Abstract

Background

People with dementia who are being cared for in long‐term care settings are often not engaged in meaningful activities. Offering them activities which are tailored to their individual interests and preferences might improve their quality of life and reduce challenging behaviour.

Objectives

∙ To assess the effects of personally tailored activities on psychosocial outcomes for people with dementia living in long‐term care facilities.

∙ To describe the components of the interventions.

∙ To describe conditions which enhance the effectiveness of personally tailored activities in this setting.

Search methods

We searched ALOIS, the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group’s Specialized Register, on 16 June 2017 using the terms: personally tailored OR individualized OR individualised OR individual OR person‐centred OR meaningful OR personhood OR involvement OR engagement OR engaging OR identity. We also performed additional searches in MEDLINE (Ovid SP), Embase (Ovid SP), PsycINFO (Ovid SP), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Web of Science (ISI Web of Science), ClinicalTrials.gov, and the World Health Organization (WHO) ICTRP, to ensure that the search for the review was as up to date and as comprehensive as possible.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials offering personally tailored activities. All interventions included an assessment of the participants' present or past preferences for, or interests in, particular activities as a basis for an individual activity plan. Control groups received either usual care or an active control intervention.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently checked the articles for inclusion, extracted data and assessed the methodological quality of included studies. For all studies, we assessed the risk of selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias and detection bias. In case of missing information, we contacted the study authors.

Main results

We included eight studies with 957 participants. The mean age of participants in the studies ranged from 78 to 88 years and in seven studies the mean MMSE score was 12 or lower. Seven studies were randomised controlled trials (three individually randomised, parallel group studies, one individually randomised cross‐over study and three cluster‐randomised trials) and one study was a non‐randomised clinical trial. Five studies included a control group receiving usual care, two studies an active control intervention (activities which were not personally tailored) and one study included both an active control and usual care. Personally tailored activities were mainly delivered directly to the participants; in one study the nursing staff were trained to deliver the activities. The selection of activities was based on different theoretical models but the activities did not vary substantially.

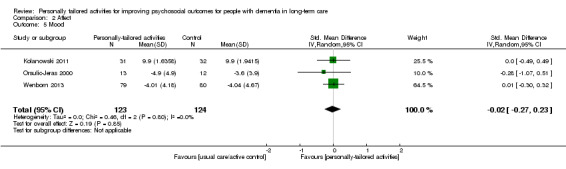

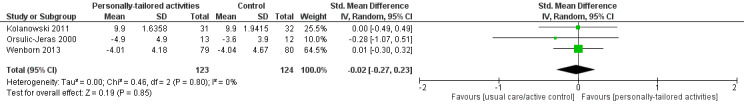

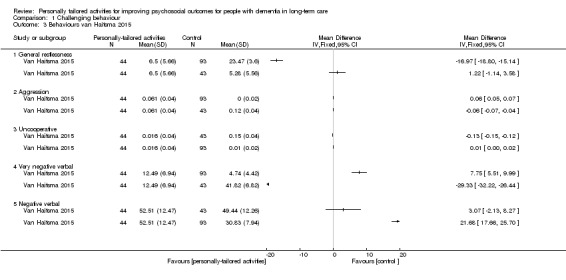

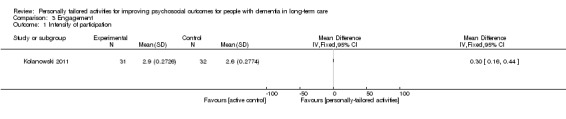

We found low‐quality evidence indicating that personally tailored activities may slightly improve challenging behaviour (standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.21, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.49 to 0.08; I² = 50%; 6 studies; 439 participants). We also found low‐quality evidence from one study that was not included in the meta‐analysis, indicating that personally tailored activities may make little or no difference to general restlessness, aggression, uncooperative behaviour, very negative and negative verbal behaviour (180 participants). There was very little evidence related to our other primary outcome of quality of life, which was assessed in only one study. From this study, we found that quality of life rated by proxies was slightly worse in the group receiving personally tailored activities (moderate‐quality evidence, mean difference (MD) −1.93, 95% CI −3.63 to −0.23; 139 participants). Self‐rated quality of life was only available for a small number of participants, and there was little or no difference between personally tailored activities and usual care on this outcome (low‐quality evidence, MD 0.26, 95% CI −3.04 to 3.56; 42 participants). We found low‐quality evidence that personally tailored activities may make little or no difference to negative affect (SMD −0.02, 95% CI −0.19 to 0.14; I² = 0%; 6 studies; 589 participants). We found very low quality evidence and are therefore very uncertain whether personally tailored activities have any effect on positive affect (SMD 0.88, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.32; I² = 80%; 6 studies; 498 participants); or mood (SMD −0.02, 95% CI −0.27 to 0.23; I² = 0%; 3 studies; 247 participants). We were not able to undertake a meta‐analysis for engagement and the sleep‐related outcomes. We found very low quality evidence and are therefore very uncertain whether personally tailored activities improve engagement or sleep‐related outcomes (176 and 139 participants, respectively). Two studies that investigated the duration of the effects of personally tailored activities indicated that the intervention effects persisted only during the delivery of the activities. Two studies reported information about adverse effects and no adverse effects were observed.

Authors' conclusions

Offering personally tailored activities to people with dementia in long‐term care may slightly improve challenging behaviour. Evidence from one study suggested that it was probably associated with a slight reduction in the quality of life rated by proxies, but may have little or no effect on self‐rated quality of life. We acknowledge concerns about the validity of proxy ratings of quality of life in severe dementia. Personally tailored activities may have little or no effect on negative affect and we are uncertain whether they improve positive affect or mood. There was no evidence that interventions were more likely to be effective if based on one specific theoretical model rather than another. Our findings leave us unable to make recommendations about specific activities or the frequency and duration of delivery. Further research should focus on methods for selecting appropriate and meaningful activities for people in different stages of dementia.

Plain language summary

Personally tailored activities for people with dementia in long‐term care

Background

People with dementia living in nursing or residential homes often have too little to do. Activities which are available may not be meaningful to them. If a person with dementia has the chance to take part in activities which match his or her personal interests and preferences, this may lead to a better quality of life, may reduce challenging behaviour such as restlessness or aggression, and may have other positive effects.

Purpose of this review

We wanted to investigate the effects of offering people with dementia who were living in care homes activities tailored to their personal interests.

Studies included in the review

In June 2017 we searched for trials that had offered some participants an activity programme based on their individual interests (an intervention group) and had compared them with other participants who were not offered these activities (a control group).

We found eight studies including 957 people with dementia living in care homes. Seven of the studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), meaning that it was decided at random whether participants were in the intervention group or the control group. One study was not randomised, which puts it at higher risk of biased results. The number of participants included in the studies ranged from 25 to 180. They all had moderate or severe dementia and almost all had some kind of challenging behaviour when the study started. The studies lasted from 10 days to nine months. In all the studies, the people in the intervention groups got an individual activity plan. Most of the activities took place in special sessions run by trained staff, but in one study, the nursing staff were trained to provide the activities during the daily care routine. The activities actually offered in the different studies did not vary a lot, but the number of activity sessions per week and the duration of the sessions did vary. In five studies, the control group got only the usual care delivered in care homes; in three studies, the control group got different activities that were not personally tailored; one study had both types of control group.

The quality of the trials and how well they were reported varied, and this affected our confidence in the results.

Key findings

Offering personally tailored activities to people with dementia living in care homes may slightly improve challenging behaviour when compared with usual care, although we did not find evidence that it was any better than offering activities which were not personally tailored. In one study, staff members reported that people in the group receiving personally tailored activities had a slightly worse quality of life than the control group. Personally tailored activities may have little or no effect on the negative emotions expressed by the participants. Because the quality of some of the evidence was very low, we could not draw any conclusions about effects on the participants' positive emotions, mood, engagement (being involved in what is happening around them) or quality of sleep. Only two studies mentioned looking for harmful effects; none were reported. None of the studies measured effects on the amount of medication participants were given, or effects on carers.

