Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the efficacy of Attachment-based Family Therapy (ABFT) compared to a Family Enhanced Non-Directive Supportive Therapy (FE-NST) for reducing adolescents’ suicide ideation and depressive symptoms.

Method:

A randomized controlled trial of 129 suicidal adolescents, between the ages of 12 to 18 (49% were African-American) were randomized to ABFT (n = 66) or FE-NST (n = 63) for 16 weeks of treatment. Assessments occurred at baseline, 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks. Trajectory of change and clinical recovery were calculated for suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms.

Results:

There was no significant between group difference in the rate of change in self-reported ideation Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Jr (SIQ-JR) (F(1,127) = 181, p=0.18). Similar results were found for depressive symptoms. However, adolescents receiving ABFT showed significant reduction in suicide ideation (t (127) = 12.61, p < .0001; effect size: d = 2.24). Adolescents receiving FE-NST experienced a similar significant reduction (t (127) = 10.88, p < .0001; effect size: d = 1.93). Response rates (i.e. 50% or more reduction in suicide ideation symptoms from baseline) at post-treatment were 69.1% for ABFT versus 62.3% for FE-NST.

Conclusion:

Contrary to expectations, ABFT did not perform better than FE-NST. Both treatments produced substantial reductions in suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms that were comparable to or better than those reported in other more intensive, multicomponent treatments. The equivalent outcomes may be attributed to common treatment elements, different active mechanisms, or regression to the mean. Future studies will explore long-term follow up, secondary outcomes, and potential moderators and mediators.

Keywords: adolescent, suicide, depression, attachment, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is the third leading cause of death in American adolescents, accounting for 4,600 deaths each year. In addition, nearly one million adolescents attempt suicide each year, resulting in roughly 500,000 emergency room admissions.1 Adolescent suicide results in high emotional costs for families and financial costs for the health care system. Using broad selection criteria, a recent review paper found 18 randomized control trials (RCTs) that examined psychosocial (with or without medication) treatments for adolescents with suicide ideation or behaviors.2 Only six of these treatments met criteria for being probably or possibly efficacious. Furthermore, nearly all of these treatments were supported by randomized trials that compared the treatment of interest to treatment as usual (TAU) in the community. These TAU comparison groups are highly variable in the number of sessions and nature of treatment received. As a result, interpretations of findings from studies using TAU as a comparison group are tenuous.3 Surprisingly, there have been few RCTs for suicidal adolescents that have compared two manualized, supervised, monitored treatments provided within the same research center. The current study tested the hypothesis that Attachment based family therapy (ABFT)4 would perform better than a manualized commonly used Nondirective Individual Supportive Therapy5 enhanced with a parent education program.

ABFT has been designated as a probably efficacious treatment for suicidal thoughts and behaviors as well as depression and depressive symptoms,2 and is listed on the National Registry of Evidence-based Program and Practices (NREPP) for suicidal thoughts and behaviors and depression. ABFT provides a manualized series of sequenced tasks, occurring in both individual and family sessions, that aim to identify and resolve attachment ruptures that have reduced adolescents’ trust in their parents (e.g., divorce, parental psychopathology, critical parenting). Working through these ruptures can increase the adolescent’s confidence in parents’ availability6 and increase the adolescent’s capacity for problem solving and ability to use the parent as a resource for regulating affect and managing suicidal thoughts and feelings. When adolescents view parents as sensitive, safe and available, they are more likely to turn to parents for support that can buffer against common triggers for depressive feelings and suicide ideation (e.g. grief and loss, bullying, school failure, romantic relationships, and family conflict).7 Studies have demonstrated that ABFT is more effective for this population than wait list control or TAU.8 ABFT has also been successfully disseminated to community settings.9,10

Non-directive supportive therapy (NST) has been used as an active control condition in treatments of adolescent and adult depression. In NST, the central goal is to augment the adolescent’s access to supportive adult relationships via their relationship with the therapist. Therapists implement NST by focusing on reflective listening, empathizing with the adolescent’s experiences of stress, and supporting the adolescent in articulating and exploring thoughts and feelings. In a study of adolescents with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) proved more effective than systemic behavior family therapy (SBFT) or NST in reducing depressive symptoms.5,11 However, Brent and colleagues (1997) reported equivalent reductions in suicidal symptoms and functional impairment in the NST, CBT and SBFT conditions. In another study, NST produced equivalent reductions in suicide ideation and depressed mood when compared to a directive skills-based protocol.11 The effectiveness of NST also extends to treatments of adult depression. In a meta-analysis of 31 studies on treatments for adult depression, NST was as effective as other active treatments,12 particularly when controlling for investigator allegiances. In this way, NST provides a rigorous test of the active ingredients of ABFT by controlling for a supportive therapeutic relationship and reflective listening as non-specific factors of therapy.

To test the superiority of ABFT against NST, we randomized suicidal adolescents and their families to the two treatment conditions. Many characteristics of this RCT were designed to control for common treatment elements in ABFT and NST. First, a five-session parent psychoeducation program was added to the NST condition to control for parent involvement in ABFT. Thus, we refer to the treatment used in the RCT as family enhanced-NST (FE-NST). Second, all patients received safety planning. Third, therapists implemented both ABFT and FE-NST to control for therapist effects. Fourth, with the exception of four cases, treatment was implemented by trained community therapists. Fifth, treatment dosage was controlled by delivering both treatments for 16 weeks with occasionally two weekly sessions to incorporate parent sessions. Sixth, severe and persistent suicidal ideation and moderate depression were used as inclusion criteria. These criteria establish a common clinical presentation and increased risk for suicide attempts.13,14 Finally, this study incorporated a diverse racial and ethnic sample, providing a test of the generalizability of treatment effects across race and social class. Suicide rates for minority youth have risen, 15 yet minorities remain under-represented in clinical trials.16

