Summary

Aims

Intravenous transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) had been documented to improve functional outcome after ischemic stroke. However, the timing and appropriate cell number of transplantation to achieve better outcome after an episode of stroke remain further to be optimized.

Methods

To determine the optimal conditions, we transplanted different concentrations of BMSCs at different time points in a rat model of ischemic stroke. Infarction volume and neurological behavioral tests were performed after ischemia.

Results

We found that transplantation of BMSCs at 3 and 24 h, but not 7 days after focal ischemia, significantly reduced the lesion volume and improved motor deficits. We also found that transplanted cells at 1 × 106 to 107, but not at 1 × 104 to 105, significantly improved functional outcome after stroke. In addition to inhibiting macrophages/microglia activation in the ischemic brain, BMSC transplantation profoundly reduced infiltration of gamma delta T (γδT) cells, which are detrimental to the ischemic brain, and significantly increased regulatory T cells (Tregs), along with altered Treg‐associated cytokines in the ischemic brain.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that timing and cell dose of transplantation determine the therapeutic effects after focal ischemia by modulating poststroke neuroinflammation.

Keywords: Injury, Ischemia, Marrow mesenchymal stem cells, Neuroinflammation, Stroke, Transplantation

Introduction

Stroke is the leading cause of severe long‐term disability in the world. At present, there is no effective treatment for stroke. Stem cell transplantation offers a new and exciting approach for stroke treatment, as many studies have demonstrated favorable results in animal models with various stem cell sources. Several early Phase I and II clinical trials are now underway with promising outcomes 1, 2, 3. However, cell transplantation for stroke therapy is still in its infancy, with many problems that need to be resolved in order to achieve full potential as a therapy. Among the major hurdles for successful clinical application is determining the optimal conditions of transplantation for stroke treatment, which include the following aspects: (1) Optimal timing of cell transplantation: stem cell therapy will prolong the therapeutic time window for other interventions, thus benefitting many stroke patients. The appropriate time for transplantation, however, is unknown. The literature has reported a wide range of successful stroke‐to‐transplantation intervals, including acute, subacute, and chronic phases. A comparison of these data to determine an optimum time window is difficult as the studies used different models of stroke, methods of cell delivery, cell types, and behavioral tests to assess effectiveness, thus highlighting a need for direct comparisons using a standardized approach. (2) Optimal route and site of cell delivery: two main routes of stem cell delivery have been used, the first being intracerebral transplantation into the brain. Given that stroke often results in a large area of infarction, whether such a targeted method can offer efficient engraftment remains largely unknown. An additional concern with this approach is the invasive nature of stereotaxic transplantation. An alternative route that can be considered is intravascular injection. This approach does not necessarily depend on cellular replacement, but rather on the activation of the self‐repair mechanisms in the brain. Although both approaches can improve functional recovery after stroke 4, 5, the optimal route is still not apparent. (3) Optimal number of transplanted cells: a wide range of cell numbers (1 × 104 to 2 × 107) has been used for transplantation in animal models of stroke and in the clinic setting, with improved functional recovery observed after stroke. This raised the question of whether transplantation of more cells would result in a better functional outcome.

A variety of cell types, including neural stem cells (NSCs) and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), have been studied in the animal models of stroke. Of these, BMSCs may have the largest therapeutic potential, as they can be harvested from the patients themselves, avoiding possible ethical concerns or immunological problems 6, 7. Many studies have shown that implanted BMSCs significantly improve motor deficits by differentiating into mature neuronal cells and/or by releasing a number of growth factors that can protect damaged neural cell death 8, 9. Originally, stem cells appear to work by a “cell replacement” mechanism. Currently, cell therapy is considered to provide trophic support to rescue the injured cells, fostering brain repair 3. However, the mechanisms of which BMSCs‐mediated neuroprotection after focal ischemia remains largely unexplored. Studies have shown that molecular and cellular mediators of inflammatory responses play critical roles in the second injury progress after ischemic stroke. As BMSCs have immune modulating properties and can inhibit dendritic cell maturation, B and T cell proliferation and differentiation, attenuate natural killer cell activity, we therefore asked whether BMSCs could improve functional outcome by modulating poststroke neuroinflammation.

In this study, we have investigated the effect of optimal timing and different amounts of BMSC transplantation on the functional outcome in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. In addition, we also asked whether optimal BMSC transplantation was able to modulate poststroke inflammatory response in vivo in general and modulate the number of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) and gamma delta T (γδT) cells in particular. In addition, we confirmed the effects of BMSCs on inflammatory cells and associated cytokines by co‐culture of human‐derived BMSCs with human peripheral immune cells in vitro.

Materials and methods

Focal Cerebral Ischemia

Sprague–Dawley rats (SD; body weight, 270~320 g) were anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate. Permanent distal middle cerebral artery occlusion (dMCAO) was performed as described previously 10, 11. Briefly, the dura was incised and the left MCA was exposed and occluded by electrocoagulation. Immediately thereafter, both carotid arteries (CCAs) were occluded with micro‐clips and rats underwent simultaneous occlusion of the MCA and both CCAs for 60 min. Rectal temperature was maintained at 37.0 ± 0.5°C using a thermostat‐controlled heating pad. All animal procedures were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wenzhou Medical University and conducted according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and every effort was made to minimize suffering and reduce the number of animals used.

Infarction Volume Measurement

Rats were sacrificed 14 or 21 days after dMCAO. Rat brains were embedded in paraffin, cut into 5‐μm coronal sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Stained sections were scanned on a desktop scanner, and infarct area was measured using the NIH Image software. Infarct volume is expressed as the percentage of ipsilesional hemisphere compared with the contralesional hemisphere 12.

