Abstract

In this paper, we aim to integrate the current conceptual approaches to stress and coping processes during the college transition with the potential role of mindfulness and compassion skills on students’ well-being and development. First, we provide an overview of the issues and challenges emerging adults are facing during the transition to college, drawing on the revised version of the transactional stress model by Lazarus and Folkman (1984). Second, we introduce a conceptual model of adaptive stress and coping processes enhanced by mindfulness and compassion (MC) skills to positively impact the appraisal and coping resources and emerging adults’ mental health. Specifically, mindfulness and compassion skills may play an important role in promoting a healthy stress response by strengthening emerging adults’ socioemotional competencies and supporting the development of adaptive appraisal and coping resources, including processes antecedent and consequent to a coping encounter. In particular, MC skills were hypothesized to enhance (1) preparedness to cope, (2) productive stress response through adaptive appraisals and skillful deployment of coping resources; and (3) healthy post-coping reflections. Therefore, MC skills may be a useful preventive tool to strengthen emerging adults’ ability to adjust to a new academic environment and fulfill the developmental tasks of this period.

Keywords: college stress, coping, developmental transitions, mindfulness, compassion

Introduction

The transition to college reflects a period of change in multiple life domains, including personal responsibilities, social supports, and institutional environments (e.g. Astin & Astin, 2015 Evans, Forney, Guido, Patton, & Renn, 2009). In Western societies, many young people are expected to find their occupational niche through college education or further vocational training and grow into healthy, independent, and contributing individuals. As a “rite of passage”, entering college and leaving home is associated with separation from family and friends, transition to become independent and self-regulating, and integration into a new social and academic environment (e.g. Masten et al., 2004; Schulenberg, & Zarrett, 2006). Thus, considerable coping resources are needed to navigate the college transition and address the stage-relevant tasks related to young adults’ professional and social life (Roeser, 2012).

There are numerous reports that indicate that being a college student is stressful and that many students lack the coping resources necessary to navigate this normative transition (e.g. Acharya, Jin, & Collins, 2018; Cleary, Walter, & Jackson, 2011; The American College Health Association, ACHA, 2014; The Jed Foundation, 2015). When the developmental instability characteristic of emerging adulthood is paired with inadequate coping, there is a high-risk of poor college adjustment, academic failure, substance abuse, or significant psychopathology (Dennhardt & Murphy, 2013; Kadison & DiGeronimo, 2004). Since college is a key institutional opportunity to impact people’s lives, understanding how colleges can equip students with coping processes may shape their well-being, academic progress, and successful resolution of key developmental tasks (Byrd & McKinney, 2012, Masten et al., 2004).

This paper has two foci. First, drawing on the transactional stress model (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984), we provide a conceptual analysis of factors influencing the coping processes during the college transition. Second, drawing on Developmental Contemplative Science (DCS, Roeser & Zelazo, 2012), we present a model of how mindfulness and compassion (MC) skills and practices may support students to strengthen attentional, cognitive and socioemotional competencies, and thus impact the coping process and healthy developmental outcomes. We conclude by providing suggestions of how mindfulness and compassion skills can provide a developmental, preventive approach to mental health needs of emerging adults attending college.

Issues and Challenges in Transition to College

Normative developmental transitions such as attending college are major life events that bring up discontinuities, departures from previous roles, and opportunities to develop new patterns and functioning (Schulenberg & Zarrett, 2006). Some individuals thrive under the newly gained freedom and the opportunity for increased self-selection of choices and activities. However, for some the lack of coping abilities and institutional supports creates a mismatch between needs and environmental affordances that may negatively impact their well-being (Byrd & McKinney, 2012).

According to psychosocial identity theory, students in the transition to college are engaged with the twin developmental tasks of developing a healthy identity while exploring intimacy with others (Erickson, 1968). Thus, young people face the challenge of both fostering understanding of oneself and meaningfully connecting to others who are similarly in a phase of identity exploration. These new tasks, and their accompanying emotions, require utilizing a wide range of personal and interpersonal resources to cope with the stressors such tasks entail. Extending Erikson’s theory, Arnett (2000) coined the term “emerging adulthood” (EA) to highlight the evolving nature of competencies that young people need to cultivate to manage the frequent changes in adapting to college (Masten et al., 2004; but see also Coté, 2014).

Empirical research shows that the college transition is associated with elevated stress and demands on self-regulatory skills (ACHA, 2014). In fact, a significant proportion of college students are considered to be at-risk for developing a variety of disorders, including depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and other stress-related conditions. The term “College of the Overwhelmed” encapsulates the high rates of mental health issues among college students (Kadison & DiGeronimo, 2004). Yet, because of the stigma associated with using mental health services, students seek help at relatively low rates (14% - Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein, & Zivin, 2009); and many self-medicate with drugs and alcohol (ACHA, 2014).

Although undergoing increased stress during the college transition is normative, individuals who learn active coping strategies to handle negative emotional states is predictive of successful adjustment (Dvořáková et al., 2017; Masten, Burt, & Coatsworth, 2006; Roeser, 2012). Research indicates that students suffering from mental health problems have worse peer and faculty relationships, less involvement in activities, and lower grades and graduation rates (Byrd & McKinney, 2012; Storrie, Ahern, & Tuckett, 2010). Thus, understanding the process of coping with new developmental demands is central to designing preventive efforts.

Appraisal and Coping Model during Transition to College

Coping describes the ways people react or respond to stressful situations. In this paper, we adopt the perspective that coping and emotion regulation are self-regulatory processes that exhibit overlapping yet distinctive characteristics. We consider coping as a broad term that refers to the overall cognitive and social processes associated with situational demands. In comparison, we consider emotion regulation as a more fine-grained term describing emotion-related factors during stressful and non-stressful circumstances (e.g. Compas et al., 2014, Gross, 1998). Since coping tends to refer to broader processes, it is our preferred theoretical approach to examining the mechanisms related to the transition to college. Finally, we use the term self-regulation to represent the overarching principle of both coping and emotion regulation (Carver, Scheier, & Fulford, 2008; Tamir, 2009).

