Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relation between preterm birth (gestational age <37 weeks) and risk of CKD from childhood into mid-adulthood.

Design

National cohort study.

Setting

Sweden.

Participants

4 186 615 singleton live births in Sweden during 1973-2014.

Exposures

Gestational age at birth, identified from nationwide birth records in the Swedish birth registry.

Main outcome measures

CKD, identified from nationwide inpatient and outpatient diagnoses through 2015 (maximum age 43 years). Cox regression was used to examine gestational age at birth and risk of CKD while adjusting for potential confounders, and co-sibling analyses assessed the influence of unmeasured shared familial (genetic or environmental) factors.

Results

4305 (0.1%) participants had a diagnosis of CKD during 87.0 million person years of follow-up. Preterm birth and extremely preterm birth (<28 weeks) were associated with nearly twofold and threefold risks of CKD, respectively, from birth into mid-adulthood (adjusted hazard ratio 1.94, 95% confidence interval 1.74 to 2.16; P<0.001; 3.01, 1.67 to 5.45; P<0.001). An increased risk was observed even among those born at early term (37-38 weeks) (1.30, 1.20 to 1.40; P<0.001). The association between preterm birth and CKD was strongest at ages 0-9 years (5.09, 4.11 to 6.31; P<0.001), then weakened but remained increased at ages 10-19 years (1.97, 1.57 to 2.49; P<0.001) and 20-43 years (1.34, 1.15 to 1.57; P<0.001). These associations affected both males and females and did not seem to be related to shared genetic or environmental factors in families.

Conclusions

Preterm and early term birth are strong risk factors for the development of CKD from childhood into mid-adulthood. People born prematurely need long term follow-up for monitoring and preventive actions to preserve renal function across the life course.

Introduction

Preterm birth (<37 gestational weeks) interrupts the development and maturation of the kidneys during a critical growth period. The third trimester of pregnancy is the most active period of fetal nephrogenesis, during which more than 60% of nephrons are formed.1 2 Interruption of this process results in a lower nephron endowment that is lifelong.3 4 Lower nephron number has been associated with the development of hypertension and progressive kidney disease later in life.5 6 7 8 We hypothesized that preterm birth, through its effects on lower nephron endowment, leads to a persistent increased risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) into adulthood.

Despite the known effects of preterm birth on renal development, few studies have examined preterm birth in relation to subsequent risk of CKD. Low birth weight (<2500 g) has been linked to a higher risk of CKD in childhood and adulthood, but most studies have not examined gestational age at birth.9 Preterm birth is a known risk factor for neonatal acute kidney injury,10 11 which has been associated with an increased risk of CKD later in childhood.12 13 14 A previous cohort study reported that preterm birth was associated with a non-significantly increased risk of end stage renal disease at ages up to 42 years, but did not examine narrower gestational age groups or risk of CKD (including earlier and end stage disease).15 The long term risks of CKD in adults who were born prematurely remain unclear. Because of considerable advances in neonatal and pediatric treatment, more than 95% of people born preterm now survive into adulthood.16 17 Consequently, it is imperative to understand the long term risks of CKD to guide monitoring and preventive actions to preserve renal function across the lifespan.

To tackle these knowledge gaps, we conducted a national cohort study of more than four million people in Sweden to examine preterm birth in relation to the long term risks of CKD. We determined the population based risk estimates for CKD from childhood into mid-adulthood associated with gestational age at birth, assessed whether these associations vary according to sex or fetal growth, and in co-sibling analyses explored the potential influence of shared familial (genetic or environmental) factors. The results will help guide long term surveillance for early detection and prevention of kidney disease in children and adults who were born preterm.

Methods

Study population

The Swedish birth registry contains prenatal and birth information for nearly all births in Sweden since 1973.18 Using this registry, we identified 4 195 249 singleton live births during 1973-2014. Given the higher prevalence of preterm birth and its different underlying causes among multiple births we chose singleton births to improve internal comparability. We excluded 8634 (0.2%) births that had missing information for gestational age, leaving 4 186 615 births (99.8% of the original cohort) for inclusion in the study.

Ascertainment of gestational age at birth and CKD

Gestational age at birth was identified from the Swedish birth registry based on maternal report of last menstrual period in the 1970s and ultrasound estimation in the 1980s and later. We examined this alternatively as a continuous variable or categorical variable with six groups: extremely preterm (22-27 weeks), very preterm (28-33 weeks), late preterm (34-36 weeks), early term (37-38 weeks), full term (39-41 weeks, reference group), and post-term (≥42 weeks). In addition, we combined the first three groups to provide summary estimates for preterm birth (<37 weeks).

The study cohort was followed-up for the earliest diagnosis of CKD from birth to 31 December 2015 (maximum age 43 years). We identified CKD using ICD (international classification of diseases, ninth and 10th revisions) codes from all primary and secondary diagnoses in the Swedish hospital and outpatient registries (ICD-9 code 585 during 1987-96, and ICD-10 code N18 during 1997-2015). The Swedish hospital registry contains all primary and secondary hospital discharge diagnoses from six populous counties in southern Sweden starting in 1964 and with nationwide coverage starting in 1987; and the Swedish outpatient registry contains outpatient diagnoses from all specialty clinics nationwide starting in 2001. CKD had no specific ICD codes before 1987; to assess the effects on our results, we carried out sensitivity analyses after restricting to those born in 1987 or later. In addition, we examined end stage renal disease (ICD-10 codes N18.0, Z49, Z94.0, Z99.2) as a secondary outcome.

Other study variables

We identified other perinatal and maternal characteristics that might be associated with gestational age at birth and CKD using the Swedish birth registry and national census data, which were linked using an anonymous personal identification number. Adjustment variables included birth year (continuous and categorical by decade), sex, birth order (1, 2, ≥3), congenital anomalies (yes/no, identified using ICD-8/9 codes 740-759 and ICD-10 codes Q00-Q99), and several maternal characteristics: age (continuous), education level (<10, 10-12, >12 years), body mass index (BMI; continuous), smoking (0, 1-9, ≥10 cigarettes/day), pre-eclampsia (ICD-8: 637; ICD-9: 624.4-624.7; ICD-10: O14-O15), other hypertensive disorders during pregnancy (ICD-8: 400-404; ICD-9: 401-405, 642.0-642.3, 642.9; ICD-10: I10-I15, O10-O11, O13, O15-O16), and diabetes mellitus during pregnancy (ICD-8: 250; ICD-9: 250, 648.0; ICD-10: O24, E10-E14). Maternal smoking, pre-eclampsia, other hypertensive disorders, and diabetes mellitus were examined because they have been associated with preterm delivery19 and are known risk factors for CKD,20 21 22 although it is unclear whether they are also associated with CKD in the offspring.

Maternal BMI and smoking were assessed at the beginning of prenatal care starting in 1982, and were available for 61.0% and 74.2% of women, respectively. Data were more than 99% complete for all other variables. We imputed missing data for each covariate using a standard multiple imputation procedure based on the variable’s relation with all other covariates and CKD.23

Statistical analysis

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to compute hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between gestational age at birth and risk of CKD. These associations were examined across the entire age range of 0-43 years and in narrower age ranges (0-9, 10-19, 20-43 years) among those still living in Sweden and without a previous diagnosis of CKD at the beginning of the respective age range. Attained age was used as the Cox model time axis. We censored participants at death as identified in the Swedish death registry (n=43 616; 1.0%), or at emigration as determined by absence of a Swedish residential address in census data (n=259 900; 6.2%). Emigrants and non-emigrants had similar gestational ages at birth (median 40 1/7 weeks for both groups), and thus it was unlikely that emigration introduced any substantial bias. Analyses were conducted both unadjusted and adjusted for covariates. We examined potential additive or multiplicative interactions between gestational age at birth and either sex or fetal growth in relation to CKD risk.24 25 The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by examining log-log plots26 and was met in each model.

