Abstract

Introduction:

The postpartum period represents the time of risk for the emergence of maternal postpartum depression. There are no systematic reviews of the overall maternal outcomes of maternal postpartum depression. The aim of this study was to evaluate both the infant and the maternal consequences of untreated maternal postpartum depression.

Methods:

We searched for studies published between 1 January 2005 and 17 August 2016, using the following databases: MEDLINE via Ovid, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group trials registry.

Results:

A total of 122 studies (out of 3712 references retrieved from bibliographic databases) were included in this systematic review. The results of the studies were synthetized into three categories: (a) the maternal consequences of postpartum depression, including physical health, psychological health, relationship, and risky behaviors; (b) the infant consequences of postpartum depression, including anthropometry, physical health, sleep, and motor, cognitive, language, emotional, social, and behavioral development; and (c) mother–child interactions, including bonding, breastfeeding, and the maternal role.

Discussion:

The results suggest that postpartum depression creates an environment that is not conducive to the personal development of mothers or the optimal development of a child. It therefore seems important to detect and treat depression during the postnatal period as early as possible to avoid harmful consequences.

Keywords: infant outcomes, maternal outcomes, maternal postpartum depression, mother–infant interactions, systematic review

Introduction

Pregnancy and childbirth are two major events in a woman’s life. The birth of a baby induces sudden and intense changes in a woman’s roles and responsibilities. Thus, the postpartum period represents the time of risk for the emergence of maternal postpartum depression (PPD).1 PPD is a serious mental health problem. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV) defines PPD as a specifier for major depressive disorder (MDD).2 PPD is also defined symptomatically as exceeding a given threshold on a screening measure, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).3,4 In general, PPD occurs within 4 to 6 weeks after childbirth, and symptoms similar to MDD that may be present include depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure in activities, sleep disturbance, appetite disturbance, loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, diminished concentration, irritability, anxiety, and thoughts of suicide.5

The prevalence of PPD varies substantially depending on the definition of the disorder, country, diagnostic tools used, threshold of discrimination chosen for the screening measure, and period over which the prevalence is determined.3,6 For example, Halbreich and Karkun7 performed a review of the literature and found a PPD prevalence that varied between 0.5% and 60% among countries, as estimated by the self-reported 10-item EPDS questionnaire. The prevalence of PPD varies from 1.9% to 82.1% in developed countries, with the lowest prevalence reported in Germany and the highest prevalence in the United States.7,8 In developing countries, the prevalence varies from 5.2% to 74.0%, with the lowest prevalence reported in Pakistan and the highest prevalence in Turkey.8 This tremendous variation in the prevalence of PPD could be explained by heterogeneous study designs or the use of different diagnostic tools (e.g. the EPDS, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), or Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)).9

Untreated PPD seems to have negative consequences for both infants and mothers. Nonsystematic reviews have indicated that the risks to children of untreated depressed mothers (compared to mothers without PPD) include problems such as poor cognitive functioning, behavioral inhibition, emotional maladjustment, violent behavior, externalizing disorders, and psychiatric and medical disorders in adolescence.5,10–17 These nonsystematic reviews reported the outcomes of these children from birth to adolescence. Other nonsystematic and systematic reviews have also explored specific maternal risks when mothers’ PPD is untreated, including more weight problems,18,19 alcohol and illicit drug use,20 social relationship problems,21 breastfeeding problems,22 or persistent depression23 compared with women who have received treatment. Nevertheless, there are no well-established systematic reviews of the overall maternal and/or infant outcomes of maternal PPD. Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate all the maternal consequences of untreated PPD and its effects on children between 0 and 3 years of age.

Methods

To the extent possible, this research adhered to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement.24

Search strategy

We searched for all studies published between 1 January 2005 and 17 August 2016, using the following databases: MEDLINE via Ovid, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group trials registry. The following keywords were applied in the databases during the literature search: “postpartum depression” OR “postnatal depression” OR “puerperal depression.” The research was limited to human studies published in the English language. The search strategy and search terms used for this research are detailed in Appendix 1. Additional studies were identified through a manual search of the bibliographic references of the relevant articles and existing reviews.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) cohort and cross-sectional epidemiological and qualitative individual studies; (b) studies that included mothers of all ages who suffered from PPD (all combinations of comparison groups were possible: PPD vs no PPD, severe PPD vs mild PPD, etc.); and (c) studies that included health (physical or psychological) or social outcomes of PPD in the results.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) meta-analyses, systematic and nonsystematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, and case studies; and (b) studies that included mothers who received treatment for PPD. Meta-analyses and systematic and nonsystematic reviews were only accessed to review their bibliographic references.

It is also important to note that there are many factors (e.g. comorbid conditions (anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, or substance abuse), socioeconomic status, education level, co- or single-parenting, and number of previous pregnancies) that could play an important role in the experience of PPD. Nevertheless, in the present systematic review, these factors were not considered as exclusion criteria; instead, they were treated as potential confounding factors. Moreover, because these confounding factors are difficult to account for in a systematic review, the adjusted results were used and discussed in this article when available.

After duplicates were removed, studies identified by the search strategy were exported to an Excel spreadsheet for study selection.

Study selection

In the first step, two investigators performed the study selection and assessed the titles and abstracts of the studies to exclude articles that were immaterial to the systematic review based on the inclusion criteria. In the second step, the same two investigators selected, read and evaluated the full-text studies that met the inclusion criteria. Given the large number of abstracts and full-text articles that needed to be read, the two investigators selected the studies independently.

Data extraction

The studies were divided between the two investigators for data extraction. However, if there was doubt regarding an article, the article was discussed by the two investigators, and a consensus was reached. The two investigators extracted the data from the selected studies according to a standardized data extraction form. The following data were isolated for each study: authors; journal name; year of publication; country of origin; objective of the study; study population data (type of population, mean age, sex ratio of the children, and age, if provided); sample size; design (length of intervention, number of groups, and description of groups); tools used to assess maternal PPD; reported prevalence of maternal PPD; types of infant and/or maternal outcomes and main (adjusted) results; and conclusion. To ensure that as many studies as possible were included in our systematic review, we systematically contacted the authors or co-authors when the full-text paper was not available.

Analysis and synthesis of the results

To facilitate data extraction, the included studies were initially grouped according to three types of outcomes: physical (e.g. weight, length, anthropometric indices, motor development, and physical health); psychological (e.g. mental health, cognitive development, language development, and bonding); or “other” (e.g. social relationships, quality of life, breastfeeding, and risky behaviors). Each outcome group was then thematically analyzed, coded by topic, and divided into more appropriate subgroups. The outcome subgroups were based on information obtained from the studies included in this review. In terms of the studies’ outcomes, key words were labeled and classified into groups with similar consequences. For example, the subcategories “weight,” “length,” and “anthropometric indices” were combined into the more general category of “anthropometry.”

This systematic review of the literature used a narrative synthesis methodology. Each included study was described in a commentary that reported the findings. Similarities and differences among the studies were also synthesized to draw conclusions within the subgroups.

Results

Included studies

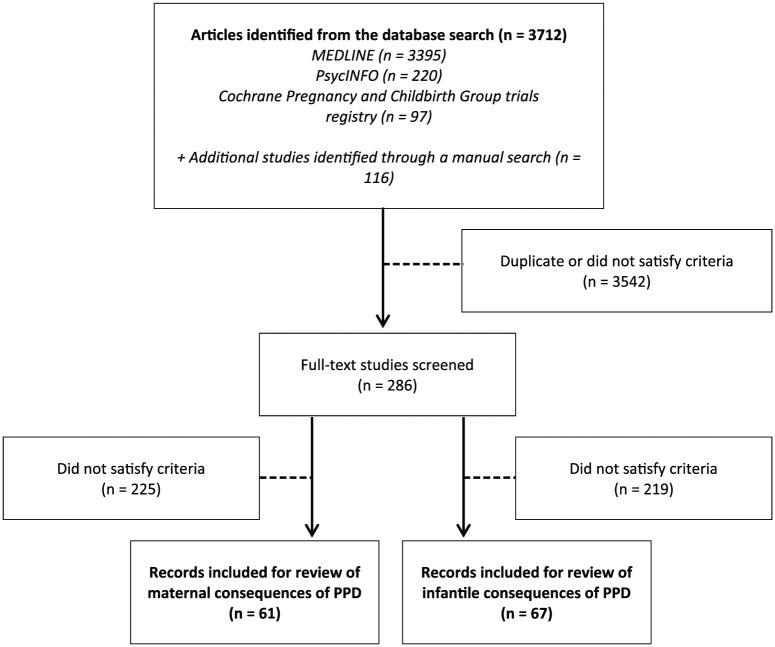

Of the 3712 references retrieved from the bibliographic databases (Figure 1), we identified 122 eligible studies that evaluated the consequences of PPD: 68 that evaluated the maternal consequences and 73 that evaluated the infant consequences. Among the included studies, 19 examined both the infant and the maternal consequences of PPD.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the selection of relevant literature.

