Summary

Aims

To investigate whether Meserine, a novel phenylcarbamate derivative of (−)‐meptazinol, possesses beneficial activities against cholinergic deficiency and amyloidogenesis, the two major pathological characteristics of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Methods

Ellman's assay and Morris water maze were used to detect acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity and evaluate spatial learning and memory ability, respectively. Both high content screening and Western blotting were carried out to detect β‐amyloid precursor protein (APP), while RT‐PCR and ELISA were conducted to detect APP‐mRNA and β‐amyloid peptide (Aβ).

Results

In scopolamine‐induced dementia mice, Meserine (1 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly ameliorated spatial learning and memory deficits, which was consistent with its in vitro inhibitory ability against AChE (recombinant human AChE, IC50 = 274 ± 49 nM). Furthermore, Meserine (7.5 mg/kg) injected intraperitoneally once daily for 3 weeks lowered APP level by 28% and Aβ42 level by 42% in APP/PS1 transgenic mouse cerebrum. This APP modulation action might be posttranscriptional, as Meserine reduced APP by about 30% in SH‐SY5Y‐APP695 cells but did not alter APP‐mRNA level. And both APP and Aβ42 lowering action of Meserine maintained longer than that of rivastigmine.

Conclusion

Meserine executes dual actions against cholinergic deficiency and amyloidogenesis and provides a promising lead compound for symptomatic and modifying therapy of AD.

Keywords: AChE inhibitor, Alzheimer's disease, Meserine, β‐amyloid peptide, β‐amyloid precursor protein

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by progressive decline in cognition and behavior with decreased cholinergic transmission, extracellular senile plaques (SPs), and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in cerebrum 1. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) are widely used in clinical as a symptomatic strategy 2. Recently, improved therapeutics based on AChEIs is being developed to acquire additional “disease‐modifying” function 3.

The core component of SP, β‐amyloid peptide (Aβ), is a definite pathogenic factor for AD; thus, numerous researches are carried out focusing on this target 4, 5, 6, among which regulating β‐amyloid precursor protein (APP) expression is an alternative approach. In our previous work, bis‐(−)‐nor‐meptazinols 7, 8, 9 and their derivatives 10 were characterized as dual binding site AChEIs with anti‐Aβ‐aggregation and/or metal‐complexing properties. To explore the structure modification of (−)‐meptazinol, an opioid analgesic with low addiction liability, which has moderate AChE inhibitory activity, we added a phenylcarbamate group on its benzene ring and obtained a novel derivative named Meserine (Code number XQ528, MW 352.46, structural formula as Figure 1A).

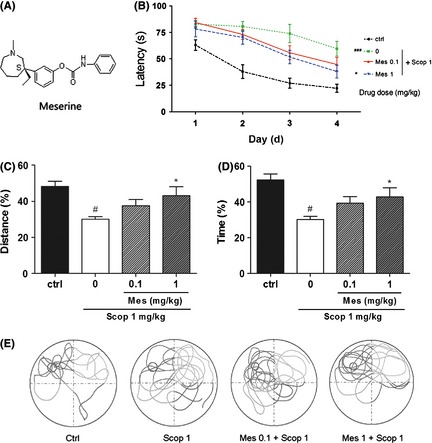

Figure 1.

Meserine (Mes) ameliorates spatial learning and memory deficits in scopolamine (Scop)‐induced mouse model. (A) Chemical structure of Meserine, (B) Escape latency, (C) Distance percent in the target quadrant, (D) Time percent in the target quadrant, (E) Representative swimming paths in probe trials. Scopolamine (1 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered 20 min before the test once a day for all 5 days, and Meserine (0.1 and 1 mg/kg, i.p.) was pretreated 60 min before scopolamine as well. n = 10, #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001, compared with control group; *P < 0.05, compared with scopolamine‐treated group.

In this study, we tried to investigate whether Meserine possesses antiamyloidogenic property as well as AChE inhibitory activity for the additional phenylcarbamate moiety.

Methods

Drugs and Chemicals

Meserine hydrochloride was synthesized in our laboratory (98.4% pure); rivastigmine hydrochloride was available from Sunve (Shanghai, China) Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Scopolamine, acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCh), 5,5′‐dithio‐bis‐2‐nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB), and recombinant human AChE (rHuAChE) were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). DMEM/F12 (1:1, + l‐glutamine, + 15 mM HEPES) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). All other reagents were obtained from commercial sources.

