Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Objects can appear remarkably stable despite the often fickle cues they provide to our senses. For instance, a foraging mouse can identify and locate a piece of cheese several meters away entirely by smell, even though the concentration of airborne “cheese” molecules varies steeply over this distance. How the brain maintains perceptual stability across such widely ranging stimulus intensities remains a fundamental, unanswered question. The response properties of olfactory sensory neurons in the mouse’s nose may provide part of the answer. With each sniff, inhaled odorant molecules activate subsets of sensory neurons that each express a single type of odorant receptor. At low concentrations, when only a few odorant molecules are present, only those cells that express the most sensitive receptors for that particular odorant will be activated. However, many cells that express lower-affinity receptors will also be activated at higher concentrations, potentially degrading the odor representation. Crucially, the sensory neurons that express high-affinity receptors will always be activated earliest in the sniff, regardless of concentration. Could the mouse’s brain exploit this temporal structure to maintain stable odor representations despite changing odorant concentrations?

RATIONALE

To test this idea, we simultaneously recorded spiking activity from olfactory bulb (OB) mitral cells, which receive input from the olfactory sensory neurons, and from their cortical targets, principal neurons (PNs) in the piriform cortex (PCx), where odor identity is encoded. PNs form extensive, long-range “recurrent” excitatory synapses with each other in addition to forming excitatory synapses on PCx inhibitory interneurons. We hypothesized that this architecture enables the earliest activated—and therefore most selective—PCx PNs to rapidly inhibit less selective PCx PNs, helping to maintain stimulus specificity across odorant concentrations. We directly tested this idea by selectively expressing tetanus toxin in PCx PNs, blocking their ability to excite other PCx neurons but leaving them responsive to OB inputs.

RESULTS

In control mice, OB responses to different odors were more correlated and were more sensitive to differences in odor concentration than responses in PCx. Individual OB neurons fired bursts of action potentials, with odor-specific latencies and prolonged responses that were strongly concentration-dependent. By contrast, PCx PNs were briefly excited immediately after inhalation and then rapidly truncated by strong and sustained Suppression. To identify the source of this suppression, we recorded from feedforward and feedback inhibitory interneurons in PCx. Feedforward interneurons, which are excited exclusively by OB inputs, exhibited little odor-evoked activity. By contrast, feedback interneurons, which are excited by PCx PNs but not by OB, showed robust and sustained spiking that mirrored PN suppression, indicating that PCx itself controls the timing and strength of its own suppression. We eliminated this intracortical communication by silencing recurrent excitatory synapses in PCx with tetanus toxin. This amplified and prolonged PCx PN responses, rendered their responses steeply concentration-dependent, and abolished the ability to stably predict odor identity across concentrations from PCx spiking activity.

DISCUSSION

The PCx cells that respond earliest after inhalation represent the most odorant-specific and concentration-invariant features of the odor. The extensive, long-range recurrent circuitry broadcasts their activation across PCx, recruiting strong, sustained global inhibition that then suppresses subsequent cortical activity. Recurrent circuitry therefore effectively amplifies the impact of the earliest arriving OB inputs and discounts the impact of less-selective inputs that arrive later. Thus, the recurrent circuitry in the PCx acts as a precisely timed gate to ensure that only the most salient information is relayed further into the brain to guide the mouse’s behavior.

Animals rely on olfaction to find food, attract mates, and avoid predators. To support these behaviors, they must be able to identify odors across different odorant concentrations. The neural circuit operations that implement this concentration invariance remain unclear.We found that despite concentration-dependence in the olfactory bulb (OB), representations of odor identity were preserved downstream, in the piriform cortex (PCx).The OB cells responding earliest after inhalation drove robust responses in sparse subsets of PCx neurons. Recurrent collateral connections broadcast their activation across the PCx, recruiting global feedback inhibition that rapidly truncated and suppressed cortical activity for the remainder of the sniff, discounting the impact of slower, concentration-dependent OB inputs. Eliminating recurrent collateral output amplified PCx odor responses rendered the cortex steeply concentration-dependent and abolished concentration-invariant identity decoding.

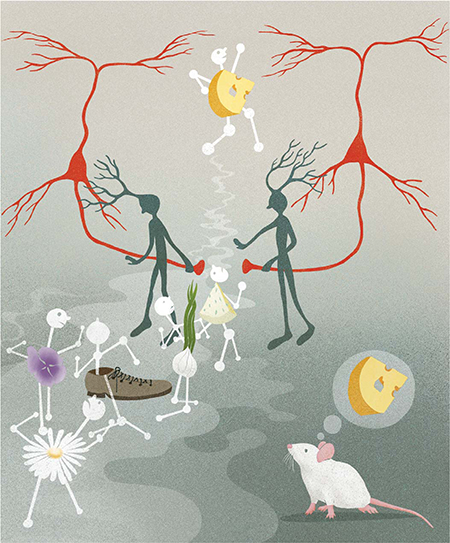

Graphical Abstract

Whenever a mouse inhales, volatile molecules activate odorant receptors in the nose, evoking sequences of activity in the olfactory bulb. Bulb cells driven by the most specific receptors, which therefore best represent the odor stimulus (cheese), will always respond earliest. When this information is relayed to piriform cortex, activated principal neurons (red cells) recruit inhibitory neurons (green cells) that then suppress cortical responses to subsequent, less-specific olfactory bulb input (such as garlic, shoe, or flower), preserving the identity of the stimulus.

Although the ability to reliably identify objects over a large range of stimulus intensities is a fundamental feature of all sensory systems, the neural mechanisms that implement intensity invariance remain poorly understood. At the earliest stages of processing, odor responses scale steeply with odorant concentration (1–4). However, psychophysical studies indicate that odors typically retain their perceptual identities, whereas concentration varies over several orders of magnitude (5–7). The olfactory system must therefore transform concentration-dependent odor responses encoded at early stages of processing into concentration-invariant representations of odor identity.

In the olfactory bulb (OB), odor-responsive mitral and tufted cells fire bursts of action potentials with odor-specific latencies that tile the ~500-ms respiration cycle (8–11). Odor information is then diffusely projected from the OB to the piriform cortex (PCx), so that individual PCx neurons can integrate inputs from different combinations of OB glomeruli, producing odor-specific ensembles of neurons distributed across the PCx whose concerted activity encodes odor identity (12–16). Theoretical studies have suggested that the PCx can form concentration-invariant odor representations by selectively responding to the earliest-active OB inputs while ignoring the contribution of inputs arriving later, which may reflect more spurious activation of lower-affinity receptors (17–22). Specifically, at low odorant concentrations, only those glomeruli innervated by receptors with the highest affinity will be activated; at higher concentrations, more glomeruli may be activated, but the highest affinity glomeruli will be most strongly activated, and the mitral and tufted cells that innervate those glomeruli will therefore always be activated earliest in the sniff. A concentration-invariant odor representation could be formed if downstream areas selectively attended to the earliest OB inputs and discounted OB inputs that occur later in the sniff (23–25). How such a “temporal winner-take-all”-type filter would be implemented within the PCx is not known.

Concentration-invariance emerges in the PCx

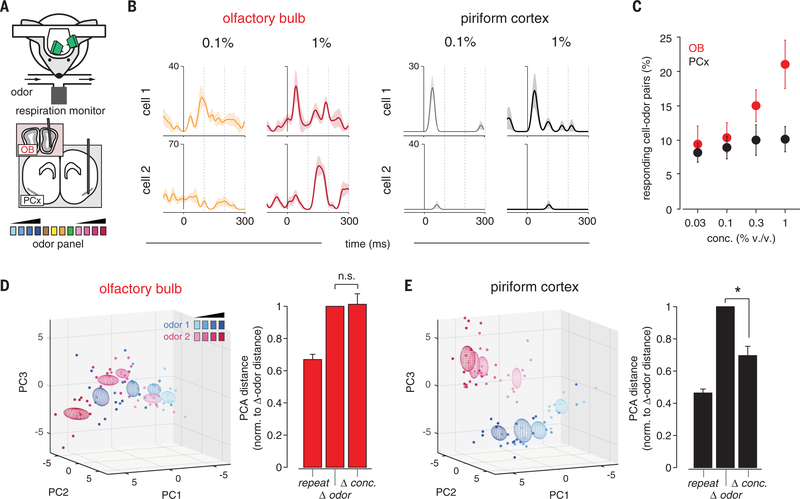

To address this question, we simultaneously recorded spiking in populations of mitral cells and ipsilateral PCx principal cells in awake, head-fixed mice in response to different odorants presented at multiple concentrations (Fig. 1A). At low concentrations, odors activated small and specific subsets of cells in both the OB and PCx (Fig. 1B). Many OB cells that were not responsive at lower concentrations became responsive at higher concentrations, whereas responses were more stable across concentrations in the PCx (Fig. 1, B and C). We characterized the concentration-dependence of population responses by constructing trial-by-trial response vectors composed of spike counts for each cell in populations of OB and PCx cells (Materials and methods). We then projected these high-dimensional responses onto their three principal components (Fig. 1, D and E). We quantified the variance of responses to an odor at different concentrations (Δ conc.) and compared these to the variance for repeated presentations of each odor at a single concentration (repeat) and for responses to different odors (Δ odor): distances in PCA space for repeat and Δ odor responses place upper and lower bounds, respectively, on the concentration-invariance of Δ conc. responses. Crucially, Δ conc. responses and Δ odor responses were equally variable in the OB (Fig. 1D), whereas Δ conc. responses in the PCx were significantly less variable than Δ odor responses (Fig. 1E), indicating that concentration-invariance emerges in the PCx. This result was robust when response distances were measured in all-neural space instead of PCA space (fig. S1). Given that PCx is driven directly by the OB, this result indicates that the PCx extracts and selectively represents the most concentration-invariant features of its OB inputs while discounting the impact of more concentration-dependent inputs.