The group of studies that evaluated the maternal consequences of PPD included 46 cohort studies25–72 and 21 cross sectional studies73–92 (including 1 qualitative study).93 The majority of the studies were performed in the United States (28 of 68) and Europe (22 of 68), 10 studies were performed in Asia, and 8 studies were performed in Australia and New Zealand. All studies included women aged between 13 and 45 years. The number of participants ranged from 1593 to 22,118,28 and the duration of follow-up varied from 2 weeks32 to 6 years33 for the cohort studies.

PPD was mainly diagnosed according to the 10-item EPDS (46 studies); however, there were studies that used the BDI (6 studies), the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview—Short Form (CIDI-SF; 3 studies), the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; 3 studies), the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PDSS; 4 studies), and the CES-D (2 studies). To assess PPD, other studies used other questionnaires (e.g. the Patient Health Questionnaire depression module (PHQ-942 or PHQ-874), the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI),31 or the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS)30). The prevalence of PPD varied from 4.5% in a population of Canadian mothers at 6 weeks postpartum89 to 68.8% in a population of Australian mothers at 4 months postpartum.64

The group of studies that evaluated the infant consequences of PPD included 61 cohort studies31,34,37,45,48,49,52,53,56,64–66,69–72,94–138 and 12 cross-sectional studies.90–92,139–147 Most of the studies were performed in the United States (27 of 73) and Europe (20 of 73), 12 studies were performed in Asia, 10 studies were performed in Africa, and 4 studies were performed in Australia and New Zealand. All studies included women aged between 14 and 49 years and a percentage of baby girls that varied between 37.7%49 and 57.5%.147 The number of participants ranged from 28123 to 24,263,98 and the duration of follow-up varied from 2 months31,118,123 to 5 years96 for the cohort studies.

PPD was mainly diagnosed according to the 10-item EPDS (37 studies); however, there were studies that used the CES-D (9 studies), the BDI (7 studies), and the depression section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; 4 studies). To assess PPD, other studies used various types of questionnaires (e.g. the PHQ-9135,136 or the BSI100). Only one study did not specify the questionnaire that was used to detect PPD.98 The prevalence of PPD varied from 2.7% in a population of Pakistani mothers at 18 months postpartum94 to 68.8% in a population of Australian mothers at 4 months postpartum.64

The outcomes were separated into three sections: “maternal consequences of PPD,” “infant consequences of PPD,” and “mother–child interactions.” The first section, “maternal consequences of PPD,” reported results for 5 different types of outcomes: physical health (3 studies),35,67,88 including health care practices and utilization measures (2 studies);63,78 psychological health, including anxiety and depression (6 studies);36,37,42,44,66,88 quality of life (8 studies);27,37,39,48,66,85,86,88 relationships, including social relationships and relationships with the partner and sexuality (7 studies);37,38,44,66,73,74,85 and risky behaviors, including addictive behavior (smoking behavior and alcohol consumption: 4 studies)55,68,84,87 and suicidal ideation (7 studies).28,30,33,76,81,85,93 The second section, “infant consequences of PPD,” reported results for 9 different types of outcomes: anthropometry, including weight, length, and anthropometric indices (13 studies);97,100,104,109,110,112,113,119,125,126,131,140,142 infant health (10 studies);48,104,119,122–124,135,136,138,142 infant sleep (3 studies);104,108,130 motor development (7 studies);66,94,95,97,103,107,141 cognitive development (11 studies);94,95,99,101–103,107,134,139,141,147 language development (13 studies);66,94,95,102,103,105,116,117,129,131,132,139,141 emotional development (5 studies);94–96,115,121 social development (4 studies);66,115,141,143 and behavioral development (12 studies).49,52,96,110,111,114,115,120,121,131,133,141 Finally, the third section, “mother–child interactions,” reported results for 3 different types of outcomes: bonding and attachment, including mother-to-infant and infant-to-mother bonding (15 studies);29,31,34,37,43,44,47,52,54,56,61,64,82,106,127 breastfeeding (22 studies);25,26,32,41,45,59,60,62,65,69–72,77,89–92,118,119,130,137 and maternal role, including maternal behaviors (9 studies),26,40,49,52,53,62,79,83,85 maternal competence (2 studies),51,75 maternal care for the infant (6 studies),37,53,130,137,145,146 infant health care practices or utilization measures (8 studies),26,37,57,63,98,128,130,142 maternal perception of the infant’s patterns (5 studies),40,46,50,58,80 and the risk of maltreatment (2 studies).130,144

Maternal consequences of PPD

Physical health

Only three studies evaluated the physical health of depressed mothers (Table 1). One study found that compared to the general population of women, depressed mothers scored significantly lower on the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) physical component summary score (assessed based on physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, bodily pain, and general health perceptions).88 However, this study indicated that the severity of the depressed mood was not associated with a worse physical health status, whereas a worse aerobic capacity emerged as a significant independent contributor to physical health status. The two last studies evaluated postpartum weight retention (PPWR) and found that significantly more women with PPWR had higher scores on the PPD scale.35,67

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of maternal physical health.

| First author’s name | Sociodemographic data: 1. Country 2. Maternal mean age 3. Gender of newborns |

Sample size | Design: 1. Study design 2. Time of follow-up 3. Number of groups 4. Description of groups |

Tool used to assess PPD | Prevalence of PPD | Outcomes | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical health | |||||||

| Biesmans35 | Belgium Mean age: 30.1 ± 4.3 years Gender of newborns: not given |

75 | Cohort study 14 months Two groups: - PPWR - No PPWR |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 10) |

PPWR: 30.8% No PPWR: 8.3% |

PPWR | 52% of the women did not reach their pre-pregnancy weight 1 year after childbirth. Women with PPWR weighed approximately 2 (M = 2.3; SD = 2.8) kg above their weight from before the last pregnancy. There were significantly more women with higher scores on the PPD scale in the group with PPWR (p = 0.015). |

| Da Costa88 | Canada Mean age: 33.2 ± 4.6 years Gender of newborns: not given |

78 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 12) |

63% | Physical health status; mental health status; health-related quality of life | Compared to Canadian normative data, women experiencing postpartum depressed mood scored significantly lower on all SF-36 domains and on the SF-36 physical and mental component summary scores. Severity of depressed mood was not associated with worse physical health status, while poorer aerobic capacity emerged as a significant independent contributor of physical health status. |

| Herring67 | USA Mean age: 33.0 ± 4.7 years Gender of newborns: not given |

850 | Cohort study 18 months Four groups: - None - Pregnancy only - Postpartum only - Pregnancy and postpartum |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS > 12) |

4% | Risk of substantial weight retention | In multivariate logistic regression analyses, after adjustment for weight-related covariates, maternal sociodemographics, and parity, new-onset PPD was associated with more than double the risk of retaining at least 5 (OR = 2.54, 95% CI = 1.06, 6.09) kg. |

| Health care practices and utilization measures | |||||||

| Eilat-Tsanani63 | Israel Age: 18 years and above Gender of newborns: not given |

527 | Cohort study 2 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 13) (+survey) |

9.9% | Women’s’ consultations with physicians (family physicians, gynecologists, and/or pediatricians) | Women with PPD differed from those without PPD in terms of the frequency of and reasons for consultations. The rate of PPD was significantly higher in women who consulted for medical reasons than those who came for routine care (13% vs 4%, p = 0.001). Women with multiple visits (four or more) to all doctors had higher rates of PPD than the others (16.7% vs 7%, p = 0.002). Women with PPD consulted more with family physicians (20.6% vs 7.8%, p = 0.01) and pediatricians (18.3% vs 7.1%, p = 0.001). No significant difference in PPD rates was found in relation to the number of visits to gynecologists. |

| McCallum78 | Australia Mean age: 33.0 ± 4.5 years Gender of newborns: not given |

