ABSTRACT

Several studies investigated the role of physical activity in atrial fibrillation (AF), but the results remain controversial. We aimed to estimate the association between physical activity and incident AF, as well as to determine whether a sex difference existed. We systematically retrieved relevant studies from Cochrane Library, PubMed, and ScienceDirect through December 1, 2015. Data were abstracted from eligible studies and effect estimates pooled using a random‐effects model. Thirteen prospective studies fulfilled inclusion criteria. For primary analysis, neither total physical activity exposure (relative risk [RR]: 0.98, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.90‐1.06, P = 0.62) nor intensive physical activity (RR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.93‐1.25, P = 0.41) was associated with a significant increased risk of AF. In the country‐stratified analysis, the pooled results were not significantly changed. However, in the sex‐stratified analysis, total physical activity exposure was associated with an increased risk of AF in men (RR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.02‐1.37), especially at age <50 years (RR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.28‐1.95), with a significantly reduced risk of AF in women (RR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.87‐0.97). Additionally, male individuals with intensive physical activity had a slightly higher (although statistically nonsignificant) risk of developing AF (RR: 1.12, 95% CI: 0.99‐1.28), but there was a significantly reduced risk of incident AF in women (RR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.86‐0.98). Published literature supports a sex difference in the association between physical activity and incident AF. Increasing physical activity is probably associated with an increased risk of AF in men and a decreased risk in women.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia and has a significant risk for ischemic stroke. Although the etiology of AF is still ambiguous, multiple cardiovascular and as non‐cardiovascular risk factors (eg, obesity, alcohol abuse, excessive exercise, obstructive sleep apnea, and inflammation) of developing AF have been identified. To our knowledge, competitive athletes with a long‐term history of high‐intensity exercise have a higher risk of developing AF.1, 2 The potential mechanisms of exercise‐induced AF mainly include left atrial enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy, left ventricular dilation, fibrosis, and heightened parasympathetic tone.3 However, the association between physical activity and developing AF in nonathletes is still under debate. Physical activity is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscle leading to energy expenditure.4 Several earlier meta‐analyses and reviews have indicated inconsistent findings between physical activity and the risk of AF.2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 On the one hand, physical activity is not associated with an increased risk of AF,5, 6 and even moderate physical activity may reduce the risk of AF.2 Three reviews also have highlighted that several published studies provide little evidence for a causal effect between physical activity and development of AF.7, 8, 9 On the other hand, long‐term high‐intensity exercise is associated with an increased risk of AF.2, 5 However, there are several limitations in the previous meta‐analyses, such as the synthesis of limited prospective studies2, 6 and a high level of heterogeneity across studies.5 Since then, several new prospective studies have been published, but they have shown various views. Studies reporting physical activity and AF by sex increasingly have been emerging. Nevertheless, the quantitative synthetic data regarding the association between the sexes have not been well established. This updated meta‐analysis, therefore, aimed to estimate the effect of physical activity on the risk of incident AF in the general population, as well as to determine whether a sex difference existed in this association.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used for study selection: (1) studies estimating the association between physical activity and developing AF in the general population; (2) type of studies (randomized controlled trial [RCT], prospective cohort study, or nested case‐control study); and (3) studies providing the multivariate‐adjusted relative risks (RRs)/hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) studies reporting AF individuals with mitral or aortic valve heart disease, or individuals with postoperative AF; (2) studies on professional athletes; (3) studies not reporting AF in controls, and traditional case‐control studies; (4) certain publication types (eg, letters, case reports, comments); and (5) studies with insufficient or duplicative data.

Literature Search Strategy

Relevant English literatures were systematically retrieved form the Cochrane Library, PubMed, and Science Direct databases through December 1, 2015. The following broad search terms restricted to humans were used (“atrial fibrillation,” “atrial flutter,” “physical activity,” and “exercise”). Then, further research was performed using reference lists, relevant journals, and conference abstracts. All studies that met the inclusion criteria were considered eligible for this meta‐analysis.

Data Abstraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (W.‐G.Z. and R.W.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of studies. When the necessary information was unapparent, we comprehensively reviewed the full text. For each study, basic characteristics were abstracted including the first author and year of publication, participants (sample size, sex, age, and country of origin), the follow‐up duration, categorization of physical activity, ascertainment of physical activity and AF, and adjustments for confounding factors. The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale was used for assessing the quality of all included cohort studies, involving selection of cohorts, comparability of cohorts, and assessment of outcome.10 Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (K.H.).

