Summary

Background

Propofol is a short‐acting, intravenous general anesthetic that is widely used in clinical practice for short procedures; however, it causes depressed cognitive function for several hours thereafter. (R)‐alpha‐methylhistamine (RAMH), a selective histamine H3 receptor agonist, can enhance memory retention and attenuates memory impairment in rats. In this study, we investigated whether RAMH could rescue propofol‐induced memory deficits and the underlying mechanisms partaking in this process.

Methods

In the modified Morris water maze (MWM) test, rats were randomized into the following groups: control, propofol (25 mg/kg, i.p., 30 min before training), RAMH (10 mg/kg, i.p., 60 min before training), and propofol plus RAMH. All randomized rats were subjected to 2 days of training, and a probe test was conducted on day 3. Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials were recorded from CA1 neurons in rat hippocampal slices, and long‐term potentiation (LTP) was induced by either theta‐burst stimulation (TBS) or high‐frequency tetanic stimulation (HFS). Spontaneous and miniature inhibitory (sIPSCs, mIPSCs) or excitatory (sEPSCs, mEPSCs) postsynaptic currents were recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons by whole‐cell patch clamp.

Results

In the MWM task, propofol injection significantly impaired spatial memory retention. Pretreatment with RAMH reversed propofol‐induced memory retention. In hippocampal CA1 slices, propofol perfusion markedly inhibited TBS‐ but not HFS‐induced LTP. Co‐perfusion of RAMH reversed the inhibitory effect of propofol on TBS‐induced LTP reduction. Furthermore, in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons, RAMH significantly suppressed the frequency but not the amplitude of sIPSCs and mIPSCs and had little effects on both the frequency and amplitude of sEPSCs and mEPSCs.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that RAMH, by inhibiting presynaptic GABAergic neurotransmission, suppresses inhibitory neurotransmission in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons, which in turn reverses inhibition of CA1 LTP and the spatial memory deficits induced by propofol in rats.

Keywords: (R)‐alpha‐methylhistamine, Amnesia, Inhibitory transmission, Long‐term potentiation, Propofol

Introduction

Propofol is an intravenous general anesthetic that is routinely used in clinical practice for short procedures due to its short‐acting properties. Generally, people wake up and recover several minutes after the cessation of propofol administration 1, 2. However, cognitive functions, such as learning, memory, reasoning, and planning, remain depressed for several hours thereafter 3, 4. Patients could benefit from a rapid recovery of the cognitive deficits associated with propofol. However, few agents are known to facilitate the recovery of propofol‐induced cognitive deficits.

In both humans and rodents, a subanesthetic dose of propofol causes amnesia indicating that propofol‐induced amnesia is independent of its anesthetic effect 5, 6. Previous studies have revealed that propofol can inhibit long‐term potentiation (LTP), a cellular mechanism of learning and memory in the hippocampus 7, which may contribute to propofol‐induced amnesia. This inhibitory effect is likely due to potentiation of inhibitory neurotransmission mediated by γ‐aminobutyric acid type‐A (GABAA) receptors 7, 8, 9.

Histamine3 (H3) receptors are autoreceptors on histaminergic somata and axon varicosities. They are also heteroreceptors on the somata and the axons of various types of neurons 10. It has been reported that (R)‐alpha‐methylhistamine (RAMH), a selective H3 receptor agonist, could enhance memory retention in water maze and fear conditioning procedures 11, 12 and prevent scopolamine‐induced memory deficits and NMDA‐induced excitotoxicity 13, 14. In addition, studies indicated that H3 receptor agonists or antagonists could diminish or augment GABA release in cultured cortical neurons, the nuclei of the basal ganglia and vestibular nuclei 13, 15, 16. H3 receptors are abundantly expressed in the hippocampal CA1 region, an area associated with memory formation 17. However, little is known about the effect of H3 receptors on inhibitory neurotransmission in this area. In light of the presynaptic location of H3 receptors and their modulatory effect on neurotransmission, we hypothesized that activation of H3 receptors in the hippocampal CA1 area may suppress inhibitory neurotransmission and, in turn, counteract propofol‐induced enhancement of GABA inhibition in the hippocampus and hence propofol‐induced amnesia. Indeed, we discovered in this study that the activation of H3 receptors by RAMH suppressed inhibitory neurotransmission in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons, reversed propofol‐evoked inhibition of LTP in hippocampal slices, and reversed memory deficits induced by propofol in rats.

Materials and methods

Animals and Drugs

All rats were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water provided ad libitum. The animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Board for animal research and performed according to the guidelines for animal use in laboratories established by Fudan University and Second Military Medical University.