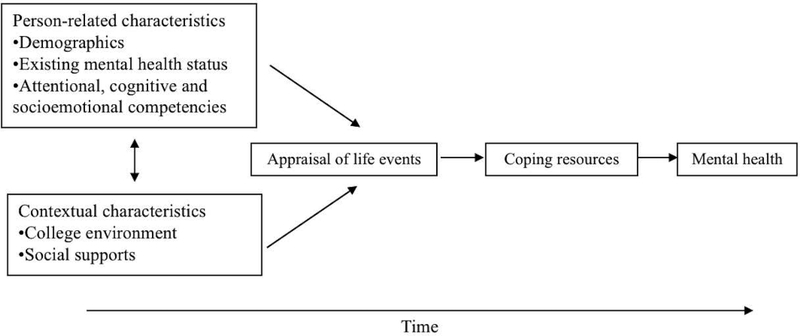

To conceptualize the stress and coping process students undergo, we adapt the transactional model of appraisal and coping from Lazarus & Folkman (1984). This model views the coping process as dependent on (a) environmental demands/stressors; (b) individual resources to meet those demands; and centrally (c) an appraisal process that is dependent on (a) and (b). Therefore, a key factor in investigating healthy coping is not only the nature of the objective stressors themselves but also the person’s regulatory flexibility apparent in the subjective appraisal of these stressors and whether one perceives oneself as having the resources (and thereby efficacy) to meet these challenges effectively (Beck & Clark, 1997; Bonnano & Burton, 2013). Figure 1 presents an adapted stress and coping model of factors affecting healthy adjustment in the college transition, highlighting how appraisal and coping resources affect mental health. Mental health is understood as both a source of coping resources and a set of skills/competencies that are acquired across the lifespan (Masten, Burt, & Coatsworth, 2006).

Figure 1.

Factors affecting healthy adjustment during the transition to college (adapted from Lazarus & Folkman, 1984)

We focus here on individual-personal and environmental-contextual characteristics as constituting the demands and resources bearing on the appraisal and coping process. These personal and contextual characteristics are dynamic and interactive and they influence each other in any instance. Person-related characteristics include factors such as social/economic/cultural background, preexisting mental health issues, and attentional, cognitive, and socioemotional competencies. Contextual characteristics include the quality of the college environment and access to social supports. These characteristics influence whether students might appraise a particular event (e.g., a demand) as potentially self-relevant in terms of being threatening or benign to one’s well-being (primary appraisal). When a situational demand is perceived as potentially self-relevant, the student evaluates if they are equipped with sufficient resources and tools to manage the demand (secondary appraisal). The evaluative distinction between a threat and challenge is important because a demanding event can be appraised as a fear-evoking stressor or as a learning opportunity with a corresponding biopsychosocial response (Blascovich, 2008). These individual-level appraisals shape students’ coping efforts, and thereby their daily functioning and well-being (Jamieson, Mendes, Blackstock, & Schmader, 2010).

Specifically, the stress and coping theory posits that when appraised demands exceed existing resources, stress arises and psychological well-being may deteriorate. During major developmental transitions, previously learned coping may not meet the new demands and may need to be enhanced or replaced by higher-order coping strategies (Compas et al., 2001; Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007). When a cycle of demands exceeding resources becomes chronic, the risk for mental health disorders and other lasting consequences increases. Below we elaborate the personal and contextual resources that impact the stress processes during transition to college.

Person-related characteristics during transition to college

Socio/economic/cultural characteristics.

In general, first-generation students, low SES students, or ethnic-minority students tend to be at higher risk for maladaptation or dropout. They often have lower grades in high school, receive less family support regarding college, and feel less academically capable (Ishitani, 2003, Kuh et al., 2008). Furthermore, minority students in predominantly White college settings face lack of connection due to racial discrimination which may place them at higher risk for maladaptive coping patterns, psychological distress and academic problems (Greene, Marti, & McClenney, 2008; Smith, Allen, & Danley, 2007).

Existing mental health status.

In a cross-national study, 83% of college students with a diagnosable mental health disorder (primarily anxiety and depression) reported an onset prior to college entry (Auerbach et al., 2016). In a US sample, students who felt less emotionally prepared for college reported lower GPA and poorer ratings of their college experience (The Jed Foundation, 2015). These preexisting psychological issues may increase students’ vulnerability to stress by compromising available resources and students’ ability to replenish such resources (Cleary, Walter, & Jackson, 2011).

Attentional, cognitive, and socioemotional competencies.

The ability to deploy attention is essential for self-regulation and well-being (Shapiro, Brown, & Astin, 2008; Roeser, 2012). Attentional focus and awareness enable self-regulation and socioemotional competencies such as recognizing and managing emotions, setting achievable goals, establishing positive relationships, and making safe choices. These competencies further promote the development of psychological flexibility and are closely related to healthy college adjustment and avoidance of engagement in risky behaviors (Masten et al., 2004; Moffitt et al., 2011). We examine and build on these competencies later in relationship to mindfulness and compassion skills.

Contextual characteristics during transition to college

College environment.

College-specific factors that influence a college adjustment include: the school mission and quality of education, financial resources and availability of scholarships, statement of values and respect for diversity, perception of safety, access to a counseling center, and availability of community-building and service learning activities (e.g. Kuh et al., 2008; Tinto, 2007). The theory of student involvement and its empirical evidence has emphasized that the provision of and engagement in meaningful university-related activities, such as those that prioritize students’ health and well-being, represents a valuable resource for student’s adjustment and academic thriving (Astin & Astin, 2015). Although many universities have expanded their mental health services rather dramatically, the need continues to largely outweigh the available resources.

Social supports.

The development of healthy relationships is a complex process with several conflicting aspects.. Although, healthy family relationships may protect students from the adverse effects of college stress (Hall et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2010), in Western cultures, the developmental task of establishing emotional independence from family is viewed as a necessary step towards healthy young adulthood (Coté, 2014; Masten et al., 2004). Furthemore, when students live in shared room residential halls, high quality roommate relationships can positively effect students’ well-being, while low quality relationships may further exacerbate mental health vulnerabilities and relationship insecurities(Dusselier et al., 2005; Haeffel & Hames, 2014). Thus, the competency to establish a sense of healthy social connectedness and access to meaningful social supports represent a critical adaptive resource.

