Abstract

Introduction:

Singapore has a strong and well-established tobacco control policy, but smoking rates among young Singaporeans remain relatively high. In other countries, tobacco companies have used menthol to encourage smoking among young people. Singapore still permits the sale of menthol tobacco products and little is known about the tobacco industry’s internal strategy and motivation for marketing menthol tobacco in Singapore.

Method:

Tobacco industry documents analysis using the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents Library. Findings were triangulated with Euromonitor market data on menthol tobacco in Singapore, and trend data on smoking prevalence in Singapore from the First National Morbidity Survey, Labour Force Survey, National Health Survey and National Health Surveillance Survey.

Results:

Menthol tobacco products became popular among young Singaporeans in the early 1980’s, largely due to a health-consciousness trend among young people and the misperception that menthol tobacco products were ‘safer’. Philip Morris, in an attempt to compete with R.J. Reynolds for starter smokers, developed and launched several menthol brands designed to appeal to youth. While many brands initially failed, as of February 2018, menthol tobacco products comprise 48% of Singapore’s total tobacco market.

Conclusions:

Menthol is key to the tobacco industry’s strategy of recruiting and retaining young smokers in Singapore. Banning the sale of menthol tobacco products will be an important part of preventing smoking in Singapore’s younger generation.

INTRODUCTION

Singapore is a small, developed city-state in Southeast Asia whose tobacco market is dominated by three transnationals: Philip Morris International (PM – 47%), British American Tobacco (BAT – 21%), and Japan Tobacco International (JTI – 25%).1

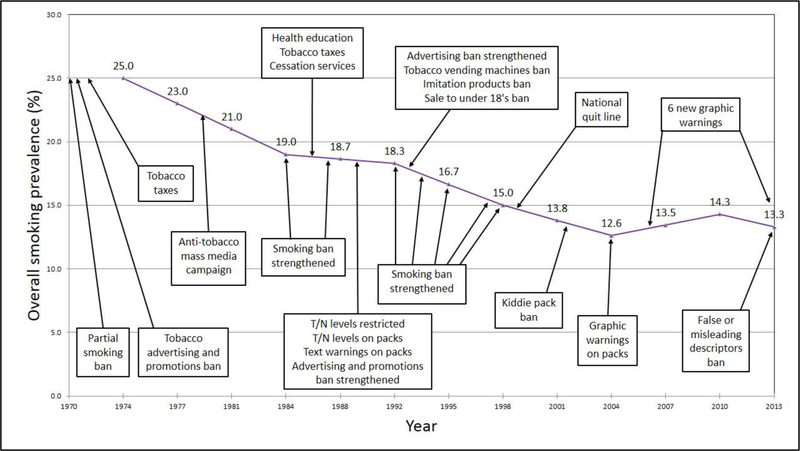

Singapore has a strong tobacco control history (Figure 1), with strict policies on tobacco advertising, mass media campaigns on the health effects of smoking, and tobacco product regulations.2 The smoking prevalence in Singapore is lower than in other Southeast Asian countries,3 and dropped from 25% (1974) to 13% (2004), but it has not decreased since 2004 (Figure 1);4, 5 remaining steady at 13% in 2013–2016.6 Smoking prevalence is higher among young adults age 18–29 than the general population, and rates in this group increased from 12% (2004)7 to 16% (2010).8 Smoking rates are also higher among men (25%) than women (5%),8 although smoking rates among women age 18–29 rose from 5% (1998) to 9% (2007).9

Figure 1:

Smoking prevalence trend and timeline of tobacco control measures implemented in Singapore, 1970–2013. Data sources: Singapore First National Morbidity Survey, Labour Force Survey, National Health Survey and National Health Surveillance Survey. ‘T/N’ = tar/nicotine.

Most Singaporeans start smoking before age 21.7 Qualitative research with youth smokers in Singapore (age 15–29) suggests that flavored cigarettes facilitate initiation; users believe they are milder and thereby ‘healthier’ than regular cigarettes.10 Research from the European Union, United States, Canada, Brazil, Australia and New Zealand consistently shows that flavored tobacco, particularly menthol, encourages smoking initiation among young people.11, 12 However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no published study of menthol marketing in Singapore.

In 2016, Singapore’s health authorities held a public consultation for banning characterizing flavors including menthol in tobacco, along with other measures (plain packaging, larger graphic health warnings, raising the minimum age of sale to 21).6 Although the other measures were approved or considered,6, 8 there has been no further discussion on banning flavored tobacco. As of February 2018, Singapore still permits sales of menthol tobacco and cigarettes with flavor capsules.6

The tobacco industry has a well-established history of using menthol to encourage smoking initiation,13, 14 yet little is known on the industry strategies for marketing menthol tobacco products in Singapore. We conducted a qualitative analysis of tobacco industry documents to understand the role menthol played in industry strategies to target and recruit young smokers in Singapore.

