Abstract

Background

Despite evidence supporting the effectiveness of diabetic retinopathy screening (DRS) in reducing the risk of sight loss, attendance for screening is consistently below recommended levels.

Objectives

The primary objective of the review was to assess the effectiveness of quality improvement (QI) interventions that seek to increase attendance for DRS in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Secondary objectives were: To use validated taxonomies of QI intervention strategies and behaviour change techniques (BCTs) to code the description of interventions in the included studies and determine whether interventions that include particular QI strategies or component BCTs are more effective in increasing screening attendance; To explore heterogeneity in effect size within and between studies to identify potential explanatory factors for variability in effect size; To explore differential effects in subgroups to provide information on how equity of screening attendance could be improved; To critically appraise and summarise current evidence on the resource use, costs and cost effectiveness.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, ProQuest Family Health, OpenGrey, the ISRCTN, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO ICTRP to identify randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that were designed to improve attendance for DRS or were evaluating general quality improvement (QI) strategies for diabetes care and reported the effect of the intervention on DRS attendance. We searched the resources on 13 February 2017. We did not use any date or language restrictions in the searches.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs that compared any QI intervention to usual care or a more intensive (stepped) intervention versus a less intensive intervention.

Data collection and analysis

We coded the QI strategy using a modification of the taxonomy developed by Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) and BCTs using the BCT Taxonomy version 1 (BCTTv1). We used Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, Gender/sex, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, and Social capital (PROGRESS) elements to describe the characteristics of participants in the included studies that could have an impact on equity of access to health services.

Two review authors independently extracted data. One review author entered the data into Review Manager 5 and a second review author checked them. Two review authors independently assessed risks of bias in the included studies and extracted data. We rated certainty of evidence using GRADE.

Main results

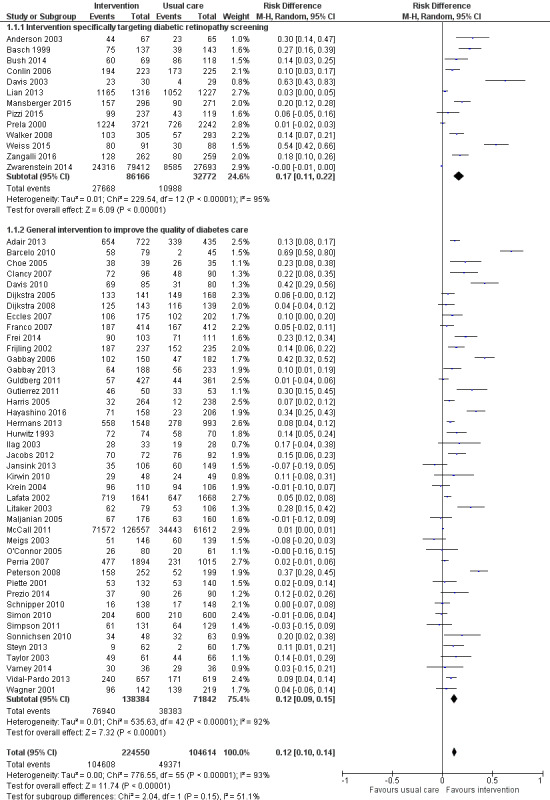

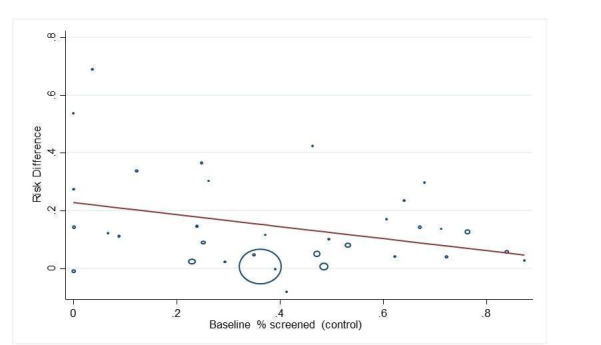

We included 66 RCTs conducted predominantly (62%) in the USA. Overall we judged the trials to be at low or unclear risk of bias. QI strategies were multifaceted and targeted patients, healthcare professionals or healthcare systems. Fifty‐six studies (329,164 participants) compared intervention versus usual care (median duration of follow‐up 12 months). Overall, DRS attendance increased by 12% (risk difference (RD) 0.12, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.10 to 0.14; low‐certainty evidence) compared with usual care, with substantial heterogeneity in effect size. Both DRS‐targeted (RD 0.17, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.22) and general QI interventions (RD 0.12, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.15) were effective, particularly where baseline DRS attendance was low. All BCT combinations were associated with significant improvements, particularly in those with poor attendance. We found higher effect estimates in subgroup analyses for the BCTs ‘goal setting (outcome)’ (RD 0.26, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.36) and ‘feedback on outcomes of behaviour’ (RD 0.22, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.29) in interventions targeting patients, and ‘restructuring the social environment’ (RD 0.19, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.26) and ‘credible source’ (RD 0.16, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.24) in interventions targeting healthcare professionals.

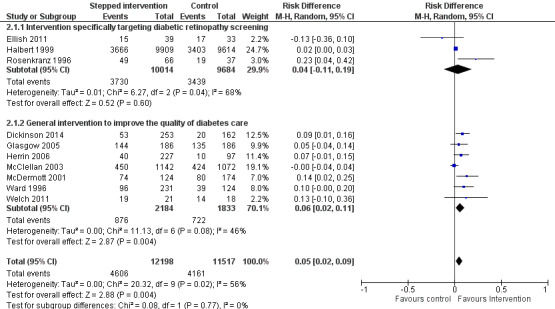

Ten studies (23,715 participants) compared a more intensive (stepped) intervention versus a less intensive intervention. In these studies DRS attendance increased by 5% (RD 0.05, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.09; moderate‐certainty evidence).

Fourteen studies reporting any QI intervention compared to usual care included economic outcomes. However, only five of these were full economic evaluations. Overall, we found that there is insufficient evidence to draw robust conclusions about the relative cost effectiveness of the interventions compared to each other or against usual care.

With the exception of gender and ethnicity, the characteristics of participants were poorly described in terms of PROGRESS elements. Seventeen studies (25.8%) were conducted in disadvantaged populations. No studies were carried out in low‐ or middle‐income countries.

Authors' conclusions

The results of this review provide evidence that QI interventions targeting patients, healthcare professionals or the healthcare system are associated with meaningful improvements in DRS attendance compared to usual care. There was no statistically significant difference between interventions specifically aimed at DRS and those which were part of a general QI strategy for improving diabetes care. This is a significant finding, due to the additional benefits of general QI interventions in terms of improving glycaemic control, vascular risk management and screening for other microvascular complications. It is likely that further (but smaller) improvements in DRS attendance can also be achieved by increasing the intensity of a particular QI component or adding further components.

Plain language summary

Interventions to increase attendance for diabetic retinopathy screening

What is the aim of this review? The aim of this review was to find out if interventions used to improve attendance for diabetic retinopathy screening are effective.

Key messages The results of this review found evidence that interventions that target patients, healthcare professionals or the healthcare system are likely to be effective for improving attendance for diabetic retinopathy screening compared to usual care. We found benefits for interventions that were specifically aimed at diabetic retinopathy screening, as well as those which were part of a general strategy to improve diabetes care. This is important, since more general strategies are associated with additional benefits, such as improving blood glucose control and increasing the detection of other diabetes‐related complications.

What was studied in the review? People with diabetes may lose vision as a result of the damaging effects of the disease on small blood vessels at the back of the eye (diabetic retinopathy). Screening for diabetic retinopathy to detect and treat early signs can prevent sight loss. However, screening attendance is variable and sight‐threatening changes may not be detected in good time.

This review looked at a variety of interventions to improve diabetic retinopathy screening.

What are the main results of the review? The Cochrane review authors found 66 relevant studies. Forty‐one studies were from the USA, 14 from Europe, three from Canada, three from Australia and five from elsewhere. Fifty‐six studies compared the intervention to improve screening attendance with usual care and 10 compared a more intensive to a less intensive intervention.

We found that interventions aimed at patients or healthcare professionals or both, or at the healthcare system were effective at improving screening attendance. Interventions aimed at improving the general quality of diabetes care worked as well as those specifically aimed at improving screening for retinopathy. On average, attendance increased by 12% compared with no intervention.

How up‐to‐date is this review? The Cochrane review authors searched for studies that had been published up to 13 February 2017.