Fig. 1. Concentration-invariant odor representations emerge in PCx.

(A) Experimental schematic. Odor panel included four odors at a single concentration and two odors at four concentrations. (B) Example responses from simultaneously recorded pairs of (left) OB or (right) PCx cells to two odors at different concentrations. Responses are aligned to start of inhalation. (C) Percent of cells significantly activated by odors of increasing concentration (P < 0.05 rank-sum test, odor vs mineral oil) in the OB (red) or PCx (black, n = 5 simultaneous OB-PCx recordings, two odors, four concentrations). (D) (Left) PCA representation of OB pseudopopulation (n = 94 cells) response in a 330-ms window after inhalation to ethyl butyrate (blue) and hexanal (magenta) at different concentrations (0.03 to 1%, different shades). Dots represent responses on individual trials; ellipsoids are mean ± 1 SD. (Right) Relative population response distances in neural activity space projected onto the first three principal components. Distances were computed for each stimulus between trials of the same odor and concentration (repeat, n = 12 stimuli), different odors (Δ odor, n = 12 stimuli), or same odor and different concentration (Δ conc., n = 8 stimuli), and normalized to the average Δ odor distance. OB responses to different concentrations were as dissimilar as responses to different odors (one-sample t test versus mean of 1, P = 0.851). (E) As in (D), but for PCx pseudopopulation (n = 330 cells). PCx responses to different concentrations were more clustered than responses to different odors (P = 0.001).

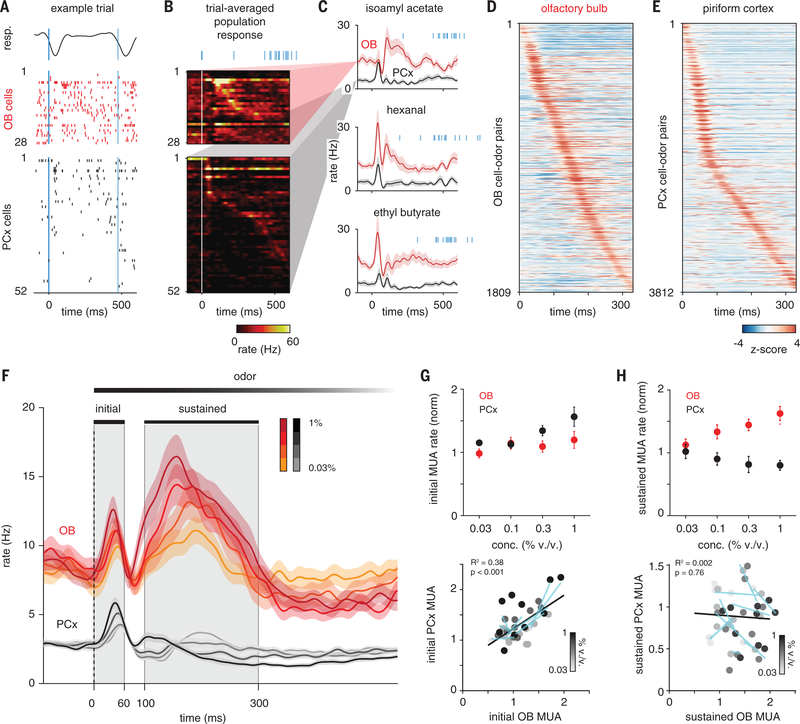

Fig. 2. PCx predominantly responds to early OB inputs.

(A) Example single-trial response to isoamyl acetate (0.3% v/v) in populations of simultaneously recorded OB and PCx cells. Negative-going respiration signal (top) indicates inhalation. Bold blue line marks start of first inhalation after odor onset. Thin blue line marks second inhalation. Cells in each population are sorted by trial-averaged response peak latency. (B) Example trial-averaged peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) for populations in (A). Blue lines indicate inhalation times on all 15 trials. (C) Average PSTHs for same OB and PCx populations responding to three odors. Shading is SEM across cells. (D) PSTHs for all OB cell-odor pairs sorted by latency to peak show uniform tiling of sniff cycle. (E) Same as (D) but for PCx. Majority of PCx responses occur within 60 ms after inhalation. (F) Average PSTHs for all cell-odor responses at different concentrations (OB, n = 188; PCx, n = 664 cell-odor pairs; mean ± SEM). Gray shading indicates initial (0 to 60 ms) and sustained (100 to 300 ms) analysis windows. Dashed line indicates inhalation onset. (G) Normalized multiunit activity (MUA) rates during initial phase (n = 5 experiments, two odors, four concentrations) in OB versus PCx. MUA is determined by recombining individual cell responses. (Top) Average OB (red) and PCx (black) response across recordings and odors. MUA was normalized to baseline activity 1 s before odor. (Bottom) Each point is the average response of one simultaneously recorded OB-PCx population response pair. Shading indicates concentration. Cyan lines are linear fits across concentrations for each OB-PCx population response pair. Black line is the linear fit to all data. (H) As in (G) but for the sustained phase.

We next examined response dynamics to understand how the PCx implements this filter. Over the course of a single sniff, odor-responsive mitral cells fired bursts of action potentials [full-width at half-maximum duration (mean ± SD), 70.6±49.3 ms; n = 1830 cell-odor pairs at 0.3%v/v] with different latencies after inhalation onset. Spiking activity was more sparse in the PCx, with neurons typically responding more briefly (46.7 ± 27.0 ms; n = 4197 cell-odor pairs; P = 5.06 × 10−90, two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) shortly after inhalation (Fig. 2, A to C). Across the population, individual OB mitral cells responded with peak latencies that uniformly tiled the sniff cycle (Fig. 2D) (8–10), whereas >50% of PCx responses occurred within the first 60 ms after inhalation (Fig. 2E). In the OB, population activity—determined by averaging responses for all cell-odor pairs—showed a brief initial increase in spiking followed by a slower and sustained envelope of spiking activity (Fig. 2, C and F). However, in the PCx we only observed a transient increase in population spiking that was rapidly truncated and followed by suppression that sustained over the remainder of the sniff, despite continuing input from OB.

We then examined OB and PCx responses at different concentrations. OB spiking increased systematically with concentration, with sustained responses being especially concentration dependent (Fig. 2, G and H). Peak amplitude of the initial cortical population response increased as the ensemble of responsive PCx cells was activated more synchronously at higher concentrations; however, the ensembles themselves were largely concentration invariant (15). Beyond the initial phase, and for the remainder of the sniff, spiking in the PCx was more strongly suppressed at higher concentrations, despite receiving more input from OB. Thus, the PCx preserves odor representations across odorant concentrations by suppressing its response to later OB inputs that are especially concentration dependent.

Feedback inhibition truncates PCx odor responses

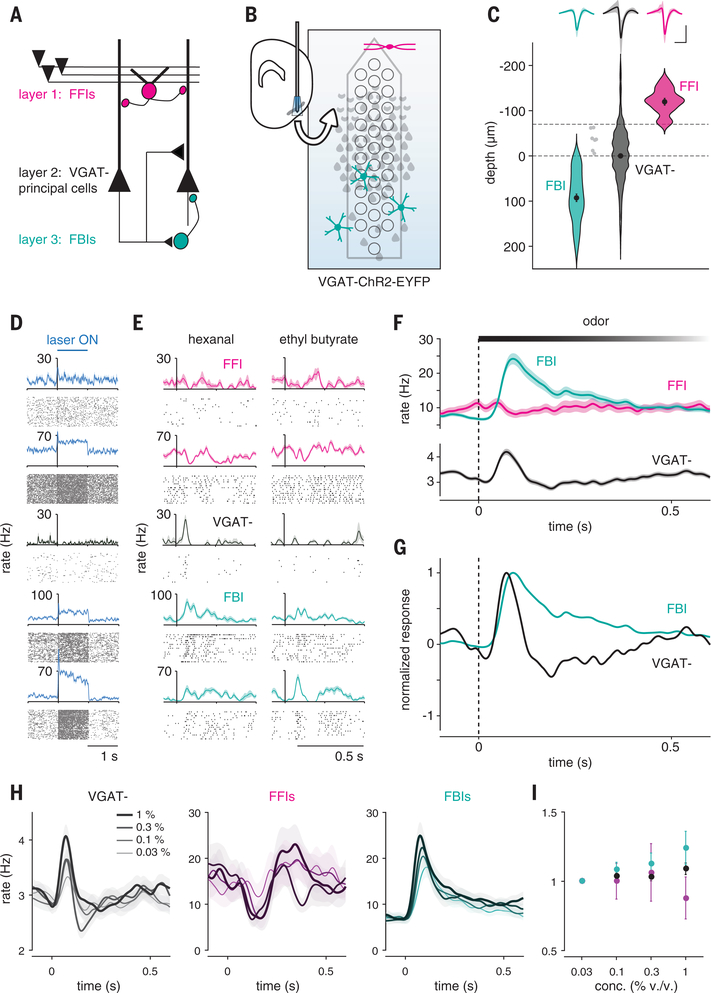

What is the source of this suppression? Principal neurons in the PCx receive inhibitory inputs from two general classes of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic interneurons. Feedforward interneurons reside in layer 1 and only get direct excitatory input from the OB (Fig. 3A). These neurons are well positioned to suppress responses to sustained OB input (26–29). However, PCx principal cells (both semilunar cells and pyramidal cells) extend long-range projections across the cortex, providing excitatory input onto other PCx pyramidal cells as well as onto feedback interneurons that reside in deep layer 2 and layer 3 (26, 29–31). We took advantage of the laminar segregation of feedforward and feedback inhibitory interneurons and used an optical tagging approach to compare odor responses in these two distinct populations of interneurons. We recorded from neurons that were deep or superficial to the large population of glutamatergic principal cells in layer 2 in vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT)–ChR2–green fluorescent protein (GFP) mice, in which all GABAergic interneurons express channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) (32) (Fig. 3B). Light pulses evoked robust and sustained spiking in ~7% of cells (66 of 921 cells, n = 15 recordings), which is consistent with these cells being VGAT+ inhibitory interneurons, whereas spiking in the remaining cells was either significantly suppressed (639 of 921 cells) or unaffected (216 of 921 cells). We classified cells as layer 1 feedforward interneurons (FFIs) (n = 13 of 66 VGAT+ neurons) or layer 2/3 feedback interneurons (FBIs) (n = 46 of 66 VGAT+ neurons) according to their dorsoventral (DV) position relative to the dense population of VGAT− principal cells in layer 2 (Fig. 3, C and D). Seven VGAT+ neurons could not be clearly classified as FFIs or FBIs and were excluded. Spike waveforms of FBIs were narrower than VGAT− cells and more symmetrical than both VGAT− and FFIs (Fig. 3C and fig. S2), which is consistent with a subset of these being fast-spiking interneurons. Spontaneous firing rates in FFIs and FBIs were significantly higher than those in VGAT− cells (fig. S2).