METHODS

The Truth Tobacco Industry Documents Library, an online archive of over 14 million previously secret tobacco industry documents released through litigation against tobacco companies (available at https://industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/), provides unique insights into tobacco industry perspective. Document analysis combined traditional qualitative methods for textual analysis15 with iterative search strategies; documents were included based on relevance to the research question and novelty of information, excluding irrelevant, repeat or unverifiable documents.

The first author conducted searches from August to November 2017 using a snowball search technique,16 starting with the initial search term “Singaporean AND menthol”. This yielded 120 documents. We conducted extensive follow-up searches to answer more specific questions that arose when reading the first documents with adjacent documents in the collection (by Bates numbers) and keyword searches of names of relevant individuals (e.g. “Jeremy Jilla”), project code names (e.g. “Byzantium”), and brands (e.g. “Accord AND Singapore”) until we reached saturation. We reviewed and organized the documents by theme and chronologically in order to assess internal consistency, and to construct a timeline of reasonable events. The first author wrote summaries of findings with appropriate citations, which were reviewed by all authors. Per standard archival research methodologies,17 all authors read and reread documents to determine meanings and importance within the context of other collected documents. Ambiguities in document content were addressed using targeted searches based on personnel, project titles, key words or phrases, and dates in order to clarify the document’s authorship, meaning, or influence on the tobacco company’s activities. Searches continued until we reached saturation, and additional searches uncovered only previously seen or duplicate documents. After filtering out duplicates and irrelevant documents (such as news articles mentioning Singapore but not menthol marketing), we analyzed a final set of 90 documents.

To further contextualize and validate the information found in documents, we triangulated this information with tobacco market data in Singapore, including 2011–2016 data purchased from Euromonitor, 2001 and 2010 published menthol market data, and 1974–2013 trend data on smoking rates in Singapore obtained from the Singapore First National Morbidity Survey, Labour Force Survey, National Health Survey and National Health Surveillance Survey.18 We also utilized previously described methods18 to triangulate the marketing plans identified within the documents with and archival and current examples of menthol cigarette advertising and packaging.

RESULTS

Most menthol marketing efforts identified were between 1983 and 1994, primarily from PM and, to a lesser extent, BAT and R.J. Reynolds (RJR – now JTI). These efforts were coordinated between PM’s offices in New York, Richmond, Virginia, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Third party research contractors included Consumer Probe in Singapore, Norsearch International, and Survey Research Singapore.

The early menthol tobacco market in Singapore

In 1972, Survey Research Singapore conducted focus groups on ‘mild’ and menthol tobacco in Singapore for the Singapore Tobacco Company (a BAT subsidiary).19, 20 The first study (10 focus groups with smokers age 18–55) found that Singapore’s menthol tobacco market was small and dominated by the Rothmans brand Consulate, which was considered a starter brand, especially for young people and women.19 The second study (4 focus groups with smokers age 25–55) found that “there may be some market *for mild cigarettes] as a ‘stepping stone’ brand for beginners.”20, pg.22 This might also include menthol cigarettes, which were often perceived as ‘mild’.21

In 1983–1985, the menthol market share in Singapore increased from 14% to 23%. Most of this growth came from Salem,22 an RJR brand whose market share increased from 2% to 5% in 1983 and 13% in 1985,22, 23 dominating the Singapore menthol tobacco market.24 At the time, Singapore was running mass media campaigns on the health effects of smoking and had a partial tobacco advertising ban which was strict for its time.2 Salem’s popularity was partly due to trends among young people to switch to mentholated tobacco brands, which were (incorrectly) perceived as healthier. Jeremy Jilla (General Manager, PM Singapore) observed:

Successive anti-smoking campaigns by the Government of Singapore in the late 70’s/early 80’s raised consumer concerns about the Smoking and Health issue. In the absence of any T/N *tar/nicotine content+ information… the mentholated Salem with its cool, soothing draw came to be incorrectly perceived as a mild cigarette. This curious phenomenon has led to a situation where in an increasingly health-conscious society, a bona fide low tar segment has yet to develop… whereas the menthol segment at 30% has become the de facto low tar segment.21, pg.1

Targeted Salem promotions in local discos and nightclubs also contributed to its popularity,25 as did its positioning as a mainstream, unisex product.26 According to PM Asia’s 1987 focus group studies with Singaporean smokers age 16–35: “Salem smokers seem to sway with the crowd… today unisex is the ‘in’ thing.”27, pg.3

