ABSTRACT

New‐onset persistent left bundle branch block (NOP‐LBBB) is one of the most common conduction disturbances after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). We hypothesized that NOP‐LBBB may have a clinically negative impact after TAVI. To find out, we conducted a systematic literature search of the MEDLINE/PubMed and Embase databases. Observational studies that reported clinical outcomes of NOP‐LBBB patients after TAVI were included. The random‐effects model was used to combine odds ratios, risk ratios, or hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals. Adjusted HRs were utilized over unadjusted HRs or risk ratios when available. A total of 4049 patients (807 and 3242 patients with and without NOP‐LBBB, respectively) were included. Perioperative (in‐hospital or 30‐day) and midterm all‐cause mortality and midterm cardiovascular mortality were comparable between the groups. The NOP‐LBBB patients experienced a higher rate of permanent pacemaker implantation (HR: 2.09, 95% confidence interval: 1.12‐3.90, P = 0.021, I 2 = 83%) during midterm follow‐up. We found that NOP‐LBBB after TAVI resulted in higher permanent pacemaker implantation but did not negatively affect the midterm prognosis. Therefore, careful observation during the follow‐up is required.

Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has shown a comparable long‐term prognostic benefit compared with surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) for severe symptomatic aortic stenosis in both high and intermediate surgical risk.1, 2 However, several perioperative complications may diminish the benefit of TAVI and be observed more frequently than following SAVR. New‐onset persistent left bundle branch block (NOP‐LBBB) is one of the most frequent conduction disturbances observed following TAVI and could potentially attenuate the benefit of the procedure.3, 4

Left bundle branch block causes electrical and mechanical dyssynchrony of the heart and various unfavorable hemodynamic effects.5 Previous studies have reported its negative prognostic impact on wide variety of cardiac disorders.6, 7, 8 Hoffman et al have reported that new‐onset LBBB or permanent pacemaker implantation (PPI) following TAVI was an independent risk factor for reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at 12‐month follow‐up.9 More importantly, according to Urena et al, NOP‐LBBB is associated with increased sudden cardiac death following TAVI.10 However, the prognostic impact of NOP‐LBBB following TAVI has not yet been established. Schymik et al have reported NOP‐LBBB as an independent risk factor for all‐cause mortality, but other studies have not found an association between NOP‐LBBB and all‐cause mortality.11, 12, 13 Because new‐onset LBBB is a rare conduction disturbance with no clear association with mortality following SAVR, it is paramount to assess the prognostic impact of NOP‐LBBB following TAVI to improve its outcomes.14

Therefore, we sought to summarize the prognostic impact of NOP‐LBBB following TAVI through a meta‐analysis.

Methods

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted through February 2016. We set neither time nor language restrictions. Two independent reviewers (T.A. and H.T.) searched the MEDLINE/PubMed and Embase databases. Search terms: (1) “left bundle branch block” or “LBBB” or “conduction”; and (2) “transcatheter aortic valve” or “percutaneous aortic valve” or “TAVI” or “TAVR” or “transfemoral” or “transapical” or “transsubclavian” or “transaortic” or “transcarotid” or “Sapien” or “CoreValve” or “balloon expandable” or “self expandable.” We utilized a 2‐level search strategy. Titles or abstracts were screened based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. When considered relevant, full manuscripts were reviewed. The references of manuscripts included for full review were manually reviewed. When data were considered to have an overlap, only the most recent study was included. A systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) and Meta‐analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines.15, 16

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) comparative study design; (2) the study population comprised patients with and without NOP‐LBBB (defined as postprocedural onset and persistent at discharge) following TAVI for severe aortic stenosis; and (3) outcomes included perioperative (in‐hospital or 30‐day) all‐cause mortality and midterm (≥1‐year) all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality and PPI. Exclusion criteria were (1) single‐arm study of NOP‐LBBB patients with no comparison of groups; and (2) no clear definition as to whether LBBB was persistent or transient.

Data Extraction

Data from the included studies were filled into preformed Excel spreadsheets. These data included author(s), publication year, study location and design, baseline characteristics of patients, and outcomes of interest. We abstracted odds ratios, risk ratios (RRs), and hazard ratios (HRs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of perioperative and midterm outcomes of interest, respectively, for NOP‐LBBB vs non–NOP‐LBBB patients. When an HR was not described in the manuscript, it was calculated by using the methods reported by Tierney et al,17 if possible. If it was impossible to calculate an HR, a risk ratio was extracted instead of an HR. When adjusted RRs/HRs were available, they were preferentially abstracted and combined in a meta‐analysis. Data extraction from the studies was based on consensus between the 2 reviewers.

