Abstract

In the era of drug‐eluting stents, the provisional stenting strategy has been established as the default strategy in percutaneous coronary intervention for bifurcation lesions. However, emerging evidence shows that, in selected situations, the complex strategy of stenting both vessels regardless could reduce side‐branch restenosis without penalty. In particular, the double kissing crush technique has been proven to outperform the provisional strategy and other complex strategies in randomized trials. In this review, we present the evidence comparing the 2 strategies and individual stenting techniques and discuss the roles of other optimization techniques such as final kissing balloon inflation, proximal optimization technique, intravascular ultrasonography, and optical coherence tomography. Finally, we suggest a practical approach for choosing the optimal strategy for intervention with coronary bifurcation lesions.

Keywords: Coronary artery disease, Coronary bifurcation lesion, Percutaneous coronary intervention

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronary bifurcation lesions are encountered in 15% to 20% of all percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI).1 Various PCI techniques for bifurcation lesions have been summarized previously.2 These techniques are categorized into (1) the provisional strategy, where 1‐stent stenting to the main vessel (MV) is followed by additional bailout stenting to the side branch (SB) only when the SB is compromised (hereafter referred to as the provisional strategy); and (2) the complex strategy, where both the MV and SB are stented, regardless, usually beginning with SB stenting (hereafter referred to as the complex strategy).

In this article we evaluate the clinical evidence for various strategies and techniques. We also describe the roles of other optimization techniques and propose our practical approach.

2. PROVISIONAL STRATEGY ESTABLISHED AS THE DEFAULT STRATEGY FOR BIFURCATION INTERVENTION

In the era of drug‐eluting stents (DES), numerous randomized studies have established the provisional strategy as the preferred strategy in PCI for bifurcation lesions (Table 1).1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 The provisional strategy has the advantage of shorter procedural and fluoroscopy times, smaller contrast volumes, and lower rates of procedure‐related increases in biomarkers of myocardial injury.1, 4, 13 In a meta‐analyses of 9 randomized trials,6 the provisional strategy, compared with the complex strategy, was associated with a reduced risk of either early or follow‐up myocardial infarction (MI) and with comparable risks of SB restenosis, target‐lesion revascularization, and target‐vessel revascularization (TVR). On the contrary, the complex strategy failed to consistently demonstrate its theoretical benefit of reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; Table 1). As a result, many authorities have recommended the provisional strategy as the default strategy for bifurcation intervention.14

Table 1.

Randomized Trials Comparing Provisional Strategy and Complex Strategy for Coronary Bifurcation Lesions

| Study Authors and Year | Comparison | Size | MACE % PS/CS | CV Death % PS/CS | MI % PS/CS | TVR % PS/CS | MV Restenosis % PS/CS | SB Restenosis % PS/CS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombo 200410 | CS vs PS | 85 | N/A | 0/1.6, P = NS | 9/11.1, P = NS | 9/11.1, P = NS | 4.8/5.7, P = NS | 14.2/21.8, P = NS |

| Pan 20049 | CS vs PS | 91 | 6.4/6.4 | 0/1.0 | 4/0 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 5/10 |

| NORDIC; Steigen 20061 | Crush, culotte, Y vs PS | 413 | 2.9/3.4 | 1.0/1.0, P = 1.00 | 0/0.5, P = 0.31 | 1.9/1.9, P = 0.99 | 4.6/5.1, P = 0.84 | 19.2/11.5, P = 0.062 |

| CACTUS; Colombo 20093 | Crush vs PS | 350 | 15.0/15.8, P = 0.95 | 0/0.5, P = 0.49 | 8.6/10.7, P = 0.59 | 7.5/7.9, P = 1.00 | 6.7/4.6, P > 0.05 | 14.7/13.2, P > 0.05 |

| BBK; Ferenc 200811 | T stenting vs PS | 202 | 12.9/11.9, P = 0.83 | 2.0/1.0, P = 1.00 | 1/2, P = 1.00 | N/A | 7.3/3.1, P = 0.17 | 9.4/12.5, P = 0.32 |

| Lin 201013 | DK crush, culotte, T vs PS | 108 | 11.1/38.9, P < 0.01 | 1.9/0, P = 1.00 | 1.9/1.9, P = 0.48 | 29.6/7.4, P < 0.01 | 14.8/9.3, P = 0.38 | 35.2/14.8, P = 0.015 |

| BBC‐ONE; Hildick‐Smith 20104 | Crush, culotte, T vs PS | 500 | 8.0/15.2, P = 0.009 | 0.4/0.8 | 3.6/11.2, P = 0.001 | 5.6/7.2, P = 0.43 | N/A | N/A |

| DKCRUSH II; Chen 200116 | DK crush vs PS | 390 | 17.3/10.3, P = 0.07 | 1.1/1.1, P = 1.00 | 2.2/3.2, P = 0.751 | 14.6/6.5, P = 0.017 | 9.7/3.8, P = 0.036 | 22.2/4.9, P < 0.001 |

