Abstract

Injury to a fetus or neonate during delivery can be due to several factors involving the fetus, placenta, mother, and/or instrumentation. Birth asphyxia results in hypoxia and ischemia, with global damage to organ systems. Birth trauma, that is mechanical trauma, can also cause asphyxia and/or morbidity and mortality based on the degree and anatomic location of the trauma. Some of these injuries resolve spontaneously with little or no consequence while others result in permanent damage and severe morbidity. Unfortunately, some birth injuries are fatal. To understand the range of birth injuries, one must know the risk factors, clinical presentations, pathology and pathophysiology, and postmortem autopsy findings. It is imperative for clinicians and pathologists to understand the causes of birth injury; recognize the radiographic, gross, and microscopic appearances of these injuries; differentiate them from inflicted postpartum trauma; and work to prevent future cases.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Birth trauma, Birth injury, Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, Dystocia, Neonate

Introduction

Birth injury is a general term used to describe any injury to a fetus or neonate during labor and delivery, frequently during the second stage of labor in which the fetus descends through the birth canal (1). Some use the terms birth injury and birth trauma interchangeably. Birth trauma can also refer to a subcategory of birth injury involving hypoxia/ischemia and mechanical forces, including those resulting in failure of progression (2 –6). Severe birth asphyxia and hypoxia is essentially a cardiorespiratory problem with significant brain damage. However, the global nature of the hypoxic ischemic insult and the myriad of biochemical disruptions that follow can cause significant injury to many organ systems. This review of birth trauma will use the latter definition to discuss common and not so common types of injury.

Discussion

Birth Asphyxia

Birth asphyxia, also referred to as neonatal depression or hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, is a condition characterized by an impairment of exchange of the respiratory gases (oxygen and carbon dioxide) resulting in hypoxemia and hypercapnia, accompanied by metabolic acidosis. Each year, approximately four million neonates experience birth asphyxia resulting in approximately 1.2 million deaths worldwide. Those who survive suffer not only brain damage but also multiorgan injury (3). Approximately 20% of cases will not exhibit injury outside of the brain.

There are many risk factors for birth asphyxia (see Table 1). With birth asphyxia, there is a partial or complete lack of oxygen to vital organs resulting in progressive hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and ischemia. This results in anaerobic glycolysis and lactic acidosis. The main outcome in the brain is hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) causing mental and physical disabilities, seizures, and cerebral palsy (Images 1 -7) (3, 4, 7).

Table 1:

Risk Factors for Birth Asphyxia.

| Maternal diabetes |

| Maternal short stature |

| Maternal fever |

| Maternal anemia |

| Maternal infection, chorioamnionitis |

| Hypertension, preeclampsia and eclampsia, chronic hypertension (CHTN) |

| Maternal age extremes (<16 and >35 years) |

| Maternal thyroid disease |

| Antepartum hemorrhage (maternal or fetal origin) |

| Uterine rupture |

| Cephalopelvic disproportion |

| Head entrapment (especially with breech) |

| Non-cephalic presentation, breech |

| Intrauterine passage of meconium |

| Prematurity |

| Intrauterine growth restriction |

| Umbilical cord complications (e.g., prolapsed, nuchal) |

| Placental abruption (>50%) |

| Postmaturity |

| Fetal macrosomia |

| Congenital malformations/deformations, genetic abnormalities |

| Multiple gestations |

| Primagravida |

| Prolonged rupture of membranes |

| Premature rupture of membranes |

| Oxytocin |

| Prolonged labor |

| Oligohydramnios |

| Fetal anemia or hypovolemia (ruptured vasa previa or fetal maternal transfusion) |

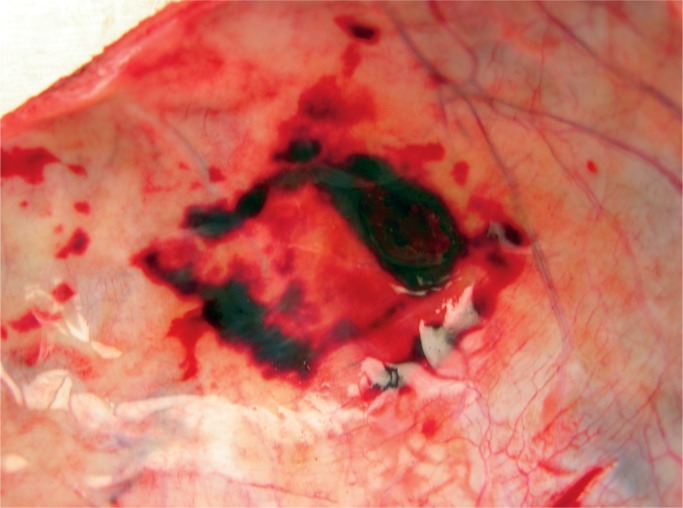

Image 1:

Multiple infarcts are present within this placenta. They are of different ages and some have central hemorrhage (infarction hematoma). These changes are almost always present in preterm preeclampsia and can be associated with fetal hypoxia-ischemia.

Image 2:

Nonmacerated stillborn with meconium stained skin. Meconium staining of the skin and finger nails occurs after a minimum of four to six hours of exposure.

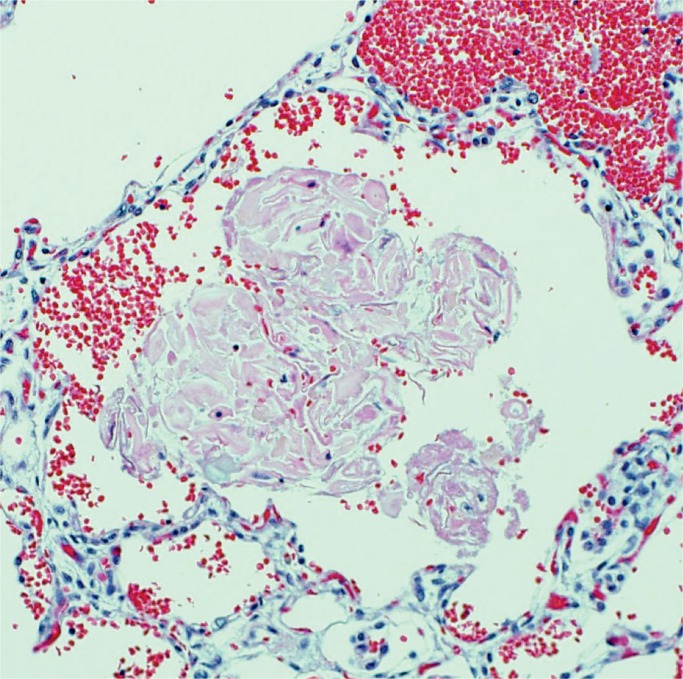

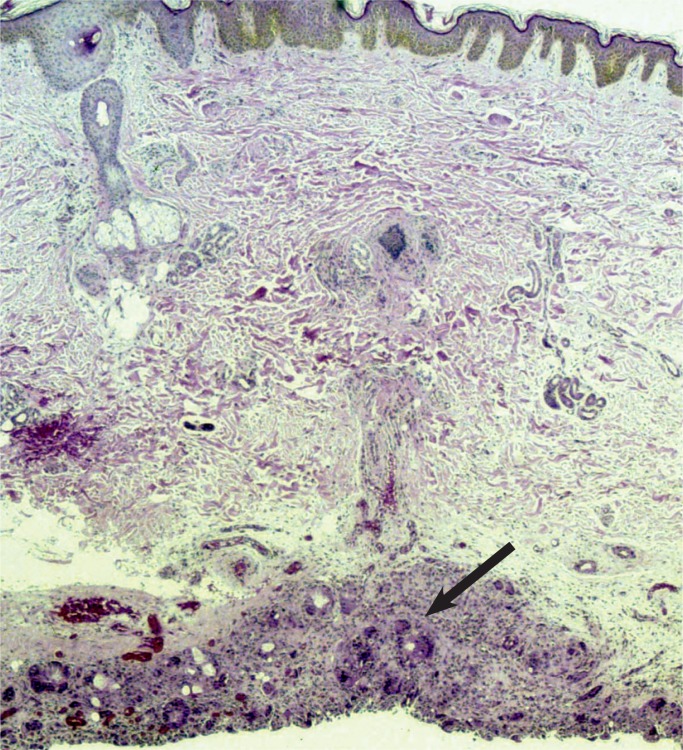

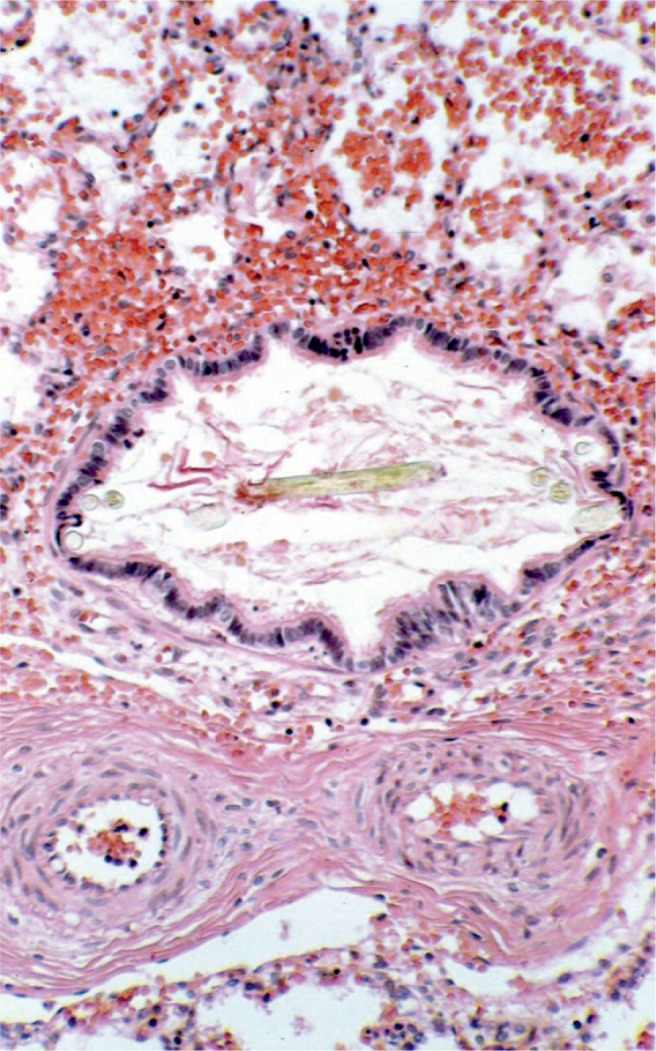

Image 3:

Meconium aspiration results in plugging of the airways with amniotic fluid debris (e.g., hair, squamous epithelium), which will result in poor oxygenation and ventilation at birth. The musculature of the pulmonary arteries is thickened, which results in pulmonary hypertension and difficulty in oxygenating the baby (H&E, x200).

Image 4:

Fetal surface of the placenta with heavy meconium soilage. Meconium passage in utero occurs in 19% of term placentas. Discoloration of the membranes and umbilical cord occurs after prolonged exposure to meconium. Two percent of babies with meconium will have meconium aspiration syndrome. The most common cause for meconium soilage is chorioamnionitis, followed by problems with either fetal blood flow or maternal blood flow.

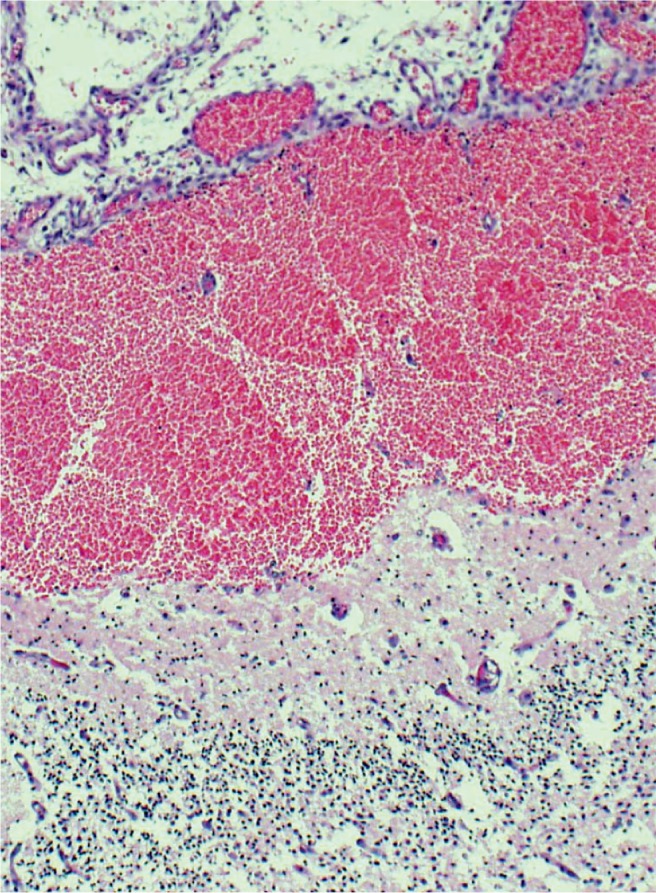

Image 5:

A more subtle feature of in utero stress is aspiration of amniotic fluid debris. A small amount of this debris is always present in the lungs but with gasping the amount will be increased and distend the alveoli and plug airways (H&E, x200).

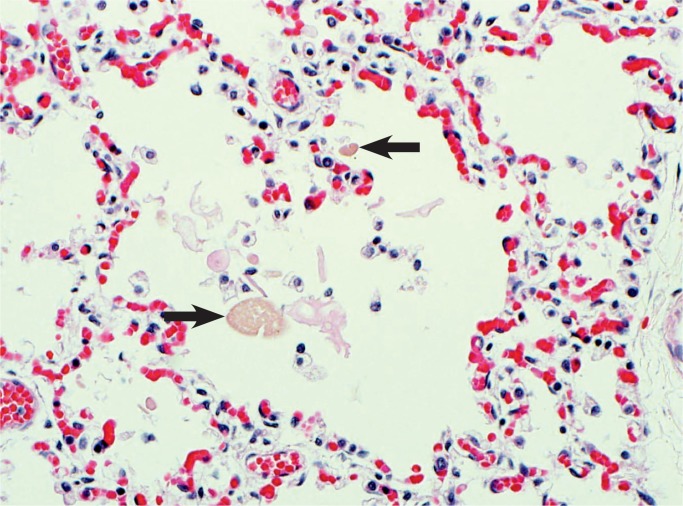

Image 6:

Meconium aspiration can also be subtle. Here there is amniotic fluid debris in the alveolus, but there are also smooth oval pigmented meconium bodies from the bowel contents (arrows). Macrophages and rare neutrophils are also seen as an inflammatory reaction to the meconium (H&E, x200).

Image 7:

Severe cyanosis of the fingernails occurs with severe problems in fetal oxygenation such as with umbilical cord prolapse. It may also occur after delivery due to cyanotic heart disease, esophageal intubation, or pulmonary hypoplasia.

With birth asphyxia, the body redistributes the cardiac output to maintain perfusion of vital organs including the brain, adrenal glands, and heart at the expense of the gastrointestinal system, kidney, and liver (8, 9). The less vital organs deprived of flow experience vasoconstriction, redistribution of blood flow, and decreased oxygen delivery. This redistribution of cardiac output is the direct result of vasoconstriction in nonvital organs and vasodilation in vital organs such as the brain and the heart (8).

Brain

If perfusion is not maintained to the brain, selective neuronal necrosis can occur and may result the clinical syndrome of HIE, which has been defined by the Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy (10). The infant is susceptible to different regional patterns of injury, dependent upon the severity and duration of the insult and gestational age. Cells vulnerable to hypoxia and ischemia in the hippocampus, as well as neocortical pyramidal cells, striatal neurons, and Purkinje cells will be irreversibly damaged. Periventricular hemorrhage and cerebral infarcts between zones of arterial supply are seen. There is neuronal loss, gliosis, and atrophy. Myelin can also be damaged with myelin loss in the white matter. Such changes are described in depth below (Images 8 -21).

Image 8:

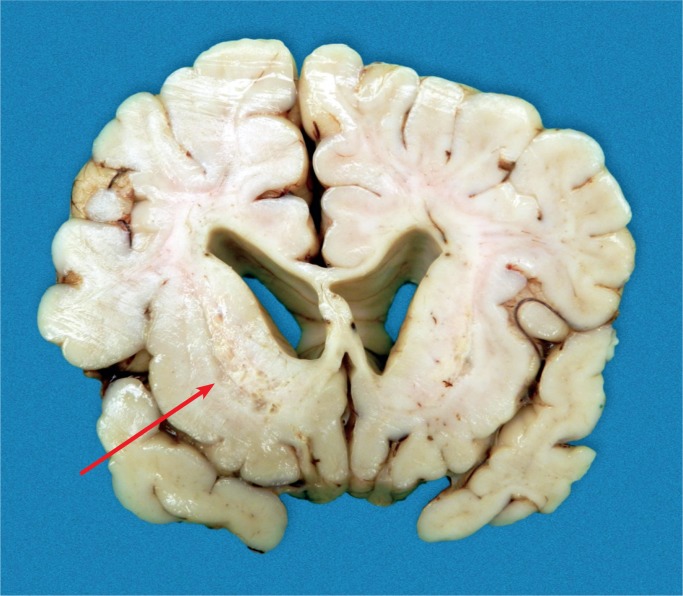

Term brain with cystic injury in the deep gray nuclei (basal ganglia, thalamus) secondary to acute profound total asphyxia.Baby survived four weeks.

Image 9:

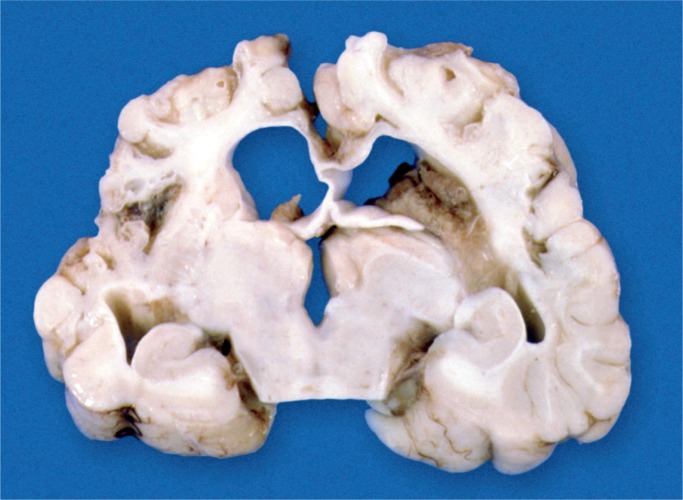

Term brain with severe white matter injury with laminar necrosis due to partial prolonged asphyxia occurring around the time of birth. The baby survived for seven weeks.

Image 10:

Status marmoratus of the basal ganglia and thalamus occurs months after injury to the deep gray matter.

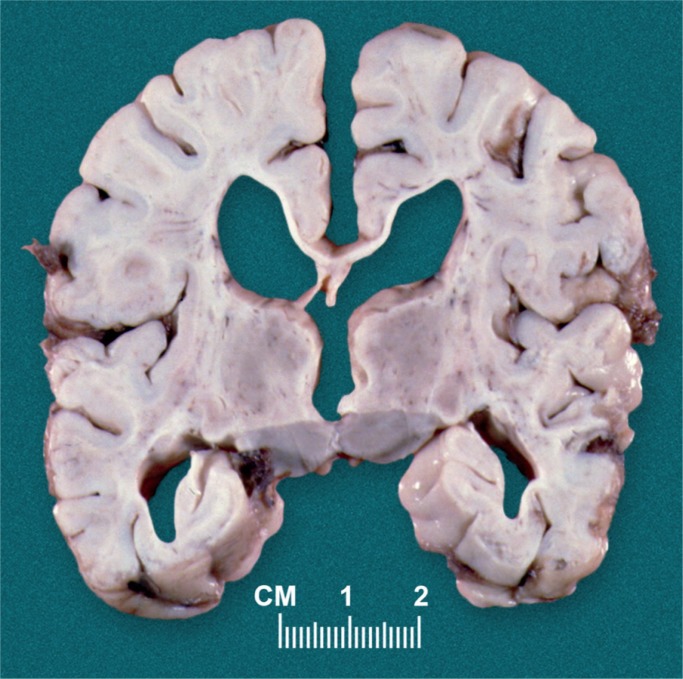

Image 11:

Microcephaly with bitemporal narrowing is the result of cortical atrophy after severe birth asphyxia.

