Abstract

Background

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) is a common cause of morbidity and mortality due to cardiovascular disease in the general population. Although numerous treatments have been adopted for patients at different disease stages, no option other than amputation is available for patients presenting with critical limb ischaemia (CLI) unsuitable for rescue or reconstructive intervention. In this regard, prostanoids have been proposed as a therapeutic alternative, with the aim of increasing blood supply to the limb with occluded arteries through their vasodilatory, antithrombotic, and anti‐inflammatory effects. This is an update of a review first published in 2010.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of prostanoids in patients with CLI unsuitable for rescue or reconstructive intervention.

Search methods

For this update, the Cochrane Vascular Information Specialist searched the Specialised Register (January 2017) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 1). In addition, we searched trials registries (January 2017) and contacted pharmaceutical manufacturers, in our efforts to identify unpublished data and ongoing trials.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials describing the efficacy and safety of prostanoids compared with placebo or other pharmacological control treatments for patients presenting with CLI without chance of rescue or reconstructive intervention.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials, assessed trials for eligibility and methodological quality, and extracted data. We resolved disagreements by consensus or by consultation with a third review author.

Main results

For this update, 15 additional studies fulfilled selection criteria. We included in this review 33 randomised controlled trials with 4477 participants; 21 compared different prostanoids versus placebo, seven compared prostanoids versus other agents, and five conducted head‐to‐head comparisons using two different prostanoids.

We found low‐quality evidence that suggests no clear difference in the incidence of cardiovascular mortality between patients receiving prostanoids and those given placebo (risk ratio (RR) 0.81, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.41 to 1.58). We found high‐quality evidence showing that prostanoids have no effect on the incidence of total amputations when compared with placebo (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.09). Adverse events were more frequent with prostanoids than with placebo (RR 2.11, 95% CI 1.79 to 2.50; moderate‐quality evidence). The most commonly reported adverse events were headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, flushing, and hypotension. We found moderate‐quality evidence showing that prostanoids reduced rest‐pain (RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.59) and promoted ulcer healing (RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.48) when compared with placebo, although these small beneficial effects were diluted when we performed a sensitivity analysis that excluded studies at high risk of bias. Additionally, we found evidence of low to very low quality suggesting the effects of prostanoids versus other active agents or versus other prostanoids because studies conducting these comparisons were few and we judged them to be at high risk of bias. None of the included studies assessed quality of life.

Authors' conclusions

We found high‐quality evidence showing that prostanoids have no effect on the incidence of total amputations when compared against placebo. Moderate‐quality evidence showed small beneficial effects of prostanoids for rest‐pain relief and ulcer healing when compared with placebo. Additionally, moderate‐quality evidence showed a greater incidence of adverse effects with the use of prostanoids, and low‐quality evidence suggests that prostanoids have no effect on cardiovascular mortality when compared with placebo. None of the included studies reported quality of life measurements. The balance between benefits and harms associated with use of prostanoids in patients with critical limb ischaemia with no chance of reconstructive intervention is uncertain; therefore careful assessment of therapeutic alternatives should be considered. Main reasons for downgrading the quality of evidence were high risk of attrition bias and imprecision of effect estimates.

Plain language summary

Prostanoids for people with severely blocked arteries of the leg

Background

People with severely blocked arteries of the leg suffer from pain, ulcers (areas showing loss of skin that do not heal easily), or gangrene (areas showing dead tissues resulting from loss of blood supply). This condition is usually associated with several risk factors, such as diabetes, smoking, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, obesity, and unhealthy lifestyle. The main treatments for people with this condition are surgical procedures performed to unblock the arteries. However, in some situations, surgical unblocking is not possible and amputation of part of the leg is required.

Prostanoids make up a family of medicines that could increase blood supply to the legs when taken orally or by injection. Prostanoids expand and open up small blood vessels and reduce the activity of inflammatory cells and platelets, preventing blood clots. We wanted to discover the benefits and harms of prostanoids for people whose leg arteries are severely blocked with no chance for surgical unblocking.

Review question

In this review, we studied the effect of prostanoids in people with severely blocked leg arteries who are not able to undergo any surgical unblocking procedure.

Study characteristics

We searched published and unpublished studies up to January 2017. We found 33 clinical trials with a total of 4477 participants; most were published in the 1980s and 1990s and were carried out in European countries. Eleven out of 33 studies received funding from pharmaceutical companies. Most studies included patients over 60 years old who had severe blocking of arteries of the leg; many also had diabetes. Follow‐up was usually less than 1 year.

Key results

We found that, when compared with placebo, prostanoids provided a small beneficial effect by alleviating pain in the leg at rest and improving ulcer healing. Prostanoids did not reduce deaths or the need for an amputation. We found that no studies evaluated the quality of life of people with this condition. We found insufficient evidence to compare effects of prostanoids against those of other medications or other prostanoids.

Our findings suggest that taking prostanoids does cause harm. When 1000 patients are treated with prostanoids, on average 674 (572 to 798) will experience adverse events, compared with 319 given placebo. Adverse events usually include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, headache, dizziness, and flushing. More severe adverse events include low blood pressure, chest pain, and abnormalities in heart rhythm.

Quality of the evidence

When evaluating effects of prostanoids on rest‐pain, ulcer healing, and adverse events, researchers provided moderate‐quality evidence; review authors downgraded this in most cases because of loss of participants to follow‐up. Evaluating cardiovascular mortality yielded evidence of low quality related to loss of participants to follow‐up and small numbers of reported events. On the other hand, the quality of evidence on risk of amputation was high.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

The term 'critical limb ischaemia' (CLI) should be used for all cases of chronic ischaemic rest‐pain, ulcers, or gangrene attributable to objectively proven arterial occlusive disease (Gerhard‐Herman 2016). CLI stands at the end of the most severe spectrum of peripheral arterial obstructive disease (PAOD). This multi‐factorial condition occurs secondary to the combination of endothelial dysfunction, dyslipidaemia, inflammatory and immunological factors, plaque rupture, and tobacco use. Unlike individuals with intermittent claudication (IC), patients with CLI have poor arterial blood flow to the lower limbs (resting perfusion), which is inadequate to sustain viability in the distal tissue bed. The European Working Group on CLI specifically defined this illness as the presence of ischaemic rest‐pain requiring analgesia for longer than two weeks, or ulceration, or gangrene of the lower extremity with ankle systolic blood pressure < 50 mmHg and/or toe systolic pressure < 30 mmHg (Anonymous 1991). Although the definition of CLI has evolved over time (Becker 2011), a recent multi‐disciplinary consensus ‐ the Peripheral Academic Research Consortium ‐ maintained those classic haemodynamic thresholds for patients with ischaemic rest‐pain, but defined CLI haemodynamic thresholds for patients with tissue loss as ankle systolic blood pressure < 70 mmHg and/or toe systolic pressure < 50 mmHg. This consensus definition also considers alternative haemodynamic parameters, such as transcutaneous oxygen (TcPO2) (< 20 mmHg for patients with ischaemic rest‐pain and < 40 mmHg for patients with tissue loss) and skin perfusion pressure (< 40 mmHg or < 30 mmHg, respectively) (Patel 2015).

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) affects approximately 12% of adults increasing to 20% in people aged 70 years or older (Dua 2016). CLI is the initial clinical presentation in only 1% to 2% of cases of PAD, whereas 40% to 50% of those affected begin with atypical leg pain, and 10% to 35% with IC; 20% to 50% are asymptomatic. After five years of progressive functional impairment, a further 1% to 2% of PAD cases will result in CLI and eventual amputation (Hirsch 2006). However, a more recent meta‐analysis estimated the deterioration rate to be as high as 21% (95% confidence interval (CI) 12% to 29%) over five years (Sigvant 2016). Published epidemiological data on this condition are remarkably variable owing to use of different definitions of CLI over time; this represents the main cause of difficulty for proper identification of arterial insufficiency causing signs and symptoms in a large number of patients for epidemiological studies (Becker 2011).

Besides age (Hylton 2014; Ostchega 2007), the most important clinical predictors for CLI progression are smoking and diabetes (Howard 2015). The risk associated with smoking applies to all ages and increases with the number of cigarettes smoked. Major PAD deterioration occurs in people with claudication who are heavy smokers (Aquino 2001). Diabetes is associated with greater severity of PAOD in the lower limbs, especially in the arteries below the knee (Jude 2001). People with claudication and diabetes are also at higher risk of amputation and mortality than those with IC but without diabetes (Aquino 2001; Jude 2001). However, it is difficult to determine the true impact of this condition on the prognosis of patients with CLI for two reasons: (1) the proportion of patients with diabetes is variable in different studies assessing the natural history of CLI; and (2) diagnosis of CLI in patients with diabetes is challenging owing to frequent comorbid neuropathy and infectious complications, which may lead to tissue lesions (Becker 2011).