| NORDIC Baltic IV; Kumsars 2013 | CS vs PS | 450 | 12.9/8.3, P = 0.12 | 0/0 | 1.8/0.9, P = 0.5 | 3.7/1.3, P = 0.11 | 2.6/2, P = NS | 20.3/5.2, P < 0.001 |

| PERFECT; Kim 201512 | Crush vs PS | 419 | 18.5/17.8, P = 0.85 | 0.5/0.9 P = 0.58 | 14.1/14.1, P = 0.98 | 3.4/2.9, P = 0.73 | 4.8/5.2, P = 0.90 | 8.3/3.9, P = 0.12 |

Abbreviations: BBC‐ONE, British Bifurcation Coronary Study: Old, New and Evolving Strategies; BBK, Bifurcations Bad Krozingen; CACTUS, Coronary Bifurcations: Application of the Crushing Technique Using Sirolimus‐Eluting Stents; CS, complex strategy; CV, cardiovascular; DK, double kissing; DKCRUSH, Double Kissing Crush vs Provisional Stenting Technique for Treatment of Coronary Bifurcation Lesions; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; MV, main vessel; NORDIC, Nordic Bifurcation Stent Technique Study; NS, not significant; PERFECT, Optimal Stenting Strategy for True Bifurcation Lesions; PS, provisional strategy; SB, side branch; TVR, target‐vessel revascularization.

Reasons for the lack of additional benefits from the complex strategy: (1) The majority of SBs have a normal fractional flow reserve and presumed good outcome irrespective of angiographic severity15; therefore, routine SB stenting may be unnecessary for the majority of patients; and (2) the provisional strategy has a high conversion rate to a 2‐stent technique of approximately 20% to 50%.3, 10, 11, 12 The converted subjects are presumably the ones at higher risk of adverse outcomes due to SB compromise, and this conversion neutralizes the benefit of the complex strategy.

3. WHY SHOULD THE COMPLEX STRATEGY BE CONSIDERED?

3.1. Larger Side Branches May Benefit in Particular From the Complex Strategy

A compromised large SB supplying a large myocardial territory (eg, the left circumflex artery in left main bifurcation lesions, or a large diagonal artery) can lead to significant clinical consequences. Many randomized studies excluded some1 or all3, 4, 11 left main bifurcation lesions; hence, the limitation of the provisional strategy in this group of patients is underrepresented in the literature. According to the large SB subgroup analysis of a meta‐analysis of 9 randomized trials,6 provisional strategy was associated with an increased risk of TVR (odds ratio: 2.27, 95% confidence interval: 1.27‐4.05, P = 0.01) and MV restenosis (odds ratio: 2.56, 95% confidence interval: 1.14‐5.78, P = 0.02) when compared with the complex strategy.

3.2. Facilitation for Future PCI

Compared with the provisional strategy, the complex strategy could result in larger minimum luminal diameter and less late luminal loss in the SB.1, 3, 13, 16 This would facilitate access to the SB for PCI should it become necessary in the future.

3.3. Complex Bifurcation Lesions or Extended Lesions in the Side Branch

When tackling bifurcation lesions with complex features or SB lesions extending beyond the ostium, 2‐stent stenting will eventually be required. In these situations, the complex strategy is preferable because bailout stenting of a compromised SB is often more challenging than stenting by a planned complex strategy. Some randomized studies either included only patients with focal stenosis at the SB ostium,3 or excluded complex bifurcation lesion with type C features or chronic total occlusions4; hence, the advantages of the complex strategy for these lesions are not adequately reflected by these studies.

3.4. Harmful Effects From Complex Strategy Are “Soft”

Two meta‐analyses6, 17 and the most recent prospective, single‐blind, randomized controlled study to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the Tryton Side Branch Stent (the Tryton Side Branch Stent Used With DES in Treatment of De Novo Bifurcation Lesions in the Main Branch and Side Branch in Native Coronaries [TRYTON] trial)8 were consistent in showing that the provisional and complex strategies did not differ in terms of death, need for revascularization, or stent thrombosis (ST). There was, however, a higher incidence of periprocedural MIs in the complex strategy. Fortunately, this increase in periprocedural MI rate did not translate to clinically significant outcomes.18 This is a well‐known discrepancy between biologic surrogate endpoints and hard clinical endpoints in coronary angioplasty clinical trials.19

3.5. Promising Benefits of a Specific Complex Strategy Technique

In the Double Kissing Crush vs Provisional Stenting Technique for Treatment of Coronary Bifurcation Lesions II (DKCRUSH‐II) trial,16 370 patients were randomized into either a provisional strategy group (PS group) or double‐kissing (DK) crush technique group (DK group). At 8 months, angiographic restenosis rates in the MV and SB were significantly lower in the DK group (3.8% vs 9.7%, P < 0.036; and 4.9% vs 22.2%, P < 0.001, respectively). At 12 months, TVR rates were significantly lower in the DK group than in the PS group (6.5% vs 14.6%; P < 0.017). The overall difference in MACE rates was statistically insignificant (Table 1). Perhaps more remarkably, procedural times, fluoroscopic times, and contrast volumes were similar in both groups, negating some of the oft‐cited advantages of the provisional strategy.

