Abstract

Background

The global prevalence of childhood and adolescent obesity is high. Lifestyle changes towards a healthy diet, increased physical activity and reduced sedentary activities are recommended to prevent and treat obesity. Evidence suggests that changing these health behaviours can benefit cognitive function and school achievement in children and adolescents in general. There are various theoretical mechanisms that suggest that children and adolescents with excessive body fat may benefit particularly from these interventions.

Objectives

To assess whether lifestyle interventions (in the areas of diet, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and behavioural therapy) improve school achievement, cognitive function (e.g. executive functions) and/or future success in children and adolescents with obesity or overweight, compared with standard care, waiting‐list control, no treatment, or an attention placebo control group.

Search methods

In February 2017, we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE and 15 other databases. We also searched two trials registries, reference lists, and handsearched one journal from inception. We also contacted researchers in the field to obtain unpublished data.

Selection criteria

We included randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of behavioural interventions for weight management in children and adolescents with obesity or overweight. We excluded studies in children and adolescents with medical conditions known to affect weight status, school achievement and cognitive function. We also excluded self‐ and parent‐reported outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

Four review authors independently selected studies for inclusion. Two review authors extracted data, assessed quality and risks of bias, and evaluated the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach. We contacted study authors to obtain additional information. We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. Where the same outcome was assessed across different intervention types, we reported standardised effect sizes for findings from single‐study and multiple‐study analyses to allow comparison of intervention effects across intervention types. To ease interpretation of the effect size, we also reported the mean difference of effect sizes for single‐study outcomes.

Main results

We included 18 studies (59 records) of 2384 children and adolescents with obesity or overweight. Eight studies delivered physical activity interventions, seven studies combined physical activity programmes with healthy lifestyle education, and three studies delivered dietary interventions. We included five RCTs and 13 cluster‐RCTs. The studies took place in 10 different countries. Two were carried out in children attending preschool, 11 were conducted in primary/elementary school‐aged children, four studies were aimed at adolescents attending secondary/high school and one study included primary/elementary and secondary/high school‐aged children. The number of studies included for each outcome was low, with up to only three studies per outcome. The quality of evidence ranged from high to very low and 17 studies had a high risk of bias for at least one item. None of the studies reported data on additional educational support needs and adverse events.

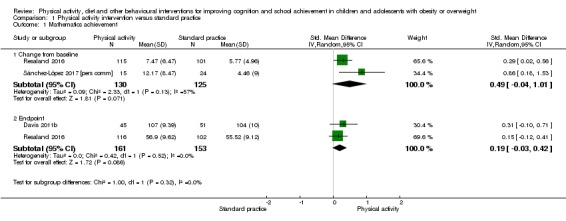

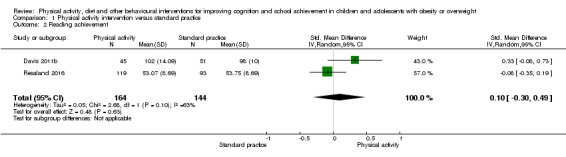

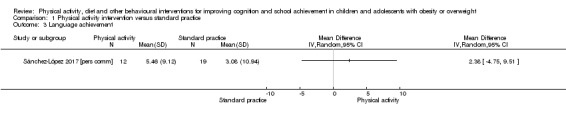

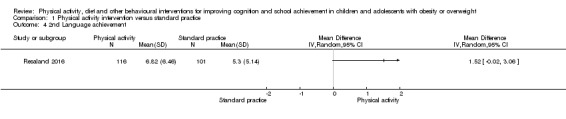

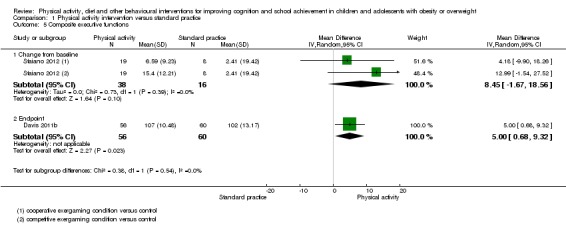

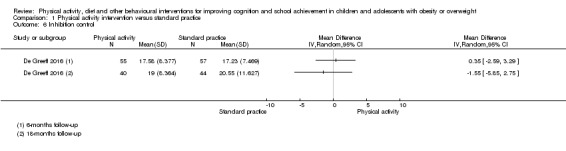

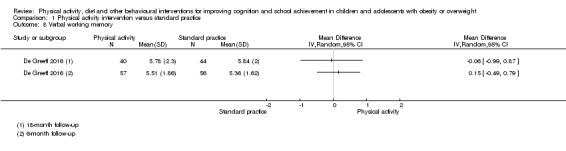

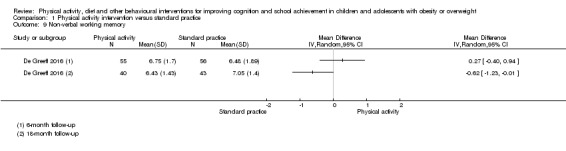

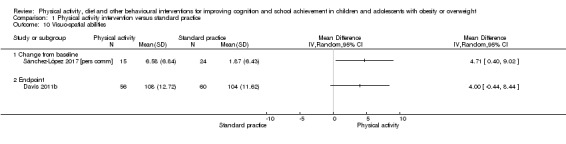

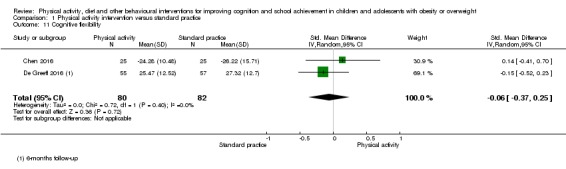

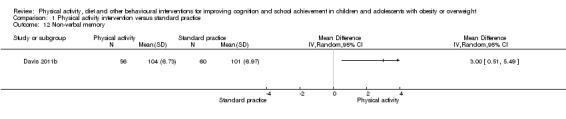

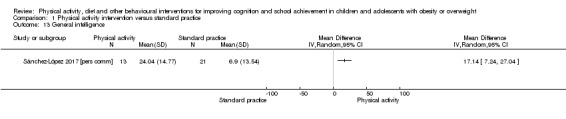

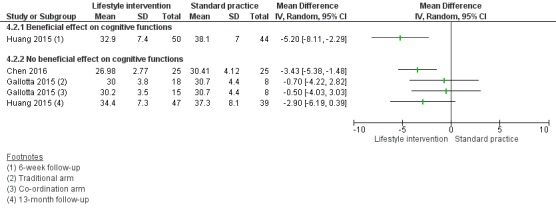

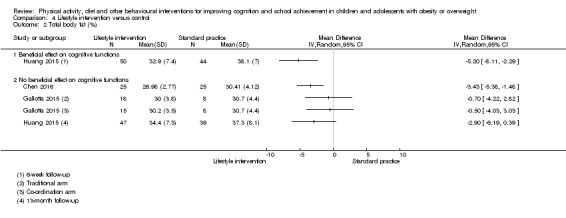

Compared to standard practice, analyses of physical activity‐only interventions suggested high‐quality evidence for improved mean cognitive executive function scores. The mean difference (MD) was 5.00 scale points higher in an after‐school exercise group compared to standard practice (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.68 to 9.32; scale mean 100, standard deviation 15; 116 children, 1 study). There was no statistically significant beneficial effect in favour of the intervention for mathematics, reading, or inhibition control. The standardised mean difference (SMD) for mathematics was 0.49 (95% CI ‐0.04 to 1.01; 2 studies, 255 children, moderate‐quality evidence) and for reading was 0.10 (95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.49; 2 studies, 308 children, moderate‐quality evidence). The MD for inhibition control was ‐1.55 scale points (95% CI ‐5.85 to 2.75; scale range 0 to 100; SMD ‐0.15, 95% CI ‐0.58 to 0.28; 1 study, 84 children, very low‐quality evidence). No data were available for average achievement across subjects taught at school.

