Abstract

Background

Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia are becoming increasingly common with the aging of most populations. The majority of individuals with dementia will first present for care and assessment in primary care settings. There is a need for brief dementia screening instruments that can accurately diagnose dementia in primary care settings. The Mini‐Cog is a brief, cognitive screening test that is frequently used to evaluate cognition in older adults in various settings.

Objectives

To determine the diagnostic accuracy of the Mini‐Cog for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease dementia and related dementias in a primary care setting.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Register of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies, MEDLINE, Embase and four other databases, initially to September 2012. Since then, four updates to the search were performed using the same search methods, and the most recent was January 2017. We used citation tracking (using the databases' ‘related articles’ feature, where available) as an additional search method and contacted authors of eligible studies for unpublished data.

Selection criteria

We only included studies that evaluated the Mini‐Cog as an index test for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia or related forms of dementia when compared to a reference standard using validated criteria for dementia. We only included studies that were conducted in primary care populations.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted and described information on the characteristics of the study participants and study setting. Using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS‐2) criteria we evaluated the quality of studies, and we assessed risk of bias and applicability of each study for each domain in QUADAS‐2. Two review authors independently extracted information on the true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives and entered the data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5). We then used RevMan 5 to determine the sensitivity, specificity, and 95% confidence intervals. We summarized the sensitivity and specificity of the Mini‐Cog in the individual studies in forest plots and also plotted them in a receiver operating characteristic plot. We also created a 'Risk of bias' and applicability concerns graph to summarize information related to the quality of included studies.

Main results

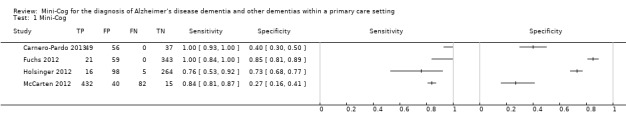

There were a total of four studies that met our inclusion criteria, including a total of 1517 total participants. The sensitivity of the Mini‐Cog varied between 0.76 to 1.00 in studies while the specificity varied between 0.27 to 0.85. The included studies displayed significant heterogeneity in both methodologies and clinical populations, which did not allow for a meta‐analysis to be completed. Only one study (Holsinger 2012) was found to be at low risk of bias on all methodological domains. The results of this study reported that the sensitivity of the Mini‐Cog was 0.76 and the specificity was 0.73. We found the quality of all other included studies to be low due to a high risk of bias with methodological limitations primarily in their selection of participants.

Authors' conclusions

There is a limited number of studies evaluating the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog for the diagnosis of dementia in primary care settings. Given the small number of studies, the wide range in estimates of the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog, and methodological limitations identified in most of the studies, at the present time there is insufficient evidence to recommend that the Mini‐Cog be used as a screening test for dementia in primary care. Further studies are required to determine the accuracy of Mini‐Cog in primary care and whether this tool has sufficient diagnostic test accuracy to be useful as a screening test in this setting.

Plain language summary

How accurate is the mini‐cog test when used to assess dementia in general practice?

Background and rationale for review

In most parts of the world there are increasing numbers of older adults, and memory complaints and conditions such as Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia are becoming increasingly common as a result. Most individuals with memory difficulties will first seek out care or be identified in the healthcare system through their primary care health care providers, which may include family physicians or nurses. Therefore, there is a need for tools that could identify individuals who may have dementia or significant memory problems. These tools should also be able to rule out dementia in those individuals with memory complaints who do not have dementia or significant memory problems. Such tools in primary care must be relatively easy to use, quick to administer, and accurate so as to be feasible to use in primary care while at the same time not overdiagnose or underdiagnose dementia. The Mini‐Cog, a brief cognitive screening tool, has been suggested as a possible screening test for dementia in primary care as it has been reported to be accurate and relatively easy to administer in primary care settings. The Mini‐Cog consists of a memory task that involves recall of three words and an evaluation of a clock drawing task.

Study characteristics

We searched electronic databases for articles evaluating the Mini‐Cog and this evidence is current as of January 2017. The purpose of our review was to compare the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog for diagnosing dementia of any type in primary care settings when compared to in‐depth evaluation conducted by dementia specialists. We included studies that evaluated individuals with any potential severity of dementia and regardless of whether previous cognitive testing had been completed prior to the Mini‐Cog. Overall, our review identified four studies conducted in primary care settings that compared the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog to detailed assessment of dementia by dementia specialists.

Quality of the evidence

Of the four studies included in the review, all except one study had limitations in how the Mini‐Cog was evaluated, which may have led to an overestimation of the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in the remaining studies. Notably, the most problematic issue in study quality related to how participants were selected to participate in research studies, which may have further contributed to an overestimation of the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in most of the studies included in our review.

Key findings

The results of the highest‐quality study Holsinger 2012 found that the Mini‐Cog had a sensitivity of 76%, indicating that the Mini‐Cog failed to detect up to 24% of individuals who have dementia (e.g. false negatives). In this same study, the specificity of the Mini‐Cog was 73% indicating that up to 27% of individuals may be incorrectly identified as having dementia on the Mini‐Cog when these individuals do not actually have an underlying dementia (e.g. false positives). We conclude that at the present time there is not enough evidence to support the routine use of the Mini‐Cog as a screening test for dementia in primary care and additional studies are required before concluding that the Mini‐Cog is useful in this setting.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings'. 'Mini‐Cog for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias within a primary care setting.

| Mini‐Cog for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias within a primary care setting | ||||

| Population | The study populations were sampled from participants identified in primary care settings. | |||

| Setting | The primary care setting was identified as representing a sample that would be presenting to primary care settings where the Mini‐Cog might be used as a screening test to identify individuals who may benefit from additional evaluation. Studies that identified individuals in primary care where they received both the index test and a reference standard were used. | |||

| Indext test | The Mini‐Cog performed in insolation or scored based on results on the clock drawing test or three‐word recall were included. | |||

| Reference Standard | Clinical diagnosis of dementia was made using recognized standard diagnostic criteria. | |||

| Studies | Cross‐sectional studies were included, case control studies were excluded | |||

| Study |

Accuracy (95% CI) |

Number of participants |

Dementia prevalence |

Implications |

| Carnero‐Pardo 2013 |

Sensitivity: 1.00 (0.93 to 1.00) Specificity: 0.40 (0.30 to 0.50) |

142 | 34.5% | Participants were sampled including individuals who did have a pre‐existing history of dementia or cognitive impairment prior to assessment with the Mini‐Cog and reference standard but all participants had to have cognitive complaints suggestive of possible undiagnosed dementia or cognitive impairment. |

| Fuchs 2012 |

Sensitivity: 1.00 (0.84 to 1.00) Specificity: 0.85 (0.81 to 0.89) |

423 | 5.0% | The study excluded individuals with dementia at baseline, and those included in the study received a 36 month follow up assessment. Thus participants in the sample who were diagnosed with dementia were in the early stages of the disease. |

| Holsinger 2012 |

Sensitivity: 0.76 (0.53 to 0.92) Specificity: 0.73 (0.68 to 0.77) |

383 | 5.5% | Study involved evaluation of individuals in primary care settings without a documented history of dementia recorded at baseline. |

| McCarten 2012 |

Sensitivity: 0.84 (0.81 to 0.87) Specificity: 0.27 (0.16 to 0.41) |

569 | 90.3% | Individuals with documented cognitive impairment were excluded from screening. Sampling involved screening of all participants in primary care and then offering further evaluation to individuals who either screened positive or negative on initial screening and who also agreed to have further evaluation. |