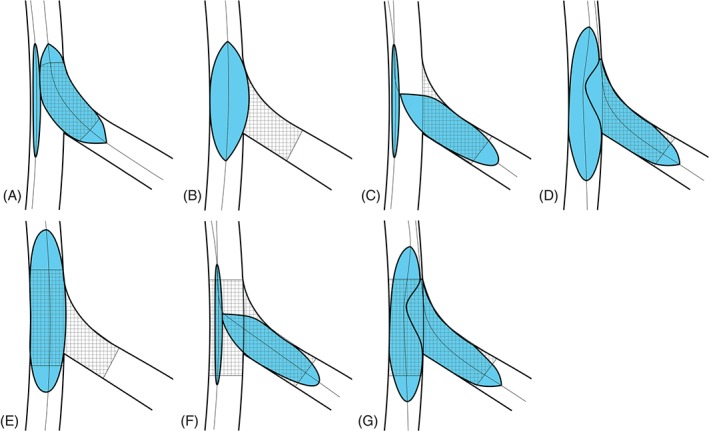

The DK crush technique, as described in Figure 1, emphasizes universal 2‐step kissing balloon inflations to achieve optimal carinal reconstruction. Earlier trials have shown that the performance of final kissing balloon inflation (FKBI) is a crucial step to ensure less SB restenosis, ST, and MACE.20, 21 In the DK crush technique, the SB guidewire would recross the stent strut 2 times and the balloons kiss 2 times, each time across 1 layer of stent strut.22 This optimizes the scaffolding with better stent expansion and apposition,22 and hence delivers better angiographic and clinical outcomes. One practical exception is for calcified complicated lesions; after the first crush and recrossing, balloon inflation in the SB stent may jeopardize the final effect in the main branch. In such cases, the provisional approach with or without rotablation may be optimal.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the DK crush technique. First, wire both vessels and perform predilation. (A) Deploy first stent to the SB with small protrusion into the MV. (B) Inflate a balloon in the MV to crush the SB stent. (C) Rewire the SB through the stent struts and perform balloon dilation. (D) Perform first KBI. (E) Deploy second stent to the MV. (F) Rewire the SB and dilate the stent struts. (G) Perform second (final) KBI. Finish with POT. Remarks: The main difference between crush and DK crush is the use of first KBI. Abbreviations: DK, double kissing; KBI, kissing balloon inflation; MV, main vessel; POT, proximal optimization technique; SB, side branch.