The prognosis for limb and patient survival is variable in chronic CLI. The most important risk factors for amputation are those involved in progression to CLI (Howard 2015), as well as an ankle brachial index (ABI) below 0.5 (Jelnes 1986). Within a six‐month period, 20% of patients die, 35% live but require amputation, and the remaining 45% live with no immediate need for amputation (Dormandy 2000). Meta‐analysis of 10 case series and non‐interventional or placebo arms of randomised controlled trials revealed a mortality rate of 22% (95% CI 12% to 32%) and an amputation rate of 30% (95% CI 19% to 42%) after 12 to 18 months' follow‐up (Abu 2015). Even though the strength of evidence on pooled estimates was low owing to high risk of bias, heterogeneity, and imprecision, these results are consistent with previous observations (Dormandy 2000; Hirsch 2006; Norgren 2007) and with the findings of a more recent retrospective study, which reported a mortality rate of 15% among patients with CLI after one year, and 24% after two years' follow‐up (Melillo 2016).

The prognosis after amputation is even worse. According to the Second European Consensus Document on chronic CLI (Anonymous 1991), perioperative mortality varies between 5% and 10% for below‐knee amputation, and between 15% and 20% for above‐knee amputation, respectively. This information is consistent with that provided in more recent reports, which estimated in‐hospital mortality rates for minor and major amputees as 3.6% to 4.6% and 16.8% to 19.8%, respectively (Malyar 2016; Moxey 2010). A second amputation is required in 30% of cases (Norgren 2007), and full mobility is achieved in only 56% of patients who have a minor amputation and in 17% of those who have a major amputation (above‐ and below‐knee) one year after the procedure (Suckow 2012). Furthermore, it is well known that patients with PAD have elevated risks of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, transient ischaemic attack, and cardiovascular death (Criqui 2015).

Quality of life in patients with CLI is significantly impaired compared with that in the general population and in patients with less severe PAOD (Sprengers 2010). Psychological testing of these patients has typically disclosed quality of life indices similar to those of patients with cancer at critical or even terminal phases (Albers 1992). Most people with CLI who experienced amputations have reported mobility limitations, rest‐pain (amputation‐related pain or ischaemic‐related pain in the affected or contralateral limb), and depression as prevalent domains undermining their quality of life (Suckow 2015). Therefore, because of its negative impact on quality of life and poor prognosis in terms of both limb and patient survival, CLI is a critical health issue.

First‐line therapeutic options for CLI are limited to percutaneous transluminal angioplasty or surgical revascularisation. Unfortunately, many patients with CLI are poor candidates for either procedure because of comorbidities or vascular anatomy (lack of conduit). These patients have only medical treatment as a therapeutic alternative, and amputation (when necessary) as the last chance to survive.

Angiogenic factors have suggested favour for neovascularisation by increasing collateral circulation and enhancing blood flow to ischaemic limbs. Despite promising results of early studies assessing the efficacy of this innovative treatment, systematic reviews and meta‐analyses examining patients with PAD and CLI (Hammer 2013; Miao 2014) showed no significant differences between treatment and control groups in terms of amputation, mortality at one year, or wound healing at six months' follow‐up.

Other therapeutic strategies for non‐surgical patients, such as autologous implantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells and spinal cord stimulation, have proved modestly effective in decreasing the amputation rate and reducing pain during variable periods of follow‐up (Moazzami 2014; Ubbink 2013). However, the quality of evidence regarding these strategies is considered moderate.

Description of the intervention

Medical therapies that decrease pain, promote healing of skin lesions, and reduce the risk of amputation would be attractive alternatives for patients with CLI non‐suitable for revascularisation procedures. Several drugs have been used at this stage (e.g. cilostazol, pentoxifylline, naftidrofuryl) and have led to no significant benefit. Prostanoids have been used for treatment of individuals with PAD for longer than two decades because some trials have recommended their use (Balzer 1991; Brock 1990; ICAI Group 1999; Norgren 1990; Trubestein 1989; Verstraete 1994). This family of drugs consists of the following: prostaglandin E1 (also referred to as PGE1, or alprostadil, generally by intravenous or intra‐arterial administration for 21 days); prostacyclin (also referred to as PGI2, or epoprostenol, by intravenous administration for four to seven days, or by intra‐arterial administration for 72 hours); iloprost (by intravenous administration for 14 to 28 days, oral for 28 days up to one year); lipo‐ecraprost (by intravenous administration for 50 days); and ciprostene (by intravenous administration for seven days).

How the intervention might work

Prostanoids have pharmacological activities on endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and platelets that could favourably alter the otherwise inexorable downhill course of CLI. These include inhibition of platelet activation, adhesion, and aggregation; vasodilatation; vascular endothelial cytoprotection; and inhibition of leucocyte activation (Balzer 1991; Brock 1990; ICAI Group 1999; Norgren 1990; Robertson 2013; Trubestein 1989).

Why it is important to do this review

A few meta‐analyses such as Creutzig 2004 and Loosemore 1994 and reviews such as Dormandy 1996 have been published, but they did not include all types of prostanoids and all routes of administration. The first version of this Cochrane review, published in 2010, took into account new approaches regarding this therapeutic option to find conclusive evidence about the effectiveness and safety of the whole family of prostanoids for patients with CLI, including only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) considered to have low or moderate risk of bias (Ruffolo 2010).

Even though other review authors have performed updated systematic reviews on this topic, their approaches were narrower in terms of interventions evaluated (Brodszky 2011), or broader in terms of study populations, including patients with PAOD of any severity (Vitale 2016).

Moreover, since publication of the first version of this Cochrane systematic review, methodological standards have changed substantially. Currently, the preferred tool for appraisal of internal validity of RCTs is Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011b); use of any selection criterion based on a threshold of global quality assessment is discouraged. For these reasons, it is necessary to update this systematic review with the goal of reassessing eligibility of previously excluded studies and strength of evidence regarding effectiveness and safety of this pharmacological therapy.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of prostanoids in patients with CLI unsuitable for rescue or reconstructive intervention.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

People irrespective of age or gender, presenting with critical limb ischaemia of atherosclerotic origin, without chance of rescue or reconstructive intervention. We did not include studies with patients given a diagnosis of thromboangiitis obliterans, also known as Buerger's disease, unless more than 80% of participants fulfilled inclusion criteria, or disaggregated data were available for the group of participants with CLI of atherosclerotic origin.

Types of interventions

Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1, alprostadil), prostacyclin (PGI2, epoprostenol), iloprost, beraprost, cisaprost, ciprostene, clinprost, ecraprost, or taprostene compared with placebo or other pharmacological control treatments (e.g. pentoxifylline, cilostazol, naftidrofuryl, angiogenic therapy, other prostanoids). We did not include surgical treatments or other medical non‐pharmacological treatments as comparators.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Cardiovascular mortality (e.g. due to myocardial infarction, stroke, arrhythmia or variation form the normal rhythm of the heartbeat, sudden death)

Total amputations (major plus minor)

Quality of life (measured according to a validated quality of life questionnaire)

Adverse events of treatment

Secondary outcomes

Evaluation of rest‐pain and/or use of analgesic drugs (measured according to a validated pain scale and a validated questionnaire, respectively)

Evolution of tissue lesions (healing or non‐healing ulcers, according to surface area increase or decrease, and presence or absence of granulation tissue)

Major amputations (above or below knee)

Minor amputations (partial feet or fingers)

Ankle brachial index (ABI)

All‐cause mortality

Search methods for identification of studies

We did not restrict language of publication.

Electronic searches

For this update, the Cochrane Vascular Information Specialist (CIS) searched the following databases for relevant trials.

Cochrane Vascular Specialised Register (January 2017).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 1) via the Cochrane Register of Studies Online.

See Appendix 1 for details of the search strategy used to search CENTRAL.

The Cochrane Vascular Specialised Register is maintained by the CIS and is constructed from weekly electronic searches of MEDLINE Ovid, Embase Ovid, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), and through handsearching of relevant journals. A full list of databases, journals, and conference proceedings that have been searched, as well as the search strategies used, is presented in the Specialised Register section of the Cochrane Vascular module in the Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com).

The CIS and the review authors separately searched the following trial registries for details of ongoing and unpublished studies (January 2017).

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/trialsearch).

International Standard Randomised Controlled Trials Number (ISRCTN) Registry (www.isrctn.com/).

See Appendix 2 for details of the search strategies.

Searching other resources

We identified additional articles by reviewing reference lists of both papers identified by electronic searches and systematic reviews. We contacted pharmaceutical companies to ask about additional studies (Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Bayer‐Schering, Italfarmaco, Mitsubishi Pharma America, Pfizer, UCB Pharma, United Therapeutics).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For this update, two review authors (VV, JVAF or DC) independently checked titles, abstracts, and keywords of all references retrieved. We retrieved the full text of all studies considered potentially relevant, and each review author assessed these studies independently using a Study Eligibility Form. We resolved disagreements between the two review authors by consensus or, finally, by consultation with a third review author (AC).

Data extraction and management

For this update, two review authors (VV, JVAF, VS or DC) independently collected the following data from each included study using a Data Extraction Form, provided by Cochrane Vascular.

Publication type and source, including language of publication, year of publication, and method of retrieval of the report.

Sources of support.

Trial design, including methods of generation and concealment of allocation sequences, along with type of control intervention.

Setting, including country, and level of care.

Participants, including selection criteria used and numbers of withdrawals and dropouts per group.

Interventions, including dose, route of administration, and duration of treatment.

Outcome measures, including modalities and schedules of assessment, adverse events, and overall mortality and details of its causes.

Analysis, including whether analysis was done according to the intention‐to‐treat principle.

Results, including averages and variations in individual outcome assessments and different comparisons, test statistics, and P values for comparison within and between groups.