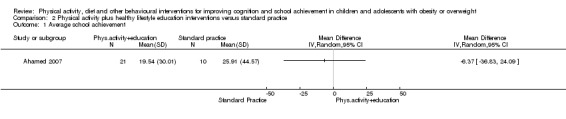

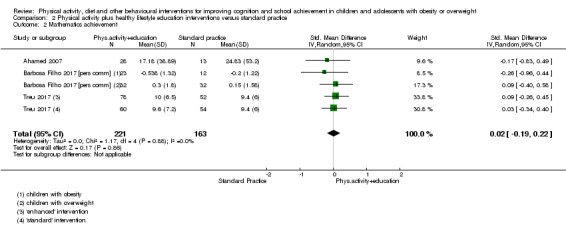

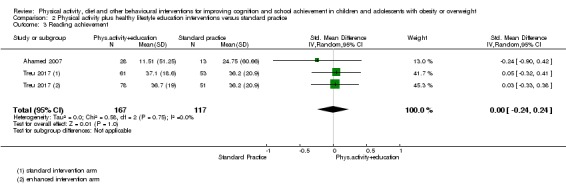

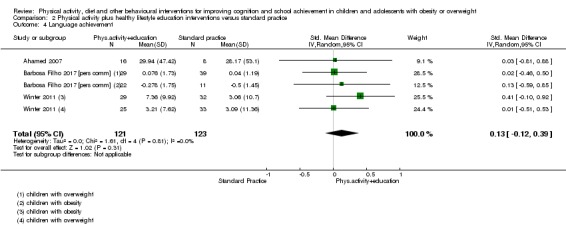

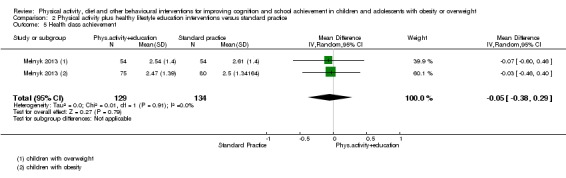

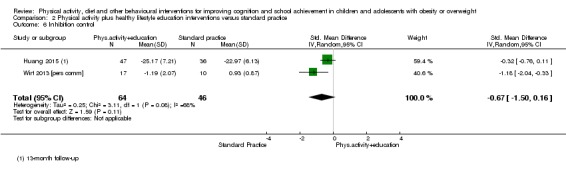

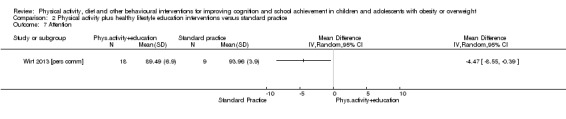

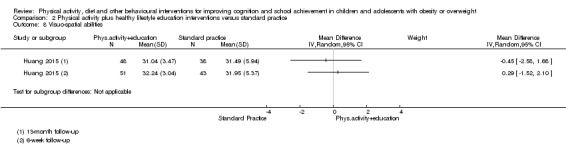

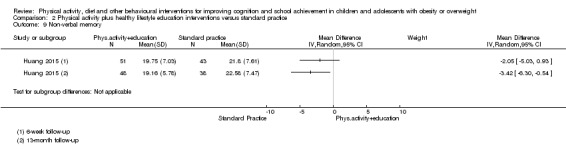

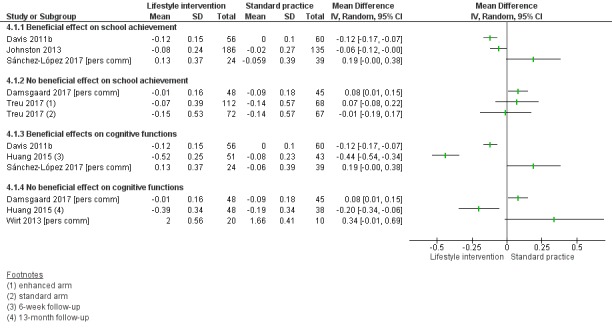

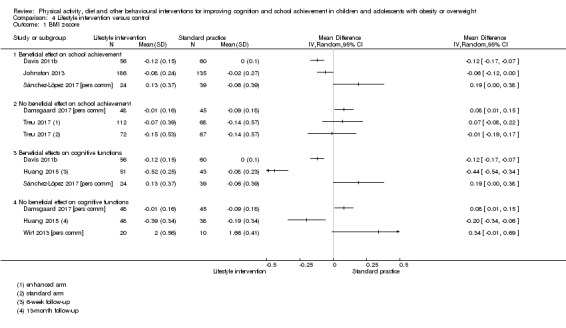

There was no evidence of a beneficial effect of physical activity interventions combined with healthy lifestyle education on average achievement across subjects taught at school, mathematics achievement, reading achievement or inhibition control. The MD for average achievement across subjects taught at school was 6.37 points lower in the intervention group compared to standard practice (95% CI ‐36.83 to 24.09; scale mean 500, scale SD 70; SMD ‐0.18, 95% CI ‐0.93 to 0.58; 1 study, 31 children, low‐quality evidence). The effect estimate for mathematics achievement was SMD 0.02 (95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.22; 3 studies, 384 children, very low‐quality evidence), for reading achievement SMD 0.00 (95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.24; 2 studies, 284 children, low‐quality evidence), and for inhibition control SMD ‐0.67 (95% CI ‐1.50 to 0.16; 2 studies, 110 children, very low‐quality evidence). No data were available for the effect of combined physical activity and healthy lifestyle education on cognitive executive functions.

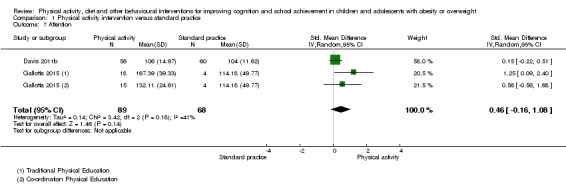

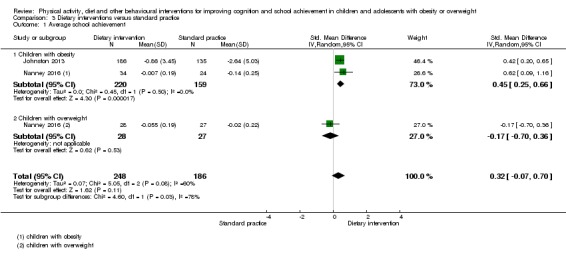

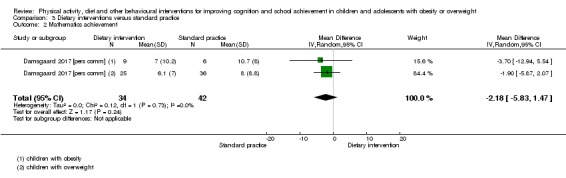

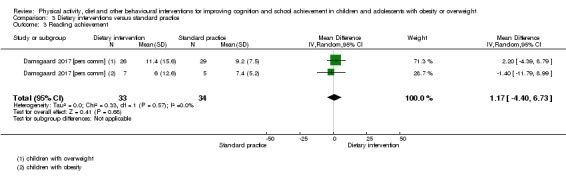

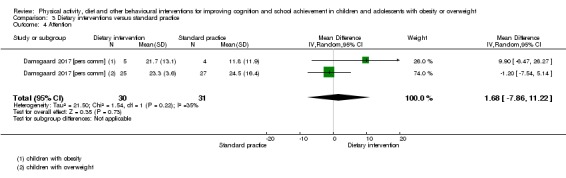

There was a moderate difference in the average achievement across subjects taught at school favouring interventions targeting the improvement of the school food environment compared to standard practice in adolescents with obesity (SMD 0.46, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.66; 2 studies, 382 adolescents, low‐quality evidence), but not with overweight. Replacing packed school lunch with a nutrient‐rich diet in addition to nutrition education did not improve mathematics (MD ‐2.18, 95% CI ‐5.83 to 1.47; scale range 0 to 69; SMD ‐0.26, 95% CI ‐0.72 to 0.20; 1 study, 76 children, low‐quality evidence) and reading achievement (MD 1.17, 95% CI ‐4.40 to 6.73; scale range 0 to 108; SMD 0.13, 95% CI ‐0.35 to 0.61; 1 study, 67 children, low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Despite the large number of childhood and adolescent obesity treatment trials, we were only able to partially assess the impact of obesity treatment interventions on school achievement and cognitive abilities. School and community‐based physical activity interventions as part of an obesity prevention or treatment programme can benefit executive functions of children with obesity or overweight specifically. Similarly, school‐based dietary interventions may benefit general school achievement in children with obesity. These findings might assist health and education practitioners to make decisions related to promoting physical activity and healthy eating in schools. Future obesity treatment and prevention studies in clinical, school and community settings should consider assessing academic and cognitive as well as physical outcomes.

Keywords: Adolescent, Child, Humans, Achievement, Educational Status, Exercise, Life Style, Executive Function, Mathematics, Overweight, Overweight/psychology, Overweight/therapy, Pediatric Obesity, Pediatric Obesity/psychology, Pediatric Obesity/therapy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Sensitivity and Specificity

Healthy weight interventions for improving thinking skills and school performance in children and teenagers with obesity

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to find out if healthy weight interventions can improve thinking skills and school performance in children and teenagers with obesity. Cochrane researchers collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question.

What are the key messages?

This updated review provides some evidence that school programmes that encourage healthier child weight may also provide ‘co‐benefits’ of thinking skills and school performance. However, we need more high‐quality healthy‐weight interventions that test thinking skills and school performance, as well as health outcomes.

What was studied in this review?

The number of children and teenagers with obesity is high worldwide. Some children and teenagers with obesity have health issues or are bullied because of their body weight. These experiences have been linked to problems in performing well in school, where they tend to perform less well in thinking tasks such as problem‐solving. Physical activity and healthy eating benefit a healthy body weight and improve thinking skills and school performance in children with a healthy weight. Studies found that healthy‐weight interventions can reduce obesity in children and teenagers, but it is unknown if and how well healthy‐weight interventions can improve thinking skills and school performance in children and teenagers with obesity.

What are the main results of this review?

The review authors found 18 studies which included a total of 2384 children and teenagers with obesity. Five studies assigned individual children to intervention or control groups. Thirteen studies allocated entire classes, school or school districts to the intervention and control group. Of the 18 studies, 11 involved children at primary/elementary‐school age. Eight studies offered physical activity interventions, seven studies combined physical activity programmes with healthy lifestyle education, and three studies offered dietary changes. The studies took place in 10 different countries. Seventeen studies had at least one flaw in how the study was done. This reduces the level of confidence we can have in the findings.