In Singapore, Salem was especially popular among young people and ‘starters’ (initiating smoking).28 A 1985 Singapore market study, prepared by Norsearch International for PM Asia, found that most smokers age 16–25 were using Marlboro Reds (43%) or Salem (35%), and that Salem smokers were “the most likely to have tried to stop smoking in the past 12 months”28, pg.44 and more likely to believe that menthol cigarettes were “healthier than regular cigarettes.”28, pg.81 PM Asia’s 1987 Singapore General Consumer Survey further found that 66% of smokers believed that low tar/nicotine cigarettes were less harmful, and 61% thought that menthol cigarettes contained lower levels of tar/nicotine.29 Salem actually contained similar tar/nicotine levels to Marlboro Red.27

Competition between Salem and Marlboro for young and starter smokers

Before Salem became popular, Marlboro (Reds) were the most popular cigarettes among young smokers in Singapore. Elizabeth Butson (Vice President, PM Marketing Services) noted in a 1985 letter to colleagues that Marlboro grew quickly in Singapore after the late 1970’s with a peak market share of almost 19% in 1983, and that “Marlboro’s smoker profile was the youngest of any brand on the market.”23 As Salem’s popularity grew, Marlboro fell to 17%, and Salem’s smoker profile was “even younger than Marlboro’s.”23 In February 1986, Joe Tcheng (Coordinator, PM Marketing Services), wrote to Butson that “Salem is the No. 1 brand amongst the 16–19 age group with a 29% share. Its strength is in the 16–25 group. The brand has taken away from Marlboro a huge chunk of entry *starter+ smokers.”22 PM Asia’s 1987 focus groups with Marlboro and Salem smokers age 16–35 in Singapore also found that Marlboro’s rugged, macho brand imagery, characterized by the ‘Marlboro cowboy’ was outdated to young Singaporeans following mainstream, unisex fashions from Tokyo or Hong Kong.27

Starter smokers were particularly important because smoking rates among young Singaporeans were increasing. According to PM Asia’s 1987 Singapore research, smoking rates in Singapore decreased from 22% (1983) to 18%, but among Singaporeans below age 26 they increased from 17% (1983) to 24% (1987).29 PM Asia concluded that:

Young smokers are an especially important target segment for the Singapore market… All the brands which have a young appeal… gained in smoker share. The gains are mainly attributable to the success of attracting new young smokers. Thus, the younger groups who constantly are entering the market (as new and different people) must be carefully watched, and their current needs, wants, values, interests and activities monitored.29, p.10

In its 1986 Market Research Seminar, PM studied different youth market segments in Singapore, emphasizing that “the key new business opportunities for Philip Morris in Singapore are among the young [age 16–25] market segments.”30, pg.250 PM divided this group into 4 youth market segments, based on their psychographic profile (lifestyle, values, and aspirations), and the most suitable types of product and branding (Table 1).30 PM concluded that it could target segment 1 with a “smooth mellow flavored menthol.”30, pg.253 A 1985 PM study further suggested that most Salem smokers fit into segments 1 or 2 as they preferred a stylish brand with “a fresh, cool tobacco taste” or used Salem because of health concerns.28 During the 1980s PM developed and launched several menthol tobacco brands in Singapore to regain youth market share and compete with Salem (Table 2).31

Table 1:

Youth market segments in Singapore as identified in PM’s 1986 Market Research Seminar.35

| Segment | Profile | Description | Share of smokers age 16–25 | Target product and brand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Social, carefree, young menthol smokers | “A sociable and rather hedonistic group of young people who are concerned about appearances” (pg.251) | 28% | “Menthol cigarettes which they believe are smoother, milder and cool tasting” (pg.251) |

| 2 | Sportive, health conscious, young menthol smokers | “Very concerned about the effect of smoking on their health,” “active, independent”, and “interested in sport and an individual lifestyle” (pg.252) | 26% | “A healthy low tar and nicotine menthol cigarette with a white filter that absorbs tar and nicotine” (pg.252) |

| 3 | Ambitious, independent, young, full flavor smokers | “Not concerned about the effects of smoking on their health,” “ambitious, individualistic” and “expect to move up in the world.” (pg.252) | 25% | Not menthol or light; “a strong high quality tobacco flavor” (pg.252) |

| 4 | Insecure, conformist, compulsive smokers | “Compulsive smokers who believe it is most important to smoke the right brand and be well accepted by others” (pg.253) | 21% | “An exclusive but trendy popular cigarette, well packaged” (pg.253) |

Table 2:

Menthol tobacco products developed and/or launched by PM to compete with Salem in Singapore, 1983–1988.

| Brand name | Project code name(s) | Date started development plans | Date launched in Singapore | Outcome | Sample advert for Singapore audience | Description of sample advert |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marlboro Menthol | MM, Suzie37 | Not known | May 198333 | Rejected by consumers | None found | |

| Marlboro Lights Menthol | MLM, Pansy33 | November 198433 | Not known | Rejected by consumers in March 1987 tests30 |  |