METHOD

Participants

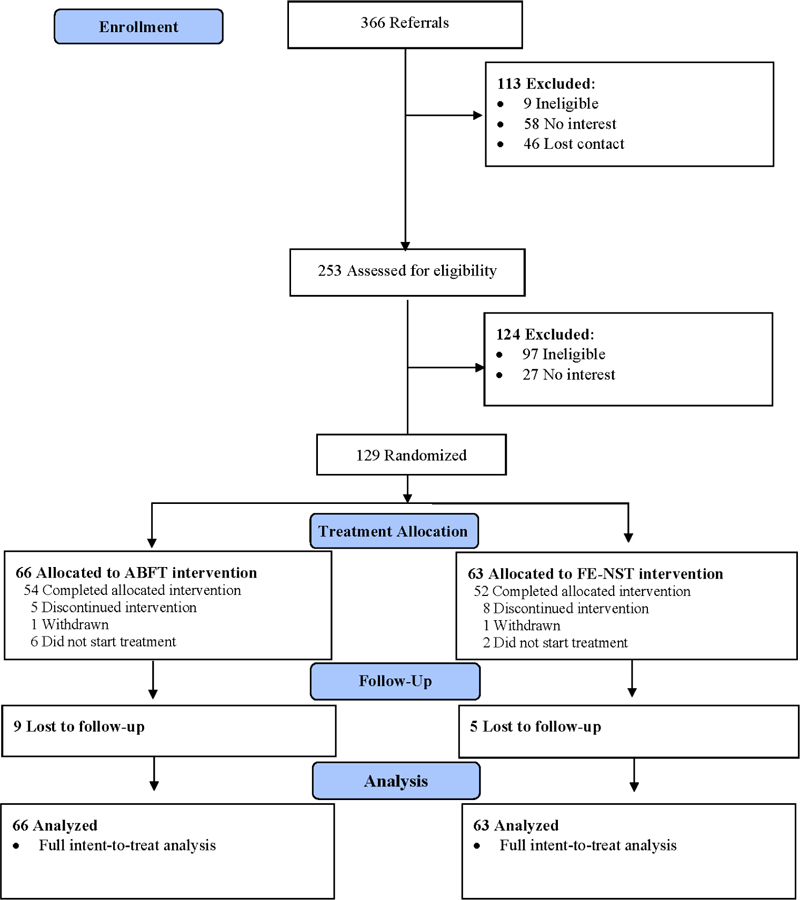

Participants were recruited from emergency departments (37.9%), inpatient psychiatric hospitals (6.9%), mental health agencies or primary care sites (20.9%), schools (10.8%), and community clinicians or self-referrals (23.5%) (Figure 1). Eligibility for the study included at least clinically significant levels of suicidal ideation (SIQ-JR ≥ 3117) and moderate levels of depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory II; BDI > 2017). Participants were screened using a multi-gate procedure over two pre-randomization time points. Participants were screened using the BDI-II and SIQ-JR, first over the phone and then at a face-to-face clinic visit usually within 72 hours of the initial screening. To be eligible, participants were required to meet inclusion criteria at both pre-treatment screens. At least one primary caregiver was required to participate in assessments and treatments.

Figure 1:

CONSORT Table

Note: ABFT = Attachment-based Family Therapy; FE-NST = Family Enhanced Non-Directive Supportive Therapy.

Exclusion criteria included: a) imminent risk of harm to self or others that could not be safely treated on an outpatient basis, b) psychotic features, c) severe cognitive impairment based on educational records, parent report and/or clinical impression, d) non-English speaking participating parent. Participants who began psychiatric medication within three weeks of the initial pre-treatment screening were also ineligible to participate. The protocol was approved by the IRBs at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Drexel University, and the City of Philadelphia. The study was monitored quarterly by a data safety and monitoring board. Participants were enrolled between May 1, 2012 and December 31, 2015 and provided written informed consent or assent (under 14 years of age).

Participants included 129 adolescents (81.9% female), ages 12–18 years old (M = 14.87, SD = 1.68). Sixty-four adolescents identified as African American (49.7%), 37 White (28.7%), 3 Asian (2.3%), 2 American Indian or Alaskan Native (1.6%), and 1 Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (0.8%). Ten adolescents identified as bi-racial or multi-racial (7.8%), and 12 identified as “other” (9.3%). The majority of the sample identified as non-Hispanic/Latino (84.5%) and 31% of adolescents identified as gay, lesbian or bisexual. Parents reported that 69% were single-headed households and 31% had incomes below the poverty line (Table 1). At baseline, the average score for suicidal ideation on the SIQ-JR was 49.89 (SD = 15.2), and the average score on the BDI was 30.5 (SD = 7.97) (Table 2). Forty-two percent of participants had made at least one suicide attempt in their lifetime, 25% had a history of psychiatric hospitalization, and 57.5% reported a history of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) as indicated by the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS18). At intake, 41.2% met criteria for major depressive disorder, 3.9% met criteria for dysthymia, and 46.93% met criteria for an anxiety disorder on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV18). At the time of intake, 27.1% of the participants were currently taking medication for depression and 9.3% were taking medication for other behavioral or emotional problems.

Table 1:

Frequencies for Sample Demographic Characteristics (N = 129)

| Variable | Total (n =129) | ABFT (n = 66) | NST (n = 63) | χ2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | ||

| Race | 3.09 | ||||||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 2 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 3.2 | |

| Asian | 3 | 2.3 | 2 | 3.0 | 1 | 1.6 | |

| White | 37 | 28.7 | 21 | 31.8 | 16 | 25.4 | |

| African American | 64 | 49.6 | 31 | 47.0 | 33 | 52.4 | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.6 | |

| Bi-Racial/Multiracial | 10 | 7.8 | 6 | 9.1 | 4 | 6.3 | |

| Other | 12 | 9.3 | 6 | 9.1 | 6 | 9.5 | |

| Hispanic | 20 | 15.5 | 11 | 16.7 | 9 | 14.3 | 0.14 |

| Relationship Status | 0.53 | ||||||

| Single | 89 | 69.0 | 45 | 68.2 | 44 | 69.8 | |

| In a relationship | 36 | 27.9 | 19 | 28.8 | 17 | 27.0 | |

| Physical Abuse | 23 | 17.8 | 9 | 13.6 | 14 | 22.2 | 1.74 |

| Sexual Abuse | 25 | 19.4 | 13 | 19.7 | 12 | 19.0 | 0.01 |

| Religion | 8.41 | ||||||

| Catholic | 28 | 21.7 | 13 | 19.7 | 15 | 23.8 | |

| Other Christian | 45 | 34.9 | 24 | 36.4 | 21 | 33.3 | |

| Jewish | 3 | 2.3 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 3.2 | |

| Muslim | 5 | 3.9 | 5 | 7.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Buddhist | 2 | 1.6 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.6 | |