Neurobehavioral Tests

Rats underwent neurobehavioral tests (n = 8–12 per group) to evaluate functional outcome. The neurobehavioral tests, including the (1) beam walking test, (2) cylinder test, and (3) elevated body swing test (EBST), were performed according to our previous publications 13. Animals were trained prior to the surgery, and deficits were assessed, respectively, 3, 5, 7, and 14 days to determine the optimal dose of transplantation and 3, 6, 14, and 21 days for determining the optimal window of transplantation. The observer was blinded to the experimental condition.

Rat BMSC Preparation and Culture

Rat BMSCs were isolated and cultured as described previously 14. In brief, the bone marrow was obtained from the femurs and tibias taken from male SD rats. Harvested cells were sieved through a 70‐μm nylon mesh and washed twice with medium, the BMC suspension was diluted with PBS and transferred slowly onto Percoll–Paque Plus, and the material was centrifuged for 25 min. The mononuclear cell ring was collected and washed twice with Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium‐low glucose (DMEM‐LG, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). The cells were then suspended in 5 mL DMEM‐LG with 10% FCS (HyClone), 100 IU/mL of penicillin, 100 IU/mL of streptomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and plated in 25‐cm2 flasks at a density of 1 × 106 cells per dish. After 3 days of culture with 5% CO2 at 37°C, nonadherent hematopoietic cells were removed, and the medium was replaced. When the adherent cells grew to 80% confluence, samples were obtained and defined as passage zero (P0) cells. Rat BMSCs were immunophenotypically characterized by flow cytometry using the following monoclonal antibodies (all from eBioscience; 1:100 dilution): CD90‐FITC, CD29‐PE, CD45‐APC. The cells were then washed and loaded onto the flow cytometer (FACS calibur, BD, San Jose, CA, USA), and the data were analyzed by the Flowjo software. Each fluorescence analysis included appropriate PE‐, FITC‐, APC‐, and Percp 5.5‐conjugated negative isotype control.

Cell Transplantation

Rat BMSCs were harvested at passage 5 and centrifuged (112 g). The pellet was re‐suspended in 0.5 mL sterilized PBS and injected into the vein of the rat tail after dMCAO. To determine the optimal cell number for transplantation, BMSCs at 1 × 104, 1 × 105, 1 × 106, 2 × 106, and 1 × 107 were transplanted 24 h after focal ischemia. PBS was used as the vehicle. To determine the optimal window for transplantation, 2 × 106 and 1 × 107 BMSCs or PBS were transplanted 3 h, 24 h, and 7 days after MCAO. Data were collected from animals before surgery and 3, 6, 14, and 21 days after dMCAO (n = 8–14).

Human BMSC and Immune Cell Co‐cultures

Research was conducted in compliance with the policies and principles contained in the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects and approved by the Institutional Research Review Board at the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University. Human BMSCs (hBMSCs) (n = 8) were obtained from healthy volunteer donors at the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical College after informed consent. The mean age of the donors was 36 ± 5 years (ranging from 31 to 53 years). The bone marrow aspirate (10 mL) was diluted in PBS and gently layered onto a Percoll cushion for density gradient centrifugation. The low density of hBMSCs‐enriched mononuclear cells were collected and re‐suspended in α‐MEM containing 10% FBS and plated at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL into a 25 cm2 tissue culture flask. The cultures were then incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere supplemented with 5% CO2. After 72 h, nonadherent cells in the supernatant were removed, and the medium was completely replaced with fresh medium. hBMSCs (passage 3–5) were immunophenotypically characterized by flow cytometry using the following monoclonal antibodies (all from BD Biosciences; 1:20 dilution): CD90‐FITC, CD44‐PE, CD73‐APC, CD105‐Percp 5.5, CD34‐PE, CD11b‐PE, CD19‐PE, CD45‐PE, and HLA‐DR‐PE. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were collected from peripheral blood (n = 5) by density gradient centrifugation under sterile conditions and washed twice in RPMI‐1640, then suspended in culture medium (RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS) at a density of 2 × 106 cells/mL for use. Human BMSCs obtained after 3–4 passages were seeded into six‐well plates at a density of 10 × 104 cells/well suspended in 2 mL of hBMSCs' complete medium overnight. The unstimulated PBMCs (1 × 106) were then co‐cultured with the plated hBMSCs (1 × 105) for 1 or 4 days in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells without hBMSCs were designated the control group. The experiments were repeated at least three times for each time point.

Isolation of Immune Cells from Brains

Isolation of brain immune cells was performed following the well‐established method with a few modifications 15. Briefly, rat forebrain hemispheres (n = 6 per group) were removed after thorough perfusion with 200 mL of ice‐cold PBS. Hemispheres were minced into small pieces in ice‐cold RPMI‐1640 medium. Brain tissue was then digested with 1 mg/mL collagenase type IV for 45 min at 37°C. Digested tissue was filtered through 70‐μm cell strainers to prepare single cell suspension in 30% Percoll. Cells were then subjected to Percoll gradient isolation by centrifugation at 500 g for 20 min. The cellular interlayer between 37% Percoll and 70% Percoll was collected and washed twice with cold PBS for flow cytometric staining.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

For cell surface marker staining, the following fluorochrome‐conjugated anti‐rat antibodies were used (all from eBioscience unless otherwise indicated): PE anti‐TCRγδ (V659; 1:200), APC anti‐CD3 (G4.18; 1:100), FITC anti‐CD4 (OX35; 1:200), APC anti‐CD25 (OX‐39; 1:100), PE anti‐Foxp3 (PEFJK‐16s, 1:100), FITC anti‐CD45 (BD Pharmingen; 1:100), APC anti‐CD11b (BD Pharmingen; 1:20). The following fluorochrome‐conjugated anti‐human antibodies were used (all from BD Biosciences): PE anti‐TCRγδ (B1; 1:20), FITC anti‐CD3 (UCHT1; 1:5), FITC anti‐CD4 (RPA‐T4; 1:5), APC anti‐CD25 (M‐A251; 1:5), PE anti‐CD8 (RPA‐T8; 1:5). Cells were incubated with antibodies for 20 min and washed once with PBS before analysis on a BD FACS Calibur flow cytometer. For Treg detection, AlexaFluor‐488 anti‐mouse/rat/human Foxp3 (150D; 1:100 for rat and 1:5 for human) was used. Cells were fixed and permeabilized with Fix/Perm Buffer (Biolegend) as per manufacturer's instructions. For cell sorting, stained cells were sorted on a FACS machine, and the results were analyzed using FlowJo 7.6.1 software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, VA, USA).

