Abstract

Background

Controversies remain regarding clinical outcomes following initial strategies of coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) vs usual care with functional testing in patients with suspected coronary artery disease (CAD).

Hypothesis

CCTA as initial diagnostic strategy results in better mid‐ to long‐term outcomes than usual care in patients with suspected CAD.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library for randomized controlled trials comparing clinical outcomes during ≥6 months' follow‐up between initial anatomical testing by CCTA vs usual care with functional testing in patients with suspected CAD. Occurrence of all‐cause mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and use of invasive coronary angiography and coronary revascularization, were compared between the 2 diagnostic strategies.

Results

Twelve trials were included (20 014 patients; mean follow‐up, 20.5 months). Patients undergoing CCTA as initial noninvasive testing had lower risk of nonfatal MI compared with those treated with usual care (risk ratio [RR]: 0.70, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.52‐0.94, P = 0.02). There was a tendency for reduced MACE following initial CCTA strategy, but not for risk of all‐cause mortality. Compared with functional testing, the CCTA strategy increased use of invasive coronary angiography (RR: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.12‐2.09, P = 0.007) and coronary revascularization (RR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.11‐2.00, P = 0.007).

Conclusions

Anatomical testing with CCTA as the initial noninvasive diagnostic modality in patients with suspected CAD resulted in lower risk of nonfatal MI than usual care with functional testing, at the expense of more frequent use of invasive procedures.

Keywords: Anatomical Testing, Coronary Artery Disease, Coronary CT Angiography, Functional Testing, Meta‐Analysis

1. INTRODUCTION

Until recently, the most commonly used diagnostic tests for patients with suspected coronary artery disease (CAD) were functional tests, such as myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI), stress echocardiography, or exercise treadmill testing.1, 2 However, the emergence of coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) produced a substantial shift in diagnostic strategy: the use of CCTA expanded rapidly while the limitations of functional testing were highlighted, in that such tests cannot demonstrate the degree of coronary artery stenosis and the nature of coronary plaque.

Given the well‐established diagnostic accuracy of CCTA, the primary concern has shifted to longer‐term clinical outcomes.3, 4, 5 Two recent trials, the Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain (PROMISE) and the Scottish Computed Tomography of the HEART (SCOT‐HEART), investigated long‐term outcomes following CCTA compared with usual care, but their results were inconclusive.6 Several meta‐analyses also compared the outcomes of CCTA vs usual care. However, because those meta‐analyses combined short‐term follow‐up studies with mid‐ and long‐term follow‐up studies, their results are difficult to apply to clinical practice.7, 8 Furthermore, current clinical guidelines provide inconsistent recommendations on the diagnostic approach for those with suspected CAD.1, 2, 9

In this meta‐analysis, we aimed to investigate the mid‐ to long‐term clinical outcomes following the initial strategies of noninvasive testing in patients with suspected CAD by comparing anatomical testing using CCTA with usual care.

2. METHODS

We performed a systematic review and meta‐analysis of the available published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that reported clinical outcomes after the initial strategy of anatomical testing with CCTA and usual care. This study was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement (see Supporting Information, Table S1, in the online version of this article).10

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched Ovid‐MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials for all published RCTs that compared the initial strategy of anatomical testing using CCTA vs usual care with functional testing in patients suspected for CAD up to January 2016. Also, we manually screened the reference lists of the identified trials to identify all relevant studies. The following keywords were used for each database: “coronary CT angiography,” “cardiac CT,” “heart CT,” “myocardial SPECT,” “myocardial single photon emission computed‐tomography,” “MPI,” “myocardial perfusion imaging,” “myocardial perfusion scintigraphy,” “cardiac radionuclide imaging,” “stress perfusion,” “stress echocardiography,” “exercise echocardiography,” “treadmill test,” “exercise test,” “exercise EKG,” “exercise ECG,” and “exercise electrocardiography.” Some adjustments were required to reflect the characteristics of the databases.

Selection criteria were (1) study design: prospective RCTs; (2) target population: adult; (3) follow‐up duration: ≥6 months; and (4) language: either English or Korean. Exclusion criteria were (1) purpose of the intervention: not diagnosis; (2) non–original report; (3) duplicate of an included published article; and (4) full‐text version could not be obtained. In addition, studies were excluded if the study population consisted of those with acute myocardial infarction (MI) or the treatment plans were not based on the results of noninvasive testing.

2.2. Study selection and quality assessment

Four investigators (ICH, JYK, EBK, and SJC), grouped in pairs, reviewed the results of the literature searches independently in a 2‐stage selection processes to maintain the objectivity. In the primary process, the title and abstract were revised; in the secondary process, the full‐text versions were reviewed. The aforementioned inclusion/exclusion criteria were decided before the selection process.

The investigators conducted extraction of study data independently, and data of each trial were assessed for validity. The following data were extracted from each trial: study design with inclusion and exclusion criteria, number of patients, baseline patient characteristics, pretest probability of having obstructive CAD, utilization of noninvasive tests, follow‐up duration, and clinical outcomes. Cases of disagreement within a pair of reviewers were resolved through a process involving the other pair of reviewers. Quality assessments were conducted (see Supporting Information, Figure S1, in the online version of this article).10

2.3. Study outcomes

Primary outcomes were the occurrence of nonfatal MI and all‐cause mortality. We also assessed the occurrence of a major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE), which was a composite of cardiovascular mortality, nonfatal MI, and acute coronary syndrome. Secondary outcomes included the use of invasive coronary angiography (ICA) and coronary revascularization.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with dichotomized variables using a fixed model or a random‐effect model, and the results were reported as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The statistical strength was evaluated by the overall effect size (Z) and heterogeneity index (I 2). A fixed‐effect model was used for the analysis with a heterogeneity index <25%, and a random‐effect model was used for the analysis with a heterogeneity index ≥25%. Potential publication bias was examined with funnel plots (see Supporting Information, Figures S2 and S4, in the online version of this article). The Egger regression test was used to test funnel‐plot asymmetry, which was then corrected using the trim‐and‐fill method.11 As a sensitivity analysis, we compared the impacts of the 2 initial diagnostic strategies, the initial CCTA strategy vs usual care, among the studies with a follow‐up duration ≥12 months.