4. IS THERE A BEST TECHNIQUE AMONG THE VARIOUS COMPLEX STRATEGIES?

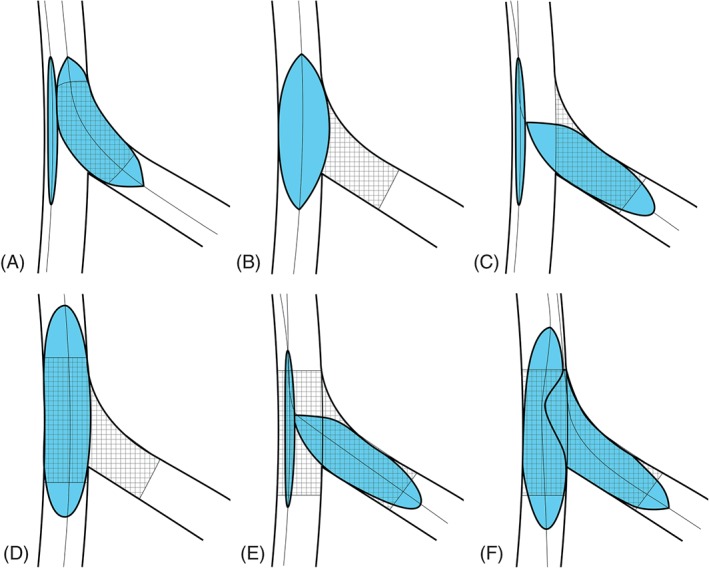

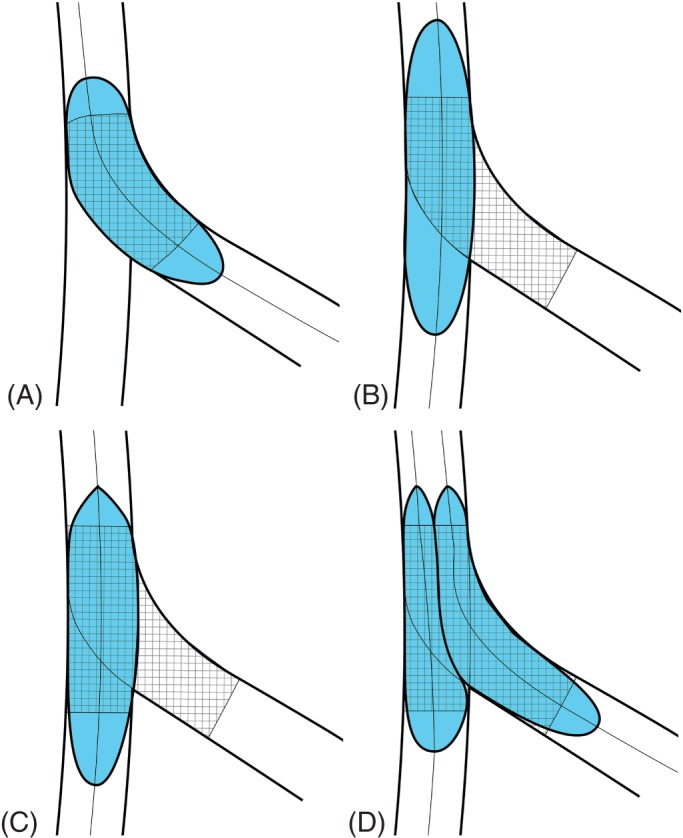

In the complex strategy, SB stenting is usually performed before MV stenting to avoid the substantial risk of failure to rewire the SB or deploy the SB stent after MV stenting. Within this framework, commonly employed techniques are the DK crush technique, the crush technique, and the culotte technique,2, 14 with technical aspects described in figures 1, 2, 3, respectively. There is no consensus as to which technique is clearly superior.14 A few prospective randomized studies comparing various complex strategies have been summarized Table 2. From these studies, the crush and culotte technique appeared to be of similar efficacy, whereas the DK crush technique encouragingly offered definite advantages.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the crush technique. First, wire both vessels and perform predilation. (A) Deploy first stent to the SB with small protrusion into the MV. (B) Inflate a balloon in the MV to crush the SB stent. (C) Rewire the SB through the stent struts and perform balloon dilation. (D) Deploy second stent to the MV. (E) Rewire the SB and dilate the stent struts. (F) Perform FKBI. Finish with POT. Abbreviations: FKBI, final kissing balloon inflation; MV, main vessel; POT, proximal optimization technique; SB, side branch.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the culotte technique. First, wire both vessels and perform balloon predilation. (A) Deploy first stent from proximal MV to SB. (B) Rewire distal MV and dilate through the stent struts. (C) Deploy second stent from proximal to distal MV. (D) Rewire the SB and perform FKBI. Finish with POT. Abbreviations: FKBI, final kissing balloon inflation; MV, main vessel; POT, proximal optimization technique; SB, side branch.

Table 2.

Randomized Trials Comparing Different Techniques of Complex Strategy for Coronary Bifurcation Lesions

| Study Authors and Year | Comparison | Size | MACE, % | CV Death, % | MI, % | TVR, % | MV Restenosis, % | SB Restenosis, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nordic Stent Technique Study; Erglis et al 200923 | Crush vs culotte | 424 | Crush 4.3, culotte 3.7; P = 0.87 | Crush 1.0, culotte 0.5; P = 0.62 | Crush 1.9, culotte 1.4; P = 0.72 | Crush 2.4, culotte 2.8; P = 0.77 | Crush 12.1, culotte 6.6; P = 0.10 | Crush 10.5, culotte 4.5; P = 0.046 |

| DKCRUSH I; Chen et al 200821 | Crush vs DK crush | 311 | Crush 24.4, DK crush 11.4; P = 0.02 | Crush 1.7, DK crush 0.6; P = 0.5 | Crush 14.6, DK crush 10.3; P = NS | Crush 21.9, DK crush 10.3; P = 0.03 | Crush 12.6, DK crush 8.5; P = NS | Crush 24.4, DK crush 12.3; P = 0.01 |

| DKCRUSH III; Chen et al 201325 | DK crush vs culotte | 419 | DK crush 6.2, culotte 16.3; P < 0.01 | DK crush 1.0, culotte 1.0; P = 1.00 | DK crush 3.3, culotte 5.3; P = 0.377 | DK crush 4.3, culotte 11.0; P = 0.016 | DK crush 1.14, culotte 0.57; P = 1.00 | DK crush 6.8, culotte 12.6; P = 0.037 |

| Zheng et al 201624 | Crush vs culotte | 300 | Crush 6.7, culotte 5.3; P = 0.48 | Crush 1.3, culotte 0.7; P = 0.624 | Crush 4.7, culotte 2.0; P = 0.335 | Crush 6.0, culotte 4.7; P = 0.607 | MV + SB restenosis, %: Crush 12.7, culotte 6.0; P = 0.047 | |

Abbreviations: CV, cardiovascular; DK, double kissing; DKCRUSH, Double Kissing Crush vs Provisional Stenting Technique for Treatment of Coronary Bifurcation Lesions; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; MV, main vessel; SB, side branch; TVR, target‐vessel revascularization.