We resolved disagreements by consensus or by consultation with a third review author (AC), if required. We contacted primary study authors by email to obtain additional information. We collected all data in original units; therefore, transformation for comparisons was not necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For this update, two review authors (VV, JVAF, VS, or DC) independently assessed potential risks of bias for all included RCTs using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011b). This tool assesses bias in six different domains.

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective outcome reporting (reporting bias).

Other sources of bias.

Each domain received a score of high, low, or unclear risk of bias depending on each review author's judgement. We resolved disagreements by consensus and, if necessary, asked review author AC to act as arbitrator. We contacted study authors for clarification when doubt arose as to potential risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Even though clinical heterogeneity was significant, we did perform an overall meta‐analysis of prostanoids versus placebo, including subgroup analysis by type of prostanoid. We also completed analyses of prostanoids versus other active agents by describing results of individual studies or performing meta‐analyses when more than one study reported the same outcome (prostanoids compared with pentoxifylline, naftidrofuryl, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), or inositol niacinate) and we considered results to show clinical homogeneity. In addition, we completed analyses of prostanoids versus other prostanoids for the specific comparisons described in the included studies (iloprost vs PGE1, clinprost vs lipo‐PGE1). Finally, we prepared a qualitative synthesis of reported adverse events by type of prostanoid.

We analysed dichotomous data by using risk ratios (RRs) with a confidence interval (CI) of 95%. We analysed continuous data by using standardised mean differences (SMDs) with a CI of 95%.

Unit of analysis issues

For this update, we considered the individual participant as the unit of analysis. In the event that outcome information was reported as numbers of events instead of numbers of participants with at least one event, we did not include the study in the meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

In the event that data were missing from the full reports, we planned to move the study to Studies awaiting classification until we could obtain further information from the study authors. However, in four cases (potentially relevant studies published as abstracts), authors did not have the data, or did not reply, so we excluded their reports (Fonseca 1991; Menzoian 1995; Mingardi 1993; Schwarz 1995). We excluded another seven studies because trial authors reported only outcome measures combining participants with non‐critical limb ischaemia or with chance of reconstructive intervention and did not reply to our request for disaggregate data (Bertele 1999; Feng 2009; Guan 2003; Heidrich 1991; Ohtake 2014).

Assessment of heterogeneity

To test for statistical heterogeneity, although of limited power, we used the Chi² test with significance level set at P < 0.1 and the I² test. We interpreted the I² test as indicated in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a).

0% to 40%: might not be important.

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100%: represents considerable heterogeneity.

For robustness of results, and to perform a conservative analysis, if I² was 0% to 40%, suggesting not important heterogeneity, we reported results using a fixed‐effect model; if moderate heterogeneity was suggested by an I² between 30% and 60%, we reported results using a random‐effects model; and if I² was > 50%, suggesting substantial heterogeneity, we did not perform meta‐analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

We attempted to obtain study protocols to assess for selective outcome reporting. When study protocols were unavailable, we compared methods and results sections of the report.

We used funnel plots to assess small‐study effects when 10 or more studies were available for outcomes (Higgins 2011a). Several explanations can be offered for asymmetry in a funnel plot, including true heterogeneity of effect with respect to trial size, poor methodological design (and hence bias of small trials), and publication bias. We interpreted these results carefully.

Data synthesis

We performed random‐effects meta‐analysis when we found little evidence of clinical heterogeneity across studies. Additionally, when we found good evidence of homogeneous effects across studies, we performed fixed‐effect meta‐analysis (see Assessment of heterogeneity). We interpreted random‐effects meta‐analyses with due consideration of the whole distribution of effects. In addition, we performed statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). For dichotomous outcomes, we used the Mantel‐Haenszel method, and for continuous outcomes, we used the inverse variance method. We used Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014) software to perform analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When sufficient studies were available, we conducted subgroup analyses by type of prostanoid. We used the test for subgroup differences in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014) to compare subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of risk of bias on treatment effect sizes by excluding studies with high risk of bias in the following domains: allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias), and incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

'Summary of findings' table

We presented the overall quality of evidence for each outcome according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (Guyatt 2008), which takes into account five criteria.

Risk of bias.

Inconsistency.

Imprecision.

Publication bias.

Directness of results.

For each comparison, two review authors (VV and JVAF) independently rated the quality of evidence for each outcome as 'high', 'moderate', 'low', or 'very low' using GRADEpro GDT. We resolved discrepancies by consensus, or, if needed, by arbitration provided by a third review author (AC). For each comparison presented in the review, we presented a summary of evidence for main outcomes in a 'Summary of findings' table, which provides key information about the best estimate of the magnitude of effect in relative terms and absolute differences for each relevant comparison of alternative management strategies; numbers of participants and studies addressing each important outcome; and the rating of overall confidence in effect estimates for each outcome (Guyatt 2011; Schünemann 2011). When meta‐analysis was not possible, we presented results in a narrative 'Summary of findings' table.

We included in the 'Summary of findings' table data for all participants with critical limb ischaemia for the following outcomes.

Cardiovascular mortality.

Amputations (total: major and minor).

Quality of life.

Adverse events.

Rest‐pain relief.

Ulcer healing.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

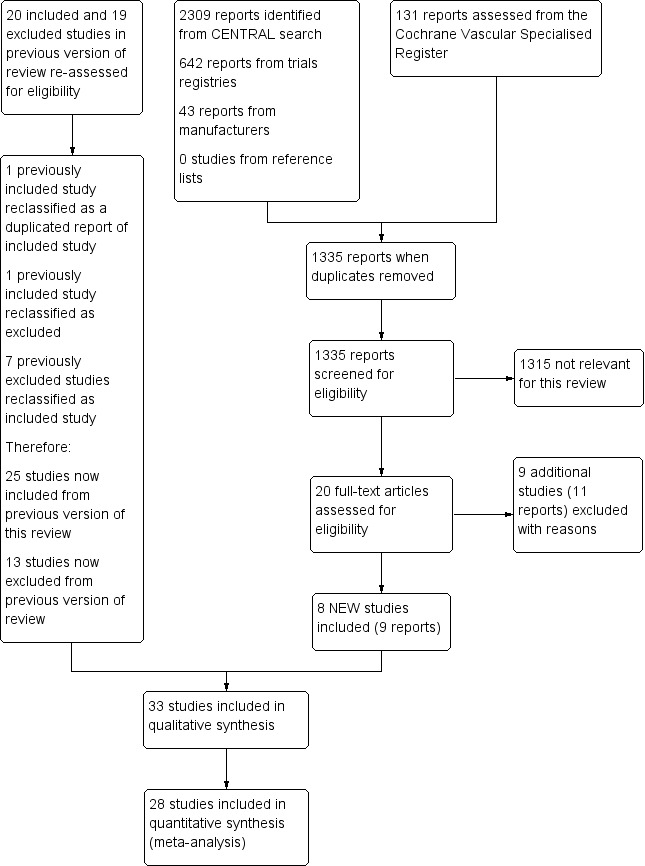

See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

*Out of 22 excluded studies, nine studies evaluated an inappropriate intervention for control group, seven included participants not fulfilling inclusion criteria with no available disaggregated outcome data, four were abstracts with no available full text, one had a quasi‐randomised design, and another was unpublished and had no available results.

For this update, we reassessed all 39 previously included (20) and excluded (19) studies for eligibility according to changes in selection criteria. We reclassified one previously included study as a duplicate report (Diehm 1987), reclassified another previously included study as excluded owing to inappropriate intervention for the control group (Beischer 1998), and reclassified seven previously excluded studies as included studies (Alstaedt 1993; Bandiera 1995; Böhme 1994; Cronenwett 1986; Diehm 1989; Karnik 1986; Trübestein 1989). We made no change to the other studies.

Included studies

We have listed details of the included studies below and in the Characteristics of included studies table.

For this update, we reassessed seven previously excluded studies for inclusion (Alstaedt 1993; Bandiera 1995; Böhme 1994; Cronenwett 1986; Diehm 1989; Karnik 1986; Trübestein 1989), and we identified eight new included studies (Belch 2011; Castagno 2000; Esato 1995; Jogestrand 1985; NCT00596752; Reisin 1997; Sakaguchi 1984; Schuler 1984). We reclassified one previously included study (Diehm 1987) as a preliminary report of another included study (Diehm 1988), based on information provided by personal contact with study authors. We reclassified another previously included study as excluded owing to inappropriate intervention for the control group (Beischer 1998).

In total, we included in the review 33 trials with a total of 4477 randomised participants (Alstaedt 1993; Balzer 1991; Bandiera 1995; Belch 1983; Belch 2011; Böhme 1989; Böhme 1994; Brass 2006; Brock 1990; Castagno 2000; Cronenwett 1986; Diehm 1988; Diehm 1989; Dormandy 1991; Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B; Esato 1995; Guilmot 1991; Hossmann 1983; Jogestrand 1985; Karnik 1986; Linet 1991; NCT00596752; Negus 1987; Norgren 1990; Reisin 1997; Sakaguchi 1984; Schellong 2004; Schuler 1984; Stiegler 1992; Telles 1984; Trubestein 1987; Trübestein 1989).