Coping and Mental Health in College Students

There have been various ways of conceptualizing individuals’ coping efforts (see Skinner & Beers, 2015). Three broadly established categories of coping include problem-focused, emotion-focused, and meaning making coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Park & Folkman, 1997). Related coping strategies include, for example, problem solving and planning, soothing emotions, seeking supports, and making meaning of one’s experiences based on religious/spiritual beliefs, respectively. Furthermore, coping effectiveness is often associated with individuals’ avoidance or approach of stressful situations as reflected in their capacity tolerate and accept embrace unpleasant emotions, thoughts, and experiences (e.g. Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Spinhoven, Drost, de Rooij, van Hemert, & Penninx, 2014).

Specifically, college students’ maladaptive ways of coping involving experiential avoidance (e.g., withdrawal, self-blame, or suppression) have been associated with lower rates of educational persistence and higher rates of mental health problems and drinking behaviors (Mahmoud et al., 2012; Scott et al., 2004). In contrast, approach based emotion-focused coping, such as acceptance and positive reframing of stressful events, is associated with improved well-being (Pritchard, Wilson, & Yamnitz, 2007). Unfortunately, a recent college report found that the most frequent coping strategies during stress were avoidance-based, specifically sleeping (70%) and spending time online (64% - The Jed Foundation, 2015). Furthermore, as the rate of alcohol and drug abuse is double among college students compared to the general population, substance use likely is used as a major avoidance-oriented coping technique during college (Blanco et al., 2008; Martens, et al., 2008;) and 67% of students report drinking on average almost 5 alcoholic drinks during one event (ACHA, 2014).

Although evaluating the effectiveness of coping strategies is complex (e.g., Suls & Fletcher, 1985), research suggests that not only the approach of stressful situations, but psychological flexibility, are key factors (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010). For example, the same behavior (participation in Greek societies) represent both a protective factor of developmental adaptation (social connectedness) as well as a significant risk for health and academic performance (heightened drinking, Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002; Turrisi et al., 2006). As such, effective coping strategies are those that are broad and appropriate enough to address developmental needs without compromising student well-being (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Bonnano & Burton, 2013). From a regulatory flexibility perspective, the effectiveness of coping depends on students’ (1) sensitivity and appraisal of the current situation, (2) the range and variety of available resources and strategies, and (3) the reflective feedback loop that is involved in determining possible actions over time and learning from prior experience (Bonnano & Burton, 2013). Students’ self-regulatory ability to pause, reflect, and then choose a coping strategy may be a key resource to enhance their overall well-being. Here, we elaborate an alternative perspective of how particular social-emotional-cognitive skills, developed through the practices of mindfulness and compassion, may support effective coping during transition to college.

Conceptualizing Mindfulness and Compassion Skills as Coping Resources

Mindfulness and compassion can be considered conceptually as practices (e.g., Lutz, Dunne & Davidson, 2007), and as inherent personal qualities (e.g., states or traits) that may be further developed and nurtured throughout one’s life (Goetz, Keltner, & Simon-Thomas, 2010; Greenberg & Turksma, 2015). That is, mindfulness and compassion can be characterized as: (1) momentary, episodic state of awareness, (2) more enduring, trait-like features of awareness, or (3) a set of practices that cultivates the development of discrete states of mindfulness and compassion for a mindful and kind-hearted way of living (e.g. Davidson, 2010). In relationship to coping, MC skills, as personal qualities, inform the coping processes and, as practices, represent specific self-regulatory strategies.

We conceptualize mindfulness and compassion in terms of their component skills that are educable, such as the training of kind and non-judgmental attention to one’s or other’s experiences. Both contemplative sources and research literatures of related practices discuss differences between mindfulness and compassion (Hofmann, Grossman, & Hinton, 2011; Jha et al., 2016), as well as the interconnected nature of these constructs (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Neff, 2003). Here, we focus on the common, inter-related and salutary functions of these skills with regard to coping and healthy adaptation during this transition (e.g., Roeser, 2012).

Conceptualizing the Skills of Mindfulness.

Consensual definitions of mindfulness remain elusive in science (see Davidson & Kazniak, 2015). The most cited definitions of mindfulness is a process of “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally” (Kabat-Zin, 1994, p. 4). Based on this definition, Shapiro and colleagues (2006) described three elements of mindfulness: (1) underlying intention (“on purpose”); (2) attention (“paying attention”) with (3) an attitude of openness and curiosity (e.g., “non-judgmentally”). Relatedly, this definition was operationalized by Bishop et al. (2004) as consisting of two facets: (1) the self-regulation of attention and (2) an orientation toward experience in the present moment characterized by curiosity, openness, and acceptance. Hölzel et al. (2011) suggested several main component processes/skills that are cultivated by mindfulness meditation, including (1) improved regulation of attention; (2) increased somatic awareness; (3) improved emotion regulation; and (4) a shift in the experience of the self from identification to an enhanced clarity in experiencing the self.

Conceptualizing the Skills of Compassion.

Consensual definitions of compassion also remain elusive (Roeser & Eccles, 2015). A simple and straightforward way that compassion has been defined is the capacity to feel, and wish to relieve, the suffering of others (Miller, 2006). Jinpa (2010) conceptualized compassion as having four distinctive aspects, including (a) an attentional-cognitive aspect (an awareness of suffering), (b) an emotional aspect (an empathic concern in which one is moved by perceived suffering), (c) an intentional aspect (a wish to see that suffering alleviated), and (d) a behavioral aspect (a readiness to help to relieve suffering). In addition, approaches focused on self-compassion specifically focuses on (a) bringing mindful attention to one’s experience during the times of distress, (b) recognizing the common humanity aspect of suffering, and (c) responding with kindness rather than criticism (Neff, 2003).

Mindfulness and Compassion Skills.

One can see that componential skills of mindfulness and compassion are highly interrelated. These collective MC skills include the conscious regulation of attention, awareness of self (body, mind), awareness of others, and attitudes of openness, empathic curiosity, trust and care for self and others (e.g., Roeser & Pinela, 2014). Empirically, mindfulness and compassion (for self or others) are closely related as some studies report that enhanced mindfulness predicts increased self-compassion (Birnie et al., 2010) and enhanced self-compassion mediates the benefits of mindfulness practice (Kuyken et al., 2010; Roeser et al., 2013). These findings may be partly a result of the intercorrelations between these constructs, the difficulty with teasing apart the unique contributions of each, or issues with measuring these phenomena using self-reports (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015). At the same time, there is a growing evidence that suggests that mindfulness and compassion skills may positively impact young people’s well-being and health-related behaviors (Bamber, Kraenzle Schneider, & Schneider, 2016; Regehr, Glancy, & Pitts, 2013; Shapiro, Brown, & Astin, 2008; Yusufov, Nicoloro-SantaBarbara, Grey, Moyer, & Lobel, 2018) warranting further examination of the potential benefits during the transition to college. Here we conceptualize these collectively as mindfulness and compassion (MC) skills. We will consider MC skills as a key set of personal resources that can assist college students in coping and manifesting positive adaptation and growth across the college transition.

