SUMMARY

The circadian nature of melatonin (MLT) secretion, coupled with the localization of MLT receptors to the suprachiasmatic nucleus, has led to numerous studies of the role of MLT in modulation of the sleep‐wake cycle and circadian rhythms in humans. Although much more needs to be understood about the various functions exerted by MLT and its mechanisms of action, three therapeutic agents (ramelteon, prolonged‐release MLT, and agomelatine) are already in use, and MLT receptor agonists are now appearing as new promising treatment options for sleep and circadian‐rhythm related disorders. In this review, emphasis has been placed on medicinal chemistry strategies leading to MLT receptor agonists, and on the evidence supporting therapeutic efficacy of compounds undergoing clinical evaluation. A wide range of clinical trials demonstrated that ramelteon, prolonged‐release MLT and tasimelteon have sleep‐promoting effects, providing an important treatment option for insomnia and transient insomnia, even if the improvements of sleep maintenance appear moderate. Well‐documented effects of agomelatine suggest that this MLT agonist offers an attractive alternative for the treatment of depression, combining efficacy with a favorable side effect profile. Despite a large number of high affinity nonselective MLT receptor agonists, only limited data on MT1 or MT2 subtype‐selective compounds are available up to now. Administration of the MT2‐selective agonist IIK7 to rats has proved to decrease NREM sleep onset latency, suggesting that MT2 receptor subtype is involved in the acute sleep‐promoting action of MLT; rigorous clinical studies are needed to demonstrate this hypothesis. Further clinical candidates based on selective activation of MT1 or MT2 receptors are expected in coming years.

Keywords: Depression, Melatonin, Melatonin receptor agonists, MT1 receptor, MT2 receptor, Sleep disorder

Introduction

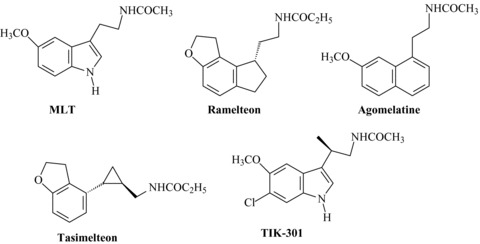

Melatonin (MLT, Figure 1) is the main biologically active substance secreted by the pineal gland, an organ long considered as a vestigial structure, until Lerner, a dermatologist from Yale University, in 1958 isolated an amphibian skin‐lightening molecule, and identified it as N‐acetyl‐5‐methoxytryptamine [1]. Its isolation marked the start of an increasing research effort to identify the endogenous role of MLT and the mechanism by which it regulates the physiology of both mammalian and nonmammalian species.

Figure 1.

Melatonin (MLT) and clinically advanced MLT receptor agonists.

The pineal production of MLT shows a circadian rhythm with low circulating levels during the day and high plasmatic concentrations of hormone at night. This rhythmicity is controlled by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of hypothalamus (the body master clock controlling circadian rhythms), whose activity is synchronized to the 24 h period by the light/dark cycle [2].

Although circulating MLT in mammals is mainly of pineal origin, the hormone is also produced by neuroendocrine cells [3] in the retina, Harderian glands, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, and in minor amounts by nonendocrine cells such as bone marrow, thymus, and lymphocytes, where it may be of some local importance.

The biosynthesis of MLT in the pineal gland involves several steps that can be summarized as follows: pinealocytes take up l‐tryptophan from the cerebral vessels and convert it to serotonin through 5‐hydroxylation and decarboxylation; serotonin is then converted to N‐acetyl‐serotonin by the rate‐limiting enzyme arylalkylamine N‐acetyl transferase, before finally being converted into MLT by hydroxyindole‐O‐methyl transferase.

Once synthesized, MLT is not stored within the pineal gland, but diffuses out into the bloodstream, rapidly reaching all tissues of the body. Circulating MLT is metabolized by cytochrome P‐450 which catalyzes hydroxylation of the hormone at the C‐6 indole position to yield 6‐hydroxymelatonin. This reaction is followed by conjugation with sulfuric acid (or to a lesser extent with glucuronic acid) to produce the principal urinary metabolite, 6‐sulfatoxymelatonin. In the brain MLT can be metabolized to the kynurenine derivative N 1‐acetyl‐5‐methoxykynurenine by oxidative pyrrole‐ring cleavage, or to a cyclic 3‐hydroxymelatonin derivative (1‐{3a‐hydroxy‐5‐methoxy‐3,3a,8,8a‐tetrahydropyrrolo[2,3‐b]indol‐1(2H)‐yl}ethanone).

The absolute bioavailability of MLT in humans after exogenous administration of deuterated D7‐MLT was low (from 1% to 37%) due to first pass metabolism, and a short half‐life (30–45 min) was observed [4].

Much of the research in the first 30 years after the discovery of MLT was related to its ability to modulate reproductive physiology in photoperiod‐dependent seasonally breeding mammals [5]. As a result of these findings, MLT has been successfully used as a pharmacological agent to advance the breeding season of sheep and other photoperiodic animals [6].

During the past four decades MLT has been claimed to have an effect in almost all the main physiological functions of the body. Among the actions attributed to MLT are those concerning circadian rhythms and sleep regulation [7], control of mood and behavior [8], neuroimmunomodulation [9], blood pressure control [10], pain perception [11], antiinflammatory [12], antioxidant [13], neuroprotectant [14], and antitumor [15]. Of particular interest are also the reports on its putative role in the events leading to the development of type 2 diabetes [16, 17].

