Abstract

Background: Severe 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) deficiency is a heterogeneous metabolic disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. Pathogenic mutations in MTHFR gene have been associated with severe MTHFR deficiency. The clinical presentation of MTHFR deficiency is highly variable and associated with several neurological anomalies.

Methods: Direct whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed in all the five available individuals from the family, including the affected individual (III-7) using standard procedures.

Results: We observed a proband (III-7) with an abnormality in the cerebral white matter, apnoea, and microcephaly. WES analysis identified a novel homozygous non-sense mutation (c.154C>T; p.Arg52*) in MTHFR gene that segregated with the disease phenotype within the family.

Conclusion: We identified a novel non-sense mutation in MTHFR gene in a single Egyptian family with severe MTHFR deficiency. The present investigation is clinically important, as it adds to the growing list of MTHFR mutations, which might help in genetic counseling of families of affected children and proper genotype-phenotype correlation.

Keywords: MTHFR, non-sense mutation, white matter disease, microcephaly, severe methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency

Background

Severe 5,10-Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR; OMIM 236250) deficiency is a rare inborn error of metabolism and inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion. It is a very common disorder of folate metabolism and is clinically characterized with low plasma methionine level, high homocysteine level, homocystinuria, and hyperhomocysteinemia (1, 2).

MTHFR gene is responsible for the assembly of MTHFR enzyme, which plays a very important role in the catalysis of 5,10-methyltetrahydrofolate (THF) to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (an NADPH-dependent irreversible reduction) to obtain methionine from homocysteine (Supplementary Figure 1). Methyl THF is the most common form of folate in tissues and the plasma and serves as the methyl group donor in the methyl THF-homocysteine S-methyltransferase reaction involving remethylation of homocysteine to methionine (3).

The deficiency of MTHFR enzyme causes an increase in the concentration of homocysteine and methionine, resulting in severe neurological phenotypes. Patients having neonatal onset (i.e., early onset <1-year-old) MTHFR deficiency are mostly associated with feeding problems, neurological phenotype, microcephaly, seizures, and communicating hydrocephalus, while the late onset is characterized with delayed developmental milestones, cognitive impairment and/or gait abnormalities, stroke, apnoea, paresthesia, psychiatric disturbances, and neurological deterioration, which lead to coma and even death (4, 5).

In the present study, we performed direct whole exome sequencing (WES) to ascertain the genetic cause of severe MTHFR deficiency in the single affected individual (proband). As a result, we identified a homozygous non-sense mutation in MTHFR gene located on chromosome 1p36.22.

Case Presentation

Clinical Examination

The proband (III-7) genetically and clinically analyzed in the present study belongs to a non-consanguineous Egyptian family (Figure 1A). The parents had total seven children, three had deceased (III-1, III-2, and III-3) and showed (i.e., early onset <1 year old) similar phenotypes as the proband, healthy twin daughters (III-4 and III-5), one miscarriage (III-6), and the proband (III-7) (early onset <1 year). The deceased children age were: III-1:40 days, III-2: 2 months, III-3: 45 days; and all the deceased children became lethargic, hypoactive with poor suckling, with associated prolonged sleepiness. These were referred to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) as quarry neonatal sepsis. Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed subarachnoid hemorrhage and the patients died of apnoea, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and cardiorespiratory arrest.

Figure 1.

(A) Pedigree of the family segregating severe MTHFR deficiency. Pedigree clearly depicts an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance. Circles and squares represent females and males, respectively. Clear symbols represent normal, while filled symbols represent affected individuals. Slashes represents deceased individuals and triangle represents spontaneous abortion (SAB). The individual numbers labeled with asterisks were subjected to WES and the red arrow indicates the proband. (B) Pictures of the affected individual exhibiting microcephalic features at 1 month of age. (C) Brain MRI showing axial, coronal, and both T2 weighted images. These images revealed bilateral abnormal and symmetrical high signal intensity along the bilateral frontal horn in white matter, and the superior part of the periventricular deep white matter as well as within the subcortical basal temporal lobe white matter. The images also showed severely dilated ventricles and loss of white matter in cerebral hemispheres with prominent extra-axial CSF spaces. (D) A recent photograph of the proband (III-7) showing severe MTHFR deficiency.