A rugged cowboy with horses, smoking a cigarette in a refreshing mountain scene30 |

| Virginia Slims Lights Menthol | VSLM | Not known | Quarter 1 of 198541 | Share rose from 0.1% (1985) to 1.7% (1987)32 |  |

A young Western woman in a stylish dress, smoking a cigarette30 |

| Accord | Dial-A-Menthol | July 198544 | July 198648 | Failed to sustain consumer interest |  |

Proposed packaging for the Accord brand in Singapore85 |

| Not known | Generic Menthol | July 198544 | Not launched | To be launched only if Dial-A-Menthol and VSLM failed44 | None found | |

| California | Byzantium | August 198553 | Not launched | Target launch December 1987;51 fell through |  |

A surfer rides a wave with the tagline ‘listen to the wave’86 |

| Alpine | RFM,87 Alpine | March 198730 | September 198839 | 5.1% share in Oct 1988; dropped to 0.4% in Nov 1988 with no rebound24 |  |

A man lies in a hammock while a woman caresses his back, with the tagline ‘fresh is Alpine’30 |

Marlboro line extensions and the launch of ‘Alpine’

In May 1983, PM launched Marlboro Menthol cigarettes in Singapore “as an initial reaction to Salem’s growth”32, pg.5 (Table 2). While rated similarly to Salem in blind taste tests, Marlboro Menthol failed because consumers perceived the product as having too little menthol and too strong a taste. Staff at PM Asia concluded that the macho brand image of Marlboro Reds affected consumer perceptions of Marlboro Menthol, which led to its rejection among Salem smokers favoring a more unisex image.33

PM then developed Marlboro Lights Menthol (MLM) for the Singapore market.32 In brand imagery tests, Salem smokers thought the MLM imagery was too rough while Marlboro smokers thought it was out of place: “the Marlboro cowboy is expected to be tough; not a sissy to be seen with a menthol cigarette.”27, pg.36 The study concluded that the MLM brand was unlikely to succeed against Salem, although it might be targeted at those who “might consider reducing smoking or move on to a milder cigarette for health reason.”27, pg.33

In March 1987, PM rebranded Marlboro Menthol as ‘Alpine’, to overcome issues with the Marlboro brand imagery.34 In brand image tests consumers viewed the Alpine hero as classy, decisive and “in control of his women,”27 and Salem smokers identified the Alpine packaging, featuring a mountain and a fresh, light image, as an attractive concept.21 Alpine’s launch was heavily supported with price promotions and a brand diversification strategy.21, 35 PM’s post-launch research found that Alpine appealed to young people and Salem smokers36 and that awareness and interest in the brand was high,21 but consumer interest was not sustained.37 Jilla reasoned that Alpine’s failure was due to its lack of distinctive product advantages over Salem.21

The launch of Virginia Slims Lights Menthol

In December 1984, PM planned to launch Virginia Slims Lights Menthol (VSLM), in the Singapore market (Table 2).38 Virginia Slims had, in other countries, successfully encouraged smoking among young women with feminist slogans and a slim, trendy cigarette design and packaging.39, 40 At the time, the female market segment in Singapore was small (around 6%), but growing. PM planned VSLM to target young, high-income women with a trendy, Westernized lifestyle.38, 41

According to PM Asia’s Singapore 1987 General Consumer Survey, VSLM appealed to both young women and men, particularly Salem smokers. PM Asia subsequently adopted a more gender-neutral image for VSLM by eliminating feminist slogans (such as ‘You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby’) and projecting a seductive as opposed to liberated tone.29 PM Asia’s Singapore 1988 General Consumer Survey found that VSLM was a good competitor against Salem as a result. PM Asia emphasized the importance of targeting young men with VSLM, because “with nine out of ten Singapore smokers male, gains must be made here if the brand is to grow meaningfully.”42, pg.4 From 1987–1988, VSLM’s market share further increased to 2.1%, almost tripling its share of male smokers in Singapore from 0.6% (1987) to 1.5% (1988).43

Other menthol brands

In July 1985, PM planned to launch Accord, a menthol cigarette with an adjustable filter to change the amount of menthol delivered (Table 2).41 Initially, Accord generated consumer interest,44 but this was not sustained. A 1987 consumer survey reported the menthol dial on Accord did not really deliver different amounts of menthol and the highest setting still delivered less menthol than Salem.27

In August 1985, PM developed the ‘California’ brand to alleviate “the critical market situation” (PM’s loss of starter smokers to Salem).23 A 1986 PM report described: “California is casual & carefree; it is fresh, free and fun. It is a world where the young people would like to be.”45 In an April 1988 letter to colleagues at PM Asia, Jilla further described how the brand, “with its hint of the unconventional,” had “a rebelliousness which today’s young smoker would empathise with.”46 Background visuals for California would feature beach-related scenes, which young Singaporeans had responded to strongly in formative research (Table 2).47 California’s launch included point-of-sale advertising, promotional materials such as free sunglasses and inflatable palm trees, and ‘California Nights’ promotions in discos. In a May 1987 note to Butson, Tcheng wrote that the disco promotions were important “not only for target sampling but it is probably the only way we can get some imagery across.”48, pg.3