Risk of Bias and Consistency Test

To assess the potential risk of publication bias, we visually inspected funnel plots, as recommended by the Cochrane collaboration (http://www.cochrane‐handbook.org). Statistical heterogeneity was calculated by consistency test using the Cochrane Q test complemented with the I2 statistic. The I2 values of ≤25%, 50%, and ≥75% represent low, moderate, and high inconsistency, respectively. When there was no significant heterogeneity, a fixed‐effects meta‐analysis model would be chosen. In this meta‐analysis, the populations across studies were very different and there was no strict definition of physical activity, so only a random‐effects model should be used to pool such highly heterogeneous studies.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) software, version 5.30 (the Nordic Cochrane Centre, the Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). All studies used a categorical variable for physical activity, and the maximally adjusted RRs of the extreme groups (the most vs the least physically active groups) were used for the current analyses. The maximally adjusted RRs with 95% CIs for incident AF were the effect estimates, and the HRs were deemed equivalent to RRs. For each study, the corresponding natural logarithm (Ln[RR]) and standard error (SE) were calculated and then pooled by RevMan 5.3 software. To examine the influence of each study on the pooled results, the sensitivity analysis was performed. We also conducted the subgroup analyses by country and sex. A P value ≤0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Study Selection

A flowchart illustrating each stage of the systematic review process can be found elsewhere (see Supporting Information, Figure, in the online version of this article). We initially identified 3349 studies through electronic searching, 2312 of which were excluded based on title and abstract screening. We then looked at the remaining full text of 1037 potentially relevant studies and excluded 860 studies for not involving physical activity and AF. Finally, 177 studies were assessed for eligibility, and 13 studies (total number of participants 568 072) fulfilled the inclusion criteria (2 post‐hoc analyses of RCT,11, 12 10 prospective cohort studies,13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and 1 prospective case‐control study23). Eight studies included populations in the United States.11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 21, 23 Five studies examined the association between physical activity and developing AF in men (n = 81 027),12, 17, 18, 20, 22 and 5 studies examined this association in women (n = 131 729).11, 14, 15, 20, 22 Ten studies evaluated the association between total physical activity exposure and the risk of AF,11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 21, 23 whereas 11 studies evaluated the association between intensive physical activity (vigorous, high intensity, or heavy workload) and the risk of AF.11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 The duration of follow‐up varied from 5 to 15 years. Ascertainment of physical activity was conducted through a questionnaire in all studies, and categorization of physical activity was defined differently in each study. Table 1 summarizes the basic characteristics of these included studies.

Table 1.

Basic Characteristics of 13 Included Studies in the Meta‐analysis

| Study Author, Year | Region | Age, y | Male sex, % | Participants, n | Follow‐up Duration, y | PA Ascertainment | Categorization of PA | AF Ascertainment | Adjustments | NOS Items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frost, 2005 | Denmark | 50–65 | 51 | 20 343 | 5.7 | Questionnaire | Work‐related PA: (1) sedentary (predominantly sitting position); (2) sedentary (predominantly standing position); (3) light workload; and (4) heavy workload | AF identified from Danish National Registry with ICD‐8/10 codes and single reviewer checked for incident AF in medical records. | Age, body height, BMI, smoking, consumption of alcohol, SBP, treatment for HTN, total serum cholesterol, duration of sporting activities, and level of education | 9 stars |

| Mozaffarian, 2008 | United States | ≥65 | 42 | 982 | 12 | Leisure‐time activity and exercise: at baseline, and at the end of third and seventh annual visits using questionnaire | (1) No leisure‐time PA; (2) leisure‐time activity (low intensity); (3) leisure‐time activity (medium intensity); and (4) leisure‐time activity (high intensity) | Annual resting 12‐lead ECG, hospital records discharge diagnosis for all hospitalizations | Age, sex, race, enrollment site, education, smoking status, pack‐years of smoking, CHD, chronic pulmonary disease, DM, alcohol use, and β‐blocker use | 8 stars |