Tetrodotoxin (TTX), D‐(‐)‐2‐amino‐5‐phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5), and 6,7‐dinitroquinoxaline‐2,3‐dionewere (DNQX) were obtained from Tocris Bioscience. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), N‐(2,6‐dimethylphenylcarbamoylmethy−l) triethylammonium (QX‐314), propofol, intralipid, RAMH, and all other drugs were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich. Propofol was dissolved in DMSO, and the final concentration was 0.1% in the superfusing artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF). RAMH and the other drugs were administered by addition to ACSF in the in vitro experiment. For the in vivo experiment, 10% propofol (TMDiprivan) was purchased from AstraZeneca.

Morris Water Maze

Our experiments consisted of a two‐day spatial navigation training (day 1 and day 2) and a 1 day probe test (day 3) 18, 19. Male Sprague‐Dawley rats (10–12 week) received treatment before training day 2; RAMH (10 mg/kg) was administered via intraperitoneal injection 1 h before training, and propofol (25 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered half an hour before training. In the control group, propofol and RAMH were replaced by an equivalent amount of intralipid and saline, respectively, given at similar intervals as the experimental group. For the acquisition training, the rats were subjected to eight consecutive trials. The time limit to locate the platform was 120 seconds, and the intertrial interval was 15 seconds. Swimming latency was recorded and analyzed. On training day 1, nonperformers or weak performers were excluded. Nonperformers were defined as rats that could not swim in a coordinated manner or those that floated on the water 19 . Weak performers were characterized by an inability to find the platform after more than three trials 6. The rest were then assigned to the following four groups: control group, propofol group, RAMH group, and propofol+RAMH group. Randomization was achieved in this experiment by applying a randomized block design. Before treatment administration on day 2, the rats were segregated into blocks based on the latency achieved on training day 1, such that each block consisted of four rats with similar latency. Within each of the blocks, allocation was determined by a computer‐generated number.

Twenty‐four hours after training day 2 (day 3), a single probe test was performed; the platform was removed from the pool, and the rats were allowed to swim freely for a fixed amount of time (60 seconds). The average distance to the target site and time spent in the target quadrant were recorded as indicators of spatial memory retention levels.

Hippocampal Slice Preparation

Sprague‐Dawley rats (21–28 days old) were decapitated following diethyl ether anesthesia induction. The brain was rapidly removed and placed in cold normal ACSF that was saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2 mixed gas. The collected hippocampal tissue (350 μm) was immediately sliced using a vibrotome (Lecia, Nussloch, Germany). Slices were placed in an incubation chamber for 30 min at 30°C. They were allowed to recover at room temperature for at least 60 min before being transferred to a recording chamber perfused with gassed ACSF.

Electrophysiological Recordings

The detailed protocol for recording field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) has been described previously 8. The brain slices were perfused with normal oxygenated ACSF, which contained (in mM): 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.3 MgCl2, and 10.0 glucose, with the pH adjusted to 7.4. To obtain fEPSPs from the s. radiatum of the CA1 region, bipolar stimulating electrodes were placed in the Schaffer collateral pathway, and 5–8 MΩ glass electrodes filled with normal ACSF were placed on the s. radiatum for recording. The stimulus intensity was adjusted to evoke 40–50% of the maximum amplitude of fEPSPs. In all experiments, baseline synaptic transmission was recorded for at least 30 min before drug administration or delivery of the stimulus. For LTP induction, two different stimulation protocols, high‐frequency stimulation (HFS) and theta‐burst stimulation (TBS), were utilized. The HFS protocol consisted of three trains of stimuli at 100 Hz delivered with an interval of 20 seconds, while the TBS protocol consisted of 10 bursts of four pulses at 100 Hz, applied at 5 Hz. The strength of synaptic transmission was determined by measuring the maximum slope of the fEPSPs.

Whole‐cell recordings were performed in voltage clamp mode using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). Recordings were made from visually identified pyramidal neurons in the CA1 region at room temperature (25°C). The resistance of the pipettes, which were pulled using a Sutter P‐97 pipette puller (Sutter Instrument Company, Novato, CA, USA), was 2–5 MΩ. Miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) were recorded in the presence of 1 μM TTX, 50 μM AP‐5, and 20 μM DNQX to block fast glutamatergic transmission. The patch pipettes were filled with intracellular solution containing (in mM): 130 CsCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 10.0 HEPES, 0.05 EGTA, 5.0 Mg‐ATP, and 5.0 QX‐314, with the pH adjusted to 7.3 using CsOH and the osmolarity adjusted to 295 mOsm. The series resistance was typically 10–20 MΩ and was partially compensated for 30–50%. The currents were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. Miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) were recorded in the presence of 1 μM TTX, 50 μM picrotoxin, and intracellular solution containing (in mM): 130 potassium gluconate, 10.0 NaCl, 1.0 EGTA, 0.133 CaCl2, 2.0 MgCl2, 10.0 HEPES, 3.5 MgATP, 1.0 Na2GTP, and 5.0 QX‐314, with the pH adjusted to 7.3 using KOH and the osmolarity adjusted to 290 mOsm.