Statistical significance was set at the 2‐tailed 0.05 level for hypothesis testing of effect sizes and at the 2‐tailed 0.10 level for hypothesis testing of statistical heterogeneity and small study effects. Review Manager 5.0 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) and R version 3.2.1 (www.r-project.org) were used for statistical analyses.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Searching results and study selection

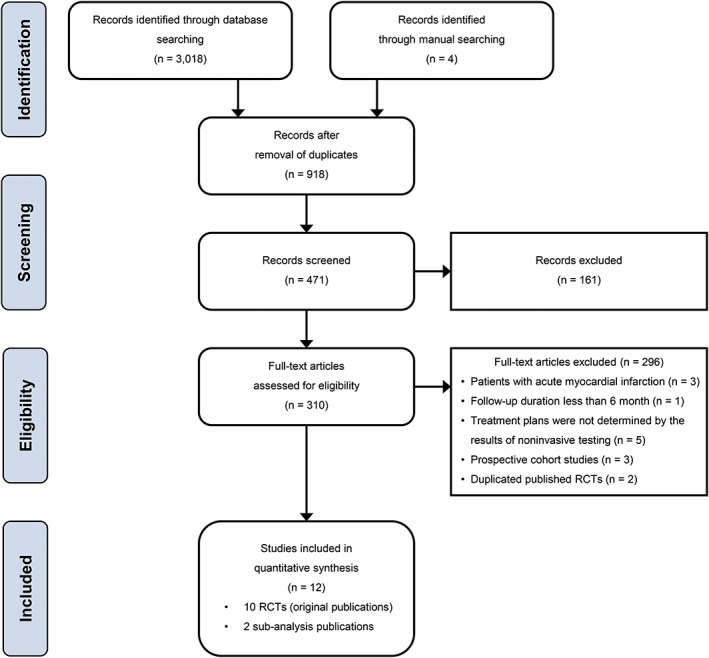

We identified 12 RCTs (10 original publications and 2 subanalysis publications) that were compatible with our selection criteria (Figure 1): the 2 subanalysis publications were from the Cardiac CT in the Treatment of Acute Chest Pain (CATCH) trial by Linde et al..12, 13 and the American College of Radiology Imaging Network–Pennsylvania (ACRIN‐PA) 4005 trial by Litt et al and Hollander et al.14, 15 Among each of these 2 pairs of reports, we selected the report with longer follow‐up duration.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection. Abbreviations: RCT, randomized controlled trial

A total of 20 014 patients with suspected CAD were enrolled in the selected studies: 10 268 patients were assigned to an initial strategy of anatomical testing with CCTA, and 9627 patients were assigned to an initial strategy of usual care. The mean follow‐up duration of the included RCTs was 20.5 months.

3.2. Details of study design and results

The included studies were heterogeneous in terms of the symptomatic status, modality of functional testing, and follow‐up duration (Table 1). Among the total included studies, 7 RCTs investigated the impact of CCTA strategy in patients with acute chest pain: the Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography for Systematic Triage of Acute Chest Pain Patients to Treatment (CT‐STAT) trial,16 the CT Coronary Angiography Compared to Exercise ECG (CT‐COMPARE) trial,17 the CATCH trial,13 the Prospective Randomized Outcome Trial Comparing Radionuclide Stress Myocardial Perfusion Imaging and ECG‐gated CCTA (PROSPECT),18 the Prospective First Evaluation in Chest Pain (PERFECT) trial,19 the study by Faisal Nabi et al.,20 and the ACRIN‐PA 4005 trial.15 Five RCTs enrolled patients with stable chest pain: the Cardiac CT for the Assessment of Pain and Plaque (CAPP) trial,21 the Computed Tomography vs Exercise Testing in Suspected Coronary Artery Disease (CRESCENT) trial,22 the PROMISE trial,6 the SCOT‐HEART trial,23 and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)‐SPECT/CTA study.24 The mean or median follow‐up durations of the included studies varied significantly, ranging from 6 months to 42 months.

Table 1.

Included randomized controlled trials

| Trial (Year) | Setting | No. of Patients (CCTA/Functional) | Age, y | Male Sex, % | HTN, % | DM, % | Dyslipidemia, % | Smoking, % | Prior CHD, % | Typical Angina, % | Pretest Probability, % | Functional Testing | Follow‐up, mo | Primary Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT‐STAT (2011)16 | Acute chest pain | 749 (361/338) | 50 | 47 | 38 | 7 | 34 | 23 | 0 | — | — | MPI (SPECT) | 6 | Time to diagnosis |

| CT‐COMPARE (2014)17 | Acute chest pain | 562 (322/240) | 52 | 58 | 31 | 7 | 25 | 23 | 0 | — | Intermediatea | Stress echo | 12 | Diagnostic performance, hospital cost |

| CAPP (2015)21 | Stable chest pain | 500 (243/245) | 58 | 55 | 75 | 13 | — | 47 | 0 | 31 | 46.3 | TMT | 12 | All‐cause mortality, STEMI, NSTEMI, HF admission, and stroke |

