Abstract

In the 30 years since the discovery of nucleocytoplasmic glycosylation, O-GlcNAc has been implicated in regulating cellular processes as diverse as protein folding, localization, degradation, activity, post-translational modifications, and interactions. The cell coordinates these molecular events, on thousands of cellular proteins, in concert with environmental and physiological cues to fine-tune epigenetics, transcription, translation, signal transduction, cell cycle, and metabolism. The cellular stress response is no exception: diverse forms of injury result in dynamic changes to the O-GlcNAc sub-proteome that promote survival. In this review, we discuss the biosynthesis of O-GlcNAc, the mechanisms by which O-GlcNAc promotes cytoprotection, and the clinical significance of these data.

Keywords: Signal transduction, ogt, mgea5, chaperone, heat shock response, glycoprotein

Summary Statement

Protein modification by the sugar O-GlcNAc is elevated following injury, including heart attack. This increase promotes survival. This review describes the current understanding of the mechanisms by which O-GlcNAc protects cells during stress and injury and discusses the clinical implications of these data.

Introduction

Cells and tissues respond to environmental and physiological injury by reprogramming transcription, translation, metabolism and signal transduction to affect repair and survival, and if necessary to promote programmed cell death. Collectively, this cell-wide reprogramming is known as the cellular stress response and is characterized by the induction of chaperones known as heat shock proteins (HSP) (1–3). In 2004, we reported that global O-GlcNAc levels were induced in a dose-dependent manner in response to a wide range of cellular stressors in several mammalian cell lines and that augmentation of O-GlcNAc levels promoted the induction of HSPs and cell survival in a model of heat stress (Table 1) (4). Combined, these data suggested that stress-induced O-GlcNAcylation was one target of the mammalian stress response. Since then, numerous reports have demonstrated that this response, termed the O-GlcNAc-mediated stress response, is conserved in both transformed and primary cells as well as several forms of physiological injury. Furthermore, augmentation of O-GlcNAcylation promotes cell and tissue survival in models ranging from heat stress to myocardial ischemia reperfusion (I/R) injury (Table 1) (5).

Table 1:

Summary of Stressors that Induce the O-GlcNAc Modification and Models in Which Enhance O-GlcNAcylation in Protective.

| Model | Cell/Tissue Type |

Stress-induced Elevation in O- GlcNAc† |

O-GlcNAc Protective |

Method of Modulation‡ |

Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenite | Cos7, HepG2, MEFs, U2OS, | ✓ | N/A§ | N/A | (4,77,106,107) |

| Bleocin (DNA damage) | Cos-7 | ✓ | N/A | N/A | (12) |

| Brefeldin A | NRVM | ✓ | ✓ | Genetic, pharmacological | (72) |

| Cobalt Chloride | Cos-7 | ✓ | N/A | N/A | (4) |

| Doxorubicin (DNA damage) | Cos-7 | ✓ | N/A | N/A | (12) |

| DTT (ER Stress) | Hek293, HepG2, MEFs | ✓ | ✓ | eIF2α mutation | (74,106) |

| Ethanol | Cos-7 | ✓ | N/A | N/A | (4,106) |

| Glucose deprivation | cardiac stem cells, C2C12, HEK293, HeLa, Neuro2-a | ✓ | N/A | N/A | (22,32,108) |

| Glyoxal | HRMEC | ✓ | ✓ | Genetic, pharmacological | (109) |

| Heat Shock | Cos-7, Chang, Cho, HCAEC, Hep3B, HepG2, HEK293, HeLa, L929, MEFs, Neuro-2A, NVRM | ✓ (one report decreased) | ✓ | Genetic, metabolic, pharmacological | (4,27,57,58,60,106,107,110) |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Cos-7, HeLa, HepG2, HREC, MEFs, NRVM, RGC5 | Complex | ✓ | Genetic, metabolic, pharmacological | (4,6,13,106) |

| Hypoxia & Hypoxia reoxygenation | A549, cardiac stem cells, H1299, HEK293T, mESC, NVRMs, renal proximal tubule cells |

✓ | ✓ | Genetic, metabolic, pharmacological; PFK1 Ser 529; G6PD Ser84. | (9,70,72,73,89,90 ,108,111) |

| I/R, IPC, rIPC, simulated I/R | Brain tissue (murine, rat), heart tissue (rat, murine, human), NRVM | Complex | ✓ | Genetic, metabolic, pharmacological | (8,10,13,28,29,37,60,95,98,100) |

| Iodoacetamide | Cos-7 | ✓ | N/A | N/A | (4) |

| Lipopolysaccharide | Raw164.7, human macrophage | ✓ | N/A | N/A | (34) |

| Lysosomal inhibition | Cos-7 | ✓ | N/A | N/A | (4) |

| Osmotic Stress (Hyper) | Cho, Cos-7, HCAEC, HeLa, HEK293T, HepG2, MEFs, Neuro-2A, | Complex | N/A | N/A | (4,12,80,106,107) |

| Osmotic stress (hypo) | HEK293T | Reduced | ✓ | Genetic, metabolic | (112) |

| Peritonial dialysis fluid)-osmotic stress, low pH, glucose degradation products | HPMC, MeT-5A | ✓ | ✓ | Metabolic, pharmacological | (113) |

| Proteosomal Inhibition | Cos-7, U2OS | ✓ | N/A | N/A | (4,77) |

| Ribosomal Inhibition | Cos-7, MEFs | ✓ | N/A | N/A | (4,106) |

| Streptozotocin & Fas-Ligand/PUGNAc | Liver, Pancreas, Kidney (Mouse) | ✓ | ✓ | K18 S30/31/49 | (59) |

| Thapsigargin (ER stress) | Hek 293, HepG2 | ✓ | ✓ | eIF2α mutation | (74) |

| Trauma Hemorrhage | Rats | Complex | ✓ | Metabolic, pharmacological | (7,36,84,85,96) |

| Tunicamycin (ER stress) | Cos-7, MEFs, NVVMs | ✓ | ✓ | Genetic, Pharmacological | (12,72,106) |

| UV | Cos-7 | ✓ | N/A | N/A | (4) |

| γ Irradiation | HeLa, | ✓ | N/A | N/A | (114) |

In some models O-GlcNAc levels decline, before becoming elevated. This phenotype is annotated as “complex”. In other models of injury, O-GlcNAc levels decrease. This phenotype is annotated as “reduced”. Models in which there are conflicting data, which may result from experimental differences, are also labeled “complex”.

Pharmacological modulation of O-GlcNAc refers to the inhibition of OGA with Thiamet-G, NAG-Thiazalone, or PUGNAc or the O-GlcNAc transferase with TT04, 4Ac-SGlcNAc, or OSIM-1; Genetic modulation refers to the manipulation of OGT or OGA expression by deletion, RNA interference, or overexpression; Metabolic manipulation refers either to inhibition of GFAT with DON or Azaserine, or to feeding cells with metabolites of the HBP such as glucosamine, N-acetylglucosamine, and glutamine.

N/A, Not Addressed in this model.

Cell lines referred to in this table: A549, human lung carcinoma (epithelial); C2C12, mouse muscle cell (myoblast); Chang, HeLa cell derivative (epithelial); Cho, Chines hamster ovary cells (epithelial); Cos-7, African green monkey kidney fibroblast-like (fibroblast); DAOY, Human medulloblastoma cells (polygonal); H1299, human lung carcinoma (Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, epithelial); H9C2, rat heart/myocardium myoblast; HCAEC, Human coronary artery endothelial cells, primary; HeLa, human cervical adenocarcinoma (epithelial); HEK293, human embryonic kidney (epithelial); HEK293T, human embryonic kidney (epithelial); Hep3B, Human liver hepatocellular carcinoma (epithelial); HepG2, Human liver hepatocellular carcinoma (epithelial); HPMC, human peritoneal mesothelial cells, primary; HREC, human retinal microvascular endothelial cells, primary; L929, mouse fibroblasts; mESC, mouse stem cells; MEFs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; MeT-5A, human Mesothelium (epithelial); NRVM, neonatal rat ventricular myocytes, primary; Neuro2A, murine neuroblastoma (neuroblast); RGC5, retinal ganglion cells; U2OS, human bone osteosarcoma (epithelial).