Fig. 3. Feedback inhibition shapes cortical odor responses.

(A) Schematic of PCx circuit: FFIs in layer 1 receive OB input; principal cells in layer 2 provide recurrent excitatory input to other principal cells and to FBIs in layer 3. (B) Recording schematic. Light-responsive FFIs and FBIs in VGAT-ChR2 mice are differentiated by their depths relative to VGAT− principal cells in layer 2, which are suppressed. (C) FFIs (magenta, n = 13), FBIs (teal, n = 46), and VGAT− (black, n = 855) are classified by light-responsiveness and depth (dashed line). Dots with error bars are mean ± SEM. Light gray indicates unclassified light-responsive cells. (Top) Average waveform of each cell type (mean ± SEM). Scale bars, 0.5 ms, 0.1 mV. (D) Example light responses for one PC (black) and four cells classified as FFIs or FBIs (blue). (E) Example odor responses for cells in (D). (F) Average population PSTHs (mean ± SEM) for each cell type. (G) Normalized PSTHs for FBIs and VGAT− cells. (H) Average population PSTHs for (left) VGAT−, (middle) FFIs, and (right) FBIs responding to odors at increasing concentrations. (I) Normalized firing rates in response to increasing odor concentrations for each cell type (mean ± SEM).

In response to odors, we observed shortly after inhalation a large and rapid increase in FBI spiking that peaked just as spiking in principal cells was sharply suppressed and remained elevated for the duration of the sniff (Fig. 3, E to G). Odor-evoked spiking in FFIs increased slowly and only slightly after inhalation, suggesting that FFIs may provide tonic inhibition driven by spontaneous OB input but do not play a major role in shaping phasic, odor-evoked cortical responses. This result is not entirely unexpected because although these cells do receive broadly tuned OB input, they are even more broadly self-inhibited (28). Moreover, spiking in FBIs, but not FFIs, increased systematically with concentration (Fig. 3, H and I), suggesting that they play the major role in normalizing PCx output, which is consistent with predictions from our recent modeling study (25). Thus, FBIs appear to play the dominant role in truncating and suppressing odor-evoked activity in the PCx. Because FBIs do not get OB input but instead are recruited by intracortical recurrent collateral connections, these data indicate that it is PCx activity itself that initiates its subsequent, rapid suppression, determining what OB information is transmitted and what information is effectively ignored.

Strategy to eliminate recurrent excitation

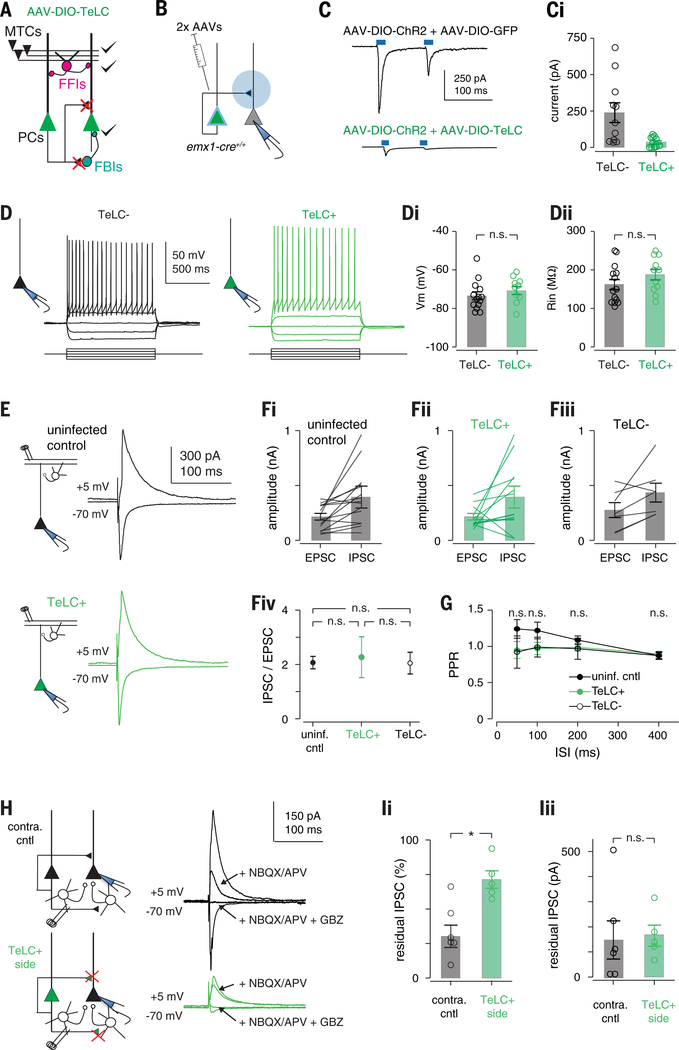

Piriform pyramidal cells receive approximately 10 times more recurrent inputs than OB inputs, and recurrent connections are thought to provide much of the excitatory drive onto odor-responsive cells (33, 34). However, because recurrent excitation also recruits FBIs, recurrent circuitry may actually exert a net inhibitory effect on PCx activity (25). We developed a cortical muting strategy in order to distinguish between these alternatives. We selectively expressed tetanus toxin light chain (TeLC) in principal cells using cre-dependent adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) injected into the PCx of emx1-cre mice. TeLC expression should block transmitter release from PCx principal cells but should not alter their excitability. This strategy would allow us to record OB-driven spiking in the PCx, without affecting FFI, after blocking their ability to excite one another or recruit FBI (Fig. 4A). To validate this method, we first focally injected cocktails of two AAVs conditionally expressing ChR2 and either GFP or TeLC-GFP into a small region of the anterior PCx (Fig. 4B). We then isolated acute brain slices from these mice and obtained voltage-clamp recordings from uninfected cells. Brief light pulses above the recorded cell evoked large, monosynaptic responses in ChR2/GFP slices by activating recurrent excitatory inputs from other infected PCx neurons (31). However, light-evoked responses were almost completely abolished in ChR2/TeLC-GFP slices (Fig. 4C). Light drove robust spiking in ChR2/GFP and ChR2/GFP-TeLC-positive cells. In a separate set of control experiments, we expressed TeLC-GFP alone throughout the PCx. In current-clamp recordings, we verified that TeLC expression did not alter neural excitability (Fig. 4D). In voltage-clamp recordings, electrical stimulation of OB axons evoked equivalent monosynaptic excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) and disynaptic feedforward inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) in TeLC-expressing cells, uninfected neighboring cells, and in cells from uninjected control slices, indicating that both OB input and FFI are unaffected by TeLC expression in the PCx (Fig. 4, E to G). Last, we examined responses to electrically stimulating recurrent axons in layers 2 and 3. Both EPSCs and disynaptic IPSCs were reduced in TeLC-infected slices. However, direct IPSCs, evoked by means of direct stimulation of FBIs after application of glutamate receptor antagonists, were equivalent, indicating that TeLC blocks transmitter release onto both other PCx principal cells and FBIs but does not block feedback inhibition (Fig. 4, H and I).

Fig. 4. TeLC expression selectively abolishes recurrent excitation.