Enzyme‐Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Rat ipsilateral or contralateral hemispheres were homogenized in PBS containing 1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected. Levels of IL‐6, IL‐10, IL‐1β, IL‐2, TNF‐α, TGF‐β, and IFN‐γ were measured using corresponding ELISA kits (R&D). Extracts from all brain tissue were assayed in duplicates. The optical density was determined by a microplate reader set to 450 nm with wavelength being 540 nm.

Cytometric Bead Array (CBA)

Levels of hIL‐2, hIL‐4, hIL‐6, hIL‐10, hIFN‐γ, hTNF‐α, and hIL‐17 in cell culture supernatant were measured with CBA human Th1/Th2/Th17 Cytokine Kit (BD, Biosciences), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mixed capture beads (containing hIL‐2, hIL‐4, hIL‐6, hIL‐10, hIFN‐γ, hTNF‐α, and hIL‐17) were added into each sample; Th1/Th2/Th17 PE detection Reagent was then added into all tests and incubated for 3 h at room temperature. Similarly, hTGF‐β level was measured using the BD CBA Human Soluble Protein Master Buffer Kit (BD, Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The beads were washed, resuspended, and then loaded on the FACS Calibur. Data were analyzed using the FCAP Array Software (BD, Bioscience).

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis. The results are presented as mean ± SEM. One‐way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's T3 post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. While comparing two groups, a two‐tailed Student's t‐test was used to determine statistical significance. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Optimization of Transplantation Conditions Reduced Lesion Size and Improved Motor Deficits

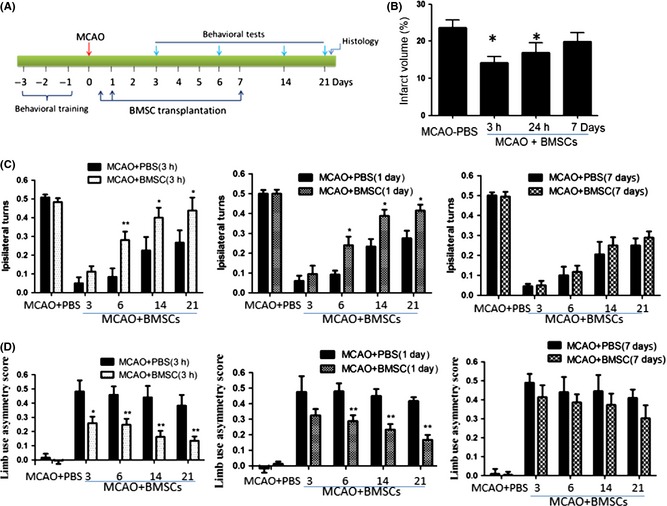

Rat‐ and human‐derived BMCs were cultured, and they displayed typical spindlelike or starlike morphology (data not shown). Flow cytometry analysis indicated that rat‐derived BMCs were uniformly positive for CD90 and CD29, and negative for CD45 (Figure S1A and B), while human‐derived BMCs were positive for CD90, CD44, CD73, and CD105 (Figure S1C and D), confirming that these cells are BMSCs. To determine the optimal time window of transplantation, 2 × 106 BMSCs were intravenously injected at 3 h, 24 h, and 7 days after focal ischemia (dMCAO). Lesion volume was determined 21 days after ischemia (Figure 1A). As shown in Figure 1B, the lesion volume was significantly decreased when BMSCs were administered at 3 and 24 hr after ischemia (P < 0.01), compared with MCAO + vehicle‐treated group. No significant difference was found between BSMC‐ and vehicle‐treated groups when cells were transplanted at 7 days after stroke (P > 0.05). Consistent with histological results, neurobehavioral tests including EBST and cylinder test, the results indicated that motor deficits were significantly improved if BMSCs was administrated at 3 and 24 h, but not at 7 days, after ischemia (Figure 1C and D).

Figure 1.

Effect of optimal time window of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BMSC) transplantation on lesion volume and motor deficits after distal middle cerebral artery occlusion (dMCAO). (A) Rats first underwent dMCAO, and BMSCs at 2 × 106 were transplanted at 3 h, 24 h, and 7 days after focal ischemia. Behavioral tests were performed at 3, 6, 14, and 21 days after dMCAO. Rats were then euthanized for measurement of brain lesion. (B) Volume loss (expressed as a percentage of hemispheric volume) in vehicle‐ and BMSC‐treated rats (n = 5–6 per group). *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle‐treated (V) rat. (C) Elevated body swing test scores at different durations after dMCAO; lower scores represent more severe deficits. (D) Cylinder test scores after MCAO, higher scores represent more severe deficits. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with PBS‐treated rats.

