Abstract

Stem Cell Antigen-1 (Sca-1/Ly6A) was the first identified member of the Lymphocyte antigen-6 (Ly6) gene family. Sca-1 serves as a marker of cancer stem cells and tissue resident stem cells in mice. The Sca-1 gene is located on mouse chromosome 15. While a direct homolog of Sca-1 in humans is missing, human chromosome 8—the syntenic region to mouse chromosome 15—harbors several genes containing the characteristic domain known as LU domain. The function of the LU domain in human LY6 gene family is not yet defined. The LY6 gene family proteins are present on human chromosome 6, 8, 11, and 19. The most interesting of these genes are located on chromosome 8q24.3, a frequently amplified locus in human cancer. Human LY6 genes represent novel biomarkers for poor cancer prognosis and are required for cancer progression in addition to playing an important role in immune escape. Although the mechanism associated with these phenotype is not yet clear, it is timely to review the current literature in order to address the critical need for future advancements in this field. This review will summarize recent findings which describe the role of human LY6 genes—LY6D, LY6E, LY6H, LY6K, PSCA, LYPD2, SLURP1, GML, GPIHBP1, and LYNX1; and their orthologs in mice at chromosome 15.

Keywords: LY6D, LY6E, LY6H, LY6K, TGF-β, Immune, Oncology

Introduction

Sca-1 is among the first identified members of the murine Ly6 gene family (1, 2). The Ly6 gene family belongs to the superfamily of lymphocyte antigen-6 (Ly6)/urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) proteins. This superfamily is characterized by the presence of LU domain. LU domain is a 60–80 amino acid domain, which is composed of 6–10 cysteines arranged in a specific spacing pattern that allows distinct disulfide bridges which create the three-fingered (3F) structural motif. Three-fingered structural motif are ancient proteins. The LU domain, a three-fingered motif in Ly6/uPAR family are believed to be the evolutionary ancestors of 3FTx toxins found in snake venom. The LU domain in human LY6/uPAR family is not toxic, exact function of LU domain is not yet defined. LU domain is also found in extracellular domains of cell-surface receptors with membrane spanning domain (activin type 2 receptor and bone morphogenetic type IA receptor), or in GPI-anchored proteins CD177 or in secreted globular proteins such CD59 antigen, SLURP1/2.

The LY6 gene family of proteins are located on human chromosomes 6, 8, 11, and 19 and the orthologs exist on syntenic areas of mouse chromosomes. The human chromosome 8 harbors genes namely PSCA, LY6K, SLURP1, LYPD2, LYNX1/SLURP2, LY6D, GML, LY6E, LY6L, LY6H, and GPIHBP1; while the syntenic mouse chromosome 15 contains genes Psca, Slurp1, Lypd2, Slurp2, Lynx, Ly6d, Ly6g6g, Ly6k, Gml, Gml2, Ly6m, Ly6e, Ly6i, Ly6a, Ly6c1, Ly6c2, Ly6a2, Ly6g, Ly6g2, Ly6f, Ly6l, Ly6h, and Gpihbp1. The human chromosome 19 harbors genes LYPD4, CD177, TEX101, LYPD3, PINLYP, PLAUR, LYPD5, and SPACA4; while the syntenic mouse chromosome 7 contains genes Lypd5, Plaur, Pinlyp, Lypd3, Tex101, Lypd10, Lypd11, Cd177, Lypd4, and Spaca4. The human chromosome 11 harbors genes ACRV1, PATE1, PATE2, PATE3, and PATE4, CD59; while the syntenic mouse chromosome 9 contains genes Pate4, Pate2, Pate13, Pate3, Pate1, Pate10, Pate7, Pate6, Pate5, Pate12, Pate11, Pate9, Pate8, Pate14, and Acrv1. The human chromosome 6 harbors genes LY6G6C, LY6G6D, LY6G6F, LY6G5C, and LY6G5B while the syntenic mouse chromosome 17 contains genes Ly6g6c, Ly6g5c, Ly6g5b, Ly6g6d, Ly6g6f, and Ly6g6e (2). Many of the mice Ly6 genes were lost in humans, perhaps due to their redundant function during evolution (3).

In this mini review, we will focus on the role of human LY6 gene family located on the chromosome 8 namely LY6D, LY6E, LY6H, LY6K, PSCA, LYPD2, SLURP1, GML, GPIHBP1, and LYNX1 and their orthologs in mice at chromosome 15. We chose to focus on this set of genes as they have shown to be increased in human cancer. It is to note that the most widely studied murine Ly6 gene on chromosome 15, Sca-1/Ly6A does not have a human ortholog. It is not clear which gene in human Ly6 gene family may be functionally similar to Sca-1 or the multiple genes may perform several important Sca-1 functions. Sca-1 protein is the most common cell surface marker that is used to enrich adult hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Sca-1 protein expression is variable depending on the stages of differentiation of HSCs. Sca-1 protein expression is reduced in HSCs that have differentiated to common myeloid progenitors and then re-expressed in subsets of myeloid progenitors. In a similar pattern, HSCs differentiating into progenitor population suppress Sca-1 expression and immature thymocytes have turned off the Sca-1 protein expression whereas mature single positive thymocytes and peripheral T- cells regain Sca-1 protein expression (4). Sca-1 protein expression has also been identified as an important regulator of tumor progression in mouse models of cancer (5–7). Although the role of LY6 genes on human chromosome 8 in immune cells is not yet established, their role in cancer progression is rapidly emerging. Therefore, we will discuss recent advances, current research gaps and critical need for future research regarding members of the LY6 gene family namely LY6D, LY6E, LY6H, LY6K, PSCA, LYPD2, SLURP1, GML, GPIHBP1, and LYNX1; and their orthologs in mice at chromosome 15.

Lessons Learned From the Phenotype of Knockout Mice

The knockout mice models for mouse Ly6 genes with human orthologs—namely Ly6E, Ly6K, Lynx1, Slurp1, and Gpihbp1 have been described (Table 1). The other family members have not been characterized in the knockout mice model. The phenotype and the characterization of the known knockout mice models are as described below, which offer important insight into the function of these genes.

