Summary

Aim

Differentiated embryonic chondrocyte gene 1 (DEC1) is involved in the neuronal differentiation and development. The aim of this study is to investigate the role of DEC1 in 1‐methyl‐4‐phenyl‐1,2,3,6‐tetrahydropyridine (MPP +)‐induced PD model.

Methods

The location of DEC1 and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)‐positive neurons were detected by immunofluorescence. 1‐methyl‐4‐phenyl‐1,2,3,6‐tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)‐induced mouse subacute model of PD was established to evaluate the change of DEC1 expression in midbrain. Then, SH‐SY5Y cells were used to investigate the role of DEC1 in MPP +‐induced neurotoxicity.

Results

We showed that the co‐expressed DEC1 and TH neurons took up more than 80% of the expressed TH neurons in the midbrain of mice. DEC1/TH double‐positive neurons decreased by 40.6% in SNpc and 28.8% in VTA of MPTP‐injured mice. Consistently, DEC1, TH and dopamine transporter (DAT) expression decreased in the midbrain of MPTP mice. In SY‐SY5Y cells, MPP + significantly suppressed DEC1 expression and increased the cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3 and Bax/Bcl‐2. DEC1 overexpression relieved, whereas DEC1 knockdown aggravated MPP +‐induced cytotoxicity. Likewise, DEC1 overexpression and knockdown inversely regulated the expression of β‐catenin and PI3Kp110α (PIK3CA), an essential role in Wnt/β‐catenin and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Interestingly, LY294002, an inhibitor of PI3K/Akt signaling, aggravated, whereas LiCl, an activator of Wnt/β‐catenin signaling, abolished the reduction in DEC1 by MPP +. It is established that these two pathways are interconnected by the phosphorylation status of GSK3β. DEC1 overexpression increased but MPP + and DEC1 knockdown decreased GSK3β phosphorylation.

Conclusion

Downregulation of DEC1 contributes to MPP +‐induced neurotoxicity by suppressing PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway.

Keywords: 1‐methyl‐4‐phenyl‐1,2,3,6‐tetrahydropyridine (MPP+); apoptosis; differentiated embryonic chondrocyte gene 1(DEC1); Parkinson disease; PI3K/Akt/GSK3β

1. INTRODUCTION

Parkinson disease (PD), one of the most common neurodegenerative disorders, is pathologically characterized by selective loss of midbrain dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc).1, 2 The genetic and microenvironmental factors may mutually cooperate to promote dopaminergic neuronal death in the etiology of PD.3The microenvironmental factors have been associated with oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, neuroinflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, loss of calcium homeostasis, and neuron apoptosis.4, 5, 6 Recently,the major progress of dopaminergic neuronal death has been made in the genetic and signaling networks that control the generation of midbrain dopaminergic neurons.7, 8, 9 Increasing studies have revealed the crucial role of several transcription factors in the midbrain dopaminergic neuron development. For instance, lots of transcription factors, such as Engrailed‐1/Engrailed‐2, Foxa1/2, Lmx1a/b, Nurr1, Otx2, and Pitx3, are required for the maintenance of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons.10, 11 It is noteworthy that possible links between transcription factors and PD have been studied.12, 13

Human differentiated embryonic chondrocyte gene 1 (DEC1, BHLHE40), also called stimulated with retinoic acid 13 (STRA13) in mouse and enhancer of split and hairy related protein 2 (SHARP2) in rat, is one of the basic helix‐loop‐helix (bHLH) transcription factors.14, 15, 16 It is widely expressed in normal tissues and is associated with cell differentiation, proliferation, biological rhythm, apoptosis, and lipid metabolism.17, 18, 19, 20 Previous studies have shown that DEC1 has anti‐apoptotic through affecting the expression of caspases and survivin.21, 22 Overexpression of DEC1 effectively antagonizes apoptosis and selectively inhibits the activation of procaspase 3, 7, 9 induced by serum starvation.22 Knockdown of endogenous DEC1 abrogates the promoted cell survival by TGF‐β in breast cancer cells.23 In addition, DEC1 is related to neuronal differentiation and neuron maturity in the central nervous system (CNS). For example, overexpression of STRA13 (DEC1) promotes neuronal differentiation,14 and SHARP1 and SHARP2 (DEC1) are expressed in the subregions of CNS and have been associated with synaptic plasticity.15 However, the role of DEC1 in the degenerative diseases such as PD is to be determined.

The neurotoxin 1‐methyl‐4‐phenyl‐1,2,3,6‐tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) crosses the blood‐brain barrier and is converted to its effective form, 1‐methyl‐4‐phenylpyridinium (MPP+).24 MPP+ gets accumulated in dopaminergic cells in SNpc through disturbing mitochondrial respiratory enzymes and causing oxidative stress, which subsequently leads to cell death.25 SH‐SY5Y cell line possesses many features of dopaminergic neurons characterized by the expression of dopaminergic neuronal marker tyrosine hydroxylases (TH) and dopamine transporter (DAT).26, 27

Here, we reported that DEC1 was co‐expressed with TH positive neurons and significantly decreased in SNpc and ventral tegmental area (VAT) in MPTP‐induced PD mice. Next, we explored the role of DEC1 in MPP+‐induced cytotoxicity in SH‐SY5Y cells.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Chemical and reagents

Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) was from Gibco (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). MPP+, MPTP, probenecid, chloral hydrate, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), LiCl and 3‐(4, 5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). LY294002 was purchased from Beyotime (Shanghai, China). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from HyClone (Logan, UT, USA). DAPI Staining Kit was purchased from Bioworld Technology, Inc. (Louis Park, MN, USA). TUNEL assay kit was obtained from JIANGSU KEYGEN BIOTECH CO.LTD (Nanjing, China). ECL Western blotting detection system was from Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd. The following antibodies were used: anti‐p‐ser473‐Akt, anti‐Akt, anti‐PI3Kp110α antibodies (Santa, Cruz, CA, USA), anti‐β‐catenin antibodies (BD, San Diego, CA, USA), anti‐p‐ser9‐GSK3β, anti‐GSK3β, anti‐caspase 3, anti‐cleaved caspase 3, anti‐Bcl‐2, anti‐Bax, anti‐p‐ser256‐FoxO1, anti‐FoxO1, anti‐BAD, anti‐p‐ser136‐BAD, anti‐β‐actin (Bioworld, St. Louis, MN, USA), anti‐GAPDH (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti‐TH (Sigma‐Aldrich), anti‐DAT (Proteintech, Wuhan, China). The antibody against DEC1 was kindly provided by Dr. Bing‐Fang Yan (University of Rhode Island).28 Goat anti‐rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase and BCA Protein Assay Kit were from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA).