Few studies shared the same type of school performance or thinking skills. Only three studies reported the same outcome. None of the studies reported on additional educational support needs and harmful events. We found that, compared with usual routine, physical activity interventions can lead to small improvements in problem‐solving skills. This finding was based on high‐quality evidence. Moderate‐quality findings showed that physical activity interventions do not improve mathematics and reading achievement in children with obesity. Very low‐quality evidence also suggested no benefits of physical activity interventions for improving uncontrolled behavioural responses. General school achievement was not reported in studies comparing physical activity interventions with standard practice.

Studies that compared physical activity interventions plus healthy lifestyle education with standard practice were of low to very low quality. They showed no improvement in school achievement or uncontrolled behavioural responses in the intervention group compared to the control group. Problem‐solving skills were not reported in studies comparing physical activity plus healthy lifestyle education with standard practice.

Our findings indicate that changing knowledge about nutrition, and changing the food offered in schools can lead to moderate improvements in general school achievement of teenagers with obesity, when compared to standard school practice. Replacing packed school lunch with a nutrient‐rich diet plus nutrition education did not improve mathematics and reading achievement of children with obesity. However, the quality of evidence for general school achievement, mathematics and reading was low. This means that future research is very likely to change the results, because included studies showed some methodological weaknesses (for example, small numbers of children and a high dropout of children from studies). Problem‐solving skills and uncontrolled behavioural responses were not reported for dietary intervention studies.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched the scientific literature for relevant studies in February 2017.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Physical activity intervention compared to standard practice for improving cognition and school achievement in children and adolescents with obesity or overweight

| Physical activity interventions compared to standard practice for improving cognition and school achievement in children and adolescents with obesity or overweight | ||||||

| Patient or population: Children and adolescents with obesity or overweight Setting: Classroom and school environment or as after‐school activity in the USA, Norway, Spain, and The Netherlands Intervention: Physical activity interventions (active academic lessons, extracurricular games, after‐school group exercise) Comparison: Standard practice (e.g. usual Physical Education curriculum) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI)** | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

|

Assumed risk Standard practice |

Corresponding risk Physical activity |

|||||

|

School achievement: Average achievement across subjects taught at school |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No data available |

|

School achievement: Mathematics Assessed with: standardised national tests, BADyG‐I (numerical quantitative concepts) Follow‐up: range 13 weeks to 1 year immediately post‐intervention |

‐ | Compared to the control group, the mean mathematics achievement score in the intervention group was0.49 standard deviations higher (0.04 lower to 1.01 higher) | ‐ | 255 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | A standard deviation of 0.49 represents a moderate difference between groups |

|

School achievement: Reading Assessed with: WJ‐II test of achievement, standardised national tests Follow‐up: range 13 weeks to 7 months immediately post‐intervention |

‐ | Compared to the control group, the mean reading achievement score in the intervention group was 0.10 standard deviations higher (0.30 lower to 0.49 higher) | ‐ | 308 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | A standard deviation of 0.10 represents a small difference between groups |

| School achievement: Additional educational support needs | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No data available |

|

Cognitive function: Composite executive functions Assessed with: CAS Follow‐up: 13 weeks immediately post‐intervention |

The mean composite executive functions score in the control group was 102 scale points | The mean composite executive functions score in the intervention group was 5.00 points higher (0.68 higher to 9.32 higher) | ‐ | 116 (1 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | ‐ |

|

Cognitive function: Inhibition control Assessed with: SCWT, scale range: 0 to 100 Follow‐up: mean 18 months immediately post‐intervention |

The mean inhibition control score in the control group was 20.55 scale points | The mean inhibition control score in the intervention group was 1.55 points lower (5.85 lower to 2.75 higher) | ‐ | 84 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very Low2 | ‐ |

| Adverse events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No data available |

| *The effect sizes are differences in standard deviations. To facilitate interpretation we have used rules of thumb in interpretation of effect size (section 12.6.2 in Higgins 2011), where a standard deviation of 0.2 represents a small difference between groups, 0.5 represents a moderate difference, and 0.8 represents a large difference. ** Different assessment tools were used to assess school and cognitive outcomes. We therefore calculated standardised mean differences to assess the effect size between intervention and control groups. WJ: Woodcock‐Johnson; SCWT: Stroop test (colour and words); CAS: Das‐Naglieri‐Cognitive Assessment System; D–KEFS: Delis‐Kaplan Executive Function System; BADyG‐I: [Batería de aptitudes diferenciales y generals] Differential Aptitude Battery‐ General scale. MD: Mean difference, SMD: Standardised mean difference CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1Downgraded one level due to high risk of attrition bias. 2Downgraded three levels due to high risk of selection bias, attrition bias and imprecision (wide confidence intervals) due to a low sample size.

Summary of findings 2.

Physical activity plus healthy lifestyle education interventions compared to standard practice for improving cognition and school achievement in children and adolescents with obesity or overweight

| Physical activity plus healthy lifestyle education interventions compared to standard practice for improving cognition and school achievement in children and adolescents with obesity or overweight | ||||||

| Patient or population: Children and adolescents with obesity or overweight Setting: Classroom and school/preschool environment or in another community setting in the USA, Canada, Brazil, Spain, Germany, and Denmark Intervention: Physical activity plus healthy lifestyle education interventions Comparison: Standard practice (e.g. usual physical education/health education curriculum), and attention control (short‐term, less intensive programme) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI)** | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

|

Assumed risk Standard practice |

Corresponding risk Physical activity plus healthy lifestyle education |

|||||

|

School achievement: Average achievement across subjects taught at school Assessed with: CAT‐3, scale mean 500, SD 70 Follow‐up: 12 months immediately post‐intervention |

The mean score for average achievement across subjects taught at school in the control group was 19.50 grade points | The mean score for average achievement across subjects taught at school in the intervention group was 6.37 grade points lower (36.83 lower to 24.09 higher) | ‐ | 31 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | ‐ |

|

School achievement: Mathematics Assessed with: CAT‐3, standardised national tests, M‐CAT Follow‐up: range 4 months to 12 months immediately post‐intervention |

‐ | Compared to the control group, the mean mathematics achievement score in the intervention group was 0.02 standard deviations higher (0.19 lower to 0.22 higher) | ‐ | 384 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low2 | A standard deviation of 0.02 represents a small difference between groups |

|

School achievement: Reading Assessed with: CAT‐3, R‐CBM Follow‐up: mean 1 year immediately post‐intervention |

‐ | Compared to the control group, the mean reading achievement score in the intervention group was 0 standard deviations higher (0.24 lower to 0.24 higher) | ‐ | 284 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low3 | A standard deviation of zero represents no difference between groups |

| School achievement: Additional educational support needs | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No data available |

| Cognitive function: Composite executive functions | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No data available |

|

Cognitive function: Inhibition control Assessed with: SCWT, KiTAP (Go/No‐go) Follow‐up: range 12 months to 13 months immediately post‐intervention |

‐ | Compared to the control group, the mean inhibition control score in the intervention group was0.67 standard deviations lower (1.50 lower to 0.16 higher) | ‐ | 110 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low4 | A standard deviation of 0.67 represents a moderate difference between groups |

| Adverse events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No data available |

| *The effect sizes are differences in standard deviations. To facilitate interpretation we have used rules of thumb in interpretation of effect size (section 12.6.2 in Higgins 2011), where a standard deviation of 0.2 represents a small difference between groups, 0.5 represents a moderate difference, and 0.8 represents a large difference. ** Different assessment tools were used to assess school and cognitive outcomes. We therefore calculated standardised mean differences to assess the effect size between intervention and control groups. CAT‐3: Canadian Achievement Test, version 3; M‐CAT: Mathematics Concepts and Applications Test; R‐CBM: Reading–Curriculum‐Based Measurement; PPVT III: Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, version 3; SCWT: Stroop test (colour and words); KiTAP: [Kinderversion der Testbatterie zur Aufmerksamkeitsprüfung] Attention test battery for children; RCFT: Rey Complex Figure Test; CI: Confidence interval; SMD: Standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1Downgraded two levels due high risk of bias in attrition and unclear risk of bias for randomisation. 2Downgraded three levels due to high risk of bias in sequence generation, blinding of outcome assessors, and attrition; low sample sizes across studies resulting in imprecision; and inconsistent direction of intervention effects. 3Downgraded two levels due to high risk of bias in sequence generation, blinding of outcome assessors, and attrition and inconsistent direction of intervention effects. 4Downgraded two levels due to high risk of attrition bias; and selective reporting.

Summary of findings 3.