Conclusions

We concluded that offering activity sessions to people with moderate or severe dementia living in care homes may help to manage challenging behaviour. However, we did not find any evidence to support the idea that activities were more effective if they were tailored to people's individual interests. More research of better quality is needed before we can be certain about the effects of personally tailored activities.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Personally tailored activities compared to usual care or unspecific activities for people with dementia.

| Personally tailored activities compared to usual care or unspecific activities for people with dementia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with dementia Setting: Long‐term care facilities Intervention: Personally tailored activities Comparison: usual care or unspecific activities | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with usual care or unspecific activities | Risk with Personally tailored activities | |||||

| Quality of life (self‐rating by the participants; assessed with Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease scale; higher scores indicate a higher quality of life); follow‐up: 28 weeks | The mean quality of life was 33.00 (6.20) | MD 0.26 higher (3.04 lower to 3.56 higher) | ‐ | 42 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | Mean difference adjusted for baseline/demographic characteristics; clinical relevance (by study authors): 3 point difference; only about one‐third of the participants completed the self‐assessment. |

| Quality of life (proxy‐rating; assessed with Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease scale; higher scores indicate a higher quality of life); follow‐up: 28 weeks | The mean quality of life was 31.35 (4.68) | MD 1.93 lower (3.63 lower to 0.23 lower) | ‐ | 139 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | Proxy‐rating, mean difference adjusted for baseline/demographic characteristics; clinical relevance (by study authors): 3 point difference. |

| Challenging behaviour (assessed with different scales, higher scores indicate more challenging behaviour; follow‐up: range 10 days to 9 months | ‐ | SMD 0.21 SD lower (0.49 lower to 0.08 higher) | ‐ | 439 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 4 | |

| Adverse events; follow up: range 10 days to 4 weeks | Only 2 studies assessed adverse effects, but in both studies no adverse effects were reported. | ‐ | (2 RCTs) | ‐ | ||

| Positive affect (assessed with different scales, higher scores indicate a greater display of positive affect); follow‐up: range 10 days to 9 months | ‐ | SMD 0.88 SD higher (0.43 higher to 1.32 higher) | ‐ | 455 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3 4 5 | |

| Negative affect (assessed with different scales, higher scores indicate a greater display of negative affect); follow‐up: range 10 days to 9 months | ‐ | SMD 0.02 SD lower (0.19 lower to 0.14 higher) | ‐ | 589 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 4 | |

| Mood (assessed with different scales, lower scores indicate improved mood); follow‐up: range 4 weeks to 9 months | ‐ | SMD 0.02 SD lower (0.27 lower to 0.23 higher) | ‐ | 247 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3 6 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded 2 levels due to imprecision (wide confidence interval, crossing the borders of clinical relevance defined by the study authors in both directions)

2 Downgraded 1 level due to imprecision (wide confidence interval, crossing the border of clinical relevance defined by the study authors in 1 direction)

3 Downgraded one level due to study limitations: high risk of bias due to lack of adequate randomisation and allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors and recruitment bias in some included studies

4 Downgraded one level due to imprecision (wide confidence interval, crossing the border of small effects (SMD) in one direction)

5 Downgraded one level due to inconsistency: substantial heterogeneity

6 Downgraded two levels due to imprecision (wide confidence interval, crossing the border of small effects (SMD) in both directions)

Background

Description of the condition

Dementia is a syndrome of progressive cognitive and functional decline, threatening the affected person’s capacities to perform activities and to communicate. Approximately six million people in Europe are affected by dementia and the absolute number is expected to rise (Prince 2013; Wittchen 2011). In long‐term care facilities, the estimated prevalence of dementia ranges between 40% and 80% (Bernstein 2007; Nygaard 2003).

People with dementia living in long‐term care facilities often spend their time not engaged in meaningful activities or uninvolved with other people (Cohen‐Mansfield 2009a; Edvardsson 2014; Hill 2010; Kolanowski 2006). However, people with dementia wish to be involved in activities which meet their interests and are perceived as meaningful (Murphy 2007; Phinney 2007; Vernooij‐Dassen 2007).

To be engaged in activities experienced as meaningful might increase quality of life in residents with dementia (Cooney 2009; Edvardsson 2014; Murphy 2007; Zimmerman 2005). However, activities offered in nursing homes tend to be passive, e.g. watching television and listening to music, and are often not perceived as meaningful by people with dementia (Harmer 2008), or are addressed to residents with better cognitive and functional status (Buettner 2003; Edvardsson 2014). Hence, a lower cognitive function in people with dementia is associated with fewer social interactions and less participation in activities (Chen 2000; Dobbs 2005; Edvardsson 2014). Understimulation might magnify challenging behaviour, e.g. apathy, boredom, depression, loneliness and agitation (Cohen‐Mansfield 1992; Cohen‐Mansfield 2011; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012c). To be meaningful for a specific person with dementia, activities have to be individualised based on the person's interests, since the judgment of whether an activity is meaningful differs both between different people with dementia and between people with dementia and nurses (Harmer 2008).

Offering personally tailored activities to people with dementia primarily aims to improve psychosocial outcomes, e.g. challenging behaviour or quality of life, rather than to increase cognitive function or to improve particular skills. Since a remarkable sense of self‐identity can persist until late stages of dementia (Cohen‐Mansfield 2006; Hubbard 2002; Mills 1997), the engagement in personally tailored activities could be beneficial for people in all stages of dementia.

Description of the intervention

Interventions offering personally tailored activities for people with dementia living in long‐term care facilities are likely to be complex interventions, comprising different types of activities and different ways of delivering the intervention (Craig 2008). We focus on interventions aimed at improving psychosocial outcomes (e.g. challenging behaviours or quality of life in people with dementia) rather than on interventions exclusively aimed at improving particular skills (e.g. basic activities of daily living, or cognitive function).

All interventions have to include an assessment of interests or preferences of the participants. Interventions can be based on specific models or concepts, e.g. the principles of Montessori or the concept of person‐centred care. The choice of activities offered should be based on the assessment of personal interests or preferences. Activities offered within the interventions include instrumental activities of daily living (e.g. housework, preparing a meal), arts and crafts (e.g. painting, singing), work‐related tasks (e.g. gardening), and recreational activities (e.g. games). The interventions can be delivered in groups or individually; duration and frequency of the sessions can differ. Providers of the interventions we expected to find include different professionals or a multidisciplinary team.

How the intervention might work

Being involved in personally tailored activities may evoke positive emotions like interest and reduce challenging behaviour (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2009b; Harmer 2008; Phinney 2007). Also, participating in such activities can increase feelings of engagement which can reduce feelings of boredom and loneliness (Cohen‐Mansfield 2009a), and increase quality of life (Hoe 2009; Murphy 2007; Zimmerman 2005). Further expected benefits cover the evocation of autobiographical events (Guétin 2009), the preservation of a person's identity, and increasing their occupation and maintaining their relationships (Harmer 2008). These positive effects may reduce the use of psychotropic medication in people with dementia and may also result in benefits for the caregiver (e.g. increased sense of competence, decreased burden of care).

Why it is important to do this review

There is an increasing need of effective non‐pharmacological interventions to improve psychosocial outcomes in people with dementia in clinical practice (Ballard 2013; O'Neil 2011). In several dementia guidelines, the use of non‐pharmacological interventions is recommended as a primary approach for behavioural and psychological symptoms (BPSD) (Azermai 2012; Ngo 2015; Vasse 2012). Interventions offering personally tailored activities could be a promising approach due to their potential effects on challenging behaviours, quality of life and the level of engagement of people with dementia. Several studies evaluated complex interventions offering personally tailored activities to people with dementia in long‐term care facilities (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Kolanowski 2011). These interventions are of complex nature due to different underlying theoretical models, the composition of components, the types of activities offered, and intensity and duration of delivery.

To assess the effects of complex interventions, a description of the interventions' components is required to ensure comparability and reduce heterogeneity (Shepperd 2009). Since the effectiveness of complex interventions is also influenced by implementation fidelity, this information should be incorporated, e.g. adherence, exposure, quality of delivery, participants’ responsiveness and adherence (Shepperd 2009).

Currently, no systematic review is available describing the characteristics of these interventions and summarising their effects on people with dementia. We intended this review to expand the knowledge on non‐pharmacological treatments aiming to improve psychosocial outcomes and quality of life of people with dementia living in long‐term care facilities. We also hoped the results would be helpful for decision making about the implementation of evaluated programmes offering personally tailored activities as well as for the development of new interventions.

Objectives

To assess the effects of personally tailored activities on psychosocial outcomes for people with dementia living in long‐term care facilities.

To describe the components of the interventions.

To describe conditions which enhance the effectiveness of personally tailored activities in this setting.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

In this review, we included individual or cluster‐randomised controlled trials, controlled clinical trials and controlled before‐after studies.

Types of participants

People with dementia living in long‐term care facilities, irrespective of the stage of dementia.

Types of interventions

All the interventions aimed to improve psychosocial outcomes by offering personally tailored activities to people with dementia in long‐term care. The aims of the interventions did not necessarily include the improvement of a particular skill. The interventions had to comprise two elements.

Assessment of the participants' present or former preferences for particular activities or interests. We accepted both unstructured assessments, e.g. asking for the interests of the person with dementia, or the use of validated tools, e.g. the self‐identity questionnaire (Cohen‐Mansfield 2010) or the NEO‐FFI (Kolanowski 2005). This assessment had to be performed primarily with the person with dementia; however, relatives or health professionals could also be informants, e.g. in later stages of dementia.

