Summary

Aims

Ischemic postconditioning (IPostC) has been proved to have neuroprotective effects for cerebral ischemia, but the underlying mechanism remains elusive. This study aimed at validating the neuroprotective effects of IPostC and investigating whether the neuroprotection of IPostC is associated with matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) and the extracellular matrix proteins, laminin and fibronectin, following cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats.

Methods

The rats in middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) group underwent MCAO and reperfusion, and the animals in MCAO + IPostC group were treated by occluding bilateral common carotid arteries for 10 seconds and then reperfusing for 10 seconds for five episodes at the beginning of MCAO. Apoptosis was detected with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling staining. The expression of MMP9, laminin, and fibronectin was measured with immunofluorescence and enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay.

Results

IPostC reduced brain edema and infarct volume and improved the neurological function. Furthermore, IPostC decreased cell apoptosis compared with the MCAO group. Compared to the MCAO group, IPostC treatment reduced MMP9 expression. Moreover, the results showed that the expression of laminin and fibronectin significantly increased in the MCAO + IPostC group compared to the MCAO group.

Conclusion

These findings indicated that diminishment of MMP9 expression and the attenuation of degradation of laminin and fibronectin may be involved in the protective mechanisms of postconditioning against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Keywords: Fibronectin, Laminin, MMP9, Neuroprotection, Postconditioning, Stroke

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of death and long‐term disability. Although extensive researches for stroke treatment have been performed for several decades, neurologists remain helpless in protecting and recovering neurons from ischemic insults. A large body of studies showed that ischemic preconditioning (IPC) can limit the damage induced by subsequent ischemia/reperfusion in different organs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. The concept of IPC was introduced in the late 1980s by the research group of Murry as well as by Miyazaki and Zipes 7, 8. Ischemic preconditioning is a vigorous and intrinsic phenomenon. However, because of the unpredictable property of disease, IPC is limited in practice as a treatment method. On the other hand, ischemic postconditioning (IPostC), defined as application of alternating brief periods of ischemia and reperfusion at the immediate onset of reperfusion, can confer protection for the ischemia/reperfusion 9 and thus is more feasible for clinical application. Recently, some studies showed that IPostC can protect against the cerebral ischemia/reperfusion damage 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, while the underlying mechanism is not well understood.

There is evidence, in both humans and animal stroke models, that matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), specifically MMP9, play important roles in pathophysiology of cerebral ischemic injury. MMP9 is involved in the degradation of the extracellular matrix and proteolysis of basal lamina, a component known to be an inherent contributor to the blood brain barrier 20, 21, 22, 23, 24. The extracellular matrix is implicated in a range of processes, such as cerebral development, cell survival, and regeneration. Laminin and fibronectin, the substrates of MMP9, are extracellular matrix glycoproteins with multiple functions in the central nervous system, including maintenance of the blood–brain barrier and regulation of cell adhesion, migration, apoptosis, and differentiation 25, 26, 27. In addition, laminin peptide and fibronectin can ameliorate brain injury by inhibiting leukocyte accumulation in animals after cerebral ischemia 28, 29.

In this study, we investigated the effects of IPostC on brain injuries following cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats with middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), an animal model closely mimics human ischemic stroke. Results showed that IPostC reduced brain edema, infarct volume, and cell apoptosis and improved the neurological function. The assessment of the expression of laminin and fibronectin in MCAO group and the MCAO + IPostC group by Western blot and enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) demonstrated that the expression level of laminin and fibronectin in the MCAO + IPostC group was higher, while MMP9 lower, in comparison with that in MCAO rats. These results suggested that IPostC may protect focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through diminishing MMP9 expression and attenuating loss of laminin and fibronectin.