CI: confidence interval

Background

Target condition being diagnosed

Alzheimer's disease and related forms of dementia are common among older adults with a prevalence of 8% in individuals aged over 65 years and increasing to a prevalence of approximately 43% in adults aged 85 years and older (Thies 2012). Given the increasing number of older adults in most developing countries, the prevalence of dementia is expected to increase considerably in the coming years (Ferri 2005). Alzheimer's disease and related forms of dementia are currently incurable and result in considerable direct and indirect costs, both in terms of formal health care and lost productivity from both the affected individuals and their caregivers (Thies 2012). There is a debate as to the value of arriving at a diagnosis of dementia earlier in the disease process. Diagnosing Alzheimer's disease in the pre‐clinical state using biomarker or neuroimaging modalities without the availability of effective treatments or interventions to alter the disease course may be harmful in some situations (Le Couteur 2013). However, qualitative research has demonstrated that many individuals with clinically diagnosed dementia and their caregivers would prefer to know a diagnosis of dementia early in the disease process, as knowledge of the diagnosis of dementia can help to facilitate a better understanding of observed cognitive and functional changes and facilitate more timely access to supports and services (Prorok 2013; Prorok 2016). A diagnosis of dementia is necessary to access certain services and supports for individuals and their caregivers; and pharmacological treatments such as cholinesterase inhibitors (Birks 2006; Rolinski 2012) or memantine (McShane 2009; Wilkinson 2012) have only been shown to be effective in providing temporary symptomatic improvement in cognitive function for individuals diagnosed with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease.

The diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease is clinical and based on a history of progressive decline in cognition affecting memory and at least one other area of cognitive functioning (e.g. apraxia, agnosia, or executive dysfunction). There must be a decline from a previous level of functioning resulting in significant social or occupational impairment (APA 2000; APA 2013; McKhann 2001). A definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease can only be achieved at autopsy but a clinical diagnosis using standardized criteria is associated with a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 70% when compared to autopsy‐proven cases (Knopman 2001; Nagy 1998).

Approximately 50% to 80% of all individuals with dementia are ultimately classified as having Alzheimer's disease (Blennow 2006; Brunnstrom 2009; Canadian Study of Health and Aging 1994). Vascular dementias may occur more abruptly or present with a step‐wise decline in cognition over time and account for approximately 15% to 20% of dementias (Brunnstrom 2009; Canadian Study of Health and Aging 1994; Feldman 2003; Lobo 2000). Dementia with a mixed Alzheimer's disease and vascular pathology is present in 10% to 30% of cases (Brunnstrom 2009; Crystal 2000; Feldman 2003). Less frequent causes of dementia include dementia with Lewy bodies (Brunnstrom 2009) or Parkinson's disease dementia (Aarsland 2005). People experiencing frontotemporal dementia account for a smaller proportion of dementias (4% to 8%) and often present with problems in executive function and changes in behaviour, while memory is relatively preserved (Brunnstrom 2009; Grecicus 2002).

Index test(s)

The Mini‐Cog is a brief cognitive screening test consisting of two components, a delayed, three‐word recall task and the clock drawing test (Borson 2000). The Mini‐Cog was initially examined in community settings and was designed to provide a relatively brief cognitive screening test that was free of educational and cultural biases. Different scoring algorithms were tested to determine which combination had the optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity (McCarten 2011; Scanlan 2001). The Mini‐Cog takes approximately three to five minutes to complete in routine practice (Borson 2000; Holsinger 2007; Scanlan 2001). The Mini‐Cog has been reported to have little potential for bias as a result of education or language (Borson 2000; Borson 2005).

Clinical pathway

Dementia typically begins with subtle cognitive changes and progresses gradually over the course of several years. Most older adults with memory complaints will first present to their general practitioner or other primary care healthcare provider (for example nurses or a nurse practitioner). There is a presumed period when people are asymptomatic, although the disease pathology may be progressing. Individuals or their relatives may first notice subtle impairments of short‐term memory or other areas of cognitive functioning. Gradually, additional cognitive deficits become apparent resulting in difficulty completing complex activities of daily living such as the management of finances and medications, or operating motor vehicles (Njegovan 2001). The attribution of cognitive symptoms to normal aging may cause delays in the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer's disease or other types of dementia (Prorok 2013). Therefore, there is a need for accurate brief dementia screening tests to help distinguish between the cognitive changes associated with normal aging and changes that might indicate dementia. Individuals with dementia often first present to primary care health care providers with cognitive complaints or functional changes that might indicate the possibility of a dementia (Feldman 2008). Even though most individuals with dementia are first evaluated in primary care, the absence of systematic dementia screening programs for dementia in many primary care settings may result in an underdiagnosis of individuals with dementia (Connolly 2011).

Prior test(s)

As the Mini‐Cog is recommended to be used as an initial screening test for dementia in primary care (Brodaty 2006; Ismail 2010; Milne 2008; Tsoi 2015) it is unlikely that individuals will have had any testing completed prior to the administration of the Mini‐Cog.

Role of index test(s)

Primary healthcare providers may administer brief cognitive screening tests and, depending on the results of the initial tests, an individual may then have additional investigations or cognitive tests to confirm if a diagnosis of dementia is present. In some settings, a positive result on a brief cognitive screening test may result in a referral to a dementia specialist, such as a neurologist, geriatrician, or geriatric psychiatrist. Some countries have recently recommended that brief cognitive screening tests be administered to all older adults in order to identify asymptomatic individuals who may have underlying undiagnosed cognitive impairment (Cordell 2013), although the utility of routine screening of asymptomatic individuals for dementia in primary care settings is controversial (UK National Screening Committee 2015). The Mini‐Cog would most often be used in most clinical settings as an initial screening test for dementia and not to arrive at a definitive diagnosis of dementia on its own. However, in the current review we evaluated the diagnostic test accuracy of the Mini‐Cog when compared to a reference standard diagnosis of dementia to determine the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in keeping with previous Cochrane Reviews of diagnostic test accuracy of dementia cognitive tests.

Alternative test(s)

We will not be including alternative tests in this review because there are currently no standard tests available for the diagnosis of dementia. The diagnostic test accuracy of other cognitive tests is the subject of separate reviews (Creavin 2016; Davis 2015; Harrison 2014; Hendry 2014).

Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement (CDCI) is in the process of conducting a series of diagnostic test accuracy reviews of biomarkers and scales. CDCI is conducting reviews on individual tests compared to a reference standard and they plan to compare the results of different tests in an overview.

Rationale

Most individuals with dementia are first assessed and diagnosed in primary care settings (Prorok 2013). Individuals with dementia or cognitive disorders may present to primary care providers with cognitive symptoms although primary care providers may not identify older adults with cognitive symptoms in routine brief clinical encounters (Bradford 2009; Connolly 2011). Some studies have found that in primary care the majority of older adults with dementia are undiagnosed (Boustani 2005; Connolly 2011; Sternberg 2000) and mild dementia is particularly under‐diagnosed (Van den Dungen 2011). Accurate diagnosis of dementia is important in order to initiate dementia therapeutics including both non‐pharmacological treatments and pharmacological treatments such as cholinesterase inhibitors (Birks 2006; Rolinski 2012) and memantine (McShane 2009). Early diagnosis and treatment of dementia may also have long‐term clinical benefits for the patient and his or her caregivers during the course of disease progression (Bennett 2003; Prorok 2013; Thies 2012). Routine screening of all older adults for dementia in primary care using cognitive screening tests appears to improve dementia case detection rates when compared to usual care without routine screening of older adults (Eichler 2015). Comprehensive evaluation conducted by psychologists or dementia physician specialists such as general psychiatrists, geriatric psychiatrists, geriatricians, or neurologists using standardized diagnostic criteria is considered the reference standard for diagnosing dementia in older adults. However, access to these specialized resources is scarce and expensive and as such they are not practical to be used routinely in the evaluation of cognitive complaints (Pimlott 2009; Yaffe 2008). While there are some cognitive tests that can be performed by healthcare providers who are not dementia specialists, many of these tests are time consuming and may not be practical to use routinely in primary care settings (Brodaty 2006; Pimlott 2009). As such, brief but relatively accurate cognitive screening tests are required for healthcare providers in primary care settings as an initial test to identify individuals who may require more in‐depth evaluation of cognition either in primary care or in specialist settings.

