Summary

Aim

To investigate the mechanism of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress–induced apoptosis as well as the protective action of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) both in vivo and in vitro.

Methods and Results

ER stress–induced apoptosis was involved in the injuries of spinal cord injury (SCI) model rat. bFGF administration improved the recovery and increased the survival of neurons in spinal cord lesions in model rat. The protective effect of bFGF is related to the inhibition of CHOP, GRP78 and caspase‐12, which are ER stress–induced apoptosis response proteins. bFGF administration also increased the survival of neurons and the expression of growth‐associated protein 43 (GAP43), which is related to neural regeneration. The protective effect of bFGF is related to the activation of downstream signals, PI3K/Akt/GSK‐3β and ERK1/2, especially in the ER stress cell model.

Conclusions

This is the first study to illustrate that the role of bFGF in SCI recovery is related to the inhibition of ER stress–induced cell death via the activation of downstream signals. Our work also suggested a new trend for bFGF drug development in central neural system injuries, which are involved in chronic ER stress–induced apoptosis.

Keywords: Apoptosis, bFGF, ER stress, ERK1/2, PI3K/Akt, Spinal cord injury

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a severe health problem that usually causes lifelong disability for a patient. The pathology of SCI is divided into two phases: the primary injury is the mechanical impact afflicted directly on the spine, and the secondary injury is a complex cascade of molecular events including disturbances in ionic homeostasis, local edema, ischemia, focal hemorrhage, free radical stress, and inflammatory response 1. Studies have shown that apoptosis plays a key role in secondary damage in animal models and human tissue by causing progressive degeneration of the spinal cord 2, 3. Although the exact molecular pathway of this secondary injury is still controversial, therapeutic strategies that inhibit or delay apoptosis and cell death may contribute to SCI recovery.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an important intracellular organelle that is responsible for proper protein folding 4. Various exogenous stressors, including glucose deprivation 5, depletion of ER Ca2+ stores 6, exposure to free radicals 7, and accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins 8, disrupt the proper function of the ER and trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR), which plays an important role in regulating cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis to cope with this adverse situation. ER stress–induced apoptosis is related to the activation of the glucose‐regulated protein 78 (GRP78), the transcription activation of the C/EBP homologous transcription factor (CHOP), and the activation of ER‐associated caspase‐12 9. During SCI, prolonged ER stress without successful cellular protective mechanisms by the UPR eventually results in neural apoptosis 10, 11. It has been proven that ER stress is involved in cell apoptosis after SCI, especially in neurons and oligodendrocytes but not astrocytes 1. The latest study indicated that deletion of pro‐apoptotic CHOP did not result in improvement of locomotor function after severe contusive spinal cord injury 12. The role of ER stress–induced apoptosis and related proteins in spinal cord injuries needs further investigation.

As an extensively expressed protein family, fibroblast growth factor can share receptors and affect a variety of biological functions, including proliferation, morphogenesis, and suppression of apoptosis during development via a more complex signal transduction system 13, 14, 15. Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), also named FGF2, is highly expressed in the nervous system and has multiple roles. bFGF is a differentiation factor in the hippocampus and has neurotrophic activities, such as supporting the survival and growth of cultured neurons and neural stem cells 16, 17. In neural stem/progenitor cell transplant treatment after spinal cord injury in rats, bFGF transient infusion or transgene can promote axon regeneration and functional recovery 18, 19. Several growth factors, such as nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), show neuroprotective effects and improve SCI recovery 20, 21. However, the molecular mechanism of bFGF treatment in SCI recovery is still undefined. In this study, we investigated the mechanism of ER stress–induced apoptosis as well as the protective action of bFGF both in vivo and in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Viability Assay

PC12 cells were purchased from the Cell Storage Center of Wuhan University. Cells were cultured in DMEM, incubated in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C, and supplemented with heat‐inactivated 10% fetal bovine serum and 5% horse serum. PC12 cells were seeded on 96‐well plates and treated with different doses of the ER stress activator, thapsigargin (TG) for 12 h. Based on our previous study, cells were also pretreated with recombinant bFGF (40 ng/mL) for 2 h 22. Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. To further evaluate the effect of PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 activation on oxidative injury, cells were pretreated for 2 h with specific inhibitors, LY294002 (20 μM) and U0126 (20 μM), before the addition of bFGF, as previously described 22, 23. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Procedure of the Animal Model of Spinal Cord Injury

Young adult female Sprague–Dawley rats (220–250 g) were purchased from the Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The animal use and care protocol conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals from the National Institutes of Health and was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Wenzhou Medical College. All animals were housed in standard conditions of temperature and 12‐h light/dark cycle and fed with food and water. Rats were positioned on a cork platform after being anesthetized with 10% chloralic hydras (3.5 mL/kg, i.p.). For each rat, the skin was incised along the midline of the back, and the vertebral column was exposed. A laminectomy was performed at the T9 level. The exposed spinal cord was subjected to crushed injury compressing with a vascular clip (15 g forces, Oscar, China). Sham groups received the same surgical procedure but sustained no impact injury. Their spinal cords were exposed for 1 min. Postoperative care involved manually emptying the urinary bladder twice a day (until the return of bladder function) and administration of cefazolin sodium (50 mg/kg, i.p.). Recombinant human bFGF was purchased from Sigma (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Following the spinal cord occlusion, the bFGF solution was injected subcutaneously near the back wound at a dose of 80 μg/kg/day until the animal was executed.

