Summary

Aims

To compare the once‐daily rivastigmine patch 9.5 mg/24 h (10 cm2) versus twice‐daily capsule (12 mg/day) in Chinese patients with probable Alzheimer's disease (AD) (mini‐mental state examination [MMSE] scores of 10–20).

Methods

The primary objective was to demonstrate the noninferiority of patch to capsule in Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale‐Cognitive subscale (ADAS‐Cog) change from baseline to 24 week. Secondary endpoints included cognition (MMSE), overall clinical response (Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study‐Clinical Global Impression of Change [ADCS‐CGIC]), activities of daily living (Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study‐Activities of Daily Living [ADCS‐ADL]), behavior (Neuropsychiatric Inventory [NPI‐12]), and safety.

Results

Similar cognitive improvement was observed in both patch (n = 248) and capsule (n = 253) groups. Statistical noninferiority for ADAS‐Cog was not established (least‐square means difference, 0.1; 95% confidence interval, −1.2; 1.5). Considering all efficacy parameters into account, both treatments showed similar performance at Week 24. Treatment‐related adverse events (AEs) were lower for patch (39.7%) compared with capsule (49.8%). Application site pruritus was reported in 10.9% of patients receiving patch; most cases were mild. Gastrointestinal AEs including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea occurred less frequently in the patch group (15.8% vs. 28.7%).

Conclusion

Rivastigmine patch 9.5 mg/24 h is effective and well tolerated in Chinese patients with probable AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Capsule, Chinese, Rivastigmine, Transdermal patch

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the most common cause of dementia 1. Its prevalence in China was estimated to be 2.3% during years 2001–2005 and 2006–2010 2. In a systematic review, authors estimated 9.19 million cases of dementia with 5.69 million cases of AD in China in 2010 and called for action to tackle the increasing burden on health and social care systems 3.

Currently approved therapies for AD include acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) such as donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine and the N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor antagonist memantine. In China, the AChEI huperzine A and traditional Chinese medicines are also used to treat dementia 4.

The rivastigmine patch (EXELON®, Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland), at the dosages of 4.6 mg/24 h (5 cm2), 9.5 mg/24 h (10 cm2), and 13.3 mg/24 h (15 cm2), is approved in over 90 countries for treating mild to moderately severe AD. It is also approved in the United States and several other countries for the treatment of severe AD (13.3 mg/24 h) and Parkinson's disease dementia (9.5 mg/24 h and 13.3 mg/24 h). Rivastigmine is a slowly reversible (pseudo‐irreversible) and a dual inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase of the carbamate type 5. In addition to the oral formulation, rivastigmine is the only AChEI available as a transdermal patch, which provides continuous drug delivery for a 24‐h period 6.

Previous studies in patients with AD have shown that rivastigmine patch is efficacious in improving cognition, behavioral symptoms, global functions, and activities of daily living (ADL) 7, 8, 9, 10. A large phase III pivotal study, IDEAL (Investigation of transDermal Exelon in ALzheimer's disease), was conducted in mainly Caucasian population across 21 countries to compare the efficacy and safety of rivastigmine patch and capsule 10. The IDEAL study was a 24‐week, double‐blind, double‐dummy, placebo‐, and active‐controlled study which showed that the efficacy of the 9.5 mg/24 h once‐daily (od) rivastigmine patch was similar to that of 6 mg twice‐daily (bid) capsules, measured using the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale‐Cognitive subscale (ADAS‐Cog) 11 and the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study‐Clinical Global Impression of Change (ADCS‐CGIC) scale 10.

This study (ClinicalTrials.gov registration number NCT01399125) was conducted to compare the efficacy and safety of rivastigmine patch (target dose, 9.5 mg/24 h od) versus rivastigmine capsule (target dose, 6 mg bid) in patients with probable AD from China. ADAS‐Cog results from this study were compared with the IDEAL study results in a side‐by‐side fashion.

Methods

Patients

Patients, aged 50–85 years, with probable AD (according to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association [NINCDS/ADRDA] criteria) 12 and with a mini‐mental state examination (MMSE) 13 score between 10 and 20 (inclusive), were enrolled in the study. In addition, patients were included if they had magnetic resonance imaging/computed tomography findings consistent with the diagnosis of AD, performed within 1 year prior to randomization. All patients were required to be living with someone in the community or be in daily contact with a responsible caregiver.

Exclusion criteria included patients with any advanced, severe, progressive, or unstable disease that might interfere with the assessments or put the patient at risk; history or current diagnosis of any condition other than AD that can contribute to dementia; major depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder; active skin lesions/disorders; or hypersensitivity to drugs similar to rivastigmine or to other cholinergic compounds. In addition, patients receiving AChEIs or other approved treatments for AD during the 4 weeks prior to randomization were excluded from the study. Traditional Chinese medicine was allowed if it had been used prior to the study and was expected to remain stable throughout the study.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The study protocol and its amendment were reviewed by the independent ethics committees or institutional review boards at each center. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. Written informed consent was received from each participant (or their authorized representatives) and their caregivers.

