Watch a video presentation of this article

Watch the interview with the author

Patients with irreversible, advanced liver disease and their families live with a complex and challenging condition that follows a highly unpredictable illness trajectory. As their health deteriorates, patients often experience debilitating symptoms, psychological stress, family worries, financial problems, social stigma, and existential distress. In addition, there is the ever‐present threat of acute, life‐threatening complications.1 Treatment of these episodic decompensations leads to recurrent hospitalizations and difficult decisions about how and where a patient might choose to die. Liver transplantation can be life‐saving, but patients have to be “sick enough to die” to be accepted onto a transplant list.2 Then, patients and their families have to cope with the uncertainty of whether they will ever be able to receive a transplant and live, or will in fact die. So, how do we handle these most challenging end‐of‐life decisions in ways that ensure our patients receive high‐quality, therapeutic interventions alongside holistic palliative care and also pay attention to evolving patient and family goals and values?

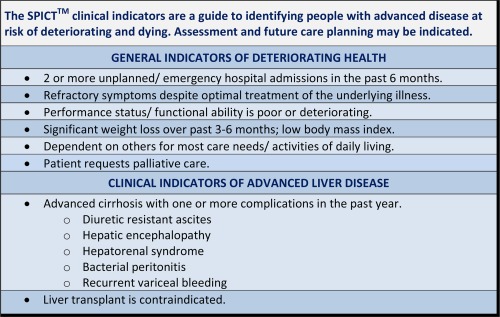

Timely future care planning is particularly important when patients may die rapidly during a sudden episode of decompensation or lose decision‐making capacity due to encephalopathy or severe illness. Waiting until all treatment options have been tried and the patient is close to death is “prognostic paralysis”; a common but avoidable situation. The first step is earlier identification of patients whose health is deteriorating such that they are at risk of dying within the foreseeable future. Several approaches have been recommended. The simplest is the intuitive “Surprise Question” where a clinician or team ask themselves if it would be a surprise if this patient were to die in the next 6–12 months.3 This works best in illnesses with fairly predictable trajectories such as some types of cancer, but much less well in advanced liver disease because of its inherently unpredictable course. Mortality risk prediction tools, such as the Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease scoring system, are used widely in deciding about transplant eligibility and indicate a short life expectancy.4 Intractable symptoms, signs of advanced cirrhosis such as encephalopathy or recurrent variceal bleeds, and hepatocellular carcinoma are clinical indicators for a palliative care needs assessment. Starting to talk about planning ahead can happen alongside other aspects of holistic care such as symptom control, psychological support, and family care. People with advanced liver disease may have a reasonable performance status between episodes of decompensation, so this tends to be less helpful as an indicator than recurrent hospitalizations. Comorbidities add to the illness burden and should also prompt the early introduction of a palliative care approach. Using disease‐specific indicators and general clinical indicators of deteriorating health and risk of dying helps clinicians identify patients with advanced liver disease who could benefit from further assessment and conversations about what matters to them as their health deteriorates (see “Clinical Indicators” in Fig. 1).5

Figure 1.

Clinical indicators for supportive and palliative care needs assessment in people with advanced liver disease.

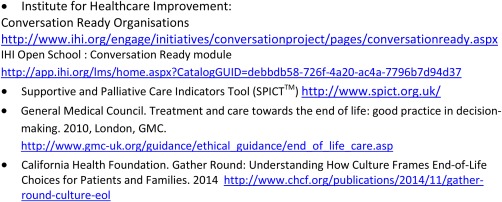

However, identifying patients with irreversible liver disease whose priorities may be changing is only of value if the clinicians caring for these patients are able to discuss this with them, and then integrate excellent disease‐focused management with a palliative care approach that gives as much priority to quality of life and dying as it does longevity. Some liver specialists will be comfortable with this wider role. Others will prefer a shared care model working more closely with palliative care specialists or family physicians. Maintaining well‐established therapeutic relationships between patients, families, and the hepatology specialist team is important for continuity and quality of care. Transfer to hospice while hospitalization for acute complications is still indicated and wanted by patients may not be appropriate at the stage when conversations about deteriorating health should begin. Liver specialists are usually best placed to identify patients but are then faced with the challenge of having to find sensitive and effective ways to broach the subjects of palliative care and future care planning. The strong association of palliative care with cancer and death in the minds of patients, families, and professionals means everyone needs to talk explicitly about what benefits a palliative care approach offers and be clear that it does not equate with treatment withdrawal or imminent death. A model of shared care between oncology and palliative care in lung cancer care successfully helped patients accept a poor outcome while living well in the present.6 Figure 2 lists some useful online resourse to assist you in helping your patients facing end of life decisions. Figure 3 provides an outline guide for framing conversations about planning for the future when prognosis is poor.