| Hindu | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Atheist | 15 | 11.6 | 9 | 13.6 | 6 | 9.5 | |

| Other | 30 | 23.3 | 12 | 18.2 | 18 | 28.6 | |

| Gender | 0.01 | ||||||

| Female | 95 | 81.9 | 55 | 83.3 | 52 | 82.5 | |

| Male | 22 | 18.1 | 11 | 16.7 | 11 | 17.5 | |

| Age | 0.16 | ||||||

| Age ≤ 15 | 76 | 58.9 | 36 | 57.1 | 40 | 60.6 | |

| Sexual Orientation | 8.68* | ||||||

| Heterosexual | 88 | 68.2 | 38 | 57.6 | 50 | 79.4 | 7.06** |

| Lesbian/Gay | 10 | 7.8 | 8 | 12.1 | 2 | 3.2 | 3.61 |

| Bisexual | 22 | 17.1 | 13 | 19.7 | 9 | 14.3 | 0.67 |

| Questioning | 9 | 7.0 | 7 | 10.6 | 2 | 3.2 | 2.74 |

| Per Capita Ratio | |||||||

| Below Poverty Line | 40 | 31.3 | 21 | 32.3 | 19 | 30.2 | 0.69 |

| Prior Suicide Attempt (Yes/No) | 51 | 39.5 | 29 | 43.9 | 22 | 34.9 | 1.10 |

| History of NSSI (Yes/No) (n = 126) | 73 | 57.9 | 31 | 48.4 | 42 | 67.6 | 4.82* |

| Any Mood Disorder (n = 113) | 50 | 44.2 | 27 | 48.2 | 23 | 40.4 | 0.71 |

| Any Anxiety Disorder (n = 113) | 53 | 46.9 | 27 | 48.2 | 26 | 45.6 | 0.77 |

| Any Substance Disorder (n = 112) | 11 | 9.8 | 7 | 12.5 | 4 | 7.1 | 0.91 |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder (n = 113) | 11 | 9.8 | 3 | 5.4 | 8 | 14.0 | 2.42 |

Note: ABFT = Attachment-based Family Therapy; NST = Non-Directive Supportive Therapy.

p < .05

p < .01.

Table 2:

Means and Standard Deviation for Baseline Measure (N=129)

| Variable | Total (n = 129) | ABFT (n = 66) | NST (n = 63) | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| SIQ-Monthly | 49.89 (15.16) | 49.49 (14.66) | 50.27 (15.73) | −0.29 |

| BDI (Adol) | 30.54 (7.97) | 31.06 (7.68) | 29.99 (8.29) | −0.76 |

| Conflict | 10.89 (3.37) | 10.89 (3.24) | 10.89 (3.53) | 0.01 |

| Cohesion | 14.37 (3.37) | 14.30 (3.34) | 14.44 (3.43) | 0.23 |

Note: ABFT = Attachment-based Family Therapy; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory II; NST = Non-Directive Supportive Therapy; SIQ = Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire.

Procedures

After the baseline assessment, urn randomization assigned participants to 16 weeks of either ABFT or NST. Stratification variables included gender, past history of attempt, and endorsement of high levels of family conflict (score > 13 on the conflict sub-scale of the Self-Report of Family Functioning22). Outcomes assessments were administered at weeks 0 (baseline), 4, 8, 12 and 16 (post-treatment assessment). Follow-up assessments were completed at weeks 24, 32, 40 and 52, but are not included in this report. Assessment staff was blind to treatment condition.

Therapist and therapist training:

Over a period of four years, 14 therapists delivered the treatments. Eleven of the therapists were female. Five therapists had a master’s degree and nine had doctoral degrees. In order to control for potential therapist effects, the same therapists delivered both treatments. Therapists received training in both treatments by reading the manuals, attending a two to three day training workshop, and treating pilot cases or conducting co-therapy with experienced project therapists. Therapists then received weekly supervision from expert ABFT and NST supervisors. The two doctoral level ABFT supervisors had a primary allegiance to ABFT. Of the three doctoral level NST supervisors, two had a primary allegiance to CBT and one had an allegiance to couples and family therapy.

Adherence ratings:

To evaluate treatment fidelity and differentiation, raters used an adherence measure that included 22 items (17 items for tasks in ABFT and 7 items that were specific to FE-NST). Raters used a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = not present to 6 = very thorough and consistent to rate all items for all tapes regardless of condition. Following training, five raters blind to treatment condition scored a total of 290 sessions representing 20% of total sessions from 118 cases. Intraclass correlation coefficients revealed a mean coder reliability of α = 0.88. Data showed that ABFT and NST were delivered with high fidelity (e.g. treatment as intended) with 91% of the tapes coded showing adherence scores above 4 for ABFT scales (M=4.67, SD =6.04) and adherence scores above 4 for the NST scales (M=4.22, SD =4.40). In terms of differentiation, the seven non-specific treatment items from NST interventions were somewhat present in ABFT as expected, but less than ten percent of the ABFT were rated above 0 in the NST condition.