Although many of the miraculous claims made about MLT are matter of speculation, clinical trials, and results of preclinical studies in validated animal models suggest that some therapeutic options exist for MLT, particularly for the treatment of insomnia, circadian‐rhythm sleep disorders (CRSDs), and depression.

Melatonin Receptors

The therapeutic potential of MLT, and its synthetic analogs, depends critically on our understanding of its target sites and mechanisms of action. Initial attempts to identify receptors using radioligand binding techniques involved the use of [3H]‐MLT [18]. The discovery of different MLT binding sites was facilitated by the synthesis in 1984 of the high‐affinity agonist radioligand 2‐[125I]‐iodoMLT [19] that has made possible autoradiographic studies revealing a widespread distribution of binding sites throughout the nervous system [20]. MLT binding sites are particularly abundant in the retina, the SCN, the pars tuberalis of the pituitary gland, cerebral, and tail arteries [20], but as data continue to accumulate, it seems that few tissues are devoid of MLT membrane receptors [21]. Knowledge of the structure and function of MLT receptors has evolved over the past 15 years, since the cloning of two well‐characterized receptors, now designated by IUPHAR as MT1 and MT2[22, 23, 24]. These receptors are members of a new subfamily of G‐protein‐coupled receptors (GPCRs) that show little sequence homology with other known receptors. Both MT1 and MT2 receptors exhibit subnanomolar binding affinity for MLT and are negatively coupled to adenylate cyclase, even if they can also interact with other intracellular signaling pathways [25]. A third MLT receptor subtype (termed Mel1c), has been cloned from Xenopus laevis, chicken and zebrafish, but it is not expressed in mammals [26]. In addition to these high affinity GPCRs MLT receptors, a distinct binding site (termed MT3), displaying lower affinity for MLT (Ki≅ 10–60 nM), has been purified and characterized as the human enzyme quinone reductase 2 [27]. MLT has also been described as a ligand for the retinoid related orphan nuclear hormone receptor family (RZR/ROR) [28], but the existence of these MLT binding sites is highly controversial, as the direct binding to these receptors has never been reproduced [29, 30]. Finally, a MLT related orphan receptor (GPR50) has been cloned from humans, sheep and rats [31]. Interestingly, this orphan receptor is structurally similar to GPCRs MLT receptors, with a 45% homology at the amino acid level, but it does not bind MLT or related compounds. In mammals, MLT receptors are expressed in the brain, with considerable variation in location and density of expression among species, and also in some peripheral tissues [21, 32]. The diversity in tissue distribution suggests different functional physiological roles for each MLT receptor subtype, but a clear functional distinction among these subtypes needs an intensive further investigation. For example, there is evidence suggesting that activation of MT1 receptors in mouse inhibits neuronal firing within the SCN, inhibits prolactin secretion in photoperiodic species, modulates visual function in the mouse retina [33] and induces vasoconstriction on rat caudal artery; instead, activation of MT2 receptors induces vasodilation, produces a phase shift in circadian rhythms and inhibits dopamine release in rabbit retina (for review see Ref. [21]). Further complexity arises from the formation of MT1 and MT2 homo‐ and heterodimers in cells expressing the two MLT receptor subtypes, and the functional consequences of this association on receptor signaling are currently unknown.

Strategies to Develop Melatonin Agonists

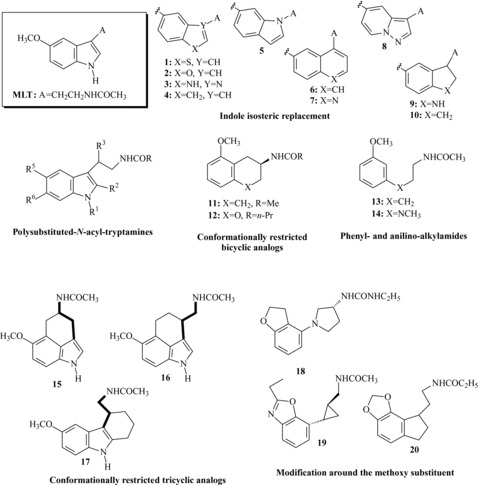

During the last two decades a great number of MLT receptor agonists, belonging to structurally different classes have been reported in literature and in patent applications. The structure‐activity relationships (SARs) for MLT derivatives have already been extensively reviewed [34, 35, 36, 37, 38], and therefore they will be discussed only briefly, highlighting the general strategies used to develop these compounds. Initially, some closely structurally related MLT derivatives (essentially polysubstituted tryptamines, Figure 2) were prepared to investigate the influence of substitutents nature and position on melatonergic activity and to determine the structural elements required for high binding affinity. The pharmacophore structure that can be found in almost all MLT receptor agonists is composed by an amide group connected, by a linker chain, to an aromatic nucleus (mimicking the indole of MLT) carrying a methoxy group, or a bioisostere, such as bromine. Introduction of appropriate substituents (i.e., phenyl or halogens) at the C2‐indole position led to agonists with higher binding affinity (approximately 10‐fold) than MLT itself, such as 2‐iodomelatonin, 2‐bromomelatonin [39], and 2‐phenylmelatonin [40]. Increasing the length of the N‐acyl group, up to three carbons, as well as substitution at the 6‐position of the indole ring were also well tolerated. For instance, 6‐chloromelatonin demonstrated comparable affinity (KiMT1= 0.58 nM; KiMT2= 0.32 nM) to MLT. Combination of a 6‐chlorine with a (R)‐β‐methyl group was reported in the agonist TIK‐301 (Figure 1, previously known as LY156735, Ki= 0.081 and 0.042 nM at MT1 and MT2 receptors, respectively), which was advanced to clinical study for insomnia treatment [41, 42]. Several potent MLT agonists have been designed by bioisosteric replacement of the indole core with other aromatic rings. Successful cases of bioisosteric replacement were the naphthalene ring system (i.e., 6) which is present in agomelatine [43, 44], and the indane (i.e., 10), which is the scaffold of ramelteon [45]. Other scaffolds explored so far include a benzo‐fused skeleton such as benzothiophene, benzofuran, benzoimidazole (compound 1–3[44] in Figure 2), indene 4[46] quinoline 7[47], azaindole 8[48], and indoline 9[49]. Potent MLT bioisosteres were also obtained by shifting the side chain of MLT from 3‐ to 1‐position of the indole ring and the methoxy group from 5‐ to 6‐position (i.e., compound 5) [50]. Partial hydrogenation of the indole nucleus, as for the indoline derivative 9, was also applied to naphthalene derivatives, and the SARs of the resulting tetrahydronaphthalenes [51] were similar to those observed in the indole series. Tetralins (11) [52] and oxygenated heterocycles (such as chromane 12[53]) provide examples of compounds with different core scaffolds, leading to active MLT analogs when the methoxy substituent and the amide group are properly positioned. Further investigations have determined that the bicyclic aromatic nucleus is not essential for melatonergic activity. In fact, simplified analogues such as methoxyphenyl‐ (13) [54], or methoxyanilino‐alkylamides (14) [55] were found to retain good agonist activity.