First Clinical Evaluation

During the first clinical investigation, the proband (female; III-7) was 1-month-old with features such as non-obstructive hydrocephalus, recurrent apnea, microcephaly, and white matter abnormality (Figure 1B). The proband showed delayed growth during the last month of gestation. At birth, the head circumference was 31.5 cm, and the birth weight was 2,980 grams (Figure 1B). After 14 days, the proband developed apnea attacks and bradypnea and showed difficulties with swallowing. Ophthalmological examination demonstrated bilateral optic nerve hypoplasia, left retinal multiple hemorrhages, and normal anterior segment. The laboratory screening results revealed low white blood cell count, low platelet count, and high number of lymphocytes. Following multiple episodes of apnea, multi-sequential and multiplanar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. The MRI findings showed bilateral abnormal almost symmetrical T2. High signal intensity was observed in the white matter along the bilateral horn deep in the white matter, suggestive of white matter disease (Figure 1C). No chest infection, deafness, or cardiovascular anomaly was noted. The proband had a total blood homocysteine level of 163 nmol/mL (normal, 3.7–12.5 nmol/mL) and the plasma methionine range of < 5 (10–39 μmol/L). The proband was on regular medication such as betaine (100 mg·kg−1·day−1), methionine (50 mg·kg−1·day−1), vitamin B12 (5 mg PO 1/day), and L-5-MTHF (15 mg PO 1/day).

Follow-Up Examination

Follow-up examination after 10 months revealed that the proband could support her head but could not sit without support and may easily roll over (Figure 1D). Ophthalmic examination revealed optic atrophy, retinal hemorrhage, and the affected individual was unable to fix eyes nor follow. No hearing abnormality was observed. The proband was able to make sounds at the age of 4–5 months. Physical examination revealed a height of 79 cm (>95th percentile), weight of 10.7 kg (>95th percentile), and head circumference of 48 cm (>95th percentile). The total blood homocysteine level was 68 nmol/mL (normal, 3.7–12.5 nmol/mL), while the plasma methionine level was 54 μmol/L (normal, 10–39 μmol/L).

Materials and Methods

Study Approval and Sample Collection

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (KAIMRC) and followed Helsinki protocols. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the participant for the research study, presentation of photographs/radiographs, and publication of this case report.

DNA Extraction

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples using QIAamp DNA Micro kit (Hilden, Germany) and quantified using NanoDrop™ spectrophotometer using standard procedures.

WES

WES was commercially performed (Centogene, Rostock, Germany) for five family members, including the single affected individual (proband: III-7), both parents (II-3 and II-4), and twin sisters (III-4 and III-5) using Illumina platform (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA; Figure 1A). RNA capture baits against approximately 60 Mb of the human exome (targeting >99% of regions in the consensus coding sequence, RefSeq, and Gencode databases) were used to enrich the regions of interest from the fragmented genomic DNA with the SureSelect Human All Exon V6 kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The generated library was sequenced to obtain an average coverage depth of about 100X. In general, about 97% of the targeted bases are covered in more than 10X. Data analysis and interpretation were performed by Centogene using an end-to-end in-house bioinformatic pipeline with applications including base calling and alignment of reads to the GRCh37/hg19 (GRCh37; http://genome.ucsc.edu/) genome assembly.

Filtering of the Disease-Causing Variants

Primary filtering out of low-quality reads and probable artifacts and the subsequent annotation of variants were performed using standard methods. As the pedigree depicted autosomal recessive inheritance, homozygous and compound heterozygous variants were preferred but heterozygous variants were not ignored.