Table 1.

The phenotype of knockout mice model of Ly6 gene family members.

| Gene name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | Human ortholog | Knockout (−/−) mice, phenotype | Mechanism behind the phenotype |

| Ly6E | Ly6E | Embryonic lethal due to placental defect | SynTA receptor pathway |

| Ly6K | Ly6K | Viable adult male (infertile) and female (fertile) | Unknown |

| Lynx1 | Lynx1 | Viable adult mice with no apparent phenotype | Not Applicable |

| Slurp1 | Slurp1 | Viable adult mice with palmoplantar keratoderma, metabolic and neuromuscular abnormal phenotype | Unknown |

| GPIHBP1 | GPIHBP1 | Viable adult mice with hypertriglyceridemia phenotype | Lipolysis pathway |

The mouse Ly6 genes namely Ly6E, Ly6K, Slurp1, Lynx1, and Gpihbp1 have mouse orthologs and they have knockout mice described. The mouse Ly6 genes namely Pcsa, Lypd2, Ly6D, Gml, and Ly6H have human orthologs but the knockout mice have not been described. The mouse Ly6 genes Sca1, Ly6I/M, Ly6C1, Ly6C2, Ly6B, Ly6G, BC025446, 9030619P08Rik don't have human orthologs. Among these genes only Sca1 has been described in a knockout mice model.

Ly6E: The mouse Ly6E gene was deleted by gene targeting in mice to create homozygous knockout mice (8). Animals with a Ly6E−/− mutation showed embryonic lethality at E14.5. It was though that embryonic lethality was due to cardiac malformation. It was later resolved that Ly6E knockout induced lethality was due the critical role of Ly6E in the trophoblast stem cells (9). The trophoblast forms the outer layer of fetal part of the placenta. Ly6E is expressed specifically in the syncytiotrophoblast (SynT-I) cells (10). Ly6E was found to be a possible receptor for Syncytin A ligand (11). The syncytiotrophoblast layer of fetal placenta play important role in connecting with maternal placenta for the proper exchange of nutrients. In the absence of Ly6E in the fetal placenta, this fetal-maternal placental vascularization is not well-formed causing harm to the fetus. The role of Ly6E in human placental development has not yet been described. Thymic development was found to be normal in Ly6E−/− mice, suggesting that Ly6E may play a redundant role in thymic development and development of immune cells.

Ly6K: The mouse Ly6K gene knockout mice were generated using a targeting vector substituting exons 2, 3, and 4 (12). Adult Ly6K−/− mutant male mice were found to be infertile. Female Ly6K−/− mutant mice had normal fertility. Ly6K is not expressed in mature spermatozoa, however the spermatozoa from Ly6K−/− mutant male mice were unable to migrate into the oviduct (12). The reason for Ly6K associated migration defects in sperm of adult mice is not yet known. The role of Ly6K in human sperm related infertility is not yet described.

Slurp1: The mouse Slurp1 gene is a secreted member of the Ly6 gene family. The deficiency and mutations in human SLURP1 gene causes Mal de Meleda (MDM), a rare autosomal recessive genetic disease, characterized by inflammatory palmoplantar keratoderma (13, 14). Slurp1−/− mutant mice exhibit this rare palmoplantar keratoderma, and show metabolic phenotypes such as reduced adiposity, protection from obesity on a high-fat diet, low plasma lipid levels, and neuromuscular abnormalities such as hind-limb clasping (15).

Gpihbp1: Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high-density lipoprotein-binding protein 1 (Gpihbp1) deficient mice on a regular chow diet display accumulation of chylomicrons in the plasma and high plasma triglyceride levels (16). Gpihbp1−/− mice show reciprocal metabolic perturbations in adipose tissue and liver due to defective lipolysis (17). These results suggest that human GPIHBP1 gene may play important role in the lipolytic processing of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins.

Lynx1: Ly6 neurotoxin1 (Lynx1) knockout mice display increased visual cortex plasticity in mice (18). The Lynx1−/− phenotype was partially derived from the inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor signaling by Lynx1 (18). These results suggest that human LYNX1 gene may play important role in nicotine response in the brain.

Expression of Mouse Ly6 Genes in Immune Cells

The expression of many mouse Ly6 gene family proteins are lineage specific and their expression coincides with the differentiation stages of leukocyte cell populations as seen in the mouse model. The role of human LY6 genes in immune cells differentiation is still not clear. These properties have made them attractive targets to be used for subset identification of leukocytes in vitro and antibody-mediated depletion of specific immune cell populations in vivo. Recently, Nigrovic et al. summarized the mRNA expression of mice Ly6 genes in B-cells, T-cells, NK cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells based on data from the Immgen database (3). Ly6E RNA expression was expressed on all tested immune cell subtypes in the Immgen database. Ly6D RNA was expressed in B-cells, T-cells and dendritic cells. Lypd2, which was described in non-classical monocytes (19). Ly6F, Ly6H, Ly6K, Gml, Psca, Gpihbp1 RNA expression was not found to be associated with expression on immune cells in mice. Interestingly, the mice genes namely Sca1, Ly6B, Ly6C, Ly6G, Ly6I/Ly6M, and Ly6F RNA expression have found to be expressed on many immune cells types in mice. These genes do not have human orthologs. It is yet to be discovered which human genes may function similar to these mice genes. The mRNA expression for Ly6A/Sca1 was found to be present in B-cells, T-cells and dendritic cells (3). Ly6B RNA expression was found in NK cells, monocytes and neutrophils but absent from B-cells, T-cells and dendritic cells. Ly6C RNA expression was found to be present in all subsets except T cells. Ly6G RNA expression was only present in neutrophils and absent from all other cell types analyzed. Ly6I/Ly6M RNA expression was present only in monocytes and neutrophils and absent in all other cell types. It has been shown that RNA and protein expression for some of the human LY6 gene family members such as GML (20, 21), LY6K (22, 23), PSCA (24, 25), and LY6E (23, 26) have immune-modulatory properties in tumor microenvironment.

