Abstract

Objective:

Pediatric aerodigestive programs appear to be rapidly proliferating and provide multi-disciplinary, coordinated care to complex, medically-fragile children. Pediatric subspecialists are considered essential to these programs. This study evaluated the state of these programs in 2017 by surveying their size, composition, prevalence, and the number of patients that they serve.

Methods:

The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition Aerodigestive Special Interest Group leadership distributed an 11-question survey to the Pediatric Gastroenterology International Listserv. The mean time of the programs’ existence, number of half-day clinics, number of procedure days, number of patients evaluated and the lead primary specialty were evaluated.

Results:

Thirty-four programs responded. Twenty-five were based in academic centers. 31 programs were located across the United States. The average time of program existence was 5.3 years (SD 4.3 range 1-17 years). 64.7% were started in the past five years. Twelve programs were based in the division of gastroenterology. The average number of gastroenterologists serving aerodigestive programs was 2 (SD 1.1). The mean number of half-day clinic sessions and procedure days were 2.8 (SD 2.9) and 2.6 (SD 2) respectively. New and follow-up visits per year in each program averaged 184 (SD 168, range 10-750).

Conclusion:

Pediatric aerodigestive programs are prevalent, proliferating, and serve a large number of complex patients across North America and the world. This survey demonstrated that programs are predominantly based in academic settings. The number of patients cared for by aerodigestive centers varies widely depending on size and age of program

Keywords: aerodigestive, pediatrics, triple-aim, multi-disciplinary medicine, gastroenterology, otolaryngology, pulmonology

Introduction

Multidisciplinary pediatric aerodigestive programs appear to be part of an increasing movement towards providing coordinated care for complex, medically-fragile children at medical centers throughout North America and the world. While medically complex children only represent 13–19% of all children, they have a disproportionate utilization of health care resources with respiratory morbidity as a major driver of costs1. Coordination of care is important not only to improve a patient’s quality of life but also to improve communication between specialists and to reduce the wait time for appointments and procedures2. Based on this recognition of need, aerodigestive programs have begun as an effort to coordinate the care of patients with affected breathing, swallowing and digestive (i.e. upper gastrointestinal) disorders2, 3.

According to the recently published aerodigestive consensus statement, conditions treated by these programs are diverse and include: structural or physiological airway disease, chronic parenchymal lung disease, lung injury from aspiration or infection, gastroesophageal reflux, eosinophilic esophagitis, esophageal dysmotility or stricture, dysphagia and behavioral feeding problems3. These children require multidisciplinary care to help coordinate their workup, which may include a swallowing evaluation and “triple scope” (bronchoscopy, laryngoscopy and endoscopy), as well as their overall management and treatment courses. Programs tend to include but are not limited to a specialized care-coordinator, otolaryngologists, pulmonologists, gastroenterologists, nutritionists and speech-language pathologists3. Each member of the team actively participates in patient evaluations and “consensus” driven coordinated treatment plans.

As aerodigestive programs proliferate, little is known about the number of centers, their patient volume, the key providers, and the leadership structure. The main objective of this survey was to collect data regarding the current state of pediatric aerodigestive programs across the world. We hypothesized that aerodigestive multidisciplinary programs are highly prevalent and serve a large group of medically complex patients. The study set out to identify the number, type (key provider components), duration (i.e. time in formal existence), size, and numbers of patients served by these programs.

Methods

The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) Aerodigestive Special Interest Group leadership created an 11-question Redcap survey to characterize programs in terms of size, patient volume, clinic-sessions, procedural days, and clinical leadership (Table 1). The survey was submitted multiple times to the PEDS-GI list serve over a 10-week period. The Pediatric GI listserv is an internationally reaching opt-in listserv for pediatric gastroenterologists, composed of over 3000 members. This method was used to reach the general pediatric GI community due to the large volume of members. It was additionally re-submitted to specific healthcare centers known to have an aerodigestive program who did not respond to the initial mailing. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB #18–0935). Results were shown as proportions and means with standard deviation.

Table 1.