Spontaneous EPSCs and IPSCs were recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons simultaneously using a protocol that was similar to the one previously described 20. The patch pipettes were filled with a low‐chloride intracellular solution containing (in mM): 133.0 KGluconate, 2.0 KCl, 10.0 HEPES, 5.0 EGTA, 10.0 Tris‐phosphocreatine, 4.0 Mg‐ATP, 0.5 Na2GTP, with the pH adjusted to 7.25 using KOH and the osmolarity adjusted to 305 mOsm. Using this internal solution, IPSCs were recorded as outward currents, whereas EPSCs were recorded as inward currents at a holding potential of −30 mV.

Data and Statistical Analysis

In the Morris Water maze experiment, Digbehv‐MG 3.0 software (Jiliang Tech, Shanghai, China) was used for tracking and analyzing the traces. Field EPSPs were recorded and analyzed by the pCLAMP software system (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The slope of the fEPSPs during the 5 min prior to induction of LTP was taken as the baseline, and all values were normalized to this baseline. sIPSC, sEPSC, mIPSCs, and mEPSCs were detected using Mini Analysis software (Synaptosoft Inc., Decatur, NJ, USA) and confirmed visually.

Data collected in this study were expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by a two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test or one‐way or two‐way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey test using SPSS 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

RAMH Prevents Propofol‐Induced Spatial Memory Impairment

The modified Morris water maze protocol 18, 19 was employed to study hippocampal‐dependent spatial learning and memory in rats. During the experiment, six rats were excluded after training day 1 using similar criteria to those previously reported 7, and the remaining thirty‐four were randomly divided into four groups.

None of the three treatment groups, propofol (25 mg/kg, i.p.), RAMH (10 mg/kg, i.p.), or propofol combined with RAMH, significantly affected the latency to find the platform in all eight trials on the second day of training (P > 0.05; Figure 1B). By contrast, during the probe test performed on day 3, propofol significantly reduced the average time spent in the target quadrant (propofol: 21 ± 2%, n = 9, vs. control: 35 ± 3%, n = 9; P < 0.01; Figure 1C) and increased the average distance to the target site (propofol: 701 ± 18 cm vs. control: 582 ± 10 cm; P < 0.001; Figure 1D) compared with the control group. RAMH alone had no effect on either the time spent in the target quadrant or the average distance to the target site. However, pretreatment with RAMH prior to propofol administration significantly prolonged the time spent in the target quadrant (RAMH+propofol: 31 ± 2%, n = 8 vs. propofol: 21 ± 2%, n = 8; P = 0.02; Figure 1C) and shortened the distance to the target site (RAMH+propofol: 634 ± 21 cm, n = 8 vs. propofol: 701 ± 18 cm, n = 8; P = 0.02; Figure 1D). These results indicate that stimulation of H3 receptors with RAMH can rescue propofol‐induced spatial memory deficits in rats.

Figure 1.

(R)‐alpha‐methylhistamine prevents propofol‐induced spatial memory impairment in rats. (A) Representative tracking paths for each group from a single training session. (B) Bar histogram showing that neither propofol nor RAMH had an effect on latency during the second day of spatial navigation learning (n = 9 in Control and Propofol group, n = 8 in RAMH and RAMH+Propofol group). (C–D) Bar histograms showing that propofol administration reduced the time spent in the target quadrant (C) and the average distance to the target site (D) and that RAMH significantly reversed the propofol effect. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 vs. control group; # P < 0.05 versus propofol group by Student's t‐test.