The California product was designed to be similar to Salem, but with a unique taste,49 sweetened tipping paper (encasing the filter), and scented tear tape (around tobacco packs).23 Tcheng expected these features to “appeal to the Pepsi generation,” notably “young male Salem smokers.”49 However, California’s launch in Singapore fell through46, 50 due to issues with the tear tape.51 The tape’s minty scent was encapsulated in urea formaldehyde, an eye and skin irritant, so PM’s research and development team advised against using the scented tear tape,52 which resulted in the decision not to launch California as it lacked a meaningful difference with Salem.53

Outcome of efforts at Philip Morris to compete with Salem

As of 1988, the only menthol tobacco brand that PM had successfully launched in Singapore was VSLM.21 PM’s 1994 Singapore General Consumer Survey indicated VSLM was popular among young women54 and 11% of those who started smoking initiated with VSLM.55 In a May 1989 letter to his colleagues, Jilla reasoned that other brands failed because Singapore’s strict tobacco advertising ban made it “a difficult market in which to establish new brands.”56 At the time, the Singapore Government planned to mandate that all tobacco manufacturers print tar and nicotine content on tobacco packs. Jilla suggested that this mandate, along with the health consciousness trends, meant that “the next big cigarette marketing opportunity *in Singapore+ will be the emergence of a genuine mid to low tar segment.”56 PM planned refresh the image of Marlboro Lights, and to launch MLM once Marlboro Lights showed signs of market growth.57

PM Asia’s Singapore General Consumer Surveys indicated that, in 1989 – 1994, Salem dominated the menthol segment58 and had the largest share of starter smokers, although Marlboro was starting to catch up.55 In 1989, both brands attracted similar proportions of starter smokers (Marlboro 20%, Salem 19%). By 1993 and 1994, Salem had most starters (25%),59 while 23% of starters initiated with Marlboro Red, 6% with Marlboro Lights, and 4% with Marlboro Menthol.59 From 1989 – 1994, Marlboro Lights Menthol showed little growth,59 but Marlboro Menthol’s share grew from 0.3% (1990) to 1.9% (1993)59 and the Marlboro line grew from 22% (1989)58 to 31% (1994),55 mainly because of the growing popularity of Marlboro Menthol and Marlboro Lights among starter smokers.55 Singapore’s smoking prevalence also increased from 12.5% (1989)58 to 15.2% (1994),55 with the highest increase observed among young people (age 18– 24).55 There was also a move towards menthol and ‘light’ brands with mandated printed tar and nicotine levels on tobacco packaging.60 As of 1993, menthol tobacco comprised 29% of Singapore’s tobacco market.59

Market data after 1994 indicate that the menthol tobacco market in Singapore has grown. In a 2001 study (ERC Group data) in 56 countries, menthol tobacco comprised 22% of Singapore’s total tobacco market,61 and in a 2010 study (AC Nielsen data) in 52 countries, menthol tobacco comprised 48% of Singapore’s total tobacco market, making it the second largest menthol tobacco market (in terms of share) in the study.12 According to Euromonitor data, in 2011–2016, Singapore’s menthol tobacco market was 48% and is forecasted to stay this size in 2018–2021. As of 2013–2016, the top menthol brands in Singapore were Marlboro Lights Menthol (11% share; the 2nd top brand after Marlboro) and Marlboro Menthol (5%). Other popular menthol brands were line extensions from other popular brands (e.g. Viceroy, Pall Mall). Virginia Slims and Salem had relatively small shares in 2013–2016 (0.9% and 1.7% respectively).1 Put together, these data suggest that PM’s efforts to target young Singaporeans with light and menthol tobacco products may have started to pay off in the mid 1990’s, mainly via Marlboro line extensions.55

DISCUSSION

We found that menthol cigarettes became popular among young Singaporeans in the early 1980’s. This was partly because of awareness of the health effects of smoking prompted young people to switch to mentholated tobacco, which they perceived as milder and less unhealthy. As Singapore’s menthol tobacco market grew in 1983–1987, smoking rates in young adults increased even though they decreased in the overall population. PM, carefully researched the needs and lifestyles of young Singaporeans and developed new menthol brands such as Alpine and California to attract young people and starter smokers.