2.2. Animals and treatment

Sixteen‐week adult male C57BL/6N mice were purchased from Jiangsu Province's Medical Experimental Animal Center. Mice were kept at 24°C with a 12‐hour/12‐hour light/dark cycle, allowed free access to tap water, and maintained on a diet of Formular‐M07.

Mice were randomly divided into groups of MPTP and saline, with eight for each. For one, MPTP (25 mg/kg) was injected subcutaneously 1 hour before injection of probenecid (250 mg/kg, i.p.), which was done for 5 days. For the other, the same volume of saline was injected, which was done for as long a time. Animals were sacrificed on the seventh day after the last injection. The samples in this study were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research of Nanjing Medical University. The protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of Nanjing Medical University (Permit Number: 14030106).

2.3. Behavior test

In the beam walking test, the mice were placed head upward on the top of a vertical wooden rough‐surfaced pole (50 cm in length and 1 cm in diameter). The total time for mice to turn downward and climb to the ground was recorded, and the cut‐off limit was 120 seconds. The animals were tested three times with a break of 20 minutes between each trial.29

The rotarod apparatus (Ugo Basile) was used to evaluate mouse forelimb and hindlimb motor coordination and balance. The equipment was performed as described in the previous study.30 On the seventh day, after being trained for 3 days, mice were placed in a separate compartment on the rod and tested at speed of 30 rpm. The latency to fall (time on rod) was recorded. The animals were tested three times with a break of 20 minutes between each trial.31

2.4. Immunofluorescence

Mice were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg, i.p.) and then perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Brains were dissected and maintained in 4% PFA overnight. At the end of gradient dehydration, 30‐μm‐thick frozen brain sections (consisting 14‐15 sections) across the SNpc region of brain were obtained through Leica freezing microtome. Brain sections were sequentially incubated with mouse anti‐TH (1:4000) and rabbit anti‐DEC1 (1:500) followed by goat anti‐mouse TRITC (red) (1:1000) and goat anti‐rabbit FITC (green) (1:1000). Sections were washed with PBS, mounted on coverslips, and then analyzed by fluorescent microscope (Olympus, Japan) (Acquisition software: DP2‐BSW).

2.5. Cell culture and treatments

SH‐SY5Y cells obtained from Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) were cultured in DMEM, supplied with 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL; 100 mg/mL) and incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were treated with different concentrations of MPP+ in 1%FBS for 24 or 48 hours. When cells were treated with the combination of LiCl (50 μmol L−1) or LY294002 (10 μmol L−1) with MPP+, the interval was about 30 minutes.

2.6. Cell viability measured by MTT assay

SH‐SY5Y cells were seeded into 96‐well plates at the density of 1×104 cells/well. After 24‐hour or 48‐hour exposure to different concentrations of MPP+, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 10 μL MTT (5 mg/mL in PBS) each well and the cells were incubated at 37°C. After 4 hours, the medium was removed and 100 μL DMSO was added into each well to dissolve the precipitation. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm using an Automated Microplated Reader ELx800 (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA), and the cell survival ratio (cell viability) was expressed as a percentage of the control. Cell morphology was observed by an inverted light microscope.

2.7. TUNEL assay and DAPI staining

To quantify apoptotic cells, SH‐SY5Y cells were seeded in 24‐well plates at the density of 5×104 cells/well and treated with different concentrations of MPP+ for 48 hours. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA at room temperature for 20 minutes. After being washed with PBS three times, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X‐100 for 5 minutes at room temperature. Thereafter, cells were incubated with TUNEL reaction buffer at 37°C for 1 hour. After being washed three times, cells were incubated with labeling with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐conjugated anti‐fluorescein antibody (Fab fragment) for an additional 30 minutes according to the user's manual. The nuclei were stained for 20 minutes by DAPI Staining Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The TUNEL‐positive cells were monitored by fluorescent microscope (Acquisition software: DP2‐BSW). For DAPI staining, cells with condensed nuclei or nuclear condensations were scored as apoptotic cells.32 For TUNEL assay, TUNEL‐positive cells were determined as dead cells. At least 400 cells from three randomly selected fields were counted for each dish.33

2.8. Western blot analysis

Cell lysates or midbrain homogenates were centrifuged at 12 000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. The protein concentrations were determined by a BCA Protein Assay Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Equal amount of protein was separated by 10% SDS‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using a Bio‐Rad miniprotein‐III wet transfer unit (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% non‐fat milk for 2 hours at room temperature. Blots were incubated with individual primary antibodies against DEC1 (1:4000), TH (1:8000), β‐actin (1:4000), DAT (1:2000), p‐ser473‐Akt (1:1000), Akt (1:2000), PI3Kp110α (1:1000), β‐catenin (1:2000), p‐ser9‐GSK3β (1:1000), GSK3β (1:2000), caspase 3 (1:1000), cleaved caspase 3 (1:1000), Bcl‐2 (1:1000), Bax (1:1000), GAPDH (1:4000), p‐ser256‐FoxO1 (1:1000), FoxO1 (1:1000), BAD (1:2000), and p‐ser136‐BAD (1:2000) at 4°C overnight. After being washed with TBST three times, the membrane was incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour. The protein bands were visualized with the ECL Western blotting detection system according to the manufacturer's instructions. The chemiluminescent signal was captured using Image Analysis software (NIH), and the relative protein level is represented as interest protein/GAPDH.

2.9. Modulation of DEC1 expression by overexpression and shRNA

To explore the role of DEC1 in the apoptosis induced by MPP+, we performed overexpression and knockdown experiments to selectively modulate the expression of DEC1. For the overexpression experiment, SH‐SY5Y cells were seeded in 6‐well plates at the density of 1×106 each well. The procedure of transfection was conducted by GeneJet TM (VerII) (SignaGen Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The transfection mixture contained 800 ng of FlagDEC1 construct (kindly provided by Dr.Yan Lab, University of Rhode Island) or FlagCMV2 for 24 hours with a change of regular medium at 6 hours. The transfected cells were used for subsequent corresponding experiments. For the knockdown experiment, cells were transfected with a DEC1‐shRNA construct or the control‐shRNA for 48 hours with a change of fresh medium at 24 hours. The transfected cells were treated with varying concentrations of MPP+ for 24 or 48 hours.

