Abstract

Our aim was to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of anticonvulsant agents for the treatment of acute bipolar mania and ascertain if their effects on mania are a “class” effect. We conducted a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with placebo or active comparator, in acute bipolar mania in order to summarize available data on anticonvulsant treatment of mania/mixed episodes. We searched (PubMed/MEDLINE) with the combination of the words “acute mania” and “clinical trials” with each one of the following words: “anticonvulsants/antiepileptics,”“valproic/valproate/divalproex,”“carbamazepine,”“oxcarbazepine,”“lamotrigine,”“gabapentin,”“topiramate,”“phenytoin,”“zonisamide,”“retigabine,”“pregabalin,”“tiagabine,”“levetiracetam,”“licarbazepine,”“felbamate,” and “vigabatrin.” Original articles were found until November 1, 2008. Data from 35 randomized clinical trials suggested that not all anticonvulsants are efficacious for the treatment of acute mania. Valproate showed greater efficacy in reducing manic symptoms, with response rates around 50% compared to a placebo effect of 20–30%. It appears to have a more robust antimanic effect than lithium in rapid cycling and mixed episodes. As valproate, the antimanic effects of carbamazepine have been demonstrated. Evidences did not support the efficacy of the gabapentin, topiramate as well as lamotrigine as monotherapy in acute mania and mixed episodes. Oxcarbazepine data are inconclusive and data regarding other anticonvulsants are not available. Anticonvulsants are not a class when treating mania. While valproate and carbamazepine are significantly more effective than placebo, gabapentin, topiramate, and lamotrigine are not. However, some anticonvulsants may be efficacious in treating some psychiatric comorbidities that are commonly associated to bipolar illness.

Keywords: Acute mania, Anticonvulsants, Antiepileptics, Bipolar disorder, Randomized placebo‐controlled, Clinical trials, Treatment

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is now recognized as a potentially treatable psychiatric illness with substantial morbidity and mortality and high social and economic impact. Therapies must address the control of acute episodes (manic, depressed, or mixed) and maintenance of remission symptoms [1]. For patients experiencing a manic or mixed episode, the primary goal of treatment is the control of symptoms to allow a return to normal levels of psychosocial functioning. The rapid control of agitation, aggression, and impulsivity is particularly important to ensure the safety of the patient and those around him or her [2].

The number of drugs formally licensed for the treatment of acute bipolar mania has grown substantially over the last 10 years. Lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, and most antipsychotics have shown efficacy in the treatment of acute mania in controlled studies [3]. Thus, the majority of guideline recommendations have suggested valproate or lithium and an antipsychotic as first‐line pharmacological treatment for patients with severe mania. For less ill patients, monotherapy with valproate, lithium, or some antipsychotics may be considered [4].

Given the utility of carbamazepine and valproate for acute bipolar mania, a number of newer anticonvulsants have been assessed in open‐label and controlled trials for their efficacy in the treatment of the various phases of bipolar disorder [5, 6]. The expectations were that the newer drugs would be at least as efficacious as the older ones, with better safety and tolerability. However, a number of negative controlled trials posed the question of whether anticonvulsants actually worked as a class in mania. The objective of this review was to answer this question.

The current article provides a systematic review of the available evidence base of studies of anticonvulsant treatment for acute mania. We reviewed the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (with placebo or active comparator) supporting the efficacy and tolerability of all anticonvulsant agents, and we tried to answer the question of whether anticonvulsants are a class in mania.

Material and Methods

Eligibility Criteria

All anticonvulsant agents were reviewed. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the predefined criteria for the types of study described below:

-

•

RCTs evaluating anticonvulsant treatment of acute mania

-

•

Studies comparing a drug given as monotherapy with a placebo or active comparator arm

-

•

Studies comparing a drug given as cotherapy with a placebo or active comparator arm

Data Sources

The MEDLINE was searched in order to locate clinical trials concerning the anticonvulsant agents frequently used in the treatment of acute mania. The search was last performed in November 1, 2008. In order to locate clinical trials, the MEDLINE was searched with the combination of the words “acute mania” and “clinical trials” with each one of the following words: “anticonvulsants/antiepileptics,”“valproic/valproate/divalproex,”“carbamazepine,”“oxcarbazepine,”“lamotrigine,”“gabapentin,”“topiramate,”“phenytoin,”“zonisamide,”“retigabine,”“pregabalin,”“tiagabine,”“levetiracetam,”“licarbazepine,”“felbamate,” and “vigabantine.” All published works were considered.

A second strategy was applied for valproate and carbamazepine because it seemed that older trials (conducted during the 1970s) were missing from the previous search. The data were graded on the basis of the PORT method [7] as modified for use by the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry for the development of the WFSBP guidelines [8, 9, 10]. Web pages containing lists of clinical trials were also scanned. These sites included http://clinicaltrials.gov and http://www.clinicalstudyresults.org as well as the official sites of all the pharmaceutical companies with products used for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Some of the older studies of the 1970s were difficult to trace on the basis of an electronic search alone. Therefore, the authors scanned relevant review articles and utilized their reference list [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18].