(A) Schematic of circuit changes after TeLC expression in PCx principal cells. (B) Focal coinfection in PCx with ChR2 and either GFP or TeLC-GFP, followed by whole-cell recordings from uninfected cells. Light-evoked synaptic responses are abolished by TeLC. Example light-evoked response from non-ChR2–expressing neurons in (top) GFP- or (bottom) TeLC-GFP–infected PCx. i Light-evoked EPSC amplitudes in control and TeLC-expressing PCx (control: 239 ± 68 pA, n = 11 cells from two mice; TeLC 35 ± 10 pA, n = 12 cells from three mice; unpaired t test, P = 0.0133). (D) Example recordings from an (left) uninfected and (right) TeLC-infected neuron in the same slice in response to 50 pA current steps. (i) Resting membrane potentials (TeLC−, 73.4 ± 2.03 mV, n = 14 cells from three mice; TeLC+, 70.7 ± 2.01 mV, n = 11 cells from two mice; unpaired t test, P = 0.335) and (ii) input resistances (TeLC−, 162 ± 13.3 megohm; TeLC+, 188 ± 13.8 megohm; P = 0.188) were equivalent. (E) Synaptic inputs from OB are unaffected. Example recordings of EPSCs [membrane voltage (Vm), −70 mV] and disynaptic feedforward IPSCs (Vm, +5 mV) evoked by means of electrical stimulation of the lateral olfactory tract (LOT) in (top) an uninfected control slice or (bottom) a TeLC-infected neuron. Both EPSCs and IPSCs were blocked by 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoylbenzo[f]quinoxaline (NBQX) (10 μM) and D,L-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV) (50 μM, not shown). (F) Summary of LOT-evoked EPSC and IPSC amplitudes from (i) uninfected control slices, (ii) TeLC+ neurons and (iii) TeLC− neurons in TeLC-infected slices. (iv) EPSC/IPSC ratios were equivalent in all conditions; P > 0.05, unpaired t tests. (G) LOT EPSC paired-pulse ratios were not significantly altered after TeLC expression. n.s., not significant. (H) Example recordings showing recruitment of FBI is impaired, whereas FBI is unaffected. EPSCs and IPSCs were evoked by electrical stimulation of layer 2/3 226 ± 17 μm from recorded cell. EPSCs and IPSCs were attenuated in TeLC-infected slices. Blocking glutamate receptors with NBQX and APV eliminates the disynaptic component of IPSCs, with the residual IPSC evoked through direct stimulation of FBIs. The residual IPSC was fully blocked by gabazine (GBZ) (10 μM). (I) Summary of residual IPSC amplitudes. (i) The fractional size of residual IPSCs after NBQX/APV was substantially smaller in TeLC-infected slices (control, n = 6 cells from three mice; TeLC, n = 6 cells from three mice; unpaired t test, P = 0.0055), but (ii) the amplitudes of residual IPSCs were equivalent (P = 0.957).

Recurrent excitation suppresses odor responses

To unilaterally eliminate recurrent circuitry, we injected AAV-DIO-TeLC-GFP at three different locations along the rostro-caudal axis, uniformly infecting ~60% of principal neurons across the PCx (Fig. 5, A and B, and fig. S3). We then recorded odor responses simultaneously in the PCx from infected and contralateral control hemispheres (Fig. 5C). Spontaneous firing rates in TeLC-infected (TeLC-PCx) and contralateral control hemispheres were similar. Population spiking was more strongly coupled to the respiration cycle in both TeLC-PCx and ipsilateral OB, indicating that cortical network activity normally desynchronizes spiking in both the PCx and OB (fig. S4). Despite eliminating much of its excitatory input, odor responses in TeLC-PCx were enhanced, increasing steeply after inhalation and remaining elevated for the duration of the sniff (Fig. 5, D to E). Spiking in simultaneously recorded contralateral control hemispheres was truncated shortly after inhalation and suppressed thereafter, as before. Two factors underlie this enhanced population response: first, a given odor activated more and suppressed fewer cells across the population in TeLC-PCx; second, activated responses were larger and of longer duration in TeLC-PCx (fig. S5). We next examined how responses changed across concentrations after eliminating recurrent circuits. Gain control through divisive normalization is often thought to be implemented by feedforward inhibition (35). If FFIs control the gain of cortical odor responses, then PCx output should remain stable across concentrations. However, response gain was markedly increased in TeLC-PCx, confirming the major role for feedback inhibition in controlling PCx output. Gain increased even though odor responses at the lowest concentrations were already considerably larger in TeLC-PCx (Fig. 5, F and G). PCx output remained constant across concentrations in contralateral control hemispheres.

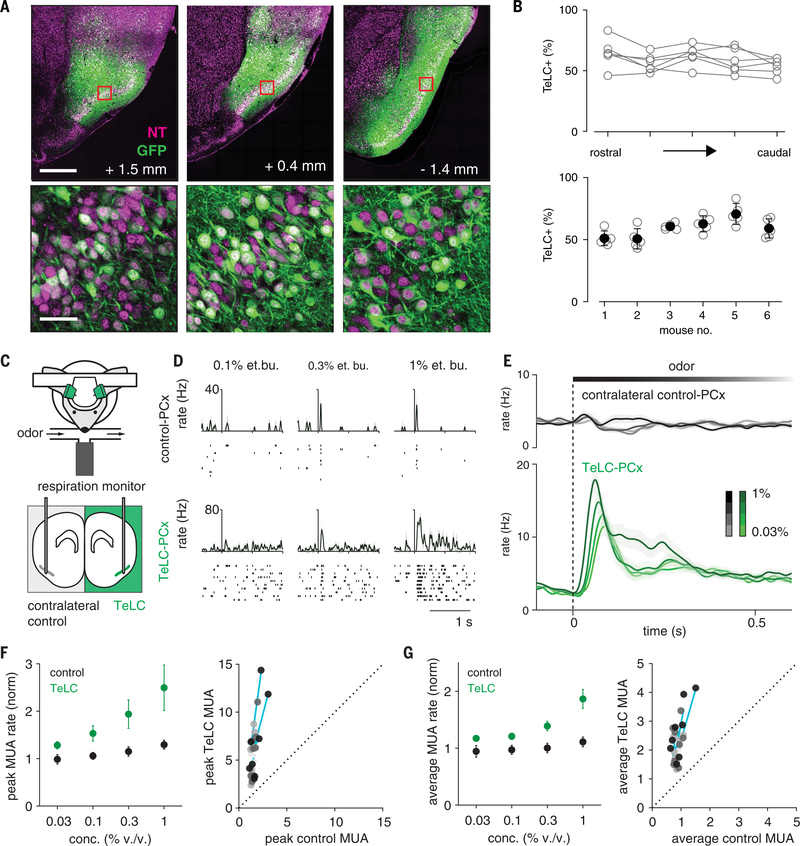

Fig. 5. Recurrent circuitry truncates and normalizes cortical output.

(A) Extensive infection of layer 2 principal cells across PCx in an example mouse. GFP, green; NeuroTrace, magenta. Numbers indicate distance from bregma. Bottom row are the square sections from the top row. Scale bars, 500 μm (top) and 50 μm (bottom). (B) Percent cells expressing TeLC-GFP in six of seven mice used. Sections from one mouse were damaged, and infection could not be quantified. (Top) TeLC infection across rostral-caudal PCx. (Bottom) Low variation in TeLC expression across mice. (C) Experimental schematic. Simultaneous bilateral recordings from TeLC-infected and contralateral control hemisphere with odor stimuli. (D and E) Example responses (D) and average population PSTHs (E) (mean ± SEM; control, n = 450 cell-odor pairs; TeLC, n = 388 cell-odor pairs) (F) Normalized peaks in MUA rates (n = 4 experiments, two odors, four concentrations). (Left) Peak responses across recordings and odorant concentrations. (Right) Each point is average response of one simultaneously recorded TeLC-Control PCx pair normalized to mineral oil response. Shading indicates concentration. Cyan lines are linear fits for each experiment through all concentrations. (G) As in (F) but for average rate over the first 330 ms after inhalation.

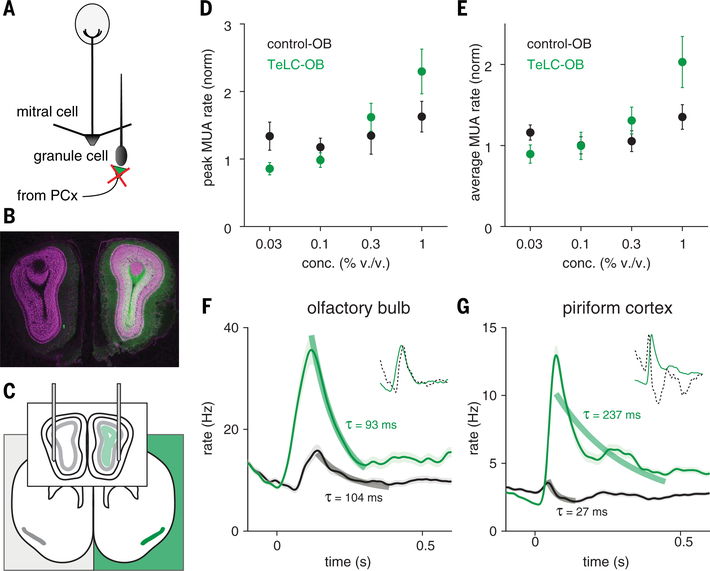

But TeLC will block transmitter release from all synapses in infected cells, including centrifugal projections back to the OB, as well as to downstream target areas. Centrifugal inputs from PCx contact GABAergic OB neurons that can suppress mitral and tufted cell output (36–38), and this process would also be disrupted after TeLC infection (Fig. 6A). Indeed, we observed GFP expression in OB ipsilateral to AAV injection (Fig. 6B). To determine whether the large, prolonged responses observed in TeLC-PCx were simply a consequence of enhanced OB input, we recorded OB responses ipsi- and contralateral to TeLC-PCx (Fig. 6C). Ipsilateral OB responses were larger than contralateral controls and increased more steeply at higher concentrations (Fig. 6, D to F). However, although both the amplitude and the gain of OB responses were larger after centrifugal inputs were blocked with TeLC, the time course of the response was unaffected. This contrasts with the markedly prolonged responses in TeLC-PCx (Fig. 6G), indicating that centrifugal inputs play an important role in modulating OB response amplitude and gain but suggesting that the rapid truncation and sustained suppression of PCx activity is predominantly an intracortical process.

Fig. 6. Centrifugal inputs from PCx control gain but not time course of OB responses.