Study Design

This 24‐week, prospective, two‐arm, randomized, parallel‐group, double‐blind, double‐dummy, and multicenter trial comprised a 16‐week titration phase and an 8‐week maintenance phase. The study was conducted between July 2011 and May 2013 across 25 centers in China.

After a 4‐week screening period, patients meeting the eligibility criteria were randomized (1:1) to receive either rivastigmine patch, at a target dose of 9.5 mg/24 h, or rivastigmine capsule at a target dose of 6 mg bid.

Rivastigmine patch was initiated at a dose of 4.6 mg/24 h for the first 4 weeks, followed by 9.5 mg/24 h for the remaining 20 weeks. In the capsule group, rivastigmine capsules were initiated at a dose of 1.5 mg bid and gradually up‐titrated every 4 weeks in increments of 1.5 mg bid to a maximum dose of 6 mg bid by Week 16. During the up‐titration, a 4‐weekly visit was conducted. The maximum tolerated patch size and daily dose of capsule were maintained from weeks 16 to 24 (maintenance phase). In case of safety or tolerability issues, dose adjustments (interruptions or down‐titrations) were allowed.

The patch (rivastigmine or placebo) was applied once a day to dry, hairless, and intact healthy skin on the upper or lower back, upper arm, or chest in a place that would not be rubbed by tight clothing. The caregiver was instructed not to apply a new patch exactly to the same location twice within 14 days.

Sample Size, Randomization, and Blinding

A sample size of 177 patients in each group was estimated to achieve a power of 90% to demonstrate noninferiority for rivastigmine patch to capsule formulation based on the primary efficacy variable ADAS‐Cog in the per‐protocol (PP) population. A noninferiority margin of 1.25 points and a standard deviation (SD) of 6.5 points were assumed based on previous studies. The sample size calculation assumed 1‐point advantage, on the ADAS‐Cog change from baseline at Week 24, of rivastigmine patch over capsule based on a subgroup analysis of patients from Taiwan and Korea who participated in the IDEAL study. To account for a proportion of 70% randomized patients available for analysis in the PP population, the sample size was increased to 500 randomized patients. Interactive voice randomization system was used to randomize patients using a validated automatic system. A double‐dummy design (patch group, rivastigmine 9.5 mg/24 h patch plus placebo capsules; capsule group, rivastigmine 6 mg bid capsules plus a dummy patch) was used to ensure blinding of the treatment groups. Unblinding was allowed only in the case of patient emergencies and at the end of the study.

Efficacy Outcomes

Efficacy assessments were performed at baseline and at weeks 8, 16, and 24. The primary efficacy outcome was the change from baseline in the ADAS‐Cog 11 at Week 24. The ADAS‐Cog comprises 11 items that are summed to a total score ranging from 0 to 70, with lower ADAS‐Cog scores indicating less severe impairment. The secondary efficacy outcomes, assessed by independent physicians, were the change from baseline for the following parameters: MMSE 13, the ADCS‐CGIC 10, the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study‐Activities of Daily Living (ADCS‐ADL) 14, and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI‐12) 15. Higher MMSE scores indicate better function. The ADCS‐CGIC scale provides a single global rating of change from baseline. The ADCS‐CGIC is a categorical measure with 7 levels ranging from (1) marked improvement to (7) marked worsening. ADCS‐ADL 14 is a caregiver‐based ADL scale developed for use in dementia clinical studies. The higher the total score, the higher the patient's functioning was. NPI‐12 15 provides a means of distinguishing frequency and severity of changes in behavioral problems and facilitates the rapid behavioral assessment through screening questions. NPI scores are higher with increasing severity of behavioral disturbances.

Safety Outcomes

Safety was assessed by monitoring adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (SAEs), and the discontinuation rate due to AEs throughout the study. Vital signs were recorded at all visits. Electrocardiograms were performed, and laboratory parameters were assessed at screening and at Week 24. Concomitant medication use was monitored.

Statistical Analysis

The PP population comprised all randomized patients who had received at least one dose of the study drug, had a baseline assessment and a Week‐24 assessment on treatment for the primary efficacy variable, and had no major protocol deviations. The intent‐to‐treat (ITT) population comprised all randomized patients who received at least one dose of the study drug, had a baseline assessment, and had at least one postbaseline assessment of the primary efficacy variable. The safety population included all patients who had received at least one dose of the study drug and had at least one postbaseline safety assessment.

For ADAS‐Cog, the difference in least‐square (LS) means between the treatment groups and the two‐sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was calculated using an analysis of covariance (ancova) model with the following explanatory variables: treatment, region, and the baseline total ADAS‐Cog score. The noninferiority of rivastigmine patch to rivastigmine capsule was demonstrated if the upper bound of the two‐sided 95% CI for the difference between treatment groups (rivastigmine patch minus rivastigmine capsule) was <1.25, the predefined noninferiority margin. All efficacy analyses were performed on the PP and ITT populations using both the observed case (OC) and last observation carried forward (LOCF) approaches for the handling of missing data. The study population for confirmatory testing of the noninferiority hypothesis for ADAS‐Cog was the PP population using no imputation of missing data (i.e., with OC, PP [OC]). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the assumptions in the primary analysis. For ADCS‐ADL, NPI‐12, and MMSE, treatment comparisons for change from baseline to Week 24 were based on an ANCOVA model with “treatment group” and “region” as factors, and “baseline score” as a covariate. For ADCS‐CGIC, treatment comparisons were based on the proportion of subjects with improvement (defined as marked, moderate, or minimal improvement). Safety data were analyzed descriptively according to the treatment received and the study period.

