Abstract

Background

People experiencing psychosis may become aggressive. Antipsychotics, such as aripiprazole in intramuscular form, can be used in such situations.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of intramuscular aripiprazole in the treatment of psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation).

Search methods

On 11 December 2014 and 11 April 2017, we searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Study‐based Register of Trials which is based on regular searches of CINAHL, BIOSIS, AMED, Embase, PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and registries of clinical trials.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that randomised people with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation to receive either intramuscular aripiprazole or another intramuscular intervention.

Data collection and analysis

We independently inspected citations and, where possible, abstracts, ordered papers and re‐inspected and quality assessed these. We included studies that met our selection criteria. At least two review authors independently extracted data from the included studies. We chose a fixed‐effect model. We analysed dichotomous data using risk ratio (RR) and the 95% confidence intervals (CI). We analysed continuous data using mean differences (MD) and their CIs. We assessed risk of bias for included studies and used GRADE to create 'Summary of findings' tables.

Main results

Searching found 63 records referring to 21 possible trials. We could only include three studies, all completed over the last decade, with 885 participants, of which 707 were included for quantitative analyses in this systematic review. Due to limited comparisons, small size of trials and a paucity of investigated and reported 'pragmatic' outcomes, evidence was mostly graded as low or very low quality. No trials reported useful data for one of our primary outcomes of tranquil or asleep by 30 minutes. Economic outcomes were also not reported in the trials.

When compared with placebo, fewer people in the aripiprazole group needed additional injections compared to the placebo group (2 RCTs, n = 382, RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.85, very low‐quality evidence). Clinically important improvement in agitation at two hours favoured the aripiprazole group (2 RCTs, n = 382, RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.92, very low‐quality evidence). The numbers of non‐responders after the first injection also favoured aripiprazole (1 RCT, n = 263, RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.71, low‐quality evidence). Although no effect was found, more people in the aripiprazole compared to the placebo group experienced adverse effects (1 RCT, n = 117, RR 1.51, 95% CI 0.93 to 2.46, very low‐quality evidence).

Aripiprazole required more injections compared to haloperidol (2 RCTs, n = 477, RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.63, very low‐quality evidence), with no significant difference in agitation (2 RCTs, n = 477, RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.11, very low‐quality evidence), and similar non‐responders after first injection (1 RCT, n = 360, RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.79, low‐quality evidence). Aripiprazole and haloperidol did not differ when taking into account the overall number of people that experienced at least one adverse effect (1 RCT, n = 113, RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.35, very low‐quality evidence).

Compared to aripiprazole, olanzapine was better at reducing agitation (1 RCT, n = 80, RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.99, low‐quality evidence) and had a more favourable effect on global state change scores (1 RCT, n = 80, MD 0.58, 95% CI 0.01 to 1.15, low‐quality evidence), both at two hours. No differences were found in terms of experiencing at least one adverse effect during the 24 hours after treatment (1 RCT, n = 80, RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.24, very low‐quality evidence). However, participants allocated to aripiprazole experienced less somnolence (1 RCT, n = 80, RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.82, low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

The available evidence is of poor quality but there is some evidence aripiprazole is effective compared to placebo and haloperidol, but not when compared to olanzapine. However, considering that evidence comes from only three studies, caution is required in generalising these results to real‐world practice. This review firmly highlights the need for more high‐quality trials on intramuscular aripiprazole in the management of people with acute aggression or agitation.

Plain language summary

How effective is aripiprazole for calming people who are aggressive or agitated due to psychosis?

Background People with psychosis may experience hearing voices (hallucinations) or abnormal thoughts (delusions) which can make them frightened, distressed and agitated (restless, excitable or irritable). Experiencing such emotions can sometimes result in behaviour that is aggressive or violent. This poses a challenge and dilemma for mental health professionals who have to diagnose and, often quickly, give the best available treatment to prevent those who are aggressive, harming themselves or others.

Aripiprazole is a medication that can be used to treat psychosis and also calm people who are aggressive or agitated due to psychosis. It can be taken by mouth or by injection (intramuscular). However, aripiprazole can also cause unpleasant side effects such as headaches, upset stomach, and excessive sleepiness or drowsiness.

This review looks for evidence from randomised controlled trials that assesses the effectiveness of intramuscular aripiprazole for people who are agitated and aggressive as a result of having psychosis.

Searching The Information Specialist of the Cochrane Schizophrenia group ran an electronic search in 2014 and in 2017 for studies randomising adults with aggression due to psychosis to receive either injections of aripiprazole or injections of a placebo (dummy treatment) or injections of another antipsychotic. The search found 63 relevant records, referring to 21 trials. Review authors screened these records for inclusion or exclusion.

Main results Only three studies could be included. Evidence is limited due to the small number of trials and poor quality of data reported. Fewer people receiving aripiprazole required more injections to become calm than those receiving placebo or haloperidol. Overall, aripiprazole caused a similar number of adverse effects to placebo or haloperidol. Compared to olanzapine, aripiprazole was less effective at calming people but caused less sleepiness or drowsiness

Conclusions Some evidence is available, but is of poor quality, and it is difficult to make conclusions about aripiprazole's effectiveness from such data. Health professionals and people with mental health problems are therefore left without clear guidance concerning use of aripiprazole as a rapid tranquilliser. More research is needed to help people consider which medication is better at calming people down, has fewer adverse effects, and works quickly and rapidly.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Aggression and agitation are psychiatric emergencies that can often be associated with psychosis, substance misuse or epilepsy (Tardiff 1982). Aggression is described as hostile, injurious, or destructive behaviour, and can occur in about 3% of psychiatric outpatients (Tardiff 1985) and in up to 7% to 10% of inpatient settings. Agitation is described as a state of troubled mind or feelings (Makins 1994) and is characterised by restlessness, excitability and irritability, and for some people, this can result in verbal and physical aggressive behaviour (Mohr 2005). As is often the case, patients experiencing these episodes find new environments stressful and become aggressive (Ferracuti 1993). Aggression and agitation within the psychiatric setting imposes a significant challenge to clinicians who, while attempting to make an accurate diagnosis and formulation (Schleifer 2011), have to intervene quickly in order to manage the risk that the service user may present to themselves, other service users and staff (NICE 2015).

There have been numerous national and international guidelines that created protocols for managing people with aggression and violence (APA 2006; CPA 2005; NICE 2015). Some evidence from these guidelines may be conflicting in nature. For example, the use of zuclopenthixol acetate is not recommended by NICE, but recommended by Australian and Canadian guidelines. This is not surprising as there has only been one trial of zuclopenthixol acetate in this area and the small sample size from this trial could lead to varied interpretations. An individual requiring rapid tranquillisation is frequently unable or unwilling to consent and the treatment is being provided in his or her best interest.

In the UK, NICE guidelines recommend that a comprehensive risk assessment is the first step in management of aggression and non‐pharmacological methods recommended for use include de‐escalation, physical restraints and seclusion. Where rapid tranquillisation through oral therapy is refused, is not indicated by previous clinical response, is not a proportionate response, or is ineffective, administration of an intramuscular combination of haloperidol and promethazine or intramuscular lorazepam is recommended (NICE 2015).

