Abstract

Background

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type of lung cancer with a poor prognosis. We previously found that protein disulfide isomerase family 6 (PDIA6) is upregulated in lung squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). This study aimed to elucidate the clinical relevance, biological functions, and molecular mechanisms of PDIA6 in NSCLC.

Methods

The expression of PDIA6 in NSCLC was assessed using the TCGA database, western blotting, and immunohistochemistry. Correlations of PDIA6 expression with clinicopathological and survival features were evaluated. The functions of PDIA6 in regulating NSCLC cell growth, apoptosis, and autophagy were investigated using gain-and loss-of-function strategies in vitro or in vivo. The underlying molecular mechanisms of PDIA6 function were examined by human phospho-kinase array and co-immunoprecipitation.

Findings

PDIA6 expression was upregulated in NSCLC compared with adjacent normal tissues, and the higher PDIA6 expression was correlated with poor prognosis. PDIA6 knockdown decreased NSCLC cell proliferation and increased cisplatin-induced intrinsic apoptosis, while PDIA6 overexpression had the opposite effects. In addition, PDIA6 regulated cisplatin-induced autophagy, and this contributed to PDIA6-mediated apoptosis in NSCLC cells. Mechanistically, PDIA6 reduced the phosphorylation levels of JNK and c-Jun. Moreover, PDIA6 interacted with MAP4K1 and inhibited its phosphorylation, ultimately inhibiting the JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway.

Interpretation

PDIA6 is overexpressed in NSCLC and inhibits cisplatin-induced NSCLC cell apoptosis and autophagy via the MAP4K1/JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway, suggesting that PDIA6 may serve as a biomarker and therapeutic target for NSCLC patients.

Fund

National Natural Science Foundation of China and Institutions of higher learning of innovation team from Liaoning province.

Keywords: PDIA6, Apoptosis, Autophagy, MAP4K1, NSCLC

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Previous reports have implicated PDIA6 in tumorigenesis. Our previous proteomic study also showed that PDIA6 is highly expressed in LSCC. However, the functions and molecular mechanisms of PDIA6 regarding apoptosis and autophagy have not been thoroughly assessed, especially in NSCLC.

The value of this study

This study aimed to elucidate the clinical relevance, biological functions, and molecular mechanisms of PDIA6 in NSCLC. We found that PDIA6 expression was elevated in NSCLC, and associated with a poor prognosis of NSCLC patients. Moreover, PDIA6 suppressed cisplatin-induced NSCLC cell apoptosis and autophagy through interacting with MAP4K1 to inhibit the JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway.

Implications of all the available evidence

These results indicate that PDIA6 has an oncogenic role and may be a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in NSCLC.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common forms of cancer, affecting both men and women worldwide [1]. Histologically, it can be divided into non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Approximately 85% of lung cancer cases are diagnosed as NSCLC, and these can be further subdivided into two main subtypes: adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma [2]. Despite numerous advancements in early detection and treatment strategies over the past few decades, the five-year survival rate remains <20% [1]. Thus, additional studies on the pathogenesis and molecular mechanisms of NSCLC will be vital to identify novel biomarkers for early detection and prediction of treatment responses and prognosis, as well as to uncover novel therapeutic targets.

Apoptosis or programmed cell death is often induced by chemotherapy agents and plays a critical role in clinical treatment of human cancers, which is regulated by many apoptosis-related genes and signaling pathways [3,4]. In addition, autophagy, a cell mechanism by which cellular components are subjected to orderly degradation and recycling, has recently been suggested as a therapeutic target in cancer treatment and may be either cytoprotective [[5], [6], [7]] or cytotoxic during chemotherapy [[8], [9], [10]]. Interestingly, apoptosis and autophagy are closely linked and may both positively and negatively regulate each other [11]. For example, autophagy may regulate apoptosis via Atg5 and Atg12 which are important in autophagy pathway and reportedly play a key role in initiating apoptosis in response to diverse stress signals [12,13]. Other recent studies have revealed that apoptotic proteins, such as caspase-8 and caspase-9, are involved in the regulation of autophagy by targeting autophagy proteins [14,15].

In our previous study, we identified differentially expressed proteins between LSCC and adjacent normal tissues using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE) followed by mass spectrometry (MS) analysis [16]. Among these proteins, we focused on protein disulfide isomerase family 6 (PDIA6) for further analysis. PDIA6 is a member of the protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) family, which is mainly localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and functions as an oxidoreductase to catalyze disulfide bond formation and as a chaperone to assist in protein folding and inhibit aggregation of unfolded substrates [17,18]. Recent studies have reported that PDIA6 is upregulated in human cancers, such as liver cancer [19] and bladder cancer [20], and that knockdown of PDIA6 expression reduces bladder cancer cell proliferation and invasion [20]. Furthermore, PDIA6 mediates tumor cell resistance to cisplatin-induced apoptosis in lung adenocarcinoma [21]. However, the roles and molecular mechanisms of PDIA6 in NSCLC development and progression have yet to be elucidated.

In this study, we first evaluated PDIA6 expression in NSCLC samples and adjacent normal tissues, and examined the association of PDIA6 expression with clinicopathological and survival data from NSCLC patients. Next, we assessed the effects of PDIA6 knockdown and overexpression on NSCLC cell growth, apoptosis, and autophagy, as well as the underlying molecular events. We hypothesized that PDIA6 functions as an oncogene in NSCLC and may be valuable as a future therapeutic target or biomarker for NSCLC patients.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Clinical specimens

We obtained the tissue specimens from patients who received surgical resection of primary NSCLC in The First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University (Dalian, China). The use of the clinical specimens was approved by the Ethics Committee of Dalian Medical University, and all patients provided written informed consent. Furthermore, we also obtained primary human NSCLC tissue microarrays from Outdo Biotech (Shanghai, China), defined as cohort 1 (169 NSCLC and 164 corresponding adjacent normal samples) and cohort 2 (94 paired NSCLC and corresponding adjacent normal samples). Overall survival information and clinicopathological features of patients in cohort 1 were used for clinicopathological analysis.

2.2. Cell culture

Human lung cancer A549, NCI-H1299, NCI-H157, NCI-H460, NCI-H520, NCI-H446, and NCI-H358 cell lines, as well as two normal lung cell lines (HFL1 and HBE) and HEK293T were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA, USA). Lung adenocarcinoma Anip973 cell line was kindly provided by the Tumor Research Institute of Harbin Medical University. Lung adenocarcinoma SPC-A-1 cell line was purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Committee Typical Culture Collection Cell Bank (Shanghai, China). These lung cell lines were grown in RPMI-1640 media (Gibco), while HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco), in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. All media were added with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 100 μg/ml of streptomycin and 100 U/ml of penicillin (Beyotime, Shanghai, China).

2.3. Western blotting

Total cellular protein from cell lines or lung cancer tissues was extracted using the radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) with protease inhibitors for 30 min at 4 °C, and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C to collect the supernatants. The concentrations of these protein samples were measured using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Protein samples (30 μg for each lane) were separated in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). After blocking with 5% non-fat milk, membranes were incubated with indicated primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. On the next day, the membranes were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with corresponding anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody-conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP). The protein bands were visualized using western bright ECL kit (Advansta, Menlo Park, CA, USA) followed by ChemiDoc™ XRS+ system (Bio-Rad, USA). Antibodies used are listed in Table S1.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The human NSCLC tissue microarrays and xenograft tumor tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through an ethanol series, followed by microwave in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) to repair antigens and treatment with 3% hydrogen peroxide to inhibit endogenous peroxide activities. These tissue microarrays and sections were then blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 20 min at room temperature, and treated with antibody against PDIA6 (1:100; 18233–1-AP; RRID: AB_10805765), Ki-67 (1:800; 27309–1-AP; RRID: AB_2756525), MAP4K1 (1:100; bs-4134R; RRID: AB_11120767), or phospho-MAP4K1 (1:100; bs-5494R; RRID: AB_11093913) at 4 °C overnight. After washing, tissue microarrays and sections were incubated with the pv-9000 kit (ZSGB-Bio, Beijing, China), visualized with 3,3-diaminobenzidine solution (ZSGB-Bio) treatment and counterstained with hematoxylin. The percentage (%) of positively stained cells was classified as 1 (0%–25%), 2 (26%–50%), 3 (51%–75%), or 4 (76%–100%), while the staining intensity was classified as 0 (negative), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), or 3 (strong). We then multiplied these two scores to reach a staining index. The staining index <6 was defined as low PDIA6 expression, while the staining index ≥6 as high PDIA6 expression.

2.5. Stable cell line construction and transient knockdown

To establish stable cell lines with PDIA6 knockdown or overexpression, vectors containing short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequences against PDIA6 (pLKO.1-PDIA6-shRNA1 and pLKO.1-PDIA6-shRNA2) were generated by cloning the shRNAs into pLKO.1 vector, while human pGMLV-PA6-PDIA6 and control vectors were obtained from Genomeditech (Shanghai, China). HEK293T cells were then co-transfected by PDIA6 shRNA vectors or pGMLV-PA6-PDIA6 vector together with packaging plasmids (psPAX2 and pMD2G), respectively. The viral supernatants were collected at 48–72 h after transfection. PDIA6 shRNA lentivirus were used to infect NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells, while PDIA6 overexpression lentivirus infected A549 cells. After 24 h, cells were fed with 5 μg/ml puromycin-containing media to establish stable cell lines. The shRNA sequences are listed in Table S2.

To transiently knock down the expression of Atg5, JNK or MAP4K1, siRNA sequences targeting Atg5 [22], JNK, or MAP4K1, and negative control scramble sequence were designed and purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells were transiently transfected with these siRNA duplexes using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the kit instructions. The siRNA sequences are listed in Table S3.

