Abstract

Adenosine–dopamine interactions in the central nervous system (CNS) have been studied for many years in view of their relevance for disorders of the CNS and their treatments. The discovery of adenosine and dopamine receptor containing receptor mosaics (RM, higher‐order receptor heteromers) in the striatum opened up a new understanding of these interactions. Initial findings indicated the existence of A2AR‐D2R heterodimers and A1R‐D1R heterodimers in the striatum that were followed by indications for the existence of striatal A2AR‐D3R and A2AR‐D4R heterodimers. Of particular interest was the demonstration that antagonistic allosteric A2A‐D2 and A1‐D1 receptor–receptor interactions take place in striatal A2AR‐D2R and A1R‐D1R heteromers. As a consequence, additional characterization of these heterodimers led to new aspects on the pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease (PD), schizophrenia, drug addiction, and l‐DOPA‐induced dyskinesias relevant for their treatments. In fact, A2AR antagonists were introduced in the symptomatic treatment of PD in view of the discovery of the antagonistic A2AR–D2R interaction in the dorsal striatum that leads to reduced D2R recognition and Gi/o coupling in striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons. In recent years, indications have been obtained that A2AR‐D2R and A1R‐D1R heteromers do not exist as heterodimers, rather as RM. In fact, A2A‐CB1‐D2 RM and A2A‐D2‐mGlu5 RM have been discovered using a sequential BRET‐FRET technique and by using the BRET technique in combination with bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Thus, other pathogenic mechanisms beside the well‐known alterations in the release and/or decoding of dopamine in the basal ganglia and limbic system are involved in PD, schizophrenia and drug addiction. In fact, alterations in the stoichiometry and/or topology of A2A‐CB1‐D2 and A2A‐D2‐mGlu5 RM may play a role. Thus, the integrative receptor–receptor interactions in these RM give novel aspects on the pathophysiology and treatment strategies, based on combined treatments, for PD, schizophrenia, and drug addiction.

Keywords: Addiction, Basal ganglia, GPCRs, Movement disorders/Parkinson's disease, Neuropsychopharmacology, Receptor–receptor interactions, Receptor mosaics, Schizophrenia

Introduction

Role of Dopamine and Adenosine as Volume Transmission Signals in the Central Nervous System

The first observation that led to the discovery of a mode of communication different from synaptic transmission was the appearance of extra‐neuronal dopamine (DA) fluorescence around midbrain DA nerve cells following amphetamine, a catecholamine (CA) releasing drug, treatment in reserpine‐nialamide‐l‐DOPA treated rats [1]. Locally applied CA into the striatum was also found to migrate to the neuropil [2, 3]. Such observations taken together with the existence of global monoamine terminal networks in the central nervous system (CNS) and with several other observations in the literature, in particular the demonstration of large numbers of nonjunctional monoamine varicosities by Descarries [4], led Agnati and Fuxe to propose the existence of volume transmission (VT) as complementary transmission to the well‐known wiring transmission (WT), or synaptic transmission, in the CNS [5]. VT in the CNS was introduced as an extracellular fluid (ECF) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) form of transmission [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. In this way, VT signals are chemical signals like neurotransmitters, trophic factors, ions, peptides, etc. that migrate by diffusion and convection from the source cells to the target cells in the ECF and CSF in VT channels of the extracellular space and the ventricles as a consequence of energy gradients that create migration.

Evidence exists and suggests that the main mode of communication of all the central DA neurons is short distance VT in the micrometer range in which DA primarily reaches extrasynaptic receptors; see [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Thus, DA via VT in the local circuits of the medium‐sized striatal neurons reaches and activates extrasynaptic D1R‐ and D2R‐containing Receptor Mosaics (RM) (see later) on the dendritic spines of such neurons [15]. In many regions, DA exists as a diffusing VT signal in the ECF in concentrations that vary with the pattern of DA release and has a major impact on the modulation of the polymorphic wiring networks in the CNS [16, 17]. In this way it becomes possible to understand how the DA terminal networks have such a powerful role in CNS functions involving mood, reward, fear, cognition, attention, arousal, motor function, neuroendocrine, and autonomic function and indeed play a central role in neuropsychopharmacology.

Adenosine is an endogenous nucleoside and functions as a neuromodulator in many areas of the CNS, see [18, 19, 20]. It is a normal cellular constituent and its intracellular concentration is dependent on the breakdown and synthesis of ATP, which is metabolized to adenosine monophosphate (AMP). Adenosine is then formed from AMP, through the action of a 5′‐nucleotidase, and the intracellular and extracellular concentrations are kept in equilibrium by means of equilibrative transporters. The two main metabolic pathways of adenosine removal depend on the enzymes adenosine deaminase (ADA) (mostly intracellular) and adenosine kinase. Extracellular adenosine concentration depends on intracellular adenosine and also on extracellular ATP (released as a neurotransmitter or as an intracellular signal, from neurons or glial cells) that is rapidly hydrolyzed to adenosine and other metabolites. However, the main source of extracellular adenosine is likely intracellular adenosine released from active cells in response to an increased metabolic demand [19, 20]. Based on its presence in and its release into the ECF, together with the demonstration of extrasynaptic adenosine receptors, adenosine likely represents an important VT signal [18].

The two major adenosine receptors in the CNS are the adenosine A1 and A2A receptors. A1R are widely distributed in the brain are mainly expressed in the hippocampus, cerebellum and neocortical areas. On the other hand, A2AR have a much more restricted brain distribution, in which the striatum contains the highest density in the brain and where they are specially concentrated in the GABAergic striato‐pallidal neurons [11, 17, 18] together with the D2R. The D1R are instead predominantly found in the direct pathway, the striato‐entopeduncular and striato‐nigral GABAergic neurons, see [14, 15].

It has been many years since the hypothesis was first introduced that adenosine–dopamine interactions in the brain primarily take place via receptor–receptor interactions in A2AR‐D2R and A1R‐D1R heteromers located perisynaptically at glutamate synapses on the striato‐pallidal and striato‐entopeduncular/nigral GABAergic neurons, respectively, see [21, 22, 23, 24, 25]. However, although it may be a rather infrequent event, it is possible that adenosine, via VT into DA synapses may directly modulate synaptic DA transmission via synaptic A2AR‐D2 and A1R‐D1R heteromers.

The Concept of Receptor Mosaic and its Implication: Stoichiometry Versus Topology

Already in 1980 it was proposed by Fuxe and Agnati that assemblages of receptors could operate as integrative input units of membrane associated molecular circuits [26, 27]. This postulation was supported by indirect evidence on the existence of receptor–receptor interactions obtained through an analysis of the effects of neuropeptides on the binding characteristics of monoamine receptors in membrane preparations from discrete brain regions [28, 29, 30]. As a logical consequence for the indications of direct physical interactions between neuropeptide and monoamine receptors, the well‐known terms heteromerization versus homomerization were introduced by the Agnati and Fuxe teams as well as by other groups to describe this kind of interaction between different types of GPCRs, see [21, 23, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37].

Allosteric events were postulated to be the molecular mechanism for intra‐membrane interactions in multimeric assemblages of receptors. Thus, the term RM [8, 35, 38, 39] was introduced for assemblies of multiple receptors of the same or different kinds (n≥ 3) in the plasma membrane as a more meaningful term than higher‐order heteromers, which nevertheless is highly relevant from a stoichiometric point of view. The term RM indicates the “integrated output” of such an input unit because it also stresses the concept that topology (spatial localization in the plane of the membrane) and integrative function of the receptor assemblage are deeply interconnected. In other words, the emergent properties of the receptor assemblage, or its integrated output, depend on the location and the order of activation of the participating receptors as well as on the type of allosteric interactions (entropic and/or enthalpic) within such an integrative RM [16, 17]. Already in the 1982 [39] it was proposed that formation of a RM and/or its allosteric change could have a role in the molecular basis for the engram by leading to a transient and/or permanent change of the synaptic efficacy (i.e., the synaptic weight). The term RM maintains that allostery is any ligand‐induced change in protein conformation and/or dynamics but also includes the functional characteristic of allostery, namely that one ligand alters the functional response of another ligand through a conformational change in the binding site of the second ligand, see [16, 17, 40, 41, 42]. It is then possible that a GPCR can have very different biochemical properties leading to a different pharmacology through interactions with another GPCR [15, 16, 17, 21, 35, 43, 44, 45].

The field of receptor–receptor interactions has opened up new targets for drug development [15, 17, 21, 44] and several strategies can be exploited to develop new drugs based on receptor–receptor interactions in receptor heteromers, see [46]. Higher‐order receptor heteromers (receptor mosaics) also offer several additional targets for drug development. Novel drugs may be developed to modify the composition of RMs, their topography, the order of activation as well as allosteric regulators modulating the functional state of the individual receptors in the RM. Drugs may affect, for example, (I) the synthesis and release of receptor oligomeric building blocks from the endoplasmic reticulum, (II) the insertion of such building blocks into the plasma membrane, (III) the internalization of RMs, (IV) the adapter and scaffolding proteins organizing the RMs, and (V) ligand induced receptor assembly.