In the USA, the first intervention involves staff members talking to the patient in an attempt to calm him or her. Attempts to restrain the patient should be done only by a team trained in safe restraint procedures to minimise risk of harm to patients or staff. Antipsychotics and benzodiazepines are often helpful in reducing the patient’s level of agitation. If the patient will take oral medication, rapidly dissolving forms of olanzapine and risperidone can be used for quicker effect and to reduce non adherence. If a patient refuses oral medication, most states allow for emergency administration despite the patient’s objection. Short‐acting parenteral formulations of first‐ and second‐generation antipsychotic agents (e.g. haloperidol, ziprasidone, and olanzapine), with or without a parenteral benzodiazepine (e.g. lorazepam), are available for emergency administration in acutely agitated patients (APA 2006).

There have been only a handful of surveys looking at the prevalence and practices in managing acute agitation. Cunane 1994 found that in the UK, clinicians preferred using chlorpromazine, whereas Binder 1999 found that in the USA, clinicians preferred a combination of haloperidol and benzodiazepines. In a more recent survey, Huf 2002a found that Brazilian psychiatrists preferred a combination of haloperidol and promethazine. Surveys of this nature are notoriously difficult to conduct specially in resource‐poor settings, which partly explains the paucity of such surveys from low‐income countries. There have been a few good quality pragmatic trials comparing various interventions such as haloperidol, olanzapine, promethazine, benzodiazepines including lorazepam and midazolam, and other medications for managing acute agitation (Alexander 2004; Huf 2002b; Raveendran 2007).

Description of the intervention

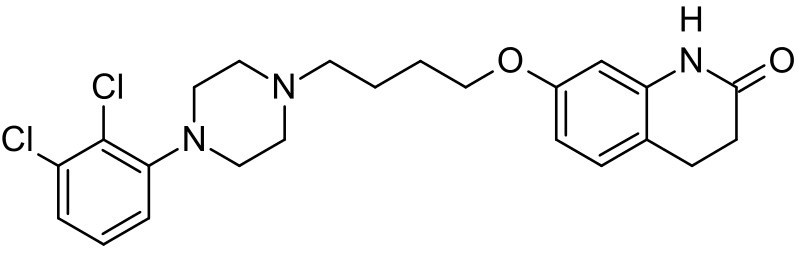

Aripiprazole is a quinolinone derivative, 7‐[4‐[4‐(2,3‐dichlorophenyl)‐1‐piperazinyl]butoxy]‐3,4‐dihydrocarbostyril (Kikuchi 1995; Figure 1). It is available as oral tablets, orally disintegrating tablets, oral solution and intramuscular injections. The intramuscular preparations are available in single‐dose vials as a ready‐to‐use, 9.75 mg/1.3 mL (7.5 mg/mL) clear, colourless, sterile, aqueous solution. Inactive ingredients for this solution include 150 mg/mL of sulfobutylethercyclodextrin (SBECD), tartaric acid, sodium hydroxide and water for injection (Abilify 2017). Intramuscular aripiprazole seems to have two medians for peak plasma concentrations, one at one hour and the second at three hours. It has 100% bioavailability and the pharmacokinetics is linear over a dose range of 1 mg to 45 mg. It is likely to be eliminated by the liver using the P450 system of isoenzymes (CYP2D6 and CYP3A4, Abilify 2017).

1.

Aripiprazole structure

Aripiprazole solution, for injection, is licensed for rapid control of agitation and disturbed behaviours in adults when oral therapy is not appropriate. The dose for adults is 9.75 mg (1.3 mL) as a single intramuscular injection initially with an effective dose range of 5.25 mg to 15 mg as a single injection. Second injections can be administered two hours after the first, No more than three injections should be given in any 24‐hour period.

How the intervention might work

According to treatment guidelines, aripiprazole is classified amongst the second‐generation antipsychotics with amisulpride, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, sertindole, ziprasidone and zotepine. However, aripiprazole has been described as the prototype of a new and third generation of antipsychotics, the so called 'dopamine‐serotonin system stabilisers' (McGavin 2002; Swainston Harrison 2004).

It is reported to exert its antipsychotic effects by acting as a partial agonist at dopamine D2 and 5‐HT1A receptors and antagonist activity at 5‐HT2A receptors (Shapiro 2003). It has been postulated that through dopamine and serotonin system stabilisation, a partial D2 agonist would be able to act as an antagonist in pathways where an abundance of dopamine was leading to 'psychosis', yet it would stimulate receptors as an agonist at sites in which low‐dopaminergic tone would produce adverse effects.

Aripiprazole, however, also has an affinity to other receptors including D3, D4, 5‐HT2c, 5HT7, alpha‐1 adrenergic and histamine receptors, which could be related to some adverse effects (such as headache, gastrointestinal upset, headedness, somnolence; FDA 2004). The recommended target dose for aripiprazole is 10 mg to 15 mg per day (dose range 10 mg to 30 mg/day). Phase III trials were initially conducted in Japan in 1995 and the drug was granted Approved Status by the FDA (USA) on the 15 November 2002 for the treatment of schizophrenia. Aripiprazole has since been licensed in most countries worldwide.

Why it is important to do this review

Aripiprazole has been around since 2002 and its use has been gradually increasing in the UK. Recent data state that for aripiprazole the spending on NHS prescriptions in England was about £6m in 2008, about £10m in 2010, rising to £15m in 2013 (NHS 2014). An intramuscular formulation of aripiprazole has recently been licensed for use in treatment of acute agitation. The increase in prescribing costs of oral aripiprazole seems to be in keeping with the general increase in atypical antipsychotic prescribing in the UK. If previous trends are to go by, we could expect a general increase in cost of intramuscular aripiprazole use to the UK's NHS over the next few years. In terms of raw cost data, there are considerable differences between the older generation and newer generation of antipsychotics. For example, in the UK a vial of haloperidol 5 mg/mL costs 30 pence, a vial of promethazine 25 mg/mL 70 pence, whereas, a vial of olanzapine 5 mg/mL about £3.48, and finally a vial of aripiprazole 9.75 mg costs £3.43 in the UK (BNF 2014).

With the increasing number of the antipsychotic medications that are available for intramuscular use and treatment of acute agitation, there is an urgent need to systematically review and evaluate the effects of intramuscular aripiprazole. This is one of a series of similar reviews (Table 4).

1. Other relevant Cochrane reviews.

| Focus of review | Reference |

| Completed and maintained reviews | |

| 'As required' medication regimens for seriously mentally ill people in hospital | Douglas‐Hall 2015 |

| Benzodiazepines for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | Gillies 2015 |

| Chlorpromazine for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | Ahmed 2010 |

| Clotiapine for acute psychotic illnesses | Berk 2004 |

| Containment strategies for people with serious mental illness | Muralidharan 2006 |

| De‐escalation techniques for psychosis‐induced aggression | Du 2017 |

| Droperidol for acute psychosis | Khokhar 2016 |

| Haloperidol for long‐term aggression in psychosis | Khushu 2016 |

| Haloperidol for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation) | Ostinelli 2017 |

| Haloperidol plus promethazine for psychosis‐induced aggression | Huf 2016 |

| Olanzapine IM or velotab for acutely disturbed/agitated people with suspected serious mental illnesses | Belgamwar 2005 |

| Seclusion and restraint for serious mental illnesses | Sailas 2000 |

| Zuclopenthixol acetate for acute schizophrenia and similar serious mental illnesses | Jayakody 2012 |

| Reviews in the process of being completed | |

| Risperidone for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | Ahmed 2011 |

| Loxapine inhaler for psychosis‐induced aggression | Vangala 2012 |

| Clozapine for people with psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | Toal 2012 |

| Quetiapine for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation | Wilkie 2012 |

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of intramuscular aripiprazole in the treatment of psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised control trials. If a trial was described as ’double‐blind’ but implied randomisation, we included such trials in a sensitivity analysis (see Sensitivity analysis). If their inclusion did not result in a substantive difference, they remained in the analyses. If their inclusion resulted in statistically significant differences, we did not add the data from these lower‐quality studies to the results of the better trials, but presented such data within a subcategory. We planned to exclude quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by alternate days of the week or where allocation was undertaken on surname.

