Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Wilson disease (WD) is an autosomal recessive disorder of copper metabolism caused by mutations in the ATP7B gene, which leads to copper accumulation in various organs and predominantly presents with hepatic or neuropsychiatric symptoms 1. Chelation therapy is central, and liver transplant (LT) is the only option if it fails 2. Both orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) and living‐donor liver transplantation (LDLT) are acceptable 3, 4, 5, 6. We administered a low‐copper diet and zinc monotherapy to 8 post‐LT patients with WD and followed each for 3 to 9 years in order to explore the necessity of a low‐copper diet and zinc monotherapy after LT as well as chelation therapy for post‐LT patients with neurological deterioration.

Our study was approved by the ethics committees of Huashan Hospital and First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University. The diagnosis was based on clinical manifestations and ATP7B mutation analysis using a procedure previously described 7. Patients 1, 6, 7 received LT due to decompensated liver cirrhosis and patients 2, 3, 5 did due to fulminant liver failure. Patients 4, 8 had mild liver dysfunction, but received LT for disabling neurological symptoms. Patients 1, 3, 4, 5 received LT right after they were diagnosed. Patients 2, 6, 7, 8 were treated with penicillamine combined with zinc for 6–12 months prior to LT but responded poorly. Patient 7 received LDLT with her mother as the donor and the other patients received OLT. The surgery was successful for each patient. Tacrolimus was administered for immunosuppression. One month after LT, we gave the patients 140 mg of zinc gluconate three times a day, separated from food by at least 1 h. The patients were also asked to avoid food rich in copper contents 8. Patients were followed up by two senior neurologists. Laboratory data were collected monthly after LT for 1 year, yearly for 2 years and every 2 years afterward.

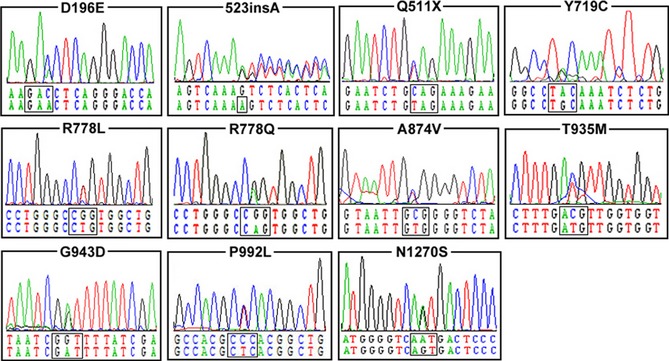

The genotype, clinical manifestations and follow‐up data are shown in Table 1. Chromatograms of ATP7B sequencing results are shown in Figure 1. For the eight patients, the ceruloplasmin levels returned to normal 1 month after LT and liver functions tests within 1 year after LT. Urinary copper levels were measured in 4 of 8 patients, which decreased but still higher than normal. Three patients (patient 3, 5, and 6) with good compliance had normal liver function test results and abdominal ultrasound findings ever since. Another three patients (patients 1, 2, and 7) with poor compliance presented different symptoms. The neurological symptoms of patients 4 and 8 worsened despite successful LT.

Table 1.

Clinical manifestations and genotypes of WD patients

| No. | Sex | Genotype | Age(years) | K‐F Ring | Brain MRI | Phenotype | Ceruloplasmin Level(g/L) | Urinary Copper(ug/24 h) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | LT | Present | Pre‐LT | Present | Pre‐LT | >1m‐2y | Pre‐LT | Post‐LT | >1m‐2y | Present | Pre‐LT | Post‐LT | >1m‐2y | Present | Pre‐LT | Post‐LT | >1m‐2y | Present | |||

| 1 | M | R778Q/T935M | 26 | 26 | 34 | + | + | — | — | cirrhosis | — | CR | — | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 218 | NA | 232 | 36 |

| 2 | M | Q511X/D196E | 29 | 32 | died | + | died | + | + | FLF | — |

dysarthria, dysphagia, limbs dystonia, depression |

died | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.17 | died | 378 | 65 | NA | died |

| 3 | F | R778L/Y719C | 16 | 16 | 22 | — | — | — | — | FLF | — | — | — | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 161 | 105 | 56 | 63 |

| 4 | F | 523insA/Q511X | 12 | 12 | 18 | + | + | + | + |

AAE dysarthria, tremor |

not improved |

drooling, dysarthria, tremor |

dysarthria | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 192 | NA | NA | 72 |

| 5 | M | A874V/G943D | 17 | 17 | 23 | + | + | — | — | FLF | — | — | — | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.2 | 168 | NA | NA | NA |

| 6 | F | R778L/R778L | 14 | 16 | 20 | + | + | — | — | cirrhosis | — | — | — | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 175 | NA | NA | NA |

| 7 | F | R778L/N1270S | 11 | 17 | 21 | + | + | + | + | cirrhosis | — |

drooling, dysarthria, tremor, torsion dystonia |

torsion dystonia, lisp |

0.04 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 317 | 100 | 71 | 112 |

| 8 | F | R778L/R778L | 16 | 20 | 23 | + | + | + | + | AAE dysarthria | not improved |

drooling, dysarthria, dysphagia, depression |

Lisp depression dysphagia |

0.02 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 335 | 150 | 46 | 25 |

M: male; F: female; LT: liver transplantation; Pre‐LT: prior to LT; Post‐LT: one month after LT; +: positive or abnormal; —: negative or normal; FLF: fulminant liver failure; CR: chronic rejection; AAE: asymptomatic aminotransferase elevation; NA: not available.