To assess for potential confounding effects of unmeasured shared familial (genetic or environmental) factors, we performed co-sibling analyses. These analyses used stratified Cox regression with a separate stratum for each family as identified by the mother’s anonymous identification number. A total of 3 504 900 participants (83.7% of the cohort) had at least one sibling and were included in these analyses. In the stratified Cox model, each set of siblings has its own baseline hazard function that reflects the family’s shared genetic and environmental factors, and thus comparisons of different gestational ages at birth are made within the family. In addition, these analyses were further adjusted for the same covariates as in the main analyses.

In secondary analyses, we further adjusted for fetal growth (defined as birth weight standardized for gestational age and sex based on Swedish reference intrauterine growth curves27) to explore the effects of gestational age at birth on risk of CKD independent of fetal growth. In addition, we examined other perinatal and maternal characteristics to identify more early life risk factors for CKD.

Because diagnostic codes for CKD were unavailable before 1987, we performed sensitivity analyses to examine preterm birth in relation to risk of CKD in childhood or adolescence after restricting to those born in 1987-2014 (n=2 851 119). Statistical tests were two sided and used an α level of 0.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 15.1.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. The results will be disseminated to patients and the public through a website and press releases suitable for a non-specialized audience.

Results

Table 1 shows perinatal and maternal characteristics by gestational age at birth. Preterm infants were more likely than full term infants to be male or first born or to have congenital anomalies, and their mothers were more likely to be at the extremes of age, smoke, have low education level or high BMI, or have pre-eclampsia, other hypertensive disorders, or diabetes mellitus during their pregnancy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants by gestational age at birth, Sweden, 1973-2014

| Characteristics | Extremely preterm (22-27 weeks) | Very preterm (28-33 weeks) | Late preterm (34-36 weeks) | Early term (37-38 weeks) | Full term (39-41 weeks) | Post-term (≥42 weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of participants | 8129 | 43 516 | 155 626 | 737 412 | 2 895 746 | 346 186 |

| Child characteristics | ||||||

| Sex: | ||||||

| Male | 4435 (54.6) | 24 286 (55.8) | 84 696 (54.4) | 379 645 (51.5) | 1 471 045 (50.8) | 188 354 (54.4) |

| Female | 3694 (45.4) | 19 230 (44.2) | 70 930 (45.6) | 357 767 (48.5) | 1 424 701 (49.2) | 157 832 (45.6) |

| Birth order: | ||||||

| 1 | 4094 (50.4) | 22 513 (51.7) | 77 533 (49.8) | 296 887 (40.3) | 1 218 861 (42.1) | 172 698 (49.9) |

| 2 | 2292 (28.2) | 12 211 (28.1) | 46 346 (29.8) | 269 837 (36.6) | 1 087 327 (37.5) | 111 056 (32.1) |

| ≥3 | 1743 (21.4) | 8792 (20.2) | 31 747 (20.4) | 170 688 (23.1) | 589 558 (20.4) | 62 432 (18.0) |

| Congenital anomalies | 219 (2.7) | 1115 (2.6) | 1775 (1.1) | 2733 (0.4) | 5024 (0.2) | 944 (0.3) |

| Maternal characteristics | ||||||

| Age (years): | ||||||

| <20 | 356 (4.4) | 2056 (4.7) | 6464 (4.2) | 22 060 (3.0) | 84 018 (2.9) | 12 962 (3.7) |

| 20-24 | 1554 (19.1) | 8868 (20.4) | 33 037 (21.2) | 138 918 (18.8) | 580 804 (20.1) | 76 288 (22.0) |

| 25-29 | 2378 (29.3) | 13 488 (31.0) | 50 748 (32.6) | 242 523 (32.9) | 1 018 704 (35.2) | 121 282 (35.0) |

| 30-34 | 2206 (27.1) | 11 552 (26.6) | 40 970 (26.3) | 210 743 (28.6) | 821 392 (28.4) | 92 811 (26.8) |

| 35-39 | 1280 (15.7) | 6012 (13.8) | 19 826 (12.7) | 100 289 (13.6) | 330 684 (11.4) | 36 880 (10.7) |

| ≥40 | 355 (4.4) | 1540 (3.5) | 4581 (2.9) | 22 879 (3.1) | 60 144 (2.1) | 5963 (1.7) |

| Education (years): | ||||||

| <10 | 1369 (16.8) | 7229 (16.6) | 24 216 (15.6) | 103 813 (14.1) | 367 744 (12.7) | 48 593 (14.0) |

| 10-12 | 3867 (47.6) | 20 812 (47.8) | 73 689 (47.3) | 337 757 (45.8) | 1 304 617 (45.1) | 157 016 (45.4) |

| >12 | 2893 (35.6) | 15 475 (35.6) | 57 721 (37.1) | 295 842 (40.1) | 1 223 385 (42.2) | 140 577 (40.6) |

| Body mass index: | ||||||

| <18.5 | 137 (1.7) | 1118 (2.6) | 4767 (3.1) | 21 727 (2.9) | 65 593 (2.3) | 4649 (1.3) |

| 18.5-24.9 | 6006 (73.9) | 33 733 (77.5) | 120 397 (77.4) | 565 433 (76.7) | 2 279 136 (78.7) | 275 210 (79.5) |

| 25.0-29.9 | 1381 (17.0) | 5935 (13.6) | 21 157 (13.6) | 107 005 (14.5) | 404 104 (14.0) | 46 599 (13.5) |

| ≥30.0 | 605 (7.4) | 2730 (6.3) | 9305 (6.0) | 43 247 (5.9) | 146 913 (5.1) | 19 728 (5.7) |

| Smoking (cigarettes/day): | ||||||

| 0 | 5904 (72.6) | 30 588 (70.3) | 113 066 (72.6) | 562 247 (76.3) | 2 215 716 (76.5) | 247 294 (71.4) |

| 1-9 | 1731 (21.3) | 10 181 (23.4) | 33 600 (21.6) | 138 227 (18.7) | 567 319 (19.6) | 87 933 (25.4) |

| ≥10 | 494 (6.1) | 2747 (6.3) | 8960 (5.8) | 36 938 (5.0) | 112 711 (3.9) | 10 959 (3.2) |

| Pre-eclampsia | 1027 (12.6) | 7775 (17.8) | 15 822 (10.2) | 39 087 (5.3) | 94 678 (3.3) | 11 831 (3.4) |

| Other hypertensive disorders | 111 (1.4) | 767 (1.8) | 2191 (1.4) | 8806 (1.2) | 24 736 (0.9) | 2347 (0.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 88 (1.1) | 902 (2.1) | 3867 (2.5) | 11 940 (1.6) | 16 748 (0.6) | 710 (0.2) |

Gestational age at birth and risk of CKD

Overall, 4305 (0.1%) participants had a diagnosis of CKD during 87.0 million person years of follow-up, yielding an overall incidence rate of 4.95 per 100 000 person years across all ages examined (0-43 years). The incidence rates by gestational age at birth were 9.24 for preterm infants, 5.90 for early term, and 4.47 for full term (table 2). Neonatal acute renal failure (ICD-9 584 or ICD-10 N17, available during 1987-2015) was identified in 300 participants (including 83 born preterm), of whom 72 (24.0%) had a subsequent diagnosis of CKD (including 15 born preterm).

Table 2.