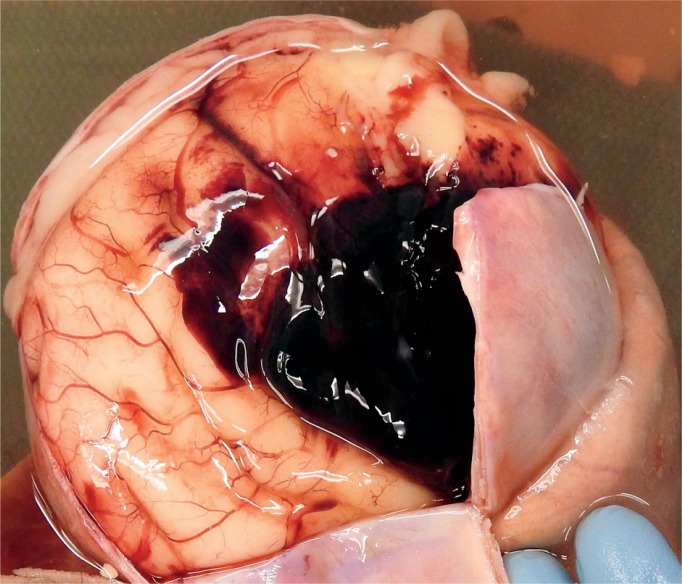

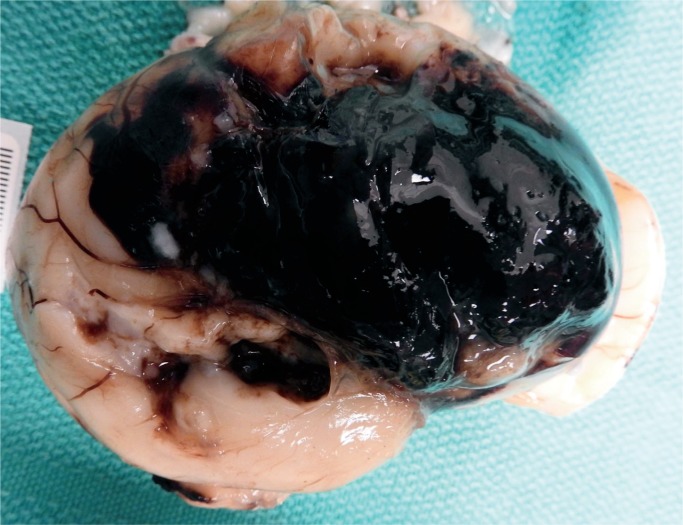

Image 12:

Large subarachnoid hemorrhage is an unusual finding secondary to acute hypoxia of birth asphyxia.

Image 13:

Same brain as Image 12 after removal which shows the full extent of the subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Image 14:

It is sometimes necessary to obtain microscopic examination of the hemorrhage to determine location. This clearly shows acute subarachnoid hemorrhage (H&E, x100).

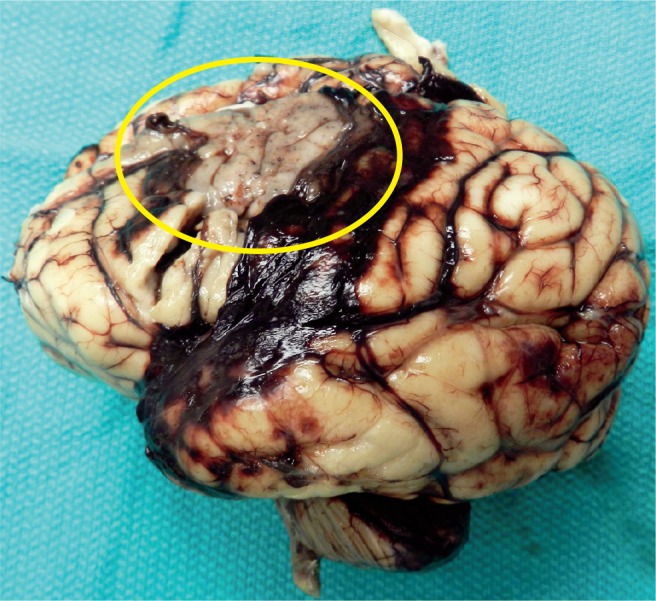

Image 15:

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is present, but there is also an area of infarction in the parietal area consistent with middle cerebral artery infarct (circle).

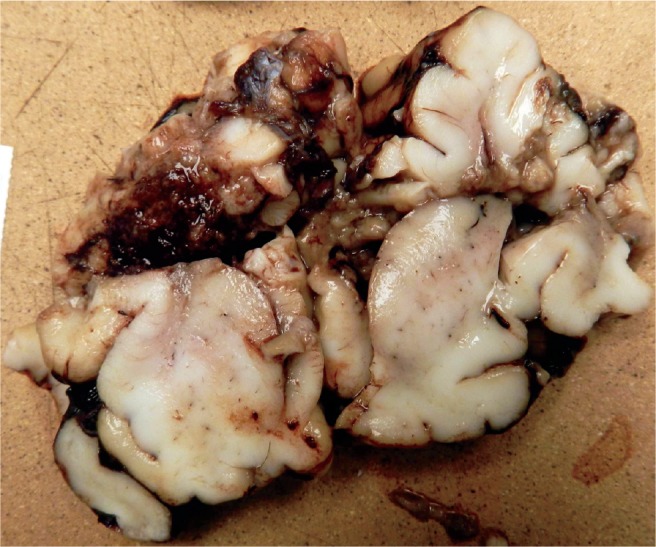

Image 16:

Cross section of the brain in Image 15 shows the massive destruction of the parietal lobe.

Image 17:

Cerebellum with Purkinje cells showing hypoxic injury with hypereosinophilia of the cytoplasm and pyknotic nuclei (H&E, x200).

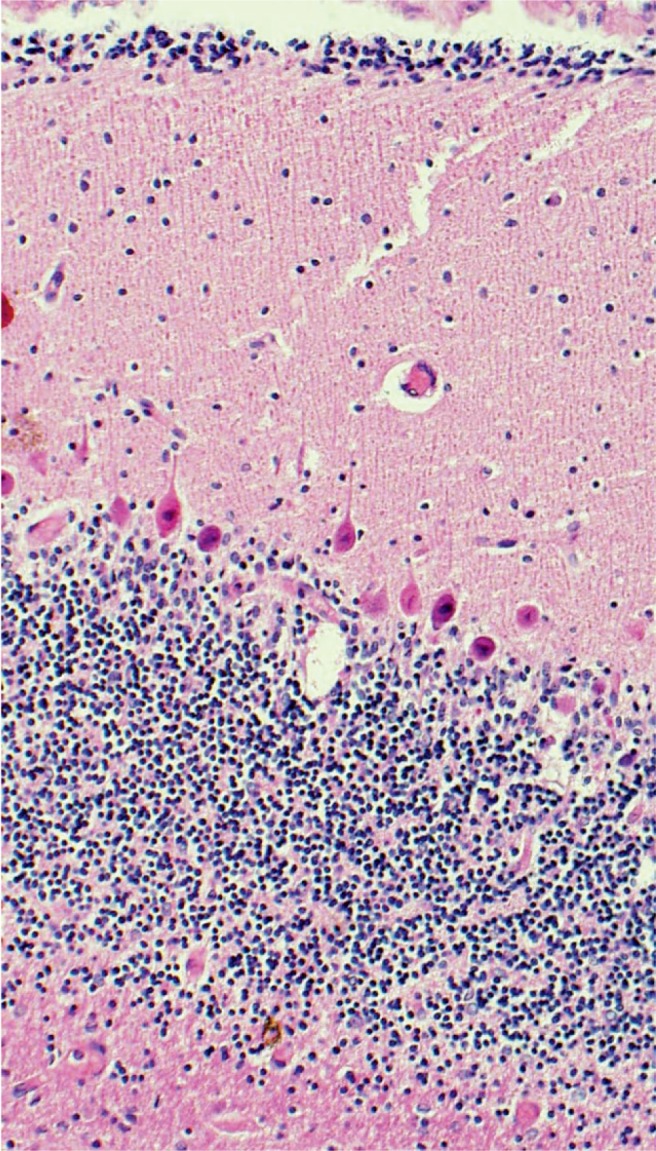

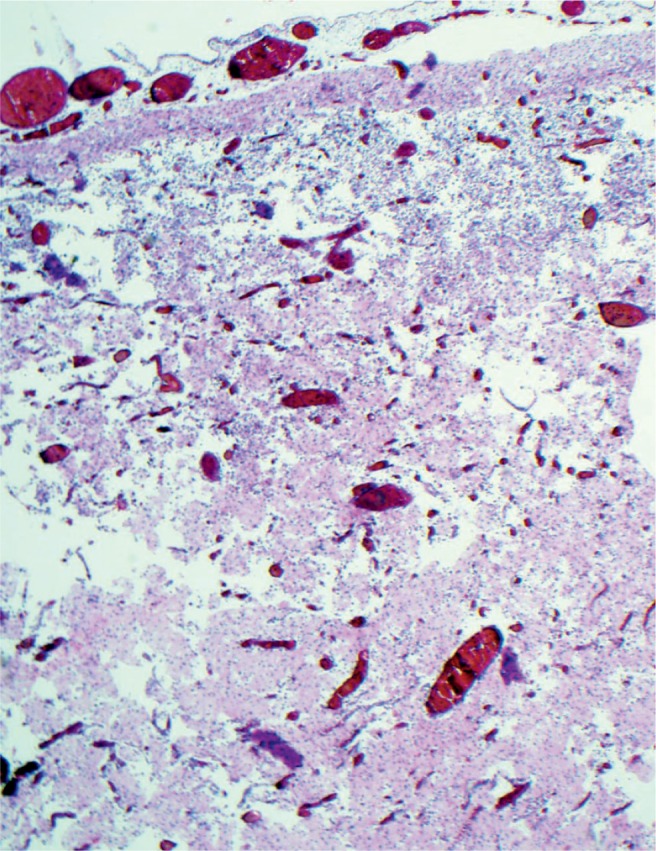

Image 18:

Cerebral laminar necrosis is the result of injury to all of the cells. There is vascular proliferation and infiltration by macrophages. This will be seen three to five days after the injury (H&E, x200).

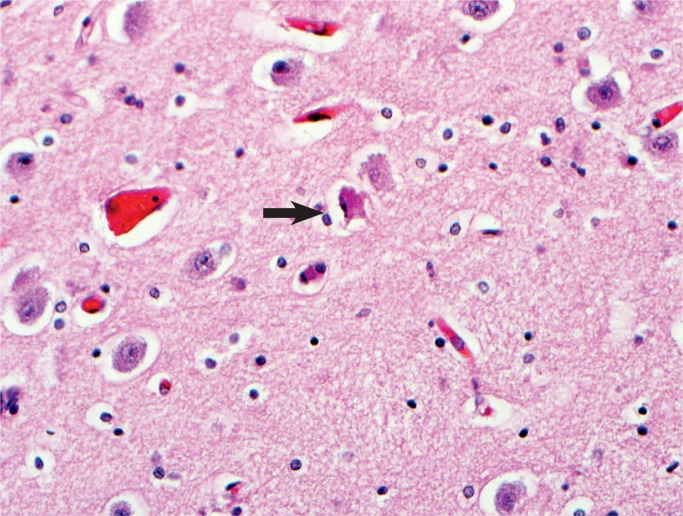

Image 19:

Cerebral cortical neurons are very sensitive to hypoxia. There is hypereosinophilia of the cytoplasm and karyorrhexis of the nuclei (arrow). The halos around the cells are evidence of edema (H&E, x400).

Image 20:

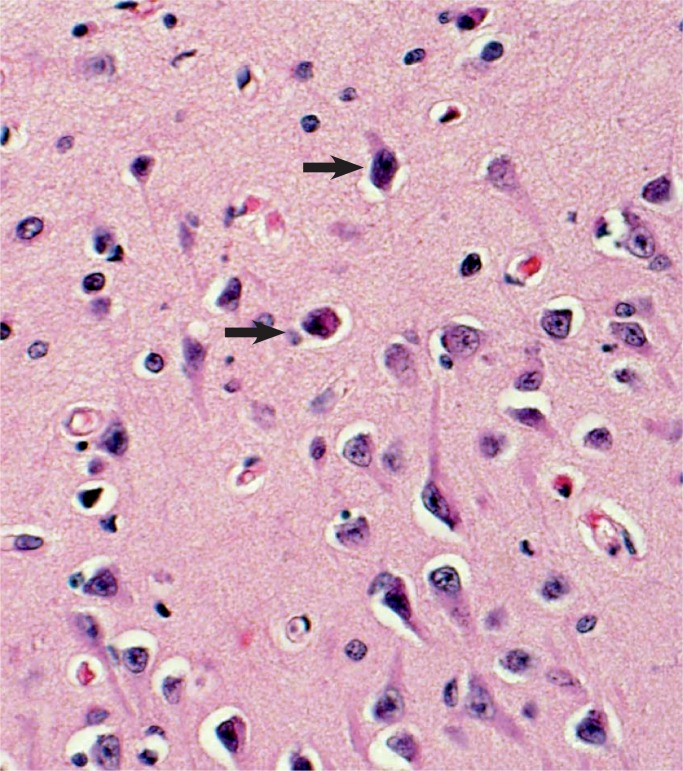

The subicular area of the hippocampus is more sensitive to hypoxia in the newborn. Arrows show hypoxic neurons (H&E, x400).

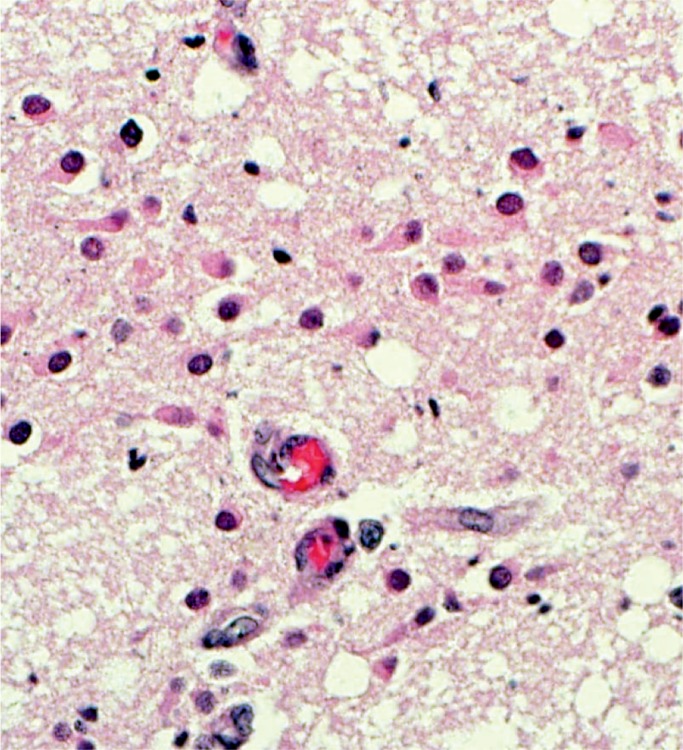

Image 21:

The base of the pons is very sensitive to hypoxic injury in the neonate. Here we see overt neuronal necrosis, a feature that occurs several days after the injury (H&E, x400).

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy occurs in 1-3/1000 births. Injury occurs during the initial event but also continues during secondary energy failure that begins 6-12 hours after the event and lasts up to 36 hours. Eight to ten percent of term infants with HIE will develop cerebral palsy. Potentiating insults such as inflammation/infection, hyperglycemia, and hypoglycemia most likely amplify the effects of decreased perfusion. There is poor correlation of chorioamnionitis with HIE in term infants; however, preterm infants are at increased risk, especially with fetal inflammatory response or sepsis (11).

Vulnerability of cells to hypoxia varies and are listed here from most sensitive to least sensitive: neurons, oligodendroglia, astrocytes, and microglia. Certain cells are also more or less sensitive to hypoxia, listed here in decreasing order of sensitivity: parasagittal cortex, hippocampus lateral cortex, dentate gyrus, amygdala, and thalamus. Neurons with higher rate of energy usage and higher glutamate receptors are more likely to be injured (see Table 2).

Table 2:

Vulnerability/Sensitivity of Cells to Hypoxia.

| Cell | Most-to-Least Sensitive to Hypoxia |

|---|---|

| Neurons | Most sensitive |

| Parasagittal cortex Hippocampus lateral cortex Dentate gyrus Amygdala Thalamus |

|

| Oligodendroglia | |

| Astrocytes | |

| Microglia | Least sensitive |

The most common patterns of neurologic injury found in HIE for both term and preterm infants can be divided into: selective neuronal necrosis, parasagittal cerebral injury, periventricular leukomalacia, and ischemic necrosis or stroke (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3:

Patterns of Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy Neurologic Injury.

| Pattern |

|---|

| Selective neuronal necrosis |

| Parasagittal cerebral injury |

| Periventricular leukomalacia |

| Ischemic necrosis or stroke |

Table 4:

Temporally Related Microscopic Changes of Selective Neuronal Injury.

| 12-48 hours | Eosinophilia of the cytoplasm, pyknosis, or karyorrhexis of the nuclei with cellular swelling |

| Several days | Overt neuronal necrosis with appearance of microglial cells, endothelial swelling. Global edema occurs and is generally thought to be cytotoxic edema due to the cellular injury |

| 3-5 days | Overt neuronal necrosis with hypertrophic astrocytes, vascular proliferation, infiltration with macrophages |

| 8-14 days | Calcifications |

| Several weeks | Atrophy with gliosis |

| Many months | Status marmoratus of the basal ganglia and thalamus |

Selective Neuronal Necrosis

Selective neuronal necrosis can be broken down into five different patterns, though there is considerable overlap in these patterns (12, 13).

First, partial prolonged chronic asphyxia is secondary to moderate-severe and prolonged decrease in blood flow to the brain that may evolve in a gradual manner. Flow is shunted from the anterior to the posterior circulation to maintain adequate perfusion of the brain stem, cerebellum, and basal ganglia. This is predominately a white matter injury involving the neurons of the cerebral cortex, pyramidal cells of hippocampus (Sommer’s sector), anterior horn cells of spinal cord, and Purkinje cells and granular cell layers of the cerebellum. Partial prolonged injury is associated with features of decreased maternal uteroplacental blood flow, severe fetal anemia, high-grade chronic villitis, and fetal thrombotic vasculopathy. It occurs in 19-54% of term infants with HIE (12).

Secondly, profound acute, near total asphyxia is usually a severe and abrupt event that results in injury to the deep gray matter. This is predominately a gray matter injury that involves the deep nuclei (basal ganglia [caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus], thalamus), the midbrain (inferior olivary nuclei), parasagittal perirolandic cortex, and brainstem. Near total asphyxia is associated with uterine rupture, placental abruption, cord prolapse, and ruptured vasa previa. It occurs in 17-30% of term infants with HIE (12). This is the form of HIE that may not have multiorgan system injury.

Thirdly, total injury involves both deep gray and white matter injury. This is generally due to very severe and very prolonged injury or a chronic injury with a superimposed acute injury. A fetus affected by chronic hypoxia is much more susceptible to an acute injury. Total injury is seen in 27-41% of term infants with HIE (12, 13).