Tobacco companies have a well-established history of using menthol to encourage youth smoking in Western13 and Asian62, 63 countries. Decades earlier, tobacco industry internal research showed menthol has a cooling, anesthetic effect which masks the harshness of tobacco.64 This makes it easier initiate smoking and gives the misleading impression that menthol cigarettes are ‘healthier’,12 even though they are at least as harmful as non-menthol cigarettes.61 Tobacco companies also knew that menthol interacts with nicotine, making it more addictive,65 so those who initiate with menthol cigarettes are more likely to become established smokers and more addicted to nicotine.12, 66 Tobacco companies carefully researched the psychographic characteristics of young adults67 to target brands to different groups,68 urban youth subcultures,69 and young women.14

Recent data suggests that menthol cigarettes, or similar product innovations, remain key to industry recruiting and retaining young smokers in Singapore. As of 2016, menthol tobacco comprised almost half of Singapore’s tobacco market. There was also a growth in tobacco products with flavor capsules, from a 0.5% market share (2011–2014) to 2.2% (2015–2016); this is expected to increase to 3.0% in 2018–2021.1 In Singapore, tobacco companies are diversifying their top brands with menthol or mint-flavored line extensions, with products such as ‘Marlboro Mint Flare’ and ‘Camel Extra Cooling Menthol’.1 These strategies circumvent Singapore’s strict tobacco regulations, promote brand loyalty, and generate interest among young people. A 2015 focus group study with Singaporean youth smokers (age 15–29) indicated that mentholated and flavored tobacco products tempt them into initiating smoking, and that their cooling sensation feeds perceptions that these cigarettes are safer.10

Singapore set a target back in 1986 to become a ‘Nation of Non-Smokers,’70 and currently aims to reduce smoking prevalence to below 10% by 2020.6 Though Singapore has implemented strict advertising restrictions, tobacco companies have used creative strategies to circumvent them.35 Tobacco companies used menthol, innovative product features, and attractive packaging and advertising concepts to target young Singaporeans. While Singapore’s advertising policies made it difficult to launch new menthol brands, tobacco companies were eventually able to grow the menthol market using line extensions of existing brands. Moving forward, Singapore should implement interventions that address these marketing tactics. Banning the sale of menthol and flavored tobacco products, as has been done in Turkey, Ethiopia, the European Union and parts of Canada,12 is key to making tobacco products less appealing and addictive to youth. Eliminating menthol-related descriptors and packaging features (e.g. words such as ‘minty’ or ‘fresh,’ attractive blue/green colors) would help correct misperceptions these products are safer. Plain packaging, which has been implemented in Australia, the UK and France, would effectively eliminate all of these features.

It is also important to understand how tobacco companies target young adult smokers to develop more tailored anti-tobacco interventions. In Singapore, little is known about how psychographic characteristics affect health-related behavior. Yet the tobacco companies conducted detailed psychographic studies on young Singaporeans as early as the 1980’s to guide marketing efforts. Research in the USA has shown high smoking rates within certain youth subcultures, and that anti-tobacco interventions targeted to peer crowds, such as ‘hipsters’,71 or ‘partiers’,72 show promise in reducing smoking rates. In Singapore, more research is needed in to understand the role of psychographic profiling and its potential applications to improve tobacco control programs.

Limitations

The Truth Tobacco Industry Documents Library, is an incomplete collection of documents produced through litigation against tobacco companies. There was little information on the marketing of menthol products (including Salem) in Singapore by RJR, and no information on events after 1994. To address this limitation, data on the menthol tobacco market in Singapore was sourced from Euromonitor and the literature, and trend data on smoking prevalence in Singapore was obtained from the Singapore National Health Survey. Smoking prevalence trend data broken down by age group was only available for 1998–2010. Due to Singapore’s print and mass media tobacco advertising ban in 1971, we were unable to obtain images of cigarette adverts from print media (e.g. magazine archives), although we found black and white images of advertising concepts (to be used on tobacco packaging or in point of sale promotions) in the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents Library.

Conclusion

In Singapore’s restrictive environment since the 1980’s, menthol tobacco has been important for the tobacco industry to attract young smokers. As of February 2018, tobacco companies continue to aggressively market menthol and flavored capsule tobacco products, using colors and descriptors that appeal to young people and give the impression of safety. An important part of preventing smoking among young Singaporeans will be to ban all menthol and flavored tobacco products, and all colors, descriptors and packaging features related to these products.

Implications & Contribution.

Using internal tobacco industry documents, this study shows how tobacco companies marketed menthol tobacco brands in Singapore to recruit starter smokers, utilizing perceptions of health and youth-oriented lifestyles. Since menthol products are a large segment of the tobacco market in Singapore, a ban would likely reduce rates of youth smoking.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Stella Bialous, Minji Kim and Shannon Watkins for their helpful feedback.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute (grant R01CA 087472). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript; the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

We have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Euromonitor International. Passport: Cigarettes in Singapore 2017. July Report No.