Treatments:

Informed by attachment theory, ABFT4 purports that depressive symptoms and suicidality can be precipitated, exacerbated or buffered against by the quality of family relationships. Family problems such as high conflict, parental abdication or over control, or more insidious traumas such as abandonment, neglect, or abuse, can rupture adolescents’ confidence in parents’ availability with accompanying feelings of anger and anxiety. As a result, these youth are less likely to turn to parents for help with life’s challenges. In individual sessions with the adolescent, the therapist helps the teen to understand how these ruptures fuel distress, contribute to self-destructive behavior and reduce their ability to use parents as a resource for managing suicidal thoughts and feelings. The therapist prepares the adolescent to discuss these ruptures with their parent. The therapist also works with the parent alone to better understand how their current stressors and own attachment history might inhibit them from providing more emotionally supportive parenting. Then, in conjoint sessions, adolescents begin to express their felt injustices and emotional disappointment, while the parent is coached to acknowledge and validate the adolescent’s feelings. This phase is designed to enact a corrective attachment experience. As trust and open communication improve, treatment shifts to promoting the adolescent’s autonomy in domains outside the family. Although ABFT is process- and trauma-focused, the manual offers structure and procedures to accomplish these treatment goals within a 16-week treatment protocol.

Family enhanced non-directive supportive therapy (FE-NST) is a modification of the individual, supportive relationship treatment manual. 19 Over 16 sessions, this therapy focuses on developing a supportive relationship between the adolescent and therapist. Specifically, the therapist engages with the adolescent by listening, empathizing, identifying feelings, attending to affect, offering support and validation, and providing summarizing statements that may bring more meaning to the adolescent’s experiences. These treatment factors, common to many psychotherapies20 are believed to counteract the patient’s feeling of thwarted belongingness, helplessness, and hopelessness by establishing a close relationship with the therapist. For this RCT, sessions with the adolescent were augmented with one conjoint parent-adolescent session to do safety planning and four parent education sessions without the adolescent. Parent education sessions focused on 1) suicide risk assessment, 2) understanding depression, 3) advocacy and resource development, and 4) problem solving.

Primary outcome measures

Suicidal Ideation:

The Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior (SIQ-JR Monthly21) is a 15-item measure assessing thoughts of suicide over the past month. Adolescents rate the frequency of suicidal thoughts on a 7-point scale. Sum scores can range from 0 to 90, with scores greater than 31 indicating clinical levels of ideation. Previous studies show that the SIQ-JR has high internal consistency (α = .93-.9622. Internal consistency in this sample was α = .86.

Depressive Symptoms:

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II17) has 21 self-reported items assessing severity of depressive symptoms. Responses for each item are scored on a 0 to 3 scale, with the sum of all items ranging from 0–63. Previous studies show that the BDI-II has high internal consistency (α = .91) and is positively correlated with other measures of depression. In this sample, the scale demonstrated internal consistency of α = .85.

Suicide Severity:

The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS 23) is an interview-based measure designed to create a topology of suicidal behavior and ideation. For this study, the C-SSRS was used to identify whether the adolescent had a lifetime suicide attempt history and/or a history of NSSI.

Family Conflict and Cohesion:

The Self-Report of Family Functioning (SRFF22 consists of 15 items measuring cohesion, conflict, and democratic family style. Previous studies show Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .63 to .91, with most in the .70 to .85 range. In this sample, internal consistency for the conflict scale and cohesion scales were α = .70 and .88, respectively.

Psychiatric Diagnoses:

The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) is a structured psychiatric diagnostic interview that evaluated more than 30 psychiatric diagnoses based on DSM-IV criteria. For the current study, the DISC modules for various anxiety disorders, mood disorders, oppositional defiant disorder, and substance abuse were administered to participating adolescents.

Data Analysis.

Tests of baseline differences in demographic and clinical characteristics were conducted using independent samples t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square or fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Prior to analysis, inspection of the two continuous outcome measures, SIQ-JR and BDI-II, identified significant deviations from normality. Box-Cox transformations indicated a square-root transformation corrected the positive skew for both the SIQ-JR and the BDI-II. Suicide attempts and NSSI (measured via the C-SSRS) were treated as binary (prior history versus no history).

Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) tested treatment differences in rates of change across the full sixteen weeks of treatment using the intent-to-treat sample. 24 For the SIQ-JR and the BDI, the main efficacy analysis modeled the rate of log-linear change from baseline to 16 weeks (end of active treatment). 25 All patients were included in the HLM corresponding to a full intent-to-treat analysis. Hierarchical generalized linear modeling (HGLM) was used to accommodate the binary outcome (i.e., suicide attempts), while accounting for clustering of repeated measures within each subject. 26 Effect size was measured using Cohen’s d for the continuous outcomes and odds ratios (OR) for the binary outcome. 27 The OR corresponded to, on-average, the number of times an event was more likely to occur for ABFT compared to FE-NST at each assessment. Nonparametric Wilcoxon Rank sum tests assessed the number of sessions attended. Chi-square analyses assessed treatment retention.28 The pattern-mixture model approach assessed whether missing data had a substantive influence on results. The Jacobson methodology29 was used to assess reliable change. Clinical significance was based on established thresholds for each measure. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4.

Statistical Power:

Using the method described by Diggle and colleague30s and Ahn and colleagues 31, power formulas for linear mixed models with repeated measures showed that the analysis of SIQ-JR was well-powered with a targeted sample size of 110 patients (55 completers per group). A priori, using an alpha-level at .05 based on a 2-tailed test and assuming a within correlation of 0.5 with four post-baseline assessments, we had power of 91.2% and 80.0% to detect a between-intervention effect size of .50 and .42, respectively. Additionally, the study had over 80% power to detect a difference in proportion of suicide attempts (yes versus no) of 1/6 or more.

RESULTS

Treatment Retention

There was no significant difference between the number of sessions attended by ABFT participants (M = 14.34, SD = 7.58) and FE-NST patients (M = 12.67, SD = 5.74; t(127) = −1.43, p = 0.16). There was no significant difference between the number of weeks attended by patients in the two treatments (ABFT = 9.68, SD=4.72; FE-NST = 9.43, SD=4.20) t (127) = −0.32, p = 0.75). Drop-out rates were not significantly different between treatment groups, with 18.2% attrition in ABFT compared to 17.5% for FE-NST, χ2 (1, N = 129) = 0.02, p = 0.92 (Figure 1).