| CATCH (2015)13 | Acute chest pain | 600 (285/291) | 56 | 57 | 42 | 11 | 38 | — | 14 | 12 | 34.99 | TMT (76%), MPI (SPECT; 22%) | 18.7 | Cardiac death, MI, hospitalization for UA, late symptom‐driven revascularizations, and readmission for chest pain |

| PROSPECT (2015)18 | Acute chest pain | 400 (200/200) | 57 | 37 | 72 | 32 | 52 | 15 | 0 | — | 37 | MPI (SPECT) | 41.7 | Invasive angiography not leading to revascularization |

| PROMISE (2015)6 | Stable chest pain | 10 003 (4996/5007) | 61 | 47 | 65 | 21 | 68 | 51 | 0 | 12 | 53.3 | MPI (SPECT; 67.3%), stress echo (22.5%), TMT (10.2%) | 25 | Death, MI, hospitalization for UA, or major procedural complication |

| SCOT‐HEART (2015)23 | Stable chest pain | 4146 (2073/2073) | 57 | 56 | 34 | 11 | 53 | 53 | 9 | 35 | 47 | TMT (85%), MPI (SPECT; 10%), stress echo (1%) | 20.4 | Certainty of the diagnosis of angina secondary to CAD |

| ACRIN‐PA (2016)15 | Acute chest pain | 1392 (907/461) | 49 | 47 | 51 | 14 | 27 | 33 | 1 | — | — | Stress test with imaging | 12 | Cardiac death or MI |

| CRESCENT (2016)22 | Stable chest pain | 350 (242/108) | 55 | 45 | 52 | 17 | 56 | 35 | 0 | 24 | 45 | TMT | 12 | Absence of chest‐pain complaints after 1 year |

| IAEA‐SPECT/CTA (2016)24 | Stable chest pain | 303 (152/151) | 60 | 48 | 64 | 15 | 57 | 20 | 0 | — | Intermediate | MPI | 6b | Downstream noninvasive or invasive testing |

| Nabi et al (2016)20 | Acute chest pain | 598 (288/310) | 53 | 44 | 50 | 15 | 38 | 27 | 0 | — | — | MPI (stress‐only SPECT) | 6.5 | Length of hospital stay |

| PERFECT (2016)19 | Acute chest pain | 411 (206/205) | 60 | 47 | 69 | 29 | 48 | 45 | 0 | 18 | — | Stress echo (96%), MPI (SPECT; 4%) | 12 | Time to discharge, change in medication usage, frequency of downstream testing, cardiac interventions, and cardiovascular rehospitalizations |

Abbreviations: ACRIN‐PA, American College of Radiology Imaging Network–Pennsylvania; CAD, coronary artery disease; CAPP, Cardiac CT for the Assessment of Pain and Plaque; CATCH, Cardiac CT in the Treatment of Acute Chest Pain; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; CHD, coronary heart disease; CRESCENT, Computed Tomography vs Exercise Testing in Suspected Coronary Artery Disease; CT, computed tomography; CT‐COMPARE, CT Coronary Angiography to Measure Plaque Reduction; CT‐STAT, Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography for Systematic Triage of Acute Chest Pain Patients to Treatment; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECG, electrocardiography; HF, heart failure; HTN, hypertension; IAEA‐SPECT/CTA, International Atomic Energy Agency–Functional compared to anatomical imaging in the initial evaluation of patients with suspected coronary artery disease; MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction; PERFECT, Prospective First Evaluation in Chest Pain; PROMISE, Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain; PROSPECT, Prospective Randomized Outcome Trial Comparing Radionuclide Stress Myocardial Perfusion Imaging and ECG‐gated CCTA; SCOT‐HEART, Scottish Computed Tomography of the HEART; SPECT, single‐photon emission computed tomography; STEMI, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction; TMT, treadmill test; UA, unstable angina.

Intermediate probability of CAD according to the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand guidelines.

IAEA‐SPECT/CTA: Follow‐up duration for clinical outcomes, 6 months; follow‐up duration for costs and procedures, 12 months.