Results of the Literature Search

The MEDLINE search for clinical trials returned 132 articles that appeared to meet the review inclusion criteria described above. However, most of them concerned opinion or review articles, open studies, complex combination, or adjunctive therapy, many times focusing on different agents and only a small minority of articles could be considered as RCTs proper for the agent under consideration. There is still a high degree of variance in these studies concerning their methodological quality, for example, number of patients, use of placebo arm, randomization procedure, and trial duration. In addition, several articles report on different aspects and outcomes of the same trial. Finally, we included 14 studies for valproate (12 original and 2 secondary analysis), 12 studies for carbamazepine, 4 studies for lamotrigine, 2 studies for gabapentin, 2 studies for topiramate, only 1 study for oxcarbazepine, and 1 study for phenytoin (see Table 1). We included also 7 review studies. We did not find controlled studies in bipolar disorder for the other anticonvulsants zonisamide, retigabine, pregabalin, tiagabine, levetiracetam, licarbazepine, felbamate, and vigabantine.

Table 1.

Randomized clinical trials with anticonvulsants

| Drug | Comparator arm | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| VPT | VPT > PLA | All five studies found significantly greater efficacy for valproate compared with placebo, with response rates ranging from 48 to 53%. | [19, 20, 22, 23] |

| VPT = Li | Valproate and lithium were more effective than placebo and appeared similar, although valproate might be better in mixed episodes | [21, 24, 25] | |

| VPT < Li | Valproate was inferior to lithium at serum levels 1.5 mmol/L, but valproate appeared to be effective in manic patients with mixed affective states | [26] | |

| VPT = HAL | Valproate and haloperidol showed antipsychotic response comparable and patients on valproate treatment had minimal side effects | [28] | |

| VPT < OLZ | Olanzapine superior to valproate on YMRS; more olanzapine‐treated patients (47.2%) than valproate (34,1%) were classified as responders | [30] | |

| VPT = OLZ | Equal effectiveness between olanzapine and valproate was observed, but trial was powered for weight gain | [31] | |

| VPT = QUET | Valproate was equal to quetiapine for the treatment of acute manic symptoms in adolescent bipolar disorder | [32] | |

| CBZ | CBZ > PLA | All trials found carbamazepine to be significantly superior to placebo; 61% were identified as responders in the CBZ versus 29% placebo | [38, 39, 40] |

| CBZ × Li | One study found that lithium was superior, while the others found the drugs to be equivalent | [43, 44, 45] | |

| CBZ < VPT | Valproate treatment group showed greater improvement than did the carbamazepine group | [27] | |

| CBZ = CPZ | No differences were found between CBZ and CPZ | [46] | |

| CBZ = HAL | No differences were found between CBZ and HAL | [47] | |

| CBZ + LI = HAL + Li | This result found that CBZ‐Li was as effective as HAL‐Li in the treatment of acute mania; however, HAL‐Li patients had more extrapyramidal side effects | [48] | |

| OXC | OXC = PLA | OXC was not superior to placebo in reduction of manic symptoms in children and adolescents sample | [51] |

| LTG | LTG‐Li = Li‐PLA | There were no significant differences between lamotrigine and placebo groups on changes in YMRS scores or response rates | [53] |

| LTG = PLA = GAB | The response rate for manic symptom improvement (CGI‐I) did not differ significantly among the three treatment groups | [54] | |

| LTG = Li | This pilot study showed that lamotrigine was as effective as lithium in the treatment of acute symptoms | [55] | |

| GAB | GAB = PLA | There were no significant differences in efficacy between gabapentin monotherapy and placebo in improvement in manic symptoms | [54] |

| Li + GAB = Li + PLA | Both treatment groups showed a decrease in YMRS, but this decrease was significantly greater in the placebo | [57] | |

| TOP | TOP = PLA < Li | No found differences between TOP and PLA, whereas patients receiving lithium displayed significantly greater improvement compared with the placebo group | [59] |

| MS + TOP = MS + PLA | There was no difference in the reduction of YMRS score in the topiramate add‐on MD and placebo groups | [61] |

CBZ, carbamazepine; CPZ, chlorpromazine; GAB, gabapentin; HAL, haloperidol; Li, lithium; LTG, lamotrigine; MS, mood stabilizer; OCX, oxcarbazepine; OLZ, olanzapine; OXC, oxcarbazepine; PLA, placebo; QUET, quetiapine; TOP, topiramate; VPT, valproate.

Valproate

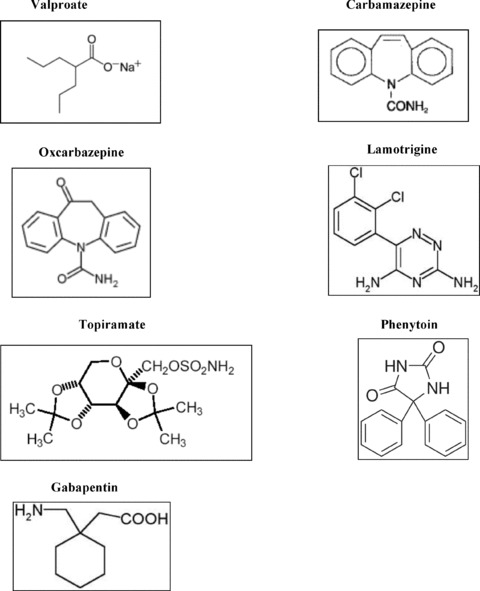

Valproate increases γ‐aminobutyric acid (GABA) synthesis and inhibits GABA metabolism by inhibition of several enzymes related to the tricarboxylic acid cycle and the GABA shunt, that is, succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase and 2‐oxoglutarate dehydrogenase. Acutely, valproate inhibits cerebral energy metabolism by enzyme inhibition, which may modulate neuronal excitability, and this could be of importance in acute treatment of mania. The effect of valproate on voltage‐gated sodium channels, in addition to potassium and calcium channels, is no longer regarded as an important clinically relevant mechanism of action (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Anticonvulsant agents.