Locomotion Recovery Assessment

Two blind independent examiners scored the locomotion recovery in an open field, according to the Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan (BBB) scale during the 7‐day postoperative period. Briefly, the BBB locomotion rating scale ranges from 0 points (complete paralysis) to 21 points (normal locomotion). The scale is based upon the natural progression of locomotion recovery in rats with thoracic spinal cord injuries.

Hematoxylin–eosin Staining and Immunohistochemistry

The rats were deeply anesthetized with 10% chloralic hydras and perfused transcardially with saline and buffered 4% para‐formaldehyde at 1, 3 and 7 days. The spinal cords T7‐T10 around the lesion epicenter were excised, the transverse paraffin sections were mounted in Poly‐L‐Lysine‐coated slides for histopathological examination by Hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining. The transverse paraffin sections were also incubated in 3% H2O2 and 80% carbinol for 30 min and then in blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the sections were incubated at 4°C overnight with the following primary antibodies: CHOP (1:150), GRP78 (1:200), and caspase‐12 (1:600, Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). After triple washing in PBS, the sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at 37°C. The reaction was stopped with 3, 3′‐diaminobenzidine (DAB). The results were imaged at a magnification of 400 using a Nikon ECLPSE 80i (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The optical densities and positive neuron numbers of CHOP, GRP78 and caspase‐12 were counted at 5 randomly selected fields per sample.

Western Blot Analysis

Total proteins were purified using protein extraction reagents for the spinal cord segment and PC12 cells. The equivalent of 50 μg of protein was separated by 11.5% gel and then transferred onto a PVDF membrane. After blocking with 5% fat‐free milk, the membranes were incubated with the following antibodies: CHOP (1:500), GRP78 (1:200), and caspase‐12 (1:600) overnight. The membranes were washed with TBS and treated with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. The signals were visualized with the ChemiDicTM XRS+ Imaging System (Bio‐Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), and the band densities were quantified with Multi Gauge Software of Science Lab 2006 (FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Apoptosis Assay

DNA fragmentation in vivo was detected by the one step TUNEL Apoptosis Assay KIT (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The images were captured with a Nikon ECLIPSE Ti microscope (Nikon, Japan). The apoptotic rates of the PC12 cells treated with TG and bFGF were measured using a PI/Annexin V‐FITC kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and then analyzed by a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) as the manual description.

Immunofluorescence Staining

The sections were incubated with 10% normal donkey serum for 1 h at room temperature in PBS. They were then incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies overnight at 4°C in the same buffer. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258 (0.25 μg/mL) dye. For neurons and GAP43 detection, the following primary antibodies were used based on different targets: anti‐NeuN (1:500, Millipore), anti‐GAP43 (1:50), and antistathmin (1:50). After primary antibody incubation, the sections were washed and then incubated for 1 h with secondary antibody (1:500). All images were captured on Nikon ECLIPSE Ti microscope.

Statistical Analysis

The data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined with Student's t‐test when there were two experimental groups. For more than two groups, statistical evaluation of the data was performed using the one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, followed by Dunnett's post hoc test with values of P < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

ER Stress–Induced Apoptosis is Involved in the Early Stages of SCI

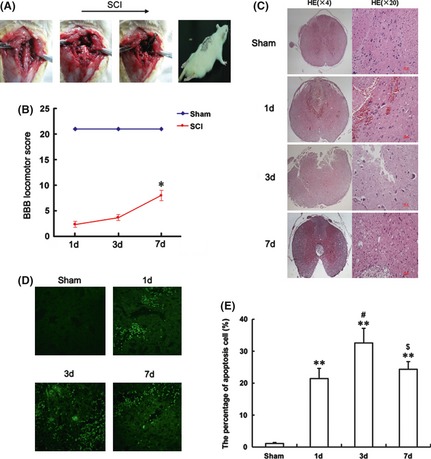

To evaluate the role of ER stress in SCI, we performed the animal model as described previously (Figure 1A). Animals subjected to spinal cord contusions showed dramatic and bilateral hindlimb paralysis with no movement at all or only slight movements of a joint from the first 1‐h postinjury. At 1 day after injury, the BBB scale score of the SCI group was 2.33 ± 0.67, which corresponds to slight and/or extensive movement of two or three joints. The locomotor scores increased progressively during the experimental period. At 3 and 7 days after contusion, the BBB scores were 3.67 ± 0.88 (P < 0.05) and 8.00 ± 0.58 (P < 0.001), which corresponds to occasional plantar step placement with weight support (Figure 1B). Compared with the sham operation group (1‐d post‐trauma), the gray matter of the SCI group exhibited large hemorrhages, which were most pronounced in the central and dorsal horn of the lesioned spinal cords. Progressive destruction of the dorsal white matter and central gray matter tissue was found 3‐day postinjury. The lesion segments displayed hemorrhagic necrosis, neuron loss, karyopyknosis, and infiltrated polymorphonuclear leukocytes and macrophages. In the segments collected at 7‐day postinjury, there was minimal hemorrhaging and some neuron regeneration, but demyelination appeared as well as numerous cavities (Figure 1C). The cell apoptosis in the spinal lesions were detected by TUNEL staining; the bright green dots were deemed apoptosis‐positive cells in the lesions. There is no apoptosis‐positive cell in the sham group. The numbers of TUNEL‐positive cells increased significantly 1 day after injury and were maximal at 3 days (Figure 1D,E).

