Watch a video presentation of this article

Watch the interview with the author

Abbreviations

- CLDQ

chronic liver disease questionnaire

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HRQOL

health‐related quality of life

- LDQOL

Short Form Liver Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire

- LT

liver transplant

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- PRO

patient‐reported outcome

Introduction

Health‐related quality of life (HRQOL) represents an important outcome from a patient's perspective. HRQOL falls under the broader category of Quality‐of‐Life (QOL) which accounts for the influence of health, environment, freedom, economy, as well as aspects of one's culture, values, and spirituality on an individual's well‐being.1 HRQOL is a multidimensional concept that includes self‐reported measures of one's physical and mental health as well as their social well‐being (the ability to be socially active).2

More recently, the term patient‐reported outcomes (PROs) have gained popularity to also reflect patients’ experiences with their disease and its treatment. Although the concepts of HRQOL and PROs are used interchangeably, PROs include HRQOL as well as other outcomes reported by and important to patients such as satisfaction, decision‐making preferences, and so forth.3 Because HRQOL cannot be measured directly, they are estimated using validated instruments or questionnaires. In general, HRQOL tools or instruments are divided into general measures (generic instruments) and disease‐specific instruments.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Table 1 describes some of the most commonly used generic and disease‐specific HRQOL instruments in patients with chronic liver disease and cirrhosis.

Table 1.

Common Tools Used in Measuring Patients with Cirrhosis HRQOL

| Name of Tool | Health Domains Measured | No of Items | Strengths and Limitations | Generic or Disease‐Specific | How Administered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Short Form-36 (SF‐36)

http://www.sf‐36.org/tools/sf36.shtml#vers2 |

‐ 8 domains measuring functional health and well‐being: general health, vitality, role emotional, role physical, social well‐being, mental health, and physical functioning ‐ 2 summary scales [Physical composite and mental composite cores] |

36 items |

‐ One of the most widely used tool worldwide ‐ Established population norms for comparison ‐ Generic, not disease‐specific ‐ Asks for a recall of how the patient is feeling over past week/month |

Generic–general health | Self‐administered or can be done in person or over the telephone. Takes 5 to 10 minutes to complete. |

|

Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) also the SIP‐68

http://www.outcomes‐trust.org/instruments.htm http://www.scireproject.com/outcome‐measures/sickness‐impact‐profile‐68‐SIP‐68 |

‐ Investigates a change in behavior as a consequence of illness ‐ Covers 12 categories of activities of daily living: sleep and rest, eating, work, home management, recreation and pastimes, ambulation, mobility, body care and movement, social interaction, alertness behavior, emotional behavior, and communication |

136 items/68 items |

‐ Items are scored on a numeric scale with higher scores reflecting greater dysfunction ‐ An aggregate psychosocial score is derived from 4 categories and an aggregate physical score from 3 categories |

Generic–general health | Paper and pencil, takes approximately 30–40 minutes for the full survey and 15–20 minutes for the SIP 68. |

|

Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ)

https://www.cldq.org/ |

‐ Measures 4 domains: activity and energy, emotional, worry, systemic ‐ Assesses HRQOL in chronic liver disease and specifically in patients with HCV |

29 items Higher scores mean better HRQoL |

‐ Widely used and validated tool ‐ Translated into many languages – see website |

Disease‐Specific | Paper and pencil, self‐administered |

|

Post–Liver Transplant Quality of Life (PLTQ)

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/lt.22267/full |

‐ 8 domains which include: emotional function, worry, medications, physical function, healthcare, graft rejection concern, financial, pain |

‐ 32 items ‐ First 28 items scored on a scale of 1–7 ‐ higher scores mean better HRQoL |

‐ Stable over time ‐ Relatively new measurement |

Liver Transplantation | Self‐administered |

|

Liver Disease Quality of Life (LDQOL) – Short Form

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11151892 |

‐ 9 domains ‐ Measures symptoms of liver disease, and the effects of liver disease ‐ Shown to correlate highly with SF‐36 scores, symptom severity, disability days, and global health |

36 items | ‐ Translated into several languages, to include Spanish and Korean | Disease‐Specific | Self‐administered |

|

Hepatitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (HQLQV2)

http://www.qualitymetric.com/whatwedo/diseasespecifichealthsurveys/hepatitisqualityoflifequestionnairehqlqv2/tabid/193/default.aspx |

‐ 2‐part survey to assess functional health and well‐being of patients with chronic hepatitis C ‐ Includes the SF‐36v2 Health Survey (36 questions) and 15 additional questions which measure generic health concepts relevant to assessing the impact of hepatitis (health distress, positive well‐being) and disease‐specific concepts (e.g., Hepatitis‐specific functional limitations, hepatitis‐specific distress) |

