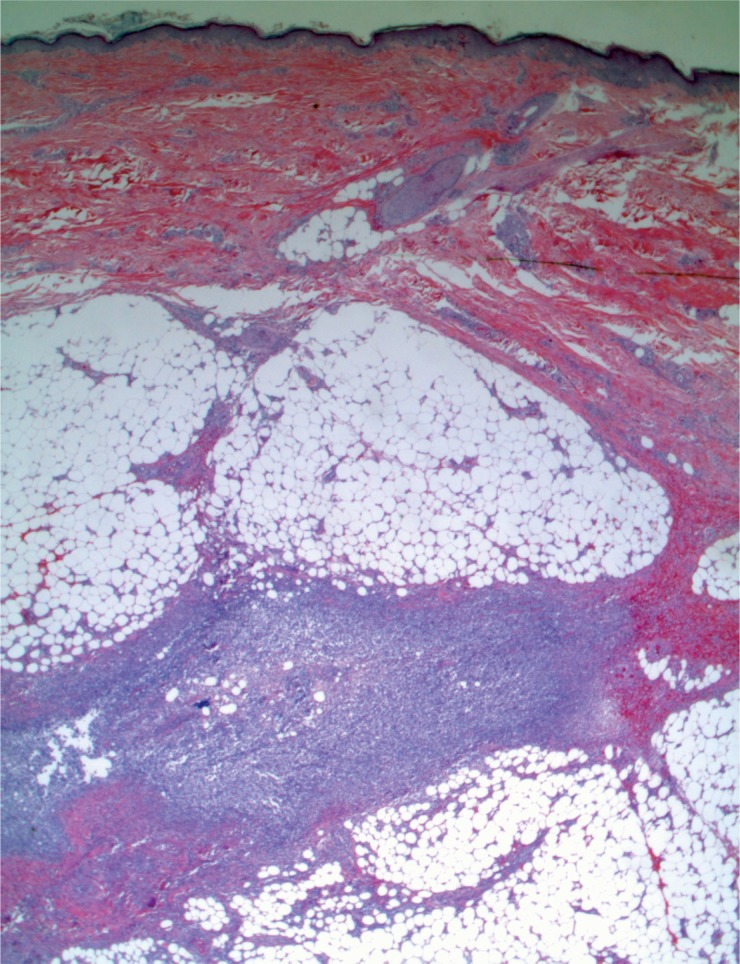

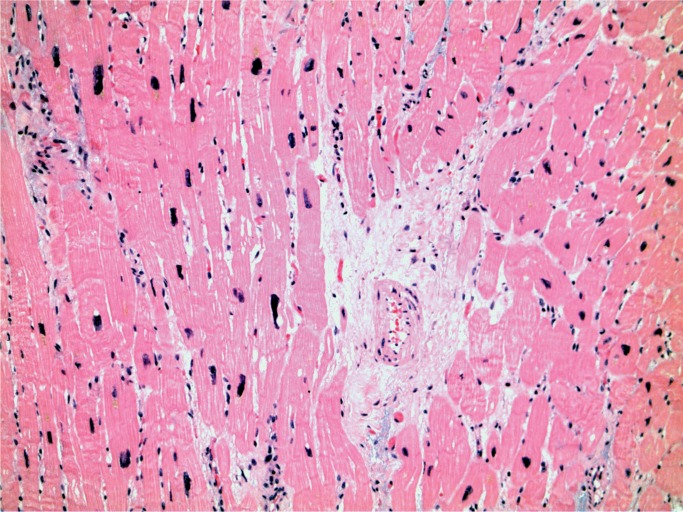

Illustrative Case—Cardiomegaly and Cocaine

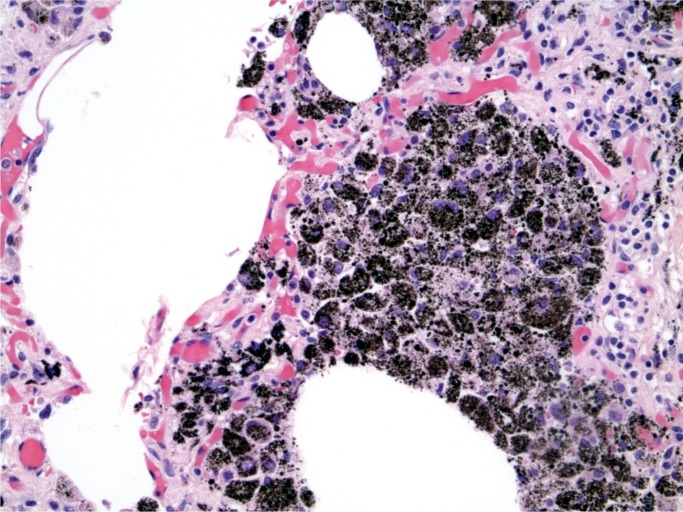

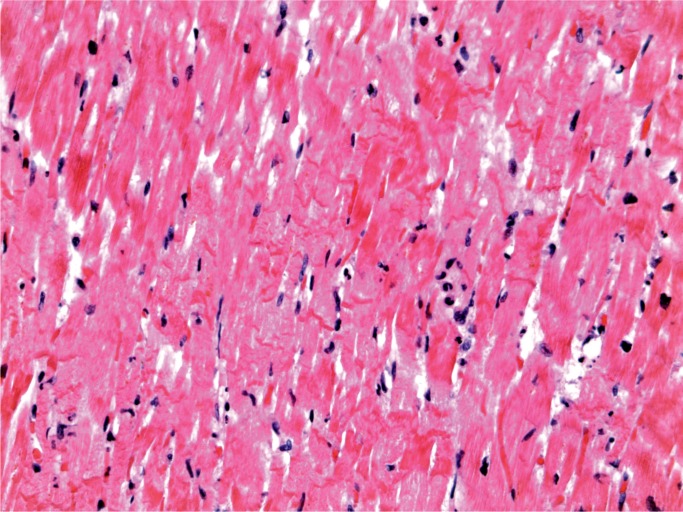

A 28-year-old woman with a history of intravenous drug abuse and previous endocarditis was found dead in her bed. At autopsy, old injection sites (“track marks”) were in the forearms and calves. The heart was enlarged, weighing 426 g (expected upper limit 387 g) and there was a 0.5 cm calcified nodule on the tricuspid valve. The lungs were congested and edem-atous, the right weighing 634 g and the left 498 g. On microscopic examination, the myocardium showed perivascular fibrosis (Image 23) and the lungs showed prominent carbon pigmented macrophages, typical of smoking “crack cocaine” (Image 24).

Image 23:

Myocardium with perivascular fibrosis (H&E, x200).

Image 24:

Lung with prominent carbon pigmented macrophages (H&E, x200).

Toxicological analysis revealed a benzoylecgonine concentration of 0.14 mg/L; cocaethylene was also present. The black carbon pigmented intraalveolar macrophages seen in crack cocaine smoking need to be contrasted with the brown pigmented intraalveolar macrophages that can be seen following tobacco and cannabis smoking (Image 25).

Image 25:

Lung with brown pigmented intraalveolar macrophages (H&E, x400).

Illustrative Case—Contraction Band Necrosis in Cocaine Use

A 32-year-old man with a history of drug and alcohol use was found dead on the floor of his bedroom. At autopsy, there were no injection marks. Macroscopically, the heart appeared normal, weighing 390 g. There was no significant coronary artery atherosclerosis. The lungs were heavy and edematous, the