Outcomes

A primary outcome was midterm (≥1‐year) all‐cause mortality. Secondary outcomes were perioperative (in‐hospital or 30‐day) all‐cause mortality, midterm (≥1‐year) cardiovascular mortality, and need for PPI.

Statistical Analysis

Meta‐analyses were performed with Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3 (Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012, Copenhagen, Denmark) and Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis version 2 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ). The estimated pooled RR/HR was calculated by inverse variance weighted average of logarithmic RRs/HRs in the random‐effects model. Heterogeneity of the studies was assessed with the I 2 index, which indicates 25%, 50%, and 75% as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Sensitivity analysis was performed by eliminating each study one at a time to assess its effect on the results. Significant heterogeneity was considered to be present when the P value was <0.05. Publication bias was evaluated visually by assessing the funnel plot and quantitatively with the Egger test when ≥10 studies were included in a meta‐analysis (http://handbook.cochrane.org); however, publication bias was not assessed, as <10 studies were included. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Search Result

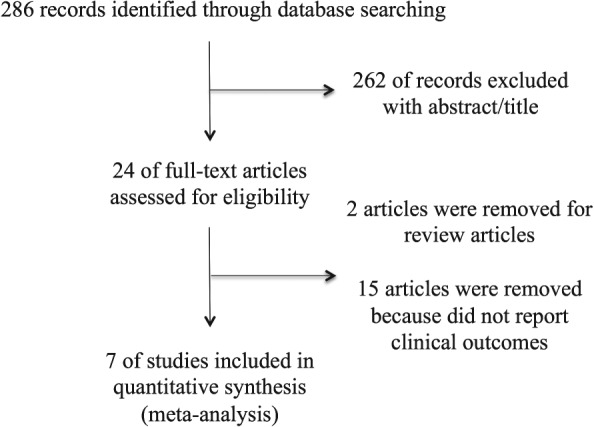

We identified 7 comparative studies3, 4, 11, 12, 13, 18, 19 including a total of 4049 patients (807 patients with NOP‐LBBB and 3242 patients without NOP‐LBBB). The diagnosis criteria for LBBB were based on the recommendations from the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation/Heart Rhythm Society20 in 4 studies3, 4, 13, 18 and from the World Health Organizational/International Society and Federation for Cardiology21 in 2 studies.11, 19 One study12 did not detail the diagnosis criteria. The study‐selection process is shown in Figure 1. Details of included studies are summarized in the Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for study selection.

Table 1.

Basic Information on Included Studies and Patient Characteristics

| Author | Year | Study Design | NOP‐LBBB Definition | NOP‐LBBB Cohort | Non–NOP‐LBBB Cohort | Follow‐up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nazif | 2014 | Prospective, PARTNER trial | New LBBB present on discharge or 7‐day ECG | 121 | 1030 | 12 months |

| Carrabba | 2015 | Prospective, single‐center | New LBBB that persisted at discharge | 34 | 58 | 12 months |

| Houthuizen | 2014 | Prospective, multicenter | New LBBB that persisted at 1 year | 111 | 365 | Median 898 and 944 days for non–NOP‐LBBB (either did not develop new‐onset LBBB or transient LBBB) and 914 days for NOP‐LBBB |

| Urena | 2014 | Prospective, multicenter | New LBBB that persisted at discharge | 79 | 589 | Median 13 months (IQR, 3–27 months) |

| Schymik | 2015 | Prospective, Karlsruhe registry | New LBBB that persisted at discharge | 197 | 437 | 12 months |

| Franzoni | 2013 | Unclear, single‐center | New LBBB that persisted at discharge | 41 | 197 | 12 months |

| Testa | 2013 | Prospective, multicenter | New LBBB that persisted at discharge | 224 | 594 | 12 months |

| Author | Patient Age | Male Sex, % | HTN, % | DM, % | CAD, % | PAD, % | CKD, % | Logistic EuroSCORE | TF Access, % | Valve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nazif | 84.2 ± 7.2 | 43.7 | 92.6 | 37.5 | 37.7 (CABG), 38.1 (PCI) | 43.0 | 15.8 (Cr ≥2.0 mg/dL) | 24.7 ± 15.6b | 56.6 | ESV 100% |