2.10. Statistical analysis

The data are represented as mean±SD. The significance of the difference with different treatments was determined by Student t test, one‐way or two‐way ANOVA, followed by Tukey post hoc test. P<.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

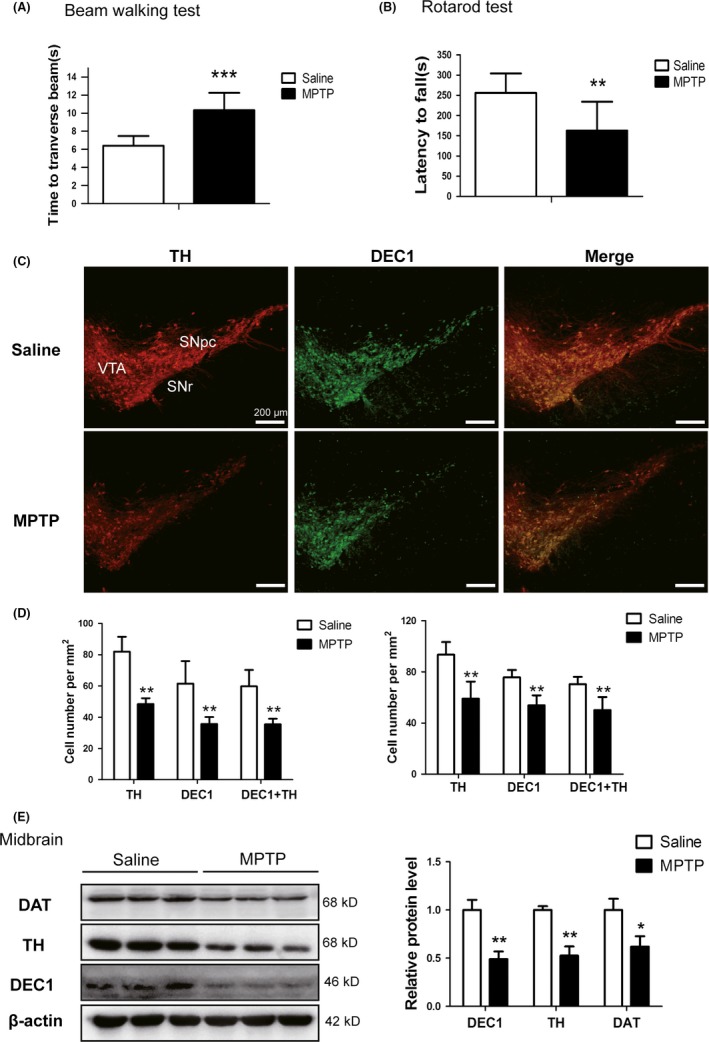

3.1. DEC1 is co‐expressed with TH‐positive neurons and downregulated in SNpc and VTA of MPTP‐induced PD mice

As shown in Fig.S1, DEC1 was co‐expressed with the TH‐positive neurons in SNpc and VTA (Fig.S1A). The co‐expressed DEC1 and TH neurons took up more than 80% of the expressed TH neurons in the midbrain of mice (Fig.S1B). Then, the MPTP‐induced mouse subacute model of PD was established and then tested with behavioral testing. As shown in Figure 1, motor coordination and locomotion ability were evaluated on the 7th day after the final injection of MPTP by measuring the walking time to traverse the beam and the time on the rod. In the beam walking test, the walking time to traverse the beam was longer in MPTP mice than that in saline mice (Figure 1A). The latency on the rotarod rod decreased by 36.5% in MPTP group compared to that in saline group (Figure 1B). MPTP administration decreased TH positive cells by 41% in SNpc (Figure 1C and D left). These results indicated that the PD mouse model was established successfully. In addition, DEC1‐positive neurons decreased by 42% in SNpc (Figure 1C and D left) and 29% in VAT (Figure 1C and D right) of MPTP‐induced PD model mice compared to those in saline group (Figure 1C and D). DEC1/TH double‐positive neurons decreased by 40.6% in SNpc (Figure 1C and D left) and 28.8% in VAT (Figure 1C and D right) of MPTP‐induced PD model mice compared to those in saline group (Figure 1C and D). Consistently, Western blot results showed that MPTP injection significantly decreased DEC1, TH, and DAT expression by 50.9%, 47.3%, and 37.9%, respectively (Figure 1E), in the midbrain. These results indicate that DEC1 is co‐expressed with TH‐positive neurons and downregulated in the midbrain of MPTP‐induced PD mice.

Figure 1.

Downregulation of DEC1 expression in MPTP‐induced mouse PD model. (A) Time (seconds) for traversing the beam. (B) The latency (seconds) before falling (time on the rod). (C) Dual staining with TH (red) and DEC1 (green) in SNpc and VTA by immunofluorescence. (D) The number of TH + cells, DEC1+ cells, and DEC1+/TH + cells per mm2 in SNpc (left) and VTA (right) of mice. (E) The expression of DEC1, TH, and DAT in the midbrain of mice. Mice were randomly divided into groups of MPTP and saline, with eight for each. For one, MPTP (25 mg/kg) was injected subcutaneously 1 hour before injection of probenecid (250 mg/kg, i.p.), which was done for 5 days. For the other, the same volume of saline was injected, which was done for as long a time. On the seventh day after the last injection, behavior tests were performed and then mice were sacrificed. The data are expressed as mean±SD. *P<.05, **P<.01, ***P<.001 vs. saline‐treated group (n=8 in each group)

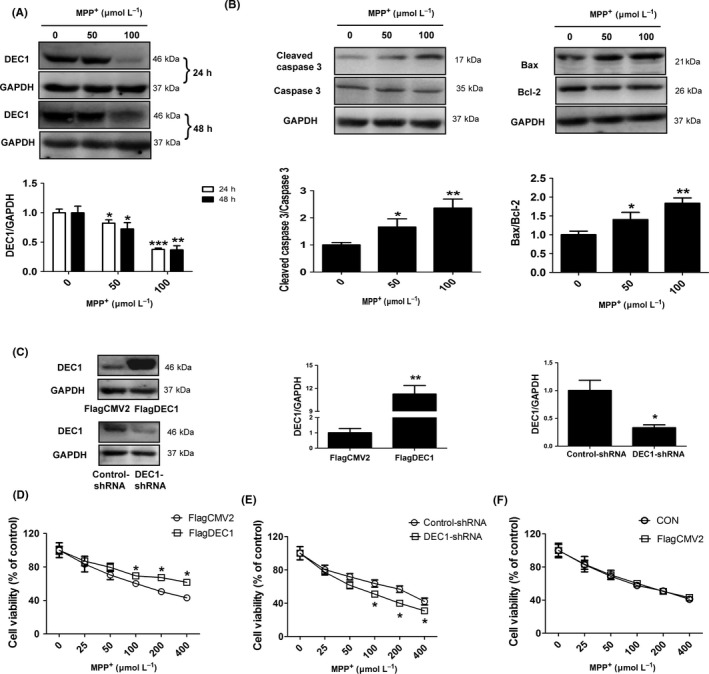

3.2. MPP+ downregulates DEC1 expression and induces the apoptosis in SH‐SY5Y cells

As DEC1 is co‐expressed with TH‐positive neurons and decreased in MPTP‐induced PD model mice, we used SH‐SY5Y cells, which expressed dopaminergic neuronal marker enzyme TH and DAT,26, 27 to explore the mechanism of DEC1 in neurotoxicity induced by MPP+. As shown in Figure 2A, MPP+ significantly decreased the expression of DEC1 by 17.7% (24 hours), and 27.4% (48 hours) at 50 μmol L−1, and by 62.2% (24 hours) and 63.0% (48 hours) at 100 μmol L−1. Meanwhile, MTT, morphological assay and DAPI staining indicated that MPP+ induced cell death in a time‐ and dose‐dependent manner (Fig.S2).