875 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS > 9) |

16.7% | Health service use | Poorer maternal mental health was also implicated with a one-point increase in the EPDS associated with a 4% (0.4%–8%) increase in the likelihood of using more than three services (adjusted for socioeconomic position, partner status, language, gestational age, and unsettled infant behavior). Women with worse depressive symptoms were more likely to consult a general practitioner or mental health professional, but not other services. |

PPD: postpartum depression; PPWR: postpartum weight retention; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; SD: standard deviation; SF-36: 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Health care practices and utilization measures

Two studies63,78 demonstrated an effect of maternal PPD on health care practices and utilization measures (Table 1). One of these studies demonstrated that women with worse depressive symptoms were more likely to consult a general practitioner or mental health professional than women with milder depressive symptoms.78 The other study showed that women with PPD consulted with family physicians more often than nondepressed mothers did.63

Psychological health

Six studies (Table 2) evaluated the association between PPD and psychological health; five studies focused on overall psychological health,37,42,44,66,88 two studies focused on anxiety,36,37 and three studies focused on depression.36,37,66

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of the maternal psychological health.

| First author’s name | Sociodemographic data: 1. Country 2. Maternal mean age 3. Gender of newborns |

Sample size | Design 1. Study design 2. Time of follow-up 3. Number of groups 4. Description of groups |

Tool used to assess PPD | Prevalence of PPD | Outcomes | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Da Costa88 | Canada Mean age: 33.2 ± 4.6 years Gender of newborns: not given |

78 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 10) |

63% (EPDS ⩾ 12) | Physical health status; mental health status; health-related quality of life | Depressed mood was a significant predictor (β = −0.44, p < 0.0001) of mental health status, explaining 18% of the variance. After controlling for depressed mood, the occurrence of pregnancy complications (p = 0.001), cesarean delivery (p = 0.005), poorer sleep quality (p = 0.009), lower perceived social support (p = 0.045), and greater life stress (p = 0.003) were significant independent determinants of worse mental health status. Together, the variables in the second step explained an additional 30% of the variance. |

| Gollan42 | USA Mean age (years): Depressed: 27.5 ± 6.8 Nondepressed: 30 ± 4.9 Gender of newborns: not given |

80 | Cohort study 15 weeks Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

DSM-IV PHQ-9 QIDS-SR |

33.8% | Affective reactivity (affective information processing) | Results of the GLM analyses of variance for postpartum ratings of valence and arousal revealed a significant main effect for group (p < 0.05) in which postpartum women with major depression demonstrated significantly lower arousal ratings for negative stimuli compared with healthy women (p < 0.001). In addition, postpartum women with major depression had significantly lower valence ratings for negative stimuli (p = 0.03) compared with healthy women. |

| Lilja44 | Sweden Mean age: 27.8 years Gender of newborns: not given |

419 | Cohort study 1 year Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 10) |

22.2% | Women’s mood over the first year postpartum; women’s relationship with their infant; women’s relationship with their partner | Mothers who scored high on the EPDS on day 10 rated their mood lower, for example, they reported being less happy and more dysphoric and sad than mothers who scored low on the EPDS. Significant positive correlations were found between the EPDS and the mood scale at day 3 (r = 0.355, p < 0.001), day 10 (r = 0.615, p < 0.001), 6 months (r = 0.349, p < 0.001), and 12 months (r = 0.370, p < 0.001). Thus, a moderately increased score on the EPDS on day 10 postpartum predicted a low mood over the first year postpartum. |

| Prenoveau36 | UK Age (years): GAD and MDD: 32.5 ± 5.3 GAD only: 31.8 ± 5.1 MDD only: 32.3 ± 5.6 No diagnosis: 32.6 ± 4.8 Female babies (%): GAD and MDD: 41.5 GAD only: 50 MDD only: 52.5 No diagnosis: 51.9 |

296 | Cohort study 21 months Four groups: - GAD and MDD - GAD only - MDD only - No diagnosis |

EPDS (cut-off value not given) |

GAD and MDD: 13.9% GAD only: 27.0% MDD only: 13.5% |

GAD MDD |

Women diagnosed with MDD at 3 months postpartum were significantly more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for MDD at least once during the follow-up period than those who were not diagnosed with MDD at 3 months (MDD only → MDD only (coefficient): 3 months → 6 months: 23.7; 6 months → 10 months: 28.6; 10 months → 14 months: 37.3; 14 months → 24 months: 135.0, p < 0.001). Women with MDD at 3 months were also significantly more likely to present with GAD at 6 months (3 months → 6 months: 10.9, p < 0.05), but not after. |

| Wang66 | Taiwan Age (years): Depressed: 28.34 ± 5.52 Nondepressed: 29.45 ± 4.13 Female babies: 55.0% |

60 | Cohort study 1 year Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

BDI-II | 48.3% | Psychosocial health | At 1 year after childbirth, women in the depressed group still suffered mild depression and reported greater perceived stress and lower perceived social support and self-esteem than women in the nondepressed group. Women at 6 weeks after childbirth suffered mainly from moderate-to-severe depression (23.76 ± 6.25 on the BDI), and symptoms improved to mild-to-moderate depression at 1 year (14.66 ± 7.22 on the BDI). |

| Vliegen37 | Belgium Mean age (years): T1: 29.39 ± 4.40 T2: 32.95 ± 4.51 Gender of newborns: not given |

41 | Cohort study 3.5 years Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

BDI-II (Depressed = BDI ⩾ 13) |

39% | Maternal depression; treatment after hospitalization; life events; relationship | Mothers who were depressed at follow-up had not only

significantly elevated scores for severity of depression

but also significantly elevated levels of state and

trait anxiety, state and trait anger, and negative

affect compared to nondepressed mothers. Depressed

mothers also had significantly higher levels of anger,

lower scores on anger control, and lower levels of

positive affect. Regarding emotional availability, they

showed a significantly lower level of mutual attunement,

but no differences were found on the other indices of

emotional availability. The number of depressive

episodes between Time 1 and Time 2 did not differ

between mothers with and mothers without current

depression at follow-up. However, currently depressed

mothers had significantly longer depressive episodes

(M = 90 weeks, SD = 80) compared to the mothers without

current depression (M = 42 weeks, SD = 45, p < 0.05).

Regarding treatment after hospitalization, the proportion of mothers who were hospitalized during the follow-up period was approximately 20% and did not differ between samples. |

GAD: generalized anxiety disorder; MDD: major depressive disorder; PPD: postpartum depression; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.); PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire depression module; QIDS-SR: Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (Self-Report); BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; GLM: general linear models; SD: standard deviation.

Overall psychological health

Several studies showed that depressed mothers presented lower mood scores in the long term (1 year after childbirth) than mothers without depression. One study highlighted that compared to the general population of women, depressed mothers scored significantly lower on the SF-36 mental component summary score (based on vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health).88 This study also showed that depressed mood was a significant predictor of mental health status in the future (explaining 18% of its variance).88 Another study showed that women with PPD had lower self-esteem than mothers without depression.66 Depressed mothers also reported being less happy, more dysphoric, and sadder than mothers without depression.44 In addition, women with high depression scores had significantly higher levels of anger, lower scores for anger control, and lower levels of positive affect than mothers with low depression scores.37 Finally, mothers with PPD were generally less responsive to negative stimuli, with lower ratings for intensity and reactions to negative pictorial stimuli, than mothers without PPD.42

Anxiety

One study showed that depressed mothers had significantly elevated levels of state and trait anxiety at 1 year and 3.5 years after childbirth compared with nondepressed mothers.37 Another study highlighted that depressed mothers at 3 months postpartum were more likely to exhibit an anxiety disorder than nondepressed mothers at 6 months postpartum, but not after this time point.36

Depression

Compared to nondepressed women, women who were diagnosed with depression in the first weeks after childbirth continued to suffer from depression at 1 year after childbirth.36,37,66 However, one study underlined that although mothers continued to suffer from depression, the symptoms appeared to improve, progressing from moderate-to-severe depression at 6 weeks to mild-to-moderate depression at 1 year.66 Therefore, there appeared to be a slight improvement in the severity of depression over time with or without treatment.66 Another study used a life history calendar method and found that compared to currently nondepressed mothers, mothers who were depressed at follow-up (3.5 years) did not have more depressive episodes; however, they had longer depressive episodes, received more psychotherapy after hospitalization, and experienced more negative life events during the follow-up period.37

Quality of life

Eight studies27,37,39,48,66,85,86,88 examined the overall quality of life of depressed mothers compared with nondepressed mothers (Table 3). Three studies48,86,88 demonstrated a significantly negative association between maternal depressive symptoms and quality of life. Women with PPD had lower scores on all dimensions of quality of life (e.g. SF-36 or a generic Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) questionnaire) than women without PPD. However, one of the three studies showed that after controlling for mental health-related quality of life earlier in the postpartum period, there was no difference in the subsequent mental health-related quality of life according to the presence of significant depressive symptoms later in the postpartum period.48

Table 3.