| Carrabba | 81 ± 6.3 | 52 | 60.0 | 30 | 41.3 (CABG and PCI) | 9.8 | 18.5 | 20 ± 14 | 97 | MCRS 100% |

| Houthuizen | Median 81 (IQR, 77–85) | 43.7 | NR | 26.9 | 59.7 (CABG and PCI) | 25.6 | 1.10a (IQR, 0.86–1.41) | 16.4 (IQR, 10.1–25.4) | 63.2 | ESV 53.2%, MCRS 46.8% |

| Urena | 80.7 ± 8.2 | 48.7 | 81.4 | 30.5 | 33.1 (CABG) | NR | 43.9 | 21.2 ± 14.1 | 54.3 | ESV 100% |

| Schymik | 82.02 ± 4.46 | 38.3 | NR | 33.8 | 15.1 (CABG) | 12.9 | 5.8 (Cr ≥2.2 mg/dL) | 21.71 ± 13.14 | NR | ESV 80.8%, MCRS 19.2% |

| Franzoni | 79.4 ± 7.6 | 53.8 | 75.2 | 27.3 | 39.1% (CAD) | NR | 55.5 | 22.4 ± 15.1 | NR | ESV 63.4%, MCRS 36.6% |

| Testa | 82 ± 6.5 | 45.5 | NR | 24.4 | 30.2% (previous PCI) | 19.6 | NR | 23.41 ± 11.3 | 88.3 | MCRS 100% |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; Cr, creatinine; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECG, electrocardiogram; ESV, Edwards Sapien valve; EuroSCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; HTN, hypertension; IQR, interquartile range; LBBB, left bundle branch block; MCRS, Medtronic CoreValve Revalving System; NOP‐LBBB, new‐onset persistent left bundle branch block; NR, not reported; PAD, peripheral artery disease; PARTNER, Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SD, standard deviation; TF, transfemoral.

Continuous numbers are expressed as either mean ± SD or median (IQR).

Cr (mg/dL).

EuroSCORE.

Meta‐analysis of Outcomes

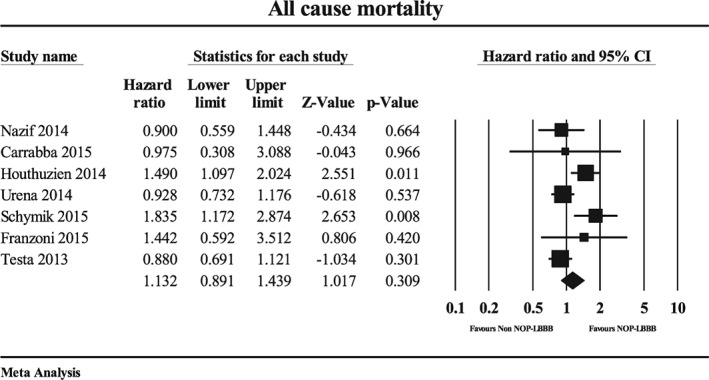

The midterm (≥1‐year) all‐cause mortality rate (807 and 3242 patients with and without NOP‐LBBB, respectively) was 24.4% in the NOP‐LBBB group and 20.9% in the non–NOP‐LBBB group. There was no significant difference in midterm all‐cause mortality between the NOP‐LBBB and non–NOP‐LBBB groups (HR: 1.13, 95% CI: 0.89‐1.44, P = 0.31, I 2 = 59.7%; Figure 2). There was significant heterogeneity observed (P = 0.021). Sensitivity analyses did not significantly alter the result.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for midterm (≥1‐year) all‐cause mortality in the NOP‐LBBB and non–NOP‐LBBB groups. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NOP‐LBBB, new‐onset persistent left bundle branch block.