An activity plan tailored to the individual participant's present or former preferences. We accepted activities of various kinds: instrumental activities of daily living (e.g. housework, preparing a meal); arts and crafts (e.g. painting, singing); work‐related tasks (e.g. gardening); and recreational activities (e.g. games). The intervention could be delivered by different professionals, e.g. nurses, occupational therapists, social workers or psychologists. The intervention could be delivered either to a group or to individual participants.

We excluded interventions which offered (1) only one specific type of activity (e.g. music or reminiscence), (2) specific care approaches (e.g. person‐centred care) which included the delivery of activities, (3) multi‐component interventions comprising drug treatment and the delivery of activities, and (4) interventions exclusively aimed at improving cognitive function or other particular skills (e.g. communication, basic activities of daily living).

Comparison: other types of psychosocial interventions, placebo interventions (e.g. non‐specific personal attention), usual or optimised usual care.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Challenging behaviour, assessed by e.g. the Cohen‐Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI).

Quality of life, assessed by e.g. Dementia Care Mapping, EuroQol (EQ‐5D).

Secondary outcomes

Affect (i.e. expression of emotion), assessed by e.g. Observed Emotion Rating Scale.

Level of engagement, assessed by e.g. Observational Measurement of Engagement Assessment, Index of Social Engagement.

Mood, assessed by e.g. Dementia Mood Picture Test.

Other dementia‐related symptoms such as sleep disturbances, hallucinations or delusions, assessed by e.g. Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI).

Use of psychotropic medication.

Effect on the caregivers, e.g. caregivers' distress (assessed by e.g. Neuropsychiatric Inventory Caregiver Distress Scale (NPI‐D)), sense of competence (assessed by e.g. Sense of Competence Questionnaire (SCQ)), quality of life, health status (assessed by e.g. General Health Questionnaire (GHQ‐12)).

Adverse effects of the interventions employed (e.g. injuries).

Cost.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched ALOIS (www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/alois) — the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group's Specialized Register — on 16 June 2017. The search terms used were: personally tailored OR individualized OR individualised OR individual OR person‐centred OR meaningful OR personhood OR involvement OR engagement OR engaging OR identity.

ALOIS is maintained by the Information Specialists of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group and contains studies in the areas of dementia prevention, dementia treatment and cognitive enhancement in healthy individuals. The studies are identified from:

monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO and LILACS;

monthly searches of a number of trial registers: ISRCTN; UMIN (Japan's Trial Register); the WHO portal (which covers ClinicalTrials.gov; ISRCTN; the Chinese Clinical Trials Register; the German Clinical Trials Register; the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials; and the Netherlands National Trials Register, plus others);

quarterly search of the Cochrane Library’s Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

six‐monthly searches of grey literature source: ISI Web of Science Conference Proceedings.

Details of the search strategies used for the retrieval of reports of trials from the healthcare databases, CENTRAL and conference proceedings can be viewed in the ‘Methods used in reviews’ section within the editorial information about the Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group.

We also performed additional searches in many of the sources listed above to ensure that the search for the review was as up to date and as comprehensive as possible. The search strategies we used can be seen in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We screened reference lists and citations of all potentially eligible publications for additional trials and for additional data (e.g. interventions development, process‐related data).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two reviewers (RM, AR) independently assessed all titles and abstracts obtained from the search for inclusion according to the inclusion criteria. We resolved disagreements by discussion or, if necessary, we referred to a third reviewer (GM).

Data extraction and management

Two reviewers (RM, AR) extracted data independently from all included publications using a standardised form. We checked results for accuracy and, in case of disagreement, called in a third reviewer (GM) to reach consensus.

For each study we extracted the following data: study design, characteristics of participants, baseline data, length of follow‐up, outcome measures, study results, and adverse effects. For each intervention we extracted the following information: method of assessing the individual preferences, types of activities offered, duration and frequency of the intervention's components, information of the implementation fidelity. Additionally, we collected information on the intervention's development (i.e. underlying theoretical considerations, components and delivery) and process‐related data. For cluster‐randomised trials, we also extracted estimates of the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICCC) if possible. If necessary, we contacted study authors to obtain missing information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We followed the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed risk of bias in each study for the following criteria: selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, detection bias, and additional design‐related criteria for cluster‐randomised and non‐randomised trials. Two authors (RM, AR) independently assessed methodological quality of studies in order to identify any potential sources of systematic bias. In case of unclear or missing information, we contacted the corresponding author of the trial. We assessed the quality of evidence using the criteria proposed by the GRADE working group (Guyatt 2011).

Measures of treatment effect

For challenging behaviour and affect (including mood), we used the standardised mean difference (SMD), which is the absolute mean difference divided by the standard deviation (SD), since the included studies used different rating scales (see also Unit of analysis issues). We used the post‐intervention means of each scale's total score or subscore (for affect). For continuous data that were not included in a meta‐analysis, we calculated the mean difference (MD). If it was not feasible for us to calculate the MD, e.g. in case of substantial baseline imbalances, we presented the study results in narrative form, e.g. as mean values and standard deviation).

None of the trials included in this review reported dichotomous data of interest to this review.

Unit of analysis issues

For all studies, we investigated whether individuals or groups (clusters) were randomised.

For cluster‐randomised trials, we extracted information about the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) if available. Only one of the included cluster‐randomised trials reported the ICC with values ranging from 0 to 0.3 (Wenborn 2013). We used the ICC values of the corresponding outcomes (0.19 for challenging behaviour and 0.09 for affect) from this study to incorporate the cluster effect in the studies without information on the ICC — Cohen‐Mansfield 2007 and Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a — by re‐calculating the effective sample size using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The number of included study participants and clusters in all three studies are comparable.

For cross‐over trials, we checked the risk of a carry‐over effect. There was no evidence for the occurrence of a carry‐over effect in the one included cross‐over study (van der Ploeg 2013); after the intervention sessions the values of most outcomes returned to the level assessed before the activities were offered. We used data from the complete study period for both conditions in our analysis since no results for the first period were available. We cannot be sure to have avoided a unit‐of‐analysis bias; however, this bias is conservative, being expected to lead to an under‐estimate of the intervention effect (Higgins 2011).

One study included four study groups (three different intervention groups and one control group) (Kolanowski 2011). We excluded two intervention groups from the analysis since they did not meet our inclusion criteria (see Description of studies) and we included only two groups (one intervention and the control group) in the analysis.

Dealing with missing data

For all included studies, numbers of participants lost to follow‐up, with reasons, were extracted and presented in Characteristics of included studies. Where information was missing, the study authors were contacted and asked for additional information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined studies for clinical diversity in terms of characteristics of the interventions, participants, and outcomes. We combined data in meta‐analyses only if we considered the studies to be sufficiently clinically homogeneous. To test for statistical heterogeneity, we used the Chi² and I² statistics.

Assessment of reporting biases

In order to minimise the risk of publication bias we performed a comprehensive search, including multiple databases, snowballing techniques and searching trials registers to identify unpublished or ongoing trials. We did not investigate publication bias by means of a graphical funnel plot analysis since we included only a small number of studies. To detect cases of selective reporting in the included studies, we checked trial register information if available.

Data synthesis

We performed meta‐analyses for challenging behaviour, for positive and negative affect and for mood. In all cases, we used a random‐effects model as planned in the protocol due to the clinical diversity of the interventions or statistical heterogeneity (I² > 50%). In one study, different types of (positive and negative) affect were reported (Van Haitsma 2015). To include this study in the meta‐analysis, we combined the corresponding outcomes for positive and negative affect by calculating a combined score. To calculate the variance of the combined means, we assumed a positive correlation of 0.5 between the individual outcomes of each category. In the meta‐analysis for mood, the scales used in two studies differed in the direction of the scale (Orsulic‐Jeras 2000; Wenborn 2013). We re‐calculated the data of this study using the methods from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (we multiplied the mean values by −1 as described in chapter 9.2.3.2) (Higgins 2011).

We did not perform meta‐analysis for any other outcomes and present the results in a narrative form.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted the pre‐planned subgroup analyses for studies with and without an active control group. Since we included one study in both subgroup analyses (this study — Van Haitsma 2015 — compared the intervention group with both an active and a usual care control), we split the intervention group using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Chapter 16.5.4) (Higgins 2011). Where applicable, we also explored possible causes of heterogeneity by conducting pre‐planned analyses excluding studies with non‐overlapping confidence intervals (CI).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis to explore the effects of including the study, for which we calculated the combined outcome for positive and negative affect (see Data synthesis).