Results

Study Population

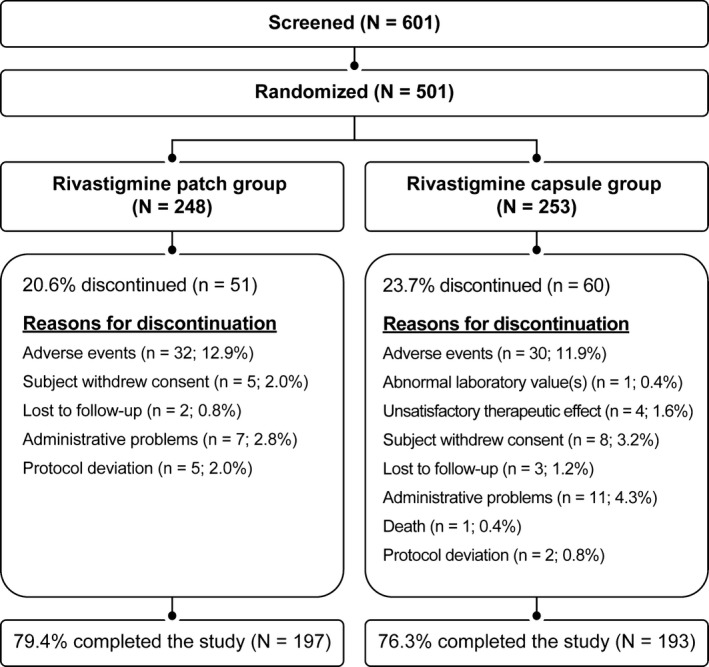

A total of 601 patients were screened, of whom 501 were randomized into either the patch (n = 248) or the capsule (n = 253) group. Overall, 197 (79.4%) and 193 (76.3%) patients in the patch and the capsule group, respectively, completed the study. The primary reason for discontinuation was AEs in both groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition (randomized population).

The treatment groups were similar with respect to age, sex, living situation, and time because first symptom was diagnosed by a physician. Demographical and baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Compared with the capsule group, the patch group had slightly more patients in the older age group of 75 to <85 years and fewer patients in the younger age group of <65 years. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) MMSE score was 16.0 (3.46) for the patch group and 16.6 (3.08) for the capsule group. A higher proportion of patients in the patch group reported the previous use of AChEIs compared with the capsule group (25.4% vs. 19.8%, respectively).

Table 1.

Patient demographical and baseline characteristics (randomized population)

| Rivastigmine patch n = 248 | Rivastigmine capsule n = 253 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years Mean (SD) | 70.4 (8.02) | 69.8 (8.20) |

| Age group (years), n (%) | ||

| <65 | 60 (24.2) | 75 (29.6) |

| 65 to <75 | 92 (37.1) | 97 (38.3) |

| 75 to <85 | 95 (38.3) | 81 (32.0) |

| ≥85 | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 108 (43.5) | 114 (45.1) |

| Female | 140 (56.5) | 139 (54.9) |

| Time since first symptom of AD was noticed by a physician (years), mean (SD) | 1.3 (2.27) | 1.1 (1.59) |

| Patient's living situationa, n (%) | ||

| Living alone | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.2) |

| Living with caregiver or other individual | 245 (98.8) | 249 (98.4) |

| Assisted living/group home | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Mini‐Mental State Examinationa | ||

| Mean (SD) | 16.0 (3.46) | 16.6 (3.08) |

| Previous AChEI usage, n (%) | 63 (25.4) | 50 (19.8) |

Assessed at baseline visit.

AChEI, Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor; AD, Alzheimer's disease; SD, standard deviation.

Concomitant medications including herbal medication use were similar (57.5% and 56.2% in the patch and capsule groups, respectively) in both the groups and primarily comprised of drugs administered in elderly population for other comorbid conditions.

At the end of the study (weeks 20–24), the mean (SD) rivastigmine mean dose was 9.4 cm2 (1.59) for the patch group and 9.7 (3.09) mg/day for the capsule group. The patch allowed more patients to reach the target dose for at least 4 weeks of the maintenance phase compared with the capsule (88.5% vs. 58.4%, respectively). In addition, fewer patients required down‐titration or interruption due to side effects in the patch group (20.2%) than in the capsule group (35.1%).