LY6E and LY6D are the only two genes on human chromosome 8 with a mouse ortholog on chromosome 15, for which some data is available to describe their expression and function in immune cells using mouse models, as discussed below. These genes have been shown to be important in the proliferation and differentiation of immune cells using mainly in vitro methods (3, 27). The mechanistic basis behind the differentiation specific expression remains to be fully understood.

Ly6D: The mRNA for mouse Ly6D gene was found to be present in B-cells, T-cells and dendritic cells and absent in NK cells, monocytes, and neutrophils (3). Recent in vitro studies indicate that Ly6D gene is expressed in common lymphoid progenitors which arise from hematopoietic stem cells and give rise to B-lineage lymphocytes (28). Mouse Ly6D gene expression is associated with B-cell specification (29). Ly6D and SiglecH gene expression positive cells from IL7R positive lymphoid progenitor cell populations were committed to become plasmacytoid dendritic cells, while double negative cells were uncommitted. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are an immune subset devoted to the production of high amounts of type 1 interferon in response to viral infections (30).

Ly6E: The mouse Ly6E gene is expressed in peripheral B-cells, immature T-cells, activated T cells, thymus stromal cells, and macrophages (3). A functional role of Ly6E was reported in maintenance of self-renewal of erythroid progenitors (31).

Expression of Human LY6 Genes in Normal (Non-lymphoid) Tissues

LY6D: Human LY6D RNA and protein is expressed in normal esophageal and skin as published by the human protein atlas on www.proteinatlas.org (32–36).

LY6E: Human LY6E RNA is expressed in normal liver, fetal placenta, lung, and spleen (32–36).

LY6H: Human LY6H RNA is expressed in brain (32–36).

LY6K: Human LY6K RNA and protein is expressed in normal testis (32–36).

PSCA: Human PSCA RNA is expressed in prostate, urinary bladder, and esophagus (32–36).

LYPD2: Human LYPD2 RNA is expressed in esophagus and tonsil (32–36).

SLURP1: Human SLURP1 RNA is expressed in esophagus and skin (32–36).

GML: Human GML RNA is expressed in testis and adrenal gland (32–36).

GPIHBP1: Human GPIHBP1 RNA is expressed in adipose, lung, breast, brain, heart and soft (32–36).

Expression of Human LY6 Genes Is Associated With Cancer and Outcome of the Disease

The LY6D, LY6E, Ly6K, and Ly6H RNA is expressed at high levels compared to adjacent normal tissues in a multitude of tumors including ovarian, colorectal, gastric, breast, lung, bladder, brain and CNS, cervical, esophageal, head and neck, and pancreatic cancer. The increased expression of LY6D, LY6E, LY6K, and LY6H was associated with poor survival in ovarian, colorectal, gastric, breast, and lung cancer (37) (Table 2). The casual reason for the increased expression of LY6 family proteins and the poor survival outcome is not yet established. As discussed further in the review under cell signaling heading, LY6 proteins play important role in TGFβ signaling, AKT pathways and immune regulation. A cumulative effect of Ly6 downstream pathways may lead to increased aggressiveness of cancer cells and leading to poor survival outcome. More mechanistic studies will need to be performed to determine the precise pathways responsible for poor survival outcome in patients.

Table 2.

Correlation of high mRNA expression and patient survival outcome in multiple cancer types.

| Cancer type | Genes | Expression in tumors (p < 0.05) | Survival analysis (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ovarian | LY6D | Up | Poor prognosis |

| LY6E | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| LY6H | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| LY6K | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| Colorectal | LY6D | Up | Poor prognosis |

| LY6E | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| LY6H | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| LY6K | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| Gastric | LY6D | Up | Poor prognosis |

| LY6E | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| LY6H | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| LY6K | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| Breast | LY6D | Up | Poor prognosis |

| LY6E | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| LY6H | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| LY6K | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| Lung | LY6D | Up | Poor prognosis |

| LY6E | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| LY6H | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) | |

| LY6K | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| Bladder | LY6D | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) |

| LY6E | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| LY6H | NS | OS (NS), Others (NA) | |

| LY6K | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| Brain and CNS | LY6D | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) |

| LY6E | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| LY6H | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) | |

| LY6K | Up | Poor prognosis | |

| Cervical | LY6D | Up | OS (NA), RFS (NS) |

| LY6E | Up | OS (NA), RFS (NS) | |

| LY6H | Up | OS (NA), RFS (NS) | |

| LY6K | Up | OS (NA), RFS (NS) | |

| Esophageal | LY6D | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) |

| LY6E | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) | |

| LY6H | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) | |

| LY6K | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) | |

| Head and neck | LY6D | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) |

| LY6E | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) | |

| LY6H | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) | |

| LY6K | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) | |

| Pancreatic | LY6D | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) |

| LY6E | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) | |

| LY6H | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) | |

| LY6K | Up | OS (NS), Others (NA) |

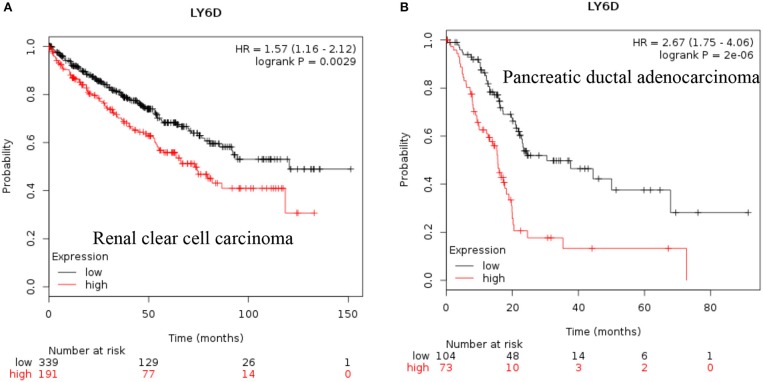

LY6D: Recent clinical outcome data added and published by Km plotter web tool show that increased RNA expression of LY6D is associated with poor prognosis in renal clear cell carcinoma and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [Figure 1, (38)]. Recently, LY6D expression—in addition to OLFM4 and S100A7—was found to be associated with distant metastasis of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer (39). LY6D has also been shown to be increased in aggressive forms of head and neck cancer (40).