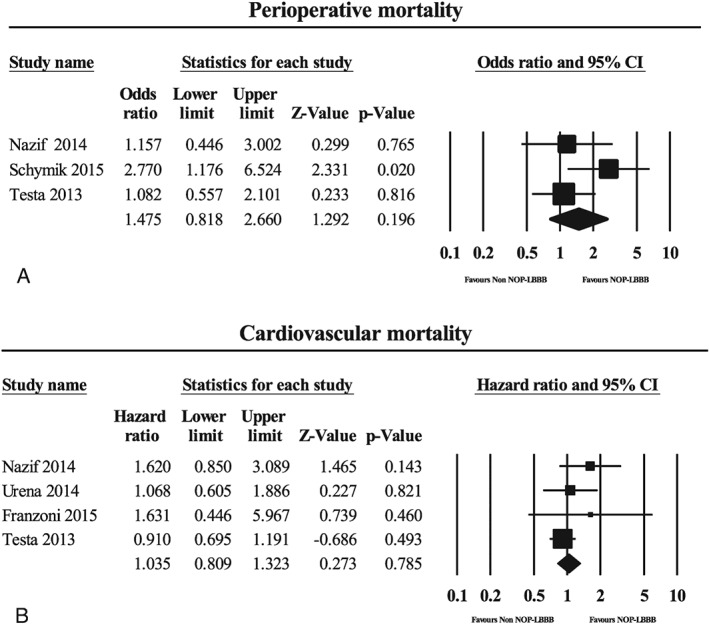

Perioperative all‐cause mortality (542 and 2061 patients with and without NOP‐LBBB, respectively) was 5.5% in the NOP‐LBBB group and 3.8% in the non–NOP‐LBBB group. There was no significant difference in perioperative all‐cause mortality between the NOP‐LBBB and non–NOP‐LBBB groups (odds ratio: 1.48, 95% CI: 0.82‐2.66, P = 0.20, I 2 = 36.6%; Figure 3A). No significant heterogeneity was observed, and subsequent sensitivity analyses demonstrated similar results.

Figure 3.

Forest plots for (A) perioperative mortality and (B) midterm cardiovascular mortality in the NOP‐LBBB and non–NOP‐LBBB groups. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NOP‐LBBB, new‐onset persistent left bundle branch block.

The midterm cardiovascular mortality rate (465 and 2410 patients with NOP‐LBBB and without NOP‐LBBB, respectively) was 9.2% in the NOP‐LBBB group and 7.7% in the non–NOP‐LBBB group. There was no significant difference in midterm cardiovascular mortality between the NOP‐LBBB and non–NOP‐LBBB groups (HR: 1.04, 95% CI: 0.81‐1.32, P = 0.79, I 2 = 6.0; Figure 3B). No significant heterogeneity was observed, and subsequent sensitivity analyses indicated similar results.

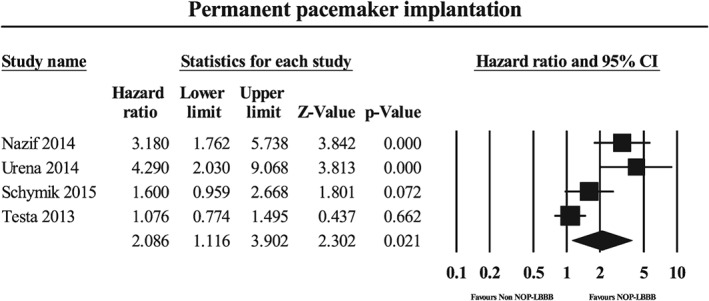

The NOP‐LBBB patients (n = 621) required more frequent PPI than did the non–NOP‐LBBB patients (n = 2650) during midterm follow‐up (HR: 2.09, 95% CI: 1.12‐3.90, P = 0.021, I 2 = 83%; Figure 4). There was significant heterogeneity (P = 0.001). The sensitivity analysis showed an insignificant result when studies by Nazif, Urena, or Schymik10, 11, 13 were removed.

Figure 4.

Forest plot for repeat hospitalization during midterm follow‐up in the NOP‐LBBB and non–NOP‐LBBB groups. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NOP‐LBBB, new‐onset persistent left bundle branch block.

Discussion

The main findings of our meta‐analysis are that NOP‐LBBB patients experience PPI more frequently during midterm follow‐up, and NOP‐LBBB after TAVI was not associated with perioperative and midterm all‐cause mortality, as well as midterm cardiovascular mortality.