The potential importance of developing allosteric modulators has also been suggested since they may, inter alia, substantially affect the allosteric mechanisms within the RM leading to changes in its integrative function [47, 48, 49] in addition to affects on RM assemblage, G protein, β‐arrestin coupling and receptor recognition [41, 50]. An example is the discovery of an allosteric D2R antagonist homocysteine (Hcy), which reduces D2R agonist binding and D2R function by its apparent binding to the third intracellular loop (IC3) of the D2R [47, 48]. This discovery opens up the development of new antipsychotic drugs based on the development of allosteric Hcy agonist analogues and antiparkinsonian drugs based on the development of allosteric Hcy antagonist analogues.

In the present review we will focus on the A2AR‐D2R heteromers and A2AR‐D2R‐containing RM as well as the A1R‐D1R heteromers and the A1R‐D1R‐containing RM as targets for the development of novel treatments of CNS diseases.

A2A‐D2‐like Receptor Heteromers and A2AR‐D2R Containing Receptor Mosaics

A2AR‐D2R Heteromers

Biochemical and Functional Findings

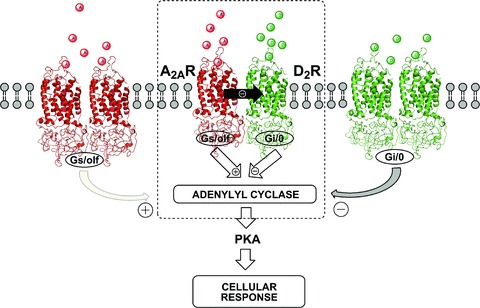

Initially, to tackle the study of receptor heteromers traditional biochemical protocols were used and some of those methods include microscopy‐based procedures, such as co‐immunolocalization, and immobilized protein–protein interaction assays, such as co‐immunoprecipitation. The invasive nature of these technical approaches to study protein–protein interactions still have the disadvantage of altering the natural state of the cell and therefore, may not represent its real structure. This is even more critical with membrane proteins, like GPCRs, due to their highly hydrophobic framework and the need for detergents to extract proteins from membranes. Either working with aqueous solutions or with detergents, the composition and organization of the membrane is altered, which can be a source of false results. Nevertheless, besides the inherent technical problems associated with these methods they have been shown to give accurate results, and they are still very useful to confirm close interactions between GPCRs. During the last decade, a new set of technologies based on the use of fluorescent‐fused proteins have been developed to overcome the invasive nature of the immobilized protein–protein interaction assays. These new approaches, centered on the use of various adaptations of resonance energy transfer (RET) techniques (e.g., fluorescence‐RET and bioluminescence‐RET), have favored the possibility of carrying out “in vivo” real‐time experiments. Thus, the use of BRET and FRET techniques has emerged as powerful tools to study GPCR oligomerization. A2AR‐D2R heteromers [51, 52, 53, 54] may exist in the dorsal and ventral striato‐pallidal GABA pathway in which activation of A2AR reduce D2R recognition, coupling, and signaling together with A2AR and D2R homodimers (Fig. 1) [21, 23, 25, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55]. A large number of studies using the above mentioned approaches (e.g., coimmunoprecipitation, FRET and BRET), as well as biochemical binding and signaling, behavioral pharmacology, and microdialysis techniques, have corroborated the existence of A2AR‐D2R heteromers [24, 51, 52, 53, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61]. Interestingly, it has been also suggested that A2AR‐D2R heteromers may be predominantly located on the dendritic spines in the perisynaptic zones of DA terminals and glutamate synapses but also on glutamate terminals in the local circuits of the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons [24, 55, 57, 60, 62, 63].

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of A2AR and D2R homodimers and A2AR‐D2R heterodimer. The striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons might co‐express A2AR and D2R homo‐ and heterodimers (dashed box) at the plasma membrane. Adenosine and dopamine can potentially interact with both homo‐ and heterodimers converging in the control of adenylate cyclase function an integrated cellular response is generated. The functional balance between these three oligomers determines the final adenylate cyclase output and thus the eventual cellular response. The antagonistic allosteric A2AR–D2R interaction in the heterodimer (dashed box) is shown (filled black arrow) as well as the negative and positive coupling of D2R and A2AR to the adenylate cyclase, respectively.

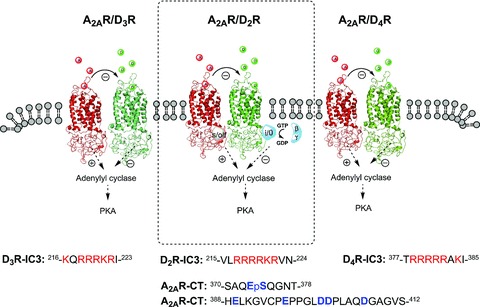

In the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neuron, this heteromer may exist in equilibrium on the neuronal surface membrane together with A2AR and D2R homomers. It seems possible that higher‐order A2A‐D2 RM of unknown stoichiometry and topology may also exist and contain, for examle, D2R homodimers and A2AR homodimers. In such a case, antagonistic A2AR–D2R interactions can still take place by assuming that the A2AR can enhance the negative cooperativity in such participating D2R homodimers. Such events may also take place in the A2AR‐D3R and A2AR‐D4R heteromers (see below). A major component of the interface in the A2AR‐D2R heteromer is the electrostatic interaction between the positively charged arginine‐rich epitope in the N‐terminal domain of the IC3 of the D2R and negatively charged epitopes in the C‐terminal tail of the A2AR, especially the epitope (aa 370–378) containing a phosphorylatable serine (Fig. 2) [52, 64]. Thus, phosphorylation events may modulate the strength of the receptor–receptor interactions within the A2AR‐D2R heteromer and RM. These results were also supported by studies using D1R‐D2R chimeras [65]. In addition, microdialysis experiments indicate that in awake, freely moving rats the A2AR agonist CGS 21680 when intrastriatally co‐perfused with the D2R‐D3R agonist quinpirole (10 μM), was able to fully counteract the quinpirole‐induced reduction of extracellular GABA levels in the globus pallidus, see [61], where CGS 21680 itself did not produce any significant effects on its own.

Figure 2.

Illustration of positively charged arginine‐rich epitopes 215VLRRRRKRVN224 (D2R), 216KQRRRKRI223 (D3R), and 377TRRRRRAK385 (D4R) in the N‐terminal part of the third intracellular loop of D2R, D3R, D4R, electrostatically interacting with negatively charged C‐terminal epitopes of the A2AR (370SAQEpSQGNT378, 388HELKGVCPEPPGLDDPLAQDGAGVS412). The most important residues in the A2AR appear to be the phosphorylated serine in the 370SAQEpSQGNT378 in the C‐terminal epitope of the A2AR [52, 55, 64]. These electrostatic interactions represent important hot spots in the receptor interface of the A2AR‐D2R, A2AR‐D3R and A2AR‐D4R heteromers. The prototype was the A2AR‐D2R heteromer (dashed box).

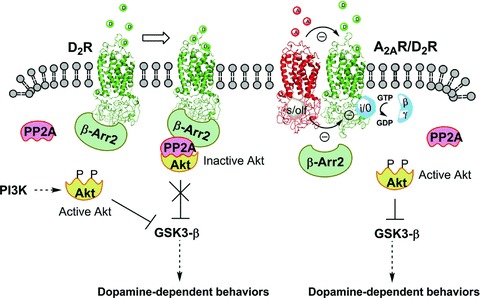

The antagonistic A2AR–D2R interaction in the brain has been demonstrated in many publications including at the level of D2R agonist recognition and animal behavior, see [23, 24, 55, 60, 63, 66, 67, 68, 69]. These results make it likely that the A2AR‐D2R heteromer strongly modulates the excitability in the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons via its ability to counteract D2R signaling to multiple effectors. The A2AR‐induced counteraction of the D2R‐induced inhibition of the Ca2+ influx over the l‐type voltage dependent Ca2+ channels (Cav 3.1 channels) via the activation of phospholipase C and protein phosphatase‐2B (calcineurin) [70] may be of special importance [15, 60]. The G protein involved may be Gi/o and/or Gq/11 with the release of the βγ subunits. The counteraction of this cascade by A2AR leads to increased phosphorylation of this calcium channel and its increased opening favoring an upstate of the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neuron, see [71]. A2AR activation also has been shown to counteract D2R‐induced intracellular calcium responses in cotransfected mouse fibroblast and human neuroblastoma cell lines [72, 73]. Moreover, the D2R agonist‐induced reduction of firing rates in the DA denervated striatum was enhanced by A2AR antagonists and attenuated by A2AR agonists [69]. The D2R in the A2AR‐D2R heteromers may also be coupled to Gi/o since in cultured striatal neurons A2AR agonists can counteract the D2R induced inhibition of forskolin stimulated cyclic AMP (cAMP) production without being active when given alone [15, 24, 53, 55, 60]. It is also likely that A2AR activation through inhibition of the Gi/o coupling of the D2R with the Gi/o trimer remaining at the D2R will also interfere with the protein kinase B (Akt)‐Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK‐3) signaling cascade induced by D2R stimulation through its ß‐arrestin 2 signaling [74]. Thus, ß ‐arrestin 2 can no longer become effectively linked to the D2R, since the Gi/o trimer is not sufficiently split and removed from the D2R in the presence of A2AR activation (Fig. 3). It should also be considered that the A2AR‐D2R receptor–receptor interaction also leads to a conformational state of the D2R less able to bind and activate the ß‐arrestin 2 as is the case for Gi/o.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of protein kinase B/glycogen synthase kinase 3 (Akt/GSK3) signalling networks regulated by dopamine D2R. (Left) The stimulation of D2R lead to an initial change in receptor conformation that mediate the activation of Gi/o protein, leading to inhibition of adenylyl cyclase, subsequently to receptor phosphorylation by G‐protein receptor kinase and the recruitment of β‐arrestin. The recruitment of β‐arrestin results in the formation of a signalling complex that comprises at least β‐arrestin, PP2A and Akt. The formation of this complex result in the deactivation of Akt by protein phosphatise 2A (PP2A) and the subsequent stimulation of GSK‐3 that mediates dopamine‐dependent behaviors. (Right) The antagonistic allosteric A2AR–D2R interaction in the heterodimer could reduce β‐arrestin recruitment, resulting in an enhancement of Akt phosphorylation, thus inhibiting GSK3 (see text).