Most studies were published in English, but nine were published in German (Böhme 1989; Böhme 1994; Brock 1990; Diehm 1988; Diehm 1989; Hossmann 1983; Karnik 1986; Stiegler 1992; Trubestein 1987), one in Japanese (Esato 1995), and one in Italian (Bandiera 1995). We obtained information from the ClinicalTrials.gov database on the unpublished clinical trial NCT00596752.

We included 21 studies that compared a prostanoid versus placebo intravenously administered: seven studies on PGE1 (Diehm 1988; Jogestrand 1985; NCT00596752; Reisin 1997; Schuler 1984; Stiegler 1992; Telles 1984), three on PGI2 (Belch 1983; Cronenwett 1986; Hossmann 1983), six on iloprost (Balzer 1991; Brock 1990; Diehm 1989; Dormandy 1991; Guilmot 1991; Norgren 1990), and three single studies on lipo‐ecraprost (Brass 2006), taprostene (Belch 2011), or ciprostene (Linet 1991). Two additional studies compared high‐dose and low‐dose oral iloprost versus placebo (Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B).

Five studies compared PGE1 against other active drugs. One study compared PGE1 infused intravenously (iv) versus pentoxifylline (Trübestein 1989), and another compared the same prostanoid versus naftidrofuryl (Böhme 1994). Another two studies compared intra‐arterial (ia) administered PGE1 versus adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Böhme 1989; Trubestein 1987), and a third compared high‐dose and low‐dose PGE1 infused ia versus oral inositol niacinate (Sakaguchi 1984).

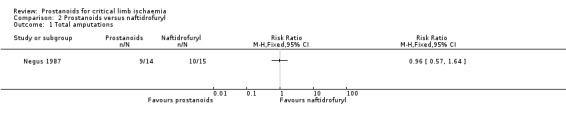

Two studies compared PGI2 versus naftidrofuryl: One used the ia route of administration (through a 21 spring wire guide (SWG) catheter inserted into the common femoral artery) (Negus 1987), and the other used the iv route (Karnik 1986).

Finally, five studies compared different prostanoids: Four studies evaluated iv iloprost versus PGE1 (Alstaedt 1993; Bandiera 1995; Castagno 2000; Schellong 2004), and another compared TTC‐909 (clinprost incorporated in lipid microspheres) versus lipo‐PGE1 (Esato 1995), both administered iv.

No studies evaluating beraprost or cisaprost fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Length of treatment ranged from three days to four weeks, except for one cross‐over study, for which length of treatment was three hours with a washout period of one day between interventions (Schellong 2004). Length of participant follow‐up ranged from two weeks to six months, except for two studies, in which follow‐up lasted three years and four years (Sakaguchi 1984 and NCT00596752, respectively).

Excluded studies

We have listed details of excluded studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

For this update, we identified nine new excluded studies (Esato 1997; Feng 2009; NCT00059644; Nizankowski 1985; Ohtake 2014; Sakaguchi‐Shukichi 1990; Sert 2008; Weiss 1991; Ylitalo 1990). We reclassified one previously included study as excluded (Beischer 1998). We also reclassified and included seven studies that were excluded in the previous review owing to high risk of bias (see Included studies), making a total of 22 excluded studies.

Among the 22 excluded studies, the most frequent criteria for exclusion were inappropriate or no intervention for the control group (Arosio 1998; Beischer 1998; Breuer 1995; Ceriello 1998; Di Paolo 2005; Esato 1997; Petronella 2004; Sert 2008; Weiss 1991) and participants not fulfilling inclusion criteria with no available disaggregated outcome data (Bertele 1999; Feng 2009; Guan 2003; Heidrich 1991; Nizankowski 1985; Ohtake 2014; Ylitalo 1990). Four out of 22 studies were abstracts for which we were unable to obtain full text in spite of contacting trial authors for further information (Fonseca 1991; Menzoian 1995; Mingardi 1993; Schwarz 1995). Finally, one study was non‐randomised (Sakaguchi‐Shukichi 1990), and another was unpublished and no results were available (NCT00059644).

Risk of bias in included studies

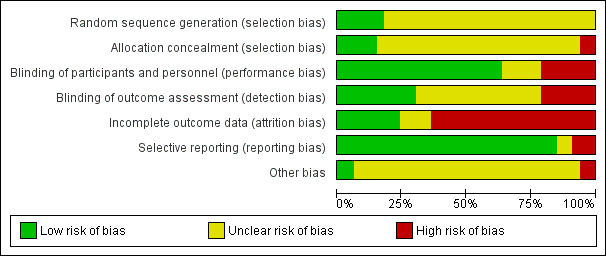

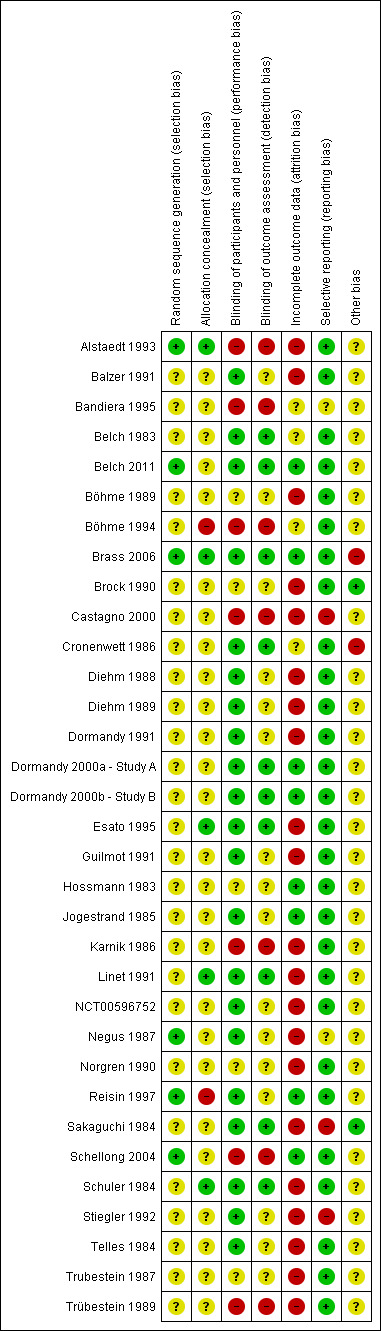

None of the included studies presented low risk of bias in all domains, and most studies presented at least one domain with high risk of bias (see Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; and Figure 3).

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Of the 33 included studies, six (18%) described the method used for the randomisation process (see Characteristics of included studies). One study used a random number table (Alstaedt 1993), three used a computer‐generated randomisation list (Belch 2011; Brass 2006; Schellong 2004), one study reported use of random numbers (Negus 1987), and another stated that investigators used a randomised, permuted block design (Reisin 1997). The remaining studies did not provide sufficient information, and we deemed that they had unclear risk of bias.

Seven studies (21%) provided an explanation of the allocation concealment process. Five studies described use of an adequate method for allocation concealment, which included central allocation (Alstaedt 1993; Brass 2006), a sealed packaging method (Esato 1995), and a code of drug assignment supplied by the study sponsor (Linet 1991; Schuler 1984). Two studies reported that researchers used a randomisation or allocation list (Böhme 1994; Reisin 1997); we therefore considered them to have high risk of bias. The remaining studies did not provide sufficient information, and we deemed that they had unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

Of the 33 included studies, 21 (64%) reported a double‐blind design, and we considered them to be at low risk of performance bias (see Characteristics of included studies). Seven studies (21%) were open‐label studies; we therefore considered them to have high risk of bias owing to the subjective nature of reported outcomes (Alstaedt 1993; Bandiera 1995; Böhme 1994; Castagno 2000; Karnik 1986; Schellong 2004; Trübestein 1989). Five studies (15%) provided no statement or information about blinding (Böhme 1989; Brock 1990; Hossmann 1983; Norgren 1990; Trubestein 1987), and we deemed that they were at unclear risk of bias.

Among the 21 studies described by trial authors as double‐blind, 10 stated that not only participants and study personnel, but also outcome assessors, were blinded (Belch 1983; Belch 2011; Brass 2006; Cronenwett 1986; Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B; Esato 1995; Linet 1991; Sakaguchi 1984; Schuler 1984); we therefore considered them to be at low risk of detection bias. The remaining 11 studies (Balzer 1991; Diehm 1988; Diehm 1989; Dormandy 1991; Guilmot 1991; Jogestrand 1985; NCT00596752; Negus 1987; Reisin 1997; Stiegler 1992; Telles 1984) did not mention whether outcome assessors were blinded; therefore we considered them to be at unclear risk of detection bias. We considered the seven open‐label studies to be at high risk of bias in this domain as they did not include a blinded outcome assessor (Alstaedt 1993; Bandiera 1995; Böhme 1994; Castagno 2000; Karnik 1986; Schellong 2004; Trübestein 1989). Five studies (15%) provided no statement or information about blinding of outcome assessment (Böhme 1989; Brock 1990; Hossmann 1983; Norgren 1990; Trubestein 1987); we deemed that these studies had unclear risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Of the 33 studies included, 30 (90%) reported participant withdrawals (see Characteristics of included studies). Twenty‐one (64%) studies had high risk of bias in this domain: 16 described an attrition rate greater than 10% (Alstaedt 1993; Balzer 1991; Böhme 1989; Brock 1990; Diehm 1989; Dormandy 1991; Esato 1995; Guilmot 1991; Karnik 1986; Linet 1991; NCT00596752; Negus 1987; Norgren 1990; Sakaguchi 1984; Schuler 1984; Stiegler 1992), one reported unbalanced withdrawals in the control group (Castagno 2000), and four did not perform intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis (Diehm 1988; Telles 1984; Trubestein 1987; Trübestein 1989). Four studies did not provide sufficient information, and we deemed that they were at unclear risk of bias in this domain (Bandiera 1995; Belch 1983; Böhme 1994; Cronenwett 1986); we considered the remaining eight studies to have low risk of attrition bias owing to complete follow‐up or attrition rate less than 10% and ITT analysis (Belch 2011; Brass 2006; Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B; Hossmann 1983; Jogestrand 1985; Reisin 1997; Schellong 2004).