Figure 2.

Online resources.

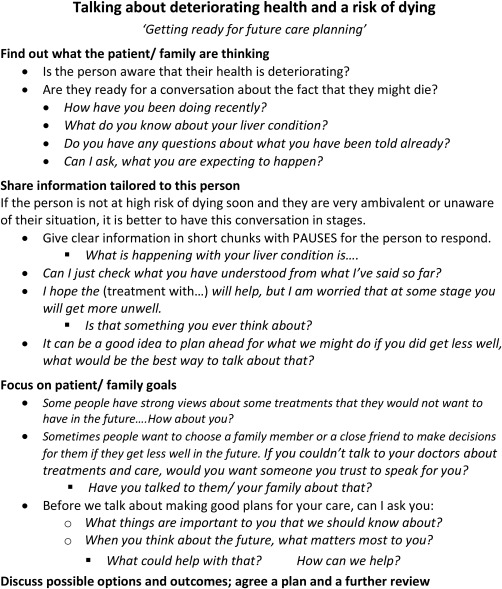

Figure 3.

Conversation guide.

In some countries, advance care planning has been advocated extensively as the best way to enable patients with advanced life‐limiting illnesses to express their wishes and preferences for future care, particularly with respect to hospitalization and escalation to intensive care. Campaigns to promote more open dialogue about death and dying within families and in society more generally are part of these initiatives. This has enabled some people to have good conversations with those close to them, make clear advance statements about treatments and care they would not want and nominate a trusted family member or friend as their surrogate decision‐maker in the event of loss of capacity. However, there are many reasons for patients not choosing or being able to plan ahead in this way. People with liver disease can have complex family, social, and health problems that limit their ability to plan ahead at all, even without the additional barriers that result from having such an unpredictable future. Helping people prepare for the difficult decisions ahead may be more effective and acceptable.7

There is a pressing need to encourage patients with advanced liver disease, their families, and the professionals caring for them to engage in meaningful conversations about deteriorating health, death, and dying. Evidence is emerging about better ways to approach these difficult topics that help people to anticipate and plan for getting less well while at the same time remaining hopeful that they can continue to do the things that are important to them.8, 9 Talking sooner rather than later about “What might happen if…” is both possible and empowering.10

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Hope AA, Morrison SR. Integrating palliative care with chronic liver disease care. J Palliat Care 2011;27:20‐27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Larson AM, Curtis JR. Integrating palliative care for liver transplant candidates. JAMA 2006;295:2168‐2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lynn J. Perspectives on care at the close of life. Serving patients who may die soon and their families: The role of hospice and other services. JAMA 2001;285:925‐932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. D'Amico G, Garcia‐Tsao G, Pagliaro I. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol 2006;44:217‐231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Highet G, Crawford D, Murray SA, Boyd K. Development and evaluation of the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT): a mixed‐methods study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014;4:285‐290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jackson VA, Jacobsen J, Greer JA, Pirl W, Temel JS, Back AL. The cultivation of prognostic awareness through the provision of early palliative care in the ambulatory setting: a communication guide. J Palliat Med 2013;16:894‐900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end‐of‐life decision making. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:256‐261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abdul‐Razzak A, You J, Sherifali D, Simon J, Brazil K. ‘Conditional candour’ and ‘knowing me’: an interpretive description study on patient preferences for physician behaviours during end‐of‐life communication. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Parry R, Land V, Seymour J. How to communicate with patients about future illness progression and end of life care: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014;4:331‐341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Workman SR. Never say die?--as treatments fail doctors’ words must not. Int J Clin Pract 2011;65:117‐119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]