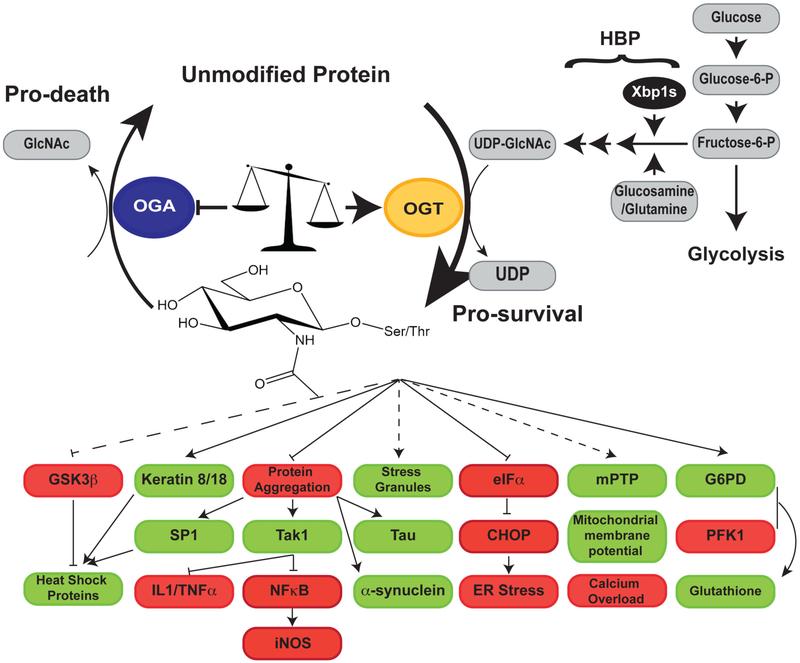

Several reports suggest that stress-induced changes to the O-GlcNAc sub-proteome are more complicated than originally proposed. Studies in models of oxidative stress, in particular in vivo I/R injury and trauma hemorrhage, demonstrate that O-GlcNAcylation can decline (6–13). In some models this decline precedes an increase in O-GlcNAcylation (6), and in others it is associated with the onset of apoptosis and tissue death (7–10,13). The identification of proteins dynamically O-GlcNAcylated in response to injury (oxidative, heat stress, and trauma hemorrhage) support these studies (6,7,12). Notably, in a model of oxidative stress, a subset of proteins are targeted for deglycosylation even when global O-GlcNAcylation is increased (6). Collectively, these data lead us to amend the original model proposed (4): preventing deglycosylation of key proteins acts in concert with enhanced glycosylation on other proteins to prevent apoptosis/necrosis and to promote survival (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

In response to injury, there are significant and dynamic changes to the OGlcNAc sub-proteome. As increasing O-GlcNAc levels promotes survival, and as decreasing OGlcNAc levels promotes apoptosis and necrosis, stress-induced changes in O-GlcNAcylation are thought to reprogram cellular pathways promoting survival. Stress-induced changes in the OGlcNAc modification correlate with increased expression, activity and substrate targeting of OGT (yellow) and decreased expression and activity of OGA (blue), as well as increased flux through the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway. One mechanism supporting metabolic remodeling is increased expression of GFAT, the rate-limiting enzyme in the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, which is mediated by the transcription factor Xbp1s. O-GlcNAc has been demonstrated to activate proteins/pathways (green) leading to cell survival (for example, heat shock protein expression) and to inhibit proteins (red) that promote cell death (for example, CHOP activation), collectively increasing cellular protection. For some pathways, the molecular mechanism by which O-GlcNAc mediates survival/inhibition are unknown (dashed lines), whereas for others the O-GlcNAcylated proteins and sites have been identified (solid lines). Nonetheless, additional work is required to fully delineate how O-GlcNAc promotes a pro-survival phenotype. Abbreviations used in this figure: G6PD, Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; GFAT, Glutamine fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase; GSK3β, Glycogen synthase kinase 3β; mPTP, mitochondrial permeability transition pore; OGA, O-GlcNAcase; OGT, O-GlcNAc transferase; IL1, Interleukin 1; PFK1, Phosphofructokinase 1; TNF〈, Tumor necrosis factor 〈;Xbp1s, Spliced X-box binding protein 1.

Dynamic O-GlcNAcylation is well positioned to reprogram cellular pathways in response to cellular stress. To date, over a thousand proteins have been described as O-GlcNAcylated, many of which play important roles in mediating cellular homeostasis with well-described roles in epigenetics, transcription, mRNA biogenesis, protein degradation, signal transduction and metabolism (14,15). Consistent with these data, O-GlcNAc has been implicated in mediating cell survival decisions via numerous pathways that include transcription, stress granule formation, HSP synthesis, altered metabolic flux, reduced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and improved mitochondrial function. These data, and the clinical implications of the O-GlcNAc-mediated stress response, are discussed below.

Regulation of O-GlcNAcylation During Injury

The O-GlcNAc modification is cycled by two enzymes, the O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and the O-GlcNAcase (OGA). OGT, which catalyzes the addition of the O-GlcNAc residue, exists as three well-characterized isoforms: nucleocytoplasmic, mitochondrial, and short (16,17). Each isoform contains a C-terminal glycosyltransferase domain and a variable number of N-terminal tandem tetratricopeptide repeats (TPR) (18–21). The substrate specificity of OGT is postulated to be regulated by the TPR domain and protein interactors of OGT (22,23). Deletions in the TPR domain that do not affect the catalytic activity of OGT alter OGT’s ability to glycosylate protein substrates (24,25). This model is further supported by findings that the three isoforms have different peptide and protein substrates (25,26).

In cell culture models, stress-induced O-GlcNAcylation is coincident with increased enzymatic activity, protein expression, and nuclear localization of OGT (4,27). Similarly, in isolated heart tissue subjected to ex vivo or remote ischemic preconditioning (rIPC), increased O-GlcNAc levels were associated with elevated OGT expression and activity (28,29). In neuroblastoma cells exposed to glucose deprivation, p38 mitogen activated protein kinase is critical for targeting OGT to specific substrates such as neurofilament protein H (22). In the aforementioned model, glucose deprivation induced OGT expression in an AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-dependent manner (22). Regulation of OGT expression at the post-transcriptional level has also been demonstrated. In patients with congestive heart failure, microRNA-423–5p was found to be elevated. In cultured cardiomyocytes, microRNA-423–5p was demonstrated to target the 3’ untranslated region (3’ UTR) of OGT mRNA, suppressing OGT expression (30).

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) also regulate OGT. In fact, OGT is itself O-GlcNAcylated at two sites within the catalytic domain (18,19,31). OGT is phosphorylated at Tyr979, Thr444, and Ser3 or Ser4 (18,32,33). While the implications of these PTMs are unknown in models of injury, phosphorylation at Thr444 is catalyzed by AMPK in vitro and augments OGT nuclear localization in glucose-deprived muscle cells (32). In the fine-tuning of the circadian clock, glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) phosphorylates OGT at Ser3 or Ser4 resulting in activation of OGT (33). Finally, it has been shown in vitro and in vivo that OGT is basally S-nitrosylated in macrophages, inhibiting catalytic activity, and is activated by de-nitrosylation when macrophages are stimulated by lipopolysaccharide (34).