Summary of findings

We used the GRADE approach to assess the quality of evidence for the most important outcomes. We assessed the quality of the evidence by judging study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias (Guyatt 2011). To determine imprecision, we defined the borders for minimal important difference as defined by study authors; e.g. in case of quality of life (Wenborn 2013), and for the analyses using the SMDs, we used an effect size of 0.2, which is described as a small effect for SMD in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (chapter 12.6.2) (Higgins 2011). We rated quality of evidence as high, moderate, low or very low (Guyatt 2011). We created 'Table 1' for the outcomes 'challenging behaviour', 'positive affect' and 'negative affect' with GRADEpro GDT.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

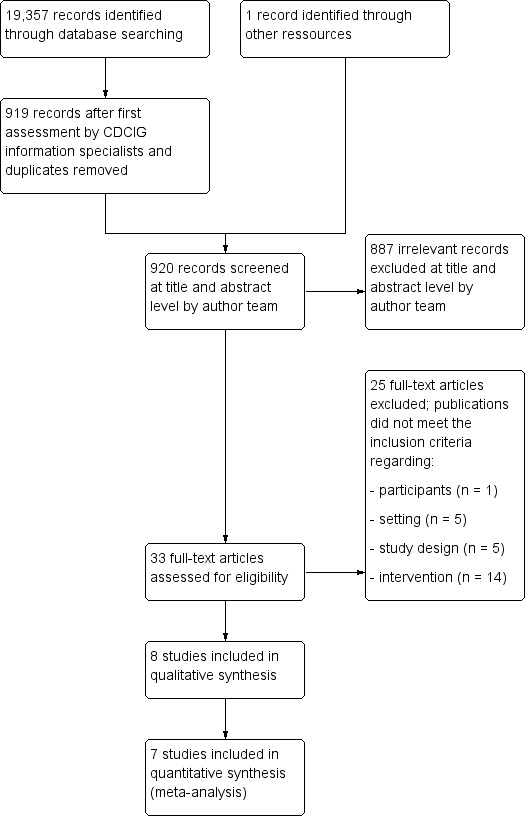

The search retrieved a total of 19,357 citations (Figure 1). The Information Specialists of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group carried out an initial assessment; then two authors independently screened titles and abstracts of 919 records for potential eligibility. Thirty‐three publications were screened in full text and eight studies met all inclusion criteria (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Kolanowski 2011; Orsulic‐Jeras 2000; Richards 2005; van der Ploeg 2013; Van Haitsma 2015; Wenborn 2013).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Seven included studies were randomised controlled trials (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Kolanowski 2011; Richards 2005; van der Ploeg 2013; Van Haitsma 2015; Wenborn 2013); and one study was a non‐randomised clinical trial (Orsulic‐Jeras 2000). Three of the RCTs used cluster‐randomisation (the units of allocation were nursing homes or nursing home wards) (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Wenborn 2013); three allocated individual participants (Kolanowski 2011; Richards 2005; Van Haitsma 2015); and one used a cross‐over design (van der Ploeg 2013). In the study by Wenborn 2013, matched pairs were randomised.

Setting and Participants

Six studies were conducted in the USA (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Kolanowski 2011; Orsulic‐Jeras 2000; Richards 2005; Van Haitsma 2015); one in Australia (van der Ploeg 2013); and one in the UK (Wenborn 2013). Six studies recruited participants from several nursing homes (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Kolanowski 2011; Richards 2005; van der Ploeg 2013; Wenborn 2013), the number of facilities ranging from 4 to 16. Two studies recruited participants from one facility; one study included participants from one large non‐profit nursing home (Van Haitsma 2015); and one study recruited people with dementia from a special care unit (Orsulic‐Jeras 2000).

A total of 1080 participants were recruited and 957 participants completed the studies. The number of participants completing the studies ranged from 25 (Orsulic‐Jeras 2000) to 180 (Van Haitsma 2015).

The mean age of participants ranged from 78 to 88 years. In six studies most participants were female (63% to 92%); in one study the proportion of women was 48% (Richards 2005). In seven studies the mean MMSE score was lower than 12 (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Orsulic‐Jeras 2000; Richards 2005; van der Ploeg 2013; Van Haitsma 2015; Wenborn 2013); and in one study the score ranged from 12 to 15 (Kolanowski 2011).

In three studies, challenging behaviour at baseline was an inclusion criterion for participants (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Kolanowski 2011); and in one study, physical agitation at baseline was an inclusion criterion (van der Ploeg 2013). In three studies without these inclusion criteria, all participants showed some form of challenging behaviour or agitation (Orsulic‐Jeras 2000; Van Haitsma 2015; Wenborn 2013). One study offered no information on challenging behaviour (Richards 2005) (see Characteristics of included studies).

Description of the interventions

In seven of the interventions, personally tailored activities were offered directly to the participants (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Kolanowski 2011; Orsulic‐Jeras 2000; Richards 2005; van der Ploeg 2013). In one study, members of the nursing staff were trained to deliver the personally tailored activities to the study participants (Wenborn 2013).

In this section, we describe the included interventions using categories relevant for complex interventions (Hoffmann 2014; Möhler 2015).

Theoretical basis and components of the interventions

Choice of activities in the included studies was based on different theoretical models. The theoretical basis guided the selection of activities which could be offered to the participants, and the methods by which the interventions were individually tailored, i.e. how the activities were chosen for the individual participants.

The interventions in Cohen‐Mansfield 2007 and Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a were based on the Treatment Routes for Exploring Agitation (TREA) framework. Kolanowski 2011 used the Need‐Driven Dementia‐Compromised Behavior (NDB) model and tested three different treatment conditions. The principles of Montessori were used in two studies (Orsulic‐Jeras 2000; van der Ploeg 2013). The interventions by Richards 2005 and Wenborn 2013 were not based on a specific theoretical framework; however, in both studies the choice of activities followed predefined principles.

The Treatment Routes for Exploring Agitation (TREA) framework

The TREA framework provides a systematic approach for individualizing non‐pharmacological interventions to unmet needs of people with dementia and agitation (Cohen‐Mansfield 2000). The TREA framework assumes that different types of agitated behaviours have different aetiologies. To create an individual intervention, the aetiology of the agitated behaviour must be identified. Individual interventions have to be developed based on the remaining abilities of the individual, his/her deficits, e.g. in sensory perception, cognition, and mobility, and personal preferences, e.g. past work, hobbies, important relationships, and sense of identity. With the TREA framework, individual needs and preferences of people with dementia exhibiting agitated behaviours could be assessed by using information from formal or informal caregivers (e.g. nursing staff or family members, respectively), or by observing the person's behaviour and environment. The TREA framework "can be viewed as a decision tree that guides caregivers through the necessary steps for exploring and identifying underlying unmet needs that contribute to agitated behaviours" (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007).

In the studies by Cohen‐Mansfield 2007 and Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a, the TREA decision tree protocol was used to identify all agitated behaviours exhibited by the individual participants and the possible reasons for these behaviours. For each participant, a 4‐hour peak period of agitation was identified at baseline. The intervention was individualised and administered to each participant based on this peak period. Information on the needs and preferences of the participant was identified by providing his or her relatives with a questionnaire to complete, including items concerning the participant's medical history, self‐identity, and social functioning. Based on this assessment, corresponding activities were offered (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a).

Examples of activities offered are: individualised music, family videotapes and pictures, illustrated magazines and large print books, board games and puzzles, plush toys, sorting cards with pictures and words, stress balls, baby dolls, electronic massagers, pain treatment, outdoor trips to the garden of the nursing home, perfume, and Play‐Doh (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a).

Need‐Driven Dementia‐Compromised Behavior (NDB) model

The NDB model defines behavioural symptoms as an indicator showing unmet needs of people with dementia (Algase 1996). Two aspects are described as potential reasons for behavioural symptoms: background risk factors (neuropathology, cognitive deficits, physical function, and premorbid personality); and proximal precipitating factors (qualities of the physical and social environment, and physiological and psychological need states) (Algase 1996). In this model, personally tailored activities can be seen as proximal factors that meet individual needs, since they aim at enriching the physical and social environment by matching the individual's background factors (Kolanowski 2005).

In the studies by Kolanowski 2011, the activities offered based on the NDB model were individually tailored to the participants' cognitive and physical functional level and to their style of interest. Style of interest was defined by the participants' personality traits of extraversion (preferred amount of social stimulation) and openness (individual tolerance for the unfamiliar). Kolanowski 2011 assessed style of interest by the use of the form F from the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO‐PI‐R, Costa 1992). For choosing the activities, both the participants' style of interest and the cognitive and physical functional level was relevant. Kolanowski 2011 tested three treatment conditions based on this framework: (1) activities matched to the participants' (cognitive and physical) functional level, but opposite to their identified style of interest; (2) activities matched to the participants' style of interest, but not their functional level; (3) activities matched to both the participants' functional level and style of interest. Examples of activities offered are: games, puzzles, music (listening or making music), crafts (e.g. making a birdhouse), pet visits, sewing cards, cooking, painting (Kolanowski 2011). In this review, we considered only the activities matched both to the participants' functional level and style of interest to be personally tailored activities.