Randomized Placebo‐Controlled Studies

Monotherapy

Divalproex and its sodium valproate and valproic acid formulations have been studied in some randomized, placebo‐controlled trials: two small crossover trials [19] and parallel‐group trials [20, 21, 22]. All five studies found significantly greater efficacy for valproate compared with placebo, with response rates ranging from 48 to 53%. A single‐center, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, 21‐day study of 36 inpatients experiencing acute mania who were either nonresponsive or intolerant to lithium was carried out by Pope et al. [20]. Valproate or placebo was administered three times daily for 7–21 days. The valproate serum concentrations were reviewed as well as the dose adjustments were made in order to maintain serum concentrations between 50 and 100 mg/L. At study termination, valproate (mean final dose 2400 mg/day) was shown to be significantly superior to placebo in reducing the symptoms of acute mania and in improving general psychiatric functioning. A robust 54% decrease in scores on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) of patients under valproate versus 5% of patients under placebo was demonstrated [20]. Earlier studies with very small study samples and very different study design were also positive but difficult to interpret [19, 23]. At the dosage loading to serum levels of 85–125 μg/mL, the improvement from baseline was significantly greater among bipolar I (BP‐I) patients hospitalized for acute mania or mixed episodes under divalproex sodium extended release compared with placebo already at day 5. Responders were 48% versus 34% with placebo [22].

Valproate Using Lithium as an Active Comparator Arm

Secondary analyses [24, 25] of data from the largest parallel‐group trial [21] suggested that patients with prominent depressive symptoms during mania (mixed) and with multiple prior mood episodes were more likely to respond to acute treatment with divalproex than with lithium. Divalproex and lithium were equally beneficial on symptoms of hyperactivity and excess energy, but divalproex was more effective in improving elation/grandiosity and reduced need for sleep. Subsequent studies report that divalproex at dosages loading to serum levels of 150 μg/mL produced a 48% response in comparison to 49% for lithium and 25% for placebo [21].

Randomized Controlled Studies without Placebo

Valproate Using Mood Stabilizers (Lithium and Carbamazepine) as Active Comparator Arm

An earlier study suggested that valproate 1500–3000 mg daily was inferior to lithium at serum levels 1.5 mmol/L, but unlike the case with lithium, favorable response to valproate was associated with high pretreatment depression scores, suggesting that treatment with valproate alone may be particularly effective in manic patients with mixed affective states [26].

Valproate was reported to be more effective and faster in action than carbamazepine. In the study carried out by Vasudev et al. [27], 73% of the valproate‐treated patients showed a favorable clinical response while 53% of the patients on carbamazepine responded favorably. Sodium valproate was started with an average dose of approximately 20 mg/kg body weight per day (800–1400 mg/day) in divided doses in day 1, while oral carbamazepine 400 mg/day on day 1 in two divided doses [27].

Valproate Using Antipsychotics as Active Comparator Arm

Another study reported that valproate oral loading (20 mg/kg per day) may produce rapid onset of antimanic and antipsychotic response comparable to that of haloperidol and with minimal side effects in the initial treatment of acute psychotic mania in a subset of bipolar patients [28]. Valproate loading is reported to be safe and well tolerated [29].

Tohen et al. [30] carried out a comparison study where patients hospitalized for acute bipolar manic or mixed episodes were randomly assigned to receive either olanzapine (5–20 mg/day) or divalproex (500–2500 mg/day). The initial daily doses were 15 mg/day of olanzapine and 750 mg/day of divalproex. The results showed that 47.2% of olanzapine‐treated patients had remission of mania symptoms versus 34.1% of valproate‐treated patients. Another study reported equal effectiveness between olanzapine (mean doses 14.7 mg/day) and divalproex sodium delayed release (mean doses 2115 mg/day) with divalproex having more favorable adverse effect profile [31]. In this study, initial medication dosages were 20 mg/kg per day for divalproex delayed release and 10 mg/kg per day for olanzapine; both drugs were administered twice daily. However, difference in their two studies may be explained by different dosing schedules and different serum levels for valproate. Another study reported that divalproex at serum level 80–120 μg/mL (initial dose of 20 mg/kg per day) was equal to 400–600 mg/day quetiapine (initial dose of 100 mg/day) for the treatment of acute manic symptoms associated with adolescent bipolar disorder, but quetiapine might act faster [32].

It has been found that mood stabilizers (lithium or sodium valproate at dosage of 20 mg/Kg per day) in combination with antipsychotics were superior to monotherapy for the rapid control of manic symptoms [33].

Safety and Tolerability

The most common adverse events reported with valproate are central nervous system side effects and gastrointestinal distress. Most adverse events were reported mild to moderate in severity. Other important events included weight gain, hair loss, thrombocytopenia, and hyperammonemic encephalopathy in patients with urea cycle disorders. Rare but serious adverse events include hepatoxicity, pancreatitis, and teratogenicity. However, a retrospective study has demonstrated that children exposed to sodium valproate had lower mean verbal IQ, compared to unexposed and other anticonvulsants (carbamazepine and phenytoin). It suggests that valproate has a potential risk for developmental delay and cognitive impairment [34]. Furthermore, it has been recommended that liver function tests be performed prior to the initiation of treatment and then frequently over the first 6 months of therapy. Pregnancy tests must be ruled out in women with childbearing potential, and contraceptive measures should be in place [35, 36].