There also exists a reciprocal interaction between A2AR‐D2R in as much as D2R can inhibit the A2AR‐induced increase in cAMP accumulation via Gi/o at the level of the adenylate cyclase (AC), an interaction which also can take place between A2A and D2 homomers, see [24, 55, 75]. Removal of the D2R brake on the A2AR signaling would therefore, also lead to increased striatal excitability since it will result in increased protein kinase A (PKA) activity causing increased phosphorylation of α‐amino‐3‐hydroxy‐5‐methyl‐4‐isoxazole‐propionate (AMPA) and N‐methyl‐d‐aspartic acid receptors (NMDA) and of dopamine and cAMP regulated neuronal phosphoprotein (DARPP‐32) at Thr34 position with inhibition of protein phosphatase‐1 further enhancing the phosphorylation and the activity of these ion channel receptors, see [60, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80]. Such events would also favor the up‐state of the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons. Based on the aforementioned, it seems likely that the A2AR‐D2R heteromer, via its antagonistic receptor–receptor interaction, plays a crucial role in moving the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons towards the up‐state by the antagonism of D2R signaling, see [15].

Relevance to Parkinson's Disease and its Treatment

Based on the antagonistic A2AR–D2R interaction described earlier, the development of A2AR antagonists to target these A2AR‐D2R heteromers in the dorsal striato‐pallidal GABA pathway was initiated [24, 59, 63, 81, 82]. It was also demonstrated that the antagonistic A2AR–D2R interaction remained and was even increased in the striatal membranes from rat models of Parkinson's disease (PD) [68, 81]. In a number of PD models, A2AR antagonists, like SCH 58261, have been found to dose‐dependently increase locomotor activity in combination with sub‐threshold doses of l‐DOPA and D2R agonists in reserpinized mice. In fact, A2AR antagonists consistently reverse Parkinsonian deficits in non‐human primates and rodents; see [60, 61, 68, 81]. It should be noted that in contrast to caffeine [83], subchronic A2AR antagonist treatment in models of Parkinson's disease does not result in tolerance development [84, 85], which represents a prerequisite for clinical development. Therefore, similar antiparkinsonian effects may be seen with acute and chronic treatment of A2AR antagonists.

Such results could elegantly be explained by the hypothesis that A2AR antagonists target the A2AR‐D2R heteromer and increase D2R signaling in these heteromers. These A2AR‐D2R heteromers have been found to be constitutive [51] and thus exist in the absence of agonist activation of the receptors. Therefore, it is not likely that A2AR antagonist treatment will disrupt the A2AR‐D2R heteromers but conformational changes may develop in the heteromer thereby altering its integrative activity. So far it has not been possible to see differences in the affinity and blocking activity of A2AR antagonists at A2AR belonging to A2AR‐D2R heteromers or to A2AR homomers (unpublished data). The A2AR antagonist istradefylline (KW‐6002) has been used in clinical trials and found to have interesting anti‐Parkinsonian and anti‐dyskinetic properties [60, 68, 78, 86]. Initial clinical studies using KW‐6002 showed symptomatic but rather modest improvement in relatively advanced PD patients with dyskinetic complications [87, 88]. However, bradykinesia, muscle rigidity and resting tremor in PD patients may be improved after A2AR blockade.

Based on our hypothesis, treatment with an A2AR antagonist alone should in fact produce only modest effects in PD except during early stages of PD when DA is still being released from remaining DA terminals. Instead the A2AR antagonist should ideally be given in Parkinsonian patients in combination with close to threshold doses of l‐DOPA and/or D2R agonist. Clinical results observed so far would be in agreement with this view. Thus, the A2AR antagonist would be targeting the A2AR‐D2R heteromer to enhance D2R signaling.

A2AR antagonists, by acting on the A2AR‐D2R heteromer will enhance D2R signaling at the soma‐dendritic level and lead to a reduction in the activity of the striato‐pallidal GABA/enkephalin pathway. In this way, motor inhibition will be reduced and the motor drive will be partly restored. A combined treatment with l‐DOPA will still be optimal since it will restore D1R activity in the direct pathway that helps motor initiation. The direct pathway becomes integrated with the indirect pathway in the globus pallidus interna and zona reticulata of the substantia nigra to optimally inhibit their GABA projections to the motor thalamus. In this way, the GABA inhibition of the excitatory glutamate thalamo‐cortical pathway to the motor cortices will be removed and movements restored

To understand the role of A2AR antagonists in PD it becomes important to note that there also exists a reciprocal interaction by which D2R inhibits the A2AR signaling at the level of AC as discussed earlier, either in the A2AR‐D2R heteromer or between A2AR homomers and D2R homomers (see earlier). In this way, we can understand why A2AR antagonists alone can counteract haloperidol‐induced catalepsy: namely, by blocking the excessive A2AR signaling that results from the removal of D2R‐induced inhibition of AC by haloperidol. This mechanism can also help to explain some therapeutic effects of A2AR antagonists in advanced PD, see [60].

When discussing the role of A2AR and D2R we should also consider the balance between A2AR homomers versus D2R homomers and A2AR‐D2R heteromers (Fig. 1). l‐DOPA treatment may lead to a disruption of the balance between them that ultimately leads to increases in A2AR signaling versus D2R signaling. This would help to explain the reduction of the therapeutic effects of l‐DOPA and the appearance of l‐DOPA‐induced dyskinesias after prolonged treatment. Our hypothesis is that a l‐DOPA‐induced co‐internalization of A2AR‐D2R heteromers and D2R homomers leads to a compensatory up‐regulation of A2AR and an increase in A2AR homomers. To support this hypothesis, increases of A2AR mRNA and A2AR immunoreactivity (IR) have also been demonstrated in both animal models of l‐DOPA‐induced dyskinesias and in dyskinetic PD patients, see [89]. The resulting up‐regulation of A2AR leads to increases in PKA and phosphorylated DARPP‐32 at Thr34 and increased inhibition of PP‐1. This will result in an increase in protein phosphorylation including ion channels, which may help stabilize pathological RM formed under the influence of the transcriptional panorama caused by the l‐DOPA‐induced excessive D2R activation [52, 64]. This may lead to a repeated appearance of the abnormal pattern of firing in the striato‐pallidal GABA pathway and contribute to dyskinesias. This hypothesis can help explain the reported anti‐dyskinetic effect of A2AR antagonists, which cannot be explained by the enhancement of D2R signaling in the heteromer since this would worsen dyskinesias. We have also postulated, based on this hypothesis, that A2AR antagonists will help to counteract the disappearance of the therapeutic effects of l‐DOPA after long‐term treatment, see [60, 68].

Taken together, the demonstrated anti‐Parkinsonian effect of A2AR antagonists in clinical studies has given “proof of concept” that intramembrane receptor–receptor interactions in receptor heteromers can lead to the development of novel therapies. The A2AR in the A2AR‐D2R heteromer in the dorsal striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons is the major target for A2AR antagonists when used in treatment of PD.

A2AR antagonists may have not only anti‐Parkinsonian properties but also neuroprotective and anti‐dyskinetic properties. Recently it has been found that inactivation of forebrain A2AR fully counteracts nigral DA nerve cell degeneration in mouse model of Parkinson's disease associated with a block also of nigral gliosis [90]. In line with these results, an attenuation of the DA nerve cell degeneration and of the gliosis was observed after treatment with the A2AR antagonist SCH58261 [90]. However, the molecular mechanism for its neuroprotective effect on DA cells, as found by Schwartzschild et al., see [60, 68], is still unclear, although an increase in retrograde trophic signaling from the striatum has been proposed by Fuxe et al. [60].