Materials and Methods

Animal Model

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Capital Medical University and in accordance with the principles outlined in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Temporary focal ischemia was induced in male Sprague‐Dawley rats weighing 280–300 g using the intraluminal vascular occlusion method as previously described 30. The rats were randomly assigned into four groups: sham‐operated group, IPostC‐alone group (rat bilateral common carotid arteries were reperfused for 10 seconds and reoccluded for 10 seconds for five episodes, without cerebral ischemia/reperfusion), MCAO group (rats only suffered from MCAO for 2 h followed by reperfusion, without postconditioning), and MCAO + IPostC group (rats suffered from MCAO for 2 h followed by reperfusion, and bilateral common carotid arteries were reperfused for 10 seconds and reoccluded for 10 seconds for five episodes at the beginning of MCAO). To ensure the occurrence of ischemia by MCAO, regional cerebral blood flow was monitored using laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF, PeriFlux System 5000; Perimed, Stockholm, Sweden) in the following coordinates: 0.5 mm anterior and 5.0 mm lateral from the bregma and recorded at 16 different time points: at baseline (before MCAO), 0, 30, and 90 min after MCAO, at the beginning of reperfusion, at the beginning of common carotid artery occlusion, and reperfusion in all five episodes, and at 30 min after IPostC procedure. Rectal temperature was controlled at 37.0°C during and after surgery with a temperature‐regulated heating pad. Mean artery blood pressure (MABP) was monitored through an apparatus (MP100A‐CE; BIOPAC Systems, Inc., CA, USA). The right femoral artery was catheterized for continuous blood pressure monitoring and periodic blood sampling for arterial gas level (ABBOTTi‐STAT, i‐STAT Corporation, East Windsor, NJ, USA). The animals underwent right MCAO for 120 min and then reperfusion for 4, 24, and 72 h, respectively. All animals were housed in an air‐conditioned room at 25 ± 1°C after recovering from anesthesia.

Determination of Infarct Volume and Edema Volume

The animals were euthanized at 24 h after reperfusion in a carbon dioxide chamber, and the brains were quickly removed and sectioned into six consecutive coronal slices of 2 mm thickness. The slices were stained by immersing into 2% of 2, 3, 5‐triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) for 30 min at 37°C and then fixed with 8% of formalin. The border between infarcted and noninfarcted tissue was outlined with an image analysis system, and the area of infarction was measured by subtracting the area of the nonlesioned ipsilateral hemisphere from that of the contralateral hemisphere. The volume of infarction was calculated by integration of the lesion areas. Edema was determined by subtracting the total volume of the nonischemic hemisphere from that of the ischemic hemisphere 31.

Behavioral Testing

Neurological functional deficits were scored at 24 and 72 h after reperfusion, in a blind fashion. Two tests were used to evaluate neurological function according to the studies reported previously: the postural reflex test, developed by Bederson et al. 32 to examine upper body posture while the animal is suspended by the tail; and the forelimb placing test, developed by De Ryck et al. 33 to examine sensorimotor integration in forelimb placing responses to visual, tactile, and proprioceptive stimuli. Neurological functions were graded on a scale from 0 to 12 (normal score, 0; maximal score, 12). Rats with convulsions or sustained disturbances of consciousness were excluded from the study; most of these cases were proved to have subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to suture‐induced rupture of the internal carotid artery.

Terminal Transferase‐Mediated dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) Staining

Terminal Transferase‐Mediated dUTP Nick End Labeling staining was performed using an in situ cell death detection kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science, South San Francisco, CA, USA). The paraffin‐embedded coronal sections were de‐paraffinized and rehydrated and then treated with 10 μg/mL proteinase K for 30 min at room temperature. Sections were incubated with reaction buffer containing enzyme at 37°C for 1 h in the dark. After washing with PBS, sections were treated with peroxidase for 30 min at 37°C and subsequently developed color in peroxidase substrate. The nuclei were slightly counterstained with hematoxylin. The positive cells and total cells were counted on three fields at ×400 magnifications by a blinded technician. The result was presented as a ratio of TUNEL‐positive cell number to the total cell number.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Formalin‐fixed/paraffin‐embedded sections (4 μm) were de‐paraffinized in dimethyl benzene and rehydrated through graded alcohols. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min. Sections were incubated in sodium citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH 6.0) for 15 min in a microwave oven. After cooling to room temperature, slides were washed in PBS and immersed in normal goat serum (Maxin, Fuzhou, China) for 30 min. Slides were incubated with rabbit anti‐MMP9 polyclonal antibody (diluted 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), rabbit polyclonal anti‐laminin antibody (diluted 1:25; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), or rabbit polyclonal anti‐fibronectin antibody (diluted 1:40; Abcam) in a humidified chamber at 4°C overnight. After washing, slides were incubated with goat anti‐rabbit secondary antibody (TRITC‐conjugated) (diluted 1:200; Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories Inc, West Grove, PA, USA) for 30 min. Optical density of laminin and fibronectin immunoreactivity in the ischemic and nonischemic cerebral cortex areas of the MCA territory was detected by an Image Analyzer (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) and was calculated using the following equation: ‐log (optical density of detected cerebral cortex/optical density of background). The background density was detected on the sections that underwent identical process but without the primary antibody.