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of the maternal quality of life.

| First author’s name | Sociodemographic data: 1. Country 2. Maternal mean age 3. Gender of newborns |

Sample size | Design: 1. Study design 2. Time of follow-up 3. Number of groups 4. Description of groups |

Tool used to assess PPD | Prevalence of PPD | Outcomes | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curtis27 | USA Mean age: 25.0 ± 6.0 years Female babies: 48% |

2974 | Cohort study 3 years Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

CIDI-SF | 12.6% | Homelessness or risk of homeless (lack of fixed, regular, and adequate night-time residence or residence in a temporary accommodation or space not intended for residence) | Mothers who experienced depression were significantly more likely than those who did not to become homeless (6% vs 2%) and to be at risk of homelessness (conditional on not having become homeless; 14% vs 9%). Depression during the postpartum year was associated with more than twice the odds of homelessness (OR = 2.29, 95% CI = 1.08, 4.85) and almost 1.5 times the odds of being at risk of homelessness (OR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.12, 1.75) at 3 years. |

| Da Costa88 | Canada Mean age: 33.2 ± 4.6 years Gender of newborns: not given |

78 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 10) |

63% (EPDS ⩾ 12) | Physical health status; mental health status; health-related quality of life | Women who were depressed during postpartum scored significantly lower on all eight SF-36 dimensions and on both summary component scores compared to age-appropriate normative means. |

| Darcy48 | USA Mean age: 30.3 years Gender of newborns: not given |

217 | Cohort study 1 year Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

CES-D | 32.7% | Maternal health-related quality of life (mental component and physical component) | Mothers with significant depressive symptoms had significantly worse physical (p = 0.02) and mental (< 0.0001) health-related quality of life. After controlling for mental health-related quality of life earlier in the postpartum period, there was no difference in subsequent mental health-related quality of life based on the presence of significant depressive symptoms later in the postpartum period. |

| De Tychey86 | France Age: not given Female babies: 48.1% |

181 | Cross-sectional study Three groups: - No depression - Mild depression - Severe depression |

EPDS (Mild, ⩾8 and <12; Severe, ⩾12) |

Mild depression: 22.1% Severe depression: 9.4% |

Postnatal quality of life | Postnatal depression strongly and negatively influenced all dimensions of life quality explored through the SF-36, e.g., physical functioning (PF), physical role (RP), bodily pain (BP), mental health (MH), emotional role (RE), social functioning (SF), vitality (VT), general health (GH), standardized physical component (PCS), and standardized mental component (MCS). |

| Posmontier85 | USA Mean age (years): No PPD: 31.0 ± 4.5 PPD: 30.0 ± 5.5 Female babies (%): No PPD: 78.3 PPD: 30.4 |

46 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

MINI | Not applicable (number of PPD and no PPD women were

fixed at the beginning of the study)

Nondepressed: n = 23 Depressed: n = 23 |

Functional status (physical infant care, personal care, household care, social activities, and occupational activities) | Specifically, lower levels of household, social, and personal functioning were correlated with PPD. In multiple regression analyses, PPD predicted lower overall functional status (p < 0.001), household function (p < 0.05), social function (p < 0.001), and personal function (p < 0.001). |

| Wang66 | Taiwan Age (years): Depressed: 28.34 ± 5.52 Nondepressed: 29.45 ± 4.13 Female babies: 55.0% |

60 | Cohort study 1 year Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

BDI-II | 48.3% | Psychosocial health | Significant differences were found between the depressed and the nondepressed groups for depression, perceived stress, social support, and self-esteem. At 1 year after childbirth, women in the depressed group still suffered from mild depression and showed greater perceived stress and lower perceived social support and self-esteem than women in the nondepressed group. |

| Taylor39 | Australia Mean age: 30.3 ± 5.0 years Gender of newborns: not given |

615 | Cohort study 24 weeks Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 13) |

T1: 9.2% T2: 9.4% T3: 8.4% T4: 7.0% |

Fatigue | One week after birth, state anxiety (0.47) and more depressive symptoms (0.28) were significantly (< 0.05 to < 0.01) correlated with fatigue. At 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months, depression was no longer associated with fatigue, but maternal state anxiety was a major predictor of fatigue (ranging from β = 0.38 to 0.51). |

| Vliegen37 | Belgium Mean age (years): T1: 29.39 ± 4.40 T2: 32.95 ± 4.51 Gender of newborns: not given |

41 | Cohort study 3.5 years Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

BDI-II (Depressed = BDI ⩾ 13) |

39% | Maternal depression; treatment after hospitalization; life events; relationship | Currently depressed mothers reported significantly more negative life events, indicating greater distress and discontinuity. More specifically, currently depressed mothers reported more financial problems (69% vs 31%, p < 0.05) and more illness among close relatives (100% vs 46%, p < 0.05). |

PPD: postpartum depression; CIDI-SF: Composite International Diagnostic Interview—Short Form; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Studies also showed that PPD was associated with greater perceived stress,66 more negative life events (indicating greater distress and discontinuity), more financial problems, and more illness among close relatives.37 Depressive symptoms were also associated with fatigue during the first week but not at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months after childbirth.39

Regarding the life environment, one study showed that PPD predicted lower levels of household functioning (household care).85 Another study demonstrated that mothers who experienced depression were twice as likely to become homeless and approximately 1.5 times more likely to be at risk for homelessness than nondepressed mothers.27

Relationships

Seven studies evaluated social and couple relationships in relation to maternal depressive symptoms (Table 4); four studies were related to social relationships,37,66,73,85 and four studies were related to relationships with partners and sexuality.37,38,44,74

Table 4.

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of the maternal social and couple relationship.

| First author’s name | Sociodemographic data: 1. Country 2. Maternal mean age 3. Gender of newborns |

Sample size | Design: 1. Study design 2. Time of follow-up 3. Number of groups 4. Description of groups |

Tool used to assess PPD | Prevalence of PPD | Outcomes | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dagher73 | USA Mean age: 29.3 ± 5.6 years Gender of newborns: not given |

882 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

PDSS-SF | 62.0% | Return to work and intention to return to work | Tending to the baby and being depressed suppressed the return to paid work. Nondepressed mothers with unintended pregnancies returned to work the soonest. Compared with mothers who were not depressed and had an unintended pregnancy, the RR of returning to paid work (0.70) was significantly lower for mothers who were depressed and had an intended pregnancy. Mothers who were not depressed and had an intended pregnancy also had a significantly lower RR (0.60) of returning to paid work than those who were not depressed and had an unintended pregnancy. |

| Faisal-Cury38 | Brazil Mean age: 25 years Gender of newborns: not given |

644 | Cohort study Approximately 2 years Four groups: - None - Pregnancy only - Postpartum only - Pregnancy and postpartum |

SRQ-20 | Pregnancy only: 15.2% Postpartum only: 12.1% Pregnancy and postpartum: 15.7% |

Sexual life | The mean time to the resumption of sexual activity during the postpartum period was 2.1 (range = 1–12) months. In the multivariable analysis after adjustment for wealth score, episiotomy, forceps delivery, previous pregnancies and marriage status, depression during pregnancy and postpartum (RR = 3.17, 95% CI = 2.18, 4.59), depression during only the postpartum period (RR = 3.45, 95% CI = 2.39, 4.98), a previous miscarriage, and patient age were significantly associated with sexual decline. |

| Khajehei74 | Australia Mean age: 29.8 years Female babies (%): FSD: 49.3 No FSD: 51.7 |

325 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - FSD - No FSD |

PHQ-8 | FSD: 14.8% No FSD: 9.5% |

Sexual dysfunction during the first year after childbirth | Depression (OR = 2.876; 95% CI = 1.318, 6.276; p = 0.008) was a significant risk factor for sexual dysfunction during the first year after childbirth. |

| Lilja44 | Sweden Mean age: 27.8 years Gender of newborns: not given |

419 | Cohort study 1 year Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 10) |