Types of participants

People exhibiting aggression or agitation (or both) thought to be due to psychosis, regardless of age and sex. Should studies have involved people with other diagnoses, such as drug or alcohol intoxication, organic problems including dementia, non‐psychotic mental illnesses or learning disabilities, we would have included these as long as the majority of participants (> 50%) were experiencing psychosis.

Types of interventions

1. Aripiprazole

Given alone, intramuscularly in any dose.

versus:

A. Other antipsychotic medications

Given alone, intramuscularly in any dose.

B. Placebo

Active or non‐active, intramuscular, in any dose.

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes grouped by time: by 30 minutes, up to two hours, up to four hours, up to 24 hours, and over 24 hours.

We endeavoured to report binary outcomes recording clear and clinically meaningful degrees of change (e.g. global impression of much improved, or more than 50% improvement on a rating scale ‐ as defined within the trials) before any others. Thereafter, we listed other binary outcomes and then those that were continuous.

Primary outcomes

1. Tranquil or asleep

1.1 Tranquil or asleep ‐ by up to 30 minutes *

2. Repeated need for rapid tranquillisation

Secondary outcomes

1. Tranquillisation or asleep

1.1 Tranquil or asleep ‐ over 30 minutes * 1.2 Time to tranquillisation/sleep 1.3 Time to tranquillisation 1.4 Time to sleep

2. Specific behaviours

2.1 Self‐harm, including suicide 2.2 Injury to others 2.3 Agitation 2.3.1 Another episode of agitation by 24 hours 2.3.2 Clinically important change in agitation * 2.3.3 Any change in agitation 2.3.4 Average endpoint score ‐ agitation scales 2.3.5 Average change score ‐ agitation scales 2.4 Aggression 2.4.1 Another episode of aggression by 24 hours 2.4.2 Clinically important change in aggression * 2.4.3 Any change in aggression 2.4.4 Average endpoint score ‐ aggression scales 2.4.5 Average change score ‐ aggression scales

3. Global state

3.1 Overall improvement 3.2 Use of additional medication 3.3 Use of restraints/seclusion 3.4 Relapse ‐ as defined by each study 3.5 Recurrence of violent incidents 3.6 Needing extra visits from the doctor 3.7 Refusing oral medication

4. Service use

4.1 Duration of hospital stay 4.2 Re‐admission 4.3 Clinically important engagement with services 4.4 Any engagement with services 4.5 Average endpoint engagement score 4.6 Average change in engagement scores

5. Mental state

5.1 Clinically important change in general mental state 5.2 Any change in general mental state 5.3 Average endpoint general mental state score 5.4 Average change in general mental state scores

6. Adverse effects

6.1 Death 6.2 Any general adverse effects 6.3 Any serious specific adverse effects 6.4 Average endpoint general adverse effect score 6.5 Average change in general adverse effect scores 6.6 Clinically important change in specific adverse effects 6.7 Any change in specific adverse effects 6.8 Average endpoint specific adverse effects 6.9 Average change in specific adverse effects

7. Leaving the study early

7.1 For specific reasons 7.2 For general reasons

8. Satisfaction with treatment

8.1 Recipient of treatment satisfied with treatment 8.2 Recipient of treatment average satisfaction score 8.3 Recipient of treatment average change in satisfaction scores 8.4 Informal treatment provider satisfied with treatment 8.5 Informal treatment providers' average satisfaction score 8.6 Informal treatment providers' average change in satisfaction scores 8.7 Professional providers satisfied with treatment 8.8 Professional providers' average satisfaction score 8.9 Professional providers' average change in satisfaction scores

9. Acceptance of treatment

9.1 Accepting treatment 9.2 Average endpoint acceptance score 9.3 Average change in acceptance scores

10. Quality of life

10.1 Clinically important change in quality of life * 10.2 Any change in quality of life * 10.3 Average endpoint quality of life score 10.4 Average change in quality of life score 10.5 Clinically important change in specific aspects of quality of life * 10.6 Any change in specific aspects of quality of life * 10.7 Average endpoint specific aspects of quality of life 10.8 Average change in specific aspects of quality of life

10. Economic outcomes

10.1 Direct costs 10.2 Indirect costs

Outcomes used for 'Summary of findings' tables

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2011) and used the GRADEpro GDT web application to export data from this review to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important to patient‐care and decision‐making. We selected the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

1. Tranquillisation or asleep ‐ by 30 minutes. 2. Repeated need for rapid tranquillisation ‐ within 24 hours. 3. Specific behaviours ‐ agitation or aggression. 4. Global state ‐ clinically important overall improvement *. 5. Adverse effects ‐ any serious, specific adverse effects. 6. Economic outcomes

Search methods for identification of studies

No language restriction was applied within the limitations of the search tools.

Electronic searches

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Study‐Based Register of Trials

On 11 December 2014 and 11 April 2017, the Information Specialist searched the register using the following search strategy:

(*Aripiprazole*) in Intervention AND (*Aggress* or *Violent* or *Agitation* or *Tranq*) in Healthcare Condition Fields of Study

In such study‐based register, searching the major concept retrieves all the synonyms and relevant studies because all the studies have already been organised based on their interventions and linked to the relevant topics.

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (including AMED, BIOSIS, CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and registries of clinical trials) and their monthly updates, handsearches, grey literature, and conference proceedings (see Group’s Module). There is no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected references of all included studies for further relevant studies.

2. Personal contact

Where necessary, we attempted to contact the first author of each included study for information regarding unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the 2014 search, review authors SJ, and KS independently inspected citations from the searches and identified relevant abstracts. A random 20% sample was independently re‐inspected by SS to ensure reliability. Where disputes arose, the full report was acquired for more detailed scrutiny. SJ and KS obtained and inspected full reports of the abstracts meeting the review criteria. If it had not been possible to resolve disagreement by discussion, we would have attempted to contact the authors of the study for clarification.

For the 2017 search, review author EGO independently inspected citations and identified relevant abstracts. EGO also re‐inspected the results of the 2014 search.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

For the 2014 search, review author JS extracted data from all included studies. In addition, to ensure reliability, review authors KS and SS independently extracted data from a random sample of these studies, comprising 10% of the total. We would have discussed any disagreement, documented decisions and, if necessary, contacted authors of studies. We extracted data presented only in graphs and figures whenever possible, but included only if two review authors independently had the same result. We attempted to contact authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain missing information or for clarification whenever necessary.