Figure 2.

Strategies leading to melatonin receptor agonists.

Another approach very commonly applied in the design of novel MLT agonists is the incorporation of the methoxyl group or the acylaminoethyl side chain into a conformationally restricted ring structure; this strategy was also useful in the identification of MLT active conformation at its membrane receptors [35, 38]. Among the various MLT analogs that were prepared as constrained agonists (for extensive reviews see [35, 37, 38]), it is worth mentioning the tricyclic derivatives 16[56, 57] and 17[58], having binding affinities similar to MLT at both receptor subtypes. The alkyl chain can also be constrained in a trans‐cyclopropylmethyl fragment as in tasimelteon (Figure 1), or in a pyrrolidine ring as in compound 18[59] (Figure 2). Incorporation of the critical methoxy group into a five‐ or six‐membered ring [60], as can be seen in dihydrobenzofuran (i.e., ramelteon [45] or compound 18[59]), in benzoxazole (19) [59] and benzo‐1,3‐dioxole (20) [45] derivatives, led to a series of compounds with excellent affinity for MLT receptors.

Melatonin Receptor Agonists in the Management of Insomnia and Major Depression

While synthetic MLT agonists have the potential to modulate a number of disease states, the current clinical focus is primarily on developing treatments to manage insomnia, depression and CRSDs. These are indeed the therapeutic indications for MLT receptor agonists approved for marketing or currently under clinical evaluation. The idea that MLT might promote sleep and synchronize the internal clock stimulated some clinical trials. However, after four decades of investigation, the scientific evidence supporting the sleep‐promoting effects of MLT in different experimental conditions remains controversial [61, 62]. A major obstacle for the use of MLT as a clinically efficient hypnotic results from its short half‐life, which is mostly in the range of 20–40 min, sometimes even less. Solutions to this problem can be sought in developing prolonged‐release formulations of the natural hormone, or melatoninergic agonists with longer half‐life. Both possibilities were considered, resulting in the production of approved or investigative drugs, such as Circadin®, Rozerem®, Valdoxan®, tasimelteon, and other suptype selective MLT receptor agonists.

Circadin®, (Neurim Pharmaceuticals, Tel‐Aviv, Israel) is a prolonged‐release 2 mg MLT formulation that, when taken before bedtime, maintains effective serum concentrations of the endogenous hormone throughout the night. It was approved by the European Medicines Evaluation Agency (EU‐EMEA) in June 2007 for the short‐term treatment of primary insomnia characterized by poor quality of sleep in patients aged 55 years and over.

Placebo controlled clinical trials highlighted, beyond the shortening of sleep latency seen with traditional hypnotics, concomitant improvements in sleep quality and next day alertness [63]. On the contrary, direct evidence for the support of sleep maintenance and total sleep time is poor. In contrast to traditional sedative hypnotics, Circadin® has shown no evidence of impairing cognitive and psychomotor skills, of rebound, dependence or abuse potential and no significant adverse events compared to placebo [64]. Preliminary results of a large‐scale (790 patients) Phase III study for insomnia, showed that 6 months continuous administration of Circadin® is both safe and efficacious, thus demonstrating long term efficacy and safety [65]. Studies on treatment of jet lag and shift work disturbances reported a relatively good efficacy of 2 mg sustained‐release MLT [66]. In exploratory studies Circadin® also improves sleep quality in patients with chronic schizophrenia [67] as well as in patients with major depressive disorders [68].

Ramelteon (Rozerem®, TAK‐375, Figure 1), an indenofuran MLT derivative produced by Takeda Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Osaka, Japan), was the first MLT agonist to be approved by the FDA (July 2005) for the treatment of insomnia characterized by difficulty in sleep onset.

Ramelteon was also filed in March 2007 in E.U. for primary insomnia. Nevertheless, EMEA found the efficacy of ramelteon in improving sleep maintenance insufficient for a marketing authorization [69]. After this negative recommendation, Takeda has withdrawn its European marketing authorization application in September 2008 [70].