Figure 1.

The procedure and assessment of spinal cord injury (SCI) model rat. (A) The procedure of the SCI model from left to right, as shown by arrow head. (B) The Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan (BBB) scores of SCI model rat at 1, 3 and 7 days after contusion. The score of the sham group was 21 points (meaning normal locomotion). *represents P < 0.05 versus the sham group. Data are the mean values ± SEM, n = 6. One‐way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test was performed for statistical evaluation. (C) H and E staining results of SCI rat at 1, 3 and 7 days after contusion. (D) TUNEL apoptosis assay of model rat spinal cord lesions. Immunofluorescence results of the TUNEL assay. Bright green dots were deemed positive apoptosis cell, magnification was 20×. (E) The analysis of apoptosis cell 1, 3 and 7 days after spinal cord injury lesions. The percentage of apoptosis was counted from 3 random 1 × 1 mm2 areas. **represents P < 0.01 versus the sham group, #represents P < 0.05 versus the 1 day group, and $represents P < 0.05 versus the 3 days group. Data are the mean values ± SEM, n = 6.

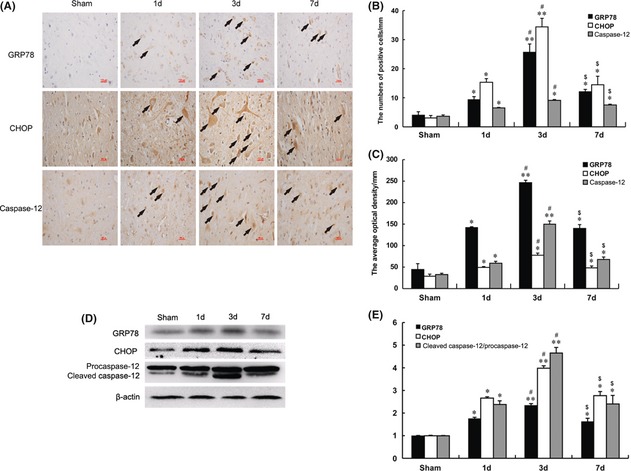

Immunohistochemistry staining was used to investigate the molecular mechanism of ER stress–induced apoptosis in SCI. We found that GRP78, CHOP, caspase‐12‐positive cells were expressed in both gray matter and white matter, and the staining was more intense in the gray matter than white matter (Figure 2A). The numbers of CHOP, GRP78, caspase‐12‐positive gray and white matter cells and the optical densities increased significantly; all were maximal at 3 days. After this time, the numbers of positive cells and optical densities gradually decreased but were still observed 7 days after the contusions (Figure 2B,C). The protein expressions of GRP78, CHOP, caspase‐12 were also determined by Western blot analysis. The levels of GRP78, CHOP, caspase‐12 increased 1 day after injury. The maximal induction of all proteins occurred at 3 days and decreased later, 7 days after contusion (Figure 2D,E), which is consistent with the results of immunohistochemistry staining.

Figure 2.

ER stress–induced apoptosis was involved in the early stage of spinal cord injury (SCI). (A) Immunohistochemistry for GRP78, CHOP and caspase‐12 in sham, 1, 3 and 7 days after spinal cord injury lesions groups (B) Analysis of the positive cells and optical density (C) of the immunohistochemistry results. *represents P < 0.05 versus the sham group, **represents P < 0.01 versus the sham group, #represents P < 0.05 versus the 1 day group, and $represents P < 0.05 versus the 3 days group. Data are the mean values ± SEM, n = 6. (D) Protein expressions of GRP78, CHOP and caspase‐12 in the spinal cord segment at the contusion epicenter. β‐actin was used as the loading control and for band density normalization. (E) The optical density analyses of GRP78, CHOP, and caspase‐12 protein. *represents P < 0.05 versus the sham group, **represents P < 0.01 versus the sham group, #represents P < 0.05 versus the 1 day group, and $represents P < 0.05 versus the 3 days group. Data are the mean values ± SEM, n = 6.