The sensitivity and specificity of such brief screening tests are likely to vary depending upon the setting in which they are used (Holsinger 2007). If the Mini‐Cog was used in primary care settings, it could allow healthcare professionals or lay people to initially assess older adults for the possible presence of dementia. Individuals that screen positive for cognitive impairment on the Mini‐Cog would then be further investigated for the presence of dementia using additional cognitive tests or other investigations. Given that the Mini‐Cog is brief, widely available, easy to administer, and has been reported to have reasonable test accuracy properties (Brodaty 2006; Ismail 2010; Lin 2013; Lorentz 2002; Milne 2008) it may be well suited for use as an initial cognitive screening test in primary care, and has already been recommended as a suitable test for primary care dementia screening programmes in some countries (Cordell 2013). Other cognitive tests that may also be suitable for use in primary care settings include the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Holsinger 2007), the General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG), or the Memory Impairment Screen (Brodaty 2006), however each of these take longer to administer, and may be biased by language, culture, and education level (Matallana 2011) in contrast to the Mini‐Cog. The current review will examine the diagnostic accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in primary care settings. Separate DTA reviews are being undertaken for the Mini‐Cog in community (Fage 2015) and secondary care settings (Chan 2014).

Objectives

To determine the diagnostic accuracy of the Mini‐Cog for diagnosing Alzheimer's disease dementia and related dementias in a primary care setting.

Secondary objectives

To investigate the heterogeneity of test accuracy in the included studies and potential sources of heterogeneity. These potential sources of heterogeneity will include the baseline prevalence of dementia in study samples, thresholds used to determine positive test results, the type of dementia (Alzheimer's disease dementia or all causes of dementia), and aspects of study design related to study quality.

To identify gaps in the evidence where further research is required.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all cross‐sectional studies from primary care settings with well‐defined populations that used the Mini‐Cog as an index cognitive test compared to a reference standard for the diagnosis of dementia. Case‐control studies were not included in this review. Studies had to use a reference standard to determine whether or not dementia was present. Studies used the Mini‐Cog as an initial cognitive test for dementia and not for the confirmation of a diagnosis of dementia. When possible, studies administered the index and reference tests to individuals where their diagnosis was not already known, although some studies may have used the test on people with a previously known diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or a related dementia.

Participants

Study participants presented in a primary care setting and may or may not have been ultimately diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease or all‐cause dementia following additional evaluation. Participants may have had cognitive complaints or dementia at baseline although their cognitive status was not known to the individual administering the Mini‐Cog or the reference standard. Studies on participants with a developmental disability, which prevented them from completing the Mini‐Cog, were excluded.

Index tests

Mini‐Cog test

The Mini‐Cog consists of two components: a three‐word recall task that assesses memory and the clock drawing test that assesses cognitive domains such as cognitive function, language, visual‐motor skills and executive function. The standard scoring system involves assigning a score of 0 to 3 points on the word recall task for the correct recall of 0, 1, 2, or 3 words, respectively. The clock drawing test is scored as being either 'normal' or 'abnormal'. A positive test on the Mini‐Cog (i.e. indicating a possible diagnosis of dementia) is assigned if the delayed word recall score is 0 out of 3, or if their delayed recall score is either 1 or 2 and their clock drawing test is abnormal. A score of 3 on the delayed word recall or 1 to 2 on the word recall with a normal clock drawing is considered a negative test (i.e. no dementia is present) (Borson 2000).

Studies must have included the results of the Mini‐Cog. We planned to examine the potential effects of multiple scoring algorithms through subgroup analyses, although there were an insufficient number of studies identified to complete this analysis in our review.

Target conditions

The primary target condition of interest for this review was any stage of Alzheimer's disease or all‐cause dementia, which in primary care settings would most commonly be caused by Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, or some combination of these two pathologies.

Reference standards

While a definitive diagnosis can only be made post‐mortem at autopsy, there are clinical reference standard criteria for the diagnosis of the different forms of dementia. All dementia diagnostic criteria require that an individual has impairment in multiple areas of cognition that results in difficulties in daily functioning which is not directly caused by either the effects of a substance or general medical condition. We have included several potential reference standards for the diagnosis of all‐cause dementia or specific types of dementia. All‐cause dementia is commonly diagnosed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM‐IV) (APA 2000), DSM‐5 criteria for major neurocognitive disorder (APA 2013), or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnosis of dementia (WHO 2010). The standard clinical diagnostic criteria commonly used for Alzheimer's disease dementia include the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS‐ADRDA) for probable or possible Alzheimer's disease dementia (McKhann 1984; McKhann 2011). Diagnostic criteria for other types of dementia include the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l'Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINCDS‐AIREN) criteria for vascular dementia (Roman 1993), standard criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies (McKeith 2005) and for frontotemporal dementia (McKhann 2001).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

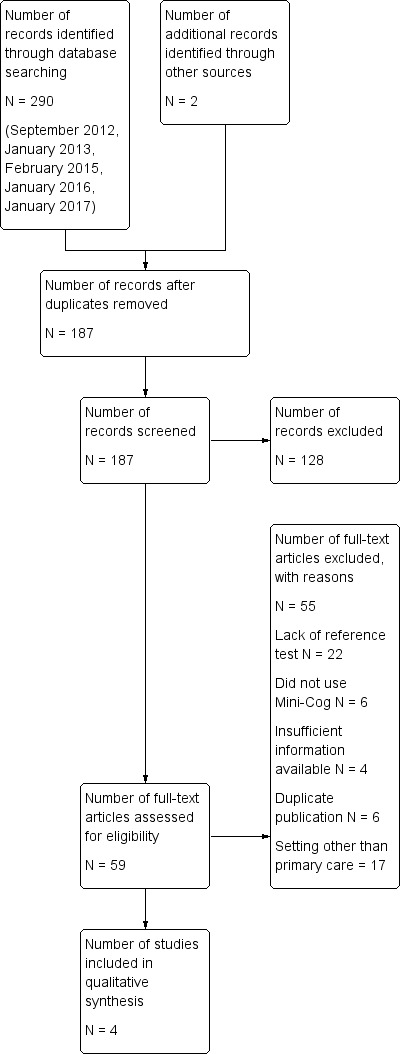

We initially searched up to September 2012. Four subsequent updates to the initial search was performed using the same search methods: January 2013, February 2015, January 2016, and January 2017. We searched the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Register of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies that is currently under development, MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1950 to January 2017), Embase (OvidSP) (1974 to 31 January 2017), BIOSIS Previews (Thomson Reuters Web of Science) (1926 to January 2017), Science Citation Index (Thomson Reuters Web of Science) (1945 to January 2017), PsycINFO (OvidSP) (1806 to January week 4 2017), and LILACS (BIREME) (January 2017) (for results of the database search, see Figure 1). See Appendix 1 for details of the sources searched, the search strategies used and the number of citations retrieved, and to view the 'generic' search that is used regularly for Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement's Register. Similarly, we designed structured search strategies using search terms appropriate for each database. Controlled vocabulary such as MeSH terms and EMTREE were used where appropriate. We made no attempt to restrict studies based on the sampling frame or setting in the searches that we developed. This was meant to maximize the sensitivity and allow inclusion to be assessed on the basis of population‐based sampling at testing (see ‘Selection of studies’, below). We did not use search filters (collections of terms aimed at reducing the number of studies that need to be screened) as an overall limiter because those published have not proved sensitive enough (Whiting 2011). We did not apply any language restriction to the electronic searches.

1.