Summary of findings

7. GRADE rating for economic outcomes.

| Resources and costs per participant | ||||||||||

|

Economic outcomes No of studies with evidence for the economic outcomes |

Design | Limitations/risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other factors | No of participants | Any Quality Improvement intervention | Usual care | Overall quality |

|

Resources used (staff time, equipment, consumables) (13 studies) Adair 2013Clancy 2007Davis 2010Eccles 2007Frei 2014Frijling 2002Krein 2004Litaker 2003Piette 2001Pizzi 2015Prezio 201Wagner 2001Walker 2008 |

RCTs | Yesa | Yes ( there was justification for variation based on setting) | No | No | Resources used varied due to settings and intervention strategy | 85 ‐ 20,000 | Wide variation in resources used for each study, hence difficult to collate the resource used as a single output | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW |

|

|

Staff/personnel costs; costs of treatment and care; cost of primary care; lost wages and lost productivity

(10 studies) Adair 2013Clancy 2007Davis 2010Eccles 2007Frijling 2002Litaker 2003Piette 2001Pizzi 2015Prezio 2014Walker 2008 |

RCTs | Yesa | Yes ( there was justification for variation based on setting) | No | No | Costs varied due to settings, level of experience and educational Background of personnel | 85 ‐ 20,000 | Wide variation in resources used from different interventions also made it difficult to derive average costs compared with usual care | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW |

|

|

Incremental cost effectiveness of interventions. (3 studies) Davis 2010Prezio 2014Walker 2008 |

RCTs | Yesa | No | No | No | None | 85 ‐ 603 | GBP 13,154 for promotion of self‐management GBP 73,683 for 5 years for face‐to‐face meeting GBP 18.77 for phone call |

⊕⊕⊕⊖ LOW |

|

a. Unclear risk from adequate masking (blinding), Unclear sequence generation and allocation concealment

Background

Description of the condition

Diabetic retinopathy is the most common microvascular complication of diabetes mellitus and a leading cause of blindness amongst the working‐age adult population in the Western world (Sivaprasad 2012). The duration of diabetes is the strongest predictor for the development and progression of retinopathy. Within 20 years of diagnosis, nearly all patients with type 1 diabetes and more than 60% of patients with type 2 have retinopathy (Fong 2004). A higher prevalence of diabetic retinopathy is found in people of South Asian, African and Latin American descent, compared to white populations (Sivaprasad 2012). Further risk factors for the development and progression of diabetic retinopathy include: poor glycaemic control, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia (Yau 2012). It has been estimated that globally approximately 93 million individuals may have some form of diabetic retinopathy, with 28 million suffering from the sight‐threatening end points of the disease (Yau 2012). There is limited evidence on the economic burden of diabetic retinopathy. One recent estimate for healthcare costs in Sweden was EUR 106,000 per 100,000 population a year, based upon a prevalence of diabetes of 4.8% (95% confidence interval 4.7 to 4.9) (Heintz 2010). These costs exclude cost impacts on those with diabetic retinopathy and their families.

Although effective treatments are available for sight‐threatening diabetic retinopathy in the form of laser photocoagulation (Evans 2014) and more recently the use of anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors (Virgili 2014), the success of these interventions is dependent on early detection and timely referral for treatment. Diabetic retinopathy screening (DRS) fulfils the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for a screening programme (Scanlon 2008): namely, diabetes‐associated visual impairment is an important public health problem; potentially sight‐threatening retinopathy has a recognisable latent stage; a universally accepted and effective treatment is available; and screening has been shown to be cost‐effective in terms of sight years preserved compared with no screening (Jones 2010). Annual or biennial DRS is recommended in many countries using a variety of screening modalities, including: ophthalmoscopy performed by a number of healthcare professionals (including ophthalmologists, optometrists, diabetic physicians) or using standard retinal photography or digital fundus imaging (American Diabetes Association 2015; Kristinsson 1995; Scanlon 2008). Recently, mathematical algorithms have been developed that provide individualised risk assessment for diabetic retinopathy and optimisation of screening intervals based on type and duration of diabetes, HbA1c, systolic blood pressure, gender and the presence and grade of retinopathy (Lund 2016).

Relatively few countries have introduced a national population‐based DRS programme, and in most parts of the world screening remains non‐systematic.

The reference standard for the detection of diabetic retinopathy consists of seven standard 35‐degree colour photographic fields as described by the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (EDTRS) research group (EDTRS 1991). However this technique is impractical for widespread retinopathy screening. Although ophthalmoscopy through dilated pupils has traditionally been the method of choice for opportunistic screening, the procedure varies in diagnostic accuracy depending on the particular technique used (direct or indirect ophthalmoscopy) or the experience of the healthcare professional performing the test (Hutchinson 2000). Recent developments in digital retinal photography have facilitated the rapid acquisition of high‐quality fundus images that can be stored and subsequently graded. Digital imaging combined with trained graders has been shown to be an effective screening tool to identify sight‐threatening retinopathy (Williams 2004), and is increasingly gaining acceptance for population screening (Kirkizlar 2013; Sharp 2003; Silva 2009; Taylor 2007).

Despite evidence supporting the effectiveness of DRS in reducing the risk of sight loss, screening coverage is consistently below recommended levels (Millett 2006; Paz 2006; Saadine 2008). The high rates of non‐attendance have major financial consequences. For example, the North and East Devon Diabetic Retinal Screening Service in the UK invited 22,651 people to participate in retinal screening between April 2009 and March 2010. Of those invited, 2137 (9.4%) failed to attend for their appointment after three reminders. With each appointment costing GBP 34 in 2009 and GBP 37 in 2010, the total cost of non‐attendance was GBP 78,259 (2009/2010 GBP) (Waqar 2012). Several factors have been shown to affect access and attendance for DRS, including ethnicity, younger age (less than 40 years), a longer duration of diabetes, and living in areas of high social deprivation (Byun 2013; Gulliford 2010; Hwang 2015; Kliner 2012).

Description of the intervention

Several interventions specifically aimed at improving DRS, including those targeting patients, health professionals or the healthcare system, have been shown to be effective in improving attendance across a range of retinopathy screening models (Zhang 2007). Examples of patient‐focused interventions include: (1) educational programmes to increase awareness of diabetic retinopathy and promote self‐management, and (2) the use of prompts/reminders. Provider‐focused interventions include: (1) clinician education, and (2) audit and performance feedback. System interventions include: (1) team changes; (2) establishing electronic registration and recall, and (3) the use of telemedicine.

In addition to strategies that specifically target DRS, general quality improvement (QI) implementation strategies for diabetes care may also be effective in improving screening coverage. A recent systematic review and meta‐analysis of trials assessing a number of predefined QI strategies to improve diabetes care reported that these were associated with a significant increase in DRS compared to usual care (risk ratio 1.22, 95% confidence interval 1.13 to 1.32) (Tricco 2012). However, this review did not include studies where interventions were solely targeted at patients, and the authors were unable to distinguish the effectiveness of individual QI components or identify potential effect modifiers. Furthermore, the review did not include an economic perspective.

How the intervention might work

Most studies assessing the effectiveness of interventions to improve diabetes care (including those delivered specifically to improve DRS) often involve multicomponent interventions that attempt to change the behaviour of healthcare professionals (e.g. advising patients to attend DRS) or patients (e.g. actually attending), or both. As there is no consistent association between the number of intervention components and their effectiveness (Grimshaw 2004), the ‘ideal’ number of components in such programmes is unknown. Furthermore, given the complexity of interventions tested to date, it is not always clear which specific components are the effective elements of these interventions (i.e. the 'active ingredients'). Hence, the content of complex behaviour change interventions has been referred to as a 'black box' (Grimshaw 2014). There is evidence that the more clearly the 'active' components of a complex intervention are described, the more readily the intervention may be delivered in an effective, consistent and cost‐effective manner (Michie 2009). Therefore, identification of the effective interventions for increasing attendance for DRS first requires clarity about intervention content and the functional relationship between components of interventions and the intended outcome. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) have developed a taxonomy that can be used to classify intervention content in systematic reviews (EPOC 2015). Although the EPOC taxonomy provides a common language and a useful summary description of the intervention, the taxonomy may not be sufficiently detailed to specify the components of the intervention clearly (Presseau 2015). A complementary approach is to provide a comprehensive categorisation of the ingredients of the intervention in terms of the behaviour change techniques (BCTs) used. BCTs are defined as the ‘observable, replicable and irreducible components of an intervention that are designed to alter or redirect causal processes regulating behaviour' (Michie 2013). Recently, a reliable taxonomy of 93 BCTs has been published (co‐developed by team member JF) to provide a common, consistent terminology (BCT Taxonomy version 1 (BCTTv1)), by which the component BCTs in complex interventions may be identified and described. Examples of BCT labels in this taxonomy include: ‘goal setting,’ ‘self monitoring,’ ‘providing feedback on behaviour’ and ‘problem solving'. Review team members (JP, NI and JG) have successfully demonstrated the feasibility of using the BCT taxonomy within trials of QI interventions for diabetes care (Presseau 2015).

Why it is important to do this review

Given the value of screening for reducing the risk of sight loss amongst people with diabetes, it is essential that attendance for DRS is maximised as far as available resources allow. Wide geographical variation in screening coverage has been reported, with associated inequalities in outcomes. Given the incremental costs (resource use) and benefits (effects) associated with interventions to improve attendance for DRS, it is important to consider whether such strategies are worthwhile.