Selective reporting

Of the 33 studies included, 28 (85%) reported all outcomes specified in the methods section (see Characteristics of included studies). We considered three studies as having high risk of selective reporting bias because we noted differences between outcomes reported in the methods and results sections (Stiegler 1992); because only the composite efficacy outcome was reported (Castagno 2000); or because reported outcomes were subjective and were not clearly defined (Sakaguchi 1984). Two studies did not provide prespecified outcomes in the methods section (Bandiera 1995; Negus 1987); we deemed that they had unclear risk of bias.

One of the included studies is a report of adverse events of a larger efficacy study, which we could not retrieve by applying search strategies and contacting trial authors (Bandiera 1995).

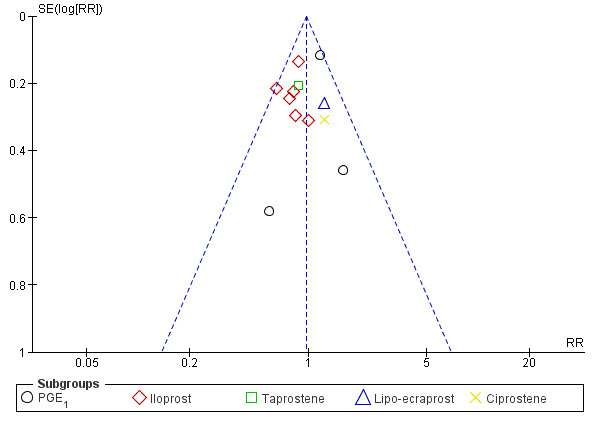

Regarding publication bias, we did not detect important asymmetries in the following outcomes from funnel plots performed for meta‐analyses, including at least 10 studies that compared prostanoids versus placebo: total amputations (Figure 4), all‐cause mortality, rest‐pain relief (dichotomous variable), and ulcer healing.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Prostanoids versus placebo, outcome: 1.2 Total amputations.

Other potential sources of bias

We considered two studies to have low risk of bias because trial authors provided a complete description of baseline characteristics of included participants and identical care programmes for both groups (Brock 1990; Sakaguchi 1984). One study presented unbalanced baseline characteristics and co‐interventions between groups (Cronenwett 1986), and another was terminated early because of futility (Brass 2006); therefore we considered these studies to have high risk of bias.

The remaining 29 studies presented unclear risk of bias in this domain as the result of incomplete description of care programmes and baseline risk of included participants (Alstaedt 1993; Balzer 1991; Bandiera 1995; Belch 1983; Belch 2011; Böhme 1989; Böhme 1994; Castagno 2000; Diehm 1988; Diehm 1989; Dormandy 1991; Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B; Esato 1995; Guilmot 1991; Hossmann 1983; Jogestrand 1985; Karnik 1986; Linet 1991; NCT00596752; Negus 1987; Norgren 1990; Reisin 1997; Schellong 2004; Schuler 1984; Stiegler 1992; Telles 1984; Trubestein 1987; Trübestein 1989).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Prostanoids compared with placebo for critical limb ischaemia.

| Prostanoids compared with placebo for critical limb ischaemia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with critical limb ischaemia Setting: hospital Intervention: prostanoids Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with prostanoids | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality Follow‐up: range 2 months to 7 months | Study population | RR 0.81 (0.41 to 1.58) | 1170 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ||

| 32 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (13 to 51) | |||||

| Total amputations Follow‐up: range 1 month to 12 months | Study population | RR 0.97 (0.86 to 1.09) | 2825 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGHc | ||

| 269 per 1000 | 261 per 1000 (231 to 293) | |||||

| Quality of life | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included trials reported this outcome. | |

| Adverse events (participants) Follow‐up: range 3 weeks to 7 months | Study population | RR 2.11 (1.79 to 2.50) | 655 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | ||

| 319 per 1000 | 674 per 1000 (572 to 798) | |||||

| Rest‐pain relief (dichotomous) Follow‐up: range 1 month to 12 months | Study population | RR 1.30 (1.06 to 1.59) | 1179 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | ||

| 228 per 1000 | 296 per 1000 (241 to 362) | |||||

| Ulcer healing Follow‐up: range 3 weeks to 6 months | Study population | RR 1.24 (1.04 to 1.48) | 1719 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | ||

| 358 per 1000 | 444 per 1000 (373 to 530) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level because most studies were at high risk of bias (attrition bias). bDowngraded by one level for not meeting optimal information size (OIS) (for a 25% relative risk ratio (RRR), alpha = 0.05 and beta = 0.20, OIS = 13342). The 95% confidence interval includes both appreciable benefit and harm. cEven though eight trials were at high risk of attrition bias, a sensitivity analysis excluding those studies did not modify the effects of prostanoids (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.10).

Summary of findings 2. Prostanoids compared with pentoxifylline for critical limb ischaemia.

| Prostanoids compared with pentoxifylline for critical limb ischaemia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with critical limb ischaemia Setting: hospital Intervention: prostanoids Comparison: pentoxifylline | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with pentoxifylline | Risk with prostanoids | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

| Total amputations Follow‐up: range 1 month to 6 months | Study population | RR 0.50 (0.05 to 5.27) | 70 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b | ||

| 57 per 1000 | 29 per 1000 (3 to 301) | |||||

| Quality of life | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

| Adverse events (participants) Follow‐up: range 1 month to 6 months | Study population | RR 0.60 (0.24 to 1.47) | 70 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b | ||

| 286 per 1000 | 171 per 1000 (69 to 420) | |||||

| Rest‐pain relief | Study population | RR 1.40 (0.72 to 2.72) | 70 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b | ||

| 286 per 1000 | 400 per 1000 (206 to 777) | |||||

| Ulcer healing | Study population | RR 1.61 (1.13 to 2.30) | 70 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b | ||

| 514 per 1000 | 828 per 1000 (581 to 1000) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by two levels owing to high risk of performance bias (open‐label study) and attrition bias, and owing to imbalance in baseline characteristics of participants with no mention of methods used for random sequence generation or allocation concealment. bDowngraded by one level owing to wide confidence interval.

Summary of findings 3. Prostanoids compared with naftidrofuryl for critical limb ischaemia.

| Prostanoids compared with naftidrofuryl for critical limb ischaemia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with critical limb ischaemia Setting: hospital Intervention: prostanoids Comparison: naftidrofuryl | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with naftidrofuryl | Risk with prostanoids | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

| Total amputations Follow‐up: range 6 months to 4 years | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.57 to 1.64) | 29 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ||

| 667 per 1000 | 640 per 1000 (380 to 1000) | |||||

| Quality of life | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

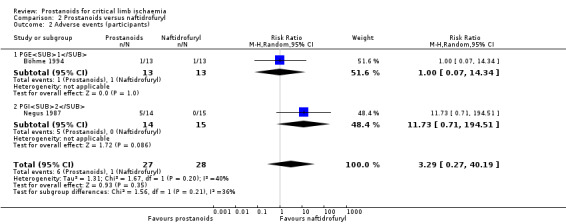

| Adverse events (participants) Follow‐up: range 3 days to 2 weeks | Study population | RR 3.29 (0.27 to 40.19) | 55 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,c | ||

| 36 per 1000 | 118 per 1000 (10 to 1000) | |||||

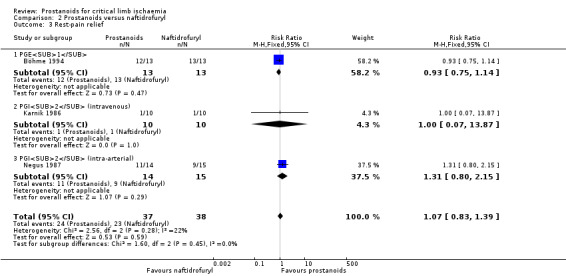

| Rest‐pain relief Follow‐up: range 3 weeks to 4 weeks | Study population | RR 1.07 (0.83 to 1.39) | 75 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,d | ||

| 605 per 1000 | 648 per 1000 (502 to 841) | |||||

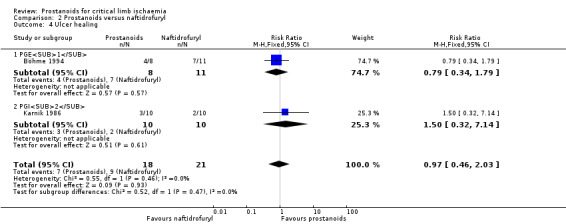

| Ulcer healing Follow‐up: range 3 weeks to 4 weeks | Study population | RR 0.97 (0.46 to 2.03) | 39 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,c | ||

| 429 per 1000 | 416 per 1000 (197 to 870) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level owing to high risk of attrition bias. bDowngraded by one level owing to imprecision issues (low rate of events). cDowngraded by one level owing to high risk of bias (one trial presented high risk of performance and detection bias, and the other high risk of attrition bias). dDowngraded by one level owing to high risk of bias (most studies presented high risk of performance and detection bias or performance bias).