(A) Schematic of circuit changes in OB after TeLC expression in ipsilateral PCx principal cells. (B) Centrifugal PCx fibers expressing TeLC in OB ipsilateral to PCx infection. GFP, green; NeuroTrace, magenta. (C) Experimental schematic. Simultaneous bilateral recordings from OB ipsilateral and contralateral to TeLC-infected PCx with odor stimuli. (D) Peaks in OB MUA rates averaged across population-odor pairs (n = 3 experiments, two odors, four concentrations). Odor responses are normalized to mineral oil responses. (E) As in (D) but for average rate over the first 330 ms after inhalation. (F) Average PSTH of all OB cell-odor pairs in control (black, n = 406) or TeLC (green, n = 384) side responding to odor (mean ± SEM). Thick lines are exponential fits to decay from peak to minimum. (Inset) Rescaled control OB response (dotted line) overlaid on TeLC-OB response. Response dynamics are similar in control and TeLC hemisphere despite change in response gain. (G) Same as (F) but for PCx (control, n = 1660; TeLC, n = 1532). Here, decay constants differ by an order of magnitude between control and TeLC hemisphere.

PCx responds selectively to the earliest-activated OB inputs

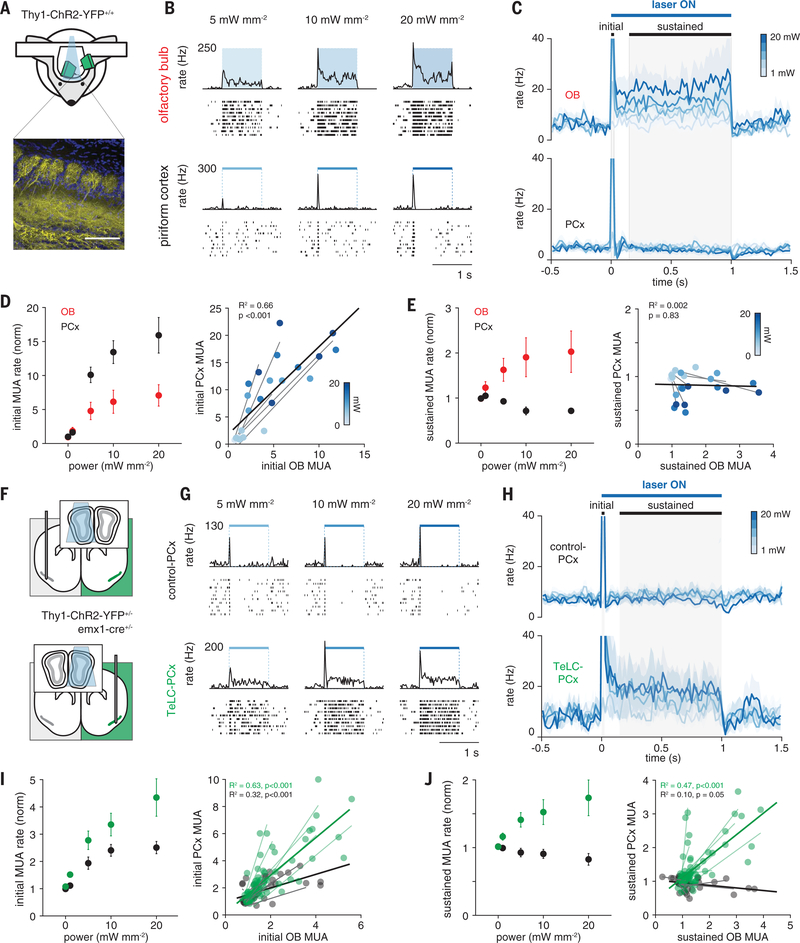

To circumvent the contribution of centrifugal inputs and other intrabulbar processes that can normalize odor responses (39–41), and to isolate the intracortical processes that shape PCx odor responses, we used an optogenetic approach to stimulate OB directly. We presented 1-s light pulses above the OB of Thy1-ChR2-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) mice, which express ChR2 in mitral and tufted cells (42) (Fig. 7A). We illuminated the dorsal surface of the OB while recording from mitral cells near the ventrolateral OB surface, providing a lower-bound estimate of the change in total OB output. Light pulses elicited an increase in OB spiking that scaled with light intensity and remained elevated for the duration of the stimulus (Fig. 7, B to E). This sustained OB activation only produced a large initial peak in PCx population spiking that rapidly returned to baseline for the remainder of the light pulse (Fig. 7C). Although initial peak spike rate in the PCx increased steeply at higher light intensities (Fig. 7D), sustained population activity was systematically suppressed at higher stimulation intensities (Fig. 7E). As the light pulse ended, the sudden drop in input from the OB produced a transient dip in population PCx spiking, which quickly returned to baseline. Thus, PCx dynamically compensates for changes in excitatory drive with rapid recurrent inhibition that balances excitatory input and controls gain to stabilize total cortical output across input intensities. These experiments also demonstrate directly that PCx responds robustly to the earliest-activated OB inputs and then suppresses its output, discounting the impact of OB inputs that arrive later. To reveal the role of recurrent circuits in implementing this transformation, we repeated these experiments in Thy1-ChR2-YFP+/−/emx1-Cre+/− mice with unilateral TeLC expression (Fig. 7F). Direct OB stimulation now drove sustained spiking in TeLC-PCx that scaled with intensity (Fig. 7, G to J), whereas responses recorded in contralateral hemispheres were similar to what we observed in uninfected, control PCx.

Fig. 7. PCx truncates sustained input from OB.

(A) Simultaneous OB-PCx recordings with direct optical OB activation. (Top) Experimental schematic. (Bottom) ChR2 expression in mitral cells. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Responses from example (top) OB and (bottom) PCx cells to 1-s light pulses over OB. (C) Average population PSTHs for responses from experiment in (B). Gray shading indicates initial and sustained analysis windows. (PCx time constants for 20 mW light pulses; decay from peak, 18.9 ± 2.0 ms; recovery from post-stimulus trough, 87.4 ± 46.3 ms; n = 5 population recordings.) (D) Normalized MUA rates during initial phase (n = 5 experiments) in OB versus PCx. (Left) Average OB (red) and PCx (black) responses across recordings. MUA was normalized to baseline activity 1 s before stimulation. (Right) Each point is the average response of one simultaneously recorded OB-PCx response pair. Shading indicates light intensity. Light gray lines are linear fits for each OB-PCx population pair. Black line is the linear fit to all data. (E) As in (D) but for the sustained phase. (F) Experimental schematic. Simultaneous OB-PCx recordings from TeLC-infected or contralateral control hemisphere with optical OB activation. (G) Example responses from cells to 1-s light pulses over OB. (H) Average population PSTHs for responses from experiments in (G). (I) Normalized peak MUA rates during initial phase (n = 13 TeLC and 8 control experiments) in OB versus PCx. (Left) Average TeLC-PCx (green) and contralateral control PCx (black) MUA rates. (Right) Each point is the average response of one simultaneously recorded OB-PCx pair at one intensity. Light lines are linear fits for each TeLC (green) or control (gray) OB-PCx population pair. Solid lines are linear fits for all TeLC (green) and control (black) data. (J) As in (I) but for sustained rate.

Recurrent circuitry is required for concentration-invariant decoding

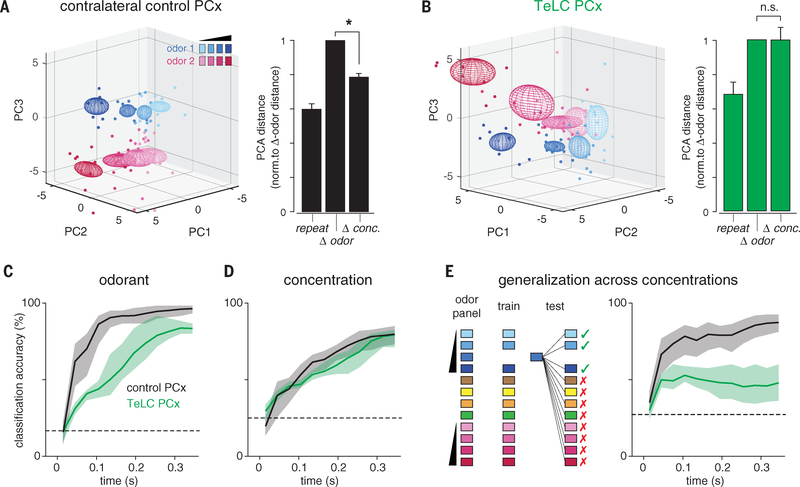

Next, we asked how eliminating recurrent connectivity alters population odor coding. We performed principal components analysis (PCA) on single-trial population response vectors from contralateral control or TeLC-PCx recordings and calculated the distances between responses in principal component space, as before. In contralateral PCx, Δ conc. responses were only slightly more variable than repeat responses to a single concentration and significantly less variable than Δ odor responses (Fig. 8A), which is consistent with results in unperturbed PCx (Fig. 1E). Δ conc. responses in TeLC-PCx were much more variable than repeat responses and as variable as Δ odor responses (Fig. 8B), which is equivalent to what we observed in the OB under control conditions (Fig. 1E). Again, this result was also robust when computed in all-neural space (fig. S6). Last, we asked how and when odor information becomes available to a downstream observer and how this is altered when recurrent circuitry is removed. We trained and tested a linear classifier on three decoding tasks: classifying responses to different odorants, classifying responses to a single odorant at different concentrations, and generalizing for odor identity across odorant concentrations (Fig. 8, C to E). Input to the classifier consisted of spike counts for each neuron in an expanding series of 20 ms bins starting with inhalation onset (9). Decoding accuracy using responses recorded from the contralateral control hemisphere increased rapidly after inhalation and remained elevated for the duration of the sniff when classifying responses to different odorants or when generalizing for odor identity; concentration decoding was delayed and increased more slowly over the full sniff. These results are consistent with our previous findings in control mice (15).

Fig. 8. Recurrent circuits implement concentration-invariant decoding.