Animals and Drug Administration

Kunming mice (20–30 g) were purchased from experimental animal center of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine and were kept on a 12‐h light cycle from 06:00 to 18:00 with free access to food and water.

The APP/PS1 transgenic mice were introduced from Jackson Laboratory (No. 003378, APPSwe+PS1A246E) and then bred and identified as the instruction provided on the website of Jackson Laboratory. Eight‐month‐old double transgenic mice were injected with Meserine (2.5, 7.5, and 15 mg/kg, respectively) or rivastigmine (2 mg/kg) intraperitoneally once per day for 3 weeks, those injected with equivalent saline were regarded as control. Age‐matched wild‐type mice were also injected with equivalent saline.

All studies were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the National Institutes of Health.

Cell Culture and Treatment

SH‐SY5Y‐APP695 cell line 11 was kindly provided by Professor Shengdi Chen (Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China).

SH‐SY5Y‐APP695 cells of 5 × 104/well were plated in 200 μL culture medium (DMEM/F12, 10% FBS, 300 μg/mL G418, 100 U/mL penicillin + 100 μg/mL streptomycin) and incubated for 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The compounds (Meserine and rivastigmine) dissolved in culture medium were applied to the cells and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for an interval (as shown in the figures).

Determination of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activity In Vitro

Acetylcholinesterase activity was determined according to a modified Ellman's method as described in our published paper 12. Briefly, rHuAChE was preincubated with Meserine or rivastigmine for 20 min at 37°C in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), containing 0.25 mM DTNB. The substrate, 0.5 mM ATCh, was then quickly added. After incubation at 37°C for 6 min, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 100 μL eserine (1 mM), and the color production was measured spectrophotometrically at 412 nm.

The percent inhibition of the enzyme reaction in the presence of the inhibitors was determined by comparison with control, and the average inhibition rate for each concentration was calculated to deduce the IC50 value (the inhibitor concentration required for 50% inhibition of AChE activity) for each test drug.

In Vivo Assessment of Spatial Learning and Memory Ability

The ability of Meserine to reverse scopolamine‐induced spatial learning and memory deficits was evaluated in Morris water maze as previously described 12. Briefly, a large black circular pool (120 cm diameter) was filled with water to a depth of 25 cm (maintained at 25 ± 1.0°C). The pool was divided into four equal quadrants, and a black platform (9 cm diameter) was submerged ~ 1 cm below the surface of water in the center of one quadrant (target quadrant). The platform was made invisible to the mice and remained in one location for the entire test. A high‐resolution exview HAD camera was suspended over the center of the pool, its images being monitored by a video‐tracking system (Morris Water Maze Video Analysis System [DigBeh‐MM], Shanghai Jiliang Software Technology Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China).

The Kunming mice were given four trials per day for four consecutive days, with a 30‐s intertrial interval. Each day, a trial was initiated by placing each mouse in the water facing the pool wall in one of the four quadrants. The daily order of entry into individual quadrants was randomized so that all four quadrants were used once every day. The mouse was allowed 90 s to locate the hidden platform. When successful, it was allowed a 30‐s rest period on the platform, and the time spent in locating the platform was recorded as escape latency. If unsuccessful within the allotted time period, the mouse was assigned a latency of 90 s and then physically placed on the platform and also allowed a 30‐s rest period. The escape latency and swimming distance as well as swimming paths were recorded by the video‐tracking system, and the first one was used as a parameter for spatial learning ability.

On day 5, each mouse was subjected to a 60‐s probe trial twice in which the hidden platform had been removed completely. The mouse was placed in the pool to swim for 60 s from the opposite and side position of the target quadrant, respectively, with a 30‐s intertrial interval. Time spent in the target quadrant and the proportions of swim distance in the target quadrant were determined by the analysis system, as well as total distance. Time percent and distance percent in the target quadrant were calculated, which were taken as measurement of spatial memory.

Scopolamine (1 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered 20 min before the test once a day for all 5 days, and Meserine (0.1 and 1 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally 60 min before scopolamine as well.

Preparation of Mouse Brain Extracts

The APP/PS1 transgenic mouse brain cortices were homogenized in 9‐fold (w/v) extraction buffer (RIPA, Shanghai Biocolor BioScience & Technology Company, Shanghai, China) and incubated on ice for 30 min. The homogenates were then centrifuged at 13,500 g for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was taken for the further detection. The protein concentration in each sample was estimated according to BCA protein assay (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL, USA).