When discussing the potential neuroprotective effects of A2AR antagonists in Parkinson's disease the epidemiological evidence should also be considered. There exists an inverse association between intake of coffee and caffeine in Japanese–American men and the risk of development of Parkinson's disease [91]. These results were strengthened by a study in a larger and more ethnically diverse cohort of prospectively followed men showing again an inverse relationship between consumption of caffeinated but not decaffeinated coffee and the risk of development of Parkinson's disease [92]. This link between consumption of caffeine in coffee and lower incidence of Parkinson's disease strongly favor the view that A2AR antagonists may have neuroprotective actions in Parkinson's disease. Thus, it is generally believed that caffeine exerts its psychoactive actions through blockade of A1R and A2AR in the CNS [20, 83]. Overall, A2AR antagonists therefore clearly offer a realistic opportunity to improve PD treatment.

Relevance to Schizophrenia and its Treatment

The indicated existence of A2AR‐D2R heteromers with antagonistic A2AR–D2R interactions in the ventral striato‐pallidal GABA pathway has also introduced the strategy of using A2AR agonists for the treatment of schizophrenia. In this way, based on these antagonistic interactions, A2AR agonist treatment would lead to a reduction in the high affinity state of the D2R and a reduction of its Gi/o coupling [24, 25, 55, 93]. It is also known that the common feature of antischizophrenic drugs of the D2R antagonist type is the antagonism of the D2R‐ß‐arrestin 2 interaction and thus of Akt‐GSK‐3 signaling [94, 95]. As discussed, the observations suggest that A2AR agonists may also interfere with the D2R‐ß‐arrestin 2 interaction (Fig. 3). Also it has been shown that the A2AR agonist CGS‐21680 reduces protein phosphatase 2A activity in the murine heart [96] which increases Akt activation and thereby blocks the GSK‐3 signaling (Fig. 3).

The classical treatment in schizophrenia is the use of DA receptor antagonists such as haloperidol (a typical antipsychotic) to block the D2R on both nigro‐striatal and mesolimbic DA neurons [5, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101]. This leads to motor and mental effects through the blockade of excessive D2R‐mediated DA transmission in the nigro‐striatal and meso‐limbic DA systems, respectively; see [25, 55, 93]. Atypical antipsychotic drugs, like benzamides, that display reduced motor side effects may at least in the case of remoxipride block only subpopulations of D2R [102]. The reason for this may be that remoxipride‐sensitive D2R receptors are part of a particular receptor heteromer [15, 17, 24, 45] that provide a unique pharmacology to these D2R and make them remoxipride‐sensitive. According to the Seeman hypothesis of schizophrenia [101], the major error in psychosis is an increased proportion of D2R in the high affinity state that results in the development of D2R supersensitivity. This makes our proposal on the antipsychotic potential of A2AR agonists of special interest since they can, via the A2AR‐D2R heteromer, preferentially reduce the high affinity agonist state of the D2R in both the dorsal and ventral striatum.

However, the current combined glutamate/DA hypothesis of schizophrenia states that the meso‐limbic DA neurons are hyperactive due to reduced NMDA receptor function of cortical glutamate systems. This results in the reduced activity of the descending cortical glutamate projections to the ventral tegmental area (VTA) giving rise to the meso‐cortical and meso‐limbic DA systems. In this way, the VTA GABA interneurons that inhibit the firing of the meso‐limbic DA neurons have reduced activity and as a consequence the meso‐limbic DA neurons become hyperactive and inhibition of the ventral striato‐pallidal GABA pathway becomes increased [15, 45, 103]. The ventral striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons integrate and transfer the emotional information from the limbic system via the medial dorsal (MD) nucleus to the prefrontal cortex (PFC) [15]. The increased activity of these D2R reduces the glutamate drive to the prefrontal cortex and further worsens the hypoglutamatergic state in schizophrenia. As it was postulated early on [104], DA receptors in meso‐limbic DA transmission are a major target for antipsychotic drugs that improve the emotional state of the schizophrenic patients.

We have proposed that the A2AR agonists may be used as anti‐schizophrenic drugs through their antagonism of D2R signaling in the A2AR‐D2R heteromer in the soma‐dendritic region of the ventral striato‐pallidal GABA pathway. This would help to reestablish the glutamate drive from the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus to the prefrontal cortex [15]. In fact, A2AR agonists strongly reduce the D2R agonist binding affinity in the nucleus accumbens shell and core [105] diminishing both D2R recognition and G protein coupling. The A2AR‐D2R heteromer also exists on the glutamate terminals of the local circuits in the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons and counteracts D2R‐induced inhibition of glutamate release upon A2AR activation. This increase in glutamate release after A2AR agonist treatment will also contribute to enhance the excitability of the ventral striato‐pallidal GABA pathway and thereby add to the antipsychotic activity of A2AR agonists. It is important to note that D2 autoreceptors are not directly modulated by A2AR agonists because A2AR does not exist in the DA terminal networks. In this way, A2AR agonist treatment will not affect the function of the D2 autoreceptor to further contribute in lowering DA release.

The anti‐schizophrenic potential of A2AR agonists is further underlined through behavioral analysis in the amphetamine and phencyclidine rat models of schizophrenia [106] and in the Cebus apella monkey model of schizophrenia [107] in which it demonstrated an atypical antipsychotic profile. Therefore, A2AR agonist treatment represents a new strategy for the treatment of schizophrenia, especially in combination with very low doses of atypical and/or typical D2R antagonists, to further reduce the development of extrapyramidal side effects, see [15, 45].

Disturbances in the A2AR molecular mechanisms especially in the A2AR‐D2R receptor heteromer in schizophrenia should be considered since deficits in the operation of the antagonistic A2AR–D2R interaction may increase the vulnerability to develop the disease [15]. However, it should be noted that treatment with A2AR antagonists in PD has so far not led to an increase in psychotic episodes in PD patients, see [68], possibly due to a low adenosine and in particular DA tone in the nucleus accumbens and other parts of the ventral striatum in the PD patients on A2AR antagonist monotherapy.

Dual‐probe microdialysis evidence from the Tanganelli group (Ferraro et al., unpublished data (see [15]), in awake, freely moving rats supports the A2AR agonist treatment strategy in schizophrenia. It was demonstrated that the D2R‐D3R agonist quinpirole (10 μM) when superfused in nucleus accumbens was able to reduce accumbal extracellular GABA levels while increased extracellular GABA levels in the MD nucleus, medial division. The actions of the D2R agonist were counteracted by the A2AR agonist CGS 21680 (1 μM) when co‐superfused with quinpirole into the nucleus accumbens. These results provide for the first time the functional evidence for a connection between the ventral striato‐pallidal GABA pathway with the MD medial division which is known to innervate the prefrontal cortex via widespread glutamate projections via the ventral pallidal‐MD GABA pathway, see [108].

Furthermore, in agreement, Ferraro et al. (unpublished data) found using dual probe microdialysis that extracellular levels of glutamate in the prefrontal cortex were reduced after accumbal superfusion with quinpirole (10 μM), see [15]. The A2AR agonist CGS 21680 (1 μM) when co‐superfused with the D2R agonist in the nucleus accumbens not only counteracted the D2R agonist induced reduction of prefrontal glutamate levels, but even resulted in a small rise of extracellular levels of glutamate in the prefrontal region. These results give functional neurochemical evidence that A2A‐D2 receptor–receptor interactions in the nucleus accumbens have substantial relevance for the activity of the MD glutamate projections to the prefrontal cortex and schizophrenia in view of hypoglutamatergia and hypofunction in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of schizophrenic patients, see [109].

Within the nucleus accumbens, quinpirole, upon local superfusion, reduced the extracellular levels of accumbal glutamate probably via inhibition of glutamate release from cortico‐striatal glutamate terminals known to possess D2R. These glutamate terminals may also possess A2AR that interact with D2R and are known to release glutamate [110]. In agreement, the A2AR agonist CGS 21680 superfused into the nucleus accumbens in the present experiments produced a substantial and prolonged release of glutamate (Ferraro et al., unpublished data); see [15]. Interestingly when CGS 21680, at a concentration by itself ineffective on cortical extracellular glutamate levels, was co‐perfused in the nucleus accumbens with quinpirole, it significantly antagonized the reduction of extracellular glutamate levels induced by quinpirole in the prefrontal cortex (Ferraro et al., unpublished data), see [15].

Taken together, these results give evidence of the importance of antagonistic A2AR–D2R interactions in both the ventral striato‐pallidal GABA pathway and in the cortico‐striatal glutamate terminals in the control of the prefrontal glutamate projections via the ventral pallidum and MD, a loop with major disturbances in schizophrenia. Jones et al. [109] have demonstrated that there exists a subnucleus specific loss of nerve cells in the medial thalamus of schizophrenics. Through stereological counts, a 30% loss of nerve cells was demonstrated in the MD nucleus primarily confined to the parvocellular and densocellular subnuclei. It is of substantial interest that the parvocellular part projects to the dorsolateral parts of the prefrontal cortex and other regions known to be compromised in schizophrenia, see [109]. These results underline the relevance of the present strategy of targeting the A2AR‐D2R heteromer in the nucleus accumbens by A2AR agonist treatment alone or in combination with low doses of D2R antagonists to help restore the glutamate drive from MD to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

Relevance to Cocaine Addiction and its Treatment

An increase in A2AR in the nucleus accumbens has been observed after extended cocaine self‐administration, see [111]. Following a 10‐day cocaine self‐administration procedure, one that increased accumbal D1R, D2R and D3R signaling through a cocaine‐induced increase in extracellular DA levels via its well‐known blockade of the DA transporter, gave rise to a compensatory up‐regulation of A2AR that diminished during a cocaine withdrawal period. Behavioral pharmacological results have demonstrated that A2AR antagonists reinstate cocaine self‐administration [112] and that A2AR agonists diminish the reinforcing effects of cocaine [113]. Furthermore, A2AR agonists counteract the development and expression of sensitization to the locomotor activation effects of cocaine [114]. In fact, antagonistic A2AR–D2R interactions have been demonstrated in the nucleus accumbens at both the binding and behavioral level and at the level of neuronal function [24, 55, 60, 93, 105].