The Nordic Stent Technique Study23 and Zheng et al24 randomized patients to stenting with the crush vs culotte technique. In both trials, rates of MACE and ST were similar between the 2 techniques, but the crush groups had higher restenosis rates. The failure in the crush group could be partly attributed to the significantly lower rates of FKBI in the crush group in both trials.

More important, evidence from randomized trials has shown the DK crush technique to be superior to the crush or culotte technique. In the DKCRUSH‐I study,21 311 patients were randomized to stenting with the crush technique vs the DK crush technique. After 8 months, the crush technique was associated with higher MACE (24.4% vs 11.4%; P = 0.02) and a lower target lesion revascularization–free survival rate (75.4% vs 89.5%; P = 0.002). In the DKCRUSH‐III study,25, 26 419 patients with unprotected left main bifurcation lesions were randomized to stenting with the DK crush technique or the culotte technique. At 1 year, the culotte group had a significantly higher rate of MACE (16.3% vs 6.2%; P = 0.001), mainly driven by an increased TVR (11.0% vs 4.3%; P = 0.016). At 3 years, the culotte group still had a significantly higher rate of MACE (23.7% vs 8.2%; P < 0.001), with higher rates of MI (8.2% vs 3.4%; P = 0.037) and TVR (18.8% vs 5.8%; P < 0.001), as well as definite ST (3.4% vs 0.0%; P = 0.007).

Given the advantages of the DK crush technique shown in head‐to‐head randomized trials, we recommend interventionists to give priority to this technique when employing the complex strategy for bifurcation stenting. Although it is sometimes viewed as being a “complex procedure,”2 similar angiographic success rates, complete revascularization rates, procedural times, and fluoroscopy times when compared with other techniques have been reported in the hands of skilled operators.25 It should be noted that advantages of the DK crush technique were derived from a series of randomized studies from one group of researchers, and some of these advantages were also “soft.” Therefore, further independent confirmation is warranted. Operators should be familiar with different bifurcation stenting techniques (both provisional and complex), because each technique has its merits and weaknesses.

5. SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR LEFT MAIN BIFURCATION LESIONS

Left main bifurcation lesions pose particular challenges for interventionists. A meta‐analysis of 17 trials involving PCI for the unprotected left main coronary artery revealed that distal lesion was the most significant predictor of repeated revascularization and overall MACE.27 To date, there are no dedicated randomized studies comparing the provisional vs the complex strategy in treating left main bifurcation lesions. In nonrandomized studies, the provisional strategy inconsistently appears to be superior to the complex strategy in terms of lower rates of TVR.7, 28 However, in the randomized DKCRUSH‐II study,16 which included 66 patients with left main bifurcation lesions (17% of all subjects), the complex strategy fared better.

Special considerations should be made for left main bifurcation lesions, because the left circumflex artery is almost always a major SB with large feeding territory. The loss of this SB is commonly associated with unacceptable risk, and this is particularly the case in the provisional strategy. The wider bifurcation angle of left main bifurcation lesions also poses a challenge to rewiring of the SB. Therefore, the complex strategy is highly recommended for bifurcation lesions with a high probability of SB occlusion (for example, true or extended left main bifurcation lesions) or when difficult SB rewiring is anticipated. The DKCRUSH‐III study25, 26 is the only randomized study comparing 2 complex stenting techniques dedicated to left main bifurcation lesions, and it showed the superiority of the DK crush technique compared with the culotte technique.

In addition, left main bifurcation lesions usually have a greater discrepancy in the reference diameter between the proximal and distal MV due to relatively larger SB. Sometimes the diffuse stenosis in the left main shaft can also prohibit accurate angiographic assessment of the proximal reference. In these situations, intravascular ultrasonography (IVUS) or optical coherence tomography (OCT) can provide valuable information to aid the intervention procedure.

6. OTHER OPTIMIZATION MEASURES

6.1. Final Kissing Balloon Inflation

Final kissing balloon inflation is not mandatory in 1‐stent implantation29 if the MV stent struts are not dilated to open up the SB. However, FKBI is mandatory if the SB is dilated through the MV stent struts, to correct MB stent distortion and expansion.30 Moreover, in avoiding incomplete apposition or expansion, the use of FKBI during any complex strategy was an independent predictor of good angiographic and clinical outcomes,5, 31 and thus should always be used in any complex strategy.