Another regulator of OGT activity is the availability of its nucleotide sugar substrate, UDP-GlcNAc (24). Elevated UDP-GlcNAc levels increase OGT’s affinity for its peptide substrates (18,24). Immediate elevations in UDP-GlcNAc levels are observed in cancer cell lines in response to treatment with the chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin (35). Moreover, modest elevations in UDP-GlcNAc levels have been reported in myocardial I/R injury (10,36,37). Increased flux through the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP), which generates UDP-GlcNAc, may be a result of increased glucose flux, which is a common response of cells to injury (38). Recent data suggest that cellular stress directly upregulates the HBP (37). Spliced X-Box Binding Protein 1 (Xbp1s) is a transcription factor that promotes the expression of chaperones and other mediators of the unfolded protein response (UPR)(37). One target of Xbp1s is the gene encoding glutamine fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase 1 (GFAT1), the enzyme catalyzing the rate-limiting step of the HBP. Xbp1s was demonstrated to increase GFAT1 expression in vivo in a murine model of I/R injury, elevating flux through the HBP and global O-GlcNAc levels (37). Similarly, another study demonstrated that prostate cancer cells overexpressing the enzyme UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase 1, which catalyzes the final step of the HBP, have significantly-upregulated HBP flux and are protected from ER stress (39).

The removal of O-GlcNAc is catalyzed by OGA, a soluble N-acetylglucosaminidase (40–42). There are two well-characterized isoforms of OGA: full-length OGA and short OGA (41–43). Short OGA preferentially localizes to the nucleus and lipid droplets (43), whereas the full-length isoform is found in the nucleus, cytoplasm and mitochondria (41,42,44). Less is known about the regulation of OGA, although it can be cleaved by caspase 3 (45) and is O-GlcNAcylated (46), phosphorylated, ubiquitinated, and acetylated (47–50). The impact of these PTMs on the localization, substrate specificity, or activity of OGA has not been reported. Little is known about the regulation of OGA levels in stressed cells. In models of rIPC, increased O-GlcNAc levels are associated with decreased OGA activity (28). In a cell culture model of I/R injury and murine infarct-induced heart failure, miRNA-539 levels were up-regulated resulting in decreased OGA expression (51).

Several regulatory mechanisms of O-GlcNAc levels in cells and tissues have been discussed. However, it remains unclear if cells and tissues coordinate all of these mechanisms to affect stress-induced changes in O-GlcNAcylation, or if different cells and tissues induce specific pathways depending on the type of stress.

Mechanisms by which O-GlcNAc Promotes Survival

Elevating O-GlcNAcylation augments survival in a broad range of cells and tissues challenged with diverse stressors, suggesting that stress-induced changes in O-GlcNAcylation are a conserved defense against injury that enable cellular remodeling to promote survival (Table 1). Several studies have begun to delineate the mechanisms by which O-GlcNAc confers cytoprotection.

Regulation of Heat Shock Protein expression

Heat shock proteins and heat shock factors (HSF), the transcription factors that mediate HSP synthesis, are central mediators of proteostasis during the cellular stress response (52) and are emerging as a key pathway regulated by O-GlcNAc. Specifically, pharmacologically elevating O-GlcNAcylation prior to heat stress increases HSP72 and HSP40 expression, whereas blocking the HBP reduces the expression of HSP72 (4). To determine if O-GlcNAc modulates the expression of other chaperones, Kazemi and co-workers developed a cell line in which OGT deletion could be induced with 4-hydroxytamoxifen. Deletion of OGT alters the basal and stress-induced expression of 18 of the 84 chaperones tested (27). Under basal conditions, GSK3β inhibits HSF1 via phosphorylation of Ser303 (53,54). Elevating O-GlcNAcylation suppresses HSF1 Ser303 phosphorylation, which is in part mediated by inhibition of GSK3β by phosphorylation at Ser9 (27). The regulatory effect of O-GlcNAc on chaperone expression has been recapitulated in a number of cell and physiological models of injury (13,55–58).

Regulation of HSP expression via the GSK3/AKT axis has also been demonstrated with another stress-induced regulator, Keratin 18 (K18). Glycosylation of K18 at Ser30, Ser31 and Ser49 (59) is protective following acute liver injury, with K18 triple glycosylation mutant (K18Gly-) mice exhibiting higher susceptibility to streptozotocin or PUGNAc/Fas-ligand induced death (59). Phosphorylation of AKT at Thr308 was decreased following PUGNAc/Fas-ligand induced injury with a concomitant decrease in phosphorylation of GSK3α at Ser21 in K18Gly-mice, as well as a decrease in HSP72 expression (59). Together these studies indicate that glycosylation is required for AKT activation of a pro-survival phenotype. In addition to direct regulation of HSP pathways, O-GlcNAcylation may prevent protein aggregation as in the case of αB crystalline (60) and the transcription factor Sp1 (57), allowing them to bind to and initiate transcription of HSP, respectively. Furthermore, Sp1 is stabilized through the co-translational addition of O-GlcNAc to nascent polypeptide chains, preventing its proteasomal degradation (61). Together these data suggest that O-GlcNAc positively regulates HSP pathways through a variety of mechanisms.

O-GlcNAc disrupts protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases

Recent studies have begun to delineate the protective effects of O-GlcNAc in diseases of protein aggregation, which play an important role in neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s disease where hallmark proteinaceous inclusions contribute to pathophysiology (62). α-synuclein is the major structural component of Lewy bodies in Parkinson’s disease, first aggregating to form oligomeric species that ultimately polymerize into fibers (62). α-synuclein is O-GlcNAcylated in vivo at residues Thr64, Thr72 and Ser87 (63–65). α-synuclein glycosylated at Thr72, generated semisynthetically by expressed protein ligation, inhibited α-synuclein aggregation and fiber formation in a dose-dependent manner, with fully glycosylated species exhibiting little to no aggregation (66). In addition, cellular proliferation was increased and α-synuclein-induced toxicity decreased in cells treated with α-synuclein glycosylated at Thr72 compared to unmodified protein (66). A similar phenotype has been demonstrated for Tau, the oligomeric species in Alzheimer’s disease. O-GlcNAcylation of Tau at Ser400 inhibited oligomerization in vitro, which was not seen with Tau S400A (67). In the JNPL3 model of Alzheimer’s disease, which harbors the FTDP-17 tauP301L transgene, mice treated with Thiamet-G (TMG) to elevate O-GlcNAc levels displayed 1.4 times as many motor neurons and had decreased pathologic Tau phosphorylation (Ser202) compared with controls. TMG treatment increased glycosylation of Tau at Ser400 in these mice, suggesting that protective effects of TMG are mediated through a disruption in Tau aggregation (68).

O-GlcNAc inhibits the hallmarks of ischemia reperfusion injury

Much of the work delineating how O-GlcNAc regulates cellular injury has been done in models of I/R injury. In neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVM) subjected to hypoxia-reoxygenation, elevating O-GlcNAcylation by overexpressing OGT or inhibiting OGA reduced reactive oxygen species and calcium overload (9). Some of these protective effects originate in the mitochondria where O-GlcNAc is necessary for maintenance of mitochondrial membrane potential and prevents the formation of the mitochondrial membrane transition pore (13,69,70). One mechanism by which these effects may occur is through direct O-GlcNAcylation and regulation of the voltage-dependent anion channel, which regulates flux of Ca2+ through the mitochondria (13,69,70).