For the 2017 search, review author EGO extracted data from the new included study and re‐inspected the data extraction from previously included studies.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We extracted data onto standard, simple forms.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if: a) the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and b) the measuring instrument had not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial; c) the instrument should be a global assessment of an area of functioning and not sub‐scores which are not, in themselves, validated or shown to be reliable, however there are exceptions; we included sub‐scores from mental state scales measuring positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

Ideally, the measuring instrument should either be i. self‐report or ii. completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly, therefore, in Description of studies we noted if this was the case or not.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint), which can be difficult in unstable and difficult to measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided primarily to use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were not available. We combined endpoint and change data in the analysis and we used mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences (SMD) throughout (Deeks 2011).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we aimed to apply the following standards to all data before inclusion:

a) standard deviations (SDs) and means are reported in the paper or obtainable from the authors;

b) when a scale starts from the finite number zero, the SD, when multiplied by two, is less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, (Altman 1996; Higgins 2011);

c) if a scale started from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), (Kay 1986)), which can have values from 30 to 210), the calculation described above was modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2 SD > (S‐ S min), where S is the mean score and ’S min’ is the minimum score.

Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied. Skewed data pose less of a problem when looking at means if the sample size is large (> 200) and we entered these into the syntheses. We planned to present skewed data from studies of less than 200 participants in ‘Additional tables’ rather than in analyses.

When continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not. These data were entered into analyses.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, we made efforts to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the PANSS (Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005; Leucht 2005a). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicates a favourable outcome for aripiprazole is effective for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation. Where keeping to this makes it impossible to avoid outcome titles with clumsy double‐negatives (e.g. 'Not un‐improved'), we reported data where the left of the line indicates an unfavourable outcome. This is noted in the relevant graphs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Review authors EGO and JS assessed risk of bias by using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a) to assess trial quality. This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. We noted the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review and in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes, we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). The number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome/number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome(NNTB/NNTH) statistic with its confidence intervals is intuitively attractive to clinicians but is problematic both in its accurate calculation in meta‐analyses and interpretation (Hutton 2009). For binary data presented in the 'Summary of findings' tables, where possible, we calculated illustrative comparative risks.

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes we estimated mean difference (MD) between groups. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (SMD). However, if scales of very considerable similarity had been used, we would have presumed there was a small difference in measurement, and calculated the effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

If clustering was not been accounted for in primary studies, we would have presented data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. We would have attempted to contact the first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999).

If clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we would have reported these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

Cochrane Schizophrenia have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC is not reported, it is assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999). Where cluster studies are appropriately analysed taking into account ICCs, and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would be possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason, cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, we would have only used data from the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, where relevant, we presented the additional treatment arms in separate comparisons. If data were binary, we simply added and combined within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous, we combined data following the formula in section the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If the additional treatment arms had not been relevant, we would not have reproduced such data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). We chose that, for any particular outcome, should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for, we would not reproduce these data or use them within analyses (except for the outcome 'leaving the study early'). When more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we addressed this within the 'Summary of findings' tables by down‐grading quality.

2. Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50% and where these data were not clearly described, we presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat analysis, ITT). Those leaving the study early were all assumed to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed, with the exception of the outcome of death and adverse effects. For these outcomes, we used the rate of those who stayed in the study ‐ in that particular arm of the trial ‐ for those who did not. We undertook a sensitivity analysis to test how prone the primary outcomes were to change when 'completer' data only were compared to the ITT analysis using the above assumptions.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

In the case where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50% and 'completer'‐data were reported, we reproduced these.

3.2 Standard deviations (SDs)

If SDs were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and confidence intervals were available for group means, and either 'P' value or 't' values were available for differences in mean, we would have calculated them according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). When only the SE are reported, SDs can be calculated by the formula SD = SE * square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) present detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P values, t or F values, confidence intervals, ranges or other statistics. If these formulae do not apply, we could calculate the SDs according to a validated imputation method which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information. We would have examined the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

3.3 Assumptions about participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up

Various methods are available to account for participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up. Some trials just present the results of study completers, others use the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF), while more recently methods such as multiple imputation or mixed‐effects models for repeated measurements (MMRM) have become more of a standard. While the latter methods seem to somewhat better than LOCF (Leon 2006), we feel that the high percentage of participants leaving the studies early and differences in the reasons for leaving the studies early between groups could be often the core problem in randomised schizophrenia trials. We therefore did not exclude studies based on the statistical approach used. However, preferably we used the more sophisticated approaches, e.g. we preferred MMRM or multiple‐imputation to LOCF and only presented completer analyses if some kind of ITT data were not available at all; this issue was addressed in the item 'incomplete outcome data' of the 'Risk of bias' tool.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations which we had not predicted would arise. If such situations or participant groups had arisen, we would have discussed them.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods which we had not predicted would arise. If such methodological outliers had arisen, we would have discussed them.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I2 statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I2 statistic alongside the Chi2 'P' value. The I2 statistic provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on i. magnitude and direction of effects and ii. strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. 'P' value from Chi2 test, or a CI for I2). We interpreted an I2 estimate greater than or equal to around 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 statistic, as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Chapter 9. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions) (Deeks 2011). If substantial levels of heterogeneity had been found in the primary outcome, we planned to explore reasons for heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Chapter 10. of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2011).

1. Protocol versus full study

We tried to locate protocols of included randomised trials. If the protocol was available, we compared outcomes in the protocol and in the published report . If the protocol was not available, we compared outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial report with actually reported results.

2. Funnel plot

We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We decided that we would not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar size. In future, where funnel plots are possible, we will seek statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. There is, however, a disadvantage to the random‐effects model: it puts added weight onto small studies which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We chose fixed‐effect model for all analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses

1.1 Primary outcomes

We did not anticipate any subgroup analyses.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

If inconsistency was high, we reported it. First, we investigated whether data were entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, we visually inspected the graph and successfully removed outlying studies to see if homogeneity was restored. For this review, we decided that should this occur with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than around 10% of the total weighting, we would present such data. If not, we would not pool data, but would discuss this issue. We know of no supporting research for this 10% cut‐off but are investigating use of prediction intervals as an alternative to this unsatisfactory state. When unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity were obvious, we stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We did not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

1. Implication of randomisation

We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way as to imply randomisation. For the main outcomes of interest, we we would have included these studies and if there was no substantive difference when the implied randomised studies were added to those with better description of randomisation, then we would have used all relevant from data these studies.

2. Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the main outcomes of interest when we used our assumption compared with 'completer' data only. Where there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption. Where assumptions had to be made regarding missing SDs data (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the main outcomes of interest when we used our assumption compared with 'completer' data only. We undertook a sensitivity analysis to test how prone results were to change when 'completer' data only were compared to the imputed data using the above assumption. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

3. Risk of bias

We analysed the effects of excluding trials that were judged to be at high risk of bias across one or more of the domains of randomisation (see Assessment of reporting biases). If the exclusion of trials at high risk of bias did not substantially alter the direction of effect or the precision of the effect estimates, then we included data from these trials in the analyses.

4. Imputed values

We also would have undertaken a sensitivity analysis to assess the effects of including data from trials if we had used imputed values for ICC in calculating the design effect in cluster‐randomised trials.

If substantial differences were noted in the direction or precision of effect estimates in any of the sensitivity analyses listed above, we did not pool data from the excluded trials with the other trials contributing to the outcome, but presented them separately.

5. Fixed and random effects

All data were synthesised using a fixed‐effect model; however, we also synthesised data for the main outcomes using a random‐effects model to evaluate whether this altered the significance of the results.