Efficacy Results

Cognition was assessed using ADAS‐Cog as the primary measure and MMSE as the secondary measure. Similar cognitive improvements in ADAS‐Cog from baseline were observed at all time points in both treatment groups in all populations (Table 2). The difference of LS means (DLSM) (95% CI) of rivastigmine patch compared with capsule was 0.4 (−0.7, 1.4) at Week 8, 0.1 (−1.0, 1.3) at Week 16, and 0.1 (−1.2, 1.5) at Week 24 for the PP (OC) population. Statistical noninferiority of rivastigmine patch (target dose, 9.5 mg/24 h) to capsule (target dose, 6 mg bid) with respect to the ADAS‐Cog was not established at Week 24 because the upper limit of the 95% CI (−1.2, 1.5) exceeded the prespecified noninferiority margin of 1.25. The numerical difference between the rivastigmine patch versus capsule at Week 24 was 0.1 point and was not clinically relevant.

Table 2.

Change from baseline at Week 24 in ADAS‐Cog, MMSE, ADSC‐ADL, NPI‐12 and the proportion of patients with improvements in ADCS‐CGIC at Week 24 with rivastigmine patch versus rivastigmine capsule (PP [OC], ITT [OC], and ITT [LOCF] populations)

| Outcome measure | Baseline (mean, SD) | LS mean change from baseline at 24 weeks (score, SEM) and DSLM (95% CI) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITT (LOCF) | PP (OC) | ITT (OC) | ITT (LOCF) | ||||||||

| Patch Mean (SD) | Capsule Mean (SD) | Patch LS mean (SEM) | Capsule LS mean (SEM) | DLSM P vs. C at Wk 24 (95% CI) | Patch LS mean (SEM) | Capsule LS mean (SEM) | DLSM P vs. C at Wk 24 (95% CI) | Patch LS mean (SEM) | Capsule LS mean (SEM) | DLSM P vs. C at Wk 24 (95% CI) | |

| ADAS‐Coga |

29.4 (9.46) n = 234 |

28.2 (9.19) n = 232 |

−0.7 (0.5) n = 182 |

−0.9 (0.5) n = 185 |

0.1 (−1.2; 1.5) |

−0.7 (0.5) n = 189 |

−0.7 (0.5) n = 193 |

0.0 (−1.3; 1.4) |

−0.7 (0.4) n = 234 |

−0.9 (0.4) n = 232 |

0.3 (−0.9; 1.5) |

| MMSEb |

16.0 (3.45) n = 236 |

16.6 (3.11) n = 238 |

0.8 (0.2) n = 192 |

0.7 (0.2) n = 188 |

0.1 (−0.6; 0.7) |

0.8 (0.2) n = 199 |

0.7 (0.2) n = 196 |

0.1 (−0.6; 0.7) |

0.7 (0.2) n = 236 |

0.7 (0.2) n = 238 |

0.0 (−0.6; 0.6) |

| ADCS‐ADLb |

51.1 (13.66) n = 236 |

53.2 (12.53) n = 238 |

−2.0 (0.8) n = 192 |

−1.5 (0.8) n = 188 |

−0.5 (−2.7; 1.7) |

−1.9 (0.8) n = 199 |

−1.5 (0.8) n = 196 |

−0.4 (−2.6; 1.7) |

−1.6 (0.7) n = 236 |

−1.8 (0.7) n = 238 |

0.1 (−1.8; 2.1) |

| NPI‐12a |

11.1 (15.14) n = 235 |

9.7 (13.66) n = 237 |

−0.8 (0.7) n = 192 |

−1.5 (0.7) n = 188 |

0.7 (−1.3; 2.6) |

−0.7 (0.7) n = 199 |

−1.5 (0.7) n = 196 |

0.8 (−1.1; 2.6) |

−0.7 (0.6) n = 235 |

−0.9 (0.6) n = 238 |

0.3 (−1.4; 1.9) |

| Proportion of patients with improvement for ADCS‐CGIC (%, n, 95% CI for difference in proportions) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP(OC) | ITT(OC) | ITT(LOCF) | |||||||||

| Patch (%) | Capsule (%) | Difference (95% CI) | Patch (%) | Capsule (%) | Difference (95% CI) | Patch (%) | Capsule (%) | Difference (95% CI) | |||

| ADCS‐CGICc |

41.1 (n = 79) n = 192 |

38.5 (n = 72) n = 187 |

2.6 (−7.21; 12.5) |

41.2 (n = 82) n = 199 |

37.9 (n = 74) n = 195 |

3.3 (−6.39; 12.91) |

38.6 (n = 91) n = 236 |

36.1 (n = 86) n = 238 |

2.4 (−6.28; 11.13) | ||

ADAS‐Cog and NPI‐12: A negative change indicates an improvement from baseline. A negative difference (DLSM) indicates greater improvement in rivastigmine patch as compared to rivastigmine capsule.

MMSE and ADCS‐ADL: A positive change indicates an improvement from baseline. A positive difference (DLSM) indicates greater improvement in rivastigmine patch as compared to rivastigmine capsule.

Improvement in ADCS‐CGIC is defined as marked, moderate, or minimal improvement.