Aerodigestive Survey

| 1. What is the name of your hospital, practice or group |

| 2. What kind of program are you? A) academic b) private practice c) hybrid |

| 3. Do you have an aerodigestive program at your hospital or in your practice? |

| 4. How long has your program been in existence? |

| 5. What is the name of your aerodigestive gastroenterology lead? |

| 6. What is the email of your aero gastroenterology lead? |

| 7. What specialty division represents the primary leadership of your aerodigestive program |

| 8. How many gastroenterologists or GI providers do you have working in your aerodigestive program |

| 9. How many aerodigestive clinic ½ days per month does your program have? |

| 10. How any aerodigestive procedure days per month does your program have? |

| 11. How many aerodigestive clinic visits (new patient and follow up) does your program have per year? |

Results

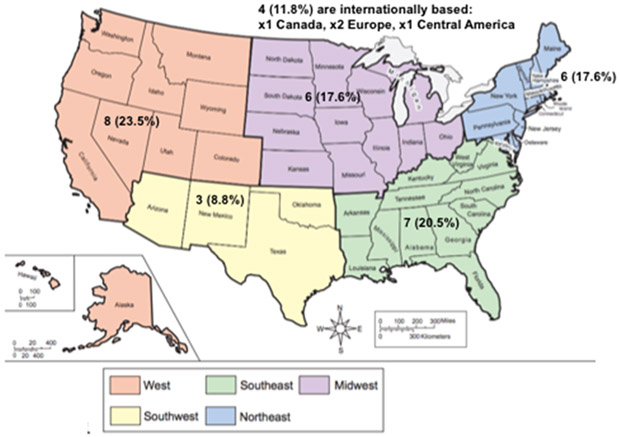

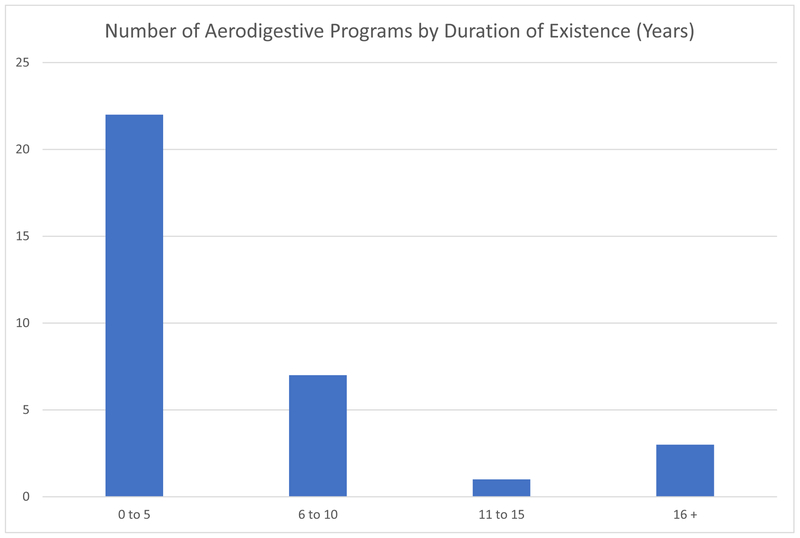

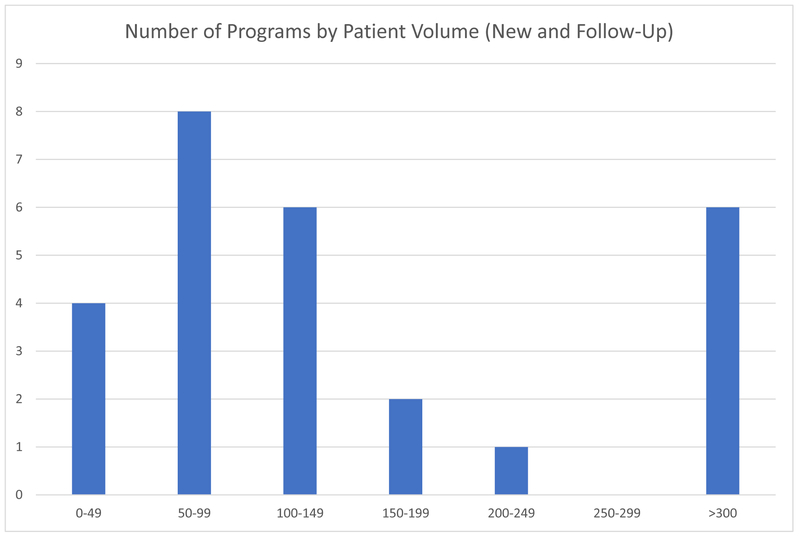

Thirty-four programs responded; 25 were based in academic centers, 1 in a private practice setting, and 8 described themselves as a hybrid of private and academic style. Using the US Census Bureau classification system for assessing standardized geographical location of centers, aerodigestive programs were diffusely located across the United States (US) with 6 (17.6%) located in the northeast, 6 (17.6%) in the Midwest, 7 in the (20.5%) southeast, 8 in the (23.5%) west, and 3 (8.8%) in the southwest. Four programs (11.8%) were internationally based: 1 in Canada, 2 in Europe, and 1 in Central America (Figure 1). Aerodigestive programs had been operating at each location an average of 5.3 years (SD 4.3, range 1–17 years). Programs grouped by duration of existence in five year intervals are shown in Figure 2. 64.7% of all aerodigestive programs have operated for less than five years. For each program, there was a lead primary specialty driving the program’s growth and development; 12 programs identified gastroenterology, 13 identified otolaryngology, and 5 identified pulmonology, 1 identified surgery, and 3 identified other as their primary leadership specialty. The average number of gastroenterologists operating in their associated aerodigestive programs was 2 (SD 1.1 range 1–5). The mean number of half-day clinic sessions and “triple scope” procedural days per month was 2.8 (SD 2.9 range 1–20) and 2.6 (SD 2 range 1–10) respectively. The total number of combined (new and follow up) visits seen per year in each program averaged 184 (SD 168, range 10–750) (Figure 3). The number of clinic visits trended (R2 0.299) with the duration of an aerodigestive program’s existence (Suppl Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Geographic Location of Survey Respondents of Aerodigestive Programs

Figure 2.

Number of Aerodigestive Programs by Duration of Existence (Years)

Figure 3.

Number of Annual Patients Visits (New Patient and Follow Up) (n=27 Mean 184 SD 26)

Discussion