bFGF Increased the Survival of Neurons and Improved SCI Recovery

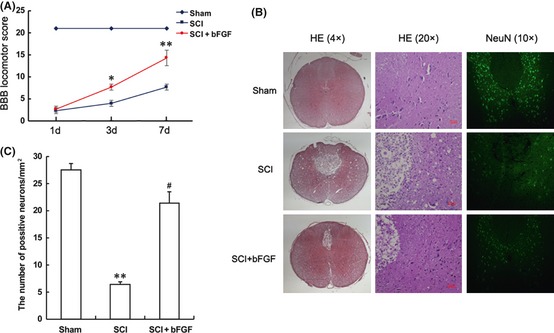

Model rat were treated with bFGF injections close to the wound areas to evaluate the therapeutic effect of bFGF on SCI. The sham group showed normal BBB scores. At 1 day after contusion, there was no significant difference in the BBB scores between SCI model and bFGF treatment groups. However, the BBB scores of the bFGF treatment group increased 3 days after contusion, indicating that the locomotor activity was recovered compared with the SCI group. At 7 days after contusion, the BBB scores of the bFGF treatment group increased to 14.3 ± 1.76, which is markedly increased compared with the SCI group (P < 0.05, Figure 3A). Progressive destruction of the dorsal white matter and central gray matter tissue was found in the 7 days SCI group compared with the sham operation group. Compared with the SCI group, the bFGF treatment group showed significant protective effects, such as less necrosis and karyopyknosis and fewer infiltrated polymorphonuclear leukocytes and macrophages (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) improves the recovery of spinal cord injury (SCI) rat and the survival of neurons. (A) The Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan (BBB) scores of sham, SCI group and SCI rat treated with bFGF group. *represents P < 0.05 versus the SCI group, and **represents P < 0.01 versus the SCI group, n = 6. (B) H and E staining and NeuN staining results of the sham, SCI group and SCI rat treated with bFGF group. The bright green dots in the right column are positive staining neurons. (C) Analysis of the positive neurons of the NeuN staining results. **represents P < 0.01 versus the sham group, and #represents P < 0.01 versus the SCI group, n = 6.

To further confirm the protective effect of bFGF, we investigated the survival of neurons directly by immunofluorescence staining. Spinal cord neurons in both white and gray matter tissue were marked by the neuronal marker, NeuN. The number of positively stained cells decreased significantly 7 days after SCI and increased in the bFGF treatment group (Figure 3B,C). Our data indicated that bFGF administration has a protective effect and significantly improves the SCI recovery.

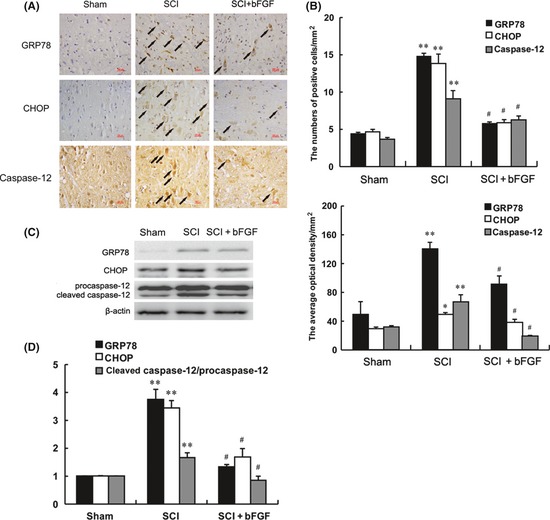

bFGF‐inhibited ER Stress–Induced Apoptosis and Up‐Regulated the Neuroprotective Factors

The protein expressions of ER stress–induced apoptosis were detected by immunohistochemistry staining and Western blot. The ER stress–induced apoptosis protein (CHOP, GRP78 and caspase‐12) positive cells and optical density gradually decreased with bFGF administration 7 days after contusion (Figure 4A,B). We found the levels of the CHOP, GRP78 and caspase‐12 proteins decreased after bFGF treatment as compared with the SCI group, 7 days after contusion (Figure 4C,D) .

Figure 4.

Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) administration inhibits the expressions of ER stress–induced apoptosis response proteins, GRP78, CHOP and caspase‐12. Immunohistochemistry for GRP78, CHOP and caspase‐12 in the sham, 7 days after spinal cord injury lesion and bFGF treatment 7 days after injury groups (A) Analysis of the positive cells and optical density (B) of the immunohistochemistry results. *Represents P < 0.05 versus the sham group, **represents P < 0.01 versus the sham group, #represents P < 0.05 versus the spinal cord injury (SCI) group, Data are the mean values ± SEM, n = 6. (C) Protein expressions of GRP78, CHOP and caspase‐12 for the sham, SCI and bFGF treatment groups. β‐actin was used as the loading control and for band density normalization. (D) The optical density analysis of GRP78, CHOP, and caspase‐12 protein. **represents P < 0.01 versus the sham group, #represents P < 0.05 versus the 1 day group. Data are the mean values ± SEM, n = 6.

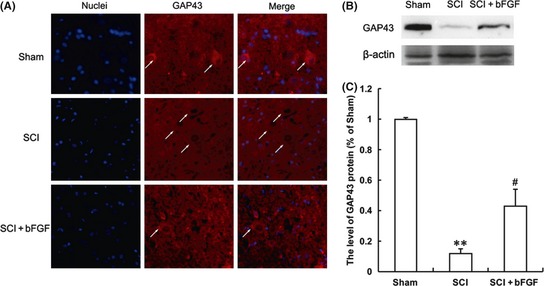

GAP43 is expressed in developing and regenerating neurons, and this protein is often used to score the condition of neural regeneration. We found that the positive red fluorescence signal in the cytoplasm was enhanced in the bFGF administration group but not in the SCI group 7 days after contusion (Figure 5A). Western blot analysis of the GAP43 protein also demonstrated that the expression of GAP43 was greater in the bFGF treatment group than the SCI group 7 days after contusion (Figure 5B,C). This result was consistent with the results of the immunofluorescence staining analysis.