Indeed, research has begun to provide support for this conjecture. The preliminary evidence indicates that MC skills among college students are associated with positive outcomes, including mental health, self-regulation, cognitive and psychological flexibility, executive control, social connectedness, empathic and reflective tendencies, and healthy decision-making (Bamber, Kraenzle Schneider, & Schneider, 2016; Karyadi & Cyders, 2015; Masuda & Tully, 2012; Shapiro, Brown, et al., 2008). However, most of these studies results from cross-sectional surveys or single group interventions, and thus are inconclusive regarding causality. Well-developed experimental studies are needed to further examine how MC could promote adaptive coping strategies in young people, including minority and at-risk students (Bluth et al., 2016; Fung, Guo, Jim, Bear, & Lau, 2016). Furthermore, there is much less information on how mindfulness and compassion may impact college students’ coping and lead to improved well-being. In the next section, we propose a number of ways in which MC might promote adaptive coping during the college transition.

Adaptive Processes during Transition to College

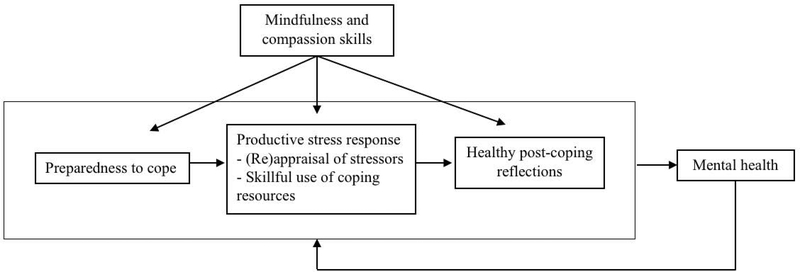

There are various ways in which MC might promote adaptive coping in students during the college transition. Specifically, we posit that different mindfulness and compassion skills can impact the appraisal/coping process during different parts of coping episodes, including processes that are antecedent to and consequent to the appraisal of “stressful” or “overwhelming” demands. Taking into account the sequential aspect of coping and related process of coping articulated by Lazarus & Folkman (1984) and Park & Folkman (1997), we propose that MC skills may (1) enhance preparedness to cope (e.g. proactive and anticipatory coping, new forms of meaning making with regard to self/other); (2) promote productive stress responses through adaptive appraisals/ new meaning-making with regard to demands/stressors (e.g., “this too shall pass”) and the conscious deployment of new coping strategies (e.g., “pausing, breathing”); and (3) promote healthy engagement in post-coping reflection (e.g., asking oneself after a stressful event what could have been done differently). Figure 2 depicts these proposed functions of MC skills on different phases of the hypothesized coping process.

Figure 2.

Adaptive stress and coping processes enhanced by mindfulness and compassion skills

Hypothesis: MC promotes preparedness to cope.

At the pre-coping phase, MC skills may be associated with a greater proactive and anticipatory coping through accumulation of effective resources. Proactive coping refers to general preparation for demanding life situations by (1) acquiring resources and skills or creating more adaptive systems of meaning; and (2) preventing or mitigating potential demands and maladaptive forms of meaning making (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997; Park & Folkman, 1997).

MC skills may also promote anticipatory forms of coping - those aimed at or intended to prevent a particular stressful occurrence that is likely to happen (Gross, 2014). For example, a young adult seeking social connections may choose to attend an alcohol-free social event instead of a fraternity party at which there will be drinking and other gender-related risks. Correlational studies support these claims as mindful awareness in college students was associated with lower alcohol use and problematic behaviors (Bodenlos, Noonan, & Wells, 2013; Fernandez, Wood, Stein, & Rossi, 2010; Karyadi & Cyders, 2015). In addition, mindfulness trait in college students has been associated with health behaviors, such as healthy eating, quality sleep, and overall physical health (Murphy et al., 2012; Roberts & Danoff-Burg, 2010). MC may work, in part, by enhanced attention and anticipatory self- regulation (Bishop et al., 2004; Hölzel et al., 2011; Shapiro et al., 2006), increasing student’s ability to opt out of situations that may be counterproductive and selectively choose to engage in meaningful activities (e.g. healthy niche picking) (Gross, 1998).

Another form of anticipatory coping involves gaining insight into one’s emotional triggers and habitual stress reactions to certain situational demands. Greater MC skills may help students to recognize their automatic responses to demanding experiences, and thus support a process of self-inquiry, self-clarification and perhaps behavioral change with an attitude of curiosity, openness, kindness, and non-judgment (Shapiro, Brown, & Astin, 2008). In experimental studies with healthy college students, MC mediated positive well-being outcomes as reflected in reduced stress and rumination, improved mental health, better sleep quality and lower incidence of negative alcohol consequences (Dvořáková et al., 2017; Shapiro, Oman, Thoresen, Plante, & Flinders, 2008). Furthermore, in students exposed to trauma, mindfulness trait may serve as a buffer against the harmful effects of trauma on mental health (Tubbs, Savage, Adkins, Amstadter & Dick, 2018).

Given the many challenges students will experience to their academic/social understanding and initial competence during the college transition, developing an attitude of self-compassion and caring may support improved daily functioning (Mahfouz et al., 2018). In a study following first semester students those who reported higher levels of self-compassion showed better college adjustment and were more satisfied with their social relationships (Terry, Leary, & Mehta, 2012). In another study with college students, a meditation-focused intervention enhanced participants’ prosocial and virtuous behavior (Condon et al., 2013).

Hypothesis: MC skills promote productive stress response through adaptive appraisals and deployment of coping strategies.

When facing demands, MC skills may enhance the student ability to appraise everyday situations as normative experiences. In stressful situations, mindful students may shift towards a more positive reappraisal and employ a wider range of coping resources.