The variants were filtered and validated using standard methods (6) and screened in different databases such as dbSNP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/), 1000 genomes Project (http://www.internationalgenome.org/), ExAC (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/), and gnomAD (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/). Screening for the disease-causing variants (homozygous and compound heterozygous) led to the identification of a novel homozygous non-sense mutation (c.154C>T; p.Arg52*) in the exon 1 of MTHFR gene (NM_005957.4). Both the parents were heterozygous for the identified variant. The identified variant was absent in different available databases (dbSNP, 1000 genomes, ExAC, and gnomAD) and several in-house exomes (control).

In silico Analysis

Pathogenicity of the identified variant was evaluated with different online mutation prediction tools such as MutationTaster (mutationtaster.org), DNN (https://cbcl.ics.uci.edu/public_data/DANN/), FATHMM (fathmm.biocompute.org.uk), LRT (genetics.wustl.edu/jflab/lrt_query.html), VarSome (https://varsome.com/), CADD—Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/), and MutationAssessor (mutationassessor.org).

The identified variant (c.154C>T) was also subjected to Sanger sequencing with all the available members of the family using standard methods (Centogene, Germany), and the variant was shown to perfectly segregate with the disease phenotype.

Discussion and Conclusions

MTHFR (EC 1.5.1.20) is a key enzyme of the folate cycle involved in the catalysis of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, which is required for the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine. Methionine is subsequently metabolized to form S-adenosylmethionine. Thus, any disturbance in the pathway, either through the supply of cobalamin/folate or MTHFR deficiency, may cause accumulation of homocysteine, leading to altered patterns of methylation [(7–9); Supplementary Figure 1].

In the present study, we investigated a single affected individual (III-7) with MTHFR deficiency demonstrating severe features such as microcephaly, delayed growth, ophthalmic issues, non-obstructive hydrocephalus, elevated blood homocysteine level, and elevated plasma methionine levels. Features reported in the proband were similar to the previously reported cases (9–13). The affected individual had an early onset (<1 year) of the disease. It has been previously observed that the patients with early onset exhibit lesser residual enzyme activity than those with late onset (>1 year) (12). Residual enzyme activity was not tested in the present study. We performed WES for all the available members of the family (Figure 1A) and identified a homozygous non-sense mutation (c.154C>T; p.Arg52*) in MTHFR gene. The non-sense mutation (p.Arg52*) was located within the catalytic domain and most likely resulted in the complete loss of function of the MTHFR protein, either through non-sense-mediated mRNA decay or via the production of a truncated MTHFR protein.