Associations between gestational age at birth and risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD), Sweden, 1973-2015

| Attained age by gestational age | All | Males | Females | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | No with CKD | Incidence* | Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted† hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | No with CKD | Incidence* | Adjusted† hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | No with CKD | Incidence* | Adjusted† hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | |||

| 0-43 years: | ||||||||||||||||

| Preterm | 207 271 | 379 | 9.24 | 2.12 (1.90 to 2.36) | 1.94 (1.74 to 2.16) | <0.001 | 210 | 9.32 | 1.76 (1.52 to 2.04) | <0.001 | 169 | 9.14 | 2.21 (1.88 to 2.60) | <0.001 | ||

| Extremely preterm | 8129 | 11 | 13.33 | 3.77 (2.08 to 6.81) | 3.01 (1.67 to 5.45) | <0.001 | 5 | 11.64 | 2.39 (0.99 to 5.76) | 0.05 | 6 | 15.17 | 3.85 (1.73 to 8.60) | 0.001 | ||

| Very preterm | 43 516 | 87 | 10.74 | 2.51 (2.02 to 3.10) | 2.22 (1.79 to 2.75) | <0.001 | 44 | 9.78 | 1.84 (1.36 to 2.48) | <0.001 | 43 | 11.94 | 2.83 (2.09 to 3.85) | <0.001 | ||

| Late preterm | 155 626 | 281 | 8.76 | 1.99 (1.76 to 2.25) | 1.84 (1.62 to 2.08) | <0.001 | 161 | 9.15 | 1.73 (1.47 to 2.04) | <0.001 | 120 | 8.28 | 2.01 (1.66 to 2.43) | <0.001 | ||

| Early term | 737 412 | 870 | 5.90 | 1.39 (1.29 to 1.50) | 1.30 (1.20 to 1.40) | <0.001 | 531 | 6.90 | 1.35 (1.22 to 1.49) | <0.001 | 339 | 4.81 | 1.23 (1.09 to 1.39) | 0.001 | ||

| Full term | 2 895 746 | 2690 | 4.47 | Reference | Reference | 1545 | 5.05 | Reference | 1145 | 3.87 | Reference | |||||

| Post-term | 346 186 | 366 | 4.57 | 0.90 (0.81 to 1.01) | 0.98 (0.88 to 1.09) | 0.68 | 245 | 5.79 | 1.10 (0.96 to 1.26) | 0.15 | 121 | 3.20 | 0.79 (0.66 to 0.96) | 1.02 | ||

| Each additional week | 0.90 (0.88 to 0.91) | 0.92 (0.90 to 0.93) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.95) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.88 to 0.92) | <0.001 | |||||||||

| 0-9 years: | ||||||||||||||||

| Preterm | 207 271 | 123 | 7.05 | 5.64 (4.58 to 6.95) | 5.09 (4.11 to 6.31) | <0.001 | 80 | 8.39 | 5.34 (4.08 to 6.98) | <0.001 | 43 | 5.43 | 4.72 (3.30 to 6.75) | <0.001 | ||

| Extremely preterm | 8129 | 4 | 9.50 | 7.47 (2.79 to 20.02) | 5.15 (1.92 to 13.84) | 0.001 | 1 | 4.50 | 2.15 (0.30 to 15.35) | 0.45 | 3 | 15.09 | 9.47 (2.98 to 30.10) | <0.001 | ||

| Very preterm | 43 516 | 30 | 8.56 | 6.84 (4.71 to 9.95) | 5.96 (4.07 to 8.73) | <0.001 | 20 | 10.29 | 6.28 (3.93 to 10.04) | <0.001 | 10 | 6.41 | 5.46 (2.82 to 10.56) | <0.001 | ||

| Late preterm | 155 626 | 89 | 6.58 | 5.27 (4.17 to 6.67) | 4.87 (3.83 to 6.18) | <0.001 | 59 | 8.01 | 5.21 (3.87 to 7.01) | <0.001 | 30 | 4.88 | 4.33 (2.89 to 6.50) | <0.001 | ||

| Early term | 737 412 | 152 | 2.37 | 1.89 (1.56 to 2.30) | 1.78 (1.47 to 2.16) | <0.001 | 100 | 3.02 | 1.96 (1.53 to 2.50) | <0.001 | 52 | 1.67 | 1.51 (1.10 to 2.09) | 0.01 | ||

| Full term | 2 895 746 | 317 | 1.25 | Reference | Reference | 190 | 1.48 | Reference | 127 | 1.02 | Reference | |||||

| Post-term | 346 186 | 41 | 1.33 | 1.06 (0.77 to 1.47) | 1.15 (0.83 to 1.59) | 0.40 | 27 | 1.62 | 1.17 (0.78 to 1.76) | 0.44 | 14 | 0.98 | 1.12 (0.65 to 1.96) | 0.68 | ||

| Each additional week | 0.81 (0.79 to 0.83) | 0.83 (0.81 to 0.85) | <0.001 | 0.82 (0.80 to 0.85) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.79 to 0.87) | <0.001 | |||||||||

| 10-19 years: | ||||||||||||||||

| Preterm | 148 498 | 86 | 6.81 | 2.16 (1.72 to 2.71) | 1.97 (1.57 to 2.49) | <0.001 | 44 | 6.36 | 1.73 (1.26 to 2.38) | 0.001 | 42 | 7.35 | 2.33 (1.67 to 3.25) | <0.001 | ||

| Extremely preterm | 3231 | 6 | 24.13 | 7.93 (3.55 to 17.73) | 5.75 (2.57 to 12.88) | <0.001 | 4 | 30.95 | 6.84 (2.54 to 18.38) | <0.001 | 2 | 16.75 | 4.44 (1.10 to 17.91) | 0.04 | ||

| Very preterm | 29 615 | 19 | 7.61 | 2.42 (1.53 to 3.83) | 2.10 (1.33 to 3.34) | 0.002 | 6 | 4.34 | 1.13 (0.50 to 2.55) | 0.77 | 13 | 11.64 | 3.52 (2.00 to 6.21) | <0.001 | ||

| Late preterm | 115 652 | 61 | 6.17 | 1.96 (1.50 to 2.55) | 1.82 (1.40 to 2.38) | <0.001 | 34 | 6.28 | 1.74 (1.22 to 2.48) | 0.002 | 27 | 6.03 | 1.95 (1.31 to 2.91) | 0.001 | ||

| Early term | 539 745 | 227 | 5.00 | 1.59 (1.37 to 1.86) | 1.49 (1.28 to 1.74) | <0.001 | 130 | 5.50 | 1.53 (1.25 to 1.88) | <0.001 | 97 | 4.45 | 1.44 (1.14 to 1.82) | 0.002 | ||

| Full term | 2 152 569 | 579 | 3.15 | Reference | Reference | 321 | 3.44 | Reference | 258 | 2.85 | Reference | |||||

| Post-term | 271 479 | 64 | 2.70 | 0.85 (0.66 to 1.10) | 0.97 (0.75 to 1.26) | 0.81 | 37 | 2.95 | 0.94 (0.67 to 1.32) | 0.71 | 27 | 2.42 | 1.02 (0.68 to 1.52) | 0.93 | ||

| Each additional week | 0.88 (0.86 to 0.91) | 0.90 (0.88 to 0.93) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.94) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.86 to 0.93) | <0.001 | |||||||||

| 20-43 years: | ||||||||||||||||

| Preterm | 105 246 | 170 | 15.53 | 1.45 (1.24 to 1.70) | 1.34 (1.15 to 1.57) | <0.001 | 86 | 14.14 | 1.10 (0.88 to 1.38) | 0.38 | 84 | 17.27 | 1.73 (1.38 to 2.17) | <0.001 | ||

| Extremely preterm | 1816 | 1 | 6.44 | 0.64 (0.09 to 4.55) | 0.58 (0.08 to 4.11) | 0.58 | 0 | 0.00 | NE | NE | 1 | 12.94 | 1.31 (0.18 to 9.30) | 0.79 | ||

| Very preterm | 20 567 | 38 | 18.10 | 1.70 (1.23 to 2.34) | 1.54 (1.12 to 2.13) | 0.008 | 18 | 15.31 | 1.18 (0.74 to 1.89) | 0.48 | 20 | 21.65 | 2.14 (1.37 to 3.33) | 0.001 | ||

| Late preterm | 82 863 | 131 | 15.07 | 1.40 (1.18 to 1.68) | 1.31 (1.09 to 1.56) | 0.003 | 68 | 14.08 | 1.10 (0.86 to 1.41) | 0.45 | 63 | 16.31 | 1.64 (1.27 to 2.13) | <0.001 | ||

| Early term | 374 596 | 491 | 12.99 | 1.23 (1.11 to 1.36) | 1.15 (1.04 to 1.27) | 0.006 | 301 | 14.88 | 1.18 (1.04 to 1.34) | 0.01 | 190 | 10.81 | 1.11 (0.95 to 1.30) | 0.20 | ||

| Full term | 1 532 760 | 1794 | 10.93 | Reference | Reference | 1034 | 12.35 | Reference | 760 | 9.46 | Reference | |||||

| Post-term | 203 987 | 261 | 10.26 | 0.89 (0.78 to 1.01) | 0.94 (0.83 to 1.08) | 0.39 | 181 | 13.89 | 1.12 (0.96 to 1.32) | 0.15 | 80 | 6.45 | 0.69 (0.55 to 0.87) | 0.002 | ||

| Each additional week | 0.94 (0.92 to 0.96) | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.98) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.01) | 0.32 | 0.93 (0.90 to 0.95) | <0.001 | |||||||||

Preterm=<37 weeks; extremely preterm=22-27 weeks; very preterm=28-33 weeks; late preterm=34-36 weeks; early term=37-38 weeks; full term=39-41 weeks; post-term=≥42 weeks; NE=not estimable.

