Summary

Tripterygium wilfordii Hook.f. (TWHF) has a long history as a Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) herb that aids in treating inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. The major bioactive component of TWHF is triptolide, which has been recognized to possess a broad spectrum of biological profiles including antiinflammatory, immunosuppressive, antifertility, and antitumor activities, as well as neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects. Limitation of triptolide, such as poor water solubility and severe systemic toxicity, has postponed clinical development and trials; however, the wide range of medicinal value of triptolide has been drawing intensive worldwide attention. In particular, triptolide has been shown to have significant effects on central nervous system (CNS) diseases, such as Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, spinal cord and brain injury, and multiple sclerosis. This review focuses on the potential therapeutic role of triptolide on CNS diseases, and discusses the structural features, potential modifications, and the other pharmacological activities of triptolide.

Keywords: CNS diseases, Neurodegenerative diseases, Neuroprotection, Triptolide

Introduction

Tripterygium wilfordii Hook.f. (TWHF), also named Lei Gong Teng in Chinese, which belongs to the Celastraceae family, is a woody vine native to Eastern and Southern China, Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. It is a representative Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) herb that has been used in treating inflammatory diseases for centuries 1, 2. More than 100 compounds have been isolated from this plant, including sesquiterpenes, diterpenes, triterpenes, and alkaloids. Among these, triptolide is the major active compound and the first diterpenoid triepoxide lactone identified by Kupchan et al. 3 from TWHF. Triptolide has been shown to possess a broad spectrum of biological profiles including antiinflammatory, immunosuppressive, antifertility, and antitumor activities, as well as neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects. As reported, triptolide contributes to the majority of the antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive activity of TWHF 4. However, limitations of this compound include poor water solubility and severe systemic toxicity that limits its clinical development. Despite these flaws, the wide medicinal value of triptolide has attracted worldwide attention. The pharmacological effects, structural modification, and structural‐activity relationship (SAR) have been reviewed recently 5, 6, 7. However, the bioactivity exhibited by triptolide on the central nervous system (CNS) has rarely been summarized because it was found to influence the function of both glial cells and neurons in the CNS. In the present review, we discuss the structural features and pharmacological activity of triptolide, and also discuss its potential therapeutic role in diseases of the CNS.

Structural Features and Modifications

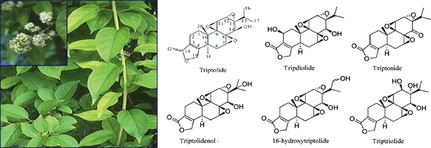

Triptolide was extracted from TWHF in 1972 together with two other novel diterpenoid triepoxides, tripdiolide and triptonide. Triptolide has been found in L‐1210 and P‐388 murine leukemias in vivo, and human KB oral cancer cells in vitro 3. The structure of triptolide is characterized by a C‐14‐hydroxyl group, three epoxy groups, and a lactone ring 6. In addition, several other natural triptolide analogues have been isolated from TWHF (Figure 1). Triptolide has been identified to be the principle active compound of extracts of TWHF. However, owing to its insolubility in water and severe toxicity, the application of triptolide in a clinical setting is limited. Thus, many studies have attempted to modify its structure to obtain derivatives with higher therapeutic effects and lower toxicity. Medicinal chemists have mainly focused on several groups according to the SAR of triptolide: (1) The C‐14‐hydroxyl group, which contributes to the antitumor bioactivity but also insolubility of triptolide; (2) The C‐12, 13‐epoxy group, which appears to be one of the important modification sites of triptolide due to its smaller steric impact compared to the other two epoxy groups of triptolide. It has also been shown that the epoxy groups are required to exhibit immunosuppressive and antiinflammatory activity 8, as well as antitumor activity; (3) the α,β‐unsaturated‐5‐membered‐lactone ring, which is considered a necessary active group 6; and (4) the C‐5, 6‐position, which has been modified to generate a series of triptolide derivatives. Among them, (5R)‐5‐hydroxytriptolide, termed LLDT‐8 (Figure 2), showed 122‐fold lower cytotoxicity in vitro and a 10‐fold lower acute toxicity in vivo compared to triptolide, with remaining antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive activity 9.

Figure 1.

The photograph of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook.f. and the structure of triptolide and its analogues.

Figure 2.

The structure of (5R)‐5‐hydroxytriptolide (LLDT‐8).

Nevertheless, the bioactivities of triptolide decreased after structural modification; however, derivatives showed enhanced water solubility and reduced toxicity compared to triptolide. Therefore, these modifications are potentially useful ways to develop prodrugs of triptolide, which could be easily converted to triptolide in vivo, and show slightly less toxicity and higher water solubility.

Bioactivity

Systemic Antiinflammatory and Immunosuppressive Activities

Antiinflammation and immunosuppression are recognized to be the core bioactivities of TWHF. Triptolide has been revealed to be responsible for the majority of this activity and has exhibited remarkable therapeutic effects on various animal models of human‐like autoimmune and inflammatory diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, spontaneous lupus nephritis, autoimmune uveoretinitis, and collagen‐induced arthritis 5, 6. Moreover, triptolide is also effective in the prevention of allograft rejection and graft‐versus‐host disease in both animals and humans 4.