- 2.Tan AS, Arulanandam S, Chng CY, Vaithinathan R. Overview of legislation and tobacco control in Singapore. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2000;4(11):1002–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lian T, Dorotheo U. The ASEAN Tobacco Control Atlas, 2nd edition. Bangkok: Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance,, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singapore Ministry of Health. Disease burden 2017 [Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/statistics/Health_Facts_Singapore/Disease_Burden.html. [Date accessed: 2017 September 16].

- 5.Singapore Health Promotion Board. Health Factsheet: World No Tobacco Day information paper Singapore: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Euromonitor International. Passport: Tobacco in Singapore 2017. July Report No.

- 7.About 80% of smokers hooked before they turn 21 [press release]. May 31 2012.

- 8.World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic country profile: Singapore: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smoking trend: question no. 291 [press release]. 2010.

- 10.Subramaniam M, Shahwan S, Fauziana R, Satghare P, Picco L, Vaingankar JA, et al. Perspectives on Smoking Initiation and Maintenance: A Qualitative Exploration among Singapore Youth. International journal of environmental research and public health 2015;12(8):8956–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agaku IT, Omaduvie UT, Filippidis FT, Vardavas CI. Cigarette design and marketing features are associated with increased smoking susceptibility and perception of reduced harm among smokers in 27 EU countries. Tob Control 2015;24(e4):e233–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation. Advisory note: banning menthol in tobacco products Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreslake JM, Wayne GF, Alpert HR, Koh HK, Connolly GN. Tobacco industry control of menthol in cigarettes and targeting of adolescents and young adults. American journal of public health 2008;98(9):1685–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson SJ. Marketing of menthol cigarettes and consumer perceptions: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control 2011;20 Suppl 2:ii20–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malone RE, Balbach ED. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? Tob Control 2000;9(3):334–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill MR. Archival strategies and techniques: Sage Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson SJ, Dewhirst T, Ling PM. Every document and picture tells a story: using internal corporate document reviews, semiotics, and content analysis to assess tobacco advertising. Tob Control 2006;15(3):254–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Survey Research Singapore, Singapore Tobacco Company, Basic Smoking Attitudes & Brand Image Exploratory Research: A Report on 10 Group Discussions conducted in Singapore in September/October, 1972, Sep-Oct, 1972, British American Tobacco Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/ffkj0224.

- 20.Survey Research Singapore, Singapore Tobacco Company, Medium Priced Low Delivery Brand Exploratory Name Research, November, 1972, British American Tobacco Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/hfmj0224.

- 21.Jilla JH, Philip Morris Asia, Letter to Ms. Cathy Leiber re the Alpine story, May 25, 1989, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/rpnd0110.

- 22.Tcheng J, Philip Morris International, Menthol trend - Asia, February 28, 1986, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/fjfy0038.

- 23.Butson E, Philip Morris International, Project Byzantium, August 16, 1985, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/nzhw0172.

- 24.Tobacco International Magazine, Salem sales booming in Far Eastern countries, February 22, 1985, British American Tobacco Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/nphh0200.

- 25.Schmidt P, Philip Morris Asia, Letter to Distribution re Alpine Project: Landor brief, April 24, 1987, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/tnvm0113.

- 26.Reynolds RJ, 1988 consumer research summaries: annual report, 1988, RJ Reynolds Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/xrgg0190.

- 27.Consumer Probe, Philip Morris Asia, Project Marlboro/Salem - Management Report based on 12 focus group discussions in Singapore, January/February, 1987, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/xnvm0113.

- 28.Norsearch International, Philip Morris Asia, Singapore Market Study: Pilot Test Results, August, 1985, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/yqxw0116.

- 29.Philip Morris Asia, Letter to J. Jilla re Singapore GCS 1987, March 28, 1988, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/xrnd0110.

- 30.Philip Morris International, Market research seminar September 1986, volume IV, September, 1986, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/qnlv0145.

- 31.Philip Morris International, Five year plan 1986–1990, 1986, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/mmxn0085.

- 32.Philip Morris, New product proposal, November 25, 1984, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/jqhy0082.

- 33.Philip Morris Asia, Project proposal: Singapore - Project Suzie, March 8, 1984, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/jlmy0082.

- 34.Unknown author, No title, August, 1987, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/qxmd0110.

- 35.Assunta M, Chapman S. “The world’s most hostile environment”: how the tobacco industry circumvented Singapore’s advertising ban. Tob Control 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii51–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan P, Consumer Probe, Letter to Jeremy Jilla re Alpine evaluation - J. 1885/Singapore, October 17, 1988, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/knvm0113.

- 37.Unknown author, The Alpine story, 1982, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/hjcd0116.

- 38.Philip Morris, New product introduction: Virginia Slims Lights, December, 1984, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/prmy0043.