Permanent Pacemaker Implantation in New‐Onset Persistent Left Bundle Branch Block Cohort

The NOP‐LBBB patients had a higher PPI rate during the follow‐up. High heterogeneity was observed (I 2 = 83%, P = 0.001). Self‐expandable balloon was a risk of both NOP‐LBBB and PPI,11, 18 and we consider that the significant heterogeneity is mainly because the implanted prosthesis differs considerably among studies, as summarized in the Table 1. The main risks for PPI after TAVI include preexistent right bundle branch block, self‐expandable prosthesis valve, and depth of implantation.22, 23 New‐onset LBBB was a predictive factor of high‐grade atrioventricular (AV) block following TAVI.24 Some reports showed that complete AV block, Mobitz type second‐degree AV block, and sinus‐node dysfunction were the common indications for PPI following TAVI.25 These data are, however, scarce for NOP‐LBBB patients who require PPI after TAVI. The main indications for PPI during the follow‐up in NOP‐LBBB patients in the present meta‐analysis were in agreement with those in past reports.25 The cause of the higher PPI rate in NOP‐LBBB patients is likely multifactorial. Patients who developed NOP‐LBBB may represent those with underlying conduction vulnerability, and therefore they may be susceptible to developing further conduction abnormalities during the midterm follow‐up.

Meta‐analysis was not performed for hospitalization in patients who developed NOP‐LBBB after TAVI because of insufficient data. The NOP‐LBBB patients had a higher hospitalization rate in 2 studies included in our meta‐analysis, although this was not statistically significant.10, 13 Patients with new‐onset LBBB and left‐axis deviation after SAVR suffer adverse events more frequently.26 Wider QRS duration in patients with NOP‐LBBB following TAVI was an independent risk of all‐cause mortality or admission due to heart failure (HF).27 Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) has shown to be effective in reducing adverse events in LBBB patients.28 The benefit of CRT in NOP‐LBBB after TAVI is widely unknown. Meguro et al reported an effective CRT therapy for a patient with worse cardiac function with NOP‐LBBB after TAVI.29 Antonio et al reported duration of symptoms for <1 year to be an independent predictor of patients who respond better to CRT therapy.30 Because the nature of NOP‐LBBB is often unpredictable,31 further investigation to identify prolonged NOP‐LBBB is warranted in the future. Nombela‐Franco et al have reported readmission causes and rates in post‐TAVI patients. Nearly half of the patients experienced unplanned readmission; more than half (59%) of readmissions were due to noncardiac reasons and the rest were classified as cardiac. The main causes of noncardiac admission were respiratory diseases, infection, and bleeding.32 One possible explanation for increased admission in NOP‐LBBB patients is that these patients may be more vulnerable to HF exacerbation in the middle of these events (infection and bleeding). However, Urena et al and Testa et al reported no association between NOP‐LBBB and HF admission.13, 19 This may be due to the uncertain permanency of NOP‐LBBB.

New‐Onset Persistent Left Bundle Branch Block and Mortality

Perioperative and midterm all‐cause mortality, as well as midterm cardiovascular mortality, did not differ between the NOP‐LBBB and non–NOP‐LBBB groups. Right bundle branch block as well as LBBB have been associated with increased mortality.33, 34

Urena et al have reported that NOP‐LBBB is associated with decreased LVEF and poorer functional status at 1‐year follow‐up.13 In TAVI patients, lower LVEF is a negative prognostic factor.35 Also, patients with poor functional status have a 2‐fold increase of death following TAVI.36 Furthermore, LBBB is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in a half of patients with chronic HF.37 However, results of our meta‐analysis proved the association of NOP‐LBBB with neither all‐cause nor cardiovascular mortality. There are several potential reasons for our observation. First, we included studies reporting outcomes of “persistent” (continuing until discharge or ≥7 days) new‐onset LBBB. The natural course of NOP‐LBBB, however, is unclear. Nazif et al have reported a decrease in proportion of patients with LBBB from 10.5% at discharge to 8.5% at 6 to 12 months.3 Testa et al reported similar LBBB rates at discharge and 30 days after TAVI.19 The lack of data regarding the natural course of NOP‐LBBB may be one of the reasons for inconsistent results of mortality. Results of the study by Houthuizen et al showed a significant increase in mortality in the NOP‐LBBB group, when NOP‐LBBB was defined as LBBB persisting during 1‐year follow‐up.18 Furthermore, TAVI patients with underlying chronic LBBB have increased 1‐year mortality.38 This finding may also support the idea that unclear persistency of NOP‐LBBB may be one of the reasons for inconsistency of mortality in NOP‐LBBB following TAVI. However, limited data suggest that a high proportion of NOP‐LBBB patients will remain in LBBB.3, 19 Second, most of the studies reported 1‐year (not beyond) mortality. The study by Houthizen et al had the longest follow‐up duration among included studies and revealed increased mortality in NOP‐LBBB patients. A study reported that the mean duration to develop HF in LBBB patients was 3.3 years.39 It would be interesting to know if longer duration of follow‐up will result in different mortality rates. Third, because of the uncertainty of the NOP‐LBBB course, PPI often may be overused in these patients. Ramazzina et al reported that out of 17 patients who had PPI for new‐onset LBBB, none of them required >1% of ventricular pacing; whereas of those who required PPI for atrioventricular conduction disorder, 83% (10/12) required >1% of ventricular pacing based on pacemaker interrogation.40 This may suggest that PPI is overused in LBBB after TAVI and these patients may not benefit from PPI. Last, no studies have clearly reported whether the LBBB was strict or nonstrict. It was reported that strict LBBB patients had greater mechanical dyssynchrony compared with nonstrict LBBB patients.41 However, Sundh et al have reported that the majority of the new‐onset LBBB following TAVI met the strict LBBB criteria, and therefore we consider that the difference between strict and nonstrict LBBB criteria would have minimal effects on our outcomes.42