Ramelteon binds with high affinity to MT1 and MT2 receptors [45] without significant affinity for a large number of other CNS binding sites [71]. Pharmacokinetic studies revealed that ramelteon is metabolized primarily via oxidation; the major metabolite, named M‐II (2‐hydroxy‐N‐[2‐(2,6,7,8‐tetrahydro‐1H‐indeno[5,4‐b]furan‐8‐yl)ethyl]propanamide), carries a hydroxyl group at the C‐2 position of the propionyl residue, retains good MLT receptors affinity (about 10‐fold less than the binding affinity of the parent molecule) [72], and it is 17‐ to 25‐fold less potent than ramelteon in in vitro functional assays [73]. M‐II also showed a potent sleep promoting action in freely moving cats, and thus it may contribute to pharmacological effects of ramelteon.

Ramelteon has been studied in animal models of insomnia as well as of CRSDs. The agent promotes sleep in freely moving monkeys [74] and cats [75], without causing any significant adverse effects such as learning and memory deficits, impairment of motor coordination, and drug abuse [76]. In addition, it is able to enhance the rate of re‐entrainment in response to a shift in the light/dark cycle in rats [77]. Beneficial effects of ramelteon on sleep have been confirmed in clinical studies, including patients with primary insomnia as well as healthy volunteers undergoing experimentally induced transient insomnia (for review of the randomized controlled trials examining the efficacy and tolerability of ramelteon see Ref. [78]).

Considering the clinical data thus far, ramelteon has consistently demonstrated significant sleep promoting effects, as evidenced by reductions in sleep latency (about 10–13 min more than placebo) and increases in total sleep time (about 12 min), among patients with chronic insomnia [79, 80, 81] and subjects with transient insomnia [82], during both short‐term [79, 82] and long‐term treatment [80, 81]. Although doses used in clinical trials ranged from 4 mg to 64 mg, the recommended dosage for the treatment of insomnia in adults is 8 mg, 30 min prior to the habitual bedtime. As also reported for the other melatonin therapeutic agent approved for the treatment of insomnia, Circadin®, ramelteon has demonstrated no next‐day residual effects, rebound insomnia, or abuse potential in either preclinical animal models or in clinical evaluation in humans, and is therefore not a controlled (scheduled) drug [83].

The naphthalenic MLT bioisostere agomelatine (Valdoxan®, Figure 1), is a novel antidepressant with an innovative pharmacological profile which has been developed by Servier (and Novartis in US). It is a potent MT1/MT2 agonist and also has weak 5‐HT2c antagonist properties. Its antidepressant activity may be due to each of these properties, or to their combination. It does not display significant affinity for other central receptors or membrane transporters. In February 2009, Valdoxan® was approved by the EU‐EMEA for the treatment of major depressive disorders (MDD) and is available in several European countries. Phase III clinical trials of agomelatine for depression (three short‐term efficacy and safety trials and one longer‐term relapse prevention trial) have also been conducted in the United States, but the results from these studies have not been released and agomelatine is not yet approved by the US FDA [84].

The antidepressant activity of agomelatine has been first extensively investigated in preclinical studies before being studied in humans [85, 86]. The efficacy, tolerability and safety of agomelatine have been assessed in several double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐ and active‐controlled Phase III studies. The results of a 8‐week placebo‐controlled dose‐ranging study involving 711 MDD patients, with paroxetine as an active control, indicate that agomelatine, at a dose of 25 mg once daily, has similar efficacy to paroxetine [87]. Further studies versus placebo and comparators have confirmed the efficacy of Valdoxan® in adults of all ages, including the severely depressed and elderly depressed [88, 89, 90]. A study comparing Valdoxan® with venlafaxine showed comparable antidepressant efficacy of both treatments, but significantly less sexual dysfunction of Valdoxan® compared to the Serotonin‐Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRI) [91]. Furthermore, no discontinuation symptoms were observed after cessation of agomelatine treatment in contrast to that found with paroxetine [92]. Besides being an effective antidepressant, agomelatine decreased the severity of anxiety associated with depression, and, unlike other antidepressants, has a markedly positive impact on the often disrupted sleep–wake rhythm of depressed patients, without affecting daytime vigilance [93].

The combined action at MT1, MT2, and 5‐HT2C receptors, which may resynchronize disturbed circadian rhythms and abnormal sleep patterns, suggests that agomelatine might be particularly effective for the treatment of seasonal affective disorders, bipolar depression [94], as well as in other possible subtypes of MDD [95]. Preliminary open‐label studies in these patient populations have suggested some benefits [96, 97] and further studies are clearly warranted.

Another newly investigative synthetic melatoninergic agonist is tasimelteon (Figure 1, formerly known as VEC‐162 or BMS‐214778). This compound, developed by Vanda Pharmaceuticals, under license from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, was tested in two randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trials for its effects on transient insomnia induced by a 5‐h phase advance of the sleep–wake cycle in healthy individuals [98, 99]. Compared with placebo, tasimelteon reported beneficial effects on sleep latency and maintenance at all three tested doses (20 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg), and showed a good safety profile without significant side effects versus placebo. Moreover, the compound was effective in resetting the circadian MLT rhythm after a sleep‐time shift, suggesting that it may be a good candidate for the treatment of CRSDs, especially the jet‐lag and shift‐work types.