Taken together, the antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive activities of triptolide are mainly mediated by the following mechanisms: (1) Suppressing differentiation, maturation, and trafficking of macrophages and dendritic cells, which play critical roles in inducing both immune response and immune tolerance by processing and presenting antigens to T cells and by producing a variety of inflammatory mediators 6, 10, 11; (2) Inhibiting T‐cell and B‐cell proliferation and activation, therefore interfering with cellular and humoral immunity 6; (3) Exerting inhibitory effects on a variety of proinflammatory cytokines and mediators, and on the expression of adhesion molecules by endothelial cells 4. Currently, proinflammatory cytokines and mediators have been found to be suppressed by triptolide including tumor necrosis factor‐α (TNFα), interleukin (IL)‐1, IL‐4, IL‐6, IL‐8, IL‐17, IL‐23, cyclooxygenase (COX)‐2, interferon (IFN)α, and prostaglandin (PG)E2 6, 12. In all cell types examined, triptolide inhibits nuclear factor κB (NFκB) transcriptional activation at a unique step in the nucleus after binding to DNA 13.

Antitumor Activity

In addition to the antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive activity, triptolide has been recognized to exert an antitumor effect in a broad spectrum of tumor cells 5. Initial research on its antitumor activity can be traced back to early 1972 when Kupchan et al. 3 first reported that the novel extract from TWHF had an antileukemic effect and a unique chemical structure.

Triptolide has been reported to induce apoptosis of various tumor cells originating from different tissues including the blood, lung, brain, liver, stomach, colon, gall ducts, pancreas, thyroid, kidney, breast, and ovary 6, 14. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanism associated with triptolide‐induced apoptosis in different tumor cells seems to be heterogeneous. p53 and NF‐κB are known to be two common transcriptional factors modulating the expression of apoptosis‐related proteins 15, such as the proapoptotic oncoprotein Bax and the antiapoptotic molecules Bcl‐2 and Bcl‐XL. Wild‐type p53 can mediate tumor cell apoptosis under the circumstance of cell stress 16, while NF‐κB mainly suppresses tumor cell apoptosis by increasing the transcription of Bcl‐2 and Bcl‐XL 17. Thus, the possible antitumor mechanism for triptolide may involve apoptosis through the activation of p53 and/or the inhibition of NF‐κB transactivation 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23.

Triptolide can also interfere with tumor cell cycle to some extent, resulting in the G0/G1 24, G2/M 25, 26, or S cell cycle arrest 22 of tumor cells. Cell cycle arrest will result in the cessation of cell proliferation and subsequently inhibit the growth of tumor cells. Triptolide also functions as a potent angiogenesis inhibitor that correlates with the downregulation of proangiogenic Tie 2 and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 (VEGFR‐2) expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, suggesting that the antitumor property of triptolide is partially via the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis, which blocks these two endothelial receptor‐mediated signaling pathways 27.

Other potential cellular targets by which triptolide may play an antitumor effect appear to be heat shock protein (HSP), metalloproteinase 10 (ADAM10), 5‐lipoxygenase (5‐LOX), and RNA polymerase 28, 29, 30, 31. Among these potential targets, RNA polymerase II has become the most attractive molecule, because recent studies in cancer cells revealed that triptolide could be a potent inhibitor to suppress global transcription by inducing proteasome‐dependent degeneration of RNA polymerase II 32. Most importantly, Titov et al. used a “top‐down” approach to identify the molecular target of triptolide, which is XPB, a subunit of the general transcription factor TFIIH, which possesses ATPase activity. Triptolide was found to covalently bind to XPB and inhibit DNA‐dependent ATPase activity of TFIIH. As a result, RNA polymerase II‐mediated transcription was inhibited 33. This finding offers a mechanism that could account for the effect of triptolide on the activity of a number of transcription factors, such as p53 and NFκB.

Antifertility

In 1986, the discovery of the reversible antifertility action of TWHF both in male rats and in men attracted worldwide interest. Since then, six male antifertility diterpene epoxides have been isolated, which include triptolide, triptolidenol, tripchlorolide, 16‐hydroxytriptolide, and T7/19 (structure not yet published) 34. Moreover, a recent study showed that triptolide could elicit not only abnormalities of sperm in males, but also amenorrhea in females 35. It is noteworthy that triptolide exhibits its antifertility effect at a dose of as low as 50–100 μg/kg in Sprague Dawley (SD) rats by oral administration, 5–12 times lower than that required for antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive activities 36. Because triptolide possesses antifertility activity, which was found to be selective and reversible, it might be an attractive candidate as a post‐testicular male contraceptive agent 36, 37. Nevertheless, as a contraceptive agent, triptolide should not be used for prolonged periods, as studies have identified deleterious effects on spermatogenesis and irreversible infertility after long‐term administration 38.