Figure 1.

Increased LY6D mRNA expression in cancer and patient survival. High LY6D RNA expression leads to poor survival in (A) renal clear cell carcinoma, (B) pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. These data were recently added in Km plotter webtool from RNA seq pan cancer analysis (38).

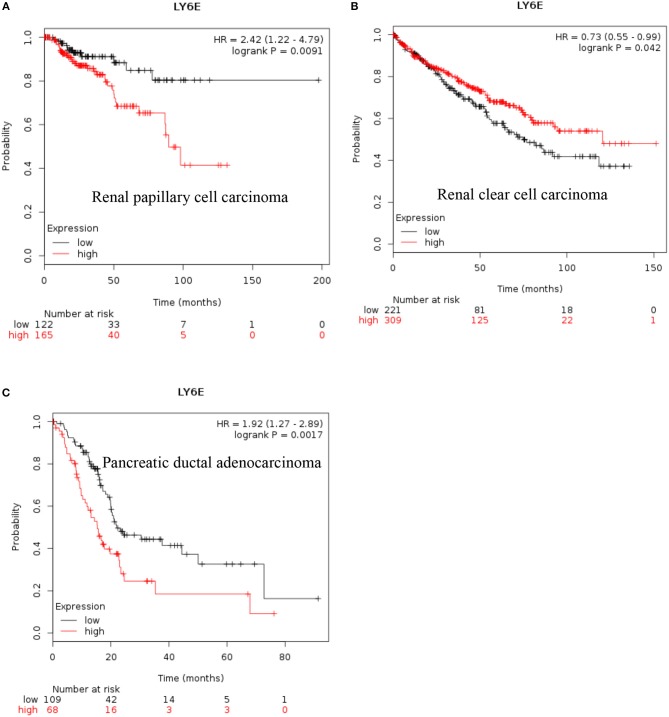

LY6E: Recent data also show that increased expression of LY6E is associated with poor overall survival of renal papillary cell carcinoma and is a good prognostic marker for renal clear cell carcinoma [Figures 2A,B, (38)]. These new data indicated that increased expression of LY6E is associated with poor overall survival of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [Figure 2C, (38)]. The use of genome wide data analysis has prompted several new reports showing increased expression of Ly6E in bladder cancer, gastric cancer (39, 40). The LY6E gene has been also associated with more aggressive stem like cells in hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma, colon, and kidney (41–43).

Figure 2.

Increased LY6E mRNA expression in cancer and patient survival. High LY6E RNA expression leads to (A) poor survival in renal papillary cell carcinoma, (B) good prognosis for renal clear cell carcinoma, (C) poor survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. These data were recently added in Km plotter webtool from RNA seq pan cancer analysis (38).

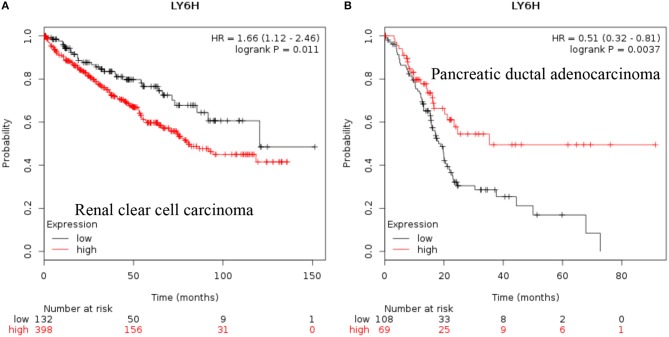

LY6H: Recent data shows that increased expression of Ly6H is associated with poor overall survival of renal clear cell carcinoma and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [Figure 3, (38)].

Figure 3.

Increased LY6H mRNA expression in cancer and patient survival. High LY6H RNA expression leads to poor survival in (A) renal clear cell carcinoma, (B) pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (38).

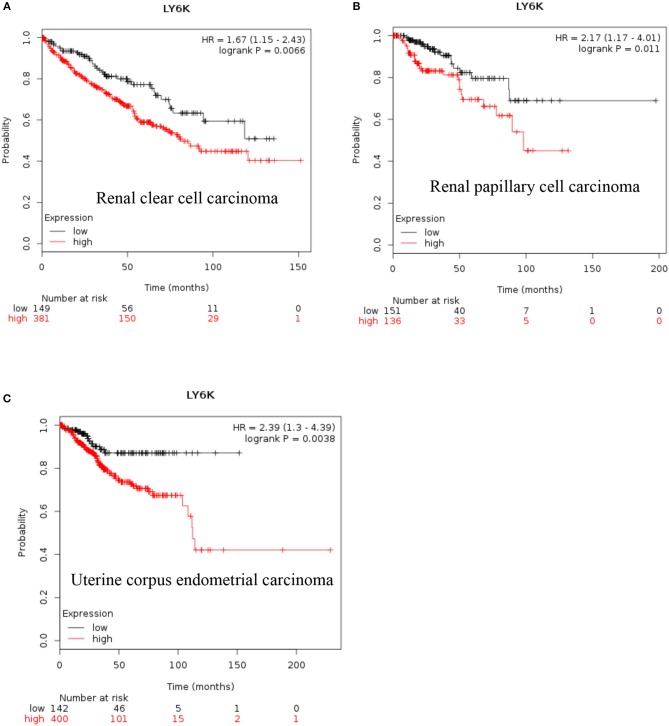

LY6K: Increased expression of LY6K has also been reported in metastatic ER positive breast cancer (41–43), esophageal squamous cancer (44), gingivobuccal cancers (45), bladder cancer (46), and lung cancer (47). Recent data also show that increased expression of LY6K is associated with poor overall survival of renal clear cell carcinoma, renal papillary cell carcinoma and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma [Figure 4, (38)].