O-GlcNAc reduces ER stress

The protective effects of O-GlcNAc are not limited to mitochondrial function but also rescue injury caused by ER stress. The accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER signals through inositol-requiring 1 (IRE1), PKR-like ER kinase (PERK) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) to recruit chaperones, such as BiP, in order to increase folding capacity and eliminate misfolded proteins (71). In the event that protein misfolding cannot be contained, the cell signals through eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) and the transcription factor C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) to induce apoptosis (71). In NRVMs treated with the ER stressors brefeldin A and tunicamycin, O-GlcNAc attenuates the activation of the maladaptive arm of the UPR and reduces cardiomyocyte death. Reduced cell death has been correlated with decreased activation of CHOP (72). Similar results have been demonstrated in a rabbit model of renal I/R injury where CHOP levels were suppressed upon administration of glucosamine (73). eIF2α phosphorylation by PERK is required for CHOP activation. O-GlcNAcylation of eIF2α (Ser219, Thr239 and Thr241) may hinder its phosphorylation, thus suppressing CHOP activation (74). In addition, OGT stabilizes hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF1α), a transcription factor, by reducing its hydroxylation and subsequent degradation via the ubiquitin E3 ligase von Hippel–Lindau (pVHL) (75). Depletion of OGT alone induced the maladaptive arm of the ER stress response, and this phenotype was reversed by overexpression of hydroxylation/degradation resistant HIF1α mutants (75). Further function has been demonstrated for O-GlcNAc in mitigating ER stress through the formation of stress granules (SG) and processing bodies (PB), which primarily regulate mRNA translation and degradation, respectively (76). OGT and the HBP are required for stress-induced SG assembly and constitutive PB assembly (77). Upon stress, O-GlcNAcylated proteins, such as receptor for activated C kinase 1 (RACK1), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and ribosomal subunit proteins are found in SG, whereas most of OGT is localized elsewhere. These observations indicate that OGT modifies proteins that are subsequently recruited to SG. Combined, these data suggest that OGT and O-GlcNAc play central roles to mitigate ER stress and prevent apoptosis.

O-GlcNAc-mediated regulation of the inflammatory-driven stress response

Activation of inflammatory signaling pathways is characteristic of the stress response (78,79). Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β-activated kinase (TAK1) is a serine/threonine kinase composed of a catalytic subunit in complex with regulatory subunits (TAK binding proteins (TAB) 1/2/3) (80). TAK1 activates various kinases, such as c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1), ERK1, and nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB), that result in the production of proinflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) (81–83). TAB1 is O-GlcNAcylated at Ser295 both basally and in response to IL-1 and osmotic stress (80). O-GlcNAcylation results in elevated TAK1 activity, including phosphorylation of the downstream targets JNK1/2 and Ikappa B-α (Iκβα). Activation of TAK1 is blocked with mutation of TAB1 S295A, also diminishing NFκB activation and subsequent production of TNFα and interleukin-6 (80).

Elevating O-GlcNAcylation has also been demonstrated to reduce pro-inflammatory signaling through decreased NFκB activation in models of trauma hemorrhage (36,84,85) and arterial injury (86–88). Here, NFκB phosphorylation at Ser536 decreases concomitant with increased glycosylation on the regulatory subunit p65, promoting IκBα binding (86). Decreased NFκB signaling attenuates chemokine production and subsequent infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages (86) as well as a reduction in inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and nitrotyrosine formation (87).

Retuning metabolism with O-GlcNAc enables cancer cells to resist stressful tumor microenvironments

Inhibiting OGA or overexpressing OGT to elevate O-GlcNAcylation decreases the rate of glucose metabolism under normoxia and hypoxia, with a concomitant decrease in lactate and ATP levels (89). This change in metabolism is regulated by glycosylation of phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK1) at Ser529, an intermediate enzyme in glycolysis that converts fructose-6-phosphate to fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, and results in decreased catalytic activity (89). Suppressing glycolysis activates the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) to provide pentose sugars for nucleotide and nucleic acid biosynthesis as well as NADPH for the synthesis of the cellular antioxidant glutathione. Furthermore, PFK1 was glycosylated in various solid tumors and malignant tissues, suggesting that cancer cells may inhibit PFK1 activity through glycosylation to enhance flux through the PPP and to promote cellular proliferation (89). Further studies have demonstrated a direct role for O-GlcNAc within the PPP. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), the rate-limiting enzyme of the PPP, is O-GlcNAc modified in response to hypoxia at Ser84 (90). Increasing O-GlcNAcylation enhanced G6PD oligomerization and activity in cells expressing wild type, but not G6PD S84V, protein. G6PD O-GlcNAcylation was accompanied by increased flux through the PPP and an enhanced proliferative phenotype. Similar to the aforementioned study, glycosylation of G6PD enhanced tumor formation and was more abundant in human lung cancer tissue (90). Collectively, these and other data suggest that cancer cells have hijacked the O-GlcNAc-mediated stress response to promote growth in adverse environments (91).

Clinical Implications of O-GlcNAc-Mediated Cytoprotection

The conservation of the O-GlcNAc-mediated stress response highlights the potential for modulation of this pathway in a wide range of clinical models (Table 1). Critically, in models of ex vivo myocardial I/R injury (92) and in vivo trauma hemorrhage (36,84) elevating O-GlcNAcylation post-injury is protective. Moreover, OGT is necessary for post-infarct remodeling of the heart (93). Pharmacological inhibitors of OGA, such as TMG, have been used to suppress protein aggregates in models of tauopathies, are orally bioavailable, and appear non-toxic (68,94). One alternative to pharmacological modulation are metabolites that augment flux through the HBP (Figure 1). Both glucosamine and glutamine have been demonstrated to improve survival and organ function (10,11,36,56,73,95–98), although the effectiveness of oral glucosamine supplementation is controversial (99). Alternatively, glucose-insulin-potassium administration both augments O-GlcNAc levels and promotes cardioprotection (100).

While elevating O-GlcNAcylation transiently in the models discussed above is protective, chronic elevation of O-GlcNAcylation has been associated with the development of hypertension (101), heart failure (51,102,103), glucose toxicity, and type II diabetes (14). The molecular mechanisms underlying the transition from protection to pathology are unknown. One simple model is that elevating O-GlcNAcylation acutely is protective whereas chronic elevation is toxic. Such timing is not unique among stress response pathways: chronic upregulation of HSPs is toxic in cells challenged with a chronic proteostasis stress (104). In all likelihood, the model is more complex because of an altered molecular landscape, including changes in the proteome and PTMs therein. Ultimately, maladaptation of cellular pathways is predicted to lead to decreased O-GlcNAc cycling at specific sites as well as altered substrate specificity and activity of the enzymes that cycle O-GlcNAc. Indeed, Ma and co-workers recently demonstrated that the protein interactors of OGT were changed in a model of streptozotocin-induced diabetes (44). Collectively, these data lead to a critical yet unanswered question: how do chronic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, alter the O-GlcNAc-mediated stress response? Two recent studies provide some insight into this question. Jensen and co-workers showed that rIPC was ineffective on diabetic atrial trabeculae, and unlike control samples, had no effect on O-GlcNAcylation (28). In the second study, O-GlcNAc levels did not respond to brain I/R injury in old animals whereas O-GlcNAc levels were elevated in the brains of young mice (105). These data suggest that simple modulation of O-GlcNAc levels may not be specific enough in clinical models.

Concluding remarks

Collectively, the data discussed suggest that targeting O-GlcNAcylation of key proteins may lead to the development of novel therapeutics for ameliorating cell and tissue death in a wide range of injury models. To achieve an understanding of how O-GlcNAcylation is relevant to translational medicine, there are several barriers that need to be overcome and include: 1) identifying proteins and quantifying sites of O-GlcNAcylation targeted during injury and defining the role of O-GlcNAc on these proteins/sites; 2) characterizing the mechanisms that lead to protein-specific changes in the O-GlcNAc modification during injury, especially the targeting of OGT and OGA to substrates; and 3) determining how conditions such as aging, which alter the ability of tissues to respond to injury, impact the O-GlcNAc-mediated stress response. Answering such challenges will build a map of the O-GlcNAc signaling network from which the role of O-GlcNAc in diverse models can be probed, providing critical insight into the role of this modification in cellular homeostasis and disease pathology.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Kamau Fahie Ph.D. and Jennifer Groves for their constructive criticism of the manuscript. We would like to acknowledge the work of researchers whose data was not discussed due to space limitations.

Funding information:

This work is supported by grants to NEZ from the National Institutes of Health: P01HL107153 (NHLBI) and R21DK108782 (NIDDK).