Bioactivity in the Central Nervous System (CNS)

The therapeutic effect of triptolide on CNS diseases has attracted worldwide attention, owing to its lipophilic characteristics, small molecular weight (MW 360), and abundant presence in the brain after systemic administration 39, 40. Therefore, understanding the bioactivity of triptolide in CNS diseases is required.

Parkinson's Disease (PD)

Parkinson's disease is the second most common age‐related neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer's disease (AD), characterized by the impairment of motor capabilities, including tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability. The pathological hallmark of PD was recognized to be the loss of neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc), which was considered to affect the nigrostriatal dopaminergic (DAergic) pathway, and lead to dopamine (DA) deficiency in the striatum. In fact, a major symptom of PD is caused by DA deficiency in the striatum 41. Till now, the specific molecular events that cause the loss and degeneration of DAergic neurons remain unclear. Although the application of Levodopa alleviates most of the symptoms of PD, involuntary movements (dyskinesias) develop after several years of treatment 42. Thus, it would be beneficial to find therapeutic strategies that prevent DAergic neurons from degeneration with few side effects.

Increasing evidence has shown that the inflammatory response, induced mainly by abnormally activated microglia in the CNS, is involved in the progressive degeneration of DAergic neurons 41. Triptolide exhibits significant antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive activity, making it a promising DAergic neuroprotective drug against cytotoxins released from activated microglia, such as nitric oxide (NO), cytokines, and reactive oxygen species (ROS). We have demonstrated for the first time that triptolide and its analogue, tripchlorolide (a triptolide, 12, 13‐chlorohydrin, which is a transformation product formed reversibly by interaction of triptolide with HCl) 37 possess a potent neuroprotective effect on DAergic neurons both in vitro and in vivo 43, 44. Tripchlorolide promoted axonal elongation and protected DAergic neurons from neurotoxic lesion induced by 1‐methyl‐4‐phenylpyridinium ion (MPP+) at a concentration as low as 10−12 to 10−8 M. Furthermore, in vivo administration of tripchlorolide (1 μg/kg, i.p.) for 28 days effectively attenuated rotational behavior induced by d‐amphetamine in a rat model established by the transection of the medial forebrain bundle (MFB), and increased the survival rate of DAergic neurons in the SNpc by 67% and the amount of dopamine in the striatum of model rats. Moreover, mRNA expression of brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) was also stimulated by treatment with tripchlorolide in primary mesencephalic cultures, as revealed by in situ hybridization studies 43.

Tripchlorolide exerts its biological activity after being spontaneously converted to triptolide 37, 39. We therefore examined the activities of triptolide in a PD model both in vitro and in vivo. Triptolide attenuated the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)‐induced decrease in [3H] dopamine uptake and loss of tyrosine hydroxylase‐immunoreactive neurons in primary mesencephalic neuron/glia mixed cultures, and promoted neurite outgrowth in a concentration‐dependent manner 44. Triptolide also blocked the LPS‐induced activation of microglia and excessive production of TNFα, IL‐1β, and NO. Triptolide, at a concentration as low as 0.1 nM, significantly inhibited TNFα release following LPS‐induced activation of microglia. Only at higher concentrations (0.1 μM) did triptolide exhibit an inhibitory effect on IL‐1β and NO release from primary activated microglia induced by LPS. Moreover, triptolide at a concentration of 0.1 μM also blocked mRNA overexpression of TNFα, IL‐1β, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) 45. Most importantly, the beneficial effects of triptolide on DAergic neurons were further proven in an inflammatory rat model of PD induced by unilateral intranigral injection of LPS (10 μg) 46. Gao et al. 47 reported that triptolide prevented DAergic neuron loss, improved behavioral performance, and inhibited microglial activation in a hemiparkinsonian rat model induced by intranigral microinjection of MPP+. The suppression of triptolide in activated microglia and production of cytokines as mentioned above were further verified using in vivo and in vitro models performed by other groups 48, 49.