| Aizer, 2009 | United States | 52 | 100 | 8448 | 12 | Questionnaires at 3 and 9 years after enrollment | (1) No exercise; (2) exercise to break sweat <1 d/wk; (3) exercise to break sweat 1–2 d/wk; (4) exercise to break sweat 3–4 d/wk; and (5) exercise to break sweat 5–7 d/wk | Annual questionnaire to report any new medical condition, including specific question about AF at 15, 17, 18, and 19 y after enrollment. Self‐report was validated by chart and ECG reviews. | Age, treatment assignment, BMI, DM, HTN, hyperlipidemia, MI, alcohol intake, smoking habits, fish consumption, multivitamin intake, vitamin C intake, vitamin E intake, LVH, HF, and evidence of CVD | 9 stars |

| Everett, 2011 | United States | 54.6 ± 7 | 0 | 13 899 | 14.4 | Questionnaires at baseline; at 36, 72, and 96 months; at the end of randomized portion of the study; and at the end of the 2 years of the observational study | Cumulative average PA: (1) <2 MET‐h/wk; (2) 2– < 5.9 MET‐h/wk; (3) 5.9– < 12 MET‐h/wk; (4) 12– < 23 MET‐h/wk; and (5) ≥23 MET‐h/wk | Questionnaire at the time of enrollment, at 48 mo and then annually thereafter. Medical charts and ECG reviews of those who self‐reported AF to confirm the diagnosis. | Age, randomized treatment, cholesterol, current smoking, past smoking, alcohol, DM, race, HTN, and BMI | 8 stars |

| Thelle, 2013 | Norway | 40–45 | 48 | 309 540 | 5 | Questionnaire on PA not validated | (1) Sedentary activity; (2) moderate activity; (3) intermediate activity; (4) intensive activity | AF was defined from flecainide use but not confirmed. | Age, year of screening, education, BMI, height, daily smoking, self‐reported CVD at screening, and dispensed cardiovascular drug | 7 stars |

| Ghorbani, 2014 | United States | 68 ± 9 | 100 | 28 169 | 8 | Assessed biennially via validated questionnaires including 11 recreational PA and 6 sedentary activity | MET‐h/wk of (1) sedentary activity; (2) total PA; (3) moderate PA; (4) vigorous PA | Unclear | Age, smoking, pulmonary disease, ASA use, caffeine intake, health‐seeking behavior index | 7 stars |

| Azarbal, 2014 | United States | 50–79 | 0 | 81 317 | 11.5 | Assessed using self‐reported questionnaires | Cumulative average PA: (1) No activity; (2) 0–3 MET‐h/wk; (3) >3–9 MET‐h/wk; (4) >9 MET‐h/wk | Among those with Medicare coverage, incident AF was identified by the first occurrence of ICD‐9 code 427.31. | Age, race, education, BMI, HTN, DM, hyperlipidemia, CHD, HF, PAD, smoking | 8 stars |

| Huxley, 2014 | United States | 45–64 | 45.3 | 14 219 | 9 | Measured using the modified Baecke questionnaire | (1) “Poor” (no moderate or vigorous); (2) “intermediate” (1–149 min/wk moderate or 1–74 min/wk vigorous); (3) “ideal” (1–149 min/wk moderate + vigorous) | (1) ECG done at study visits; (2) ICD‐9 code for AF (427.31 or 427.32); (3) AF listed as any cause of death on a death certificate | Age, race, sex, study site, education, income, prior CVD, cigarette smoking, height, and alcohol consumption | 9 stars |

| Knuiman, 2014 | Australia | 25–84 | 43.6 | 4267 | 15 | Exercise assessed in questionnaire with uncertain validation | (1) No activity; (2) vigorous exercise | AF from hospital admission and death records and based on ICD codes | Age, sex, height, HTN treatment, and BMI terms | 9 stars |

| Drca, 2014 | Sweden | Mean 60 | 100 | 44 410 | 12 | Participants completed a self‐administered questionnaire about their time spent on leisure‐time exercise throughout their lifetime | 5 groups depending on leisure‐time exercise level: (1) <1 h/wk; (2) 1 h/wk; (3) 2–3 h/wk; (4) 4–5 h/wk; (4) >5 h/wk | Cases of AF identified through computerized linkage with ICD‐9/10 codes | Age, education, smoking status and pack‐years of smoking, BMI, DM, history of HTN, history of CHD or HF, family history of MI, ASA use, and alcohol consumption | 8 stars |

| Calvo, 2015 | United States | 46 ± 10 | 87 | 172 | NA | A modified version of the validated Minnesota Leisure‐Time Physical Activity Questionnaire | (1) Accumulated lifetime endurance sport activity ≥2000 h; (2) accumulated lifetime endurance sport activity <2000 h; (3) sedentary individuals | NA | Age, height, BMI, waist circumference, hip circumference, OSA | 7 stars |