Preparation of Cell Lysate

The SH‐SY5Y‐APP695 cells were lysed with ice‐cold SDS buffer (2% SDS, 30 mM Tris‐HCl pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 2 mM EDTA) and incubated on ice for 30 min. The lysate was centrifuged at 13,500 g for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was taken for the detection of APP by Western blotting.

Quantification of APP by Western Blotting

The protein samples were boiled for 5 min at 100°C, separated by 8% SDS‐PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore, Boston, MA, USA), and probed with 22C11 antibody (1:200, Millipore) to APP or mouse anti‐ β‐actin monoclonal antibody (1:2000, ZSGB‐BIO, Beijing, China) as control at 4°C overnight. The membranes were incubated with the proper horseradish‐peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000, ZSGB‐BIO) at room temperature for 1 h. The immunoblots were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Pierce Chemical). Relative levels of protein were quantitated by optical density analysis. To avoid interassay variations, values were normalized to the control value in each experiment.

Quantification of APP by High Content Screening

The SH‐SY5Y‐APP695 cells were fixed and permeabilized. Mouse anti‐APP monoclonal antibody N‐terminus (1:200, 22C11, Millipore) and Goat anti‐mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 (1:100, Thermo Scientific Cellomics, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) were used as primary antibody and second antibody to detect APP, while Hoechst dye (1:2000, Thermo Scientific Cellomics) was used to stain nucleus simultaneously. KineticScan HCS System (Thermo Scientific Cellomics) was employed to automatically find, focus, image, and analyze the cells on double fluorescence channel guided by Target Activation Bioapplication. Fluorescence Unit of APP versus that of nucleus was used to evaluate the expression of APP, to balance the background.

Quantification of Aβ40/Aβ42 by ELISA

The transgenic mouse brain extracts (or SH‐SY5Y‐APP695 cell culture supernatant) were collected and added of phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride (PMSF, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) with the final concentration of 0.1%. The concentration of Aβ40/Aβ42 of the sample was measured by Human Amyloid‐β (40/42) Assay Kit (IBL, Gunma, Japan) and calculated according to the standard line.

Quantification of APP‐mRNA by RT‐PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the SH‐SY5Y‐APP695 cells using Total DNA/RNA/Protein Kit (OMEGA Bio‐Tek, Norcross, GA, USA). M‐MLV First‐Strand Kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies) was used to synthesize first‐strand cDNA from samples with an equal amount of RNA. Real‐time PCR was carried out using SYBR Premix Ex Taq Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) with Roter‐Gene 3000 (CORBETT, Sydney, Australia). Nucleotide sequences of the primers are shown in Table 1. APP‐mRNA levels were normalized to the levels of β‐actin. Specificity of the produced amplification product was confirmed by examination of dissociation reaction plots. A distinct single peak indicated that a single DNA sequence was amplified during PCR. Each sample was tested in triplicate, and threshold cycle (CT) values were averaged from each reaction. The ΔΔCT method of relative quantification was used to determine the fold change in expression. This was carried out by first normalizing the resulting CT values of the target mRNAs to the CT values of the internal control β‐actin in the same samples (ΔCT = CTTarget−CTβ‐actin). It was further normalized with the control (ΔΔCT = ΔCT−CTControl). The fold change in expression was then obtained (2−ΔΔCT). Results obtained from at least three independent experiments were used to calculate the mean ± SEM.

Table 1.

Sequences of the primers

| Name | Sequences (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| β‐actin forward primer | CTGGAACGGTGAAGGTGACA |

| β‐actin reverse primer | AAGGGACTTCCTGTAACAATGCA |

| APP forward primer | GGCTCTAGACCACCATGCTGCCCGGTTTGGCACTGCT |

| APP reverse primer | CCCAAGCTTCCGCTAGTTCTGCATCTGCTCAAAGA |

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance of the observed differences was assessed by one‐way analysis of variance (anova). The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activity In Vitro

In vitro, Meserine inhibited rHuAChE activity in a concentration‐dependent manner with IC50 value of 274 ± 49 nM, while that of rivastigmine was 6.46 ± 1.81 μM.

Ameliorating Spatial Learning and Memory Ability

During the first four training days, the escape latency for mice to reach the platform gradually decreased as the training kept on day by day. As shown in Figure 1B, control mice found the platform more quickly than other groups, and scopolamine 1 mg/kg, i.p. could induce spatial learning and memory deficits appropriately. Meserine (1 mg/kg, i.p.) pretreatment alleviated the deficits induced by scopolamine.