Pediatric aerodigestive programs are becoming increasingly prevalent across North America and the world3. Since the creation of the first multidisciplinary aerodigestive program at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in 1999, dozens of other centers have opened without published descriptions of their leadership and function2. Now with published “consensus” characteristics of an aerodigestive center, this study set out to evaluate this deficiency3. We found that program size, number of procedures performed, and patients evaluated varied greatly across programs. Both the number of clinics and procedure days correlated with length of program existence. For example, program 1, which has been in existence for 17 years saw up to 750 patients per year, while another at 10 years saw 170 patients, and another at 5 years of existence saw 50 patients. We suspect that as these programs continue to grow, so will their patient populations. Further data is needed to monitor the growth of these programs, and more importantly, the outcomes of the patients served by these multidisciplinary models of pediatric patient care.

The survey found that centers are predominantly based in academic settings. It is speculated that medically complex patients who require multiple subspecialties may often seek to centralize their care at children’s hospitals affiliated or part of larger academic institutions and these institutions may have more resources to support the care of these medically complex patients. Berman et al. previously reported on the importance of multi-disciplinary hospital-based primary care with surgical and sub specialty consultations4. Such care was shown to reduce hospitalization stays and increase utilization of surgical services4. While aerodigestive clinics are not meant to replace primary care, they too serve as multidisciplinary centers for complex patients with both medical and surgical needs. Recent literature by Galligan et al. suggests that aerodigestive clinics often serve as medical homes as many of the patients have breathing, feeding, and gastrointestinal needs, too complex for just the primary care pediatrician communicating independently with individual specialists2. In addition to improvements in coordination of care, there may be improvements in overall cost of care for these children5. In addition to decreased overall hospital stays, Casey et al. described an overall reduction in Medicaid costs when hospital-based multidisciplinary teams were utilized6. Casey noted that with use of such a program, inpatient care decreased by $1766 per patient per month while emergency care was lowered by $6; however, the utilization of multidisciplinary care increased the cost of outpatient care. Taken together, this model was shown to decrease the overall cost to Medicaid by $1179 per patient per month. Aerodigestive programs are likely proliferating due to a shift in patient care from inpatient to outpatient, with an overall 20% reduction in a patient’s medical charges due to the interdisciplinary approach7. Additional studies have identified a similar phenomenon. For example, Collaco et al. further broke down the reduction of cost related to procedure time, and thus anesthesia exposure, hospital bills and related hospital travel expenses (gas, parking and facility fees)8. The “triple scope” (bronchoscopy, laryngoscopy and endoscopy), is often utilized in the aerodigestive program as a goal to achieve this. Multiple programs have shown that by combining procedures there is a significant reduction in anesthesia time, operating room time and hospital costs8. Collaco described a reduction in $1985 per avoidable episode of anesthesia, by combining procedures8. Additionally, families take off less time from work and have fewer secondary costs (gas, parking, facility fees)8. Not only does a reduction in anesthesia time reduce cost, but the overall potential morbidity and long term effects of repeated anesthesia exposure on the individual patient. These reasons are likely also driving the expansion of aerodigestive clinics9.