Abbreviations

- 3’-UTR

3’-untranslated region

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- ATF6

activating transcription factor 6

- CHOP

transcription factor C/EBP homologous protein

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- G6PD

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFAT1

Glutamine fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase 1

- GSK3β

Glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- eIF2α

eukaryotic initiation factor 2α

- HBP

Hexosamine biosynthetic pathway

- HIF1α

Hypoxia inducible factor α

- HSF

Heat shock factors

- HSP

Heat shock protein

- IκBα

IkappaB-α

- I/R

Ischemia reperfusion

- IRE1

inositol-requiring 1

- IL-1

Interleukin-1

- JNK1

c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1

- K18

Keratin 18

- K18Gly

K18 triple glycosylation mutant

- NRVM

Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes

- NFκB

Nuclear factor kappa B

- O-GlcNAc

Modification of intracellular proteins by monosaccharides of O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine

- OGA

O-GlcNAcase

- OGT

O-GlcNAc transferase

- PB

Processing bodies

- PERK

PKR-like ER kinase

- PFK1

Phosphofructokinase 1

- PPP

Pentose phosphate pathway

- PTM

Post-translational modifications

- rIPC

Remote ischemic preconditioning

- SG

Stress granules

- TAB

TAK binding protein

- TAK1

Transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase

- TMG

Thiamet-G

- TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor α

- TPR

Tetratricopeptide repeat

- UPR

Unfolded protein response

- Xbp1s

Spliced X-box binding protein 1

Footnotes

Declarations of interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Nollen EAA, Morimoto RI. Chaperoning signaling pathways: molecular chaperones as stress-sensing ‘heat shock’ proteins. Journal of Cell Science. 2002;115(Pt 14): 2809–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morimoto RI. The Heat Shock Response: Systems Biology of Proteotoxic Stress in Aging and Disease. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. [Online] 2012;76(0): 91–99. Available from: doi: 10.1101/sqb.2012.76.010637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Åkerfelt M, Morimoto RI, Sistonen L. Heat shock factors: integrators of cell stress, development and lifespan. Nature Publishing Group; 2010;: 1–11. Available from: doi: 10.1038/nrm2938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zachara NE, O’Donnell N, Cheung WD, Mercer JJ, Marth JD, Hart GW. Dynamic O-GlcNAc modification of nucleocytoplasmic proteins in response to stress. A survival response of mammalian cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. [Online] 2004;279(29): 30133–30142. Available from: doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403773200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groves JA, Lee A, Yildirir G, Zachara NE. Dynamic O-GlcNAcylation and its roles in the cellular stress response and homeostasis. Cell Stress and Chaperones. [Online] 2013;18(5): 535–558. Available from: doi: 10.1007/s12192-013-0426-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee A, Miller D, Henry R, Paruchuri VDP, O’Meally RN, Boronina T, et al. Combined Antibody/Lectin-Enrichment Identifies Extensive Changes in the O-GlcNAc Sub-proteome Upon Oxidative Stress. Journal of Proteome Research. [Online] 2016. Available from: doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teo CF, Ingale S, Wolfert MA, Elsayed GA, Nöt LG, Chatham JC, et al. glycopeptide-specific monoclonal antibodies suggest new roles for O-glcnac Nature Methods. [Online] Nature Publishing Group; 2010;6(5): 338–343. Available from: doi: 10.1038/nchembio.338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laczy B, Marsh SA, Brocks CA, Wittmann I, Chatham JC. Inhibition of O-GlcNAcase in perfused rat hearts by NAG-thiazolines at the time of reperfusion is cardioprotective in an O-GlcNAc-dependent manner. AJP: Heart and Circulatory Physiology. [Online] 2010;299(5): H1715–H1727. Available from: doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00337.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ngoh GA, Watson LJ, Facundo HT, Jones SP. Augmented O-GlcNAc signaling attenuates oxidative stress and calcium overload in cardiomyocytes. Amino acids. [Online] 2010;40(3): 895–911. Available from: doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0728-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fulop N, Zhang Z, Marchase RB, Chatham JC. Glucosamine cardioprotection in perfused rat hearts associated with increased O-linked N-acetylglucosamine protein modification and altered p38 activation. AJP: Heart and Circulatory Physiology. [Online] 2007;292(5): H2227–H2236. Available from: doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01091.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y-J, Huang Y-S, Chen J-T, Chen Y-H, Tai M-C, Chen C-L, et al. Protective effects of glucosamine on oxidative-stress and ischemia/reperfusion-induced retinal injury. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. [Online] 2015;56(3): 1506–1516. Available from: doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zachara NE, Molina H, Wong KY, Pandey A, Hart GW. The dynamic stress-induced ‘O-GlcNAc-ome’ highlights functions for O-GlcNAc in regulating DNA damage/repair and other cellular pathways. Amino acids. [Online] 2011;40(3): 793–808. Available from: doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0695-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones SP, Zachara NE, Ngoh GA, Hill BG, Teshima Y, Bhatnagar A, et al. Cardioprotection by N-acetylglucosamine linkage to cellular proteins. Circulation. [Online] 2008;117(9): 1172–1182. Available from: doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.730515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart GW, Slawson C, Ramirez-Correa G, Lagerlof O. Cross talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annual review of biochemistry. [Online] 2011;80: 825–858. Available from: doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060608-102511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis BA, Hanover JA. O-GlcNAc and the Epigenetic Regulation of Gene Expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry. [Online] 2014;289(50): 34440–34448. Available from: doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.595439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Love DC, Kochan J, Cathey RL, Shin SH, Hanover JA, Kochran J. Mitochondrial and nucleocytoplasmic targeting of O-linked GlcNAc transferase. Journal of Cell Science. 2003;116(Pt 4): 647–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanover JA, Yu S, Lubas WB, Shin SH, Ragano-Caracciola M, Kochran J, et al. Mitochondrial and nucleocytoplasmic isoforms of O-linked GlcNAc transferase encoded by a single mammalian gene. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2003;409(2): 287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreppel LK, Blomberg MA, Hart GW. Dynamic glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. Cloning and characterization of a unique O-GlcNAc transferase with multiple tetratricopeptide repeats. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272(14): 9308–9315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lubas WA, Frank DW, Krause M, Hanover JA. O-Linked GlcNAc transferase is a conserved nucleocytoplasmic protein containing tetratricopeptide repeats. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272(14): 9316–9324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jínek M, Rehwinkel J, Lazarus BD, Izaurralde E, Hanover JA, Conti E. The superhelical TPR-repeat domain of O-linked GlcNAc transferase exhibits structural similarities to importin α. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. [Online] 2004;11(10): 1001–1007. Available from: doi: 10.1038/nsmb833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazarus MB, Nam Y, Jiang J, Sliz P, Walker S. Structure of human O-GlcNAc transferase and its complex with a peptide substrate. Nature. [Online] 2011;469(7331): 564–567. Available from: doi: 10.1038/nature09638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheung WD, Hart GW. AMP-activated protein kinase and p38 MAPK activate O-GlcNAcylation of neuronal proteins during glucose deprivation. The Journal of biological chemistry. [Online] 2008;283(19): 13009–13020. Available from: doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801222200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung WD, Sakabe K, Housley MP, Dias WB, Hart GW. O-Linked -N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase Substrate Specificity Is Regulated by Myosin Phosphatase Targeting and Other Interacting Proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. [Online] 2008;283(49): 33935–33941. Available from: doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806199200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreppel LK, Hart GW. Regulation of a cytosolic and nuclear O-GlcNAc transferase. Role of the tetratricopeptide repeats. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274(45): 32015–32022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lubas WA. Functional Expression of O-linked GlcNAc Transferase. DOMAIN STRUCTURE AND SUBSTRATE SPECIFICITY. Journal of Biological Chemistry. [Online] 2000;275(15): 10983–10988. Available from: doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lazarus BD. Recombinant O-GlcNAc transferase isoforms: identification of O-GlcNAcase, yes tyrosine kinase, and tau as isoform-specific substrates. Glycobiology. [Online] 2006;16(5): 415–421. Available from: doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kazemi Z, Chang H, Haserodt S, McKen C, Zachara NE. O-Linked -N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) Regulates Stress-induced Heat Shock Protein Expression in a GSK-3 -dependent Manner. Journal of Biological Chemistry. [Online] 2010;285(50): 39096–39107. Available from: doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.131102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen RV, Zachara NE, Nielsen PH, Kimose HH, Kristiansen SB, Bøtker HE. Impact of O-GlcNAc on cardioprotection by remote ischaemic preconditioning in non-diabetic and diabetic patients. Cardiovascular research. [Online] 2013;97(2): 369–378. Available from: doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen RV, Johnsen J, Kristiansen SB, Zachara NE, Bøtker HE. Ischemic preconditioning increases myocardial O-GlcNAc glycosylation. Scandinavian cardiovascular journal : SCJ. [Online] 2013;47(3): 168–174. Available from: doi: 10.3109/14017431.2012.756984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo P, He T, Jiang R, Li G. MicroRNA-423-5p targets O-GlcNAc transferase to induce apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. Molecular medicine reports. [Online] 2015;12(1): 1163–1168. Available from: doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tai H-C, Khidekel N, Ficarro SB, Peters EC, Hsieh-Wilson LC. Parallel identification of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins from cell lysates. Journal of the American Chemical Society. [Online] 2004;126(34): 10500–10501. Available from: doi: 10.1021/ja047872b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bullen JW, Balsbaugh JL, Chanda D, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Neumann D, et al. Cross-talk between two essential nutrient-sensitive enzymes: O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). The Journal of biological chemistry. [Online] 2014;289(15): 10592–10606. Available from: doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.523068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee E, Kim EY. A role for timely nuclear translocation of clock repressor proteins in setting circadian clock speed. Experimental neurobiology. [Online] 2014;23(3): 191–199. Available from: doi: 10.5607/en.2014.23.3.191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryu I-H, Do S-I. Denitrosylation of S-nitrosylated OGT is triggered in LPS-stimulated innate immune response. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. [Online] 2011;408(1): 52–57. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan X, Wilson M, Mirbahai L, McConville C, Arvanitis TN, Griffin JL, et al. In vitro metabonomic study detects increases in UDP-GlcNAc and UDP-GalNAc, as early phase markers of cisplatin treatment response in brain tumor cells. Journal of Proteome Research. [Online] 2011;10(8): 3493–3500. Available from: doi: 10.1021/pr200114v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang S, Zou L-Y, Bounelis P, Chaudry I, Chatham JC, Marchase RB. Glucosamine administration during resuscitation improves organ function after trauma hemorrhage. Shock (Augusta, Ga.). [Online] 2006;25(6): 600–607. Available from: doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000209563.07693.db [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang ZV, Deng Y, Gao N, Pedrozo Z, Li DL, Morales CR, et al. Spliced X-box binding protein 1 couples the unfolded protein response to hexosamine biosynthetic pathway. Cell. [Online] 2014;156(6): 1179–1192. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zachara NE, Hart GW. Cell signaling, the essential role of O-GlcNAc! Biochimica et biophysica acta. [Online] 2006;1761(5–6): 599–617. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Itkonen HM, Engedal N, Babaie E, Luhr M, Guldvik IJ, Minner S, et al. UAP1 is overexpressed in prostate cancer and is protectiveagainst inhibitors of. Nature Publishing Group; 2014;34(28): 3744–3750. Available from: doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong DL, Hart GW. Purification and characterization of an O-GlcNAc selective N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase from rat spleen cytosol. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269(30): 19321–19330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao Y, Wells L, Comer FI, Parker GJ, Hart GW. Dynamic O-glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins: cloning and characterization of a neutral, cytosolic beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase from human brain. The Journal of biological chemistry. [Online] 2001;276(13): 9838–9845. Available from: doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010420200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wells L, Gao Y, Mahoney JA, Vosseller K, Chen C, Rosen A, et al. Dynamic O-glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins: further characterization of the nucleocytoplasmic beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase, O-GlcNAcase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277(3): 1755–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keembiyehetty CN, Krzeslak A, Love DC, Hanover JA. A lipid-droplet-targeted O-GlcNAcase isoform is a key regulator of the proteasome. Journal of Cell Science. [Online] 2011;124(16): 2851–2860. Available from: doi: 10.1242/jcs.083287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banerjee PS, Ma J, Hart GW. Diabetes-associated dysregulation of O-GlcNAcylation in rat cardiac mitochondria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [Online] 2015;112(19): 6050–6055. Available from: doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424017112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Butkinaree C, Cheung WD, Park S, Park K, Barber M, Hart GW. Characterization of beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase cleavage by caspase-3 during apoptosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. [Online] 2008;283(35): 23557–23566. Available from: doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804116200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khidekel N, Ficarro SB, Clark PM, Bryan MC, Swaney DL, Rexach JE, et al. Probing the dynamics of O-GlcNAc glycosylation in the brain using quantitative proteomics. Nature Chemical Biology. [Online] 2007;3(6): 339–348. Available from: doi: 10.1038/nchembio881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hornbeck PV, Kornhauser JM, Tkachev S, Zhang B, Skrzypek E, Murray B, et al. PhosphoSitePlus: a comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Research. [Online] 2012;40(Database issue): D261–D270. Available from: doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lundby A, Lage K, Weinert BT, Bekker-Jensen DB, Secher A, Skovgaard T, et al. Proteomic analysis of lysine acetylation sites in rat tissues reveals organ specificity and subcellular patterns. Cell reports. [Online] 2012;2(2): 419–431. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner SA, Beli P, Weinert BT, Nielsen ML, Cox J, Mann M, et al. A proteome-wide, quantitative survey of in vivo ubiquitylation sites reveals widespread regulatory roles. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. [Online] 2011;10(10): M111.013284. Available from: doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.013284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharma K, D’Souza RCJ, Tyanova S, Schaab C, Wisniewski JR, Cox J, et al. Ultradeep human phosphoproteome reveals a distinct regulatory nature of Tyr and Ser/Thr-based signaling. Cell reports. [Online] 2014;8(5): 1583–1594. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muthusamy S, DeMartino AM, Watson LJ, Brittian KR, Zafir A, Dassanayaka S, et al. MicroRNA-539 is up-regulated in failing heart, and suppresses O-GlcNAcase expression. The Journal of biological chemistry. [Online] 2014;289(43): 29665–29676. Available from: doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.578682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kregel KC. Heat shock proteins: modifying factors in physiological stress responses and acquired thermotolerance. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). [Online] 2002;92(5): 2177–2186. Available from: doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01267.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xavier IJ, Mercier PA, McLoughlin CM, Ali A, Woodgett JR, Ovsenek N. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta negatively regulates both DNA-binding and transcriptional activities of heat shock factor 1. The Journal of biological chemistry. [Online] 2000;275(37): 29147–29152. Available from: doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002169200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang X, Grammatikakis N, Siganou A, Calderwood SK. Regulation of molecular chaperone gene transcription involves the serine phosphorylation, 14-3-3 epsilon binding, and cytoplasmic sequestration of heat shock factor 1. Molecular and cellular biology. 2003;23(17): 6013–6026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singleton KD, Wischmeyer PE. Glutamine induces heat shock protein expression via O-glycosylation and phosphorylation of HSF-1 and Sp1. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition. [Online] 2008;32(4): 371–376. Available from: doi: 10.1177/0148607108320661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamiel CR, Pinto S, Hau A, Wischmeyer PE. Glutamine enhances heat shock protein 70 expression via increased hexosamine biosynthetic pathway activity. AJP: Cell Physiology. [Online] 2009;297(6): C1509–C1519. Available from: doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00240.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lim K-H, Chang H-I. O-linked N-acetylglucosamine suppresses thermal aggregation of Sp1. FEBS letters. [Online] 2006;580(19): 4645–4652. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.07.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sohn K-C, Lee K-Y, Park JE, Do S-I. OGT functions as a catalytic chaperone under heat stress response: a unique defense role of OGT in hyperthermia. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. [Online] 2004;322(3): 1045–1051. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ku N-O, Toivola DM, Strnad P, Omary MB. Cytoskeletal keratin glycosylation protects epithelial tissue from injury Nature Publishing Group. [Online] Nature Publishing Group; 2010;12(9): 876–885. Available from: doi: 10.1038/ncb2091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krishnamoorthy V, Donofrio AJ, Martin JL. O-GlcNAcylation of αB-crystallin regulates its stress-induced translocation and cytoprotection. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. [Online] 2013;379(1-2): 59–68. Available from: doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1627-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu Y, Liu T-W, Cecioni S, Eskandari R, Zandberg WF, Vocadlo DJ. O-Glcnac occurs cotranslationally to stabilize nascent polypeptide chains Nature Chemical Biology. [Online] Nature Publishing Group; 2015;11(5): 319–325. Available from: doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Irvine GB, El-Agnaf OM, Shankar GM, Walsh DM. Protein aggregation in the brain: the molecular basis for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Molecular medicine (Cambridge, Mass.). [Online] 2008;14(7–8): 451–464. Available from: doi: 10.2119/2007-00100.Irvine [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Z, Udeshi ND, O’Malley M, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Hart GW. Enrichment and site mapping of O-linked N-acetylglucosamine by a combination of chemical/enzymatic tagging, photochemical cleavage, and electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. [Online] 2010;9(1): 153–160. Available from: doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900268-MCP200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alfaro JF, Gong C-X, Monroe ME, Aldrich JT, Clauss TRW, Purvine SO, et al. Tandem mass spectrometry identifies many mouse brain O-GlcNAcylated proteins including EGF domain-specific O-GlcNAc transferase targets. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. [Online] 2012;109(19): 7280–7285. Available from: doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200425109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Z, Park K, Comer F, Hsieh-Wilson LC, Saudek CD, Hart GW. Site-specific GlcNAcylation of human erythrocyte proteins: potential biomarker(s) for diabetes. Diabetes. [Online] 2009;58(2): 309–317. Available from: doi: 10.2337/db08-0994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marotta NP, Lin YH, Lewis YE, Ambroso MR, Zaro BW, Roth MT, et al. O-GlcNAc modification blocks the aggregation and toxicity of the protein α-synuclein associated with Parkinson’s disease. Nature chemistry. [Online] 2015;7(11): 913–920. Available from: doi: 10.1038/nchem.2361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yuzwa SA, Cheung AH, Okon M, McIntosh LP, Vocadlo DJ. O-GlcNAc Modification of tau Directly Inhibits Its Aggregation without Perturbing the Conformational Properties of tau Monomers Journal of Molecular Biology. [Online] Elsevier Ltd; 2014;426(8): 1736–1752. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yuzwa SA, Shan X, Macauley MS, Clark T, Skorobogatko Y, Vosseller K, et al. Increasing O-GlcNAc slows neurodegeneration and stabilizes tau against aggregation. Nature Chemical Biology. [Online] 2012;8(4): 393–399. Available from: doi: 10.1038/nchembio.797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ngoh GA, Watson LJ, Facundo HT, Dillmann W, Jones SP. Non-canonical glycosyltransferase modulates post-hypoxic cardiac myocyte death and mitochondrial permeability transition. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. [Online] 2008;45(2): 313–325. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ngoh GA, Facundo HT, Hamid T, Dillmann W, Zachara NE, Jones SP. Unique Hexosaminidase Reduces Metabolic Survival Signal and Sensitizes Cardiac Myocytes to Hypoxia/Reoxygenation Injury. Circulation research. [Online] 2008;104(1): 41–49. Available from: doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.189431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tabas I, Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nature Cell Biology. [Online] 2011;13(3): 184–190. Available from: doi: 10.1038/ncb0311-184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ngoh GA, Hamid T, Prabhu SD, Jones SP. O-GlcNAc signaling attenuates ER stress-induced cardiomyocyte death. AJP: Heart and Circulatory Physiology. [Online] 2009;297(5): H1711–H1719. Available from: doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00553.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Suh HN, Lee YJ, Kim MO, Ryu JM, Han HJ. Glucosamine-Induced Sp1 O-GlcNAcylation Ameliorates Hypoxia-Induced SGLT Dysfunction in Primary Cultured Renal Proximal Tubule Cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology. [Online] 2014;229(10): 1557–1568. Available from: doi: 10.1002/jcp.24599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jang I, Kim HB, Seo H, Kim JY, Choi H, Yoo JS, et al. O-GlcNAcylation of eIF2α regulates the phospho-eIF2α-mediated ER stress response. Biochimica et biophysica acta. [Online] 2015;1853(8): 1860–1869. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ferrer CM, Lynch TP, Sodi VL, Falcone JN, Schwab LP, Peacock DL, et al. O-GlcNAcylation Regulates Cancer Metabolism and Survival Stress Signalingvia Regulation of the HIF-1 Pathway MOLCEL. [Online] Elsevier Inc; 2014;54(5): 820–831. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kedersha N, Anderson P. Mammalian stress granules and processing bodies. Methods in enzymology. [Online] 2007;431: 61–81. Available from: doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)31005-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ohn T, Kedersha N, Hickman T, Tisdale S, Anderson P. A functional RNAi screen links O-GlcNAc modification of ribosomal proteins to stress granule and processing body assembly. Nature Cell Biology. [Online] 2008;10(10): 1224–1231. Available from: doi: 10.1038/ncb1783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature. [Online] 2008;454(7203): 455–462. Available from: doi: 10.1038/nature07203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Black PH. The inflammatory response is an integral part of the stress response: Implications for atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, type II diabetes and metabolic syndrome X. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2003;17(5): 350–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pathak S, Borodkin VS, Albarbarawi O, Campbell DG, Ibrahim A, van Aalten DM. O-GlcNAcylation of TAB1 modulates TAK1-mediated cytokine release. The EMBO journal. [Online] 2012;31(6): 1394–1404. Available from: doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shim J-H, Xiao C, Paschal AE, Bailey ST, Rao P, Hayden MS, et al. TAK1, but not TAB1 or TAB2, plays an essential role in multiple signaling pathways in vivo. Genes & Development. [Online] 2005;19(22): 2668–2681. Available from: doi: 10.1101/gad.1360605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sato S, Sanjo H, Takeda K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Yamamoto M, Kawai T, et al. Essential function for the kinase TAK1 in innate and adaptive immune responses. Nature immunology. [Online] 2005;6(11): 1087–1095. Available from: doi: 10.1038/ni1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang C, Deng L, Hong M, Akkaraju GR, Inoue J, Chen ZJ. TAK1 is a ubiquitin-dependent kinase of MKK and IKK. Nature. [Online] 2001;412(6844): 346–351. Available from: doi: 10.1038/35085597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nöt LG, Brocks CA, Vámhidy L, Marchase RB, Chatham JC. Increased O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine levels on proteins improves survival, reduces inflammation and organ damage 24 hours after trauma-hemorrhage in rats. Critical care medicine. [Online] 2010;38(2): 562–571. Available from: doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb10b3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zou L, Yang S, Hu S, Chaudry IH, Marchase RB, Chatham JC. The protective effects of PUGNAc on cardiac function after trauma-hemorrhage are mediated via increased protein O-GlcNAc levels. Shock (Augusta, Ga.). [Online] 2007;27(4): 402–408. Available from: doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000245031.31859.