On day 5, Meserine 1 mg/kg, i.p. pretreatment significantly increased scopolamine‐induced reduction in distance percent in the target quadrant and in time percent as well (P < 0.05, compared with scopolamine‐treated group) (Figure 1C,D). The representative swimming path for each tested group is presented in Figure 1E. Compared with the control group, scopolamine‐treated mice showed confused paths, which were improved by Meserine.

Antiamyloidogenic Properties In Vivo

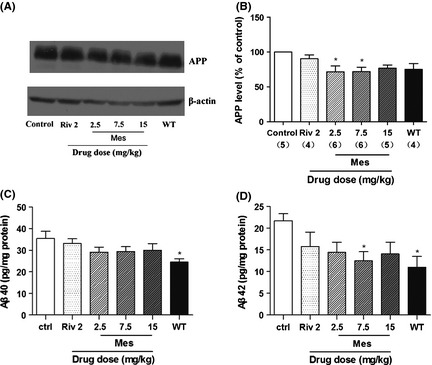

In the APP/PS1 transgenic mouse cerebrums, the APP levels were lowered significantly by administration of Meserine with doses of 2.5 and 7.5 mg/kg (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Effects of Meserine on APP and Aβ levels in APP/PS1 transgenic mouse cerebrums. Meserine (Mes, 2.5, 7.5, and 15 mg/kg) and rivastigmine (Riv, 2 mg/kg) were administrated intraperitoneally once per day for 3 weeks. Control mice and age‐matched wild‐type mice were injected with equivalent saline. (A) Immunoblots of APP and β‐actin; (B) Relative quantification by optical density analysis. Mouse brain Aβ40 (C) and Aβ42 (D) were detected by ELISA with Human Amyloid‐β (40/42) Assay Kit (IBL, Japan). The number in the parentheses represents the value of n in each group. *P < 0.05 significant difference from control group.

As shown in Figure 2C,D, compared with age‐matched wild‐type mice, APP/PS1 transgenic mice have elevated Aβ levels in their cerebrums, both Aβ40 and Aβ42, indicating a notable amyloidogenic change of this model. Meserine at the dose of 7.5 mg/kg (i.p.) lowered the elevated Aβ42 level by 42%, but did not affect the Aβ40 level significantly.

Lowering the Level of APP but not APP‐mRNA In Vitro

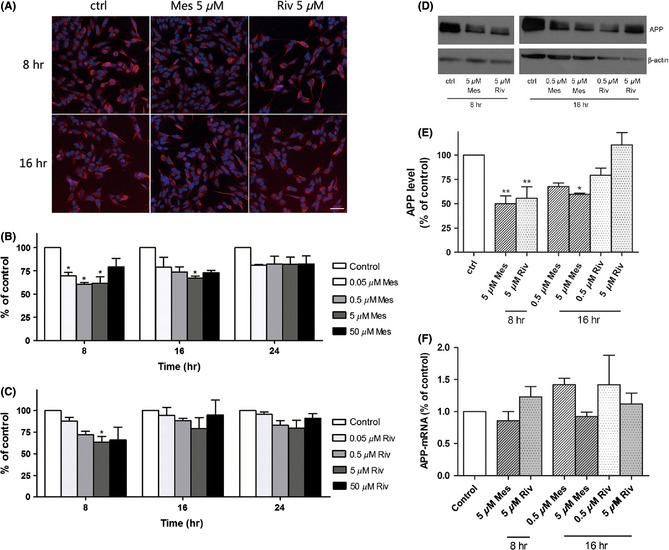

As shown in Figure 3A, APP was marked in red, while nucleus was stained in blue. Relative quantification of mean fluorescence intensity showed that Meserine could lower APP levels after 8‐h or 16‐h incubation with SH‐SY5Y‐APP695 cells (Figure 3B), but the action did not sustain longer. In contrast, the effect of rivastigmine on APP expression just lasted for 8 h (Figure 3C). These results were confirmed by Western blotting (Figure 3D,E). Moreover, APP gene expression measured by RT‐PCR was not affected by both Meserine and rivastigmine (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Effects of Meserine (Mes) and rivastigmine (Riv) on APP and APP‐mRNA levels in SH‐SY5Y‐APP695 cells were incubated with the compounds (Meserine or rivastigmine) at 37°C in 5% CO2 for an interval (as shown in the figure). High content screening and western blotting were used to detect β‐amyloid precursor protein (APP), while RT‐PCR was conducted to detect APP‐mRNA. (A) Localization of APP protein (red), scale bar = 20 μm, (B) and (C) Quantitation of mean fluorescence intensity, (D) Immunoblots of APP and β‐actin, (E) Relative quantification by optical density analysis, (F) Relative APP‐mRNA levels. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs. control.

