Summary

Aims

Population aging is burdening the society globally, and the evaluation of functional networks is the key toward understanding cognitive changes in normal aging. However, the effect of age on default mode subnetworks has not been documented well, and age‐related changes in many resting‐state networks remain debatable. The purpose of this study was to propose more precise results for these issues using a large sample size.

Methods

We used group‐level meta‐ICA analysis and dual regression approach for identifying resting‐state networks from functional magnetic resonance imaging data of 430 healthy elderly participants. Partial correlation was used to observe age‐related correlations within and between resting‐state networks.

Results

In the default mode network, only the ventral subnetwork negatively correlated with age. Age‐related decrease in functional connectivity was also noted in the auditory, right frontoparietal, sensorimotor, and visual medial networks. Further, some age‐related increases and decreases were observed for between‐network correlations.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that only the ventral default mode subnetwork had age‐related decline in functional connectivity and several reverse patterns of resting‐state networks for network development. Understanding age‐related network changes may provide solutions for the impact of population aging and diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: Aging, Default mode subnetwork, Resting‐state network

Introduction

Population aging is a global phenomenon and is currently in an unprecedented and enduring condition, resulting in considerable implications for many dimensions of human life and markedly burdening a wide range of economic, political, and social conditions 1. Aging leads to a large number of physical, biological, chemical, and psychological changes, steadily declining many cognitive processes across the lifespan. The introduction of functional imaging techniques reveals that age‐related cognitive impairment is associated with alterations in brain functional connectivity 2, 3, 4, wherein many important findings from the evaluation of resting‐state networks (RSN) 5, 6 that had strongly functional connected neural networks, as revealed by resting‐state functional magnetic resonance imaging 7. Exploring age‐related changes in RSN is a key toward understanding the cognitive trajectory of aging and further serves as a physiological standard for overcoming clinical challenges occurring while diagnosing neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Alzheimer's disease (AD) 8.

Age‐related decline in functional connectivity is observed both within and between several RSNs 5, 6, the most consistently identified of which is the default mode network (DMN) 6, 9, 10. DMN is a set of brain regions with intrinsic activities originally found as a pattern of decreased activity at task but increased activity at rest 11, 12. Neuroscientists suspect that some neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD and depression, may be associated with DMN functional impairment 13. Moreover, recent studies proposed that DMN is separable and the subnetworks are responsible for distinct cognitive functions 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22. The different effects of age on these cognitive functions are supported by behavioral science but with some controversy 19, 23, 24 and evidence from RSN is lacking. Clarifying the vulnerability of these subnetworks to aging can elucidate a functional basis for age‐related changes of these cognitive functions.

In addition to DMN, some other RSNs and even between‐network connections are influenced by aging; such changes may be the neural basis of cognitive decline in the elderly 5, 6. A previous study revealed that age‐related decrease in connectivity exists in salience and visual networks and that the salience network change is associated with impaired frontal and parietal functions. Age‐related decrease in connectivity is also present between DMN and visual network, suggesting attenuation of the hub function of DMN 6. Another study reveals that age‐related decrease in connectivity is found in the high‐function networks, while the primary function networks are preserved 5. Compared with young adults, the elderly have a reverse process of reduced modularity of RSNs, signifying increased internetwork connections and decreased intranetwork connections that were probably related to cognitive decline 5. Furthermore, a previous study has found decreased connectivity in the dorsal attention network, probably underlying the impairment in sustained attention, and increased connectivity in the somatosensory cortex, cerebellum, amygdala, and thalamus, which are relatively less vulnerable networks or regions 25. Functional connectivity also decreases in the motor network, possibly related to an impaired motor ability 26. RSNs involving frontal and parietal areas have been reported to decrease in functional connectivity with age 9. Age‐associated modifications within and between many RSNs are critical in the comprehension of cognitive aging; however, previous results have been quite inconsistent 5, 6, 9, 25. A large sample size can contribute toward more precise results and detect small differences, delineating a closer and more complete picture of the cognitive conditions 27.

The degree to which age affects the relevant cognitive functions of default mode subnetworks seems to be different. Therefore, we hypothesize that the effect of age on the functional connectivity of these subnetworks would be different, and functional evaluation can serve as complementary evidence on age‐related cognitive changes in behavioral science. Further, the importance of within‐ and between‐network changes on other RSNs in cognitive aging is highlighted. Here, we used a large sample size to acquire more precise results and better understand cognitive changes in aging.