2.6. Animal models

Male BALB/c nude mice (6 weeks old) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology (Beijing, China). 2 × 106 NCI-H520 control cells and PDIA6 knockdown cells were inoculated subcutaneously into the left and right armpits of mice (n = 7), respectively. The mice were then kept for 30 days. The tumor volume was monitored every 5 days with calipers, and was calculated with the following formula: volume = 0.5 × length × width2. After the experiment was over, the mice were sacrificed and xenograft tumors were resected, measured and photographed. Lastly, xenograft tumors were fixed and embedded in paraffin, followed by IHC with anti-PDIA6, Ki-67, MAP4K1, and phospho-MAP4K1 antibodies. The animal study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Dalian Medical University. The animal experiments were strictly performed in accordance with the animal care guidelines of Dalian medical university.

2.7. Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) double staining

After different treatments, both floating and trypsin-detached cells grown on 6-well plates were collected and washed with cold 1 × PBS. The cell pellets were then resuspended with binding buffer, and stained with Annexin V and PI (KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) according to the kit protocols. The number of apoptotic cells was analyzed by using FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, US).

2.8. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

NCI-H520/Anip973 control cells or PDIA6 knockdown cells were plated into 6-well plates to grow overnight, and then incubated with 16 μM cisplatin for additional 24 h. After trypsin digestion and collection by centrifugation, cells were fixed in ice-cold 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C overnight and further fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) at 4 °C for 2 h. Then, cells were dehydrated in series of ethanol solutions from 50 to 100%, and subsequently embedded in Epon812 epoxyresin. Ultrathin sections (60–70 nm) were cut from the blocks by using a microtome, and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Finally, sections were reviewed under a TEM (JEM-2000EX, JEOL, Japan).

2.9. Acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EB) double staining

Cell morphology of apoptosis was also visualized using the AO/EB dual staining (KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). NCI-H520/Anip973 control cells or PDIA6 knockdown cells were plated onto coverslips in 6-well plates to grow overnight. After pretreatment with or without 20 μM Z-VAD-FMK for 2 h, cells were incubated with 16 μM cisplatin for another 24 h. Then, cells were washed with 1 × PBS for three times, and infiltrated with the mixture of AO and EB solutions, followed by observation with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

2.10. Confocol microscope

GFP-tagged LC3 vector was purchased from Addgene. mRFP-GFP-tagged LC3 vector was kindly provided by Tomatsu Yoshimori (Osaka university, Osaka, Japan) [23]. NCI-H520/Anip973 control cells and PDIA6 knockdown cells were transiently transfected with GFP-LC3 vector or mRFP-GFP-LC3 vector using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) according to the kit instructions. After 24 h of transfection, cells were incubated with 16 μM cisplatin for another 24 h. The images were then randomly acquired using confocal microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). In GFP-LC3 assay, the average number of LC3 puncta of per cell was calculated. For mRFP-GFP-LC3 system, the average number of yellow dots (autophagosomes) or red-only dots (autolysosomes) in the merged images of per cell was quantified.

2.11. Human phospho-kinase array

The human phospho-kinase microarrays were obtained from R&D Systems (#ARY003; Minneapolis, MN, USA), and the assay were conducted according to manufacturer's protocols. Briefly, cellular protein samples from NCI-H520 control cells and PDIA6 knockdown cells (600 μg protein of each) were incubated with the microarrays at 4 °C overnight. After mixture with biotin-labeled antibodies for 2 h, microarrays were incubated with HRP-streptavidin for 30 min at room temperature, and then detected using western bright ECL kit (Advansta, Menlo Park, CA, USA). Density was scanned with HLImage software to quantify the data.

2.12. Luciferase reporter assay

AP-1 luciferase reporter (pAP-1-Luc), containing multiple AP-1 binding sites, was purchased from Genomeditech (Shanghai, China) to assess the activity of MAPK/JNK signaling pathway. A549 cells were co-transfected with pGMLV-PA6-PDIA6 (800 ng) or control vector (800 ng) together with pAP-1-Luc (200 ng) or pGM-Luc control reporter (200 ng), as well as pRL-TK Renilla reporter (8 ng) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) according to the kit instructions. After 48 h of transfection, total cellular protein was lysed, and the luciferase activities (Firefly and Renilla) were detected using the Dual-Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

2.13. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

The co-immunoprecipitation assay was conducted using a co-immunoprecipitation kit (#26149; Pierce; Rockford, IL, USA) according to the kit's protocols. In brief, 500 μg of NCI-H520 cell lysates for each sample was pre-cleared using a control agarose resin and then incubated with the column containing 5 μg antibody against PDIA6 (#18233–1-AP; RRID: AB_10805765) or IgG (#2729; RRID: AB_1031062) at 4 °C overnight. After washing to remove non-specific binding, the co-immunoprecipitated proteins were then eluted and analyzed by western blotting with the antibody for PDIA6 (#sc-374494; RRID: AB_10989559) or MAP4K1 (#bs-4134R; RRID: AB_11120767). The input was used as positive control, while IgG was used as negative control.

2.14. Mass spectrometry (MS)

The co-immunoprecipitated proteins were collected from the resin and separated through SDS-PAGE gels. After that, the gels were subjected to silver staining with a kit from Beyotime (#P0017S; Shanghai, China) according to the kit's instructions. The differential bands specific to PDIA6 were in-gel digested with trypsin followed by the MS analysis using LTQ XL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The IgG was used as negative control.

2.15. Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analyzed by using either SPSS 21.0 or GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. All quantitative results were presented as mean ± SD. Statistical differences were analyzed with two-tailed Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA. The association between PDIA6 expression and various clinicopathological features was evaluated using the χ2 test. The association of PDIA6 expression with overall survival was plotted by using the Kaplan-Meier curves, and the log-rank test was used to compare the significant differences. The univariate and multivariate analyses were performed by using the Cox proportional hazard model. P value <0.05 was recognized to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. PDIA6 is elevated in NSCLC tissues and cell lines

In our previous study, we identified proteins which were differentially expressed between LSCC and adjacent normal tissues using 2D-DIGE and MS analyses. PDIA6 was one of the upregulated proteins identified in LSCC tissues and was chosen for further analysis [16]. As shown in Fig. S1a, the mass signal for PDIA6 was a single peak. In addition, the mascot score was 62 (Fig. S1b) and the amino acid residues shown in red aligned with PDIA6 (Fig. S1c), collectively indicating that the MS results were reliable.

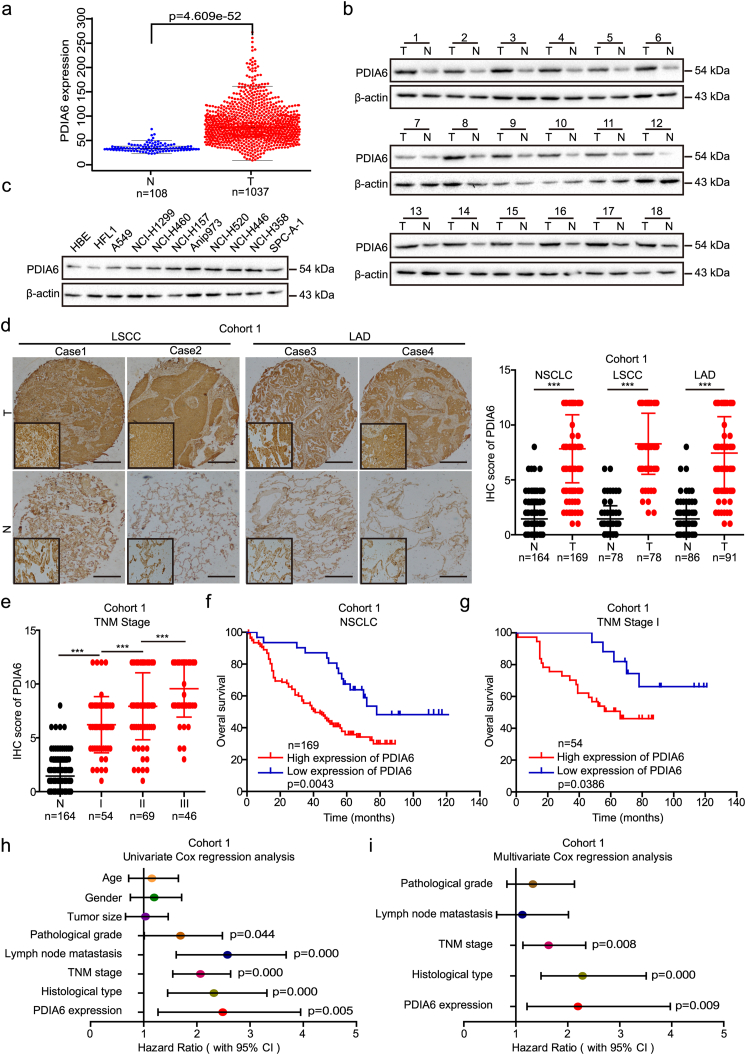

In the current study, we assessed PDIA6 expression levels in lung cancer by analyzing The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset and found that PDIA6 mRNA levels were significantly upregulated in lung cancer tissues (p = 4.609e-52 using the Wilcoxon test; Fig. 1a). Further analysis showed that PDIA6 protein levels were also higher in NSCLC tissues (n = 18) than in paired adjacent normal tissues and in nine NSCLC cell lines than in two normal lung cell lines, as measured by western blotting (Fig. 1b and c). In agreement with these results, immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of two cohorts of NSCLC tissue microarrays showed strongly positive PDIA6 staining in both lung adenocarcinoma (LAD) and LSCC, but weakly positive or negative PDIA6 staining in adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 1d and Fig. S1d). Scoring of the IHC staining further confirmed that PDIA6 was highly expressed in both LAD and LSCC samples compared with adjacent lung tissues (Fig. 1d and Fig. S1d). Importantly, the PDIA6 IHC score was also elevated in stage I tumors versus normal tissues, and showed a gradual increase as the tumor stage progressed (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