ELISA

The cerebral cortex was removed at 4, 24, and 72 h after reperfusion. The lysis buffer was used as previously 34. The tissues were homogenized and centrifuged at 12,800 g for 30 min at 4°C, and then the supernatant was collected. The samples were added in triplicate in wells, 0.1 μg/well, and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS, coated wells were blocked in PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.05% Tween‐20 for 1 h and then incubated with rabbit anti‐MMP9 polyclonal antibody (diluted 1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), rabbit anti‐laminin polyclonal antibody (diluted 1:2000, Abcam), rabbit anti‐fibronectin polyclonal antibody (diluted 1:2000, Abcam), or rabbit anti‐actin polyclonal antibody (1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) overnight at 4°C. Antibody binding was visualized using a horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated goat anti‐rabbit secondary antibody (diluted 1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.). Color was developed by tetramethylbenzidine (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) as a substrate, and reaction was stopped by addition of 50 μL of 2 M H2SO4. Optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo multiskan Mk3; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The protein level was expressed as the percentage of OD of protein of interest/OD of actin.

Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as mean ± standard deviations. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 11.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The significance of difference between means was assessed by Student's t‐test (single comparisons) or by one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc Scheffe's tests, with P < 0.05 being considered statistically significant.

Results

IPostC Reduces Infarct Volume and Brain Edema

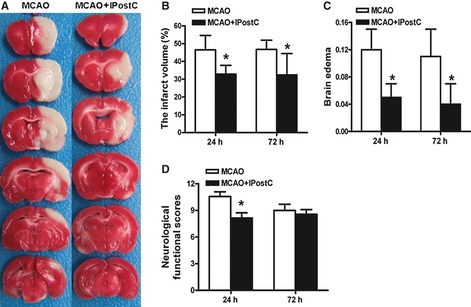

To confirm the achievement of IPostC‐induced neuroprotection, infarct volume was measured based on the regional loss of TTC staining in brain sections at 24 h and 72 h after reperfusion. In the MCAO group, the infarct volume was large, which included cortex, subcortex, corpus striatum, and hippocampus (Figure 1A). IPostC resulted in a reduction in infarct size at both time points, as compared to the MCAO group (32.9 ± 4.9% vs. 46.5 ± 8.1% at 24 h; 32.4 ± 12.0% vs. 46.8 ± 5.2% at 72 h, respectively, P < 0.05) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

IPostC rats have significantly reduced ischemic injury compared with middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) rats. (A) Representative brain slices with infarcts stained by TTC in the MCAO group and MCAO + IPostC group at 24 h after reperfusion. (B) Statistical analysis of the percentage of infarct volume of contralateral hemisphere. (C) Statistical analysis of brain edema in the MCAO group and MCAO + IPostC group at 24 and 72 h after reperfusion. (D) The neurological functional outcome of the MCAO and MCAO + IPostC groups at 24 and 72 h after reperfusion. n = 6. *P < 0.05 versus MCAO.

The brain edema was determined on the same sample as above. The result showed that the percentage of brain edema was significantly decreased in MCAO + IPostC group compared with the MCAO group (0.05 ± 0.02 vs. 0.12 ± 0.03 at 24 h; 0.04 ± 0.03 vs. 0.11 ± 0.04 at 72 h, respectively, P < 0.05) (Figure 1C). In the sham‐operated and IPostC‐alone groups, there was no infracted zone and no edema either (data not shown).