Methods

Participants

The participants were recruited from the I‐Lan Longitudinal Aging Study, a community‐based aging cohort study in I‐Lan, Taiwan, aiming to investigate the association between normal aging, cognitive decline, and brain imaging markers 28. In brief, 1008 community‐dwelling adults aged 50 years or older from the town of Yuanshan were randomized through household registrations of the I‐Lan County Government and were invited to participate in the study via mail or telephone. This study randomly sampled half (n = 504) of the cohort subjects with the following inclusion criteria: (1) without a plan to move out in the near future and (2) age equal or older than 50 years old. Any participant with the following conditions was excluded: (1) unable to communicate and complete an interview, (2) unable to complete a simple motor task within a reasonable period of time because of functional disability, (3) suffering from any major illness with limited life expectancy, (4) presence of ferromagnetic foreign bodies or implants that were electrically, magnetically, or mechanically activated anywhere in the body, and (5) presence of major neuropsychiatric diseases. All participants provided written informed consent before participating in this study. The entire experiment was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Yang‐Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan.

MR Image Acquisition

Magnetic resonance imaging scans were acquired on a Siemens 3T whole‐body MRI scanner (Siemens Magnetom Tim Trio, Erlangen, Germany) using a twelve‐channel head coil at the National Yang‐Ming University in Taiwan. All acquired images were aligned to the anterior and posterior commissure. Whole‐brain resting‐state blood oxygen level‐dependent (BOLD) functional MRI (rs‐fMRI) images were collected using a T2*‐weighted gradient‐echo‐planar imaging (EPI) sequence with the following imaging parameters: repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) = 2500/27 ms, flip angle = 77°, matrix size = 64 × 64, field of view = 220 × 220 mm, voxel size = 3.4 × 3.4 × 3.4 mm, 43 interleaved axial slices without intersection gap, and 200 continuous image volumes. Further, anatomical three‐dimensional T1‐weighted images were collected using magnetization‐prepared rapid gradient‐echo sequence with the following imaging parameters: TR/TE/TI = 3500/3.5/1100 ms; flip angle = 7°; NEX = 1; field of view = 256 × 256 mm2; matrix size = 256 × 256; voxel size = 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3. An additional axial T2‐weighted fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery multishot turbo spin echo sequence (2D‐T2‐FLAIR BLADE; TR/TE/TI = 9000/143/2500 ms; flip angle = 130°; 63 slices; NEX = 1; echo train length = 35; matrix size = 320 × 320; field of view = 220 mm; slice thickness = 2.0 mm; voxel size = 0.69 × 0.69 × 2.0 mm) was performed. All structural MRI scans were visually reviewed by an experienced neuroradiologist to confirm that participants were free from any morphologic abnormality. The total scanning time for each participant was 40 min.

Resting‐State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The technique of rs‐fMRI has been widely used to calculate intrinsic functional connectivity of the brain by measuring the BOLD signal fluctuations at the resting state 29. RSNs have been proven to be a powerful tool for studying large‐scale in vivo brain function 30, 31, 32. The connectivity pattern of the human brain during rest was most commonly investigated by seed‐based correlation or data‐driven methods. For seed‐based techniques, there were some biases in the seed selection, and the resulting RSN maps were markedly affected even by a slightly different seed location 33, 34. These disadvantages can be avoided using techniques driven by exploratory data, such as independent component analysis (ICA), which can identify at least 10 large‐scale RSNs in previous studies 35, 36. Therefore, we use ICA to approach RSNs in our study.

Image Preprocessing

Resting‐state fMRI data were preprocessed using FSL v5.0.6 (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain Software Library; http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/) 37. The preprocessing steps applied to these datasets included (1) correcting for subject movement during the imaging session using a three‐dimensional rigid‐body motion correction (realigned to the first EPI acquisition) using MCFLIRT (Motion Correction using FMRIB's Linear Image Registration Tool), (2) correcting for temporal shifts in fMRI data acquisition (slice timing correction), (3) removing nonbrain tissue using Brain Extraction Tool (BET), (4) smoothing with a 5‐mm full‐width at half‐maximum Gaussian kernel, and (5) high‐pass temporal filtering set at 0.01 Hz to remove low‐frequency drifts. Any participant showing a maximum rotation of 1.5° or displacement of 1.5 mm in any direction was excluded from further analysis. Before large‐scale intrinsic functional network identification using group ICA, the preprocessed time series data were registered into stereotactic space [MNI152 template; Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI), Montreal QC] using a two‐stage spatial registration framework 38, 39. Because of the large sample size in this study, we resampled the MNI‐space time series data into 4‐mm resolution for further group ICA analysis.

Group‐Level Large‐Scale Intrinsic Functional Network Identification using Meta‐ICA Approach

Preprocessed rs‐fMRI dataset was used to generate robust unbiased data‐driven large‐scale intrinsic functional network templates using a metalevel ICA approach 40 using the Multivariate Exploratory Linear Optimized Decomposition into Independent Components (MELODIC) package in FSL 35.

According to the optimized resampling number for meta‐ICA approach in a previous simulation study 40, the preprocessed rs‐fMRI datasets of the 430 subjects were randomized into twenty‐five subsets with fifty age and sex‐matched subjects for each subset. Because of limited computation resource capacity and for reducing over‐fitting problem, we did not include subjects into the temporal concatenation ICA analysis all at once. We identified 40 components displaying maximal spatial independence effects and the characteristics of our own dataset for each MELODIC analysis. The 40 components subsequently were concatenated into a single image file and served as the input for single metalevel ICA to generate the 40 most consistent group‐level component templates. This group‐level meta‐ICA approach decomposes the concatenated 4D dataset (40 components per group‐level ICA analysis × 25 subgroup‐level ICA analysis = 1000 image volumes) into spatial maps of structured component signals in the data.