Figure 2.

MPP + downregulates DEC1 expression and induces the apoptosis in SH‐SY5Y cells (A, B) The expression of DEC1 and the apoptosis‐related proteins. Cells were treated with 50 and 100 μmol L−1 MPP + for 24 or 48 hours. Then, cell lysates were analyzed for the expression of DEC1, the cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3, and Bax/Bcl‐2 by Western blot. (C‐F) DEC1 overexpression and knockdown affect the toxicity induced by MPP + in a reverse way. Cells were transfected with FlagDEC1 (800 ng), DEC1‐shRNA (800 ng), or corresponding vector (FlagCMV2, control‐shRNA) for 6 or 24 hours, respectively. The transfected cells were reseeded into 96‐well plates and subsequently treated with various concentrations of MPP + (0, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 400 μmol L−1, each treatment was performed in eight wells) for 48 hours. The cell viability was determined by MTT. All the experiments were repeated at least three times, and the data are expressed as mean±SD. *P<.05, **P<.01, ***P<.001 vs. control (0 concentration)

Caspase 3 is one of the critical executioners of apoptosis, which is expressed as inactive precursor or procaspase.34 It is activated by cleavage event at Asp175/Ser176 to generate the cleaved caspase 3.34, 35 Then, we examined the apoptosis‐related proteins in MPP+‐induced apoptosis. After cells were treated with MPP+ (50 and 100 μmol L−1) for 48 hours, the cleaved caspase 3, caspase 3, Bcl‐2, and Bax were determined by Western blot. In result, the cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3 in MPP+‐treatment cells significantly increased by 1.66 (50 μmol L−1)‐ and 2.36‐fold (100 μmol L−1) more than those in control cells (0 concentration) (Figure 2B, left). The Bax/Bcl‐2 in MPP+‐treated cells, which is crucial for mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, also significantly increased by 1.4 (50 μmol L−1)‐ and 1.84‐fold (100 μmol L−1) more than that in control cells (0 concentration) (Figure 2B, right). These data suggest that MPP+ represses DEC1 expression and induces apoptosis in SH‐SY5Y cells, which is consistent with in vivo.

3.3. DEC1 alleviates MPP+‐induced toxicity mainly through decreasing the caspase 3 activity

To investigate the role of DEC1 in MPP+‐induced apoptosis, we conducted overexpression and knockdown experiments to selectively modulate the expression of DEC1. Then, the cell viability, TUNEL assay, and apoptosis‐related proteins were determined. As shown in Figure 2, MTT and TUNEL assay showed that DEC1 overexpression could significantly limit the cell death induced by MPP+ from 100 to 400 μmol L−1 (Figure 2D) and the apoptosis (the number of TUNEL‐positive cells/the number of total cells) induced by MPP+ of 100 μmol L−1 (Fig.S3A), whereas DEC1 knockdown significantly aggravated the cell death induced by MPP+ from 100 to 400 μmol L−1 (Figure 2E) and the apoptosis (the number of TUNEL‐positive cells/the number of total cells) induced by MPP+ of 100 μmol L−1 (Fig.S3B). It should be noted that DEC1 transfection efficiency was relatively high (~50%) and the efficiency of DEC1 knockdown was more than 60% (Figure 2C). Actually, the cell viability of the transfected cells with FlagCMV2 was almost similar to that of the non‐transfected cells (normal cells) (Figure 2F).

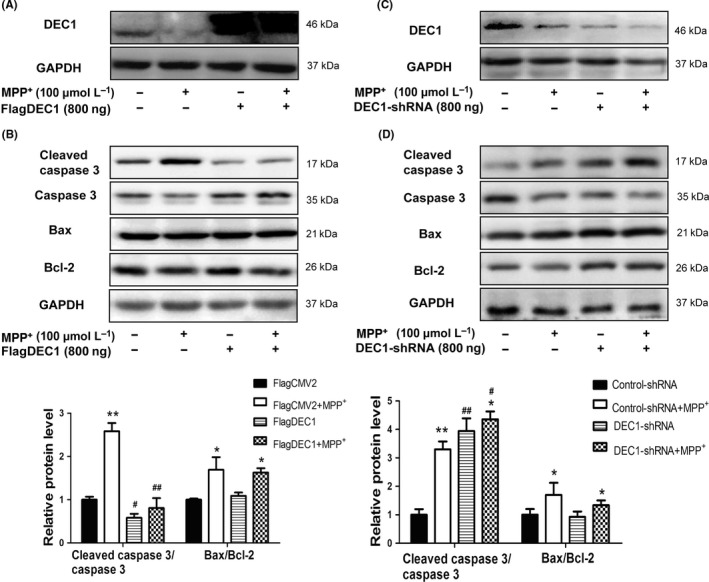

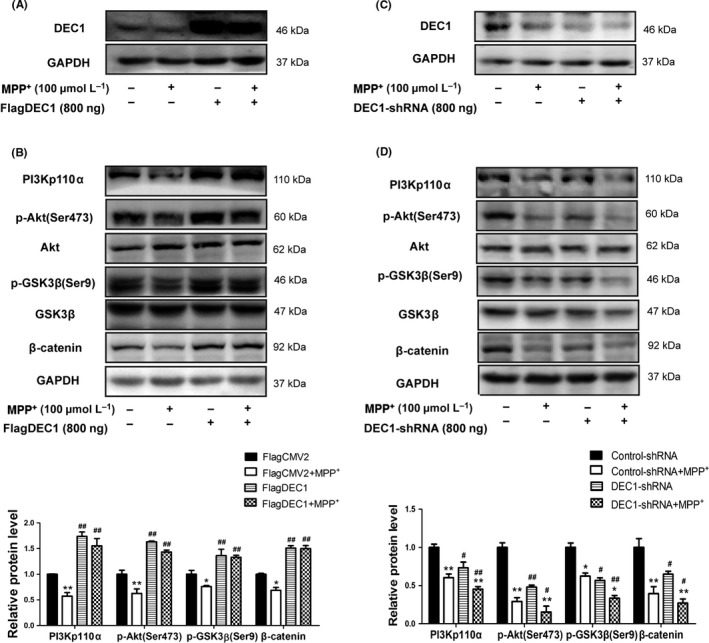

To explore the underlying mechanisms of the protective effects of DEC1 against MPP+‐induced apoptosis, the apoptosis‐related proteins were determined. As shown in Figure 3, DEC1 overexpression alone could significantly decrease the cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3 by 0.42‐fold (Figure 3B), whereas DEC1 knockdown increased the cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3 by 3.9‐fold (Figure 3D). Furthermore, DEC1 overexpression almost abolished, whereas DEC1 knockdown enhanced the increased cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3 induced by MPP+ (Figure 3B and D). However, neither DEC1 overexpression nor DEC1 knockdown affected the increase in the Bax/Bcl‐2 induced by MPP+ (Figure 3B and D). These data imply that DEC1 alleviates MPP+‐induced toxicity mainly through decreasing the caspase 3 activity.