ADAS‐COG, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale‐Cognitive subscale; ADCS‐ADL, Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study‐ Activities of Daily Living; ADCS‐CGIC, Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study‐Clinical Global Impression of Change; CI, confidence interval; DLSM, difference of least‐square means; ITT (LOCF) intent‐to‐treat (last observation carried forward); ITT (OC), intent‐to‐treat (observed case); LS, least squares; MMSE, mini‐mental state examination; NPI‐12, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; PP (OC) population, PP population using no imputation of missing data, that is, with observed cases; P versus C, rivastigmine patch versus capsule; SD, standard deviation; SEM, standard error of the LS means; Wk, week.

Figures in parentheses indicate 95% confidence limits, unless stated otherwise. 95% confidence limits are based on an analysis of covariance model adjusted for treatment group, region, and baseline score and p values for ADCS‐CGIC are based on Cochran‐Mantel–Haenszel test (Van Elteren) adjusted for region.

Both treatment groups showed cognitive improvement as assessed by MMSE with a slight numerical advantage in mean MMSE scores of 0.1 points in the patch group compared with the capsule group (Table 2). The DLSM for MMSE scores of patch versus capsule in the PP (OC) population was −0.3 (−0.8, 0.3) at Week 8, 0.6 (−0.0, 1.2) at Week 16, and 0.1 (−0.6, 0.7) at Week 24 (Table 2).

In the global assessment (ADCS‐CGIC) for the PP population, the proportion of patients with improvement (sum of marked, moderate, and minimal improvement) was similar in both treatment groups at Week 8 (34.6% vs. 35.1% for patch and capsule groups, respectively) and higher in the patch group than in the capsule group at weeks 16 (45.8% vs. 32.6%, respectively) and 24 (41.1% vs. 38.5%, respectively). Regarding the ADCS‐ADL total score, the change from baseline was similar in the patch and capsule groups at Week 24 (Table 2). Both treatment groups showed slight improvement in the NPI‐12 scale from baseline at Week 24.

The outcomes of other prespecified sensitivity analyses were consistent with the results described.

Efficacy assessments at Week 24 based on PP (OC), ITT (OC), and ITT (LOCF) populations are presented in Table 2.

Safety Results

No unexpected safety signals were observed in either treatment group. The safety results in the study were similar to those in the IDEAL study 10. AEs were generally less common with rivastigmine patch, occurring in 56.7% of patients compared with 62.5% of patients with rivastigmine capsule. In both groups, a majority of AEs were mild (patch, 35.2%; capsule, 33.1%) or moderate in severity (patch, 14.2%; capsule, 20.7%). In addition, fewer patients required down‐titration or interruption due to side effects in the patch group (20.2%) than in the capsule group (35.1%).

Overall, the most common AEs reported in >2% of patients in any group with at least a between‐group difference of 2% were decreased appetite, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, weight decreased, somnolence, hypertension, and application site pruritus.

A similar proportion of patients discontinued the study due to an AE in the patch and the capsule groups (12.9% vs. 11.9%, respectively; Figure 1). Discontinuations due to nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or decreased appetite were lower in the patch group than in the capsule group (1.6% vs. 4.4%, respectively).

Overall, 6.5% of patients in the patch group and 8.4% in the capsule group experienced SAEs. In the capsule group, one death occurred during the study including the 30‐day follow‐up period, and this was not considered related to the study drug. A higher proportion of patients in the capsule group experienced AEs considered to be related to study medication than those in the patch group (49.8% vs. 39.7%). The most frequently reported drug‐related AEs (>2% in any group) were nausea, vomiting, application site pruritus, weight decreased, decreased appetite, somnolence, and dizziness. With the exception of application site pruritus, all these events were reported more frequently in the capsule group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Most frequent treatment‐related adverse events (>2%) in any treatment group, by preferred term and treatment group (safety population)

| Preferred term | Rivastigmine patch n = 247 n (%) | Rivastigmine capsule n = 251 n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Any AE possibly or probably related to treatment by the investigator | 98 (39.7) | 125 (49.8) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 30 (12.1) | 58 (23.1) |

| Nausea | 18 (7.3) | 29 (11.6) |

| Vomiting | 16 (6.5) | 25 (10.0) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 45 (18.2) | 25 (10.0) |

| Application site pruritus | 27 (10.9) | 7 (2.8) |

| Investigations | 11 (4.5) | 16 (6.4) |

| Weight decreased | 9 (3.6) | 16 (6.4) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 16 (6.5) | 36 (14.3) |

| Decreased appetite | 15 (6.1) | 36 (14.3) |

| Nervous system disorders | 17 (6.9) | 35 (13.9) |

| Dizziness | 12 (4.9) | 20 (8.0) |

| Somnolence | 4 (1.6) | 11 (4.4) |

Primary system organ classes are presented alphabetically.

A patient with multiple occurrences of an AE within a preferred term is counted only once.