A direct action of cocaine on the A2AR is not involved in producing this probable rise of accumbal A2AR signaling in the animals with cocaine still present in the brain [111]. The disappearance of the A2AR rise during the withdrawal period may help to explain the increased reinforcing efficacy of cocaine in animals after 7 days of cocaine withdrawal [115]. This could involve a compensatory mechanism to increase signaling via accumbal D2R and D3R by reducing the A2AR brake on D2R and D3R signaling [111]. The results indicate a putative role of antagonistic A2AR–D2R interactions at the membrane (in A2AR‐D2R heteromers) and cytoplasmatic level in the nucleus accumbens in the prevention of development of cocaine addiction. These results open up the possibility that A2AR agonists can represent cocaine antagonists to be used in the prevention of cocaine addiction. This is not supported by the fact that the lack of A2AR signaling reduces the reinforcing efficacy of cocaine [116] in A2AR knockout mice but may be explained by a reorganization of the D2R containing RM in these transgenic mice.

The observed rise of A2AR in the nucleus accumbens after extended cocaine self‐administration may depend on the existence of an atypical cAMP response element (CRE) in the core promoter of the A2AR gene [117]. CREB (CRE binding protein) diminishes cocaine reward in this region [118] and is enabled by increased activation of the extracellular signal‐related kinase [119]. A2AR and D2R are collocated in the ventral striato‐pallidal GABAergic pathway [120, 121, 122] and cocaine‐induced activation of the D2R can produce an increase in CREB phosphorylation via several intracellular mechanisms, see [15, 60, 111].

It should also be considered that the A2AR up‐regulation reflects not only increases in, for example, A2AR‐D2R heteromers but also increased formation of A2AR homomers that further increase the excitability of the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons [24, 55, 60, 89] by counteracting D2R‐mediated inhibition of these neurons. Another mechanism could be that persistent D2‐like receptor activation sensitizes A2AR signaling at the level of the AC via the release of βγ dimers from the activated Gi proteins [24, 55, 60, 89, 123, 124, 125]. It is of interest that the increased density of A2AR in the nucleus accumbens after cocaine self‐administration demonstrated a reduced affinity of the A2AR antagonist binding sites. This may, inter alia, reflect the formation of novel A2A/D2‐like RM with a different stoichiometry and/or topology that produces conformational changes in the receptors of this RM, which lead to altered allosteric interactions and changes in the affinity of the A2AR.

A2AR‐D3R and A2AR‐D4R Heteromers

Biochemical and Functional Findings

A study by Torvinen et al. [126] demonstrated a specific and high FRET efficiency in cells transiently co‐transfected with A2AR‐YFP and D3R‐GFP2 receptors providing evidence that A2AR and D3R receptors form an A2AR‐D3R heteromer (Fig. 2). Also similar to the D2R, the D3R contains the arginine‐rich epitope in its IC3 that makes possible an electrostatic interaction with the carboxyl terminus of the A2AR [55]. Evidence was also obtained in membranes prepared from stably transfected CHO cell lines, in which A2AR activation reduces D3R agonist binding and D3R signaling. This provided the evidence for an antagonistic A2AR–D3R interaction in A2AR‐D3R heteromers similar to the antagonistic interaction observed in the A2AR‐D2R heteromer. A2AR‐D3R heteromers may therefore exist in the nucleus accumbens where the A2AR and D3R are co‐distributed provided that they are co‐expressed in the same neuron. In view of the existence of D3R dimers and tetramers in brain [127] the existence of higher order A2AR‐D3R heteromers (A2A‐D3 RM) should be considered.

The existence of A2AR‐D4R heteromers has also been postulated based on the existence of the arginine‐rich epitope in the IC3 loop of the D4R, which can interact with the negatively charged epitopes in the A2AR carboxyl terminus (Fig. 2) [55]. Recently, it has also been possible to demonstrate the existence of A2AR‐D4R heteromers through BRET experiments in transiently co‐transfected A2AR‐D4R in cell lines (Borroto‐Escuela et al. unpublished data). The A2AR and D4R may be codistributed especially in the island (striosome, patch) striato‐nigral GABAergic system at the soma‐dendritic level [128], where it is postulated that A2AR‐D4R heteromers may exist. The striatal island system is involved in cognitive, reward and motivational functions, see [129, 130], which may be modulated by the postulated A2AR‐D4R heteromers.

Relevance to CNS Diseases and their Treatments

The D3R is being considered a target for novel anti‐schizophrenic drugs that display a D3R antagonist profile [131, 132]. Therefore, A2A‐D3 RM offer possibilities for novel treatment strategies of this disease that might include the combined use of novel D3R antagonists and A2AR agonists in order to reduce D3R signaling.

Indirect indications have been obtained for a rise in D3R density in the nucleus accumbens in cocaine self‐administering animals after experiencing cocaine withdrawal [111], which are in line with previous results that demonstrated increases in D3R binding after cocaine withdrawal that was also associated with an increase in cocaine‐seeking behavior [133, 134]. D3R antagonists counteract cocaine seeking and cocaine enhanced reward and may be used in treatment of cocaine addiction [131, 135, 136]. Furthermore, an up‐regulation of D3R mRNA levels was found in reward networks of human cocaine fatalities [137]. Therefore, the reduction not only of the antagonistic A2AR–D2R interaction but also of the antagonistic A2AR–D3R interaction in animals after 7 days of cocaine withdrawal [111] may contribute to the increased motivation to self‐administer cocaine [115]. The A2AR may also have a role in cocaine addiction through its potential modulation of D4R in the island striato‐nigral DA system in view of the demonstration of A2AR‐D4R heteromers in cotransfected cell lines (Borroto‐Escuela et al., unpublished data).

A2AR‐D2R Containing Receptor Mosaics

A2A‐D2R‐mGlu5 Receptor Mosaic

Biochemical and Functional Findings

The existence of functional A2AR‐D2R‐mGlu5R oligomers in the GABAergic striato‐pallidal neuron has often been discussed based on the high and selective co‐expression of mGlu5R, D2R and A2AR in these particular cells, on the demonstration of A2AR‐D2R heteromers (see earlier) and A2AR‐mGlu5R [138] heteromers and on the existence of strong multiple interactions between the three receptors [15]. The existence of neurotransmitter receptor heteromers in general and A2AR‐D2R heteromers in particular is now broadly accepted and reinforced by the fact that the functional meaning of heteromerization is being revealed. Thus, the heteromerization of neurotransmitter receptors and their existence as RM have been demonstrated in neuronal cells as functional entities that possess different biochemical characteristics with respect to the individual components of the RM. Therefore, the heteromer might be considered as a molecular switch that fine‐tunes the information flow between neurons, thus the signaling mediated by a single stimulated receptor within the heteromer might be, from a qualitative and/or quantitative point of view, different to that expected when all the receptors are simultaneously stimulated. Interestingly, the existence of RM or higher‐order receptor heteromers has been recently demonstrated [139, 140].