Propofol Suppressed TBS‐ but not HFS‐Induced LTP in Hippocampal CA1 Neurons

LTP is the cellular mechanism involved in the processes of learning and memory 21. Because LTP can be induced by either strong, high‐frequency tetanic stimulation or weak theta‐burst stimulation, we first studied whether propofol would differentially modulate the LTP induced by these two different stimulation protocols. In the control slices, the HFS and TBS protocol both consistently induced a comparable LTP with a maximal fEPSP slope that increased to 138 ± 5% (n = 8) or 132 ± 4% (n = 8) of the baseline at 45 min after HFS or TBS, respectively. In the experimental groups, propofol (50 μM) pretreatment for 20 min failed to alter the degree of LTP induced by HFS stimulation (141 ± 4% of the baseline, n = 8; Figure 2A,C) compared with the control group (P > 0.05). However, it significantly (P = 0.001) inhibited the LTP induced by TBS (110 ± 4% of baseline, n = 8; Figure 2B,D). On the other hand, propofol (50 μM) alone had little effect on baseline synaptic transmission at Schaffer collateral synapses in the hippocampal CA1 region (Figure 1E), which is analogous to previous research where 30 μM propofol was utilized 8.

Figure 2.

Propofol attenuated TBS‐, but not HFS‐induced hippocampal CA1 LTP. (A,B) The above insets are the raw evoked field potential data traces taken at time points 5 min before (black line, 1 and 2) and 30 min after (gray line, 1′ and 2′) stimulation. Both HFS stimulation (A) and theta‐burst (TBS) stimulation (B) induced LTP in the hippocampal CA1 region to a comparable degree. Perfusion of propofol (50 μM) had no effect on HFS‐induced LTP (A) but significantly attenuated TBS‐induced LTP (B). (C,D) Bar histogram showing group data of the propofol effect on either HFS‐induced (C) or TBS‐induced (D) LTP. (E) Perfusion of propofol (50 μM, 30 min) had no effect on the slope of the fEPSPs. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 compared with baseline by one‐way ANOVA; # P < 0.05 compared with control group by Student's t‐test.

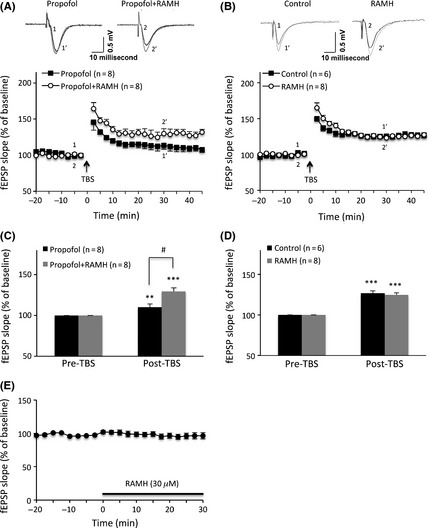

RAMH Reversed Propofol Inhibition of TBS‐Induced LTP in Hippocampal CA1 Neurons

The results mentioned above indicate that propofol can inhibit TBS‐induced LTP in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. In view of the profuse expression of H3 receptors in the hippocampus including the CA1 layer, and because there is evidence that stimulation of H3 receptors with the agonist RAMH enhances memory 11, 12, we investigated whether stimulation of H3 receptors with RAMH could affect LTP induction and/or prevent propofol‐induced LTP reduction. Our results showed that the perfusion of hippocampal brain slices with RAMH (30 μM) alone had no significant effect on TBS‐induced LTP in hippocampal CA1 neurons (P > 0.05, Figure 3B,D). However, compared with the propofol group, perfusion of RAMH (30 μM) prior to propofol considerably reversed the propofol‐induced suppressive effect on the TBS‐induced LTP in hippocampal CA1 neurons. The TBS‐induced LTP was enhanced from 110 ± 4% of the baseline (n = 8) in the propofol only group to 129 ± 4% of the baseline (n = 8) in the RAMH with propofol group (P = 0.001; Figure 3A,C), suggesting that stimulation of H3 receptors in the hippocampus can counteract propofol‐induced LTP reduction.

Figure 3.

(R)‐alpha‐methylhistamine prevented propofol‐induced LTP deficit in rat hippocampal CA1. (A, B) The above insets are the raw evoked field potential data traces taken at time points 5 min before (black line, 1 and 2) and 30 min after (gray line, 1′ and 2′) theta‐burst stimulation. Perfusion of RAMH (30 μM, 30 min) alone had no effect on TBS‐induced LTP (B) but significantly reversed propofol‐induced suppression of TBS‐induced LTP (A) in hippocampal CA1 neurons. (C, D) Bar histogram showing group data for the effect of RAMH alone (D) or with propofol (C) on TBS‐induced hippocampal CA1 LTP. (E) Perfusion of RAMH (30 μM, 30 min) had no effect on the slope of the fEPSPs. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 compared with the baseline by one‐way ANOVA; # P < 0.05 compared with the propofol group by Student's t‐test.