Per 100 000 person years.

Adjusted for child characteristics (birth year, sex, birth order, congenital anomalies) and maternal characteristics (age, education, body mass index, smoking, pre-eclampsia, other hypertensive disorders, diabetes mellitus).

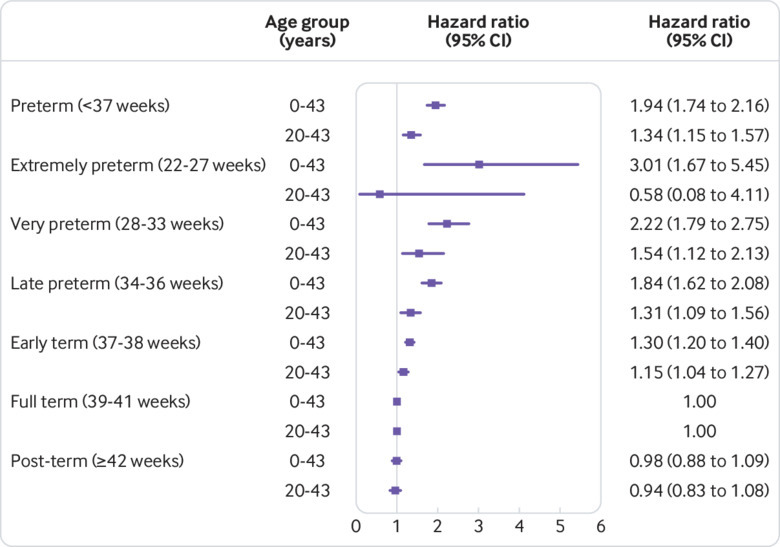

Across the entire age range (0-43 years), gestational age at birth was inversely associated with risk of CKD (adjusted hazard ratio for each additional week of gestation, 0.92, 95% confidence interval 0.90 to 0.93; P<0.001; table 2). Preterm and early term birth were associated with nearly twofold and 1.3-fold higher risks of CKD, respectively, compared with full term birth (adjusted hazard ratio 1.94, 95% confidence interval 1.74 to 2.16; P<0.001; and 1.30, 1.20 to 1.40; P<0.001). Participants born extremely preterm had a threefold higher risk of CKD (3.01, 1.67 to 5.45; P<0.001). Increased risks were observed among both males and females born preterm (eg, males: 1.76, 1.52 to 2.04; P<0.001; females: 2.21, 1.88 to 2.60; P<0.001).

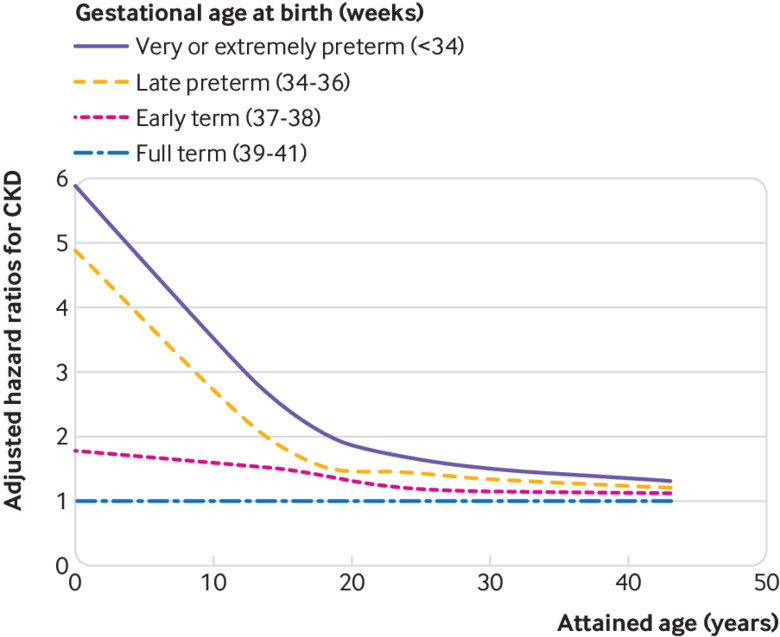

In analyses of narrower age intervals, preterm birth was strongly associated with increased risk of CKD in early childhood (ages 0-9 years: 5.09, 4.11 to 6.31; P<0.001). This association weakened but remained significantly increased in later childhood and adolescence (ages 10-19 years: 1.97, 1.57 to 2.49; P<0.001) and adulthood (ages 20-43 years: 1.34, 1.15 to 1.57; P<0.001). A similar pattern was observed among males and females, except that the association between preterm birth and risk of CKD in adulthood was statistically significant among women only (table 2). Figure 1 shows the adjusted hazard ratios (fitted by cubic spline) for risk of CKD by attained age for different gestational age groups. Figure 2 shows a forest plot of key findings at ages 0-43 years and 20-43 years.

Fig 1.

Adjusted hazard ratios for chronic kidney disease (CKD) by gestational age at birth compared with full term birth, Sweden, 1973-2015

Fig 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios for chronic kidney disease at ages 0-43 and 20-43 years by gestational age at birth compared with full term birth, Sweden, 1973-2015. Whiskers are 95% confidence intervals

Interactions

Supplemental table 1 shows the interactions between gestational age at birth and sex and risk of CKD. Across all ages examined (0-43 years), the background incidence of CKD among participants born full term was higher for males than for females (5.05 v 3.87 per 100 000 person years). Males and females born preterm, however, had similarly increased incidence rates for CKD (9.32 v 9.14 per 100 000 person years) that were not significantly different from each other (adjusted hazard ratio 1.01, 95% confidence interval 0.81 to 1.22; P=0.91). A negative multiplicative interaction was found between preterm birth and male sex (ie, their combined effect on risk of CKD was less than the product of their separate effects; P=0.01; see supplemental table 1). No additive interaction (P=0.26) was found, suggesting that preterm birth accounted for a similar number of CKD cases among males and females.

Supplemental table 2 shows the interactions between gestational age at birth and fetal growth. The risk of CKD was highest among participants born preterm and small for gestational age (3.08, 2.39 to 3.96; P<0.001; compared with those born full term and appropriate for gestational age). No interaction was found between preterm birth and fetal growth on the multiplicative scale. A borderline significant positive additive interaction (P=0.045) was found, however, suggesting that preterm birth might account for more CKD cases among those who were also small for gestational age.

Co-sibling analyses

Co-sibling analyses to control for unmeasured shared familial factors did not result in weaker risk estimates; on the contrary, they were strengthened by nearly 10% on average (table 3). These findings suggest that the associations observed in the main analyses were not due to shared genetic or environmental factors in families. For example, in analyses of the entire age range (0-43 years), the adjusted hazard ratio for CKD associated with preterm birth was 1.94 (95% confidence interval 1.74 to 2.16) in the main analysis and 2.37 (1.85 to 3.03) in the co-sibling analysis. At ages 20-43 years, the association between preterm birth and risk of CKD was no longer significant (1.38, 0.97 to 1.97; P=0.08), reflecting lower statistical power than the main analyses; however, this point estimate was slightly higher than the corresponding estimate in the main analyses (hazard ratio 1.34). Gestational age at birth remained significantly inversely associated with risk of CKD (adjusted hazard ratio for each additional week of gestation, 0.96, 95% confidence interval 0.91 to 0.99; P=0.04; table 3).