Neu‐P11 is a melatonin receptor agonist developed by Neurim Pharmaceuticals that recently started its evaluation in clinical trials. The chemical formula of Neu‐P11 has not been disclosed, even if its sleep promoting activity and improvement in insulin sensitivity have been related to similar effects reported for a series of pyrone‐indole derivatives patented by Neurim Pharmaceuticals [100]. Neu‐P11 is a combined MT1/MT2/MT3 and a 5‐HT1A/5‐HT1B/5‐HT2B agonist; it also enhances GABA activity, but it does not directly interact with GABA receptors. The sleep promoting activity of Neu‐P11 has been evaluated in a double blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled phase I study in which it was administered at the doses of 5 mg, 20 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg [101]. Significant increases in the sedation assessment scores (Stanford Sleepiness Scale) at T + 2 h and T + 4 h were obtained, as well as trends of decreases in number of awakenings and wake after sleep onset (WASO) during the T + 2 h and T + 3 h EEG recording periods, with an increase in theta band activity. Neu‐P11 was also evaluated in preclinical studies for its antidepressant‐like properties [102]. Tests were conducted in rats at the doses of 25/100 mg/kg i.p. In the learned helplessness test rats treated with Neu‐P11 at the dose of 50 mg/kg showed a significant decrease of the escape deficit, similarly to what was observed after imipramine administration. Interestingly, MLT (25/100 mg/kg i.p.) was ineffective. Moreover, Neu‐P11 decreased immobility of rats in the forced swimming test.

Melatonin Receptor Selective Agonists

The development of MLT receptor agonists with improved properties has enhanced the prospects of manipulating the MLT system to treat patients with a range of sleep disorders, or suffering from depression. Unfortunately, none of the most clinically advanced MLT agonists discriminates between MT1 and MT2 MLT receptor subtypes. The development of a subtype‐selective MLT receptor agonist could result in a safer compound with a more favorable pharmacological profile. In the last decade, research on new MLT ligands has expanded to identify selective compounds for either the MT1 or MT2 receptor subtypes [37]. Few examples of MLT receptor agonists (or partial agonists) characterized by selectivity for the MT1 or MT2 receptor are reported in the literature. In most cases they derive from minor structural modifications of nonselective agonists, but a clear indication on the structural requirements characterizing this pharmacological behavior is still lacking.

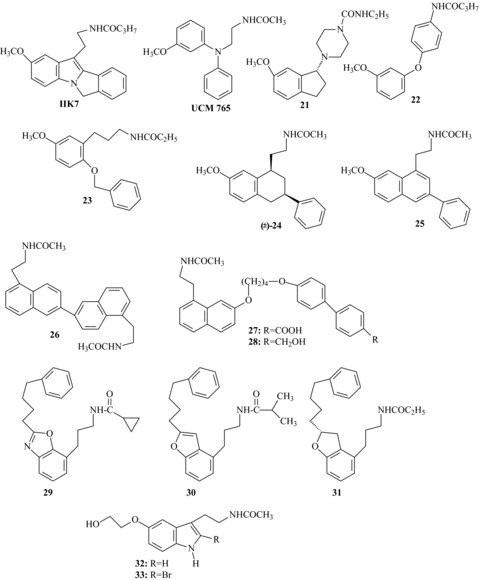

The first high affinity (pKiMT2= 0.05 nM) MT2‐selective agonist to be discovered was the tetracyclic indole derivative IIK7[103] (Figure 3) which has a 90‐fold selectivity for MT2. This compound can be viewed as an analog of 2‐phenylMLT, in which the phenyl substituent is linked to the indole nitrogen by a methylene group. Interestingly, IIK7 administered to rats at a dose of 10 mg/kg i.p. produced a significant decrease in NREM sleep onset latency, suggesting that the MT2 receptor is the subtype involved in the acute sleep‐promoting action of MLT [104]. Similar results were previously reported in a meeting abstract [105], where the authors described the sleep‐promoting properties of another recently developed MT2‐selective partial agonist (UCM765, Figure 3) [55] following subcutaneous administration to rats. However, rodents are active at night, when MLT concentrations are high, and the relevance of these studies has still to be fully assessed.

Figure 3.

Subtype‐ or functionally selective melatonin receptor agonists or partial agonists.

A more pronounced MT2 selectivity (KiMT1/MT2= 117) was displayed by the (R)‐indanylpiperazine 21. This conformationally restricted compound, obtained by incorporating the linking alkyl chain into a piperazine fragment, has been reported to be a full agonist possessing good affinity for the h‐MT2 receptor with little affinity for the MT1 subtype [106].

A series of anilides [107], substituted in para with a 3‐methoxyphenyl‐ether, ‐thioeter, ‐methylene or ‐amino moiety, has been reported to have subnanomolar MT2 affinity and good subtype selectivity. The 4‐(3‐methoxyphenoxy)anilido derivative 22 demonstrated full agonism in a MT2 adenylyl cyclase assay, and 84‐fold selectivity over the MT1 receptor. Starting from MT1/MT2 nonselective 3‐methoxyphenylpropyl amides (i.e., 13), Wong et al. recently discovered new potent MT2‐selective ligands by introduction of a benzyloxy substituent at the C6‐position of the 3‐methoxyphenyl ring (i.e., compound 23) [108]. In binding studies using [3H]‐MLT as radioligand, these compounds exhibited pM to subpM affinity toward MT2 and over 200 nM affinity toward MT1 receptor. Preliminary results suggest that these compounds are potent MT2‐selective agonists as they stimulated intracellular Ca2+ release in CHO cells expressing the MT2 receptor. Finally, it was possible to obtain MT2‐selective partial agonists, by introducing a phenyl substituent at the C3‐position of tetrahydronaphthalene or naphthalene MLT analogs, as exemplified by compounds 24[109] and 25[110].