Figure 4.

Increased LY6K mRNA expression in cancer and patient survival. High Ly6K RNA expression leads to poor survival in (A) renal clear cell carcinoma, (B) renal papillary cell carcinoma and, (C) pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (38).

PSCA: Prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA) RNA is expressed at high levels compared to adjacent normal tissues in prostate and pancreatic tumors as well as in glioma (48, 49). PSCA is downregulated in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma where it can act as a tumor suppressor by facilitating the nuclear translocation of RB1CC1 (50). Bioinformatics studies have indicated that polymorphisms rs2294008 in the PSCA gene may be prognostic in nature, however this association remains inconclusive due to contradictory observation and a lack of in vitro or in vivo experimental evidence (51–53).

LYPD2: LYPD2 RNA is expressed at high levels compared to adjacent normal tissues in cervical and head and neck cancer are associated with a favorable prognosis as shown by the human protein atlas (32).

SLURP1: SLURP1 RNA expression is reduced in metastatic melanoma (13). The prognostic value of Slurp1 is unknown.

GML: GML RNA expression is increased in non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) expressing wild-type P53 or P53 negative tumors. This specific expression of GML in P53 negative tumors was found to be linked to cisplatin sensitivity in NSCLC (54). The prognostic value of GML is not clear.

GPIHBP1: GPIHBP1 RNA and protein is increased in renal cancer (32–35). The prognostic value of GPIHBP1 is unknown.

Role of Human LY6 Genes in Other (Non-cancer) Diseases

LY6D: A single nucleotide polymorphism rs2572886 found in the human LY6D and Ly6PD2 genes is associated with cellular infection susceptibility to HIV-1 in lymphoblastoid B-cells and in primary T-cells and was also associated with accelerated disease progression in one of two cohorts of HIV-1–infected patients (55).

LY6E: LY6E expression is up-regulated during chronic HIV infection (26, 56). Using a HIV pathogenesis model, it was shown that LY6E can down-regulate monocyte responsiveness by modulating CD14 expression via an unknown mechanism (26). Recently, LY6E was shown to enhance viral infectivity IFN dependent fashion (57).

GPIHBP1: GPIHBP1 is an endothelial cell specific protein. It facilitates triglyceride (TG) lipolysis in the endothelial cells surface by binding to lipoprotein lipase (LPL), which releases nutrients to surrounding tissues (58). Four missense mutations in highly conserved residues in GPIHBP1 (C65Y, C65S, C68G, and Q115P) gene were identified in severe chylomicronemia leading to buildup of triglyceride causing health issues such as pancreatitis (59).

Cell Signaling Pathways Associated With Human LY6 Genes

The LY6 proteins are glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored cell surface proteins, the regulation of LY6 RNA and protein is not yet understood very well.

TGF-β Signaling

Molecular analysis showed that LY6E and LY6K contribute to tumorigenic progression by increased TGF-β signaling, immune escape and increased INF-γ signaling (23).

PI3K Signaling

The PTEN and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways are involved in LY6E-mediated increase in HIF-1α transcription (60).

Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Signaling

LYNX1, SLURP1, PSCA, and LY6H can modulate α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) signaling. The α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) protein is expressed in the central and peripheral nervous system (CNS), muscle, lung, and placenta. The nAChR signaling is associated with nicotine addiction, cancers of lung and liver, and preeclampsia (61, 62). In the brain, activation of α7nAChR in macrophages inhibits production of inflammatory cytokines (63). In colorectal cancer, the activation of α7nAChR in tumor macrophages inhibits colorectal cancer metastasis through the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway (64). α7nAChR has been considered an important drug target for the inhibition of lung cancer (65). On a cautionary note, α7nAChR is such an important neurotransmitter receptor in the CNS and muscle, that targeting nicotinic signaling directly via α7nAChR may cause multiple unwanted side effects. Nicotinic signaling can be modulated by multiple members of the LY6 gene family including LYNX1/2, SLURP1/2, and PSCA (66). Nicotinic signaling can affect glutamatergic signaling in in the hippocampus which may impact learning and memory. One member of LY6 family, LY6H have shown to play important role in glutamatergic signaling in the brain (67). It is yet to be determined if LY6H or other members of LY6 gene family regulate cross talk of nicotinic signaling and glutamergic signaling in the brain.

Concluding Remarks

LY6 gene family members have the potential to be used as therapeutic targets. Several approaches including small molecules and antibody neutralization may be suitable in targeting LY6 family proteins. Ly6E protein expression was identified as a highly promising target for molecular antibody drug conjugates directed to solid tumors in animal models which show high RNA expression of LY6E (68). LY6D, LY6E, LY6H, and LY6K may be used in targeted cancer therapy, provided that future in-depth mechanistic studies reveal the signaling networks of these proteins in physiology and disease [Figure 5, (37)]. GPIHBP1 mimicking small molecules will have the potential to treat defective lipolysis of triglyceride due to mutated GPIHBP1. In depth analysis of regulation of LY6 gene expression and identification of downstream targets of LY6 proteins are required to better understand LY6 biology. The α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) signaling is at the center of a number of diseases including schizophrenia, Alzheimer's disease, chronic pain and inflammatory diseases (69). Therefore, the LY6 gene family members such as LYNX1, SLURP1, PSCA, and LY6H which modulate α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) signaling may be considered for the tissue-specific modulation of the nAChR pathway.

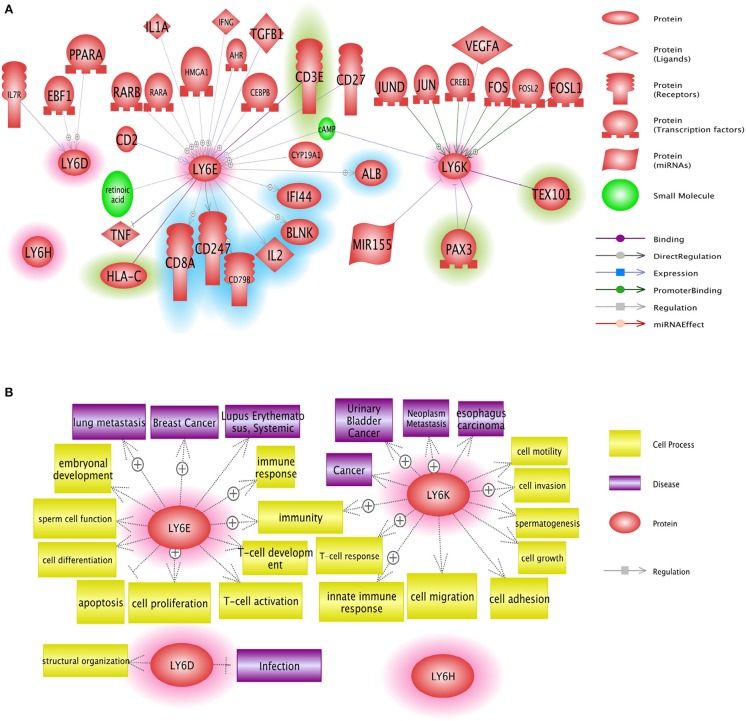

Figure 5.

Network analysis of Ly6D, Ly6E, Ly6K, and Ly6H genes. (A) Pathway studio network analysis showed that LY6 signaling is involved in broad range of molecules including growth factor, nuclear receptor, and micro RNAs. The upstream regulators are not highlighted, the downstream effectors are highlighted with blue, and the potential binding partners are highlighted with green. (B) Pathway studio network analysis showed that Ly6 gene family affect multitude of cellular fate and cell-cell interaction with microenvironment ranging from growth, apoptosis, autophagy, immune response (37).

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. The work was supported by NCI R01CA227694 and USUHS startup funds to GU.