Individual Large‐Scale Intrinsic Functional Network Identification using Dual Regression Approach

Following group‐level meta‐ICA, subject‐specific measures of functional connectivity strength of all 40 independent components were calculated using a dual regression approach 33, 41. The dual regression procedure was separately applied to each individual preprocessed rs‐fMRI dataset using a multiple regression framework. For each independent component, each participant's voxel‐wised functional connectivity strength map (regression coefficients) was calculated as follows: (1) the 40 nonthreshold spatial component maps identified by group‐level meta‐ICA were spatially regressed against the preprocessed rs‐fMRI dataset of each individual's rs‐fMRI scan. This spatial regression produced separate 40‐column matrices describing mean temporal dynamics at the individual subject level of each equivalent group‐level meta‐ICA component; (2) these 40‐column matrices were then used to temporally regress against the individual preprocessed rs‐fMRI dataset, producing a set of 40 individualized spatial functional connectivity strength maps, which corresponded to group‐level meta‐ICA analysis for each participant. These resultant spatial functional connectivity strength maps indicated synchronization between BOLD temporal dynamics at each voxel and mean scan‐specific BOLD time series of the individualized component.

Identification of Individual Default Mode Subnetwork and Other RSNs using Template Matching Technique

Through spatial cross‐correlation with RSN templates from previously published network templates 42, the top 10 best‐fits were manually compared with three default mode subnetworks and other RSNs based on their neuroanatomical configurations 19, 42.

Retrieve Connectivity Strength for Each Default Mode Subnetwork and Other RSNs in Each Participants

To examine the mean network connectivity of each RSN for each participant, the mean value of connectivity strength across voxels within the RSN template images was calculated for each subject‐specific connectivity map. These specific RSN template images were generated by normalizing group‐level meta‐ICA results by the maximum value and by setting the threshold at 0.4 based on a previous metalevel ICA simulation study 40. These resultant RSN template images were used to retrieve individualized final dual regression results for each participant. These subject‐based mean RSN connectivity scores were the average connectivity strength across all voxels within the corresponding RSN template masks.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses of demographic data and clinical evaluations were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) program, version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Partial correlation was used to observe the association between (1) age and all RSNs after controlling sex and (2) between‐network connectivity and age after controlling other RSNs and sex. The threshold for statistical significance was a P value of <0.05.

Results

Demographics

The final sample comprised 430 subjects (224 men and 206 women) from the original 504 participants. We excluded participants because of severe distortion or artifacts in imaging data (n = 26) or because of relatively poor Mini‐Mental State Examination scores (corrected by age and educational level) 43 (n = 48). The mean age of the participants was 63.78 ± 8.4 years old, ranging from 51 to 85 years old.

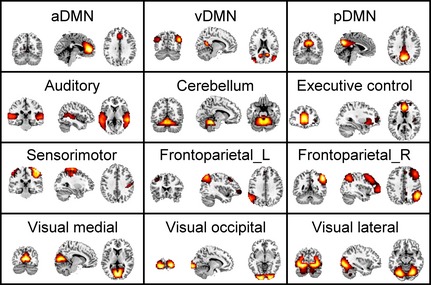

Default Mode Subnetworks and Other RSNs

We performed a 40‐component meta‐ICA using rs‐fMRI data from 430 healthy participants. Based on the visual inspection of spatial maps, we identified 12 components as RSNs and 28 components as ventricular, vascular, susceptibility, or motion‐related artifacts. The spatial maps of the three default mode subnetworks were anterior DMN (aDMN), ventral DMN (vDMN), and posterior DMN (pDMN) (Figure 1), similar to those previously identified 19. The spatial maps of the remaining nine RSNs included the auditory, cerebellum, executive control, left and right frontoparietal, sensorimotor, visual medial, occipital, and lateral networks (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Resting‐state networks. From left to right, the functional connectivity of each component is displayed in coronal, sagittal, and axial views. Anterior default mode subnetwork (aDMN) includes the anterior cingulate, paracingulate gyrus, insular cortex, frontal, and temporal pole. Ventral default mode subnetwork (vDMN) includes the precuneus and posterior cingulate, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, and occipital cortex. Posterior default mode subnetwork (pDMN) includes the posterior cingulate and precuneus, lateral parietal and middle temporal gyrus. The nine other resting‐state networks identified in our study include auditory, cerebellum, executive control and sensorimotor networks, left and right frontoparietal networks; the three visual networks were as follows: visual medial, occipital, and lateral networks.