Study Limitations

This study possesses all the inherent bias associated with meta‐analysis. First, this was a meta‐analysis of observational studies and therefore susceptible to bias. Secondly, we abstracted and then combined “unadjusted” RR/HR when “adjusted” ones were unavailable. However, excluding “unadjusted” RR/HR could lead to greater bias in favor of NOP‐LBBB. When an “unadjusted” RR/HR is not statistically significant, often it may not be incorporated into a multivariate analysis and not reported in the manuscript. Third, although we mounted a rigorous effort in search of published manuscripts, we cannot totally exclude the possibility of publication bias. Fourth, most of the studies included had a follow‐up period of only 1 year. Finally, the meta‐analysis for perioperative mortality only included a limited number of studies (total of 3) and the pooled‐effect size was associated with a wide 95% CI. Therefore, the result must be interpreted with caution. However, there was no significant heterogeneity observed, and subsequent sensitivity analysis showed the same result. This implies that the result is robust.

Conclusion

New‐onset persistent left bundle branch block after TAVI was associated with an increased rate of PPI but did not negatively affect midterm all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality. Careful monitoring is required for indication of PPI during follow‐up. Longer follow‐up is warranted to further assess the impact of NOP‐LBBB.

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, et al; PARTNER 1 Trial Investigators . 5‐Year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2477–2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barbanti M, Petronio AS, Ettori F, et al. 5‐Year outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation with CoreValve prosthesis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1084–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nazif TM, Williams MR, Hahn RT, et al. Clinical implications of new‐onset left bundle branch block after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: analysis of the PARTNER experience. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1599–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carrabba N, Valenti R, Migliorini A, et al. Impact on left ventricular function and remodeling and on 1‐year outcome in patients with left bundle branch block after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Askenazi J, Alexander JH, Koenigsberg DI, et al. Alteration of left ventricular performance by left bundle branch block simulated with atrioventricular sequential pacing. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mozid AM, Mannakkara NN, Robinson NM, et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with left bundle branch block versus ST‐elevation myocardial infarction referred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Coron Artery Dis. 2015;26:17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Supariwala AA, Po JR, Mohareb S, et al. Prevalence and long‐term prognosis of patients with complete bundle branch block (right or left bundle branch) with normal left ventricular ejection fraction referred for stress echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2015;32:483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lund LH, Benson L, Ståhlberg M, et al. Age, prognostic impact of QRS prolongation and left bundle branch block, and utilization of cardiac resynchronization therapy: findings from 14 713 patients in the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:1073–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoffmann R, Herpertz R, Lotfipour S, et al. Impact of a new conduction defect after transcatheter aortic valve implantation on left ventricular function. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:1257–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Urena M, Webb JG, Eltchaninoff H, et al. Late cardiac death in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement: incidence and predictors of advanced heart failure and sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:437–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schymik G, Tzamalis P, Bramlage P, et al. Clinical impact of a new left bundle branch block following TAVI implantation: 1‐year results of the TAVIK cohort. Clin Res Cardiol. 2015;104:351–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Franzoni I, Latib A, Maisano F, et al. Comparison of incidence and predictors of left bundle branch block after transcatheter aortic valve implantation using the CoreValve versus the Edwards valve. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:554–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Urena M, Webb JG, Cheema A, et al. Impact of new‐onset persistent left bundle branch block on late clinical outcomes in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation with a balloon‐expandable valve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Poels TT, Houthuizen P, Van Garsse LA, et al. Frequency and prognosis of new bundle branch block induced by surgical aortic valve replacement. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47:e47–e53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W65–W94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta‐analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta‐analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, et al. Practical methods for incorporating summary time‐to‐event data into meta‐analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Houthuizen P, van der Boon RM, Urena M, et al. Occurrence, fate and consequences of ventricular conduction abnormalities after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. EuroIntervention. 2014;9:1142–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Testa L, Latib A, De Marco F, et al. Clinical impact of persistent left bundle‐branch block after transcatheter aortic valve implantation with CoreValve Revalving System. Circulation. 