Figure 1.

The chromatograms of the ATP7B mutations identified in this study. The panel for each chromatogram depicts the mutated sequence.

Patient 1 was admitted for jaundice and edema 2 years after LT. He was scaled as Child‐Pugh level A with total bilirubin 26.3 umol/L. Liver cirrhosis and splenomegaly were detected by ultrasonography. Liver biopsy suggested chronic cell rejection. The blood concentration of tacrolimus was 6.59 ng/mL,within the recommended range 9. Plasma copper level was normal (13.8 μmol/L; normal range: 12.7–30.2 μmol/L), but ceruloplasmin level was low (0.15 g/L; normal range: 0.2–0.4 g/L) and 24‐h urinary copper excretion was elevated (232 μg/24 h; normal range: <100 μg/24 h), thus disrupted copper metabolism was suspected. 125 mg of D‐penicillamine three times a day and 280 mg of zinc gluconate was administered. Jaundice was resolved and liver functions tests were normal 3 months later, so D‐penicillamine was tapered off. Our recommended therapy was started. The patient is compliant with the therapy and remained in good condition ever since.

Patient 2 was admitted for dysarthria, dysphagia, limbs dystonia, and depression 5 months after LT. These symptoms were not relieved by reducing the dosage of tacrolimus. Normal liver functions tests but low ceruloplasmin level (0.17 g/L) was detected. The brain MRI showed no significant changes pre‐ and post‐LT. He was treated with 250 mg of D‐penicillamine twice a day and 280 mg of zinc gluconate three times a day, along with benzhexol, levodopa, and amitriptyline to control his symptoms. His symptoms improved significantly after 6 months but he discontinued the regimen. The patient died from fulminant liver failure 1 year later.

Patient 7 developed drooling, slurred speech, and tremor of four limbs 3 months after LT. The symptoms were considered as the side effects of tacrolimus but worsened despite reduced dosage. Torsion dystonia of the trunk and frequent stumbling emerged 1 year later. 125 mg of D‐penicillamine and 280 mg of zinc gluconate three times a day were started along with benzhexol and clonazepam for symptomatic treatment. Seven months later, drooling and tremor improved significantly while slurred speech and torsion dystonia improved moderately. D‐penicillamine was stopped 6 months later. She is on 140 mg of zinc gluconate three times a day and a low‐copper diet. At present, torsion dystonia and a slight lisp remain.

The neurological symptom of patients 4 and 8 deteriorated 1 month after LT, without significant changes in brain MRI. Patient 4 presented drooling, dysarthria, and tremor of right hand which prohibited writing. She was treated three times a day with 125 mg of D‐penicillamine and 280 mg of zinc gluconate immediately. Her drooling and tremor disappeared with a remaining slight lisp. Patient 8 developed drooling, dysarthria, severe dysphagia, and depression but refused chelation therapy. Benzhexol, baclofen, and clonazepam were included as adjunctive therapy. Drooling disappeared, dysphagia and depression improved slightly, but dysarthria sustains.

In summary, our results demonstrate that LT do ameliorate metabolic defects. However, the neuropsychiatric WD patients with normal or mildly deficient hepatic function are not advised to receive LT. Zinc therapy and a low‐copper diet help in alleviating neurological symptoms when graft rejection and tacrolimus‐associated adverse events are ruled out as possible causes. The effect of the chelation therapy, zinc monotherapy, and a low‐copper diet in patients with WD after LT shall not be overlooked despite small sample size of our study.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the participants for their help and willingness to participate in this study and the anonymous reviewers for improving this manuscript. This work was supported by Grants (81125009, 30370517, and 30971013) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China to Zhi‐Ying Wu.

References

- 1. Huster D. Wilson disease. Best Pract Res Cl Ga 2010;24:531–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Semis S, Karakayali H, Aliosmanoglu I, et al. Liver transplantation for Wilson's disease. Transplant P 2008;40:228–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tamura S, Sugawara Y, Kishi Y, Akamatsu N, Kaneko J, Makuuchi M. Living‐related liver transplantation for Wilson's disease. Clin Transplant 2005;19:483–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yoshitoshi EY, Takada Y, Oike F, et al. Long‐term outcomes for 32 cases of Wilson's disease after living‐donor liver transplantation. Transplantation 2009;87:261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ikegami T, Taketomi A, Soejima Y, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for acute liver failure: A 10‐year experience in a single center. J Am Coll Surgeons 2008;206:412–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang XH, Zhang F, Li XC, et al. Eighteen living related liver transplants for Wilson's disease: A single‐center. Transplant P 2004;36:2243–2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu ZY, Zhao GX, Chen WJ, et al. Mutation analysis of 218 Chinese patients with Wilson disease revealed no correlation between the canine copper toxicosis gene MURR1 and Wilson disease. J Mol Med‐Jmm 2006;84:438–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shimizu N, Yamaguchi Y, Aoki T. Treatment and management of Wilson's disease. Pediatr Int 1999;41:419–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lucey MR, Terrault N, Ojo L, et al. Long‐term management of the successful adult liver transplant: 2012 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Liver Transpl 2013;19:3–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]