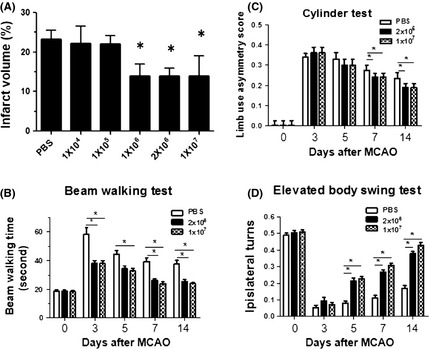

Next, we determined the appreciated number of transplanted cells after focal ischemia. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells at 1 × 104, 1 × 105, 1 × 106, 2 × 106, 1 × 107 were intravenously injected 24 h after focal ischemia, and infarct volume was determined 14 days after dMCAO. We found that infarct volume was significantly reduced after transplantation of 1 × 106, 2 × 106, and 1 × 107 BMSCs, but not when 1 × 104 and 1 × 105 BMSCs were administrated. Interestingly, no significant difference was found between groups treated with BMSCs at 1 × 106, 2 × 106, 1 × 107 (Figure 2A). Consistent with histological results, there was a significant difference in the motor performance as observed in the beam walking test, cylinder test, and EBST between vehicle‐ and 2 × 106 and 1 × 107 BMSC‐treated groups (Figure 2C and D).

Figure 2.

Effect of different doses of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BMSC) transplantation on lesion volume and motor deficits after distal middle cerebral artery occlusion (dMCAO). Rats underwent dMCAO and BMSCs at 1 × 104, 1 × 105, 1 × 106, 2 × 106, 1 × 107 were transplanted at 24 h after focal ischemia. The infarct volume was determined by H&E staining at 14 days after ischemia (A). In separate sets of experiments, BMSCs at 2 × 106 and 1 × 107 were transplanted after focal ischemia, and behavioral tests, including beam walking test (B), cylinder test (C), and EBST (D), were performed at 3, 5, 7, and 14 days after ischemia. *P < 0.05, compared with vehicle‐treated group.

BMSC Transplantation Ameliorated Poststroke Inflammation

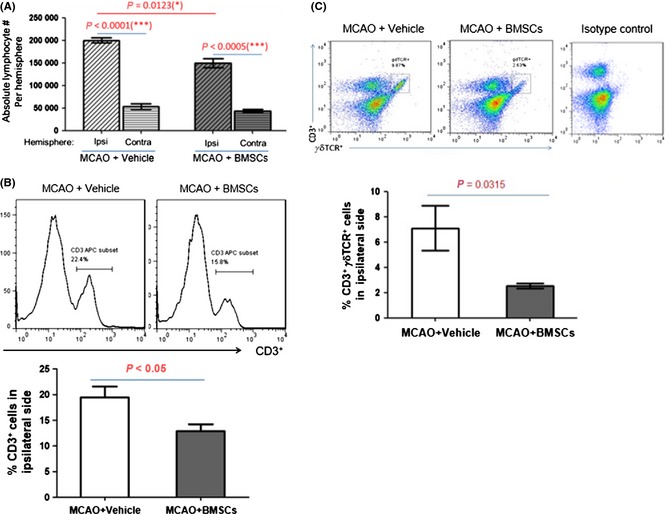

To explore the mechanisms by which BMSC administration reduced lesion size, we first determined the infiltrating lymphocytes in the ipsilateral hemisphere, as poststroke inflammation contributes to initiation and progression of brain damage. We found that BMSC transplantation significantly reduced lymphocyte numbers after stroke, providing evidence that BMSC administration indeed inhibited lymphocyte infiltration or promoted lymphocyte death (Figure 3A). Among these lymphocytes, total CD3+ T cells were profoundly reduced in comparison with the control group (Figure 3B), and so is the case for γδT cells (Figure 3C). CD3+ T cells are major T cells involved in inflammation, and γδT cells are a major source of IL‐17 production in the brain that induces neuronal damage.

Figure 3.

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BMSC) transplantation modulated T cell proportion after stroke. BMSC (2 × 106) were transplanted at 3 h after focal ischemia, and the proportion of T cells were analyzed at 72 h after focal ischemia. (A) BMSC transplantation reduced the lymphocyte number in the ipsilateral hemispheres. (B) BMSC treatment reduced the T cell proportion in the ipsilateral brains. Upper panel: representative histogram of CD3 staining. Lower panel: statistical analysis of T cell proportion. (C) BMSC implantation reduced the γδ T cell proportion in the ipsilateral hemispheres. Upper panel: representative dot plot of TCR γδ staining. Lower panel: statistical analysis of γδ T cell proportion.

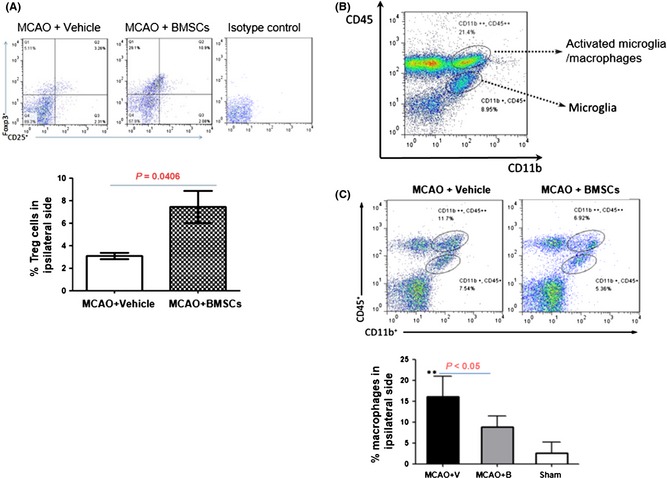

We then determined whether other pro‐inflammatory or antiinflammatory immune cells were influenced by BMSC transplantation. In current literature, Tregs are known to be the major cell type that inhibits extra immune reactions in the periphery. We found that BMSC treatment robustly increased the proportion of Tregs in the brain after stroke (Figure 4A), suggesting that neuroinflammation could be more efficiently alleviated by the antiinflammatory activities of Tregs. As M1 macrophages and microglia are involved in neuroinflammation, we looked at the changes in their levels and found a significant reduction in macrophages after BMSC treatment (Figure 4B and C).