By identifying the active components of interventions that increase attendance for screening, this review will contribute to the identification of implementation strategies for early detection of sight‐threatening retinopathy. Furthermore, by exploring the differential effects of interventions in particular subgroups the results may provide clues to help to reduce inequalities in screening attendance and determine the impact of inequity on intervention effectiveness and efficiency. Although there have been a number of systematic reviews on interventions to optimise adult screening programmes (Everett 2011; Holden 2010), it is likely that this evidence is not directly transferable to DRS. Screening for diabetic retinopathy differs from other forms of screening in that the target group already has significant contact with the healthcare system due to their underlying diabetes, and screening has to be life‐long (i.e. annual or biennial surveillance is necessary).

Objectives

The primary objective of the review was to assess the effectiveness of QI interventions that seek to increase attendance for DRS in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Secondary objectives:

To use validated taxonomies of QI intervention strategies and behaviour change techniques (BCTs) to code the description of interventions in the included studies and determine whether interventions that include particular QI strategies or component BCTs are more effective in increasing screening attendance;

To explore heterogeneity in effect size within and between studies to identify potential explanatory factors for variability in effect size;

To explore differential effects in subgroups to provide information on how equity of screening attendance could be improved;

To critically appraise and summarise current evidence on the resource use, costs and cost effectiveness.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered randomised controlled trials (RCTs), both individually randomised and cluster‐RCTs, conducted in a primary or secondary care setting, that were either specifically designed to improve attendance for DRS or were evaluating general strategies to improve diabetes care. Most commonly, the latter group of studies referred to 'quality improvement targets' or 'diabetes processes of care measures' as primary or secondary outcomes. We only included these studies if they reported on the effect of the intervention on DRS attendance.

To investigate cost effectiveness we included full economic evaluations (cost‐effectiveness analyses, cost‐utility analyses and cost‐benefit analyses), cost analyses and comparative resource‐utilisation studies conducted alongside or as part of an included RCT.

Types of participants

We included people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus who were eligible for DRS.

Types of interventions

We included RCTs that used any planned strategy or combination of strategies to improve attendance for diabetic DRS targeted at individuals with diabetes (e.g. reminders, promotion of self‐management), healthcare professionals (e.g. education, audit and feedback) or the healthcare system (e.g. electronic registries, team changes). Interventions included those specifically targeting DRS, as well as those that were part of a general strategy to improve processes of diabetes care. Comparator interventions were as specified in the included studies.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was the difference in DRS attendance (one or more visits) within a two‐year period following implementation of the intervention. This could be based on self‐reports, medical insurance claims databases or health‐record audits (hospital, primary care physician or screening administration system record).

Secondary outcomes

We considered the following secondary outcomes:

Ongoing adherence to screening based on attendance for screening following the initial screening post‐intervention.

Economic outcomes:

Resources (staff time, equipment, consumables) required to deliver interventions to increase attendance for screening

Costs of staff used to provide interventions; costs of treatment and care; cost of primary care; lost wages and lost productivity (work output)

Cost effectiveness (incremental cost‐effectiveness ratios (ICERs); incremental cost per quality‐adjusted life year (QALY); incremental cost per disability‐adjusted life year (DALY); incremental cost‐benefit ratios; net benefits).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for RCTs and controlled clinical trials. There were no language or publication year restrictions. The date of the search was 13 February 2017.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 2) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) in the Cochrane Library (searched 13 February 2017) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 13 February 2017) (Appendix 2);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 13 February 2017) (Appendix 3);

PsycINFO (1967 to 13 February 2017) (Appendix 4);

Web of Science Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐Science (CPCI‐S) and Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) (1990 to 13 February 2017) (Appendix 5);

ProQuest Family Health (1990 to 13 February 2017) (Appendix 6);

OpenGrey (1980 to 13 February 2017) (Appendix 7);

ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch; searched 13 February 2017) (Appendix 8);

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 13 February 2017) (Appendix 9);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp; searched 13 February 2017) (Appendix 10).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of included studies to identify additional relevant studies. In particular, we used the reference list of included and excluded studies of a 2012 systematic review by members of the current review team (NI and JG) (Tricco 2012), which investigated the effectiveness of QI strategies on the management of diabetes. Tricco 2012 identified studies which have multiple interventions to improve the quality of care in diabetes. Some of the studies in this review included attendance for DRS as one of the outcomes being assessed. However, since the information on screening for diabetic retinopathy was not reported in the abstract or coded in the MeSH or thesaurus headings, the electronic search strategy used in the current review did not identify a number of these studies. In addition to searching the reference list of Tricco 2012, we also obtained additional studies reporting retinopathy outcomes from the review team currently updating that review. The protocol for the updated review has been republished (Ivers 2014), as whilst the scope of the review remains the same, the update proposes an exploration of heterogeneity using an innovative meta‐analytical approach.

We also contacted experts in the field to request information on any ongoing or unpublished studies that would be relevant for this review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (JGL and JB) independently screened the titles and abstracts of studies identified by the electronic searches. We obtained full‐text copies of possibly relevant studies, resolving any differences of opinion regarding inclusion/exclusion by discussion. We documented reasons for exclusion at this stage.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (JGL and EGR), working independently, extracted data from the included studies using a modified version of the Cochrane Effective and Organisation of Care (EPOC) data collection form (EPOC 2017), which incorporates information on study design, type and duration of interventions, participants, setting, methods, outcomes, and results. We translated studies in languages other than English and similarly extracted data in duplicate. Where numerical data were presented only in figures and not available from authors, two review authors performed data extraction by using Plot Digitizer open‐source software.

For the extraction of data on the sociodemographic characteristics of participants that are known to be important from an equity perspective, we used the Place, Race, Occupation, Gender, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, Social status (PROGRESS) framework (O'Neill 2014), and also recorded whether any interventions were aimed at disadvantaged or low‐ and middle‐income country populations, using the World Bank Atlas method.

An economics review author (PA) identified and further assessed studies judged potentially to include economic data. Data from included economic evaluations were extracted by one review author (PA) and checked by a second. We adapted data collection from the format and guidelines used to produce the structured abstracts of full economic evaluations for inclusion in the NHS Economic Evaluation Database, and redesigned them to accommodate the specific data required for our review (CDC 2012). We classified economic evaluations based on their analytical framework and coded them appropriately.

Coding of intervention content

We coded extracted intervention descriptions from all of the included studies using a validated taxonomy to characterise the constituent components of each intervention. Cochrane EPOC has developed a comprehensive taxonomy to classify intervention content in systematic reviews (EPOC 2015). We used a subset of the EPOC taxonomy that has been previously used by members of the review team in a review of the effectiveness of general QI implementation strategies for diabetes care (Tricco 2012). This adapted taxonomy incorporates 12 components targeting healthcare systems (case‐management, team changes, electronic patient registry, facilitated relay of information to clinicians, continuous quality improvement), clinicians (audit and feedback, clinician education, clinician reminders, financial incentives) or patients (patient education, promotion of self‐management and reminder systems). Two review authors (JGL and EGR) independently coded QI components as 'present' or 'absent' for both intervention and control arms, resolving discrepancies in coding by discussion.

To better characterise the detail of the intervention content, we also coded extracted intervention descriptions into component BCTs using the BCT taxonomy (Michie 2013), as a coding framework. Describing an intervention in terms of BCTs (i.e. 'active ingredients') provides a useful level of detail for synthesis and comparison (Presseau 2015). We coded BCTs for each intended recipient as 'present' or 'absent' separately for patient and healthcare professional recipients. We coded each intervention separately, including control arms. We coded system‐level interventions as targeting either healthcare provider or patient behaviour, or both, unless an alternative intervention recipient and their behaviour was reported (e.g. administrative staff sending reminder letters) (see Table 4).There is substantial evidence that the content of complex behaviour change interventions is often poorly described in published reports, rendering it more difficult to clearly specify the content of interventions on this basis alone and increasing the risk of misclassification (Lorencatto 2013). We therefore contacted all authors of included studies to ask for further information on the content of the intervention (e.g. a trial protocol, letters sent to patients, written or audio‐visual materials) to clarify the BCT coding. We coded these materials using the BCT taxonomy in the same manner as for the corresponding published reports.Two review authors (EGR and FL) independently conducted BCT coding, resolving discrepancies by discussion and if necessary by the involvement of a third review author (JF).