Carbamazepine

The main action of carbamazepine is inhibition of voltage‐activated sodium channels and, consequently, inhibition of action potentials and excitatory neurotransmission (see Fig. 1).

Randomized Placebo‐Controlled Studies

Monotherapy

An earlier study utilized withdrawal of carbamazepine and substitution with placebo and reported that 7 out of 9 manic and 5 out of 13 depressed patients had a partial to marked response. Ballenger and Post also showed relapses when placebo was substituted and improvement when carbamazepine was reinstituted at 600–1600 mg/day at blood levels of 8–12 μg/mL [37]. Carbamazepine has been evaluated in three randomized, double‐blind studies that used an extended release formulation of carbamazepine (CBZ‐ERC) as monotherapy for the acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes [38, 39, 40]. All these trials found carbamazepine to be significantly superior to placebo and its antimanic effect became evident after 1–2 weeks. In a study carried out by Weisler et al. [39]. 61% of CBZ‐ERC‐treated patients responded (≥50% decrease in YMRS score) compared with 29% of placebo‐treated patients (P < 0.001). There was a significant increase in percentage of responders showing improvement on the CGI‐I and a significant decrease in HDRS scores in the CBZ‐ERC group versus placebo. The clinical trials suggest that carbamazepine at the dosage of 800 mg/day with a mean plasma drug level of 8.9 μg/mL produces a significant improvement.

Carbamazepine Add‐on Antipsychotics

A recent study found no advantage of adding olanzapine as compared to placebo in patients taking carbamazepine [41]. Something similar happened in the subgroup of patients who were on carbamazepine and risperidone versus carbamazepine monotherapy [42].

Randomized Controlled Studies without a Placebo

Carbamazepine Using Lithium/Valproate as Active Comparator Arm

Three studies have compared carbamazepine with lithium in a randomized controlled manner, with conflicting results. One found that lithium was superior [43], while the other found the drugs to be equivalent [44, 45].

Carbamazepine Using Antipsychotics as Active Comparator Arm

A 5‐week, double‐blind, controlled study was conducted by Okuma et al. [46] where 60 manic patients were randomized to receive carbamazepine or chlorpromazine. This study has found no differences between the drugs [46]. Another 4‐week study compared carbamazepine with haloperidol in 17 patients in manic episode. Although a significant reduction in manic symptoms was seen for both groups within the first week, the findings failed to show a statistically significant difference between groups at days 7 and 14 [47].

Carbamazepine Add‐on Lithium

A double‐blind study found that carbamazepine in combination with lithium (CBZ‐Li) was as effective as lithium and haloperidol (HAL‐Li) in the treatment of acute mania. However, HAL‐Li patients had more extrapyramidal side effects that were major reasons for dropout, whereas CBZ‐Li patients were more often noncompliant and initially required more rescue medications [48].

Safety and Tolerability

The most common adverse events reported with carbamazepine are dizziness, somnolence, ataxia, nausea, vomiting, and diplopia. Other important events less frequently observed include benign skin rashes, mild leucopenia, mild thrombocytopenia, and hyponatremia, which is more common in elderly population. Rare but serious adverse events include agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, and severe dermatologic reactions. There is an increased risk of congenital malformations [35, 36].

Drug–Drug Interactions

Carbamazepine induces medication metabolism, including its own, through cytochrome P‐450 oxidation and conjugation [49]. This enzymatic induction may decrease levels of concomitantly administered medications such as valproate, lamotrigine, oral contraceptives, protease inhibitors, benzodiazepines, and many antipsychotic and antidepressant medications. In addition, carbamazepine has an active epoxide metabolito and is metabolized primarily through a single enzyme, cytochrome P‐450 isoenzyme 3A3/4, making drug–drug interactions even more likely. Consequently, carbamazepine levels may be increased by medications that inhibit the cytochrome P‐450 isoenzyme 3A3/4, such as fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, cimetidine, and some antibiotics and calcium channel blockers. Special caution is also warranted when carbamazepine is used concurrently with clozapine, given the propensity for both drugs to cause leukopenia [50]. Thus, in patients treated with carbamazepine, more frequent clinical and laboratory assessments may be needed with addition or dose adjustments of other medications.

Oxcarbazepine

Oxcarbazepine is a 10‐keto analogue of carbamazepine. Like carbamazepine, its primary mechanism of action is via blockade of sodium channels (see Fig. 1).

Randomized Placebo‐Controlled Studies

Monotherapy

In the only large, multicenter, randomized, placebo controlled trial (7‐week) of oxcarbazepine in acute mania, oxcarbazepine was not superior to placebo in reduction of manic symptoms in children and adolescents sample [51]. There are no double‐blind placebo‐controlled studies on adults.

Lamotrigine

Lamotrigine appears to act via inhibition of presynaptic liberation of glutamate, but it also blocks sodium channels and serotoninergic 5HT receptor (see Fig. 1).

Randomized Placebo‐Controlled Studies

Monotherapy

There are two unpublished negative trials of 3 and 6 weeks duration treatment of acute manic episodes (SCAA20 SCAA2008 and SCAA2009) [52].