3.3. Initial diagnostic strategy and the risk of cardiovascular events

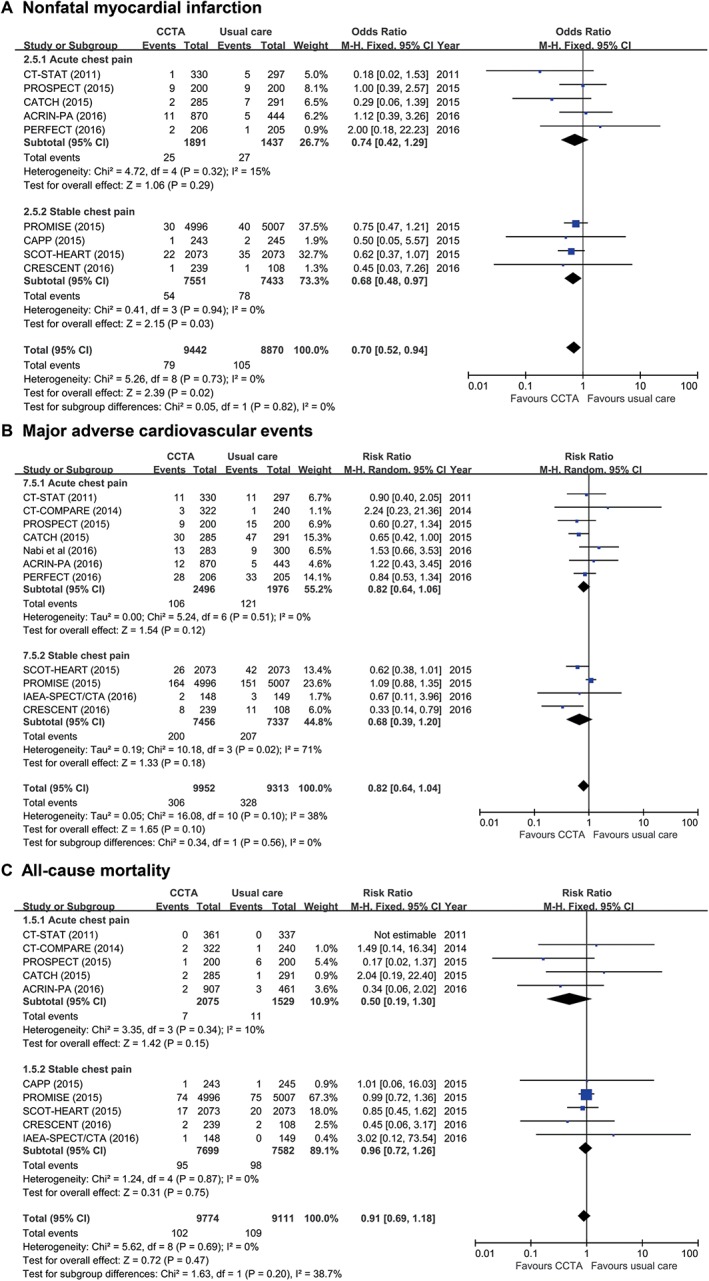

Clinical outcomes following the initial noninvasive diagnostic strategies with CCTA vs usual care are shown in Figure 2. The initial CCTA strategy was followed by a significantly reduced occurrence of nonfatal MI (RR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.52‐0.94, P = 0.02; Figure 2A). The risk of the occurrence of MACE and all‐cause mortality did not differ between the 2 diagnostic strategies (RR: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.62‐1.04, P = 0.10 for MACE, Figure 2B; and RR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.69‐1.18, P = 0.47 for all‐cause mortality, Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Clinical outcomes following initial anatomical vs functional testing for (A) nonfatal MI, (B) MACE, and (C) all‐cause mortality. Abbreviations: ACRIN‐PA, American College of Radiology Imaging Network–Pennsylvania; CAPP, Cardiac CT for the Assessment of Pain and Plaque; CATCH, Cardiac CT in the Treatment of Acute Chest Pain; CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; CRESCENT, Computed Tomography vs Exercise Testing in Suspected Coronary Artery Disease; CT‐COMPARE, CT Coronary Angiography to Measure Plaque Reduction; CT‐STAT, Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography for Systematic Triage of Acute Chest Pain Patients to Treatment; IAEA‐SPECT/CTA, Functional compared to anatomical imaging in the initial evaluation of patients with suspected coronary artery disease; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; M‐H, Mantel–Haenszel; MI, myocardial infarction; PERFECT, Prospective First Evaluation in Chest Pain; PROMISE, Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain; PROSPECT, Prospective Randomized Outcome Trial Comparing Radionuclide Stress Myocardial Perfusion Imaging and ECG‐gated CCTA; SCOT‐HEART, Scottish Computed Tomography of the HEART