Figure 3.

DEC1 overexpression rescues, whereas DEC1 knockdown enhances the increase in the cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3 induced by MPP + in SH‐SY5Y cells. (A,C) The efficiency of transfection. (B,D) The expression of the apoptosis‐related proteins. Cells were transfected with FlagDEC1 (800 ng), DEC1‐shRNA (800 ng), or equal amount of corresponding vector (FlagCMV2, control‐shRNA) for 6 or 24 hours, respectively. The transfected cells were treated with 100 μmol L−1 MPP + or PBS for 48 hours. Cell lysates were detected for DEC1, the cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3, and Bax/Bcl‐2. All the experiments were repeated at least three times, and the data are expressed as mean±SD. *P<.05, **P<.01 vs. control (PBS), #P<.05, ##P<.01vs. FlagCMV2 or control‐shRNA

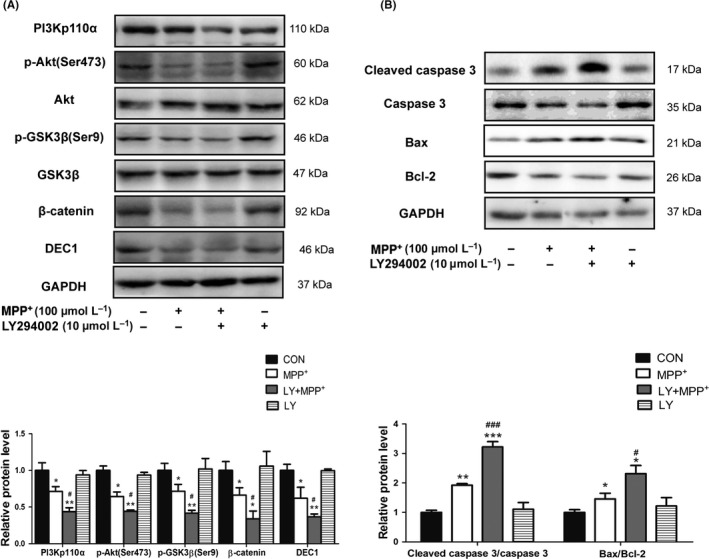

3.4. MPP+ downregulates DEC1 expression and suppresses the PI3K/Akt/GSK3β/β‐catenin signaling pathway

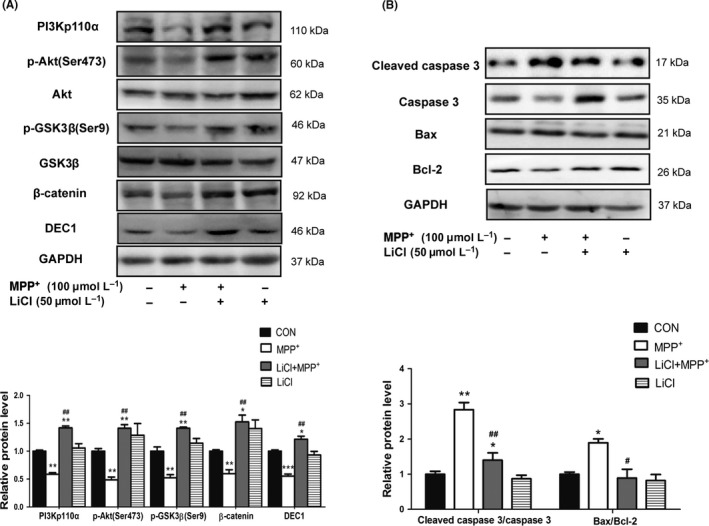

PI3K/Akt pathway is highly conserved to modulate multiple signaling cascades. It plays an essential role in neural survival.36 The neurotoxicity of MPP+/MPTP is associated with inactivation of Akt.37, 38 To explore whether MPP+ affected PI3K/Akt and Wnt/β‐catenin pathways, SH‐SY5Y cells were treated with MPP+ (50 and 100 μmol L−1) for 24 hours. Then, DEC1, PI3Kp110α, and the protein levels in the cascade were determined by Western blot. As shown in Fig.S4), MPP+ reduced DEC1 as well as PI3Kp110α (also known as PI3KCA, one of the three subunit proteins of PI3K) (S4A), an upstream regulator of the Akt/GSK3β/β‐catenin signaling cascade. Likewise, MPP+ reduced PI3Kp110α's downstream targets, the phosphorylation of Akt, GSK‐3β, and β‐catenin (Fig.S4B, C and D). To further confirm an involvement of this cascade in MPP+‐mediated neurotoxicity, LY294002, an inhibitor of PI3K/Akt pathway,39 and LiCl, an inhibitor of GSK‐3β or an activator of Wnt/β‐catenin signaling,40 were used. LiCl was reported to be able to inhibit GSK‐3β activity by activating PI3K/Akt pathway.41, 42 As shown in Figure 4, LY294002 enhanced the decrease in PI3Kp110α, and its downstream targets (p‐Akt/Akt, p‐GSK‐3β/GSK‐3β, β‐catenin) induced by MPP+ (Figure 4A), and promoted the increase in cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3 and Bax/Bcl‐2 induced by MPP+(Figure 4B). In contrast to LY294002, LiCl could reverse the decrease in PI3Kp110α, and its downstream targets (p‐Akt/Akt, p‐GSK‐3β/GSK‐3β and β‐catenin) induced by MPP+ (Figure 5A), and abolish the increase in the cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3 and Bax/Bcl‐2 induced by MPP+ (Figure 5B). Interestingly, LY294002 enhanced, whereas LiCl reversed the decreased DEC1 expression induced by MPP+(Figures 4A and 5A). The findings imply that there are some links between DEC1 and Akt/GSK3β/β‐catenin signaling cascade.

Figure 4.

LY294002 aggravates the decreased DEC1, PI3Kp110α, and its downstream targets and the increased apoptosis‐related proteins induced by MPP +. SH‐SY5Y cells were treated with LY294002 (10 μmol L−1) 30 minutes prior to the addition of MPP + (100 μmol L−1) for 24 or 48 hours. Cell lysates were analyzed for the levels of DEC1, PI3Kp110α, and its downstream targets (A), the cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3, and Bax/Bcl‐2 (B). All the experiments were repeated at least three times, and the data are expressed as mean±SD. *P<.05, **P<.01, ***P<.001 vs. control (PBS), #P<.05, ###P<.001 vs. MPP + treatment

Figure 5.