| Bapat, 2015 | United States | 62 ± 10 | 47 | 5793 | 7.7 | Filled out a survey documenting their baseline level of PA and the specific type and duration of PA | Total intentional exercise and vigorous PA; exercise intensity at 3 levels (heavy, moderate, or light) | Incident AF events were ascertained on the basis of hospital discharge and Medicare claims data for those enrolled in fee‐for‐service Medicare at any time during follow‐up. | Age, sex, race, education level, insurance status, cigarette smoking, resting heart rate, SBP, use of antihypertensives, LDL‐C, HDL‐C, BMI, DM, and LVH | 9 stars |

| Drca, 2015 | Sweden | Median 60 | 0 | 36 513 | 12 | Participants completed a self‐administered questionnaire about their time spent on leisure‐time exercise throughout their lifetime | 4 groups depending on leisure‐time exercise level: (1) <1 h/wk; (2) 1 h/wk; (3) 2–3 h/wk; (4) 4 h/wk | Cases of AF identified through computerized linkage with ICD‐9/10 codes. | Age, education, smoking status and pack years of smoking, BMI, DM, history of HTN, history of CHD or HF, family history of MI, ASA use, and alcohol consumption | 8 stars |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; ASA, aspirin; BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECG, electrocardiogram; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; HF, heart failure; HTN, hypertension; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MET, metabolic equivalent task; MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not available; NOS, Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PA, physical activity; PAD, peripheral artery disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Quality Assessment and Publication Bias

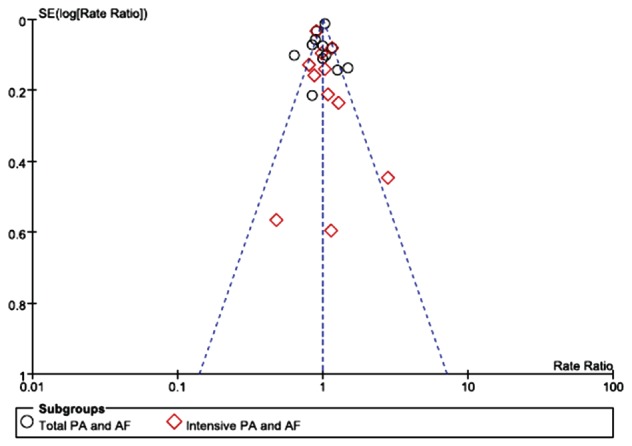

Assessment of the quality of all included studies was undertaken using Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale items designed for these studies. The reporting quality of the included studies was globally acceptable (Table 1). There was no major asymmetrical appearance in the funnel plot (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Funnel plot of all included studies for a bias analysis. Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; PA, physical activity; SE, standard error.

Total Physical Activity Exposure and Incident Atrial Fibrillation

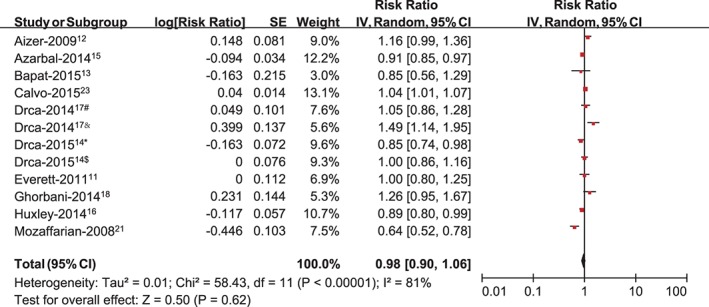

Ten studies evaluated the association between total physical activity exposure and the risk of AF.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 21, 23 A random‐effects model showed the pooled RR of AF was 0.98 (95% CI: 0.90‐1.06, P = 0.62; Figure 2) comparing the most physically active vs the least physically active groups. In the sensitivity analysis, the pooled results were not significantly changed. We then conducted a subgroup analysis by country, showing a pooled RR of AF was 0.95 (95% CI: 0.86‐1.06, P = 0.37) for American populations, and 1.05 (95% CI: 0.86‐1.27, P = 0.64) for non‐American populations (Table 2). We also performed the subgroup analysis by sex and observed a significant association between total physical activity exposure and developing AF both in men (RR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.02‐1.37, P = 0.02) and women (RR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.87‐0.97, P = 0.003). Overall, the random‐effects summary indicated that total physical activity exposure was associated with an increased risk of AF in men, especially at age <50 years (RR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.28‐1.95, P < 0.00001; Table 2), whereas it was associated with a reduced risk of AF in women.