(A) (Left) PCA representation of pseudopopulation responses for contralateral control PCx hemispheres. (Right) Mean distance between population responses in PCA space normalized to Δ odor responses. Δ conc. responses were more similar than Δ odor responses in the control PCx (one-sample t test versus mean of 1, P = 2.03 × 10−5). (B) As in (A), but for TeLC-PCx. Δ conc. responses were no more similar than Δ odor responses (P = 0.985). (C) Linear classifier performance for odorant decoding (choose 1 of 6 odors) using TeLC-infected (green) or contralateral control (black) PCx pseudopopulations. Classifier was trained and tested on spike counts in 20-ms bins in an expanding time window starting at odor inhalation. Pseudopopulation size in both conditions was held at 180 cells. Mean ± 95% confidence intervals from 200 permutations. Dashed line is chance accuracy. (D) Same as (C) for classification of different concentrations of the same odorant (choose 1 of 4 dilutions). (E) Accuracy for generalization task in which classifier is trained and tested on different concentrations of odors. Loss of recurrent circuits severely impairs odor identity recognition across concentrations.

Eliminating recurrent circuitry impaired classification of responses to different odorants, with decoding accuracy improving slowly but steadily over the duration of the sniff (Fig. 8C). This result suggests a more constructive role for recurrent circuitry in stabilizing or “completing” representations by using partial or incomplete input, although further work is required to demonstrate this effect unequivocally. Concentration decoding performance was equivalent in control and TeLC-PCx (Fig. 8D). This result may seem unexpected, given that TeLC-PCx responses are steeply concentration dependent. However, we have previously shown that spike time information is required for accurate concentration decoding in PCx (15). If instead we discard temporal information by classifying using only total spike counts, then concentration decoding deteriorates in control but not TeLC-PCx, suggesting that recurrent circuits compensate for lower gain by helping maintain spike time precision. Eliminating recurrent circuits effectively abolished the ability to generalize for odor identity; decoding accuracy increased slightly immediately after inhalation, but there was no subsequent improvement and, if anything, a small decrease in decoding accuracy as the sniff progressed (Fig. 8E).

We interpret these results to indicate that cortical responses to different odors remain somewhat distinct across the entire sniff but that only the earliest PCx responses convey concentration-invariant, identity-specific odor information. In control hemispheres, the relative impact of these early cortical responses is amplified by broadcasting their activity across PCx via long-range recurrent collateral connections that recruit feedback inhibitory neurons and, consequently, rapidly and globally suppress subsequent cortical activity for the duration of the sniff. However, when recurrent output is blocked, the early responses cannot suppress consequent activity, and so the PCx continues to be driven by OB inputs that convey decreasingly identity-specific and more concentration-dependent information as the sniff progresses (22). Ultimately, we want to know whether disrupting this circuitry abolishes concentration-invariant odor perception. However, TeLC expression in principal neurons blocks transmitter release from all their synapses, which eliminates PCx outputs and therefore precludes behavioral testing. Moreover, direct silencing of feedback interneurons will result in regenerative epileptogenic activity in this highly recurrent circuit. Therefore, development of optogenetic or chemogenetic effectors that can be efficiently targeted to defined subsets of synapses will be required to reveal the behavioral consequences of disrupting recurrent connectivity.

We revealed an essential role for recurrent feedback inhibition in preserving representations of odor identity across odorant concentrations. The combination of recurrent excitation and feedback inhibition implements a “temporal winner-take-all” filter to extract and selectively represent the most concentration-invariant features of the odor stimulus. This process emphasizes the earliest and most odor-specific inputs to the PCx. Similar types of “first-spike” coding strategies have been identified in other sensory systems (43–47). Because sensory representations are topographically ordered in these neocortical sensory areas, local surround inhibition can implement this temporal filter (48, 49). However, odor ensembles are distributed across millimeters of PCx and lack any discernible topographic organization (13, 16). Consequently, diffuse, long-range recurrent collateral projections that recruit strong feedback inhibition ensure that recurrent inhibition is global in the PCx (31). This global inhibition truncates activity, sparsens responses, controls cortical gain, and supports concentration-invariant representations of odor identity. Thus, although recurrent circuitry in the PCx is typically thought to provide the excitatory substrate for odor learning, memory, and olfactory pattern completion (50, 51), recurrent excitation has a net-inhibitory impact on cortical activity. Strong and global feedback inhibition that sparsens and normalizes output has been identified at the equivalent stage of processing in invertebrate olfactory systems; however, this is implemented by a single, globally connected interneuron (52, 53). The highly recurrent CA3 region of hippocampus exhibits a similar pattern of long-range recurrent collateral connectivity (54). Thus, recurrent excitation that is dominated by rapid, global feedback inhibition may reflect a canonical circuit motif for temporally filtering representations in associative cortex and related structures.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

All experimental protocols were approved by Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The methods for head-fixation, data acquisition, electrode placement, stimulus delivery, and analysis of single-unit and population odor responses are adapted from those described in detail previously (15). A portion of the data reported here (5 of 13 simultaneous OB and PCx recordings) were also described in that previous report. Mice were singly-housed on a normal light-dark cycle. For simultaneous OB/PCx recordings and Cre-dependent TeLC expression experiments, mice were adult (>P60, 20–24 g) offspring of Emxl-cre (+/+) breeding pairs obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (005628). Optogenetic experiments used adult Thy1-ChR2-YFP (+/+), line 18 (Thy1-COP4/EYFP, Jackson Laboratory, 007612) and VGAT-ChR2-YFP (+/−), line 8 (Slc32a1-COP4*H134R/EYFP, Jackson Laboratory, 014548). Adult offspring of Emx1-cre (+/+) mice crossed with Thy1-ChR2-YFP (+/+) mice were used for combined optogenetics and TeLC expression.

Adeno-associated viral vectors

All viruses were obtained from the vector core at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill (UNC Vector Core). AAV5-CBA-DIO-TeLC-GFP, AAV5-CBA-DIO-GFP, AAV5-ef1a-DIO-ChR2-EYFP were used for in vitro slice physiology experiments. For in vivo experiments, AAV5-DIO-TeLC-GFP was expressed either under control of a CBA (6 of 7 mice) or synapsin (1 of 7 mice) promoter. Effects were similar and results were pooled. TeLC expression throughout PCx was achieved using 500 nL injections at three stereotaxic coordinates (AP, ML, DV: +1.8, 2.7, 3.85; +0.5, 3.5, 3.8; −1.5, 3.9, 4.2; DV measured from brain surface). Recordings were made ~14 days post-injection.

Immunohistochemistry

To confirm widespread expression of TeLC in PCx, after recordings, mice were perfused with PBS followed by PFA (4%) and the brains were postfixed overnight. Coronal sections (50 μm) were taken through the A-P extent of PCx and permeabilized with Triton (0.1%). Brains were incubated overnight with a primary GFP antibody (Chicken Anti-GFP, Abcam, ab13970,1:500) and then washed and stained overnight with a secondary antibody (Goat Anti-Chicken Alexa Fluor 488, Abcam, ab150169; 1:500) and counter stained (NeuroTrace 640/660, Invitrogen, N21483; 1:400). Slices were mounted and imaged on an upright Zeiss 780 confocal microscope. Quantitative analyses were performed using ImageJ.

In vitro electrophysiology and analysis

For experiments examining viability and excitability in TeLC-infected neurons (Fig. 4, D to G), viruses were injected as described above. For experiments validating that transmitter release was blocked in TeLC-infected neurons (Fig. 4, A to C), a single injection containing a cocktail of 150 nL AAV-EF1 a-DIO-ChR2-EYFP and either 150 nL AAV-EF1a-DIO-ChR2-GFP or 150 nL AAV-CAG-DIO-GFP-TeLC was injected at a single site in anterior PCx. Fifteen ± 2 days after virus injection, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated. The cortex was quickly removed in ice-cold artificial CSF (aCSF). Parasagittal brain slices (300 μm) were cut using a vibrating microtome (Leica) in a solution containing (in mM): 10 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 0.5 CaCl2,7 MgSO4, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3,10 glucose, and 195 sucrose, equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Slices were incubated at 34°C for 30 min in aCSF containing: 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4,25 mM NaHCO3, 25 mM glucose, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 NaPyruvate. Slices were then maintained at room temperature until they were transferred to a recording chamber on an upright microscope (Olympus) equipped with a 40x objective.

For current clamp recordings, patch electrodes (3–6 megohm) contained: 130 Kmethylsulfonate, 5 mM NaCl, 10 HEPES, 12 phosphocreatine, 3 MgATP, 0.2 NaGTP, 0.1 EGTA, 0.05 AlexaFluor 594 cadaverine. For voltage-clamp experiments, electrodes contained: 130 D-Gluconic acid, 130 CsOH, 5 mM NaCl, 10 HEPES, 12 phosphocreatine, 3 MgATP, 0.2 NaGTP, 10 EGTA, 0.05 AlexaFluor 594 cadaverine. Voltage- and current-clamp responses were recorded with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier, filtered at 2–4 kHz, and digitized at 10 kHz (Digidata 1440). Series resistance was typically ~10 megohm, always <20 megohm, and was compensated at 80%−95%. The bridge was balanced using the automated Multiclamp function in current clamp recordings. Data were collected and analyzed off-line using AxographX and IGOR Pro (Wavemetrics). Junction potentials were not corrected. Recordings targeted pyramidal cells, which were visualized (CoolLED) to ensure that cells had pyramidal cell morphologies.