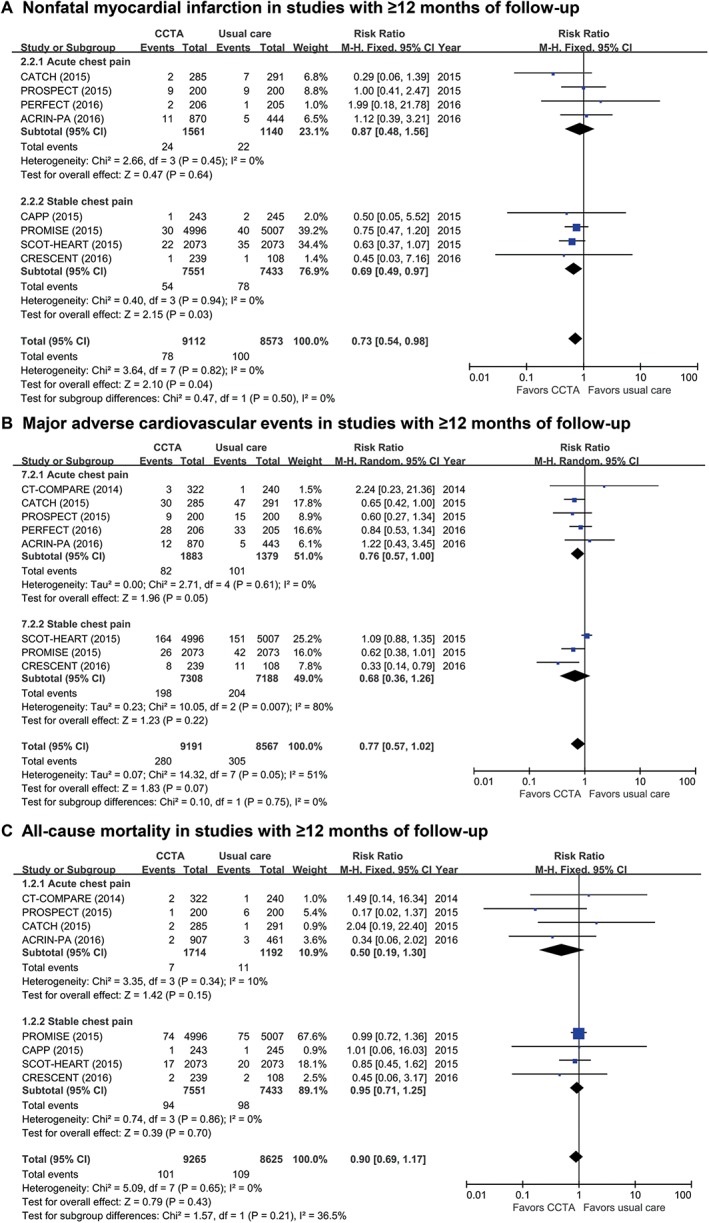

As a sensitivity analysis, we investigated the impacts of the 2 initial diagnostic strategies among the studies with a follow‐up duration ≥12 months (Figure 3). In this subgroup analysis of long‐term follow‐up studies, the use of CCTA as the initial diagnostic testing resulted in a significant reduction in nonfatal MI (RR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.54‐0.98, P = 0.04; Figure 3A) and a weak tendency for a reduced occurrence of MACE (RR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.57‐1.02, P = 0.07; Figure 3B). There was no difference in the risk of all‐cause mortality between the 2 groups (RR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.69‐1.17, P = 0.43; Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Comparison of CV events in studies with follow‐up duration ≥12 months for (A) all‐cause mortality, (B) nonfatal MI, and (C) MACE. Abbreviations: ACRIN‐PA, American College of Radiology Imaging Network–Pennsylvania; CAPP, Cardiac CT for the Assessment of Pain and Plaque; CATCH, Cardiac CT in the Treatment of Acute Chest Pain; CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; CRESCENT, Computed Tomography vs Exercise Testing in Suspected Coronary Artery Disease; CT‐COMPARE, CT Coronary Angiography to Measure Plaque Reduction; CV, cardiovascular; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; M‐H, Mantel–Haenszel; MI, myocardial infarction; PERFECT, Prospective First Evaluation in Chest Pain; PROMISE, Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain; PROSPECT, Prospective Randomized Outcome Trial Comparing Radionuclide Stress Myocardial Perfusion Imaging and ECG‐gated CCTA; SCOT‐HEART, Scottish Computed Tomography of the HEART

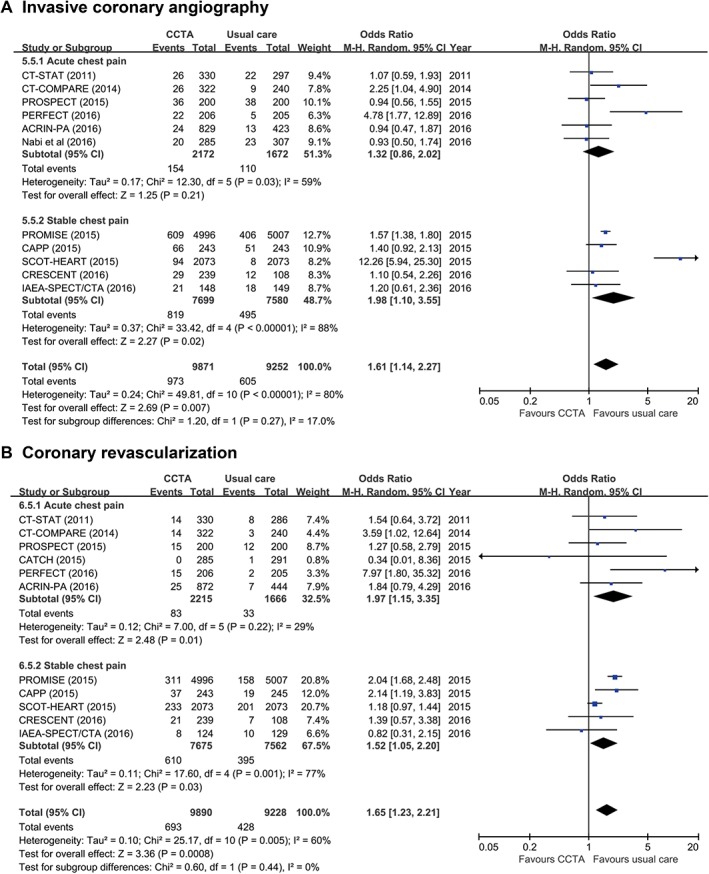

3.4. Initial diagnostic strategy and use of invasive procedures

Based on all included studies, the initial CCTA strategy resulted in a significantly more frequent use of ICA (RR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.14‐2.27, P = 0.007; Figure 4A) and coronary revascularization (RR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.23‐2.20, P = 0.0008; Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Use of invasive procedures following initial anatomical vs functional testing for (A) ICA and (B) coronary revascularization. Abbreviations: ACRIN‐PA, American College of Radiology Imaging Network–Pennsylvania; CAPP, Cardiac CT for the Assessment of Pain and Plaque; CATCH, Cardiac CT in the Treatment of Acute Chest Pain; CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; CRESCENT, Computed Tomography vs Exercise Testing in Suspected Coronary Artery Disease; CT‐COMPARE, CT Coronary Angiography to Measure Plaque Reduction; CT‐STAT, Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography for Systematic Triage of Acute Chest Pain Patients to Treatment; ICA, invasive coronary angiography; IAEA‐SPECT/CTA, Functional compared to anatomical imaging in the initial evaluation of patients with suspected coronary artery disease; M‐H, Mantel–Haenszel; PERFECT, Prospective First Evaluation in Chest Pain; PROMISE, Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain; PROSPECT, Prospective Randomized Outcome Trial Comparing Radionuclide Stress Myocardial Perfusion Imaging and ECG‐gated CCTA; SCOT‐HEART, Scottish Computed Tomography of the HEART

Similar results were observed in subgroup analyses of the RCTs with long‐term follow‐up durations (see Supporting Information, Figure S3, in the online version of this article): the use of CCTA as the initial diagnostic strategy led to significantly more frequent use of ICA (RR: 1.79, 95% CI: 1.20‐2.67, P = 0.004; see Supporting Information, Figure S3A, in the online version of this article) and coronary revascularization procedures (RR: 1.70, 95% CI: 1.24‐2.32, P = 0.0009; see Supporting Information, Figure S3B, in the online version of this article). The funnel plots suggested the presence of publication bias for ICA; however, the trim‐and‐fill analysis showed that the influence was not significant (see Supporting Information, Figures S2 and S4, in the online version of this article).