Table 3.

Co-sibling analyses of gestational age at birth in relation to risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD), Sweden, 1973-2015

| Attained age by gestational age | All | Males | Females | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of participants | No with CKD | Adjusted* hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | No of participants | No with CKD | Adjusted* hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | No of participants | No with CKD | Adjusted* hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | |||

| 0-43 years: | ||||||||||||||

| Preterm | 162 377 | 302 | 2.37 (1.85 to 3.03) | <0.001 | 89 071 | 169 | 2.85 (1.84 to 4.41) | <0.001 | 73 306 | 133 | 1.83 (1.12 to 2.98) | 0.02 | ||

| Early term | 618 764 | 702 | 1.33 (1.15 to 1.55) | <0.001 | 381 424 | 427 | 1.70 (1.31 to 2.21) | <0.001 | 300 340 | 275 | 1.14 (0.82 to 1.59) | 0.42 | ||

| Full term | 2 440 243 | 2193 | Reference | 1 240 750 | 1,245 | Reference | 1 199 493 | 948 | Reference | |||||

| Each additional week | 0.89 (0.86 to 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.81 to 0.91) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.98) | 0.01 | ||||||||

| 0-9 years: | ||||||||||||||

| Preterm | 162 377 | 105 | 7.29 (4.26 to 12.47) | <0.001 | 89 071 | 69 | 9.95 (3.93 to 25.14) | <0.001 | 73 306 | 36 | 10.35 (2.21 to 48.56) | <0.001 | ||

| Early term | 618 764 | 128 | 1.96 (1.35 to 2.83) | <0.001 | 318 424 | 82 | 2.86 (1.46 to 5.60) | 0.002 | 300 340 | 46 | 1.19 (0.47 to 2.97) | 0.72 | ||

| Full term | 2 440 243 | 281 | Reference | 1 240 750 | 169 | Reference | 1 199 493 | 112 | Reference | |||||

| Each additional week | 0.74 (0.69 to 0.81) | <0.001 | 0.74 (0.65 to 0.84) | <0.001 | 0.62 (0.47 to 0.81) | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 10-19 years: | ||||||||||||||

| Preterm | 121 994 | 66 | 2.28 (1.38 to 3.77) | 0.001 | 66 845 | 34 | 2.59 (1.00 to 6.67) | 0.05 | 55 149 | 32 | 1.82 (0.69 to 4.82) | 0.23 | ||

| Early term | 465 354 | 195 | 1.65 (1.25 to 2.17) | <0.001 | 240 663 | 110 | 2.02 (1.20 to 3.39) | 0.008 | 224 691 | 85 | 1.23 (0.67 to 2.26) | 0.50 | ||

| Full term | 1 863 062 | 511 | Reference | 947 167 | 276 | Reference | 915 895 | 235 | Reference | |||||

| Each additional week | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.94) | <0.001 | 0.82 (0.72 to 0.93) | 0.002 | 0.89 (0.78 to 1.02) | 0.08 | ||||||||

| 20-43 years: | ||||||||||||||

| Preterm | 84 936 | 131 | 1.38 (0.97 to 1.97) | 0.08 | 46 804 | 66 | 1.52 (0.81 to 2.86) | 0.20 | 38 132 | 65 | 1.03 (0.50 to 2.16) | 0.93 | ||

| Early term | 316 751 | 379 | 1.07 (0.87 to 1.32) | 0.51 | 165 680 | 235 | 1.33 (0.93 to 1.89) | 0.12 | 151 071 | 144 | 0.98 (0.62 to 1.56) | 0.94 | ||

| Full term | 1 299 153 | 1401 | Reference | 660 998 | 800 | Reference | 638 155 | 601 | Reference | |||||

| Each additional week | 0.96 (0.91 to 0.99) | 0.04 | 0.93 (0.86 to 1.01) | 0.08 | 1.00 (0.91 to 1.10) | 0.97 | ||||||||

Preterm=<37 weeks; early term=37-38 weeks; full term=39-41 weeks.

Adjusted for shared familial (genetic or environmental) factors, and additionally for specific child characteristics (birth year, sex, birth order, congenital anomalies) and maternal characteristics (age, education, body mass index, smoking, preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders, diabetes mellitus).

Secondary analyses

Analyses of end stage renal disease as a secondary outcome yielded similar results as for CKD overall. Among 4305 participants with a diagnosis of CKD, 1472 (34.2%) had end stage renal disease. At ages 0-43 years, adjusted hazard ratios for end stage renal disease associated with preterm or early term birth were 2.09 (95% confidence interval 1.76 to 2.48; P<0.001) and 1.44 (1.27 to 1.62; P<0.001), respectively.

In all analyses, further adjustment for fetal growth had a negligible effect on any of the risk estimates. A strong inverse association remained between gestational age at birth and risk of CKD (for example, adjusted hazard ratio for each additional week of gestation, ages 0-43 years: 0.91, 0.90 to 0.92; P<0.001; ages 20-43 years: 0.95, 0.93 to 0.97; P<0.001), and increased risks for preterm compared with full term births (eg, adjusted hazard ratios, ages 0-43 years: 1.93, 1.74 to 2.16; P<0.001; ages 20-43 years: 1.35, 1.15 to 1.58; P<0.001).

Analyses of other perinatal and maternal characteristics identified several other risk factors for CKD in addition to preterm birth (table 4). After adjustment for all other factors, male sex was associated with a 1.3-fold increased risk of CKD compared with female sex. Congenital anomalies were associated with nearly a 20-fold higher risk, and maternal obesity (BMI ≥30) and pre-eclampsia were each associated with more than 1.2-fold higher risks. Maternal age, education, smoking, other (non-pre-eclamptic) hypertensive disorders, and diabetes mellitus during pregnancy were not associated with risk of CKD in the offspring. Statistical power was limited for assessing maternal history of other hypertensive disorders or diabetes owing to a small number of cases identified (table 4).

Table 4.

Associations between perinatal or maternal characteristics and risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) from birth to age 43 years, Sweden, 1973-2015.

| Characteristics | CKD | Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted† hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Incidence* | ||||||

| Child characteristics | |||||||

| Gestational age at birth: | |||||||

| Preterm | 379 | 9.24 | 2.12 (1.90 to 2.36) | <0.001 | 1.94 (1.74 to 2.16) | <0.001 | |

| Extremely preterm | 11 | 13.33 | 3.77 (2.08 to 6.81) | <0.001 | 3.01 (1.67 to 5.45) | <0.001 | |

| Very preterm | 87 | 10.74 | 2.51 (2.02 to 3.10) | <0.001 | 2.22 (1.79 to 2.75) | <0.001 | |

| Late preterm | 281 | 8.76 | 1.99 (1.76 to 2.25) | <0.001 | 1.84 (1.62 to 2.08) | <0.001 | |

| Early term | 870 | 5.90 | 1.39 (1.29 to 1.50) | <0.001 | 1.30 (1.20 to 1.40) | <0.001 | |

| Term | 2690 | 4.47 | Reference | Reference | |||

| Post-term | 366 | 4.57 | 0.90 (0.81 to 1.01) | 0.07 | 0.98 (0.88 to 1.09) | 0.68 | |

| Sex: | |||||||

| Male | 2531 | 5.65 | 1.34 (1.26 to 1.42) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.25 to 1.41) | <0.001 | |

| Female | 1774 | 4.20 | Reference | Reference | |||

| Birth order: | |||||||

| 1 | 1759 | 4.79 | Reference | Reference | |||

| 2 | 1629 | 5.09 | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.13) | 0.13 | 1.08 (1.00 to 1.15) | 0.05 | |