Attempts to discover MT1‐selective ligands have not yet borne good fruit. Literature only reports few examples of MT1 selective ligands, and this lack has made it difficult to ascertain the physiological role of this receptor subtype. An interesting approach for the design of MLT receptor ligands was the preparation of symmetric dimers, by coupling two moieties deriving from known ligands [111, 112, 113, 114]. Binding affinity, intrinsic activity and subtype selectivity of these dimers depend on the position of the junction and on the length of the linker. Among dimeric agonists, compound 26 (Figure 3), obtained by dimerization of two desmethoxy agomelatine units at the C‐6 position of the aromatic ring, proved to be selective for the MT1 receptor, displaying 50–100‐fold higher binding affinity than at the MT2 receptor [114]. Following the same “bivalent ligands” approach, a series of novel asymmetric heterodimers was recently reported [115], and some of these compounds (27, 28) were described as MT1 selective partial agonists (KiMT2/MT1= 70–90) with subnanomolar affinity.

As stated above, benzoxazole [116], benzofuran or dihydrobenzofuran are core structures able to mimic the methoxyphenyl fragment of MLT. Compounds with subnanomolar affinity and modest selectivity for the MT1 subtype (MT2/MT1 selectivity ratios approximately ranging from 20 to 40) have been obtained when a 4‐phenylbutyl group was introduced at the C2‐position of the bicyclic scaffold, as exemplified by compounds 29[117], 30[118] and 31[119] in Figure 3. By replacement of the methoxy group of MLT with a 5‐hydroxyethoxy substituent interesting compounds were obtained, some of which (32[120], 33[121]) have similar binding affinity for the two receptor subtypes, but functional selectivity on GTPγS binding, as they displayed MT1 agonist and MT2 antagonist properties. Taken together, all these results have led to the hypothesis that MT1 selectivity is favored by replacement of the 5‐methoxy group by a larger substituent.