Study flow diagram

A single review author with extensive experience in systematic reviews performed the initial searches. Two review authors independently screened abstracts and titles.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of all relevant studies for additional relevant studies, since this has been reported to be a useful method to minimize overlooking potentially relevant studies for complex reviews (Greenhalgh 2005; Horsely 2011). We also used these studies to search electronic databases to identify additional studies through the use of the related article feature. We asked research groups authoring studies that were used in the analysis for unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Studies had to address the following.

Make use of the Mini‐Cog as a cognitive test in a primary care setting.

Include patients from a primary care setting who may or may not have dementia or cognitive complaints.

Clearly explain how a diagnosis of dementia was confirmed according to a reference standard such as the DSM IV‐TR, DSM‐5, or NINCDS‐ADRDA at the same time or within the same four‐week time period that the Mini‐Cog was administered. Formal neuropsychological evaluation or neuroimaging was required for a diagnosis of dementia.

We first selected articles based on the abstract and title. Two review authors independently located the selected articles and assessed them for inclusion. A third review author resolved disagreements.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors extracted the following data from all included studies.

Author, journal, and year of publication.

Scoring algorithm for the Mini‐Cog including cut‐points used to define a positive screen; method of Mini‐Cog administration, including who administered and interpreted the test and their training.

Reference criteria and method used to confirm diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or all‐cause dementia.

Baseline demographic characteristics of the study population including age, gender, ethnicity, spectrum of presenting symptoms, comorbidity, educational achievement, language, baseline prevalence of dementia, country, ApoE status, methods of participant recruitment and sampling procedures.

Length of time between administration of index test (Mini‐Cog) and the reference standard.

The sensitivity and specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios, of the index test in defining dementia.

Version of translation (if applicable).

Prevalence of dementia in the study population.

Assessment of methodological quality

To assess data quality we used the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS‐2) criteria (Whiting 2011). The QUADAS‐2 criteria contain assessment domains for patient selection, the index test, reference test, and flow and timing. Each domain has suggested signalling questions to assist with the assessment of risk of bias for each domain. The potential risk of bias associated with each domain is rated as being at high, low, or uncertain risk of bias. In addition, using the guide provided in QUADAS‐2, we determined the applicability of the study to the review question for each domain. We used a standardized 'Risk of bias' template to extract data on the risk of bias for each study using the form provided by the UK Support Unit Cochrane Diagnostic Test Accuracy group. See Appendix 2 for details. We summarized quality assessment results using the methodological quality summary table and methodological summary graph in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) (RevMan 2014).

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

We performed the statistical analysis as per the Cochrane guidelines for diagnostic test accuracy reviews (Macaskill 2010). We planned to construct two‐by‐two tables for the Mini‐Cog results for both all‐cause dementia and Alzheimer's disease dementia where this information was available.

We entered data from individual studies including the true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN) into RevMan 5. We determined these values by comparing the rates of TP, TN, FP, and FN for individuals with all‐cause dementia when compared to individuals without any form of dementia. For the primary analysis, we compared the diagnosis of all‐cause dementia to no dementia. We also calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios, as well as measures of statistical uncertainty (e.g. 95% confidence intervals) from the raw data for the primary analysis of dementia when compared to no dementia in RevMan 5. We presented the data from each study graphically by plotting sensitivities and specificities on a coupled forest plot. If multiple thresholds were reported for the Mini‐Cog, we planned to use the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic (HSROC) method of Rutter and Gastconis for the meta‐analysis (Rutter 2001). We had initially planned a meta‐analysis for this review although, due to a limited number of studies and methodological limitations present in the included studies, we did not undertake a meta‐analysis as a part of the final review.

Investigations of heterogeneity

The potential sources of heterogeneity that we intended to examine included the baseline prevalence of cognitive impairment in the target population, the cut‐points used to determine a positive test result, the reference standard used to diagnose dementia, the type of dementia (Alzheimer's disease dementia or all‐cause dementia), the severity of dementia in the study sample (using dementia severity assessment scales such as the Clinical Dementia Rating (Morris 1993) scale or the Global Deterioration Scale (Reisberg 1982)), and aspects related to study quality as assessed with the QUADAS‐2.

To investigate the effects of the sources of heterogeneity, we planned to complete subgroup analyses. These involved visual examination of the forest plot of sensitivity and specificity and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plot within each subgroup (for example baseline prevalence, type of dementia, etc). Additionally, we planned a formal analysis using the HSROC model. This model can be extended to include covariates in order to assess whether threshold, accuracy, or the shape of the summary ROC (SROC) curve varies with participant or study characteristics. However, given the small number of studies included in our review and methodological limitations of studies we were unable to complete these planned subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analyses

We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis in order to investigate the influence of study quality on the overall diagnostic accuracy of the Mini‐Cog test. We did not perform the sensitivity analysis as we did not undertake a meta‐analysis of the results.

Assessment of reporting bias

We had not planned to assess reporting bias because of current uncertainty about how it operates in test accuracy studies and the interpretation of existing analytical tools such as funnel plots.

Results

Results of the search

The results of the literature search are outlined below in Figure 1. A review of the electronic databases on four occasions between 2012 and 2017 identified a total of 292 articles. The same search strategy was employed for this review that was used in separate reviews of the Mini‐Cog in the community setting (Fage 2015) and secondary care setting (Chan 2014). After removal of duplications, two review authors independently reviewed a total of 187 abstracts and citations for inclusion criteria and suitability for inclusion in the final review.

We reviewed a total of 59 full‐text articles for eligibility to be included in the final review. Of these 59 articles, we excluded 55 due to a lack of a reference standard (N = 22), failure to include the Mini‐Cog as an index text (N = 6), duplicate publications (N = 6), incorrect setting (N = 17), or lack of sufficient data to be included in the review (N = 4).

The search identified four independent studies from four different study reports (Carnero‐Pardo 2013; Fuchs 2012; Holsinger 2012; McCarten 2012). The characteristics of the studies are outlined in the Table 1. These four studies included a total of 1517 participants and there was heterogeneity in the baseline prevalence of dementia across the studies, which ranged from 5% to 90%. Additional details regarding the design, setting, population, target condition and reference standard of each included study can be found in the Characteristics of included studies section.

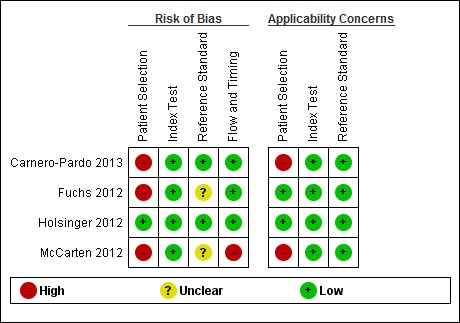

Methodological quality of included studies

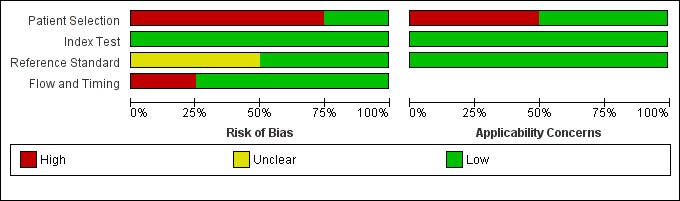

The results of the QUADAS‐2 assessment for the four studies are summarized in Figure 2 and the details of the risk of bias assessment for each of the included studies are presented in Figure 3. We judged three of the four studies as being at a high risk of bias in the patient selection domain (Carnero‐Pardo 2013; Fuchs 2012; McCarten 2012) as they did not enrol a consecutive or random sample of patients. For Fuchs 2012, it was unclear whether or not a case‐control design was avoided and the study failed to avoid inappropriate exclusions, thus introducing a high risk of patient selection bias. While all the included studies used the Mini‐Cog as the index test, McCarten 2012 adjusted the threshold of a positive screen in order to increase the sensitivity of the test by considering a positive screen on the Mini‐Cog for possible dementia being 3 or fewer points compared to the usual scoring of 2 or fewer points. We rated the risk of bias for the assessment of the reference standard as unclear for both Fuchs 2012 and McCarten 2012, as it was unclear whether the reference standard assessment results had been interpreted without knowledge of the Mini‐Cog results. We rated only one study as being at low risk of bias on all the QUADAS‐2 domains (Holsinger 2012).