22.2% | Women’s mood over the first year postpartum; women’s relationship with their infant; women’s relationship with their partner | Mothers who scored high on the EPDS at 10 days postpartum tended to rate their relationship with their partner lower at all observations during the first year than mothers who had low EPDS scores on day 10. The same applied to the relationship between EPDS at day 3 and the relationship scales. Thus, mothers with a high score on the EPDS early in the postpartum period rated their relationship with their partner as more distant, cold and difficult, and felt less confident than mothers with low EPDS scores over the first year. |

| Posmontier85 | USA Mean age (years): No PPD: 31.0 ± 4.5 PPD: 30.0 ± 5.5 Female babies (%): No PPD: 78.3 PPD: 30.4 |

46 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

MINI | Not applicable (number of PPD and no PPD women were

fixed at the beginning of the study)

Nondepressed: n = 23 Depressed: n = 23 |

Functional status (physical infant care, personal care, household care, social activities, and occupational activities) | Specifically, lower household, social, and personal functioning were correlated with PPD. In multiple regression analyses, PPD predicted lower overall functional status (p < 0.001), household function (p < 0.05), social function (p < 0.001), and personal function (p < 0.001). |

| Wang66 | Taiwan Age (years): Depressed: 28.34 ± 5.52 Nondepressed: 29.45 ± 4.13 Female babies: 55.0% |

60 | Cohort study 1 year Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

BDI-II | 48.3% | Psychosocial health | Significant differences were found between the depressed and the nondepressed groups in depression, perceived stress, social support, and self-esteem. At 1 year after childbirth, women in the depressed group still suffered mild depression and reported greater perceived stress and lower perceived social support and self-esteem than women in the nondepressed group. |

| Vliegen37 | Belgium Mean age (years): T1: 29.39 ± 4.40 T2: 32.95 ± 4.51 Gender of newborns: not given |

41 | Cohort study 3.5 years Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

BDI-II (Depressed = BDI ⩾ 13) |

39% | Maternal depression; treatment after hospitalization; life events; relationship | Currently depressed mothers reported having to move more often (92% vs 73%, ns) and having more relationship difficulties, including romantic break-ups (46% vs 35%, ns). |

FSD: female sexual dysfunction; PPD: postpartum depression; PDSS-SF: Postpartum Depression Screening Scale—Short Form; SRQ-20: Self-Reporting Questionnaire-20; PHQ-8: Patient Health Questionnaire depression module; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; RR: risk ratio; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Social relationships

PPD was associated with more relationship difficulties37 and therefore with lower social function.85 Depressed mothers also presented lower (perceived) social support scores than nondepressed mothers.66 Regarding the probability of returning to paid work, one study showed that there was no difference between depressed and nondepressed mothers.73 The authors of this study specified that most mothers experienced depressive symptoms during the first year after childbirth; thus, depression was not an independent predictor of how quickly mothers would return to work.

Partner relationships and sexuality

Depressed mothers rated their relationship with their partner as more distant, cold and difficult, and felt less confident than nondepressed mothers over the first year after childbirth.44 Depressed mothers also reported having more relationship difficulties, including romantic break-ups, than nondepressed mothers; however, this difference was not significant.37 Regarding sexual life during the first year after childbirth, mothers who had resumed sexual activity had lower depression scores than mothers who did not resume sexual activity during the postpartum period.38 In addition, depression appeared to cause nearly three times more sexual dysfunction during the first year after childbirth.74

Risky behaviors

Addictive behavior

Three studies55,84,87 evaluated the influence of PPD on smoking behavior (Table 5). One study showed that smoking and depression often co-occurred among mothers during the postpartum period.87 The prevalence of PPD was higher among smokers than nonsmokers; conversely, smoking was also more common among mothers with a major depressive episode. The two other studies demonstrated that women who quit smoking during pregnancy might be more likely to relapse if they experience negative emotions or depressive symptoms.55,84 In addition, one study evaluated the influence of PPD on postpartum “risky” drinking at 3 months among women who were frequent drinkers before pregnancy.68 This study emphasized that there was no significant association between maternal PPD and risky drinking.

Table 5.

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of the maternal risky behavior.

| First author’s name | Sociodemographic data: 1. Country 2. Maternal mean age 3. Gender of newborns |

Sample size | Design: 1. Study design 2. Time of follow-up 3. Number of groups 4. Description of groups |

Tool used to assess PPD | Prevalence of PPD | Outcomes | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addictive behavior | |||||||

| Allen84 | USA Age (years): <20: 15.3% 20–24: 37.8% 25–29: 27.0% >29: 19.9% Gender of newborns: not given |

2566 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

Specific to the survey | 18.8% | Relapse of smoking during postpartum | Compared to women who did not experience postpartum depressive symptoms, women who did were 1.86 (95% CI = 1.31, 2.65) times as likely to relapse during the postpartum period. After adjusting for demographic characteristics, intensity of smoking, and time since delivery, the association decreased slightly (adjusted OR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.21, 2.59). |

| Jagodzinski68 | USA Age (years): 18–25: 42.3% 26–35: 44.6% ⩾36: 12.3% Missing: 0.8% Gender of newborns: not given |

381 | Cross-sectional study (recruitment phase of a

randomized clinical trial) Two groups: - Low risk of drinking - At risk of drinking |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS > 12) |

16.0% | Postpartum risky drinking | At 3 months postpartum, the risk of drinking was not significantly different between women who had an EPDS score >12 and women who had an EPDS score ⩽12 (adjusted OR (95% CI) = 1.1 (0.5, 2.5)). |

| Park55 | USA Mean age: 28.8 ± 6.1 years Gender of newborns: not given |

65 | Cohort study 22 weeks Two groups: - Smokers - Nonsmokers |

BDI | Not given Mean BDI: 5.8 ± 4.7 |

Postpartum relapse of smoking | In a regression model, the slope of BDI scores from baseline to the 12-week follow-up differed between nonsmokers and smokers (−0.12 vs +0.11 units/week, p = 0.03). The mean slope of BDI scores between baseline and 24 weeks postpartum decreased (−0.07 units/week) among nonsmokers and rose (+0.05 units/week) among those who smoked (p = 0.01). |

| Whitaker87 | USA Age (years): <20: 17.9% 20–29: 59.2% ⩾30: 22.9% Gender of newborns: not given |

4353 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

CIDI-SF | 13.6% | Smoking behavior | After adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, the prevalence (95% CI) of a major depressive episode was higher among smokers than nonsmokers: 17.7% (15.7, 19.8) vs 12.1% (10.9, 13.3). Smoking was also more common among mothers who had had a major depressive episode than among those who had not: 34.0% (30.6, 37.4%) vs 25.5% (24.1, 26.8%). |

| Suicidal ideation | |||||||

| Barr93 | Australia Age: between 20 and 34 years Gender of newborns: not given |

15 | Cross-sectional study (qualitative study)

One group: - PPD |

Not given | 100% | Thoughts of infanticide that did not lead to the act | Women who experienced nonpsychotic depression preferred not to disclose their thoughts of infanticide to health professionals, including trusted general practitioners or psychiatrists. These women were more likely to mention their suicidal thoughts than their infanticidal thoughts to obtain health care. |

| Do33 | USA Mean age: not given Gender of newborns: not given |

178,714 | Cohort study 6 years Four groups: Active component service women: - PPD - No PPD Dependent spouses: - PPD - No PPD |

ICD-9-CM | Active component service women: 9.9%

Dependent spouses: 8.2% |

Suicide attempt | Service women with PPD had higher odds of suicidality compared to service women without PPD (OR = 42.2, 95% CI = 28.8, 61.9). Dependent spouses with PPD also had higher odds of suicidality compared to dependent spouses without PPD (OR = 14.5, 95% CI = 10.8, 19.4). |

| Kim28 | USA Mean age (years): Suicidal ideation: 32.2 ± 6.3 No suicidal ideation: 32.2 ± 5.6 Gender of newborn: not given |

22,118 | Cohort study 23 weeks Two groups: - Suicidal ideation - No suicidal Ideation |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 12) |

Not given | Suicidal ideation | Among 22,118 EPDS questionnaires studied, suicidal ideation was reported on 842 (3.8%, 95% CI = 3.5, 4.1) and was positively associated with pre-existing psychiatric diagnosis during the postpartum (12.0% compared with 5.8%, p = 0.001). Among perinatal women screened for depression, 3.8% reported suicidal ideation; 1.1% of this subgroup was at high risk of suicide. Multivariable postpartum models did not retain the PPD. |

| Paris81 | USA Mean age: 32.5 ± 5.6 years Gender of newborns: not given |

32 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - Low suicidality - High suicidality |