6.2. Proximal Optimization Technique

The proximal optimization technique (POT) refers to the expansion of the MV stent from the proximal edge to just proximal to the carina with a short oversized balloon. The balloon size can be estimated from proximal vessel reference or the Finet formula (0.678 × [distal MV diameter + SB diameter]).32 Theoretical benefits include enhancement of stent apposition, modification of SB ostium to take off more obliquely for easier rewiring, and correction of elliptical deformation of proximal MV stent.2, 14

6.3. Intravascular Ultrasonography

Intravascular ultrasonography can be a valuable adjunct for bifurcation intervention. Prior to stenting, IVUS can provide crucial information on minimum luminal area, reference vessel size (especially for diffusely diseased vessels), and lesion length and characteristics.33, 34 After stenting, IVUS can be used to evaluate the immediate results after stent deployment, adequacy of vessel expansion, and stent apposition.35 This additional information may confer clinical benefits on left main bifurcation stenting,36 and many authors and authorities recommended liberal use of IVUS in PCI for bifurcation lesions, in particular for left main bifurcation lesions.2, 14

6.4. Optical Coherence Tomography

Side branch rewiring through a distal stent cell of the MV stent can produce a shortest possible metallic carina and good stent coverage of the most proximal part of SB.37 Given its high resolution, OCT enables the operator to confirm the position of rewiring through the distal stent cell.38 It is also very useful in assessing reference vessel dimensions, and it is more sensitive than IVUS in assessing stent apposition and tissue prolapse after stenting.35 Although there are yet to be studies to show whether this translates into clinical benefits, the use of OCT should be considered as an adjunct when tackling complex bifurcation lesions.

6.5. Dedicated Bifurcation Stents

Dedicated bifurcation stents were designed to improve carinal reconstruction during PCI. Disappointingly, data from the randomized TRYTON trial8 favored provisional stenting as the preferred strategy to dedicated bifurcation stent. The Polish Bifurcation Optimal Stenting II (POLBOS II) trial39 and the Complex Bifurcation Lesions: A Comparison Between the AXXESS Device and Culotte Stenting: An Optical Coherence Tomography Study (COBRA) trial40 also failed to show any clinical benefit from dedicated bifurcation stents compared with conventional DES.

7. SELECTION OF PATIENTS WHO WOULD BENEFIT FROM COMPLEX STRATEGY

The decision to pursue a provisional or complex strategy is made prior to embarking on any stenting procedure; it is therefore important to identify at the outset patients who will benefit from a complex strategy.

A provisional strategy approach would suffice for the majority of patients with bifurcation lesions, where bailout SB stenting is performed only when significant SB dissection, flow limitation (Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction flow grade ≤2), or other evidence of myocardial ischemia develops.

The complex strategy, with dedicated stenting to both the MV and SB, can be beneficial to a selected group of patients with bifurcation lesions (particularly true bifurcation lesions). These patients are those with (1) a particularly important SB, including left main bifurcation lesion or a large SB supplying a large territory of myocardium; (2) SB with lesion extending beyond the ostium, or other complex features that require SB stenting, regardless of the result after MV stenting; and (3) bifurcation lesions of a single surviving vessel and/or lack of collaterals, where the importance of SB vessels is emphasized.

Among patients who would benefit from the complex strategy, the DK crush technique is emerging as a superior technique compared with other complex‐strategy techniques, with better preservation of stent patency and lower chances of future need for TVR.

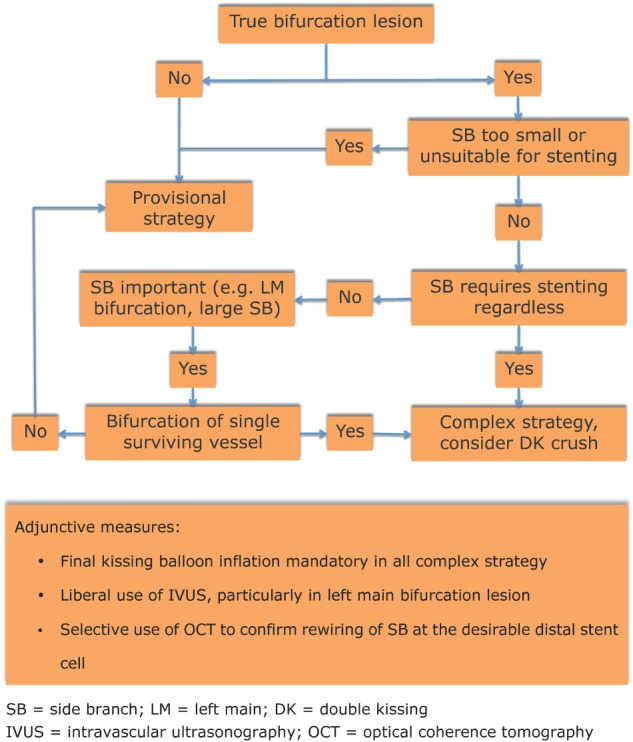

8. PROPOSED ALGORITHM BASED ON CURRENT EVIDENCE

We propose an algorithm for selecting the optimal strategy for intervention of coronary bifurcation lesions based on current evidence (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proposed algorithm according to current evidence. Abbreviations: DK, double kissing; IVUS, intravascular ultrasonography; LM, left main; OCT, optical coherence tomography; SB, side branch.