Age Effect on RSNs

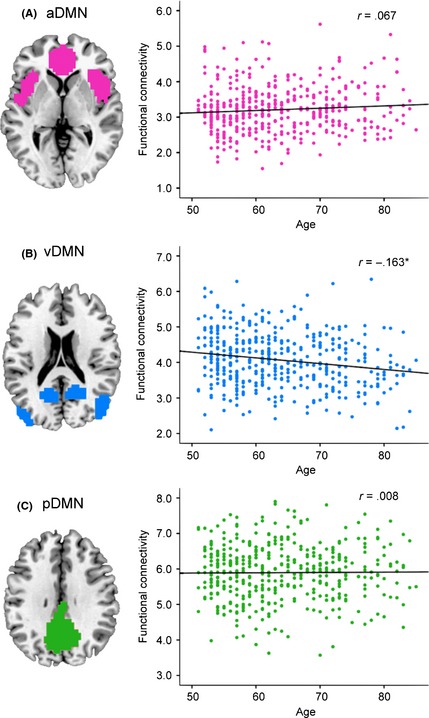

Among the three default mode subnetworks, only vDMN had a marked negative correlation with age after controlling sex (r = −0.163, P < 0.01) (Figure 2). Furthermore, a marked negative correlation was also noted in the auditory (r = −0.144, P < 0.01), right frontoparietal (r = −0.199, P < 0.01), sensorimotor (r = −0.113, P = 0.02), and visual medial (r = −0.188, P < 0.01) networks. Among these five networks, the sensorimotor network does not survive corrections for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni procedure in the analysis of totally 12 RSNs (P < 0.05/12 = 0.004) and should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Figure 2.

Correlation between age and functional connectivity of each default mode subnetwork. Mean connectivity score of each default mode subnetwork for each participant is the average connectivity strength across all voxels within the corresponding default mode subnetwork mask. The resulting connectivity score for each participant is plotted against age. (A) Anterior default mode subnetwork: the regression line shows minimal, but not significant, increase in functional connectivity with age (r = 0.067, P = 0.16). (B) Ventral default mode subnetwork: the regression line shows a mild but marked decrease in functional connectivity with age (r = −0.163, P < 0.01). (C) Posterior default mode subnetwork: the regression line shows minimal, but not significant, increase in functional connectivity with age (r = 0.008, P = 0.88). (*P < 0.05).

Age‐related Pair Relationship of RSNs

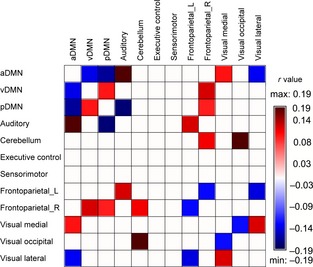

Age‐related connectivity changes between networks were also evaluated after controlling other RSNs and sex, and we discovered that some pairs revealed increased connectivity (0.1 < r < 0.2) with age, some decreased (0.1 < |r| < 0.2), and some had no significant findings (Figure 3). Age‐related increases in functional connectivity were found between aDMN and auditory (r = 0.19, P < 0.01), aDMN and visual medial (r = 0.12, P = 0.01), vDMN and pDMN (r = 0.12, P = 0.02), vDMN and right frontoparietal (r = 0.14, P < 0.01), pDMN and right frontoparietal (r = 0.11, P = 0.02), auditory and left frontoparietal (r = 0.14, P < 0.01), cerebellum and right frontoparietal (r = 0.13, P < 0.01), cerebellum and visual occipital (r = 0.19, P < 0.01), and visual medial and visual lateral (r = 0.14, P < 0.01) networks. Age‐related decreases in functional connectivity were noted between aDMN and vDMN (r = −0.14, P < 0.01), aDMN and pDMN (r = −0.17, P < 0.01), aDMN and visual lateral (r = −0.13, P < 0.01), pDMN and auditory (r = −0.18, P < 0.01), left frontoparietal and right frontoparietal (r = −0.12, P < 0.01), left frontoparietal and visual lateral (r = −0.14, P < 0.01), and visual medial and visual occipital (r = −0.12, P < 0.01) networks. The rest between‐network connectivity was not markedly correlated with age. Among these 16 significant between‐network connections, only four of them survive corrections for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni procedure in the analysis of totally 66 between‐network connections, (P < 0.05/66 = 0.0007), including two increased connectivities (aDMN v.s. auditory network, and cerebellum v.s. visual occipital networks) and two decreased connectivities (aDMN v.s. pDMN, and pDMN v.s. auditory network). Therefore, the interpretation of the age‐related change of the rest between‐network connectivities should be with caution.

Figure 3.