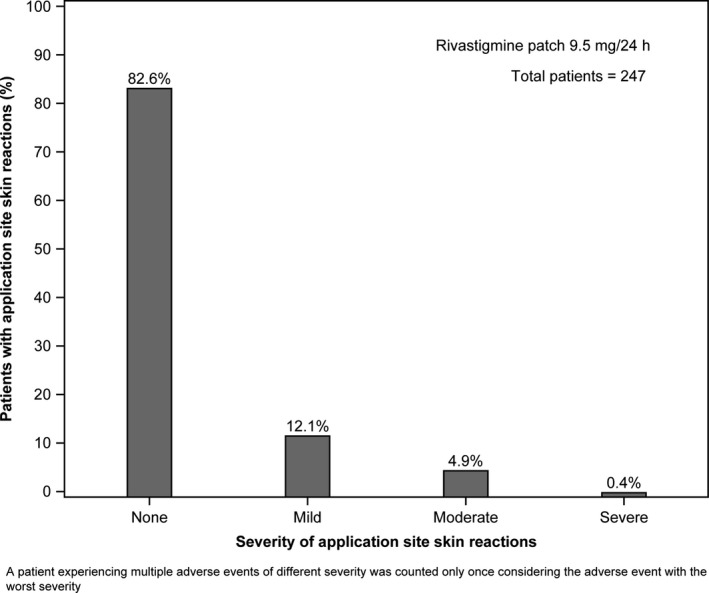

Cholinergic gastrointestinal (GI) AEs including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea were less frequent in the patch group than the capsule group (15.8% vs. 28.7%). Application site pruritus was the most common AE in the patch group compared with the capsule group (10.9% vs. 2.8%, respectively). A majority (82.6%) of patients treated with rivastigmine patch did not report any application site skin reactions, and most of the reported events were mild in severity (Figure 2). AEs of application site reactions leading to discontinuation were observed in 4.9% of patch group patients and 0.8% of capsule group patients.

Figure 2.

Overall incidence of application site skin reactions in the 10 cm2 rivastigmine patch group (safety population).

Other AEs of interest and importance in such an elderly population include cardiac disorders and convulsions. AEs of cardiac disorders were low in both groups: 4 (1.6%) patients in the patch group and 6 (2.4%) in the capsule group. Of these, only 1 (0.4%) and 3 (1.2%) patients respectively discontinued. No convulsions or bradycardia was reported by any patient in this study.

Overall, no significant changes from baseline to Week 24 were noted between the treatment groups in hematology and biochemistry laboratory assessments. Only one patient in each group had a clinically notable increased level of alanine aminotransferase value (≥3 × ULN).

No clinically meaningful change in electrocardiogram recordings and vital signs, such as blood pressure and heart rate, was observed from baseline to Week 24 in any treatment group, and no patient reported a heart rate below 50 bpm.

A similar proportion of patients showed a clinically notable decrease (≥7%) in body weight (patch, 11.7%; capsule, 13.9%), and a higher proportion of patients in the patch group (16.2%) experienced a clinically notable weight increase (≥7%) compared with those in the capsule group (6.8%) during the study. Overall, the patch group patients reported a stable weight with a mean weight gain (SD) of 0.03 kg (3.201), while the capsule group patients reported a mean weight loss of 0.49 kg (3.234).

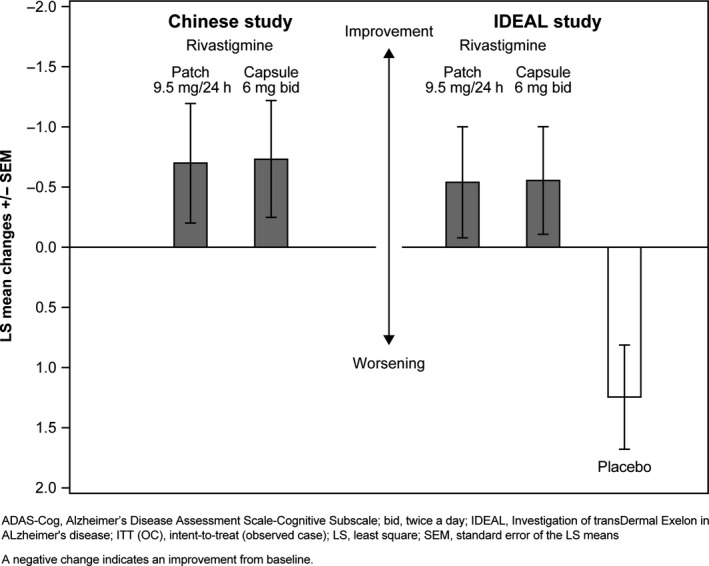

Side‐By‐Side Comparison of ADAS‐Cog Results in the IDEAL Study in a Mainly Caucasian Population versus the Chinese Study

The similarity in ADAS‐Cog results between rivastigmine patch and rivastigmine capsule was further confirmed by a side‐by‐side comparison of this study in Chinese patients and the IDEAL study in a global population (13). The LS means for change from baseline in ADAS‐Cog at Week 24 are presented from the single‐study analyses of this study and of the IDEAL study in a side‐by‐side fashion. The ANCOVA model used for the IDEAL study included “treatment group” and “country” as factors, and “baseline score” as a covariate. The IDEAL study was chosen as a suitable study for comparison due to the similarities in the study populations, the time points of assessments, and the dosage administration in both treatment groups. In addition, the IDEAL study included a placebo arm. This analysis was conducted in the ITT (OC) population, which can be considered sufficiently similar between the two studies to allow a side‐by‐side comparison. In both these studies, changes from baseline on ADAS‐Cog were analyzed using ANCOVA.