51 items | Is available in a fixed form or interview (telephone/face‐to‐face) format. + | Disease‐Specific | It can be administered in clinical settings, at home, or in other locations |

|

Liver Disease Symptom Index 2.0 (LDSI 2.0)

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15503842 |

Measures symptom severity and symptom hindrance in the past week | 18 items |

‐ Measures symptom severity and symptom hindrance in the past week ‐ Considered an additive tool when researching HRQOL with the liver disease population ‐ Responses are on a 5‐point scale from “not at all hindered” to “hindered a high extent” ‐ Translated into several languages |

Disease‐Specific | Self‐administered |

|

Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7636775 |

Measures that cover: general fatigue, physical, fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced motivation, and reduced activity |

‐ 20 items ‐ Uses a 5‐point Likert scale from 1–5 (yes that is true to no that is not true). ‐ Higher scores mean less fatigue |

Valid and reliable tool | Generic for fatigue | Self‐report |

|

Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory – Short Form (MFSI‐SF)

http://www.cas.usf.edu/∼jacobsen/handout.fsi&mfsi.pdf |

Assesses global, somatic, affective, cognitive, and behavioral manifestations of fatigue | 30 items |

‐ Shorter version of the original 83 items (Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory) ‐ Takes less time but maintains the integrity of original survey |

Generic | Self‐report |

|

Quality Well‐Being Scale

http://www.healthmeasurement.org/pub_pdfs/_questionnaire_qwb‐sa,%20version%201.04.pdf |

‐ Combines preference‐weighted values for symptoms and functioning ‐ Symptoms are assessed by questions that ask about the presence or absence of different symptoms or conditions (yes or no) ‐ Functioning is assessed by a series of questions designed to record functional limitations over the previous 3 days, within 3 separate domains (mobility, physical activity, and social activity). ‐ The 4 domain scores are combined into a total score that provides a numerical point‐in‐time expression of well‐being that ranges from zero (0) for death to one (1.0) for asymptomatic optimum functioning |

3 pages, 58 questions Asks for responses from the past 3 days |

‐ Can be self‐administered, used in a face‐to‐face interview, answered by proxy, and administered online ‐ Can be used to obtain QUALYs/health utility scores |

Generic | Self‐administered (see strengths and limitations) |

|

Health Utilities Index (HUI)

www.researchgate.net/.utility.health_utilities_index./d9 |

A generic multi‐attribute preference based measure of health status and HRQoL |

‐ HU13 consists of 8 attributes/dimensions: vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion, cognition, and pain ‐ Scores range from highly impaired to normal |

‐ Can be used in clinical studies, population‐based surveys, in the estimation of quality‐adjusted life years, and economic analysis | Generic | Self‐administered, then scored by investigator |

| Short Form 6D (SF‐6D) | To calculate the true value of a treatment, the scores from the SF‐36v2 or the SF‐12v2 Health Surveys can be converted into a utility index, called the SF‐6D, which considers not only how many years a medical intervention can add to a patient's life, but also the quality of that life |

‐ Get a better understanding of a patient's real preference for a treatment ‐ Helps select the best course of action for a patient ‐ Compares 2 interventions based on Quality‐Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) and cost ‐ Assesses the cost‐effectiveness of a medical product, procedure, or health and wellness program ‐ Allocates health care resources most efficiently |

Generic for quality of years added. Used for the economic impact of a disease. | The SF form is self‐administered, then the investigator will convert the scores to a utility score | |

|

EURO‐QOL (EQ‐5D)

www.euroqol.org |

A standardized instrument for use as a measure of health outcome |

‐ Measures 5 dimensions: mobility, self‐care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression ‐ Each dimension has 3 levels: no problems, some problems, extreme problems ‐ Incorporates a visual analog scale to obtain the respondent's self‐rated health on a vertical, visual analogue scale where the endpoints are labelled “Best imaginable health state” and “Worst imaginable health state” |

‐ Cognitively simple, taking only a few minutes to complete ‐ Instructions to respondents are included in the questionnaire |

Generic | Self‐completion by respondents and is ideally suited for use in postal surveys, in clinics, and face‐to‐face interviews |

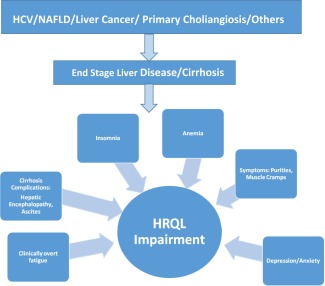

HRQOL in Patients with End‐Stage Liver Disease

Most patients with chronic liver disease report significant impairment of their HRQOL (Fig. 1).6, 7 Although this impairment is documented for patients with different types of chronic liver disease, patients with viral hepatitis C (HCV), primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) seem to have more impairment.2 In fact, several recent studies have reported that patients with HCV and PBC have significantly reduced HRQOL due to fatigue (both) and depression (HCV). Although patients with PBC have more physical impairment, those with HCV infection have more mental health impairment.6, 7, 8

Figure 1.