Results

Description of studies

For substantive descriptions of studies please see Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

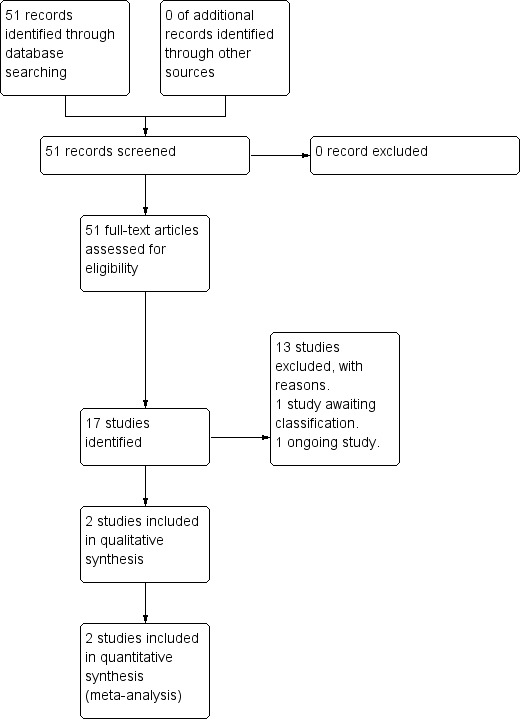

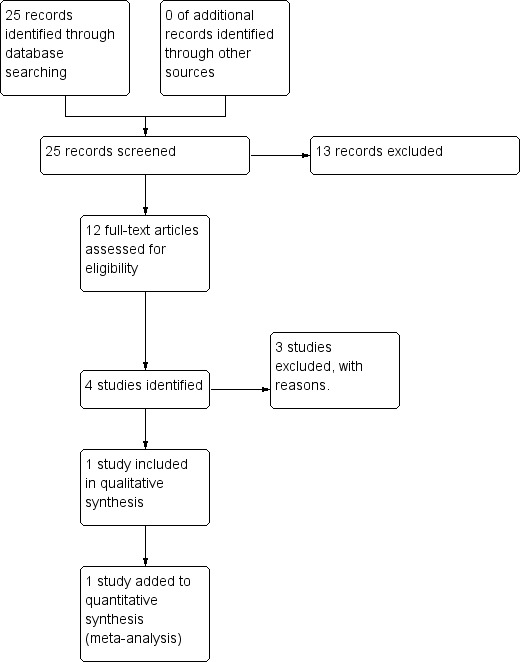

The electronic search (December 2014) yielded 51 citations of potentially eligible studies. We obtained 51 full‐text papers, related to 17 different studies (two included studies, 13 excluded, one awaiting classification, one ongoing study, Figure 2). The last search (April 2017) yielded 25 citations of potentially eligible studies, with 13 of those already cited in the previous search; therefore, we obtained and closely inspected 12 new full‐text papers related to four studies (one study included, three studies excluded, Figure 3).

2.

Study flow diagram (2014 search).

3.

Study flow diagram (2017 search).

Included studies

Details of the three studies included in the review are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

1. Length of studies

The duration of the studies, limited to intramuscular (IM) intervention phase, was up to 24 hours (Andrezina 2006, Bristol‐Myers 2005; Kittipeerachon 2016).

2. Participants

A total number of 707 patients were considered for this review; please note that for Bristol‐Myers 2005, the participants reported below refer to those allocated to selected comparisons only (placebo, aripiprazole 9.75 mg, haloperidol).

2.1 Clinical state

Participants in the trials presented with acute aggression or agitation due to psychosis and therefore were deemed by the treating clinician to be appropriate candidates for IM rapid tranquillisation therapy.

2.2 Diagnosis

Overall, 526 (74.4%) of participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, 176 (24.9%) of schizoaffective disorder, and 5 (0.7%) of schizophreniform disorder.

2.3 Exclusion

Exclusion criteria in Andrezina 2006 and Bristol‐Myers 2005 studies were similar: psychoactive substance dependence within two months of the study start, significant risk of committing suicide, neurologic condition, psychiatric condition requiring pharmacotherapy other than those included, significant medical condition, known non‐responders to antipsychotic medication; PANSS (Excited Component (PEC) score ≥ 32; in Andrezina 2006, schizophreniform disorder was considered an exclusion criteria, whilst in Bristol‐Myers 2005 it was not.Kittipeerachon 2016, a more pragmatic randomised controlled trial (RCT), had less restrictive exclusion criteria: known allergy to aripiprazole or olanzapine, pregnancy or breastfeeding.

2.4 Age

Age range was of 18‐69 years in Andrezina 2006, 18‐66 years in Bristol‐Myers 2005, and 18‐65 years in Kittipeerachon 2016.

2.5 Sex

Participants of the studies involved in this review were 435 men (61.5%) and 272 women (38.5%).

3. Study size

The total number of participants randomised was 805 (Andrezina 2006, n = 448; Bristol‐Myers 2005, n = 357, of which 179 were considered for comparisons; Kittipeerachon 2016, n = 80).

4. Setting

All the included studies were located in emergency room departments and subsequently in hospital, involving newly admitted patients.

5. Interventions

5.1 Aripiprazole IM

Data in this systematic review relate to the 9.75 mg dose of aripiprazole for all the studies (Andrezina 2006; Bristol‐Myers 2005; Kittipeerachon 2016).

5.2 Placebo IM

Both Andrezina 2006 and Bristol‐Myers 2005 used placebo given intramuscularly.

5.3 Haloperidol IM

Dosage varied from 6.5 mg (Bristol‐Myers 2005) to 7.5 mg (Andrezina 2006).

5.4 Olanzapine IM

Dosage was 10 mg (Kittipeerachon 2016).

6. Outcomes

Binary data concerning the repeated need for tranquillisation were available for Andrezina 2006 and Bristol‐Myers 2005 only, since in Kittipeerachon 2016 repeated administration of intervention drugs was prohibited by the methodological design; with respect to adverse effects, binary data were available for all the included trials. All the trials employed continuous scales to measure other clinical outcomes; in Andrezina 2006 and Bristol‐Myers 2005 continuous measurements for adverse effects were presented as means without standard deviations (SDs), standard error (SE) or confidence intervals (CIs), and therefore were unusable for quantitative analyses. The various rating scales, from which we were able to obtain usable data, are listed below:

6.1 Specific behaviour ‐ Agitation

a. Agitated Behavior Scale (ABS/CABS)

The ABS (Corrigan 1989), is a 14‐item scale used for measuring agitation levels. The ABS was originally designed to monitor agitated behaviour in the recovery period after stroke and there are three factor‐based sub scores: I. aggression; II. disinhibition; III. lability. High scores indicated higher levels of aggression.

b. Agitation calmness Evaluation scale (ACES)

The ACES (Breier 2001), is a single‐item rating scale developed by Eli Lilly and company. On this scale, 1 = 'marked agitation', 4 = 'normal', 9 = 'unable to be aroused'.

c. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale ‐ Excited Component (PANSS‐EC)

The PANSS‐EC (Montoya 2011) is a five‐item subscale of the PANSS scale (excitement, tension, hostility, uncooperativeness, and poor impulse control). As in the original scale, items are rated from one ('not present') to seven ('extremely severe'). Scores range from five to 35, with mean scores ≥ 20 indicating agitation. A high score indicates high levels of agitation.