1. Illustrative quotations for BCTs used in the included studies.

| Behaviour change technique (BCT) and abbreviated definitions | Illustrative quotation |

| Goals and planning | |

|

Goal setting (behaviour) Set or agree a goal defined in terms of the behaviour to be achieved e.g. Set targets for how often patients should attend DRS, or general diabetes self‐management, such as frequency of blood glucose testing, amount of carbohydrates to consume at each meal |

"Practice nurses planned independent consultations with patients. The monitoring tool guided them through the consultations, and provided the opportunity to help the patient in selecting appropriate, concrete, behavioural goals …. The monitoring tool addressed clinical parameters (e.g., HbA1C, BP and LDL cholesterol levels), examinations (e.g. food control, neurological tests, and eye examinations), adherence to prescribed drugs, self‐care goals, and other recommendations" (Frei 2014 p 1040‐1) |

|

Problem solving Analyse, or prompt the person to analyse, factors influencing the behaviour and generate or select strategies that include overcoming barriers and/or increasing facilitators e.g. Support patients to identify reasons for wanting or not wanting to attend DRS, and helping them select potential strategies for overcoming these barriers to screening attendance |

"Using a semi structured protocol, the health educator (C.J. H.) offered one‐on‐one, interactive education and counselling. Having established rapport, she worked to identify and understand each subject’s reasons for and /or barriers to having a dilated retinal examination. Focused problem‐solving then guided the subject toward making an informed choice about receiving an ophthalmic examination." (Basch 1999, p 1879) |

|

Goal setting (outcome) Set or agree a goal defined in terms of a positive outcome of wanted behaviour e.g. Agree with the patient target HbA1c, blood pressure, or cholesterol level, or target range for blood glucose |

"During the case management sessions, patients and providers set management goals that were reasonable to achieve." (Barcelo 2010, p 147) |

|

Action planning Prompt detailed planning of performance of the behaviour e.g. Support the patient to develop a plan for how often they will attend DRS, where the DRS will occur, and how they will get to their appointment |

"Behavioural activation for diabetic retinopathy prevention combined the principles of education about diabetes mellitus, behavioural therapy, and the health belief model to assist participants in identifying barriers to obtaining dilated fundus examinations, problems‐solving solutions to surmounting barriers, formulating action plans to facilitate dilated retinal examinations, and gauging the success of action plans." (Weiss 2015, p 1007) |

|

Review behaviour goals Review behaviour goal(s) jointly with the person and consider modifying goal(s) or behaviour change strategy in light of achievement e.g. During scheduled diabetic review consultations, discuss with patients how they are progressing with their agreed self‐management behavioural goals (e.g. frequency of blood glucose testing, attendance for DRS). Where patients are not meeting agreed goals, either discuss how to adjust goals if needed to increase feasibility, or engage in problem‐solving to overcome any barriers to goal attainment |

"Care managers were trained to use a patient‐centred self‐management approach that included review of the medical care needs and self‐care goals that the patient identified and brainstorming additional strategies that patients could use to overcome barriers to their goals." (Glasgow 2005, p 35) |

|

Discrepancy between current and goal Draw attention to discrepancies between a person’s current behaviour and the person’s previously set outcome goals, behaviour goals or action plans e.g. Provide feedback to healthcare professionals on the proportion of patients who have received DRS in the previous 12 months, and compare this against a gold standard for clinical practice based on clinical guidelines |

"Physicians in the IG [intervention group] received a monthly report of their care quality with the top 10% quality of diabetes care score for all physicians being the achievable benchmark."(Hayashino 2016, p 1) |

|

Review outcome goal(s) Review outcome goal(s) jointly with the person and consider modifying goal(s) in light of achievement e.g. Review or alter target blood glucose levels towards a more feasible/achievable intermediate target |

"The telephone call was structured to first review the patient’s goals, followed by medication use, symptoms, glucose monitoring, blood pressure monitoring and self‐management /care activities" (Taylor 2003, p 1059) |

|

Behavioural contract Create a written specification of the behaviour to be performed, agreed by the person, and witnesses by another e.g. Ask the person with diabetes to sign a contract in their self‐management plan or diary, undertaking to attend DRS once |

Care guides asked patients to sign a contract (which was scanned into the HHR) agreeing to work toward their disease‐specific goals. (Adair 2013, p 176) |

|

Commitment Ask the person to affirm or reaffirm statement indicating commitment to change the behaviour e.g. Ask the person with diabetes to verbally affirm or reaffirm that they are committed to attending DRS at the agreed frequency and location |

"The initial goal was toelicit a verbal commitment to schedule an eye examination." (Basch 1999, p 1879) |

| Feedback and monitoring | |

|

Monitoring of behaviour by others without feedback Observe or record behaviour with the person’s knowledge as part of a behaviour change strategy e.g. Record the proportion of patients who attend for a DRS exam as part of clinical audit, but the results are not fed back to the healthcare professionals whose practice has been audited |

"Foot examinations, blood pressure, and eye examinations were recorded on the reminder by clinic staff, collected after the patient visit and entered manually." (Peterson 2008, p 2239) |

|

Feedback on behaviour Monitor and provide information or evaluative feedback on performance of the behaviour (e.g. form, frequency, duration, intensity) e.g. Provide a feedback report to healthcare professionals, stating the proportion of their patients who have attended a DRS exam, had their blood pressure taken, and had a foot examination |

"In addition, diabetic members who did not have a record of a diabetic retinopathy exam received educational materials and a report of their current DRE status directly from the HMO 2 weeks later." (Halbert 1999, p 753) |

|

Self‐monitoring of behaviour Establish a method for the person to monitor and record their behaviour(s) as part of a behaviour change strategy e.g. A person with diabetes maintains a self‐management diary in which they record their daily food intake and exercise, and tick off a checklist when they have attended their annual DRS exam |

"We prepared feedback sheets for adherence to these eight indicators using data from thephysicians’ self‐report forms, as the physicians monitored and promoted these indicators to improve adherence." (Hayashino 2015, p 601) |

|

Self‐monitoring of outcomes of behaviour Establish a method for the person to monitor and record the outcome(s) of their behaviour as part of a behaviour change strategy e.g. A person with diabetes records in their self‐management diary the results of their latest HbA1C result and DRS exam |

"In general, case managers were directed to encourage patient self‐management, including diet and exercise, provide reminders for recommended screening/tests,help with appointment scheduling;monitoring home glucose and blood pressure levels…" (Krein 2004, p 734) |

|

Monitoring of outcomes of behaviour by others without feedback Observe or record outcomes of behaviour with the person’s knowledge as part of a behaviour change strategy e.g. A person attends a DRS exam, but is not provided with the results of the examination |

"The nurse case manager used behavioural goals setting, established individualized care plan, provide patient self‐management education and surveillance of patients…ordered protocol‐driven laboratory tests, tracked the outcomes using the computerized data registry…" (Gabbay 2006, p 30) |

|

Feedback on outcomes of behaviour Monitor and provide feedback on the outcome of performance of the behaviour e.g. Informing the person with diabetes of the results of DRS exam [i.e. presence/absence of retinopathy] |

"…all persons who attended the screening clinics received a dilated eye exam by a volunteer community‐based ophthalmologist. The eye exam included visual acuity, intraocular pressure, and a fundus examination through a dilated pupil…immediately after receiving the dilated eye exam, the patient was told the results by the examination ophthalmologist." (Anderson 2003, p 41) |

|

Biofeedback Provide feedback about the body (e.g. physiological or biochemical state) using an external monitoring device as part of a behaviour change strategy |

"… immediately after receiving the dilated eye exam, the patient was told the results by the examination ophthalmologist." (Anderson 2003, p 41) |

| Social Support | |

|

Social Support (unspecified) Advise on, arrange or provide social support (e.g. from friends, relatives, colleagues, ‘buddies’ or staff) or non‐contingent praise or reward for performance of the behaviour. In includes encouragement and counselling e.g. Provide general encouragement or reassurance to a person with diabetes to attend their DRS appointment |

"Overall, the intervention included …and self‐management support (provided by the practice nurse)." (Frei 2014, p 1041) |

|

Social Support (practical) Advise on, arrange, or provide practical help (e.g. from friends, relatives, colleagues, ‘buddies’ or staff) for performance of the behaviour e.g. Provide practical help for a patient with diabetes to attend DRS. This can include, for example: arranging a referral to DRS, arranging or providing transport to the clinic |

"Referrals were facilitated to other clinicians when indicated, including ophthalmology, podiatry, nutrition and primary care for follow‐up of acute or other chronic issues or when requested by patients." (Jacobs 2012, p 616) |

| Shaping knowledge | |

|

Instruction on how to perform behaviour Advise or agree on how to perform the behaviour (includes ‘skills training’) e.g. Provide advice to a person with diabetes on how often guidelines recommend attending DRS, where they can obtain a DRS, and how to schedule an eye exam |

"A direct mail reminder was sent to patients to reinforce the importance of annual eye exams and included the following text: If you don’t have an eye doctor, ask you regular doctor to refer you to one." (Prela 2000, p 258) |

| Natural consequences | |

|

Information about health consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about health consequences of performing the behaviour e.g. Provide advice to the person with diabetes, on the negative health consequences of retinopathy, and the benefits of early detection |

"A tailored telephone intervention was delivered by bilingual interventionists and included: Risk communications, such as the frequency lack of symptoms of retinopathy and that early treatment for retinopathy decreases the risk of blindness, were included." (Walker 2008, p 187) |

|

Salience of consequences Use methods specifically designed to emphasise the consequences of performing the behaviour with the aim of making them more memorable e.g. Give a person with diabetes a leaflet containing testimonials from other persons with diabetes who suffer from retinopathy to emphasise the benefits of attending DRS and early detection |

"The videotape used emotional appeals through storytelling to increase motivation to have a yearly dilated retinal examination." (Basch 1999, p 1879) |

|

Information about social & environmental consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about social and environmental consequences of performing the behaviour e.g. Provide information on the costs of having a DRS exam |