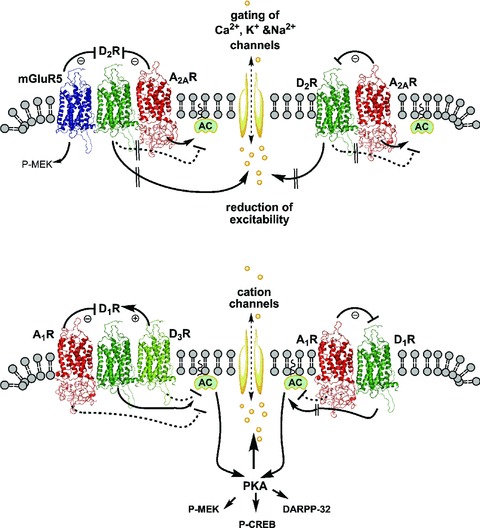

Taking advantage of the recent fluorescence‐based approaches to study protein–protein interactions, we have recently demonstrated the existence of higher‐order A2AR‐D2R‐mGlu5R oligomers or RM (Fig. 4). Initially, by using bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC), we visualized for the first time the occurrence of mGlu5R‐D2R heterodimers in living cells [139]. Furthermore, the combination of BiFC and BRET techniques allowed us to detect the existence of receptor oligomers containing more than two protomers, namely A2AR‐D2R‐mGlu5R higher‐order oligomers or RM (Fig. 4) [139]. Thus, this new experimental approach has allowed the study of the quaternary structure of A2A‐D2‐mGlu5 RMs.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of putative A2A‐D2‐mGlu5 RM and A2AR‐D2R heterodimer in the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons (A) and A1‐D1‐D3 RM and A1R‐D1R heterodimer in the striato‐entopeduncular/nigral GABAergic neurons (B). In panel A, the antagonistic A2AR‐D2R and mGlu5R–D2R interactions in the A2A‐D2‐mGlu5 RM are shown as well as the antagonistic A2AR–D2R interactions in the heterodimer. The interactions at the level of adenylate cyclase are also indicated in which D2R inhibits and A2AR activates this enzyme. D2R signalling from the putative RM and/or the heterodimer control the excitability of the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons by gating ion channels. In panel B, the antagonistic A1R‐D1R and facilitatory D1R–D3R interactions in the putative A1‐D1‐D3 RM are shown as well as antagonistic A1R–D1R interactions in the heterodimer. The interactions at the level of adenylate cyclase are also indicated in which D1R activates and A1R and possibly D3R inhibits this enzyme. The activation of PKA contributes not only to activate intracellular pathways that lead to the phosphorylation of DARPP‐32, MEK, and CREB, but also to phosphorylation events that lead to an increase in the activity of cation channels.

Interestingly, by using triple‐labeling post‐embedding immunogold and detection at the electron microscopic level, the precise simultaneous distribution of A2AR, D2R and mGlu5R in striatal neurons has been performed. It is noticeable that these three receptors co‐distributed in post‐synaptic structures along the extra‐synaptic and peri‐synaptic plasma membrane of spines that establish asymmetrical, putative glutamatergic, synapses with axon terminals [139]. Overall, this is the first direct anatomic evidence for mGlu5R, D2R and A2AR co‐distribution in the same neuronal compartment and supports the notion of that these receptors form a RM in GABAergic striatopallidal neurons.

Relevance to CNS Diseases and Treatments

The A2A‐D2‐mGlu5 RM may mainly be in operation to produce activation of the cortico‐striatal glutamate synapse and the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons when motor inhibition of certain movements is required [15]. The increased firing in the glutamate terminals will release glutamate and co‐stored ATP that will result in an increased formation of adenosine and lead to the increased activation of both pre‐ and postjunctional A2AR and mGlu5R receptors that synergize to counteract the D2R signaling in the glutamate terminals and in the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons. In this way, the firing of the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons can develop without being restrained by the D2R signaling that is aimed to silence the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons. Once the firing in the cortico‐striatal glutamate pathways slows down, the balance between glutamate and DA signaling; in the RM will reach another set‐point dependent on the movements to be initiated.

Parkinson's disease. The development of mGlu5R antagonists is yet another strategy for treatment of PD based on their ability to enhance D2R recognition and signaling in these RM in the dorsal striato‐pallidal GABAergic pathway by the removal of the antagonistic mGlu5R–D2R interaction. In addition, mGlu5R antagonists block the ability of mGlu5R to enhance NMDA receptor signaling, which will also favor anti‐Parkinsonian actions by reducing the excitability of the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons and thus their ability to cause motor inhibition, see [141].

It should be noted that the ability of mGlu5R antagonists to produce motor activation requires both A2AR and D2R, which underlines their interdependence and supports the concept of A2AR‐D2R‐mGlu5R RM [142]. The synergism of A2AR and mGlu5R antagonists to increase locomotion in reserpinized mice [142, 143] can be elegantly explained by the existence of A2A‐D2‐mGlu5 RM where A2AR‐mGlu5R synergize to counteract D2R signaling, see [68].

The postulated A2A‐D2‐mGlu5 RM in the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons with multiple receptor–receptor interactions is therefore, a novel target for anti‐Parkinsonian drugs. The aforementioned results have led to the proposal that mGlu5R antagonists especially in combination with A2AR antagonists or drugs with both A2AR and mGlu5R antagonist properties are symptomatic anti‐Parkinsonian drugs of special value particularly in view of their neuroprotective properties, see also [15, 60].

Schizophrenia. The postulated A2A‐D2‐mGlu5 RM may also exist in the ventral striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons and in the glutamate terminal networks of the ventral striatum. In fact, A2AR and mGlu5R agonists synergize when co‐superfused into the nucleus accumbens to increase GABA release in the ventral pallidum [144]. Evidence for a role of mGlu5R in schizophrenia‐related behavior in rodents such as prepulse inhibition has also been obtained [145]. Therefore, combined treatment with A2AR and mGlu5R agonist drugs or drugs with combined A2AR and mGlu5R agonist properties may be an effective novel strategy for treatment of schizophrenia based on the synergistic A2AR–mGlu5R interaction which should be able to override the pathologically increased D2R signaling in this RM that may potentially be present in schizophrenia. The addition of a low dose of a D2R antagonist to the A2AR‐mGlu5R agonist treatment should also be considered.

A2A‐CB1‐D2 Receptor mosaic

Biochemical and Functional Findings

In previous work [146, 147] indications were obtained for the existence of cannabinoid‐dopamine CB1R‐D2R heteromers in co‐transfected HEK‐293 cells based on FRET analysis and for an antagonistic CB1R–D2R interaction based on D2R binding analysis. In 2005, studies using co‐immunoprecipitation in HEK‐293 cells gave further indications for CB1R‐D2R heteromers with an enhanced formation after concurrent activation of the two receptors. It was noticed that in this heteromer CB1R signaling, in part, switches from the inhibition of the AC to a pertussis toxin‐insensitive activation of AC [148], see also [149].

Colocalization of D2R and CB1R in striatum was first observed in 2002–2003 [150, 151] and have been later found particularly in cortico‐striatal glutamate terminals, in the soma and dendrites of ventral striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons and in local collaterals of the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons, see [152, 153]. Therefore, a chemical anatomical basis for CB1R–D2R interactions exists and results indicate that endocannabinoids, via inhibitory feedback, can counteract D2R‐mediated responses [154, 155, 156]. Recently, novel evidence has been obtained for the existence of CB1R‐D2R heteromers based on FRET analysis in HEK‐293 cells [157]. Thus, FRET data show a strong and specific FRET signaling in cells co‐transfected with cDNA of vectors encoding for D2R‐GFP2 and CB1R‐YFP but not in various controls including mixtures of cells expressing D2R‐GFP2 or CB1R‐YFP or co‐transfections with GFP2 or YFP without being tagged to the corresponding receptor. Of substantial interest is the finding of antagonistic D2R binding modulation by CB1R agonists that reduce D2R agonist affinity in striatal membranes. Similar results were also observed in the nucleus accumbens shell demonstrated by quantitative receptor autoradiography [157]. In agreement, behavioral analysis revealed that CB1R agonists can counteract D2R agonist‐induced hyperlocomotion, an effect that was blocked by rimonabant, a CB1R antagonist, which also can enhance the action of the D2‐like receptor agonist quinpirole [157]. These results clearly suggest that antagonistic intramembrane CB1R–D2R interactions exist in CB1R‐D2R heteromers in the ventral and dorsal striatum and lead to reduced D2R signaling, increased excitation and firing of the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons and counteraction of D2R‐induced hyperlocomotion.

Of special interest in this behavioral analysis was the observation that the A2AR antagonist, MSX‐3, could prevent the ability of the CB1R agonist CP 55,940 to counteract the D2R agonist‐induced hyperlocomotion [157]. These results indicated the involvement of A2AR that is also known to exist in the cortico‐striatal glutamate terminals and the soma‐dendritic regions of the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons in the antagonistic intramembrane CB1R–D2R interaction (see earlier). In line with these results, A2AR‐CB1R heteromers were also demonstrated in transiently transfected HEK‐293 cells and in neuroblastoma cells in which CB1R signaling was entirely dependent upon A2AR activation [158]. Finally, it was also shown that motor depression caused by CB1R agonists was blocked by A2AR antagonists. From the accumulating evidence, the existence of A2A‐CB1‐D2 RM was therefore postulated [157].

The sequential BRET‐FRET (SRET) technique was developed specifically for the identification of trimeric receptor mosaics [140]. Through a combination of BRET and FRET, trimeric receptor mosaics could finally be identified. This method was the essential technique to finally identify receptor mosaics, [15, 16, 17, 35, 43, 157]. Using the SRET technique, the A2A‐CB1‐D2 RM was the first RM to be identified in living cells, and this discovery is in line with the indications for its existence obtained in previous work on the brain, see [157]. This RM is an integrator of DA, adenosine and endocannabinoid signals.