right weighing 802 g and the left 758 g. Toxicological analysis revealed the presence of carfentanil at a concentration of 46 ng/mL, alprazolam, cocaine and benzoylecgonine, ethanol at a concentration of 217 mg/100 mL, and cocaethylene. Microscopically, the heart showed myocyte necrosis with prominent contraction bands and a neutrophilic infiltratate (Images 26 to 28). These microscopic changes were due to cocaine toxicity.

Image 26:

Myocardium with acute ischemia (paler areas) (PTAH, x50).

Image 27:

Myocardium at high power showing ischemic areas with contraction band necrosis (PTAH, x400).

Image 28:

Myocardium with contraction band necrosis (H&E, 400).

Inhalational (Aspiration) Pneumonia/Pneumonitis

When there is a prolonged period of unconsciousness, typically seen with opiate/opioid overdose, there is often inhalation (aspiration) of gastric contents because of the ability to maintain the integrity of the airway (3). This can result in inflammation as a response to the acid in the gastric contents as well as infection from inhaled bacteria. The finding may be helpful when drugs may have been metabolized and postmortem concentrations are lower than typically seen in fatal toxicity (66).

Illustrative Case—Inhalation with Pneumonia

A 24-year-old man was found dead in bed. He had a history of drug use and drug paraphernalia was found at the scene. At autopsy, there were no stigmata of intravenous injection. His lungs were heavy, with a combined weight of 1526 g.

Toxicology revealed a fentanyl concentration of 5.6 ng/mL, cocaine of 0.008 mg/mL, and benzoylecgonine of 0.31 mg/L. Microscopic examination of the lungs revealed evidence of an inhalational pneumonia (Images 29 and 30).