RAMH Suppressed sIPSCs but not the sEPSC Frequency of Hippocampal CA1 Pyramidal Neurons

As mentioned above, the anesthetic action of propofol is likely due to potentiation of inhibitory neurotransmission 7, 8, 9. RAMH mediates its action by activating the H3 receptors, and this in turn can modulate the presynaptic release of the neurotransmitters glutamate and GABA 10, which are both essential participants in LTP induction 21. Putting all this together, we decided to examine whether RAMH alters CA1 LTP by changing excitatory or inhibitory neurotransmission in CA1 pyramidal neurons.

CA1 pyramidal neurons were voltage clamped at −30 mV in hippocampal slices with a low‐chloride intracellular solution, and sEPSCs and sIPSCs were simultaneously recorded (Figure 4A). No obvious run‐down was observed for at least 30 min of continuous recording (n = 5; Figure 4B,C). However, perfusing the brain slices with RAMH (30 μM) after baseline recording significantly decreased sIPSC frequency (P < 0.01, n = 8; Figure 4B) but not sIPSC amplitude (P > 0.05, n = 8; Figure 4D). In contrast, neither the frequency nor the amplitude of the sEPSCs was altered by RAMH perfusion (P > 0.05, n = 8; Figure 4C,D).

Figure 4.

Effect of RAMH on spontaneous IPSC and EPSC frequency in CA1 pyramidal neurons. (A) Representative traces of spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSC) and spontaneous IPSC (sIPSC) at a holding potential of −30 mV from CA1 pyramidal neurons. (The open square denotes the sIPSCs and the open circle denotes the sEPSCs.) (B) Summary of sIPSCs frequency changes in CA1 pyramidal neurons (n = 8) after RAMH administration (indicated by bar). **P < 0.01 compared with baseline and # P < 0.01 compared with control group by two‐way ANOVA. (C) Summary of sEPSC frequency changes in CA1 pyramidal neurons (n = 8) after RAMH administration (indicated by bar). No significant difference was detected by two‐way ANOVA. (D) Bar histogram showing data summary of sEPSC and sIPSC amplitude changes in CA1 pyramidal neurons (n = 8). No significant difference was detected by Student's t‐test.

RAMH Suppressed mIPSCs but not mEPSC Frequency of Hippocampal CA1 Pyramidal Neurons

Miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) and EPSCs (mEPSCs) were recorded while the CA1 pyramidal neurons were voltage clamped at −70 mV in hippocampal slices with TTX (1 M) present in the extracellular solution (Figures 5A, 6A). Both mEPSCs and mIPSCs were steadily recorded for at least 30 min without any obvious run‐down in the time‐controlled experiments (Figure 5D). There were no significant differences for either the frequency or the amplitude of the mIPSCs between the control and the RAMH treatment groups (P > 0.05). However, perfusion of RAMH (30 μM) for 15 min resulted in a slight but significant decrease of mIPSC frequency (P < 0.01, n = 10; Figure 5B,D,E). The suppressive effect of RAMH on mIPSC frequency was observed approximately 6 min after RAMH perfusion. In contrast, mIPSC amplitude was not changed during RAMH perfusion (P > 0.05, Figure 5C,E). On the other hand, neither the frequency nor the amplitude of the mEPSCs was altered by RAMH treatment for over 15 min (P > 0.05, n = 6; Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Effect of RAMH on the mIPSCs frequency and amplitude in CA1 pyramidal neurons. (A) Representative miniature IPSC (mIPSC) traces recorded from two different CA1 pyramidal neurons in the presence of TTX, DNQX, and AP‐5. (B) Cumulative probability plots of mIPSCs recorded from one CA1 pyramidal neuron. The gray solid curve denotes baseline response before RAMH (30 μM) perfusion, and the black dashed curve denotes response during RAMH perfusion. (C) Cumulative amplitude distribution of mIPSCs recorded from one CA1 pyramidal neuron. (D) Graph showing the change in mIPSC frequency after RAMH administration (indicated by bar). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with baseline and RAMH perfusion by one‐way ANOVA. # P < 0.01 compared with RAMH and control group by two‐way ANOVA. (E) Bar histogram showing the maximal mIPSC frequency and amplitude changes in CA1 pyramidal neurons (n = 10). **P < 0.01 compared with the baseline by Student's t‐test.

Figure 6.