6.2 Global state

a. Clinical Global Impression (CGI)

The CGl (Guy 1976) is not a diagnostic tool but rather, enables clinicians to quantify the severity of symptoms of any mental health problem at one point in time. Clinicians are then able to use this to track whether there has been any improvement or worsening of symptoms over time. A seven‐point rating scale is used with high scores indicating increased severity or less recovery.

b. Clinical Global Impression ‐ Severity (CGI‐S)

The CGI‐S (Guy 1976) requires clinicians to consider the severity of a person’s symptoms in relation to the clinicians past experience of people with the same diagnosis. Clinicians then have to give a rating from one (= 'normal') to seven (= 'extremely ill'). High scores indicate increased severity.

c. Clinical Global Impression ‐ Improvement (CGI‐I)

The CGI‐I (Guy 1976) enables clinicians to assess whether a person’s symptoms have improved or worsened following an intervention. Based on the clinicians judgement, a rating on a seven‐point scale is given from one (= 'very much improved') to seven (= 'very much worse'). Therefore, low scores indicate greater improvement.

6.3 Mental state

a. Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale was originally developed by Overall and Gorham (Overall 1962) as a 14‐item scale to measure the severity of a range of psychiatric symptoms, including psychosis. This rating scale items evolved over time and now consists of 24 items which can be rated on a seven‐point scale from ‘not present’ to ‘extremely severe’. A high score would suggest poor mental health. It is not clear for the majority of the studies included in this review, which version of the BPRS was used.

b. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)

The PANSS was developed and published by Kay, Flszbein and Opler (Kay 1987). The PANSS is designed as a brief interview, whereby the severity of 30 symptoms of schizophrenia can be assessed on a scale of one ('not present') to seven ('extremely severe'). A high score would indicate more severe symptoms. The PANSS can be divided into separate subscales by focusing on the statements relating to positive symptoms (e.g. hallucinations), negative symptoms (e.g. social withdrawal) or general psychopathology (e.g. anxiety and uncooperativeness).

6.4 Adverse effects

a. Udvalg for Kliniske Undersogelser (UKU) side effects rating scale

The UKU (Lingjaerde 1987) is a questionnaire that divides adverse effects into four general categories of symptoms: psychic, neurologic, autonomic, and miscellaneous; for each adverse effects, the interviewer is asked to assess the probability of causal relationship with psychotropic drugs.

b. Simpson‐Angus Scale (SAS)

The SAS (Simpson 1970) is a 10‐item scale which measures drug‐induced parkinsonism (extrapyramidal side effects). Each item is scored from zero to four. A high score would indicate increased levels of parkinsonism.

7. Missing outcomes

No studies evaluated satisfaction with care, acceptance of treatment, quality of life, or economic outcomes.

8. Funders

Andrezina 2006 and Bristol‐Myers 2005 studies received sponsorship from pharmaceutical companies.

Excluded studies

In total we excluded 16 studies. Of these, seven had to be excluded based on the characteristics of participants. These studies (Kane 2002; Cutler 2006; Fleischhacker 2009; Liang 2005; McEvoy 2007; Potkin 2003; Tandon 2006) were excluded because although participants were suspected to have psychosis, these people were not displaying an aggressive or agitated behaviour. Five studies had to be excluded because they involved oral administration of aripiprazole (Chen 2009; Kinon 2008; Li 2009; Liu 2012; Xie 2011) or the intramuscular administration of aripiprazole long acting (NCT01469039). Three studies (Bao 2007; Simpson 2010; Wang 2014) had to be excluded because the intervention medication was not aripiprazole alone.

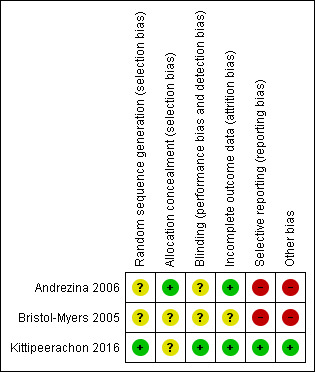

Risk of bias in included studies

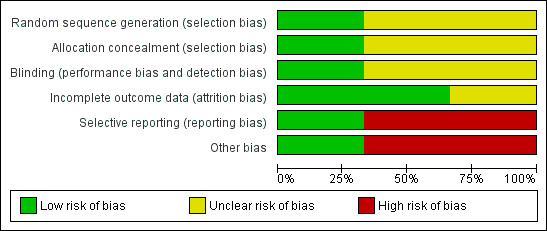

Although each ’Summary of findings’ table describes bias by outcome, an overview is reported here and a graphical impression is seen in Figure 4 and in Figure 5.

4.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

5.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

All included studies were described as randomised. In Andrezina 2006, the randomisation process is not stated (unclear sequence generation risk); however, allocation concealment was preserved by the utilisation of a centralised call‐in system (low allocation concealment risk). In Bristol‐Myers 2005 patients were randomly assigned in 1:1:1:1:1:1 ratio to the six arms of the study but no further information was provided regarding the process of randomisation; no details were provided regarding allocation concealment (overall unclear risk of selection bias). In Kittipeerachon 2016, the randomisation process is low risk as it is described as blindly picking the name of the assigned medication from a box with equal numbers of folded papers printed with each medication; allocation concealment management is not stated (unclear risk ).

Blinding

Andrezina 2006 is described as a double‐blinded study but no further details are provided (unclear risk of performance bias; unclear risk of detection bias). In the Bristol‐Myers 2005 study, authors stated double‐blinding but different dilution instructions for drug injections were provided, so no blinding was possible during the preparation of injections; in most cases the same person prepared and administered the drug (high risk of performance bias). To limit the magnitude of this bias, in the efficacy evaluations study investigators were blinded to treatment (low risk of detection bias), giving an overall unclear risk for blinding. In one case of medical emergency, the treating physician broke the blind design as knowledge of investigational product was considered to be critical to the patient management; however, investigators remained blinded. In Kittipeerachon 2016, patients and the physician investigator were blinded to treatment assignment.

Incomplete outcome data

Two included studies used a 'Last Observation Carried Forward' (LOCF) approach to manage missing data. In Andrezina 2006, there was no evidence of attrition bias (low risk of attrition bias). Concerning Bristol‐Myers 2005, reasons for leaving the study early were reported; however, number of participants completing different assessments at the same time point vary and reasons are not given (unclear risk of attrition bias). In Kittipeerachon 2016, procedures to manage missing data are not reported in the method section but no attritions were recorded throughout the trial (low risk of attrition bias).

Selective reporting

In both Andrezina 2006 and Bristol‐Myers 2005, adverse effects were reported only if they occurred in ≥ 5% of participants (high risk of reporting bias). In Kittipeerachon 2016, there was no evidence of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Both Andrezina 2006 and Bristol‐Myers 2005 were supported by manufacturers of one of the compared drugs (high risk of other bias). Kittipeerachon 2016 had no obvious risk of other bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings for the main comparison. ARIPIPRAZOLE (IM) compared to PLACEBO/NIL for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation).