Lamotrigine Using Lithium as Active Comparator Arm

In a study, 16 outpatients with mania, hypomania, or mixed episodes who were inadequately responsive to or unable to tolerate lithium were randomly assigned to lamotrigine or placebo as mono or adjunctive therapy [53]. There were no significant differences between lamotrigine and placebo groups on changes in YMRS scores or response rates.

Lamotrigine Using Gabapentin as Active Comparator Arm

Patients with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder (n = 28) were assessed in a double‐blind, randomized, crossover series of three 6‐week monotherapy trials of lamotrigine, gabapentin, or placebo [54]. The response rate for manic symptom improvement, as measured by the Clinical Global Impression Scale for Bipolar Illness, did not differ significantly among the three treatment groups.

Randomized Controlled Studies without Placebo

Lamotrigine Using Lithium as Active Comparator Arm

There is one small pilot study reporting that lamotrigine was as effective as lithium in the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder hospitalized for acute mania [55].

Safety and Tolerability

Skin rashes with lamotrigine tend to appear with rapid dose titration and concomitant valproate administration. The majority of lamotrigine‐induced rashes occur within 2–8 weeks of therapy, although they may occur later. Most rashes are benign (10%), but in a small minority of cases (0.3%), the rash may herald or progress to more serious life‐threatening conditions such as Stevens–Johnsons syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. However, subsequent studies have shown that the rate of serious rash has decreased while that of the benign rash has changed. Symptoms associated with serious rashes include systemic symptoms, lesions on palms, soles, or mucous membranes, and blisters or a painful rash. All the patients treated with lamotrigine should receive clear instructions about rash and the need to contact their physician immediately should a rash occur. Rash should be carefully evaluated and lamotrigine should be immediately discontinued if a serious rash is suspected [56].

Gabapentin

Gabapentin was originally synthesized as an analogue of GABA with a GABAergic profile and action, thereby providing antiepileptic, anxiolytic, and analgesic activity (see Fig. 1).

Randomized Placebo‐Controlled Studies

Add‐on Mood Stabilizers

Another controlled trial [57] compared gabapentin with placebo added to lithium, valproate, or both in 114 outpatients with manic, hypomanic, or mixed symptoms. Both treatment groups displayed a decrease in YMRS scores from baseline to endpoint, but this decrease was significantly greater in the placebo group.

Randomized Controlled Studies without Placebo

Carbamazepine Using Gabapentin and Lamotrigine as Active Comparator Arm

A total of 59 patients met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV) criteria for dysphoric mania entered the double‐blind, fixed dose, randomized study (8‐week) in order to compare the efficacy of carbamazepine (600 mg/day), gabapentin (900 mg/day), and lamotrigine (100 mg/day). A significant change in mean total score on both the depression and mania subscales was observed following treatment for each of the three groups. However, the mean change of total mania scores was greater in gabapentin than in carbamazepine (P= 0.046), particularly greater improvement in psychomotor acceleration. Significantly greater improvement in the mean total score on depression was also observed in the gabapentin group when compared to lamotrigine (P= 0.000) and in gabapentin and lamotrigine as compared to carbamazepine (P= 0.000, P= 0.040, respectively). Gabapentin provided significantly greater symptom improvement in depression scores than lamotrigine, which might be related to a lower baseline depression score in lamotrigine group [58].

Safety and Tolerability

The most common treatment‐emergent adverse events are somnolence fatigue ataxia and weigh gain.

Topiramate

Topiramate's mechanism combines selective blockade of glutamate receptors with a calcium‐antagonist action, potentiation of GABA, and inhibition of carbonic anhydrase (see Fig. 1).

Randomized Placebo‐Controlled Studies

Topiramate Using Lithium as Active Comparator

Recently, the negative results of four placebo‐controlled, randomized 3‐week trials concerning the use of topiramate against acute mania were published [59]. Patients receiving topiramate did not display reductions in manic symptoms greater than patients receiving placebo, whereas patients receiving lithium displayed significantly greater improvement compared with the placebo group. However, topiramate was not associated with mood destabilization measured as mania exacerbation or treatment‐emergent depression. Topiramate causes weight loss and for this reason it has been used in combination with drugs such as olanzapine to avoid weight gain [60], but given its lack of antimanic efficacy and side effects, its use in bipolar disorder is not warranted.

Add‐on Mood Stabilizers

Manic/mixed patients on therapeutic levels of valproate or lithium received adjunctive topiramate or placebo during 12 weeks. There was no difference in the reduction of YMRS score between topiramate and placebo groups [61].

Safety and Tolerability

The most common treatment‐emergent adverse events are central nervous system side effects and gastrointestinal distress. Paresthesia, appetite decrease, dry month, and weight gain were reported frequently [59].

Other Anticonvulsants

No randomized controlled trials were found for felbamate, vigabantine, tiagabine, pregabalin, zonisamide, levetiracetam, retigabine, licarbazepine, and vigabantine. One small placebo‐controlled trial assessed the efficacy of phenytoin add‐on on haloperidol in mania [62]. Patients on phenytoin and haloperidol treatment showed reduction in BPRS scores and improvement in CGI, and no difference was found in YMRS scores compared with placebo group. Pregabalin may be used in anxiety disorders associated to bipolar disorder, but no data are available on its use as mood stabilizer.