Alzheimer's Disease

Alzheimer's Disease, the most common neurodegenerative disease and a major form of dementia, impairs basic cognitive function 50, 51. The etiology and pathogenesis of the disease are still not fully understood. Although the amyloid β peptide (Aβ) is considered a key molecule in the pathogenesis of AD 52, 53, robust evidence indicates that activated microglia contribute to neuronal dysfunction 54. Moreover, oxidative stress, deficiency of neurotrophic factors (NTFs), and disequilibrium of Ca2+ are all involved in the pathogenesis of AD. Thus, drugs possessing multiple activities should be developed to treat AD. Given that triptolide has exhibited its potent neuroprotective activity in PD models, it may be possible that triptolide appears to be a promising agent in the therapeutic strategy for AD. Indeed, we found that triptolide exerted its neuroprotective effects in various cell models of AD 55, 56. In PC12 cell cultures, pre‐treatment with triptolide at a concentration of 0.01 nM for 48 h prevented PC12 cells from apoptosis induced by Aβ (50 μM). At the same time, the increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration was remarkably inhibited by treatment with triptolide 55. In another PC12 cell culture, triptolide at 0.1–1 nM inhibited both necrosis and apoptosis induced by glutamate. Further experiments to detect ROS and mitochondrial membrane potential suggested that the underlying mechanism of the neuroprotective effect of triptolide may correlate with the inhibition of ROS formation and stabilization of mitochondrial membrane potential 56. In addition, triptolide also exhibited neurotrophic activity in vitro. Triptolide treatment selectively up‐regulated the synthesis and release of NGF, but not BDNF and GDNF in primary rat astrocyte cultures 57. A growing body of data indicates that the loss of synapses can be elicited by inflammation and is closely related to the process of cognitive deterioration in the AD brain. Synaptic proteins distributed at synaptic vesicles or synaptic terminals are used as specific markers of synapses. Nie et al. 58 observed that triptolide promoted synaptophysin expression in hippocampal neurons in an AD cellular model. Together, these data suggest that triptolide may exert neuroprotective activity in the AD brain via multiple pharmacological mechanisms: (1) inhibiting excitotoxicity and increasing the intracellular concentration of Ca2+ in neurons induced by Aβ, (2) inhibiting oxidative stress in neurons, (3) stabilizing mitochondrial membrane potential and preventing neurons from apoptosis, and (4) alleviating the inflammatory response and promoting neurotrophic factor synthesis and release. However, whether triptolide has a therapeutic effect on AD models in vivo has not been elucidated.

Brain and Spinal Cord Injury

In addition to its potential therapeutic effects on PD and AD, triptolide was also found to improve neural function deficits, and reduce the number of infiltrating neutrophils and neuronal apoptosis in cerebral tissue in a middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) rat ischemia‐reperfusion model 59. Moreover, triptolide also played an important role in promoting brain and spinal cord repair. A recent study demonstrated that triptolide improved neurobehavioral outcomes in a traumatic brain injury (TBI) rat model, and suppressed the TBI‐induced increase in contusion volume, cell apoptosis, edema and the levels of TNFα, IL‐1β, IL‐6, PGI2, and PGE2 (inflammatory mediators), and simultaneously, reversed the decrease in levels of the antiinflammatory cytokine, IL‐10 in the ipsilateral brain of the TBI rat model 60. Triptolide was also shown to inhibit astrocytic gliosis and glial scarring, as well as inflammation, to eventually promote axon regeneration and spinal cord functional recovery in spinal cord injury 61.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease of the CNS and the most common cause of neurological disability in young adults 62. The pathological hallmarks for MS include perivascular T‐cell infiltration and disseminated demyelinating lesions in the white matter of the CNS. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) is a T cell‐mediated autoimmune disease of the CNS and serves as an animal model for human MS 63. Currently, using immunosuppressive drugs is the most common therapeutic strategy for MS. However, these immunosuppressive agents are limited by their short‐efficacy, side effects, and toxicities. For centuries, plant‐derived antiinflammatory substances have been used in folk remedies to treat inflammatory autoimmune diseases, such as MS. Recent studies have shown that triptolide could be an active suppressor of EAE 64, 65, 66, 67. LLDT‐8 has been shown to suppress T cell proliferation and activation, thereby reducing the incidence and severity of clinical paralysis in EAE 64. Following this study, Wang et al. 65 also found that treatment with triptolide from the date of EAE induction significantly delayed EAE onset and suppressed disease severity, accompanied with reduced inflammation and demyelination in the CNS. The mode of action of triptolide on EAE may be partly explained by the result that triptolide increased Hsp70 levels and stabilized the NFκB/IκB complex, which then attenuated the inflammatory response in the EAE model 66. Hsp70 is considered to exert its antiinflammatory effect at the level of NFκB 65, 66. Another interesting result is that triptolide up‐regulated the expression of Foxp3, which is a marker for CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells, in spleen mononuclear cells 65. These data together suggest that triptolide is not simply active as an immunosuppressant through its effect on NFκB but has the additional capacity to induce antigen‐specific immunomodulation by generation of a regulatory T cell response 68.

Mechanism of Action of Triptolide in the CNS

Inflammation Related Molecular Mechanism

It has been shown that triptolide is a potent inhibitor of T lymphocyte proliferation and activation, as well as the production of many cytokines including TNFα, IL‐1β, IL‐2, 6, 8 39, 69, 70. Microglia as the resident immune cells in the CNS was also found to be influenced by triptolide. In addition, triptolide inhibited the expression of two important proinflammatory enzymes, iNOS and COX‐2 in LPS‐activated microglia. As a result of the decrease in iNOS and COX‐2 expression, LPS‐induced NO accumulation and PGE2 production in microglial cultures were significantly suppressed by triptolide, respectively 45, 71. It was further demonstrated that the molecular mechanisms underlying this suppression were associated with two parallel signaling pathways: (1) JNK‐PGE2: Triptolide suppressed PGE2 expression by inhibiting the phosphorylation of the c‐jun NH2‐terminal kinase (JNK); (2) p38 MAPK→NFκB→COX‐2→PGE2: Triptolide inhibited the phosphorylation of p38, but not JNK or extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK), to reduce the transcriptional activity of NFκB, and this event resulted in the down‐regulated expression of COX‐2 and release of PGE2 39, 71. Considering the up‐regulation of Hsp70 by triptolide, and the antiinflammatory effects of Hsp70 on the inflammatory response in the EAE model at the level of NFκB 65, 66, Hsp70 may be involved in the NFκB→COX‐2→PGE2 pathway mediating the antiinflammatory activity of triptolide. However, further studies are required. In addition, a recent report by Geng et al. 72 revealed that triptolide inhibits the mRNA and protein expression of COX‐2, decreased PGE2 production, down‐regulated NFκB activity, and suppressed the phosphorylation of p38, ERK1/2 and beta‐alanyl‐alpha‐ketoglutarate transaminase (AKT) in a dose dependent manner in rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells, which is often considered to be due to neuronal cells excreting catecholamine. This suggests that suppression of NFκB→COX‐2→PGE2 by triptolide may involve both microglia and neurons.