- 39.Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Connolly GN. Designing cigarettes for women: new findings from the tobacco industry documents. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2005;100(6):837–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dewhirst T, Lee WB, Fong GT, Ling PM. Exporting an Inherently Harmful Product: The Marketing of Virginia Slims Cigarettes in the United States, Japan, and Korea. Journal of business ethics : JBE 2016;139(1):161–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tso D, Philip Morris Asia, Singapore - new brands, July 15, 1985, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/fynn0105.

- 42.PM Asia Marketing Research Department, Letter to J. Jilla re Singapore GCS 1988, December, 1988, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/nppd0110.

- 43.Unknown author, No title, February, 1989, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/phbm0113.

- 44.Tye D, Philip Morris Asia, Fax to R.L. Snyder re Asian weekly highlights - W/E/7/4, July 8, 1986, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/lhhh0004.

- 45.Philip Morris, Project Byzantium, 1986, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/kmyc0127.

- 46.Jilla JH, Philip Morris Asia, Letter to Mr. John J. Feenie, April 28, 1988, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/fqnd0110.

- 47.Philip Morris Asia, New product launch sheet, September 15, 1987, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/zrnd0110.

- 48.Tcheng J, Letter to Elizabeth Butson re Project Byzantium - Singapore, May 29, 1987, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/lnby0119.

- 49.Tcheng J, Philip Morris International, Email to Skip Long re Project Byzantium brief, June 16, 1986, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/fgxw0172.

- 50.Butson E, Philip Morris International, California, May 2, 1988, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/zpnd0110.

- 51.McCullagh L, Letter to William Webb re Byzantium, January 22, 1988, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/jhbn0038.

- 52.Myracle J, Letter to Elizabeth Butson re Project Byzantium scented tear tape, September 25, 1987, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/nzyw0172.

- 53.Webb W, Letter to Elizabeth Butson re Project Byzantium, October 19, 1987, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/xmxn0038.

- 54.Philip Morris Asia, Three year plan, December, 1993, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/gxnn0071.

- 55.PM Asia Marketing Research Department, General consumer tracking study Singapore 1994, August, 1994, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/jjkn0122.

- 56.Jilla JH, Philip Morris Asia, Parliament vs Chesterfield cross-license, May 31, 1989, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/shbm0113.

- 57.Philip Morris International, PM International 1987 – 1991 business plan, 1987, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/tjpw0172.

- 58.Unknown author, Singapore GCS, 1989, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/mhbm0113.

- 59.PM Asia, Pan-Asia menthol review, September, 1993, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/pnhd0073.

- 60.Tan P, Consumer Probe, Letter to Alison Koh re GCS ‘90 - top lines, September 24, 1990, Philip Morris Records, https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/yxld0110.

- 61.Giovino GA, Sidney S, Gfroerer JC, O’Malley PM, Allen JA, Richter PA, et al. Epidemiology of menthol cigarette use. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2004;6(Suppl 1):S67–S81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Assunta M, Chapman S. A “clean cigarette” for a clean nation: a case study of Salem Pianissimo in Japan. Tob Control 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii58–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alechnowicz K, Chapman S. The Philippine tobacco industry: “the strongest tobacco lobby in Asia”. Tob Control 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii71–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anderson SJ. Menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation behaviour: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control 2011;20 Suppl 2:ii49–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ferris Wayne G, Connolly GN. Application, function, and effects of menthol in cigarettes: a survey of tobacco industry documents. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 2004;6 Suppl 1:S43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nonnemaker J, Hersey J, Homsi G, Busey A, Allen J, Vallone D. Initiation with menthol cigarettes and youth smoking uptake. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2013;108(1):171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kreslake JM, Wayne GF, Connolly GN. The menthol smoker: tobacco industry research on consumer sensory perception of menthol cigarettes and its role in smoking behavior. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 2008;10(4):705–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Using tobacco-industry marketing research to design more effective tobacco-control campaigns. Jama 2002;287(22):2983–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hendlin Y, Anderson SJ, Glantz SA. ‘Acceptable rebellion’: marketing hipster aesthetics to sell Camel cigarettes in the US. Tob Control 2010;19(3):213–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Emmanuel SC, Phe A, Chen AJ. The impact of the anti-smoking campaign in Singapore. Singapore medical journal 1988;29(3):233–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ling PM, Lee YO, Hong J, Neilands TB, Jordan JW, Glantz SA. Social branding to decrease smoking among young adults in bars. American journal of public health 2014;104(4):751–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fallin A, Neilands TB, Jordan JW, Hong JS, Ling PM. Wreaking “havoc” on smoking: social branding to reach young adult “partiers” in Oklahoma. American journal of preventive medicine 2015;48(1 Suppl 1):S78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]