PDIA6 expression is elevated in NSCLC, and correlates with poor prognosis. (a) Expression of PDIA6 mRNA in lung cancer (T) and normal tissues (N) was analyzed by using TCGA database (p = 4.609e-52 by Wilcoxon test). (b, c) Western blotting analysis of the PDIA6 protein levels in 18 paired NSCLC tissues (T) and matched adjacent normal tissues (N) (b), as well as in two normal lung cell lines (HBE and HFL1) and nine NSCLC cell lines (c). (d) Representative images (left) and IHC score (right) of PDIA6 expression in LSCC, LAD, and adjacent normal tissues (N) in cohort 1 tissue microarrays, as determined by IHC staining. Original magnification, 40× (outside) or 400× (inset). Scale bar = 50 μm. Data is presented as the mean ± SD (***p < 0.001 by Student's t-tests). (e) IHC score of PDIA6 expression in stage I (I), stage II (II), stage III (III), and normal tissues (N) of cohort 1. Data is displayed with the mean ± SD (***p < 0.001 by Student's t-tests). (f, g) The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of overall survival for NSCLC patients (f) or patients with stage I (g) in cohort 1 according to PDIA6 expression levels (p = 0.0043 in NSCLC, p = 0.0386 in stage I of NSCLC, log-rank test). (h, i) Univariate (h) and multivariate (i) Cox regression analyses of the correlation of overall survival with various clinicopathological parameters as well as PDIA6 expression in cohort 1. 95% CIs and Hazard ratios are shown for each variable.

3.2. PDIA6 expression correlates with poor NSCLC prognosis

To elucidate the clinical relevance of PDIA6, we tested the potential association between PDIA6 expression and clinicopathological features in 169 NSCLC patients from cohort 1. As shown in Table 1, PDIA6 expression significantly correlated with TNM stage (p = 0.005), histological type (p = 0.034), and lymph node metastasis (p = 0.019), but not with gender, age, tumor size, or pathological grade. We then assessed the relationship between PDIA6 expression level and prognosis in NSCLC patients by Kaplan-Meier analysis. NSCLC patients with high PDIA6 expression levels had significantly reduced overall survival time than those with low PDIA6 expression levels (p = 0.0043, log-rank test, Fig. 1f). Interestingly, the association between high PDIA6 expression level and poor prognosis was only observed in LAD (p = 0.0002, log-rank test, Fig. S1e), and was not observed in LSCC (p = 0.1853, log-rank test, Fig. S1f). Consistent results were obtained when correlating PDIA6 mRNA expression with survival of LAD and LSCC patients using the Kaplan-Meier plotter database (www.kmplot.com) [24], and showed that higher expression of PDIA6 mRNA predicted poor overall survival in patients with LAD (p = 0.028, log-rank test, Fig. S1g). To evaluate the utility of PDIA6 as a biomarker of early NSCLC, Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed on the NSCLC patients with stage I in cohort 1. This analysis revealed that high PDIA6 expression markedly correlated with shorter overall survival of stage I patients (p = 0.0386, log-rank test, Fig. 1g).

Table 1.

Correlation of PDIA6 expression with clinicopathological features from 169 NSCLC patients.

| Clinicopathological factor | Number of cases | PDIA6a |

χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High expression | Low expression | ||||

| Age | |||||

| <60 | 55 | 48 | 7 | 1.717 | 0.190 |

| ≥60 | 114 | 90 | 24 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 121 | 103 | 18 | 3.419 | 0.064 |

| Female | 48 | 35 | 13 | ||

| Tumor size | |||||

| <4 cm | 61 | 47 | 14 | 1.353 | 0.245 |

| ≥4 cm | 108 | 91 | 17 | ||

| Pathological grading | |||||

| I | 21 | 17 | 4 | 0.170 | 0.919 |

| II | 134 | 109 | 25 | ||

| III | 14 | 12 | 2 | ||

| Histological type | |||||

| LSCC | 78 | 69 | 9 | 4.478 | 0.034b |

| LAD | 91 | 69 | 22 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | |||||

| Positive | 92 | 81 | 11 | 5.499 | 0.019b |

| Negative | 77 | 57 | 20 | ||

| TNM stage | |||||

| I | 54 | 37 | 17 | 10.78 | 0.005b |

| II | 69 | 58 | 11 | ||

| III | 46 | 43 | 3 | ||

Data are shown as number of cases.

Significant difference. The two tailed Pearson χ 2 test was employed to assess the correlation of PDIA6 expression with clinicalpathological factors. p value <0.05 was recognized as to be statistically significant.

Next, we assessed the prognostic value of PDIA6 by univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses in 169 NSCLC patients from cohort 1. Univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that PDIA6 expression, as well as TNM stage, pathological grade, lymph node metastasis, and histological type, were all significant predictors of overall survival in NSCLC patients (p = 0.005, 0.000, 0.044, 0.000, 0.000, respectively, Fig. 1h; Table S4). Importantly, PDIA6 expression was also an independent predictor of overall survival in NSCLC patients as shown by multivariate analysis [hazard ratio (HR) = 2.197, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.214–3.975, p = 0.009, Fig. 1i; Table S4].

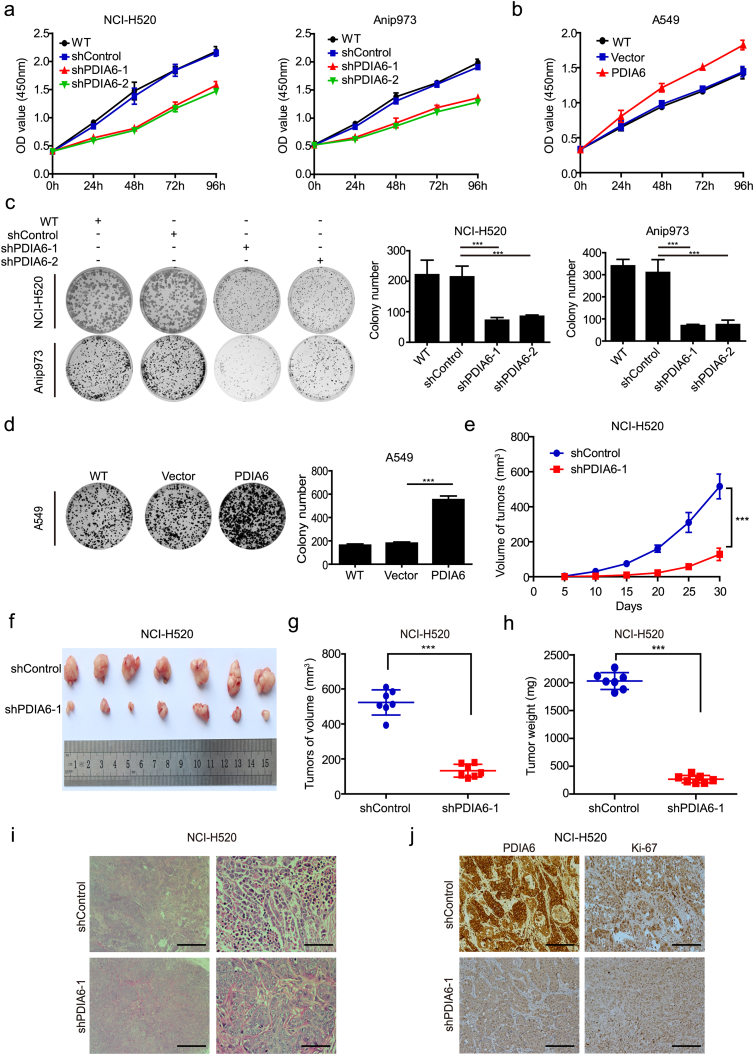

3.3. PDIA6 promotes NSCLC cell proliferation

In order to investigate the role of PDIA6 in NSCLC cell malignant phenotypes, we used a lentiviruses-mediated strategy to establish cell lines stably expressing or knocking-down PDIA6. We confirmed that small hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) targeting PDIA6 noticeably reduced PDIA6 expression in NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells compared with the negative control shRNA (Fig. S2a), whereas A549 cells infected with a PDIA6 expressing lentivirus showed upregulated PDIA6 expression (Fig. S2b). After that, we assessed the effect of PDIA6 on NSCLC cell viability using the CCK-8 assay. The results showed that cell viability was decreased in NSCLC cells following PDIA6 knockdown, but increased in A549 cells overexpressing PDIA6, when compared to the corresponding control groups (Fig. 2a and b). Similar results were obtained in a colony formation assay (Fig. 2c and d). These findings indicate that PDIA6 functions as an oncogene to promote NSCLC cell proliferation.

Fig. 2.

Effects of PDIA6 on NSCLC cell growth in vitro and in vivo. (a, b) CCK-8 assay analysis of the impact of PDIA6 knockdown (a) or overexpression (b) on NSCLC cell growth. WT: wild type, shControl: shRNA control, shPDIA6–1/2: shRNA-1/2 targeting PDIA6. Data is expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). (c, d) Colony formation assay showing the effects of PDIA6 knockdown (c) or overexpression (d) on NSCLC cell growth. Data is displayed with mean ± SD (n = 3, ***p < 0.001 by Student's t-tests). (e) The growth curves of xenograft tumors formed by NCI-H520 control cells (shControl) or PDIA6 knockdown cells (shPDIA6–1) after injection of them in nude mice. Tumor volume was measured every 5 days. Data is expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 7, ***p < 0.001 by Student's t-tests). (f) The tumors of two groups were isolated and compared. (g, h) The tumor volume (g) and weight (h) of two groups were measured and shown. Data is expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 7, ***p < 0.001 by Student's t-tests). (i) Representative images of HE staining in tumors from two groups. Scale bar = 100 μm (left) or Scale bar = 10 μm (right). (j) IHC was used to measure the protein levels of PDIA6 and Ki-67 in tumors from two groups. Scale bar = 20 μm.