Fourthly, in the preterm fetus, selective neuronal necrosis may include the above patterns, but the primary areas of injury include pontosubicular necrosis with neuronal injury noted in the lateral base of the pons, subiculum of the hippocampus, and the dentate nucleus of the cerebellum. There is a strong association with periventricular leukomalacia.

Finally, cerebellar injury is also particular to premature infants less than 27 weeks gestation and especially of extremely low birth weight, those infants weighing less than 1000 g. Cerebellar injury results in symmetric cerebellar hemisphere hypoplasia and is almost always associated with some degree of cerebral white matter and brainstem injury.

Parasagittal Cerebral Injury

Parasagittal cerebral injury is an injury of the term neonate. The parasagittal cortex of the parietal-occipital region is more severely affected than the anterior due to the vascular anatomy in the watershed areas of the cerebral cortex and subcortical white matter in the depths of the sulci. It is usually a nonhemorrhagic lesion. The lesion is identified in 45% of neonates with HIE (12, 13). The injury is severe and many infants do not survive. Survivors may develop cortical laminar necrosis or ulegyria.

Periventricular Leukomalacia

Periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) is the result of necrosis of the white matter dorsal and lateral to the external angles of the lateral ventricles. Focal necrosis with subsequent cyst formation is the classic form. Microscopic areas of necrosis with diffuse glial scaring has been more recently described as a secondary form, recently identified by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), not identified by ultrasound (Table 5) (13).

Table 5:

Progression of Periventricular Leukomalacia Over Time (13).

| 6-12 hours | Coagulation necrosis of all elements in the area. Pyknotic glial nuclei and round neuroaxonal swelling is prominent at the periphery of the lesion. Astrocytic proliferation and capillary hyperplasia present. |

| 7 days | Infiltration by activated microglia, proliferation of hypertrophic astrocytes, endothelial hyperplasia, and appearance of foamy macrophages. |

| 1-4 weekss | Tissue dissolution and cavity formation, hypomyelination, and ventriculomegaly. |

Periventricular leukomalacia is a lesion found in 4-26% of infants born between 26-32 weeks gestation (14). The incidence of PVL varies significantly in different institutions and different studies. The lesion is also progressive over the time from birth to “term,” which may account for some of the differences in reported incidence. This is primarily injury to immature oligodendrocytes, which are second only to neurons in their sensitivity to hypoxia (Table 2) (13)

Clinical features associated with PVL include cerebral ischemia, hypotension, prolonged preterm rupture of membranes, and clinical perinatal infection (14). Approximately 66-100% of preterm babies with PVL will develop cerebral palsy, usually spastic diplegia (14).

Intraventricular Hemorrhage

Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) is a lesion of preterm infants. The incidence is approximately 12.5% of infants born at 27-33 weeks gestation and most occur at three to four days of life (13). Etiology is usually secondary to hemodynamic disturbance. The premature infant is unable to autoregulate its blood pressure under 26 weeks gestation and increased venous pressure may result in disruption of thin-walled vessels in the germinal matrix. Intrauterine or intrapartum IVH can occur, often secondary to cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and less commonly due to neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia.

Ischemic Necrosis/Stroke

Perinatal stroke is uncommon, occurring in approximately one in 4000 term neonates. Most are asymptomatic, only later identified with unilateral weakness and less commonly as HIE. The most common location is the middle cerebral artery. The majority are ischemic, three times more common than hemorrhagic. The most common presenting feature is seizure. The origin of the stroke is often placental vascular thrombosis with embolization, which can be due to obstruction of blood flow in the umbilical cord or fetal vasculitis associated with chorioamnionitis. Additional etiologies include inherited thrombophilias, cardiac disease, vascular malformations, trauma, or asphyxia. Polycythemia in an infant of a diabetic mother has an increased risk for renal vein thrombosis and embolization with stroke (15). Venous thrombosis is more often secondary to inherited thrombophilias and can also be secondary to severe meningitis.

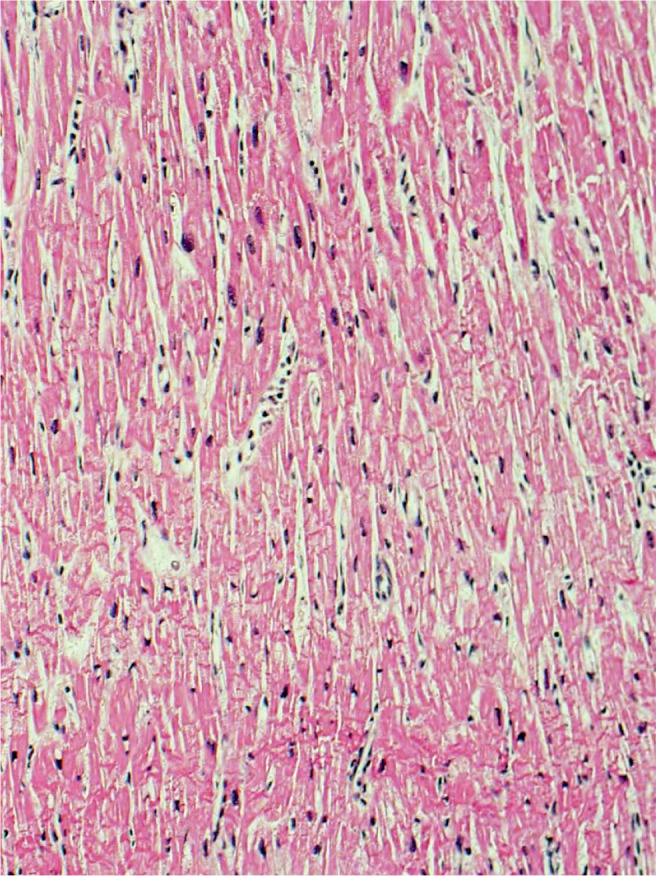

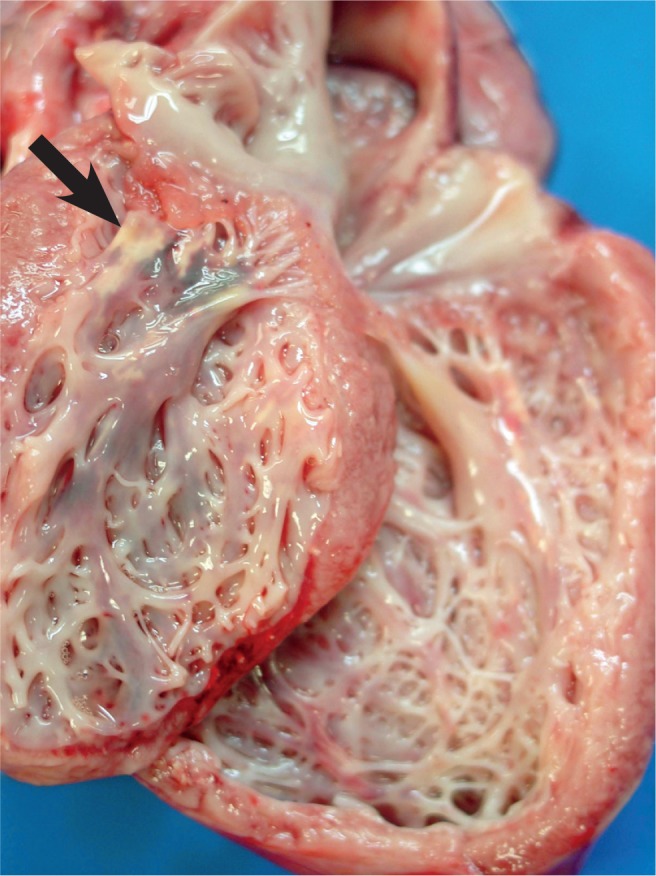

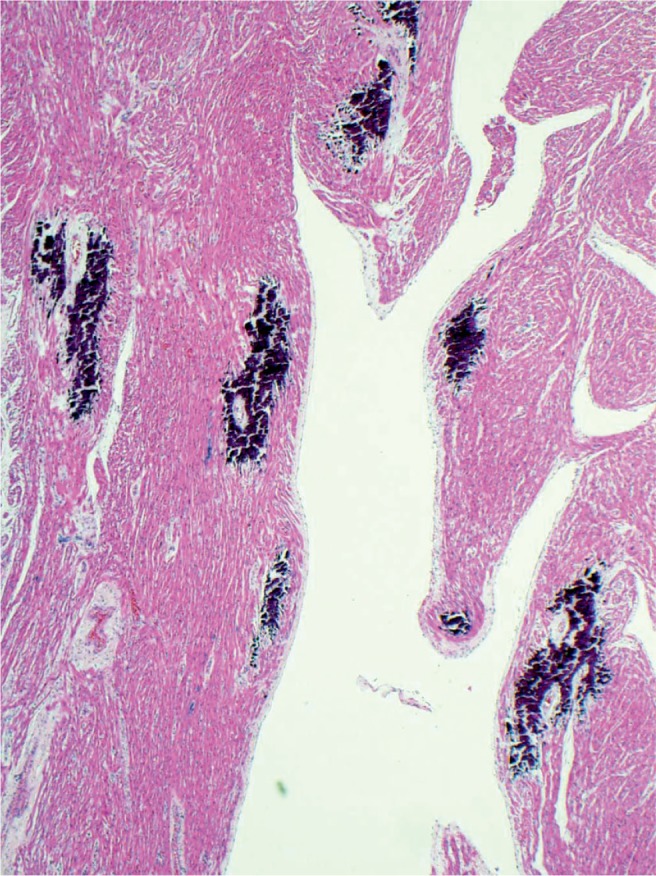

Heart

Progressive asphyxia will lead to circulatory deterioration, myocardial dysfunction, and cardiogenic shock (8, 16). The effect is an overall hemodynamic instability. The heart rate and stroke volume decreased, leading to lowered cardiac output. The results include dysrhythmia, valve dysfunction, bradycardia, decreased contractility, and hypotension. Acidosis and poor perfusion lead to ischemic cardiac injury (Images 22 -33). Microscopically, one can see contraction band necrosis, coagulation necrosis, and phagocytosis of myocytes. This necrosis is especially apparent in the papillary muscle. Infarction is subendocardial and does not follow the usual pattern of the coronary artery perfusion as in adults. The microscopic changes after ischemia are presumed to be similar to that of an adult myocardial infarction.

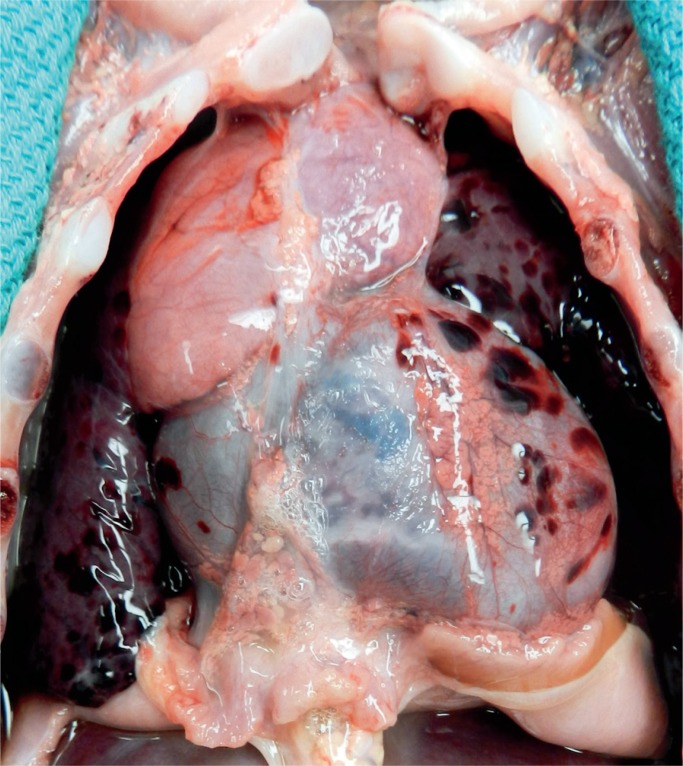

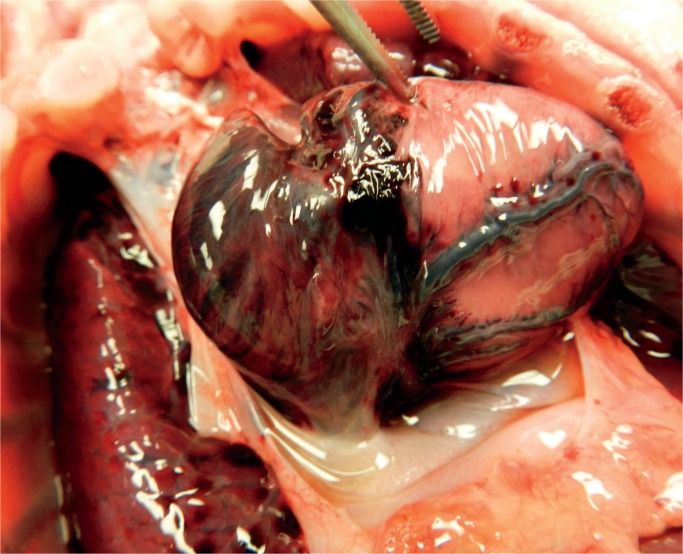

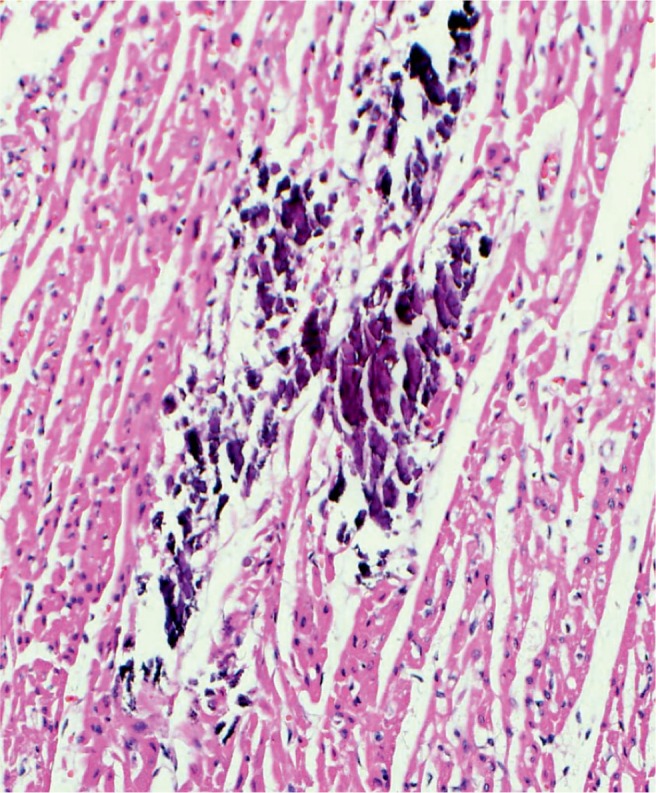

Image 22:

A classic sign of asphyxia is petechiae. Here they are present on the pericardium and visceral pleura of the lungs. The anterior thymus has no petechiae, but examination of the posterior surface showed significant petechiae.

Image 23:

Hemorrhage on the epicardium can be petechial but often is found along the path of the coronary arteries. The arteries themselves are usually normal, but rare cases of fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall occurs.

Image 24:

Epicardial petechiae secondary to hypoxic ischemic injury (H&E, x40).

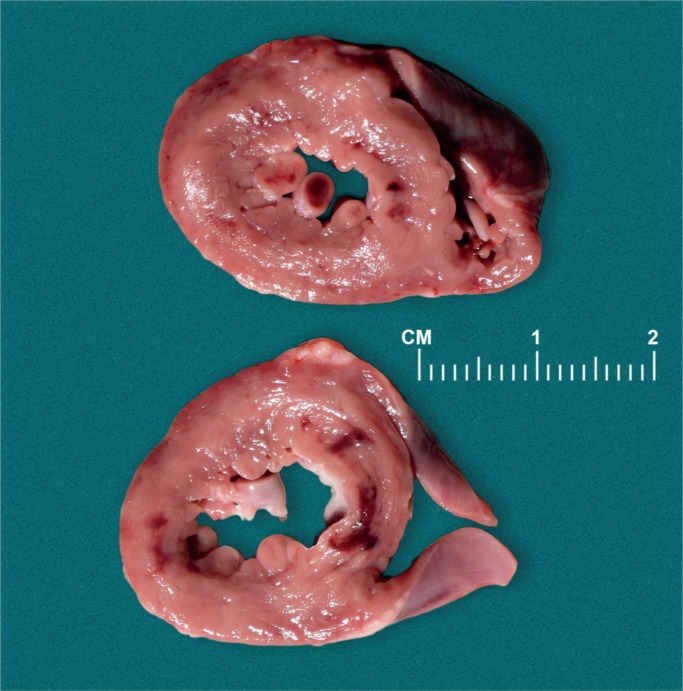

Image 25:

In the infant, acute myocardial hypoxia-ischemia results in injury first to the papillary muscles and then the subendocardial myometrium of the ventricles. Note the location of the hyperemia. The injury does not follow the pattern of myocardial infarction due to obstruction of the coronary arteries.

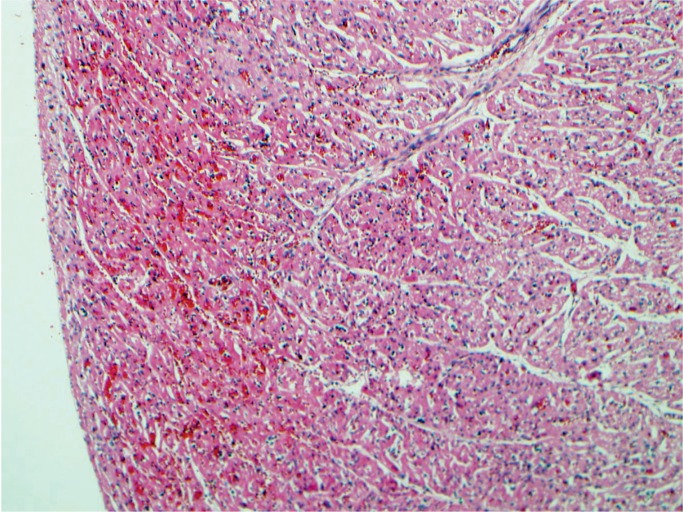

Image 26:

Subendocardial ischemia with hemorrhage in this area of the heart (H&E, x100).

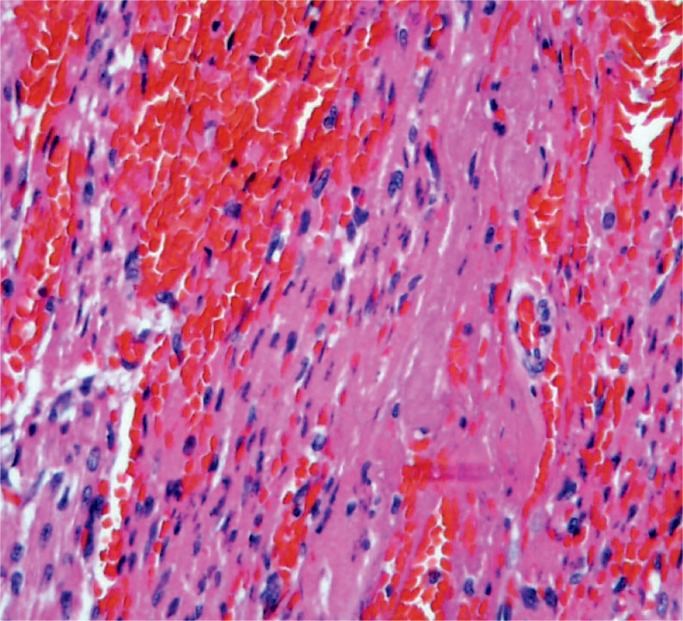

Image 27:

Myocardium with wavy change and contraction band necrosis, characteristic of acute ischemic injury, 4-24 hours (H&E, x100).