Effect of RAMH on mEPSC frequency and amplitude in CA1 pyramidal neurons. (A) Representative recordings of miniature EPSC (mEPSC) traces from two different CA1 pyramidal neurons in the presence of TTX and picrotoxin. (B–C) Corresponding cumulative probability plots of mEPSCs recorded from one CA1 pyramidal neuron. RAMH did not affect the interevent interval or amplitude of the mEPSCs. The gray solid curve denotes the baseline response before RAMH perfusion, and the black dashed curve denotes the response during RAMH (30 μM) perfusion. (D–E) Data summary of mEPSC frequency and amplitude changes in CA1 pyramidal neurons (n = 6). No significant difference was detected by two‐way ANOVA and Student's t‐test.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that in vivo pretreatment with RAMH, an H3 receptor agonist, rescued propofol‐induced spatial memory deficiency in rats. We also established that RAMH reversed the inhibitory effect of propofol on LTP in rat hippocampal CA1 area in vitro. In addition, our patch clamp study suggested that the observed outcome of RAMH treatment might be partly related to its weakening effect on inhibitory neurotransmission in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons as a result of decreased presynaptic inhibitory neurotransmitter release.

The Morris water maze is a widely used hippocampus‐dependent spatial learning and memory test, and its typical training and test protocol can be carried out in 3 days to 2 weeks 19, 22. In clinical practice, propofol‐induced memory deficits last a few minutes to several hours. Therefore, a short 3‐day modified Morris water maze protocol was used, as per prior studies testing the effects of drugs including propofol on short‐term memory 6, 18, 22. During training day 2, the mean escape latency in the control group after 8 trials was less than 10 s, and the percentage of time spent in the target quadrant was approximately 35% in the probe test, which was similar to values previously reported 6. This demonstrated that the 3‐day protocol served its purpose in our current study. Hence, it was applied afterward when testing the consequences of propofol and RAMH treatment on hippocampal‐related spatial memory. Indeed, our results showed that systemic administration of propofol significantly impaired spatial memory but not the learning process, which is in accordance with prior reports in the literature 6.

γ‐aminobutyric acid type‐A receptors have been previously reported to mediate the amnesic component of anesthetics, such as sevoflurane and benzodiazepines 23, 24. Propofol can enhance GABAA receptor function by either direct activation or modulation of receptor desensitization 25. LTP of excitatory synaptic transmission is a major cellular mechanism underlying learning and memory 21; Thus, enhancement of GABAA receptor function is likely to influence LTP and properties of learning and memory. Our study showed that propofol inhibited TBS‐induced LTP in the hippocampal CA1 region, but it had little effect on HFS‐induced LTP in the same area. This phenomenon might be explained by the previous findings that TBS‐induced LTP is more sensitive to changes in GABA‐mediated inhibition than LTP induced by HFS 26, 27, 28. It was also reported that propofol can inhibit NMDA‐independent LTP but not LTP induction in the presence of picrotoxin, a GABAA receptor antagonist 8. This suggests that the inhibitory effect of propofol on TBS‐ but not HFS‐induced LTP might be related to its ability to enhance GABA‐mediated inhibitory neurotransmission. Thus, decreasing GABA inhibition in the hippocampus might reverse propofol‐induced amnesia. Indeed, our in vivo behavioral test and in vitro LTP results demonstrated that the histamine H3 receptor agonist RAMH reversed propofol‐induced memory deficits in the MWM test and the reduction of hippocampal CA1 LTP evoked by TBS stimulation. A limitation arises from variation in age groups of mice utilized in the in vivo (3–4 weeks) and in vitro (10–12 weeks) studies. We believe that this discrepancy will not give rise to inconsistent results, because the GABAergic system develops to relative maturity between the embryonic and the early postnatal period.

Our mechanistic study showed that RAMH reduced sIPSC frequency in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons but had little effect on sEPSCs. Furthermore, the effect of RAMH on inhibitory neurotransmission may be related to modulation of presynaptic inhibitory transmitter release, which is indicated by the reduced mIPSC but not mEPSC frequency after RAMH perfusion. It has been reported that propofol can enhance GABAA receptor function by potentiation of GABA‐evoked currents 25. Therefore, RAMH might weaken inhibitory neurotransmission by a presynaptic pathway, which could counteract propofol‐enhanced inhibitory neurotransmission by a postsynaptic pathway. This result may suggest that the effect on LTP observed with RAMH was mediated, at least in part, by decreased inhibitory transmission but not altered excitatory neuronal transmission in the hippocampal CA1 area.

In addition to this pathway, other pathways involving the aminergic, peptidergic, and cholinergic fibers, which do not produce visible electrophysiological events, should also be considered while determining the mechanism by which RAMH rescues propofol‐induced memory deficits. It has been reported that activation of H3 receptors can enhance acetylcholine release and improve expression of fear‐associated memory 29. GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampal CA1 region receive functional cholinergic inputs, and acetylcholine can enhance GABA release by stimulating alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors 30, 31, 32. However, alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors become desensitized with persistent acetylcholine stimulation, which likely reduces GABAergic inhibition 30, 31. Thus, increased acetylcholine in the hippocampus due to H3 receptor activation could help counteract propofol‐induced amnesia. In addition, extracellular signaling pathway‐mediated molecular alterations may also contribute to the effect on the H3 receptor. Giovannini et al. 11 reported that RAMH‐activated extracellular signal‐related kinase2 in hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons improved memory consolidation in rats.