4. DISCUSSION

In this meta‐analysis, we showed that anatomical testing with CCTA as an initial diagnostic strategy reduces the risk of nonfatal MI in patients with suspected CAD, compared with the usual care, during mid‐ to long‐term follow‐up. The reduction in the risk of nonfatal MI was at the expense of increased use of ICA and coronary revascularization.

4.1. CCTA vs usual care: Comparison of longer‐term outcomes

The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology guidelines prefer the use of functional testing over the use of CCTA,1, 2 whereas the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends CCTA.9 These discrepancies between the major clinical guidelines are largely due to the different characteristics of the anatomical testing, CCTA, and the functional testing. Although use of CCTA enables an accurate anatomical diagnosis of CAD, the CCTA findings may lead to overtreatment due to the lack of functional information.25 Functional testing may reduce the unnecessary and invasive treatment through the detection of myocardial ischemia; however, the diagnostic accuracy of commonly used functional imaging methods, such as single‐photon emission computed tomography and stress echocardiography, is lower than that of CCTA.25, 26

The use of CCTA could result in increased use of medications and invasive procedures, because this test reveals the presence of coronary atherosclerosis even in the subclinical stage.27, 28 Of note, the increased use of preventive medications in patients with nonobstructive CAD detected by CCTA leads to improvements in lipid profile and blood pressure control; and, moreover, it can reduce the risk of mortality and cardiovascular events.29, 30, 31 Therefore, the clinical outcomes following CCTA should be assessed on a long‐term basis, because the prognosis can be determined by the intensified preventive medications and the increased use of ICA and coronary revascularization following anatomical testing, as well as the potential missed diagnosis by functional testing. More important, the comparative effectiveness of CCTA vs usual care needs to be assessed in randomized trials in which the initial choice of noninvasive testing determines the treatment plans.

Previous meta‐analysis reported potential benefits of CCTA in patients with stable chest pain7 or those with acute chest pain.32 Although these studies provided valuable findings about the use of CCTA,7, 8, 32 their results should be interpreted cautiously because these studies included short‐term follow‐up RCTs, such as a study by Min et al. with 2 months of follow‐up,3 the original publication of the ACRIN‐PA trial that reported outcomes of 1 month of follow‐up,14 the Better Evaluation of Acute Chest Pain with Computed Tomography Angiography (BEACON) trial with 1 month of follow‐up,4 and several cohort studies with 1 or 2 months of follow‐up duration.33, 34, 35 Considering the possible increase in the use of invasive procedures driven by CCTA results, as well as its potential benefit for prevention of future cardiovascular events, the impact of the initial diagnostic approach should be assessed on a long‐term basis.

4.2. Evidence favoring CCTA becomes clearer

Recently, 2 large RCTs reported the clinical outcomes following initial diagnostic strategies of anatomical testing vs usual care. The PROMISE trial, which randomly assigned 10 003 symptomatic patients to either CCTA or functional testing, demonstrated that the initial CCTA strategy did not reduce the composite endpoint of death, MI, hospitalization for unstable angina, or major procedural complication during 2 years of follow‐up.6 However, it should also be noted that the PROMISE trial might be underpowered because of the lower‐than‐expected event rates, and that the risk of death or nonfatal MI was lower in the CCTA group (hazard ratio for a composite of death or nonfatal MI: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.44‐1.00, P = 0.049). Another landmark trial, the SCOT‐HEART, enrolled >4000 patients with suspected CAD to assess the impact of CCTA on the diagnostic approach to suspect CAD.23 Of note, the SCOT‐HEART investigators suggested that the use of CCTA might be beneficial for the reduction in the risk of cardiovascular death and MI (RR for cardiovascular death and MI: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.38‐1.01, P = 0.0527).

In addition to the PROMISE trial and SCOT‐HEART, several previous studies observed reduced rates of nonfatal MI or cardiovascular death following a CCTA‐based strategy compared with that following usual care.13, 22 Considering these results of previous studies, as well as the findings of our meta‐analysis that showed the benefit of the CCTA‐based strategy on the risk of nonfatal MI, it appears that the use of CCTA as the initial diagnostic testing is likely to reduce fatal cardiovascular events.

4.3. Increased use of medications and invasive procedures following CCTA

Anatomical testing can reveal the presence of nonobstructive CAD that could not be detected by functional testing, and this better sensitivity may lead to increased use of preventive medications and revascularization.27, 31 Among the 6 RCTs that were included in this meta‐analysis and reported the changes in preventive medical therapies, the CAPP trial,21 the CATCH trial,13 and the SCOT‐HEART trial23 showed that the use of preventive medications significantly increased following a CCTA‐based strategy, compared with that following usual care. In the present study, we could not provide the pooled effects of diagnostic strategies on the changes in medications, due to the inconsistent definitions and endpoints regarding the medication use in these trials. However, their results are concurrent with the findings from previous studies such as the Study of Myocardial Perfusion and Coronary Anatomy Imaging Roles in Coronary Artery Disease (SPARC) registry and may provide support to the lower MI risk of the CCTA‐based strategy.27, 28, 31, 36

Our pooled analysis showed that the initial CCTA strategy resulted in a significantly increased use of ICA as well as coronary revascularization. However, it should be noted that coronary revascularization in patients with stable chest pain is not routinely recommended, and the better sensitivity of CCTA might often lead to overtreatment with coronary revascularization without improving overall prognosis.37, 38 In contrast, the most important strength of functional testing over anatomical testing is the detection of myocardial ischemia, which can guide decisions about coronary revascularization. Several previous studies also reported that revascularization in selected patients with significant ischemia documented by MPI might improve clinical outcomes.39, 40 Therefore, prospective trials are required to determine whether intensified medical therapy with or without coronary revascularization can improve outcomes in patients with stable chest pain evaluated by CCTA.

4.4. Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the included studies had various functional testing modalities. This limitation was due to differences in national healthcare systems, but this also indicates that the included studies reflect current clinical practice. Second, the PROMISE trial and the SCOT‐HEART trial enrolled markedly larger study populations than did other included studies. The larger size of these two trials could have influenced the study results. However, the exclusion of these studies did not change the heterogeneity of included studies nor the study outcomes that favor the use of a CCTA‐based strategy to achieve better clinical outcomes. Third, the interpretation of our results requires caution because of the potential publication bias. However, the trim‐and‐fill analysis showed that there was no significance influence on the study results.

5. CONCLUSION

Compared with usual care, anatomical testing with CCTA as an initial diagnostic strategy for patients with suspected CAD resulted in a lower risk of nonfatal MI and higher rates of ICA and coronary revascularization during mid‐ to long‐term follow‐up. Future trials of advanced CT technology may further demonstrate the clinical benefits of the anatomical testing strategy over usual care.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

ICH and SJC contributed equally to this work as co–first authors.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Quality assessment

(A) Risk of bias summary. (B) Risk of bias graph.

Figure S2 Funnel plots for the analysis of RCTs with follow‐up duration more than 6 months.

A, all‐cause mortality. B, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI). C, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). D, invasive coronary angiography (ICA). The funnel plot suggested the presence of publication bias. However, trim and fill analysis showed that there was no significant influence from the possible publication bias. E, coronary revascularization.

Figure S3 Comparison of the use of invasive procedures in studies with follow‐up duration more than 12 months

A, invasive coronary angiography (ICA). Although the funnel plot suggested a presence of publication bias, the trim and fill analysis showed that there was no significant influence. B, coronary revascularization.

Figure S4 Funnel plots for the analysis of RCTs with follow‐up duration more than 12 months.

A, all‐cause mortality. B, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI). C, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). D, invasive coronary angiography (ICA). The funnel plot suggested the presence of publication bias. However, trim and fill analysis showed that there was no significant influence from the possible publication bias. E, coronary revascularization.

Table S1

Hwang I‐C, Choi SJ, Choi JE, et al. Comparison of mid‐ to long‐term clinical outcomes between anatomical testing and usual care in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: A meta‐analysis of randomized trials. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:1129–1138. 10.1002/clc.22799