Figure 2.

Meta‐analysis of the association between total PA exposure and developing AF, with #estimating the association between PA and AF in men at baseline (mean age 60 years); &estimating the association between PA and AF in men at age 30 years; *estimating the association between PA and AF in women at baseline (median age 60 years); and $estimating the association between PA and AF in women at age 30 years. Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse of the variance; PA, physical activity; SE, standard error.

Table 2.

Subgroup Analysis of Included Studies That Reported Estimates for PA and AF

| Total PA and AF | Intensive PA and AF | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled RR | 95% CI | I2 | P Value | Pooled RR | 95% CI | I2 | P Value | |

| Geographic region | ||||||||

| America | 0.95 | 0.86‐1.06 | 84% | 0.37 | 1.02 | 0.89‐1.17 | 60% | 0.75 |

| Non‐America | 1.05 | 0.86‐1.27 | 78% | 1.27 | 1.23 | 0.68‐2.21 | 89% | 0.49 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Ma | 1.18 | 1.02‐1.37 | 40% | 0.007 | 1.12 | 0.99‐1.28 | 0% | 0.08 |

| F | 0.92 | 0.87‐0.97 | 2% | 0.002 | 0.92 | 0.86‐0.98 | 0% | 0.009 |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval; F, female; M, male; PA, physical activity; RR, relative risk.

Total PA exposure was associated with an increased risk of AF in men, especially at age <50 years (RR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.28‐1.95, P < 0.00001).

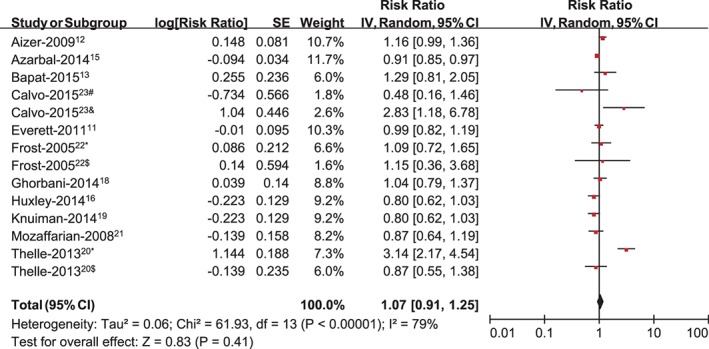

Intensive Physical Activity and Incident Atrial Fibrillation

Eleven studies evaluated the association between intensive physical activity and the risk of AF.11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 The pooled analysis suggested no significant increase in AF with intensive physical activity (RR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.93‐1.25, P = 0.41; Figure 3). In the sensitivity analysis, the results indicated there was still no significant increase in AF with intensive physical activity. We then conducted a subgroup analysis by country, showing a pooled RR for AF comparing the most vs the least physically active groups of 1.02 (95% CI: 0.89‐1.17, P = 0.75) for the American populations and 1.23 (95% CI: 0.68‐2.21, P = 0.49) for the non‐American populations (Table 2). In the subgroup analysis by sex (Table 2), male individuals with intensive physical activity had a slightly higher, although statistically nonsignificant, risk of developing AF (RR: 1.12, 95% CI: 0.99‐1.28, P = 0.08), whereas it was associated with a reduced risk of AF in women (RR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.86‐0.98, P = 0.009).

Figure 3.

Meta‐analysis of the association between intensive PA and developing AF, with #estimating the association between PA (high‐intensity exercise <2000 hours) and AF; &estimating the association between PA (high‐intensity exercise >2000 hours) and AF; *estimating the association between PA and AF in men; and $estimating the association between PA and AF in women. Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse of the variance; PA, physical activity; SE, standard error.

Discussion

In our current meta‐analysis, neither total physical activity exposure nor intensive physical activity was associated with a significant increased risk of AF, in agreement with the findings of earlier meta‐analyses by Kwok et al5 and Ofman et al.6 In the sensitivity analysis and country‐stratified analysis, the pooled results were not significantly changed. However, in the sex‐stratified analysis, total physical activity exposure was associated with an increased risk of AF in men, especially in individuals age <50 years, whereas it significantly reduced the risk of AF in women. In addition, male individuals with intensive physical activity had a slightly higher, although statistically nonsignificant, risk of developing AF, whereas there was a significantly reduced risk of AF in women. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first meta‐analysis regarding sex differences in the association between physical activity and AF in the general population.