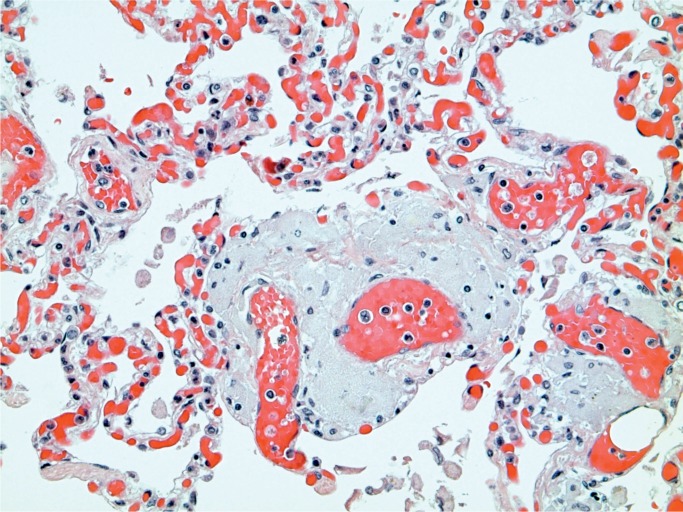

Image 29:

Lung with hemorrhage and inflammation from inhalation (H&E, x50).

Image 30:

Lung with inflammation from inhalation (H&E, x100).

Other Systemic Effects

Recreational drugs may have effects upon other organ systems. Heroin smoking has been associated with spongiform leukoencephaolopathy, a rare brain disorder that has been reported from several countries (67 –70). It has also been reported with methadone use (71). Cocaine has been associated with movement disorders including parkinsonism (72 –77), which has also been seen in patients taking 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), which was produced by clandestine laboratories trying to produce a meperidine derivative (78, 79). Patients with cocaine-induced excited delirium have altered dopamine and heat shock protein status (80).

Ketamine is a drug used medically as well as illicitly. It has been associated with disorders of the bladder in abusers of the drug (81). It has also been associated with liver disorders including biliary tract disease and sclerosing cholangitis (82). Heroin has been associated with development of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (83 –87). Rhabdomyolysis has been reported in heroin and stimulant drug users and can be identified at autopsy in the kidney, where myoglobin casts are seen in the renal tubules (Images 31 and 32) (88 –92).

Image 31:

Myoglobin casts in renal tubules (myoglobin, x100).

Image 32:

Renal casts in myoglobinuria (H&E, x200).

Hyperpyrexia has been associated with stimulant drug use, particularly with cocaine, amphetamine derivatives such as MDMA (ecstacy), and synthetic cathinones. The pathology of hyperpyrexia was initially reported in environmental conditions but has been shown to have the same pathology in drug-related cases. While the pathology is nonspecific, there may be changes in several organs. Steatosis with individual hepatocyte necrosis and dilatation of the sinusoids may occur, along with contraction and necrosis in the myocardium and ring hemorrhages in the brain. Rhabdomyolysis may occur and myoglobin casts can then be seen in the kidney (6).