IPostC Improves Neurological Functional Outcome

Rectal temperature, MABP, and blood gas were monitored for all groups. The results showed no significant difference in all the variables among groups (data not shown). The behavioral functional scores of the rats in different groups were determined at 24 and 72 h after MCAO and reperfusion. The neurological function was normal in the sham‐operated and IPostC‐alone groups, but deficient in MCAO group (10.6 ± 0.5). These ischemia and reperfusion‐induced neurological deficits were improved significantly in MCAO + IPostC group (8.1 ± 0.6) at 24 h after reperfusion (P < 0.05, Figure 1D). However, there was no significant difference between the MCAO group (9.0 ± 0.7) and MCAO + IPostC group (8.6 ± 0.5) in the behavioral functional scores at 72 h after reperfusion (P > 0.05, Figure 1D).

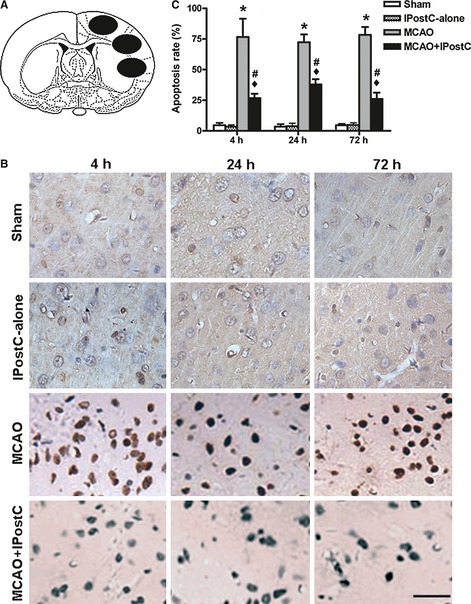

IPostC Decreases TUNEL‐Staining Cells

To evaluate cerebral tissue apoptosis, TUNEL‐staining cells in sham‐operated group, IPostC‐alone group, MCAO group, and MCAO + IPostC group were quantified at 4, 24, and 72 h after reperfusion (Figure 2A). The results showed that there was no significant difference between the IPostC‐alone group and the sham‐operated group (P > 0.05, Figure 2B,C). The IPostC significantly decreased the TUNEL‐staining cells compared with the MCAO group at the three time points examined (P < 0.05, Figure 2B,C). Similar to sham‐operated group, IPostC‐alone group did not induce cell apoptosis. To save animals, we therefore did not include this group in the under experiments to detect the expression of MMP9, laminin, and fibronectin.

Figure 2.

IPostC decreases the number of TUNEL‐positive cells. (A) The three black ovals indicate the regions selected for quantifying TUNEL‐staining cells. The mean of apoptosis rate of the three black ovals was calculated. (B) Representative sections stained for TUNEL at different times after reperfusion in sham‐operated, IPostC‐alone, middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), and MCAO + IPostC groups. Bar = 50 μm. (C) The percentage of TUNEL‐positive cells in the selected brain regions in different groups at different times after reperfusion. IPostC significantly reduced the number of TUNEL‐positive cells at 4, 24, and 72 h of reperfusion. n = 5. *P < 0.01 versus sham or IPostC‐alone; ♦ P < 0.01 versus sham or IPostC‐alone; # P < 0.05 versus MCAO.

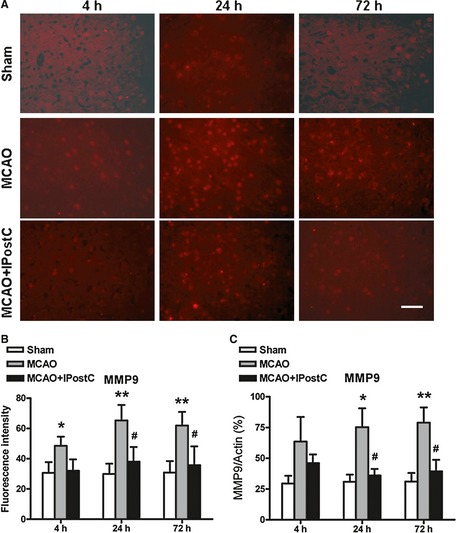

IPostC Diminishes MMP9 Expression and Attenuates Loss of Laminin and Fibronectin

To determine the effects of IPostC on the expression of MMP9, laminin, and fibronectin, the ipsilateral brain tissues of the sham‐operated group, MCAO group, and MCAO + IPostC group were obtained at 4, 24, and 72 h after the reperfusion. Expression level of MMP9, laminin, and fibronectin was assessed with immunofluorescence staining and ELISA.