Age‐related associations of resting‐state networks. Age‐related between‐network connectivity changes were evaluated after controlling other RSNs and sex. Red and blue cells represent significant positive and negative correlation with age, respectively. Age‐related increases in functional connectivity were found between aDMN and auditory, aDMN and visual medial, vDMN and pDMN, vDMN and right frontoparietal, pDMN and right frontoparietal, auditory and left frontoparietal, cerebellum and right frontoparietal, cerebellum and visual occipital, and visual medial and visual lateral networks. Age‐related decreases in functional connectivity were noted between aDMN and vDMN, aDMN and pDMN, aDMN and visual lateral, pDMN and auditory, left frontoparietal and right frontoparietal, left frontoparietal and visual lateral, and visual medial and visual occipital networks. The rest between‐network connectivity was not markedly correlated with age. The absolute r values of all red and blue cells are between 0.1 and 0.2.

Discussion

Using a large sample size, age‐related decreased functional connectivity was found in vDMN, auditory, right frontoparietal, sensorimotor, and visual medial networks; there were nine increased between‐network connections and seven decreased connections. The increased vulnerability of vDMN compared with the other two subnetworks is consistent with some previous behavioral studies 19, 23, 24. In healthy elderly, both high and primary function networks deteriorate, demonstrating age‐related network changes in the late stage. The presence of several increased between‐network connections was probably a compensatory reaction or the dedifferentiation of networks, a reverse process to network development 19, 44, 45, 46.

While the overall DMN functional connectivity decreases with age 6, 9, 10, our study further revealed that only vDMN showed this decline, suggesting that normal aging process may first influence only the specific vDMN. vDMN was associated with the function of constructing a mental scene based on memory 19. This hippocampus‐dependent function deteriorates with age, partially resulting in memory impairment 23. In contrast, the functions of self‐referential processing, supported by aDMN, and familiarity and autobiographical memory, supported by pDMN, have been reported to be relatively intact in older adults, although it remains controversial 19, 23, 24. These behavioral results are consistent with our functional network findings. Moreover, the hippocampus, a part of vDMN, played an important role in episodic long‐term memory and navigation; therefore, the reduction of vDMN functional connectivity may also partly underlie age‐related decline of these two functions 24, 47, 48. A recent study showed stable condition of the DMN across lifespan but decreased functional connectivity in the PCU–dPCC network, which is composed of dorsal posterior cingulate cortex, dorsal precuneus, and ventral precuneus 49. The ventral precuneus in PCU‐dPCC network is overlapped with DMN and is highly similar to the vDMN in our study. Thus, the specific functional overlapping of vDMN with PCU‐dPCC network probably also explains why only vDMN decreased functional connectivity with age but not the rest of DMN. Furthermore, the majority of previous rs‐fMRI studies on AD revealed more functional reduction of DMN than normal subjects 50, 51. A previous study compared AD patients with controls based on default mode subnetworks and revealed a more increased functional connectivity of aDMN and vDMN and more decreased functional connectivity of pDMN in patients with AD at baseline. Consistent findings for aDMN and pDMN in AD were mentioned before; however, there is a difficulty in explaining the increased functional connectivity of vDMN in AD because AD pathologically affects the medial temporal lobe first, which is a part of vDMN 19. This decreased functional connectivity in the medial temporal lobe has been largely supported 24. Our results suggest a possible explanation that perhaps, the increased vulnerability of vDMN to normal aging results in less difference or even reverses the finding between AD and controls, but further evaluation is required.

Furthermore, in other RSNs, we found that the auditory, right frontoparietal, sensorimotor, and visual medial networks were negatively correlated with age. Perception considerably interacts with cognition and deficits in the auditory and visual acuity; the sensory and motor ability were common in the elderly 24. Decreased functional connectivity in these three basic function networks was noted in both our study and previous task‐dependent fMRI studies 52, 53. Therefore, these deficits are probably because of not only structural or physical degeneration but also functional processing in the brain or perhaps, decreased functional connectivity is just the result of less external information input. The right frontoparietal network is involved in several functions, such as memory, language, attention, and visual processing, all of which are impaired in the elderly 24, 54. However, the left counterpart was not correlated with age. Previous task studies revealed that some cognitive functions, including some common age‐related impaired functions, such as inhibition and working memory, are more likely related to the right frontoparietal network 24, 55. Perhaps this lateralization explains the different vulnerability between the bilateral frontoparietal networks. The within‐network results of some previous studies were partially different from ours, probably because of variations in population, network template, or imaging analysis methods or software. A notable finding was that visual network revealed age‐related functional connectivity decline 6; however, we discovered that only the visual medial network possessed this decline. Visual medial network was associated with simple visual stimuli (e.g., a flickering checkerboard), whereas visual occipital and lateral networks were related to higher‐order visual stimuli (e.g., orthography) and complex (emotional) stimuli, respectively 56. Previous studies have favored that complex or high‐order visual processing is more affected by aging 57, but our results supported that the visual medial network, involved in processing simple visual stimuli, declined more with age. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that our data may have revealed the late stage of visual network change, whereas the other two networks with higher‐order functions have already decreased to a stable status earlier in life. To resolve this problem, further behavioral studies and RSN evaluation on a wider age group are required.