Adaptive appraisals.

The initial appraisal process may be primed by MC skills to assess demands more objectively as normative learning opportunities. Mindful students may consistently use their personal and social resources to handle challenging situations, therefore appraising the upcoming events as manageable (Weinstein, Brown, & Ryan, 2009). For example, when academic demands are approached with eagerness to learn and succeed rather than anxiety and low confidence, students perform significantly better and feel more committed to graduate (Chemers, Hu, & Garcia, 2001). Even brief engagement in reflecting on positive experiences has been related to students feeling less threatened, more confident in test appraisal, and show better performance (Webster Nelson & Knight, 2010). Greater psychological flexibility may promote the contextually appropriate appraisal of normative daily situations (Bonnano & Burton, 2013) and reflect in lower distress during students’ college experience (Masuda & Tully, 2012).

During the process of secondary appraisal of a stressor in which one assesses available coping resources, mindful students may be better able to identify the reactive response to a stressful experience and shift toward an attitude of witnessing the situation (Farb et al., 2012; Hölzel et al., 2011). The mindful coping model by Garland et al. (2011) describes positive reappraisal through a process of decentering or “re-perceiving” (Shapiro et al., 2006) when the individual actively disengages from the initial negative judgement and through a metacognitive state of awareness turns towards positive meaning-making approach to the stressor. The key aspect is the open-minded state of broadened mindfulness and psychological flexibility that allows one to reframe the situation and adopt a more positive stance. Student’s ability to make positive meaning during the appraisal/coping process may broaden their beliefs about themselves and the world and strengthen their ability to manage future challenges (Park & Folkman, 1997). Furthermore, MC skills may lead to extinction of habitual emotional reactions and enhance one’s appraisal without engaging in conditioned reactivity, such as fear response or avoidance (Baer, 2003; Hölzel et al., 2011; Shapiro et al., 2006). By turning towards unpleasant sensations with a more relaxed attitude, conditioned patterns may be transformed and more adaptive states elicited (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002).

Skillful deployment of coping resources.

When coping with stressful encounters, MC skills may augment coping resources by supporting the adaptive functions of problem solving, emotion processing, and meaning finding. For example, during examinations, students experience contradictory appraisals, emotions, and motivations reflecting the dynamic and multifaceted process of appraisal and coping (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985; Jamieson et al., 2010). By using mindful somatic awareness, the student may be able to stay calm and attentive and employ specific regulatory skills, such as deep breathing or body scan. Through lowered reactivity to the challenging event and acceptance of difficult emotional states, students can better recognize and process their emotions before taking actions. Finally, by drawing on the caring aspect of compassion, students may be better able to evaluate when they need to take care of themselves during the times of distress (Neff, Rude, & Kirkpatrick, 2007).

In addition, MS skills may support more skillful deployment of available coping resources through the greater psychological flexibility. The “monitor and modify” feedback loop may allow for adaptive selection of coping strategies throughout the coping process based on a one’s alertness and evaluation of coping effectiveness (Bonnano & Burton, 2013). For example, a student who feels homesick may reflect on how much they miss their parents and the importance of close relationships for every human being. The student may notice the habitual reactivity to overeat or spend excessive screen time behavior. Through increased awareness and flexibility, the student may feel encouraged to make the conscious decision to reach out to close friends, participate in activities to meet like-minded people, or expand the limits of their comfort by engaging in new areas of interest (Mahfouz et al., 2018).

Hypothesis: MC skills promote healthy post-coping reflections.

After a stressful encounter and accompanied coping, there is an opportunity to evaluate the consequences and their future implications (Carver & Scheier, 1982; Skinner & Beers, 2016). Reflecting on the effectiveness of one’s coping, integrating these insights, and having a kind attitude to one’s self during the post-coping process represent important aspects of both self-regulation and developmental growth. This reflective cycle may promote adaptive stress recovery from the current coping situation and enhance preparedness for upcoming stressful situations.

Mindfully self-compassionate stance can aid students in refraining from maladaptive repetitive or overly critical thinking after negative emotional experiences (Neff et al., 2007; Shapiro, Oman, et al., 2008) which may in turn enhance their ability to learn from their mistakes and develop new strategies for future situations. Certain post-coping habits, such as rumination and catastrophizing, are linked to increased distress, drinking issues, and chronic mental health problems (Ciesla, Dickson, Anderson, & Neal, 2011; Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008). Alternatively, healthy reflections and positive attitude following a stressor aid the recovery process (Cho, Lee, Oh, & Soto, 2016; Kok & Fredrickson, 2010) and promote healthier future appraisals and coping strategies (Folkman, 2008; Skinner & Beers, 2016).

One study found that college students higher on dispositional mindfulness showed a faster emotional recovery after viewing unpleasant pictures (Cho et al., 2016), suggesting that MC skills may impact the duration of affective experiences. Self-compassion was associated with students’ ability to recognize alternative goals, perceive less fear of failure, and feel greater competence to manage academic demands (Neely et al., 2009). In sum, students with MC skills may experience less stress, recover more quickly, and learn more from challenging experiences. These factors may inform future stress cycles by strengthening students’ resources to cope and consequent sense of efficacy in meeting demands (Shapiro, Brown, & Astin, 2008).

Developmental and Preventive Approach to Mental Health Needs of College Students

For preventive interventions to be effective, they should be built on knowledge of the developmental processes of risk and protective factors. When these risk and protective factors have been identified, they can serve as targets of universal prevention/intervention programs to prevent common risks in the general population and to promote adaptive processes and alter maladaptive pathways (Greenberg & Abenavoli, 2017). During developmental windows of opportunity and challenge, preventive interventions that include MC skills may have higher impact because of the increased vulnerability of the whole system (Granic, 2005). The process of appraisal and the selection of coping strategies may be improved by strengthening protective attentional, socioemotional, and cognitive factors that buffer individuals against mental health malfunction. Given the instabilities of emerging adulthood, first year students are particularly in need of practices and trainings aimed at providing effective coping resources. Universities should proactively address students’ mental health issues and promote well-being through regular offerings of evidence-based programs (Conley, Durlak, & Kirsch, 2015).