The result showed that the fluorescence intensity of MMP9 in the MCAO + IPostC group was declined compared with that of the MCAO group (38.1 ± 9.7 vs. 65.3 ± 10.2 at 24 h after reperfusion, and 35.8 ± 12.4 vs. 61.9 ± 9.0 at 72 h after reperfusion, respectively. P < 0.05, Figure 3A,B). As shown in Figure 3(C), the result from assessment by ELISA is consistent with this result, and the expression of MMP9 was significantly decreased in the rats of MCAO + IPostC group at 24 and 72 h after reperfusion compared with that of the MCAO group (36.1 ± 5.3% vs. 75.3 ± 15.3% at 24 h; 39.4 ± 9.4% vs. 78.9 ± 12.4% at 72 h, respectively. P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

IPostC decreases MMP9 expression in brain after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). (A) MMP9 stained by immunofluorescence (red) in the ischemic penumbra of the MCAO group and MCAO + IPostC group at different time points. (B) Quantitative evaluation of fluorescence intensity of MMP9 in the penumbra for different groups. Bar = 50 μm. (C) The expression of MMP9 assessed by ELISA method. n = 5. *P < 0.05 versus sham; **P < 0.01 versus sham; # P < 0.05 versus MCAO.

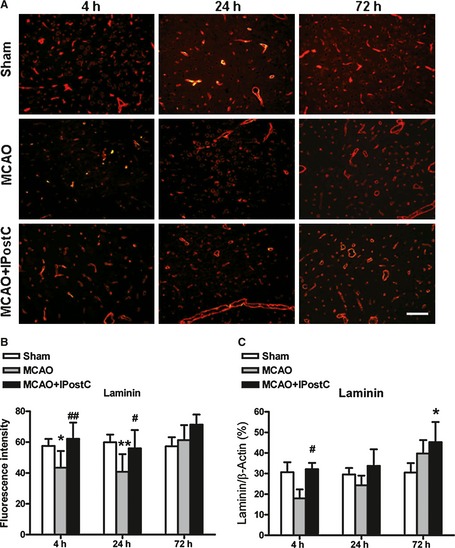

The expression of laminin in different groups is presented in Figure 4. In contrast to MMP‐9, the MCAO and 24 h reperfusion in the MCAO group rats induced a dramatic decrease in the laminin fluorescence intensity compared with that of the sham‐operated group (P < 0.01). Of interest, the laminin fluorescence intensity in ipsilateral cerebral tissue of MCAO + IPostC group at 4 and 24 h after reperfusion was clearly stronger than that in the MCAO group (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively, Figure 4A,B). Determination by ELISA showed a likewise result: the expression of laminin was significantly increased in the rats of MCAO + IPostC group (32.1 ± 3.1%) at 4 h after reperfusion compared with that of the MCAO group (18.0 ± 4.3%) (P < 0.05, Figure 4C). Of notice, both approaches revealed a recovery, or even an increase in laminin expression in MCAO group and MCAO + IPostC group at 72 h, as compared with sham group.

Figure 4.

The effects of IPostC on laminin expression in brain after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). (A) Immunofluorescence staining for laminin (red) in the penumbra of the sham‐operated group, MCAO group and MCAO + IPostC group at different time points. (B) Quantitative evaluation of fluorescence intensity of laminin in the penumbra for different groups. Bar = 100 μm. (C) The expression of laminin assessed by ELISA method. n = 5. *P < 0.05 versus sham; # P < 0.05 versus MCAO; ## P < 0.01 versus MCAO.