Figure 4.

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BMSC) transplantation affected the proportions of Tregs and macrophages after stroke. BMSC (2 × 106) were transplanted at 3 h after focal ischemia and the proportion of Tregs, and macrophages were analyzed at 72 h after distal middle cerebral artery occlusion (dMCAO). (A) BMSC transplantation increased the number of Tregs in the ischemic hemispheres. Upper panel: representative dot plots of CD25 and FOXP3 staining. Lower panel: statistical analysis of Treg proportion. (B) Gating strategy for the macrophages and microglia. (C) BMSC injection reduced the macrophage proportion. Upper panel: representative dot plots of brain macrophages and microglia. Lower panel: statistical analysis of macrophage proportion.

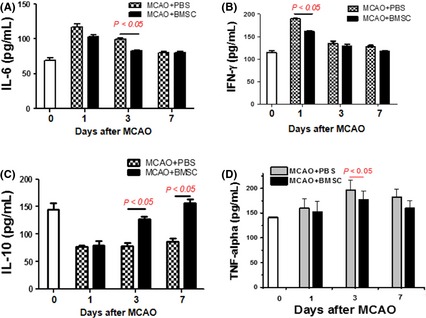

The BMSC transplantation‐induced alterations of immune cells in postischemic stroke suggest that the inflammation‐associated cytokine production could be changed in ischemic hemispheres. To confirm this hypothesis, we tested four major ischemic lesion formations or progression‐related cytokines in the ischemic regions after BMSC transplantation and found that pro‐inflammatory cytokines IL‐6, IFN‐γ, and TNF‐α in the BMSC‐implanted group were moderately decreased, compared with the control group, though at different days postischemia. Moreover, antiinflammatory cytokine IL‐10 was apparently elevated from day 3 to day 7 postischemia after transplantation (Figure 5). It was reported previously that increased IL‐10 production was able to attenuate secondary CNS injury in postischemic stroke‐induced inflammation 16. Taken together, these data provide a mechanistic clue to the protective efficacy of BMSCs in ischemic brains.

Figure 5.

Cytokine profile in the ischemic brain after bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BMSC) transplantation. Rats were treated with vehicle or BMSCs (2 × 106) at 3 hr after focal ischemia, and the ischemic hemispheres were isolated at 1, 3, and 7 days after dMCAO. IL‐6 (A), IFN‐γ (B), IL‐10 (C), TNF‐α (D) were determined by ELISA (n = 5 per time point).

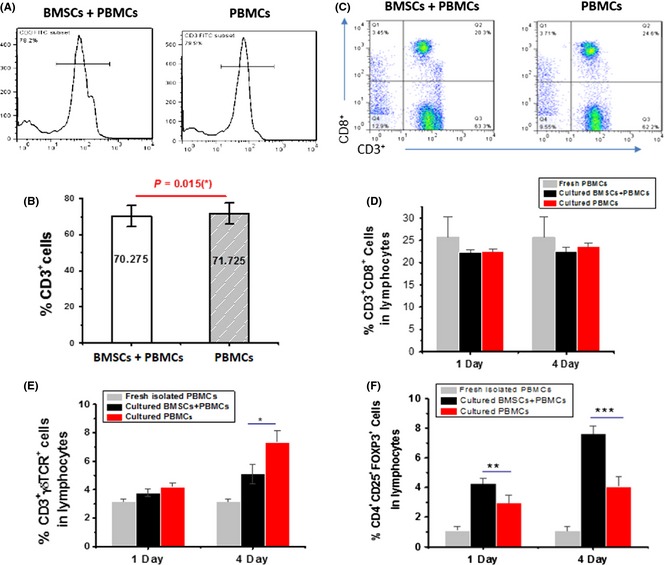

To further elucidate the mechanisms by which BMSC administration offers neuroprotection, we then investigated the presence of direct effects on lymphocyte differentiation and activation from BMSCs by co‐culturing PBMCs and BMSCs. The co‐culture of PBMCs and BMSCs reduced the proportion of total CD3+ T cells or their CD8+ subset (Figure 6A–D). In addition, at day 4 postculture, BMSCs significantly decreased the proportion of γδT cells and increased the proportion of CD4+ Tregs (Figure 6E and F), which is consistent with in vivo results (Figure 3C and 4A).

Figure 6.

Effects of co‐culture of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with BMSCs on proportions of γδT cells and Tregs. hBMSCs (1 × 105) and unstimulated PBMCs (1 × 106) were co‐cultured for 4 days, and γδT cells and Tregs were analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Representative histogram of the T cell proportion (CD3+). (B) Statistical analysis of the T cell proportion. (C) Representative dot plots of CD8+ T cells (CD3+ CD8+). (D) Statistical analysis of CD8+ T cell proportion. (E) Statistical analysis of γδT cell proportion (CD3+ γδ TCR +). (F) Statistical analysis of Treg proportion (CD4+ CD25+Foxp3+).

To detect whether co‐culture of BMSCs and PBMCs can induce similar cytokine profiles in vitro to the extent as in the ipsilateral hemisphere, we measured levels of some inflammation‐associated cytokines in the culture supernatants. Interestingly, in this co‐culture, IL‐10 and IL‐6 levels were significantly up‐regulated, and there were no significant changes in the levels of IL‐4, IFN‐γ, TNF‐α, and IL‐17 (Figure S2).