Given the mental health issues and associated maladaptive coping in college students, preventive efforts to strengthen students’ cognitive-social-emotional skills are one method to support well-being and adjustment to college. The newly defined transdisciplinary approach of developmental contemplative science intends to deepen our understanding of how MC practice and skills can both alleviate distress and nurture positive human capacities during this critical developmental period (Roeser & Eccles, 2015). Through creating greater alignment between the person’s needs and opportunities for adaptive engagement with their environment, MC skills and practices may mitigate risk factors and strengthen protective factors. In particular, MC skills and practices may have the potential to impact the appraisal and coping processes through enhanced attention and cognitive skills, social-emotion regulation, and overall regulatory skills.

Conclusion

This conceptual analysis identified various factors impacting mental health during transition to college. The stress model by Lazarus and Folkman (1984) served as a foundation to explore the stress and coping processes and related personal and contextual characteristics. Furthermore, the socioemotional aspects of MC skills were hypothesized to enhance personal and interpersonal well-being of college students. In particular, MC skills and practices were postulated to enhance three causal processes; preparedness to cope, productive stress response through adaptive appraisals of stressors and skillful deployment of coping resources, and healthy post-coping reflections. Through MC skills, such as greater perceptual clarity, self-awareness and regulation, and clarified intentions and motivations, students can make different choices that maximize meaning and healthy social connections and, at the same time, minimize risk. Therefore, MC practices may be a useful preventive tool to strengthen students’ ability to adjust to the new college environment and fulfill the developmental tasks of this period. Further examination of MC in college students is needed to assure they can effectively and sustainably reduce stress and enhance coping processes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from National Institute on Drug Abuse, T32 DA017629 and the Bennett Endowment Fund at Edna Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Kamila Dvořáková, Human Development and Family Studies Department, Pennsylvania State University; Department of Addictology, 1st Faculty of Medicine, Charles University in Prague and the National Institute of Mental Health, Prague..

Mark T. Greenberg, Human Development and Family Studies Department, Pennsylvania State University

Robert W. Roeser, Human Development and Family Studies Department, Pennsylvania State University

References

- Acharya L, Jin L, & Collins W (2018). College life is stressful today–Emerging stressors and depressive symptoms in college students. Journal of American college health, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, & Taylor SE (1997). A stitch in time: Self-regulation and proactive coping. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 417–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astin AW, & Astin HSH (2015). Achieving Equity in Higher Education: The Unfinished Agenda. Journal of College and Character, 16(2), 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach RP, Alonso J, Axinn WG, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD, Green JG, … Bruffaerts R (2016). Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Bamber MD, Kraenzle Schneider J, & Schneider J (2016). Mindfulness-based meditation to decrease stress and anxiety in college students. Educational Research Review, 18, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, & Clark DM (1997). An Information Processing Model of Anxiey: Automatic and Strategic Processes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(I), 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnie K, Speca M, & Carlson LE (2010). Exploring self-compassion and empathy in the context of mindfulness-based stress reduction. Stress and Health, 26(5), 359–371. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, ... & Devins G (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical psychology: Science and practice, 11(3), 230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Liu S-M, & Olfson M (2008). Mental health of college students and their non-college-attending peers. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(12), 1429–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blascovich J (2008). Challenge and threat In Elliot AJ (Ed.), Handbook of approach and avoidance motivation (pp. 431–445). New York, NY, US: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bluth K, Campo RA, Pruteanu-Malinici S, Reams A, Mullarkey M, & Broderick PC (2016). A school-based mindfulness pilot study for ethnically diverse at-risk adolescents. Mindfulness, 7(1), 90–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenlos JSJ, Noonan M, & Wells SYS (2013). Mindfulness and alcohol problems in college students: the mediating effects of stress. Journal of American College Health, 61(6), 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldi P, & Vigna S (2016). Efficient optimally lazy algorithms for minimal-interval semantics. Theoretical Computer Science, 648, 8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, & Burton CL (2013). Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(6), 591–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brefczynski-Lewis JA, Lutz A, Schaefer HS, Levinson DB, & Davidson RJ (2007). Neural correlates of attentional expertise in long-term meditation practitioners, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(27), 11483–11488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, & Ryan RRM (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psych, 84(4), 822–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd DR, & McKinney KJ (2012). Individual, interpersonal, and institutional level factors associated with the mental health of college students. Journal of American College Health, 60(3), 185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, & Scheier MF (1982). Control theory: A useful conceptual framework for personality–social, clinical, and health psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 92(1), 111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, & Fulford D (2008). Self-regulatory processes, stress, and coping In John OP, Robins RW, & Pervin LA (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 725–742). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chemers MM, Hu L, & Garcia BF (2001). Academic self-efficacy and first year college student performance and adjustment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Lee H, Oh KJ, & Soto JA (2016). Mindful attention predicts greater recovery from negative emotions, but not reduced reactivity. Cognition and Emotion, 9931, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Dickson KS, Anderson NL, & Neal DJ (2011). Negative Repetitive Thought and College Drinking: Angry Rumination, Depressive Rumination, Co-Rumination, and Worry. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 35(2), 142–150. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen a H., & Wadsworth ME (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Jaser SS, Dunbar JP, Watson KH, Bettis AH, Gruhn MA, & Williams E (2014). Coping and emotion regulation from childhood to early adulthood: Points of convergence and divergence. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66(2), 71–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary M, Walter G, & Jackson D (2011). “Not always smooth sailing”: Mental health issues associated with the transition from high school to college. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32(4), 250–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon P, Desbordes G, Miller WB, & DeSteno D (2013). Meditation increases compassionate responses to suffering. Psychological Science, 24(10), 2125–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley CS, Durlak JA, & Kirsch AC (2015). A Meta-analysis of universal mental health prevention programs for higher education students. Prevention Science, 16(4), 487–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté JE (2014). The dangerous myth of emerging adulthood: An evidence-based critique of a flawed developmental theory. Applied Developmental Science, 18(4), 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ (2010). Empirical explorations of mindfulness: conceptual and methodological conundrums. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 10(1), 8–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, & Kaszniak A (2015). Conceptual and Methodological Issues in Research on Mindfulness and Meditation. American Psychologist, 70(7), 581–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennhardt AA, & Murphy JG (2013). Prevention and treatment of college student drug use: A review of the literature. Addictive Behaviors, 38(10), 2607–2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusselier L, Dunn B, Wang Y, Shelley M, & Whalen D (2005). Personal, Health, Academic, and Environmental Predictors of Stress for Residence Hall Students. Journal of American College Health, 54(1), 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvořáková K, Kishida M, Li J, Elavsky S, Broderick PC, Agrusti MR, & Greenberg MT (2017). Promoting healthy transition to college through mindfulness training with first-year college students. Journal of American College Health, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Downs M, Golberstein E, &Zivin K(2009).Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students.Medical Care Research and Review,66(5),522–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson E (1968). Identity Youth and Crisis. New York, NY: Morton. [Google Scholar]