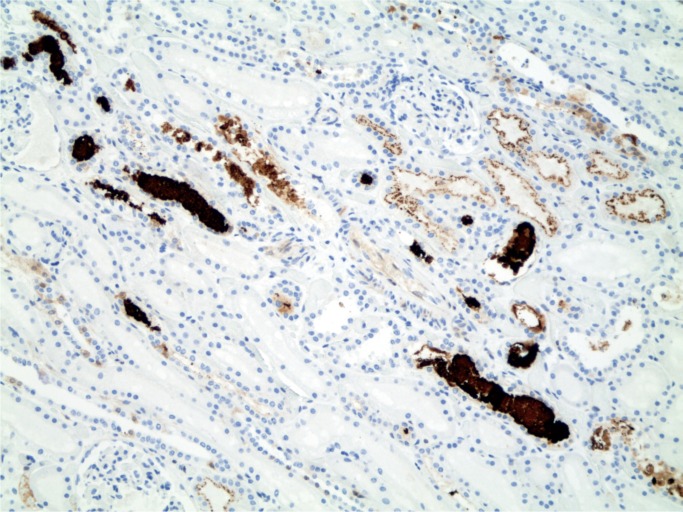

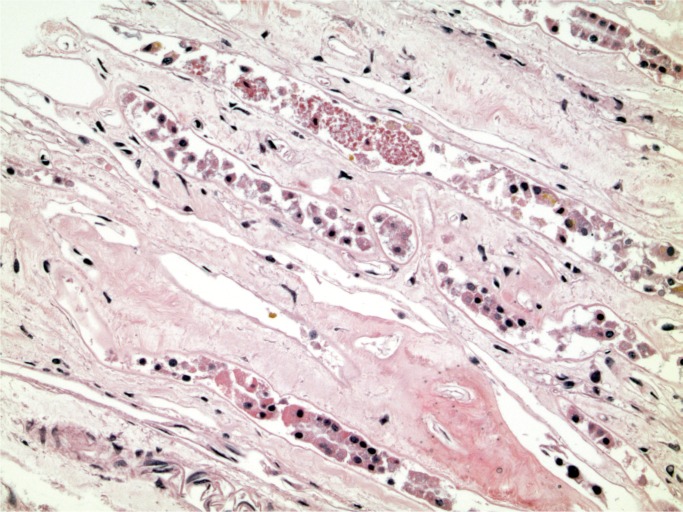

Illustrative Case—Ketamine Organ Toxicity

A 38-year-old man was prescribed ketamine and high dose opioids for chronic pain. His ketamine use was complicated by chronic liver injury, renal injury, and chronic cystitis. He had been starving himself and had previous admissions for starvation ketosis, urinary tract infections, and withdrawal symptoms but would discharge himself from hospital. He was found collapsed at home and died soon after admission to hospital. It was assumed he had had a hyperkalemic cardiac arrest but this could not be substantiated. At autopsy, there was evidence of coronary artery atherosclerosis. The kidneys appeared macroscopically normal but on histology there was a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the renal pelvis (Image 33). There was erythema of the bladder mucosa and the liver revealed areas of hepatic necrosis, primarily in zone 3 with a mixed chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate in the portal tracts with acute injury in bile ducts (Image 34).

Image 33:

Inflammation in renal pelvis due to ketamine toxicity (H&E, x50).

Image 34:

Portal tract inflammation with bile duct damage in ketamine toxicity (H&E, x100).

Conclusion

Recreational drug use is associated with pathology in multiple organs relating to both the route of administration and systemic effects. The histological changes can typically be identified by simple histological techniques. Histology can provide confirmation of the route of administration and systemic effects, such as contraction band necrosis following use of cocaine. Use of histology also provides information that is reviewable and can be important when a drug-related death is challenged.

Authors

Christopher M. Milroy MBChB MD LLB BA LLM FRCPath FFFLM FRCPC DMJ, The Ottawa Hospital - Anatomical Pathology

Roles: Project conception and/or design, data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work.

Charis Kepron MD MSc FRCPC, Ontario Forensic Pathology Service - Eastern Ontario Regional Forensic Pathology Unit

Roles: Data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work

Jacqueline L. Parai MD MSc FRCPC, The Ottawa Hospital - Anatomical Pathology

Roles: Data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

Statement of Informed Consent: No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscript

Disclosures & Declaration of Conflicts of Interest: Christopher M. Milroy is the Editor-In-Chief of Academic Forensic Pathology: The Official Publication of the National Association of Medical Examiners. The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any other relevant conflicts of interest

Financial Disclosure: The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

References

- 1). Milroy CM. Substance misuse: substance abuse – patterns and statistics In: Payne-James J, Byard R, editors. Encyclopedia of forensic and legal medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2). Karch SB, Drummer OH. Karch’s pathology of drug abuse. 5th ed Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2016. 878 p. [Google Scholar]