Decreasing Aβ42 but not Aβ40 In Vitro

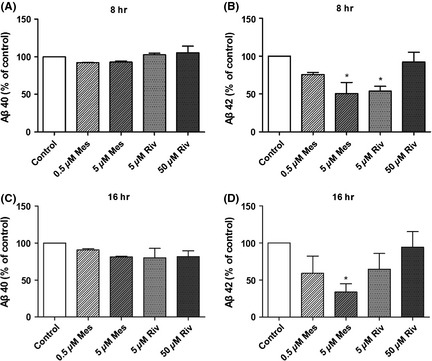

The results showed 5 μM Meserine could lower the level of Aβ42 in SH‐SY5Y‐APP695 cell culture supernatant significantly either at 8 h or at 16 h after incubation. Under the same condition, rivastigmine reduced Aβ42 at 8 h but not at 16 h after incubation (Figure 4B,D). Aβ40 level was not significantly altered by both two compounds (Figure 4A,C).

Figure 4.

Effects of Meserine (Mes) and rivastigmine (Riv) on Aβ levels in SH‐SY5Y‐βAPP 695 cells were incubated with the compounds (Meserine or rivastigmine) at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 8 h or 16 h. ELISA (Human Amyloid‐β 40/42 Assay Kit, IBL, Gunma, Japan) was conducted to detect Aβ40/Aβ42 in cell culture supernatant. Aβ40 levels after incubation with Meserine and rivastigmine for 8 h (A) or 16 h (C); Aβ42 levels after incubation with Meserine and rivastigmine for 8 h (B) or 16 h (D). *P < 0.05, vs. control.

Discussion

The therapeutics toward Alzheimer's disease develops slowly as its complex pathophysiology. In recent years, a novel therapeutic concept “one molecule‐multiple targets” is rising instead of the traditional “one molecule‐one target” one. AChE seems to be a critical node within the complex pathological network of AD, with classical and nonclassical activities involved in the late (cholinergic deficit) and early (Aβ aggregation) phases of the disease. Rationally designed multitarget‐directed ligands (MTDLs), for example dual inhibitors of Aβ aggregation and AChE, are considered to be the preferable approaches, which possess both palliative and disease‐modifying properties 9, 13, 14, 15. The overproduction of Aβ is regarded as early critical factors of AD. Therefore, we designed a novel AChEI named Meserine, which is a phenylcarbamate derivative of (−)‐meptazinol hypothesized to have additional antiamyloidogenic activity to efficiently modify the natural course of AD.

In this work, Meserine was demonstrated to be a more potent AChE inhibitor than rivastigmine (24‐fold for rHuAChE) and significantly ameliorate scopolamine‐induced learning and memory impairment in mice as measured by decreases in the time and distance percentages in probe trials.

Furthermore, Meserine also showed APP‐regulating function as it reduces APP and Aβ42 levels in vitro and in vivo. Some evidences have shown that APP may play an intrinsic central role in the pathogenesis of AD independent on Aβ 16, 17, 18, 19, and also increased expression of APP and generation of Aβs play a central role in the amyloidogenic process in AD 20, 21, 22, 23. Meserine markedly suppressed APP protein levels, thereby reducing the possibility of generation of the toxic Aβs. This APP modulation action might be posttranscriptional, as Meserine reduced APP but did not alter APP‐mRNA level. The mechanism underlying these effects may involve both cholinergic and noncholinergic actions regulating APP synthesis and processing, similar to that of another AChE inhibitor, phenserine 24, 25. Other actions and mechanisms of Meserine such as neuroprotection and antiinflammation deserve further investigations 25, 26.

In conclusion, Meserine executes dual actions against cholinergic deficiency and amyloidogenesis and may provide a promising lead compound for symptomatic and modifying therapy of AD.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 30801393, 30801435, and 30973509), National Basic Research Program of China (2010CB529806), and National Innovative Drug Development Project (2009ZX09103‐077 and 2009ZX09301‐011) for financial supports.