Discussion

The goals of treatment in bipolar disorder (BD) differ according to the phase of illness and the prevailing mood state. In the acute phase, treatment is aimed at stabilizing the current mood episode with the goal of achieving remission [63, 64]. The current review performs data from randomized placebo and non‐placebo‐controlled studies of anticonvulsant agents used for the treatment of acute mania. In addition to pooling information from these trials on efficacy, we have also included information of safety and tolerability.

Not all anticonvulsants are useful for the treatment of acute mania, and there is no class effect for this group in bipolar disorder. Both valproate and carbamazepine have shown efficacy in the treatment of acute mania in RCTs [20, 40]. Valproate therapeutic serum concentration is 50–150 mg/mL and its response rate against acute mania is about 50%, versus placebo effect equal to 20–30%[22]. Valproate is more effective than lithium among patients with mixed episodes and patients with multiple episodes [24, 25]. Furthermore, valproate oral loading (20 mg/kg per day) may produce antipsychotic response comparable to that of haloperidol with fewer side effects in the initial treatment of acute psychotic mania [28]. Evidences suggested that combination treatments, with antipsychotics, may be superior to valproate monotherapy for the rapid control of manic symptoms [18, 33, 35].

Carbamazepine in doses ranged from 600 to 1800 mg/day (blood concentration 4–12 mg/mL) has also been considered an option for the treatment of acute mania [38, 39, 40]. However, in the Multicentre study of long‐term treatment of affective and schizoaffective psychoses (MAP) studies, carbamazepine was inferior to lithium for the treatment of classic mania. Carbamazepine provides hepatic enzymes (CYP 3A4) induction that lowers drug levels and may require additional upward dose titration, after some weeks of treatment [49]. Although carbamazepine appears to be less tolerable than valproate for short‐term treatment because of the high incidence of side effects (e.g., gastrointestinal effects, sedation, ataxia, and asthenia), it may offer some advantages in terms of weight gain, polycystic ovarian syndrome, bone loss, and teratogenicity [65].

In opposite to valproate and carbamazepine, lamotrigine was ineffective in alleviating acute manic symptoms either monotherapy or cotherapy with lithium [53, 54]. Topiramate also failed to demonstrate clinical efficacy in bipolar patients with mania [58]. However, its potential application is being geared toward patients who are overweight or who have comorbid eating disorders, as well as those with alcohol dependence [5]. Similarly, the efficacy of the gabapentin as antimanic treatment has not been established in RCTs [54]. Gabapentin may be a useful option for augmentation of the mood stabilizers in the many patients that suffer from high levels of anxiety or with rapid cycling disorder [5]. Regarding other newer anticonvulsants, data from randomized controlled studies are not reliable.

It must be pointed out that unlike antipsychotics, which seem to have a possibly antidopaminergic “class effect” limited to the treatment of acute mania, anticonvulsants have no such effect in any phase of bipolar disorder. Each agent has a very distinct structures and pharmacologic profile, thus should be considered separately. In general, the antimanic action of anticonvulsants has been associated with their “antikindling” mechanism, according to an animal model studied in epilepsy, with an overall stabilizing effect on neuronal membrane.

In conclusion, this article suggests that anticonvulsants have not a “class effect” in the treatment of acute bipolar mania. On other words, only valproate and carbamazepine have efficacy in treating manic symptoms while others do not. A possible explanation is that the anticonvulsants are exceptionally heterogeneous in mechanism of action, efficacy, and safety profile. Unlike antipsychotics, which are structurally very similar, most anticonvulsants have only in common their ability to work in animal models of epilepsy.

Conflict of Interest

Eduard Vieta received grant/research support from Almirall, Astra‐Zeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, the European 7th Framework Program, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen‐Cilag, Novartis, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi‐Aventis, Seny Foundantion, Servier, the Spanish Ministry of Health (CIBERSAM), the Spanish Ministry of Science and Education, and the Sr¡tanley Medical Research Institute. Eduard Vieta has served as consultant for Astra‐Zeneca, Bristol‐Myers, Squibb, Eli Lilly, Forest Research Institute, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Jazz, Lundbeck, Novartis, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi‐Aventis, Servier, and UBC. He has been a member of the speakers boards from Almirall, Astra‐Zeneca, Bristol‐Myers, Eli Lilly, Esteve, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Lundbeck, Novartis, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi‐Aventis, and Servier.

Adriane Ribeiro Rosa has been a member of the speakers boards from Astra‐Zeneca.

Dr. Fountoulakis is member of the International Consultation Board of Wyeth for desvenlafaxine, national coordinator for the trial CL3‐20098‐062 and has received honoraria for lectures from AstraZeneca, Janssen‐Cilag, Eli‐Lilly, and research grants from AstraZeneca, Wyeth, Pfizer, Janssen, Lilly, and Pfizer Foundation.

Dr. Xenia Gonda has received travel grants from Richter, GlaxoSmithkline, Schering plough, Organon, Krka, and Lilly.