Suicide Ideation

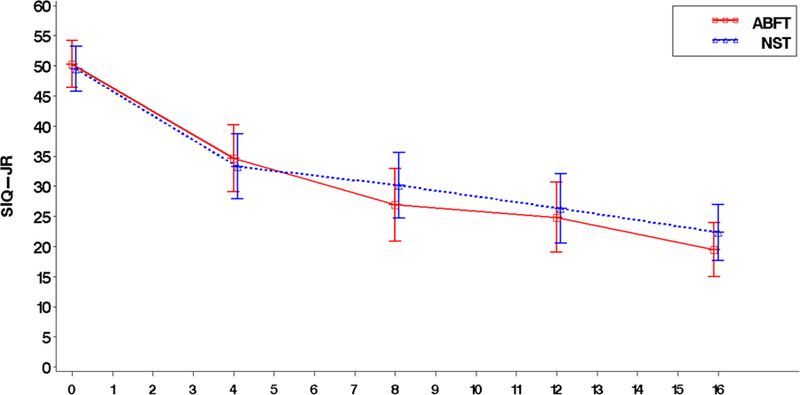

There was no significant between-group difference in the rate of change in self-reported ideation (SIQ-JR) (F (1, 127) = 1.81, p = 0.18) (Figure 2). The estimated total change from baseline to end of treatment (week 16) was −31.55 (se = 2.50) for ABFT and −27.42 (se = 2.52) for FE-NST. On average, ABFT participants experienced a significant reduction in suicidal ideation (t(127) = 12.61, p < .0001) with an effect size of d = 2.24. Similarly, participants in the FE-NST experienced a significant reduction in suicidal ideation (t(127) = 10.88, p < .0001) with an effect size of d = 1.93.

Figure 2:

Suicide Ideation by Treatment Condition at Weeks 0, 4, 8, 12 and 16

Note: ABFT = Attachment-based Family Therapy; NST = Non-Directive Supportive Therapy; SID-JR = Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Jr

Remission (below clinical cut off) rates in suicide ideation (i.e., SIQ-JR < 12) were 14.3% for ABFT versus 12.1% for FE-NST at 4 weeks, 25.0% for ABFT versus 11.5% for FE-NST at 8 weeks, 24.5% for ABFT versus 26.5% for FE-NST at 12 weeks, and 32.7% for ABFT versus 24.5% for FE-NST at post-treatment (16 weeks). There were no significant between-treatment differences in remission rates over the 16 weeks of treatment.

Response rates (i.e. 50% or more reduction in SIQ-JR from baseline) were 32.1% for ABFT versus 32.8% for FE-NST at 4 weeks, 51.9% for ABFT versus 36.5% for FE-NST at 8 weeks, were 58.5% for ABFT versus 51.0% for FE-NST at 12 weeks, and 69.1% for ABFT versus 62.3% for FE-NST at post-treatment (16 weeks). The differences in treatment response rates between the two conditions were not significant. Reliable change in SIQ-JR required difference scores of 23.02 or more. At post treatment, the reliable change was 56.6% for ABFT versus 49.2% for FE-NST at post-treatment (week 16), with no significant differences between the two conditions.

Depressive Symptoms

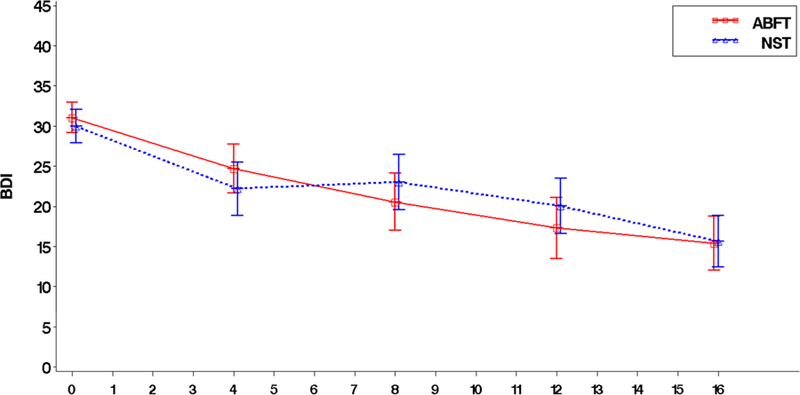

There was no difference between the two treatment conditions in the rate of change in depression (BDI-II) over the course of treatment (F (1, 127) = 0.11, p = 0.74) (Figure 3). The estimated total change from baseline to end of treatment was −5.40 (se = 0.50) for ABFT and −4.87 (se = 0.50) for FE-NST on the BDI-II. Participants within the ABFT group experienced significant reduction in BDI-II (t (127) = 10.72, p < .0001) with an effect size of d = 1.90. Similarly, FE-NST participants experienced a significant reduction in BDI-II (t (127) = 9.68, p < .0001) with an effect size of d = 1.72.

Figure 3:

Depressive Symptoms by at Weeks 0, 4, 8, 12, and 16

Note: ABFT = Attachment-based Family Therapy; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory II; NST = Non-Directive Supportive Therapy.

Remission rates in depressive symptoms (i.e., BDI-II < 9) 32 were 7.1% for ABFT versus 15.5% for FE-NST at week 4, 19.2% for ABFT versus 11.8% for FE-NST at week 8, 35.9% for ABFT versus 18.4% for FE-NST at week 12, and 40.0% for ABFT versus 34.0% for FE-NST at post-treatment (week 16). A significant between-treatment difference in response rates per depressive symptoms was seen at 12 weeks favoring ABFT over FE-NST (OR = 2.88, 95% CI: 1.10–7.60; χ2(1) = 4.60, p = 0.03). Reliable change in BDI-II required difference scores of 12.10 or more. These rates were 70.9% for ABFT versus 56.6% for FE-NST at post-treatment (week 16). There were no significantly different reliable change scores between treatment conditions across the treatment course.

Suicide Attempts

During the course of treatment, six of the 129 adolescents reported making a suicide attempt during the treatment phase. Of those six, two were enrolled in ABFT (3.0%) and four were enrolled in FE-NST (6.4%), with no significant difference between the groups (χ2(1) = 0.80, p = 0.37). Similar to other suicide attempter studies, we also looked at patients who came to the study after a recent suicide attempt and hospitalization (N = 51). Of these recent attempters, two were from ABFT (6.9%) and two from FE-NST (9.1%) with no significant difference between groups (χ2(1) = 0.08, p = 0.77).