"A take‐home reminder (aimed at patients, to remind them to make an appointment for an eye exam), to be given to patients by their Family Practitioner, included the following text: OKIP covers annual eye checks for patients with diabetes so you will not have to pay" (Zwarenstein 2014, p 90) |

|

Information about emotional consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about emotional consequences of performing the behaviour e.g. Provide a leaflet recognising the potential negative effects on emotional and mental health of managing a chronic illness, such as diabetes |

"Group visit content, though patient‐guided, was physician‐directed to cover educational topics…and the emotional aspects of diabetes." (Clancy 2007, p 621) |

| Comparison of behaviour | |

|

Demonstration of the behaviour Provide an observable sample of the performance of the behaviour, directly in person or indirectly (e.g. by film, picture, for the person to aspire to or imitate) e.g. Play a video demonstrating the DRS procedure |

"The newsletter consisted of six sections, including a testimonial designed to model eye examination behaviour" (Ellish 2011, p 1593) |

|

Social comparison Draw attention to others’ performance to allow comparison with the person’s own performance e.g. Provide healthcare professionals with feedback on the proportion of their patients who have had a DRS exam, and benchmark this in comparison to other hospitals or healthcare professionals |

"The system presented register data on their’ Type 2 diabetes population, giving them the option either to use the data during individual diabetes consultations or to gain an overview of the quality of their diabetes care and compare it with the corresponding quality in their colleagues’ practices." (Guldberg 2011, p 326) |

|

Information about others’ approval Provide information about what other people think about their behaviour. The information clarifies whether others will like, approve or disapprove of what the person is doing or will do e.g. Tell the person with diabetes that their family members would likely be keen for them to attend their DRS appointment |

"One of the message in the targeted newsletter read: Even though you’ve been thinking about getting a dilated eye exam, we hope you’ll make the call now"(Ellish 2011, Additional information provided by the author) |

| Associations | |

|

Prompts/Cues Introduce or define environmental or social stimulus with the purpose of prompting or cueing the behaviour e.g. Phone the person with diabetes to remind them of their upcoming DRS appointment |

"For those who made an appointment, a reminder letter was mailed 3 weeks prior to the scheduled appointment. Additionally, there was an automated reminder call the day before the scheduled appointment" (Pizzi 2015, p 255) |

|

Reduce prompts/cues Withdraw gradually prompts to perform the behaviour e.g. Decrease the frequency with which a person with diabetes is sent a reminder of their DRS attendance (i.e. from weekly, to fornightly, to monthly, to quarterly reminders) |

"Recommendations for regular telephone follow‐ups for diabetes patients, which will be monthly in the 1st half year and then will probably decrease" (Jansink 2013 (coded from protocol 2009) |

| Repetition and substitution | |

|

Behavioural practice/rehearsal Prompt practice or rehearsal of the performance of the behaviour one or more times in a context or at a time when the performance may not be necessary, in order to increase habit and skill e.g. Provide an opportunity for trainee healthcare professionals to practise delivering a DRS exam to an actor role‐playing a patient with diabetes |

"During a 2‐day training session, case managers received instruction on collaborative goal setting, with case examples and role‐playing used to familiarize them with the treatment algorithms"(Krein 2004, p 734) |

|

Graded tasks Set easy‐to‐perform tasks, making them increasingly difficult, but achievable, until the behaviour is performed e.g. Initially allocate a healthcare professional responsibility for one component of DRS exam and progressively increase their responsibility |

"Theoretically, this form of facilitation should be necessary for only a relatively short period of time, with the practice improvement team progressively assuming responsibility for the ongoing improvement efforts after the initial facilitation." (Dickinson 2014, p 10) |

| Comparison of outcomes | |

|

Credible source Present verbal or visual communication from a credible source in favour of or against the behaviour e.g. Include the logos for national health institutes, or cite published clinical guidelines, to endorse information provided in leaflets regarding DRS |

"Participants in the print‐intervention group received a mailing of a colourful, 14‐page booklet on preventing diabetes eye problems called Keep Your Eyes Healthy, in English or Spanish,developed b y the National Institutes of Health." (Walker 2008, p 187) |

| Reward and threat | |

|

Material incentive (behaviour) Inform that money, vouchers or other valued objects will be delivered if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in performing the behaviour e.g. Advise the person with diabetes that they will receive a shopping voucher if they attend their upcoming DRS appointment |

"The automated system offered a live telephone call back to assist in scheduling test and alsooffered to send participants the following items: 1) a voucher that would allow the provider to waive the co‐payment for a dilated eye examination…" (Simon 2010, p 1452) |

|

Social reward Arrange verbal or non‐verbal reward if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in performing the behaviour e.g. Verbally praise the person with diabetes if they attend their DRS appointment |

"When a subject reported having a dilated retinal examination a congratulatory letter was sent." (Basch 1999, p 1879) |

|

Non‐specific reward Inform that a reward will be delivered if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in performing the behaviour e.g. Inform the healthcare professional that they will be rewarded for conducting a DRS exam with a target proportion of their patients |

"CME credits were given to the participating physicians in the workshops" (Vidal‐Pardo 2013, p 752) |

| Antecedents | |

|

Restructuring the physical environment Change or advise to change the physical environment in order to facilitate performance of the wanted behaviour or create barriers to the unwanted behaviour e.g. Introduce mobile DRS vans in geographically remote areas to increase access to screening facilities |

"Care guide workstations were located in the clinic waiting rooms, to facilitate face‐to‐face interactions with patients, providers, and nurses." (Adair 2013, p 177) |

|

Restructuring the social environment Change or advise to change the social environment in order to facilitate performance of the wanted behaviour or create barriers to the unwanted behaviour e.g. Change a healthcare team and team working, such as introducing a new specialist diabetes nurse role responsible for monitoring screening rates and phoning people with diabetes to remind them to attend their DRS appointment |

"Three multi‐lingual Link Workers already employed by Coventry Primary Care Trust (PCT) were trained in diabetes management and care and assigned to work with specific intervention GP surgeries" (Bush 2014, p 295) |

|

Adding objects to the environment Add objects to the environment in order to facilitate performance of the behaviour e.g. Introduce new computerised software to a general practice to help monitor and remind healthcare professionals as to which patients need to be prompted to attend DRS |

"In addition 4500 diabetes passports were made available at the four hospitals…" (Dijkstra 2005, p 128) |

| Scheduled consequences | |

|

Behaviour cost Arrange for withdrawal of something valued if and only if an unwanted behaviour is performed e.g. Charging people with diabetes a fee for failing to attend a DRS exam |

"We were interested to find out whether a small copayment would be an important deterrent to the uptake of screening for diabetic retinopathy (DR)…We conducted a randomized trial in which one group was charged a small fee for DR screening and the other was provided with free access." (Lian 2013, p 1247) |

| Self‐belief | |

|

Verbal persuasion about capability Tell the person that they can successfully perform the wanted behaviour, arguing against self‐doubts and asserting that they can and will succeed e.g. Encourage or reassure the patient to attend a DRS exam, providing information as needed to address any concerns or self‐doubts they may have about attending for a DRS exam |

"Diabetes is a serious, lifelong condition, but there is so much that you can do to protect your health. Take charge of your health, not only for today, but also for the years to come" (Lafata 2002, p 523) |

|

Focus on past success Advise to think about or list previous successes in performing the behaviour (or parts of it) e.g. Help the person with diabetes to remember the last time they attended a DRS exam, and use this as an opportunity to reassure them of the benefits of attending |

A comprehensive programme that integrated lifestyle: counselling based on motivational interviewing principles was integrated into structured diabetes care. [In description of motivational interviewing] "Self‐efficacy can be strengthened by affirming past success (i.e. reinforcement)…" (Jansink 2013 , additional information from protocol) |

DRS: diabetic retinopathy screening

Coding of resource requirement needed to deliver interventions

We developed an ordered ranking scale to quantify the level of resource needed to deliver each intervention, based on the description of the intervention components in each included study. To determine the feasibility of this approach, we initially piloted the scale on a sample of 10 included studies, using two members of the review team. We graded each intervention initially between one (least resource‐intensive) and five (most resource‐intensive), or zero (unable to determine), together with a record as to how the review author graded each study.

We incorporated the following resource components into the algorithm:

• Face‐to‐face minutes • Phone calls • Patient home visits • Printed materials/software • Training

The resource categories and levels with their corresponding weights were as follows:

| Face‐to‐face or care planning minutes/patient/6 months | Phone calls to patients | Additional outreach visits to patients (travel time) | Use of materials/ letters/software | Training of health professionals other than reading material |

| None (0) | No (0) | No (0) | None (0) | None (0) |

| Low 1 ‐ 40 mins (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (2) | Printed materials (1) | Low (1) |

| Moderate 40 ‐ 100 (2) | ‐ | ‐ | Software (2) | High (2) |

| High > 100 (3) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

We defined a priori a criterion of success of the ranking scale as review author scores from nine out of 10 studies being within one grade of each other, following discussion. This criterion was achieved and we used the notes about how we graded each study to generate a reproducible description of the resource input associated with each grade on the ranking scale. We then used the resource components and their intensity levels to extract resource use required to deliver the interventions in all included studies. Two review authors (JGL and EGR) did this independently.