Principles of Montessori

The principles of Maria Montessori were developed to guide child education. They put emphasis on task breakdown, guided repetition, progression in difficulty from simple to complex, and the careful matching of demands to levels of competence. These principles were adapted to be used with people with dementia. Activities offered to people with dementia "are designed to tap procedural memory which is better preserved than verbal memory while minimising language demands and providing external cues to compensate for cognitive deficits" (van der Ploeg 2010).

In the study by van der Ploeg 2013 a maximum of 10 activities were selected based on discussion with families about participants' former interests and hobbies. Orsulic‐Jeras 2000 used the Myers Menorah Park/Montessori Assessment System (MMP/MAS) to individualise the activities. MMP/MAS is a Montessori‐based instrument and provides information on participants' areas of interest.

Examples of activities offered by Orsulic‐Jeras 2000 are: individual Montessori activities (with materials usually taken from the everyday environment e.g. utensils, bowls, flowers, baskets); group Montessori‐based activities (memory bingo); and a structured reading and discussion group. van der Ploeg 2013 offered activities like sorting cards or making puzzles from familiar photographs.

Individualized social activity intervention (ISAI)

The intervention by Richards 2005 was based on a conceptual framework which postulates (based on the two‐process model of sleep) that individualised activities can improve the homeostatic sleep drive and strengthen circadian processes; and that this may lead to improved nighttime sleep and decreased daytime sleep (Richards 2005).

The activities were preselected to match various interests as well as cognitive and functional abilities. About 100 different activities were identified by two therapeutic recreation specialists with more than 20 years of collective experience working with nursing home residents with dementia. A list was created comprising the following information for all activities: brief directions for use, which functional limitations preclude their use, and which previous interests of participants are associated with each activity. The activities were also grouped into activities which were appropriate for everyone, and those which were appropriate for participants with mild (MMSE > 15), moderate (MMSE 5 to 15), and severe (MMSE < 5) dementia. The activities offered were selected according to four characteristics of each participant: interests (work and leisure history), cognition and functional status (mobility, hearing, vision, fine motor skills), and napping patterns (time of unscheduled naps). This information was assessed by means of interviews with families, nursing staff, and participants, observation of participants' behaviour, chart review, and by using an Actigraph (for napping patterns).

Examples of the activities offered were listening to music, petting a toy cat, tossing a ball, writing a letter, playing checkers, making a wreath, preparing and serving a snack (Richards 2005).

Occupational therapy programme

Wenborn 2013 offered an occupational therapy programme. The intervention was developed by the primary author, an occupational therapist with experience in working with older people with dementia.

The intervention consists of two components.

An assessment of the care home's physical environment, including recommendations on how it could be adapted and enhanced to enable the residents to engage in activities.

An education programme for nursing staff aimed to enhance knowledge, attitudes and skills, based on the principles of experiential learning. The educational component comprised five two‐hour education sessions covering these topics: identify the residents' interests and abilities; choose and offer activities; review and record the outcomes. The care home manager joined the last session to agree an activity action plan for continued implementation of the programme. To ensure the use of the skills and tools in clinical practice, work‐based learning tasks with two residents were conducted between the educational sessions and one‐to‐one coaching sessions with the primary investigator were used. The activities were personalised to each resident by the use of the Pool Activity Level Checklist (Wenborn 2008).

Individualized Positive Psychosocial Intervention

The study by Van Haitsma 2015 was based on two theoretical models: the Self‐Determination Theory (Deci 2000); and Broaden‐and‐Build Theory (Fredrickson 2001). The Self‐Determination Theory proposes that all people have innate needs for autonomy and competence, which must be fulfilled for psychological well‐being; and the Broaden‐and‐Build Theory focusses on the critical role of positive emotions to improve the person's well‐being. The study is described as being based on the work of Kolanowski 2011, but it is not described how this study contributed to the design of the intervention or the study.

The Individualized Positive Psychosocial Intervention (IPPI) offered five basic types of activities reflective of the most common preferences.

Physical exercises (outdoor walk, work with clay).

Music (singing or listening to a favourite artist).

Reminiscence (reviewing family photos, writing letters).

Activities of daily living (manicures, preparing a snack).

Sensory stimulation (e.g. hand massage with lotion, smelling fresh flowers).

From each group, two or more specific activity options were offered (a total of 30 activity options). The activities were selected by researchers and clinicians for each resident based on the Preferences for Everyday Living Inventory‐Nursing Home (PELI‐NH; Van Haitsma 2000). The information was taken directly from the participant or from a family member, activity therapist, or other direct care staff.

Feasibility/pilot test

Richards 2005 tested their intervention in a pilot study (Richards 2001); the studies by Kolanowski 2011 and Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a used previous studies as a pilot‐test for their interventions (Kolanowski 2005; Cohen‐Mansfield 2007); and the intervention by Orsulic‐Jeras 2000 was based on experiences from an earlier project.

No information on a feasibility or pilot‐test was provided by Cohen‐Mansfield 2007, van der Ploeg 2013, Van Haitsma 2015, and Wenborn 2013.

Delivery of the intervention

In most studies, the interventions were delivered directly to the study participants (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Kolanowski 2011; Orsulic‐Jeras 2000; Richards 2005; van der Ploeg 2013; Van Haitsma 2015). In the study by Richards 2005, activities were delivered individually; however, when the same activity was selected for more than one participant at the same time, the activity was offered in groups of up to three participants. The intervention by Orsulic‐Jeras 2000 comprised both individual and group activities (see above: 'Theoretical basis and components of the interventions ‒ Principles of Montessori'). In the study by Wenborn 2013, members of the nursing staff were trained to select, plan and deliver the activities within daily care.

In all studies, trained staff delivered the interventions. Training was guided by written manuals or guidelines in three studies (van der Ploeg 2013; Van Haitsma 2015; Wenborn 2013); and a treatment fidelity plan in one study (Kolanowski 2011). The number and frequency of sessions delivered as well as the follow‐up period differed between studies. An overview is displayed in Table 1 (see also Characteristics of included studies).

Table 1 ‒Delivery of the intervention

| Reference | Delivered by | Frequency and duration of the sessions | Duration of follow‐up |

| Cohen‐Mansfield 2007 | Research assistant | Daily; up to 4 h per day (peak period of agitation) | 10 consecutive days |

| Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a | Research assistant | Daily; up to 4 h per day (peak period of agitation) | 10 consecutive days |

| Kolanowski 2011 | Research assistant | 5 days per week; up to 20 minutes twice per day (morning and afternoon) | 4 weeks (3‐week interventions period + 1‐week post‐intervention period) |

| Orsulic‐Jeras 2000 | Trained volunteer, nursing assistant or activities therapist | At least twice a week; individual activities 10 to 30 min, group activities 25 to 45 min, QAR 30 min to 1 h | 9 months |

| Richards 2005 | Nursing assistant | Daily; several sessions 15 to 30 min (max 1 to 2 h per day), between 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. | 21 consecutive days |

| van der Ploeg 2013 | Activity facilitators (psychologists or higher degree psychology students, received regular personal supervision throughout the study) | Twice a week; 30 min sessions (at times when participants' target behaviour was most frequent) | 4 weeks (2 weeks per condition) |

| Van Haitsma 2015 | Certified nursing assistants | 3 days per week; 10 min per session (not during mealtimes or shift change) | 3 weeks |

| Wenborn 2013 | Primary investigator | Not reported; five 2 h educational sessions for nursing staff | 28 weeks (16 weeks' intervention period + 12 weeks' post intervention period) |

Despite all studies basing the selection of the activities on an assessment of the participants' present or former preferences, no information was presented in any study about the number of participants who were able to express their individual interests or preferences. Also, no study reported information about the proportion of participants for whom preferences and interests were assessed through the primary caregiver or family members.

The degree of delivery of the interventions was assessed in three studies (Kolanowski 2011; Van Haitsma 2015; Wenborn 2013); and Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a assessed barriers to the intervention's implementation (Cohen‐Mansfield 2012b).

Kolanowski 2011 used a treatment fidelity plan to ensure the introduction of the intervention as planned. Also, the research assistants paid attention to potential confounding factors (e.g. pain, thirst, poor environmental conditions). Treatment fidelity was checked for 10% of the intervention sessions. Re‐training took place if the intervention was not implemented according to the protocol. Only one deviation from the protocol occurred.

Van Haitsma 2015 assessed implementation fidelity during randomly selected sessions. A member of the research team observed compliance with study procedures in both the intervention and active control group. Overall, adherence to protocol was 68%, with higher rates in the intervention group (73%) compared to the active control condition (60%).

In the study by Wenborn 2013, the number of staff attending each session was recorded and feedback regarding the work‐based learning activities was collected from nursing staff and residents. A mean staff attendance of 73% was recorded for the education sessions (range 63 to 86) and a mean uptake of 81% for the individual coaching sessions (range 49 to 100). Reasons for non‐attendance at the sessions included: being off duty (22%); annual leave (20%); on duty but not available (14%); sick leave (12%); study leave (11%); staff personal commitment (11%); and left the care home (9%). No information on the amount of activities delivered to the residents by the nursing staff was collected.

In the study by Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a, in approximately 22% of the sessions some participants were unwilling to participate in the activities offered, and 84% of the participants were unwilling to participate in at least one of the sessions (Cohen‐Mansfield 2012b).

Characteristics of the control conditions

An active control condition was used in three studies. Kolanowski 2011 offered a control group with activities that were functionally challenging and opposed to the participant's style of interest (based on the NDM model). van der Ploeg 2013 used non‐personalised one‐to‐one interactions aimed at engaging the participants in social interaction, e.g. general conversations or conversation based on newspaper stories and pictures. Van Haitsma 2015 offered standardised one‐to‐one social interaction activities (e.g. discussing a magazine).

In six studies, the control condition was usual care. (The study by Van Haitsma 2015 offered both an active control group and a control group with usual care). The nursing staff in the centres allocated to the control condition in Cohen‐Mansfield 2007 and Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a received a presentation on the different forms of agitation, their aetiologies and possible non‐pharmacological interventions. In the study by Orsulic‐Jeras 2000, the control group received the usual activities of the centre (individual, small group, and large group activities, including bingo, storytelling, trivia, exercise, modified sporting activities, watching movies, discussion groups, musical programmes, sensory stimulation, activities based on the participants' interests and hobbies, delivered by an activities therapist or nursing assistants). The participants in the control groups in the studies by Richards 2005, Van Haitsma 2015 and Wenborn 2013 received usual care of the nursing home, but no information on the type and amount of activities offered was published.

Outcomes and data collection methods

Challenging behaviour

In the studies by Cohen‐Mansfield 2007 and Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a, challenging behaviour was assessed with the Agitation Behavior Mapping Instrument (ABMI, Cohen‐Mansfield 1989a). ABMI is a 19‐item instrument to rate agitation in nursing homes by direct observation (a higher score indicates more agitation).

Kolanowski 2011 and Orsulic‐Jeras 2000 used the Cohen‐Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI, Cohen‐Mansfield 1989b) to assess challenging behaviour. The CMAI is a proxy‐rating instrument used by nurses to assess agitation and comprises four subscales (physically non‐aggressive behaviours, physically aggressive behaviours, verbally non‐aggressive behaviours, and verbally aggressive behaviours; range 0 to 29; a higher score indicates greater agitation). Kolanowski 2011 also used the Passivity in Dementia Scale (PDS), a proxy‐rating instrument with 53 items (range −16 to 40, a higher score indicates less passivity; Colling 2000).

van der Ploeg 2013 selected one specific behaviour for each participant based on the nurses’ rating in a two‐week period before baseline assessment by the CMAI. For each participant, it was rated by direct observation whether this specific behaviour occurred within 30 minutes in 1‐minute intervals. The observation resulted in an individual behaviour score for each participant ranging from 0 to 30 points per session. The outcome score (mean and SD) was calculated using the observations from all sessions (n = 1.056 observations from all study participants). A higher score indicates a more frequent behaviour.

Van Haitsma 2015 assessed different categories of verbal and nonverbal behaviour by direct observation. Within a 10‐minute "behaviour stream", the onset and cessation of specific behaviours were recorded. Verbal behaviour was categorised as very negative (swearing, screaming, mocking), negative (incoherent, repetitious statements, muttering), positive (coherent conversation, responding to questions), very positive (complimenting, joking) or no verbal behaviour. Nonverbal behaviour was categorised as: psychosocial task (manipulates or gestures toward an object, engages in conversation), restlessness (pacing, fidgeting, disrobing), null behaviour (stares with fixed gaze, eyes unfocused), eyes closed (sits or lies with eyes closed), aggression (hitting, kicking, pushing, scratching, spitting), uncooperative (pulling away, saying “no”, turning head or body away), and positive touch (appropriate touching, hugging, kissing, hand holding). Higher scores indicated a higher frequency of the behaviour.

Wenborn 2013 used the Challenging Behaviour Scale (CBS, Moniz‐Cook 2001) to assess the incidence, frequency and severity of challenging behaviour. The CBS is a 25‐item proxy‐rating instrument used by nurses (higher scores indicate more challenging behaviour).

Quality of life

Quality of life was assessed in only one study — Wenborn 2013 — by the use of the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QOL‐AD) scale (self‐ and caregiver‐rating) (Logsdon 1999). Higher scores indicate a higher quality of life.

Affect

Cohen‐Mansfield 2007 and Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a used Lawton’s Modified Behavior Stream (LMBS, Lawton 1996), covering the following modes of affect: pleasure, interest, anger, anxiety, and sadness. A higher score indicates greater display of the affect.

Kolanowski 2011, Orsulic‐Jeras 2000 and van der Ploeg 2013 used the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Affect Rating Scale (ARS, Lawton 1996), covering the following modes of affect: pleasure, anger, anxiety, sadness, interest, and contentment. A higher score indicates greater display of the affect. In the study by Kolanowski 2011, anger and sadness were not used due to the inability to obtain adequate reliability for their measure. In two studies, results were categorised as positive or negative affect (Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; van der Ploeg 2013); van der Ploeg 2013 used also the category neutral affect. van der Ploeg 2013 calculated outcome scores (mean and SD) based on the observations from all sessions (n = 1.056 observations from all study participants).

Van Haitsma 2015 assessed the duration of different types of affect by direct observation within a 10‐minute "behaviour stream". Positive affect included pleasure (smiling, laughing, singing, nodding) and alertness (eyes following object, intent fixation on object or person, visual scanning, eye contact maintained) and negative affect included sadness (crying, tears, moan, sigh, mouth turned down at corners), anger (clenched teeth, grimace, pursed lips, eyes narrowed), and anxiety (furrowed brow, motoric restlessness, repeated or agitated motion, hand wringing, leg jiggling). A higher score indicates more frequent occurrence of the specific type of affect.

Wenborn 2013 assessed anxiety by the use of the Rating Anxiety in Dementia scale (RAID, Shankar 1999), with scores of 11 or above indicating clinical anxiety.

Engagement

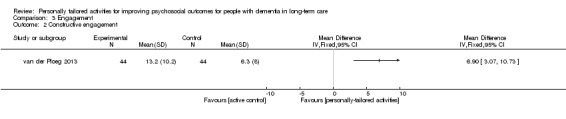

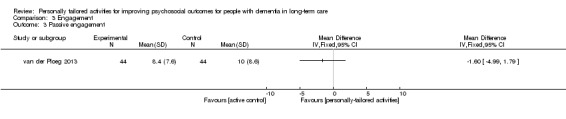

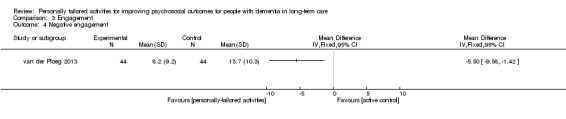

Three studies measured engagement. Kolanowski 2011 assessed time on task (minutes/seconds; range 0 to 20 minutes), and intensity of participation (ranging from 0 ("dozing") to 3 ("actively engaged"), based on Kovach 1998); Orsulic‐Jeras 2000 used the Myers Research Institute Engagement Scale (MRI‐ES, Judge 2000) (range 0 to 600, higher scores indicates more engagement); and van der Ploeg 2013 used the Menorah Park Engagement Scale (MPES) (range 0 to 30, higher values indicates more engagement) (Skrajner 2007).

Both scales assessed four types of engagement: constructive engagement (e.g. actively handling objects or talking); passive engagement (e.g. watching or listening); self‐engagement (e.g. fiddling with clothes); and non‐engagement (e.g. a blank stare). van der Ploeg 2013 combined non‐ and self‐engagement into the category "negative engagement"; and calculated outcome scores (mean and SD) based on the observations from all sessions (n = 1.056 observations from all study participants).

Mood

Kolanowski 2011 assessed mood by use of the Dementia Mood Picture Test (range 0 to 12, higher score indicates more positive mood; Tappen 1995). Orsulic‐Jeras 2000 and Wenborn 2013 assessed depression by the use of the Cornell Scale for Depression (CSD, Alexopoulos 1988). A score of 8 or above indicates depression.

Other outcomes

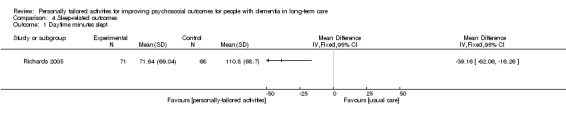

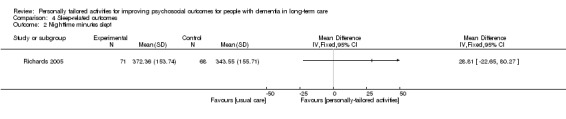

Richards 2005 assessed the daytime minutes slept, nighttime minutes to sleep onset, minutes slept, minutes awake, sleep efficiency, and the day/night sleep ratio using an Actigraph (motion‐sensing device), as well as the costs of implementing the intervention.

Duration of the effects

Two studies aimed to assess the duration of the intervention effects. Kolanowski 2011 assessed the intervention effect one week after the intervention period was completed; and van der Ploeg 2013 additionally assessed all outcomes after each session.

Excluded studies

Studies were excluded because the intervention or the study design did not meet our inclusion criteria. See Characteristics of excluded studies for the reasons for exclusion of the studies screened in full text.

Risk of bias in included studies

We contacted authors of all studies and asked for additional information on methodological details which were not reported in the publications (we sent one reminder to all non‐responding authors). Five authors responded to our request (A. Kolanowski, J. Cohen‐Mansfield, S. Orsulic‐Jeras, E. van der Ploeg, K. Van Haitsma) and four authors offered additional information; one author did not, for personal reasons.

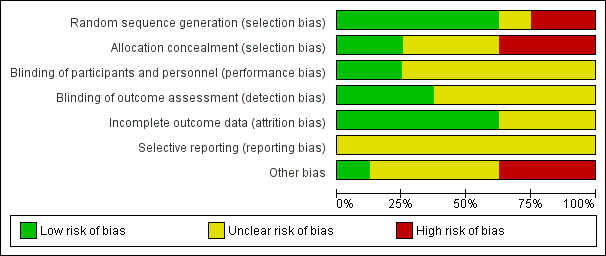

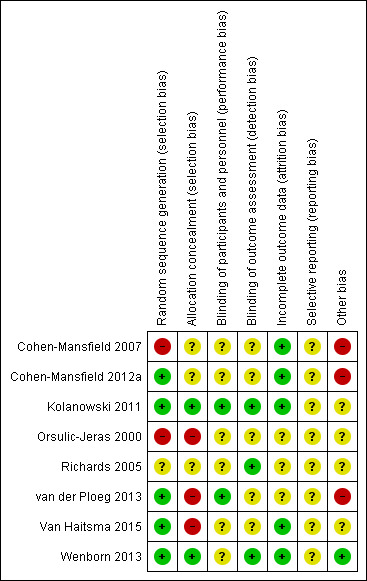

The methodological quality of the included studies varied. We judged two studies to have no domains in which the risk of bias was high (Kolanowski 2011; Wenborn 2013). We judged all the other studies to be at high risk of bias in at least one domain (see Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; Figure 3 and Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The randomisation sequence was adequately generated in five studies (Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Kolanowski 2011; van der Ploeg 2013; Van Haitsma 2015; Wenborn 2013). Van Haitsma 2015 used a two‐step randomisation procedure. In the first step the included nursing home units were allocated to deliver one of the two active treatments (intervention or active control); and in the second step, the eligible residents in each ward were allocated to the active treatment or usual care (eligible participants were identified before allocation).

No information on the method of sequence generation was available in two studies (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Richards 2005). We considered the risk of bias in this domain to be unclear for Richards 2005. In the study by Cohen‐Mansfield 2007 two clusters were not assigned randomly due to preferences of the facility managers so we judged the risk of bias in this domain to be high.

Group allocation was adequately concealed in two studies (Kolanowski 2011; Wenborn 2013). In three studies no information on the allocation concealment was available (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Richards 2005) (risk of bias judged to be unclear); and in two studies allocation was not concealed (van der Ploeg 2013; Van Haitsma 2015) (risk of bias judged to be high). In two cluster‐randomised studies, the participants were identified after the allocation of clusters (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a).

In the study by Orsulic‐Jeras 2000 group allocation was not performed at random. Participants were allocated to the groups using matching based on the MMSE score, Myers Menorah Park/Montessori Assessment System (MMP/MAS) and the reading subtest of the Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT3). We considered this study to be at high risk of selection bias.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel was adequate in two studies (Kolanowski 2011; van der Ploeg 2013); both studies offered a form of active treatment to all participants. In six studies, blinding of participants and personnel was not possible (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Orsulic‐Jeras 2000; Richards 2005; Van Haitsma 2015; Wenborn 2013). We considered it to be unclear whether this introduced a bias.

Outcome assessors were blinded to group allocation in three studies (Kolanowski 2011; Richards 2005; Wenborn 2013). In five studies blinding of outcome assessors was not possible, because data were collected by proxies, such as unblinded nursing staff. Two studies attempted to assess the impact of the lack of blinding on the study results. Ten and 25 intervention sessions were videotaped and the outcomes were assessed by a blinded rater (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a). There was a high agreement between the blinded and unblinded rater. Generally, we considered it to be unclear whether the lack of blinding led to a bias.

Incomplete outcome data

In six studies attrition rates were low and reasons for attrition were documented (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Kolanowski 2011; Richards 2005; Van Haitsma 2015; Wenborn 2013). In the study by van der Ploeg 2013 the attrition rate was more than twice as high as anticipated (anticipated attrition rate 10%; actual attrition rate 23% (13/57)). In the study by Orsulic‐Jeras 2000, only 25 of 44 participants completed the study, but the group allocation of the participants lost to follow‐up was not reported. We considered the risk of attrition bias for these studies to be unclear, since the reasons for attrition were available and there was no evidence that attrition was due to the intervention.

Selective reporting

Four studies were registered, but all retrospectively (Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Kolanowski 2011; van der Ploeg 2013; Wenborn 2013); and a protocol was published for one study (van der Ploeg 2013). The primary outcome was defined in four studies (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007, Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a, van der Ploeg 2013; Wenborn 2013). Based on this information, results for all outcomes were reported as planned. We considered the risk of selective reporting bias in all studies to be unclear due to the retrospective or absent registration.

Other potential sources of bias

We considered there to be a high risk of bias in three studies (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; van der Ploeg 2013). There was a high risk of unit‐of‐analysis bias in Cohen‐Mansfield 2007 and Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a, since neither study considered the cluster effect in their analyses. The study by van der Ploeg 2013 was at high risk of a unit‐of‐analysis bias since no paired data were available.

We considered the risk of other bias to be unclear in four studies since they did not define a primary outcome and did not include an adequate adjustment for multiple testing (Kolanowski 2011; Orsulic‐Jeras 2000; Richards 2005; Van Haitsma 2015).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

Challenging behaviour

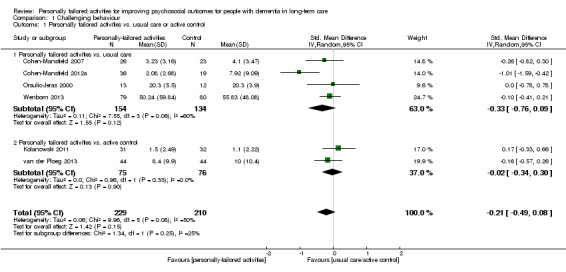

We performed a meta‐analysis for challenging behaviour, including six studies (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Kolanowski 2011; Orsulic‐Jeras 2000; van der Ploeg 2013; Wenborn 2013). One study assessing behaviour was not included in the meta‐analysis because the assessed types of behaviours were not comparable with the behavioural outcomes used in the other studies (Van Haitsma 2015).

We used the standardised mean difference (SMD), calculated from mean values assessed during or directly after the intervention period or session. For two studies, the number of participants was re‐calculated to incorporate the cluster effect, using an estimate of the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a ‒ see Unit of analysis issues). We used a random‐effects model since there was clinical diversity and evidence for moderate heterogeneity (I² = 50%). Higher scores indicate more challenging behaviour.