3.4. PDIA6 knockdown inhibits NSCLC cell tumorigenesis in vivo

To further validate the oncogenic activity of PDIA6 in vivo, nude mice were subcutaneously injected with NCI-H520 control cells and NCI-H520 cells with PDIA6 knockdown. As shown in Fig. 2e, PDIA6 knockdown significantly suppressed xenograft tumor growth as determined by growth kinetics. Xenograft tumors formed by cells with PDIA6 knockdown were much smaller than those of control tumors (Fig. 2f and g). The mean tumor weight was also decreased in the PDIA6 knockdown group (Fig. 2h). Furthermore, HE staining of the control xenografts showed that tumor cells were scattered in clusters or nests with enlarged and a typical nuclei containing prominent nucleoli, whereas PDIA6 knockdown xenograft cells lacked these obvious tumor cell phenotypes (Fig. 2i). Low PDIA6 expression in the PDIA6 knockdown group was confirmed by IHC (Fig. 2j). In addition, the expression of Ki-67, a proliferation marker, was downregulated in PDIA6 knockdown tumors as compared with the control (Fig. 2j). Taken together, our in vitro and in vivo experiments suggest that PDIA6 is critical for the growth of NSCLC cells.

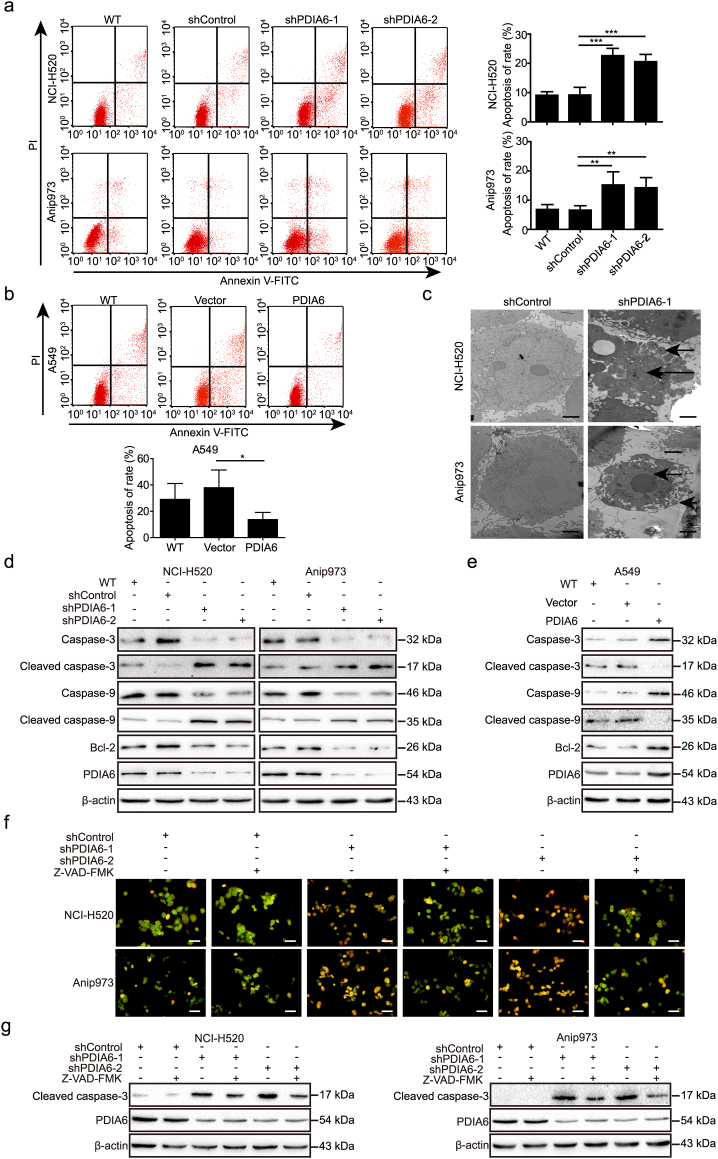

3.5. PDIA6 inhibits cisplatin-induced apoptosis in NSCLC cells

We then evaluated whether PDIA6 is involved in modulating the apoptotic response in NSCLC cells. We measured apoptosis using annexin V/PI double staining, and our results showed that PDIA6 knockdown increased the apoptotic rate of NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells compared to control shRNA (Fig. S3a). Conversely, PDIA6 overexpression showed a trend towards decreased apoptosis in A549 cells, although this did not reach statistical significance (Fig. S3b). To further study the role of PDIA6 in this process, we treated these stable cell lines with cisplatin which is commonly used as a chemotherapeutic in treating numerous cancers, including NSCLC, and induces tumor cell apoptosis [25,26]. Knockdown of PDIA6 significantly increased cisplain-induced apoptosis of NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells, while PDIA6 overexpression in A549 cells after cisplatin treatment decreased apoptosis (Fig. 3a and b). Consistently, DAPI staining also showed an increased apoptotic rate in PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells, and a decreased rate in PDIA6 overexpressing A549 cells, when compared with the corresponding control cells (Fig. S3c and d). Moreover, transmission electronic microscopic (TEM) data indicated that, upon cisplatin treatment, PDIA6 knockdown led to obvious ultrastructural changes in NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells, including disappearance of microvillus, chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation (Fig. 3c). Collectively, these data indicate that PDIA6 plays a role in suppressing cisplatin-induced apoptosis of NSCLC cells.

Fig. 3.

PDIA6 inhibits cisplatin-induced apoptosis through the intrinsic apoptosis pathway in NSCLC cells. (a, b) Apoptotic rate was measured using annexin V/PI double staining in PDIA6 knockdown (a) or overexpression (b) cells treated with 16 μM (NCI-H520 and Anip973) or 13 μM (A549) cisplatin for 24 h, respectively. Data is expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 by Student's t-tests). (c) TEM analysis of cell ultrastructural characteristics in NCI-H520/Anip973 control cells or PDIA6 knockdown cells treated with 16 μM cisplatin for 24 h. Chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation are indicated by arrows. Scale bar = 2 μm. (d, e) Western blotting analysis of apoptosis-related protein levels in cells as in (a) and (b). (f) NCI-H520/Anip973 control cells or PDIA6 knockdown cells, pretreated with or without 20 μM Z-VAD-FMK, were incubated with 16 μM cisplatin for 24 h. Cells were then stained with ethidium bromide and acridine orange followed observation under a fluorescence microscope. Scale bar = 50 μm. (g) Western blotting analysis of cleaved caspase-3 levels in cells as in (f).

3.6. PDIA6 inhibits caspase-dependent apoptosis via intrinsic apoptosis pathway

In order to determine which apoptotic signaling pathway is primarily involved in the role of PDIA6 in cisplatin-induced apoptosis, we assessed the expression levels of apoptosis-related proteins by western blotting following cisplatin treatment. We found that knockdown of PDIA6 noticeably decreased Bcl-2 expression and induced the activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 (Fig. 3d), two members of intrinsic apoptosis pathway [27]. In contrast, overexpression of PDIA6 in A549 cells had the opposite effect, leading to increased Bcl-2 expression and inhibited caspase activation (Fig. 3e). However, expression of caspase-8 and caspase-12, members of the extrinsic and ER stress-induced apoptotic pathways, respectively [28,29], did not noticeably change upon PDIA6 knockdown or overexpression (Fig. S3e and f), indicating that PDIA6 inhibits cisplatin-induced apoptosis through inhibition of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway rather than the extrinsic or ER stress-induced pathway.

To validate these findings, we treated PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells with Z-VAD-FMK, a pan-caspase inhibitor targeting caspase-3, and found that Z-VAD-FMK treatment noticeably suppressed PDIA6 knockdown-induced apoptosis as examined by ethidium bromide and acridine orange staining (Fig. 3f). Moreover, treatment with Z-VAD-FMK markedly decreased levels of cleaved caspase-3 in PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells (Fig. 3g), further implying that PDIA6 inhibits caspase-dependent apoptosis via the intrinsic apoptosis pathway.