| ≥3 | 917 | 5.03 | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.16) | 0.09 | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.14) | 0.40 | |

| Congenital anomalies: | |||||||

| Yes | 116 | 97.89 | 18.55 (15.42 to 22.31) | <0.001 | 19.02 (15.80 to 22.90) | <0.001 | |

| No | 4189 | 4.82 | Reference | Reference | |||

| Maternal characteristics | |||||||

| Age (years): | |||||||

| <20 | 197 | 5.85 | 1.00 (0.86 to 1.16) | 0.98 | 1.13 (0.97 to 1.32) | 0.12 | |

| 20-24 | 1041 | 5.10 | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.04) | 0.29 | 1.02 (0.94 to 1.11) | 0.64 | |

| 25-29 | 1539 | 4.86 | Reference | Reference | |||

| 30-34 | 1059 | 4.84 | 1.12 (1.04 to 1.22) | 0.003 | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.10) | 0.74 | |

| 35-39 | 396 | 4.83 | 1.22 (1.09 to 1.36) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.89 to 1.12) | 0.92 | |

| ≥40 | 73 | 4.91 | 1.28 (1.01 to 1.62) | 0.04 | 0.95 (0.75 to 1.20) | 0.65 | |

| Education (years): | |||||||

| <10 | 735 | 5.69 | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.06) | 0.60 | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.15) | 0.28 | |

| 10-12 | 2114 | 5.03 | Reference | Reference | |||

| >12 | 1456 | 4.54 | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.07) | 0.88 | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.05) | 0.50 | |

| Body mass index: | |||||||

| <18.5 | 83 | 4.33 | 1.19 (0.96 to 1.48) | 0.12 | 0.93 (0.74 to 1.15) | 0.49 | |

| 18.5-24.9 | 3716 | 4.96 | Reference | Reference | |||

| 25.0-29.9 | 372 | 4.88 | 1.88 (1.69 to 2.10) | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.03 to 1.30) | 0.01 | |

| ≥30.0 | 134 | 5.32 | 2.32 (1.95 to 2.77) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.06 to 1.51) | 0.01 | |

| Smoking (cigarettes/day): | |||||||

| 0 | 2687 | 4.89 | Reference | Reference | |||

| 1-9 | 1433 | 5.07 | 0.91 (0.81 to 1.02) | 0.12 | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.14) | 0.84 | |

| ≥10 | 185 | 4.96 | 0.85 (0.73 to 0.99) | 0.03 | 0.95 (0.82 to 1.11) | 0.54 | |

| Pre-eclampsia: | |||||||

| Yes | 308 | 7.13 | 1.21 (1.08 to 1.36) | 0.001 | 1.29 (1.15 to 1.45) | <0.001 | |

| No | 3997 | 4.83 | Reference | Reference | |||

| Other hypertensive disorders: | |||||||

| Yes | 30 | 5.16 | 1.65 (1.15 to 2.36) | 0.007 | 1.09 (0.76 to 1.56) | 0.64 | |

| No | 4275 | 4.95 | Reference | Reference | |||

| Diabetes mellitus: | |||||||

| Yes | 30 | 6.49 | 1.62 (1.13 to 2.33) | 0.008 | 1.12 (0.78 to 1.61) | 0.53 | |

| No | 4275 | 4.94 | Reference | Reference | |||

Preterm=<37 weeks; extremely preterm=22-27 weeks; very preterm=28-33 weeks; late preterm=34-36 weeks; early term=37-38 weeks; full term=39-41 weeks; post-term=≥42 weeks.

Incidence rate per 100 000 person years.

Adjusted for birth year and all other variables included in table.

Sensitivity analyses were performed after restricting to participants born in 1987-2014 (ie, excluding earlier birth years when diagnostic codes for CKD were unavailable). These participants had follow-up in childhood or adolescence, but follow-up was insufficient to examine risks in adulthood. All risk estimates were negligibly affected, and the conclusions were unchanged. For example, adjusted hazard ratios for CKD associated with preterm birth were 5.19 (95% confidence interval 4.15 to 6.50; P<0.001) at ages 0-9 years and 1.97 (1.52 to 2.56; P<0.001) at ages 10-19 years.

Discussion

In this large national cohort study, we found a strong inverse association between gestational age at birth and risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) from childhood into mid-adulthood. After adjustment for other perinatal and maternal factors, those born preterm or extremely preterm had nearly twofold and threefold higher risks, respectively. Furthermore, we found a significantly increased risk of CKD even among those born at early term (37-38 weeks). These associations were strongest in childhood then weakened but remained substantially increased in adolescence and adulthood. Males and females were similarly affected. Importantly, these findings did not seem to be due to shared genetic or environmental factors in families but rather to direct effects of preterm birth.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A key strength of this study was the ability to examine preterm birth in relation to CKD in a large population based cohort with follow-up into the fifth decade of life, using highly complete birth and medical registry data. This study design minimizes potential selection or ascertainment biases and provides more robust risk estimates. The results were controlled for potential perinatal and maternal confounders, as well as unmeasured shared familial factors in co-sibling analyses. Sweden’s relatively more homogeneous population (for example, compared with the US) could also improve internal comparability and reduce the potential for confounding.

Limitations include the lack of more detailed clinical data to validate CKD diagnoses. Administrative data have been reported to under-ascertain CKD.28 A Swedish study of 1.1 million outpatients reported a CKD prevalence of 0.29% in adults aged 18-44 years based on serum creatinine measurements,29 which was nearly twice that among similarly aged adults in the present study based on ICD codes (0.15%). However, misclassification of CKD, especially beyond childhood, might be expected to be non-differential by gestational age at birth and therefore to influence our results conservatively (ie, toward the null hypothesis). We also lacked diagnoses before 1987 when no specific diagnostic codes for CKD existed; however, sensitivity analyses restricted to those born in 1987 or later yielded nearly identical results. Specific information on CKD severity and its underlying causes was not available and would be invaluable to assess in future studies with access to such data. In addition, gestational age at birth was based on maternal report of last menstrual period during the 1970s, which is less accurate than ultrasound estimation used in subsequent years. Finally, despite having up to 43 years of follow-up, this was still a relatively young Swedish cohort. Additional follow-up to older ages will be needed when such data become available, as well as studies in other diverse populations.

Comparison with other studies

Some but not all previous studies have linked low birth weight (<2500 g) with higher risk of CKD in childhood or adulthood; a meta-analysis of 18 such studies reported a pooled odds ratio of 1.7 (95% confidence interval 1.4 to 2.1).9 The largest of these was a Norwegian cohort study of 2.2 million births, which reported that being small for gestational age was associated with an increased risk of end stage renal disease at ages up to 38 years (hazard ratio 1.5, 95% confidence interval 1.2 to 1.9).30 In an overlapping Norwegian cohort of 1.8 million births, low birth weight was associated with an increased risk of end stage renal disease at ages up to 42 years (adjusted hazard ratios 1.6 to 1.8), which did not seem to be related to shared familial factors; preterm birth was associated with a non-significantly increased risk of end stage renal disease (adjusted hazard ratio 1.3) but was not examined in narrower gestational age groups.15 A nationwide Japanese study also suggested that low birth weight or preterm birth was associated with increased risk of CKD up to age 15 years (relative risks >4).31 Our findings from a large nationwide cohort show that those born preterm have substantially increased risks of CKD that extend into mid-adulthood. These risks were much higher early in life (fig 1), which could in part be due to continued advances in neonatal care that have improved survival among smaller, less healthy infants who are more vulnerable to the development of CKD.32

Interestingly, in addition to preterm birth, we found that early term birth (37-38 weeks) also was associated with an increased risk of CKD from childhood into adulthood, compared with full term birth (39-41 weeks) (eg, adjusted hazard ratios, ages 0-43 years: 1.30, 95% confidence interval 1.20 to 1.40; P<0.001; ages 20-43 years: 1.15, 1.04 to 1.27; P=0.006). This is noteworthy because nephrogenesis is normally completed by 36 weeks of gestation.1 4 These findings suggest the presence of other mechanisms beyond nephron endowment by which premature birth might affect long term renal function. Early term birth is common (17.6% of the present cohort) and increasingly has been linked with adverse outcomes compared with later term birth. A US study of 13 258 elective caesarean term deliveries found that more than one third were performed at 37-38 weeks, and such births were associated with significantly higher risks of respiratory complications and other adverse neonatal outcomes.33 Early term birth has also been associated with increased mortality from various causes in young adulthood.34 Studies with additional clinical data on early term birth and its underlying causes are needed to further elucidate the pathways potentially linking it with CKD later in life.