LiCl ameliorates the decreased DEC1, PI3Kp110α, and its downstream targets and the increased apoptosis‐related proteins induced by MPP +. SH‐SY5Y cells were treated with LiCl (50 μmol L−1) 30 minutes prior to the addition of MPP + (100 μmol L−1) for 24 or 48 hours. Cell lysates were analyzed for the expression of DEC1, PI3Kp110α, and its downstream targets (A), the cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3, and Bax/Bcl‐2 (B). All the experiments were repeated at least three times, and the data are expressed as mean±SD. *P<.05, **P<.01, ***P<.001 vs. control (PBS), #P<.05, ##P<.01 vs. MPP + treatment

3.5. Downregulation of DEC1 contributes to MPP+‐induced toxicity by suppressing PI3K/Akt/GSK3β/β‐catenin signaling pathway

We next tested whether DEC1 was involved in the regulation of Akt/GSK3β/β‐catenin signaling cascade. SH‐SY5Y cells were transfected with FlagDEC1, DEC1‐shRNA or corresponding vector (FlagCMV2 or control‐shRNA). The transfected cells were treated with MPP+ or PBS for 24 hours, and the expression of PI3Kp110α and its downstream targets were determined. As shown in Figure 6, DEC1 overexpression alone significantly increased PI3Kp110α by 1.7‐fold (Figure 6A and B, 1st and 3rd lanes). In contrast, DEC1 knockdown alone decreased PI3Kp110α expression by 0.27‐fold (Figure 6C and D, 1st and 3rd lanes). Importantly, the opposing regulated expression of DEC1 inversely altered the phosphorylation status of Akt and GSK3β, two downstream targets of PI3Kp110α. DEC1 overexpression increased, whereas DEC1 knockdown decreased the phosphorylation of both Akt and GSK3β (Figure 6A, B, C and D, 1st and 3rd lanes).

Figure 6.

DEC1 overexpression alleviates, whereas DEC1 knockdown enhances the decrease in PI3Kp110α, and its downstream targets induced by MPP +. (A, C) The efficiency of transfection. (B, D) The expression of PI3Kp110α, and its downstream targets. SH‐SY5Y cells were transfected with FlagDEC1 (800 ng), DEC1‐shRNA (800 ng), or equal amount of corresponding vector (FlagCMV2, control‐shRNA) for 6 or 24 hours, respectively. The transfected cells were treated with MPP + (100 μmol L−1) or PBS for another 24 hours. Cell lysates were analyzed for PI3Kp110α, and its downstream targets. All the experiments were repeated at least three times, and the data are expressed as mean±SD. *P<.05,**P<.01 vs. control (PBS), #P<.05, ##P<.01 vs. FlagCMV2 or control‐shRNA

Next, we explored whether DEC1 exerted its neural protective effect on MPP+‐induced toxicity via PI3K/Akt/GSK3β/β‐catenin signaling. As shown in Figure 6, DEC1 overexpression significantly alleviated the decrease in PI3Kp110α, and its downstream targets induced by MPP+ (Figure 6B), whereas DEC1 knockdown aggravated the decreased PI3Kp110α and its downstream targets induced by MPP+ (Figure 6D). However, neither DEC1 overexpression nor DEC1 knockdown affected the other downstream targets of Akt, such as the p‐BAD/BAD and p‐FoxO1/FoxO1 (Fig.S5). These results indicate that DEC1 plays a critical role in neuronal survival through collaboration with an integral cascade of the PIK3CA/Akt/GSK3β/β‐catenin signaling pathway. The data also imply that downregulation of DEC1 contributes to the MPP+‐induced toxicity by suppressing the PI3K/Akt/GSK3β/β‐catenin signaling pathway.

4. DISCUSSION

Parkinson disease is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder and pathologically characterized by selective loss of dopaminergic neurons in SNpc of the midbrain. The underlying precise mechanisms remain unclear, but the transcriptional factors are recognized to be important contributing factors in the neuron metabolism and maintenance of normal intracellular homeostasis.43, 44, 45 The bHLH proteins, a superfamily of transcription factors, play an important role in the development and regeneration of the nervous system.46 Many of bHLH proteins have been implicated in the differentiation and maintenance of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons.47, 48 However, the role of DEC1, as one of bHLH transcriptional factors in mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons, is to be determined.

In present study, we use the MPTP‐induced mouse PD model as well as MPP+‐ injured cells and demonstrate that MPP+ reduces DEC1 expression and suppresses PI3K/Akt/GSK3β/β‐catenin signaling pathway, which leads to the increased caspase 3 activity and causes the cell death.

First of all, we have shown that DEC1 is co‐expressed with TH‐positive neurons in mouse midbrain (Fig.S1). Furthermore, the co‐expressed DEC1 and TH neurons significantly decrease in the established subacute MPTP‐induced mouse model of PD with motor impairment. Western blot results show that the expression of DEC1, TH, and DAT decreases in the midbrain of MPTP‐induced PD mice. The reason for selecting the subacute mouse model of PD is that it yields a more progressive neurodegeneration with apoptotic cell death than acute mice model.49 Based on the fact that DEC1 is an anti‐apoptotic factor,23, 24, 33 the reduction in DCE1 plays a determinant role in MPP+‐induced neurotoxicity. We have several lines of evidence to support this notion. MPP+ regulates the expression of DEC1 and that of the cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3 and Bax/Bcl‐2 in a differential way, with DEC1 being suppressed and the others being induced (Figure 2A and B). In addition, the overexpression of DEC1 limits but the knockdown enhances the cell death induced by MPP+ (Figure 2D and E). Moreover, the overexpression of DEC1 ameliorates, whereas the knockdown of DEC1 aggravates the increased cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3 induced by MPP+ (Figure 3A‐D). It should be noted that overexpression and knockdown of DEC1 alone (without MPP+) regulate the cleaved caspase 3/caspase 3 (Figure 3B and D) in a reverse way. While neither overexpression nor knockdown of DEC1 has changed the pattern of Bax/Bcl‐2 induced by MPP+ (Figure 3B and D). These results imply that the reduction in DCE1 causes the toxicity induced by MPP+ mainly through increasing the caspase 3 activity.