PDSS | 100% | Suicidality (suicidal ideation) | Overall, women in this clinical sample had wide ranging levels of suicidal thinking. When divided into low and high suicidality groups, the mothers with high suicidality experienced greater mood disturbances and cognitive distortions, and more severe postpartum symptomatology. |

| Pope30 | UK Mean age: 29.0 ± 5.5 years Gender of newborns: not given |

147 | Cohort study 1 year Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (use of item 10 on the EPDS referring to “thoughts of self-harm”) HDRS |

Not applicable (only women with MDD (64%) or bipolar disorder (36%) were included in the study) |

Thoughts of self-harm; suicidal ideation | Women with suicidal ideation were more likely to have higher levels of depression than women without suicidal ideation (EPDS: 21.5 vs 9.9, p = 0.03; HDRS: 18.6 vs 7.73, p = 0.04). Women with thoughts of self-harm were more likely to have higher levels of depression than women without thoughts of self-harm (EPDS: 16.4 vs 9.5, p = 0.04; HDRS: 13.0 vs 7.5, p = 0.05). Women with hypomanic symptoms during the postpartum period were also more likely to have thoughts of self-harm or suicidal ideation. |

| Posmontier85 | USA Mean age (years): No PPD: 31.0 ± 4.5 PPD: 30.0 ± 5.5 Female babies (%): No PPD: 78.3 PPD: 30.4 |

46 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

MINI | Not applicable (number of PPD and no PPD women were

fixed at the beginning of the study)

Nondepressed: n = 23 Depressed: n = 23 |

Functional status (physical infant care, personal care, household care, social activities, and occupational activities) | Depressed mothers presented more suicidal thoughts (6.52, SD = 3.64) than nondepressed mothers (4.25, SD = 0.25, p < 0.01). |

| Tavares76 | Brazil Age (years): 13–19: 20.0% 20–34: 69.9% 35–45: 10.1% Gender of newborns: not given |

919 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

MINI | 8.5% | Suicide risk | Lower education levels and psychiatric disorders were associated with suicide risk. The mothers who experienced depressive episodes had a 12.6 (95% CI = 7.0, 22.6) times greater risk of presenting with suicidal signs. Women who had hypomanic episodes were 7.01 (95% CI = 3.54, 13.9) times more likely to show signs of suicide risk compared to those without hypomanic episodes. Bipolar disorder was the psychiatric disorder with the highest impact on suicide risk. |

PPD: postpartum depression; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CIDI-SF: Composite International Diagnostic Interview—Short Form; ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; PDSS: Postpartum Depression Screening Scale; HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MDD: maternal major depressive disorder; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation.

Suicidal ideation

Five studies showed that higher levels of depressive symptoms were associated with an increased prevalence of suicidal ideation30,33,76,81,85 (Table 5). Mothers with high suicidality risks experienced greater mood disturbances and more severe postpartum symptomatology than mothers with low suicidality risks.81 One of the five studies also demonstrated that women who reported higher levels of depression were also significantly more likely to report thoughts of self-harm than women with low levels of depression.30 The sixth study28 showed a significant association between PPD and suicidal ideation in an unadjusted analysis, but not in adjusted analysis. An additional study demonstrated that mothers who experienced PPD could imagine acts of infanticide.93 The authors of this study explained that many mothers preferred to describe their suicidal thoughts rather than their infanticidal thoughts when seeking health care.

Infant consequences of PPD

Anthropometry

The characteristics and main results of the studies included in the evaluation of anthropometric parameters are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of infant anthropometric outcomes.

| First author’s name | Sociodemographic data: 1. Country 2. Maternal mean age 3. Gender of newborns |

Sample size | Design: 1. Study design 2. Time of follow-up 3. Number of groups 4. Description of groups |

Tool used to assess PPD | Prevalence of PPD | Outcomes | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adewuya119 | Nigeria Mean age: not given Gender of newborns: not given |

242 | Cohort study 8 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

SCID-NP | 49.6% | Infants’ physical growth (weight and length); cases of diarrhea and other childhood illnesses in infants; breastfeeding | The differences in weight and length gradually increased starting at the 6th week, peaked at the 6th month, and declined afterwards. |

| Avan110 | South Africa Age (years): <35: 91.5% ⩾35: 8.5% Female babies: 49.9% |

1035 | Cohort study 18 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

Pitt Inventory | 24.0% | Child growth; child behavioral problems (Richman Child Behavior Scale) | Two-year-old children with depressed mothers had an increased risk of stunted growth compared to those with nondepressed mothers. |

| Bakare140 | Nigeria Mean age: 28.2 ± 5.1 years Female babies: 47.8% |

408 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 9) |

24.8% | Weight; length; head circumference | Maternal PPD was significantly associated with infants’ weight and length, but not their head circumference. |

| Ertel109 | USA Mean age: 33.0 ± 4.5 years Female babies: 52.3% |

872 | Cohort study 3 years Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 13) |

7.3% | Height and linear growth | Exposure to PPD was associated with a greater height-for-age z-score and longer leg length starting at 6 months and continuing to age 3 years. |

| Ertel112 | USA Mean age: 33.0 ± 4.46 years Female babies: 52.2% |

838 | Cohort study 3.5 years Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 13) |

7.04% | BMI z-score; WHZ; sum of SS and TR skinfold thickness for overall adiposity; sum of SS and TR skinfold thickness ratio for central adiposity | In multivariable models, PPD was only associated with a higher sum of SS and TR skinfold thickness (SS + TR) for overall adiposity (adjusted OR (95% CI) = 1.14 (0.11, 2.18)), but this association was not significant. The results for other outcomes showed very small effect estimates. For example, regarding the association between PPD and child WHZ, the estimated associations were similar for each age from 6 months to 3 years: 0.08 (95% CI = −0.14, 0.30) when controlling for child sex and age at assessment, maternal age, race/ethnicity, household income, pre-pregnancy BMI, pregnancy weight gain, gestational diabetes or impaired glucose intolerance, gestational age at delivery, and birthweight-for-gestational age. |

| Ertel100 | The Netherlands Mean age: 30.3 ± 5.24 years Female babies: 49.5% |

6782 | Cohort study 41 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

BSI | 8.25% at 2 months 8.85% at 6 months |

Child overweight | There was no association between perinatal depression and child BMI at any time point. |

| Gress-Smith104 | USA Mean age: 26.5 ± 5.59 years Gender of newborns: not given NB: very low-income population |

132 | Cohort study 9 months Three groups: - No PPD - Significant levels of depressive symptoms (CES-D ⩾ 16) - Severe depressive symptoms (CES-D ⩾ 24) |

CES-D | 5 months: 33% of depressive symptoms; 12% of severe

depressive symptoms 9 months: 38% of depressive symptoms; 18% of severe depressive symptoms |

Infant weight; infant health; infant sleep | Higher depressive symptoms at 5 months postpartum were associated with less infant weight gain from 5 to 9 months. |

| Grote113 | Belgium, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain Age (years): <28: 27.3% 28 ⩽ 33: 39.1% 33–44: 33.6% Female babies: 51.7% |

929 | Cohort study 2 years Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 13) |

11.0% | Weight; length; TR skinfold thickness; SS skinfold thickness; weight for length | Infant weight, length, and BMI at 24 months of age did not differ between high and normal EPDS groups. TR skinfold thickness and SS skinfold thickness did not differ between the two groups. |

| Kalita131 | India Age (years): Depression: 28.2 ± 0.93 Anxiety: 29.8 ± 1.68 Not diagnosed: 28.3 ± 1.28 Female babies: 52.0% |

100 | Cohort study 6 months Three groups: - PPD - Anxiety - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 13) |

18.0% | Weight; communication; symbolic behaviors | Infants with mothers suffering from PPD had significantly lower weights at 6 months of age compared to infants born to mothers who did not suffer from PPD. |

| Nasreen97 | Bangladesh Mean age: 24.2 ± 6.7 years Female babies: 50.7% |

652 | Cohort study 1 year Four groups: - No depression - PPD during pregnancy only - PPD during pregnancy and postpartum - PPD during postpartum only |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 10) |