A previous study has revealed that age‐related decreased connectivity predominantly affects high‐function networks, such as DMN and cingulo‐opercular and frontoparietal control networks, whereas primary function networks, such as somatomotor and visual networks, are preserved 5. Nonetheless, in our study, functional connectivity decreased in both high‐function networks, including vDMN and right frontoparietal network, and primary function networks, including auditory, sensorimotor, and visual medial networks. This difference could be because of the different age groups; the previous study compared younger and older adults, whereas our study merely included relatively older adults. Therefore, the aging process may have initially affected high‐function networks then influenced both high and primary function networks later. This pattern is reverse to the development in children, whose basic function networks mature earlier 58. This phenomenon may be explained by a developmental theory, last‐in‐first‐out theory, or retrogenesis model. This theory which suggested that brain regions developing later were more vulnerable has been applied to gray and white matter changes in aging and neurodegenerative disease 59, 60. The theory is probably also applicable in RSN degeneration. Further, in AD, there was increased functional connectivity in executive network or more complex results that include increased, decreased, and mixed conditions in RSNs 50, 61. Although increased connectivity was not found in our RSNs, it has been reported to occur in the medial and lateral prefrontal regions in healthy elderly 51. However, the condition of increased connectivity in RSNs is more common in AD, probably resulting from more compensation to overcome more deterioration of RSNs. This compensatory change has been noted in task experiments and within DMN and is commonly used to explain overactivation in elderly 19, 44, 59.

A previous study revealed that as age increased, there were decreased correlations between DMN and visual network, salience and temporal networks, and salience and visual networks 6. Much more complex age‐related between‐network changes were identified in our study, including both decreased and increased conditions. These bidirectional changes have been previously noted 5. One explanation is that decreased correlations may be the result of breakdown of between‐network connectivity in the aging process, and increased correlations may be compensatory reactions for preserving global brain function. Another explanation can refer to de‐differentiation in older adults, suggesting the nonselective recruitment of brain regions, probably because of a decreased ability of selecting proper brain regions for performing tasks 59. De‐differentiation is an opposing pattern to the maturation of networks, during which, networks increased internal connectivity and were segregated to achieve functional specialization, thereby underlying cognitive functions 45, 46. From this viewpoint, increased between‐network connectivity can represent decreasing segregation, a process against network development and probably serving as one cause of cognitive impairment. Decreased segregation with age has been found in a recent study and may be considered as an age‐invariant marker of individual difference in cognitive function 62. This process involves both the primary function sensory‐motor system and the high‐function association system, but the decreased segregation in the association system is more prominent after an approximate age of 50, which fits our age group. Our results are compatible with this study, showing decreased segregation with age within primary function system and high‐function system, and we further demonstrate that decreased segregation also exists between primary and high‐function system. For the development of DMN, the anterior–posterior connection, more specifically, the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex, developed last; this link was suspected to be associated with the formation of self‐ and social‐cognitive functions during adolescence 45, 63. Our results displayed weaker age‐related connectivity between the anterior portion of DMN (aDMN) and posterior portions of DMN (vDMN and pDMN), whereas the connection between the posterior two subnetworks was stronger. Our results support that the breakdown of DMN may start from the lastly developed anterior–posterior connection and that the posterior components may be connected more tightly in a compensatory manner, supporting the last‐in‐first‐out theory.

There are several limitations to our study. We only evaluated cross‐sectional conditions of the participants; thus, the results reveal age difference, not aging change, which should rely on follow‐up data. Longitudinal evaluation was also helpful for differentiating whether vDMN is the only one or the first one with age‐related decline. Moreover, we focused on functional changes without including any structural analysis, which could provide a broader view of age‐related brain changes by considering structural differences and their associations with functional results. Besides, the significant findings of the sensorimotor network and many between‐network connectivities do not pass multiple comparison corrections; therefore, whether these results are significant needs further analysis of other data for comparison.

Conclusion

Based on a large sample size, we propose more reliable results for improving the understanding of functional basis of cognitive changes in aging. We found that vDMN is the specific default mode subnetwork with age‐related decline compatible with behavioral science. We also discover several reverse patterns to network development and supporting evidence for last‐in‐first‐out theory in the elderly, including (1) first breakdown of anterior–posterior connection in DMN, (2) decreased connectivity in both high and primary function networks in elderly participants, and (3) emergence of less segregation of networks. A better comprehension of these age‐related network changes can help find solutions to the impact of population aging and can provide a diagnostic pearl for neurodegenerative diseases.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants from the Taiwan National Science Council (NSC 100‐2628‐E‐010‐002‐MY3, NSC 102‐2321‐B‐010‐023); National Health Research Institute (NHRI‐EX103‐10310EI); and a grant from the Ministry of Education, Aim for the Top University Plan of Taiwan. The authors also acknowledge MRI support from the MRI Core Laboratory of National Yang‐Ming University, Taiwan.