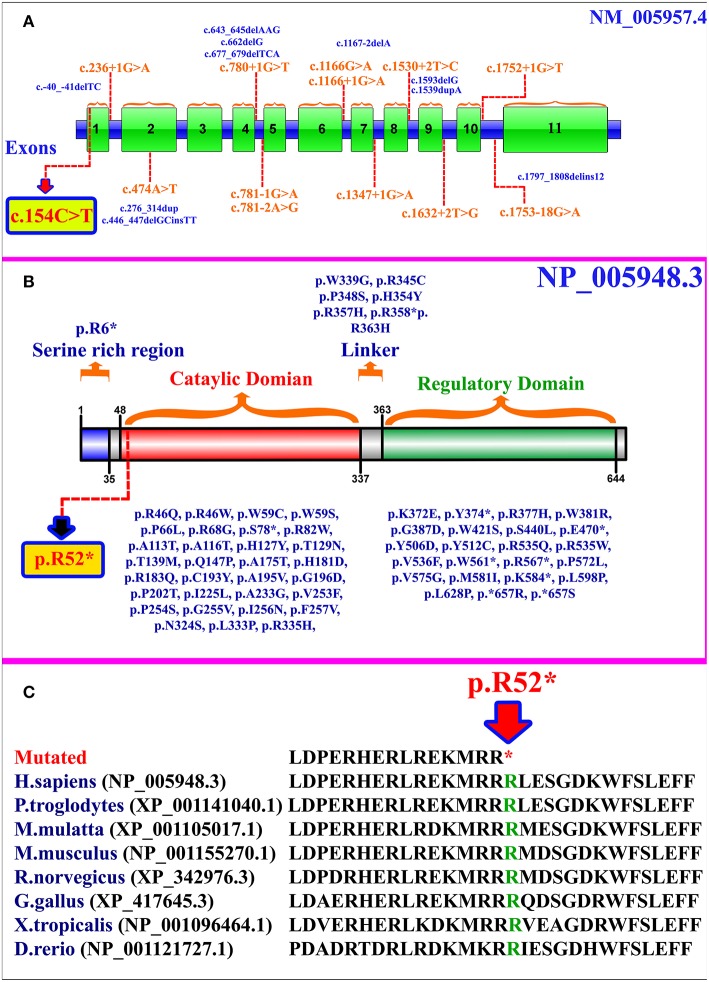

MTHFR gene is located on chromosome 1p36.22, exhibits 11 exons, and encodes a 656 amino acid protein (NP_005948.3) (Figure 2A). MTHFR protein exists as a homodimer comprising two N-terminal catalytic domains with binding sites for NADPH, methylene-THF, and cofactor FAD-linked to the regulatory domain (C-terminus) (Figure 2B). The mutation (p.Arg52*) identified herein is highly conserved across different species (Figure 2C). The exact association between the position of mutation and clinical phenotypes is yet unknown, as a biallelic loss-of-function mutation in any part of the protein results in extreme enzyme deficiency. This phenomenon highlights the importance of the complete peptide for proper enzyme activity (14).

Figure 2.

(A) MTHFR gene structure highlighting the already reported splice site and small deletion mutations. The variant identified in the present study is represented within a box. (B) Schematic representation of MTHFR protein and different domains. Missense and non-sense mutations are shown along each domain. The mutation identified in the present study is represented within a box. (C) Partial amino acid sequence of MTHFR protein showing conservation of Arg52 amino acid residue across different species.

As per our knowledge, 132 mutations have been reported in MTHFR gene that may cause several disorders such as homocystinuria, anencephaly, tetralogy of Fallot with cleft lip/palate, MTHFR deficiency, acute aortic dissection, reduced enzyme activity, association with preeclampsia, increased erythrocyte folate, respiratory failure and hypotonia, coronary heart disease, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome IV, and Facial palsy (11, 13, 15–18). Clinical comparison of patients with non-sense mutations in MTHFR gene has been compiled in Supplementary Table 1. Only 84 different mutations have been described in the literature that cause severe MTHFR deficiency, including 52 missense mutations, 12 splice acceptor/donor site, 8 non-sense mutations, 7 small deletions, 2 small indels, 2 start loss, and 1 gross insertion (Table 1). The majority of the mutations causing severe MTHFR deficiency are reported in the catalytic domain (Figure 2B).

Table 1.

Mutations reported in the MTHFR gene causing a severe 5-10-MTHFR deficiency.

| Disorder | Amino acid change | Nucleotide change | Mutation type | Exon/Intron | Domain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg6* | c.16A>T | Non-sense | Exon 1 | Serine rich |

| 2 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg46Gln | c.137G>A | Missense | Exon 1 | Catalytic |

| 3 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg46Trp | c.136C>T | Missense | Exon 1 | Catalytic |

| 4 | MTHFR deficiency | Trp59Cys | c.177G>T | Missense | Exon 1 | Catalytic |

| 5 | MTHFR deficiency | Trp59Ser | c.176G>C | Missense | Exon 1 | Catalytic |

| 6 | MTHFR deficiency | Pro66Leu | c.197C>T | Missense | Exon 1 | Catalytic |

| 7 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg68Gly | c.202C>G | Missense | Exon 1 | Catalytic |

| 8 | MTHFR deficiency | Ser78* | c.233C>G | Non-sense | Exon 1 | Catalytic |

| 9 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg82Trp | c.244C>T | Missense | Exon 2 | Catalytic |