Figure 5.

Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) administration increases the level of GAP43 in spinal cord lesions. (A) Immunofluorescence staining results of GAP43; the nuclear is labeled by Hoechst (blue), the neurons with obvious GAP43 signals are labeled with white arrow heads, magnification was 20×. (B) The protein expressions of GAP43 in the sham, spinal cord injury (SCI) rat and SCI rat treated with bFGF groups. (C) The optical density analysis of GAP43 protein. **represents P < 0.01 versus the sham group, and #represents P < 0.05 versus the SCI group. Data are the mean values ± SEM, n = 6.

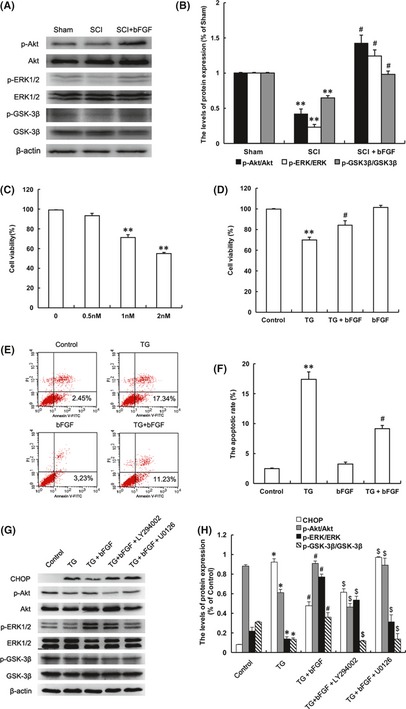

The Protective Role of bFGF was Related to the Activation of PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2

The PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 pathways are the main downstream signals that are activated by bFGF. These two pathways are related to the cell survival, differentiation and migration 24, 25. We determined that the protective effect of bFGF in SCI recovery was partially through the activation of these two signal pathways. Western blot analysis demonstrated decreases in the expressions of the phosphorylations of Akt, ERK1/2 and GSK‐3β (downstream of Akt signal) after SCI contusion. The phosphorylation decreases were reversed in the bFGF treatment group at 7 days (Figure 6A,B). These data indicated that both the PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 signals were involved in the role of bFGF in SCI recovery.

Figure 6.

PI3K/Akt/GSK‐3β and ERK1/2 signal pathways are involved in the protective effect of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) both in the spinal cord of spinal cord injury (SCI) rat and PC12 cells under stress. (A) The protein expressions of p‐Akt/Akt, p‐ERK/ERK, p‐GSK‐3β/GSK‐3β in the sham, SCI model and SCI rat treated with bFGF groups. (B) The optical density analysis of p‐Akt/Akt, p‐ERK/ERK, p‐GSK‐3β/GSK‐3β protein. **represents P < 0.01 versus the sham group, and #represents P < 0.05 versus the SCI group. Data are the mean values ± SEM, n = 6. (C) MTT results of the different concentrations of thapsigargin (TG)‐treated PC12 cells. (D) MTT result of bFGF‐treated PC12 cells induced by TG. (E) FACScan result of PI/Annexin V‐FITC staining for cell apoptosis analysis. (F) Statistical result of apoptosis rate in PC12 cells treated with TG and bFGF. **represents P < 0.01 versus the control group, and #represents P < 0.05 versus the TG group. Data are the mean values ± SEM, n = 3. (G) The protein expressions of CHOP, GRP78, p‐Akt, p‐ERK1/2, p‐GSK‐3β in ER stress–induced apoptosis PC12 cells treated with bFGF and different inhibitors. β‐actin was used as the loading control and for band density normalization. (H) The optical density analysis of CHOP, GRP78, p‐Akt, p‐ERK1/2 and p‐GSK‐3β protein. *represents P < 0.05 versus the control group, #represents P < 0.01 versus the TG group, $represents P < 0.05 versus the TG+bFGF group. Data are the mean values ± SEM, n = 3.

To further confirm the role of bFGF in ER stress–induced apoptosis in vitro, we used TG‐treated PC12 cells (TG is an ER stress activator) to replicate the apoptosis model 26, 27. Cell viability decreased as TG concentration increased, while bFGF combination partially increased cell viability compared with that of the TG group (Figure 6C,D). Cell apoptosis rate was analyzed by flow cytometer, and the results showed that bFGF‐inhibited apoptosis induced by TG in PC12 cells, compared with the TG group (Figure 6E,F). These data indicated that bFGF also had a protective effect in the cell death model.