A consistent pattern for ADAS‐Cog LS mean change from baseline to Week 24 was shown with both rivastigmine 9.5 mg/24 h od patch and 6 mg bid capsule in both studies (Figure 3). The LS mean change from baseline to Week 24 (standard error of LS means [SEM]) in ADAS‐Cog for the Chinese study is presented in Table 2. In the ITT (OC) population of the IDEAL study, the LS mean change from baseline to Week 24 (SEM) in ADAS‐Cog was −0.5 (0.5) for patch, −0.5 (0.5) for capsule, and 1.3 (0.4) for placebo. The observed numerical difference (DLSM and 95% CI) between patch and capsule was 0.01 (−1.21, 1.24) points.

Figure 3.

Change from baseline at Week 24 in ADAS‐Cog total score by treatment group—Chinese study and IDEAL study (ITT [OC] population).

The efficacy of the 9.5 mg/24 h od patch was similar to that of the 6 mg bid capsule.

Discussion

The results of this study show similar efficacy of once‐daily transdermal rivastigmine patch and oral bid capsules in Chinese patients with mild‐to‐moderate AD, with the patch being better tolerated than capsule.

Cognition was measured using ADAS‐Cog and MMSE. The primary objective of statistical noninferiority of rivastigmine patch to capsule in ADAS‐Cog was not established. In the primary PP (OC) analysis, the LS mean change from baseline to Week 24 (SEM) in ADAS‐Cog was −0.7 (0.5) for patch and −0.9 (0.5) for capsule. The DLSM (95% CI) was small (0.1 [−1.2, 1.5]) and not clinically meaningful. A clinical improvement from baseline was observed in the ADAS‐Cog in both rivastigmine patch and capsule groups at all evaluated time points.

The failure to achieve noninferiority may be attributed to the assumption of a 1‐point advantage in ADAS‐Cog of the patch group compared with the capsule group made at the time when the study was designed. This assumption was based on the results from a subgroup analysis of the Asian countries included in the IDEAL study. Patients from Taiwan and South Korea reported a baseline to Week 24 difference in ADAS‐Cog of 1.3 and 1.8, respectively, in favor of rivastigmine patch (Novartis, data on file). However, the observed results do not indicate a clinically relevant difference between patch or capsule or a larger variability in Chinese patients compared to previous trials.

Cognition as measured by MMSE showed similar improvement versus baseline at all time points for both the patch and the capsule groups, with a slight numerical advantage of 0.1 points in the patch group at week 24.

Traditionally, in addition to cognition, efficacy in AD is assessed using various domains (e.g., overall clinical response, activities of daily living, behavior). The similarity in efficacy is further supported by the results of overall clinical response, which revealed that the proportion of patients showing improvement was higher in the patch group than in the capsule group. Both treatments had similar effect on ADLs, as assessed by the patient's caregiver, and the small numerical differences observed across populations were considered to be driven by variability. As expected, in the current study both groups showed minimal behavioral changes, because of the wide range of the NPI scale and the low baseline values of both patch and capsule (11.1 and 9.7, respectively). In previous studies, behavioral changes measured by NPI‐12 scales did not have significant differences in patients administered rivastigmine patch or capsule in different doses at week 24 and as compared to baseline 8, 10.

Taking all efficacy domains into account, both rivastigmine patch and capsule were found to be similar.

The authors recognize that the 4‐week washout period prior to baseline assessment does not always reflect real‐life conditions, where patients are often switched directly from oral AChEIs to oral or transdermal rivastigmine 16. Sadowsky et al. suggested in a review that patients are to be switched, if indicated for any reason, to rivastigmine patch immediately without a washout period 16. Assay sensitivity may be raised as a discussion point for noninferiority trials. Therefore, the current trial should also be seen in the context of the three‐arm, placebo‐controlled trial IDEAL 10, in which superiority of the patch and the capsule treatment was established over placebo.

The IDEAL 10 study, with a similar patient population except that the majority were Caucasians, showed similar changes in ADAS‐Cog. In addition, a side‐by‐side comparison of IDEAL with this study showed the similarities in the effects of rivastigmine patch and capsule in patients with AD in terms of ADAS‐Cog. The overall incidence of AEs was lower in the patch group than the capsule group, especially for GI, metabolism and nutrition, and nervous system disorders. Acute cholinergic side effects such as nausea and vomiting have been associated with high maximum blood plasma drug levels, which occur rapidly after capsule administration 17. This study showed that rivastigmine 9.5 mg/24 h patch is well tolerated in Chinese patients with AD, with no new or unexpected safety findings. The safety results observed in the study were similar to those observed in the IDEAL study 10.