| 10 | MTHFR deficiency | Ala113Thr | c.337G>A | Missense | Exon 2 | Catalytic |

| 11 | MTHFR deficiency | Ala116Thr | c.346G>A | Missense | Exon 2 | Catalytic |

| 12 | MTHFR deficiency | His127Tyr | c.379C>T | Missense | Exon 2 | Catalytic |

| 13 | MTHFR deficiency | Thr129Asn | c.386C>A | Missense | Exon 2 | Catalytic |

| 14 | MTHFR deficiency | Thr139Met | c.416C>T | Missense | Exon 2 | Catalytic |

| 15 | MTHFR deficiency | Gln147Pro | c.440A>C | Missense | Exon 2 | Catalytic |

| 16 | MTHFR deficiency | Ala175Thr | c.523G>A | Missense | Exon 3 | Catalytic |

| 17 | MTHFR deficiency | His181Asp | c.541C>G | Missense | Exon3 | Catalytic |

| 18 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg183Gln | c.548G>A | Missense | Exon 3 | Catalytic |

| 19 | MTHFR deficiency | Cys193Tyr | c.578G>A | Missense | Exon 3 | Catalytic |

| 20 | MTHFR deficiency | Ala195Val | c.584C>T | Missense | Exon 3 | Catalytic |

| 21 | MTHFR deficiency | Gly196Asp | c.587G>A | Missense | Exon 3 | Catalytic |

| 22 | MTHFR deficiency | Pro202Thr | c.604C>A | Missense | Exon 4 | Catalytic |

| 23 | MTHFR deficiency | Ile225Leu | c.673A>C | Missense | Exon 4 | Catalytic |

| 24 | MTHFR deficiency | Ala233Gly | c.698C>G | Missense | Exon 4 | Catalytic |

| 25 | MTHFR deficiency | Val253Phe | c.757G>T | Missense | Exon 4 | Catalytic |

| 26 | MTHFR deficiency | Pro254Ser | c.760C>T | Missense | Exon 4 | Catalytic |

| 27 | MTHFR deficiency | Gly255Val | c.764G>T | Missense | Exon 4 | Catalytic |

| 28 | MTHFR deficiency | Ile256Asn | c.767T>A | Missense | Exon 4 | Catalytic |

| 29 | MTHFR deficiency | Phe257Val | c.769T>G | Missense | Exon 4 | Catalytic |

| 30 | MTHFR deficiency | Asn324Ser | c.971A>G | Missense | Exon 5 | Catalytic |

| 31 | MTHFR deficiency | Leu333Pro | c.998T>C | Missense | Exon 5 | Catalytic |

| 32 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg335His | c.1004G>A | Missense | Exon 5 | Catalytic |

| 33 | MTHFR deficiency | Trp339Gly | c.1015T>G | Missense | Exon 5 | Catalytic |

| 34 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg345Cys | c.1033C>T | Missense | Exon 5 | Catalytic |

| 35 | MTHFR deficiency | Pro348Ser | c.1042C>T | Missense | Exon 6 | Regulatory |

| 36 | MTHFR deficiency | His354Tyr | c.1060C>T | Missense | Exon 6 | Regulatory |

| 37 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg357His | c.1070G>A | Missense | Exon 6 | Regulatory |

| 38 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg358* | c.1072C>T | Non-sense | Exon 6 | Regulatory |

| 39 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg363His | c.1088G>A | Missense | Exon 6 | Regulatory |

| 40 | MTHFR deficiency | Lys372Glu | c.1114A>G | Missense | Exon 6 | Regulatory |

| 41 | MTHFR deficiency | Tyr374* | c.1122C>G | Non-sense | Exon 6 | Regulatory |

| 42 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg377His | c.1130G>A | Missense | Exon 6 | Regulatory |

| 43 | MTHFR deficiency | Trp381Arg | c.1141T>C | Missense | Exon 6 | Regulatory |

| 44 | MTHFR deficiency | Gly387Asp | c.1160G>A | Missense | Exon 6 | Regulatory |