- 3). Milroy CM, Parai JL. The histopathology of drugs of abuse. Histopathology. 2011. October; 59(4):579–93. PMID: 21261690 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Cunningham KS. Alcohol and heart disease in the forensic setting. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2014. June; 4(2):172–9. 10.23907/2014.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Büttner A. Neuropathology of chronic alcohol abuse. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2014. June; 4(2):180–7. 10.23907/2014.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Milroy CM, Clark JC, Forrest AR. Pathology of deaths associated with “ecstasy” and “eve” misuse. J Clin Pathol. 1996 Feb; 49(2):149–53. PMID: 8655682. PMCID: PMC500349 10.1136/jcp.49.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Malamud N, Haymaker W, Custer RP. Heat stroke; a clinico-pathologic study of 125 fatal cases. Mil Surg. 1946 Nov; 99(5):397–449. PMID: 20276794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Gore I, Isaacson NH. The pathology of hyperpyrexia: observations at autopsy in 17 cases of fever therapy. Am J Pathol. 1949. September; 25(5): 1029–59. PMID: 18138922. PMCID: PMC1942925. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Chao TC, Sinniah R, Pakiam JE. Acute heat stroke deaths. Pathology. 1981. January; 13(1):145–56. PMID: 7220095 10.3109/00313028109086837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Hirsch CS. Dermatopathology of narcotic addiction. Hum Pathol. 1972. March; 3(1):37–53. PMID: 5060677 10.1016/s0046-8177(72)80052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Rosen VJ. Cutaneous manifestations of drug abuse by parenteral injections. Am J Dermatopathol. 1985. February; 7(1):79–83. PMID: 3977022 10.1097/00000372-198502000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Binswanger IA, Kral AH, Bluthenthal RN, et al. High prevalence of abscesses and cellulitis among community-recruited injection drug users in San Francisco. Clin Infect Dis. 2000. March; 30(3):579–81. PMID: 10722447 10.1086/313703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Galldiks N, Nolden-Hoverath S, Kosinski CM, et al. Rapid geograph-ical clustering of wound botulism in Germany after subcutaneous and intramuscular injection of heroin. Neurocrit Care. 2007; 6(1):30–4. PMID: 17356188 10.1385/NCC:6:1:30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Passaro DJ, Werner SB, McGee J, et al. Wound botulism associated with black tar heroin among injecting drug users. JAMA. 1998. March 18; 279(11):859–63. PMID: 9516001 10.1001/jama.279.11.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Booth MG, Hood J, Brooks TJ, et al. Anthrax infection in drug users. Lancet. 2010. April 17; 375(9723):1345–6. PMID: 20399978 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60573-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Hicks CW, Sweeney DA, Cui X, et al. An overview of anthrax infection including the recently identified form of disease in injection drug users. Intensive Care Med. 2012. July; 38(7):1092–104. PMID: 22527064. PMCID: PMC3523299 10.1007/s00134-012-2541-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Unexplained illness and death among injecting-drug users – Glasgow, Scotland; Dublin, Ireland; and England, April-June 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000. June 9; 49(22):489–92. PMID: 10881764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: Clostridium novyi and unexplained illness among injecting-drug users – Scotland, Ireland, and England, April–June 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000. June 23; 49(24):543–5. PMID: 10923856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Finn SP, Leen E, English L, O’Briain DS. Autopsy findings in an outbreak of severe systemic illness in heroin users following injection site inflammation: an effect of Clostridium novyi exotoxin? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003. November; 127(11):1465–70. PMID: 14567722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Neugarten J, Gallo G, Buxbaum J, et al. Amyloidosis in subcutaneous heroin abusers (“skin poppers’ amyloidosis”). Am J Med. 1986. October; 81(4):635–40. PMID: 3766593 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90550-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Tan AU, Cohen AH, Levine BS. Renal amyloidosis in a drug abuser. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995. March; 5(9):1653–8. PMID: 7780053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Dressler FA, Roberts WC. Infective endocarditis in opiate addicts: an analysis of 80 cases studied at necropsy. Am J Cardiol. 1989. May 15; 63(17):1240–57. PMID: 2711995 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Brown P, Levine D. Infective endocarditis in the injection drug user. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002. September; 16(3):645–65, viii–ix. PMID: 12371120 10.1016/s0891-5520(02)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Moss R, Munt B. Injection drug use and right sided endocarditis. Heart. 2003. May; 89(5):577–81. PMID: 12695478. PMCID: PMC1767660 10.1136/heart.89.5.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Chambers HF, Morris DL, Tauber MG, Modin G. Cocaine use and the risk for endocarditis in intravenous drug users. Ann Intern Med. 1987. June; 106(6):833–6. PMID: 3579070 10.7326/0003-4819-106-6-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Passarino G, Ciccone G, Siragusa R, et al. Histopathological findings in 851 autopsies of drug addicts, with toxicologic and virologic correlations. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2005. June; 26(2):106–16. PMID: 15894841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Dhopesh VP, Taylor KR, Burke WM. Survey of hepatitis B and C in addiction treatment unit. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000. November; 26(4):703–7. PMID: 11097200 10.1081/ada-100101903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Fuller CM, Ompad DC, Galea S, et al. Hepatitis C incidence – a comparison between injection and noninjection drug users in New York City. J Urban Health. 2004. March; 81(1):20–4. PMID: 15047780. PMCID: PMC3456148 10.1093/jurban/jth084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Burt RD, Hagan H, Garfein RS, et al. Trends in hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus prevalence, risk behaviors, and preventive measures among Seattle injection drug users aged 18– 30 years, 1994–2004. J Urban Health. 