Conclusion

MLT research is now more than 50 years old and has highlighted that this hormone is an integral part of the homeostatic mechanisms in the body. Since its discovery, several medicinal chemistry approaches have delivered many structurally diverse MLT receptor agonists, which together provided good insights into general pharmacophore requirements of MLT receptors, and have contributed to the knowledge of their putative pharmacological roles. In total, five MLT receptor agonists have advanced to clinical phases (ramelteon, agomelatine, tasimelteon, Neu‐P11, and TIK‐301), two of which are already in therapeutic use together with a prolonged release formulation of MLT. In particular ramelteon and prolonged release MLT, with demonstrated sleep‐promoting effects in clinical trials, coupled with a favorable safety profile and lack of abuse potential or dependence, provide an important treatment option for insomnia. However, it should be noted that the improvements of sleep maintenance for ramelteon appear moderate and no sufficient to obtain marketing authorization by EMEA. The experience with agomelatine across a wide range of clinical trials suggests that this compound can be an attractive alternative for the treatment of major depression, combining efficacy with a favorable side effect profile. Although the field of receptor subtype selectivity has registered some progress in recent years, there is still a clear need for subtype selective MLT receptor agonists which may help to define the multiple functions of MLT. Another poorly investigated field of inquiry is the possible synergistic interaction of MLT receptors with some serotonin receptors (i.e., 5‐HT2c) also known to be important in the management of insomnia and depression.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Lerner AB, Case JD. Structure of melatonin. J Am Chem Soc 1959;81:6084–6085. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Inouye ST, Kawamura H. Persistence of circadian rhythmicity in a mammalian hypothalamic “island” containing the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1979;76:5962–5966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kvetnoy IM. Extrapineal melatonin: Location and role within diffuse neuroendocrine system. Histochem J 1999;31:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fourtillan JB, Brisson AM, Gobin P, Ingrand I, Decourt JP, Girault J. Bioavailability of melatonin in humans after day‐time administration of D7 melatonin. Biopharm Drug Dispos 2000;21:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reiter RJ. Comparative physiology: Pineal gland. Annu Rev Physiol 1973;35:305–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abecia JA, Forcada F, Casao A, Palacin I. Effect of exogenous melatonin on the ovary, the embryo and the establishment of pregnancy in sheep. Animal 2008;2:399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arendt J. Melatonin: Characteristics, concerns, and prospects. J Biol Rhythms 2005;20:291–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Srinivasan V, Smits M, Spence W, et al Melatonin in mood disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry 2006;7:138–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maestroni GJ. The immunotherapeutic potential of melatonin. Expert Opin Invest Drugs 2001;10:467–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Simko F, Pechanova O. Potential roles of melatonin and chronotherapy among the new trends in hypertension treatment. J Pineal Res 2009;47:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ambriz‐Tututi M, Rocha‐González HI, Cruz SL, Granados‐Soto V. Melatonin: A hormone that modulates pain. Life Sci 2009;84:489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mayo JC, Sainz RM, Tan DX, Hardeland R, Leon J, Rodriguez C, Reiter RJ. Anti‐inflammatory actions of melatonin and its metabolites, N1‐acetyl‐N2‐formyl‐5‐methoxykynuramine (AFMK) and N1‐acetyl‐5‐methoxykynuramine (AMK), in macrophages. J Neuroimmunol 2005;165:139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hardeland R. Antioxidative protection by melatonin: Multiplicity of mechanisms from radical detoxification to radical avoidance. Endocrine 2005;27:119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hardeland R. Neuroprotection by radical avoidance: Search for suitable agents. Molecules 2009;14:5054–5102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mills E, Wu P, Seely D, Guyatt G. Melatonin in the treatment of cancer: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials and meta‐analysis. J Pineal Res 2005;39:360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bouatia‐Naji N, Bonnefond A, Cavalcanti‐Proença C, et al A variant near MTNR1B is associated with increased fasting plasma glucose levels and type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet 2009;41:89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mulder H, Nagorny CL, Lyssenko V, Groop L. Melatonin receptors in pancreatic islets: Good morning to a novel type 2 diabetes gene. Diabetologia 2009;52:1240–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Niles LP, Wong Y‐W, Mishra RK, Brown GM. Melatonin receptors in brain. Eur J Pharmacol 1979;55:219–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vakkuri O, Lämsä E, Rahkamaa E, Ruotsalainen H, Leppäluoto J. Iodinated melatonin: Preparation and characterization of the molecular structure by mass and 1H NMR spectroscopy. Anal Biochem 1984;142:284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morgan PJ, Barrett P, Howell HE, Helliwell R. Melatonin receptors: Localization, molecular pharmacology and physiological significance. Neurochem Int 1994;24:101–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dubocovich ML, Markowska M. Functional MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors in mammals. Endocrine 2005;27:101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ebisawa T, Karne S, Lerner MR, Reppert SM. Expression cloning of a high‐affinity melatonin receptor from Xenopus dermal melanophores. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:6133–6137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reppert SM, Weaver DR, Ebisawa T. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian melatonin receptor that mediates reproductive and circadian responses. Neuron 1994;13:1177–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reppert SM, Godson C, Mahle CD, Weaver DR, Slaugenhaupt SA, Gusella JF. Molecular characterization of a second melatonin receptor expressed in human retina and brain: The Mel1b melatonin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1995;92:8734–8738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jockers R, Maurice P, Boutin JA, Delagrange P. Melatonin receptors, heterodimerization, signal transduction and binding sites: What's new Br J Pharmacol 2008;154:1182–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reppert SM, Weaver DR, Cassone VM, Godson C, Kolakowski LF Jr. Melatonin receptors are for the birds: Molecular analysis of two receptor subtypes differentially expressed in chick brain. Neuron 1995;15:1003–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nosjean O, Ferro M, Cogé F, et al Identification of the melatonin‐binding site MT3 as the quinone reductase 2. J Biol Chem 2000;275:31311–31317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Becker‐André M, Wiesenberg I, Schaeren‐Wiemers N, André E, Missbach M, Saurat JH, Carlberg C. Pineal gland hormone melatonin binds and activates an orphan of the nuclear receptor superfamily. J Biol Chem 1994;269:28531–28534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hazlerigg DG, Barrett P, Hastings MH, Morgan PJ. Are nuclear receptors involved in pituitary responsiveness to melatonin Mol Cell Endocrinol 1996;123:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Becker‐André M, Wiesenberg I, Schaeren‐Wiemers N, André E, Missbach M, Saurat JH, Carlberg C. Additions and Corrections to ref. [28]. J Biol Chem 1997;272:16707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reppert SM, Weaver DR, Ebisawa T, Mahale CD, Kolakowski LF. Cloning of a melatonin‐related receptor from human pituitary. FEBS Lett 1996;386:219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ekmekcioglu C. Melatonin receptors in humans: Biological role and clinical relevance. Biomed Pharmacother 2006;60:97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baba K, Pozdeyev N, Mazzoni F, et al Melatonin modulates visual function and cell viability in the mouse retina via the MT1 melatonin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:15043–15048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Steinhilber D, Carlberg C. Melatonin receptor ligands. Exp Opin Ther Patents 1999;9:281–290. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mor M, Plazzi PV, Spadoni G, Tarzia G. Melatonin. Curr Med Chem 1999;6:501–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Witt‐Enderby PA, Li PK. Melatonin receptors and ligands. Vitam Horm 2000;58:321–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zlotos DP. Recent advances in melatonin receptor ligands. Arch Pharm Chem Life Sci 2005;338:229–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rivara S, Mor M, Bedini A, Spadoni G, Tarzia G. Melatonin receptor agonists: SAR and applications to the treatment of sleep‐wake disorders. Curr Top Med Chem 2008;8:954–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Duranti E, Stankov B, Spadoni G, et al 2‐Bromomelatonin: Synthesis and characterization of a potent melatonin agonist. Life Sci 1992;51:479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spadoni G, Stankov B, Duranti A, Biella G, Lucini V, Salvatori A, Fraschini F. 2‐Substituted 5‐methoxy‐N‐acyltryptamines: Synthesis, binding affinity for the melatonin receptor, and evaluation of the biological activity. J Med Chem 1993;36:4069–4074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zemlan FP, Mulchahey JJ, Scharf MB, Mayleben DW, Rosenberg R, Lankford A. The efficacy and safety of the melatonin agonist beta‐methyl‐6‐chloromelatonin in primary insomnia: A randomized, placebo‐controlled, crossover clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:384–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mulchahey JJ, Goldwater DR, Zemlan FP. A single blind, placebo controlled, across groups dose escalation study of the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the melatonin analog β‐methyl‐6‐chloromelatonin. Life Sci 2004;75:1843–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yous S, Andrieux J, Howell HE, et al Novel naphthalenic ligands with high affinity for the melatonin receptors. J Med Chem 1992;35:1484–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Depreux P, Lesieur D, Mansour HA, et al Synthesis and structure‐activity relationships of novel naphthalenic and bioisosteric related amidic derivatives as melatonin receptor ligands. J Med Chem 1994;37:3231–3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uchikawa O, Fukatsu K, Tokunoh R, et al Synthesis of a novel series of tricyclic indan derivatives as melatonin receptor agonists. J Med Chem 2002;45:4222–4239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ohkawa S, Uchikawa O, Fukatsu K, Miyamoto M. PCT Int. Appl 1997; WO9705098 (A1). [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li P‐K, Chu G‐H, Gillen ML, Witt‐Enderby PA. Synthesis and receptor binding studies of quinolinic derivatives as melatonin receptor ligands. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 1997;7:2177–2180. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Elsner J, Boeckler F, Davidson K, Sugden D, Gmeiner P. Bicyclic melatonin receptor agonists containing a ring‐junction nitrogen: Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular modeling of the putative bioactive conformation. Bioorg Med Chem 2006;14:1949–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Beresford IJ, Browning C, Starkey SJ, et al GR196429: A nonindolic agonist at high‐affinity melatonin receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1998;285:1239–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tarzia G, Diamantini G, Di Giacomo B, et al 1‐(2‐Alkanamidoethyl)‐6‐methoxyindole derivatives: A new class of potent indole melatonin analogues. J Med Chem 1997;40:2003–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fourmaintraux E, Depreux P, Lesieur D, Guardiola‐Lemaître B, Bennejean C, Delagrange P, Howell H. Tetrahydronaphthalenic derivatives as new agonist and antagonist ligands for melatonin receptors. Bioorg Med Chem 1998;6:9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Copinga S, Tepper PG, Grol CJ, Horn AS, Dubocovich ML. 2‐Amido‐8‐methoxytetralins: A series of nonindolic melatonin‐like agents. J Med Chem 1993;36:2891–2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sugden D. N‐acyl‐3‐amino‐5‐methoxychromans: A new series of non‐indolic melatonin analogues. Eur J Pharmacol 1994;254:271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Garratt PJ, Travard S, Vonhoff S, Tsotinis A, Sugden D. Mapping the melatonin receptor. 4. Comparison of the binding affinities of a series of substituted phenylalkyl amides. J Med Chem 1996;39:1797–1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rivara S, Lodola A, Mor M, et al N‐(Substituted‐anilinoethyl)amides: Design, synthesis, and pharmacological characterization of a new class of melatonin receptor ligands. J Med Chem 2007;50:6618–6626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Spadoni G, Balsamini C, Diamantini G, et al Conformationally restrained melatonin analogs: Synthesis, binding affinity for the melatonin receptor, evaluation of the biological activity, and molecular modeling study. J Med Chem 1997;40:1990–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rivara S, Diamantini G, Di Giacomo B, et al Reassessing the melatonin pharmacophore: Enantiomeric resolution, pharmacological activity, structure analysis, and molecular modeling of a constrained chiral melatonin analogue. Bioorg Med Chem 2006;14:3383–3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Davies DJ, Garratt PJ, Tocher DA, Vonhoff S, Davies J, Teh MT, Sugden D. Mapping the melatonin receptor. 5. Melatonin agonists and antagonists derived from tetrahydrocyclopent[b]indoles, tetrahydrocarbazoles and hexahydrocyclohept[b]indoles. J Med Chem 1998;41:451–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sun L‐Q, Chen J, Mattson RJ. Heterocyclic aminopyrrolidine derivatives as melatoninergic agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2003;13:4381–4384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Leclerc V, Depreux P, Lesieur D, et al Synthesis and biological activity of conformationally restricted tricyclic analogs of the hormone melatonin. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 1996;6:1071–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhdanova IV. Melatonin as a hypnotic: Pro. Sleep Med Rev 2005;9:51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. van den Heuvel CJ, Ferguson SA, Macchi MM, Dawson D. Melatonin as a hypnotic: Con. Sleep Med Rev 2005;9:71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wade AG, Ford I, Crawford G, McMahon AD, Nir T, Laudon M, Zisapel N. Efficacy of prolonged release melatonin in insomnia patients aged 55–80 years: Quality of sleep and next‐day alertness outcomes. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;23:2597–2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lemoine P, Nir T, Laudon M, Zisapel N. Prolonged‐release melatonin improves sleep quality and morning alertness in insomnia patients aged 55 years and older and has no withdrawal effects. J Sleep Res 2007;16:372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. http://www.neurim.com. [Assessed 27 September 2010[