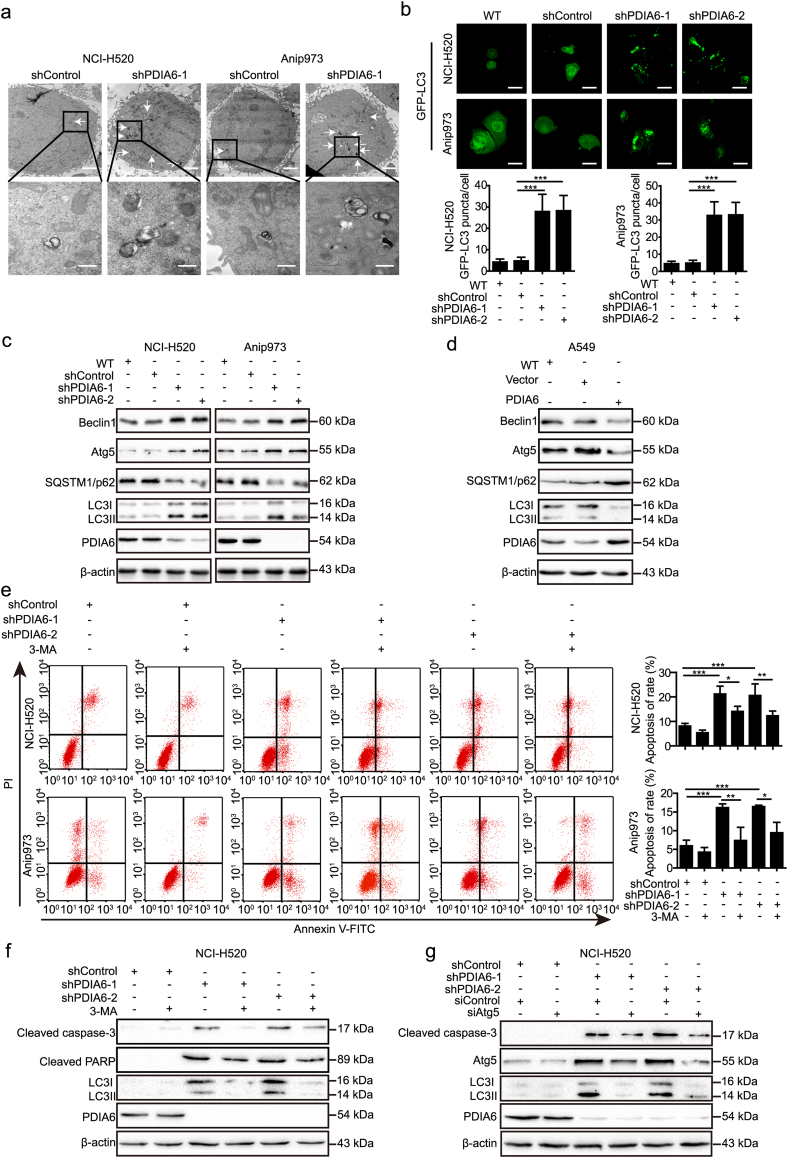

3.7. PDIA6 inhibits cisplatin-induced autophagy in NSCLC cells

Our TEM data revealed that autophagy levels were also increased in PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells compared to control cells after cisplatin treatment (Fig. 4a). To confirm this phenomenon, more experiments were conducted to examine autophagy following cisplatin treatment. Firstly, NSCLC cells were stained with monodansylcadaverine (MDC), a bright vacuolar signal used to label autophagosomes. The results showed that PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells had increased staining intensity, but this intensity was decreased in PDIA6 overexpressing A549 cells, when compared to control cells (Fig. S4a and b). Autophagosomes were also assessed by GFP-LC3 dot formation after transfection of a GFP-LC3 plasmid. Consistently, the number of GFP-LC3 dots in PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells was higher than that of control cells (Fig. 4b), collectively indicating that PDIA6 inhibits the formation of cisplatin-induced autophagosomes in NSCLC cells.

Fig. 4.

PDIA6 inhibits cisplatin-induced autophagy, which contributes to apoptosis suppression in NSCLC cells. (a) Autophagy was evaluated using TEM in NCI-H520/Anip973 control cells or PDIA6 knockdown cells treated with 16 μM cisplatin for 24 h. The arrows indicate autophagosomes or autolysosomes. Scale bar = 2 μm (upper) or Scale bar = 500 nm (lower). (b) NCI-H520/Anip973 control cells or PDIA6 knockdown cells transiently transfected with GFP-LC3II plasmid were treated with 16 μM cisplatin for 24 h. The distribution of GFP-LC3II was visualized by confocal microscopy (upper) and the average number of GFP-LC3 dots in per cell was quantified (lower). Data is expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3, ***p < 0.001 by Student's t-tests). Scale bar = 25 μm. (c, d) Western blot showing levels of autophagy-related proteins in PDIA6 knockdown (c) or overexpression (d) cells treated with 16 μM (NCI-H520 and Anip973) or 13 μM (A549) cisplatin for 24 h, respectively. (e) NCI-H520/Anip973 control cells or PDIA6 knockdown cells, pretreated with or without 5 mM 3-MA for 2 h, were incubated with 16 μM cisplatin for 24 h. Apoptotic rate was then measured using annexin V/PI double staining. Data is presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA). (f, g) NCI-H520 control cells or PDIA6 knockdown cells, pretreated with or without 5 mM 3-MA for 2 h (f), or transiently transfected with siRNA control (siControl) or siRNA targeting Atg5 (siAtg5) (g), were incubated with 16 μM cisplatin for 24 h. Western blotting was then performed to measure the indicated protein levels.

To better understand the effect of PDIA6 on the autophagic process, we utilized the mRFP-GFP-LC3 double fluorescence system. This revealed that the numbers of both yellow dots (autophagosomes) and red-only dots (autolysosomes) increased in PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells, relative to control cells (Fig. 5e and Fig. S5d). Detection of autophagy-related protein expression using western blotting yielded similar results. PDIA6 knockdown resulted in upregulated levels of LC3II, Beclin1, and Atg5, but reduced levels of SQSTM1/p62 in NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells (Fig. 4c), whereas PDIA6 overexpression had the opposite effects on these proteins in A549 cells (Fig. 4d). Thus, these data support that PDIA6 exhibits an inhibitory effect on cisplatin-induced autophagy in NSCLC cells.

Fig. 5.

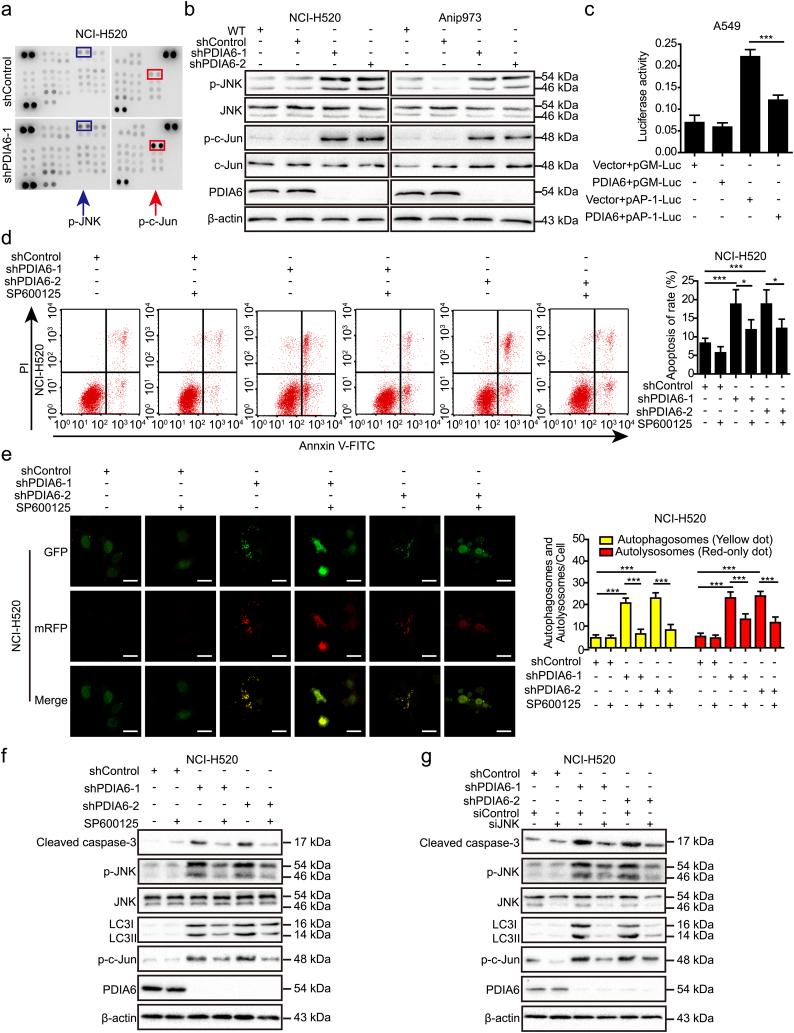

PDIA6 inhibits cisplatin-induced apoptosis and autophagy through JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway. (a) Human phospho-kinase array profile of differential phospho-proteins between NCI-H520 control cells and PDIA6 knockdown cells treated with 16 μM cisplatin for 24 h. Each phospho-protein is represented in duplicate. Red and blue boxes indicate noticeably altered c-Jun and JNK phosphorylation levels, respectively. (b) Western blotting analysis of the impact of PDIA6 knockdown on the activity of JNK and c-Jun in NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells treated with 16 μM cisplatin for 24 h. (c) pGMLV-PA6-PDIA6 or control vector together with pAP-1-Luc reporter or pGM-Luc control reporter were co-transfected to A549 cells with pRL-TK Renilla. After 24 h, cells were incubated with 13 μM cisplatin for another 24 h. Firefly luciferase activity was then detected and normalized to the Renilla luciferase activity. Data is expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3, ***p < 0.001 by Student's t-tests). (d) NCI-H520 control cells or PDIA6 knockdown cells, pretreated with or without 20 μM SP600125 for 2 h, were incubated with 16 μM cisplatin for 24 h. Apoptotic rate was then measured using annexin V/PI double staining. Data is expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3, *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA). (e) NCI-H520 control cells or PDIA6 knockdown cells transiently transfected with GFP-mRFP-LC3 plasmid were pretreated with or without 20 μM SP600125 for 2 h. After that, cells were incubated with 16 μM cisplatin for 24 h. Images were then acquired by confocal microscopy (left) and the average number of yellow dots (autophagosomes) or red-only dots (autolysosomes) in the merged images of per cell was quantified (right). Data is expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3, ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA). Scale bar = 25 μm. (f, g) NCI-H520 control cells or PDIA6 knockdown cells, pretreated with or without 20 μM SP600125 for 2 h (f), or transiently transfected with the siRNA control (siControl) or siRNA targeting JNK (siJNK) (g), were incubated with 16 μM cisplatin for 24 h. Western blotting was then performed to measure the expression of cleaved caspase-3, total JNK, phospho-JNK (p-JNK), phospho-c-Jun (p-c-Jun), and LC3I/II. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.8. PDIA6-mediated autophagy contributes to apoptosis in NSCLC cells

To investigate whether PDIA6-mediated autophagy is related to cell death in NSCLC cells, we treated PDIA6 knockdown cells with an autophagy inhibitor, 3-MA. Similar to the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK, 3-MA treatment alleviated PDIA6 knockdown-mediated inhibition of cell viability in NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells (Fig. S4c), suggesting that PDIA6 knockdown activates cytotoxic autophagy in NSCLC cells and autophagy is at least partially responsible for PDIA6 knockdown-mediated growth inhibition. In addition, annexin V/PI double staining showed that 3-MA-mediated autophagy inhibition also led to a decrease in PDIA6 knockdown-induced apoptosis in NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells (Fig. 4e). Consistently, the high levels of apoptosis-related proteins, including cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3, in PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells were downregulated following 3-MA treatment as measured by western blotting (Fig. 4f and Fig. S4d). In addition, downregulation of cleaved caspase-3 in PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells was also observed following siRNA-mediated Atg5 depletion (Fig. 4g and Fig. S4e). Our results indicate that inhibition of autophagy attenuates PDIA6 knockdown-induced apoptosis in NSCLC cells.

3.9. PDIA6 inhibits cisplatin-induced apoptosis and autophagy through JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway

Next, we conducted a human phospho-kinase array to identify potential signaling pathways involved in PDIA6-mediated inhibition of cisplatin-induced apoptosis and autophagy. We found that the levels of JNK phosphorylation at threonine 183 and tyrosine 185, and c-Jun phosphorylation at serine 63, but not AKT or mTOR phosphorylation, were upregulated in PDIA6 knockdown NCI-H520 cells compared with control cells (Fig. 5a). The results were validated by western blotting, which showed that PDIA6 knockdown increased JNK and c-Jun phosphorylation but not total protein levels in NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells (Fig. 5b), whereas PDIA6 overexpression reduced JNK and c-Jun phosphorylation (Fig. S5a). Similar changes in c-Jun phosphorylation upon PDIA6 knockdown were also observed by immunofluorescence staining (Fig. S5b). To further assess the effect of PDIA6 on JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway, PDIA6 cDNA plasmid was co-transfected with an AP-1 luciferase reporter (pAP-1-Luc), and results showed that luciferase activity was decreased upon PDIA6 overexpression (Fig. 5c). These data indicate that PDIA6 functions in the regulation of JNK/c-Jun signaling activity.

To determine whether PDIA6 knockdown-induced apoptosis and autophagy were dependent on JNK signaling pathway activation, we treated cells with the JNK-specific inhibitor SP600125 and found that SP600125 treatment significantly prevented PDIA6 knockdown-mediated apoptosis as measured by annexin V/PI double staining (Fig. 5d and Fig. S5c). Similarly, we found that SP600125 treatment significantly inhibited PDIA6 knockdown-induced autophagy, as determined using the mRFP-GFP-LC3 double fluorescence system (Fig. 5e and Fig. S5d). Western blotting data further showed that SP600125-mediated inhibition of JNK noticeably attenuated the levels of c-Jun phosphorylation, cleaved caspase-3, and LC3II in PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells (Fig. 5f and Fig. S5e). Similar changes were observed in these proteins when using siRNA to silence JNK (Fig. 5g and Fig. S5f). Collectively, these data illustrate that JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway is critical for PDIA6-mediated apoptosis and autophagy in NSCLC cells.

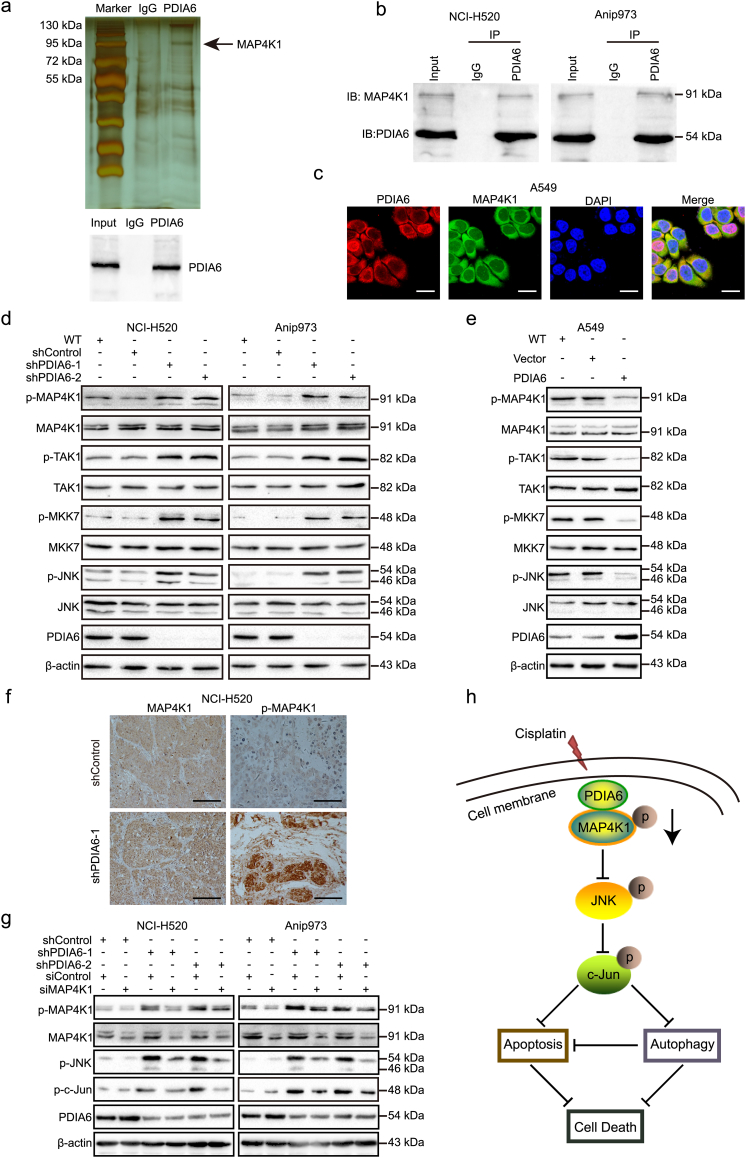

3.10. PDIA6 interacts with MAP4K1 to inhibit JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway

To further explore the underlying molecular mechanisms of PDIA6 in NSCLC cells, we identified PDIA6-associated proteins by co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP). As shown in Fig. 6a, we observed differential bands specific to PDIA6 in the silver stained SDS-PAGE gel as compared to IgG control. The presence of PDIA6 in the co-precipitated complexes was confirmed by western blotting of a parallel sample (Fig. 6a). Next, the differential protein bands were digested with trypsin and subjected to MS analysis. Among the candidate proteins, mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (MAP4K1) was chosen for further analysis because it is an activator of JNK signaling pathway [30] and stably interacted with PDIA6 as validated by western blotting in both NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, immunofluorescence staining of PDIA6 (red) and MAP4K1 (green) showed that the two proteins were co-localized in the cell cytoplasm upon cisplatin treatment (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

PDIA6 interacts with MAP4K1 to inhibit JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway. (a) PDIA6 binding proteins isolated by Co-IP from NCI-H520 cell lysate were visualized by silver staining (upper). The existence of PDIA6 in the co-precipitated complexes was confirmed by western blotting (lower). The black arrow indicates the PDIA6 specific binding band, which contains MAP4K1. IgG was employed as the negative control. (b) Western blotting showing the association of PDIA6 with MAP4K1 after Co-IP in NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells. (c) Confocal microscopy analysis of co-localization of PDIA6 (red) and MAP4K1 (green) in PDIA6 overexpression A549 cells after 24 h of treatment with 13 μM cisplatin. Blue DAPI staining was used to stain the cell nucleus. Scale bar = 25 μm. (d, e) Western blotting showing the levels of MAP4K1 pathway-related phospho-proteins in PDIA6 knockdown (d) or overexpression (e) cells treated with 16 μM (NCI-H520 and Anip973) or 13 μM (A549) cisplatin for 24 h, respectively. (f) Representative images of IHC against MAP4K1 and phospho-MAP4K1 (p-MAP4K1) as described in Fig. 2j. Scale bar = 20 μm. (g) NCI-H520/Anip973 control cells or PDIA6 knockdown cells transiently transfected with the siRNA control (siControl) or siRNA against MAP4K1 (siMAP4K1) were treated with 16 μM cisplatin for 24 h. Western blotting was used to assess the levels of phospho-MAP4K1 (p-MAP4K1), total MAP4K1, phospho-c-Jun (p-c-Jun), and phospho-JNK (p-JNK). (h) Proposed functional action of PDIA6 in regulating cisplatin-induced apoptosis and autophagy in NSCLC cells. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Next, we investigated whether PDIA6 could affect MAP4K1 expression and found that, upon cisplatin treatment, MAP4K1 total mRNA or protein levels were not noticeably changed when PDIA6 was knocked down or overexpressed (Fig. 6d and e and Fig. S6a). However, PDIA6 knockdown increased the levels of phosphorylated MAP4K1 in NCI-H520 and Anip973 cells after cisplatin treatment (Fig. 6d). Consistent results were also observed in xenograft tumors, in which phospho-MAP4K1, but not total MAP4K1, was upregulated in the PDIA6 knockdown group compared to controls (Fig. 6f). In addition, the levels of phospho-TAK1 and phospho-MKK7, which are downstream of MAP4K1, were much higher in PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells upon cisplatin treatment, whereas total TAK1 and MKK7 protein levels were unchanged (Fig. 6d). In agreement with these findings, PDIA6 overexpression had the opposite effect on MAP4K1, TAK1, and MKK7 phosphorylation (Fig. 6e). To confirm whether MAP4K1 is required for PDIA6 knockdown-induced JNK/c-Jun activation, we transfected PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells with MAP4K1 siRNA. Western blotting showed that depletion of MAP4K1 reduced JNK and c-Jun phosphorylation levels in PDIA6 knockdown cells upon cisplatin treatment (Fig. 6g). Collectively, these results indicate that MAP4K1 is involved in PDIA6-mediated inhibition of JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway.

4. Discussion

The PDI protein family consists of at least 21 members with a multidomain structure [31]. For example, PDIA1 and PDIA3 have four distinct domains, including two catalytically active a and a' domains, as well as two catalytically inactive b and b' domains, while PDIA6 lacks the b' domain [32]. At present, mounting evidences support that PDI family members are highly expressed in several cancers with poor clinical outcome and increased metastasis, invasion and chemoresistance [33]. Soma Samanta et al., reported that PDI, PDIA6, PDIR, ERp57, ERp72, and AGR3 are overexpressed in ovarian cancer, and associated with poor survival in ovarian cancer with the exception of PDIA6 [34]. PDIA3 and PDIA6 expression is suggested to be aggressiveness marker in primary ductal breast cancer [35]. PDIA3 also functions in inhibiting paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in ovarian cancer [36]. Additionally, recent studies found that ERp57 protects against apoptosis in autophagy-deficient cells [37]. Our previous study showed that PDIA6 is upregulated in LSCC tissues [16]. However, the molecular mechanisms by which PDIA6 regulates tumor cell apoptosis and autophagy has not been thoroughly assessed, especially in lung cancer.

Apoptosis, a representative form of programmed cell death, can be induced by chemotherapeutic drugs via several pathways, such as the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways [38] or ER stress [39]. Caspases, a family of cysteine-dependent and aspartate directed proteases, play a vital role in apoptotic signaling pathways [40]. For example, caspases-8 and caspases-9 are responsible for activation of the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways, respectively [27,28], while caspase-12 which resides in the ER, is activated by ER stress and involved in ER-induced apoptosis [29]. In the present study, we found that PDIA6 suppressed cisplatin-induced NSCLC cell apoptosis by inhibiting caspase-9 and caspase-3 activation. This is in contrast to a previous study which showed that knockdown of PDIA6 expression sensitizes cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cells to cisplatin-induced cell death through modulating a non-canonical cell death pathway [21]. Although apoptosis is a very common form of programmed cell death, recent studies have highlighted the role of additional forms of cell death, such as autophagy-induced cell death [41]. In this process, autophagy could act in concert with apoptotic signaling and induce cell death [42]. Our study revealed that PDIA6 inhibited cisplatin-induced autophagy in NSCLC cells, which contributed to PDIA6-mediated NSCLC cell growth and apoptosis. Thus, autophagy may function as upstream of apoptosis in our study.

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying PDIA6 regulated-apoptosis and autophagy induced by cisplatin, we used a human phospho-kinase array and observed that knockdown of PDIA6 in NSCLC cells induced JNK and c-Jun phosphorylation. Previous reports have shown that JNK (c-Jun NH 2-terminal kinase), a type of serine/threonine kinase belonging to the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family [43], has vital function in apoptosis [44,45] and autophagy, especially in autophagic cell death [[46], [47], [48]]. Current literature suggests that apoptosis and autophagy can be triggered by common upstream signals [11,49]. Indeed, various stimuli can activate JNK, leading to induction of both apoptosis and autophagy in human cancers [[50], [51], [52]]. Molecularly, activation of JNK induces Bcl-2 phosphorylation, which activates Beclin1-induced autophagy and caspase-3-mediated apoptosis [53,54]. Furthermore, downstream targets of JNK, such as the transcription factor c-Jun, can upregulate the expression levels of both autophagic and apoptotic genes [55,56]. Our data demonstrated that inhibition of JNK markedly suppressed both cisplatin-induced apoptosis and autophagy in PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells, indicating that the JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway is responsible at least in part for PDIA6 knockdown-induced apoptosis and autophagy.

MAP4K1, also referred to as human hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 (HPK1), is a member of the Ste20-related kinases family and is activated after tyrosine kinase induced phosphorylation [57]. Activated MAP4K1 will activate MAP3Ks, such as MEKK1, MLK3, and TAK1, which will then activate MKK4 or MKK7, ultimately leading to activation of the SAPK/JNK signaling pathway [30,58,59]. Here, we found that PDIA6 interacted with MAP4K1 and suppressed its phosphorylation after cisplatin treatment. Furthermore, MAP4K1 depletion resulted in decreased JNK and c-Jun activation in PDIA6 knockdown NSCLC cells after cisplatin treatment. Although PDIA6 wasn't found to directly interact with JNK, PDIA6 may mediate repression of JNK activation and c-Jun-dependent transcription in NSCLC cells via interaction with MAP4K1. To the best of our knowledge, our current data is the first to show that PDIA6 interacts with MAP4K1 to repress JNK activity after cisplatin treatment. Future studies will investigate how PDIA6 interaction with MAP4K1 changes MAP4K1 phosphorylation in NSCLC. In addition, studies have found that some PDI family proteins are involved in cisplatin resistance, including PDIA6 [21,60]. Therefore, interference with the PDIA6-MAP4K1 binding may contribute to reverse of cisplatin resistance, which is worth further study in the future.

In summary, our current study demonstrates that PDIA6 is upregulated in NSCLC, and correlates with poor prognosis for NSCLC patients. Moreover, PDIA6 functions as an oncogene that inhibits cisplatin-induced NSCLC cell apoptosis and autophagy via interacting with MAP4K1 to suppress the JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway. Fig. 6h illustrates a model of PDIA6-regulated NSCLC cell apoptosis and autophagy. Thus, PDIA6 may serve as a potential biomarker for NSCLC diagnosis and prediction of prognosis, and targeting PDIA6 may be a promising therapeutic strategy for NSCLC patients.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81470367, 81773122, and 21272032) and Institutions of higher learning of innovation team from Liaoning province (LT2014019). The funders did not have any role in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, writing of the report.

Declaration of interests

There are no conflicts of interest among the authors.

Authors' contributions

Yuxin Bai designed, performed most of the experiments with assisted experimental contributions of Xuan Liu and Xiaoyu Qi. Yuxin Bai and Xuefeng Liu participated in data analyses and wrote the manuscript. Xuefeng Liu, Yang Wang and Songshu Meng provided conceptual advice and innovative idea. Fang Peng and Xinming Chi participated in immunohistochemical experiment and evaluation. Xinbing Zhu, Liying Chen and Hailu Fu performed mouse experiments. Liyuan Zhang and Yang Song collected clinical specimens. Shimei Pei and Huimin Li provided bioinformatics analysis. Shujuan Shao and Tao Jiang supervised the work and reviewed this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.03.045.

Contributor Information

Tao Jiang, Email: jiangt69@163.com.