2007. May; 84(3):436–54. PMID: 17356901. PMCID: PMC2231834 10.1007/s11524-007-9178-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Neaigus A, Zhao M, Gyarmathy VA, et al. Greater drug injecting risk for HIV, HBV, and HCV infection in a city where syringe exchange and pharmacy syringe distribution are illegal. J Urban Health. 2008. May; 85(3):309–22. PMID: 18340537. PMCID: PMC2329750 10.1007/s11524-008-9271-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Burns SM, Brettle RP, Gore SM, et al. The epidemiology of HIV infection in Edinburgh related to the injecting of drugs: an historical perspective and new insight regarding the past incidence of HIV infection derived from retrospective HIV antibody testing of stored samples of serum. J. Infect. 1996; 32:53–62. PMID: 8852552 10.1016/s0163-4453(96)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Wendt VE, Puro HE, Shapiro J, et al. Angiothrombotic pulmonary hypertension in addicts: “Blue Velvet” addiction. JAMA. 1964. May 25; 188:755–7. PMID: 14122687 10.1001/jama.1964.03060340053017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Lewman LV. Fatal pulmonary hypertension from intravenous injection of methylphenidate (Ritalin) tablets. Hum Pathol. 1972. March; 3(1):67–70. PMID: 5060680 10.1016/s0046-8177(72)80054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Tomashefski JF, Jr, Hirsch C. The pulmonary vascular lesions of intravenous drug abuse. Hum Pathol. 1980. March; 11(2):133–45. PMID: 7399505 10.1016/s0046-8177(80)80130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Tomashefski JF, Jr, Hirsch CS, Jolly PN. Microcrystalline cellulose pulmonary embolism and granulomatosis. A complication of illicit intravenous injections of pentazocine tablets. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1981. February; 105(2):89–93. PMID: 6893924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Tomashefski J, Felo JA. The pulmonary pathology of illicit drug and substance abuse. Curr. Diagn. Pathol. 2004; 10:413–26. 10.1016/j.cdip.2004.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Nguyen VT, Chan ES, Chou SH, et al. Pulmonary effects of iv injection of crushed oral tablets: “excipient lung disease”. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014. November; 203(5): W506–15. PMID: 25341165 10.2214/ajr.14.12582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Blair SD, Holcombe C, Coombes EN, O’Malley MK. Leg ischaemia secondary to non-medical injection of temazepam. Lancet. 1991. November 30; 338(8779):1393–4. PMID: 1682755 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39). Coughlin PA, Mavor AID. Arterial consequences of recreational drug use. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006. October; 32(4):389–96. PMID: 16682239 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40). Lange RA, Hillis D. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine use. N Engl J Med. 2001. August 2; 345(5):351–8. PMID: 11484693 10.1056/nejm200108023450507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41). Karch SB, Billingham ME. The pathology and etiology of cocaine-induced heart disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1988. March; 112(3):225–30. PMID: 2178699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42). Mittleman RE, Wetli CV. Cocaine and sudden “natural” death. J Forensic Sci. 1987. January; 32(1):11–9. PMID: 3819672 10.1520/jfs12322j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43). Karch SB, Green GS, Young S. Myocardial hypertrophy and coronary artery disease in male cocaine users. J Forensic Sci. 1995. July; 40(4):591–5. PMID: 7595294 10.1520/jfs13831j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44). Egred M, Davis GK. Cocaine and the heart. Postgrad Med J. 2005. Sep; 81(959):568–71. PMID: 16143686. PMCID: PMC1743343 10.1136/pgmj.2004.028571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45). Dressler FA, Malekzadeh S, Roberts WC. Quantitative analysis of amounts of coronary arterial narrowing in cocaine addicts. Am J Cardiol. 1990. February 1; 65(5):303–8. PMID: 2301258 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46). Karch SB, Billingham ME. Coronary artery and peripheral vascular disease in cocaine users. Coron Artery Dis. 1995. March; 6(3):220–5. PMID: 7788034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47). Virmani R, Robinowitz M, Smialek JE, Smyth DF. Cardiovascular effects of cocaine: an autopsy study of 40 patients. Am Heart J. 1988. May; 115(5):1068–76. PMID: 3364339 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90078-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48). Frishman WH, Del Vecchio A, Sanal S, Ismail A. Cardiovascular manifestations of substance abuse part 1: cocaine. Heart Dis. 2003. May-Jun; 5(3):187–201. PMID: 12783633 10.1097/01.hdx.0000074519.43281.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49). Afonso L, Mohammad T, Thatai D. Crack whips the heart: a review of the cardiovascular toxicity of cocaine. Am J Cardiol. 2007. September 15; 100(6):1040–3. PMID: 17826394 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50). Jaffe BD, Broderick TM, Leier CV. Cocaine-induced coronary-artery dissection. N Engl J Med. 1994. February 17; 330(7):510–1. PMID: 8289869 10.1056/nejm199402173300719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51). Steinhauer JR, Caulfield JB. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection associated with cocaine use: a case report and brief review. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2001. May-Jun; 10(3):141–5. PMID: 11485859 10.1016/s1054-8807(01)00074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52). Cohle SD, Lie JT. Dissection of the aorta and coronary arteries associated with acute cocaine intoxication. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1992. November; 116(11):1239–41. PMID: 1444754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53). Daniel JC, Huynh TT, Zhou W, et al. Acute aortic dissection associated with use of cocaine. J Vasc Surg. 2007. September; 46(3):427–33. PMID: 17826227 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54). Edgecombe A, Milroy C. Sudden death from superior mesenteric artery thrombosis in a cocaine user. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2012. Mar; 8(1):48–51. PMID: 21590456 10.1007/s12024-011-9248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55). Smith C, Forrest ARW. Forensic neuropathology. London: Hodder; Arnold; c2005. Chapter 14, Alcohol, drugs and toxins; p. 168–179. [Google Scholar]