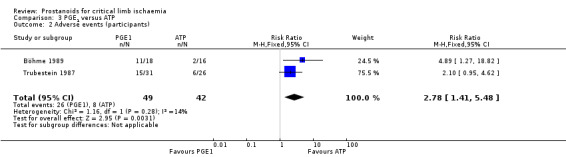

Summary of findings 4. PGE1 compared with ATP for critical limb ischaemia.

| PGE1 compared with ATP for critical limb ischaemia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with critical limb ischaemia Setting: hospital Intervention: PGE1 Comparison: ATP | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with ATP | Risk with PGE1 | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

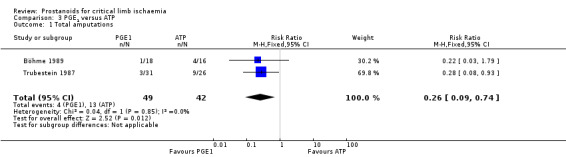

| Total amputations Follow‐up: range 3 weeks to 12 months | Study population | RR 0.26 (0.09 to 0.74) | 91 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ||

| 310 per 1000 | 80 per 1000 (28 to 229) | |||||

| Quality of life | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

| Adverse event (participants) Follow‐up: range 3 weeks to 12 months | Study population | RR 2.78 (1.41 to 5.48) | 91 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ||

| 190 per 1000 | 530 per 1000 (269 to 1000) | |||||

| Rest‐pain relief | See comments. | ‐ | 34 (1 RCT) | ‐ | One study reported rest‐pain as a continuous outcome. Reanalysis was not possible. | |

| Ulcer healing (complete) Follow‐up: median 3 weeks | Study population | RR 0.72 (0.17 to 3.03) | 31 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ||

| 231 per 1000 | 166 per 1000 (39 to 699) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ATP: adenosine triphosphate; CI: confidence interval; PG: prostaglandin; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level owing to high risk of attrition bias. bDowngraded by one level owing to a wide confidence interval resulting from a low rate of events.

Summary of findings 5. PGE1 compared with inositol niacinate for critical limb ischaemia.

| PGE1 compared with inositol niacinate for critical limb ischaemia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with critical limb ischaemia Setting: hospital Intervention: PGE1 Comparison: inositol niacinate | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with inositol niacinate | Risk with PGE1 | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

| Total amputations | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

| Quality of life | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

| Adverse events (participants) Follow‐up: range 2 weeks to 6 weeks | Study population | RR 1.60 (0.79 to 3.23) | 65 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ||

| 333 per 1000 | 533 per 1000 (263 to 1000) | |||||

| Rest‐pain relief Follow‐up: range 2 weeks to 6 weeks | Study population | RR 1.45 (0.88 to 2.37) | 65 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ||

| 500 per 1000 | 725 per 1000 (440 to 1000) | |||||

| Ulcer healing Follow‐up: range 2 weeks to 6 weeks | Study population | RR 3.06 (0.41 to 22.79) | 65 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ||

| 56 per 1000 | 170 per 1000 (23 to 1000) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; PG: prostaglandin; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level owing to high risk of attrition bias. bDowngraded by one level owing to a low rate of events resulting in wide confidence intervals.

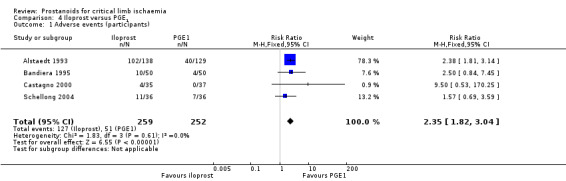

Summary of findings 6. Iloprost compared with PGE1 for critical limb ischaemia.

| Iloprost compared with PGE1 for critical limb ischaemia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with critical limb ischaemia Setting: hospital Intervention: iloprost Comparison: PGE1 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with PGE1 | Risk with iloprost | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

| Total amputations Follow‐up: range 4 weeks to 6 months | Study population | RR 0.89 (0.66 to 1.21) | 209 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ||

| 466 per 1000 | 415 per 1000 (308 to 564) | |||||

| Quality of life | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

| Adverse events (participants) Follow‐up: range 2 days to 4 weeks | Study population | RR 2.35 (1.82 to 3.04) | 511 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | ||

| 202 per 1000 | 476 per 1000 (368 to 615) | |||||

| Rest‐pain relief Follow‐up: range 21 days to 28 days | Study population | RR 1.15 (0.90 to 1.47) | 228 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ||

| 491 per 1000 | 565 per 1000 (442 to 722) | |||||

| Ulcer healing Follow‐up: range 21 days to 28 days | Study population | RR 1.24 (0.95 to 1.63) | 228 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ||

| 536 per 1000 | 664 per 1000 (509 to 873) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; PG: prostaglandin; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level owing to high risk of bias (performance, detection, and attrition bias). bDowngraded by one level owing to a low rate of events resulting in a wide confidence interval.

Summary of findings 7. Clinprost compared with lipo‐PGE1 for critical limb ischaemia.

| Clinprost compared with lipo‐PGE1 for critical limb ischaemia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with critical limb ischaemia Setting: hospital Intervention: clinprost Comparison: lipo‐PGE1 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with lipo‐PGE1 | Risk with clinprost | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality | See comments. | ‐ | (1 RCT) | ‐ | The trial authors mentioned the incidence of 1 death due to acute heart failure during the trial in the clinprost group. They did not discriminate whether this happened in the CLI from atherosclerotic origin group or in the thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO) group. | |

| Total amputations | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

| Quality of life | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

| Adverse events Follow‐up: median 28 days | Study population | RR 1.83 (0.56 to 5.96) | 135 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | The trial authors did not discriminate whether adverse events happened in the CLI from atherosclerotic origin group or in the TAO group. | |

| 58 per 1000 | 106 per 1000 (32 to 346) | |||||

| Rest‐pain relief Follow‐up: median 28 days | Study population | RR 1.05 (0.58 to 1.87) | 67 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ||

| 394 per 1000 | 414 per 1000 (228 to 737) | |||||

| Ulcer healing Follow‐up: median 28 days | Study population | RR 1.18 (0.74 to 1.89) | 72 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ||

| 457 per 1000 | 539 per 1000 (338 to 864) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CLI: critical limb ischaemia; PG: prostaglandin; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; TAO: thromboangiitis obliterans. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level owing to few events, resulting in a wide confidence interval that includes both harms and benefits. bDowngraded by one level owing to high risk of bias (attrition rate > 10%).

Prostanoids versus placebo

As we could obtain neither concrete nor homogeneous definitions of some of the predefined outcomes, we considered the following outcomes as a dichotomous outcome: evaluation of rest‐pain relief when it was reported as the number or proportion of participants who experienced any improvement on a pain scale (considered no relief if pain was the same or worse); and ulcer healing when it was reported as the number or proportion of participants who had any decrease in surface area and/or presence of granulation tissue (considered no healing if surface area was similar or bigger and/or granulation tissue was absent).

Although we noted some clinical heterogeneity (study designs, types of prostanoid, and routes of administration differed significantly among included studies), we completed a global meta‐analysis of any type of prostanoid given via any route versus placebo. The aim was to allow a meaningful meta‐analysis of the same class of drug with the same expected biochemical action.

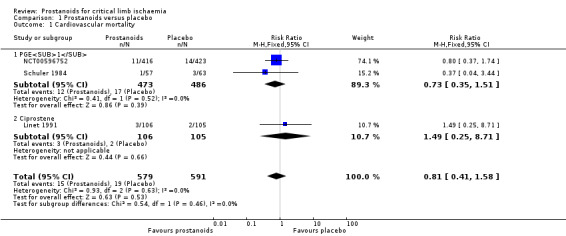

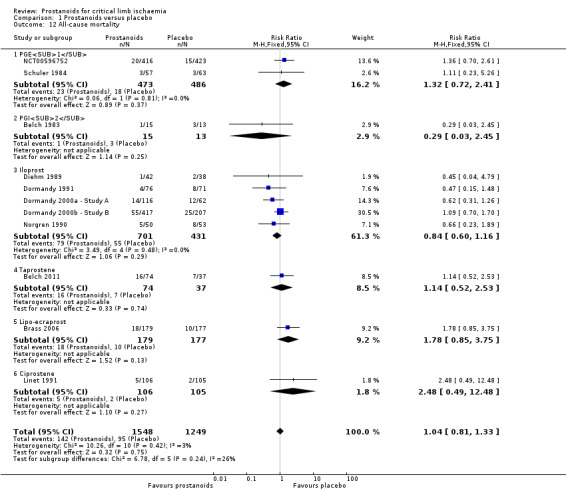

Cardiovascular mortality

Three studies reported cardiovascular mortality (two on PGE1 (NCT00596752; Schuler 1984), and one on ciprostene (Linet 1991)), with a similar incidence in both groups (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.58; 1170 participants; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.1). We used a fixed‐effect model because statistical heterogeneity was not important.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Prostanoids versus placebo, Outcome 1 Cardiovascular mortality.