Previous studies have stated that systematic administration or intrahippocampal injection of the H3 receptor agonist RAMH enhanced memory performance in water maze and fear conditioning procedures 11, 12. However, in our current experiment, pretreatment with RAMH (10 mg/kg, i.p.) had only a small effect on the learning and memory process, at least in the modified MWM model. These discrepancies may be accounted for by our use of different behavioral tasks and distinct protocols. The MWM task mainly tests hippocampal‐dependent spatial memory (explicit memory), while the fear conditioning procedure tests fear memory (implicit memory), which may involve an alternate intrinsic mechanism. In the Rubio et al. experiment 12, the training course consisted of 4 days, while in our experiment, the rats were trained for 2 days only. Therefore, the discrepant results obtained may indicate that RAMH has less effect on short‐term spatial memory than long‐term spatial memory.

In conclusion, there is evidence that propofol‐induced memory deficits most likely result from enhanced inhibitory neurotransmission. However, the blockage of GABA receptors by antagonists is clinically intolerable because of the receptor's essential physiological function. It is well established that a blockage of GABA receptors or GABA deficiency can have grave repercussions 33, 34. In this respect, our current experiment demonstrates that activation of H3 receptors with RAMH can modulate GABAergic inhibitory neurotransmission by suppressing presynaptic GABA release in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. This inhibitory effect of RAMH consequently rescued propofol‐induced amnesia, possibly via balancing propofol‐enhanced GABA receptor function. Provided that further comprehensive research is undertaken, our experiment raises the possibility of developing a novel candidate intervention for prompt cognitive function recovery following propofol anesthesia or other GABA‐enhancing anesthetics.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81070880, 81100815, 31129003 and 81171224), the Key Basic Research Projects of Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No. 12JC1410902, 11ZR1401700), the Key Research Projects of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (No. 13ZZ056), the Program for Outstanding Academic Leader of Shanghai Municipality and the Shanghai Health bureau (No. XYQ2011022).