One of the interesting findings of our study was the important role that gastroenterologists play as part of the team. We found that nearly half of the current programs are led by a gastroenterologist as compared to some of the early aerodigestive programs which are housed in the division of otolaryngology (ENT)3. While patients often have, surgical issues requiring intervention, much of the long-term management of the patients is with the medical subspecialties such as gastroenterology and pulmonology. With an increasing recognition of the importance of long term, medical follow up of these patients, the leadership of many programs now has shifted to include medical specialties rather than surgical specialties. As previously described by Piccione et al, each subspecialist on the aerodigestive team plays an important and unique role in the evaluation of these complex patients and this likely represents the opportunity for different divisions to take on leadership roles10. For example, otolaryngology primarily evaluates surgical issues related to the airway including but not limited to: stenosis, obstructive sleep apnea and abnormalities that predispose to aspiration10. Pediatric gastroenterologists’ roles include evaluation of growth and nutrition, barriers to safe feeding, dysmotility, reflux, esophageal strictures, feeding difficulty, constipation, and aspiration10. Finally, pediatric pulmonologists play an active role in the evaluation and management of respiratory comorbidities that may arise with airway reconstruction or chronic lung disease associated to their underlying condition.

While the role of the gastroenterologist early in the evolution of aerodigestive programs was to diagnose and treat gastroesophageal reflux disease, their role has evolved to also diagnose and manage a variety of upper gastrointestinal and digestive disorders including malnutrition, constipation, esophageal atresia, nutritional deficiencies, gastrointestinal motility disorders, esophageal strictures, esophageal dysphagia due to a variety of etiologies (e.g. eosinophilic esophagitis, esophagitis, achalasia). Through advances in clinical and translational research, gastroenterologists have advanced the field of aerodigestive medicine. Recent research has shown that procedures performed by multidisciplinary aerodigestive programs results in less anesthesia exposure for pediatric patients than less experienced providers, a safety advance based on recent concerns about prolonged anesthesia exposure 11, 12,8, 13. Other studies by gastroenterologists have rebutted the commonly held belief surrounding gastroesophageal reflux including that: 1) a red or edematous airway does not denote gastroesophageal reflux disease; 2) salivary pepsin or bronchoalveolar lavage pepsin denotes gastroesophageal reflux disease; 3) reflux by pH or impedance testing events predict pulmonary outcomes, and 4) that the use of mucosal biopsies facilitates the diagnosis of allergic/inflammatory disorders of the esophagus, i.e. eosinophilic esophagitis which is distinct from reflux-associated esophageal disease.11, 12, 14–17 Gastroenterologists continue to play a critical role in the aerodigestive team. They help to refine and decrease unnecessary medical and surgical therapies and broaden the differential diagnosis of medically complex patients beyond the concern for GERD or esophagitis.

With the increase in aerodigestive centers, there has been a national movement to increase the visibility of these centers and disorders. Within the past two years of this study the Pediatric Aerodigestive Consensus Statement was published, the creation of the Aerodigestive Subspecialty Interest Group by the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) occurred, and the Aerodigestive Society was formed 3, 18. The recent increase in publications regarding pediatric aerodigestive centers exemplifies the rising interest of these programs. The duration of program existence and their size also seems to reflect the publication number trend. A PubMed search for “Pediatric Aerodigestive” programs between 1980 and 2018 finds 70 articles, with 51 (72%) of those articles between 2010– 2018, and 39 (55%) of those published within the past 3 years alone (2015–2018)2, 3, 8, 10. We suspect that as these programs proliferate, so too will the research regarding this fragile and medically-complex patient population.

There are several limitations of this study. These limitations include the listserv-based survey and the self-reporting of data. Further, access to pediatric pulmonologist or otolaryngologists who likely are not subscribers to the list-serve may also have limited the catchment of potential programs. With a survey-based methodology there may be both a response bias as well as a lack of response. This survey attempted to remedy this by contacting known programs to obtain their data, however some may have been missed. Additionally, we were unable to capture if any patients were evaluated at more than one Aerodigestive program. Further, the values of such data may not have been accurate. Programs may have entered estimates, precise data, or mixed. This survey did not control for, and was unable to elucidate, the precision of the survey responses. However, the general trend of numbers of programs and patient visits was steady, as smaller programs saw less patients and larger programs saw more and were in existence for larger periods of time. (Suppl Figure 1)

In conclusion, pediatric aerodigestive programs have a significant North American and small global presence in 2017. The programs are proliferating, have expanded publications around aerodigestive care, large in number and reflect a significant number of patient visits for children with complex medical disorders. They are based in various types of medical centers and are led by predominantly gastroenterologists or otolaryngologists in the United States. The growth and impact of these programs to achieve the “triple-aim” of healthcare is likely going to increase over the next decade.