Long‐term sport activity seems to elevate the risk of AF in competitive athletes.24, 25, 26, 27 The most possible mechanism of exercise‐induced AF may be related to increased parasympathetic tone.3 However, the association between physical activity and AF in the general population remains controversial. Our current analysis showed that increasing physical activity was probably associated with an increased risk of AF in men, especially at age <50 years. In the Physicians Health Study, a high frequency of vigorous exercise was associated with an increased risk of AF in men at <50 years of age.12 Drca et al17 also observed an increased risk of AF associated with high levels of leisure‐time exercise in men at age 30 years but not at an older age. Thelle et al20 showed a positive association between the risk of flecainide use (as a surrogate marker for AF) and physical activity in men. In a cohort of middle‐aged men, total physical activity was associated with a slightly higher, although statistically nonsignificant, risk of developing AF.18 Conversely, moderate physical activity seemed to decrease the risk of AF among older adults.17, 21 The different effects could be explained by the fact that in older ages, the positive effects of physical activity on risk factors of AF dominated over the potential negative effects. Major risk factors of incident AF may be favorably modified by physical activity,17, 28 and therefore increasing physical activity may have a protective effect against incident AF in older ages. Furthermore, the protective effects of exercise against vascular injury were significantly higher in older men.29 Also, the amount and intensity of physical activity in young men was higher than that in older men generally. High‐intensity exercise at a younger age could potentially increase the risk of AF, whereas lower‐intensity exercise at an older age could potentially decrease the risk.14

The association of exercise and AF has already been firmly established in males. Conversely, ongoing physical activity might be associated with lower risk of AF in females. The underlying mechanisms could be explained by sex differences in the cardiac adaptation to physical activity. After a comparable amount of exercise, male athletes have a more deleterious structural remodeling, including left atrial dilation, which may affect the risk of developing AF.30 In the experimental animal data, female rats show a decreased response to left ventricular pressure overload.31 Additionally, females produce less atrial electrophysiological changes in response to rapid atrial pacing and an increase in atrial pressure than do males.32 However, in some recent studies, the enhanced atrial proarrhythmogenic substrates have also been indicated in females. High‐intensity endurance exercise induces a transient, intensity‐dependent, systemic pro‐inflammatory status after exercise bouts, which may contribute to atrial structural remodeling. After similar amounts of exercise, the inflammation cascade could be amplified in females.33 Also, autonomic tone plays a critical role in exercise‐induced AF, and females have a deeper vagal enhancement than males.30 Nevertheless, sex differences in exercise‐induced AF could be explained by the different amount and intensity of physical activity.34 In general, exercise‐induced AF is associated with regular high‐intensity endurance activities. However, the amount and intensity of physical activity in males is usually much higher than that in females. In this regard, our meta‐analysis based on published literature indicated that women were not at an increased risk of AF. Of note, women are now engaged in more regular and more intense physical activity, such as marathon running and cycling. Further study should definitely keep an eye on the effect that more intense physical activity may have on development of AF in females.

Fitness is a set of attributes that one possesses or achieves from regular physical activity, including cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, body composition, and flexibility.4 Regular physical activity, as well as cardiorespiratory fitness, could increase individual fitness. Cumulative evidence on the inverse association between cardiorespiratory fitness and AF risk has been increasingly emerging.35, 36, 37, 38 Pathak et al36 reported that baseline fitness predicts future AF, and increasing fitness via exercise training is also associated with reduced AF recurrence. Other studies also demonstrated an inverse association between exercise capacity and AF risk,35, 37, 38 where cardiorespiratory fitness was measured indirectly by exercise duration38 or more directly by maximal oxygen uptake.35