9. RECOMMENDATION FROM OTHERS

According to the European Bifurcations Club, the provisional strategy is still the standard for bifurcation stenting, recognizing the need for the complex strategy in a minority of lesions.14 The POT is mandatory, irrespective of the technique.14 Final kissing balloon inflation with high‐pressure balloon in case of SB stenting is mandatory.14 In case of left main bifurcation stenting, IVUS use is strongly advocated.14 Our approach has many similarities with these recommendations.

10. CONCLUSION

Although the provisional strategy has been established as the default strategy for coronary bifurcation intervention, the complex strategy is of particular benefit in selected groups of patients. The DK crush technique is a promising technique for producing better clinical outcomes. Final kissing balloon inflation, the POT, IVUS, and possibly OCT serve as important aids to optimize this complex procedure.

Ng AK, Jim M‐H. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Bifurcation: How Can We Outperform the Provisional Strategy?, Clin Cardiol 2016;39(11):684–691.

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1. Steigen TK, Maeng M, Wiseth R, et al. Randomized study on simple versus complex stenting of coronary artery bifurcation lesions: the Nordic bifurcation study. Circulation . 2006;114:1955–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roh JH, Kim YH. Percutaneous treatment of left main and non–left main bifurcation coronary lesions using drug‐eluting stents. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther . 2016;14:229–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Colombo A, Bramucci E, Sacca S, et al. Randomized study of the crush technique versus provisional side‐branch stenting in true coronary bifurcations: the CACTUS (Coronary Bifurcations: Application of the Crushing Technique Using Sirolimus‐Eluting Stents) study. Circulation . 2009;119:71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hildick‐Smith D, de Belder AJ, Cooter N, et al. Randomized trial of simple versus complex drug‐eluting stenting for bifurcation lesions: the British Bifurcation Coronary Study: old, new, and evolving strategies. Circulation . 2010;121:1235–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Niemela M, Kervinen K, Erglis A, et al. Randomized comparison of final kissing balloon dilatation versus no final kissing balloon dilatation in patients with coronary bifurcation lesions treated with main vessel stenting: the Nordic‐Baltic Bifurcation Study III. Circulation . 2011;123:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gao XF, Zhang YJ, Tian NL, et al. Stenting strategy for coronary artery bifurcation with drug‐eluting stents: a meta‐analysis of nine randomised trials and systematic review. EuroIntervention . 2014;10:561–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang J, Liu S, Geng T, et al. One‐stent versus two‐stent techniques for distal unprotected left main coronary artery bifurcation lesions. Int J Clin Exp Med . 2015;8:14363–14370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Genereux P, Kumsars I, Lesiak M, et al. A randomized trial of a dedicated bifurcation stent versus provisional stenting in the treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2015;65:533–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pan M, de Lezo JS, Medina A, et al. Rapamycin‐eluting stents for the treatment of bifurcated coronary lesions: a randomized comparison of a simple versus complex strategy. Am Heart J . 2004;148:857–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Colombo A, Moses JW, Morice MC, et al. Randomized study to evaluate sirolimus‐eluting stents implanted at coronary bifurcation lesions. Circulation . 2004;109:1244–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferenc M, Gick M, Kienzle RP, et al. Randomized trial on routine vs provisional T‐stenting in the treatment of de novo coronary bifurcation lesions. Eur Heart J . 2008;29:2859–2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim YH, Lee JH, Roh JH, et al. Randomized comparisons between different stenting approaches for bifurcation coronary lesions with or without side branch stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv . 2015;8:550–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin QF, Luo YK, Lin CG, et al. Choice of stenting strategy in true coronary artery bifurcation lesions. Coron Artery Dis . 2010;21:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lassen JF, Holm NR, Banning A, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention for coronary bifurcation disease: 11th consensus document from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention . 2016;12:38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koo BK, Kang HJ, Youn TJ, et al. Physiologic assessment of jailed side branch lesions using fractional flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2005;46:633–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen SL, Santoso T, Zhang JJ, et al. A randomized clinical study comparing double kissing crush with provisional stenting for treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions: results from the DKCRUSH‐II (Double Kissing Crush versus Provisional Stenting Technique for Treatment of Coronary Bifurcation Lesions) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2011;57:914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brar SS, Gray WA, Dangas G, et al. Bifurcation stenting with drug‐eluting stents: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised trials. EuroIntervention . 2009;5:475–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leonardi S, Thomas L, Neely ML, et al. Comparison of the prognosis of spontaneous and percutaneous coronary intervention‐related myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2012;60:2296–2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moussa ID, Klein LW, Shah B, et al. Consideration of a new definition of clinically relevant myocardial infarction after coronary revascularization: an expert consensus document from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI). J Am Coll Cardiol . 