References

- 1.Yutoku M, Grossberg AL, Pressman D. A cell surface antigenic determinant present on mouse plasmacytes and only about half of mouse thymocytes. J Immunol. (1974) 112:1774–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loughner CL, Bruford EA, McAndrews MS, Delp EE, Swamynathan S, Swamynathan SK. Organization, evolution and functions of the human and mouse Ly6/uPAR family genes. Hum Genomics. (2016) 10:10. 10.1186/s40246-016-0074-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee PY, Wang JX, Parisini E, Dascher CC, Nigrovic PA. Ly6 family proteins in neutrophil biology. J Leukoc Biol. (2013) 94:585–94. 10.1189/jlb.0113014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morcos NFM, Schoedel KB, Hoppe A, Behrendt R, Basak O, Clevers HC, et al. SCA-1 expression level identifies quiescent hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Stem Cell Rep. (2017) 8:1472–8. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan JP, Minna JD. Tumor oncogenotypes and lung cancer stem cell identity. Cell Stem Cell. (2010) 7:2–4. 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ceder JA, Aalders TW, Schalken JA. Label retention and stem cell marker expression in the developing and adult prostate identifies basal and luminal epithelial stem cell subpopulations. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2017) 8:95. 10.1186/s13287-017-0544-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dall GV, Vieusseux JL, Korach KS, Arao Y, Hewitt SC, Hamilton KJ, et al. SCA-1 labels a subset of estrogen-responsive bipotential repopulating cells within the CD24(+) CD49f(hi) mammary stem cell-enriched compartment. Stem Cell Rep. (2017) 8:417–31. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zammit DJ, Berzins SP, Gill JW, Randle-Barrett ES, Barnett L, Koentgen F, et al. Essential role for the lymphostromal plasma membrane Ly-6 superfamily molecule thymic shared antigen 1 in development of the embryonic adrenal gland. Mol Cell Biol. (2002) 22:946–52. 10.1128/MCB.22.3.946-952.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langford MB, Outhwaite JE, Hughes M, Natale RCD, Simmons DG. Deletion of the syncytin A receptor Ly6e impairs syncytiotrophoblast fusion and placental morphogenesis causing embryonic lethality in mice. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:3961. 10.1038/s41598-018-22040-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes M, Natale BV, Simmons DG, Natale DR. Ly6e expression is restricted to syncytiotrophoblast cells of the mouse placenta. Placenta. (2013) 34:831–5. 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bacquin A, Bireau C, Tanguy M, Romanet C, Vernochet C, Dupressoir A, et al. A cell fusion-based screening method identifies glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein Ly6e as the receptor for mouse endogenous retroviral envelope syncytin-A. J Virol. (2017) 91:e00832–17. 10.1128/JVI.00832-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujihara Y, Okabe M, Ikawa M. GPI-anchored protein complex, LY6K/TEX101, is required for sperm migration into the oviduct and male fertility in mice. Biol Reprod. (2014) 90:60. 10.1095/biolreprod.113.112888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergqvist C, Kadara H, Hamie L, Nemer G, Safi R, Karouni M, et al. SLURP-1 is mutated in Mal de Meleda, a potential molecular signature for melanoma and a putative squamous lineage tumor suppressor gene. Int J Dermatol. (2018) 57:162–70. 10.1111/ijd.13850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Favre B, Plantard L, Aeschbach L, Brakch N, Christen-Zaech S, de Viragh PA, et al. SLURP1 is a late marker of epidermal differentiation and is absent in Mal de Meleda. J Invest Dermatol. (2007) 127:301–8. 10.1038/sj.jid.5700551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adeyo O, Allan BB, Barnes RH II, Goulbourne CN, Tatar A, Tu Y, et al. Palmoplantar keratoderma along with neuromuscular and metabolic phenotypes in Slurp1-deficient mice. J Invest Dermatol. (2014) 134:1589–98. 10.1038/jid.2014.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beigneux AP, Davies BS, Gin P, Weinstein MM, Farber E, Qiao X, et al. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high-density lipoprotein-binding protein 1 plays a critical role in the lipolytic processing of chylomicrons. Cell Metab. (2007) 5:279–91. 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinstein MM, Goulbourne CN, Davies BS, Tu Y, Barnes RH II, Watkins SM, et al. Reciprocal metabolic perturbations in the adipose tissue and liver of GPIHBP1-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2012) 32:230–5. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morishita H, Miwa JM, Heintz N, Hensch TK. Lynx1, a cholinergic brake, limits plasticity in adult visual cortex. Science. (2010) 330:1238–40. 10.1126/science.1195320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyons YA, Wu SY, Overwijk WW, Baggerly KA, Sood AK. Immune cell profiling in cancer: molecular approaches to cell-specific identification. NPJ Precis Oncol. (2017) 1:26. 10.1038/s41698-017-0031-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang MS, Sandouk A, Houtman JC. Glycerol Monolaurate (GML) inhibits human T cell signaling and function by disrupting lipid dynamics. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:30225. 10.1038/srep30225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witcher KJ, Novick RP, Schlievert PM. Modulation of immune cell proliferation by glycerol monolaurate. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. (1996) 3:10–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomita Y, Yuno A, Tsukamoto H, Senju S, Kuroda Y, Hirayama M, et al. Identification of immunogenic LY6K long peptide encompassing both CD4(+) and CD8(+) T-cell epitopes and eliciting CD4(+) T-cell immunity in patients with malignant disease. Oncoimmunology. (2014) 3:e28100. 10.4161/onci.28100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.AlHossiny M, Luo L, Frazier WR, Steiner N, Gusev Y, Kallakury B, et al. Ly6E/K signaling to TGFbeta promotes breast cancer progression, immune escape, and drug resistance. Cancer Res. (2016) 76:3376–86. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao L, Joo KI, Lim M, Wang P. Dendritic cell-directed vaccination with a lentivector encoding PSCA for prostate cancer in mice. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e48866. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saeki N, Ono H, Sakamoto H, Yoshida T. Down-regulation of Immune-related genes by PSCA in gallbladder cancer cells implanted into mice. Anticancer Res. (2015) 35:2619–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu X, Qiu C, Zhu L, Huang J, Li L, Fu W, et al. IFN-stimulated gene LY6E in monocytes regulates the CD14/TLR4 pathway but inadequately restrains the hyperactivation of monocytes during chronic HIV-1 infection. J Immunol. (2014) 193:4125–36. 10.4049/jimmunol.1401249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gumley TP, McKenzie IF, Sandrin MS. Tissue expression, structure and function of the murine Ly-6 family of molecules. Immunol Cell Biol. (1995) 73:277–96. 10.1038/icb.1995.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Q, Esplin BL, Iida R, Garrett KP, Huang ZL, Medina KL, et al. RAG-1 and Ly6D independently reflect progression in the B lymphoid lineage. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e72397. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inlay MA, Bhattacharya D, Sahoo D, Serwold T, Seita J, Karsunky H, et al. Ly6d marks the earliest stage of B-cell specification and identifies the branchpoint between B-cell and T-cell development. Genes Dev. (2009) 23:2376–81. 10.1101/gad.1836009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodrigues PF, Alberti-Servera L, Eremin A, Grajales-Reyes GE, Ivanek R, Tussiwand R. Distinct progenitor lineages contribute to the heterogeneity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. (2018) 19:711–22. 10.1038/s41590-018-0136-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bresson-Mazet C, Gandrillon O, Gonin-Giraud S. Stem cell antigen 2:a new gene involved in the self-renewal of erythroid progenitors. Cell Prolif . (2008) 41:726–38. 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00554.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uhlen M, Zhang C, Lee S, Sjostedt E, Fagerberg L, Bidkhori G, et al. A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Science. (2017) 357:eaan2507. 10.1126/science.aan2507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uhlen M, Oksvold P, Fagerberg L, Lundberg E, Jonasson K, Forsberg M, et al. Towards a knowledge-based human protein atlas. Nat Biotechnol. (2010) 28:1248–50. 10.1038/nbt1210-1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. (2015) 347:1260419. 10.1126/science.1260419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uhlen M, Bjorling E, Agaton C, Szigyarto CA, Amini B, Andersen E, et al. A human protein atlas for normal and cancer tissues based on antibody proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. (2005) 4:1920–32. 10.1074/mcp.M500279-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, Deshpande N, Varambally R, Ghosh D, et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia. (2004) 6:1–6. 