| 45 | MTHFR deficiency | Trp421Ser | c.1262G>C | Missense | Exon 7 | Regulatory |

| 46 | MTHFR deficiency | Ser440Leu | c.1319C>T | Missense | Exon 7 | Regulatory |

| 47 | MTHFR deficiency | Glu470* | c.1408G>T | Non-sense | Exon 8 | Regulatory |

| 48 | MTHFR deficiency | Tyr506Asp | c.1516T>G | Missense | Exon 8 | Regulatory |

| 49 | MTHFR deficiency | Tyr512Cys | c.1535A>G | Missense | Exon 9 | Regulatory |

| 50 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg535Gln | c.1604G>A | Missense | Exon 9 | Regulatory |

| 51 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg535Trp | c.1603C>T | Missense | Exon 9 | Regulatory |

| 52 | MTHFR deficiency | Val536Phe | c.1606G>T | Missense | Exon 9 | Regulatory |

| 53 | MTHFR deficiency | Trp561* | c.1683G>A | Non-sense | Exon 10 | Regulatory |

| 54 | MTHFR deficiency | Arg567* | c.1699C>T | Non-sense | Exon 10 | Regulatory |

| 55 | MTHFR deficiency | Pro572Leu | c.1715C>T | Missense | Exon 10 | Regulatory |

| 56 | MTHFR deficiency | Val575Gly | c.1724T>G | Missense | Exon 10 | Regulatory |

| 57 | MTHFR deficiency | Met581Ile | c.1743G>A | Missense | Exon 10 | Regulatory |

| 58 | MTHFR deficiency | Lys584* | c.1750A>T | Non-sense | Exon 10 | Regulatory |

| 59 | MTHFR deficiency | Leu598Pro | c.1793T>C | Missense | Exon 11 | Regulatory |

| 60 | MTHFR deficiency | Leu628Pro | c.1883T>C | Missense | Exon 11 | Regulatory |

| 61 | MTHFR deficiency | *657Arg | c.1969T>C | Stop loss | Exon 11 | Regulatory |

| 62 | MTHFR deficiency | *657Ser | c.1970G>C | Stop loss | Exon 11 | Regulatory |

| 63 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.236+1G>A | Splice | Intron 2 | Catalytic |

| 64 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.474A>T | Splice | Exon 2 | Catalytic |

| 65 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.781-2A>G | Splice | Intron 5 | Catalytic |

| 66 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.781-1G>A | Splice | Intron 5 | Catalytic |

| 67 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.780+1G>T | Splice | Intron 5 | Catalytic |

| 68 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.1166G>A | Splice | Exon 6 | Catalytic |

| 69 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.1166+1G>A | Splice | Intron 7 | Catalytic |

| 70 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.1347+1G>A | Splice | Intron 8 | Regulatory |

| 71 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.1530+2T>C | Splice | Intron 9 | Regulatory |

| 72 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.1632+2T>G | Splice | Intron 10 | Regulatory |

| 73 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.1753-18G>A | Splice | Intron 10 | Regulatory |

| 74 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.1752+1G>T | Splice | Intron 11 | Regulatory |

| 75 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.643_645delAAG | Small deletions | Exon 4 | |

| 76 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.-40_-41delTC | Small deletions 5′UTR | Intron 1 | Serine rich |

| 77 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.662delG | Small deletions | Exon 4 | Catalytic |

| 78 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.677_679delTCA | Small deletions | Exon 4 | Catalytic |

| 79 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.1167-2delA | Small deletions | Exon 7 | Regulatory |

| 80 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.1593delG | Small deletions | Exon 9 | Regulatory |

| 81 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.1539dupA | Small deletions | Exon 9 | Regulatory |

| 82 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.446_447delGCinsTT | Small indels | Exon 2 | Catalytic |

| 83 | MTHFR deficiency | – | c.1797_1808delins12 | Small indels | Exon 11 | Regulatory |

| 84 | MTHFR deficiency | Leu89_Pro101dup | c.276_314dup | Gross insertions | Exon 2 | Catalytic |

Furthermore, MTHFR knockout mice showed a decrease in methionine level, methionine/homocysteine ratio, dimethylglycine level, and lipid deposition in proximal aorta along with changes in cerebellar pathology, reduced cerebellum, reduced cerebral cortex, and developmental issues (19–21). A therapeutic strategy employing biochemical methods is important to normalize methionine level and decrease the plasma levels of homocysteine. Treatment for severe MTHFR deficiency is heterogeneous, and different combination and dosage of drugs are prescribed depending on the severity of the disorder. High doses of betaine have been suggested for patients with severe MTHFR deficiency (22, 23). Vitamins B6 and B12 supplementation with folic acid is also significant in the conversion of homocysteine into methionine. In the present study, the proband was prescribed a combination of betaine, methionine, vitamin B12, and L-5-MTHF that improved the overall condition, as she became more active, alert, and oriented and survived as compared to her affected siblings. At present, the proband is 14 months old, shows no apnea or seizure; hydrocephalus is not progressive and developmentally she can roll over. However, she is unable to sit, crawl, or walk and functions as a 4–5 months old infant. Folic acid dosages in combination with folate/folinic acid, hydroxocobalamin, cyanocobalamin, riboflavin, and carnitine have also been previously prescribed to some patients that could partially reduce the clinical symptoms and biochemical abnormalities (5).

In conclusion, we identified a novel biallelic non-sense mutation in a single affected individual suffering from severe MTHFR deficiency. MTHFR deficiency is potentially treatable when properly diagnosed at early stages. Clinicians should be aware of the phenotypes related to early-late onset of the disease. Timely molecular diagnosis and treatment with high dose of methyl donors is critical for the survival of these patients. Identification of the pathogenic variants of MTHFR gene may extend the knowledge about the spectrum of mutations and highlight the proper genotype-phenotype correlation.

Ethics Statement

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (KAIMRC) and followed Helsinki protocols. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the participant for the research study, presentation of photographs/radiographs, and publication of this case report.

Author Contributions

SM and MU drafted the manuscript, collected samples, clinical data, analyzed data, and performed experiments. MAla analyzed genomic data. MAla and MAlf edited the manuscript, while MAlf supervised the study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the family for participating in this study.