We confirmed several other risk factors for CKD in addition to preterm birth, including male sex, congenital anomalies, and maternal obesity, which are consistent with previous findings.20 35 36 37 38 In contrast with a previous report,30 we found that maternal pre-eclampsia also was associated with an increased risk of CKD in the offspring. Maternal pre-eclampsia has previously been associated with development of hypertension and cardiovascular disease in the offspring.39 The potential effects on renal outcomes in the offspring have seldom been examined but warrant further elucidation in future studies.40

Both preterm birth and low birth weight have been associated with impaired nephrogenesis, resulting in a lower nephron number that is lifelong.3 4 41 Nephron number varies widely in the general population, ranging from 200 000 to 2 000 000 for each kidney.42 Fetal kidneys develop through “branching morphogenesis,” which reaches peak growth during the third trimester.43 44 Preterm birth interrupts this critical growth process, resulting in a lower nephron number as well as a higher percentage of abnormal glomeruli.45 46 In addition, potentially nephrotoxic drugs commonly used in the treatment of preterm infants might impair postnatal nephrogenesis.47 A reduced nephron number has been hypothesized to lead to glomerular hyperfiltration, sodium retention, hypertension, further loss of nephrons, and progressive kidney disease due to secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.41 This vicious cycle of perpetuating renal injury could potentially lead to a lifelong increased risk of CKD among those born preterm.

Implications

Given the high prevalence of preterm birth (currently 10% in the US48 and 5-8% in Europe49) and more than 95% survival into adulthood, the associations we found with CKD have important public health implications. As previously reported, there may already be a silent epidemic of CKD among those who were born preterm.50 CKD is often under-recognized51 but has an estimated prevalence of 5-10% in general adult populations,52 53 which might be substantially higher among those born prematurely. Our findings underscore the importance of public health strategies to prevent preterm birth, including better access to preconception and prenatal care for high risk women, and reduction of non-medically indicated deliveries before full term.54

Children and adults who were born preterm need long term follow-up and early preventive actions to help preserve renal function (box 1). Medical records and history taking for patients of all ages should routinely include birth history to help trigger preventive actions in those born prematurely.55 56 57 Such interventions should include patient counseling on avoidance of potentially nephrotoxic exposures (eg, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), and control of other known risk factors for progression of kidney disease, including obesity, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, anemia, and smoking.58 Hypertension is a strong risk factor for the development of CKD, and effective blood pressure control has been shown to slow disease progression.58 Periodic monitoring of renal function with serum creatinine, cystatin C, or urine albumin has been recommended based on individualized risk assessment, including degree of prematurity, history of acute kidney injury, and structural abnormalities on renal ultrasonography.50 59 Kidney donation by people with a low nephron number might result in accelerated loss of function in the remaining kidney and is therefore strongly cautioned against, or contraindicated if other risk factors for CKD exist.59

Box 1. Clinical recommendations to preserve renal function in people born prematurely.

Include birth history in medical history taking in patients of all ages, including adults, to help trigger preventive actions in those born prematurely

Counsel patients on avoidance of potentially nephrotoxic exposures (eg, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) and other exacerbating factors (dehydration, recurrent urinary tract infections)

Maintain well controlled blood pressure

Reduce other known risk factors for chronic kidney disease, including obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, anemia, and smoking

Periodically monitor renal function with serum creatinine, cystatin C, or urine albumin, based on individualized risk assessment

For potential living kidney donors, advise caution because of higher susceptibility to renal dysfunction in the remaining kidney

Conclusions

This large cohort study provides population based risk estimates for CKD into mid-adulthood associated with gestational age at birth. We found that preterm and early term birth are strong independent risk factors for the development of CKD from childhood into mid-adulthood. People born prematurely need long term follow-up for monitoring and preventive actions to preserve renal function across the life course. Additional studies will be needed to assess these risks in later adulthood when such data become available, and to further elucidate the underlying causes and clinical course of CKD in those born prematurely.

What is already known on this topic

Preterm birth (gestational age <37 weeks) interrupts kidney maturation during a critical growth period, resulting in lower nephron endowment that is lifelong

Preterm birth has been associated with higher risk of renal failure during infancy

Little is known about the long term risks of chronic kidney disease (CKD) into adulthood among people born prematurely

What this study adds

In a large national cohort, preterm and early term (37-38 weeks) birth were strong risk factors for the development of CKD from childhood into mid-adulthood

Those born prematurely need long term follow-up for monitoring and preventive actions to preserve renal function across the life course

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplemental information: additional tables 1 and 2

Contributors: All authors conceived and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. JS and KS acquired the data. CC drafted the manuscript. CC, JS, and KS obtained funding. CC and JS did the statistical analysis. KS and JS serve as guarantors and affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained. All authors had full access to all the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The corresponding author (CC) attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL139536), the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, and ALF project grant, Region Skåne/Lund University, Sweden. The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the ethics committee of Lund University in Sweden (No 2012/795; 2013/736).

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The corresponding author (CC) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported, no important aspects of the study have been omitted, and any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

References

- 1. Faa G, Gerosa C, Fanni D, et al. Morphogenesis and molecular mechanisms involved in human kidney development. J Cell Physiol 2012;227:1257-68. 10.1002/jcp.22985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hinchliffe SA, Sargent PH, Howard CV, Chan YF, van Velzen D. Human intrauterine renal growth expressed in absolute number of glomeruli assessed by the disector method and Cavalieri principle. Lab Invest 1991;64:777-84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abitbol CL, Rodriguez MM. The long-term renal and cardiovascular consequences of prematurity. Nat Rev Nephrol 2012;8:265-74. 10.1038/nrneph.2012.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abitbol CL, DeFreitas MJ, Strauss J. Assessment of kidney function in preterm infants: lifelong implications. Pediatr Nephrol 2016;31:2213-22. 10.1007/s00467-016-3320-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Keller G, Zimmer G, Mall G, Ritz E, Amann K. Nephron number in patients with primary hypertension. N Engl J Med 2003;348:101-8. 10.1056/NEJMoa020549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brenner BM, Mackenzie HS. Nephron mass as a risk factor for progression of renal disease. Kidney Int Suppl 1997;63:S124-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pottel H, Hoste L, Delanaye P. Abnormal glomerular filtration rate in children, adolescents and young adults starts below 75 mL/min/1.73 m(2). Pediatr Nephrol 2015;30:821-8. 10.1007/s00467-014-3002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Delanaye P, Glassock RJ. Lifetime Risk of CKD: What Does It Really Mean? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;10:1504-6. 10.2215/CJN.07860715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. White SL, Perkovic V, Cass A, et al. Is low birth weight an antecedent of CKD in later life? A systematic review of observational studies. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;54:248-61. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jetton JG, Boohaker LJ, Sethi SK, et al. Neonatal Kidney Collaborative (NKC) Incidence and outcomes of neonatal acute kidney injury (AWAKEN): a multicentre, multinational, observational cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2017;1:184-94. 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30069-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Selewski DT, Charlton JR, Jetton JG, et al. Neonatal Acute Kidney Injury. Pediatrics 2015;136:e463-73. 10.1542/peds.2014-3819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mammen C, Al Abbas A, Skippen P, et al. Long-term risk of CKD in children surviving episodes of acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit: a prospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2012;59:523-30. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bruel A, Rozé JC, Quere MP, et al. Renal outcome in children born preterm with neonatal acute renal failure: IRENEO-a prospective controlled study. Pediatr Nephrol 2016;31:2365-73. 10.1007/s00467-016-3444-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chaturvedi S, Ng KH, Mammen C. The path to chronic kidney disease following acute kidney injury: a neonatal perspective. Pediatr Nephrol 2017;32:227-41. 10.1007/s00467-015-3298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ruggajo P, Skrunes R, Svarstad E, Skjærven R, Reisæther AV, Vikse BE. Familial Factors, Low Birth Weight, and Development of ESRD: A Nationwide Registry Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2016;67:601-8. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Raju TNK, Pemberton VL, Saigal S, et al. Long-Term Healthcare Outcomes of Preterm Birth: An Executive Summary of a Conference Sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. J Pediatr 2017;181:309-18. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crump C, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA. Gestational age at birth and mortality in young adulthood. JAMA 2011;306:1233-40. 10.1001/jama.2011.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Statistics Sweden. The Swedish Medical Birth Register. www.socialstyrelsen.se/register/halsodataregister/medicinskafodelseregistret/inenglish accessed 1 Aug 2018.