Dietary interventions compared to standard practice for improving cognition and school achievement in children and adolescents with obesity and overweight

| Dietary interventions compared to control for improving cognition and school achievement in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity | ||||||

| Patient or population: Children and adolescents with obesity or overweight Setting: Classroom and school environment in the USA and Denmark Intervention: Dietary interventions Comparison: Standard practice (e.g. usual school lunch)/wait‐list control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI)** | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

|

Assumed risk Standard practice |

Corresponding risk Dietary intervention |

|||||

|

School achievement: Average achievement across subjects taught at school Assessed with: teacher‐assessed grades Follow‐up: range 1 year to 2 years immediately post‐intervention |

‐ | Compared to the control group, the mean score for average achievement across subjects taught at school was 0.46 standard deviations higher (0.25 higher to 0.66 higher) in the intervention group | ‐ | 382 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | A standard deviation of 0.46 represents a moderate difference between groups |

|

School achievement: Mathematics Assessed with: standard national test, scale range 0 to 69 Follow‐up: mean 3 months immediately post‐intervention |

The mean change in mathematics achievement score ranged across control groups from 8.00 to 10.70 scale points | The mean change in mathematics achievement score in the intervention group was 2.18 scale points lower (5.83 lower to 1.47 higher) | ‐ | 76 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | ‐ |

|

School achievement: Reading Assessed with: standard national test, scale range 0 to 108 Follow‐up: mean 3 months immediately post‐intervention |

The mean change in reading achievement score ranged across control groups from 7.40 to 9.20 scale points | The mean change in reading achievement score in the intervention group was 1.17 scale points higher (4.40 lower to 6.73 higher) | ‐ | 67 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | ‐ |

| School achievement: Additional educational support needs | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No data available |

| Cognitive function: Composite executive function | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No data available |

| Cognitive function: Inhibition control | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No data available |

| Adverse events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No data available |

| *The effect sizes are differences in standard deviations. To facilitate interpretation we have used rules of thumb in interpretation of effect size (section 12.6.2 in Higgins 2011), where a standard deviation of 0.2 represents a small difference between groups, 0.5 represents a moderate difference, and 0.8 represents a large difference. ** Different assessment tools were used to assess school and cognitive outcomes. We therefore calculated standardised mean differences to assess the effect size between intervention and control groups. SMD: Standardised mean difference; MD: mean difference; CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1Downgraded two levels due to high risk of detection and attrition bias. 2Downgraded two levels due to high risk of detection bias and imprecision due to a low sample size.

Background

Description of the condition

Overweight and obesity are conditions of excessive body fat accumulation. In clinical practice, child and adolescent overweight and obesity are commonly identified by age‐ and gender‐specific body mass index (BMI) percentiles, BMI standard deviation scores, and waist circumference (WC) percentiles relative to a reference population (Reilly 2010; Rolland‐Cachera 2011).

The primary criteria used to define overweight and obesity include:

overweight: BMI or WC ≥ 85th percentile to 95th percentile, BMI > one standard deviation above the average;

obesity: BMI or WC > 95th percentile, BMI > two standard deviations above the average.

Also, BMI cut‐offs from the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) are often used as a definition of overweight and obesity. These age‐specific BMI cut‐offs were constructed to match the definition for overweight and obesity in adults (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, respectively) (Cole 2000). Recently, the IOTF BMI cut‐offs were reformulated to allow BMI to be expressed as standard deviation or percentile (Cole 2012).

A recent analysis of population data of children aged five to 19 years estimated that in 2016 obesity was identified in 50 million girls and 74 million boys worldwide (NCD Risk Factor Collaboration 2017). In the USA in 2014, the prevalence of child and adolescent obesity (BMI > 95th centile) was 9.4% (two to five years), 17.4% (six to 11 years), and 20.6% (12 to 19 years) (Ogden 2016). In Europe, obesity prevalence was on average 4.0% in adolescents, with vast differences between countries (Inchley 2017). For example, in Scotland the prevalence was 15% in adolescents aged 12 to 15 years (SHeS 2016). Childhood obesity prevalence is increasing in middle‐ and low‐income countries (NCD Risk Factor Collaboration 2017), for example, up to 40% of children in Mexico were living with obesity or overweight, 32% in Lebanon and 28% in Argentina (Gupta 2012).

Health problems are common in children and adolescents with obesity. These include cardiovascular conditions (e.g. hyperlipidaemia, hypertension), endocrinologic conditions (e.g. Type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome), gastrointestinal conditions (non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease), respiratory conditions (e.g. obstructive sleep apnoea), musculoskeletal disorders, (e.g. slipped capital femoral epiphysis) and psychosocial disorders (e.g. depression, anxiety) (Grant‐Guimaraes 2016; Han 2010; Puder 2010; Puhl 2007; Su 2015).

Cognitive deficits in children and adolescents (Bruce 2011; Delgado‐Rico 2012a; Liang 2013; Martin 2016; Yu 2010) and academic deficits in adolescents associated with obesity have been observed (Booth 2014; Martin 2017). Cognitive skills such as the ability to suspend prepotent or default responses (inhibition), to switch between rules and responses (cognitive flexibility), to keep and retrieve information while working on a new task (working memory), and to concentrate (attention) are understood to predict school achievement in children and adolescents (Jacob 2015). Collectively, these cognitive abilities are known as executive functions. Evidence from prospective cohort studies suggests that obesity‐related deficits in school achievement are more prevalent in adolescent girls than in boys and younger children (Martin 2017).

The academic consequences of adolescent obesity are shown to persist beyond schooling negatively influencing socioeconomic success. A Finnish longitudinal study (N = 9754, follow‐up 17 years) suggests that adolescent obesity predicts unemployment in later life, with educational achievement as a mediating factor (Laitinen 2002). A British birth cohort study (N = 12,537) indicates that adolescent obesity (at age 16 years) is associated with fewer years of schooling and predicts lower income in young women (at age 23 years), including those who are no longer obese (Sargent 1994). These findings were further confirmed by Han 2011, using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (N = 1974, follow‐up 12 to 16 years), and by Sabia 2012, using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (N = 12,445, follow‐up 13 years) in the USA. Findings from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 in the USA (N = 8427, follow‐up eight years) suggest that obese adolescents had a 39% lower chance of obtaining a college degree than peers of normal weight (Fowler‐Brown 2010). All of these studies accounted for a variety of confounding variables, including measures of socioeconomic status (e.g. parental education, household income).

Description of the intervention

Clinical guidelines for prevention and treatment of childhood obesity from countries such as the UK (NICE 2013; SIGN 2010), Australia (NHMRC 2003), Canada (Lau 2007) and Malaysia (Ismail 2004) recommend a multicomponent approach that combines:

reduced energy intake;

increased physical activity (≥ 60 minutes a day, moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity);

decreased sedentary behaviour (e.g. screen time less than two hours a day);

cognitive‐behavioural techniques (e.g. goal setting, self‐monitoring, self‐regulation).

The recently updated series of Cochrane Reviews on the treatment of childhood and adolescent obesity concluded that interventions aiming to alter eating habits, physical activity, and sedentary behaviour patterns in a family‐based setting were effective in achieving clinically meaningful weight reduction in children and adolescents (Al‐Khudairy 2017; Colquitt 2016; Mead 2017).

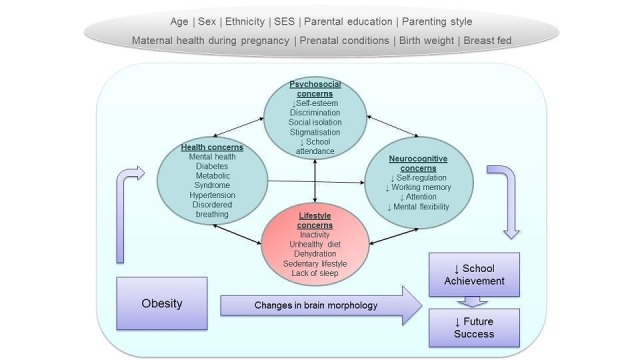

How the intervention might work

Obesity prevention and treatment interventions could benefit cognition, school achievement and future success of children and adolescents with obesity or overweight differently compared to children and adolescents with a healthy weight. The mechanisms relate to brain development, health and psychosocial consequences, cognitive‐behavioural regulation and lifestyle concerns associated with obesity (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Potential causal links between obesity and impaired cognitive function, school achievement and future success. Reverse causation may also occur when cognitive function, school achievement and future success can impact the 'mediating factors', and both in turn may cause worsening of obesity.

Brain development

Emerging evidence has linked obesity in children and adolescents to lower brain grey and white matter volume in brain regions associated with cognitive control and learning when compared to children and adolescents with healthy weight (Alarcón 2016; Alosco 2014; Kennedy 2016; Maayan 2011; Ou 2015; Yau 2014). This suggests a direct association between obesity and reduced cognitive and academic abilities, and is consistent with findings from animal models where manipulation of fat mass has been shown to affect cognition, probably as a result of inflammatory mechanisms.

Health and psychosocial consequences

Research has also identified obesity‐related health consequences and psychosocial concerns to be associated with lower school achievement and cognitive function. These potential indirect factors include poor sleep due to obesity‐related disordered breathing (Galland 2015; Tan 2014); hypertension (Lande 2015); Type 2 diabetes (Rofey 2015); metabolic syndrome (Yau 2012); decreased school attendance due to adverse physical and mental health (Pan 2013); and social isolation and bullying (Gunnarsdottir 2012a; Krukowski 2009). Reducing the risk of these health and psychosocial concerns, through reduction of obesity or increasing physical activity levels, or both, and improving diet and other obesity‐related behaviours, could have beneficial effects on cognitive function, school achievement and future success in children and adolescents with obesity.

Cognitive‐behavioural regulation

The association between lifestyle interventions for weight management and cognition and school achievement might be bidirectional. Research indicates that children with obesity show higher impulsivity and inattention and lower reward sensitivity, self‐regulation and cognitive flexibility compared with their healthy‐weight peers. These neurocognitive correlates were associated with uncontrolled food intake and physical activity behaviour, and thus are assumed to predict weight gain (Francis 2009; Hall 2014; Kulendran 2014; Levitan 2015; Nederkoorn 2006; Smith 2011) or reduction of weight status after an obesity treatment intervention (Naar‐King 2016; Nederkoorn 2007). Lifestyle interventions for weight management might positively impact the neurocognitive factors required for control of food intake. A randomised controlled trial conducted in 44 children (eight to 14 years of age) with obesity or overweight suggested that specific training of self‐regulatory abilities improved weight‐loss maintenance after an inpatient weight‐loss programme in the intervention group compared with the control group (Verbeken 2013). Findings from another randomised controlled overweight treatment programme involving 62 children (mean age 10.3 ± 1.1 years) showed improved problem‐solving skills after an intervention duration of six months (Epstein 2000). Inhibition control skills were improved in 42 obese adolescents from 12 to 17 years of age after 12 weeks of cognitive‐behavioural therapy (Delgado‐Rico 2012b).