2.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns graph: review authors' judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included studies

3.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns summary: review authors' judgements about each domain for each included study

Findings

There were four study reports on four unique study populations that were selected for the final review (Carnero‐Pardo 2013; Fuchs 2012; Holsinger 2012; McCarten 2012). The Characteristics of included studies section of this review and Table 3 include a summary of the included studies. Additional features of these studies are also summarized in Table 1. The baseline prevalence of dementia in the overall study samples varied from 5.0% (Fuchs 2012) to 90.3% (McCarten 2012). Two studies randomly recruited participants from Veteran Affairs Medical Centres either from routinely scheduled primary care appointments (McCarten 2012) or electronic medical records (Holsinger 2012), one study evaluated a random sample of medical records from primary practices in a defined geographic area (Fuchs 2012), and another study recruited from four primary care sites in two cities (Carnero‐Pardo 2013). The McCarten 2012 recruited individuals from primary care sites who either tested positive for possible dementia on the Mini‐Cog as part of a dementia screening programme or those individuals who tested negative on the Mini‐Cog but who requested additional evaluation of their cognition. The process for selection of participants in the McCarten 2012 study likely contributed to the high prevalence of dementia in this study, which was reported as 90.3%. Given that the McCarten 2012 study included individuals who initially tested negative and positive on the Mini‐Cog test, we decided to include it in the final review. Two studies excluded individuals with known cognitive impairment (Carnero‐Pardo 2013; McCarten 2012) and another two excluded individuals with a history of dementia at baseline (Fuchs 2012; Holsinger 2012). All studies used the DSM‐IV‐TR as the reference standard for the diagnosis of dementia and two studies based dementia diagnosis on additional reference standards, NINCDS‐ADRDA and NINCDS‐AIREN, as well (Fuchs 2012, Holsinger 2012). The diagnosis of dementia was agreed upon by consensus between two or more clinicians or researchers in all four studies. All studies used the original scoring system for the Mini‐Cog as proposed by Borson 2000 except for McCarten 2012, which used an adjusted scoring with a cut‐off of 3 or lower to indicate a positive test for dementia to increase the sensitivity of the Mini‐Cog compared to the usual cut‐off of 2 or lower. Three studies reported on the gender distribution of participants, with two studies reporting a majority of participants being female (Carnero‐Pardo 2013; Fuchs 2012) while one study reported a very low prevalence of female participants (Holsinger 2012).

1. Characteristics of included studies.

| Study ID | Country | Participants (N) | Setting | Mini‐Cog scoring | Reference standard for dementia diagnosis | Dementia prevalence | Notes |

| Carnero‐Pardo 2013 | Spain | 142 | 1 primary care location in Madrid and 3 primary care locations in Granada, only data from the Granada site was included | Standard scoring | DSM IV TR | 34.5% | The clock drawing test was incorporated into the reference standard at the Madrid site, data are presented for the Granada sites only. Screening was administered by professionals (no further specification) except for the clock drawing test component in Madrid, which was performed by a neurologist. |

| Fuchs 2012 | Germany | 423 | Participants were randomly selected from 138 study centres in 6 metropolitan areas in Germany although study reports information from 29 sites recruited from Dusseldorf region | Standard scoring | DSM IV | 5.0% | Individuals with known dementia were excluded from the study. Study evaluated accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in detecting incident dementia at 36 months' follow‐up from enrolment. Screening tests were administered by a trained physician or psychologist. |

| Holsinger 2012 | USA | 383 | Primary care locations affiliated with the Veterans Affairs near Durham, North Carolina | Standard scoring | DSM IV and NINCDS‐ADRDA |

5.5% | Excluded individuals with a known prior history of dementia based on diagnoses recorded in charts. The Mini‐Cog was administered by a research assistant. |

| McCarten 2012 | USA | 569 | 7 primary care settings affiliated with Veterans Affairs in Minneapolis, Minnesota | Standard scoring | DSM IV | 90.3% | Participants were first screened for possible dementia by trained advanced practice registered nurses based on interview during routine visit with those who initially screened positive being offered additional evaluation with the index and reference standards. Some individuals who did not screen positive at the initial interview requested and received additional evaluation. |

DSM IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition; DSM IV TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (text revision); NINCDS‐ADRDA: Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association

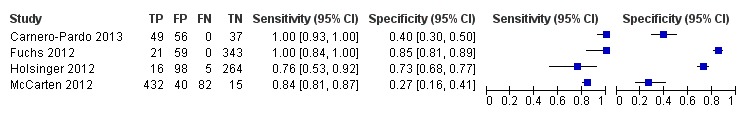

The extracted data for each study, including sensitivity and specificity, are summarized in Table 1 and in the forest plot presented in Figure 4. The sensitivities of the Mini‐Cog in the individual studies were reported as 1.00 (Carnero‐Pardo 2013), 1.00 (Fuchs 2012), 0.76 (Holsinger 2012) and 0.84 (McCarten 2012). The specificity of the Mini‐Cog varied in the individual studies and was 0.40 (Carnero‐Pardo 2013), 0.85 (Fuchs 2012), 0.73 (Holsinger 2012) and 0.27 (McCarten 2012). The values for the positive and negative predictive values are summarized in Table 1. Meta‐analysis of the diagnostic test accuracy of the Mini‐Cog was initially planned in this review, although due to the small number of studies and methodological limitations of included studies, we did not perform a meta‐analysis.

4.

Forest plot of Analysis 1 Mini‐Cog

The small number of studies, significant heterogeneity between the studies, and overall poor quality of most of the included studies precluded the use of meta‐analysis to arrive at pooled estimates for the diagnostic test accuracy. The planned evaluations of heterogeneity and subgroup analyses were also not undertaken for these same reasons.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Overall we found a small number of studies that evaluated the test accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in primary care settings. The reported sensitivities and specificities of the Mini‐Cog varied significantly between studies, likely due to underlying differences in study populations and research methods utilized across the different studies. Of the included studies, only one study was of high quality with the remaining studies having methodological limitations that may have contributed to an overestimation of the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in primary care. The heterogeneity of the study samples and methodological limitations present in the majority of the studies precluded formal meta‐analyses of study results and further analysis of some of the factors related to study design that may have affected the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog.

The one study in our review that was of high quality demonstrated that the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog has a sensitivity of 0.76 and specificity of 0.73 (Holsinger 2012). There is no agreed value for the sensitivity and specificity of cognitive screening tests in primary care settings. In primary care, it would be anticipated that the Mini‐Cog may be used initially as a screening test to identify individuals who would benefit from additional cognitive evaluation for dementia. In this situation, a brief test that has high sensitivity may be desirable. The sensitivity of the Mini‐Cog reported in the one high‐quality study identified in this review may not be high enough for the Mini‐Cog to be useful in this setting. One potential way that the sensitivity of the Mini‐Cog could be improved would be to modify the cut‐point on Mini‐Cog to increase its sensitivity, such as in McCarten 2011. Changing the cut‐point on the Mini‐Cog to improve its sensitivity would also likely reduce the specificity of Mini‐Cog, which would also need to be considered when using the Mini‐Cog in clinical settings. Although Holsinger 2012 reported that there was no statistical difference in the sensitivity of the Mini‐Cog when compared to the Modified Mini‐Mental State (3MS), the sensitivity of the 3MS was reported to be 0.86, which may be interpreted as a clinically significant difference in accuracy when compared to the sensitivity of the Mini‐Cog from the same study. The remaining studies of the Mini‐Cog in our review demonstrated higher sensitivities although these results must be interpreted with caution, as the remaining studies had methodological limitations that may have resulted in biased estimates of the sensitivity compared to Holsinger 2012. The low specificity of the Mini‐Cog reported in most studies would also make it unsuitable as a confirmatory test for dementia.

Multiple reviews of cognitive screening tests in primary care settings have identified the Mini‐Cog as a potentially appropriate cognitive test for primary care settings (Brodaty 2006; Ismail 2010; Lorentz 2002; Milne 2008; Tsoi 2015). These previous reviews have identified that the Mini‐Cog has some potentially attractive features as a cognitive test for primary care, such as being relatively brief and easy to measure and, in some studies, the sensitivity and specificity of the Mini‐Cog may appear to be adequate for use in this setting. However, one important limitation of these previous reviews is that the quality of the individual studies evaluating the Mini‐Cog was not taken into consideration when evaluating its accuracy. Based on the small number of included studies and the quality of these studies in this review, there is limited information regarding the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia in primary care. Although the Mini‐Cog has been recommended as a test in primary care dementia screening programmes (Cordell 2013), at this time the existing evidence to support the routine use of the Mini‐Cog as a screening test in primary care is insufficient.

In addition, one feature common to all the included studies in this review may have also introduced a potential source of bias. All studies used a version of the Mini‐Cog that obtained the three‐word recall component of the Mini‐Cog as part of a larger neuropsychological test (i.e. the three‐word recall from the MMSE). The accuracy of the Mini‐Cog to diagnose dementia may have differed depending on whether the component tests were administered by themselves or if the results of the Mini‐Cog were derived from the results of more comprehensive testing. The three‐word recall component of the Mini‐Cog may be more sensitive and less specific when incorporated into a longer test battery. There may be a greater delay between registration of the three words and the recall task when this is incorporated into a longer test battery, compared to having the word recall task administered in isolation.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

Strengths of our review include our use of a standardized search of electronic databases to identify both published and potentially unpublished studies evaluating the Mini‐Cog. We also used consistent data extraction processes throughout the review process. Importantly, we included an assessment of study quality, which identified that the majority of included studies had major methodological limitations and only one study was assessed at low risk of bias on all quality domains. In comparing the sensitivity reported in each study with the quality of studies, the three studies that were assessed as lower quality reported higher sensitivities than the one study that was found to be of higher quality study. Therefore, the results of the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in each study should be interpreted with caution and the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in some studies is potentially overestimated due to these methodological limitations. An additional limitation of this review was that we were unable to assess the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in different types of dementia as initially planned. The Mini‐Cog may be more accurate in some forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease, where memory is affected to greater extent early in the dementia process as compared to other types of dementia.

Applicability of findings to the review question

The Mini‐Cog would most commonly be used in primary care settings as a screening test to identify individuals who may or may not have identified cognitive complaints or dementia. Individuals testing positive on the Mini‐Cog would then likely be evaluated with additional cognitive tests in primary care or referred to specialists for further evaluation. Given the intended use of the Mini‐Cog in the diagnostic process as a screening tool, only two studies evaluated the Mini‐Cog as intended for use in most primary care settings to screen asymptomatic individuals for undetected dementia (Fuchs 2012; Holsinger 2012). Therefore, the results of some of the studies included in this review may not apply readily to the intended use of the Mini‐Cog in primary care settings. Additionally, the use of the Mini‐Cog as a diagnostic tool was the focus of separate reviews in the community setting (Fage 2015) and secondary care setting (Chan 2014).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

At the present time, there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the Mini‐Cog as a diagnostic test for Alzheimer's disease dementia and related forms of dementia in primary care settings. While the Mini‐Cog has been recommended as a potential diagnostic test for dementia in primary care settings (Cordell 2013; Brodaty 2006; Ismail 2010; Milne 2008; Lorentz 2002), based on the small number of published studies, methodological limitations present in the majority of studies, and modest sensitivity and specificity of the Mini‐Cog in one high‐quality study (Holsinger 2012), the evidence for the routine use of the Mini‐Cog as a cognitive diagnostic test in primary care is very limited. While the Mini‐Cog is brief and relatively easy to administer in primary care settings, the limited information currently available about the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog makes it of questionable clinical utility. There is also limited information about the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in other settings (Fage 2015). Furthermore, other brief cognitive tests for use in primary care cannot be recommended, since only a small number of studies have evaluated these tests in primary care (Davis 2015; Harrison 2014).

Implications for research.

Additional research is required to determine the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in primary care settings. Future studies should incorporate strong methodological study designs to minimize the risks of bias, which are potentially present in the existing published studies. This includes testing the Mini‐Cog as originally described and also through recruitment of a random sample of patients from primary care settings. The accuracy of the Mini‐Cog when compared to other dementia tests that would commonly be used in primary care settings such as the Mini‐Mental State Exam (Creavin 2016) or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (Creavin 2016) also needs to be evaluated.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Anna Noel‐Storr for her assistance with electronic database searches and Sue Marcus for her assistance with the registration and co‐ordination of the editorial reviews of the protocol and final review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Appendix 1: Electronic database search strategy

| Source | Search strategy | Hits retrieved |

| ALOIS DTA (Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Specialized Register) (see below for detailed explanation of what is contained within the ALOIS register) | Mini‐cog | September 2012: 19 January 2013: 0 |

| 1. MEDLINE In‐Process and other non‐indexed citations and MEDLINE 1950 to present (January 2013) (Ovid SP) | 1. "mini‐Cog".ti,ab. 2. minicog.ti,ab. 3. (MCE and (cognit* OR dement* OR screen* OR Alzheimer*)).ti,ab. 3. or/1‐3 |

September 2012: 91 January 2013: 12 |

| 2. Embase 1974‐2013 January 02 (OvidSP) |

1. "mini‐cog*".mp. 2. minicog*.mp. 3. 1 or 2 |

September 2012: 96 January 2013: 37 |

| 3. PsycINFO 1806 to January week 1 2013 (OvidSP) |

1. minicog*.mp. 2. "mini‐cog*".mp. 3. 1 or 2 |

September 2012: 69 January 2013: 28 |

| 4.Biosis previews 1926 to present (January 2013) (ISI Web of Knowledge) | Topic=("mini‐cog*" OR "minicog*") Timespan=All Years. Databases=BIOSIS Previews. Lemmatization=On |

September 2012: 33 January 2013: 7 |

| 5.Web of Science and conference proceedings (1945 to January 2013) | Topic=("mini‐cog*" OR "minicog*") Timespan=All Years. Databases=BIOSIS Previews. Lemmatization=On |

September 2012: 93 January 2013: 20 |

| 6. LILACS (BIREME) (January 2013) | "mini‐cog" OR minicog [Words] | September 2012: 2 January 2013: 2 |

| Total before deduplication | September 2012: 403 January 2013: 106 |

|

| Total after deduplication and first assessment |

September 2012: 108 January 2013: 41 |

|

In addition to the above single concept search based on the Index test, Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement ran a more complex, multi‐concept search each month primarily for the identification of diagnostic test accuracy studies of neuropsychological tests. Where possible they obtained the full texts of the studies identified. This approach is expected to help identify those papers where the index test of interest (in this case Mini‐Cog) is used and the paper contains usable data but where Mini‐Cog was not alluded to in the report's citation.

The MEDLINE strategy used is below. Similar strategies are also run in Embase and PsycINFO.

The Mini‐Cog search utilized only one search concept: the index test (Mini‐Cog):

1. "mini‐Cog".ti,ab.

2. minicog.ti,ab.

3. (MCE and (cognit* OR dement* OR screen* OR Alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

4. or/1‐3

The MEDLINE generic search run for the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement DTA register:

1. "word recall".ti,ab.

2. ("7‐minute screen" OR “seven‐minute screen”).ti,ab.

3. ("6 item cognitive impairment test" OR “six‐item cognitive impairment test”).ti,ab.

4. "6 CIT".ti,ab.

5. "AB cognitive screen".ti,ab.

6. "abbreviated mental test".ti,ab.

7. "ADAS‐cog".ti,ab.

8. AD8.ti,ab.

9. "inform* interview".ti,ab.

10. "animal fluency test".ti,ab.

11. "brief alzheimer* screen".ti,ab.

12. "brief cognitive scale".ti,ab.

13. "clinical dementia rating scale".ti,ab.

14. "clinical dementia test".ti,ab.

15. "community screening interview for dementia".ti,ab.

16. "cognitive abilities screening instrument".ti,ab.

17. "cognitive assessment screening test".ti,ab.

18. "cognitive capacity screening examination".ti,ab.

19. "clock drawing test".ti,ab.

20. "deterioration cognitive observee".ti,ab.

21. ("Dem Tect" OR DemTect).ti,ab.

22. "object memory evaluation".ti,ab.

23. "IQCODE".ti,ab.

24. "mattis dementia rating scale".ti,ab.

25. "memory impairment screen".ti,ab.

26. "minnesota cognitive acuity screen".ti,ab.

27. "mini‐cog".ti,ab.

28. "mini‐mental state exam*".ti,ab.

29. "mmse".ti,ab.

30. "modified mini‐mental state exam".ti,ab.

31. "3MS".ti,ab.

32. “neurobehavio?ral cognitive status exam*”.ti,ab.

33. "cognistat".ti,ab.

34. "quick cognitive screening test".ti,ab.

35. "QCST".ti,ab.

36. "rapid dementia screening test".ti,ab.

37. "RDST".ti,ab.

38. "repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status".ti,ab.

39. "RBANS".ti,ab.

40. "rowland universal dementia assessment scale".ti,ab.

41. "rudas".ti,ab.

42. "self‐administered gerocognitive exam*".ti,ab.

43. ("self‐administered" and "SAGE").ti,ab.

44. "self‐administered computerized screening test for dementia".ti,ab.

45. "short and sweet screening instrument".ti,ab.

46. "sassi".ti,ab.

47. "short cognitive performance test".ti,ab.

48. "syndrome kurztest".ti,ab.

49. ("six item screener" OR “6‐item screener”).ti,ab.

50. "short memory questionnaire".ti,ab.

51. ("short memory questionnaire" and "SMQ").ti,ab.

52. "short orientation memory concentration test".ti,ab.

53. "s‐omc".ti,ab.

54. "short blessed test".ti,ab.

55. "short portable mental status questionnaire".ti,ab.

56. "spmsq".ti,ab.

57. "short test of mental status".ti,ab.

58. "telephone interview of cognitive status modified".ti,ab.

59. "tics‐m".ti,ab.

60. "trail making test".ti,ab.

61. "verbal fluency categories".ti,ab.

62. "WORLD test".ti,ab.

63. "general practitioner assessment of cognition".ti,ab.

64. "GPCOG".ti,ab.

65. "Hopkins verbal learning test".ti,ab.

66. "HVLT".ti,ab.

67. "time and change test".ti,ab.

68. "modified world test".ti,ab.

69. "symptoms of dementia screener".ti,ab.

70. "dementia questionnaire".ti,ab.

71. "7MS".ti,ab.

72. ("concord informant dementia scale" or CIDS).ti,ab.

73. (SAPH or "dementia screening and perceived harm*").ti,ab.

74. or/1‐73

75. exp Dementia/

76. Delirium, Dementia, Amnestic, Cognitive Disorders/

77. dement*.ti,ab.

78. alzheimer*.ti,ab.

79. AD.ti,ab.

80. ("lewy bod*" or DLB or LBD or FTD or FTLD or “frontotemporal lobar degeneration” or “frontaltemporal dement*).ti,ab.

81. "cognit* impair*".ti,ab.

82. (cognit* adj4 (disorder* or declin* or fail* or function* or degenerat* or deteriorat*)).ti,ab.

83. (memory adj3 (complain* or declin* or function* or disorder*)).ti,ab.

84. or/75‐83

85. exp "sensitivity and specificity"/

86. "reproducibility of results"/

87. (predict* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

88. (identif* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

89. (discriminat* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

90. (distinguish* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

91. (differenti* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

92. diagnos*.ti.

93. di.fs.

94. sensitivit*.ab.

95. specificit*.ab.

96. (ROC or "receiver operat*").ab.

97. Area under curve/

98. ("Area under curve" or AUC).ab.

99. (detect* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

100. sROC.ab.

101. accura*.ti,ab.

102. (likelihood adj3 (ratio* or function*)).ab.

103. (conver* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

104. ((true or false) adj3 (positive* or negative*)).ab.

105. ((positive* or negative* or false or true) adj3 rate*).ti,ab.

106. or/85‐105

107. exp dementia/di

108. Cognition Disorders/di [Diagnosis]

109. Memory Disorders/di

110. or/107‐109

111. *Neuropsychological Tests/

112. *Questionnaires/

113. Geriatric Assessment/mt

114. *Geriatric Assessment/

115. Neuropsychological Tests/mt, st

116. "neuropsychological test*".ti,ab.

117. (neuropsychological adj (assess* or evaluat* or test*)).ti,ab.

118. (neuropsychological adj (assess* or evaluat* or test* or exam* or battery)).ti,ab.

119. Self report/

120. self‐assessment/ or diagnostic self evaluation/

121. Mass Screening/

122. early diagnosis/

123. or/111‐122

124. 74 or 123

125. 110 and 124

126. 74 or 123

127. 84 and 106 and 126

128. 74 and 106

129. 125 or 127 or 128

130. exp Animals/ not Humans.sh.

131. 129 not 130

Appendix 2. Appendix 2: QUADAS‐2

| Domain | Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and timing |

| Description | Describe methods of patient selection: describe included patients (prior testing, presentation, intended use of index test and setting) | Describe the index test and how it was conducted and interpreted | Describe the reference standard and how it was conducted and interpreted | Describe any patients who did not receive the index test(s) and/or reference standard or who were excluded from the 2 x 2 table (refer to flow diagram): describe the time interval and any interventions between index test(s) and reference standard |

| Signalling questions (yes, no, unclear) | Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Was a case‐control design avoided? Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? |

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? |

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? |

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Did all patients receive the same reference standard? Were all patients included in the analysis? |

|

Risk of bias: (high, low, unclear) |

Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? | Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? | Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? | Could the patient flow have introduced bias? |

|

Concerns regarding applicability: (high, low, unclear) |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? | Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? | Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? | — |

Anchoring statements to assist with assessment of risk of bias

Domain 1: patient selection

Risk of bias: could the selection of patients have introduced bias? (high, low, unclear)

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled?

Where sampling is used, the methods least likely to cause bias are consecutive sampling or random sampling, which should be stated and/or described. Non‐random sampling or sampling based on volunteers is more likely to be at high risk of bias.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Was a case‐control design avoided?

Case‐control study designs have a high risk of bias, but sometimes they are the only studies available especially if the index test is expensive and/or invasive. Nested case‐control designs (systematically selected from a defined population cohort) are less prone to bias but they will still narrow the spectrum of patients that receive the index test. Study designs (both cohort and case‐control) that may also increase bias are those designs where the study team deliberately increase or decrease the proportion of participants with the target condition, for example a population study may be enriched with extra dementia participants from a secondary care setting.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions?