For current clamp recordings to examine viability and excitability, TeLC- or GFP-infected neurons were targeted using 470 nm light (CoolLED). In current clamp recordings, a series of 1 s. current pulses were stepped in 50 pA increments. To examine synaptic properties, we first verified that fluorescent cells exhibited large photocurrents in both ChR2-YFP/GFP- and ChR2-YFP/GFP-TeLC-injected slices (not shown). We then recorded in voltage-clamp from uninfected cells adjacent to the infection site. Cells were held at either −70 mV or +5 mV to isolate excitatory or inhibitory synaptic currents, respectively. Brief (1 ms) 470 nm pulses were delivered through the objective every 10 s to activate ChR2+ axon terminals. A concentric bipolar electrode in the lateral olfactory tract was used to activate synaptic inputs from OB (Fig. 4, E and F). The bipolar electrode was placed at the layer 2/3 border 226 ± 17 μm from the recorded cell to examine feedback inhibition (Fig. 4G). NBQX, D-APV, and gabazine were acquired from Tocris.

Head-fixation

Mice were habituated to head-fixation and tube restraint for 15–30 min on each of the two days prior to experiments. The head post was held in place by two clamps attached to ThorLabs posts. A hinged 50 ml Falcon tube on top of a heating pad (FHC) supported and restrained the body in the head-fixed apparatus.

Odor stimuli and delivery

Odor stimuli were prepared and delivered as described previously (15). Briefly, stimuli were monomolecular odorants diluted in mineral oil and included the following: hexanal (Aldrich 115606), ethyl butyrate (Aldrich E15701), ethyl acetate [Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), 34858], 2-hexanone [Fluka (Mexico), 02473], isoamyl acetate [Tokyo Chemical Industry (Cambridge, MA), A0033], and ethyl tiglate [Alfa Aesar (Haverhill, MA), A12029]. Odor were delivered using a custom olfactometer controlled by MATLAB scripts. Normally a 1LPM neutral air stream was directed to the mouse’s nose. During a trial, air was directed through one of the odor vials and the odorized air stream directed to exhaust for an equilibration period of 4 s before rapid switching of a final valve triggered on exhalation re-directed odorized air to the nose and neutral air to exhaust. This was reversed after 1 s. Odors were presented every 10 s.

Data acquisition

Electrophysiological signals were acquired with 32-site polytrode acute probes (A1×32-Poly3–5mm-25s-177, Neuronexus) through an A32-OM32 adaptor (Neuronexus) connected to a Cereplex digital headstage (Blackrock Microsystems). A fiber-attached polytrode probe (A1×32-Poly3–5mm-25s-177-OA32LP, Neuronexus) was used for recordings from optogenetically identified GABAergic cells. Unflltered signals were digitized at 30 kHz at the headstage and recorded by a Cerebus multichannel data acquisition system (BlackRock Microsystems). Experimental events and respiration signals were acquired at 2 kHz by analog inputs of the Cerebus system. Respiration was monitored with a microbridge mass airflow sensor (Honeywell AWM3300V) positioned directly opposite the animal’s nose. Negative airflow corresponds to inhalation and negative changes in the voltage of the sensor output.

Electrode and optic fiber placement

The recording probe was positioned in the anterior piriform cortex using a Patchstar Micromanipulator (Scientifica). For piriform cortex recordings, the probe was positioned at 1.32 mm anterior and 3.8 mm lateral from bregma. Recordings were targeted 3.5–4 mm ventral from the brain surface at this position with adjustment according to the local field potential (LFP) and spiking activity monitored online. Electrode sites on the polytrode span 275 μm along the dorsal-ventral axis. The probe was lowered until a band of intense spiking activity covering 30–40% of electrode sites near the correct ventral coordinate was observed, reflecting the densely packed layer II of piriform cortex. For standard recordings, the probe was lowered to concentrate this activity at the center of the DV axis of the probe. For deep or superficial recordings, the probe was targeted such that strong activity was at the most ventral or most dorsal part of the probe respectively. For simultaneous ipsilateral olfactory bulb recordings, a micromanipulator holding the recording probe was set to a 10-degree angle in the coronal plane, targeting the ventrolateral mitral cell layer. The probe was initially positioned above the center of the olfactory bulb (4.85 AP, 0.6 ML) and then lowered along this angle through the dorsal mitral cell and granule layers until encountering a dense band of high-frequency activity signifying the targeted mitral cell layer, typically between 1.5 and 2.5 mm from the bulb surface. For experiments driving OB cells in Thy1-ChR2-YFP mice, an optic fiber was positioned <500 μm above the dorsal surface of the bulb.

Spike sorting and waveform characteristics

Individual units were isolated using Spyking-Circus (https://github.com/spyking-circus) (55). Clusters with >1% of ISIs violating the refractory period (< 2 ms) or appearing otherwise contaminated were manually removed from the dataset. This criterion was relaxed to 2% in Thy1-ChR2-YFP recordings because these were short (<15 min) and had poorer overall sorting quality, and these results do not depend on unit isolation, but rather total population spiking activity. Pairs of units with similar waveforms and coordinated refractory periods in the cross-correlogram were combined into single clusters. Extracellular waveform features were characterized according to standard measures: peak-to-trough time and ratio and peak amplitude asymmetry (56). Unit position with respect to electrode sites was characterized as the average of all electrode site positions weighted by the wave amplitude on each electrode.

Spontaneous activity and respiration-locking

Spontaneous activity was assessed during inter-trial intervals at least 4 s after stimulus offset and 1 s preceding stimulus. The relationship of each unit’s spiking to the ongoing respiratory oscillation was quantified using both phase concentration (κ) (57) and pairwise phase consistency (PPC) (58). Each spike was assigned a phase by interpolation between inhalation (0 degrees) and exhalation (180°). Each spike was then treated as a unit vector and PPC was taken as the average of the dot products of all pairs of spikes.

Individual and average cell-odor responses

We computed smoothed kernel density functions (KDF) with a 10 ms Gaussian kernel (using the psth routine from the Chronux toolbox (59) to visualize trial-averaged firing rates as a function of time from inhalation onset and to define response latencies for each cell-odor pair. Multiunit activity or population responses were constructed by averaging these KDFs across all cells and odors. Peak latency was defined as the maximum of the KDF within a 500-ms response window following inhalation. Response duration was the full-width at half-maximum of this peak.

Identifying VGAT+ interneurons

To assess odor responses in identified interneurons, 1-s light pulses were delivered just above the recording sites using a fiber-attached probe. Twenty pulses were delivered both before and after presentation of the full odor stimulation series. Cells were labeled as laser-responsive using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test comparing firing rates in the 1-s prior to and during laser stimulation.

Sparseness

Lifetime and population sparseness were calculated as described previously (15, 60).

Principal components analysis

Principal components were computed from pseudopopulation response vectors using the Dimensionality Reduction Toolbox (https://lvdmaaten.github.io/drtoolbox). Responses were spike counts over the first 330 ms after inhalation on each trial for each cell. Responses were combined across all cells in TeLC or control conditions to form pseudo-population response vectors. To compute PC distance, 3-dimensional Euclidean distances were computed for each trial pair and the average trial-pair distance was computed for each stimulus. For example, the “same-odor, different concentration” distance for 1% ethyl butyrate is an average of ten 1% trials’ distances from thirty trials of three other concentrations (300 distances). Summary statistics were computed on these average trial-pair distances.

Population decoding analysis

Odor classification accuracy based on population responses was measured using a Euclidean distance classifier with Leave-One-Out cross-validation. Responses to four distinct monomolecular odorants presented at 0.3% v/v and two more odorants presented in a concentration series at 0.03%, 0.1%, 0.3% and 1% v/v were used as the training and testing data. For generalization tasks, one concentration was left out during training and testing and the classifier prediction was recoded as ‘correct’ if the predicted odor was of the same identity as the presented odor. The feature vectors were spike counts in concatenated sets of 20 ms bins over the first 340 ms following inhalation.

Statistics

Statistics were computed in MATLAB. Paired t tests were used when comparing the same animals, cells, or cell-odor pairs across states. Unpaired t tests and two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were used when comparing properties for distinct cell-odor pairs. Sample sizes were large such that t tests were robust to nonnormality. Results were equivalent with nonparametric tests. No formal a priori sample size calculation was performed, but our sample sizes are similar to those used in previous studies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Lee, B. Ryu, and M. Dalgetty for technical assistance; A. West and F. Wang for GFP-TeLC AAVs; and A. Fleischmann, S. Lisberger, T. Margrie, R. Mooney, M. Scanziani, A. Schaefer, M. Tadross, and F. Wang for helpful comments on early versions of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (DC009839 and DC015525) and the Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: Data have been deposited at the CRCNS (https://crcns.org) and can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.6080/K00C4SZB. Materials are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencemag.org/content/361/6407/eaat6904/suppl/DC1 Figs. S1. to S6