The present hypothesis for the operation of this putative A2A‐CB1‐D2 RM in the brain states that the antagonistic CB1R–D2R interaction activated by the D2R‐induced release of endocannabinoids into the extracellular fluid removes the D2R brake on A2AR signaling to AC, see [15], by an inhibitory feedback mechanism by the activation of CB1 receptors in putative A2A‐CB1‐D2 RM in the ventral striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons and in cortico‐striatal glutamate terminals. The increase in A2AR signaling in the ventral striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons will, via DARPP‐32 phosphorylation at Thr34, strongly contribute to the markedly increased activity in ventral striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons by the inhibition of protein phosphatase‐1, which will enhance the phosphorylation of ion channels and ion channel‐linked receptors. The simultaneous release of A2AR signaling in striatal glutamate terminals will increase glutamate release and therefore lead to an increase in the glutamate drive of the ventral and dorsal striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons. Such an operation of this RM may be the molecular basis for the observed blockade of the D2R agonist‐induced locomotor hyperactivity and contribute to CB1R agonist‐induced motor inhibition [157]. It seems likely that the former is mainly in operation as an inhibitory feedback mechanism to reduce an exaggerated and prolonged activation of D2R that will produce a prolonged silencing of the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons. The release of the D2R brake on A2AR‐induced activation of AC probably plays a major role in making this possible.

Relevance to CNS Diseases and their Treatments

Parkinson's disease. The results from Marcellino et al. [157] clearly suggest that CB1R antagonists may represent novel symptomatic anti‐Parkinsonian drugs by enhancing D2R signaling to uphold its brake on A2AR signaling at the level of AC in the putative A2A‐CB1‐D2 RMs. These molecular events may explain the enhancement of D2R agonist‐induced hyperlocomotion by the CB1R antagonist and its ability to counteract the CB1R agonist‐induced inhibition of D2R‐induced hyperlocomotion.

It also seems likely that low doses of CB1R and A2AR antagonists may synergize to enhance D2R‐mediated anti‐Parkinsonian actions in early Parkinson's disease where DA release remains to a substantial degree from the remaining DA nerve terminal networks. The A2AR antagonist will also act by interfering with the ability of A2AR to inhibit D2R signaling in the A2A‐D2‐mGlu5 RM as discussed earlier. In contrast, in late PD with a very low DA tone, it becomes necessary to add low threshold doses of l‐DOPA or D2R agonists to achieve substantial therapeutic activity from CB1R and A2AR antagonists. Through the possibility to use low doses of the two and/or three drugs, side effects such as dyskinesias may be effectively reduced.

In line with these results, CB1R antagonists can strongly enhance the stereotypies caused by combined treatment with D1R and D2R agonists [159]. Furthermore, increased CB1R binding and G protein‐coupling has been observed in the basal ganglia of patients with Parkinson's disease and in the MPTP marmoset model of Parkinson's disease [160]. These neurochemical effects are counteracted by l‐DOPA therapy suggesting that the CB1R changes observed, represent a CB1R receptor up‐regulation in response to reduced D2R signaling in PD that fails to elicit the release of endocannabinoids [161] and thus fails to activate the inhibitory feedback via the CB1R. Similar results have been observed by Strömberg et al. [162] after chronic haloperidol blockade of the D2R. This mechanism can also help explain the reduced expression of cannabinoid CB1R mRNA in the basal ganglia of postmortem brain of Parkinsonian patients [163] as a result of the dopaminergic treatment. The CB1R antagonists should therefore act, as postulated earlier, to counteract the D2R‐activated inhibitory feedback activation of the CB1R in the A2A‐CB1‐D2 RM with the aim to bring down D2R signaling. The enhancement of D2R signaling in this RM should be optimized by a combined treatment with CB1R and A2AR antagonists in order to block the two allosteric mechanisms of antagonizing the D2R in A2A‐CB1‐D2 RM.

Schizophrenia. Antagonistic CB1R–D2R interactions may also exist in postulated A2A‐CB1‐D2 RM in the ventral striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons and in the cortico‐accumbal glutamate terminals. The possibility is open that CB1R agonists may possess antipsychotic properties by their ability to reduce D2R signaling in this pathway and in the afferent glutamate terminals that will lead to a reduction of positive symptoms of schizophrenia. This is however, in apparent disagreement with the fact that Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is reported to exacerbate psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia, see [164]. However, these actions may be exerted at CB1R in other brain regions inter alia the cerebral cortex.

These novel observations may help explain the findings that the increased CSF levels of anandamide found in schizophrenic patients are inversely correlated with psychotic symptoms [165]. Thus, an over activity of D2R‐mediated DA transmission in the ventral striatum may lead to an increased formation of the endocannabinoid anandamide with an increased inhibitory feedback on the D2R signaling via the CB1R–D2R antagonistic interaction in the A2A‐D2‐CB1 RM on the glutamate terminals and in the ventral striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons. In this way, the excessive D2R‐mediated inhibition of the ventral striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons may be reduced by anandamide, which can act as an agonist in the postulated A2A‐CB1‐D2 RMs.The precipitation of psychotic periods by cannabis use may also be related to the reduction of anandamide signaling in the brain [165] that leads to a reduction in the antagonistic CB1R–D2R interaction.

Cocaine addiction. The present indications of antagonistic CB1R–D2R interactions in RM in the ventral striato‐pallidal GABAergic pathway may help explain the ability of the CB1R agonist WIN 55,512‐2 to counteract the rewarding actions of cocaine in intracranial self‐stimulation experiments [166]. Thus, D2R participate in mediating cocaine reward by inhibiting the activity in this reward‐regulating pathway, see [111]. In line with this hypothesis, the CB1R agonist WIN 55,212‐2 can also reduce cocaine self‐administration [167]. Our interpretation is that the CB1R agonist, via the antagonistic CB1R–D2R interaction, leads to an increased activity in the ventral striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons thereby reducing the reward value of cocaine. As stated earlier, A2AR agonists can also reduce cocaine self‐administration. Therefore, we postulate that combined treatment with A2AR agonists and CB1R agonists that preferentially activates the A2AR and CB1R in A2A‐CB1‐D2 RM should represent an interesting and novel strategy for preventing the development of cocaine abuse.

A1R‐D1R Heteromers and A1R‐D1R Containing Receptor Mosaics

A1R‐D1R Heteromers

Biochemical and Functional Findings

A1R and D1R were shown to co‐immunoprecipitate in co‐transfected Ltk‐ fibroblast cells [168], a phenomenon that appeared specific, since co‐immunoprecipitation was not detected in A1R‐D2R co‐transfected Ltk‐fibroblast cells. The A1R‐D1R co‐immunoprecipitation was observed in the absence of A1R or D1R receptor agonist exposure, thereby indicating their constitutive formation. However, the A1R‐D1R co‐immunoprecipitation was substantially reduced after a 1 h treatment with the D1R agonist SKF 38393, giving evidence that D1R activation leads to disruption of the A1R‐D1R heteromeric receptor complex. This disruption did not occur if combined treatment with SKF 38393 and the A1R agonist R‐PIA was applied. Thus, these initial results indicated that A1R and D1R form receptor heteromers at least in cell lines. Later, co‐immunoprecipitation experiments indicated that they may also exist in striatum [169]. Further evidence that an A1R‐D1R heteromer exists was recently obtained, since specific BRET and FRET signals can be detected between fluorophore‐tagged A1R and D1R upon transient co‐transfection in cell lines [170]. The A1R‐D1R heteromer may exist on the cell surface membrane together with A1R homodimers [171] and D1R homodimers [172], and it is not known if the A1R‐D1R heteromer is preferred.

Competition experiments with the D1R antagonist [3H]‐SCH 23390 versus dopamine were performed in striatal membrane preparations as well as in membrane preparations from an A1R‐D1R co‐transfected Ltk‐ cell line [173, 174]. The A1R agonist CPA, in the nanomolar range, caused a marked reduction in the proportion of D1R in its high affinity state. These effects were mimicked by the GTP analogue Gpp (NH)p (100 μM). These results make it likely that A1R activation in the A1R‐D1R heteromer leads to an uncoupling of the D1R to its Gs/olf protein.

The possible role of the Gi protein in the A1R–D1R interaction at the binding pocket level was studied using pertussis toxin, since it inactivates the Gi protein coupled to the A1R. It was found that pertussis toxin treatment blocked the effects of low but not high concentrations of the A1R agonist on D1R binding characteristics [174]. However, it could not be determined if the D1R modulation by the high 10 μM concentration of CPA was due to activation of the low affinity A1R receptors or to the activation of the remaining high affinity A1R, since pertussis toxin‐induced ribosylation of the Gi protein was not complete.

This problem could however be solved by involving adenosine deaminase (ADA) in the analysis, which metabolizes adenosine to inosine. This enzyme binds to A1R as an ectoenzyme [175] and is necessary to obtain the high affinity binding state of A1R [176]. An irreversible inhibitor of ADA, deoxycoformycin (DCF), was found to fully counteract the effects of high and low concentrations of CPA on the binding characteristics of the D1R. The blockade of the enzymatic activity of ADA was shown not to be involved in this action of DCF. These results give evidence that it is the high affinity state of A1R that is responsible for the interaction with D1R, at least at the level of the binding pocket [177]. Thus, ADA may directly bind to the A1R, which is necessary for the A1R high affinity state to develop. This state has a protein conformation such that the A1R antagonistically interacts with the D1R. It follows that functional A1R‐D1R heteromer requires ADA to be bound to A1R, underlining the important role of receptor interacting proteins in heteromers [24, 170].