The patch administration is advantageous over capsules as it reduces fluctuation in drug levels and allows smoother and more continuous drug delivery, resulting in decreased GI side effects 18. Rivastigmine patch, with once‐a‐day dosing without the need to administer with food and only a one‐step titration to a therapeutic dose, offers the advantage of improved caregiver and patient convenience. This, together with improved tolerability, is likely to lead to an improvement in patient compliance in routine clinical practice 18. A shift from the oral formulation to the patch offers potential practical advantages and allows access to optimal dose with much improved tolerability without compromising efficacy 16.

Application site pruritus reported in rivastigmine patch‐treated patients was mostly mild in severity. Patients with AD mostly belong to an older age group and are at a higher risk of developing cardiac disorders, including high blood pressure 18 and cardiac rhythm disturbances 19. Data with the rivastigmine patch do not indicate an increased risk of cardiac AEs 20.

The overall conclusion of the study is that the od rivastigmine patch (9.5 mg/24 h [10 cm2]) is effective and well tolerated in Chinese patients with probable AD.

Conflict of Interest

The authors Zhen‐Xin Zhang, Zhen Hong, Yan‐Ping Wang, Li He, Ning Wang, Zhong‐Xin Zhao, Gang Zhao, and Lan Shang declare no conflict of interest. Marianne Weisskopf, Francesca Callegari, and Christine Strohmaier are full‐time employees and stock holders of Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland.

This article has not been previously published, nor is it under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the assistance of the other clinical investigators and their site staff: Xin Yu, Luning Wang, Peixian Mao, Haibo Chen, Weiwei Zhang, Beijing; Shifu Xiao, Shengdi Cheng, Yansheng Li, Shanghai; Xiaoshan, Wang, Qi Wan, Nanjing; Baorong Zhang, Hangzhou; Chunfeng Liu, Suzhou; Yan Liu, Xiaoping Pan, Guangzhou; Shenggang Sun, Ronghua Tang, Wuhan; and Jiang Wu, Jilin. This study was sponsored by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Medical writing and editorial assistance for this manuscript were provided by Hemant Kumar Mittal at Novartis Healthcare Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad, India.

References

- 1. Qiu C, Kivipelto M, von Strauss E. Epidemiology of Alzheimer's disease: Occurrence, determinants, and strategies toward intervention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2009;11:111–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang Y, Xu Y, Nie H, et al. Prevalence of dementia and major dementia subtypes in the Chinese populations: A meta‐analysis of dementia prevalence surveys, 1980‐2010. J Clin Neurosci 2012;19:1333–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chan KY, Wang W, Wu JJ, et al. Epidemiology of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia in China, 1990‐2010: A systematic review and analysis. Lancet 2013;381:2016–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sun ZK, Yang HQ, Chen SD. Traditional Chinese medicine: A promising candidate for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Transl Neurodegener 2013;2:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nordberg A, Ballard C, Bullock R, Darreh‐Shori T, Somogyi M. A review of butyrylcholinesterase as a therapeutic target in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2013;15: PCC. 12r01412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kurz A, Farlow M, Lefevre G. Pharmacokinetics of a novel transdermal rivastigmine patch for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: A review. Int J Clin Pract 2009;63:799–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cummings J, Froelich L, Black SE, et al. Randomized, double‐blind, parallel‐group, 48‐week study for efficacy and safety of a higher‐dose rivastigmine patch (15 vs. 10 cm(2)) in Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2012;33:341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Farlow MR, Grossberg G, Gauthier S, Meng X, Olin JT. The ACTION study: Methodology of a trial to evaluate safety and efficacy of a higher dose rivastigmine transdermal patch in severe Alzheimer's disease. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:2441–2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grossberg G, Meng X, Olin JT. Impact of rivastigmine patch and capsules on activities of daily living in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2011;26:65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Winblad B, Cummings J, Andreasen N, et al. A six‐month double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled study of a transdermal patch in Alzheimer's disease–rivastigmine patch versus capsule. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;22:456–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1984;141:1356–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: Report of the NINCDS‐ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology 1984;34:939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini‐mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Galasko D, Bennett D, Sano M, et al. An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease. The Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997;11(Suppl 2):S33–S39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg‐Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994;44:2308–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sadowsky C, Perez JA, Bouchard RW, Goodman I, Tekin S. Switching from oral cholinesterase inhibitors to the rivastigmine transdermal patch. CNS Neurosci Ther 2010;16:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jann MW, Shirley KL, Small GW. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cholinesterase inhibitors. Clin Pharmacokinet 2002;41:719–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wentrup A, Oertel WH, Dodel R. Once‐daily transdermal rivastigmine in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Drug Des Devel Ther 2008;2:245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jousilahti P, Vartiainen E, Tuomilehto J, Puska P. Sex, age, cardiovascular risk factors, and coronary heart disease: A prospective follow‐up study of 14 786 middle‐aged men and women in Finland. Circulation 1999;99:1165–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stern S, Behar S, Gottlieb S. Cardiology patient pages. Aging and diseases of the heart. Circulation 2003;108:e99–e101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]