Factors affecting HRQOL in end‐stage liver disease.

As patients develop advanced liver disease, manifested by the development of compensated cirrhosis, HRQOL impairment becomes more prominent.4 Although some of the factors affecting HRQOL are related to a patient's clinical characteristics (age, gender, comorbidities), others are related to cirrhosis‐specific complications such as the development of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 In fact in one large study, Marchesini and colleagues assessed HRQOL in patients with cirrhosis using two generic HRQOL tools (SF‐36 and the Nottingham Health Profile).11 Findings from the study suggested that the cirrhotic group had significantly lower HRQOL than the population norms as a result of cirrhosis‐associated muscle cramps and pruritus. These symptoms plus other complications of cirrhosis profoundly impacted patient well‐being, which was not captured by markers of disease severity such as the Child‐Pugh classification.11 Other studies have also confirmed these results.

As noted previously, complications of cirrhosis, namely hepatic encephalopathy and ascites, have been found to have their own unique impact on HRQOL.10, 13 In fact, covert hepatic encephalopathy can affect HRQOL of cirrhotic patients when they appear to be functioning normally in their daily activities.13 There is also evidence that effective treatment of encephalopathy can improve HRQOL scores.9, 14 In one such study, investigators used the chronic liver disease questionnaire (CLDQ) to assess HRQOL in patients with overt hepatic encephalopathy who were being treated with rifaxamin. The study results showed that rifaxamin significantly improved CLDQ scores and patients’ HRQOL. A very interesting finding was that within the group that had an episode of breakthrough hepatic encephalopathy, there was a decrease in HRQOL scores prior to the appearance of hepatic encephalopathy. The authors concluded that a decrease in HRQOL scores in patients with a history of hepatic encephalopathy can signal the onset of a new episode of hepatic encephalopathy. These data suggest that tracking HRQOL may be helpful in the management of patients with hepatic encephalopathy.14

Ascites has been found to be an independent predictor of severe impairment of HRQOL and mortality.7, 11, 12, 15 In a study by Kenwal and associates, where HRQOL of 156 cirrhotic patients awaiting liver transplant (LT) was assessed using the Short Form Liver Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire (LDQOL), results indicated that moderate to severe ascites, high MELD (Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease) score and low LDQOL were all associated with mortality, thus confirming results seen in other chronic diseases.12 However, treatment of ascites has been found to have a beneficial impact on the patient's experience, positively impacting a patient's HRQOL especially if they receive an LT.10

In general, patients listed for LT have very advanced liver disease and suffer tremendous impairment of their HRQOL.17, 18 Because LT is the ultimate treatment for advanced cirrhosis, it leads to improvement not only in life expectancy but also patients’ HRQOL. In fact, this improvement in HRQOL after LT is so profound that it can easily be captured with any HRQOL instrument.17, 18 In one study, the authors determined that patients’ HRQOL scores following LT significantly improved and was associated with improved resource utilization. Further, after transplantation, these patients’ mental health scores were the same or higher than the population norms, whereas their physical functioning scores rose significantly but did not surpass the population norms.17 It is important to note that long‐term nutritional support has been found to be key for LT patients to obtain an optimal level of physical functioning and thus an increase in their HRQOL.19

Conclusions

HRQOL in patients suffering from cirrhosis is significantly impaired when compared to patients without liver disease. Many HRQOL tools have been used to measure the impact of cirrhosis on HRQOL. The most commonly used tools include the CLDQ, the SF‐36, and the LDQOL. HRQOL is influenced by the type of liver disease and the complications arising from cirrhosis. The net overall effect is significant impairment of HRQOL, whether due to mental impairment or limitations affecting patients’ ability to perform an activity of daily living. Collecting information on HRQOL is helpful in assessing the total impact of liver disease on patients’ well‐being and guiding and evaluating the impact of treatment not only on clinical outcomes of cirrhosis but also PROs such as HRQOL.