Image 28:

Calcifications of the papillary muscle (arrow) is a late feature of acute myocardial injury.

Image 29:

Hemorrhage and loss of nuclear detail with early infiltrate of neutrophils, 24 hours or more after ischemia (H&E, x400).

Image 30:

The tip of papillary muscle with recent and remote injury. Note calcifications. This is the area of the neonatal heart most sensitive to hypoxia (H&E, x100).

Image 31:

Diffuse subendocardial calcification after global hypoxic injury. A process which takes several days to occur (H&E, x100).

Image 32:

Higher power magnification of individually calcified my-ofibers in the heart (H&E, x200).

Image 33:

Hypoxic ischemic effects on the diaphragm with necrosis and calcifications (arrow) (H&E, x400).

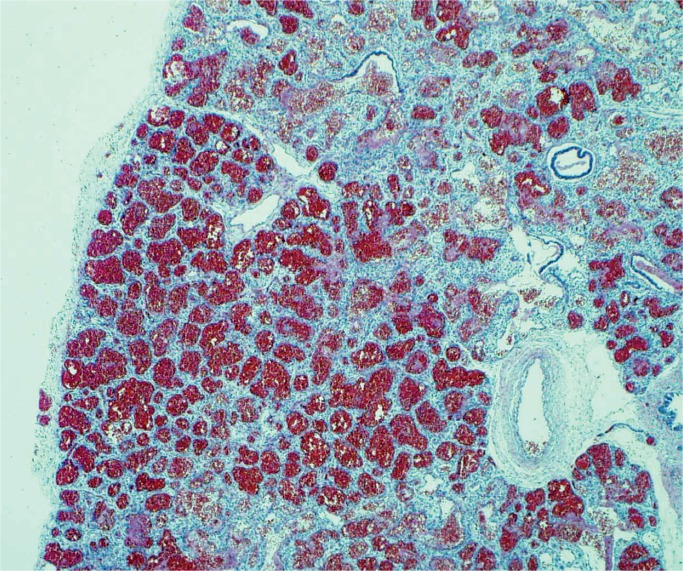

Liver and Platelets

Liver injury is due to hypoperfusion rather than hypoxia with elevated serum transaminase levels (17). Secondary coagulation dysfunction can also occur associated with consumptive coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (18 –21). The pattern of injury is centrilobular necrosis and frequently there is significant accumulation of lipid in hepatocytes (Images 34 and 35).

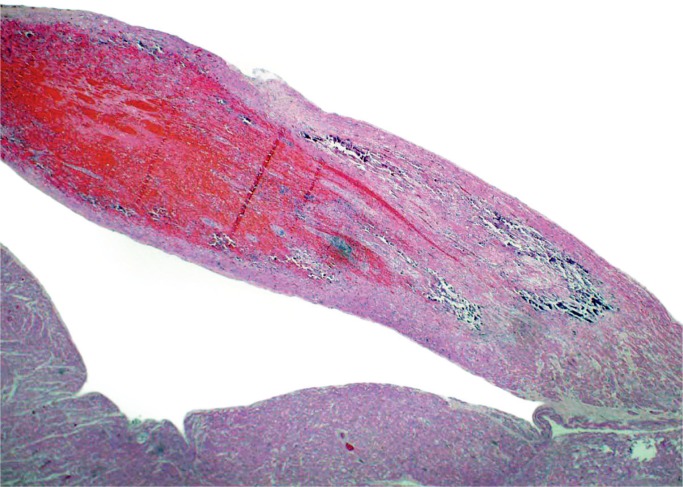

Image 34:

Hypoxic liver injury results in necrosis of the hepatocytes around the central veins, centrilobular necrosis (arrows). There is also an increase in extramedullary hematopoiesis which suggests some degree of chronic hypoxia as well (H&E, x200).

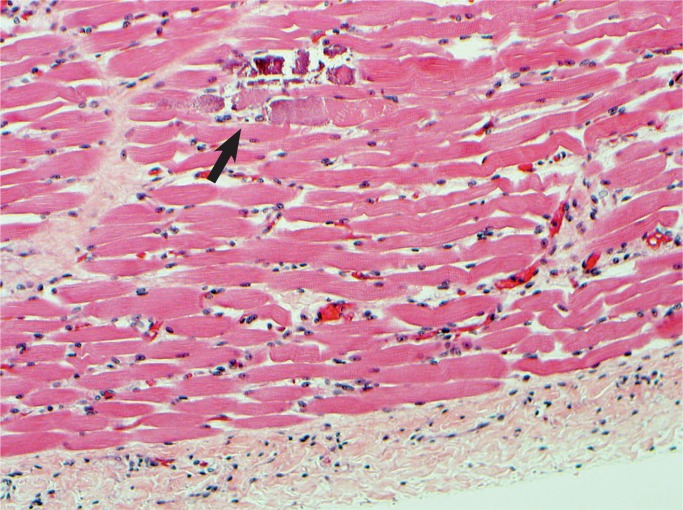

Image 35:

Small lipid droplets in the hepatocytes (arrows) (microvesicular steatosis) is a response to acute hypoxia (H&E, x400).

In addition to the coagulopathy, hypoxia has a direct effect on platelet formation resulting in thrombocytopenia (8). Platelets will increase in the immediate post hypoxic period as they are an acute phase reactant. A similar increase in lymphocytes will also occur. Megakaryocytes do not appear to be injured by hypoxia, but the cells in the bone marrow surrounding them are affected and decrease the release of platelet promoting factors (21, 22).

Spleen

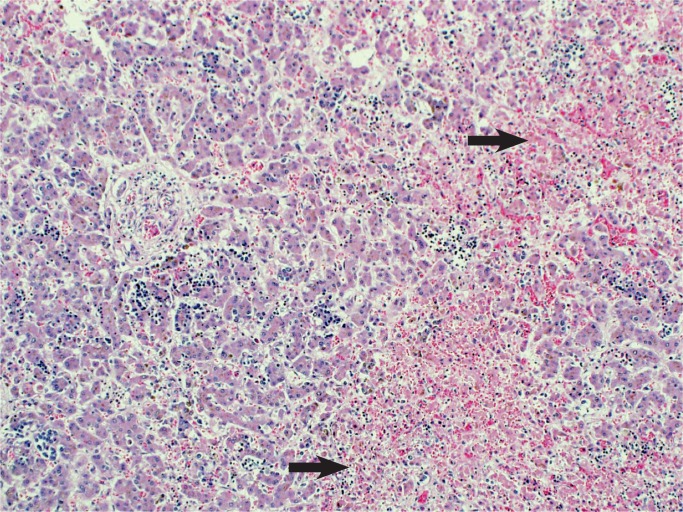

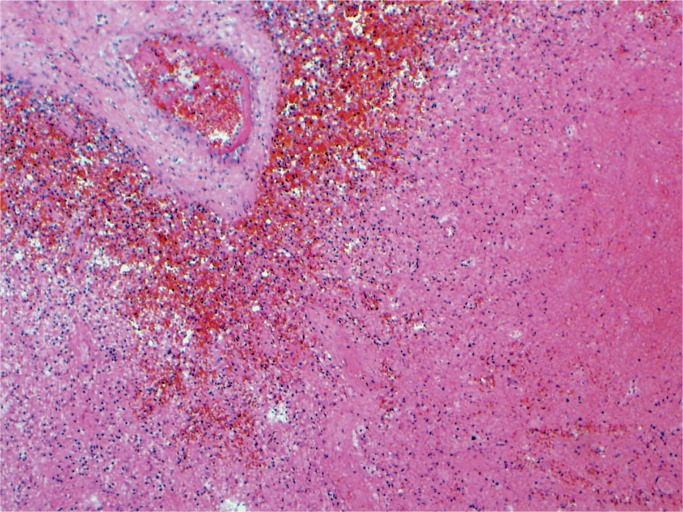

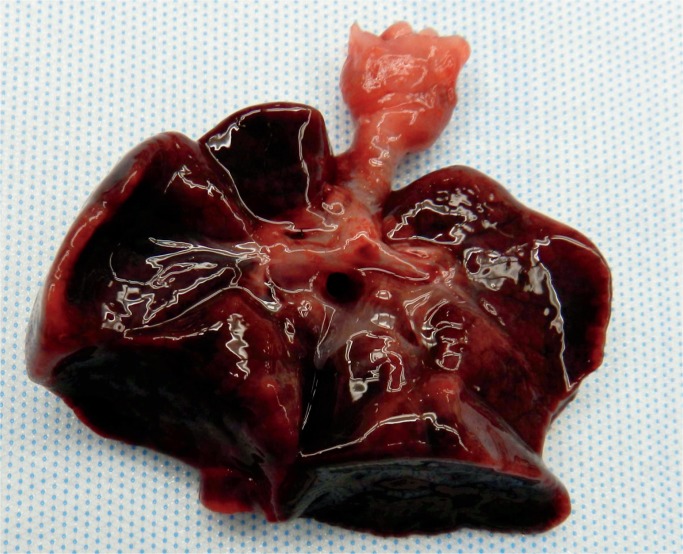

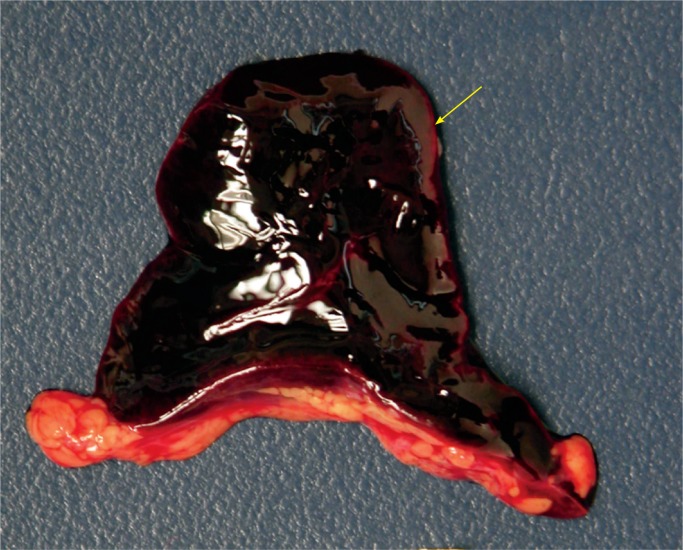

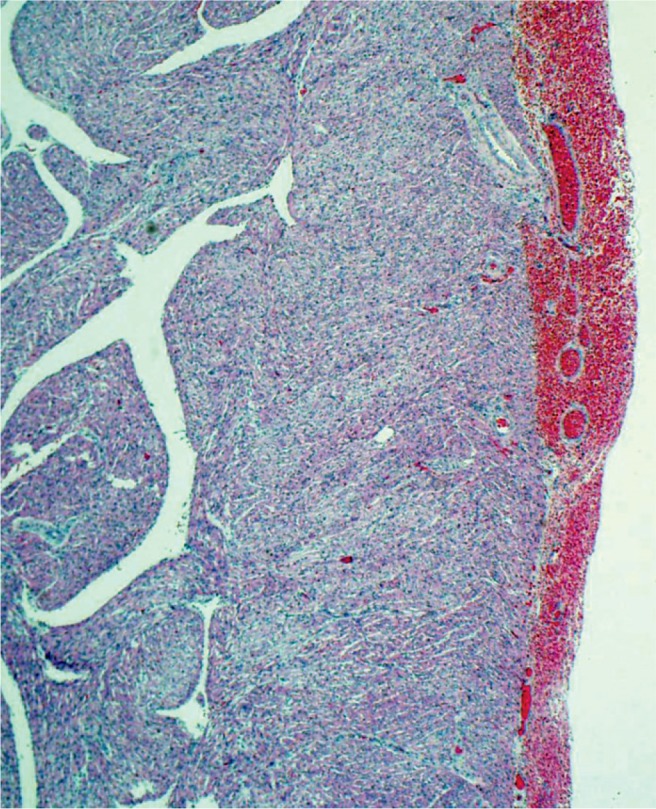

Hypoxia and ischemia can affect the spleen during birth asphyxia. The spleen can infarct and during the neonatal period the splenic function may be decreased with a reduction in the natural killer cells and T cell expression (Image 36).

Image 36:

Splenic infarct secondary to hypoxia and ischemia (H&E, x200).

Kidney, Electrolytes, Pancreas, and Glucose

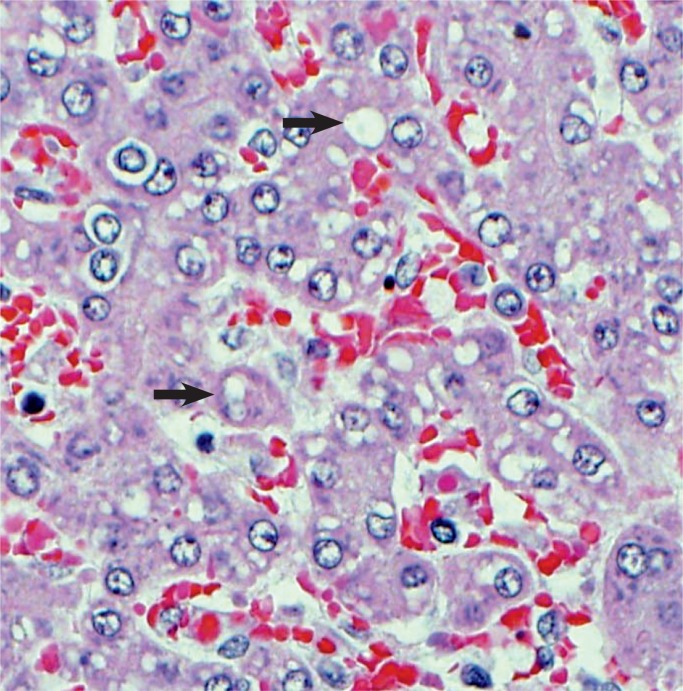

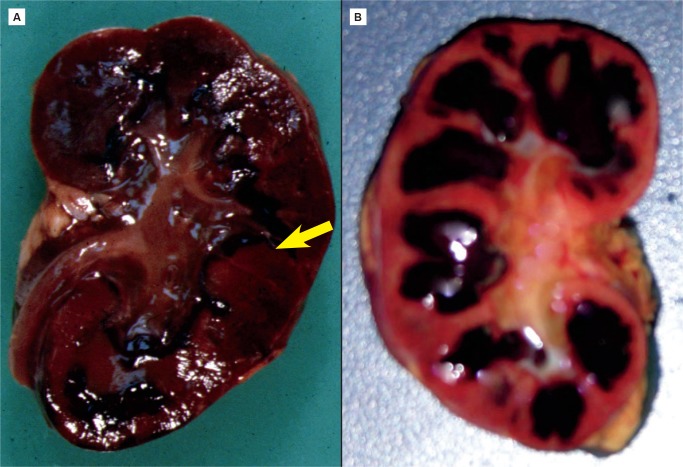

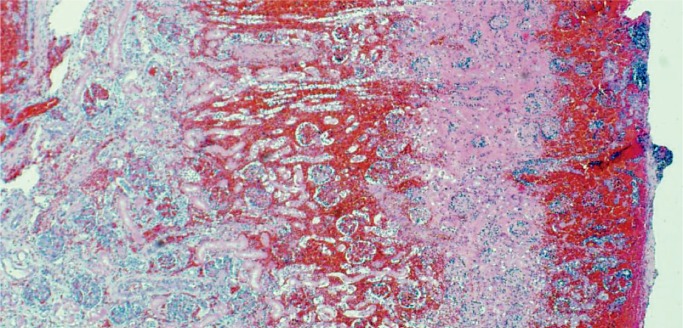

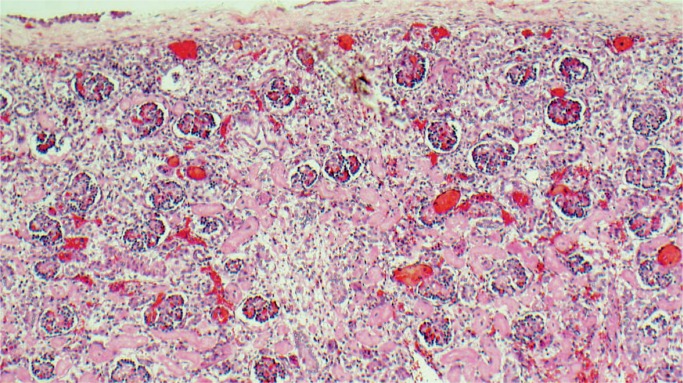

All nephrons are formed by 34 weeks gestational age and the glomerular filtration rate increases six-fold from birth until one year of age (23). The renal parenchymal cells have a limited capacity for anaerobic respiration and a high susceptibility to reperfusion injury (24). With birth asphyxia, the kidneys can be damaged resulting in an increased creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, a decreased urine output, and hematuria. The kidneys may develop acute tubular necrosis and electrolyte imbalance including hyperkalemia (due to the inability to make urine and clear potassium from the blood), hyponatremia (due to decreased resorption in proximal tubules), and hypocalcemia (3, 25, 26). Renal cortical necrosis is rare, but is associated with severe hypotension, such as occurs with rupture of vasa previa or large fetal-maternal bleed (Images 37 -41).

Image 37:

Renal cortical necrosis (arrow) is the result of severe hypovolemic shock as occurs after fetal hemorrhage. This may be secondary to ruptured vasa previa or fetal-maternal transfusion.

Image 38:

Renal cortical necrosis can be difficult to distinguish from autolysis. Hemorrhage is almost always present with cortical necrosis (H&E, x100).

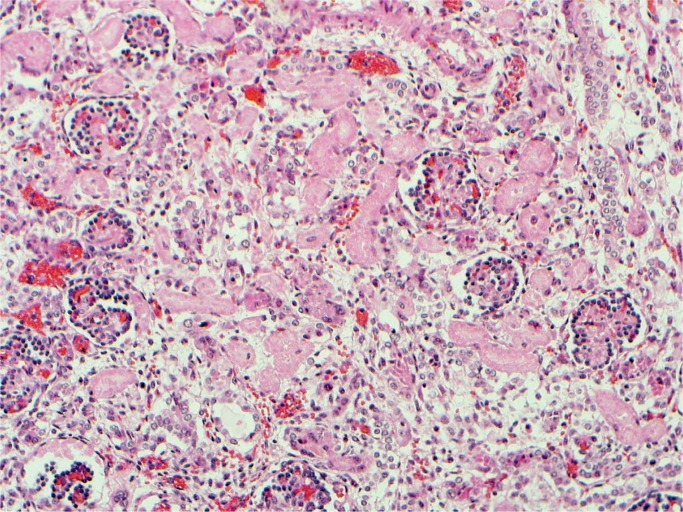

Image 39:

Renal acute tubular necrosis (H&E, x200).

Image 40:

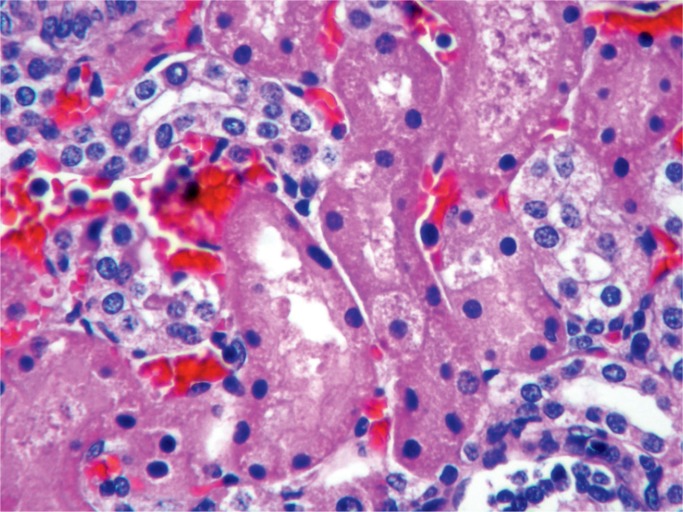

Acute tubular necrosis in the early stages shows only hyperchromatic smudged nuclei and may be difficult to distinguish from autolysis (H&E, x200).

Image 41:

Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) (H&E, x400). There may be vacuolization of the cytoplasm; ATN is a reversible injury after acute hypoxia.

Stressed infants rapidly deplete glucose and can develop severe hypoglycemia. When the islets of the pancreas are injured, there is often an initial hypoglycemic phase followed by a hyperglycemic phase. This type of injury is generally associated with hypovolemic shock. The acinar tissue is rarely injured. In the presence of hypoglycemia, hypoxic injury to the brain is significantly increased.

Lungs

Most neonates with birth asphyxia have significant injury to the lungs. Hypoxia and ischemia cause acidosis and damage to both the capillary endothelium and the pneumocytes resulting in hemorrhage (Images 42 and 43). Numerous inhaled squamous cells will be in the airways, many arranged in stacks and distend the airways. Other pathologic findings are pulmonary edema, pulmonary hemorrhage (further complicated by coagulopathy), necrosis of pneumocytes, and resultant hyaline membrane formation. Inhaled meconium can be seen in the distal airways resulting in a chemical pneumonitis (Images 3 -6). Birth asphyxia can also damage the brainstem respiratory drive centers.

Image 42:

Diffuse, severe pulmonary hemorrhage is a common feature associated with hypoxia and acidosis in the preterm infant.

Image 43:

Massive acute intraalveolar hemorrhage is a complication of hypoxia, and then worsens the hypoxia as it results in poor oxygenation of the newborn (H&E, x100).

The diaphragm and other skeletal muscles are also highly susceptible to hypoxic injury due to their high energy demand. Hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis reduce the diaphragm’s function and resistance to fatigue (Image 33) (3). Other skeletal muscles are affected as this is seen in cerebral palsy with hypotonia (27).

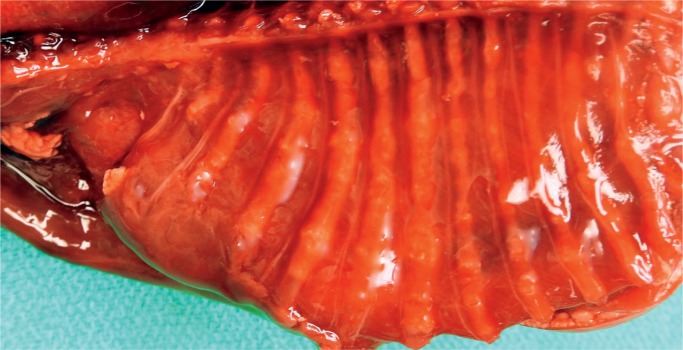

Stomach and Intestines

The gastrointestinal system has multiple watershed regions that are prone to hypoxic injury from birth asphyxia. Consequences include necrosis of the bowel mucosa or entire wall with perforation, gastrointestinal bleed, retained gastric contents due to poor and delayed emptying times, and disruption of neuronal control of peristalsis. Especially vulnerable to hypoxia and ischemia are the terminal ileum and proximal ascending colon (Image 44). Necrotizing enterocolitis has been reported but is a rare complication of birth asphyxia (8). Necrotizing enterocolitis is more associated with prematurity but may occur at term associated with cyanotic congenital heart anomalies.

Image 44:

Ischemia of the small bowel with full-thickness loss of nuclear chromatin basophilia. Note, the mucosa is more sensitive to hypoxia than the muscularis propria (H&E, x200).

Mechanical Birth Trauma

During birth, the infant’s head and trunk are exposed to contractions of uterine muscles and to intraabdominal pressure. The process is a blend of compressions, contractions, torques, and tractions (28). Skull deformation occurs, compressive and traction forces are applied to the head and extremities, instruments are used, and cephalopelvic disproportion and dystocias may be encountered, all placing the fetus at risk for trauma. Although mechanical birth trauma may occur without any identifiable risk factors, it is more common in the context of predisposing fetomaternal risk factors (see Table 6). The theory that brain compression alone results in brain injury has not been substantiated at this time and remains controversial. The following discussion will be divided into injuries of the skin and soft tissue, head, neck and spinal cord, peripheral nerves, extracranial skeleton, and viscera.

Table 6:

Birth Trauma Risk Factors.

| Maternal diabetes |

| Maternal obesity |

| Cephalopelvic disproportion |

| Short maternal stature |

| Extreme maternal age (<16 and >35 years) |

| Primagravida |

| Macrosomia, > 4000 g |

| Prematurity or low birth weight, < 1500 g or < 28 weeks |

| Precipitous delivery |

| Prolonged labor |

| Oxytocin use |

| Epidural anesthesia |

| Instrumentation (vacuum, forceps) |

| Malpresentation |

| Malposition |

| Oligohydramnios |

| Dystocia |

| Multiple gestations |

| Fetal tumors |

| Congenital abnormalities |

Skin and Soft Tissue

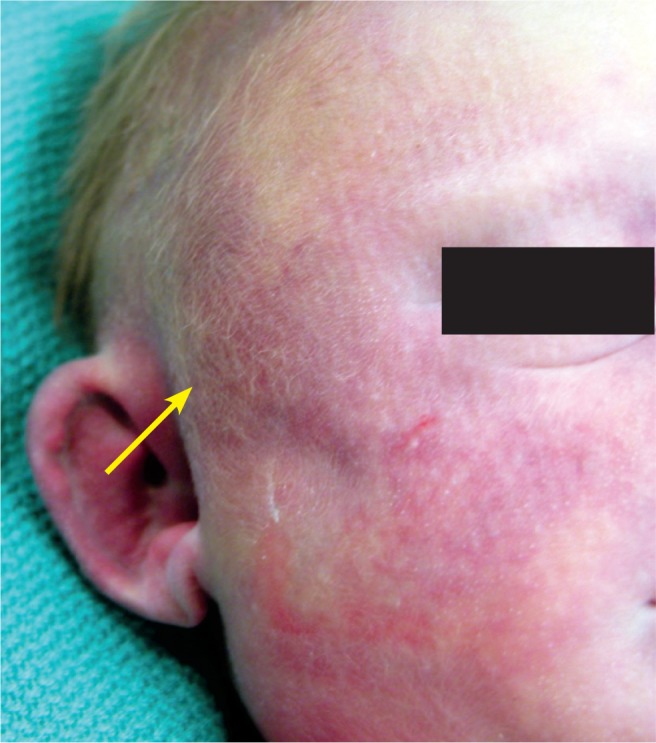

Cutaneous Injury

Bruising is the most common birth trauma and is seen in nearly all preterm deliveries (Images 45 -49). The skin is nearly gelatinous and bruises without excessive forces. This bruising can contribute to hyperbilirubinemia in the neonatal period (Image 48). Hemosiderin will begin to form within 48 hours of the bleed and become evident on routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) histology stains within 72 hours. Scalp injury due to scalp electrode placement and incisions during cesarean delivery may also occur.

Image 45:

Swelling and subtle discoloration in the temporal area of a baby found to have a subgaleal hemorrhage.

Image 46:

Fat necrosis is an uncommon complication of trauma during delivery. The epidermis and dermis is unremarkable, but there is necrosis of the subcutaneous fat with multinucleated foreign body reaction (arrow) (H&E, x40).

Image 47:

High magnification of Image 46 with multinucleated giant cells and saponification of adipose tissue (H&E, x400).

Image 48:

The skin is gelatinous in the extremely premature infant. Bruising can occur even during a nontraumatic delivery. The pattern of bruising of the lower legs may be secondary to a double footling breech presentation with the feet handing out through the cervix. This bruising can contribute to hyperbilirubinemia of the newborn.

Image 49:

Large, discolored, symmetric lesion over the buttocks. Bruising could be responsible, but most of the time it is a Mongolian spot (congenital dermal melanocytosis), which appears as a flat, irregular, pigmented lesion over the lower back or buttocks. They may be present at birth or appear during the first few weeks of life, most resolve by three to five years of age.

Subcutaneous Fat Necrosis

Placement of hands during delivery will often result in a pattern of fingers on the baby. These are usually multiple, sharply demarcated, firm, subcutaneous plaques or nodules on extremities, face, trunk, or buttocks. The overlying skin is usually normal in appearance but may have a red-purple discoloration. Fat necrosis can be a complication of cooling therapy for HIE (Images 46-47).

Head

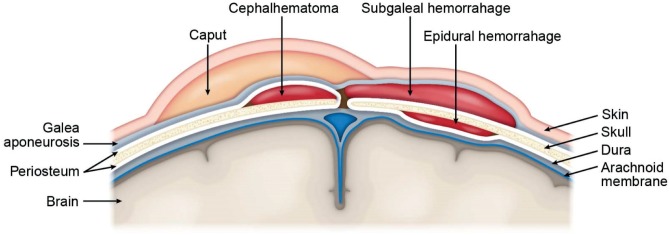

Injuries to the head include soft tissue injuries, skull injuries, and brain injuries. The normal anatomy of the scalp and brain moving from the outside to the inside is: skin, galea aponeurotica, connective tissue and emissary veins, periosteum, outer skull table, (diploe is not present in the neonate, but there is a thin layer of trabecular bone between the flat membranous inner and outer tables) inner skull table, inner periosteum/ dura mater, arachnoid, subarachnoid space with cerebral arteries and veins, pia, and brain (cerebrum and cerebellum). Hemorrhage can occur within and between the different layers of the scalp, intracranially between meninges layers, and within the parenchyma (Figure 1).

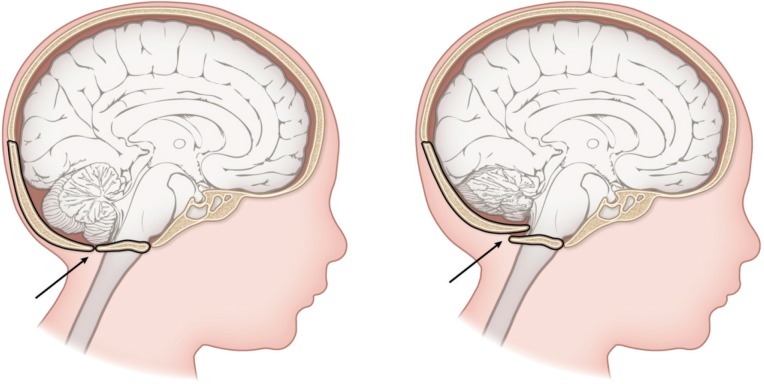

Figure 1:

Layers of the scalp, skull, and brain. Hemorrhage can occur within and between the different layers of the scalp, intracranially between meninges layers, and within the parenchyma. Created by Karen S. Prince, medical illustrator.

The neonatal skull is composed of 22 bones: partially ossified bony and cartilaginous components separated by sutures, synchondroses, and fontanels (28, 29). During vaginal birth, the head undergoes molding depending on the cephalopelvic dimensions, fetal position, and presentation. The mechanical forces involved can result in deformation, edema, and less commonly hemorrhage.

Cephalohematoma

The most frequent cranial birth trauma is a cephalohematoma. This collection of blood is from a slow venous bleed between the outer periosteum and the skull, or subperiosteum (Images 50 -52). The bleeding is caused by disruption of veins that run between the diploic space and the periosteum. Cephalohematomas do not cross suture lines (as opposed to caput succedaneum) and are unilateral. This is because diploic veins of each cranial bone are separate in infants. The most common location for a cephalohematoma is the posterior parietal skull. The overlying scalp is not discolored. Cephalohematomas are associated with instrumentation and prolonged head engagement and up to 25% have an underlying linear, non-depressed skull fracture. Cephalohematomas can enlarge over the first three postnatal days, calcify, become infected (E. coli is common), rarely cause meningitis, and can rarely lead to hyperbilirubinemia and jaundice. Most usually resolve without treatment within two to three weeks (30).

Image 50:

Cephalohematoma – axial computed tomography image in a one-month-old male shows a resolving cephalohematoma with a partially calcified rim (arrows). Image courtesy of Ellen M. Chung MD, Uniformed Services University.

Image 51:

This is a large cephalohematoma with relatively sharp borders (arrow) due to it not crossing suture lines.

Image 52:

Cephalohematoma over the right parietal bone. The hematoma is sharply limited by the suture line of the frontal bone and sagittal suture (arrow). Resolution of such a large hematoma takes many months and usually calcifies.

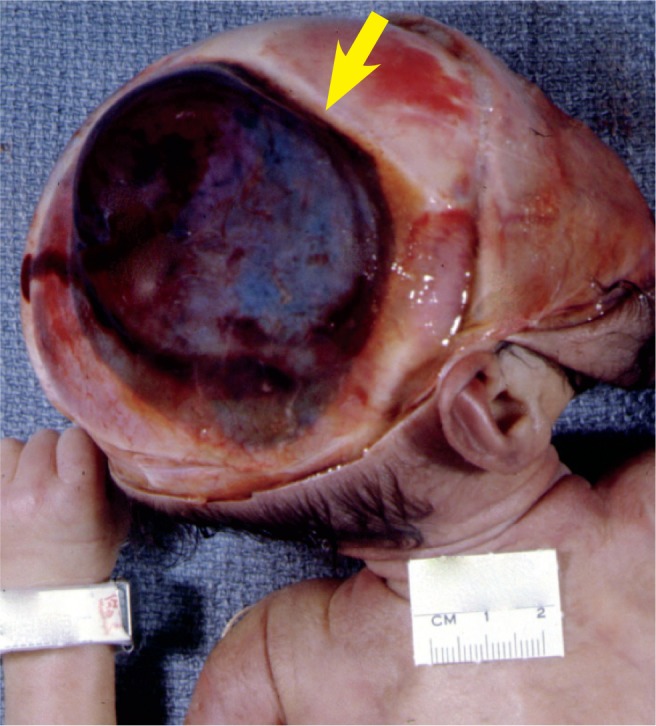

Caput Succedaneum

A caput succedaneum, or “second head”, is an accumulation of serosanguinous fluid or serum beneath the galea and outside of the outer periosteum (Images 53 and 54). The periosteum is not involved. Prolonged labor and pressure on the skull are risk factors. The fluid accumulation is opposite the side of the pressure. Overlying petechiae and ecchymoses are often present, unlike a cephalohematoma. Since the fluid is above the outer periosteum due to rupture of fragile vessels, the fluid accumulation crosses the suture lines. Although often frightening, it is rarely clinically significant and usually resolves within 24-48 hours and rarely last up to four to six days (30). The terms chignon or iatrogenic caput succedaneum are sometimes used to refer to a caput succedaneum caused by vacuum-assisted delivery. Although usually not clinically significant, it may be associated with head/face abrasions and contusions secondary to the vacuum use.

Image 53:

Large baby with caput succedaneum which is a collection of edema fluid and/or blood in the subcutaneous tissues of the scalp. Note that this collection crosses over suture lines. The caput usually resolves within a few days after birth.

Image 54:

Large caput succedaneum which is composed of gelatinous edema and scant blood. The fluid crosses the sagittal suture. The sagittal bones overlap the frontal bones, a common finding after vaginal delivery.

Subgaleal Hemorrhage

Between the galea aponeurosis and the outer skull periosteum is a space that extends from the orbital ridges to the nape of the neck and laterally to the ears (Image 55). This space is so large that it can accommodate more than 40% to virtually 100% of a neonate’s entire blood volume (30). The origin of the blood is the emissary veins. Risk factors for a subgaleal hemorrhage are vacuum (90% of cases) and, less often, forceps use (28). Subgaleal hemorrhage can be associated with complicated skull fractures, intracranial hemorrhage, and cerebral compression. The hemorrhage may continue to expand over three days and can result in hypovolemic shock and coagulopathy. The mortality rate is up to 25%. There may not be bruising on the scalp, and this may go undetected. The initial hemoglobin and hematocrit levels will be near normal, but the baby is severely hypovolemic.

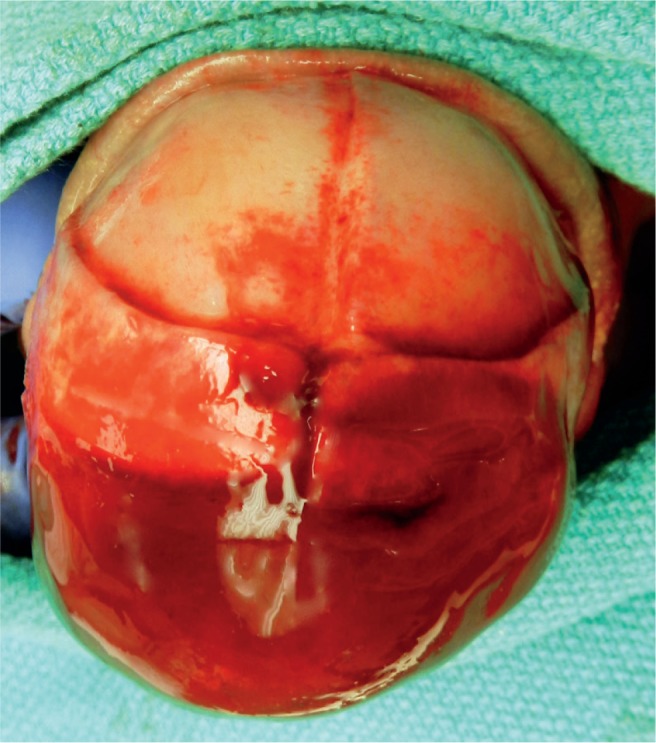

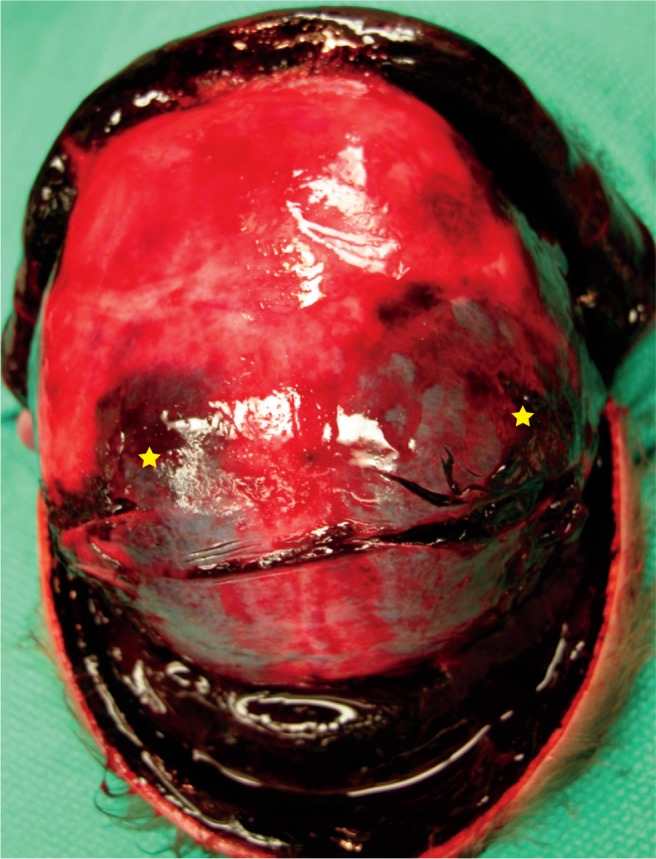

Image 55:

Large subgaleal hemorrhage spreading over the entire scalp. This potential space can accommodate a significant blood volume and result in hypovolemic shock of the neonate. Note, there are also bilateral parietal cephalohematomas (star).

Intracranial Hemorrhage

Neonatal intracranial hemorrhages include epidural, subdural, subarachnoid, cerebral parenchymal, intraventricular, and cerebellar intraparenchymal hemorrhages (intraventricular hemorrhages are associated with birth asphyxia and prematurity. The source can be the basal ganglia, midbrain, subependymal germinal matrix network, ependyma, or choroid plexus, depending on the gestational age of the fetus). Traumatic intracranial hemorrhages are associated with prolonged or precipitous delivery, vaginal breech delivery, instrumentation, and primiparity. Tearing of the falx or tentorium is secondary to molding of the skull. Subdural and intraparenchymal cerebral hemorrhages are more often seen in term neonates; subarachnoid, intraventricular, and cerebellar parenchymal hemorrhages are more often seen in preterm neonates. Of note, the aforementioned thrombocytopenia as seen with birth asphyxia has been reported as the most common condition associated with intracranial hemorrhages (31). The mortality rate of all intracranial hemorrhages is higher in neonates who also experienced birth asphyxia.

Epidural Hemorrhage

An epidural hemorrhage is secondary to separation of the dura from the inner periosteum of the skull. The origin of the blood is a branch of the middle meningeal artery or venous sinus (28). Accordingly, epidural hemorrhages are rare at birth because the middle meningeal artery is not yet encased within the skull bone and is, therefore, movable. Most cases are a difficult delivery with instrumentation which causes the dura-skull separation. Unlike adults, a skull fracture is not always present. A case of epidural hemorrhage with parietal fractures has been reported secondary to a fall during a precipitous delivery from a standing position (32). Epidural hemorrhages are associated with scalp swelling and bulging of the anterior fontanelle.

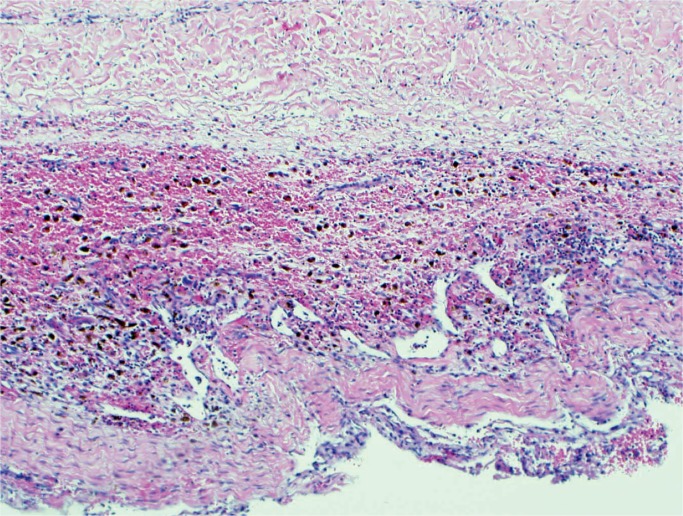

Subdural Hemorrhage

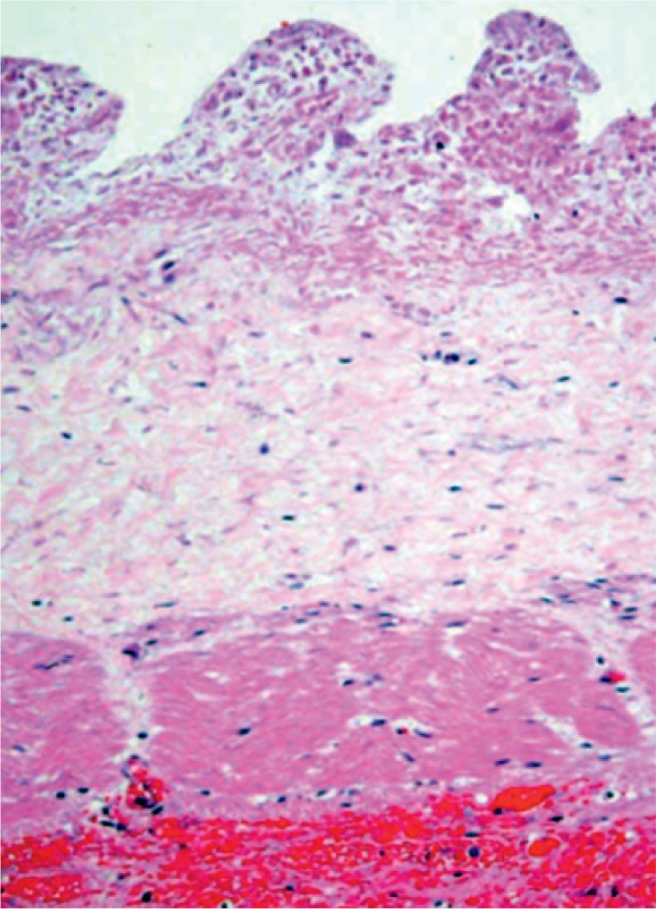

A subdural hemorrhage is the most common form of intracranial hemorrhage in the neonate (Images 56 -58) (33). Risk factors are vaginal delivery with excessive molding, malpresentation/position especially breach, prolonged labor, and instrumentation. These hemorrhages are usually in the interhemispheric fissure over the cerebrum, parieto-occipital convexity, or the suboccipital area close to the cerebellar tentorium (28). It is not uncommon to also have an occipital cerebral contusion (28). The mechanism of injury is molding of the fetal head leading to tearing of the subdural veins and dural venous sinuses. The neonate will have a full fontanelle, increased head circumference, and possibly brainstem compression. Subdural hemorrhages usually resolve within four to six weeks (34).

Image 56:

Subacute, small subdural hematoma occurs commonly with vaginal delivery.

Image 57:

Large subdural hematoma may be associated with traumatic delivery and/or coagulopathy of hypoxic-ischemic birth injury.

Image 58:

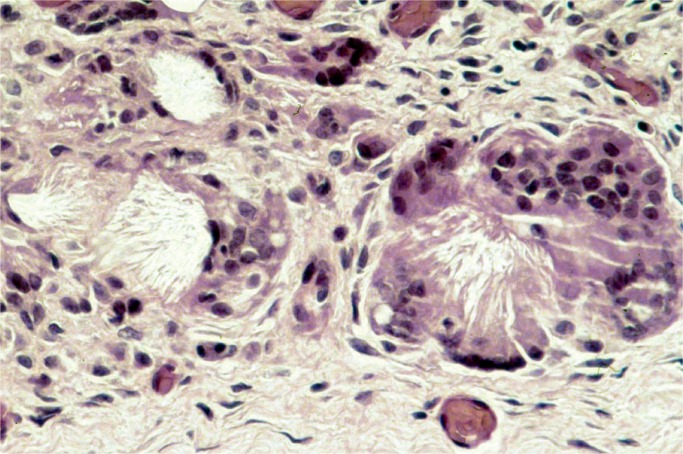

Remote subdural hematoma with fibroblast proliferation and abundant hemosiderin-laden macrophages forming a subdural “membrane” (H&E, x200).

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) results from tearing of the bridging veins within the subarachnoid space or small vessels in the meningeal plexus. Subarachnoid hemorrhages are associated with vaginal birth and vacuum delivery and are more common in preterm births. Often, neonates with subarachnoid hemorrhage also have retinal hemorrhages. Many SAH are clinically insignificant and some researchers believe they are even more common than subdural hemorrhage. Subarachnoid hemorrhages will usually resolve within two to four weeks (30).

Cerebral Injury

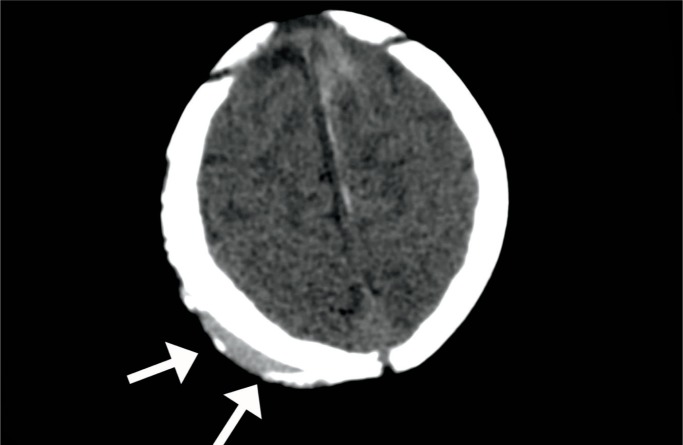

Cerebral trauma is seen with difficult vaginal deliveries and/or instrumentation. These injuries are most often white-matter hemorrhagic tears, commonly of the temporal cerebrum in the proximity to open sutures (Image 59). They are rarely associated with parietal fractures, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or epidural hemorrhage (35). Though uncommon, arterial strokes can result from trauma to a vessel or stretching of arteries during labor and delivery.

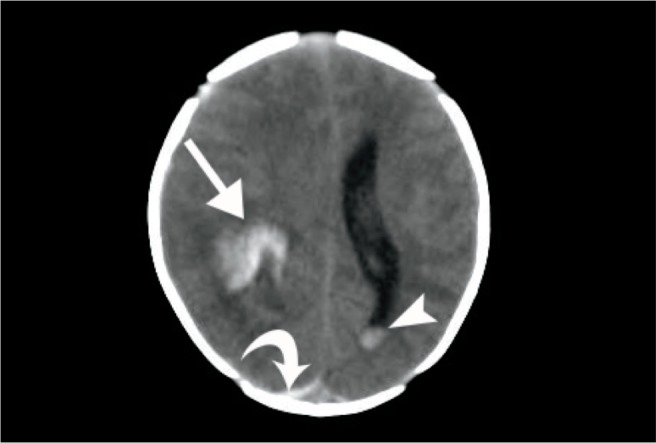

Image 59:

Intracranial hemorrhage – axial computed tomography image of a somnolent newborn demonstrates a hyperattenuating intraparenchymal hemorrhage (arrow), a curvilinear hyperattenuating occipital subdural hemorrhage (curved arrow), and a dependently layering intraventricular hemorrhage (arrowhead). Image courtesy of Ellen M. Chung MD, Uniformed Services University.

Cerebellar Injury

Trauma of the cerebellum is usually seen in preterm infants, breech deliveries, or as the result of occipital osteodiastasis (see below).

Skull Fractures

Skull fractures, rarely associated with birth, are most commonly seen with instrumentation. They can also occur after cesarean delivery, especially when the fetal head is wedged into the maternal pelvis and a vaginal hand is used to push the baby back up into the uterus. Three types of skull fractures are seen in birth trauma: linear fracture, ping-pong ball deformation, and occipital osteodiastasis.

Linear skull fractures are usually nondepressed and asymptomatic (Image 60). The most common bone involved is the parietal bone or the frontal bone and there may be an associated cephalohematoma. Linear skull fractures usually heal within two to six months. If the fracture is depressed, often with forceps delivery and usually of the parietal bone, there may be an associated intracranial hemorrhage (30).

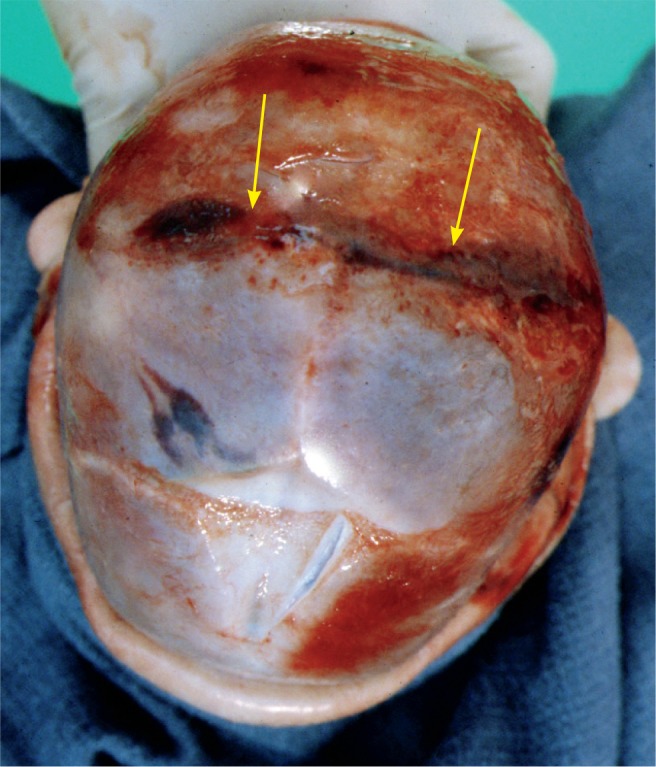

Image 60:

Skull fracture (arrows) of the posterior parietal bones that crosses over the superior sagittal suture. The anterior fontanelle is seen at the 6 o’clock position.

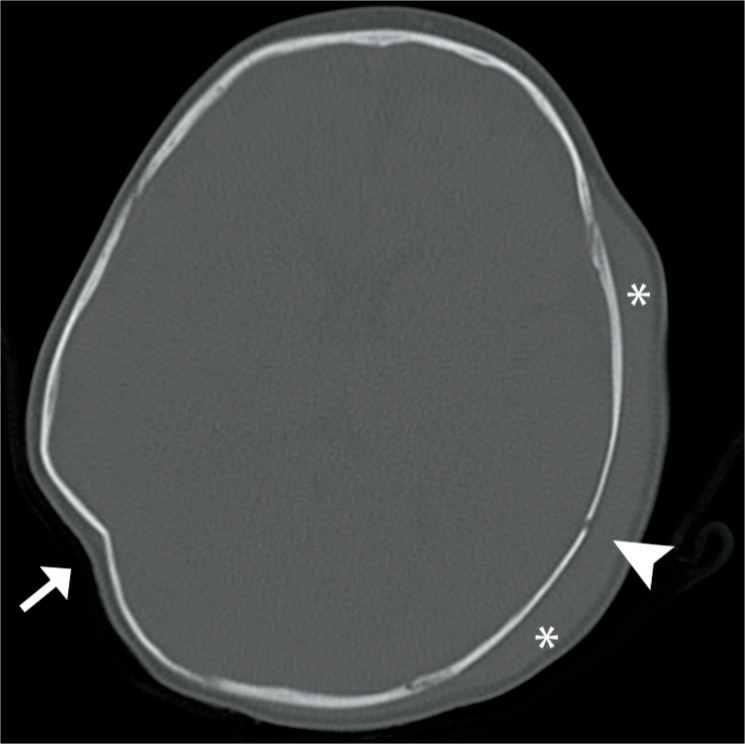

The ping-pong ball deformation usually involves the parietal bone and less often the frontal bone. The deformation is a depression, or concavity, of the outer skull table, and this is not an actual fracture because there’s no loss of bony continuity. The name refers to its appearance both grossly and radiographically as a dented or collapsed ping-pong ball (Image 61). The deformation most often occurs with forceps deliveries, including cesarean sections. There is usually no underlying pathology unless the depression is greater than 2 cm. Spontaneous elevation usually occurs within three months (30).

Image 61:

Ping pong skull – axial computed tomography image in bone window demonstrates a ping-pong deformity of the skull (arrow). Additionally, a hematoma (asterisks) and skull fracture (arrowhead) are noted. Image courtesy of Ellen M. Chung MD, Uniformed Services University.

Occipital osteodiastasis is an uncommon but severe fracture. The diastasis involves separation of the cartilaginous joint between the squamous and lateral portions of the occipital bone. The separation is due to excessive pressure over the suboccipital region. This occurs especially in cases of hyperextension, pressure on the maternal pubic synthesis, forceps use, and breech malposition. The anterior squamous portion of the occipital bone is pushed anteriorly and upward, tearing the bridging veins, and resulting in subdural hemorrhage, cerebellar laceration or contusion, or cerebellar-medullary compression (Figure 2). Occipital osteodiastases is diagnosed by lateral radiography as well as a careful posterior neck dissection at autopsy. The mortality rate is very high.

Figure 2:

Occipital osteodiastasis involves the separation of the cartilaginous joint between the squamous and the two lateral portions of the occipital bone. Note, the anterior squamous portion of the occipital bone (arrow) is pushed anteriorly and upward, tearing the bridging veins, resulting in subdural hemorrhage, cerebellar laceration or contusion, and/or cerebellar-medullary compression. Created by Karen S. Prince, Medical Illustrator.

Face and Eyes

Abrasions, contusions, and lacerations can occur secondary to instrumentation. The nose can also be injured with dislocation of the cartilage and deviation of the septum. Mandibular fracture has also been reported. Significant bruising can occur with face or chin presentation. The facial nerve, cranial nerve VII, innervates the facial musculature and is most often damaged during vaginal deliveries requiring forceps or when the face is compressed against the maternal sacrum. Facial nerve injury is usually unilateral and is often associated with an ipsilateral clavicular fracture. Facial nerve palsy (90%) will improve within days to two months. The eyes can be traumatized during delivery with laceration of the cornea, especially when using forceps. Scleral and subconjunctival hemorrhages (unilateral or bilateral) are associated with increased intrathoracic pressure during vaginal delivery and are often associated with an ipsilateral clavicular fracture. These hemorrhages usually resolve within seven to ten days (30).

Retina

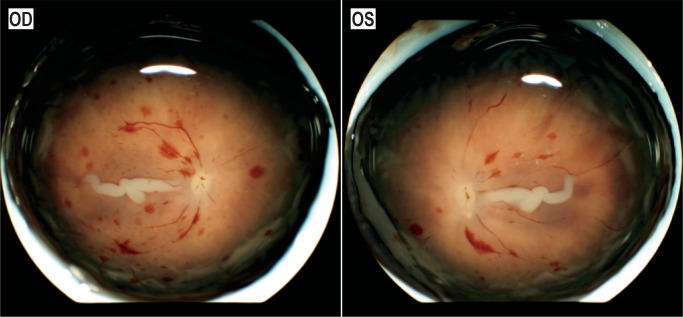

Retinal hemorrhages are of interest due to their high association with inflicted abusive head trauma. However, it is estimated that retinal hemorrhages occur in 20-40% of births (Image 62) (36 –38). They are usually located in the posterior retina and are associated with instrumentation, vacuum more often than forceps (38). They are also more common in vaginal deliveries as opposed to cesarean sections. Other risk factors are prolonged second stage of labor and nuchal cord. Some studies report an association between retinal hemorrhages and subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to birth trauma. Retinal hemorrhages usually resolve within a month of delivery (30).

Image 62:

Retinas from a one-day-old who sustained severe hypoxic ischemic brain injury during a prolonged delivery. Images courtesy of Patrick E. Lantz MD, Wake Forest Baptist Health.

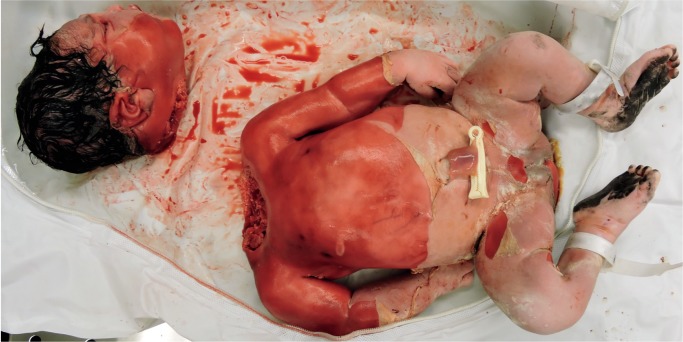

Neck, Spinal Cord, and Peripheral Nerves

Damage to the spinal cord and peripheral nerves is associated with macrosomia, cephalopelvic disproportion, difficult delivery, forceps, breech presentation, shoulder dystocia, and obstruction (Images 63 -66) (39).

Image 63:

This large abdominal teratoma resulted in a difficult delivery and spinal cord and column transection at C5-7.

Image 64:

Bilateral tension pneumothoraces occurred during ventilation of hypoplastic lungs. The diaphragm is flattened, and the small lungs can be seen collapsed near the spine. The distended abdomen is a feature of prune belly syndrome and markedly dilated bladder, ureters, and hydronephrosis. This distension can result in a difficult delivery.

Image 65:

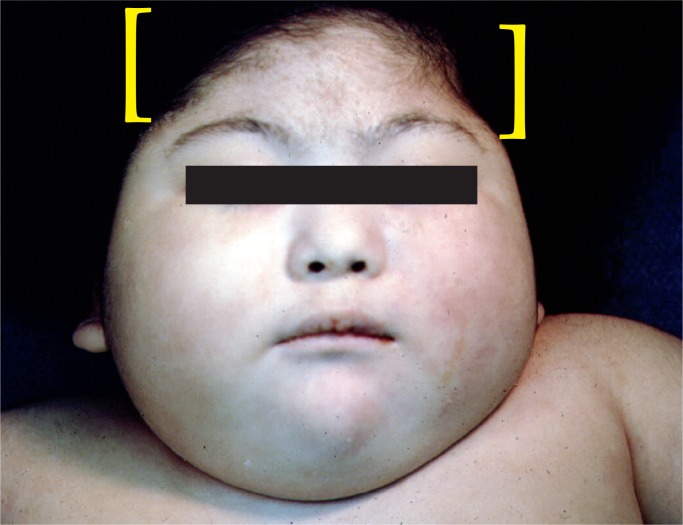

Macrosomic infant of a diabetic mother with only mild maceration was decapitated during vaginal delivery . Dystocia was encountered, and excessive traction was used in an attempt to delivery the baby.

Image 66:

Tearing of the intertriginous tissue of the axillae or groin may occur with excessive traction with delivery. In this case, the fetus was macerated, which contributed to the injury.

The spinal cord is usually injured due to spinal column flexion, longitudinal stretching, and traction during delivery with the neck hyperextended and pulled laterally as the shoulders are delivered. The most common spinal cord injury is of the upper cord at C4, with cephalic presentation and often with forceps use (40). The neonate can present with apnea. Lower cord injuries are seen at level C5-T3 in breech deliveries, especially during lateral traction. Lower cord injuries often present with areflexia and hypotonia. Spinal cord injuries carry a very high mortality rate of 70-90% (41). Vertebral fractures can occur and are most common at C5-7 (Image 65).

Phrenic Nerve

The phrenic nerve arises from C3-5. Damages in this area is associated with breech presentation, shoulder dystocia, and lateral hyperextension of the neck. Phrenic nerve damage is usually unilateral. Neonatal presentation is dyspnea, possible cyanosis, and asymmetrical diaphragmatic movements. Phrenic nerve palsy can be associated with brachial plexus palsy due to the involvement of C5.

Brachial Plexus

The brachial plexus consists of nerve roots C5-T1 (see Table 7). Injury to the brachial plexus is associated with shoulder dystocia, breech delivery, lateral neck traction, and macrosomia (42). There are three common types of brachial plexus palsies: Erb palsy, Klumpke palsy, and complete brachial plexus palsy. When T1 is involved with injury to the sympathetic trunk, Horner syndrome results (ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis).

Table 7:

Brachial Plexus Palsies.

| Palsy | Frequency | Nerves | Arm, Hand | Presentation | Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erb | Most common | C5-6, maybe 7 | Arm affected. Wrist/hand ok unless C7 is involved | Arm adducted, internally rotated, prone; wrist flexed | Phrenic nerve palsy |

| Klumpke | Less common | C7-T1 | Shoulder and upper arm ok | Wrist and hand paralyzed in claw position | Horner syndrome (T1 sympathetic fibers) |

| Complete | Least common | C5-T1 | Total arm affected | Arm paralyzed, no sensation or reflexes | Atonic limb, phrenic nerve palsy, Horner sign (T1 sympathetic fibers) |

Most palsies are transient; however, approximately 20-25% of all brachial plexus palsies are permanent (42).

Torticollis

This disorder may be secondary to in utero mechanical factors or birth trauma. It is characterized by a 1-2 cm firm ovoid mass in the sternocleidomastoid muscle. There is muscle contracture and shortening which results in the head tilting toward the side of the lesion and the face rotated away from the lesion. In approximately 75% of cases, the right side of the neck is affected. Treatment is generally physical therapy.

Extracranial Skeletal Fractures

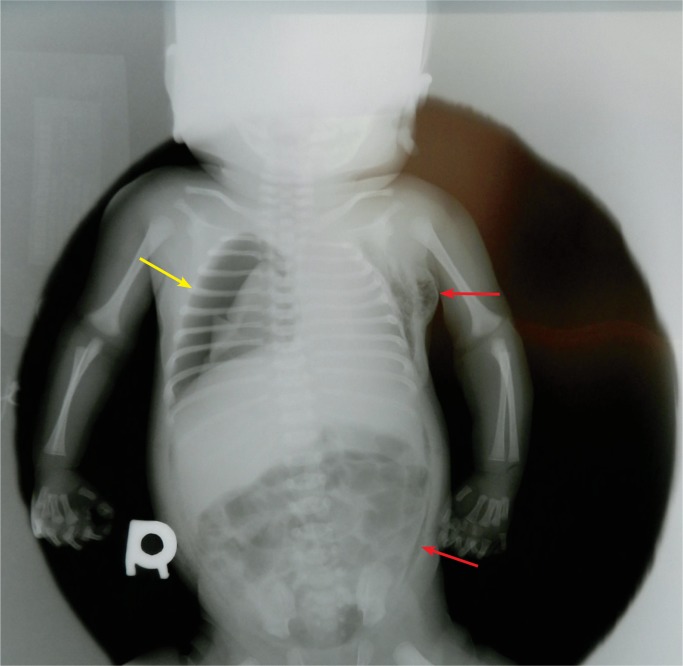

The most common extracranial skeletal fractures secondary to birth trauma are of the clavicle, humerus, and femur in descending order of incidence. The main risk factor is high birthweight. One study reported a higher incidence of long bone fractures in emergency cesarean sections (43). Neonatal fractures heal much faster than older infants or children and any fracture in an infant older than 11 days that does not have calcification suggests postnatal trauma (30). Neonatal fractures need to be differentiated from those of osteogenesis imperfecta or other severe forms of chondrodysplasia (Images 67 and 68).

Image 67:

Lethal osteogenesis imperfecta type II shows the characteristic features: poorly ossified skull, crumpled long bones, and beaded ribs. These are consistent with multiple in utero fractures. Less severe forms of chondrodysplasias may also be more prone to fractures during delivery.

Image 68:

Gross appearance of the beaded ribs seen radiographically in Image 67. Osteogenesis imperfecta type II.

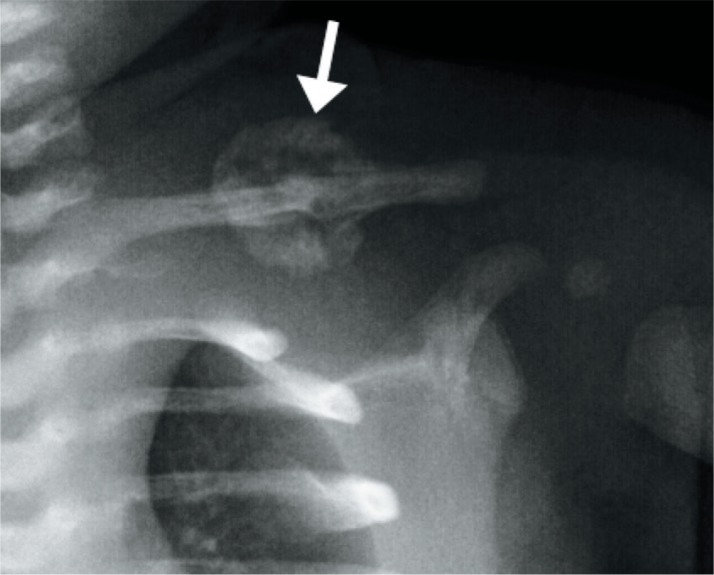

Clavicle

The most common bone to fracture at birth is the clavicle with an incidence of 0.2-4.4% of term births (Image 69) (30, 43, 44). The risk factors are macrosomia and shoulder dystocia. The fracture is usually midshaft or at the junction of the middle and distal third of the bone (30). Rarely, a pneumothorax can result from a fractured clavicle. Clavicular fractures show subperiosteal new bone formation within seven to ten days, and immature callus within two to four weeks (44).

Image 69:

Clavicl e fracture – anatomical position radiograph of the left clavicle in a 16-day-old large for gestational age boy shows a midshaft clavicle fracture with surrounding immature callus (arrow). Courtesy of Ellen M. Chung MD, Uniformed Services University.

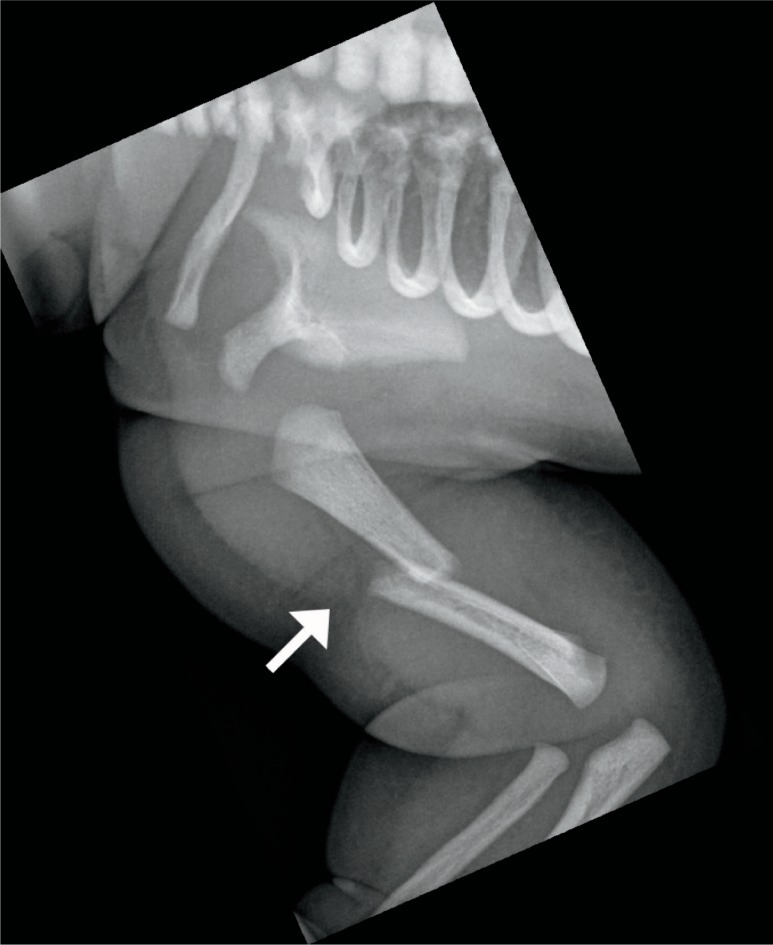

Humerus

Humerus fracture, the second most frequent long bone fracture, occurs most often in breech deliveries, dystocia, cephalopelvic disproportion, and high forceps delivery. The break is usually midshaft due to traction and torsion as well as hyperextension of the elbow (Images 70 and 71). Fracture can also be at the proximal and distal epiphyses. Radial nerve palsy can result. Subperiosteal new bone formation can be seen within ten days, and immature callus within two to three weeks (30).

Image 70:

Macrosomic term infant of a diabetic mother had shoulder dystocia at the time of vaginal delivery resulting in fracture of the humerus.

Image 71:

Humerus fracture: anatomicalposition radiograph of the right humerusin a newborn boy shows a completelydisplaced fracture of the humerus (arrow). Image courtesy of Ellen M. Chung MD, Uniformed Services University.

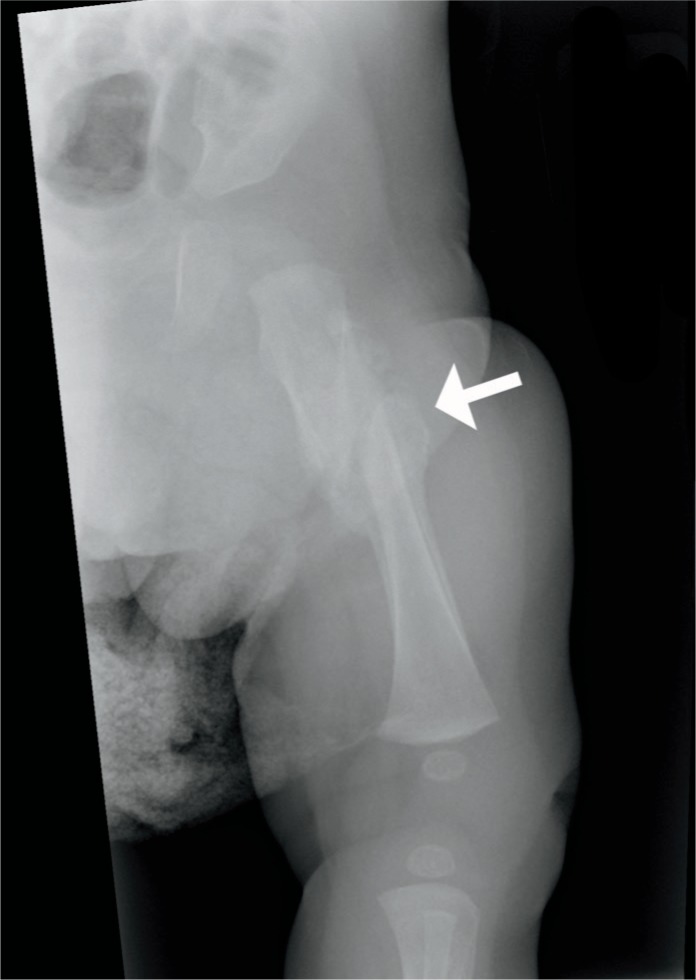

Femur

Although rare, the femur may be fractured during delivery, most commonly a spiral fracture of the shaft but also of the metaphysis and upper epiphysis. Risk factors are a breech presentation and difficult delivery.

External version maneuvers have also been known to cause femoral fractures. As mentioned, femoral and other long bone fractures have been reported in C-sections. Subperiosteal new bone formation can be seen within ten days, and immature callus within two to three weeks (Image 72) (30).

Image 72:

Anatomical position radiograph of the femur in a one-month-old infant demonstrates a completely displaced mid shaft fracture with mature bridging callus formation indicative of healing. Image courtesy of Ellen M. Chung MD, Uniformed Services University.

Ribs

Rib fractures secondary to birth trauma are rare, but when present, are usually during a difficult vaginal delivery with macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, and/or vacuum extraction. Rib fractures may also be seen in cases of osteopenia of prematurity. Fractures are of the mid aspect of the posterior rib and often associated with ipsilateral clavicular fractures (30).

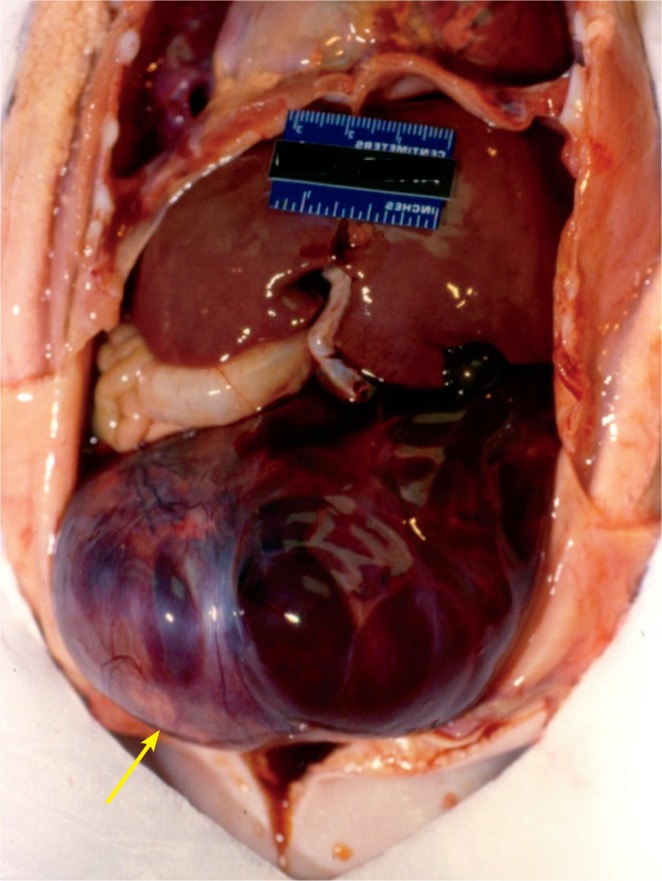

Viscera

The brain is the most common organ damaged secondary to birth trauma (see above). The next most common organs that can be physically injured are the liver, spleen, and adrenal glands. Overall, the infant will present with pallor, abdominal distention, and/or anemia secondary to hemorrhage.

Liver

The most common extracranial internal organ injured during delivery is the liver (30). Mechanical forces can result in a subcapsular hematoma (Images 73 -75). These hematomas can be large, up to 5 cm. Of note, delayed bleeding of a subcapsular hematoma can occur up to three days postpartum. The hepatic parenchyma can also be damaged during delivery leading to hemoperitoneum, scrotal/labial swelling, and ecchymosis. Subcapsular hematomas are more common in premature infants and in macrosomic infants or breech extraction. Hematomas may remain intact or rupture and rupture may occur during resuscitation efforts.

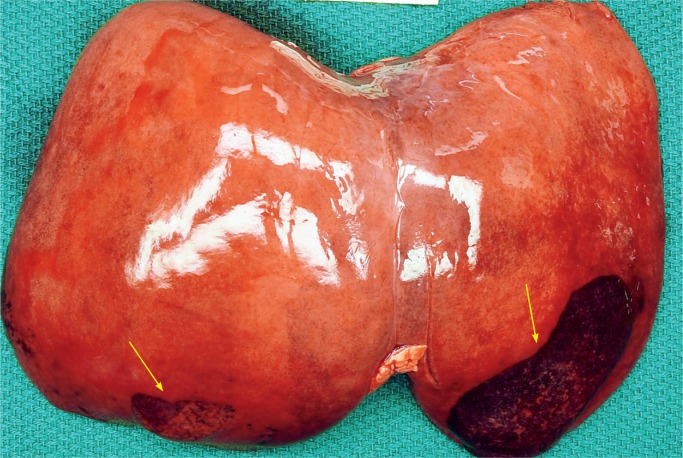

Image 73:

Traumatic hematoma at edges of liver L>R (arrows) due to the larger size of the fetal/neonatal liver.

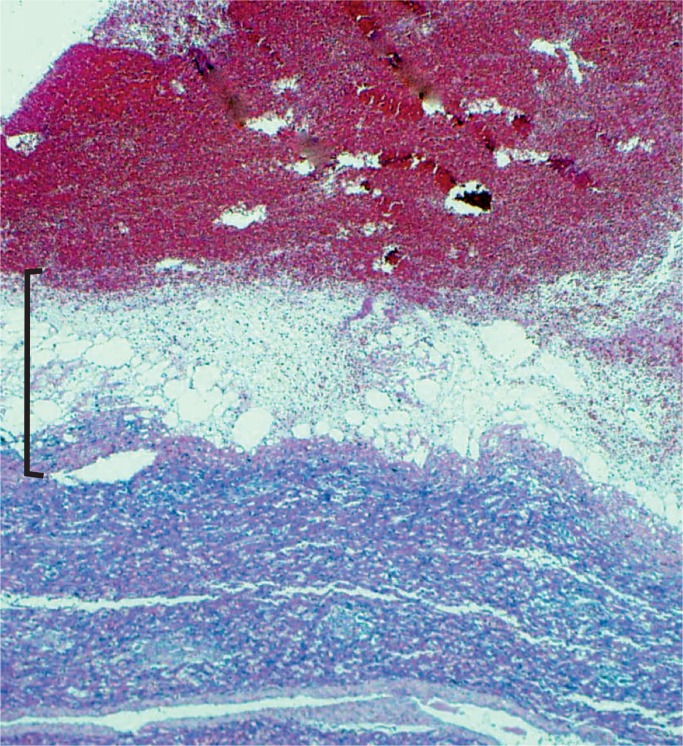

Image 74:

Large subcapsular liver hematoma that has caused frank necrosis of the underlying hepatocytes (bracket) (H&E, x100).

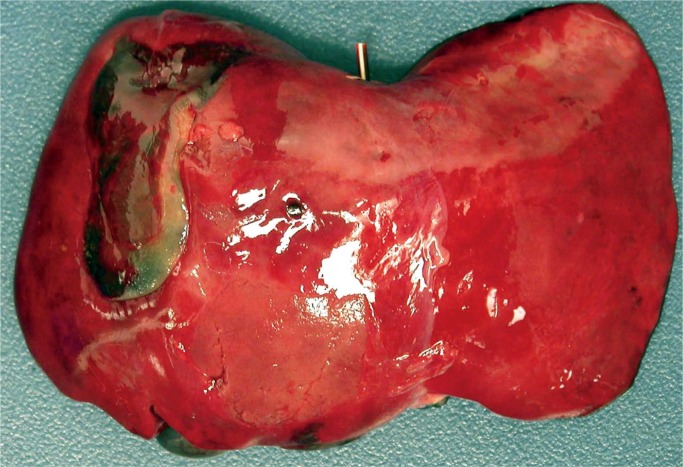

Image 75:

A resolving subcapsular hematoma on the dome of the right liver was found at autopsy of this 9-day-old.

Spleen

The spleen, an organ uncommon affected by birth trauma, can be damaged with or without associated hepatic injury. Risk factors are macrosomia, splenomegaly, erythroblastosis fetalis, and difficult delivery with increased thoracic pressure pushing the spleen downward. Grossly, a subcapsular hematoma at the splenorenal ligament can be identified. The capsule can rupture, usually after ten hours, and has been reported up to 14 days after delivery, leading to hemoperitoneum, scrotal/labial swelling and ecchymosis, and shock (30, 45 –47).

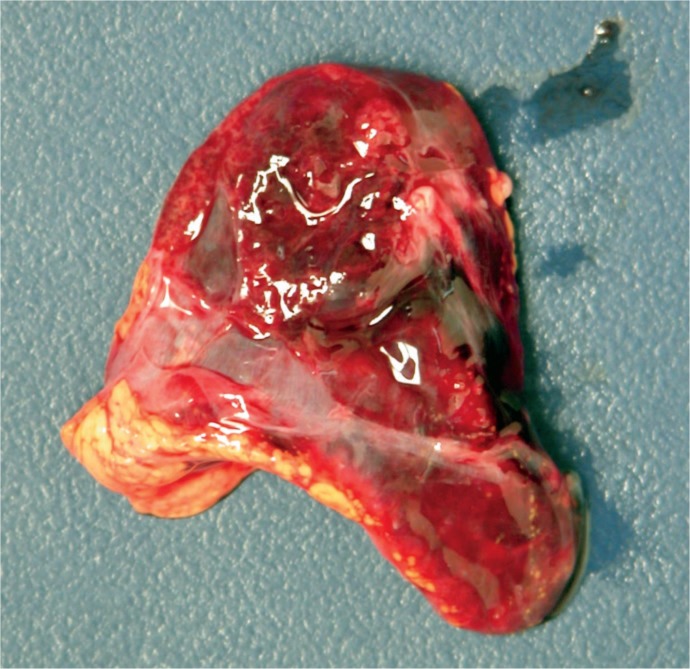

Adrenal Glands

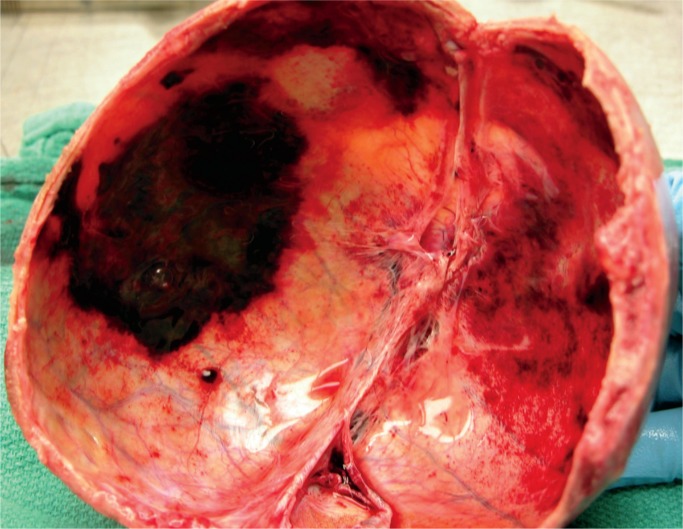

In neonates and infants, the adrenal glands are large and vulnerable to vascular damage and hemorrhage in 0.2% of newborns (Images 76 -78) (48). Risk factors are macrosomia, breech position, and fetal acidemia.

Image 76:

Adrenal hemorrhage – transverse ultrasound image of the right upper quadrant in a newborn boy shows a heterogeneous mass in the suprarenal fossa (arrows) representing adrenal hemorrhage. Image courtesy of Ellen M. Chung MD, Uniformed Services University.

Image 77:

Distorted adrenal gland secondary to hemorrhage due to birth trauma.

Image 78:

Cut section of the adrenal gland demonstrates the large acute hemorrhageT. he residual adrenal cortex is seen as a thin yellow line around the hematoma (arrow).

In 75% of cases, the right adrenal gland is involved, and most of the cases (90%) are unilateral (30, 48). As with the liver and spleen, the infant presents with abdominal mass, anemia, jaundice, and/or scrotal/labial swelling and ecchymosis. Adrenal insufficiency can occur.

Injuries from Resuscitation

Injuries can occur during resuscitation of a neonate (Images 79-80). These include facial and pharyngeal injury (trachea, larynx, esophagus perforation); barotrauma; pneumothorax, hemothorax, and hemoperitoneum; epicardial petechiae; liver injury; and injury to the umbilical vein during catherization (49).

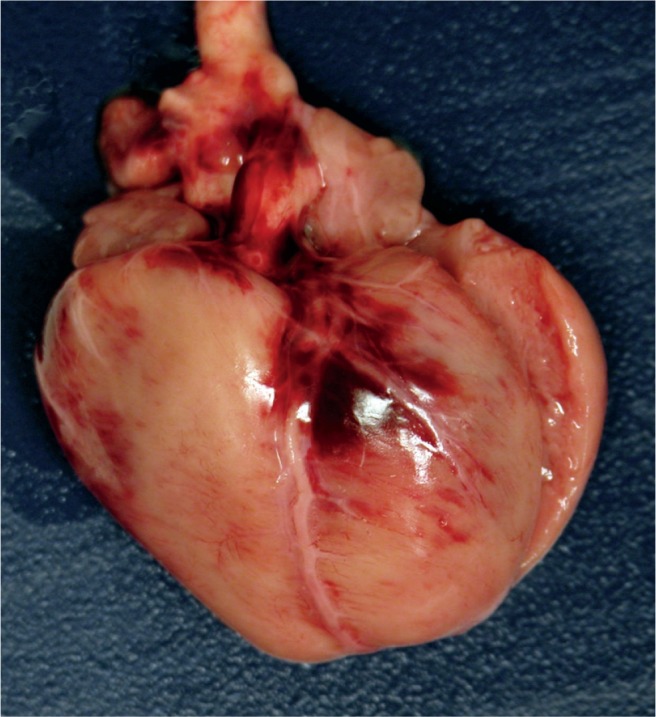

Image 79:

Anterior heart with contusion secondary to cardiac compressions during resuscitation at birth.

Image 80:

Pneumothorax on the right occurred during resuscitation at birth, seen on this postmortem radiograph (yellow arrow). There is also extensive subcutaneous pneumatosis. Small amounts of air can be reabsorbed if there is a long delay between death and radiograph (red arrows).

Conclusion

Birth injury, both birth asphyxia and birth trauma, has numerous etiologies. It is often difficult to determine whether acute injury to the fetus/neonate was an in utero, intrapartum, or postpartum event. Some of these are clinically insignificant and resolve within hours to days while others can result in lifelong morbidities. It is important to understand the various forms of birth trauma so that they can be identified preand postmortem, allowing for accurate treatment, diagnosis, and prevention. Understanding how such injuries occur, the healing times, and differentiating these traumatic injuries from inflicted trauma (gross, microscopic, and radiographic) is also imperative.

Author

Kim A. Collins MD FCAP, Forensic Pathologist

Roles: Project conception and/or design, data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work, principal investigator of the current study, principal investigator of a related study listed in the citations, general supervision, general administrative support, writing assistance and/or technical editing.

Edwina Popek DO, Texas Children’s Hospital

Roles: Project conception and/or design, data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work, principal investigator of the current study, principal investigator of a related study listed in the citations, general supervision, general administrative support, writing assistance and/or technical editing.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

Statement of Informed Consent: No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscript

Disclosures & Declaration of Conflicts of Interest: The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

Financial Disclosure: The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

References

- 1). Akangire G, Carter B. Birth injuries in neonates. Pediatr Rev. 2016. November; 37(11):451–62. PMID: 27803142 10.1542/pir.2015-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Chaturvedi A, Chaturvedi A, Stanescu AL, et al. Mechanical birthrelated trauma to the neonate: an imaging perspective. Insights Imaging. 2018. February; 9(1):103–18. PMID: 29356945. PMCID: PMC5825313 10.1007/s13244-017-0586-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). LaRossa DA, Ellery SJ, Walker DW, Dickinson H. Understanding the full spectrum of organ injury following intrapartum asphyxia. Front Pediatr. 2017. February 17; 5:16 PMID: 28261573. PMCID: PMC5313537 10.3389/fped.2017.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Peesay M. Nuchal cord and its implications. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2017. December 6; 3:28 PMID: 29234502. PMCID: PMC5719938 10.1186/s40748-017-0068-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Vasa R, Dimitrov R, Patel S. Nuchal cord at delivery and perinatal outcomes: single-center retrospective study, with emphasis on fetal acid-base balance. Pediatr Neonatol. 2018. October; 59(5):439–47. PMID: 29581058 10.1016/j.pedneo.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Gilliam-Krakauer M, Gowen CW. Birth Asphyxia. StatPearls [Internet]. [updated 2017 Feb 6; cited 2018 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.statpearls.com/kb/viewarticle/18335/.

- 7). Graham EM, Ruis KA, Hartman AL, et al. A systematic review of the role of intrapartum hypoxia-ischemia in the causation of neonatal encephalopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008. December; 199(6):587–95. PMID: 19084096 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Polglase GR, Ong T, Hillman NH. Cardiovascular alterations and multiorgan dysfunction after birth asphyxia. Clin Perinatol. 2016. September; 43(3):469–83. PMID: 27524448. PMCID: PMC4988334 10.1016/j.clp.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Campbell AG, Dawes GS, Fishman AP, Hyman AI. Regional re distribution of blood flow in the mature fetal lamb. Circ Res. 1967. August; 21(2):229–35. PMID: 4952710 10.1161/01.res.21.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Neonatal encephalopathy and neurologic outcome. 2nd ed Washington: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Pediatrics; 2014. 236 p. [Google Scholar]

- 11). Jenster M, Bonifacio SL, Ruel T, et al. Maternal or neonatal infection: association with neonatal encephalopathy outcomes. Pediatr Res. 2014. July; 76(1):93–9. PMID: 24713817. PMCID: PMC4062582 10.1038/pr.2014.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). de Vries L, Groendendaal F. Patterns of neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury. Neuroradiology. 2010. June; 52(6):555–66. PMID: 20390260. PMCID: PMC2872019 10.1007/s00234-010-0674-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Volpe JJ. Neurology of the newborn. 5th ed Philadelphia: Saunders; c2008. Chapter 8, Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: neuropathology and pathogenesis; p. 347–99. [Google Scholar]

- 14). Murata Y, Itakura A, Matsuzawa K, et al. Possible antenatal and perinatal related factors in development of cystic periventricular leukomalacia. Brain Dev. 2005. January; 27(1):17–21. PMID: 15626536 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Nelson K, Lynch JK. Stroke in newborn infants. Lancet Neurol. 2004. March; 3(3):150–8. PMID: 14980530 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00679-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Wei Y, Xu J, Xu T, et al. Left ventricular systolic function of newborns with asphyxia evaluated by tissue Doppler imaging. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009. August; 30(6):741–6. PMID: 19340476 10.1007/s00246-009-9421-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Beath SV. Hepatic function and physiology in the newborn. Semin Neonatol. 2003. October; 8(5):337–46. PMID: 15001122 10.1016/S1084-2756(03)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Chessells JM, Wigglesworth JS. Coagulation studies in severe birth asphyxia. Arch Dis Child. 1971. June; 46(247):253–6. PMID: 5090658. PMCID: PMC1647687 10.1136/adc.46.247.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Chadd MA, Elwood PC, Gray OP, Muxworthy SM. Coagulation defects in hypoxic full-term newborn infants. Br Med J. 1971. November 27; 4(5786):516–8. PMID: 5126955. PMCID: PMC1799783 10.1136/bmj.4.5786.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Neary E, McCallion N, Kevane B, et al. Coagulation indices in very preterm infants from cord blood and postnatal samples. J Thromb Haemost. 2015. November; 13(11):2021–30. PMID: 26334448 10.1111/jth.13130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Christensen RD, Baer VL, Yaish HM. Thrombocytopenia in late preterm and term neonates after perinatal asphyxia. Transfusion. 2015. January; 55(1):187–96. PMID: 25082082 10.1111/trf.12777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Saxonhouse MA, Rimsza LM, Stevens G, et al. Effects of hypoxia on megakaryocyte progenitors obtained from the umbilical cord blood of term and preterm neonates. Biol Neonate. 2006; 89(2):104–8. PMID: 16192692 10.1159/000088561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Vanpee M, Blennow M, Linne T, et al. Renal function in very low birth weight infants: normal maturity reached during early childhood. J Pediatr. 1992. November; 121(5 Pt 1):784–8. PMID: 1432434 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81916-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Saikumar P, Venkatachalam MA. Role of apoptosis in hypoxic/ischemic damage in the kidney. Semin Nephrol. 2003. November; 23(6):511–21. PMID: 14631559 10.1053/s0270-9295(03)00130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Gluckman PD, Watt JS, Azzopardi D, et al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: multicenter randomized trial. Lancet. 2005. February 19-25; 365(9460):663–70. PMID: 15721471 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17946-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Sakar S, Barks JD, Bhagat I, Donn SM. Effects of therapeutic hypothermia on multiorgan dysfunction in asphyxiated newborns: wholebody cooling versus selective head cooling. J Perinatol. 2009. August; 29(8):558–63. PMID: 19322190 10.1038/jp.2009.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Scott H. Outcome of very severe birth asphyxia. Arch Dis Child. 1976. September; 51(9):712–6. PMID: 1033733. PMCID: PMC1546242 10.1136/adc.51.9.712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Rabelo NN, Matushita H, Cardeal DD. Traumatic brain lesions in newborns. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2017. March; 75(3):180–8. PMID: 28355327 10.1590/0004-282X20170016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Huisman TAGM, Phelps T, Bosemani T, et al. Parturitional injury of the head and neck. J Neuroimaging. 2015. Mar-Apr; 25(2):151–66. PMID: 25040483 10.1111/jon.12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Collins KA. Forensic pathology of infancy and childhood. New York: Springer; c2014. Chapter 6, Birth trauma; p.139–68. [Google Scholar]

- 31). Brouwer AJ, Groenendaal F, Koopman C, et al. Intracranial hemorrhage in full-term newborns: a hospital-based cohort study. Neuroradiology. 2010. June; 52(6):567–76. PMID: 20393697. PMCID: PMC2872016 10.1007/s00234-010-0698-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Josephsen JB, Kemp J, Elbabaa SK, Al-Hosni M. Life threatening neonatal epidural hematoma caused by precipitous vaginal delivery. Am J Case Rep. 2015. January 30; 16:50–2. PMID: 25633886. PMCID: PMC4315626 10.12659/AJCR.892506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Hong HS, Lee JY. Intracranial hemorrhage in term neonates. Childs Nerv Syst. 2018. June; 34(6):1135–43. PMID: 29637304. PMCID: PMC5978839 10.1007/s00381-018-3788-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Fernando S, Obaldo RE, Walsh IR, Lowe LH. Neuroimaging of non accidental head trauma: pitfalls and controversies. Pediatr Radiol. 2008. August; 38(8):827–38. PMID: 18176805 10.1007/s00247-007-0729-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Noetzel MJ. Perinatal trauma and cerebral palsy. Clin Perinatol. 2006. June; 33(2):355–66. PMID: 16765729 10.1016/j.clp.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Hughes LA, May K, Talbot JF, Parsons MA. Incidence, distribution, and duration of birth-related retinal hemorrhages: a prospective study. J AAPOS. 2006. April; 10(2):102–6. PMID: 16678742 10.1016/j.jaapos.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Zhao Q, Zhang Y, Yang Y, et al. Birth-related retinal hemorrhages in healthy full-term newborns and their relationship to maternal, obstetric, and neonatal risk factors. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015. July; 253(7):1021–5. PMID: 25981120 10.1007/s00417-015-3052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Watts P, Maguire S, Kwok T, et al. Newborn retinal hemorrhages: a systematic review. J AAPOS. 2013. February; 17(1):70–8. PMID: 23363882 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39). Sheil AT, Collins KA. Fatal birth trauma due to an undiagnosed abdominal teratoma: case report and review of the literature. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2007. June; 28(2):121–7. PMID: 17525561 10.1097/01.paf.0000257373.91126.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40). Uhing MR. Management of birth injuries. Clin Perinatol. 2005. March; 32(1):19–38. PMID: 15777819 10.1016/j.clp.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41). Parker LA. Part 2: birth trauma: injuries to the intraabdominal organs, peripheral nerves, and skeletal system. Adv Neonatal Care. 2006. February; 6(1):7–14. PMID: 16458246 10.1016/j.adnc.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42). Somashekar DK, Di Pietro MA, Joseph JR, et al. Utility of ultrasound in noninvasive preoperative workup of neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Pediatr Radiol. 2016. May; 46(5):695–703. PMID: 26718200 10.1007/s00247-015-3524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43). Basha A, Amarin Z, Abu-Hassan F. Birth-associated long-bone fractures. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013. November; 123(2):127–30. PMID: 23992623 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44). Walters MM, Forbes PW, Buonomo C, Kleinman PK. Healing patterns of clavicular birth injuries as a guide to fracture dating in cases of possible infant abuse. Pediatri Radiol. 2014. October; 44(10):1224–9. PMID: 24777389 10.1007/s00247-014-2995-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45). Tiboni S, Abdulmajid U, Pooboni S, et al. Spontaneous splenic hemorrhage in the newborn. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2015. December; 3(2):71–3. PMID: 26788451. PMCID: PMC4712061 10.1055/s-0035-1564610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46). Hui CM, Tsui KY. Splenic rupture in a newborn. J Pediatr Surg. 2002. April; 37(4):1–3. 10.1053/jpsu.2002.31641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47). Ting JY, Lam BC, Ngai CS, et al. Splenic rupture in a premature neonate. Hong Kong Med J. 2006. February; 12(1):68–70. PMID: 16495593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48). Gyurkovits Z, Maroti A, Renes L, et al. Adrenal hemorrhage in term neonates: a retrospective study from the period 2001-2013. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015; 28(17):2062–5. PMID: 25327176 10.3109/14767058.2014.976550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49). Collins KA, Tatum CJ, Lantz PE. Forensic pathology of infancy and childhood. New York: Springer; c2014. Chapter 14, Cardiopulmonary resuscitation injuries in children; p.327–38. [Google Scholar]