10.1016/S1476-5586(04)80047-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo L, McGarvey P, Madhavan S, Kumar R, Gusev Y, Upadhyay G. Distinct lymphocyte antigens 6 (Ly6) family members Ly6D, Ly6E, Ly6K, and Ly6H drive tumorigenesis and clinical outcome. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:11165–93. 10.18632/oncotarget.7163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menyhart O, Nagy A, Gyorffy B. Determining consistent prognostic biomarkers of overall survival and vascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. R Soc Open Sci. (2018) 5:181006. 10.1098/rsos.181006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayama A, Takagi K, Suzuki H, Sato A, Onodera Y, Miki Y, et al. OLFM4, LY6D, and S100A7 as potent markers for distant metastasis in estrogen receptor-positive breast carcinoma. Cancer Sci. (2018) 109:3350–9. 10.1111/cas.13770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colnot DR, Nieuwenhuis EJ, Kuik DJ, Leemans CR, Dijkstra J, Snow GB, et al. Clinical significance of micrometastatic cells detected by E48 (Ly-6D) reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction in bone marrow of head and neck cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. (2004) 10:7827–33. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kong HK, Yoon S, Park JH. The regulatory mechanism of the LY6K gene expression in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. (2012) 287:38889–900. 10.1074/jbc.M112.394270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kong HK, Park SJ, Kim YS, Kim KM, Lee HW, Kang HG, et al. Epigenetic activation of LY6K predicts the presence of metastasis and poor prognosis in breast carcinoma. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:55677–89. 10.18632/oncotarget.10972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim YS, Park SJ, Lee YS, Kong HK, Park JH. miRNAs involved in LY6K and estrogen receptor alpha contribute to tamoxifen-susceptibility in breast cancer. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:42261–73. 10.18632/oncotarget.9950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang B, Zhang Z, Zhang X, Gao X, Kernstine KH, Zhong L. Serological antibodies against LY6K as a diagnostic biomarker in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Biomarkers. (2012) 17:372–8. 10.3109/1354750X.2012.680609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ambatipudi S, Gerstung M, Pandey M, Samant T, Patil A, Kane S, et al. Genome-wide expression and copy number analysis identifies driver genes in gingivobuccal cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. (2012) 51:161–73. 10.1002/gcc.20940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsuda R, Enokida H, Chiyomaru T, Kikkawa N, Sugimoto T, Kawakami K, et al. LY6K is a novel molecular target in bladder cancer on basis of integrate genome-wide profiling. Br J Cancer. (2011) 104:376–86. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ishikawa N, Takano A, Yasui W, Inai K, Nishimura H, Ito H, et al. Cancer-testis antigen lymphocyte antigen 6 complex locus K is a serologic biomarker and a therapeutic target for lung and esophageal carcinomas. Cancer Res. (2007) 67:11601–11. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reiter RE, Gu Z, Watabe T, Thomas G, Szigeti K, Davis E, et al. Prostate stem cell antigen:a cell surface marker overexpressed in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1998) 95:1735–40. 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ono H, Sakamoto H, Yoshida T, Saeki N. Prostate stem cell antigen is expressed in normal and malignant human brain tissues. Oncol Lett. (2018) 15:3081–4. 10.3892/ol.2017.7632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang LY, Wu JL, Qiu HB, Dong SS, Zhu YH, Lee VH, et al. PSCA acts as a tumor suppressor by facilitating the nuclear translocation of RB1CC1 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. (2016) 37:320–32. 10.1093/carcin/bgw010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang S, Wu S, Zhu H, Ding B, Cai Y, Ni J, et al. PSCA rs2294008 polymorphism contributes to the decreased risk for cervical cancer in a Chinese population. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:23465. 10.1038/srep23465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee IS, Pil Seo S, Sok Ha Y, Jeong P, Won Kang H, Tae Kim W, et al. Genetic variation of the PSCA gene (rs2294008) is not associated with the risk of prostate cancer. J Biomed Res. (2017) 31:226–31. 10.7555/JBR.31.20160072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Geng P, Li J, Wang N, Ou J, Xie G, Liu C, et al. PSCA rs2294008 Polymorphism with increased risk of cancer. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0136269. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Higashiyama M, Miyoshi Y, Kodama K, Yokouchi H, Takami K, Nishijima M, et al. p53-regulated GML gene expression in non-small cell lung cancer. a promising relationship to cisplatin chemosensitivity. Eur J Cancer. (2000) 36:489–95. 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00261-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loeuillet C, Deutsch S, Ciuffi A, Robyr D, Taffe P, Munoz M, et al. In vitro whole-genome analysis identifies a susceptibility locus for HIV-1. PLoS Biol. (2008) 6:e32. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cicala C, Arthos J, Martinelli E, Censoplano N, Cruz CC, Chung E, et al. R5 and X4 HIV envelopes induce distinct gene expression profiles in primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2006) 103:3746–51. 10.1073/pnas.0511237103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mar KB, Rinkenberger NR, Boys IN, Eitson JL, McDougal MB, Richardson RB, et al. LY6E mediates an evolutionarily conserved enhancement of virus infection by targeting a late entry step. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:3603. 10.1038/s41467-018-06000-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beigneux AP. GPIHBP1 and the processing of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Clin Lipidol. (2010) 5:575–82. 10.2217/clp.10.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beigneux AP, Weinstein MM, Davies BS, Gin P, Bensadoun A, Fong LG, et al. GPIHBP1 and lipolysis:an update. Curr Opin Lipidol. (2009) 20:211–6. 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32832ac026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yeom CJ, Zeng L, Goto Y, Morinibu A, Zhu Y, Shinomiya K, et al. LY6E:a conductor of malignant tumor growth through modulation of the PTEN/PI3K/Akt/HIF-1 axis. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:65837–48. 10.18632/oncotarget.11670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zheng L, Shi L, Zhou Z, Chen X, Wang L, Lu Z, et al. Placental expression of AChE, alpha7nAChR and NF-kappaB in patients with preeclampsia. Ginekol Pol. (2018) 89:249–55. 10.5603/GP.a2018.0043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wan C, Wu M, Zhang S, Chen Y, Lu C. Alpha7Nachr-mediated recruitment of PP1gamma promotes TRAF6/NF-kappaB cascade to facilitate the progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. (2018) 57:1626–39. 10.1002/mc.22885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baez-Pagan CA, Delgado-Velez M, Lasalde-Dominicci JA. Activation of the macrophage alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and control of inflammation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. (2015) 10:468–76. 10.1007/s11481-015-9601-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fei R, Zhang Y, Wang S, Xiang T, Chen W. Alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in tumor-associated macrophages inhibits colorectal cancer metastasis through the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Oncol Rep. (2017) 38:2619–28. 10.3892/or.2017.5935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang S, Hu Y. alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in lung cancer. Oncol Lett. (2018) 16:1375–82. 10.3892/ol.2018.8841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fu XW, Song PF, Spindel ER. Role of Lynx1 and related Ly6 proteins as modulators of cholinergic signaling in normal and neoplastic bronchial epithelium. Int Immunopharmacol. (2015) 29:93–8. 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Puddifoot CA, Wu M, Sung RJ, Joiner WJ. Ly6h regulates trafficking of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotine-induced potentiation of glutamatergic signaling. J Neurosci. (2015) 35:3420–30. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3630-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Asundi J, Crocker L, Tremayne J, Chang P, Sakanaka C, Tanguay J, et al. An antibody-drug conjugate directed against lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus E (LY6E) provides robust tumor killing in a wide range of solid tumor malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. (2015) 21:3252–62. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thomsen MS, Mikkelsen JD. The alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor complex: one, two or multiple drug targets? Curr Drug Targets. (2012) 13:707–20. 10.2174/138945012800399035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]