Discussion

In this study, we found that transplantation of BMSCs at different time windows or at different doses significantly affected the lesion volume and motor function recovery after focal ischemia, implying that optimal time window and appreciated cell number of transplantation are critical for stroke therapy in a clinical setting. In addition, we also studied the mechanisms and found that BMSCs were able to modulate poststroke inflammatory responses by selectively reducing deleterious and enhancing protective actions of inflammatory cells and mediators. The in vitro study confirmed that BMSCs directly interacted with PBMCs (source of a large number of T lymphocytes) and affected the proportion of Tregs and γδT cells as well as productions of pro‐ and antiinflammatory cytokines.

Systemic thrombolysis with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is the only treatment proven to improve the clinical outcome of stroke patients. Despite it being successful, only a small proportion (1–2%) of stroke patients actually benefit from tPA due to an increased risk of hemorrhage beyond 4.5 h poststroke 17. A great promise of stem cell therapy is that it will extend the therapeutic time window, thus benefiting a larger number of patients 18. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for stroke treatment has been studied by many groups. However, the best and most appropriate time window to transplant BMSCs in order to have a beneficial effect after an episode of stroke is unknown. A recent study showed that transplanting cells shortly after stroke (48 h) achieved better cell survival as compared to a later time point (6 weeks) 19. We found that when BMSCs were transplanted 3 and 24 h after ischemic stroke, better histological and behavioral outcomes were achieved as compared to a later time point (7 days). During the acute stage of ischemic stroke, release of excitotoxic neurotransmitters, free radicals as well as proinflammatory mediators may threaten transplanted cells in the acute setting, and inflammation leading to microglial activation may inhibit the growth of implanted cells 20, 21, 22. However, growth factors released from the intrinsic milieu and the host environment during the early phase can improve transplanted cell survival, differentiation, and/or integration. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation at the chronic phase may contend with the disadvantage of scar tissue formation, which may adversely affect implanted cells. Our data indicate that BMSCs can be transplanted up to 24 h after the onset of ischemic stroke. Hence, the time window for therapeutic intervention has extended compared with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which has a 4.5‐h window.

In addition to the therapeutic time window, optimal number of transplanted cells for ischemic stroke is also unclear. According to STEPS guideline, a weight‐based translation should be followed based on the optimal dose in animal studies 23. Previous studies have transplanted different cell numbers into the striatum or cortex of animals subjected to stroke and the results varied between studies, thus are difficult to be compared to each other. Our data indicate that dose regimen is an important factor in optimizing cell therapy, as low numbers of transplanted cells did not improve the functional outcome after ischemic stroke, and on the other hand, larger numbers of transplanted cells were deemed unnecessary. A recent study showed that increasing the number of implanted NSCs beyond a certain number did not cause a greater number of surviving cells. Consistently, our results showed that no significant difference was found between groups implanted with 1 × 106 to 1 × 107. Exceeding the optimal threshold of cells being transplanted may saturate the damaged striatum, result in insufficient amounts of nutrients reaching the grafted cells, and thereby progressively decrease survival rate 19. In addition, intravascular delivery may raise concerns of cells sticking together and creating microemboli. Therefore, this is not a case of “the more the merrier” as transplanting more cells does not necessarily lead to a greater number of cells that survive and/or improve functional outcome in postischemic stroke treatment.

Understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying neuroprotection of transplanted stem cells after ischemic stroke is important for clinical translation. The two most discussed repair mechanisms of stem cells‐mediated functional improvement are by far the more intriguing and hold more potential than others: (1) cellular replacement and (2) release of growth factors. The mechanisms underlying BMSC‐mediated neuroprotection remain unknown. Although BMSCs are able to differentiate into neuronal cells, studies have shown that neuronal differentiation rates are low and thus unlikely to significantly enhance outcome after stroke 24. Notably, in addition to release of growth factors to increase neurogenesis and angiogenesis 25, BMSCs may protect from ischemic injury via modulation of poststroke inflammatory response as BMSCs can modulate adaptive and innate immune responses in animal models of immune disorders 26 as well as in ischemic animal models 27, 28. For example, BMSCs could secrete TGF‐β to suppress immune propagation in the ischemic rat brain 28. Another study showed that BMSCs decrease markers of microglial activation and astrogliosis following transplantation after ischemia in vitro and in vivo 27.

Inflammatory responses postischemia are characterized by a rapid activation of brain resident immune cells (mainly microglial cells), followed by the infiltration of circulating inflammatory cells including granulocytes, T cells, and monocytes/macrophages, in the ischemic brain region 29. Our data show that BMSC transplantation significantly reduced T cell infiltration into the ischemic brain, suggesting that BMSCs alleviate postischemic inflammation via immunomodulation. In addition, macrophages/microglia are activated to release neurotoxic mediators after ischemia. Many of these mediators can in turn influence microglia morphology and activate it to release inflammatory factors that act in a paracrine and autocrine fashion 30. In the present study, BMSCs are shown to inhibit the activated microglia/macrophages in the ischemic brain.