Lifestyle interventions

Growing evidence has shown that the influence of lifestyle interventions, particularly physical activity and dietary intervention, lie beyond the alteration of energy balance. Many aspects of physical activity, diet and other behaviours have been demonstrated to benefit cognition and school achievement in children and adolescents, regardless of their body weight status, as summarised below.

Physical activity

Recently, Faught 2017 reported that meeting the Canadian recommendations for diet, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep at age 11 years was associated with favourable school achievement at age 12 (N = 4253). Low levels of physical fitness (Chaddock 2011; Davis 2011a; Raine 2013) and moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity physical activity have also been linked to impaired cognitive functions in children (Haapala 2017). In addition to the observational evidence, a substantial body of literature suggests a causal relationship between increased levels of physical activity and cognitive function or school achievement or both. For example, a meta‐analysis of 44 experimental and cross‐sectional studies (in participants aged four to 18 years) indicates that increased physical activity caused significant overall improvement in cognitive function and school performance (Hedge's g = 0.32; standard deviation (SD) 0.27) (Sibley 2003). A recent meta‐analysis of 21 experimental and quasi‐experimental studies in children aged four to 16 years (N = 4044) also reported a moderate positive effect of physical activity interventions on cognitive outcomes (Hedge's g = 0.46, 95% confidence interval 0.28 to 0.64) (Vazou 2016).

Physical activity may affect cognitive function and school achievement through physiological mechanisms (elevated blood circulation, increased levels of neurotrophins and neurotransmitters) (Dishman 2006), learning and motor developmental mechanisms (Pesce 2016a).

Dietary modification

Composition of the diet may impact cognition and school achievement by altering neurotrophic and neuroendocrine factors involved in learning and memory. As shown in animal research, these factors are decreased by high‐energy diets containing saturated fat and simple sugars, and are increased by diets that are rich in omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and micronutrients (Gomez‐Pinilla 2008; Kanoski 2011). These findings were also observed in children. Cross‐sectional data of school‐aged children linked dietary intake of omega‐3 fatty acids to increased memory performance (Baym 2014; Boucher 2011), while consumption of food rich in saturated fatty acids and refined sugar was associated with decreased memory performance (Baym 2014). Longitudinal observational data suggest that diets high in fat and sugar in preschool children (N = 3966; aged three to four years) are associated with decreased intelligence and school performance at primary/elementary school age (Feinstein 2008; Northstone 2011). A controlled healthy school meal intervention over three years in more than 80,000 children led to improved mathematics, English and science achievement (Belot 2011). Promotion of healthier school food at lunchtime and changes in the school dining environment over 12 weeks improved classroom on‐task behaviour in preschool children compared to controls (Golley 2010; Storey 2011). An improvement in dietary quality could therefore have beneficial effects on cognition and school achievement even without improved weight status.

Sedentary behaviour

A sedentary lifestyle in children, particularly television‐viewing for two or more hours a day, is associated with the development of obesity or overweight (review of 71 studies; Rey‐Lopez 2008) and may replace opportunities to engage in activities that promote scholastic and cognitive development. To our knowledge, there is no published literature on the effect of reduced sedentary behaviour and improved cognitive and academic outcomes of children and adolescents. However, epidemiological evidence suggests that high levels of sedentary behaviour are associated with reduced school achievement or cognitive abilities. For example, longitudinal data indicate that children younger than three years of age with low television exposure (less than three hours a day) performed better than those with high television exposure (three or more hours a day) in reading (N = 1031) and mathematics (N = 1797) (Peabody Individual Achievement Test) when at preschool age (Zimmerman 2005). Similarly, parent‐reported television viewing in preschool children was inversely related to mathematics achievement at age 10 years (N = 1314) (Pagani 2010) and reading achievement at age 10 to 12 years (N = 308) (Ennemoser 2007). Low TV exposure was also linked to improved school achievement in 8061 adolescents aged 16 years (Kantomaa 2016). Longer‐term educational outcomes may also be affected. Hancox 2005 found that young people (N = 980; follow‐up 21 years) with the highest television viewing time during childhood and adolescence tended to have no formal educational qualifications, and those with a university degree watched the least television during childhood and adolescence. Television viewing for three or more hours a day at age 14 years (N = 678) was associated with a two‐fold risk of failing to obtain a post–secondary/high school education at 33 years of age compared with those watching television for less than one hour a day, mediated by attention difficulties, frequent failure to complete homework and negative attitudes about school at 16 years of age (Johnson 2007). Studies relating accelerometer‐measured sedentary behaviour to cognitive function or school achievement or both indicated that high levels of sedentary behaviour at age seven years were associated with reduced verbal reasoning skills at age 11 (Aggio 2016), and that low levels of sedentary behaviour were associated with increased school achievement at age 10 to 11 years (Aadland 2017).

Reducing sedentary behaviour (TV and screen time, sitting time) might therefore improve cognitive function and school achievement in children and adolescents with obesity or overweight.

Multicomponent interventions

In this review, the term 'multicomponent interventions' refers to interventions that target at least two obesity‐related behaviours. Multicomponent lifestyle interventions may benefit cognitive function and school achievement in the general population, i.e. a study population that includes both children and adolescents of normal weight and those with obesity or overweight. For example, after the implementation of an uncontrolled intervention involving healthy nutrition, physical activity and using behaviour change techniques in a US primary/elementary school, an upward trend in reading performance scores was noted; these scores exceeded the national average by 10% after eight years (Nansel 2009). Another uncontrolled experimental study, which implemented a healthy diet and physical activity programme in a primary/elementary school, reported an increase in the numbers of children passing standardised tests in writing, reading and mathematics by 25%, 27% and 31%, respectively (Sibley 2008). A similar but controlled school‐based intervention promoting healthy eating and physical activity behaviour in children aged 11 to 14 years led to significant improvement in mathematics, listening and speaking scores after only five weeks compared with the control condition (standard classroom education) (Shilts 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

The current global trend in childhood obesity (NCD Risk Factor Collaboration 2017; WHO 2016) suggests that the prevalence of cognitive and educational problems among children is also likely to increase. Given the evidence of a link between low school achievement and economic disadvantage, this might have financial repercussions for future employability and income.

The beneficial effects of changes in diet, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and thinking patterns for prevention and treatment of childhood obesity are well established (Al‐Khudairy 2017; Colquitt 2016; Mead 2017; Waters 2011) and are reflected in clinical guidelines for the management of obesity (Ismail 2004; Lau 2007; NHMRC 2003; NICE 2013; SIGN 2010).

Animal models and human studies suggest that both obesity and obesity‐related lifestyle behaviours have the potential to impair cognitive function, learning, and school achievement (see How the intervention might work; Figure 1). What is less clear is the extent to which interventions which modify lifestyle or body fatness or both can improve cognitive function and learning/school achievement. We would expect that obesity prevention or treatment interventions benefit children with obesity differently from children with a healthy weight by mitigating cognitive deficits which are associated with having an excessive level of body fatness.

The first version of this review was published in March 2014 and included analysis of six trials published until May 2013 (Martin 2014). An update of the review was required to reflect the growing interest in this field.

Objectives

To assess whether lifestyle interventions (in the areas of diet, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and behavioural therapy) improve school achievement, cognitive function (e.g. executive functions) and/or future success in children and adolescents with obesity or overweight, compared with standard care, waiting‐list control, no treatment, or an attention placebo control group.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐randomised trials, and quasi‐randomised trials with or without cross‐over design, were eligible for inclusion. We included cross‐over trials when data from the first period were obtainable.

Types of participants

Children and adolescents with obesity or overweight aged three to 18 years attending preschool or school, and whose body weight status was determined using age‐ and gender‐specific BMI percentiles, BMI z‐scores, BMI standard deviation scores (SDSs), BMI cut‐off points or waist circumference. Classification of weight status needed to be based on a relevant national or international reference population for inclusion.

We did not exclude studies on the basis of location.

We excluded children with medical conditions known to affect weight status and academic achievement, such as Prader‐Willi syndrome and diagnosed intellectual disabilities.

Types of interventions

Studies were eligible for inclusion when the interventions aimed to prevent or reduce obesity. For inclusion, interventions had to be lifestyle interventions of any frequency and duration provided in any setting (e.g. clinics, schools, community centres) that comprised one or more of the following.

Interventions to increase physical activity

Dietary and nutritional interventions (excluding supplements)

Interventions to decrease sedentary behaviour, screen time and TV time

Psychological interventions to facilitate weight management

Interventions could target children or adolescents with or without the participation of family members.

We excluded studies which implemented a physical activity programme aiming to improve cognitive and academic outcomes without a stated intention to prevent or treat childhood obesity. Where any measure or proxy of adiposity was included as a covariate only, the study was not eligible for inclusion. We excluded pharmacological and surgical interventions because these are likely to be conducted in a less representative sample, thus limiting generalisability.