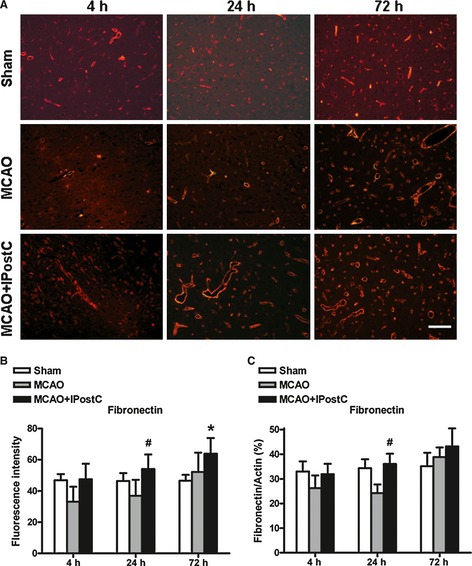

Expressions of fibronectin in different groups exhibit a similar pattern to laminin. Fluorescence intensity analysis indicated that, in MCAO animals, fibronectin decreased at 4 h and recovered at 24 and 72 h (Figure 5A,B). IPostC prevented postischemic change in the expression of fibronectin (Figure 5A,B). There was significant difference in fibronectin fluorescence intensity between the MCAO group (36.9 ± 10.3) and MCAO + IPostC group (54.1 ± 9.3) at 24 h after reperfusion (P < 0.05, Figure 5A,B). Similarly, the expression of fibronectin determined by ELISA was also significantly increased in the rats of MCAO + IPostC group (36.1 ± 4.2%) at 24 h after reperfusion compared with that of the MCAO group (24.3 ± 3.5%) (P < 0.05, Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

IPostC attenuates loss of fibronectin in brain after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of fibronectin (red) in the ischemic penumbra at 4, 24, and 72 h after MCAO. (B) Quantitative evaluation of fluorescence intensity of fibronectin in the penumbra at different time points for different groups. Bar = 100 μm. (C) The expression of fibronectin assessed by ELISA method. n = 5. *P < 0.05 versus sham; # P < 0.05 versus MCAO.

Discussion

In this study, we reported the effects of IPostC on infarct volumes, neurological function, and brain edema in rats on MCAO and reperfusion. We confirmed the neuroprotective effects of IPostC on brain injuries following cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats. IPostC is defined as giving short‐term nonfatal ischemia/reperfusion repeatedly, at the beginning of reperfusion, after a long‐term ischemia 35, 36. IPostC has more application potential in clinical treatments comparing with IPC. Recently, IPostC has been reported to reduce infarct volume after cardiac ischemia 9. In addition, a recent exciting clinical report demonstrated that postconditioning after coronary angioplasty, and stenting protects the human heart during acute myocardial infarction 37. Laskey studied the IPostC treatment after the catheter intervention therapy in seven acute myocardial infarction patients and found that the ECG in the treated group is significantly improved compared with the untreated group 38. These results suggest a promising prospect for IPostC application in clinic.

Our study demonstrated that IPostC can reduce infarct volume and brain edema and improves the neurological functional deficits induced by transient MCAO and reperfusion in rat model. On the other hand, the body temperature, mean arterial pressure, and blood gas were investigated at different time points in MCAO group and MCAO + IPostC group, with no difference being observed between groups.

The neurological functional deficits of the rats in MCAO + IPostC group were improved significantly at 24 h after reperfusion, as compared with the MCAO group, indicating that the neurological function was improved by the IPostC treatment. On the other hand, there was no significant difference between the two groups at 72 h after reperfusion, implying a delayed spontaneous functional recovery ability of the rats. Considerable efforts have been made to explore the mechanism for IPostC. Previous studies have indicated that (1) IPostC seems to involve the upregulation of Bcl‐2 and heat‐shock protein 70 expression and downregulation of cytochrome C release to the cytosol, Bax translocation to the mitochondria, and caspase‐3 activity 11, (2) Akt activity is also reported to contribute to postconditioning's protection 13, 14, 19, (3) furthermore, increases in εPKC activity, a survival‐promoting pathway, and reductions in MAPK and δPKC activity correlate with postconditioning's protection 13, and (4) The protective effect of IPostC is closely related to the NO production following the increase in eNOS and iNOS expression and the suppressive effect of ET‐1 overproduction 39. Nonetheless, the mechanism underlying the IPostC is not fully understood in cerebral ischemia and reperfusion.

Extracellular matrix proteins laminin and fibronectin have been proved to be cleaved by MMPs 40, causing microvascular damage and cerebral edema 41, 42. In the present study, it was found that the brain edema diminished, while the laminin and fibronectin expression increased, in MCAO + IPostC group compared with the MCAO group, indicating a close relationship between neuroprotection of IPostC and the attenuation of blood brain barrier damage involving extracellular matrix proteins. These results suggest that inhibition of MMP9 may serve as at least one of the mechanisms, whereby IPostC protects against cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury via retaining laminin and fibronectin, and thus the vascular permeability.