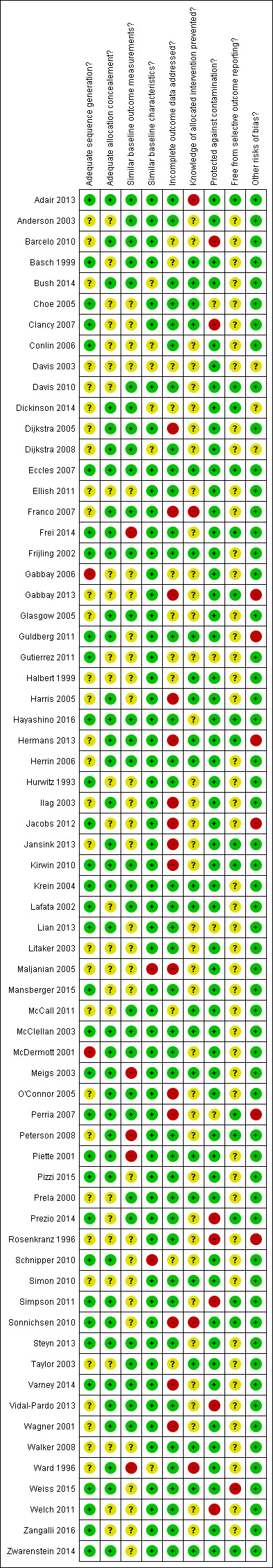

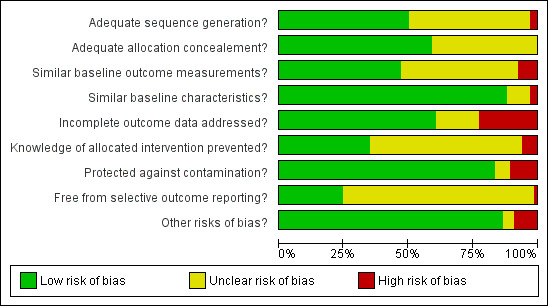

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (JGL and EGR) independently assessed study quality using the Cochrane EPOC 'Risk of bias' tool (EPOC 2012). We based the choice of the EPOC 'Risk of bias' tool on the expectation that the included studies would be similar to those included in EPOC reviews, e.g. a large number of cluster trials, complex interventions and routine data used to assess outcomes.

The EPOC criteria for assessing risk of bias uses nine standard criteria:

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Were baseline outcome measurements similar?

Were baseline characteristics similar?

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Was the study adequately protected against contamination?

Was the study free from selective outcome reporting?

Was the study free from other risks of bias?

For cluster‐RCTs, we considered particular biases, including: (i) recruitment bias; (ii) baseline imbalance; (iii) loss of clusters, and (iv) incorrect analysis; as described in Chapter 16 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). For each domain, two review authors performed the 'Risk of bias' assessment independently and assigned a judgement of ’low risk’ ’high risk’ or ’unclear risk’ of bias. The review authors resolved any discrepancies between them by discussion.

The reliability of data outputs from any full economic evaluation are in part predicated on the reliability of the data for the estimates of the relative treatment effects (for benefits or harms) of the alternative courses of action (i.e. intervention(s) and comparator(s)) under investigation). As the identified economic studies were a subset of the studies included in the review, the risk of bias was already assessed. However, assessment of the overall methodological quality of the economic component was still required and was carried out by one review author (PA) using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standard (CHEERS) statement, together with the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) (Evers 2005; Husereau 2013). In assessing the methodological quality of economic evaluations, the main objective is to assess the applicability of the scope of the analysis in terms of costs and outcomes. This helps to highlight the applicability and relevance of each economic evaluation.

Measures of treatment effect

Attendance at screening post‐intervention is a dichotomous outcome and we have reported the intervention effect as the risk difference (RD), i.e. the actual difference in the observed events between experimental and control interventions. Our choice of RD was based on the fact that relative effect sizes (e.g. risk ratios) are highly dependent on the baseline/control compliance, i.e. a similar risk ratio if screening attendance increase from 10% to 20% or from 50% to 100%. During the development of the protocol for the review, we received advice from the Cochrane EPOC group who have found that RDs are much more interpretable, and it is also possible to explore whether baseline compliance is an effect modifier.

Unit of analysis issues

For individual randomised trials the unit of analysis was the individual participant. For cluster‐RCTs, we analysed data after adjustment for clustering. In case of cluster‐RCTs, where outcomes were presented at patient level, we used an established method to adjust for clustering (Higgins 2011).This involved dividing the original sample size by the design effect, which was calculated from the average cluster size and the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC). Where the ICC was not reported, we imputed the most commonly‐reported value from studies where it was reported.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors of included studies if important data were not available. Where we were not able to obtain these data, we reported the available results and did not impute missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity between studies by visual inspection of forest plots and by formal statistical tests of heterogeneity (Chi2 test and the I2 statistic), and explored the possible reasons for heterogeneity using subgroup and random‐effects meta‐regression analyses.

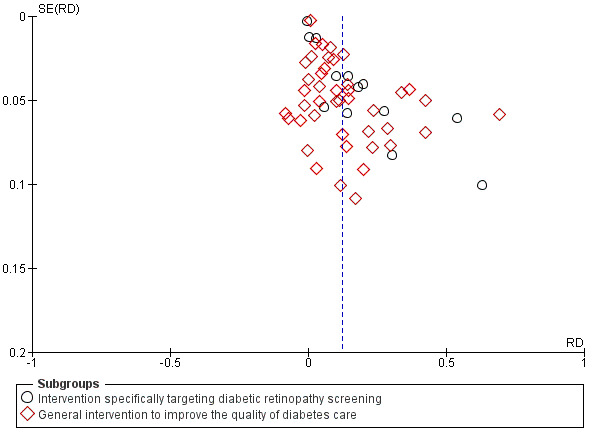

Assessment of reporting biases

We explored publication bias using a funnel plot for the main comparison of any intervention versus usual care.

Data synthesis

We conducted meta‐analyses in Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014), using a random‐effects model to estimate the pooled RD across studies. We included data from RCTs randomised by individual and from cluster‐adjusted RCTs in the same meta‐analysis. In the case of multiple intervention groups, we combined groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

A summary of the results of included economic evaluations is available as an additional table (Table 5) and is supplemented by a narrative description in the Results and Discussion sections. Costs for each study were adjusted to 2016 British pound value (GBP) using a web‐based conversion tool based on implicit price deflators for gross domestic product (GDP, a measure of the wealth of a country) and GDP Purchasing Power Parities. Table 5 presents the original currency and price year used in each included study. Users of this review who might want to adjust costs to another currency and price year suitable for their needs should use costs for each study presented in Table 5 and not the adjusted costs presented in the main text of the review.

2. Summary of reported costs and resources to deliver interventions.

| QI Component | Study | DRS or GQI | Estimated costs of resources used | Resources used |

| Promotion of self‐management |

Davis 2010 N = 85 participants |

GQI | Staff cost per person = GBP 625.25; costs of the other resources used = GBP 476.35 over 12 months Direct cost per person = GBP 1101 |

13 x 15‐minute sessions (3 individuals and 10 group session) with nurses and 4 hours with health educator per person |

|

Wagner 2001 N = 14 clinics, 278 participants |

GQI | Not reported | 1‐hour group session with relevant health professional every 3 ‐ 6 months | |

| Team changes |

Frei 2014 N = 15 practices, 164 participants |

GQI | Not reported | 6‐day training for nurses, 2 x 4‐hour workshops for physicians and nurses |

|

Wagner 2001 N = 14 clinics, 278 participants |

GQI | Not reported | 1‐hour group session with relevant health professional every 3 ‐ 6 months | |

|

Litaker 2003 N = 79 participants |

GQI | Mean personnel costs for the intervention per month per patient = GBP 130.15 Total additional personnel costs = GBP 10281.97 |

An average of 180 minutes with participants | |

| Case management |

Krein 2004 N = 123 participants |

GQI | Not reported | 2 days training for case managers, 20 hours/week time spent with participants. Quarterly profiling and subsequently every 6 months |

| Patient education |

Prezio 2014 N = 90 participants |

GQI | Physician cost = GBP 48.76/hour Community health worker = GBP 12.91/hour Cost of intervention over 20 years = GBP 3646.10 per patient |

7 sessions per participants, 1 hour physician supervision for health workers |

|

Pizzi 2015 N = 117 participants for mailed intervention, 120 for telephone intervention |

DRS | Staff time for 120 participants = GBP 501.13 for telephone over 1 month Staff time for 117 participants = GBP 173.17 for mailed intervention over 1 month GBP 85.24/hour for the physician, GBP 29.32/hr for health services manager, GBP 16.72/hour for medical assistant Cost of materials for telephone = GBP 30.25, cost of materials for mailed intervention Total cost of intervention = GBP 577.64 for 120 participants in telephone group, GBP 335.48 for 117 participants in mailed group over a month Total cost when appointment is made and kept per participant; Telephone intervention = GBP 9.47 Mailed intervention = GBP 8.83 |