Eligible control interventions were waiting list, attention placebo control, no treatment, and standard practice.

Types of outcome measures

Primary and secondary outcomes did not serve as criteria for selection of studies based on title and abstract. Assessment of particular outcome measures was a criterion for inclusion in this review when we screened full texts. We restricted the review to particular outcomes because the same interventions were studied in the same populations for different purposes, for example change in BMI, BMI z‐scores, weight, health‐related quality of life, all‐cause mortality, morbidity, behaviour change (Al‐Khudairy 2017; Colquitt 2016; Mead 2017).

We extracted outcome data at the end of the intervention and at any other follow‐up time point.

Primary outcomes

-

School achievement (Morris 2011), recorded by appropriately‐trained investigators (e.g. teachers, researchers). We excluded participant‐ and parent‐reported data.

-

Average achievement of subjects taught at school.

Average across subjects taught at school over one academic year, for example, grade point average (GPA).

-

Achievement in a single subject taught at school.

Scores of subjects taught at school or standard achievement test scores for (a) mathematics, (b) reading or (c) language.

Validated tests for school achievement in mathematics, reading or language, for example, Woodcock‐Johnson Tests of Achievement III (McGrew 2011).

-

Special education classes.

Need for special education class.

Reduction of time allocated for special education class.

-

Cognitive function (Carroll 1993): measures of general cognitive ability or different cognitive domains (e.g. composite executive function, inhibition control, attention, memory) assessed using validated cognitive tests administered by appropriately‐trained investigators, such as qualified psychologists. We excluded participant‐reported and parent‐reported data.

Adverse outcomes: include, but are not limited to, reduced school attendance, musculoskeletal issues (e.g. activity‐related injury), and psychological issues (e.g. bullying, stigmatisation, depression, eating disorders) obtained from school records, medical records and self‐reports (for bullying and stigmatising events only). We included studies reporting adverse events only when measures of school achievement, cognitive function and/or future success were also reported.

Secondary outcomes

Future success: includes, but is not limited to, total years of schooling, high school completion, enrolment in higher education, rates of full‐time employment, monthly earnings, home ownership, no/reduced need of social services, obtained from administrative records and self‐reports.

Obesity indices: age‐ and gender‐specific BMI, BMI z‐scores and BMI‐SDSs when obtained from measured (not self‐reported) weight and height, measured waist circumference and measures of body fatness by dual‐energy x‐ray absorptiometry (DXA) and bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). We included studies reporting obesity indices only when measures of school achievement, cognitive function and/or future success were also reported. Inclusion of these data might enable the review authors to examine whether any changes in school performance, cognitive function and/or future success variables occur independently from changes in obesity (see How the intervention might work). It was not our intention to assess the effect of interventions for treatment of childhood obesity on adiposity or body weight status. This has recently been examined in three other Cochrane Reviews (Al‐Khudairy 2017; Colquitt 2016; Mead 2017).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We previously ran searches in 2012 and 2013. For this update, we searched 17 databases and two trials registers listed below in February 2017. Out of the 17 databases, 12 were searched by the Information Specialist of the Cochrane Developmental Psychosocial and Learning Problem Group. The first review author searched the remaining databases and the trials registers.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 1) in the Cochrane Library, which includes the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Specialised Register (searched 2 February 2017).

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to January Week 4 2017).

Ovid MEDLINE E‐PUB (searched 2 February 2017).

Ovid MEDLINE In‐P (searched 2 February 2017).

Embase Ovid (1974 to 2017 Week 05).

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to January Week 5 2017).

CINAHL Plus EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1937 to 3 February 2017).

ERIC EBSCOhost (Education Resources Information Center; 1966 to 3 February 2017).

SPORTDiscus EBSCOhost (1980 to 6 February 2017).

IBSS ProQuest (International Bibliography of Social Science; 1951 to 3 February 2017).

Conference Proceedings Citation Indexes (CPCI; 1990 to 2 February 2017).

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; 2017, Issue 2) part of the Cochrane Library (searched 2 February 2017)

Database of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE; 2015, Issue 2) part of the Cochrane Library (searched 3 February 2017).

Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews (DoPHER; eppi.ioe.ac.uk/webdatabases4/Intro.aspx?ID=9; searched 6 February 2017).

EPPI‐Centre Database of Health Promotion Research (Bibliomap; eppi.ioe.ac.uk/webdatabases/Intro.aspx?ID=7; searched 6 February 2017).

Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions (TRoPHI; eppi.ioe.ac.uk/webdatabases4/Intro.aspx?ID=12; searched 6 February 2017).

Dissertations and Theses Global ‐ ProQuest (searched 8 February 2017)

ISRCTN Registry (www.isrctn.com; searched 8 February 2017 )

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP: who.int/trialsearch; searched 8 February 2017).

Search strategies are reported in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched for eligible studies in the reference lists of included studies and in relevant reviews and guidelines.

We handsearched volumes 1 to 10 of The Journal of Human Capital, which is not included in the Cochrane Collaboration's Master List of Journals Being Searched (us.cochrane.org/master‐list) and is not comprehensively indexed by the databases we searched.

We contacted authors of included studies when outcome data were missing or when we required further details on methodology.

When necessary, we translated the title and abstract of non–English language studies. If the study appeared to be eligible for inclusion, we obtained the full article and a translation of the article for further assessment. We obtained translations for articles written in Chinese (Mandarin), Korean, Spanish, Turkish, Portuguese, and Persian.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We used the web‐based software platform Covidence to view, screen and select studies. AM, JNB and YL independently screened titles and abstracts and assessed their eligibility to identify potentially relevant trials. AM, YL and DHS assessed full reports for eligibility. We resolved different opinions about eligibility by discussion; when the review authors did not agree, the other review authors (JS and JJR) arbitrated. We recorded the reasons for excluding trials in the PRISMA diagram.

Data extraction and management

AM, YL and DHS extracted study characteristics using a predefined data extraction form, with AM and YL cross‐checking the extracts. The data extraction form included the following items:

General information: review author ID, title, published or unpublished, study authors, year of publication, country, contact address, source of study.

Methods (including 'Risk of bias' assessment): study design, randomisation methods, allocation concealment, blinding, handling of missing data, selective data reporting.

Population: age, gender, ethnicity, proportion of children with obesity or overweight; inclusion and exclusion criteria; number of participants recruited, included and followed (total and in comparison groups); diagnostic criteria of overweight or obesity; comparability of groups at baseline; comorbidities.

Intervention: type(s), frequency, mode of delivery, intensity of physical activity, methods and timing of comparison of intervention, setting, intervention and follow‐up duration, who delivered the intervention, attrition rates, assessment of compliance, details of comparison and control.

Outcome: assessor characteristics, baseline measures, measures immediately after intervention and at follow‐up, follow‐up time points, validity of measurement tools, definition of outcome (e.g. units, scales), primary outcomes, secondary outcomes.

Results: Where no suitable published data were available, AM contacted the study authors to obtain unpublished data for children and adolescents with overweight or obesity, which were a subgroup of the study sample. AM therefore extracted the result data for each outcome (mean, events, measures of variance, sample sizes), which were double‐checked by YL.

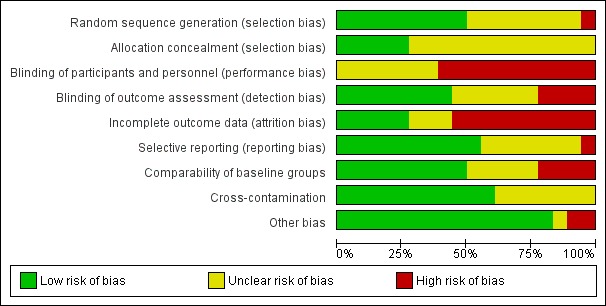

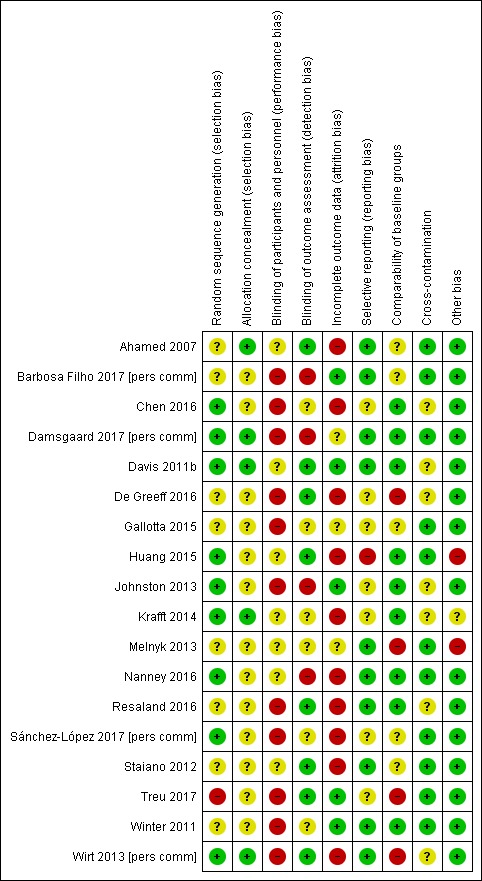

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

AM and DHS independently assessed the risks of bias in each trial, using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Chapter 8.5 in Higgins 2011). Findings were cross‐checked and discrepancies resolved through discussion. This included assessment of selection bias (random sequence allocation and allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), reporting bias (selective reporting) and other sources of bias. The review authors judged the risk of bias as 'high', 'low' or 'unclear', using the information provided.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated or extracted the mean change from baseline for intervention and comparison groups, and calculated the mean difference (MD) of change between the groups, when continuous data (e.g. numerical marks) were measured on the same scale. When similar outcomes were measured on different scales, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD). Where it was not possible to determine the change from baseline, we calculated MD or SMD using post‐intervention (endpoint) values.