We will automatically grade the study as unclear if exclusions are not detailed (pending contact with study authors). Where exclusions are detailed, we will grade the study as 'low risk' if exclusions are felt to be appropriate by the review authors. Certain exclusions common to many studies of dementia are: medical instability; terminal disease; alcohol/substance misuse; concomitant psychiatric diagnosis; other neurodegenerative condition. However if 'difficult to diagnose' groups are excluded this may introduce bias, so exclusion criteria must be justified. For a community sample we would expect relatively few exclusions. We will label post hoc exclusions 'high risk' of bias.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Applicability: are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? (high, low, unclear)

The included patients should match the intended population as described in the review question. If not already specified in the review inclusion criteria, setting will be particularly important – the review authors should consider population in terms of symptoms; pre‐testing; potential disease prevalence. We will classify studies that use very selected participants or subgroups as having low applicability, unless they are intended to represent a defined target population, for example, people with memory problems referred to a specialist and investigated by lumbar puncture.

Domain 2: index test

Risk of bias: could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? (high, low, unclear)

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the reference standard?

Terms such as 'blinded' or 'independently and without knowledge of' are sufficient and full details of the blinding procedure are not required. This item may be scored as 'low risk' if explicitly described or if there is a clear temporal pattern to the order of testing that precludes the need for formal blinding, i.e. all (neuropsychological test) assessments were performed before the dementia assessment. As most neuropsychological tests are administered by a third party, knowledge of dementia diagnosis may influence their ratings; tests that are self administered, for example using a computerized version, may have less risk of bias.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Were the index test thresholds pre‐specified?

For neuropsychological scales there is usually a threshold above which participants are classified as 'test positive'; this may be referred to as threshold, clinical cut‐off or dichotomiation point. Different thresholds are used in different populations. A study is classified as at higher risk of bias if the authors define the optimal cut‐off post hoc based on their own study data. Certain papers may use an alternative methodology for analysis that does not use thresholds and these papers should be classified as not applicable.

Weighting: low risk of bias

Were sufficient data on (neuropsychological test) application given for the test to be repeated in an independent study?

Particular points of interest include method of administration (for example self completed questionnaire versus direct questioning interview); nature of informant; language of assessment. If a novel form of the index test is used, for example a translated questionnaire, details of the scale should be included and a reference given to an appropriate descriptive text, and there should be evidence of validation.

Weighting: low risk of bias

Applicability: are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? (high, low, unclear)

Variations in the length, structure, language, and/or administration of the index test may all affect applicability if they vary from those specified in the review question.

Domain 3: reference standard

Risk of bias: could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? (high, low, unclear)

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition?

Commonly used international criteria to assist with clinical diagnosis of dementia include those detailed in DSM‐IV and ICD‐10. Criteria specific to dementia subtypes include but are not limited to NINCDS‐ADRDA criteria for Alzheimer's dementia; McKeith criteria for Lewy Body dementia; Lund criteria for frontotemporal dementias; and the NINDS‐AIREN criteria for vascular dementia. Where the criteria used for assessment are not familiar to the review authors and Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement, this item should be classified as 'high risk of bias'.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test?

Terms such as 'blinded' or 'independent' are sufficient and full details of the blinding procedure are not required. This may be scored as 'low risk' if explicitly described or if there is a clear temporal pattern to order of testing, i.e. all dementia assessments performed before (neuropsychological test) testing.

Informant rating scales and direct cognitive tests present certain problems. It is accepted that informant interview and cognitive testing is a usual component of clinical assessment for dementia, however specific use of the scale under review in the clinical dementia assessment should be scored as high risk of bias.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Was sufficient information on the method of dementia assessment given for the assessment to be repeated in an independent study?

Particular points of interest for dementia assessment include the training/expertise of the assessor, whether additional information was available to inform the diagnosis (for example neuroimaging, other neuropsychological test results), and whether this was available for all participants.

Weighting: variable risk, but high risk if method of dementia assessment not described

Applicability: are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? (high, low, unclear)

There is the possibility that some methods of dementia assessment, although valid, may diagnose a far smaller or larger proportion of participants with disease than in usual clinical practice. For example, currently the reference standard for vascular dementia may under‐diagnose compared to usual clinical practice. In this instance the item should be rated as having poor applicability.

Domain 4: patient flow and timing

Risk of bias: could the patient flow have introduced bias? (high, low, unclear)

Was there an appropriate interval between the index test and reference standard?

For a cross‐sectional study design, there is potential for the subject to change between assessments, however dementia is a slowly progressive disease, which is not reversible. The ideal scenario would be a same‐day assessment, but longer periods of time (for example, several weeks or months) are unlikely to lead to a high risk of bias. For delayed‐verification studies the index and reference tests are necessarily separated in time given the nature of the condition.

Weighting: low risk of bias

Did all participants receive the same reference standard?

There may be scenarios where participants who score 'test positive' on the index test have a more detailed assessment for the target condition. Where dementia assessment (or reference standard) differs between participants this should be classified as high risk of bias.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Were all participants included in the final analysis?

Attrition will vary with study design. Delayed verification studies will have higher attrition than cross‐sectional studies due to mortality, and it is likely to be greater in participants with the target condition. Dropouts (and missing data) should be accounted for. Attrition that is higher than expected (compared to other similar studies) should be treated as a high risk of bias. We have defined a cut‐off of greater than 20% attrition as being high risk but this will be highly dependent on the length of follow‐up in individual studies.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Data

Presented below are all the data for all of the tests entered into the review.

Tests. Data tables by test.

| Test | No. of studies | No. of participants |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Mini‐Cog | 4 | 1517 |

1. Test.

Mini‐Cog.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Carnero‐Pardo 2013.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Patients were recruited from 2 cities in Spain, Madrid and Granada. There was 1 site in Madrid and 3 unique sites in Granada. Neuropsychological testing for the reference standard of all participants was completed in a tertiary care setting. The study procedures for the Madrid and Granada sites differed and the information from the Granada site was used in the analysis. | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Participants were prospectively identified from primary care by primary care physicians identifying individuals who presented with cognitive complaints or who were suspected of having cognitive disorders by their primary care physicians. Individuals with known cognitive impairment prior to administration of the Mini‐Cog and reference standard were excluded. Number of participants: dementia: 49, no dementia: 93 Participant mean age (SD): 72.1 (11.4) Gender: 103 women, 39 men Education: < primary school: 72 (50.7%) Dementia: 49 (34.5%), no dementia: 93 (65.5) Mean MMSE scores (SD): 19.9 (5.7) |

||

| Index tests | Mini‐Cog was derived from the MMSE and clock drawing test. In the Granada subsample, the Mini‐Cog was performed independent of the reference standard assessment and only information from the Granada sample was used for the analysis. | ||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Dementia according to DSM IV TR performed by 2 neurologists | ||

| Flow and timing | Timing of index and reference test unclear | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | |||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | No | ||

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Yes | ||

| High | High | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test All tests | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Yes | ||

| Low | |||

Fuchs 2012.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Participants were randomly selected from medical records of 138 primary practices in 1/6 German metropolitan study centres. Patients with baseline dementia were excluded. Participants had to have at least 1 contact with primary care physician within the year preceding enrolment. | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Patients who were home‐care visits only, residing in nursing home, or having illness potentially fatal within 3 months, were excluded. Patients with insufficient German‐speaking capabilities, deafness, or blindness were also excluded. All patients within participating practices aged 75‐89 years old were eligible to be selected. Number of participants: dementia: 21, no dementia: 402 Participant mean age (SD): dementia: 82.4 (3.4), no dementia: 82.4 (3.2) Female gender: dementia (68.7%), no dementia (61.9%) Education level: variable, dementia "low education" (62.2%), no dementia "low education" (61.9%) |

||

| Index tests | Mini‐Cog administered with original scoring, as per Borson 2000 | ||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Dementia based on the criteria of DSM‐IV, NINCDS‐ADRDA, NINCDS‐AIREN as evaluated in a conference between the interviewer and study co‐ordinator. Evaluation based on SIDAM test results, interview data, informant's information, primary care provider survey and SISCO results. | ||

| Flow and timing | Data available for all except 9 participants. | ||

| Comparative | |||