In the A1R‐D1R co‐transfected fibroblast cell line, the expected antagonistic interaction at the level of AC level was observed after A1R and D1R co‐activation [174]. The antagonistic A1R–D1R interaction found at both the recognition and AC levels was found to be correlated, indicating that the inhibitory interaction in the A1R‐D1R heteromer was involved in causing the A1R‐mediated inhibition of D1R signaling.

The available evidence suggests that there exist antagonistic intramembrane A1R–D1R interactions in the dorsal and ventral striatum and in the prefrontal cortex [24, 25, 170, 178]. This involves also an ability of A1R agonists to antagonistically modulate D1R antagonist binding sites in the nucleus accumbens and the prefrontal cortex that cause a reduction of their affinity.

Agonist‐Induced Co‐Aggregation and Co‐Desensitization of A1R‐D1R Heteromers

Permeabilized cells were used and the A1R agonist R‐PIA (100 nM, 1 h) caused aggregates of A1R‐D1R, while the D1R agonist SKF 38393 (10 μM, 1 h) caused clusters of D1R alone, in line with the D1R agonist induced disruption of the A1R‐D1R heteromers [168]. It is of substantial interest that combined treatment with the two agonists, which maintains the heteromerization of A1R and D1R, reduced the co‐aggregation of A1R‐D1R. In this case, a clear‐cut decrease in D1R signaling to the AC was observed. Thus, upon co‐activation of A1R and D1R in the heteromer, with no formation of co‐aggregates and maintenance of A1R‐D1R heteromers, a desensitization of D1R signaling occurs. This desensitization may involve an uncoupling of the D1R in the A1R‐D1R heteromer to the Gs protein. In contrast, A1R‐D1R co‐aggregates (activation of A1R alone) or D1R aggregates (activation of D1R alone) did not result in desensitization of D1R signaling [168]. In contrast to the A1R‐D1R co‐transfected fibroblast cell line, combined treatment with A1R and D1R agonists produced co‐aggregates in cortical nerve cells in culture. Such differential actions may be caused by differences in the stoichiometry and in adapter and scaffolding proteins interacting with the A1R‐D1R heteromers but neverless indicate an important role of A1R and D1R agonists in modulating the cotrafficking of A1R‐D1R heteromers in the forebrain and thus in D1R function.

Function. An A1R antagonistic modulation of D1R signaling was observed in the regulation of transcription factors in the striatum after DA terminal denervation based on analysis of the immediate early gene NGFI‐A and c‐fos mRNA levels and of GABA release in the striato‐entopeduncular GABAergic pathway as studied with microdialysis [178]. The same year behavioral indications for antagonistic A1R–D1R receptor interactions were also obtained with adenosine A1R antagonists potentiating the motor effects of D1R agonists [179]. Collectively, this work in the 1990s indicated the existence of antagonistic intramembrane A1R–D1R interactions reducing D1R signaling in the direct pathways (see [24]).

Relevance to CNS Diseases and their Treatments

The antagonistic interaction in A1R‐D1R heteromers, where D1R is the crucial receptor in view of its important behavioral role, offers a new way to modulate D1R signaling, namely to reduce striatal D1R signaling with A1R agonists and enhance it with A1R antagonists (see [24, 25]). This offers a therapeutic potential for A1R antagonists in Parkinson's disease as seen also by A1R antagonist enhancement of D1R‐induced locomotion. Often, A1R drugs in low doses by themselves have only weak effects in the behavioral models used but can strongly modulate the D1R signaling [179, 180]. This is also beautifully illustrated through microdialysis studies and through the induction of immediate early genes (IEG) (see earlier and [181]). In addition, A1R agonists can strongly counteract the D1R agonist‐induced oral dyskinesias in rabbits [173] indicating a therapeutic potential of A1R agonists in l‐DOPA‐induced dyskinesias in parkinsonian patients by targeting the striatal A1R‐D1R heteromer.

A1R agonists also counteract D1R agonist‐induced electroencephalography (EEG) arousal in rats [182] probably by targeting the postulated A1R‐D1R heteromers in the frontal cortex. A1R antagonists targeting these heteromers may therefore, have a potential therapeutic role in attention deficit hyperactivity disorders (ADHD) by increasing EEG arousal provided it will lead to increased attention. This proposal is supported by the demonstration of sedative‐hypnogenic properties of adenosine analogues that could in part be mediated via A1R‐D1R heteromers in the frontal cortex. In fact, the A1R agonist CPA but not the A2AR agonist CGS 21680 prevents EEG arousal due to D1R activation [182].

Putative A1‐D1‐D3 Receptor Mosaics

As mentioned earlier, a large array of experimental approaches utilizing heterologous expression systems have been used to demonstrate receptor–receptor interactions. Interestingly, by using some of these approaches, namely BRET, FRET, and acceptor photobleaching FRET, a D1R–D3R interaction has been demonstrated [183]. Interestingly, in membrane preparations from bovine striatum the D3R agonist R(+) 7‐OH‐DPAT was found to shift the D1R agonist competition curve to the left ([3H]‐SCH23390 vs. SKF‐38393) demonstrating that D3R activation increases the affinity of the D1R agonist binding sites [183]. These results suggest the existence of synergistic intramembrane D3R–D1R interactions at the level of D1R recognition in striatal D3R‐D1R heteromers. In line with these findings, the D3R agonist PD 128907 is also shown to enhance the actions of the D1R agonist SKF 38393 on locomotion in reserpinized mice [183].

Based on previous work by the Schwartz and Sokoloff group [184, 185, 186], see also [23, 131, 173] and in line with the recent findings of Marcellino et al. [183] it seems likely that D3R‐D1R synergism in their receptor heteromer in the direct striatal pathway may contribute to l‐DOPA‐induced dyskinesias. D3R antagonists acting on the D3R‐D1R heteromer may therefore have anti‐dyskinetic properties. In fact, induction of D3R expression may be one mechanism for behavioral sensitization to l‐DOPA [187]. D3R antagonists blocking D3R‐D1R synergism may also have anti‐cocaine reward properties in view of the D3R up‐regulation found, for example, in reward circuitries of human cocaine fatalities [188] and where both D1R and D3R are involved in cocaine actions [187, 189].

Interestingly, Surmeier et al. [190] found that around 50% of the striato‐nigral and striato‐entopeduncular GABAergic neurons show D3R expression. There is the possibility that at least some of these neurons also express A1R and that not only A1R‐D1R heteromers but also A1‐D1‐D3 RM may be formed in these neurons of the direct pathway. Such a RM composed of three different GPCR types may be an especially important integrative center for transmitter and modulator signals with D1R as the hub receptor and the other two as receptors important for proper D1R function. Therefore, it may be the case that combined treatment with D3R antagonists and A1R agonists could be rational to reduce D1R signaling especially in combination with low doses of D1R antagonists. Overall, this approach may bring about an improved treatment of l‐DOPA‐induced dyskinesias and of cocaine addiction with reduced side effects in view of the lower doses of D1R antagonists that can be used, see [15].

Final Comments

Dopamine receptors in general, and D2R and D1R in particular, may be considered as the functionally most important receptors in several types of striatal GPCR heterodimers. Interestingly, in view of their strong actions on multiple effectors in the striato‐pallidal and striato‐entopeduncular/nigral GABAergic neurons, it is postulated that these dopamine receptors‐containing oligomers are mainly located outside the glutamate and DA synapses (see earlier). The standard treatment, for example, with l‐DOPA and/or DA agonists [191] in PD builds on the activation of these D2R and D1R by moderate to high doses, while the accessory A2AR and A1R and others in the different heterodimers and RM are not targeted.

A novel principle may now be used to develop D2R agonists for treatment of PD based on the existence of various D2R containing heterodimers (two receptors) and RM (three or more receptors; higher‐order oligomers) since the conformational state of the D2R and likely its pharmacology probably differs from one receptor assembly to another. It may also be due to different receptor–protein interactions, and also influenced by the local molecular histology of the surface membrane of discrete striato‐pallidal nerve cell populations and of striatal glutamate and DA nerve terminal networks. Thus, the full or partial agonist pharmacology of D2R in terms of potency and efficacy may show substantial differences among various types of RM such as A2A‐D2‐mGlu5 RM versus A2A‐CB1‐D2 RM versus D2 monomers and homodimers, and A2AR‐D2R and CB1R‐D2R heterodimers etc. The development of specific D2R agonists, specifically for the D2S autoreceptor may be especially hopeful since the D2S autoreceptor participates in unique RM versus the postjunctional D2L receptors. In this way, RMs of D2S autoreceptors and non‐α7 nicotinic receptors have been found in the striatal DA nerve terminals [192], see also [193] as well as direct protein–protein interactions of the D2S autoreceptor with the DA transporter which are disrupted in schizophrenia [194]. This should give exciting new possibilities to develop novel and more selective D2R agonist drugs for treatment of Parkinson's disease by preferentially acting on certain postjunctional RM in the striato‐pallidal GABAergic neurons and their glutamate inputs.