There is no consensus regarding the most appropriate method to use in assessing cognitive ability and school achievement; different researchers tend to use different tools to measure the same outcome. Where the same outcome was assessed across different intervention types, we reported SMD for findings from single‐study and multiple‐study analyses to allow the comparison of intervention effects across intervention types. To ease interpretation of the effect size, we also reported the MD of effect sizes for single‐study outcomes.

We calculated all effect sizes so that positive effect sizes indicate better performance on cognitive function and school achievement outcomes in favour of the intervention group compared to the comparison group.

Included studies did not provide dichotomous or ordinal data. However, in Appendix 2, we describe how we intend to treat these types of data if available, as predefined in our protocol (Martin 2012).

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We scanned all included studies with clustered randomisation of participants for appropriate analysis of clustered data. Ignoring the proportion of total variance attributable to clustering can result in underpowered study designs and inflation of type I error rates, i.e. increased false‐positive results (Brown 2015). Therefore, for studies in which control of clustering was missing or insufficient at sample size calculation or analysis stage, and when individual participant data were not available, we approximately corrected the intervention effects of cluster‐RCTs. We reduced the size of each trial to its 'effective sample size' (Higgins 2011). We calculated the effective sample size in studies with continuous data by dividing the sample size by the design effect, which is [1 + (M‐1)* ICC], where M is the average cluster size and ICC is the intracluster correlation coefficient. When no ICC was obtainable, we used the ICC estimate of a similar study. In Appendix 3, we provide an overview of the ICCs used to estimate the effective sample size. Some trial authors provided recalculated ICCs for school or cognitive outcomes, or both, which were previously unpublished. We performed a sensitivity analysis to determine the robustness of conclusions from meta‐analyses that included cluster‐randomised trials (see Sensitivity analysis).

Cross‐over trials

We considered cross‐over trials as eligible for inclusion if participants were randomly assigned into the first period. We included only data from the first period before the cross‐over took place.

Multiple interventions per individual

We performed separate comparisons for studies that compared the effects of a single intervention (e.g. physical activity alone) versus a control condition and studies that compared a combination of any types and numbers of interventions of interest (e.g. physical activity with health behaviour education) versus a control condition.

We entered multiple intervention arms of the same study as separate interventions in the meta‐analysis. We divided the sample size of the control group by the number of intervention arms in the study to avoid overestimating the pooled effect size. We left the means and standard deviations unchanged, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Section 16.5.4. Higgins 2011).

Multiple time points

In separate meta‐analyses, we analysed data from studies that reported results at more than one time point with comparable data of other studies at similar time points.

Dealing with missing data

When possible, we recorded characteristics of, reasons for and quantities of missing data for all included studies. We contacted trial authors to obtain information on missing data, if not reported. In our analyses, we ignored data judged to be 'missing at random'. When possible, we imputed missing values in individual participant data, using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method. We performed sensitivity analyses to examine the effects of including imputed data in meta‐analyses (see Sensitivity analysis).

Included studies did not provide sufficient individual participant data to perform an individual participant data meta‐analysis. Should these become available from the study authors and prove to benefit the review, we will follow the guidance in Higgins 2011 (Chapter 18).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by comparing the similarities of included studies in terms of participants, interventions (type, duration, mode of delivery, setting) and outcomes. By comparing study design and risks of bias, we evaluated methodological heterogeneity. We assessed statistical heterogeneity across studies by visual inspection of the forest plot, and we used the Chi2 test with a significance level of P < 0.1 because of its low power in detecting heterogeneity when studies are low in sample size and numbers of events (section 9.5.2 Higgins 2011). Guided by the Cochrane Handbook (section 9.5.4 Higgins 2011), we estimated the between‐study variance in a random‐effects meta‐analysis (Tau2) in addition to the percentage of variability of intervention effect due to statistical heterogeneity ( I2 ). Variability greater than 50% may indicate moderate to substantial heterogeneity of intervention effects (section 9.5.2 Higgins 2011). Furthermore, we assessed the cause of heterogeneity by conducting subgroup and sensitivity analyses, as described below (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity; Sensitivity analysis, respectively).

Assessment of reporting biases

We had planned to assess reporting bias by using funnel plots but were unable to do so because of insufficient numbers of included studies (see Appendix 2 and Martin 2012).

Data synthesis

We used Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) (Review Manager 2014) for data entry and analysis. We combined outcome data from included studies in meta‐analyses when the outcome measure addressed the same measurement concept (e.g. mathematics achievement). Where separate data for children and adolescents with overweight and for children and adolescents with obesity were available, we included them separately in the meta‐analysis. This was done with the intention to explore a potential ‘dose‐response’ of the intervention effect relative to the weight category. Where the same study reported several outcome variables for one outcome measurement, we included the outcome variable that was comparable with outcomes reported by other included studies. For example, if reaction time and errors were both given for the cognitive outcome 'attention', then we reported only errors to ensure comparability with other studies which solely reported errors.

Health behaviour interventions have inherent heterogeneity due to intervention implementation and setting, so the true intervention effect is likely to vary between studies. We therefore pooled data using the random‐effects model and provided effect sizes of studies that were inappropriate to include in a meta‐analysis.

'Summary of findings' tables

We summarised outcomes relevant for decision‐making in health and education practice or policy or both (Balshem 2011) in 'Summary of findings' tables, using the GRADE approach. The recommended number of primary outcomes to be reported in the table is seven. We considered the following outcomes to be the most relevant:

Average achievement across subjects taught at school;

Mathematics achievement;

Reading achievement;

Additional educational support needs;

Composite executive functions;

Inhibition control;

Adverse events.

We used the GRADEprofiler Guideline Development Tool (GRADEpro GDT 2015) to generate the tables for which we imported data directly from RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014). These comparison‐specific tables provide details for each outcome concerning the assessment tools used, follow‐up range, timing of follow‐up, study design, number of studies, total sample sizes, effect estimates, and the quality of evidence. Two review authors (AM, DHS) assessed the quality of the evidence, resolving disagreements through discussion with a third review author (JNB).

We determined the quality of the evidence by assessing the methodological quality on outcome level, heterogeneity, the directness of evidence, the precision of evidence, and risk of publication bias. Where the evidence came from small studies, we assessed the extent of the limitation of 'unclear risk of bias on randomisation' on our confidence in the evidence by consulting the risk‐of‐bias item ‘comparability of groups at baseline’. We did not consider an unclear risk of selection bias as a serious limitation where we had rated the risk‐of‐bias item ‘comparability of groups at baseline’ at low risk of bias. A low risk of bias of known baseline characteristics may suggest adequate randomisation, so we have confidence in the evidence. Where we rated ‘comparability of groups at baseline’ at unclear or high risk of bias, we considered an 'unclear risk of bias on randomisation' as a serious limitation and so downgraded the quality of evidence to reflect our limited confidence in the evidence. However, we acknowledge that variables that were not tested for may cause imbalance between groups and that imbalances can occur by chance, despite adequate randomisation.

GRADE specifies four quality levels:

High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the effect estimate.

Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the effect estimate and may change the estimate.

Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the effect estimate and may change the estimate.

Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the effect estimate.

For ease of interpretation of the standardised effect sizes, we applied rules of thumb, where a standard deviation (SD) of 0.2 represents a small difference between groups, 0.5 represents a moderate difference, and 0.8 represents a large difference (section 12.6.2 in Higgins 2011). Where both change‐from‐baseline and endpoint data were available for the same outcome, we reported the evidence of highest quality. When the quality of evidence was the same for outcomes generated from endpoint and change‐from‐baseline data, we reported change‐from‐baseline outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' table.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses are principally intended to investigate sources of heterogeneity within a meta‐analysis in relation to factors that potentially impact outcomes. We identified several potentially influential participant and intervention characteristics for subgroup analyses (see Appendix 2). The low number of studies included for the same outcome did not allow us to perform meaningful subgroup analyses for all predefined sources of heterogeneity. However, we performed a subgroup analysis for body weight status (overweight versus obesity), where possible.