Subgroup analysis by type of prostanoid revealed no differences for cardiovascular mortality (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.54, df = 1 (P = 0.46), I² = 0%).

The quality of this evidence is low given that all studies had high risk of attrition bias and the number of events in each group was small, resulting in a wide confidence interval that includes both appreciable benefit and harm (see Table 1).

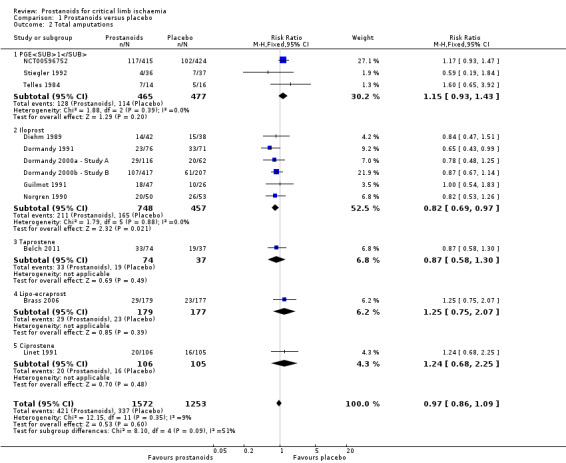

Total amputations

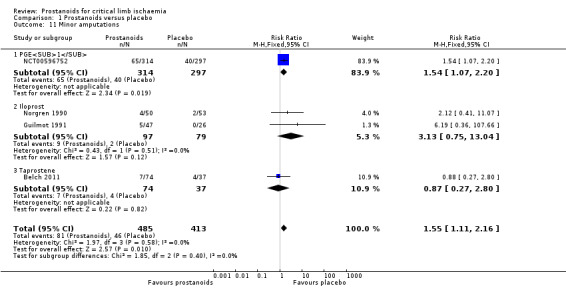

Twelve studies reported amputations: One study reported major, minor, and total amputations (Norgren 1990); three reported major and minor amputations (Belch 2011; Guilmot 1991; NCT00596752); four reported major amputations (Brass 2006; Dormandy 1991; Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B); and the remaining four reported the total number of amputations, including major and minor (Diehm 1989; Linet 1991; Stiegler 1992; Telles 1984).

We pooled results for total (major and minor) amputations across the 12 studies (three on PGE1 (NCT00596752; Stiegler 1992; Telles 1984), six on iloprost (Diehm 1989; Dormandy 1991; Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B; Guilmot 1991; Norgren 1990), one on taprostene (Belch 2011), one on lipo‐ecraprost (Brass 2006), and another on ciprostene (Linet 1991)). We found that 421/1572 events were reported in the prostanoids group and 337/1253 in the placebo group (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.09; I² = 9%; Analysis 1.2). We used a fixed‐effect model owing to lack of important statistical heterogeneity.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Prostanoids versus placebo, Outcome 2 Total amputations.

Subgroup analysis by type of prostanoid revealed differences for total amputations (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 8.10, df = 4 (P = 0.09), I² = 50.6%) owing to better results with iloprost against placebo (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.97) than with the other prostanoids, which showed minimal or no effect.

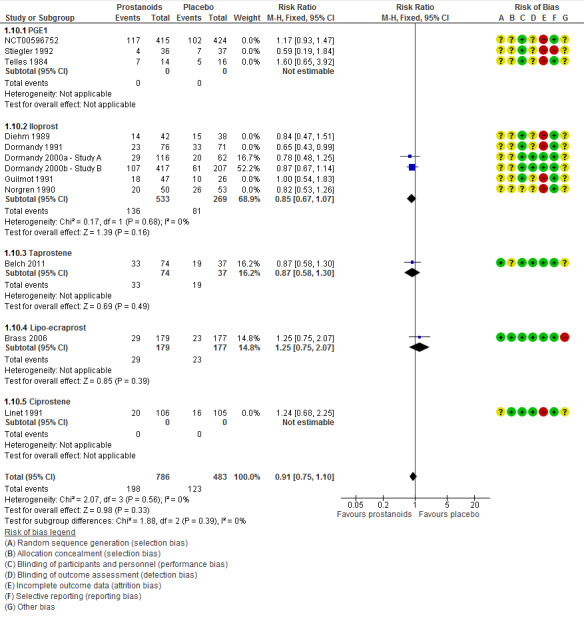

Even though several trials were at high risk of attrition bias, when we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding those studies (Diehm 1989; Dormandy 1991; Guilmot 1991; Linet 1991; NCT00596752; Norgren 1990; Stiegler 1992; Telles 1984), effects of prostanoids with regards to the incidence of total amputations were not modified (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.10; 1269 participants; I² = 0%; Figure 5). For this reason, we consider the quality of this evidence to be high (see Table 1).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Prostanoids versus placebo, outcome: 1.10 Total amputations. Sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of attrition bias.

Quality of life

None of the included studies reported this outcome.

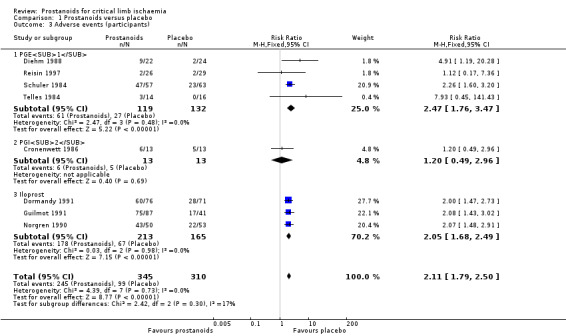

Adverse events

Fourteen studies reported adverse events. We excluded six studies from the meta‐analysis because they reported total numbers of adverse events instead of numbers of participants with at least one event (Belch 1983; Belch 2011; Linet 1991; NCT00059644), or they reported tolerability outcomes entailing clinical heterogeneity in relation to the definition of adverse event (Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B).

Eight studies reported extractable information about numbers of participants with adverse events, and we included them in the meta‐analysis (four studies on PGE1 (Diehm 1988; Reisin 1997; Schuler 1984; Telles 1984), one on PGI2 (Cronenwett 1986), and three on iloprost (Dormandy 1991; Guilmot 1991; Norgren 1990)). Pooled results showed that 245/345 participants in the prostanoids group had adverse effects compared with 99/310 in the placebo group (RR 2.11, 95% CI 1.79 to 2.50; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.3). We used a fixed‐effect model because statistical heterogeneity was unimportant.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Prostanoids versus placebo, Outcome 3 Adverse events (participants).

Subgroup analysis by type of prostanoid revealed no differences for this outcome (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 2.42, df = 2 (P = 0.30), I² = 17.4%).

A sensitivity analysis excluding trials at high risk of selection bias did not affect the pooled estimate (RR 2.13, 95% CI 1.80 to 2.52; 600 participants; I² = 0%) (Reisin 1997). Nevertheless, the quality of evidence regarding this outcome was moderate owing to high risk of attrition bias in six out of eight studies (Diehm 1988; Dormandy 1991; Guilmot 1991; Norgren 1990; Schuler 1984; Telles 1984); exclusion of these studies from the sensitivity analysis influenced the overall effect (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.51 to 2.71; 81 participants; I² = 0%), resulting in a wider confidence interval that included both appreciable benefit and harm (see Table 1).

Rest‐pain relief

We found 18 studies that reported rest‐pain relief. We excluded four studies from the meta‐analysis owing to unavailability of extractable or enough data for an appropriate analysis (Belch 2011; Hossmann 1983; Jogestrand 1985; Stiegler 1992).

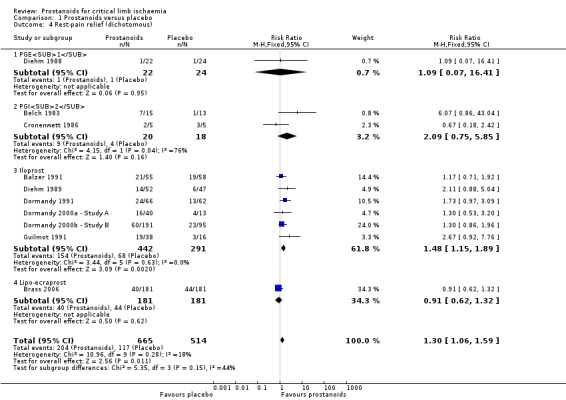

We included 10 studies in a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for dichotomous assessment of rest‐pain relief (one on PGE1 (Diehm 1988), two on PGI2 (Belch 1983; Cronenwett 1986), six on iloprost (Balzer 1991; Diehm 1989; Dormandy 1991; Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B; Guilmot 1991), and one on lipo‐ecraprost (Brass 2006)). As subgroup analysis revealed no differences between high‐dose and low‐dose iloprost against placebo for this outcome (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.82, df = 1 (P = 0.37), I² = 0%) (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.46; 739 participants; 10 studies; I² = 24%), we presented data from the two studies combined (Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B). Pooled results indicate that 204/665 participants who received prostanoids and 117/514 who received placebo achieved rest‐pain relief (RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.59; I² = 18%; Analysis 1.4). Subgroup analysis revealed no differences between different types of prostanoids (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 5.35, df = 3 (P = 0.15), I² = 43.9%).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Prostanoids versus placebo, Outcome 4 Rest‐pain relief (dichotomous).