T cell subsets have recently been implicated as modulators of secondary infarct progression and repair processes 31. Among these, Tregs are well characterized, with their ability to suppress immune and autoimmune reactions, and their important roles have been emphasized by the severe pathological conditions associated with Treg deficiency 32, 33, 34, 35, 36. A recent study has demonstrated that Tregs inhibit excessive production of pro‐inflammatory cytokines and modulate invasion and/or activation of lymphocytes and microglia in the ischemic brain to prevent secondary infarct growth 37. Tregs depletion significantly amplified secondary brain damage and deteriorated functional deficits. Tregs also antagonized ischemia‐induced TNF‐α and IFN‐γ production, which induced delayed inflammatory brain damage 37. In contrast, γδT cells have pivotal roles in the evolution of brain infarction and accompanying neurological deficits after stroke 15. Activated γδT cells infiltrated the brain after ischemia, which, in turn, produced the pro‐inflammatory cytokines IL‐17 within hours. γδT cell depletion or pharmacological inhibition of the IL‐23 or IL‐17 production ameliorated ischemic injury 15. Our PBMC transplantation in vivo data show that Tregs are significantly increased and γδT cells are reduced in the ischemic hemisphere after BMSC transplantation. Similar data were found when BMSCs were incubated with human PBMNC population. The findings indicate that BMSCs can modulate T cell subpopulations, consistent with previous findings 38, 39. However, the mechanisms underlying regulation of Tregs by BMSCs remain unclear. Cell contact, soluble mediators (prostaglandin E2, IL‐10, and TGF‐β), and indirect induction via manipulation of other antigen‐presenting cells all appear to have vital roles in the interactions between BMSCs and Tregs 40. In addition, BMSCs can reprogramme conventional T cells into Tregs 38. TGF‐β and indoleamine 2,3‐deoxygenase may play a role in BMSCs‐mediated γδT cell production 39.

Inflammatory mediators released from these pro‐inflammatory cells play a critical role in postischemic brain injury 41. The most studied cytokines related to inflammation in acute ischemic stroke are TNF‐α, IL‐1β, IL‐6, IL‐20, IL‐10, and TGF‐β. While IL‐1β and TNF‐α appear to exacerbate cerebral injury, TGF‐β and IL‐10 are touted to be neuroprotective 16, 42, 43. We found that antiinflammatory IL‐10 was increased and pro‐inflammatory TNF‐α and IL‐6 were reduced in the ischemic regions after BMSC transplantation, suggesting that BMSCs modulate cytokine secretion. To our surprise, our in vitro data showed that although IL‐10 levels were significantly up‐regulated after co‐culture, IL‐6 levels also increased. This observation may very well reflect the complex interaction between BMSCs and PBMCs. Of note, IL‐2 levels were increased after co‐culture, suggesting that this could be a cause of the increased number of Tregs as the production of IL‐2 supports Treg homeostasis and maintenance.

In conclusion, our findings show that optimal timing and most appropriate number of transplanted cells are critical for the treatment of ischemic stroke. BMSCs are able to prevent secondary injury and improve functional outcome via selectively reducing deleterious and enhancing protective actions of inflammatory cells.

Conflict of Interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflict of interests.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Rat and human BMSC identification using flow cytometry. (A) Representative histogram of CD29 and CD90 staining of rat BMSCs at passage 3. (B) Representative histogram of CD105 and CD90 staining rat BMSCs. (C) Representative histogram of CD45 and CD90 staining human BMSCs at passage 3. (D) Representative histogram of CD44 and CD73 staining of human BMSCs.

Figure S2. Effect of co‐culture of PBMCs with BMSCs on cytokine profiles. Human BMSCs were co‐cultured with human PBMCs for 1 or 4 days. IL‐10 (A), IL‐4 (B), IL‐2 (C), IL‐6 (D), TNF‐α (E), INF‐γ (F) and IL‐17 (G) levels in the supernatant were determined.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the Foundation of Zhejiang Provincial Top Key Discipline of Surgery, National Natural Science Foundation of China (81171088 and 81371396; to QCZG), International Cooperation and Exchange project of Wenzhou city technology bureau (2009A32; to BS), by Educational Commission of Zhenjiang Province, China (Z201016125; to BS), US Public Health Service Grants NS57186 and AG21980 (to K.J.).

The first three authors contributed equally to the study.