- Evans N, Forney D, Guido F, Patton L, & Renn K (2009). Student development in college: Theory, research, and practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Farb N, Anderson AK, & Segal ZV (2012). The Mindful Brain and Emotion Regulation in Mood Disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(2), 70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez AAC, Wood MMD, Stein LAR, & Rossi JS (2010). Measuring mindfulness and examining its relationship with alcohol use and negative consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(4), 608–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S (2008). The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 21(1), 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, & Lazarus RS (1985). If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 150–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, & Moskowitz JT (2003). Positive Psychology from a Coping Perspective. Psychological Inquiry, 14(2), 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung J, Guo S, Jin J, Bear L, & Lau A (2016). A pilot randomized trial evaluating a school-based mindfulness intervention for ethnic minority youth. Mindfulness, 7(4), 819–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Gaylord S, & Fredrickson B (2011). Positive reappraisal mediates the stress reductive effetcs of mindfulness- an upward spiral process. Mindfulness. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz JJL, Keltner D, & Simon-Thomas E (2010). Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granic I (2005). Timing is everything: Developmental psychopathology from a dynamic systems perspective. Developmental Review, 25(3–4), 386–407. [Google Scholar]

- Greene TG, Marti CN, & McClenney K (2008). The effort—outcome gap: Differences for African American and Hispanic community college students in student engagement and academic achievement. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(5), 513–539. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, & Abenavoli R (2017). Universal Interventions: Fully Exploring Their Impacts and Potential to Produce Population-Level Impacts. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 10(1), 40–67. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, & Turksma C (2015). Understanding and Watering the Seeds of Compassion. Research in Human Development, 12(3–4), 280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Gross J (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(5), 271–299. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ (2014). Emotion regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations In Gross JJ (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 3–20). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel GJ, & Hames JL (2014). Cognitive vulnerability to depression can be contagious. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(1), 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hall ED, Mcnallie J, Custers K, Timmermans E, Wilson SR, & Bulck J. Van Den. (2016). A Cross-Cultural Examination of the Mediating Role of Family Support and Parental Advice Quality. Communication Research, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SSG, Grossman P, & Hinton DE (2011). Loving-kindness and compassion meditation. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1126–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel BK, Lazar S, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago D, & Ott U (2011). How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurrelmann K (1990). Health promotion for adolescents: preventive and corrective strategies against problem behavior. Journal of Adolescence, 13(3), 231–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishitani TT (2003). A longitudinal approach to assessing attrition behavior among first-generation students: Time-Varying Effects of Pre-College Characteristics. Research in Higher Education, 44(4), 433–449. [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Shapiro SL, Swanick S, Roesch SC, Mills PJ, Bell I, & Schwartz GER (2007). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 33(1), 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson JP, Mendes WB, Blackstock E, & Schmader T (2010). Turning the knots in your stomach into bows: Reappraising arousal improves performance on the GRE. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(1), 208–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinpa GT (2010). Compassion cultivation training (CCT): Instructor’s manual. Unpublished manuscript, Stanford University, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VK, Gans SE, Kerr S, & LaValle W (2010). Managing the Transition to College: Family Functioning, Emotion Coping, and Adjustment in Emerging Adulthood. Journal of College Student Development, 51(6), 607–621. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York, NY: Hyperion. [Google Scholar]

- Kadison R, & DiGeronimo T (2004). College of the overwhelmed: The campus mental health crisis and what to do about it. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Karyadi KA, & Cyders MA (2015). Elucidating the Association Between Trait Mindfulness and Alcohol Use Behaviors Among College Students. Mindfulness, 6(6), 1242–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, & Rottenberg J (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 865–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keltner D (2009). Born to be good: The science of a meaningful life. New York, NY: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Kiken LG, & Shook NJ (2011). Looking Up: Mindfulness Increases Positive Judgments and Reduces Negativity Bias. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(4), 425–431. [Google Scholar]

- Kok BE, & Fredrickson BL (2010). Upward spirals of the heart: Autonomic flexibility, as indexed by vagal tone, reciprocally and prospectively predicts positive emotions and social connectedness. Biological Psychology, 85(3), 432–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh GD, Cruce TM, Shoup R, & Kinzie J (2008). Unmasking the Effects of Student Engagement on First-Year College Grades and Persistence. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(5), 540–563. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken W, Watkins E, Holden E, White K, Taylor RS, Byford S, … Dalgleish T (2010). How does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy work? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(11), 1105–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz A, Dunne JD, & Davidson RJ (2007). Meditation and the neuroscience of con- sciousness In Zelazo P, Moscovitch M, & Thompson E (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness (pp. 499–555). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mahfouz J, Levitan J, Schussler D, Broderick T, Dvorakova K, Argusti M, & Greenberg M (2018). Ensuring College Student Success Through Mindfulness-Based Classes: Just Breathe. College Student Affairs Journal, 36(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud J, Staten R, Hall L, & Lennie T (2012). The Relationship among Young Adult College Students’ Depression, Anxiety, Stress, Demographics, Life Satisfaction, and Coping Styles. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33, 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Oster-Aaland L, & Larimer ME (2008). The Roles of Negative Affect and Coping Motives Among College Students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69(3), 412–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Burt KB, & Coatsworth J (2006). Competence and psychopathology in development In Cicchetti D & Cohen DJ (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 696–738). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Burt KB, Roisman GI, Obradović J, Long JD, & Tellegen A (2004). Resources and resilience in the transition to adulthood: continuity and change. Development and Psychopathology, 16(4), 1071–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda A, & Tully E (2012). The role of mindfulness and psychological flexibility in somatization, depression, anxiety, and general psychological distress. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 17(1), 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Killingsworth MA & Gilbert DT (2010). A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind. Science, 330(6006), 932–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayseless O (2016). The caring motivation: An integrated theory The caring motivation: An integrated theory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken LM, Gutierrez-Martinez O, & Smyth C (2013). “Decentering” reflects psychological flexibility in people with chronic pain and correlates with their quality of functioning. Health Psychology, 32(7), 820–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JP (2006). Educating for wisdom and compassion: Creating conditions for timeless learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, … Caspi A (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 2693–2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison R, & O’Connor RC (2005). Predicting psychological distress in college students: The role of rumination and stress. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 447–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MJ, Mermelstein LC, Edwards KM, & Gidycz CA (2012). The benefits of dispositional mindfulness in physical health: A longitudinal study of female college students. Journal of American College Health, 60(5), 341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely ME, Schallert DL, Mohammed SS, Roberts RM, & Chen Y-J (2009). Self-kindness when facing stress: The role of self-compassion, goal regulation, and support in college students’ well-being. Motivation and Emotion, 33(1), 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Rude SS, & Kirkpatrick KL (2007). An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(4), 908–916. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, & Lyubomirsky S (2008). Rethinking Rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oman D, Shapiro SL, Thoresen CE, Plante TG, & Flinders T (2008). Meditation Lowers Stress and Supports Forgiveness Among College Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of American College Health, 56(5), 569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, & Folkman S (1997). Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of General Psychology, 1(2), 115–144. [Google Scholar]