References

- 1. Fountoulakis KN, Vieta E, Siamouli M, Valenti M, Magiria S, Oral T, Fresno D, Giannakopoulos P, Kaprinis GS. Treatment of bipolar disorder: A complex treatment for a multi‐faceted disorder. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2007;6:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hirschfeld RMA, Keck CPE, Gitlin MJ, Price LH, Sajatovic M, Suples M, Thase ME, Perlis RH. Practice Guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. Third Edition, Am J Psychiatry, in press. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bowden CL, Karren NU. Anticonvulsants in bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006;40:386–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fountoulakis KN, Vieta E. Treatment of bipolar disorder: A systematic review of available data and clinical perspectives. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2008;11:999–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vieta E, Sugranyes G, Goikolea JM. New anticonvulsants in bipolar disorder: All that glisters is not gold. Adv Schizophr Clin Psychitray 2008;4:106–113. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vieta E, Sanchez‐Moreno J. Acute and long‐term treatment of mania. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2008;10:165–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Translating research into practice: The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophr Bull 1998;24:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grunze H, Kasper S, Goodwin G, Bowden C, Baldwin D, Licht R, Vieta E, Moller HJ. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of bipolar disorders. Part I: Treatment of bipolar depression. World J Biol Psychiatry 2002;3:115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grunze H, Kasper S, Goodwin G, Bowden C, Baldwin D, Licht RW, Vieta E, Moller HJ. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for the Biological Treatment of Bipolar Disorders, Part II: Treatment of mania. World J Biol Psychiatry 2003;4:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grunze H, Kasper S, Goodwin G, Bowden C, Moller HJ. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders, part III: Maintenance treatment. World J Biol Psychiatry 2004;5:120–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bech P. The Bech‐Rafaelsen Mania Scale in clinical trials of therapies for bipolar disorder: A 20‐year review of its use as an outcome measure. CNS Drugs 2002;16:47–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cipriani A, Rendell JM, Geddes JR. Haloperidol alone or in combination for acutemania. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;3:CD004362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davis JM, Janicak PG, Hogan DM. Mood stabilizers in the prevention of recurrent affective disorders: A meta‐analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999;100:406–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Macritchie K, Geddes JR, Scott J, Haslam D, de Lima M, Goodwin G. Valproate foracute mood episodes in bipolar disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;CD004052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Macritchie KA, Geddes JR, Scott J, Haslam DR, Goodwin GM. Valproic acid,valproate and divalproex in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;CD003196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rendell JM, Gijsman HJ, Keck P, Goodwin GM, Geddes JR. Olanzapine alone or incombination for acute mania. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;CD004040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rendell JM, Gijsman HJ, Bauer MS, Goodwin GM, Geddes GR. Risperidone alone or in combination for acute mania. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;CD004043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Warnock A, Tacchi MJ, Taylor D. Acute bipolar mania: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of co‐therapy vs. monotherapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007;115:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Emrich HM, von Zerssen D, Kissling W, Möller HJ. Therapeutic effect of valproate in mania. Am J Psychiatry 1981;138:256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pope HG Jr, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Hudson JI. Valproate in the treatment of acute mania. A placebo‐controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991;48:62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Petty F, Dilsaver SC, Davis JM, Rush AJ, Small JG. Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. The Depakote Mania Study Group. JAMA 1994;271:918–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bowden CL, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Rubenfaer LM, Wozniak PJ, Collins MA, Abi Saab W, Saltarelli M. A randomized, placebo‐controlled, multicenter study of divalproex sodium extended release in the treatment of acute mania. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1501–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Emrich HM, von Zerssen D, Kissling W, Möller HJ, Windorfer A. Effect of sodium valproate on mania. The GABA‐hypothesis of affective disorders. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 1980;229:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Swann AC, Bowden CL, Morris D, Calabrese JR, Petty F, Small J, Dilsaver SC, Davis JM. Depression during mania. Treatment response to lithium or divalproex. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Swann AC, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Dilsaver SC, Morris DD. Differential effect of number of previous episodes of affective disorder on response to lithium or divalproex in acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1264–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Freeman TW, Clothier JL, Pazzaglia P, Lesem MD, Swann AC. A double‐blind comparison of valproate and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1992;149:108–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vasudev K, Goswami U, Kohli K. Carbamazepine and valproate monotherapy: Feasibility, relative safety and efficacy, and therapeutic drug monitoring in manic disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;150:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McElroy SL, Keck PE, Stanton SP, Tugrul KC, Bennett JA, Strakowski SM. A randomized comparison of divalproex oral loading versus haloperidol in the initial treatment of acute psychotic mania. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57:142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hirschfeld RM, Allen MH, McEvoy JP, Keck PE Jr, Russell JM. Safety and tolerability of oral loading divalproex sodium in acutely manic bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60:815–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tohen M, Baker RW, Altshuler LL, et al Olanzapine versus divalproex in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:1011–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zajecka JM, Weisler R, Sachs G, Swann AC, Wozniak P, Sommerville KW. A comparison of the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of divalproex sodium and olanzapine in the treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:1148–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. DelBello MP, Kowatch RA, Adler CM, Stanford KE, Welge JA, Barzman DH, Nelson E, Strakowski SM. A double‐blind randomized pilot study comparing quetiapine and divalproex for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006;45:305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Müller‐Oerlinghausen B, Retzow A, Henn FA, Giedke H, Walden J. Valproate as an adjunct to neuroleptic medication for the treatment of acute episodes of mania: A prospective, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicenter study. European Valproate Mania Study Group. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Adab N, Kini U, Vinten J, et al The longer term outcome of children born to mothers with epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:1575–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bowden CL. Valproate. Bipolar Disord 2003;5:189–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nasrallah HA, Ketter TA, Kalali AH. Carbamazepine and valproate for the treatment of bipolar disorder: A review of the literature. J Affect Disord 2006;95:69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ballenger JC, Post RM. Carbamazepine in manic‐depressive illness: A new treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1980;137:782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weisler RH, Kalali AH, Ketter TA. A multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of extended‐release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy for bipolar disorder patients with manic or mixed episodes. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:478–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Weisler RH, Keck PE Jr, Swann AC, Cutler AJ, Ketter TA, Kalali AH. Extended‐release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy for acute mania in bipolar disorder: A multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weisler RH, Hirschfeld R, Cutler AJ, Gazda T, Ketter TA, Keck PE, Swann A, Kalali A. Extended‐release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy in bipolar disorder: Pooled results from two randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials. CNS Drugs 2006;20:219–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tohen M, Bowden CL, Smulevich AB, et al Olanzapine plus carbamazepine v. carbamazepine alone in treating manic episodes. Br J Psychiatry 2008;192:135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yatham LN, Grossman F, Augustyns I, Vieta E, Ravindran A. Mood stabilisers plus risperidone or placebo in the treatment of acute mania. International, double‐blind, randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lerer B, Moore N, Meyendorff E, Cho SR, Gershon S. Carbamazepine versus lithium in mania: A double‐blind study. J Clin Psychiatry 1987;48:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Small JG, Klapper MH, Milstein V, Kellams JJ, Miller MJ, Marhenke JD, Small IF. Carbamazepine compared with lithium in the treatment of mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991;48:915–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Okuma T, Yamashita I, Takahashi R, et al Comparison of the antimanic efficacy of carbamazepine and lithium carbonate by double‐blind controlled study. Pharmacopsychiatry 1990;23:143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Okuma T, Inanaga K, Otsuki S, et al Comparison of the antimanic efficacy of carbamazepine and chlorpromazine: A double‐blind controlled study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1979;66:211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Brown D, Silverstone T, Cookson JD. Carbamazepine compared to haloperidol in acute mania. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1989;4:229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Small JG, Klapper MH, Marhenke JD, Milstein V, Woodham GC, Kellams J. Lithium combined with carbamazepine or haloperidol in the treatment of mania. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995;31:265–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stoner SC, Nelson LA, Lea JW, Marken PA, Sommi RW, Dahmen MM. Historical review of carbamazepine for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Pharmacotherapy 2007;27:68–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Flanagan RJ, Dunk L. Hematological toxicity of drugs used in psychiatry. Hum Psychopharmacol 2008;23(Suppl 1):27–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wagner KD, Kowatch RA, Emslie GJ, et al A double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial of oxcarbazepine in the treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:1179–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ghaemi NS, Arshia A, Shirzadi DO, Filkowoki M. Publication bias and the pharmaceutical industry: The case of lamotrigine in bipolar disorder. Medscape J Med 2008;10:211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Anand A, Oren DA, Bernan RM. Lamotrigine treatment lithium failure in outpatients mania: A double‐blind, placebo controlled trial In: Soares JC, Gershon S, editors. (Abstract book), Third international bipolar conference, Pithsburg : Munksgaard, 1999; 23. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Frye MA, Ketter TA, Kimbrell TA, Dunn RT, Speer AM, Osuch EA, Luckenbaugh DA, Cora‐Ocatelli G, Leverich GS, Post RM. A placebo‐controlled study of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:607–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ichim L, Berk M, Brook S. Lamotrigine compared with lithium in mania: A double‐blind randomized controlled trial. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2000;12:5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yatham LN, Kusumakar V, Calabrese JR, Rao R, Scarrow G, Kroeker G. Third generation anticonvulsants in bipolar disorder: A review of efficacy and summary of clinical recommendations. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pande AC, Crockatt JG, Janney CA, Werth JL, Tsaroucha G. Gabapentin in bipolar disorder: A placebo‐controlled trial of adjunctive therapy. Gabapentin Bipolar Disorder Study Group. Bipolar Disord 2000;2:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mokhber N, Lane CJ, Azarpazhooh MR, Salari E, Fayazi R, Shakeri MT, Young AH. Anticonvulsivant treatments of dysphoric mania: A trial of gabapentin, lamotrigin and carbamazepine in Iran. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2008;41:227–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kushner SF, Khan A, Lane R, Olson WH. Topiramate monotherapy in the management of acute mania: Results of four double‐blind placebo‐controlled trials. Bipolar Disord 2006;8:15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Vieta E, Sánchez‐Moreno J, Goikolea JM, Torrent C, Benabarre A, Colom F, Martínez‐Arán A, Reinares M, Comes M, Corbella B. Adjunctive topiramate in bipolar II disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry 2003;4:172–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chengappa KN, Schwarzman LK, Hulihan JF, Xiang J, Rosenthal NR. Clinical Affairs Product Support Study‐168 Investigators . Adjunctive topiramate therapy in patients receiving a mood stabilizer for bipolar I disorder: A randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1698–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mishory A, Yaroslavsky Y, Bersudsky Y, Belmaker RH. Phenytoin as an antimanic anticonvulsant: A controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:463–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vieta E, Rosa AR. Evolving trends in the long‐term treatment of bipolar disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry 2007;8:4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Amann B, Grunze H, Vieta E, Trimble M. Antiepileptic drugs and mood stability. Clin EEG Neurosci 2007;38:116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Isojärvi JI, Airaksinen KE, Repo M, Pakarinen AJ, Salmela P, Myllylä VV. Carbamazepine, serum thyroid hormones and myocardial function in epileptic patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1993;56:710–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]