To demonstrate the molecular mechanism of bFGF in the ER stress‐induced cell apoptosis model, two classic signal inhibitors, LY294002 for PI3K/Akt and U0126 for ERK1/2 were added into the cell stress model. Both of these inhibitors have no effect on cell death when used 22, 28. The activation of CHOP by TG treatment was inhibited by bFGF addition, but the protective effect of bFGF was abolished by LY294002 and U0126. The expression of CHOP increased significantly with the combination of inhibitors, compared with the bFGF treatment group. The levels of p‐Akt, p‐ERK1/2 and p‐GSK‐3β increased with bFGF treatment and decreased with the addition of the inhibitors (Figure 6G,H). All of these data demonstrated that the protective role of bFGF in ER stress–induced apoptosis is related to the activation of downstream signals, PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2, both in vitro and in vivo.

Discussion

Spinal cord crushed injuries have devastating consequences of lifelong disability and significant economic costs. Vertebral impact injury is clinically common, and this type of injury may be caused by traffic accidents, sports injuries or tumors in spinal cords. After a spinal cord crushed injury, the initial traumatic injury to spinal cord tissues is followed by a long period of secondary damages, including oxidative stress, inflammation, necrosis and apoptosis 29, 30. The loss of neuronal cells is the main factor that interferes with recovery from the secondary damage. Many therapeutic interventions using neurotrophic factors have been established to promote functional SCI recovery, such as NGF, BDNF and glial cell line‐derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) 31, 32. In the present study, we treated SCI rat with bFGF and demonstrated the protective effect and molecular mechanism of bFGF in ER stress–induced apoptosis both in vivo and in vitro.

The ER stress pathway was first identified as a cellular response induced by the accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER to preserve the organelle function. The ER stress pathway is also activated by various cellular stress processes that may induce apoptosis to remove damaged cells 33. Previous studies have demonstrated that ER stress–induced apoptosis was one of the main events in secondary damages of a spinal cord injury 5, 11. The increased production and nuclearization of the pro‐apoptotic factor, CHOP, coincides with activation of caspase‐12. In WT and CHOP null mice that received moderate T9 contusive injuries, deletion of CHOP led to an overall attenuation of the UPR after contusive SCI. Furthermore, analyses of hindlimb locomotion demonstrated a significant functional recovery that correlated with an increase in white matter sparing, transcript levels of myelin basic protein and decreased oligodendrocyte apoptosis in CHOP null mice compared with WT animals. This result indicates the important role of CHOP in cell death caused by SCI 11. Therefore, CHOP and caspase 12‐mediated ER stress–induced cell death seems to be the major mediator of apoptotic neuronal death after SCI. This result also implies that CHOP and caspase 12‐mediated ER stress might be a potential therapeutic target to stop the apoptotic course after injury. Moreover, GRP78 is also involved in ER stress–induced apoptosis in serious spinal cord injuries 1, 34. In our study, the levels of these ER stress–induced apoptosis proteins after spinal cord contusions were detected to investigate the molecular mechanism of bFGF in SCI recovery. We found that the expressions of GRP78, CHOP and caspase‐12 increased significantly the first day after SCI. Exogenous bFGF treatment after contusion decreased the levels of ER stress–induced apoptosis proteins and improved locomotor function and SCI recovery. These results indicated the role of bFGF in SCI therapy is related to the inhibition of ER stress response proteins. In addition, protein‐folding stress at the ER is a salient feature of specialized secretory cells and is also involved in the pathogenesis of diseases. ER stress is buffered by the activation of the UPR, and failure to adapt to ER stress results in apoptosis 35. Further study is needed to determine whether inhibition of ER stress–induced apoptosis by bFGF also leads to a reversal of the UPR and subsequently reactivates the innate immunity, metabolism and cell differentiation.

The main downstream signals activated by bFGF, the PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 pathways are essential for the neurotropic effect. The PI3K/Akt pathway is particularly important for mediating neuronal survival under a wide variety of circumstances 14, 36. Akt acts before the release of cytochrome c by regulating Bcl‐2 family member activity and mitochondrial function as well as components of the apoptosome 37, 38. For instance, Akt phosphorylates the pro‐apoptotic Bcl‐2 family member BAD, which inhibits BAD pro‐apoptotic functions 39. In addition to its effects on the cytoplasmic apoptotic machinery, the PI3K/Akt pathway also regulates apoptosis by suppressing the expression of death genes, such as the forkhead box transcription factor by phosphorylating FOXOs (Forkhead box, group O), which is also related to the ERK1/2 signal 36, 40. However, in the neuronal cell death of CNS diseases, it has been reported that PI3K/Akt partially mediates BDNF‐mediated survival. This reveals that neuroprotection by BDNF is also partially dependent on ERK1/2 signaling 41, 42. Activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway is essential for neurotrophin‐mediated survival. Overexpression of Akt not only blocks DNA fragmentation but also suppresses casapse‐3 substrate PARP degradation under growth factor stimulation. Knockdown of Akt expression impairs NGF and BDNF‐mediated H19‐7 hippocampal progenitor cell and primary hippocampal neurons survival 43. As the downstream signal of PI3K/Akt, GSK‐3β also plays an important role in cell death. Phosphorylated GSK‐3β inhibits the opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores (mPTP), which results in the release of cytochrome c to the cytoplasm 44. In particular, a previous study suggested that phosphorylated GSK‐3β provides cardioprotection against myocardial I/R injury 45. In our recent study, bFGF shows a neuronal protective effect in stroke rat model via the activation of both the PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 signals 22. Similarly to our results, Xia also reported that BDNF prevented phencyclidine‐induced apoptosis in the developing brain by the activation of both the PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 pathways 46. In this study, we demonstrated that the role of bFGF in SCI recovery is also related to the activation of both the PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 signals in vivo. To further confirm that these two pathways are essential for the protective effect of bFGF, we used ER stress inducer, TG, treated PC12 cells (combined with PI3K/Akt inhibitor LY294002 or ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126) to show that the apoptosis induced by TG was inhibited by bFGF treatment and further abolished by this combination of inhibitors.