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xing D, Gong K, Feng W, Nozell SE, Chen Y-F, Chatham JC, et al. O-GlcNAc Modification of NFκB p65 Inhibits TNF-α-Induced Inflammatory Mediator Expression in Rat Aortic Smooth Muscle Cells Stadler K (ed.) PLoS ONE. [Online] 2011;6(8): e24021. Available from: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024021.s001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hilgers RHP, Xing D, Gong K, Chen Y-F, Chatham JC, Oparil S. Acute O-GlcNAcylation prevents inflammation-induced vascular dysfunction. AJP: Heart and Circulatory Physiology. [Online] 2012;303(5): H513–H522. Available from: doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01175.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xing D, Feng W, Nöt LG, Miller AP, Zhang Y, Chen Y-F, et al. Increased protein O-GlcNAc modification inhibits inflammatory and neointimal responses to acute endoluminal arterial injury. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. [Online] 2008;295(1): H335–H342. Available from: doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01259.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yi W, Clark PM, Mason DE, Keenan MC, Hill C, Goddard WA, et al. Phosphofructokinase 1 Glycosylation Regulates Cell Growth and Metabolism. Science. [Online] 2012;337(6097): 975–980. Available from: doi: 10.1126/science.1222278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rao X, Duan X, Mao W, Li X, Li Z, Li Q, et al. O-GlcNAcylation of G6PD promotes the pentose phosphate pathway and tumor growth Nature Communications. [Online] Nature Publishing Group; 1AD;6: 1–10. Available from: doi: 10.1038/ncomms9468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Taparra K, Tran PT, Zachara NE. Hijacking the Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway to Promote EMT-Mediated Neoplastic Phenotypes. Frontiers in Oncology. [Online] 2016;6: 85. Available from: doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu J, Marchase RB, Chatham JC. Increased O-GlcNAc levels during reperfusion lead to improved functional recovery and reduced calpain proteolysis. AJP: Heart and Circulatory Physiology. [Online] 2007;293(3): H1391–H1399. Available from: doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00285.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Watson LJ, Facundo HT, Ngoh GA, Ameen M, Brainard RE, Lemma KM, et al. O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase is indispensable in the failing heart. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. [Online] 2010;107(41): 17797–17802. Available from: doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001907107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yuzwa SA, Macauley MS, Heinonen JE, Shan X, Dennis RJ, He Y, et al. A potent mechanism-inspired O-GlcNAcase inhibitor that blocks phosphorylation of tau in vivo. Nature Chemical Biology. [Online] 2008;4(8): 483–490. Available from: doi: 10.1038/nchembio.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Champattanachai V, Marchase RB, Chatham JC. Glucosamine protects neonatal cardiomyocytes from ischemia-reperfusion injury via increased protein-associated O-GlcNAc. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology. [Online] 2007;292(1): C178–C187. Available from: doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00162.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zou L, Yang S, Champattanachai V, Hu S, Chaudry IH, Marchase RB, et al. Glucosamine improves cardiac function following trauma-hemorrhage by increased protein O-GlcNAcylation and attenuation of NF- B signaling. AJP: Heart and Circulatory Physiology. [Online] 2008;296(2): H515–H523. Available from: doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01025.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim D-H, Seok Y-M, Kim I-K, Lee I-K, Jeong S-Y, Jeoung N-H. Glucosamine increases vascular contraction through activation of RhoA/Rho kinase pathway in isolated rat aorta. BMB Reports. [Online] 2011;44(6): 415–420. Available from: doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2011.44.6.415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu J, Marchase RB, Chatham JC. Glutamine-induced protection of isolated rat heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury is mediated via the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway and increased protein O-GlcNAc levels. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. [Online] 2007;42(1): 177–185. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Aghazadeh-Habashi A, Jamali F. The glucosamine controversy; a pharmacokinetic issue. Journal of pharmacy & pharmaceutical sciences : a publication of the Canadian Society for Pharmaceutical Sciences, Societe canadienne des sciences pharmaceutiques. 2011;14(2): 264–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chun W-J, Nah D-Y, Bae J-H, Chung J-W, Lee H, Moon IS. Glucose-Insulin-Potassium Solution Protects Ventricular Myocytes of Neonatal Rat in an In VitroCoverslip Ischemia/Reperfusion Model. Korean Circulation Journal. [Online] 2015;45(3): 234. Available from: doi: 10.4070/kcj.2015.45.3.234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lima VV, Rigsby CS, Hardy DM, Webb RC, Tostes RC. O-GlcNAcylation: a novel post-translational mechanism to alter vascular cellular signaling in health and disease: focus on hypertension. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension : JASH. [Online] 2009;3(6): 374–387. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2009.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lunde IG, Aronsen JM, Kvaloy H, Qvigstad E, Sjaastad I, Tonnessen T, et al. Cardiac O-GlcNAc signaling is increased in hypertrophy and heart failure. Physiological Genomics. [Online] 2012;44(2): 162–172. Available from: doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00016.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Erickson JR, Pereira L, Wang L, Han G, Ferguson A, Dao K, et al. Diabetic hyperglycaemia activates CaMKII and arrhythmias by O-linked glycosylation. Nature. [Online] 2013;502(7471): 372–376. Available from: doi: 10.1038/nature12537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Roth DM, Hutt DM, Tong J, Bouchecareilh M, Wang N, Seeley T, et al. Modulation of the Maladaptive Stress Response to Manage Diseases of Protein Folding Hartl U (ed.) PLoS Biology. [Online] 2014;12(11): e1001998. Available from: doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001998.s008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liu S, Sheng H, Yu Z, Paschen W, Yang W. O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine modification of proteins is activated in post-ischemic brains of young but not aged mice: Implications for impaired functional recovery from ischemic stress. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. [Online] 2016;36(2): 393–398. Available from: doi: 10.1177/0271678X15608393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Reeves RA, Lee A, Henry R, Zachara NE. Analytical Biochemistry Analytical Biochemistry. [Online] Elsevier Inc; 2014;457(C): 8–18. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2014.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Guinez C, Mir A-M, Leroy Y, Cacan R, Michalski J-C, Lefebvre T. Hsp70-GlcNAc-binding activity is released by stress, proteasome inhibition, and protein misfolding. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. [Online] 2007;361(2): 414–420. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zafir A, Readnower R, Long BW, McCracken J, Aird A, Alvarez A, et al. Protein O-GlcNAcylation Is a Novel Cytoprotective Signal in Cardiac Stem Cells. STEM CELLS. [Online] 2013;31(4): 765–775. Available from: doi: 10.1002/stem.1325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Liu G, Xu C, Feng L, Wang F. The augmentation of O-GlcNAcylation reduces glyoxal-induced cell injury by attenuating oxidative stress in human retinal microvascular endothelial cells. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. [Online] 2015. Available from: doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Srikanth B, Vaidya MM, Kalraiya RD. O-GlcNAcylation Determines the Solubility, Filament Organization, and Stability of Keratins 8 and 18. Journal of Biological Chemistry. [Online] 2010;285(44): 34062–34071. Available from: doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.098996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lee HJ, Ryu JM, Jung YH, Lee KH, Kim DI, Han HJ. Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase-1 upregulation by O-GlcNAcylation of Sp1 protects against hypoxia-induced mouse embryonic stem cell apoptosis via mTOR activation. Nature Publishing Group; 2016;7(3): e2158–13. Available from: doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kommaddi RP, Dickson KM, Barker PA. Stress-induced expression of the p75 neurotrophin receptor is regulated by O-GlcNAcylation of the Sp1 transcription factor. Journal of Neurochemistry. [Online] 2011;116(3): 396–405. Available from: doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07120.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Herzog R, Bender TO, Vychytil A, Bialas K, Aufricht C, Kratochwill K. Dynamic O-Linked N-Acetylglucosamine Modification of Proteins Affects Stress Responses and Survival of Mesothelial Cells Exposed to Peritoneal Dialysis Fluids. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. [Online] 2014;25(12): 2778–2788. Available from: doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013101128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Miura Y, Sakurai Y, Endo T. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta BBA - General Subjects. [Online] Elsevier B.V; 2012;1820(10): 1678–1685. Available from: doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]