1‐hour supervision for every 20‐hour intervention delivered 2 x 1‐hour meetings with medical assistants, health services manage and ophthalmologist |

|

|

Adair 2013 N = 930 participants |

GQI | Care guide cost for 120 participants = GBP 375,917 at the rate of GBP 11.77/hour over a year 2 supervisory nurses = GBP 85,847.24 Training cost = GBP 2228.99 modular furniture and equipment for 12 stations = GBP 79,422.81 Total cost = GBP 463,993 Total cost of intervention per participant = GBP 326 |

12 care guides, 2 weeks training, 2 supervisory nurses, 5 visits on average to clinics, 4 contacts with participants, furniture and modular equipment | |

|

McCall 2011 N = approximately 20,000 participants |

GQI | Not reported | Not reported | |

|

Clancy 2007 N = 96 participants |

GQI | Deposit fee for group visit = GBP 13.4/visit, for 12 visits = GBP 160.60 | Monthly meeting for a year for 2 hours which includes 1 primary care internal medicine physician, 1 registered nurse per visit Training for physicians and nurses 3‐ hour training for clinic staff 12 group visits for 1 year |

|

| Schechter 2008 (Walker 2008) N = 305 participants for telephone intervention, 298 for print intervention |

DRS | Costs of health educator = GBP 14,890.83 Training and supervision = GBP 2756.44 Telephone charges = GBP 679.67 for 305 participants Costs of printing and mailing = GBP 465.99 for 298 participants |

Average of 3.2 calls for about 20 minutes +5 minutes call preparation per participant over 6 months 20 hours training, 1 hour supervision by diabetes nurse educator, telephone calls |

|

| Electronic patient register |

Eccles 2007 N = 30 practices, 1674 participants |

GQI | Cost of developing the guidelines = GBP 10,208 Cost of software development = GBP 12519.36 Cost of educational activities = GBP 2148.11 Additional cost of running the system = GBP 9964.46 Annual cost per participant = GBP 68.21 |

Cost of guidelines and software development. Average of 2 follow‐up contacts |

| Patient reminders | Schechter 2008 (Walker 2008) N = 305 participants for telephone intervention, 298 for print intervention |

DRS | Costs of health educator = GBP 14,890.83 Training and supervision = GBP 2756.44 Telephone charges = GBP 679.67 for 305 participants Costs of printing and mailing = GBP 465.99 for 298 participants |

Average of 3.2 calls for about 20 minutes + 5 minutes call preparation per participant over 6 months 20 hours training, 1 hour supervision by diabetes nurse educator, telephone calls |

|

Pizzi 2015 N = 117 participants for mailed intervention, 120 for telephone intervention |

DRS | Staff time for 120 participants = GBP 501.13 for telephone over 1 month Staff time for 117 participants = GBP 173.17 for mailed intervention over 1 month GBP 85.24/hour for the physician, GBP 29.32/hour for health services manager, GBP 16.72/hour for medical assistant Cost of materials for telephone = GBP 30.25, cost of materials for mailed intervention Total cost of intervention = GBP 577.64 for 120 participants in telephone group, GBP 335.48 for 117 participants in mailed group over a month |

1 hour supervision for every 20‐hour intervention delivered 2 x 1‐hour meetings with medical assistants, health services manager and ophthalmologist |

|

| Audit and feedback |

Frijling 2002 N = 62 clusters, 703 participants |

GQI | Cost of clinical decision‐making per practice = GBP 341.51 | 80 hours training for facilitator, 15 x 1‐hour visits to practice clinic, 3 hours GP time for implementation of feedback |

| Clinician reminders |

Litaker 2003 N = 79 participants |

GQI | Mean personnel costs for the intervention per month = GBP 130.15 Total additional personnel costs = GBP 10,281.97 |

An average of 180 minutes with participants over 12 months |

| Continuous quality improvements |

Piette 2001 N = 146 participants |

GQI | Approximately GBP 14 ‐ GBP 24 per year for automated calls. | 13 nurses spending an average of 3.8 hours per participant, 15 automated calls |

DRS: diabetic retinopathy screening GQI: general quality improvement

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform the following prespecified subgroup analyses to investigate whether the presence or absence of a particular covariant explained the variability in effect size:

QI intervention components/BCTs

Resource requirements to deliver the intervention

Population subgroups: type 1, type 2 diabetes mellitus, participant characteristics across PROGRESS categories

In our analyses, we assessed QI components (coded using the modified EPOC taxonomy) and BCTs of each intervention separately. Where a study used multiple QI components or BCTs or both, we applied the same effect size to each component for the analysis. We compared effect estimates for subsets of studies that used a particular QI component/BCT or resource intensity and calculated a pooled effect size. We included BCTs/QI components in the analysis when 10 more studies were available for each BCT/QI component.

We further investigated associations between DRS attendance and effect size by meta‐regression for a number of covariates, including: type of study design (individual/cluster‐RCT), baseline DRS attendance and QI component/BCT used in the intervention. For meta‐regression we used a prespecified random‐effects model and compared the risk difference of studies containing a particular explanatory variable to studies in which the variable was absent. For metaregression we followed the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), and only included covariates for which 10 or more studies were available.

We conducted subgroup analyses and meta‐regression using Stata 14, deploying the metan and metareg commands.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis to determine the impact on the pooled effect estimate of imputing the lower and upper range values for the ICC.

'Summary of findings' Tables

We prepared 'Summary of findings' tables for the main comparisons (1. effect of any QI intervention versus usual care on DRS attendance and 2. effect of a more intensive (stepped) invertion versus a less intensive intervention). We assessed certainty of evidence (GRADE) for each outcome using customised software (GRADEpro GTD). One author (JGL) did the initial assessment which was then checked by other review authors. We considered risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias when judging the certainty of the evidence.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

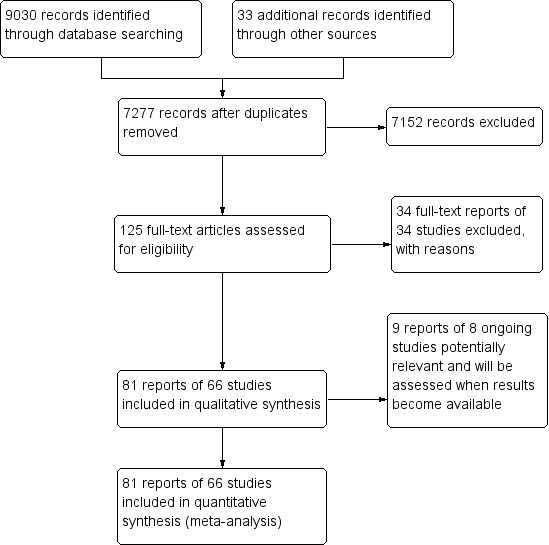

The electronic searches yielded 9030 records (Figure 1). The Cochrane Information Specialist removed 1786 duplicate records and we screened the remaining 7244 records plus 33 records identified from additional sources (Tricco 2012). We rejected 7152 records after reading the abstracts and obtained full‐text reports of 125 references for further assessment. We identified 81 reports of 66 studies that met the inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of included studies) and excluded 34 reports of 34 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies). We also identified nine reports of eight ongoing trials (see Characteristics of ongoing studies), and will assess these when results become available.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The included studies were conducted between 1988 and 2013. Thirty‐five studies (53%) were parallel‐group patient RCTs enrolling 237,025 patients, and 31 (47%) were cluster‐RCTs in which the healthcare professional or the healthcare setting was the unit of randomisation. These included 6126 clusters (range 6 to 4125). Fifty‐nine studies (89.4%) had two arms, six studies (9.1%) had three arms and one study (1.5%) had more than three arms. For further details see Characteristics of included studies.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics are reported in Table 6. Most of the studies (57.6%) recruited participants with type 2 diabetes, 15.2% of studies included those with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes, and in 12.1% of studies the type of diabetes was not reported.