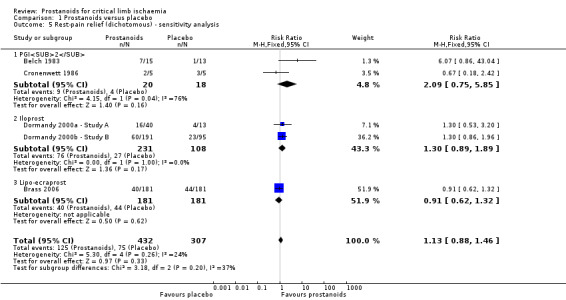

The quality of this evidence was moderate owing to high risk of attrition bias in five studies (see Table 1). A sensitivity analysis excluding those studies (Balzer 1991; Diehm 1988; Diehm 1989; Dormandy 1991; Guilmot 1991) yielded a similar incidence of rest‐pain relief in the group that received prostanoids compared with the group given placebo (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.46; 739 participants; I² = 24%; Analysis 1.5). However, estimates lost precision and resulted in a wider confidence interval that included both appreciable benefit and harm.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Prostanoids versus placebo, Outcome 5 Rest‐pain relief (dichotomous) ‐ sensitivity analysis.

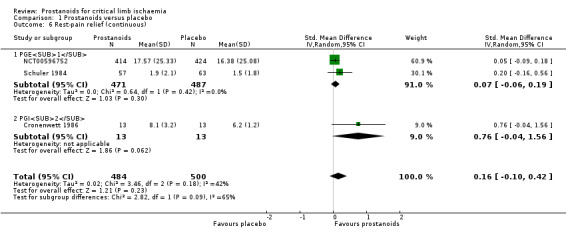

We included three studies with 984 participants in a meta‐analysis for continuous measurement of rest‐pain relief (two on PGE1 (NCT00596752; Schuler 1984) and one on PGI2 (Cronenwett 1986)). We summarised rest‐pain scores in a random‐effects model meta‐analysis for standardised mean differences (SMDs), obtaining 0.16 (95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.42; I² = 42%; Analysis 1.6). Confidence intervals of the prostanoids subgroups overlapped, and studies were too few to permit conclusions about whether one type of prostanoid produced more rest‐pain relief than another. The quality of this evidence is low owing to high risk of bias and inconsistency across included studies.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Prostanoids versus placebo, Outcome 6 Rest‐pain relief (continuous).

Two other studies reported results regarding rest‐pain relief qualitatively, stating no significant differences between treatment and control groups (Linet 1991; Telles 1984).

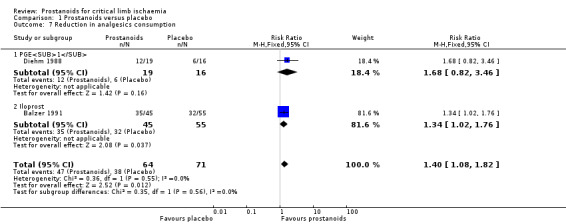

Reduction in analgesic consumption

We found five studies that reported analgesics consumption. We excluded three studies from meta‐analysis: two because extractable data were unavailable (Brock 1990; NCT00596752), and another because investigators reported a continuous outcome (Belch 1983).

We included two studies in a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for dichotomous assessment of reduction in analgesics consumption (one on PGE1 (Diehm 1988), and one on iloprost (Balzer 1991)). Pooled results showed that 47/64 participants receiving prostanoids and 38/71 receiving placebo achieved a reduction in analgesic consumption (RR 1.40, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.82; 135 participants; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.7). Subgroup analysis by type of prostanoid showed no differences for this outcome (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.35, df = 1 (P = 0.56), I² = 0%).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Prostanoids versus placebo, Outcome 7 Reduction in analgesics consumption.

Belch 1983 reported a significant reduction in mean daily analgesic consumption compared with baseline in both groups of participants, but the mean difference between groups was not statistically significant neither during the infusion (mean difference (MD) ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐1.06 to 0.66) nor after four days' follow‐up (MD 0.40, 95% CI ‐0.53 to 1.33).

Two studies described results regarding analgesics consumption qualitatively, indicating no significant differences between treatment and control groups (Belch 2011; Telles 1984).

The quality of the evidence regarding this outcome is low owing to high risk of bias and imprecision, and a small number of events did not reach the optimal information size.

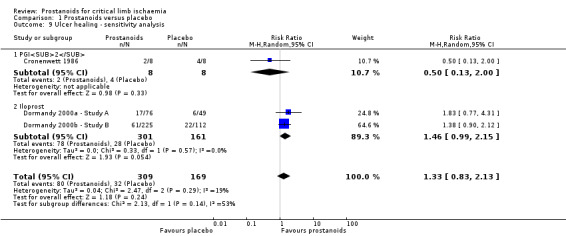

Ulcer healing

We found 13 studies that reported ulcer healing. We excluded two studies from meta‐analysis: one because it included only diabetic patients with a significant proportion of neuropathic and microangiopathic ulcers and therefore represented a clinically different population from other studies (Brock 1990), and the other because investigators measured ulcer healing as a continuous outcome (Belch 2011).

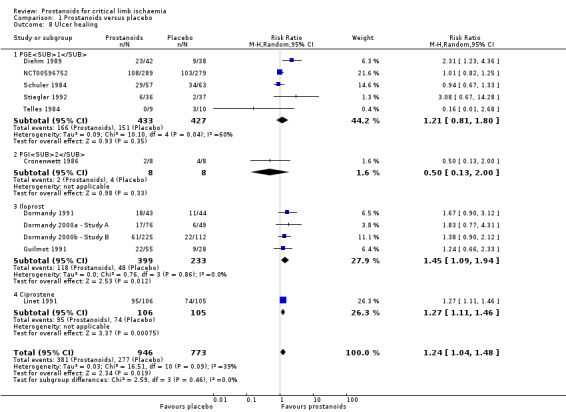

We included the remaining 11 studies in a random‐effects meta‐analysis (five studies on PGE1 (Diehm 1989; NCT00596752; Schuler 1984; Stiegler 1992; Telles 1984), one on PGI2 (Cronenwett 1986), four on iloprost (Dormandy 1991; Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B; Guilmot 1991), and another on ciprostene (Linet 1991)). As subgroup analysis revealed no differences between high‐dose and low‐dose iloprost against placebo for this outcome (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.07, df = 1 (P = 0.80), I² = 0%), we presented data from the two studies combined (Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B). Pooled results show that 381/946 participants in the prostanoid group and 277/773 in the placebo group had some degree of ulcer healing (RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.48; 11 studies; I² = 39%; Analysis 1.8). Subgroup analysis by type of prostanoid revealed no differences for this outcome (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 2.59, df = 3 (P = 0.46), I² = 0%).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Prostanoids versus placebo, Outcome 8 Ulcer healing.

We performed sensitivity analysis excluding eight studies at high risk of attrition bias (Diehm 1989; Dormandy 1991; Guilmot 1991; Linet 1991; NCT00596752; Schuler 1984; Stiegler 1992; Telles 1984), which showed an influence on overall effect (RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.83 to 2.13; 478 participants; I² = 19%). Estimates lost precision, resulting in a wider confidence interval that included both appreciable benefit and harm. Therefore, the quality of this evidence is moderate (see Table 1).

Belch 2011 reported that the group of participants receiving taprostene experienced no significant decrease in median ulcer size (161 to 177 mm²), whereas participants in the placebo group experienced an increase in median ulcer size (201 to 292 mm²) by the end of the infusion period.

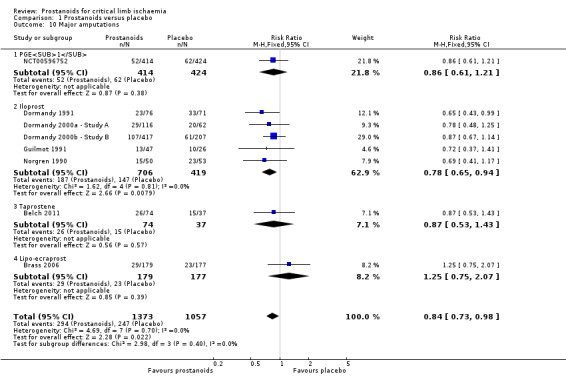

Major amputation

Eight studies reported major amputations (one on PGE1 (NCT00596752), five on iloprost (Dormandy 1991; Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B; Guilmot 1991; Norgren 1990), one on taprostene (Belch 2011), and one on lipo‐ecraprost (Brass 2006)). As subgroup analysis revealed no differences between high‐dose and low‐dose iloprost against placebo for this outcome (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.01, df = 1 (P = 0.93), I² = 0%), we presented data from the two studies combined (Dormandy 2000a ‐ Study A; Dormandy 2000b ‐ Study B).

A fixed‐effect meta‐analysis showed that 294/1373 participants in the prostanoid group and 247/1057 in the placebo group experienced this event (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.98; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.10). Subgroup analysis by type of prostanoid revealed no differences for major amputations (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 2.98, df = 3 (P = 0.40), I² = 0%).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Prostanoids versus placebo, Outcome 10 Major amputations.