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Jiang Y et al. , Molecular profiling of activated olfactory neurons identifies odorant receptors for odors in vivo. Nat. Neurosci 18, 1446–1454 (2015). doi: 10.1038/nn.4104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubin BD, Katz LC, Optical imaging of odorant representations in the mammalian olfactory bulb. Neuron 23, 499–511 (1999). doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80803-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meister M, Bonhoeffer T, Tuning and topography in an odor map on the rat olfactory bulb. J. Neurosci 21, 1351–1360 (2001). doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01351.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bozza T, McGann JP, Mombaerts P, Wachowiak M, In vivo imaging of neuronal activity by targeted expression of a genetically encoded probe in the mouse. Neuron 42, 9–21 (2004). doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00144-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laing DG, Legha PK, Jinks AL, Hutchinson I, Relationship between molecular structure, concentration and odor qualities of oxygenated aliphatic molecules. Chem. Senses 28, 57–69 (2003). doi: 10.1093/chemse/28.1.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krone D, Mannel M, Pauli E, Hummel T, Qualitative and quantitative olfactometric evaluation of different concentrations of ethanol peppermint oil solutions. Phytother. Res 15, 135–138 (2001). doi: 10.1002/ptr.716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homma R, Cohen LB, Kosmidis EK, Youngentob SL, Perceptual stability during dramatic changes in olfactory bulb activation maps and dramatic declines in activation amplitudes. Eur. J. Neurosci 29, 1027–1034 (2009). doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06644.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bathellier B, Buhl DL, Accolla R, Carleton A, Dynamic ensemble odor coding in the mammalian olfactory bulb: Sensory information at different timescales. Neuron 57, 586–598 (2008). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cury KM, Uchida N, Robust odor coding via inhalationcoupled transient activity in the mammalian olfactory bulb. Neuron 68, 570–585 (2010). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shusterman R, Smear MC, Koulakov AA, Rinberg D, Precise olfactory responses tile the sniff cycle. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 1039–1044 (2011). doi: 10.1038/nn.2877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukunaga I, Berning M, Kollo M, Schmaltz A, Schaefer AT, Two distinct channels of olfactory bulb output. Neuron 75, 320–329 (2012). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Illig KR, Haberly LB, Odor-evoked activity is spatially distributed in piriform cortex. J. Comp. Neurol 457, 361–373 (2003). doi: 10.1002/cne.10557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stettler DD, Axel R, Representations of odor in the piriform cortex. Neuron 63, 854–864 (2009). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miura K, Mainen ZF, Uchida N, Odor representations in olfactory cortex: Distributed rate coding and decorrelated population activity. Neuron 74, 1087–1098 (2012). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolding KA, Franks KM, Complementary codes for odor identity and intensity in olfactory cortex. eLife 6, e22630 (2017). doi: 10.7554/eLife.22630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roland B, Deneux T, Franks KM, Bathellier B, Fleischmann A, Odor identity coding by distributed ensembles of neurons in the mouse olfactory cortex. eLife 6, e26337 (2017). doi: 10.7554/eLife.26337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spors H, Grinvald A, Spatio-temporal dynamics of odor representations in the mammalian olfactory bulb. Neuron 34, 301–315 (2002). doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00644-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Margrie TW, Schaefer AT, Theta oscillation coupled spike latencies yield computational vigour in a mammalian sensory system. J. Physiol 546, 363–374 (2003). doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cang J, Isaacson JS, In vivo whole-cell recording of odor-evoked synaptic transmission in the rat olfactory bulb. J. Neurosci. 23, 4108–4116 (2003). doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04108.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Junek S, Kludt E, Wolf F, Schild D, Olfactory coding with patterns of response latencies. Neuron 67, 872–884 (2010). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson CD, Serrano GO, Koulakov AA, Rinberg D, A primacy code for odor identity. Nat. Commun 8, 1477 (2017). doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01432-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arneodo EM et al. , Stimulus dependent diversity and stereotypy in the output of an olfactory functional unit. Nat. Commun 9, 1347 (2018). doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03837-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hopfield JJ, Pattern recognition computation using action potential timing for stimulus representation. Nature 376, 33–36 (1995). doi: 10.1038/376033a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaefer AT, Margrie TW, Psychophysical properties of odor processing can be quantitatively described by relative action potential latency patterns in mitral and tufted cells. Front. Syst. Neurosci 6, 30 (2012). doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2012.00030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stern M, Bolding KA, Abbott LF, Franks KM, A transformation from temporal to ensemble coding in a model of piriform cortex. eLife 7, e34831 (2018). doi: 10.7554/eLife.34831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki N, Bekkers JM, Microcircuits mediating feedforward and feedback synaptic inhibition in the piriform cortex. J. Neurosci 32, 919–931 (2012). doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4112-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luna VM, Schoppa NE, GABAergic circuits control inputspike coupling in the piriform cortex. J. Neurosci 28, 8851–8859 (2008). doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2385-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poo C, Isaacson JS, Odor representations in olfactory cortex: “Sparse” coding, global inhibition, and oscillations. Neuron 62, 850–861 (2009). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stokes CCA, Isaacson JS, From dendrite to soma: Dynamic routing of inhibition by complementary interneuron microcircuits in olfactory cortex. Neuron 67, 452–465 (2010). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson DMG, Illig KR, Behan M, Haberly LB, New features of connectivity in piriform cortex visualized by intracellular injection of pyramidal cells suggest that “primary” olfactory cortex functions like “association” cortex in other sensory systems. J. Neurosci 20, 6974–6982 (2000). doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06974.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franks KM et al. , Recurrent circuitry dynamically shapes the activation of piriform cortex. Neuron 72, 49–56 (2011). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu R, Zhang J, Luo M, Hu J, Response patterns of GABAergic neurons in the anterior piriform cortex of awake mice. Cereb. Cortex 27, 3110–3124 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davison IG, Ehlers MD, Neural circuit mechanisms for pattern detection and feature combination in olfactory cortex. Neuron 70, 82–94 (2011). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poo C, Isaacson JS, A major role for intracortical circuits in the strength and tuning of odor-evoked excitation in olfactory cortex. Neuron 72, 41–48 (2011). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carandini M, Heeger DJ, Normalization as a canonical neural computation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 13, 51–62 (2011). doi: 10.1038/nrn3136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyd AM, Sturgill JF, Poo C, Isaacson JS, Cortical feedback control of olfactory bulb circuits. Neuron 76, 1161–1174 (2012). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Markopoulos F, Rokni D, Gire DH, Murthy VN, Functional properties of cortical feedback projections to the olfactory bulb. Neuron 76, 1175–1188 (2012). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otazu GH, Chae H, Davis MB, Albeanu DF, Cortical Feedback Decorrelates Olfactory Bulb Output in Awake Mice. Neuron 86, 1461–1477 (2015). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cleland TA et al. , Sequential mechanisms underlying concentration invariance in biological olfaction. Front. Neuroeng 4, 21 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu P, Frank T, Friedrich RW, Equalization of odor representations by a network of electrically coupled inhibitory interneurons. Nat. Neurosci 16, 1678–1686 (2013). doi: 10.1038/nn.3528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Banerjee A et al. , An interglomerular circuit gates glomerular output and implements gain control in the mouse olfactory bulb. Neuron 87, 193–207 (2015). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arenkiel BR et al. , In vivo light-induced activation of neural circuitry in transgenic mice expressing channelrhodopsin-2. Neuron 54, 205–218 (2007). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gollisch T, Meister M, Rapid neural coding in the retina with relative spike latencies. Science 319, 1108–1111 (2008). doi: 10.1126/science.1149639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thorpe S, Delorme A, Van Rullen R, Spike-based strategies for rapid processing. Neural Netw. 14, 715–725 (2001). doi: 10.1016/S0893-6080(01)00083-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panzeri S, Petersen RS, Schultz SR, Lebedev M, Diamond ME, The role of spike timing in the coding of stimulus location in rat somatosensory cortex. Neuron 29, 769–777 (2001). doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00251-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johansson RS, Birznieks I, First spikes in ensembles of human tactile afferents code complex spatial fingertip events. Nat. Neurosci. 7,170–177 (2004). doi: 10.1038/nn1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heil P, First-spike latency of auditory neurons revisited. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 14, 461–467 (2004). doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zohar O, Shamir M, A readout mechanism for latency codes. Front. Comput. Neurosci 10, 107 (2016). doi: 10.3389/fncom.2016.00107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen Y, Mechanisms of winner-take-all and group selection in neuronal spiking networks. Front. Comput. Neurosci 11, 20 (2017). doi: 10.3389/fncom.2017.00020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haberly LB, Parallel-distributed processing in olfactory cortex: New insights from morphological and physiological analysis of neuronal circuitry. Chem. Senses 26, 551–576 (2001). doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.5.551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson DA, Sullivan RM, Cortical processing of odor objects. Neuron 72, 506–519 (2011). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Papadopoulou M, Cassenaer S, Nowotny T, Laurent G, Normalization for sparse encoding of odors by a wide-field interneuron. Science 332, 721–725 (2011). doi: 10.1126/science.1201835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin AC, Bygrave AM, de Calignon A, Lee T, Miesenböck G, Sparse, decorrelated odor coding in the mushroom body enhances learned odor discrimination. Nat. Neurosci 17, 559–568 (2014). doi: 10.1038/nn.3660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guzman SJ, Schlögl A, Frotscher M, Jonas P, Synaptic mechanisms of pattern completion in the hippocampal CA3 network. Science 353, 1117–1123 (2016). doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yger P et al. , A spike sorting toolbox for up to thousands of electrodes validated with ground truth recordings in vitro and in vivo. eLife 7, e34518 (2018). doi: 10.7554/eLife.34518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bartho P et al. , Characterization of neocortical principal cells and interneurons by network interactions and extracellular features. J. Neurophysiol 92, 600–608 (2004). doi: 10.1152/jn.01170.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berens P, CircStat: A MATLAB toolbox for circular statistics. J. Stat. Softw 31, 1–21 (2009). doi: 10.18637/jss.v031.i10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vinck M, van Wingerden M, Womelsdorf T, Fries P, Pennartz CMA, The pairwise phase consistency: A bias-free measure of rhythmic neuronal synchronization. Neuroimage 51, 112–122 (2010). doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bokil H, Andrews P, Kulkarni JE, Mehta S, Mitra PP, Chronux: A platform for analyzing neural signals. J. Neurosci. Methods 192, 146–151 (2010). doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vinje WE, Gallant JL, Sparse coding and decorrelation in primary visual cortex during natural vision. Science 287, 1273–1276 (2000). doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.