However, there is no doubt that the limitations of bFGF in SCI therapy still need for further study and investigation. For example, a single dose of bFGF was treated right after injury, postinjury treatment of optimal dose and extended time would better evaluate the therapeutic value in the future. In this study, 7‐day outcome may not be long enough, which needs to be further investigated on the long‐term neurological outcome, such as 2–3 weeks or longer period. Moreover, PC12 cell used in vitro is informative, future tests in spinal cord neuron cultures would be more persuasive. Nevertheless, the neuroprotective effect of bFGF following spinal cord contusion injury is confirmed and feasible to improve the pharmacodynamic actions and demonstrate the underlying mechanisms is necessary in the further studies.

In summary, administration of bFGF significantly reduced damage to spinal cord lesions and improved locomotor SCI recovery, which is related to the inhibition of ER stress–induced cell apoptosis. Our study demonstrates the possibility that bFGF therapy may be suitable for recovery from central nervous system injury diseases.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Funding of China (81200958), State Key Basic Research Development Program (2012CB518105), Zhejiang Provincial Project of Key Group (2010R50042‐02), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (R2090550), and Wenzhou Medical College Research Foundation (QTJ11013).

The first three authors contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1. Penas C, Guzman MS, Verdu E, et al. Spinal cord injury induces endoplasmic reticulum stress with different cell‐type dependent response. J Neurochem 2007;102:1242–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dasari VR, Veeravalli KK, Tsung AJ, et al. Neuronal apoptosis is inhibited by cord blood stem cells after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2009;26:2057–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beattie MS. Inflammation and apoptosis: linked therapeutic targets in spinal cord injury. Trends Mol Med 2004;10:580–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jing G, Wang JJ, Zhang SX. ER stress and apoptosis: a new mechanism for retinal cell death. Exp Diabetes Res 2012; 2012: 589589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Badiola N, Penas C, Minano‐Molina A, et al. Induction of ER stress in response to oxygen‐glucose deprivation of cortical cultures involves the activation of the PERK and IRE‐1 pathways and of caspase‐12. Cell Death Dis 2011;2:e149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zha BS, Zhou HP. ER Stress and Lipid Metabolism in Adipocytes. Biochem Res Int 2012; 2012: 312943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ding W, Yang L, Zhang M, Gu Y. Reactive oxygen species‐mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to aldosterone‐induced apoptosis in tubular epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012;418:451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu XD, Ko S, Xu Y, et al. Transient aggregation of Ubiquitinated proteins is a cytosolic unfolded protein response to inflammation and ER stress. J Biol Chem 2012;287:19687–19698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang Z, Tong N, Gong Y, et al. Valproate protects the retina from endoplasmic reticulum stress‐induced apoptosis after ischemia‐reperfusion injury. Neurosci Lett 2011;504:88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Valenzuela V, Collyer E, Armentano D, et al. Activation of the unfolded protein response enhances motor recovery after spinal cord injury. Cell Death Dis 2012;3:e272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ohri SS, Maddie MA, Zhao Y, et al. Attenuating the endoplasmic reticulum stress response improves functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Glia 2011;59:1489–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ohri SS, Maddie MA, Zhang Y, et al. Deletion of the pro‐apoptotic endoplasmic reticulum stress response effector CHOP does not result in improved locomotor function after severe contusive spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2012;29:579–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Itoh N, Ornitz DM. Fibroblast growth factors: from molecular evolution to roles in development, metabolism and disease. J Biochem 2011;149:121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beenken A, Mohammadi M. The FGF family: biology, pathophysiology and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2009;8:235–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xiao J, Lv Y, Lin S, et al. Cardiac protection by basic fibroblast growth factor from ischemia/reperfusion‐induced injury in diabetic rats. Biol Pharm Bull 2010;33:444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abe K, Saito H. Effects of basic fibroblast growth factor on central nervous system functions. Pharmacol Res 2001;43:307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yu Y, Gu S, Huang H, Wen T. Combination of bFGF, heparin and laminin induce the generation of dopaminergic neurons from rat neural stem cells both in vitro and in vivo. J Neurol Sci 2007;255:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu WG, Wang ZY, Huang ZS. Bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells expressing the bFGF transgene promote axon regeneration and functional recovery after spinal cord injury in rats. Neurol Res 2011;33:686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Karimi‐Abdolrezaee S, Eftekharpour E, Wang J, Schut D, Fehlings MG. Synergistic effects of transplanted adult neural stem/progenitor cells, chondroitinase, and growth factors promote functional repair and plasticity of the chronically injured spinal cord. J Neurosci 2010;30:1657–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kishi S, Shimoke K, Nakatani Y, et al. Nerve growth factor attenuates 2‐deoxy‐d‐glucose‐triggered endoplasmic reticulum stress‐mediated apoptosis via enhanced expression of GRP78. Neurosci