References

- 1. Kalladka D, Muir KW. Stem cell therapy in stroke: Designing clinical trials. Neurochem Int 2011;59:367–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Locatelli F, Bersano A, Ballabio E, et al. Stem cell therapy in stroke. Cell Mol Life Sci 2009;66:757–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bersano A, Ballabio E, Lanfranconi S, et al. Clinical studies in stem cells transplantation for stroke: a review. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2010;8:29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hicks A, Jolkkonen J. Challenges and possibilities of intravascular cell therapy in stroke. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2009;69:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guzman R, Choi R, Gera A, De Los Angeles A, Andres RH, Steinberg GK. Intravascular cell replacement therapy for stroke. Neurosurg Focus 2008;24:E15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bliss T, Guzman R, Daadi M, Steinberg GK. Cell transplantation therapy for stroke. Stroke 2007;38:817–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parr AM, Tator CH, Keating A. Bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stromal cells for the repair of central nervous system injury. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007;40:609–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hokari M, Kuroda S, Shichinohe H, Yano S, Hida K, Iwasaki Y. Bone marrow stromal cells protect and repair damaged neurons through multiple mechanisms. J Neurosci Res 2008;86:1024–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prockop DJ, Gregory CA, Spees JL. One strategy for cell and gene therapy: Harnessing the power of adult stem cells to repair tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100(Suppl 1):11917–11923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nawashiro H, Martin D, Hallenbeck JM. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor and amelioration of brain infarction in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1997;17:229–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Won SJ, Xie L, Kim SH, et al. Influence of age on the response to fibroblast growth factor‐2 treatment in a rat model of stroke. Brain Res 2006;1123:237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Swanson RA, Morton MT, Tsao‐Wu G, Savalos RA, Davidson C, Sharp FR. A semiautomated method for measuring brain infarct volume. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1990;10:290–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sun F, Xie L, Mao X, Hill J, Greenberg DA, Jin K. Effect of a contralateral lesion on neurological recovery from stroke in rats. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2012;30:491–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jin K, Mao XO, Batteur S, Sun Y, Greenberg DA. Induction of neuronal markers in bone marrow cells: Differential effects of growth factors and patterns of intracellular expression. Exp Neurol 2003;184:78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shichita T, Sugiyama Y, Ooboshi H, et al. Pivotal role of cerebral interleukin‐17‐producing gammadelta T cells in the delayed phase of ischemic brain injury. Nat Med 2009;15:946–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frenkel D, Huang Z, Maron R, Koldzic DN, Moskowitz MA, Weiner HL. Neuroprotection by IL‐10‐producing MOG CD4+ T cells following ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci 2005;233:125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gonzalez RG. Imaging‐guided acute ischemic stroke therapy: From “time is brain” to “physiology is brain”. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27:728–735. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bliss TM, Andres RH, Steinberg GK. Optimizing the success of cell transplantation therapy for stroke. Neurobiol Dis 2010;37:275–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Darsalia V, Allison SJ, Cusulin C, et al. Cell number and timing of transplantation determine survival of human neural stem cell grafts in stroke‐damaged rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011;31:235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nishino H, Borlongan CV. Restoration of function by neural transplantation in the ischemic brain. Prog Brain Res 2000;127:461–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arvidsson A, Collin T, Kirik D, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Neuronal replacement from endogenous precursors in the adult brain after stroke. Nat Med 2002;8:963–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jin K, Sun Y, Xie L, et al. Directed migration of neuronal precursors into the ischemic cerebral cortex and striatum. Mol Cell Neurosci 2003;24:171–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Savitz SI, Chopp M, Deans R, Carmichael ST, Phinney D, Wechsler L. Stem Cell Therapy as an Emerging Paradigm for Stroke (STEPS) II. Stroke 2011;42:825–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. England T, Martin P, Bath PM. Stem cells for enhancing recovery after stroke: A review. Int J Stroke 2009;4:101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wei L, Fraser JL, Lu ZY, Hu X, Yu SP. Transplantation of hypoxia preconditioned bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells enhances angiogenesis and neurogenesis after cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurobiol Dis 2012;46:635–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Uccelli A, Laroni A, Freedman MS. Mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of multiple sclerosis and other neurological diseases. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McGuckin CP, Jurga M, Miller AM, et al. Ischemic brain injury: A consortium analysis of key factors involved in mesenchymal stem cell‐mediated inflammatory reduction. Arch Biochem Biophys 2013;534:88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yoo SW, Chang DY, Lee HS, et al. Immune following suppression mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in the ischemic brain is mediated by TGF‐beta. Neurobiol Dis 2013;58:249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gelderblom M, Leypoldt F, Steinbach K, et al. Temporal and spatial dynamics of cerebral immune cell accumulation in stroke. Stroke 2009;40:1849–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee SC, Liu W, Dickson DW, Brosnan CF, Berman JW. Cytokine production by human fetal microglia and astrocytes. Differential induction by lipopolysaccharide and IL‐1 beta. J Immunol 1993;150:2659–2667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moskowitz MA, Lo EH, Iadecola C. The science of stroke: Mechanisms in search of treatments. Neuron 2010;67:181–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gu L, Xiong X, Zhang H, Xu B, Steinberg GK, Zhao H. Distinctive effects of T cell subsets in neuronal injury induced by cocultured splenocytes in vitro and by in vivo stroke in mice. Stroke 2012;43:1941–1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Planas AM, Chamorro A. Regulatory T cells protect the brain after stroke. Nat Med 2009;15:138–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kleinschnitz C, Kraft P, Dreykluft A, et al. Regulatory T cells are strong promoters of acute ischemic stroke in mice by inducing dysfunction of the cerebral microvasculature. Blood 2012;121:679–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ren X, Akiyoshi K, Vandenbark AA, Hurn PD, Offner H. CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T‐cells in cerebral ischemic stroke. Metab Brain Dis 2011;26:87–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Baruch K, Ron‐Harel N, Gal H, et al. CNS‐specific immunity at the choroid plexus shifts toward destructive Th2 inflammation in brain aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:2264–2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liesz A, Suri‐Payer E, Veltkamp C, et al. Regulatory T cells are key cerebroprotective immunomodulators in acute experimental stroke. Nat Med 2009;15:192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Le Blanc K, Mougiakakos D. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2012;12:383–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Prigione I, Benvenuto F, Bocca P, Battistini L, Uccelli A, Pistoia V. Reciprocal interactions between human mesenchymal stem cells and gammadelta T cells or invariant natural killer T cells. Stem Cells 2009;27:693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Burr SP, Dazzi F, Garden OA. Mesenchymal stromal cells and regulatory T cells: The Yin and Yang of peripheral tolerance? Immunol Cell Biol 2013;91:12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tureyen K, Brooks N, Bowen K, Svaren J, Vemuganti R. Transcription factor early growth response‐1 induction mediates inflammatory gene expression and brain damage following transient focal ischemia. J Neurochem 2008;105:1313–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lakhan SE, Kirchgessner A, Hofer M. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: Therapeutic approaches. J Transl Med 2009;7:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Strle K, Zhou JH, Shen WH, et al. Interleukin‐10 in the brain. Crit Rev Immunol 2001;21:427–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Rat and human BMSC identification using flow cytometry. (A) Representative histogram of CD29 and CD90 staining of rat BMSCs at passage 3. (B) Representative histogram of CD105 and CD90 staining rat BMSCs. (C) Representative histogram of CD45 and CD90 staining human BMSCs at passage 3. (D) Representative histogram of CD44 and CD73 staining of human BMSCs.

Figure S2. Effect of co‐culture of PBMCs with BMSCs on cytokine profiles. Human BMSCs were co‐cultured with human PBMCs for 1 or 4 days. IL‐10 (A), IL‐4 (B), IL‐2 (C), IL‐6 (D), TNF‐α (E), INF‐γ (F) and IL‐17 (G) levels in the supernatant were determined.