2013;62:1563–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoye A, Iakovou I, Ge L, et al. Long‐term outcomes after stenting of bifurcation lesions with the “crush” technique: predictors of an adverse outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2006;47:1949–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen SL, Zhang JJ, Ye F, et al. Study comparing the double kissing (DK) crush with classical crush for the treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions: the DKCRUSH‐I bifurcation study with drug‐eluting stents. Eur J Clin Invest . 2008;38:361–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang JJ, Chen SL. Classic crush and DK crush stenting techniques. EuroIntervention. 2015;11(suppl V):V102–V105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Erglis A, Kumsars I, Niemela M, et al. Randomized comparison of coronary bifurcation stenting with the crush versus the culotte technique using sirolimus eluting stents: the Nordic stent technique study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zheng XW, Zhao DH, Peng HY, et al. Randomized comparison of the crush versus the culotte stenting for coronary artery bifurcation lesions. Chin Med J (Engl). 2016;129:505–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen SL, Xu B, Han YL, et al. Comparison of double kissing crush versus culotte stenting for unprotected distal left main bifurcation lesions: results from a multicenter, randomized, prospective DKCRUSH‐III study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1482–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen SL, Xu B, Han YL, et al. Clinical outcome after DK crush versus culotte stenting of distal left main bifurcation lesions: the 3‐year follow‐up results of the DKCRUSH‐III study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1335–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Biondi‐Zoccai GG, Lotrionte M, Moretti C, et al. A collaborative systematic review and meta‐analysis on 1278 patients undergoing percutaneous drug‐eluting stenting for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2008;155:274–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Palmerini T, Marzocchi A, Tamburino C, et al. Impact of bifurcation technique on 2‐year clinical outcomes in 773 patients with distal unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis treated with drug‐eluting stents. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gao Z, Xu B, Yang YJ, et al. Effect of final kissing balloon dilatation after one‐stent technique at left‐main bifurcation: a single center data. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015;128:733–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ormiston JA, Currie E, Webster MW, et al. Drug‐eluting stents for coronary bifurcations: insights into the crush technique. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv . 2004;63:332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roh JH, Santoso T, Kim YH. Which technique for double stenting in unprotected left main bifurcation coronary lesions? EuroIntervention. 2015;11(suppl V):V125–V128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Finet G, Gilard M, Perrenot B, et al. Fractal geometry of arterial coronary bifurcations: a quantitative coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound analysis. EuroIntervention. 2008;3:490–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Motreff P, Rioufol G, Gilard M, et al. Diffuse atherosclerotic left main coronary artery disease unmasked by fractal geometric law applied to quantitative coronary angiography: an angiographic and intravascular ultrasound study. EuroIntervention. 2010;5:709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maehara A, Mintz GS, Castagna MT, et al. Intravascular ultrasound assessment of the stenoses location and morphology in the left main coronary artery in relation to anatomic left main length. Am J Cardiol . 2001;88:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bezerra HG, Attizzani GF, Sirbu V, et al. Optical coherence tomography versus intravascular ultrasound to evaluate coronary artery disease and percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv . 2013;6:228–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. de la Torre Hernandez JM, Baz Alonso JA, Gomez Hospital JA, et al. Clinical impact of intravascular ultrasound guidance in drug‐eluting stent implantation for unprotected left main coronary disease: pooled analysis at the patient‐level of 4 registries. JACC Cardiovasc Interv . 2014;7:244–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Foin N, Torii R, Alegria E, et al. Location of side branch access critically affects results in bifurcation stenting: Insights from bench modeling and computational flow simulation. Int J Cardiol . 2013;168:3623–3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Alegria‐Barrero E, Foin N, Chan PH, et al. Optical coherence tomography for guidance of distal cell recrossing in bifurcation stenting: choosing the right cell matters. EuroIntervention . 2012;8:205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gil RJ, Bil J, Grundeken MJ, et al. Regular drug‐eluting stents versus the dedicated coronary bifurcation sirolimus‐eluting BiOSS LIM stent: the randomised, multicentre, open‐label, controlled POLBOS II trial. EuroIntervention. doi: 10.4244/EIJY15M11_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dubois C, Bennett J, Dens J, et al. Complex Coronary Bifurcation Lesions: randomized comparison of a strategy using a dedicated self‐expanding biolimus‐eluting stent versus a culotte strategy using everolimus‐eluting stents: primary results of the COBRA trial. EuroIntervention. 2016;11:1457–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]