The molecular mechanisms whereby DEC1 functions as a neuroprotective transcription factor remain to be determined, particularly in relation to the neurotoxicity of MPP+. PI3K/Akt signaling cascade is considered to be able to promote cell survival and prevent the apoptosis.50 Activation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway may provide neuroprotection in PD.51 For instance, Akt/GSK3β is important in the action of dopamine receptors and homeostatic regulation of dopamine transporters.52, 53 GSK3β is a critical mediator of MPTP/MPP+‐induced neurotoxicity.54, 55 It is assumed that DEC1 exerts the neuroprotective action by interplaying with several signaling pathways, particularly the Wnt/β‐catenin and the PI3K/Akt signaling cascades. While MPP+ significantly decreases DEC1, the reduction is abolished by LiCl, a positive regulator of the Wnt/β‐catenin signaling pathway (Figure 5A). On the other hand, DEC1 overexpression increases and DEC1 knockdown decreases β‐catenin (Figure 6B and D). DEC1 overexpression abolishes and DEC1 knockdown enhances the decreased β‐catenin induced by MPP+ (Figure 6A‐D). Likewise, the downregulation of DEC1 by MPP+ is aggravated by LY294002, an inhibitor of the PI3K/Akt signaling (Figure 4A). DEC1 overexpression and knockdown affect, in a reverse way, the expression of PI3Kp110α and its downstream targets, the phosphorylation Akt and GSK‐3β (Figure 6A‐D). DEC1 overexpression ameliorates and DEC1 knockdown aggravates the decreased PI3Kp110α and its downstream targets induced by MPP+ (Figure 6A‐D). Taken together, these findings suggest that 1) DEC1 reciprocally interacts with the Wnt/β‐catenin and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways, which leads to neuroprotection, 2) downregulation of DEC1 contributes to the neurotoxicity induced by MPP+ by suppressing PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway, which leads to cell death.

DEC1 is a transcription factor acting on a specific sequence, and previous studies have shown that DEC1 acted on E‐box or Sp1 element.21, 56, 57 The interaction with E‐box leads to transcriptional repression, whereas the interaction with Sp1 leads to transactivation. It is therefore assumed that the observed upregulation of PI3Kp110α and its downstream targets by DEC1, p‐Akt, p‐GSK‐3β, and β‐catenin are likely to be achieved through a DEC1‐Sp1 complex. Actually, PI3K/Akt signaling and β‐catenin have reportedly interacted with Sp1.58, 59, 60 It is probably that DEC1, Sp1, and PI3K/Akt or β‐catenin form a functional complex. It remains to be determined whether DEC1 is bound to the specific sequence in promoters of PI3Kp110α and its downstream targets.

In summary, we have provided several lines of evidence to support the major role of DEC1 in MPP+‐induced neurotoxicity. Our study implies that DEC1 might be a novel therapeutic target for PD.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to this work.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Bing‐Fang Yan of university of Rhode Island for kindly providing the DEC1 construct and antibody, and Professor Xiao‐Ping Li of Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics for revising the language of the whole manuscript. The authors also thank Dr. Fan Yi for good suggestions. This study was supported by the Major Project of Jiangsu Provincial Department of Education, China (No. 13KJA310003), the Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81573503,81373443, 81673513).

Zhu Z, Wang Y‐W, Ge D‐H, et al. Downregulation of DEC1 contributes to the neurotoxicity induced by MPP+ by suppressing PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2017;23:736‐747. 10.1111/cns.12717