Sensitivity analysis

We investigated the influence of study characteristics on the robustness of the review results by conducting sensitivity analyses. We removed trials from the analysis when studies:

used different criteria or variations in the thresholds of criteria to define childhood obesity and overweight (e.g. clinical versus public health thresholds);

were judged at 'high risk of bias' in the characteristics of random sequence allocation, concealment of allocation, blinding and extent of dropouts;

were cluster‐RCTs or cross‐over trials;

provided a post‐intervention mean and standard deviations but where change‐from‐baseline data were missing.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

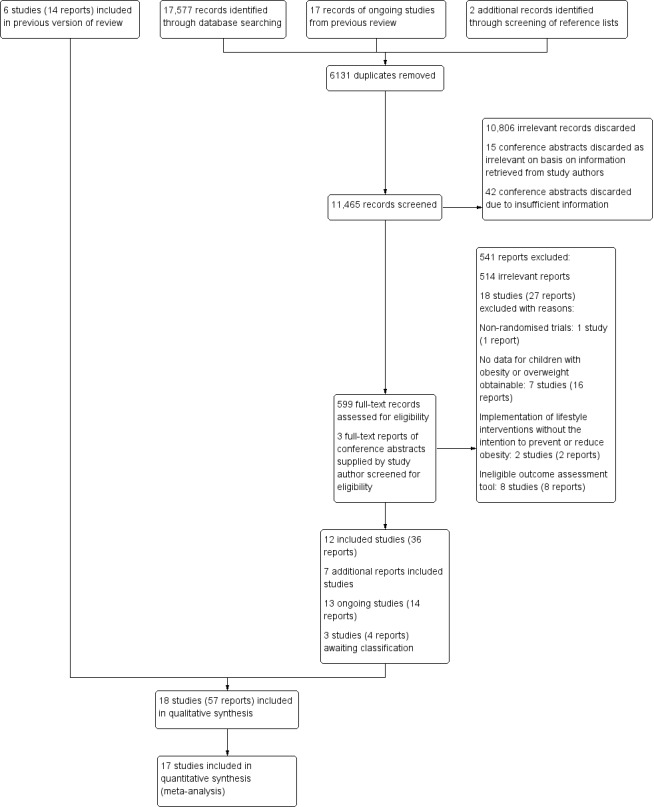

For the original review (Martin 2014), we screened 17,748 titles and abstracts, and excluded 17,219 records. We retrieved 529 full‐text reports, of which we included six studies (14 reports) in the review.

The electronic search for this review update yielded 17,577 records. We found two more records by screening the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews. We also carried forward 17 reports from the previous review that had been classified as ongoing or awaiting classification. Overall, our updated search yielded 17,596 records.

Having excluded 6131 duplicate records, we screened the remaining 11,465 on the basis of title and abstract, and discarded 10,806 as irrelevant.

For 60 records of conference papers, only abstracts were available. We contacted the authors of the conference abstracts for further information and followed up on non‐responders two weeks later. We received eighteen replies. Fifteen study authors stated that their study did not meet our inclusion criteria (Criteria for considering studies for this review), and we excluded these 15 records at title and abstract stage, along with 42 abstracts for which we were unable to make a decision due to insufficient information. Three authors supplied us with the full‐text report of their studies, which we screened and discarded at full‐text stage (see Excluded studies).

We retrieved 599 full‐text reports, of which 12 new studies (36 reports) met our inclusion criteria. We include 18 studies (57 reports) in total in this updated review (see Characteristics of included studies).

Three more studies (four reports) are awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). Thirteen trials (14 reports) are currently ongoing (see Ongoing studies). A flow chart of the search results is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

For 14 of the 18 included studies, outcome data for children and adolescents with obesity or overweight were not published separately from data for the total study population. We therefore contacted the study authors to obtain the unpublished data.

Study design and geographical location

We included five RCTs (Chen 2016; Davis 2011b; Huang 2015; Krafft 2014; Staiano 2012) and 13 cluster‐RCTs (Ahamed 2007; Barbosa Filho 2017 [pers comm]; Damsgaard 2017 [pers comm]; De Greeff 2016; Gallotta 2015; Johnston 2013; Melnyk 2013; Nanney 2016; Resaland 2016; Sánchez‐López 2017 [pers comm]; Treu 2017; Winter 2011; Wirt 2013 [pers comm]). Of the 18 studies, eight were conducted in the USA, two in Denmark, and one each in Canada, Brazil, Italy, Spain, Norway, The Netherlands, Germany and Taiwan.

Population characteristics

The numbers of participants randomly assigned ranged from 37 to 360, and the number of participants followed and analysed ranged from 28 to 349 (total N = 2384). Attrition rates varied from zero (Gallotta 2015) to 29% (Ahamed 2007; Nanney 2016).

Two studies were carried out in children attending preschool, with age ranges of three to five years (Winter 2011) and four to seven years (Sánchez‐López 2017 [pers comm]). Eleven studies were conducted in primary/elementary school‐aged children (six to 13 years) (Ahamed 2007; Damsgaard 2017 [pers comm]; Davis 2011b; De Greeff 2016; Gallotta 2015; Huang 2015; Johnston 2013; Krafft 2014; Resaland 2016; Treu 2017; Wirt 2013 [pers comm]). One study included adolescents in junior high/secondary school‐aged 12 to 15 years (Chen 2016) and another three studies included adolescents aged 14 to 18 years (Nanney 2016; Melnyk 2013; Staiano 2012). The study population in Barbosa Filho 2017 [pers comm] included adolescents from 11 to 18 years.

The overall proportions of girls with obesity or overweight were 64%, 57% and 53% in Sánchez‐López 2017 [pers comm], Staiano 2012 and Wirt 2013 [pers comm], respectively. These three studies did not report the gender distribution between intervention and comparison groups. There was a roughly equal gender distribution between intervention and comparison groups in four studies only (Barbosa Filho 2017 [pers comm]; Nanney 2016; Resaland 2016; Treu 2017). Five studies had a higher proportion of female participants in the intervention compared to the control group: Ahamed 2007 (48% versus 19%); Damsgaard 2017 [pers comm] (72% versus 59%); Gallotta 2015 (52% versus 36% ); Krafft 2014 (71% versus 58%); and Melnyk 2013 (54% versus 48%). A higher proportion of girls in the control group was evident in six studies: Chen 2016 (36% versus 52%); Davis 2011b (54% versus 62%); De Greeff 2016 (52% versus 69%); Huang 2015 (53% versus 59%); Johnston 2013 (38% versus 46%); and Winter 2011 (25% versus 37%).

Where data were obtainable, ethnic majorities in the study populations were African‐American (Davis 2011b; Krafft 2014; Staiano 2012), Hispanic (Johnston 2013; Melnyk 2013; Winter 2011), Asian (Chen 2016), South European (Sánchez‐López 2017 [pers comm]), South‐East European (Wirt 2013 [pers comm]), and North European (Damsgaard 2017 [pers comm]; Huang 2015; Resaland 2016). In Nanney 2016 and Treu 2017, most participants were of white European ethnic origin.

Of the 18 included studies, four reported that most of their participants were from low‐income families (Barbosa Filho 2017 [pers comm]; Chen 2016; Staiano 2012; Winter 2011).

Intervention characteristics

The interventions fell into three categories:

Physical activity only (eight studies);

Physical activity plus healthy lifestyle education (seven studies);

Dietary interventions including nutrition education (three studies).

Table 8 provides an overview of the specific intervention content. For a more detailed description of the interventions see Characteristics of included studies).

Table 1.

Intervention content of included studies

| STUDY | INTERVENTION CONTENT |

| Physical activity only interventions | |

| Chen 2016 | Group physical activity programme including multiple types of moderate‐intensity exercises performed 4 times/week for 40 minutes per session (5 minutes each for warm‐up and cool‐down, 30 minutes for the main exercise). The participants were free to choose one of the provided exercise types (e.g. fast walking, stair climbing, jumping rope, or aerobic dancing), with an emphasis on maintaining a moderate intensity of 60% to 70% of the maximal heart rate. Intervention was offered during the school day in the morning, during lunch break, or after school for 3 months |

| Davis 2011b | Aerobic group exercise for 40 minutes 5 times/week, over a mean total of 13 weeks. Five‐minute warm‐up phase consisted of brisk walking and static and dynamic stretching. Children were encouraged to maintain a heart rate > 150 beats/minute during running games, tag games, jump rope, modified basketball and football. The intervention involved no competition or skill enhancement and was delivered in an after‐school setting |

| De Greeff 2016 | Fit en Vaardig op school (Fit and academically proficient at school) involved physically active academic lessons which ran over 44 weeks in total over 2 school years with 3 lessons/week. The lessons had a duration of 20 – 30 minutes, with 10 – 15 minutes spent on solving mathematical problems and 10 – 15 minutes spent on language. During the lessons all children started with performing a basic exercise, such as jogging, hopping in place or marching. A specific exercise was performed when the children solved an academic task. The physical activities were aimed to be of moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity |

| Gallotta 2015 | The 2 intervention conditions had the same structure and took place in the school. They included 15 minutes of warm‐up, 30 minutes of moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activities, and 15 minutes of cool‐down and stretching. The traditional physical activity intervention consisted of continuous aerobic circuit training followed by a sub‐maximal shuttle run exercise. This intervention focused on the improvement of cardiovascular endurance by performing different types of gaits (e.g. fast walking, running, skipping) without any specific co‐ordinative request. The co‐ordinative physical activity intervention focused on the development of psychomotor competences and expertise in movement‐based problem‐solving through functional use of a common tool (e.g. basketball), and considering various tasks that involved decision‐making motor tasks and manipulative ball‐handling skills |

| Krafft 2014 | See Davis 2011b. The intervention duration was extended to 8 months. |

| Sánchez‐López 2017 [pers comm] | MOVI‐KIDS is a multidimensional intervention that consisted of a standardised extra‐curricular non‐competitive physical activity programme of 4½ hours/week; informative sessions to parents and teachers about how schoolchildren can become more active, and interventions in the playground (environmental changes: equipment, facilities, painting, etc.) aimed to promote physical activity during recess (MOVI‐Playground) |