- 19. Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008;371:75-84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsai WC, Wu HY, Peng YS, et al. Risk Factors for Development and Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Exploratory Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3013. 10.1097/MD.0000000000003013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McClellan WM, Flanders WD. Risk factors for progressive chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003;14(Suppl 2):S65-70. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000070147.10399.9E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xia J, Wang L, Ma Z, et al. Cigarette smoking and chronic kidney disease in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017;32:475-87. 10.1093/ndt/gfw452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley, 1987. 10.1002/9780470316696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li R, Chambless L. Test for additive interaction in proportional hazards models. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:227-36. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. VanderWeele TJ. Causal interactions in the proportional hazards model. Epidemiology 2011;22:713-7. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31821db503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grambsch PM. Goodness-of-fit and diagnostics for proportional hazards regression models. Cancer Treat Res 1995;75:95-112. 10.1007/978-1-4615-2009-2_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marsál K, Persson PH, Larsen T, Lilja H, Selbing A, Sultan B. Intrauterine growth curves based on ultrasonically estimated foetal weights. Acta Paediatr 1996;85:843-8. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14164.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vlasschaert ME, Bejaimal SA, Hackam DG, et al. Validity of administrative database coding for kidney disease: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 2011;57:29-43. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gasparini A, Evans M, Coresh J, et al. Prevalence and recognition of chronic kidney disease in Stockholm healthcare. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016;31:2086-94. 10.1093/ndt/gfw354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vikse BE, Irgens LM, Leivestad T, Hallan S, Iversen BM. Low birth weight increases risk for end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;19:151-7. 10.1681/ASN.2007020252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hirano D, Ishikura K, Uemura O, et al. Pediatric CKD Study Group in Japan in conjunction with the Committee of Measures for Pediatric CKD of the Japanese Society of Pediatric Nephrology Association between low birth weight and childhood-onset chronic kidney disease in Japan: a combined analysis of a nationwide survey for paediatric chronic kidney disease and the National Vital Statistics Report. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016;31:1895-900. 10.1093/ndt/gfv425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Manley BJ, Doyle LW, Davies MW, Davis PG. Fifty years in neonatology. J Paediatr Child Health 2015;51:118-21. 10.1111/jpc.12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tita AT, Landon MB, Spong CY, et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network Timing of elective repeat cesarean delivery at term and neonatal outcomes. N Engl J Med 2009;360:111-20. 10.1056/NEJMoa0803267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Crump C, Sundquist K, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Early-term birth (37-38 weeks) and mortality in young adulthood. Epidemiology 2013;24:270-6. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318280da0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Morgan C, Al-Aklabi M, Garcia Guerra G. Chronic kidney disease in congenital heart disease patients: a narrative review of evidence. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2015;2:27. 10.1186/s40697-015-0063-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chevalier RL, Thornhill BA, Forbes MS, Kiley SC. Mechanisms of renal injury and progression of renal disease in congenital obstructive nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol 2010;25:687-97. 10.1007/s00467-009-1316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wong MG, The NL, Glastras S. Maternal obesity and offspring risk of chronic kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 2018;23(Suppl 4):84-7. 10.1111/nep.13462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Glastras SJ, Chen H, Pollock CA, Saad S. Maternal obesity increases the risk of metabolic disease and impacts renal health in offspring. Biosci Rep 2018;38:BSR20180050. 10.1042/BSR20180050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Herrera-Garcia G, Contag S. Maternal preeclampsia and risk for cardiovascular disease in offspring. Curr Hypertens Rep 2014;16:475. 10.1007/s11906-014-0475-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Koleganova N, Piecha G, Ritz E. Prenatal causes of kidney disease. Blood Purif 2009;27:48-52. 10.1159/000167008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Luyckx VA, Brenner BM. Low birth weight, nephron number, and kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2005;Aug(97):S68-77. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Merlet-Bénichou C, Gilbert T, Vilar J, Moreau E, Freund N, Lelièvre-Pégorier M. Nephron number: variability is the rule. Causes and consequences. Lab Invest 1999;79:515-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kuure S, Vuolteenaho R, Vainio S. Kidney morphogenesis: cellular and molecular regulation. Mech Dev 2000;92:31-45. 10.1016/S0925-4773(99)00323-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fanos V, Loddo C, Puddu M, et al. From ureteric bud to the first glomeruli: genes, mediators, kidney alterations. Int Urol Nephrol 2015;47:109-16. 10.1007/s11255-014-0784-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Faa G, Gerosa C, Fanni D, et al. Marked interindividual variability in renal maturation of preterm infants: lessons from autopsy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2010;23(Suppl 3):129-33. 10.3109/14767058.2010.510646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sutherland MR, Gubhaju L, Moore L, et al. Accelerated maturation and abnormal morphology in the preterm neonatal kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;22:1365-74. 10.1681/ASN.2010121266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rhone ET, Carmody JB, Swanson JR, Charlton JR. Nephrotoxic medication exposure in very low birth weight infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2014;27:1485-90. 10.3109/14767058.2013.860522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.March of Dimes. PeriStats. www.marchofdimes.com/Peristats/. accessed 1 Aug 2018.

- 49. Zeitlin J, Szamotulska K, Drewniak N, et al. Euro-Peristat Preterm Study Group Preterm birth time trends in Europe: a study of 19 countries. BJOG 2013;120:1356-65. 10.1111/1471-0528.12281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Carmody JB, Charlton JR. Short-term gestation, long-term risk: prematurity and chronic kidney disease. Pediatrics 2013;131:1168-79. 10.1542/peds.2013-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li C, Wen XJ, Pavkov ME, et al. Awareness of kidney disease among US adults: Findings from the 2011 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Am J Nephrol 2014;39:306-13. 10.1159/000360184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hsu RK, Powe NR. Recent trends in the prevalence of chronic kidney disease: not the same old song. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2017;26:187-96. 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang L, Wang F, Wang L, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2012;379:815-22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Barfield WD, Henderson Z, et al. CDC Grand Rounds: Public Health Strategies to Prevent Preterm Birth. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:826-30. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6532a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Crump C. Medical history taking in adults should include questions about preterm birth. BMJ 2014;349:g4860. 10.1136/bmj.g4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Crump C. Birth history is forever: implications for family medicine. J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28:121-3. 10.3122/jabfm.2015.01.130317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Crump C, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Adult outcomes of preterm birth. Prev Med 2016;91:400-1. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wühl E, Schaefer F. Therapeutic strategies to slow chronic kidney disease progression. Pediatr Nephrol 2008;23:705-16. 10.1007/s00467-008-0789-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Luyckx VA, Perico N, Somaschini M, et al. writing group of the Low Birth Weight and Nephron Number Working Group A developmental approach to the prevention of hypertension and kidney disease: a report from the Low Birth Weight and Nephron Number Working Group. Lancet 2017;390:424-8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30576-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental information: additional tables 1 and 2