Although the effects of physical activity on AF seem to exhibit a U‐shaped relationship in athletes and nonathletes,24, 25, 26, 27 the upper limit of the benefit of physical activity discriminating individuals at risk for exercise‐induced AF is still undefined. To date, epidemiological studies to identify this upper limit have provided conflicting data. Calvo et al23 showed an accumulated lifetime sport activity of 2000 hours was the upper limit of benefit, whereas Elosua et al26 demonstrated that a threshold of 1500 hours was associated with an increased risk of AF. Further study should be performed to identify the upper limit for better discriminating individuals at risk for exercise‐induced AF. Moreover, there is accumulating evidence that lifestyle modifications could help the prevention and treatment of AF among individuals at high risk.39 Four healthy lifestyle modifications (including regular physical activity duration for ≥20 min/d) are associated with a 50% reduced risk of AF.40 Therefore, before the upper limit of the benefit of physical activity is well established, we should not overestimate the increased risk of AF in men. Clinicians still should advise AF patients to participate in moderate physical activity to reduce incidence of cardiac arrhythmias and other cardiovascular diseases.

Study Limitations

Our meta‐analysis has several strengths. We included 2 post‐hoc analysis of RCTs and 11 prospective studies, and the number of participants was large enough. We excluded traditional case‐control studies, because they could create recall bias. Furthermore, all the included studies adjusted the potential confounding factors of AF. The observed association was therefore less likely due to confounding biases. Furthermore, this was the first meta‐analysis regarding the sex differences in the association between physical activity and AF in the general population. The sensitivity analysis showed the pooled results were stable. Our study also had several potential limitations. There was no strict definition of physical activity, which could have created confounding biases. Moreover, the duration of follow‐up and the method of AF ascertainment were highly variable, and we did not differentiate the subtypes of AF. Also, one‐time electrocardiographic screening for AF might miss a number of patients with asymptomatic paroxysmal AF. Finally, even though adjusted estimates for each study were used, the associations were so modest that they may easily be explained by residual confounding. Further study is needed to validate the potentially causal effects in the general population.

Conclusion

Overall, there was no significant association between physical activity and incident AF. Our main finding was that sex modified the association, such that in males, increasing activity was associated with higher risk of AF, whereas in females, it was associated with a significant protective effect.

Supporting information

Overview of the research strategy. Note: This is an overview of the number of studies included during each stage of the systematic review process.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Huiqiang Yu (School of Public Health, Nanchang University, Jiangxi, China) for help designing the search strategy and assistance in the consistency test for the included studies.

W.‐G.Z. and R.W. are co–first authors. K.H. was in charge of the entire project and revised the draft; W.‐G.Z. and X.Y. performed the systematic literature review, constructed the database, and analyzed the data. W.‐G.Z. and R.W. drafted the first version of the manuscript with the help of Y.D., Z.X., and X.Y. All authors took part in the interpretation of the results and prepared the final version.

The authors acknowledge support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (8153000545), National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program: 2013CB531103), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81370288).