- 56). Klonoff DC, Andrews BT, Obana WG. Stroke associated with cocaine use. Arch Neurol. 1989. September; 46(9):989–93. PMID: 2673163 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520450059019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57). Petitti DB, Sidney S, Quesenberry C, Bernstein A. Stroke and cocaine or amphetamine use. Epidemiology. 1998. November; 9(6):596–600. PMID: 9499166 10.1097/00001648-199811000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58). Konzenn JP, Levine SR, Garcia JH. Vasospasm and thrombus formation as possible mechanisms of stroke related to alkaloid cocaine. Stroke. 1995. June; 26(6):1114–8. PMID: 7762031 10.1161/01.str.26.6.1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59). Nanda A, Vannemreddy P, Willis B, Kelley R. Stroke in the young: relationship of active cocaine use with stroke mechanism and outcome. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2006; 96:91–6. PMID: 16671433 10.1007/3-211-30714-1_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60). Neiman J, Haapaniemi HM, Hillbom M. Neurological complications of drug abuse: pathophysiological mechanisms. Eur J Neurol. 2000. November; 7(6):595–606. PMID: 11136345 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2000.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61). Buttner A, Mall G, Penning R, et al. The neuropathology of cocaine abuse. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2003. March; 5 Suppl 1: S240–2. 10.1016/s1344-6223(02)00122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62). McGee SM, McGee DN, McGee MB. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage related to methamphetamine abuse: autopsy findings and clinical correlation. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2004. December; 25(4): 334–7. PMID: 15577524 10.1097/01.paf.0000137206.16785.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63). Ho EL, Josephson SA, Lee HS, Smith WS. Cerebrovascular complications of methamphetamine abuse. Neurocrit Care. 2009; 10(3):295–305. PMID: 19132558 10.1007/s12028-008-9177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64). Fressler RD, Esshaki CM, Stankewitz RC, et al. The neurovascular complications of cocaine. Surg Neurol. 1997. April; 47(4):339–45. PMID: 9122836 10.1016/s0090-3019(96)00431-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65). Cadet JL, Bisagno V, Milroy CM. Neuropathology of substance use disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2014. January; 127(1):91–107. PMID: 24292887 10.1007/s00401-013-1221-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66). Wolters EC, van Wijngaarden GK, Stam FC, et al. Leucoencephalopathy after inhaling “heroin” pyrolysate. Lancet. 1982. December 4; 2(8310):1233–7. PMID: 6128545 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67). Milroy CM, Forrest AR. Methadone deaths: a toxicological analysis. J Clin Pathol. 2000. April; 53(4):277–81. PMID: 10823123. PMCID: PMC1731168 10.1136/jcp.53.4.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68). Tan TP, Algra PR, Valk J, Wolters EC. Toxic leukoencephalopathy after inhalation of poisoned heroin: MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994. January; 15(1):175–8. PMID: 8141052. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69). Kriegstein AR, Armitage BA, Kim PY. Heroin inhalation and progressive spongiform leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 1997. Feb 20; 336(8):589–90. PMID: 9036319 10.1056/nejm199702203360818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70). Krinsky CS, Reichard RR. Chasing the dragon: a review of toxic leukoencephalopathy. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2012. March; 2(1):67–73. https://doi.org/10.23907%2F2012.009. [Google Scholar]