The first two authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1. Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011;3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anand P, Singh B. A review on cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease. Arch Pharm Res 2013;36:375–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leon R, Garcia AG, Marco‐Contelles J. Recent advances in the multitarget‐directed ligands approach for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Med Res Rev 2011;33:139–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Singh S, Kushwah AS, Singh R, Farswan M, Kaur R. Current therapeutic strategy in Alzheimer's disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2012;16:1651–1664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Savonenko AV, Melnikova T, Hiatt A, et al. Alzheimer's therapeutics: translation of preclinical science to clinical drug development. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011;37:261–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khairallah MI, Kassem LA. Alzheimer's disease: current status of etiopathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Pak J Biol Sci 2011;14:257–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu T, Xia Z, Zhang WW, et al. Bis(9)‐(−)‐nor‐meptazinol as a novel dual‐binding AChEI potently ameliorates scopolamine‐induced cognitive deficits in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2013;104:138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paz A, Xie Q, Greenblatt HM, et al. The crystal structure of a complex of acetylcholinesterase with a bis‐(−)‐nor‐meptazinol derivative reveals disruption of the catalytic triad. J Med Chem 2009;52:2543–2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xie Q, Wang H, Xia Z, et al. Bis‐(−)‐nor‐meptazinols as novel nanomolar cholinesterase inhibitors with high inhibitory potency on amyloid‐beta aggregation. J Med Chem 2008;51:2027–2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zheng W, Li J, Qiu Z, et al. Novel bis‐(−)‐nor‐meptazinol derivatives act as dual binding site AChE inhibitors with metal‐complexing property. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2012;264:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang HQ, Sun ZK, Zhao YX, et al. PMS777, a new cholinesterase inhibitor with anti‐platelet activated factor activity, regulates amyloid precursor protein processing in vitro. Neurochem Res 2009;34:528–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miezan Ezoulin JM, Shao BY, Xia Z, et al. Novel piperazine derivative PMS1339 exhibits tri‐functional properties and cognitive improvement in mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2009;12:1409–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cavalli A, Bolognesi ML, Minarini A, et al. Multi‐target‐directed ligands to combat neurodegenerative diseases. J Med Chem 2008;51:347–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bolognesi ML, Rosini M, Andrisano V, et al. MTDL design strategy in the context of Alzheimer's disease: From lipocrine to memoquin and beyond. Curr Pharm Des 2009;15:601–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bajda M, Guzior N, Ignasik M, Malawska B. Multi‐target‐directed ligands in Alzheimer's disease treatment. Curr Med Chem 2011;18:4949–4975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simón A, Schiapparelli L, Salazar‐Colocho P, et al. Overexpression of wild‐type human APP in mice causes cognitive deficits and pathological features unrelated to Abeta levels. Neurobiol Dis 2009;33:369–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neve RL, McPhie DL, Chen Y. Alzheimer's disease: A dysfunction of the amyloid precursor protein(1). Brain Res 2000;886:54–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yamaguchi F, Richards SJ, Beyreuther K, et al. Transgenic mice for the amyloid precursor protein 695 isoform have impaired spatial memory. NeuroReport 1991;2:781–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gruart A, Lopez‐Ramos JC, Munoz MD, Delgado‐Garcia JM. Aged wild‐type and APP, PS1, and APP + PS1 mice present similar deficits in associative learning and synaptic plasticity independent of amyloid load. Neurobiol Dis 2008;30:439–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sleegers K, Brouwers N, Gijselinck I, et al. APP duplication is sufficient to cause early onset Alzheimer's dementia with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain 2006;129:2977–2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brouwers N, Sleegers K, Engelborghs S, et al. Genetic risk and transcriptional variability of amyloid precursor protein in Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2006;129:2984–2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Theuns J, Brouwers N, Engelborghs S, et al. Promoter mutations that increase amyloid precursor‐protein expression are associated with Alzheimer disease. Am J Hum Genet 2006;78:936–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsui T, Ingelsson M, Fukumoto H, et al. Expression of APP pathway mRNAs and proteins in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res 2007;1161:116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yogev‐Falach M, Bar‐Am O, Amit T, Weinreb O, Youdim MB. A multifunctional, neuroprotective drug, ladostigil (TV3326), regulates holo‐APP translation and processing. FASEB J 2006;20:2177–2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lilja AM, Luo Y, Yu QS, et al. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective actions of (−)‐ and (+)‐phenserine, candidate drugs for Alzheimer's disease. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e54887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Butchart J, Holmes C. Systemic and central immunity in Alzheimer's disease: Therapeutic implications. CNS Neurosci Ther 2012;18:64–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]