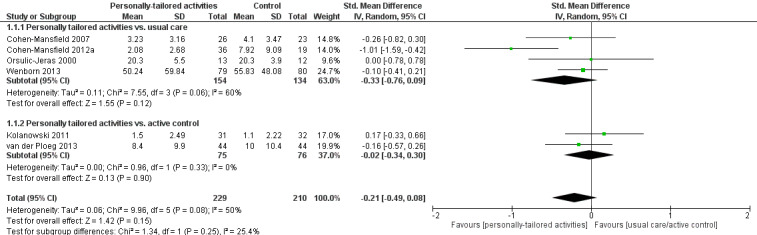

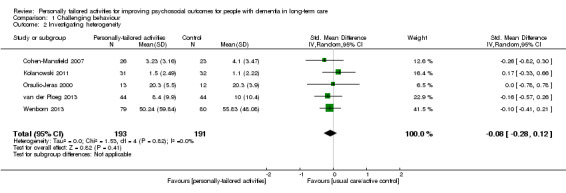

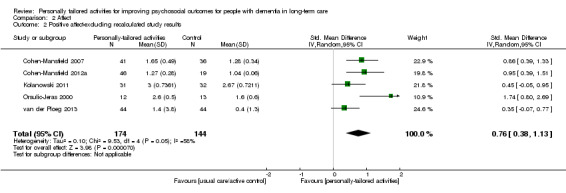

For challenging behaviour, we found low‐quality evidence (downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision) that personally tailored activities may slightly reduce challenging behaviour (SMD −0.21, 95% CI −0.49 to 0.08; I² = 50%; random‐effects model; 6 studies; 439 participants; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). Compared with studies only including a usual care control group, personally tailored activities may slightly reduce challenging behaviour (SMD −0.33, 95% CI −0.76 to 0.09; 288 participants; I² = 60%; random‐effects model; 4 studies; 288 participants; Figure 4), but personally tailored activities may have little or no effect on challenging behaviour compared with studies including active control groups (SMD −0.02, 95% CI −0.34 to 0.30; I² = 0%; random‐effects model; 2 studies; 151 participants; Figure 4). However; there is no statistically significant difference between the results of the usual care active control subgroups (test for subgroup differences P = 0.25, I² = 25.4%). To further explore the potential reasons for heterogeneity, an analysis was performed excluding one study (Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a), which appeared to be an outlier. After excluding this study, the I² was reduced to 0% and the effect size was reduced to little or no effect (low‐quality evidence, SMD −0.08, 95% CI −0.28 to 0.12; 5 studies; 384 participants; Analysis 1.2). We could not explain the heterogeneity based on the characteristics of this study, e.g. population, intervention or outcome measures.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Challenging behaviour, Outcome 1 Personally tailored activities vs. usual care or active control.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Challenging behaviour, outcome: 1.1 Personally tailored activities vs. usual care or active control.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Challenging behaviour, Outcome 2 Investigating heterogeneity.

In the study by Van Haitsma 2015, the outcomes of general restlessness, aggression, uncooperative behaviour, very negative and negative verbal behaviour seemed to best represent challenging behaviour. Higher scores indicate a higher frequency of the behaviour. We found low‐quality evidence (downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision) that personally tailored activities may slightly improve general restlessness compared to usual care (MD −16.97, 95% CI −18.80 to −15.14; 137 participants) but may make little or no difference compared to the active control group (MD 1.22, 95% CI −1.14 to 3.58; 87 participants). Aggression and uncooperative behaviours were rarely observed in all groups; we found low‐quality evidence (downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision) that personally tailored activities may have little or no effect on aggression and uncooperative behaviours (aggression: personally tailored activities vs usual care MD 0.06, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.07; 137 participants; personally tailored activities vs active control MD −0.06, 95% CI −0.07 to −0.04; 87 participants. Uncooperative behaviour: personally tailored activities vs usual care MD 0.01, 95% CI −0.00 to 0.02; 137 participants; personally tailored activities vs active control MD −0.13, 95% CI −0.15 to −0.12; 87 participants). We also found low‐quality evidence (downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision) that personally tailored activities may slightly increase very negative verbal behaviour compared to usual care (MD 7.75, 95% CI 5.51 to 9.99; 137 participants) but may reduce very negative verbal behaviour compared to the active control group (MD −29.33, 95% CI −32.22 to −26.44; 87 participants). For negative verbal behaviours, we found low‐quality evidence (downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision) that personally tailored activities may slightly increase negative verbal behaviour compared to usual care (MD 21.68, 95% CI 17.66 to 25.70; 137 participants) and may make little or no difference to negative verbal behaviour compared to the active control group (MD 3.07, 95% CI −2.13 to 8.27; 87 participants).

Quality of life

Only one study investigated the effects of personally tailored activities on quality of life (Wenborn 2013). Quality of life was assessed by the study personnel (proxy‐rating) and by a small group of participants who were able to complete the assessment (self‐rating, n = 42 out of n = 139). Clinical relevance was defined by the study authors as three points on the scale used (higher scores indicates better quality of life). For proxy‐rated quality of life, there was moderate‐quality evidence (downgraded one level for imprecision) that personally tailored activities were associated with a slight reduction in quality of life compared to usual care (MD −1.93, 95% CI −3.63 to −0.23; adjusting for baseline and demographic characteristics; 139 participants). For self‐rated quality of life, there was low‐quality evidence (downgraded two levels for imprecision) indicating little or no difference between personally tailored activities and usual care (MD 0.26, 95% CI −3.04 to 3.56; adjusting for baseline and demographic characteristics; 42 participants).

Secondary outcomes

Affect

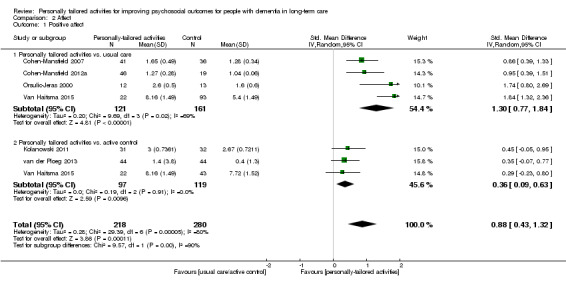

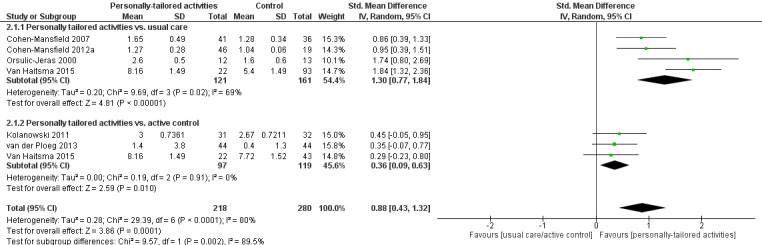

We performed meta‐analyses for positive and negative affect (including six studies in each analysis) and mood (including three studies). For positive affect, we used the results from four studies assessing pleasure (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a; Kolanowski 2011; Orsulic‐Jeras 2000), from one study assessing a combination of pleasure and contentment (van der Ploeg 2013), and for one study we calculated a combination of pleasure and alertness (Van Haitsma 2015; see Data synthesis).

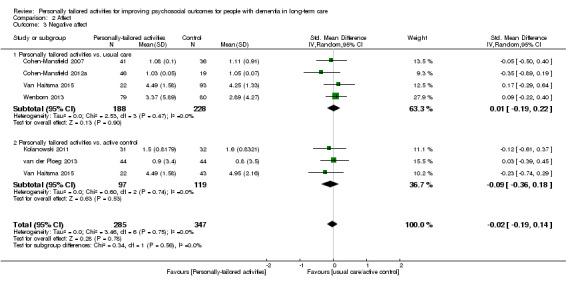

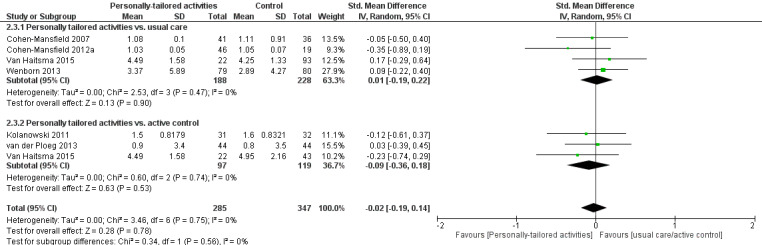

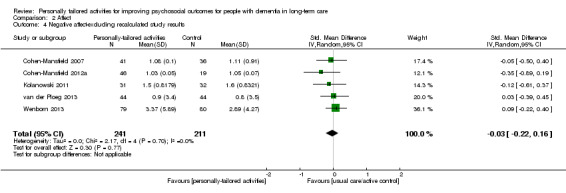

For negative affect, we used the following study data: negative affect calculated from anger, anxiety, and sadness (Cohen‐Mansfield 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield 2012a), negative affect calculated from anger, sadness, and anxiety/fear (van der Ploeg 2013), anxiety or fear (Kolanowski 2011), and anxiety (Wenborn 2013). From Van Haitsma 2015, we calculated negative affect from sadness, anger, and anxiety (see Data synthesis).