Discussion

This is the first RCT comparing ABFT to an active, rigorously controlled comparison therapy for treating suicide ideation and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Although adolescents in ABFT and FE-NST showed substantial reductions in suicide ideation and depressive symptoms, there were no differences in symptom reduction between the two treatment conditions. On average, suicide ideation dropped 24 points across both treatments allowing many adolescents to move into a normative range below 12 on the SIQ (35% ABFT, 28% FE-NST), with an overall clinical response rate of 69% for ABFT and 62% for FE-NST patients. Rates of suicide attempts following admission to the trial were low even among adolescents that had made a recent suicide attempt. These findings might reflect the efficacy of these two relatively brief, low dose, outpatient treatments for adolescents referred for serious suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Alternatively, because depression and suicide ideation are time sensitive symptoms. these outcomes could be influenced by regression to the mean over the 16 weeks of treatment.

Comparisons with other treatment studies are complicated by heterogeneity in sample demographics, inclusion criteria, and outcome measures, as well as treatment elements and duration. Still, some comparison on suicide attempts and attrition is informative. Of those patients starting treatment soon after a suicide attempt (n = 51), 6.9% of ABFT participants and 9.1% of those in FE-NST made an attempt during the treatment phase. This compares favorably to a meta-analysis that failed to find significant reductions in suicide attempts when active interventions were compared to TAU33,34. In the treatment study of adolescent suicide attempters (TASA), 35 consisting of medication+CBT+family, 12% of participants made an attempt within 6 months36. In another study, 25% of participants in a skills training condition and 12% in an NST condition, reattempted suicide during the treatment phase. In terms of retention, attrition from ABFT was 18.2% and 17.5% in FE-NST, comparable to similar studies. 11,35 In terms of treatment dose, ABFT was delivered as a single modality by a community therapist, generally once a week (M = 14 sessions). This contrasts with many other studies that use a multicomponent treatment protocol (e.g., individual and group therapy plus medication), multiple contact hours a week, and delivered by whole teams of expert therapists. Thus, the structure of both ABFT and NST may fit well within typical outpatient treatment settings. Future comparisons across studies would be strengthened if they shared common measurement tools and agreed upon definitions of remission, response, clinical significance, adequate dose and attrition.

In addition to treatment dose and length of treatment which was controlled in the two conditions, other common factors may account for the equivalent efficacy of ABFT and FE- NST. First, all families entered treatment at moments of high crisis and were met with supportive staff and therapists who offered immediate access to treatment, 24-hour available crisis hotline, weekly check-in phone calls, home visits as needed, and assistance with social services, school, or medication consults. These treatment features, along with special attention to retention should be considered essential and best practice for this population. The responsiveness of the program alone may have accounted for some of the treatment response and low rates of suicide attempts in the study. 37 Second, the therapist crossover design and high treatment adherence provided consistent empathy, support and treatment fidelity, and controlled for the possible confound of treatment allegiance, all of which have been associated with treatment outcome11 Third, both treatments shared many common elements, including family safety planning, parent involvement, and parent psycho education, as well as support, validation, and empathy in individual sessions with adolescents and parent(s) alone. 20 Fourth, while investigators usually view NST as a control treatment, it has proven equivalent to CBT in a meta-analysis of treatment studies for adults with depression after controlling for treatment allegiance. 12

Treatment outcomes may also have resulted from mechanisms specific to ABFT and FE-NST. 38 In ABFT, the primary aim is to improve trust and communication in the parent-adolescent dyad. These improvements are hypothesized to reduce family conflict and emotional chaos and increase adolescent’s reliance on parents as a safety net. Addressing these attachment ruptures may lead to more coherent (i.e., secure) attachment schemas and a variety of mental health benefits (e.g., improved self-worth, better emotion regulation). Possibly ABFT would be fortified by integrating more specific cognitive and emotional skills training (e.g., parent or adolescent psychoeducation, CBT, or dialectical behavioral therapy techniques). Thus, building a more multi-component ABFT treatment program might be worthy of investigation.

Alternatively, NST focuses on the therapist establishing a supportive relationship with the adolescent through reflective and empathic listening. This clinical process is similar to Mentalization Based Therapy (MBT) which focuses on reflective conversations that are thought to change the adolescent’s self-understanding, sense of agency and self-regulatory capacities. 39 In NST the adolescent’s relationship with the therapist is primary and was evident in higher ratings of the therapeutic alliance in the NST than in the ABFT condition40. These findings suggest that ABFT might be potentiated by increasing the amount of individual time devoted to the adolescent and adding individual skill training or medication elements to the treatment protocol. Again, building a more multi-component treatment program might be worthy of investigation.

The failure to confirm the superiority of ABFT compare to FE-NST is consistent with many RCTs of two active treatments that fail to demonstrate the superiority of a specific treatment41,42. Yet, there are several notable limitations to the current findings. First, although nearly 70% of patients reported clinically significant change, only 40% obtained remission (non-clinical symptoms) by the end of 16 weeks. Some patients may have needed a longer treatment, additional treatments, or another type of treatment. Second, both treatments were delivered in a highly regarded children’s hospital and university, which engenders the kind of institutional alliance that has often been associated with better outcomes. 43 Testing these treatments in real-world, clinical settings may be needed to evaluate their true clinical value. ABFT has shown some promise in this area.9,10 Future examination of long-term outcomes, treatment moderators and mediators, and relapse might help understand what kind of patients responded best to which treatment.

Clinical Vignette.