14.1% at 2–3 months 31.7% at 6–8 months |

Infant’s growth (underweight at 6–8 months, stunting at 6–8 months); infant’s motor development | Maternal depressive symptoms at 2–3 months postpartum were associated with infant underweight at age 6–8 months. No significant association was found between maternal postpartum depressive symptoms at 2–3 months and infant stunting at 6–8 months. |

| Ndokera142 | Zambia Age (years): ⩽18: 9% 19–24: 35.6% 25–30: 33.1% ⩾31: 22.3% Female babies: 45.3% |

278 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

SRQ-20 | 9.7% | Weight; length; diarrheal episodes; incomplete vaccination | Infants of depressed mothers were lighter and shorter than infants of nondepressed mothers after adjustment for age, gender, and maternal weight. |

| Tomlinson126 | South Africa Age (years): <20: 15.3% 20–24: 26.5% 25–29: 32.7% 30–39: 25.5% Female babies: 44.9% |

147 | Cohort study 18 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

SCID | 34.7% at 2 months 12% at 18 months |

Infant weight; infant length | There were no significant relationships at 2 and 18 months between maternal depression and mean standardized infant weight or length. |

| Wright125 | UK Mean age: not given Gender of newborns: not given |

915 (923 infants) |

Cohort study 13 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS > 12) |

12.0% | Overall infant weight gain; weight faltering | Infants of depressed mothers showed slower overall weight gain and an increased rate of weight faltering from birth to 4 months. However, over the 12-month period, there was no difference in weight gain between the infants of depressed and nondepressed mothers. |

PPD: postpartum depression; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SCID-NP: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Non-Patient edition; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory; SRQ-20: Self-Reporting Questionnaire-20; BMI: body mass index; WHZ: weight-for-height z-score; SS: subscapular; TR: triceps; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Weight

A total of 11 studies reported weight as an outcome. Among them, five studies97,104,131,140,142 demonstrated a significant effect of maternal PPD on the child’s weight; infants of depressed mothers gained less weight than infants of nondepressed mothers. Four studies were conducted in low-resource countries (India,131 Nigeria,140 Zambia,142 and Bangladesh97), and one study was conducted in the United States with a very low-income population.104 Two other studies (one in the United Kingdom125 and one in Nigeria119) showed that while there were differences in infant weight in the first months of life, they did not persist. Finally, four studies demonstrated that maternal PPD had no effect100,113,126 or a very small effect112 on the child’s weight. Two studies were conducted in high-income countries (a multicountry study that included Belgium, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Spain113 and one study conducted in the Netherlands100). The third study126 was conducted in South Africa; however, the authors stated that they were unable to test their hypothesis due to a lack of statistical power.

Length

Eight studies identified in this systematic review reported infant length as an outcome. Three of the studies110,140,142 showed a significant effect of maternal PPD on stunting. The three studies were conducted in low-resource countries (Nigeria,140 Zambia,142 and South Africa110). One other study119 showed differences in length in the first months of life; however, it was determined that these differences did not persist over time (Nigeria). Three other studies97,113,126 demonstrated that maternal PPD had no effect on stunting. One multicountry study113 evaluated high-income countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Spain), and two studies were conducted in low-income countries, including Bangladesh97 and South Africa.126 The authors of the South African study stated that they were unable to test their hypothesis due to a lack of statistical power. Another study109 conducted in a high-income country (the United States) showed the opposite effect: exposure to PPD was associated with a greater height-for-age z-score and a longer leg length.

Anthropometric indices

Four studies evaluated anthropometric indices, and two of them showed no effect of maternal PPD. One study140 found that maternal PPD was not associated with head circumference (Nigeria). Two studies demonstrated that the triceps and subscapular skinfold thicknesses did not differ between infants of depressed and nondepressed mothers (one study was conducted in Belgium, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Spain;113 the other was from the United States112). In contrast, one study from the United States109 showed that PPD was associated with higher subscapular and triceps skinfold thickness scores, which indicated overall adiposity.

Infant health

Of the 10 cohort studies, 9 indicated a significant association between maternal PPD and health concerns in infants (Table 7). Maternal depressive symptoms at 5 months seemed to predict more overall physical health concerns for infants at 9 months104 and a greater proportion of childhood illnesses.119 Three studies showed that infants of depressed mothers had significantly more diarrheal episodes per year than those of nondepressed mothers,119,122,138 and one study reported that infants of depressed mothers had more days of illness with diarrhea.138 Harriet et al. specified that these associations with diarrheal episodes were accurate only within the first 3 months. One study also associated maternal depressive symptoms with infant colic.124 Two studies reported greater overall pain in the infants of depressed mothers48 and a stronger infant pain response during routine vaccinations.123 One study demonstrated that maternal PPD at 4 months predicted worse health-related quality of life for the infant in the following months.48 One study indicated a robust and predictive association between maternal PPD and febrile disease in children.135 Another study136 showed that probable postnatal depression was associated with an approximately three-fold increased risk of mortality in infants up to 6 months of age, with an approximately two-fold increased risk of mortality up to 12 months of age. This study also showed that probable postnatal depression was associated with an increased risk of infant morbidity. Only one cross-sectional study reported a nonsignificant association between a high risk of maternal depression and serious illness or diarrheal episodes after adjusting for infant age and other possible confounders.142 Nevertheless, the occurrence of these two outcomes was proportionally higher among infants of depressed mothers.

Table 7.

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of infant health.

| First author’s name | Sociodemographic data: 1. Country 2. Maternal mean age 3. Gender of newborns |

Sample size | Design: 1. Study design 2. Time of follow-up 3. Number of groups 4. Description of groups |

Tool used to assess PPD | Prevalence of PPD | Outcomes | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adewuya119 | Nigeria Mean age: not given Gender of newborns: not given |

242 | Cohort study 8 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

SCID-NP | 49.6% | Infant physical growth (weight and length); cases of diarrhea and other childhood illnesses in the infants; breastfeeding | By the 9th month, the average number of cases of diarrhea and other childhood illnesses in the infants of depressed mothers was 5.23 (SD = 2.37), while the average number of those illnesses in infants of nondepressed mothers was 3.70 (SD = 4.14). The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.001). |

| Akman124 | Turkey Age (years): Infant colic+: 31.1 ± 6.0 Infant colic−: 29.6 ± 4.8 Female babies: 50.0% |

78 | Cohort study 6 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 13) |

12.9% | Infant colic | Infant colic was present in 17 infants (21.7%), and 12.9% of the mothers had an EPDS score >13. The mean EPDS score of mothers whose infants had infant colic (10.2 ± 6.0) was significantly higher than that of mothers of infants without colic (6.3 ± 4.0). |

| Darcy48 | USA Mean age: 30.3 years Gender of newborns: not given |

217 | Cohort study 1 year Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

CES-D | 32.7% | Infant health-related quality of life (pain/discomfort and health-related concerns) | Mothers with significant depressive symptoms reported greater pain in their infant and had more health-related concerns about their child. Maternal depressive symptoms at 4 months predicted poorer health-related quality of life for the infant at 8, 12, and 16 months. |

| Gress-Smith104 | USA Mean age: 26.5 ± 5.59 years Gender of newborns: not given NB: very low-income population |

132 | Cohort study 9 months Three groups: - No PPD - Significant levels of depressive symptoms (CES-D ⩾ 16) - Severe depressive symptoms (CES-D ⩾ 24) |

CES-D | 5 months: 33% of depressive symptoms; 12% of severe

depressive symptoms. 9 months: 38% of depressive symptoms; 18% of severe depressive symptoms. |

Infant weight; infant health; infant sleep | Maternal depressive symptoms at 5 months predicted more physical health concerns in the infants at 9 months (B = 0.05, SE = 0.03, p < 0.05). |

| Guo135 | Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana Mean age: 29.1 ± 5.4 years Female babies: 48.9% |

654 | Cohort study 2 years Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

PHQ-9 | 3 months: 11.8% in Côte d’Ivoire; 8.9% in Ghana.