- Prillerman SL, Myers HF, & Smedley BD (1989). Stress, well-being, and academic achievement in college In Berry GL & Asamen JK (Eds.), Black students: Psychosocial issues (pp. 198–217). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard ME, Wilson GS, & Yamnitz B (2007). What predicts adjustment among college students? A longitudinal panel study. Journal of American College Health, 56(1), 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts KC, & Danoff-Burg S (2010). Mindfulness and Health Behaviors: Is Paying Attention Good for You? Journal of American College Health, 59(3), 166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeser RW (2012). Mindfulness as a self-care strategy for emerging adults. Focal Point: Young Adults & Mental Health – Healthy Body – Healthy Mind, 26, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Roeser RW, & Eccles JS (2015). Mindfulness and compassion in human development: Introduction to the special section. Developmental Psychology, 51(1), 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeser RW, & Pinela C (2014). Mindfulness and compassion training in adolescence. New Directions for Youth Development, 142, 9–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeser RW & Zelazo PDR (2012). Contemplative science, education and child development: Introduction. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- Roeser RW, Schonert-Reichl KA, Jha A, Cullen M, Wallace L, Wilensky R, … Harrison J (2013). Mindfulness training and reductions in teacher stress and burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 787–804. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, & Bridges MW (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, & Maggs JL (2002). A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, (14), 54–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, & Zarrett NR (2006). Mental Health During Emerging Adulthood: Continuity and Discontinuity In Arnett JJ & Tanner JL (Eds.), Emerging adults in America (pp. 135–172). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Scott D, Spielmans GG, Julka D, DeBerard MS, Spielmans GG, & Julka D (2004). Predictors of Academic Achievement and Retention Among College Freshmen: a Longitudinal Study. College Student Journal, 38(1), 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, & Teasdale JD (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SL, Brown KW, & Astin J (2008). Toward the integration of meditation into higher education: A review of research. Teachers College Record, 113(3), 493–528. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin J, & Freedman B (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 62(3), 373–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SL, Oman D, Thoresen CE, Plante TG, & Flinders T (2008). Cultivating mindfulness: Effects on well-being. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(7), 840–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, & Beers J (2016). Mindfulness and Teachers ‘ Coping in the Classroom : A Developmental and Everyday Resilience In Schonert-Reichl KA & Roeser RW (Eds.), Handbook of Mindfulness in Education (pp. 99–118). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, & Zimmer-Gembeck MJ (2007). The development of coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 119–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WA, Allen WR, & Danley LL (2007). “Assume the position... you fit the description” psychosocial experiences and racial battle fatigue among African American male college students. American Behavioral Scientist, 51(4), 551–578. [Google Scholar]

- Storrie K, Ahern K, & Tuckett A (2010). A systematic review: students with mental health problems—a growing problem. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16(1), 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinhoven P, Drost J, de Rooij M, van Hemert A, & Penninx B(2014). A longitudinal study of experiential avoidance in emotional disorders.Behavior Therapy, 45(6), 840–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, & Fletcher B (1985). The Relative Efficacy of Avoidant and Nonavoidant Coping Strategies: A Meta-Analysis. Health Psychology, 4(3), 249–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano K, Iijima Y, & Tanno Y (2012). Repetitive Thought and Self-Reported Sleep Disturbance. Behavior Therapy, 43(4), 779–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamir M (2009). What do people want to feel and why? Pleasure and utility in emotion regulation. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(2), 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Terry ML, Leary MR, & Mehta S (2012). Self-compassion as a Buffer against Homesickness, Depression, and Dissatisfaction. Self and Identity, 12(3), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- The American College Health Association (ACHA) (2014). American College Health Association National College Health Assessment II: Spring; 2014. Hanover, MD. [Google Scholar]

- The Jed Foundation, The Jordan Matthew Porco Foundation, & The Partnership for Drug Free Kids. (2015). The first-year college experience.

- Tinto V (2007). Research and Practice of Student Retention: What Next? Journal of College Student Retention, 8(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tubbs JD, Savage JE, Adkins AE, Amstadter AB, & Dick DM (2018). Mindfulness moderates the relation between trauma and anxiety symptoms in college students. Journal of American college health, (just-accepted), 1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Mallett KA, Mastroleo NR, & Larimer ME (2006). Heavy drinking in college students. The Journal of General Psychology, 133(4), 401–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster Nelson D, & Knight AE (2010). The power of positive recollections: Reducing test anxiety and enhancing college student efficacy and performance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(3), 732–745. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein N, Brown KW, & Ryan RMR (2009). A multi-method examination of the effects of mindfulness on stress attribution, coping, and emotional well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(3), 374–385. [Google Scholar]

- Yusufov M, Nicoloro-SantaBarbara J, Grey NE, Moyer A, & Lobel M (2018). Meta-analytic evaluation of stress reduction interventions for undergraduate and graduate students. International Journal of Stress Management. [Google Scholar]