Shujuan Shao, Email: shaoshujuan2006@126.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oser M.G., Niederst M.J., Sequist L.V., Engelman J.A. Transformation from non-small-cell lung cancer to small-cell lung cancer: molecular drivers and cells of origin. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(4):e165–e172. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71180-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufmann S.H., Earnshaw W.C. Induction of apoptosis by cancer chemotherapy. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256(1):42–49. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fulda S., Debatin K.M. Targeting apoptosis pathways in cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2004;4(7):569–576. doi: 10.2174/1568009043332763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sui X., Chen R., Wang Z., Huang Z., Kong N., Zhang M. Autophagy and chemotherapy resistance: a promising therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J., Hou N., Faried A., Tsutsumi S., Kuwano H. Inhibition of autophagy augments 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy in human colon cancer in vitro and in vivo model. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(10):1900–1909. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katayama M., Kawaguchi T., Berger M.S., Pieper R.O. DNA damaging agent-induced autophagy produces a cytoprotective adenosine triphosphate surge in malignant glioma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14(3):548–558. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong H.Y., Guo X.L., Bu X.X., Zhang S.S., Ma N.N., Song J.R. Autophagic cell death induced by 5-FU in Bax or PUMA deficient human colon cancer cell. Cancer Lett. 2010;288(1):68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanzawa T., Kondo Y., Ito H., Kondo S., Germano I. Induction of autophagic cell death in malignant glioma cells by arsenic trioxide. Cancer Res. 2003;63(9):2103–2108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo W.J., Zhang Y.M., Zhang L., Huang B., Tao F.F., Chen W. Novel monofunctional platinum (II) complex mono-Pt induces apoptosis-independent autophagic cell death in human ovarian carcinoma cells, distinct from cisplatin. Autophagy. 2013;9(7):996–1008. doi: 10.4161/auto.24407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenberg-Lerner A., Bialik S., Simon H.U., Kimchi A. Life and death partners: apoptosis, autophagy and the cross-talk between them. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16(7):966–975. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubinstein A.D., Eisenstein M., Ber Y., Bialik S., Kimchi A. The autophagy protein Atg12 associates with antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members to promote mitochondrial apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2011;44(5):698–709. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yousefi S., Perozzo R., Schmid I., Ziemiecki A., Schaffner T., Scapozza L. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 switches autophagy to apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(10):1124–1132. doi: 10.1038/ncb1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oral O., Oz-Arslan D., Itah Z., Naghavi A., Deveci R., Karacali S. Cleavage of Atg3 protein by caspase-8 regulates autophagy during receptor-activated cell death. Apoptosis. 2012;17(8):810–820. doi: 10.1007/s10495-012-0735-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han J., Hou W., Goldstein L.A., Stolz D.B., Watkins S.C., Rabinowich H. A complex between Atg7 and Caspase-9: a novel mechanism of cross-regulation between autophagy and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(10):6485–6497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.536854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lihong H., Linlin G., Yiping G., Yang S., Xiaoyu Q., Zhuzhu G. Proteomics approaches for identification of tumor relevant protein targets in pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma by 2D-DIGE-MS. PLoS One. 2014;9(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Kikuchi M., Doi E., Tsujimoto I., Horibe T., Tsujimoto Y. Functional analysis of human P5, a protein disulfide isomerase homologue. J Biochem. 2002;132(3):451–455. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L., Wang X., Wang C.C. Protein disulfide-isomerase, a folding catalyst and a redox-regulated chaperone. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;83:305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Negroni L., Taouji S., Arma D., Pallares-Lupon N., Leong K., Beausang L.A. Integrative quantitative proteomics unveils proteostasis imbalance in human hepatocellular carcinoma developed on nonfibrotic livers. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13(12):3473–3483. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.043174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng H.P., Liu Q., Li Y., Li X.D., Zhu C.Y. The inhibitory effect of PDIA6 downregulation on bladder cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Oncol Res. 2017;25(4):587–593. doi: 10.3727/096504016X14761811155298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tufo G., Jones A.W., Wang Z., Hamelin J., Tajeddine N., Esposti D.D. The protein disulfide isomerases PDIA4 and PDIA6 mediate resistance to cisplatin-induced cell death in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21(5):685–695. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan H., Zhang Y., Luo Z., Li P., Liu L., Wang C. Autophagy mediates avian influenza H5N1 pseudotyped particle-induced lung inflammation through NF-kappaB and p38 MAPK signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;306(2):L183–L195. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00147.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimura S., Noda T., Yoshimori T. Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy. 2007;3(5):452–460. doi: 10.4161/auto.4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menyhart O., Nagy A., Gyorffy B. Determining consistent prognostic biomarkers of overall survival and vascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. R Soc Open Sci. 2018;5(12) doi: 10.1098/rsos.181006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pignon J.P., Tribodet H., Scagliotti G.V., Douillard J.Y., Shepherd F.A., Stephens R.J. Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE collaborative group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3552–3559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dasari S., Tchounwou P.B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740:364–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li P., Nijhawan D., Budihardjo I., Srinivasula S.M., Ahmad M., Alnemri E.S. Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell. 1997;91(4):479–489. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sprick M.R., Weigand M.A., Rieser E., Rauch C.T., Juo P., Blenis J. FADD/MORT1 and caspase-8 are recruited to TRAIL receptors 1 and 2 and are essential for apoptosis mediated by TRAIL receptor 2. Immunity. 2000;12(6):599–609. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakagawa T., Zhu H., Morishima N., Li E., Xu J., Yankner B.A. Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-beta. Nature. 2000;403(6765):98–103. doi: 10.1038/47513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu M.C., Qiu W.R., Wang X., Meyer C.F., Tan T.H. Human HPK1, a novel human hematopoietic progenitor kinase that activates the JNK/SAPK kinase cascade. Genes Dev. 1996;10(18):2251–2264. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galligan J.J., Petersen D.R. The human protein disulfide isomerase gene family. Hum Genomics. 2012;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kozlov G., Maattanen P., Thomas D.Y., Gehring K. A structural overview of the PDI family of proteins. FEBS J. 2010;277(19):3924–3936. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu S., Sankar S., Neamati N. Protein disulfide isomerase: a promising target for cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19(3):222–240. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samanta S., Tamura S., Dubeau L., Mhawech-Fauceglia P., Miyagi Y., Kato H. Expression of protein disulfide isomerase family members correlates with tumor progression and patient survival in ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(61):103543–103556. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramos F.S., Serino L.T., Carvalho C.M., Lima R.S., Urban C.A., Cavalli I.J. PDIA3 and PDIA6 gene expression as an aggressiveness marker in primary ductal breast cancer. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14(2):6960–6967. doi: 10.4238/2015.June.26.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao S., Wen Z., Liu S., Liu Y., Li X., Ge Y. MicroRNA-148a inhibits the proliferation and promotes the paclitaxel-induced apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells by targeting PDIA3. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12(3):3923–3929. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto E., Uchida T., Abe H., Taka H., Fujimura T., Komiya K. Increased expression of ERp57/GRP58 is protective against pancreatic beta cell death caused by autophagic failure. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2014;453(1):19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fulda S., Debatin K.M. Extrinsic versus intrinsic apoptosis pathways in anticancer chemotherapy. Oncogene. 2006;25(34):4798–4811. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breckenridge D.G., Germain M., Mathai J.P., Nguyen M., Shore G.C. Regulation of apoptosis by endoplasmic reticulum pathways. Oncogene. 2003;22(53):8608–8618. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salvesen G.S., Dixit V.M. Caspases: intracellular signaling by proteolysis. Cell. 1997;91(4):443–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galluzzi L., Vitale I., Aaronson S.A., Abrams J.M., Adam D., Agostinis P. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the nomenclature committee on cell death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25(3):486–541. doi: 10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scott R.C., Juhasz G., Neufeld T.P. Direct induction of autophagy by Atg1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptotic cell death. Curr Biol. 2007;17(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Derijard B., Hibi M., Wu I.H., Barrett T., Su B., Deng T. JNK1: a protein kinase stimulated by UV light and Ha-Ras that binds and phosphorylates the c-Jun activation domain. Cell. 1994;76(6):1025–1037. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu C., Minemoto Y., Zhang J., Liu J., Tang F., Bui T.N. JNK suppresses apoptosis via phosphorylation of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family protein BAD. Mol Cell. 2004;13(3):329–340. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lei K., Davis R.J. JNK phosphorylation of Bim-related members of the Bcl2 family induces Bax-dependent apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(5):2432–2437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438011100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimizu S., Konishi A., Nishida Y., Mizuta T., Nishina H., Yamamoto A. Involvement of JNK in the regulation of autophagic cell death. Oncogene. 2010;29(14):2070–2082. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trenti A., Grumati P., Cusinato F., Orso G., Bonaldo P., Trevisi L. Cardiac glycoside ouabain induces autophagic cell death in non-small cell lung cancer cells via a JNK-dependent decrease of Bcl-2. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;89(2):197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li D.D., Wang L.L., Deng R., Tang J., Shen Y., Guo J.F. The pivotal role of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-mediated Beclin 1 expression during anticancer agents-induced autophagy in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28(6):886–898. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu W., Wang X., Liu Z., Wang Y., Yin B., Yu P. SGK1 inhibition induces autophagy-dependent apoptosis via the mTOR-Foxo3a pathway. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(8):1139–1153. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lorin S., Borges A., Ribeiro Dos Santos L., Souquere S., Pierron G., Ryan K.M. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation is essential for DRAM-dependent induction of autophagy and apoptosis in 2-methoxyestradiol-treated Ewing sarcoma cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69(17):6924–6931. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao G.Y., Ma J., Lu P., Jiang X., Chang C. Ophiopogonin B induces the autophagy and apoptosis of colon cancer cells by activating JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:1208–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.06.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang J., Yao S. JNK-Bcl-2/Bcl-xL-Bax/Bak pathway mediates the crosstalk between matrine-induced autophagy and apoptosis via interplay with Beclin 1. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(10):25744–25758. doi: 10.3390/ijms161025744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y.X., Kong C.Z., Wang H.Q., Wang L.H., Xu C.L., Sun Y.H. Phosphorylation of Bcl-2 and activation of caspase-3 via the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway in ursolic acid-induced DU145 cells apoptosis. Biochimie. 2009;91(9):1173–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei Y., Pattingre S., Sinha S., Bassik M., Levine B. JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 regulates starvation-induced autophagy. Mol Cell. 2008;30(6):678–688. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun T., Li D., Wang L., Xia L., Ma J., Guan Z. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation is essential for up-regulation of LC3 during ceramide-induced autophagy in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. J Transl Med. 2011;9:161. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whitfield J., Neame S.J., Paquet L., Bernard O., Ham J. Dominant-negative c-Jun promotes neuronal survival by reducing BIM expression and inhibiting mitochondrial cytochrome c release. Neuron. 2001;29(3):629–643. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anafi M., Kiefer F., Gish G.D., Mbamalu G., Iscove N.N., Pawson T. SH2/SH3 adaptor proteins can link tyrosine kinases to a Ste20-related protein kinase, HPK1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(44):27804–27811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang W., Zhou G., Hu M.C., Yao Z., Tan T.H. Activation of the hematopoietic progenitor kinase-1 (HPK1)-dependent, stress-activated c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway by transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta)-activated kinase (TAK1), a kinase mediator of TGF beta signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(36):22771–22775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kiefer F., Tibbles L.A., Anafi M., Janssen A., Zanke B.W., Lassam N. HPK1, a hematopoietic protein kinase activating the SAPK/JNK pathway. EMBO J. 1996;15(24):7013–7025. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kullmann M., Kalayda G.V., Hellwig M., Kotz S., Hilger R.A., Metzger S. Assessing the contribution of the two protein disulfide isomerases PDIA1 and PDIA3 to cisplatin resistance. J Inorg Biochem. 2015;153:247–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2015.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material