3. Summary of characteristics of included studies.

| Study characteristics |

Target: diabetic retinopathy screening attendance N = 16 |

Target: general quality improvement in diabetes care N = 50 |

TOTAL N = 66 |

| Study design | Individual RCT: n = 14 (87.5%) Cluster‐RCT: n = 2 (12.5%) 2 arms n = 13 (81.3%) 3 arms n = 2 (12.5%) > 3 arms n = 1 (6.3%) |

Individual RCT: n = 21 (42%) Cluster‐RCT: n = 29 (58%) 2 arms n = 46 (92%) 3 arms n = 4 (8%) |

Individual RCT n = 35 (53%) Cluster‐RCT n = 31 (47%) 2 arms n = 59 (89.4%) 3 arms n = 6 (9.1%) > 3 arms n = 1 (1.5%) |

| Location | USA: n = 12 (75%) Canada: n = 1 (6.3%) China: n = 1 (6.3%) Germany: n = 1 (6.3%) UK: n = 1 (6.3%) Conducted between 1995 and 2013 |

USA: n = 29 (58%) Canada: n = 2 (4%) Netherlands: n = 4 (8%) Australia: n = 3 (6%) UK: n = 2 (4%) Other n = 10 (20%) Conducted between 1988 and 2013 |

USA: n = 41 (62.1%) Canada: n = 3 (4.6%) Netherlands: n = 4 (6.1%) Australia: n = 3 (4.6%) UK: n = 3 (4.6%) Other: n = 12 (18.2%) Conducted between 1988 and 2013 |

| Setting | Primary care: n = 11 (68.8%) Outpatient clinics: n = 4 (25%) Unclear: n = 1 (6.3%) |

Primary care: n = 40 (80%) Outpatient n = 3 (6%) Unclear: n = 7 (14%) |

Primary care: n = 51 (77.3%) Outpatient clinics n = 7 (10.6%) Unclear n = 8 (12.1%) |

| Diabetes type | Type 2: n = 4 (25%) Type 1 and Type 2: n = 3 (18.8%) Not reported: n = 9 (56.3%) |

Type 2: n = 34 (68%) Type 1 and Type 2 n = 7 (14%) Not reported: n = 9 (18%) |

Type 2 : n = 38 (57.6%) Type 1 and 2 n = 10 (15.2%) Not reported n = 18 (27.3%) |

| Number of participants recruited | Individual RCT = 38,273 Cluster RCT = 4135 clusters, 182,513 participants Total: 220,786 participants included |

Individual RCT = 198,752 Cluster RCT = 1991 clusters, 78,276 participants Total: 277,028 participants included |

Individual RCT = 237,025 Cluster RCT = 6126 clusters, 260,789 participants Total: 497,814 participants included |

| Median age | Median 60.7 yrs (range 51.1 ‐ 72.7) Number reporting n = 9 | Median 60.6 yrs (range 46.8 ‐ 74) Number reporting n = 34 |

Median 60.7 yrs (46.8 ‐ 74) Number reporting n = 43 |

| Gender (% male) | Median 38.9% (range 25% ‐ 98%) Number reporting n = 12 |

Median 49.8% (range 25% ‐ 97%): Number reporting n = 35 |

Median 48% (25% ‐ 98%) Number reporting n = 47 |

| Type of screening | Retinal exam n = 12 (75%) Grading of digital retinal images: n = 4 (25%) |

Retinal exam n = 49 (98%) Grading of retinal images n = 1 (2%) |

Retinal exam n = 61 (92.4%) Grading of retinal images n = 5 (7.6%) |

| Baseline screening attendance (in previous 12 or 24 m) | Median 0% (range 0% ‐ 48.4%) Reported in 7 studies |

Median 37.1% (range 0% ‐ 88%) Reported in 36 studies |

Median 35.4% (range 0% ‐ 87.8%) Reported in 43 studies |

| Longest duration of follow‐up (median)* | Median 6 months (range 3 ‐ 48) Number reporting n = 14 |

Median 12 months (range 1 ‐ 30): Number reporting n = 49 |

Median 12 months (range 1 ‐ 48) Number reporting n = 63 |

| Intervention target (modified EPOC classification) | Median number of targets in intervention arm = 2 Participant n = 14 (87.5%) Healthcare professional n = 4 (25%) Healthcare system n = 4 (25%) |

Median number of targets in intervention arm = 3 Participant n = 31 (62%) Healthcare professional n = 31 (62%) Healthcare system n = 37 (74%) |

Median number of targets in intervention arm = 3 Participant n = 45 (68.2%) Healthcare professional n = 35 (53%) Healthcare system n = 41 (62.1%) |

Mansberger 2015 reported follow‐up data to 48 months but intervention offered to intervention and control group after 18 months and data reported at 12 and 24 months.

We used PROGRESS elements to describe the characteristics of participants in the included studies that could have an impact on equity of access to health services. With the exception of gender (reported in 93.9% of studies) and ethnicity (reported in 56.1% of studies), the characteristics of participants were poorly described, and the relative effectiveness of the interventions for subgroups in terms of PROGRESS elements was never reported. Seventeen studies (25.8%) were conducted in disadvantaged populations and none were carried out in low‐ or middle‐income countries.

Types of setting

Details of study location and setting are given in Table 6. Most of the studies (62.1%) were conducted in the USA, 21.2% in Europe and 16.7% elsewhere. The setting was primary care in 77.7%, secondary care in 10.6% and unclear in 12.1%.

Intervention content in terms of QI components (coded using the modified EPOC taxonomy)

Interventions were either specifically targeted at improving attendance for DRS (N = 16) or were part of a general QI intervention to improve diabetes care (N = 50). For studies comparing any intervention to usual care, most studies provided no description of usual care, which precluded coding of the comparator arm.

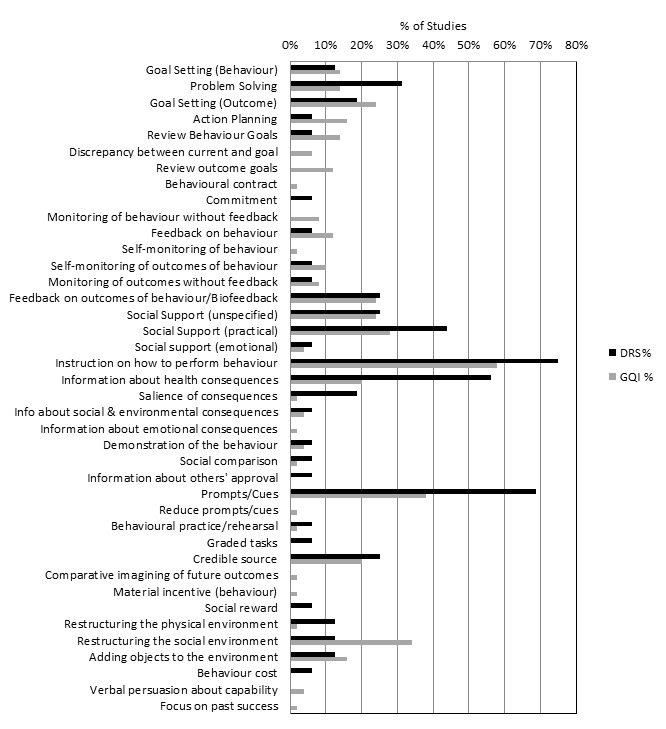

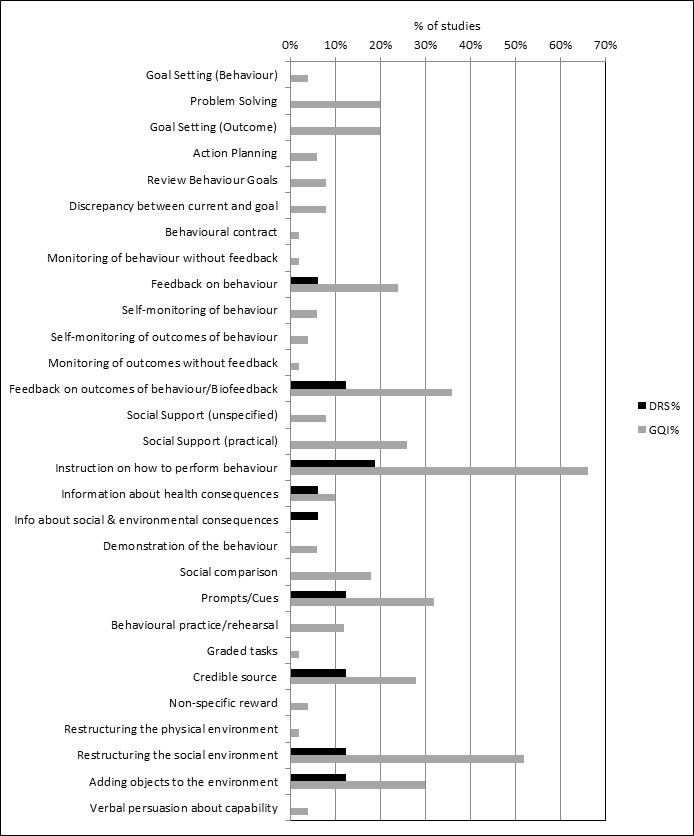

All 12 QI intervention components, as defined by the modified EPOC taxonomy, were used in at least one study (Figure 2). Generally, interventions were multifaceted, with several QI components per intervention arm (median 3, range 1 ‐ 7). For interventions specifically targeting DRS attendance, the most commonly used QI components were ‘Patient reminders (56% of studies)’ and ‘Patient education (75%) (Figure 3). For general QI interventions, a greater number and range of strategies were used, including: ‘Patient education’ (48% of studies), ‘Promotion of self‐management’ (40%), ‘Case management’ (40%), ‘Clinician education’ (38%) and ‘Team changes’ (36%).

2.

Quality improvement components used in intervention arm of included studies. (DRS=diabetic retinopathy screening, GQI=general quality improvement).

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Intervention content in terms of BCTs (coded using the BCT taxonomy)