Footnotes

Funding. This study is funded by King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre, Riyadh (Grant: RC11/46).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2019.00411/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Dugalić S, Petronijevic M, Stefanovic A, Jeremic K, Petronijevic SV, Soldatovic I, et al. The association between IUGR and maternal inherited thrombophilias: a case-control study. Medicine. (2018) 97:e12799. 10.1097/MD.0000000000012799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu J, Li K, Zhou W. Relationship between genetic polymorphism of MTHFR C677T and lower extremities deep venous thrombosis. Hematology. (2019) 24:108–111. 10.1080/10245332.2018.1526440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams KT, Schalinske KL. Homocysteine metabolism and its relation to health and disease. Biofactors. (2010) 36:19–24. 10.1002/biof.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lossos A, Teltsh O, Milman T, Meiner V, Rozen R, Leclerc D, et al. Severe methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency: clinical clues to a potentially treatable cause of adult-onset hereditary spastic paraplegia. JAMA Neurol. (2014) 71:901–4. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huemer M, Mulder-Bleile R, Burda P, Froese DS, Suormala T, Zeev BB. Clinical pattern, mutations and in vitro residual activity in 33 patients with severe 5, 10 methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. (2016) 39:115–24. 10.1007/s10545-015-9860-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umair M, Shah K, Alhaddad B, Haack TB, Graf E, Strom TM, et al. Exome sequencing revealed a splice site variant in the IQCE gene underlying post-axial polydactyly type A restricted to lower limb. Eur J Hum Genet. (2017) 25:960–5. 10.1038/ejhg.2017.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowler B. Homocysteine: overview of biochemistry, molecular biology, and role in disease processes. Semin Vasc Med. (2005) 5:77–86. 10.1055/s-2005-872394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watkins D, Rosenblatt DS. Update and new concepts in vitamin responsive disorders of folate transport and metabolism. J Inherit Metab Dis. (2012) 35:665–70. 10.1007/s10545-011-9418-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenblatt DS, Lue-Shing H, Arzoumanian A, Low-Nang L, Matiaszuk N. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MR) deficiency: thermolability of residual MR activity, methionine synthase activity, and methylcobalamin levels in cultured fibroblasts. Biochem Med Metab Biol. (1992) 47:221–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goyette P, Sumner JS, Milos R, Duncan AM, Rosenblatt DS, Matthews RG, et al. Human methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase: isolation of cDNA, mapping and mutation identification. Nat Genet. (1994) 7:195–200. 10.1038/ng0694-195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burda P, Schafer A, Suormala T, Rummel T, Burer C, Heuberger D, et al. Insights into se- vere 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency: molecular genetic and enzymatic characterization of 76 patients. Hum Mutat. (2015) 36:611–21. 10.1002/humu.22779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Froese DS, Huemer M, Suormala T, Burda P, Coelho D, Guéant JL, et al. Mutation update and review of severe methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. Hum Mutat. (2016) 37:427–38. 10.1002/humu.22970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burda P, Suormala T, Heuberger D, Schäfer A, Fowler B, Froese DS, et al. Functional characterization of missense mutations in severe methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency using a human expression system. J Inherit Metab Dis. (2017) 40:297–306. 10.1007/s10545-016-9987-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leclerc D, Rozen R. [Molecular genetics of MTHFR: polymorphisms are not all benign]. Med Sci. (2007) 23:297–302. 10.1051/medsci/2007233297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rummel T, Suormala T, Häberle J, Koch HG, Berning C, Perrett D, et al. Intermediate hyperhomocysteinaemia and compound heterozygosity for the common variant c.677C>T and a MTHFR gene mutation. J Inherit Metab Dis. (2007) 30:401. 10.1007/s10545-007-0445-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohle C, Baehring JM. Multiple strokes and bilateral carotid dissections: a fulminant case of newly diagnosed Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. J Neurol Sci. (2012) 318:168–70. 10.1016/j.jns.2012.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu L, Bu H, Yang Y, Tan Z, Zhang F, Hu S, et al. A Targeted, next-generation genetic sequencing study on tetralogy of fallot, combined with cleft lip and palate. J Craniofac Surg. (2017) 28:e351–5. 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishida M, Cullup T, Boustred C, James C, Docker J, English C, et al. A targeted sequencing panel identifies rare damaging variants in multiple genes in the cranial neural tube defect, anencephaly. Clin Genet. (2018) 93:870–9. 10.1111/cge.13189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Z, Karaplis AC, Ackerman SL, Pogribny IP, Melnyk S, et al. Mice deficient in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase exhibit hyperhomocysteinemia and decreased methylation capacity, with neuropathology and aortic lipid deposition. Hum Mol Genet. (2001) 10:433–44. 10.1093/hmg/10.5.433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwahn BC, Chen Z, Laryea MD, Wendel U, Lussier-Cacan S, Genest J, Jr, et al. Homocysteine-betaine interactions in a murine model of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. FASEB J. (2003) 17:512–4. 10.1096/fj.02-0456fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Z, Schwahn BC, Wu Q, He X, Rozen R. Postnatal cerebellar defects in mice deficient in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Int J Dev Neurosci. (2005) 23:465–74. 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strauss KA, Morton DH, Puffenberger EG, Hendrickson C, Robinson DL, Wagner C, et al. Prevention of brain disease from severe 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. (2007) 91:165–75. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iida S, Nakamura M, Asayama S, Kunieda T, Kaneko S, Osaka H, et al. Rapidly progressive psychotic symptoms triggered by infection in a patient with methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency: a case report. BMC Neurol. (2017) 17:47. 10.1186/s12883-017-0827-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.