12 months: 16.1% in Côte d’Ivoire; 7.2% in Ghana. |

Febrile illness | The hazard of febrile disease in children of depressed mothers was 57% higher than the hazard in children of nondepressed mothers. Country and SES were identified as confounders. After adjusting for both, the hazard of developing a febrile illness was 32% higher in children whose mothers had depression than in children whose mothers did not have depression. The authors constructed a cumulative depression exposure by categorizing the mothers as “never depressed” or “depressed one time” and “depressed 2 or 3 times.” The crude and adjusted hazard ratios for children of recurrently depressed mothers compared to those for children of mothers with fewer episodes of depression were 2.20 (95% CI = 1.51, 3.19) and 1.90 (95% CI = 1.32, 2.75), respectively. |

| Harriet138 | Ghana Mean age: 28.5 ± 0.3 years Gender of newborns: not given NB: HIV-infected mothers |

552 | Cohort study 12 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 13) |

10.0% | Diarrhea | In the first 3 months of life, infants of mothers who reported PND symptoms had almost twice the number of diarrheal episodes (p = 0.0005) and more than twice as many days ill with diarrhea (p = 0.0002) compared to infants whose mothers reported no PND symptoms. No significant association was observed after 3 months. |

| Moscardino123 | Italy Mean age: 33.3 ± 5.1 years Female babies: 50.0% |

28 | Cohort study 2.5 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (cut-off value not given) |

Not given (mean EPDS score = 7.5) | Infant response to vaccination | Higher levels of depressed maternal mood were predictive of a stronger infant pain response to routine vaccination. Infants exhibiting a stronger pain response during the inoculation procedure at 4.5 months were more likely to have mothers who reported higher levels of depressed mood at 2 months (p = 0.032) and at 4.5 months (p = 0.016). The mothers’ PND at 2 months was only marginally related to the infant pain response (p = 0.086). |

| Ndokera142 | Zambia Age (years): ⩽18: 9% 19–24: 35.6% 25–30: 33.1% ⩾31: 22.3% Female babies: 45.3% |

278 | Cross-sectional study Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

SRQ-20 | 9.7% | Weight; length; diarrheal episodes; incomplete vaccination | All outcomes were proportionally higher among the infants of “depressed” mothers, although none of these differences were statistically significant. Logistic regression analysis to adjust for infant age and other possible confounders showed no significant association between a high risk of maternal depression and serious illness or diarrheal episodes. |

| Rahman122 | Pakistan Mean age: 26.0 years Female babies: 49.8% |

265 | Cohort study 1 year Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry developed by the WHO | 49.1% | Diarrheal illness | Infants of depressed mothers had significantly more diarrheal episodes per year than those in the control group. The RR of having >5 diarrheal episodes per year in infants of depressed mothers was 2.3 (95% CI = 1.6, 3.1). The association remained significant after other risk factors were adjusted by a multivariate analysis (RR = 3.1; 95% CI = 1.8, 5.6; p < 0.01). |

| Weobong136 | Ghana Mean age: not given Gender of newborns: not given |

16,560 | Cohort study 6 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

PHQ-9 | 3.5% | Infant mortality; infant morbidity | All-cause infant mortality from the time of the PND assessment up to 6 months of age (adjusted RR = 2.86, 95% CI = 1.58, 5.19) was almost three times higher for infants of depressed mothers compared to those whose mothers were not depressed, and there was almost a two-fold increase in all-cause infant mortality up to 12 months of age (adjusted RR = 1.88, 95% CI = 1.09, 3.24). Among the potential confounders included in the model, only time of delivery (preterm) was also associated with an almost five-fold increased risk of infant deaths up to 6 months of age (adjusted RR = 4.61, 95% CI = 2.02, 10.51). An increased risk of infant morbidity indicators was associated with probable PND. |

PPD: postpartum depression; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SCID-NP: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Non-Patient edition; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire depression module; SRQ-20: Self-Reporting Questionnaire-20; WHO: World Health Organization; SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence interval; SES: socioeconomic status; PND: postnatal depression; RR: risk ratio.

Infant sleep

Three studies evaluated the association between maternal depressive symptoms and infant sleep patterns (Table 8). Two studies showed that higher depressive symptoms were associated with an increased incidence of infant night-time awakenings and predicted more problematic infant sleep patterns.104,108 One of the two studies demonstrated that children whose mothers had severe and/or chronic depressive symptoms had a higher risk of sleep disorders than those with mothers who had mild depressive symptoms.108 The third study reported that significantly fewer children of mothers with depressive symptoms were placed in the recommended back-to-sleep position compared with children of women who had not experienced depression.130

Table 8.

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of infant sleep.

| First author’s name | Sociodemographic data: 1. Country 2. Maternal mean age 3. Gender of newborns |

Sample size | Design: 1. Study design 2. Time of follow-up 3. Number of groups 4. Description of groups |

Tool used to assess PPD | Prevalence of PPD | Outcomes | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gress-Smith104 | USA Mean age: 26.5 ± 5.59 years Gender of newborns: not given NB: very low-income population |

132 | Cohort study 9 months Three groups: - No PPD - Significant levels of depressive symptoms (CES-D ⩾ 16) - Severe depressive symptoms (CES-D ⩾ 24) |

CES-D | 5 months: 33% of depressive symptoms; 12% of severe

depressive symptoms 9 months: 38% of depressive symptoms; 18% of severe depressive symptoms |

Infant weight; infant health; infant sleep | Higher depressive symptoms at 5 months were associated with increased infant night-time awakenings at 9 months (p = 0.001). A multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate the relationship between maternal depressive symptoms at 5 months and infant sleep at 9 months while controlling for infant sleep at 5 months. Maternal depressive symptoms at 5 months significantly predicted more problematic infant sleep at 9 months (B = 0.03, p = 0.01). |

| Tavares Pinheiro108 | Brazil Mean age: 26.2 ± 6.6 years Gender of newborns: not given |

366 | Cohort study 10 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (mild = 10–12; severe ⩾ 13) |

22.7% in direct PP 24.6% at 12 months |

Infant sleep disorders | The risk of sleep problems for children whose mothers presented with a new onset and severe depression at 12 months was higher than the risks observed among children born to mildly depressed mothers. When chronicity was considered, an additional risk of 2.20 (95% CI = 0.62, 7.86) was observed for mild and chronically depressed mothers, which was even higher (2.58; 95% CI = 1.15, 5.63) for chronic and severe cases. Moreover, a linear trend toward a higher risk of sleep problems as the severity and chronicity of the mother’s depressive symptoms increased could be observed (p = 0.05). |

| Zajicek-Farber130 | USA Age (years): Depressed: 22.3 ± 4.3 Nondepressed: 22.6 ± 3.9 Female babies: 54.0% |

134 | Cohort study 18 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |

EPDS (Depressed = EPDS ⩾ 11) PHQ |

55.2% | Infant health practices | Significantly fewer children of depressed women were placed in the recommended back-to-sleep position compared to children of women who had never experienced depression (68.9% vs 85.0%). The RR of sleeping in a “wrong” position was two times greater for children of depressed women than those of women who were never depressed. |

PPD: postpartum depression; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio.

Motor development

Three of seven studies showed a significant effect of maternal PPD on the motor development of infants (Table 9). The first study,97 conducted in Bangladesh, showed that symptoms of maternal PPD that were present at 2–3 months predicted impaired motor development in infants at 6–8 months. The second study95 included Greek mothers in Crete and demonstrated that symptoms of maternal PPD were associated with lower fine motor scores in infants at 18 months of age (a 5-unit decrease on the scale of fine motor development). The third study94 showed a nonsignificant impact of maternal depression on the fine and gross motor development of children at 2 and 6 months that became significant at 12 months for gross motor development and at 18 months for fine motor development (Pakistan). The fourth study141 underlined the indirect effect of maternal PPD on motor development as a consequence of the effects of maternal depressive symptoms on the quality of the home environment. This mechanism had a direct effect on early child development. Three studies66,103,107 demonstrated that maternal PPD had no effect on motor development (Table 9). Two studies66,107 explained the nonsignificant results by stating that most of the mothers in the depressed group had moderate-to-severe depression symptoms that were similar to a general description of psychological difficulty during the postnatal period and were less severe than a psychiatric diagnosis of a depressive illness (France and Taiwan). The third study103 emphasized that the home environment remained a significant predictor of infant development in Australia.

Table 9.

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation for motor development in children.

| First author’s name | Sociodemographic data: 1. Country 2. Maternal mean age 3. Gender of newborns |

Sample size | Design: 1. Study design 2. Time of follow-up 3. Number of groups 4. Description of groups |

Tool used to assess PPD | Prevalence of PPD | Outcomes | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali94 | Pakistan Mean age: 26.3 years Female babies: 48.8% |

420 | Cohort study 30 months Two groups: - PPD - No PPD |