2013;127:1300–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Surawicz B, Childers R, Deal BJ, et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part III: intraventricular conduction disturbances: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society . Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:976–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Willems JL, de Medina EO Robles, Bernard R, et al. Criteria for intraventricular conduction disturbances and pre‐excitation. World Health Organizational/International Society and Federation for Cardiology Task Force Ad Hoc. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5:1261–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guetta V, Goldenberg G, Segev A, et al. Predictors and course of high‐degree atrioventricular block after transcatheter aortic valve implantation using the CoreValve Revalving System. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:1600–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bleiziffer S, Ruge H, Hörer J, et al. Predictors for new‐onset complete heart block after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Akin I, Kische S, Paranskaya L, et al. Predictive factors for pacemaker requirement after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2012;12:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Siontis GC, Jüni P, Pilgrim T, et al. Predictors of permanent pacemaker implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing TAVR: a meta‐analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. El‐Khally Z, Thibault B, Staniloae C, et al. Prognostic significance of newly acquired bundle branch block after aortic valve replacement. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1008–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meguro K, Lellouche N, Yamamoto M, et al. Prognostic value of QRS duration after transcatheter aortic valve implantation for aortic stenosis using the CoreValve. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:1778–1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sipahi I, Chou JC, Hyden M, et al. Effect of QRS morphology on clinical event reduction with cardiac resynchronization therapy: meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2012;163:260.e3–267.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meguro K, Lellouche N, Teiger E. Cardiac resynchronization therapy improved heart failure after left bundle branch block during transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Invasive Cardiol. 2012;24:132–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. António N, Teixeira R, Coelho L, et al. Identification of 'super‐responders' to cardiac resynchronization therapy: the importance of symptom duration and left ventricular geometry. Europace. 2009;11:343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aktug Ö, Dohmen G, Brehmer K, et al. Incidence and predictors of left bundle branch block after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2012;160:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nombela‐Franco L, del Trigo M, Morrison‐Polo G, et al. Incidence, causes, and predictors of early (≤30 days) and late unplanned hospital readmissions after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1748–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xiong Y, Wang L, Liu W, et al. The prognostic significance of right bundle branch block: a meta‐analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin Cardiol. 2015;38:604–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Melgarejo‐Moreno A, Galcerá‐Tomás J, Consuegra‐Sánchez L, et al. Relation of new permanent right or left bundle branch block on short‐ and long‐term mortality in acute myocardial infarction bundle branch block and myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:1003–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eleid MF, Goel K, Murad MH, et al. Meta‐analysis of the prognostic impact of stroke volume, gradient, and ejection fraction after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:989–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Arnold SV, Spertus JA, Vemulapalli S, et al. Association of patient‐reported health status with long‐term mortality after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: report from the STS/ACC TVT Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:e002875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reil JC, Robertson M, Ford I, et al. Impact of left bundle branch block on heart rate and its relationship to treatment with ivabradine in chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:1044–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dizon JM, Nazif TM, Hess PL, et al. Chronic pacing and adverse outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Heart. 2015;101:1665–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schneider JF, Thomas HE Jr, Kreger BE, et al. Newly acquired left bundle‐branch block: the Framingham study. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90:303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ramazzina C, Knecht S, Jeger R, et al. Pacemaker implantation and need for ventricular pacing during follow‐up after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014;37:1592–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Andersson LG, Wu KC, Wieslander B, et al. Left ventricular mechanical dyssynchrony by cardiac magnetic resonance is greater in patients with strict vs nonstrict electrocardiogram criteria for left bundle‐branch block. Am Heart J. 2013;165:956–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sundh F, Simlund J, Harrison JK, et al. Incidence of strict versus nonstrict left bundle branch block after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Am J Cardiol. 2015;169:438–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]