Supplementary Material

Suppl Figure 1. Number of Aerodigestive Clinic Visit by Age of Existence (Years)

What is known:

Recent consensus guidelines have recommended a multidisciplinary approach to children with aerodigestive disorders

The number of aerodigestive centers or programs have been increasing nationally

Pediatric subspecialists including gastroenterologists, are considered essential to these centers

What is new:

Pediatric aerodigestive programs are prevalent, proliferating, and serve many complex patients across North America and the world

This survey demonstrated that gastroenterologists play a critical role as core clinicians and as leaders of these multidisciplinary programs.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Red Cap Supported by NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR002535. RR is funded through the NIH R01 DK097112 and the Boston Children’s Hospital Translational Research Program.

Abbreviations:

- GI

Gastroenterology

- SD

Standard Deviation

- NASPGHAN

North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition

- US

United States

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Joel Friedlander is president, chief medical officer, and co-founder of Triple Endoscopy, Inc. Joel Friedlander is listed as co- inventor on University of Colorado patents pending US 62/184,077, US/ 62/732,272, PCT/US2016/039352, AU201683112, CA 2,990,182, EU 16815420.1, JP 2017–566710, US 15/850,939, US 15/853,521, US15/887,438, US 62/680,798 039352 related to endoscopic methods and technologies. ‘

References:

- 1.Appachi S, Banas A, Feinberg L, et al. Association of Enrollment in an Aerodigestive Clinic With Reduced Hospital Stay for Children With Special Health Care Needs. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;143:1117–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galligan MM, Bamat TW, Hogan AK, et al. The Pediatric Aerodigestive Center as a Tertiary Care-Based Medical Home: A Proposed Model. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2018;48:104–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boesch RP, Balakrishnan K, Acra S, et al. Structure and Functions of Pediatric Aerodigestive Programs: A Consensus Statement. Pediatrics 2018;141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman S, Rannie M, Moore L, et al. Utilization and costs for children who have special health care needs and are enrolled in a hospital-based comprehensive primary care clinic. Pediatrics 2005;115:e637–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boesch RP, Balakrishnan K, Grothe RM, et al. Interdisciplinary aerodigestive care model improves risk, cost, and efficiency. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2018;113:119–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casey PH, Lyle RE, Bird TM, et al. Effect of hospital-based comprehensive care clinic on health costs for Medicaid-insured medically complex children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011;165:392–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skinner ML, Lee SK, Collaco JM, et al. Financial and Health Impacts of Multidisciplinary Aerodigestive Care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;154:1064–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collaco JM, Aherrera AD, Au Yeung KJ, et al. Interdisciplinary pediatric aerodigestive care and reduction in health care costs and burden. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;141:101–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneuer FJ, Bentley JP, Davidson AJ, et al. The impact of general anesthesia on child development and school performance: a population-based study. Paediatr Anaesth 2018;28:528–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piccione J, Boesch RP. The Multidisciplinary Approach to Pediatric Aerodigestive Disorders. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2018;48:66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall CHT, Nguyen N, Furuta GT, et al. Unsedated In-office Transgastrostomy Esophagoscopy to Monitor Therapy in Pediatric Esophageal Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2018;66:33–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedlander JA, DeBoer EM, Soden JS, et al. Unsedated transnasal esophagoscopy for monitoring therapy in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:299–306 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warner DO, Zaccariello MJ, Katusic SK, et al. Neuropsychological and Behavioral Outcomes after Exposure of Young Children to Procedures Requiring General Anesthesia: The Mayo Anesthesia Safety in Kids (MASK) Study. Anesthesiology 2018;129:89–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen R, Mitchell PD, Amirault J, et al. The Edematous and Erythematous Airway Does Not Denote Pathologic Gastroesophageal Reflux. J Pediatr 2017;183:127–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen R, Johnston N, Hart K, et al. The presence of pepsin in the lung and its relationship to pathologic gastro-esophageal reflux. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;24:129–33, e84–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dy F, Amirault J, Mitchell PD, et al. Salivary Pepsin Lacks Sensitivity as a Diagnostic Tool to Evaluate Extraesophageal Reflux Disease. J Pediatr 2016;177:53–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosen R, Hart K, Nurko S. Does reflux monitoring with multichannel intraluminal impedance change clinical decision making? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011;52:404–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Society A. Aerodigestive Society. Volume 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Suppl Figure 1. Number of Aerodigestive Clinic Visit by Age of Existence (Years)