Neurotrophic Mechanism

As demonstrated, triptolide and its analogue, tripchlorolide, promoted the production of neurotrophic factors including NGF and BDNF in primary astroglial cells or in glial‐neuron mix cultures 43, 57, suggesting triptolide could provide neuroprotection by triggering neurotrophic support. In general, astrocytes not only release neurotrophic factors to support neuronal survival and differentiation, but also respond to various types of injury and become activated. This process is called reactive astrogliosis. Activated astrocytes can form glial scars in the damaged CNS. Although glial scarring plays a helpful role in the early phase after injury to seal the lesion site, excessive scar formation constitutes an obstacle to axonal regeneration and functional recovery. Triptolide was shown to prevent astrocytes from reactive activation by blocking the Janus kinase (JAK)2/Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3 pathway in spinal cord injury 61. However, it is yet to be clarified what the exact mechanism is that mediates the neuroprotective action of triptolide.

Neuroprotective Mechanism

Triptolide can exert a neuroprotective effect by directly acting on neurons itself, via the following mechanisms: (1) exhibiting antioxidative stress activity. Triptolide inhibited the accumulation of ROS induced by glutamate or Aβ in PC12 cells. (2) suppressing excitotoxicity and Ca2+ overload. Triptolide prevented PC12 cells from apoptosis induced by Aβ or glutamate, an excitatory amino acid. Inhibition of intracellular Ca2+ overload and reversal of decreased mitochondrial membrane potential were found to contribute to the neuroprotective action of triptolide 55, 56. (3) Inhibiting activation of NFκB→COX‐2→PGE2 in neuronal cells 72. (4) Promoting synaptic protein expression in neurons. Triptolide promoted synaptophysin expression in hippocampal neurons damaged by Aβ‐stimulated microglial conditioned medium 58.

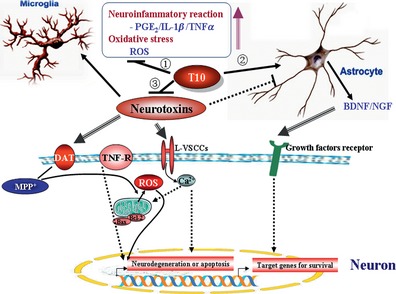

In summary, triptolide may protect neurons from damage induced by various neurotoxins by suppressing inflammation caused by microglial activation and promoting neurotrophic effects provided by astrocytes. In contrast, triptolide may directly act on neurons to trigger neuronal survival mechanisms or extinguish the process of neurodegeneration and apoptosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of action of triptolide in the central nervous system. Neurotoxins including MMP +, Aβ, glutamate, and H 2 O 2 can trigger microglial activation, release proinflammatory factors (PGE2, IL‐1β, tumor necrosis factor‐α [TNFα]) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) from activated microglia, activate receptors or transporters located on neuronal membranes, and may inhibit the neurotrophic activity of astrocytes. Triptolide (T10) was found to inhibit neuroinflammation and oxidative stress (①), stimulate the production and release of brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and NGF in astrocytes (②), prevent neuronal degeneration and apoptosis triggered by MPP + neurotoxicity (③), which is transported by dopamine transporters (DAT) from the extraneuronal space to the cytoplasm of the neuron, glutamate, and Aβ, which can make L‐type voltage‐sensitive calcium channels (L‐VSCCs) open, resulting in Ca2+ influx. In contrast, triptolide provides a neurotrophic effect on neurons by simulating BDNF and NGF production. As a result, neurons survive because of a decrease in ROS accumulation and Ca2+ overload, inhibition of mitochondrial dependent or independent apoptosis, which may be mediated by death receptors such as TNF receptor (TNF‐R), and the expression of target genes for survival.

Clinical Perspectives

Some naturally occurring terpenes in herbal materials, mainly diterpenes and triterpenes, have been demonstrated to be neuroprotective in neurotoxic models, for example, diterpene ginkgolide B from Ginkgo biloba, a series of ginsenosides from Panax ginseng belonging to triterpenoid saponins, and a carotenoid astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis. It is well established that ginsenosides exert anti‐Parkinsonian activity 73. Similarly, triptolide as a diterpene could be a promising drug therapy for CNS diseases.