Res 2010;66:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Oliveira MR, da Rocha RF, Stertz L, et al. Total and mitochondrial nitrosative stress, decreased brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels and glutamate uptake, and evidence of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the hippocampus of vitamin A‐treated rats. Neurochem Res 2011;36:506–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang Z, Zhang H, Xu X, et al. bFGF inhibits ER stress induced by ischemic oxidative injury via activation of the PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 pathways. Toxicol Lett 2012;212:137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jameson MJ, Beckler AD, Taniguchi LE, et al. Activation of the insulin‐like growth factor‐1 receptor induces resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor antagonism in head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2011;10:2124–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Echeverria V, Zeitlin R. Cotinine: a potential new therapeutic agent against Alzheimer's disease. CNS Neurosci Ther 2012;18:517–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pisanti S, Picardi P, Prota L, et al. Genetic and pharmacologic inactivation of cannabinoid CB1 receptor inhibits angiogenesis. Blood 2011;117:5541–5550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shimoke K, Kishi S, Utsumi T, et al. NGF‐induced phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase signaling pathway prevents thapsigargin‐triggered ER stress‐mediated apoptosis in PC12 cells. Neurosci Lett 2005;389:124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Szegezdi E, Herbert KR, Kavanagh ET, Samali A, Gorman AM. Nerve growth factor blocks thapsigargin‐induced apoptosis at the level of the mitochondrion via regulation of Bim. J Cell Mol Med 2008;12:2482–2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu R, Chen J, Cong X, Hu S, Chen X. Lovastatin protects mesenchymal stem cells against hypoxia‐ and serum deprivation‐induced apoptosis by activation of PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2. J Cell Biochem 2008;103:256–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cevikbas F, Steinhoff M, Ikoma A. Role of spinal neurotransmitter receptors in itch: new insights into therapies and drug development. CNS Neurosci Ther 2011;17:742–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moon YJ, Lee JY, Oh MS, et al. Inhibition of inflammation and oxidative stress by Angelica dahuricae radix extract decreases apoptotic cell death and improves functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci Res 2012;90:243–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gelfo F, Tirassa P, De Bartolo P, et al. NPY intraperitoneal injections produce antidepressant‐like effects and downregulate BDNF in the rat hypothalamus. CNS Neurosci Ther 2012;18:487–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang L, Ma Z, Smith GM, et al. GDNF‐enhanced axonal regeneration and myelination following spinal cord injury is mediated by primary effects on neurons. Glia 2009;57:1178–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Appenzeller‐Herzog C, Hall MN. Bidirectional crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum stress and mTOR signaling. Trends Cell Biol 2012;22:274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yamauchi T, Sakurai M, Abe K, Matsumiya G, Sawa Y. Impact of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in spinal cord after transient ischemia. Brain Res 2007;1169:24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012;13:89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, et al. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell 1999;96:857–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yuan Y, Xue X, Guo RB, et al. Resveratrol Enhances the Antitumor Effects of Temozolomide in Glioblastoma via ROS‐dependent AMPK‐TSC‐mTOR Signaling Pathway. CNS Neurosci Ther 2012;18:536–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang H, Kong X, Kang J, et al. Oxidative stress induces parallel autophagy and mitochondria dysfunction in human glioma U251 cells. Toxicol Sci 2009;110:376–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, et al. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell‐intrinsic death machinery. Cell 1997;91:231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Roy SK, Srivastava RK, Shankar S. Inhibition of PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways causes activation of FOXO transcription factor, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in pancreatic cancer. J Mol Signal 2010;5:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Meyer‐Franke A, Wilkinson GA, Kruttgen A, et al. Depolarization and cAMP elevation rapidly recruit TrkB to the plasma membrane of CNS neurons. Neuron 1998;21:681–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yoshii A, Constantine‐Paton M. BDNF induces transport of PSD‐95 to dendrites through PI3K‐AKT signaling after NMDA receptor activation. Nat Neurosci 2007;10:702–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nguyen TL, Kim CK, Cho JH, Lee KH, Ahn JY. Neuroprotection signaling pathway of nerve growth factor and brain‐derived neurotrophic factor against staurosporine induced apoptosis in hippocampal H19‐7/IGF‐IR [corrected]. Exp Mol Med 2010;42:583–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Juhaszova M, Zorov DB, Yaniv Y, et al. Role of glycogen synthase kinase‐3beta in cardioprotection. Circ Res 2009;104:1240–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Miura T, Miki T. GSK‐3beta, a therapeutic target for cardiomyocyte protection. Circ J 2009;73:1184–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xia Y, Wang CZ, Liu J, Anastasio NC, Johnson KM. Brain‐derived neurotrophic factor prevents phencyclidine‐induced apoptosis in developing brain by parallel activation of both the ERK and PI‐3K/Akt pathways. Neuropharmacology 2010;58:330–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]