General information: Sophia is a 16-year old white female currently in the 10th grade. Sophia has never met her father. When Lisa, Sophia’s mother, lost her job, they moved in with the maternal grandmother. Sophia was 10 years old. Lisa become depressed and through a new boyfriend became addicted to oxycodone. When Sophia was 13, Lisa moved in with her boyfriend and left Sophia with her grandmother. Mother sporadically visited but eventually got arrested and went to a rehab program for 9 months. Six months after discharge Lisa was stable, and moved back into the home with grandmother and Sophia. In the mother’s absence, Sophia began to act out, experimenting with drugs and risky sexual behavior. When a friend’s mother discovered this, it lead to a referral to our therapy program. At Sophia’s intake, it became clear that her drug use and sexual behaviors were her best attempt at coping with her depression and suicidal impulses. Wanting to resume parenting of her daughter, the mother brought Sophia to the first session, which infuriated Sophia. After some history gathering and assessment of the depression, the therapist focused on the mother-daughter relationship. “So Sophia, when you feel so bad, like you want to kill yourself, why don’t you turn to your mother for help?” Sophia was reluctant to talk. Lisa resentfully said that Sophia thought she was all grown up and independent. Sophia said, “She does her thing and I do mine. I don’t need her anymore.” Because it was the first session, the therapist did not explore this in depth, but empathically remarked that the distance between them was apparent and tragic. Commenting how disjointing this must feel, Lisa began to cry and Sophia looked on scornfully. The therapist said that maybe if they could work through some of these past hurts, they could either be close again or at least not carry around such guilt (mother) and resentment (daughter). The family agreed to consider this attachment focused treatment plan.

In a session alone with the Sophia, the therapist explored her depression, suicidal feelings and risky sexual behavior. The goal was not to change it (yet) but to help Sophia acknowledge for herself how miserable she felt; to make this her problem rather than everyone else’s. In another session, the discussion focused on her mother. With a gentle directive approach, Sophia began to broaden her attachment narrative. Rather than just feel rage at her “selfish mother,” Sophia allowed herself to feel the shame and disappointment of abandonment. She began to understand how feeling worthless and rejected by her mother allowed her to let boys to take advantage of her. When the timing was right in the third session alone, the therapist proposed that expressing her anger directly to her mother might help rid her of these ghosts of self-hatred. Sophia reluctantly agreed, and the next session the therapist helped prepare Sophia for this conversation. Simultaneously, the therapist was having individual sessions with the mother. Several sessions explored her current stressors related to getting her life back on track. One session focused on her relationship with her parents. The loss of her father when she was 11 devastated her, and her own mother’s grief and withdrawal felt rejecting. Helping Lisa remember and feel her own experience of abandonment gave the therapist the opportunity to help the mother more empathically understand how Sophia might have felt when she left. The mother, preoccupied with her own recovery, never really stopped to consider the impact her drug abuse had on her daughter. This moment of empathic sensitivity, of reflective functioning, motivated the mother to let the therapist teach her some different, more emotion focused, parenting skills.

About week eight, the therapist brought the mother and daughter back together. Sophia expressed more directly, and in a more regulated manner, her hurt and feelings of abandonment. Lisa, rather than being defensive, empathically listened and encouraged Sophia to share these feelings and memories with her. When the timing was right, the mother apologized for her actions. Sophia listened but did not feel moved to forgive her. Lisa had to accept that. However, when leaving the session, Sophia did allow her mother to put her arm around her shoulder. Two more sessions focused on helping the family discuss these past traumas and injustice. The grandmother participated in one of these sessions. As the tension at home dissipated, Sophia’s depression lessened. Problems persisted with weekend drinking and the mother had to increase her monitoring and limit setting. Sophia resented this at first. The therapist helped frame this as the mother not wanting to abandon Sophia again by ignoring these problems. Sophia became more receptive when limits were viewed as protection rather than punishment. At the end of the short-term treatment (16 weeks), Sophia’s depression and suicide ideation were out of clinical range. The therapist then referred Sophia to a DBT therapist to help her develop more effective emotion regulation sills.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grant 5R01MH091059–03 (Dr. Diamond and Dr. Kobak, Co-PIs). The trial was prospectively registered on the U.S. National Institutes of Health clinicaltrials.gov registry: NCT01537419.

Clinical trial registration information– Attachment Based Family Therapy for Suicidal Adolescence. http://clinicaltrials.gov; NCT01537419.

Dr. Gallop served as the statistical expert for this research.

The authors thank the dedicated staff who worked tirelessly on this project, especially Linda Boamah-Wiafe, BA, of the University of Connecticut, Margot Adams, MSW, of Stanford University, Tamar Kodish, BA, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and Annie Shearer, BA, of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. They also sincerely thank all of the study participants and the collaborating referral providers, including the network of primary care clinicians, patients, and families from the Pediatric Research Consortium (PeRC) at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Disclosure: Drs. Diamond and Levy have received funding from the National Institute of Mental Health. They have received royalties from Attachment-Based Family Therapy (2014) book sales and honoraria for ABFT trainings and supervision. Drs. Kobak, Ewing, Herres, Russon, and Gallop have received funding from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Contributor Information

Guy S. Diamond, Center for Family Intervention Science, Drexel University Philadelphia, PA..

R. Rogers Kobak, University of Delaware, Newark..

E. Stephanie Krauthamer Ewing, Center for Family Intervention Science, Drexel University Philadelphia, PA..

Suzanne A. Levy, Center for Family Intervention Science, Drexel University Philadelphia, PA..

Joanna L. Herres, The College of New Jersey, Ewing Township..

Jody M. Russon, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg..

Robert J. Gallop, Applied Statistics Program, West Chester University, PA..

References

- 1.Anderson RN. Deaths: leading causes for 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2002;50(16):1–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glenn CR, Franklin JC, Nock MK. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2015;44(1):1–29. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.945211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spirito A, Stanton C, Donaldson D, Boergers J. Treatment-as-usual for adolescent suicide attempters: implications for the choice of comparison groups in psychotherapy research. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 2002;31(1):41–47. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diamond GS, Diamond GM, Levy SA. PsycNET 2014.