The authors have no other funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Abdulla J, Nielsen JR. Is the risk of atrial fibrillation higher in athletes than in the general population? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Europace. 2009;11:1156–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nielsen J, Wachtell K, Abdulla J. The relationship between physical activity and risk of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Atr Fibrillation. 2013;5:20–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guasch E, Benito B, Qi X, et al. Atrial fibrillation promotion by endurance exercise: demonstration and mechanistic exploration in an animal model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health‐related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100:126–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kwok CS, Anderson SG, Myint PK, et al. Physical activity and incidence of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:467–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ofman P, Khawaja O, Rahilly‐Tierney CR, et al. Regular physical activity and risk of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:252–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Müller‐Riemenschneider F, Andersohn F, Ernst S, et al. Association of physical activity and atrial fibrillation. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9:605–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Graff‐Iversen S, Gjesdal K, Jugessur A, et al. Atrial fibrillation, physical activity and endurance training [article in English, Norwegian]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2012;132:295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Delise P, Sitta N, Berton G. Does long‐lasting sports practice increase the risk of atrial fibrillation in healthy middle‐aged men? Weak suggestions, no objective evidence. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2012;13:381–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle‐Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta‐analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Everett BM, Conen D, Buring JE, et al. Physical activity and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation in women. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:321–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aizer A, Gaziano JM, Cook NR, et al. Relation of vigorous exercise to risk of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1572–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bapat A, Zhang Y, Post WS, et al. Relation of physical activity and incident atrial fibrillation (from the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:883–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drca N, Wolk A, Jensen‐Urstad M, et al. Physical activity is associated with a reduced risk of atrial fibrillation in middle‐aged and elderly women. Heart. 2015;101:1627–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Azarbal F, Stefanick ML, Salmoirago‐Blotcher E, et al. Obesity, physical activity, and their interaction in incident atrial fibrillation in postmenopausal women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huxley RR, Misialek JR, Agarwal SK, et al. Physical activity, obesity, weight change, and risk of atrial fibrillation: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7:620–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Drca N, Wolk A, Jensen‐Urstad M, et al. Atrial fibrillation is associated with different levels of physical activity levels at different ages in men. Heart. 2014;100:1037–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ghorbani A, Willett W. Physical activity and incidence of atrial fibrillation: the Health Professionals Follow‐up Study. Circulation. 2014;129:P129–P427. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Knuiman M, Briffa T, Divitini M, et al. A cohort study examination of established and emerging risk factors for atrial fibrillation: the Busselton Health Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thelle DS, Selmer R, Gjesdal K, et al. Resting heart rate and physical activity as risk factors for lone atrial fibrillation: a prospective study of 309 540 men and women. Heart. 2013;99:1755–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mozaffarian D, Furberg CD, Psaty BM, et al. Physical activity and incidence of atrial fibrillation in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 2008;118:800–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Frost L, Frost P, Vestergaard P. Work‐related physical activity and risk of a hospital discharge diagnosis of atrial fibrillation or flutter: the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62:49–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Calvo N, Ramos P, Montserrat S, et al. Emerging risk factors and the dose‐response relationship between physical activity and lone atrial fibrillation: a prospective case‐control study. Europace. 2016;18:57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Molina L, Mont L, Marrugat J, et al. Long‐term endurance sport practice increases the incidence of lone atrial fibrillation in men: a follow‐up study. Europace. 2008;10:618–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mont L, Tamborero D, Elosua R, et al. Physical activity, height, and left atrial size are independent risk factors for lone atrial fibrillation in middle‐aged healthy individuals. Europace. 2008;10:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Elosua R, Arquer A, Mont L, et al. Sport practice and the risk of lone atrial fibrillation: a case‐control study [published correction appears in Int J Cardiol. 2007;123:74]. Int J Cardiol. 2006;108:332–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karjalainen J, Kujala UM, Kaprio J, et al. Lone atrial fibrillation in vigorously exercising middle aged men: case‐control study. BMJ. 1998;316:1784–1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cornelissen VA, Fagard RH. Effects of endurance training on blood pressure, blood pressure–regulating mechanisms, and cardiovascular risk factors. Hypertension. 2005;46:667–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang Z, Xia WH, Su C, et al. Regular exercise‐induced increased number and activity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells attenuates age‐related decline in arterial elasticity in healthy men. Int J Cardiol. 2013;165:247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wilhelm M, Roten L, Tanner H, et al. Gender differences of atrial and ventricular remodeling and autonomic tone in nonelite athletes. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:1489–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weinberg EO, Thienelt CD, Katz SE, et al. Gender differences in molecular remodeling in pressure overload hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:264–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tse HF, Oral H, Pelosi F, et al. Effect of gender on atrial electrophysiologic changes induced by rapid atrial pacing and elevation of atrial pressure. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:986–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gill SK, Teixeira A, Rama L, et al. Circulatory endotoxin concentration and cytokine profile in response to exertional‐heat stress during a multi‐stage ultra‐marathon competition. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2015;21:114–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thompson PD. Additional steps for cardiovascular health. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:755–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Khan H, Kella D, Rauramaa R, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and atrial fibrillation: a population‐based follow‐up study. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1424–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pathak RK, Elliott A, Middeldorp ME, et al. Impact of cardiorespiratory fitness on arrhythmia recurrence in obese individuals with atrial fibrillation: the CARDIO‐FIT Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:985–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pittaras A, Faselis C, Doumas M, et al. Fitness status and risk for atrial fibrillation. J Hypertens. 2015;33(suppl 1):e64. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Qureshi WT, Alirhayim Z, Blaha MJ, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and risk of incident atrial fibrillation: results from the Henry Ford Exercise Testing (FIT) Project. Circulation. 2015;131:1827–1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Menezes AR, Lavie CJ, De Schutter A, et al. Lifestyle modification in the prevention and treatment of atrial fibrillation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;58:117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Larsson SC, Drca N, Jensen‐Urstad M, et al. Combined impact of healthy lifestyle factors on risk of atrial fibrillation: prospective study in men and women. Int J Cardiol. 2016;203:46–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Overview of the research strategy. Note: This is an overview of the number of studies included during each stage of the systematic review process.