In conclusion, our results suggest that IPostC may be a neuroprotective therapeutic method in ischemic brain injuries. In addition, the underlying protective mechanisms of IPostC may involve diminishment of MMP9 expression and the attenuation of ischemia‐induced degradation of laminin and fibronectin.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant no. 7111003) and the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 30770743, 30870854).

References

- 1. Liu YG, Downey JM. Ischemic preconditioning protects against infarction in rat‐heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 1992;263:H1107–H1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lott FD, Guo P, Toombs CF. Reduction in infarct size by ischemic preconditioning persists in a chronic rat model of myocardial ischemia‐reperfusion injury. Pharmacol 1996;52:113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kume M, Yamamoto Y, Saad S, et al. Ischemic preconditioning of the liver in rats: Implications of heat shock protein induction to increase tolerance of ischemia‐reperfusion injury. J Lab Clin Med 1996;128:251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee HT, Emala CW. Protective effects of renal ischemic preconditioning and adenosine pretreatment: Role of A(1) and A(3) receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2000;278:F380–F387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pajdo R, Brzozowski T, Konturek PC, et al. Ischemic preconditioning, the most effective gastroprotective intervention: Involvement of prostaglandins, nitric oxide, adenosine and sensory nerves. Eur J Pharmacol 2001;427:263–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jiang X, Shi E, Nakajima Y, Sato S. Postconditioning, a series of brief interruptions of early reperfusion, prevents neurologic injury after spinal cord ischemia. Ann Surg 2006;244:148–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: A delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation 1986;74:1124–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miyazaki T, Zipes DP. Protection against autonomic denervation following acute myocardial infarction by preconditioning ischemia. Circ Res 1989;64:437–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao ZQ, Corvera JS, Halkos ME, Kerendi F, Wang NP, Guyton RA, Vinten‐Johansen J. Inhibition of myocardial injury by ischemic postconditioning during reperfusion: Comparison with ischemic preconditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003;285:H579–H588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhao H, Sapolsky RM, Steinberg GK. Interrupting reperfusion as a stroke therapy: Ischemic postconditioning reduces infarct size after focal ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2006;26:1114–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xing B, Chen H, Zhang M, Zhao D, Jiang R, Liu X, Zhang S. Ischemic postconditioning inhibits apoptosis after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in the rat. Stroke 2008;39:2362–2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang JY, Shen J, Gao Q, et al. Ischemic postconditioning protects against global cerebral ischemia/reperfusion‐induced injury in rats. Stroke 2008;39:983–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gao X, Zhang H, Takahashi T, Hsieh J, Liao J, Steinberg GK, Zhao H. The Akt signaling pathway contributes to postconditioning's protection against stroke; the protection is associated with the MAPK and PKC pathways. J Neurochem 2008;105:943–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pignataro G, Meller R, Inoue K, et al. In vivo and in vitro characterization of a novel neuroprotective strategy for stroke: Ischemic postconditioning. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008;28:232–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ren C, Yan Z, Wei D, Gao X, Chen X, Zhao H. Limb remote ischemic postconditioning protects against focal ischemia in rats. Brain Res 2009;1288:88–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Robin E, Simerabet M, Hassoun SM, et al. Postconditioning in focal cerebral ischemia: Role of the mitochondrial ATP‐dependent potassium channel. Brain Res 2011;1375:137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yuan Y, Guo Q, Ye Z, Pingping X, Wang N, Song Z. Ischemic postconditioning protects brain from ischemia/reperfusion injury by attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress‐induced apoptosis through PI3K‐Akt pathway. Brain Res 2011;1367:85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhou C, Tu J, Zhang Q, et al. Delayed ischemic postconditioning protects hippocampal CA1 neurons by preserving mitochondrial integrity via Akt/GSK3β signaling. Neurochem Int 2011;59:749–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peng B, Guo QL, He ZJ, Ye Z, Yuan YJ, Wang N, Zhou J. Remote ischemic postconditioning protects the brain from global cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by up‐regulating endothelial nitric oxide synthase through the PI3K/Akt pathway. Brain Res 2012;1445:92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barr TL, Latour LL, Lee KY, et al. Blood‐brain barrier disruption in humans is independently associated with increased matrix metalloproteinase‐9. Stroke 