Important Issues to Address

The most important issues for clinicians treating patients with cirrhosis is knowing that not only is their patient's prognosis and survival negatively impacted by cirrhosis, but that the number of symptoms (fatigue, muscle cramps) and complications of cirrhosis (hepatic encephalopathy, ascites) have a tremendous negative impact on the patient's experience. If clinicians and clinical investigators only focus on clinical outcomes, they will ignore another aspect of patient experience (that is, PRO) which is of utmost importance to patients. Therefore, treatment of liver disease and cirrhosis should focus not only on improving clinical outcomes but also on improvement of PROs. It is only with this comprehensive approach to patients with cirrhosis that we can capture the full impact of their disease and its treatment. Therefore, we highly recommend that hepatologists become familiar with PRO assessment, which will complement their clinical expertise to provide interventions that will optimize their patient's prognosis and PROs.19

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL). http://www.cdc.gov/HRQoL/concept.htm. Last accessed 27 February 2014.

- 2. van der Plas SM, Hansen BE, de Boer JB, Stijnen T, Passchier J, de Man RA, et al. Generic and disease‐specific health related quality of life of liver patients with various aetiologies: a survey. Qual Life Res 2007;16:375‐388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gnanasakthy A, Mordin M, Clark M, DeMuro C, Fehnel S, Copley‐Merriman C. A review of patient‐reported outcome labels in the United States: 2006 to 2010. Value Health 2012;15:437‐442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Younossi ZM, Boparai N, Price LL, Kiwi ML, McCormick M, Guyatt G. Health‐related quality of life in chronic liver disease: the impact of type and severity of disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:2199‐2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwi M, Boparai N, King D. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut 1999;45:295‐300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gutteling JJ, de Man RA, van der Plas SM, Schalm SW, Busschbach JJ, Darlington AS. Determinants of quality of life in chronic liver patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;23:1629‐1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Afendy A, Kallman JB, Stepanova M, Younoszai Z, Aquino RD, Bianchi G, et al. Predictors of health‐related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:469‐476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sobhonslidsuk A, Silpakit C, Kongsakon R, Satitpornkul P, Sripetch C, Khanthavit A. Factors influencing health‐related quality of life in chronic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:7786‐7791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Loria A, Escheik C, Gerber NL, Younossi ZM. Quality of life in cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2013;15:301. doi: 10.1007/s11894-012-0301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Les I, Doval E, Flavià M, Jacas C, Cárdenas G, Esteban R, et al. Quality of life in cirrhosis is related to potentially treatable factors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;22:221‐227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marchesini G, Bianchi G, Amodio P, Salerno F, Merli M, Panella C, et al; Italian Study Group for Quality of Life in Cirrhosis . Factors associated with poor health‐related quality of life of patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2001;120:170‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kanwal F, Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Zeringue A, Durazo F, Han SB, et al. Health‐related quality of life predicts mortality in patients with advanced chronic liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:793‐799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arguedas MR, DeLawrence TG, McGuire BM. Influence of hepatic encephalopathy on health‐related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 2003;48:1622‐1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sanyal A, Younossi ZM, Bass NM, Mullen KD, Poordad F, Brown RS, et al. Randomised clinical trial: rifaximin improves health‐related quality of life in cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy ‐ a double‐blind placebo‐controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:853‐861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Solà E, Watson H, Graupera I, Turón F, Barreto R, Rodríguez E, et al. Factors related to quality of life in patients with cirrhosis and ascites: relevance of serum sodium concentration and leg edema. J Hepatol 2012;57:1199‐1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Younossi ZM, Kiwi ML, Boparai N, Price LL, Guyatt G. Cholestatic liver diseases and health‐related quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:497‐502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Younossi ZM, McCormick M, Price LL, Boparai N, Farquhar L, Henderson JM, et al. Impact of liver transplantation on health‐related quality of life. Liver Transpl 2000;6:779‐783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Togashi J, Sugawara Y, Akamatsu N, Tamura S, Yamashiki N, Kaneko J, et al. Quality of life after adult living donor liver transplantation: A longitudinal prospective follow‐up study. Hepatol Res 2013;43:1052‐1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Urano E, Yamanaka‐Okumura H, Teramoto A, Sugihara K, Morine Y, Imura S, et al. Pre‐ and postoperative nutritional assessment and health‐related quality of life in recipients of living donor liver transplantation, Hepatol Res 2014;44:1102‐1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gola A, Davis S, Greenslade L, Hopkins K, Low J, Marshall A, et al. Economic analysis of costs for patients with end stage liver disease over the last year of life. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:110. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000838.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]