References

- 1. United Nations . World population ageing, 1950–2050. New York: United Nations, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grady CL, Maisog JM, Horwitz B, et al. Age‐related changes in cortical blood flow activation during visual processing of faces and location. J Neurosci 1994;14:1450–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raz N, Rodrigue KM. Differential aging of the brain: patterns, cognitive correlates and modifiers. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2006;30:730–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O'Sullivan M, Jones DK, Summers PE, Morris RG, Williams SC, Markus HS. Evidence for cortical “disconnection” as a mechanism of age‐related cognitive decline. Neurology 2001;57:632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geerligs L, Renken RJ, Saliasi E, Maurits NM, Lorist MM. A brain‐wide study of age‐related changes in functional connectivity. Cereb Cortex 2014. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu012 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Onoda K, Ishihara M, Yamaguchi S. Decreased functional connectivity by aging is associated with cognitive decline. J Cogn Neurosci 2012;24:2186–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moussa MN, Steen MR, Laurienti PJ, Hayasaka S. Consistency of network modules in resting‐state FMRI connectome data. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e44428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ghosh K, Agarwal P, Haggerty G. Alzheimer's disease ‐ not an exaggeration of healthy aging. Indian J Psychol Med 2011;33:106–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Damoiseaux JS, Beckmann CF, Arigita EJ, et al. Reduced resting‐state brain activity in the “default network” in normal aging. Cereb Cortex 2008;18:1856–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. He X, Qin W, Liu Y, et al. Age‐related decrease in functional connectivity of the right fronto‐insular cortex with the central executive and default‐mode networks in adults from young to middle age. Neurosci Lett 2013;544:74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shulman GL, Fiez JA, Corbetta M, et al. Common blood flow changes across visual tasks: II. Decreases in cerebral cortex. J Cogn Neurosci 1997;9:648–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang HY, Wang SJ, Xing J, et al. Detection of PCC functional connectivity characteristics in resting‐state fMRI in mild Alzheimer's disease. Behav Brain Res 2009;197:103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Laird AR, Eickhoff SB, Li K, Robin DA, Glahn DC, Fox PT. Investigating the functional heterogeneity of the default mode network using coordinate‐based meta‐analytic modeling. J Neurosci 2009;29:14496–14505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Andrews‐Hanna JR, Reidler JS, Sepulcre J, Poulin R, Buckner RL. Functional‐anatomic fractionation of the brain's default network. Neuron 2010;65:550–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Qin P, Liu Y, Shi J, et al. Dissociation between anterior and posterior cortical regions during self‐specificity and familiarity: a combined fMRI‐meta‐analytic study. Hum Brain Mapp 2012;33:154–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Uddin LQ, Kelly AM, Biswal BB, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Functional connectivity of default mode network components: correlation, anticorrelation, and causality. Hum Brain Mapp 2009;30:625–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Whitfield‐Gabrieli S, Moran JM, Nieto‐Castañón A, Triantafyllou C, Saxe R, Gabrieli JD. Associations and dissociations between default and self‐reference networks in the human brain. NeuroImage 2011;55:225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Damoiseaux JS, Prater KE, Miller BL, Greicius MD. Functional connectivity tracks clinical deterioration in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2012;33:828.e19–828.e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li B, Liu L, Friston KJ, et al. A treatment‐resistant default mode subnetwork in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2013;74:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Starck T, Nikkinen J, Rahko J, et al. Resting state fMRI reveals a default mode dissociation between retrosplenial and medial prefrontal subnetworks in ASD despite motion scrubbing. Front Hum Neurosci 2013;7:802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Campbell KL, Grigg O, Saverino C, Churchill N, Grady CL. Age differences in the intrinsic functional connectivity of default network subsystems. Front Aging Neurosci 2013;5:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kalenzaga S, Sperduti M, Anssens A, et al. Episodic memory and self‐reference via semantic autobiographical memory: insights from an fMRI study in younger and older adults. Front Behav Neurosci 2015;8:449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Riddle DR. Brain aging: models, methods, and mechanisms. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Aging and functional brain networks. Mol Psychiatry 2012;17:549–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wu T, Zang Y, Wang L, et al. Aging influence on functional connectivity of the motor network in the resting state. Neurosci Lett 2007;422:164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Biau DJ, Kernéis S, Porcher R. Statistics in brief: the importance of sample size in the planning and interpretation of medical research. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466:2282–2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee WJ, Liu LK, Peng LN, Lin MH, Chen LK, ILAS Research Group . Comparisons of sarcopenia defined by IWGS and EWGSOP criteria among older people: results from the I‐Lan longitudinal aging study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:528.e1–528.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Raichle ME, Snyder AZ. A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. NeuroImage 2007;37:1083–1090; discussion 1097‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lowe MJ, Mock BJ, Sorenson JA. Functional connectivity in single and multislice echoplanar imaging using resting‐state fluctuations. NeuroImage 1998;7:119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cordes D, Haughton VM, Arfanakis K. Mapping functionally related regions of brain with functional connectivity MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:1636–1644. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo‐planar MRI. Magn Reson Med 1995;34:537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cole DM, Smith SM, Beckmann CF. Advances and pitfalls in the analysis and interpretation of resting‐state FMRI data. Front Syst Neurosci 2010;4:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Van den Heuvel MP, Hulshoff Pol HE. Specific somatotopic organization of functional connections of the primary motor network during resting state. Hum Brain Mapp 2010;31:631–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Beckmann CF, DeLuca M, Devlin JT, Smith SM. Investigations into resting‐state connectivity using independent component analysis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2005;360:1001–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Damoiseaux JS, Rombouts SA, Barkhof F, et al. Consistent resting‐state networks across healthy subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:13848–13853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. FSL. NeuroImage 2012;62:782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal 2001;5:143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Greve DN, Fischl B. Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary‐based registration. NeuroImage 2009;48:63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Poppe AB, Wisner K, Atluri G, Lim KO, Kumar V, Macdonald AW 3rd. Toward a neurometric foundation for probabilistic independent component analysis of fMRI data. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 2013;13:641–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Roosendaal SD, Schoonheim MM, Hulst HE, et al. Resting state networks change in clinically isolated syndrome. Brain 2010;133:1612–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smith SM, Fox PT, Miller KL, et al. Correspondence of the brain's functional architecture during activation and rest. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:13040–13045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population‐based norms for the Mini‐Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA 1993;269:2386–2391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vemuri P, Jones DT, Jack CR Jr. Resting state functional MRI in Alzheimer's Disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 2012;4:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sherman LE, Rudie JD, Pfeifer JH, Masten CL, McNealy K, Dapretto M. Development of the default mode and central executive networks across early adolescence: a longitudinal study. Dev Cogn Neurosci 2014;10:148–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stevens MC, Pearlson GD, Calhoun VD. Changes in the interaction of resting‐state neural networks from adolescence to adulthood. Hum Brain Mapp 2009;30:2356–2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bird CM, Capponi C, King JA, Doeller CF, Burgess N. Establishing the boundaries: the hippocampal contribution to imagining scenes. J Neurosci 2010;30:11688–11695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Harris MA, Wolbers T. Ageing effects on path integration and landmark navigation. Hippocampus 2012;22:1770–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang Z, Chang C, Xu T, et al. Connectivity trajectory across lifespan differentiates the precuneus from the default network. NeuroImage 2014;89:45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Balachandar R, John JP, Saini J, et al. A study of structural and functional connectivity in early Alzheimer's disease using rest fMRI and diffusion tensor imaging. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014. doi: 10.1002/gps.4168 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Barkhof F, Haller S, Rombouts SA. Resting‐state functional MR imaging: a new window to the brain. Radiology 2014;272:29–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cliff M, Joyce DW, Lamar M, Dannhauser T, Tracy DK, Shergill SS. Aging effects on functional auditory and visual processing using fMRI with variable sensory loading. Cortex 2013;49:1304–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Roski C, Caspers S, Langner R, et al. Adult age‐dependent differences in resting‐state connectivity within and between visual‐attention and sensorimotor networks. Front Aging Neurosci 2013;5:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sacco R, Bonavita S, Esposito F, Tedeschi G, Gallo A. The contribution of resting state networks to the study of cortical reorganization in MS. Mult Scler Int 2013;2013:857807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fassbender C, Simoes‐Franklin C, Murphy K, et al. The role of a right fronto‐parietal network in cognitive control—common activations for “cues‐to‐attend” and response inhibition. J Psychophysiol 2006;20:286–296. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Heine L, Soddu A, Gómez F, et al. Resting state networks and consciousness: alterations of multiple resting state network connectivity in physiological, pharmacological, and pathological consciousness States. Front Psychol 2012;3:295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Habak C, Faubert J. Larger effect of aging on the perception of higher‐order stimuli. Vision Res 2000;40:943–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. de Bie HM, Boersma M, Adriaanse S, et al. Resting‐state networks in awake five‐ to eight‐year old children. Hum Brain Mapp 2012;33:1189–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Seidler RD, Bernard JA, Burutolu TB, et al. Motor control and aging: links to age‐related brain structural, functional, and biochemical effects. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010;34:721–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Douaud G, Groves AR, Tamnes CK, et al. A common brain network links development, aging, and vulnerability to disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:17648–17653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Castellazzi G, Palesi F, Casali S, et al. A comprehensive assessment of resting state networks: bidirectional modification of functional integrity in cerebro‐cerebellar networks in dementia. Front Neurosci 2014;8:223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chan MY, Park DC, Savalia NK, Petersen SE, Wig GS. Decreased segregation of brain systems across the healthy adult lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:E4997–E5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Supekar K, Uddin LQ, Prater K, Amin H, Greicius MD, Menon V. Development of functional and structural connectivity within the default mode network in young children. NeuroImage 2010;52:290–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]