2010;41:123–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leonardo CC, Pennypacker KR. Neuroinflammation and MMPs: Potential therapeutic targets in neonatal hypoxicischemic injury. J Neuroinflammation 2009;6:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mori T, Wang X, Aoki T, Lo EH. Downregulation of matrix metalloproteinase‐9 and attenuation of edema via inhibition of ERK mitogen activated protein kinase in traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2002;19:1411–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pfefferkorn T, Rosenberg GA. Closure of the blood‐brain barrier by matrix metalloproteinase inhibition reduces rtpa‐mediated mortality in cerebral ischemia with delayed reperfusion. Stroke 2003;34:2025–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosenberg GA, Yang Y. Vasogenic edema due to tight junction disruption by matrix metalloproteinases in cerebral ischemia. Neurosurg Focus 2007;22:E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sakai T, Johnson KJ, Murozono M, et al. Plasma fibronectin supports neuronal survival and reduces brain injury following transient focal cerebral ischemia but is not essential for skin‐wound healing and hemostasis. Nat Med 2001;7:324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang J, Milner R. Fibronectin promotes brain capillary endothelial cell survival and proliferation through alpha5beta1 and alphavbeta3 integrins via MAP kinase signalling. J Neurochem 2006;96:148–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yanqing Z, Yu‐Min L, Jian Q, Bao‐Guo X, Chuan‐Zhen L. Fibronectin and neuroprotective effect of granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor in focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Res 2006;1098:161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yanaka K, Camarata PJ, Spellman SR, Skubitz AP, Furcht LT, Low WC. Laminin peptide ameliorates brain injury by inhibiting leukocyte accumulation in a rat model of transient focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1997;17:605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yanaka K, Camarata PJ, Spellman SR. Synthetic fibronectin peptides and ischemic brain injury after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. J Neurosurg 1996;85:125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen J, Graham SH, Zhu RL, Simon RP. Stress proteins and tolerance to focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1996;16:566–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lin TN, He YY, Wu G, Khan M, Hsu CY. Effect of brain edema on infarct volume in a focal cerebral ischemia model in rats. Stroke 1993;24:117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bederson JB, Pitts LH, Tsuji M, Nishimura MC, Davis RL, Bartkowski H. Rat middle cerebral artery occlusion: Evaluation of the model and development of a neurologic examination. Stroke 1986;17:472–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. De Ryck M, Van Reempts J, Borgers M, Wauquier A, Janssen PA. Photochemical stroke model: Flunarizine prevents sensorimotor deficits after neocortical infarcts in rats. Stroke 1989;20:1383–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu X, Wang L, Zhao S, Ji X, Luo Y, Ling F. β‐Catenin overexpression in malignant glioma and its role in proliferation and apoptosis in glioblastma cells. Med Oncol 2011;28:608–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vinten‐Johansen J, Yellon DM, Opie LH. Postconditioning: A simple, clinically applicable procedure to improve revascularization in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2005;112:2085–2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fantinelli JC, Mosca SM. Comparative effects of ischemic pre and postconditioning on ischemia‐reperfusion injury in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR). Mol Cell Biochem 2007;296:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Staat P, Rioufol G, Piot C, et al. Postconditioning the human heart. Circulation 2005;112:2143–2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Laskey WK. Brief repetitive balloon occlusions enhance reperfusion during percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: A pilot study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2005;65:361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu X, Chen H, Zhan B, Xing B, Zhou J, Zhu H, Chen Z. Attenuation of reperfusion injury by renal ischemic postconditioning: The role of NO. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007;359:628–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mun‐Bryce S, Rosenberg GA. Matrix metalloproteinases in cerebrovascular disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1998;18:1163–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Montaner J, Alvarez‐Sabín J, Molina C, Anglés A, Abilleira S, Arenillas J, Monasterio J. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP‐9) expression is related to hemorrhagic transformation after cardioembolic stroke. Stroke 2001;32:2762–2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Horstmann S, Kalb P, Koziol J, Gardner H, Wagner S. Profiles of matrix metalloproteinases, their inhibitors, and laminin in stroke patients: Influence of different therapies. Stroke 2003;34:2165–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]