- 71). Salgado RA, Jorens PG, Baar I, et al. Methadone-induced toxic leukoencephalopathy: MR imaging and MR proton spectroscopy findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010. March; 31(3):565–6. PMID: 19892815. 10.3174/ajnr.a1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72). Nnadi CU, Mimiko OA, McCurtis HL, Cadet JL. Neuropsychiatric effects of cocaine use disorders. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005. November; 97(11): 1504–15. PMID: 16334497. PMCID: PMC2594897. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73). Habal R, Sauter D, Olowe O, Daras M. Cocaine and chorea. Am J Emerg Med. 1991. November; 9(6):618–20. PMID: 1930408 10.1016/0735-6757(91)90125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74). Daras M, Koppel BS, Atos-Radzion E. Cocaine-induced choreoathetoid movements (‘crack dancing’). Neurology. 1994. April; 44(4): 751–2. PMID: 8164838 10.1212/wnl.44.4.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75). Catalano G, Catalano MC, Rodriguez R. Dystonia associated with crack cocaine use. South Med J. 1997. October; 90(10):1050–2. PMID: 9347821 10.1097/00007611-199710000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76). Fines RE, Brady WJ, DeBehnke DJ. Cocaine-associated dystonic reaction. Am J Emerg Med. 1997. September; 15(5):513–5. PMID: 9270394 10.1016/s0735-6757(97)90198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77). Koppel BS, Samkoff L, Daras M. Relation of cocaine use to seizures and epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1996. September; 37(9):875–8. PMID: 8814101 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78). Davis GC, Williams AC, Markey SP, et al. Chronic Parkinsonism secondary to intravenous injection of meperidine analogues. Psychiatry Res. 1979. December; 1(3):249–54. PMID: 298352 10.1016/0165-1781(79)90006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79). Langston JW, Ballard P, Tetrud JW, Irwin I. Chronic Parkinsonism in humans due to a product of meperidine–analog synthesis. Science. 1983. February 25; 219(4587):979–80. PMID: 6823561 10.1126/science.6823561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80). Mash DC, Duque L, Pablo J, et al. Brain biomarkers for identifying excited delirium as a cause of sudden death. Forensic Sci Int. 2009. Sep 10; 190(1-3): e13–9 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81). Chu PS, Ma WK, Wong SC, et al. The destruction of the lower urinary tract by ketamine abuse: a new syndrome? BJU Int. 2008. Dec; 102(11):1616–22. PMID: 18680495 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2008.07920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82). Turkish A, Luo JJ, Lefkowitch JH. Ketamine abuse, biliary tract disease, and secondary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2013. Aug; 58(2):825–7. PMID: 23695896 10.1002/hep.26459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83). Rao TK, Nicastri AD, Friedman EA. Natural history of heroin associated nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1974. January 3; 290(1):19–23. PMID: 4128109 10.1056/nejm197401032900105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84). Cunningham EE, Zielezny MA, Venuto RC. Heroin-associated nephropathy. A nationwide problem. JAMA. 1983. December 2; 250(21): 2935–6. PMID: 6644972 10.1001/jama.250.21.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85). Dubrow A, Mittman N, Ghali V, Flamenbaum W. The changing spectrum of heroin-associated nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1985. January; 5(1):36–41. PMID: 3966467 10.1016/s0272-6386(85)80133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86). Friedman EA, Tao TK. Disappearance of uremia due to heroin associated nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995. May; 25(5):689–93. PMID: 7747721 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90543-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87). do Sameiro Faria M, Sampaio S, Faria V, Carvalho E. Nephropathy associated with heroin abuse in Caucasian patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003. November; 18(11):2308–13. PMID: 14551358 10.1093/ndt/gfg369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88). Richter RW, Challenor YB, Pearson J, et al. Acute myoglobinuria associated with heroin addiction. JAMA. 1971. May 17; 216(7): 1172–6. PMID: 5108401 10.1001/jama.1971.03180330048009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89). Ruttenber AJ, McNally HB, Wetli CV. Cocaine-associated rhabdomyolysis and excited delirium: different stages of the same syndrome. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1999. June; 20(2):120–7. PMID: 10414649 10.1097/00000433-199906000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90). Fahal IH, Sallomi DF, Yaqoob M, Bell GM. Acute renal failure after ecstasy. BMJ. 1992. July 4; 305(6844):29 PMID: 1353389 10.1136/bmj.305.6844.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91). Lehmann ED, Thom CH, Croft DN. Delayed severe rhabdomyolysis after taking ‘ecstasy’. Postgrad Med J. 1995. March; 71(833): 186–7. PMID: 7745785. PMCID: PMC2398185 10.1136/pgmj.71.833.186-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92). Penders TM, Gestring RE, Vilensky DA. Excited delirium following use of synthetic cathinones (bath salts). Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012. Nov-Dec; 34(6):647–50. PMID: 22898445 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]