Funding Information

National Evidence‐based Healthcare Collaborating Agency, Republic of Korea, Grant/Award number: NECA‐C‐15‐009; This research was funded by National Evidencebased Healthcare Collaborating Agency (NECA), grant no. NECA‐C‐15‐009, Republic of Korea.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wolk MJ, Bailey SR, Doherty JU, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use CriteriaTask Force. ACCF/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2013 multimodality appropriate use criteria for the detection and risk assessment of stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:380–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology [published correction appears in Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2260–2261]. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949–3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Min JK, Koduru S, Dunning AM, et al. Coronary CT angiography versus myocardial perfusion imaging for near‐term quality of life, cost and radiation exposure: a prospective multicenter randomized pilot trial. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2012;6:274–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dedic A, Lubbers MM, Schaap J, et al. Coronary CT angiography for suspected ACS in the era of high‐sensitivity troponins: randomized multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bertoldi EG, Stella SF, Rohde LE, et al. Long‐term cost‐effectiveness of diagnostic tests for assessing stable chest pain: modeled analysis of anatomical and functional strategies. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39:249–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, et al; PROMISE Investigators. Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1291–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bittencourt MS, Hulten EA, Murthy VL, et al. Clinical outcomes after evaluation of stable chest pain by coronary computed tomographic angiography versus usual care: a meta‐analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:e004419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nudi F, Lotrionte M, Biasucci LM, et al. Comparative safety and effectiveness of coronary computed tomography: systematic review and meta‐analysis including 11 randomized controlled trials and 19 957 patients. Int J Cardiol. 2016;222:352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Skinner JS, Smeeth L, Kendall JM, et al. Chest Pain Guideline Development Group. NICE guidance. Chest pain of recent onset: assessment and diagnosis of recent onset chest pain or discomfort of suspected cardiac origin. Heart. 2010;96:974–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269, W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel‐plot‐based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta‐analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Linde JJ, Kofoed KF, Sørgaard M, et al. Cardiac computed tomography guided treatment strategy in patients with recent acute‐onset chest pain: results from the randomised, controlled trial: Cardiac CT in the Treatment of Acute Chest Pain (CATCH). Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:5257–5262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Linde JJ, Hove JD, Sørgaard M, et al. Long‐term clinical impact of coronary CT angiography in patients with recent acute‐onset chest pain: the randomized controlled CATCH trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1404–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Litt HI, Gatsonis C, Snyder B, et al. CT angiography for safe discharge of patients with possible acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1393–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hollander JE, Gatsonis C, Greco EM, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography versus traditional care: comparison of one‐year outcomes and resource use. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:460.e1–468.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goldstein JA, Chinnaiyan KM, Abidov A, et al; CT‐STAT Investigators . The CT‐STAT (Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography for Systematic Triage of Acute Chest Pain Patients to Treatment) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1414–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hamilton‐Craig C, Fifoot A, Hansen M, et al. Diagnostic performance and cost of CT angiography versus stress ECG—a randomized prospective study of suspected acute coronary syndrome chest pain in the emergency department (CT‐COMPARE). Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:867–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Levsky JM, Spevack DM, Travin MI, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography versus radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with chest pain admitted to telemetry: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:174–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uretsky S, Argulian E, Supariwala A, et al. Comparative effectiveness of coronary CT angiography vs stress cardiac imaging in patients following hospital admission for chest pain work‐up: the Prospective First Evaluation in Chest Pain (PERFECT) trial. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24:1267–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nabi F, Kassi M, Muhyieddeen K, et al. Optimizing evaluation of patients with low‐to‐intermediate‐risk acute chest pain: a randomized study comparing stress myocardial perfusion tomography incorporating stress‐only imaging versus cardiac CT. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McKavanagh P, Lusk L, Ball PA, et al. A comparison of cardiac computerized tomography and exercise stress electrocardiogram test for the investigation of stable chest pain: the clinical results of the CAPP randomized prospective trial. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lubbers M, Dedic A, Coenen A, et al. Calcium imaging and selective computed tomography angiography in comparison to functional testing for suspected coronary artery disease: the multicentre, randomized CRESCENT trial. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1232–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Investigators SCOT‐HEART. CT coronary angiography in patients with suspected angina due to coronary heart disease (SCOT‐HEART): an open‐label, parallel‐group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2383–2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Karthikeyan G, Guzic Salobir B, Jug B, et al. Functional compared to anatomical imaging in the initial evaluation of patients with suspected coronary artery disease: an international, multi‐center, randomized controlled trial (IAEA‐SPECT/CTA study). J Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24:507–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marwick TH, Cho I, ó Hartaigh B, et al. Finding the gatekeeper to the cardiac catheterization laboratory: coronary CT angiography or stress testing? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2747–2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Danad I, Szymonifka J, Twisk JWR, et al. Diagnostic performance of cardiac imaging methods to diagnose ischaemia‐causing coronary artery disease when directly compared with fractional flow reserve as a reference standard: a meta‐analysis. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:991–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McEvoy JW, Blaha MJ, Nasir K, et al. Impact of coronary computed tomographic angiography results on patient and physician behavior in a low‐risk population. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1260–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hachamovitch R, Nutter B, Hlatky MA, et al; SPARC Investigators. Patient management after noninvasive cardiac imaging results from SPARC (Study of Myocardial Perfusion and Coronary Anatomy Imaging Roles in Coronary Artery Disease). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:462–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hwang IC, Jeon JY, Kim Y, et al. Statin therapy is associated with lower all‐cause mortality in patients with non‐obstructive coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2015;239:335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hwang IC, Jeon JY, Kim Y, et al. Association between aspirin therapy and clinical outcomes in patients with non‐obstructive coronary artery disease: a cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheezum MK, Hulten EA, Smith RM, et al. Changes in preventive medical therapies and CV risk factors after CT angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:574–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Romero J, Husain SA, Holmes AA, et al. Non‐invasive assessment of low risk acute chest pain in the emergency department: a comparative meta‐analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cardiol. 2015;187:565–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gallagher MJ, Ross MA, Raff GL, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of 64‐slice computed tomography coronary angiography compared with stress nuclear imaging in emergency department low‐risk chest pain patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:125–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hollander JE, Chang AM, Shofer FS, et al. Coronary computed tomographic angiography for rapid discharge of low‐risk patients with potential acute coronary syndromes. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hollander JE, Litt HI, Chase M, et al. Computed tomography coronary angiography for rapid disposition of low‐risk emergency department patients with chest pain syndromes. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:112–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ladapo JA, Hoffmann U, Lee KL, et al. Changes in medical therapy and lifestyle after anatomical or functional testing for coronary artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boden WE, O'Rourke RA, Teo KK, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pursnani S, Korley F, Gopaul R, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus optimal medical therapy in stable coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:476–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hachamovitch R, Rozanski A, Shaw LJ, et al. Impact of ischaemia and scar on the therapeutic benefit derived from myocardial revascularization vs. medical therapy among patients undergoing stress‐rest myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1012–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nudi F, Di Belardino N, Versaci F, et al. Impact of coronary revascularization vs medical therapy on ischemia among stable patients with or suspected coronary artery disease undergoing serial myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016. May 26. [Epub ahead of print] 10.1007/s12350-016-0504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Quality assessment

(A) Risk of bias summary. (B) Risk of bias graph.

Figure S2 Funnel plots for the analysis of RCTs with follow‐up duration more than 6 months.

A, all‐cause mortality. B, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI). C, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). D, invasive coronary angiography (ICA). The funnel plot suggested the presence of publication bias. However, trim and fill analysis showed that there was no significant influence from the possible publication bias. E, coronary revascularization.

Figure S3 Comparison of the use of invasive procedures in studies with follow‐up duration more than 12 months

A, invasive coronary angiography (ICA). Although the funnel plot suggested a presence of publication bias, the trim and fill analysis showed that there was no significant influence. B, coronary revascularization.

Figure S4 Funnel plots for the analysis of RCTs with follow‐up duration more than 12 months.

A, all‐cause mortality. B, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI). C, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). D, invasive coronary angiography (ICA). The funnel plot suggested the presence of publication bias. However, trim and fill analysis showed that there was no significant influence from the possible publication bias. E, coronary revascularization.

Table S1