| ARIPIPRAZOLE compared to PLACEBO/NIL for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation) | ||||||

| Patient or population: psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation) Setting: hospital Intervention: ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) Comparison: PLACEBO/NIL | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with PLACEBO/NIL | Risk with ARIPIPRAZOLE | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep | Not reported | |||||

| Repeated need for tranquillisation ‐ needing additional injections during 24 hours | Low | RR 0.69 (0.56 to 0.85) | 382 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2 | ||

| 250 per 1.000 | 173 per 1.000 (140 to 213) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 600 per 1.000 | 414 per 1.000 (336 to 510) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 750 per 1.000 | 518 per 1.000 (420 to 638) | |||||

| Specific behaviour: Agitation ‐ clinically important change (PANSS ‐EC reduction ≥ 40% from baseline) ‐ up to 2 hours | Low | RR 1.50 (1.17 to 1.92) | 382 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2 | ||

| 100 per 1.000 | 150 per 1.000 (117 to 192) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 350 per 1.000 | 525 per 1.000 (410 to 672) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 700 per 1.000 | 1000 per 1.000 (819 to 1.000) | |||||

| Global state: non‐responders to the first injection | Low | RR 0.49 (0.34 to 0.71) | 263 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | ||

| 200 per 1.000 | 98 per 1.000 (68 to 142) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 450 per 1.000 | 221 per 1.000 (153 to 320) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 700 per 1.000 | 343 per 1.000 (238 to 497) | |||||

| Adverse effects: one or more adverse events during 24 hours (only reported if occurred in ≥ 5% of people) | Study population | RR 1.51 (0.93 to 2.46) | 117 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2 | ||

| 295 per 1.000 | 446 per 1.000 (274 to 726) | |||||

| Economic outcomes | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' (downgraded by 1) ‐ randomisation procedure is not reported for both the included studies, and allocation concealment procedure is not consistently reported in Bristol‐Myers 2005. While for the 'randomisation' bias, studies are at least reported as 'randomised', as for the latter that allocation concealment was correctly handled could not be implied.

2 Indirectness: rated 'very serious' (downgraded by 2) ‐ participants included in the studies had levels of agitation not so pronounced by inclusion criteria, potentially under‐estimating or more likely over‐estimating true effectiveness.

Summary of findings 2. ARIPIPRAZOLE (IM) compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: a. HALOPERIDOL for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation).

| ARIPIPRAZOLE compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: a. HALOPERIDOL for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation) | ||||||

| Patient or population: psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation) Setting: hospital Intervention: ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) Comparison: OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: a. HALOPERIDOL | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: a. HALOPERIDOL | Risk with ARIPIPRAZOLE | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep | Not reported | |||||

| Repeated need for tranquillisation ‐ needing additional injections during 24 hours | Low | RR 1.28 (1.00 to 1.63) | 477 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2 | , | |

| 100 per 1.000 | 128 per 1.000 (100 to 163) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 300 per 1.000 | 384 per 1.000 (300 to 489) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 500 per 1.000 | 640 per 1.000 (500 to 815) | |||||

| Specific behaviour: Agitation ‐ clinically important change (PANSS ‐EC reduction ≥ 40% from baseline) ‐ up to 2 hours | Study population | RR 0.94 (0.80 to 1.11) | 477 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 ,2 | ||

| 576 per 1.000 | 541 per 1.000 (460 to 639) | |||||

| Global state: non‐responders to the first injection | Study population | RR 1.18 (0.78 to 1.79) | 360 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | ||

| 184 per 1.000 | 217 per 1.000 (143 to 329) | |||||

| Adverse effects: one or more adverse events during 24 hours (only reported if occurred in ≥ 5% of people) | Study population | RR 0.91 (0.61 to 1.35) | 113 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2 | ||

| 491 per 1.000 | 447 per 1.000 (300 to 663) | |||||

| Adverse effects: movement disorders ‐ EPS during 24 hours (only reported if occurred in ≥ 5% of people) | Low | RR 0.29 (0.12 to 0.70) | 471 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2 | ||

| 50 per 1.000 | 14 per 1.000 (6 to 35) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 100 per 1.000 | 29 per 1.000 (12 to 70) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 300 per 1.000 | 87 per 1.000 (36 to 210) | |||||

| Economic outcomes | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' (downgraded by 1) ‐ randomisation procedure is not reported for both the included studies, and allocation concealment procedure is not consistently reported in Bristol‐Myers 2005. While for the 'randomisation' bias studies are at least reported as 'randomised', as for the latter that allocation concealment was correctly handled could not be implied.

2 Indirectness: rated 'very serious' (downgraded by 2) ‐ participants included in the studies had levels of agitation not so pronounced by inclusion criteria, potentially under‐estimating or more likely over‐estimating true effectiveness.

Summary of findings 3. ARIPIPRAZOLE (IM) compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: b. OLANZAPINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation).

| ARIPIPRAZOLE compared to OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: b. OLANZAPINE for psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation) | ||||||

| Patient or population: psychosis‐induced aggression or agitation (rapid tranquillisation) Setting: hospital Intervention: ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) Comparison: OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: b. OLANZAPINE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: b. OLANZAPINE | Risk with ARIPIPRAZOLE | |||||

| Tranquillisation or asleep | Not reported | |||||

| Repeated need for tranquillisation | Not reported | |||||

| Specific behaviour: Agitation ‐ clinically important change (PANSS ‐EC reduction ≥ 40% from baseline) ‐ up to 2 hours | Low | RR 0.77 (0.60 to 0.99) | 80 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1, 3 | ||

| 500 per 1.000 | 385 per 1.000 (300 to 495) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 800 per 1.000 | 616 per 1.000 (480 to 792) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 900 per 1.000 | 693 per 1.000 (540 to 891) | |||||

| Global state: CGI‐S change score up to 2 hours | MD 0.58 (0.01 higher to 1.15 higher) | ‐ | 80 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 3 | ||

| Adverse effects: one or more adverse effects during 24 hours | Study population | RR 0.75 (0.45 to 1.24) | 80 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2, 3 | ||

| 500 per 1.000 | 375 per 1.000 (225 to 620) | |||||

| Adverse effects: somnolence during 24 hours | Low | RR 0.25 (0.08 to 0.82) | 80 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 3 | ||

| 100 per 1.000 | 25 per 1.000 (8 to 82) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 300 per 1.000 | 75 per 1.000 (24 to 246) | |||||

| High | ||||||

| 700 per 1.000 | 175 per 1.000 (56 to 574) | |||||

| Economic outcomes | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Imprecision ‐ rated 'serious' (downgraded by 1): Optimal Information Size (OIS) criterion is not met meaning that imprecision of effect estimates could not be properly handled.

2 Imprecision ‐ rated 'very serious' (downgraded by 2): Optimal Information Size (OIS) criterion is not met and CI overlaps no effect. High imprecision of effect estimates could not be properly excluded.

3 Indirectness ‐ rated 'serious' (downgraded by 1): attribution to the intervention drugs is suspected but can not be confirmed since in the study results it is showed that almost all the participants were administered with 'treatment as usual' drugs.

See Table 1; Table 2; Table 3. In the following section, the summary statistic for binary outcome results is reported as risk ratio (RR), and for continuous outcomes we used mean difference (MD). In all instances 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported.

1. COMPARISON 1. ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) versus PLACEBO/NIL

1.1 Repeated need for tranquillisation

Overall, significantly fewer participants allocated to aripiprazole needed additional injections during 24 hours, when compared to placebo (2 RCTs, n = 382, RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.85, very low‐quality evidence). Analyses for numbers needing one additional injection showed no differences between groups (1 RCT, n = 119, RR 1.38, 95% CI 0.69 to 2.80) but significantly more people receiving placebo required two additional injections (1 RCT, n = 119, RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.70, Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) vs PLACEBO/NIL, Outcome 1 Repeated need for tranquillisation.

1.2 Specific behaviour ‐ agitation

1.2.1 Clinically important change

Aripiprazole had an effect on agitation. At two hours more participants in the aripiprazole group showed a positive response for agitation (defined as a PANSS ‐ EC reduction of ≥ 40% from baseline, 2 RCTs, n = 382, RR 1.50. 95% CI 1.17 to 1.92, very low‐quality evidenceAnalysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) vs PLACEBO/NIL, Outcome 2 Specific behaviour: 1a. Agitation ‐ clinically important change (PANSS‐EC reduction ≥ 40% from baseline).