- 5.Brent DA, Holder D, Kolko D, et al. A clinical psychotherapy trial for adolescent depression comparing cognitive, family, and supportive therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54(9):877–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zisk A, Abbott CH, Ewing SK, Diamond GS, Kobak R. The Suicide Narrative Interview: adolescents’ attachment expectancies and symptom severity in a clinical sample. Attachment & Human Development 2017;19(5):447–462. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2016.1269234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobak R, Zajac K, Herres J, Krauthamer Ewing ES. Attachment based treatments for adolescents: the secure cycle as a framework for assessment, treatment and evaluation. Attachment & Human Development 2015;17(2):220–239. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2015.1006388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diamond GS, Wintersteen MB, Brown GK, et al. Attachment-Based Family Therapy for Adolescents with Suicidal Ideation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2010;49(2):122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Israel P, Diamond GS. Feasibility of Attachment Based Family Therapy for depressed clinic-referred Norwegian adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2013;18(3):334–350. doi: 10.1177/1359104512455811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santens T, Devacht I, Dewulf S, Hermans G, Bosmans G. Attachment‐Based Family Therapy Between Magritte and Poirot: Dissemination Dreams, Challenges, and Solutions in Belgium. Wagner I, Levy SA, Diamond GS, eds. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy 2016;37(2):240–250. doi: 10.1002/anzf.1154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donaldson D, Spirito A, Esposito-Smythers C. Treatment for adolescents following a suicide attempt: results of a pilot trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2005;44(2):113–120. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200502000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuijpers P, Driessen E, Hollon SD, van Oppen P, Barth J, Andersson G. The efficacy of non-directive supportive therapy for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 2012;32(4):280–291. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prinstein MJ, Nock MK, Simon V, Aikins JW, Cheah CSL, Spirito A. Longitudinal trajectories and predictors of adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts following inpatient hospitalization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2008;76(1):92–103. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spirito A, Esposito-Smythers C. Attempted and completed suicide in adolescence. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2006;2(1):237–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joe S, Baser RE, Breeden G, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts among blacks in the United States. Jama 2006;296(17):2112–2123. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miranda J, Nakamura R, Bernal G. Including ethnic minorities in mental health intervention research: a practical approach to a long-standing problem. Cult Med Psychiatry 2003;27(4):467–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment 1996;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2000;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brent DA, Kolko DJ. Supportive Relationship Treatment Manual Pittsburgh, PA; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sprenkle DH, Davis SD, Lebow J. Common Factors in Couple and Family Therapy Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynolds WM, Mazza JJ. Assessment of suicidal ideation in inner-city children and young adolescents: reliability and validity of the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-JR 1999.

- 22.Reynolds WM, Mazza JJ. Reliability and Validity of the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale with Young Adolescents. Journal of School Psychology 1998;36(3):295–312. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(98)00010-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168(12):1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallop R, Tasca GA. Multilevel modeling of longitudinal data for psychotherapy researchers: II. The complexities. Psychother Res 2009;19(4–5):438–452. doi: 10.1080/10503300902849475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallop RJ, Dimidjian S, Atkins DC, Muggeo V. Quantifying treatment effects when flexibly modeling individual change in a nonlinear mixed effects model. J Data Sci 2011.

- 26.Tate R Interpreting Hierarchical Linear and Hierarchical Generalized Linear Models with Slopes as Outcomes. The Journal of Experimental Education 2004;73(1):71–95. doi: 10.2307/20157385?ref=search-gateway:d9bb2b1621c313ba4664a6e3c41b80f9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGough JJ, Faraone SV. Estimating the size of treatment effects: moving beyond p values. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2009;6(10):21–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onchiri S Conceptual model on application of chi-square test in education and social sciences. Educational Research and Reviews 2013. doi: 10.5897/ERR11.0305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobson NS, Roberts LJ, Berns SB, McGlinchey JB. Methods for defining and determining the clinical significance of treatment effects: description, application, and alternatives. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1999;67(3):300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diggle P, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: : Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahn C, Overall JE, in Biomedicine, 2001. Sample size and power calculations in repeated measurement analysis. Elsevier 2001;64(2):121–124. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2607(00)00095-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riedel M, Möller H-J, Obermeier M, et al. Response and remission criteria in major depression - A validation of current practice. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2010;44(15):1063–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D, Moran P, Asarnow JR. Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2015;54(2):97–107.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asarnow JR, Hughes JL, Babeva KN, Sugar CA. Cognitive-Behavioral Family Treatment for Suicide Attempt Prevention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2017;56(6):506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vitiello B, Brent DA, Greenhill LL, et al. Depressive symptoms and clinical status during the Treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters (TASA) Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2009;48(10):997–1004. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5db66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brent DA. The treatment of SSRI-resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA): in search of the best next step. Depress Anxiety 2009;26(10):871–874. doi: 10.1002/da.20617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brent DA, McMakin DL, Kennard BD, Goldstein TR, Mayes TL, Douaihy AB. Protecting adolescents from self-harm: a critical review of intervention studies. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2013;52(12):1260–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeRubeis RJ. A Conceptual and Methodological Analysis of the Nonspecifics Argument. Clin Psychol (New York) 2005;12(2):174–183. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/bpi022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen JG, Association AP. Restoring Mentalizing in Attachment Relationships : Treating Trauma with Plain Old Therapy Arlington, VA: : American Psychiatric Pub., Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ibrahim M, Jin B, Russon J, Diamond G, Kobak R. Predicting Alliance for Depressed and Suicidal Adolescents: The Role of Perceived Attachment to Mothers. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health 2018;3(1):42–56. doi: 10.1080/23794925.2018.1423893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goodyer IM, Reynolds S, Barrett B, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy and short-term psychoanalytical psychotherapy versus a brief psychosocial intervention in adolescents with unipolar major depressive disorder (IMPACT): a multicentre, pragmatic, observer-blind, randomised controlled superiority trial. The Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4(2):109–119. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30378-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wampold BE, Minami T, Baskin TW, Callen Tierney S. A meta-(re)analysis of the effects of cognitive therapy versus “other therapies” for depression. J Affect Disord 2002;68(2–3):159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, Symonds D, Horvath AO. How central is the alliance in psychotherapy? A multilevel longitudinal meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology 2012;59(1):10–17. doi: 10.1037/a0025749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]