On the other hand, given that the pathogenesis of most neurological diseases is not single factor‐derived, therapies based on single targets are not likely to provide the most efficient disease modification or neuroprotection. Thus, therapeutics with multiple actions is required, and triptolide exerts in accordance with this principle. Moreover, a combination of compounds that interfere simultaneously with different key events of neurodegenerative disease pathology seems to be the most promising strategy 42, 73.

In general, the potential medicinal value of triptolide in the CNS is attracting extensive attention. However, its poor water solubility and systemic toxicity limit its clinical application. Some strategies have been performed to solve this critical problem. The most common ideas include structural modification according to the SAR and development of a drug carrier for administrating the drug, such as nanoparticles and microemulsions 74, 75, 76, 77.

Conclusion

Although many questions still require answers, triptolide is a very promising compound with multiple biological activities and a specific chemical structure that can be modified in various ways. Therefore, we believe that triptolide is worth further investigation, particularly its effects in the CNS. Understanding its molecular targets of action, the detailed SAR and pharmacokinetics are very important to develop new derivatives or dosages in order to enhance therapeutic efficacy and reduce systematic toxicity.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (Xiao‐Min Wang. 2011CB504100), the NSFC of China (Xiao‐Min Wang, 81030062; 30973540), and the Important National Science & Technology Specific Projects (Xiao‐Min Wang, 2011ZX09102‐003‐01).

References

- 1. Tao X, Davis LS, Lipsky PE. Effect of an extract of the Chinese herbal remedy Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F on human immune responsiveness. Arthritis Rheum 1991;34:1274–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tao X, Lipsky PE. The Chinese anti‐inflammatory and immunosuppressive herbal remedy Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2000;26:29–50, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kupchan SM, Court WA, Dailey RG Jr., Gilmore CJ, Bryan RF. Triptolide and tripdiolide, novel antileukemic diterpenoid triepoxides from Tripterygium wilfordii . J Am Chem Soc 1972;94:7194–7195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen BJ. Triptolide, a novel immunosuppressive and anti‐inflammatory agent purified from a Chinese herb Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F. Leuk Lymphoma 2001;42:253–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu Q. Triptolide and its expanding multiple pharmacological functions. Int Immunopharmacol 2011;11:377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhou ZL, Yang YX, Ding J, Li YC, Miao ZH. Triptolide: structural modifications, structure‐activity relationships, bioactivities, clinical development and mechanisms. Nat Prod Rep 2012;29:457–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brinker AM, Ma J, Lipsky PE, Raskin I. Medicinal chemistry and pharmacology of genus Tripterygium (Celastraceae). Phytochemistry 2007;68:732–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yu DQ, Zhang DM, Wang HB, Liang XT. [Structure modification of triptolide, a diterpenoid from Tripterygium wilfordii]. Yao Xue Xue Bao 1992;27:830–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou R, Zhang F, He PL, et al. (5R)‐5‐hydroxytriptolide (LLDT‐8), a novel triptolide analog mediates immunosuppressive effects in vitro and in vivo. Int Immunopharmacol 2005;5:1895–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen X, Murakami T, Oppenheim JJ, Howard OM. Triptolide, a constituent of immunosuppressive Chinese herbal medicine, is a potent suppressor of dendritic‐cell maturation and trafficking. Blood 2005;106:2409–2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu Q, Chen T, Chen G, et al. Triptolide impairs dendritic cell migration by inhibiting CCR7 and COX‐2 expression through PI3‐K/Akt and NF‐kappaB pathways. Mol Immunol 2007;44:2686–2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu C, Xia Y, Wang P, Lu L, Zhang F. Triptolide protects mice from ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibition of IL‐17 production. Int Immunopharmacol 2011;11:1564–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Qiu D, Kao PN. Immunosuppressive and anti‐inflammatory mechanisms of triptolide, the principal active diterpenoid from the Chinese medicinal herb Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f. Drugs R D 2003;4:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pan J. RNA polymerase – an important molecular target of triptolide in cancer cells. Cancer Lett 2010;292:149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reed JC. Apoptosis‐targeted therapies for cancer. Cancer Cell 2003;3:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amundson SA, Myers TG, Fornace AJ Jr. Roles for p53 in growth arrest and apoptosis: putting on the brakes after genotoxic stress. Oncogene 1998;17:3287–3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Karin M. Nuclear factor‐kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature 2006;441:431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jiang XH, Wong BC, Lin MC, et al. Functional p53 is required for triptolide‐induced apoptosis and AP‐1 and nuclear factor‐kappaB activation in gastric cancer cells. Oncogene 2001;20:8009–8018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin J, Chen LY, Lin ZX, Zhao ML. The effect of triptolide on apoptosis of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cells. J Int Med Res 2007;35:637–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhu W, Hu H, Qiu P, Yan G. Triptolide induces apoptosis in human anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cells by a p53‐independent but NF‐kappaB‐related mechanism. Oncol Rep 2009;22:1397–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yu Q. Restoring p53‐mediated apoptosis in cancer cells: new opportunities for cancer therapy. Drug Resist Updat 2006;9:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu J, Jiang Z, Xiao J, et al. Effects of triptolide from Tripterygium wilfordii on ERalpha and p53 expression in two human breast cancer cell lines. Phytomedicine 2009;16:1006–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chang HJ, Kim MH, Baek MK, et al. Triptolide inhibits tumor promoter‐induced uPAR expression via blocking NF‐kappaB signaling in human gastric AGS cells. Anticancer Res 2007;27:3411–3417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhao F, Chen Y, Li R, Liu Y, Wen L, Zhang C. Triptolide alters histone H3K9 and H3K27 methylation state and induces G0/G1 arrest and caspase‐dependent apoptosis in multiple myeloma in vitro. Toxicology 2009;267:70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li J, Zhu W, Leng T, et al. Triptolide‐induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human renal cell carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep 2011;25:979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhao F, Chen Y, Zeng L, et al. Role of triptolide in cell proliferation, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis and histone methylation in multiple myeloma U266 cells. Eur J Pharmacol 2010;646:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. He MF, Huang YH, Wu LW, Ge W, Shaw PC, But PP. Triptolide functions as a potent angiogenesis inhibitor. Int J Cancer 2009;126:266–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Westerheide SD, Kawahara TL, Orton K, Morimoto RI. Triptolide, an inhibitor of the human heat shock response that enhances stress‐induced cell death. J Biol Chem 2006;281:9616–9622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Soundararajan R, Sayat R, Robertson GS, Marignani PA. Triptolide: an inhibitor of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 10 (ADAM10) in cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther 2009;8:2054–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mujumdar N, Mackenzie TN, Dudeja V, et al. Triptolide induces cell death in pancreatic cancer cells by apoptotic and autophagic pathways. Gastroenterology 2010;139:598–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vispe S, DeVries L, Creancier L, et al. Triptolide is an inhibitor of RNA polymerase I and II‐dependent transcription leading predominantly to down‐regulation of short‐lived mRNA. Mol Cancer Ther 2009;8:2780–2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Y, Lu JJ, He L, Yu Q. Triptolide (TPL) inhibits global transcription by inducing proteasome‐dependent degradation of RNA polymerase II (Pol II). PLoS ONE 2011;6:e23993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Titov DV, Gilman B, He QL, et al. XPB, a subunit of TFIIH, is a target of the natural product triptolide. Nat Chem Biol 2011;7:182–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhen QS, Ye X, Wei ZJ. Recent progress in research on Tripterygium: a male antifertility plant. Contraception 1995;51:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ji W, Li J, Lin Y, et al. Report of 12 cases of ankylosing spondylitis patients treated with Tripterygium wilfordii . Clin Rheumatol 2010;29:1067–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lue Y, Sinha Hikim AP, Wang C, et al. Triptolide: a potential male contraceptive. J Androl 1998;19:479–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Matlin SA, Belenguer A, Stacey VE, et al. Male antifertility compounds from Tripterygium wilfordii Hook f. Contraception 1993;47:387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huynh PN, Hikim AP, Wang C, et al. Long‐term effects of triptolide on spermatogenesis, epididymal sperm function, and fertility in male rats. J Androl 2000;21:689–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lu L, Li F, Wang X. Novel anti‐inflammatory and neuroprotective agents for Parkinson's disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2009;9:232–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang X, Liang XB, Li FQ, et al. Therapeutic strategies for Parkinson's disease: the ancient meets the future–traditional Chinese herbal medicine, electroacupuncture, gene therapy and stem cells. Neurochem Res 2008;33:1956–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron 2003;39:889–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Meissner WG, Frasier M, Gasser T, et al. Priorities in Parkinson's disease research. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011;10:377–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li FQ, Cheng XX, Liang XB, et al. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects of tripchlorolide, an extract of Chinese herb Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F, on dopaminergic neurons. Exp Neurol 2003;179:28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li FQ, Lu XZ, Liang XB, et al. Triptolide, a Chinese herbal extract, protects dopaminergic neurons from inflammation‐mediated damage through inhibition of microglial activation. J Neuroimmunol 2004;148:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhou HF, Niu DB, Xue B, et al. Triptolide inhibits TNF‐alpha, IL‐1 beta and NO production in primary microglial cultures. NeuroReport 2003;14:1091–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhou HF, Liu XY, Niu DB, Li FQ, He QH, Wang XM. Triptolide protects dopaminergic neurons from inflammation‐mediated damage induced by lipopolysaccharide intranigral injection. Neurobiol Dis 2005;18:441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gao JP, Sun S, Li WW, Chen YP, Cai DF. Triptolide protects against 1‐methyl‐4‐phenyl pyridinium‐induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity in rats: implication for immunosuppressive therapy in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Bull 2008;24:133–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Liu Y, Chen HL, Yang G. Extract of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F protect dopaminergic neurons against lipopolysaccharide‐induced inflammatory damage. Am J Chin Med 2010;38:801–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li G, Ma R, Xu Y. [Protective effects of triptolide on the lipopolysaccharide‐mediated degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in substantia nigra]. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 2006;26:715–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Goedert M, Spillantini MG. A century of Alzheimer's disease. Science 2006;314:777–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nussbaum RL, Ellis CE. Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1356–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Selkoe DJ. Amyloid beta‐protein and the genetics of Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem 1996;271:18295–18298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gandy S. The role of cerebral amyloid beta accumulation in common forms of Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest 2005;115:1121–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Perry VH, Nicoll JA, Holmes C. Microglia in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2010;6:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gu M, Zhou HF, Xue B, Niu DB, He QH, Wang XM. [Effect of Chinese herb Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F monomer triptolide on apoptosis of PC12 cells induced by Abeta1‐42]. Sheng Li Xue Bao 2004;56:73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. He Q, Zhou H, Xue B, Niu D, Wang X. [Neuroprotective effects of Tripterygium Wilforddi Hook F monomer T10 on glutamate induced PC12 cell line damage and its mechanism]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao 2003;35:252–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xue B, Jiao J, Zhang L, et al. Triptolide upregulates NGF synthesis in rat astrocyte cultures. Neurochem Res 2007;32:1113–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nie J, Zhou M, Lu C, et al. Effects of triptolide on the synaptophysin expression of hippocampal neurons in the AD cellular model. Int Immunopharmacol 2012;13:175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wei DM, Huang GZ, Zhang YG, Rao GX. [Influence of triptolide on neuronal apoptosis in rat with cerebral injury after focal ischemia reperfusion]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2004;29:1089–1091, 1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lee HF, Lee TS, Kou YR. Anti‐inflammatory and neuroprotective effects of triptolide on traumatic brain injury in rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2012;182:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Su Z, Yuan Y, Cao L, et al. Triptolide promotes spinal cord repair by inhibiting astrogliosis and inflammation. Glia 2010;58:901–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jadidi‐Niaragh F, Mirshafiey A. Therapeutic approach to multiple sclerosis by novel oral drug. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2010;5:66–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Martin R, McFarland HF, McFarlin DE. Immunological aspects of demyelinating diseases. Annu Rev Immunol 1992;10:153–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fu YF, Zhu YN, Ni J, et al. (5R)‐5‐hydroxytriptolide (LLDT‐8), a novel triptolide derivative, prevents experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis via inhibiting T cell activation. J Neuroimmunol 2006;175:142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wang Y, Mei Y, Feng D, Xu L. Triptolide modulates T‐cell inflammatory responses and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurosci Res 2008;86:2441–2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kizelsztein P, Komarnytsky S, Raskin I. Oral administration of triptolide ameliorates the clinical signs of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) by induction of HSP70 and stabilization of NF‐kappaB/IkappaBalpha transcriptional complex. J Neuroimmunol 2009;217:28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Fan HC, Ren XR, Yu JZ, et al. [Suppression of murine EAE by triptolide is related to downregulation of INF‐gamma and upregulation of IL‐10 secretion in splenic lymphocytes]. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi 2009;25:222–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. van Eden W. Protective and therapeutic effect of triptolide in EAE explained by induction of major stress protein HSP70. J Neuroimmunol 2009;217:10–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chan MA, Kohlmeier JE, Branden M, Jung M, Benedict SH. Triptolide is more effective in preventing T cell proliferation and interferon‐gamma production than is FK506. Phytother Res 1999;13:464–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Qiu D, Zhao G, Aoki Y, et al. Immunosuppressant PG490 (triptolide) inhibits T‐cell interleukin‐2 expression at the level of purine‐box/nuclear factor of activated T‐cells and NF‐kappaB transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem 1999;274:13443–13450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gong Y, Xue B, Jiao J, Jing L, Wang X. Triptolide inhibits COX‐2 expression and PGE2 release by suppressing the activity of NF‐kappaB and JNK in LPS‐treated microglia. J Neurochem 2008;107:779–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Geng Y, Fang M, Wang J, et al. Triptolide down‐regulates COX‐2 expression and PGE2 release by suppressing the activity of NF‐kappaB and MAP kinases in lipopolysaccharide‐treated PC12 cells. Phytother Res 2011;26:337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Song JX, Sze SC, Ng TB, et al. Anti‐Parkinsonian drug discovery from herbal medicines: what have we got from neurotoxic models? J Ethnopharmacol 2012;139:698–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Liu MX, Dong J, Yang YJ, Yang XL, Xu HB. [Preparation and toxicity of triptolide‐loaded poly (D,L‐lactic acid) nanoparticles]. Yao Xue Xue Bao 2004;39:556–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mei Z, Chen H, Weng T, Yang Y, Yang X. Solid lipid nanoparticle and microemulsion for topical delivery of triptolide. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2003;56:189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mei Z, Li X, Wu Q, Hu S, Yang X. The research on the anti‐inflammatory activity and hepatotoxicity of triptolide‐loaded solid lipid nanoparticle. Pharmacol Res 2005;51:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mei Z, Wu Q, Hu S, Li X, Yang X. Triptolide loaded solid lipid nanoparticle hydrogel for topical application. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 2005;31:161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]