REFERENCE

- 1. Jiang H, Li LJ, Wang J, Xie JX. Ghrelin antagonizes MPTP‐induced neurotoxicity to the dopaminergic neurons in mouse substantia nigra. Exp Neurol. 2008;212:532‐537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee A, Gilbert RM. Epidemiology of Parkinson disease. Neurol Clin. 2016;34:955‐965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ritz BR, Paul KC, Bronstein JM. Of pesticides and men: a California story of genes and environment in Parkinson's disease. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2016;3:40‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blandini F. Neural and immune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:189‐201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rocha NP, de Miranda AS, Teixeira AL. Insights into neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease: from biomarkers to anti‐inflammatory based therapies. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:628192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sanders LH, Greenamyre JT. Oxidative damage to macromolecules in human Parkinson disease and the rotenone model. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;62:111‐120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blaess S, Ang SL. Genetic control of midbrain dopaminergic neuron development. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2015;4:113‐134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prakash N, Wurst W. Genetic networks controlling the development of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. J Physiol. 2006;575(Pt 2):403‐410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smidt MP, Burbach JP. How to make a mesodiencephalic dopaminergic neuron. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:21‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alavian KN, Jeddi S, Naghipour SI, Nabili P, Licznerski P, Tierney TS. The lifelong maintenance of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons by Nurr1 and engrailed. J Biomed Sci. 2014;21:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fuchs J, Stettler O, Alvarez‐Fischer D, Prochiantz A, Moya KL, Joshi RL. Engrailed signaling in axon guidance and neuron survival. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35:1837‐1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bergman O, Hakansson A, Westberg L, et al. PITX3 polymorphism is associated with early onset Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:114‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rissling I, Strauch K, Hoft C, Oertel WH, Moller JC. Haplotype analysis of the engrailed‐2 gene in young‐onset Parkinson's disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2009;6:102‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boudjelal M, Taneja R, Matsubara S, Bouillet P, Dolle P, Chambon P. Overexpression of Stra13, a novel retinoic acid‐inducible gene of the basic helix‐loop‐helix family, inhibits mesodermal and promotes neuronal differentiation of P19 cells. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2052‐2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rossner MJ, Dorr J, Gass P, Schwab MH, Nave KA. SHARPs: mammalian enhancer‐of‐split‐ and hairy‐related proteins coupled to neuronal stimulation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;10:460‐475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shen M, Kawamoto T, Yan W, et al. Molecular characterization of the novel basic helix‐loop‐helix protein DEC1 expressed in differentiated human embryo chondrocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236:294‐298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Iizuka K, Horikawa Y. Regulation of lipogenesis via BHLHB2/DEC1 and ChREBP feedback looping. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;374:95‐100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lei J, Hasegawa H, Matsumoto T, Yasukawa M. Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor alpha and gamma agonists together with TGF‐beta convert human CD4+CD25‐ T cells into functional Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:7186‐7198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nakashima A, Kawamoto T, Honda KK, et al. DEC1 modulates the circadian phase of clock gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4080‐4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Qian Y, Jung YS, Chen X. Differentiated embryo‐chondrocyte expressed gene 1 regulates p53‐dependent cell survival cell death through macrophage inhibitory cytokine‐1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11300‐11305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li Y, Xie M, Yang J, et al. The expression of antiapoptotic protein survivin is transcriptionally upregulated by DEC1 primarily through multiple sp1 binding sites in the proximal promoter. Oncogene. 2006;25:3296‐3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li Y, Zhang H, Xie M, et al. Abundant expression of Dec1/stra13/sharp2 in colon carcinoma: its antagonizing role in serum deprivation‐induced apoptosis and selective inhibition of procaspase activation. Biochem J. 2002;367(Pt 2):413‐422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ehata S, Hanyu A, Hayashi M, et al. Transforming growth factor‐beta promotes survival of mammary carcinoma cells through induction of antiapoptotic transcription factor DEC1. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9694‐9703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Perfeito R, Cunha‐Oliveira T, Rego AC. Reprint of: revisiting oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease‐resemblance to the effect of amphetamine drugs of abuse. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;62:186‐201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blum D, Torch S, Lambeng N, et al. Molecular pathways involved in the neurotoxicity of 6‐OHDA, dopamine and MPTP: contribution to the apoptotic theory in Parkinson's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:135‐172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nicotra A, Parvez S. Apoptotic molecules and MPTP‐induced cell death. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2002;24:599‐605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xie HR, Hu LS, Li GY. SH‐SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line: in vitro cell model of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson's disease. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123:1086‐1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jinhua H, Zhao M, Wei S, et al. Down regulation of differentiated embryo‐chondrocyte expressed gene 1 is related to the decrease of osteogenic capacity. Curr Drug Targets. 2014;15:432‐441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sedelis M, Hofele K, Auburger GW, Morgan S, Huston JP, Schwarting RK. MPTP susceptibility in the mouse: behavioral, neurochemical, and histological analysis of gender and strain differences. Behav Genet. 2000;30:171‐182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chung YC, Kim SR, Jin BK. Paroxetine prevents loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons by inhibiting brain inflammation and oxidative stress in an experimental model of Parkinson's disease. J Immunol. 2010;185:1230‐1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carter RJ, Morton J, Dunnett SB. Motor coordination and balance in rodents. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2001;15:8.12:8.12.1‐8.12.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Peng Y, Liu W, Xiong J, et al. Down regulation of differentiated embryonic chondrocytes 1 (DEC1) is involved in 8‐methoxypsoralen‐induced apoptosis in HepG2 cells. Toxicology. 2012;301:58‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lebon C, Rodriguez GV, Zaoui IE, Jaadane I, Behar‐Cohen F, Torriglia A. On the use of an appropriate TdT‐mediated dUTP‐biotin nick end labeling assay to identify apoptotic cells. Anal Biochem. 2015;480:37‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yakovlev AG, Faden AI. Caspase‐dependent apoptotic pathways in CNS injury. Mol Neurobiol. 2001;24:131‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jeon BS, Kholodilov NG, Oo TF, et al. Activation of caspase‐3 in developmental models of programmed cell death in neurons of the substantia nigra. J Neurochem. 1999;73:322‐333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim SN, Kim ST, Doo AR, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase/Akt signaling pathway mediates acupuncture‐induced dopaminergic neuron protection and motor function improvement in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Int J Neurosci. 2011;121:562‐569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang W, Yang Y, Ying C, et al. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase‐3beta protects dopaminergic neurons from MPTP toxicity. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:1678‐1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wu Y, Shang Y, Sun S, Liang H, Liu R. Erythropoietin prevents PC12 cells from 1‐methyl‐4‐phenylpyridinium ion‐induced apoptosis via the Akt/GSK‐3beta/caspase‐3 mediated signaling pathway. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1365‐1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maira SM, Stauffer F, Schnell C, Garcia‐Echeverria C. PI3K inhibitors for cancer treatment: where do we stand? Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37(Pt 1):265‐272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Klein PS, Melton DA. A molecular mechanism for the effect of lithium on development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8455‐8459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bijur GN, De Sarno P, Jope RS. Glycogen synthase kinase‐3beta facilitates staurosporine‐ and heat shock‐induced apoptosis. Protection by lithium. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7583‐7590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chalecka‐Franaszek E, Chuang DM. Lithium activates the serine/threonine kinase Akt‐1 and suppresses glutamate‐induced inhibition of Akt‐1 activity in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8745‐8750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zheng L, Bernard‐Marissal N, Moullan N, et al. Parkin functionally interacts with PGC‐1alpha to preserve mitochondria and protect dopaminergic neurons. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:582‐598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Di Giacomo E, Benedetti E, Cristiano L, et al. Roles of PPAR transcription factors in the energetic metabolic switch occurring during adult neurogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2017;16:59‐72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pal R, Tiwari PC, Nath R, Pant KK. Role of neuroinflammation and latent transcription factors in pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Neurol Res. 2016;38:1111‐1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Imayoshi I, Kageyama R. bHLH factors in self‐renewal, multipotency, and fate choice of neural progenitor cells. Neuron. 2014;82:9‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yuan L, Hassan BA. Neurogenins in brain development and disease: an overview. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2014;558:10‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Havrda MC, Paolella BR, Ward NM, Holroyd KB. Behavioral abnormalities and Parkinson's‐like histological changes resulting from Id2 inactivation in mice. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6:819‐827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bove J, Perier C. Neurotoxin‐based models of Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience. 2012;211:51‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dudek H, Datta SR, Franke TF, et al. Regulation of neuronal survival by the serine‐threonine protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;275:661‐665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Timmons S, Coakley MF, Moloney AM. C ON. Akt signal transduction dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2009;467:30‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Beaulieu JM, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. The Akt‐GSK‐3 signaling cascade in the actions of dopamine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:166‐172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Garcia BG, Wei Y, Moron JA, Lin RZ, Javitch JA, Galli A. Akt is essential for insulin modulation of amphetamine‐induced human dopamine transporter cell‐surface redistribution. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:102‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Petit‐Paitel A, Brau F, Cazareth J, Chabry J. Involvment of cytosolic and mitochondrial GSK‐3beta in mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal cell death of MPTP/MPP‐treated neurons. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhu G, Wang X, Wu S, Li Q. Involvement of activation of PI3K/Akt pathway in the protective effects of puerarin against MPP+‐induced human neuroblastoma SH‐SY5Y cell death. Neurochem Int. 2012;60:400‐408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li Y, Xie M, Song X, et al. DEC1 negatively regulates the expression of DEC2 through binding to the E‐box in the proximal promoter. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16899‐16907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Li Y, Song X, Ma Y, Liu J, Yang D, Yan B. DNA binding, but not interaction with Bmal1, is responsible for DEC1‐mediated transcription regulation of the circadian gene mPer1. Biochem J. 2004;382(Pt 3):895‐904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yan YX, Zhao JX, Han S, et al. Tetramethylpyrazine induces SH‐SY5Y cell differentiation toward the neuronal phenotype through activation of the PI3K/Akt/Sp1/TopoIIbeta pathway. Eur J Cell Biol. 2015;94:626‐641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kojima N, Saito H, Nishikawa M, et al. Lithium induces c‐Ret expression in mouse inner medullary collecting duct cells. Cell Signal. 2011;23:371‐379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kumawat K, Menzen MH, Slegtenhorst RM, Halayko AJ, Schmidt M, Gosens R. TGF‐beta‐activated kinase 1 (TAK1) signaling regulates TGF‐beta‐induced WNT‐5A expression in airway smooth muscle cells via Sp1 and beta‐catenin. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials