We thank the authors for their interest in our original article.1 We have read their argument and we offer responses on 2 main points: (1) “The challenges with studying populations of non-European ancestry remains one of terminology” and (2) “So although the authors describe the potential for identifying risk prediction for AA [African Americans], this may not be applicable to all patients as the term reflects a broad racial group and ignores genetic origin and ethnic factors.”

We agree with the letter that our findings of genetic loci and specific variations associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in African Americans1 will not be applicable to all persons that are self-identified as African American (or “black” American) race. We also agree that, in genomic research, different terminologies like race, ethnicity, and ancestry are often used to outline differences in humans. Although race is primarily unitary and refers to physical appearance, ethnicity accounts for sharing language, social practice/traditions, cultural heritage, and more. Self-identified African Americans can have both different levels of African and European ancestry (ie, different ethnic origins). The main issue is that self-reported ancestry is not a good surrogate for direct genomic assessment in African Americans. This will also be true of all genetic studies of broad population groups, and is as much a challenge in studying the genetics of European (white) ancestral populations as it is with non-Europeans (non-whites). For example, a comparison of NOD2 predisposing Crohn’s disease mutations between Norwegians and Germans identified great differences in not only allele frequencies but also in mutation risk.2 The difference in risk may be due to differences in gene–gene interactions (ie, genes that interact with NOD2 may also have different frequencies) or gene–environmental interactions (ie, owing to differences in uncharacterized environmental exposures necessary for NOD2 Crohn’s disease risk). Despite this heterogeneity, inflammatory bowel disease risk alleles that have been established in broad studies of persons of European ancestry, such as the landmark Immunochip study3 will, in general, be applicable to most persons that are predominately of European descent who have been raised in the countries (ie, Western industrialized countries) where the subjects for these studies were recruited. Similarly, the risk alleles we identified in our genome-wide association study of African Americans will apply to most persons that are self-identified as African American/black race.1 For our population, a “self-identified African American” will refer to the overwhelming majority of individuals evaluated in our study: that is, persons (1) whose ancestors primarily originated from West Africans forcibly brought to America as part of the slave trade, (2) with a variable degree of European ancestry (average 20%) from continual admixture with Europeans from colonial history forward (the latter ancestry clearly evident by the significant NOD2 risk observed for European origin NOD2 mutations4), and (3) who were born in the United States (given the tremendous increase in inflammatory bowel disease over the last several decades throughout the world and environmental factors interacting with genetic factors). Among the “self-identified” African American subjects of our study, there will be persons who are essentially African and have immigrated to the United States or who have mostly European ancestry, but those subjects only made up a very small percentage of our total study population (Figure 1). Last, in contrast with the letter, African Americans are usually not considered as a “migrant population” (unless one refers to all Americans except for the indigenous Amerindian population as migrants) as the North American ancestry of most African Americans precedes that of white Americans (given the great European migrations from 1830 to 1940).

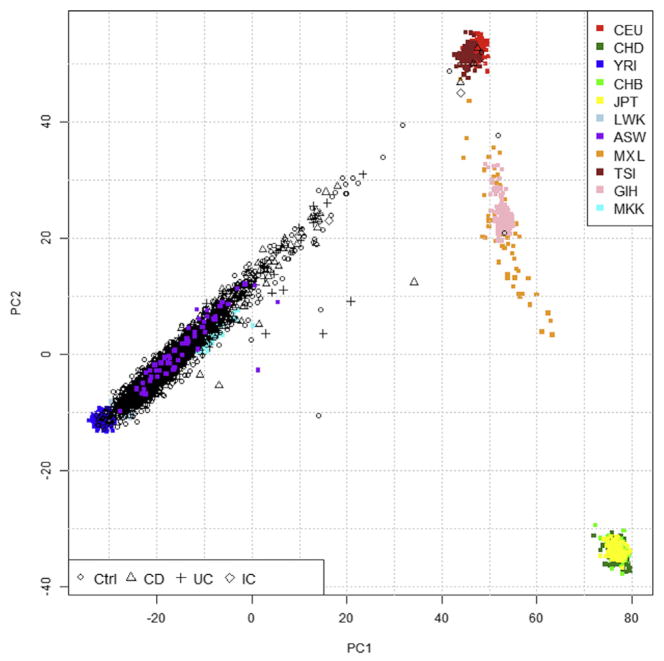

Figure 1.

Genetic ancestry of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) cases and matched controls by principle components of ancestry informative markers (AIMs). Graph of first 2 principle components of autosomal genome-wide AIMs among Crohn’s disease (black triangles), ulcerative colitis (black crosses), and indeterminate colitis (black diamonds) cases, and healthy controls (black circles), all self-described as African Americans, relative to positions of HapMap populations as follows: CEU, Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry; CHD, Chinese in Denver, CO; YRI, Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria; CHB, Han Chinese in Beijing, China; JPT, Japanese in Tokyo, Japan; LWK, Luhya in Webuye, Kenya; ASW, African Americans in the Southwest USA (all having 4 grandparents also identified as African American); MXL, Mexican ancestry in Los Angeles, CA; TSI, Toscani in Italy; GIH, Gujarati Indians in Houston, TX; MKK, Maasai in Kinyawa, Kenya. Each point in the figure represents one individual. IBD cases are a subset of study subjects from Brant et al,1 and the controls are African Americans without IBD recruited by the same IBD recruitment centers.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Contributor Information

DAVID T. OKOU, Department of Pediatrics, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia

STEVEN R. BRANT, Department of Medicine, Meyerhoff Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center and, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland

CLAIRE L. SIMPSON, Department of Genetics, Genomics and Informatics, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee

TALIN HARITUNIANS, F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel and Immunobiology, Research Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

CHENGRUI HUANG, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland.

DERMOT P. B. MCGOVERN, F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel and Immunobiology, Research Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California

SUBRA KUGATHASAN, Department of Pediatrics and, Department of Human Genetics, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia.

References

- 1.Brant SR, et al. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:206–217. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medici V, et al. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:459–468. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jostins L, et al. Nature. 2012;491:119–124. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adeyanju O, et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2357–2359. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]