The first two authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1. Johnston R, Noseworthy T, Anderson B, Konopad E, Grace M. Propofol versus thiopental for outpatient anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1987;67:431–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Korttila K, Nuotto EJ, Lichtor JL, et al. Clinical recovery and psychomotor function after brief anesthesia with propofol or thiopental. Anesthesiology 1992;76:676–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanou J, Goodall G, Capuron L, Bourdalle‐Badie C, Maurette P. Cognitive sequelae of propofol anaesthesia. NeuroReport 1996;7:1130–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O'Gorman DA, O'Connell AW, Murphy KJ, et al. Nefiracetam prevents propofol‐induced anterograde and retrograde amnesia in the rodent without compromising quality of anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1998;89:699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zacny JP, Lichtor JL, Coalson DW, et al. Subjective and psychomotor effects of subanesthetic doses of propofol in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology 1992;76:696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang H, Zhang SB, Zhang QQ, et al. Rescue of cAMP response element‐binding protein signaling reversed spatial memory retention impairments induced by subanesthetic dose of propofol. CNS Neurosci Ther 2013;19:484–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Takamatsu I, Sekiguchi M, Wada K, Sato T, Ozaki M. Propofol‐mediated impairment of CA1 long‐term potentiation in mouse hippocampal slices. Neurosci Lett 2005;389:129–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nagashima K, Zorumski CF, Izumi Y. Propofol inhibits long‐term potentiation but not long‐term depression in rat hippocampal slices. Anesthesiology 2005;103:318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wei H, Xiong W, Yang S, et al. Propofol facilitates the development of long‐term depression (LTD) and impairs the maintenance of long‐term potentiation (LTP) in the CA1 region of the hippocampus of anesthetized rats. Neurosci Lett 2002;324:181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leurs R, Bakker RA, Timmerman H, de Esch IJ. The histamine H3 receptor: From gene cloning to H3 receptor drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2005;4:107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giovannini MG, Efoudebe M, Passani MB, et al. Improvement in fear memory by histamine‐elicited ERK2 activation in hippocampal CA3 cells. J Neurosci 2003;23:9016–9023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rubio S, Begega A, Santin LJ, Arias JL. Improvement of spatial memory by (R)‐alpha‐methylhistamine, a histamine H(3)‐receptor agonist, on the Morris water‐maze in rat. Behav Brain Res 2002;129:77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bergquist F, Ruthven A, Ludwig M, Dutia MB. Histaminergic and glycinergic modulation of GABA release in the vestibular nuclei of normal and labyrinthectomised rats. J Physiol 2006;577:857–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smith CP, Hunter AJ, Bennett GW. Effects of (R)‐alpha‐methylhistamine and scopolamine on spatial learning in the rat assessed using a water maze. Psychopharmacology 1994;114:651–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dai H, Fu Q, Shen Y, et al. The histamine H3 receptor antagonist clobenpropit enhances GABA release to protect against NMDA‐induced excitotoxicity through the cAMP/protein kinase A pathway in cultured cortical neurons. Eur J Pharmacol 2007;563:117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yamamoto Y, Mochizuki T, Okakura‐Mochizuki K, Uno A, Yamatodani A. Thioperamide, a histamine H3 receptor antagonist, increases GABA release from the rat hypothalamus. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 1997;19:289–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pillot C, Heron A, Cochois V, et al. A detailed mapping of the histamine H(3) receptor and its gene transcripts in rat brain. Neuroscience 2002;114:173–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Giorgi M, Modica A, Pompili A, Pacitti C, Gasbarri A. The induction of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 4 gene (PDE4D) impairs memory in a water maze task. Behav Brain Res 2004;154:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vorhees CV, Williams MT. Morris water maze: Procedures for assessing spatial and related forms of learning and memory. Nat Protoc 2006;1:848–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wuarin JP, Dudek FE. Patch‐clamp analysis of spontaneous synaptic currents in supraoptic neuroendocrine cells of the rat hypothalamus. J Neurosci 1993;13:2323–2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: Long‐term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature 1993;361:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Feldman LA, Shapiro ML, Nalbantoglu J. A novel, rapidly acquired and persistent spatial memory task that induces immediate early gene expression. Behav Brain Funct 2010;6:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ishizeki J, Nishikawa K, Kubo K, Saito S, Goto F. Amnestic concentrations of sevoflurane inhibit synaptic plasticity of hippocampal CA1 neurons through gamma‐aminobutyric acid‐mediated mechanisms. Anesthesiology 2008;108:447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ghoneim MM, Mewaldt SP. Benzodiazepines and human memory: A review. Anesthesiology 1990;72:926–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bai D, Pennefather PS, MacDonald JF, Orser BA. The general anesthetic propofol slows deactivation and desensitization of GABA(A) receptors. J Neurosci 1999;19:10635–10646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Staubli U, Scafidi J, Chun D. GABAB receptor antagonism: Facilitatory effects on memory parallel those on LTP induced by TBS but not HFS. J Neurosci 1999;19:4609–4615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Perez Y, Chapman CA, Woodhall G, Robitaille R, Lacaille JC. Differential induction of long‐lasting potentiation of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials by theta patterned stimulation versus 100‐Hz tetanization in hippocampal pyramidal cells in vitro. Neuroscience 1999;90:747–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Costa AC, Grybko MJ. Deficits in hippocampal CA1 LTP induced by TBS but not HFS in the Ts65Dn mouse: A model of Down syndrome. Neurosci Lett 2005;382:317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cangioli I, Baldi E, Mannaioni PF, et al. Activation of histaminergic H3 receptors in the rat basolateral amygdala improves expression of fear memory and enhances acetylcholine release. Eur J Neurosci 2002;16:521–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Frazier CJ, Rollins YD, Breese CR, et al. Acetylcholine activates an alpha‐bungarotoxin‐sensitive nicotinic current in rat hippocampal interneurons, but not pyramidal cells. J Neurosci 1998;18:1187–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Frazier CJ, Buhler AV, Weiner JL, Dunwiddie TV. Synaptic potentials mediated via alpha‐bungarotoxin‐sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci 1998;18:8228–8235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kanno T, Yaguchi T, Yamamoto S, et al. 8‐[2‐(2‐pentyl‐cyclopropylmethyl)‐cyclopropyl]‐octanoic acid stimulates GABA release from interneurons projecting to CA1 pyramidal neurons in the rat hippocampus via pre‐synaptic alpha7 acetylcholine receptors. J Neurochem 2005;95:695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kang JQ, Barnes G. A common susceptibility factor of both autism and epilepsy: Functional deficiency of GABA(A) receptors. J Autism Dev Disord 2013;43:68–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brickley SG, Mody I. Extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors: Their function in the CNS and implications for disease. Neuron 2012;73:23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]