1.2.2 Average scores

Continuous measures of agitation (up to two hours) also favoured aripiprazole: ABS change score (2 RCTs, n = 380, MD ‐3.77, 95% CI ‐5.39 to ‐2.16), ACES change score (2 RCTs, n = 380, MD ‐0.71, 95% CI ‐1.15 to ‐0.28) and PANSS‐EC change score (1 RCT, n = 261, MD ‐2.49, 95% CI ‐4.28 to ‐0.70). These findings were still favourable for aripiprazole for both a schizophrenia subgroup (2 RCTs, n = 263, MD ‐2.55, 95% CI ‐3.78 to ‐1.32), and a non‐sedated participants subgroup ‐ based on ACES score (2 RCTs, n = 355, MD ‐2.68, 95% CI ‐3.75 to ‐1.62) and on AEs (2 RCTs, n = 365, MD ‐2.83, 95% CI ‐3.92 to ‐1.75, Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) vs PLACEBO/NIL, Outcome 3 Specific behaviour: 1b. Agitation ‐ average scores ‐ i. up to 2 hours.

1.3 Global state

Various

There were fewer non‐responders at first injection in aripiprazole group (1 RCT, n = 263, RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.71,low‐quality evidence) and participants allocated to aripiprazole had a significantly lower need for additional intervention with benzodiazepines (2 RCTs, n = 382, RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.80, Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) vs PLACEBO/NIL, Outcome 4 Global state: 1. Various.

1.3.2 Average scores ‐ up to two hours

Rating scales showed a significant advantage for participants allocated to aripiprazole: CGI‐I endpoint score (2 RCTs, n = 380, MD ‐0.73, 95% CI ‐0.97 to ‐0.49), CGI‐S change score (2 RCTs, n = 380, MD ‐0.56, 95% CI ‐0.86 to ‐0.26). CGI‐I endpoint score was also lower in the aripiprazole group for participants with a schizophrenia diagnosis (1 RCT, n = 75, MD ‐0.71, 95% CI ‐1.17 to ‐0.25, Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) vs PLACEBO/NIL, Outcome 5 Global state: 2. Average scores ‐ i. up to 2 hours.

1.4 Mental state ‐ average scores ‐ up to two hours

Change score of PANSS‐derived BPRS total (1 RCT, n = 110, MD ‐3.39, 95% CI ‐7.03 to 0.25) and positive subscale (1 RCT, n = 110, MD ‐0.62, 95% CI ‐1.65 to 0.41) were similar between aripiprazole and placebo groups (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) vs PLACEBO/NIL, Outcome 6 Mental state: 1. Average scores ‐ i. up to 2 hours.

1.5 Adverse effects

1.5.1 General

More participants allocated to aripiprazole experienced one or more drug‐related adverse effects by two hours (1 RCT, n = 117, RR 1.51, 95% CI 0.93 to 2.46, very low‐quality evidence), and onset or worsening of adverse effects following the second injection (1 RCT, n = 262, RR 2.40, 95% CI 1.36 to 4.23, Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) vs PLACEBO/NIL, Outcome 7 Adverse effects: 1a. General.

Similar findings were found for serious adverse effects, which were higher in the aripiprazole group when compared to placebo group (2 RCTs, n = 379, RR 3.77, 95% CI 0.63 to 22.60); in the aripiprazole group a tonic clonic seizure event occurred (1 RCT, n = 117, RR 3.26, 95% CI 0.14 to 78.49, Analysis 1.8). No deaths were reported.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) vs PLACEBO/NIL, Outcome 8 Adverse effects: 1b. General ‐ serious.

1.5.2 Specific ‐ arousal

No clear effect was found for other effects such as 'insomnia during 24 hours' (1 RCT, n = 262, RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.52), 'over'‐sedated (1 RCT, n = 262, RR 1.59, 95% CI 0.60 to 4.20) somnolence (2 RCTs, n = 379, RR 1.52, 95% CI 0.57 to 4.00, Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) vs PLACEBO/NIL, Outcome 9 Adverse effects: 2a. Specific ‐ arousal.

1.5.3 Specific ‐ cardiovascular

Again, similar numbers in each treatment group experienced dizziness (2 RCTs, n = 379, RR 1.77, 95% CI 0.66 to 4.70), tachycardia (1 RCT, n = 117, RR 4.36, 95% CI 0.50 to 37.82) during 24 hours and sinus tachycardia (1 RCT, n = 117, RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.02 to 8.72, Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) vs PLACEBO/NIL, Outcome 10 Adverse effects: 2b. Specific ‐ cardiovascular.

1.5.4 Specific ‐ movement disorders

Drug‐related adverse effects were experienced only by participants allocated to aripiprazole during 24 hours but no effect between treatment groups was observed for akathisia (1 RCT, n = 117, RR 7.61, 95% CI 0.40 to 144.21), dystonia (1 RCT, n = 117, RR 3.26, 95% CI 0.14 to 78.49) and extrapyramidal symptoms (1 RCT, n = 262, RR 1.50 95% CI 0.06 to 36.45, Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) vs PLACEBO/NIL, Outcome 11 Adverse effects: 2c. Specific ‐ movement disorders.

1.5.5 Miscellaneous

More participants allocated to the aripiprazole group experienced nausea during 24 hours (2 RCTs, n = 379, RR 3.97 95% CI 1.13 to 13.92). Concerning other miscellaneous adverse effects, no observable differences were found: agitation (2 RCTs, n = 379, RR 0.88 95% CI 0.33 to 2.37), headache (2 RCTs, n = 379, RR 1.66 95% CI 0.74 to 3.71), pain at injection site (2 RCTs, n = 379, RR 1.10 95% CI 0.30 to 3.94), and vomiting (1 RCT, n = 117, RR 2.18 95% CI 0.20 to 23.37, Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) vs PLACEBO/NIL, Outcome 12 Adverse effects: 2d. Specific ‐ miscellaneous.

1.6 Leaving the study early

We found no clear difference for numbers of participants leaving the study early for 'any reason' (2 RCTs, n = 382, RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.35 to 4.74); 'lack of efficacy' (2 RCTs, n = 382, RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.07 to 3.06), 'consent withdrawal' (2 RCTs, n = 382, RR 1.68, 95% CI 0.23 to 12.46), 'adverse effects' (2 RCTs, n = 382, RR 2.25, 95% CI 0.25 to 20.54), and 'other' reasons (2 RCTs, n = 382, RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.15 to 7.44, Analysis 1.13).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) vs PLACEBO/NIL, Outcome 13 Leaving the study early.

2. COMPARISON 2. ARIPIPRAZOLE (intramuscular) versus OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTIC: a. HALOPERIDOL (intramuscular)

2.1 Repeated need for tranquillisation

Compared to haloperidol, more participants allocated to aripiprazole needed additional injections during 24 hours (2 RCTs, n = 477, RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.63, very low‐quality evidence). A comparable pattern was found in terms of need of 1 additional injection (1 RCT, n = 117, RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.66 to 2.70) and 2 additional injections (1 RCT, n = 117, RR 2.37, 95% CI 0.77 to 7.26) during 24 hours (Analysis 2.1). Even though not being statistically significant, leading to an equal to higher number of additional injections needed must be taken into account when considering clinical significance.

2.1. Analysis.