- 66. Paul MA, Gray G, Sardana TM, Pigeau RA. Melatonin and zopiclone as facilitators of early circadian sleep in operational air transport crews. Aviat Space Environ Med 2004;75:439–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shamir E, Laudon M, Barak Y, Anis Y, Rotenberg V, Elizur A, Zisapel N. Melatonin improves sleep quality of patients with chronic schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61:373–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dolberg OT, Hirschmann S, Grunhaus L. Melatonin for the treatment of sleep disturbances in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:1119–11121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use was concerned that the company had not demonstrated the effectiveness of Ramelteon, which was measured considering only one aspect of insomnia, the time to fall asleep. In addition, in only one of the three studies in a natural setting there was a difference in time to fall asleep between patients taking Ramelteon and those taking placebo, and this difference was considered too small to be relevant. When other aspects of sleep were considered, Ramelteon did not have any effect. The Committee was also concerned that the company had not demonstrated the long‐term effectiveness of Ramelteon. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/000838/smops/Negative/human_smop_000029.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d127&murl=menus/medicines/medicines.jsp&jsenabled=true [Assessed 27 September 2010.

- 70. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Medicine_QA/2010/01/WC500064662.pdf [Assessed 27 September 2010]

- 71. McGechan A, Wellington K. Ramelteon. CNS Drugs 2005;19:1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Karim A, Tolbert D, Cao C. Disposition kinetics and tolerance of escalating single doses of ramelteon, a high affinity MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptor agonist indicated for the treatment of insomnia. J Clin Pharmacol 2006;46:140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kato K, Hirai K, Nishiyama K, et al Neurochemical properties of ramelteon (TAK‐375), a selective MT1/MT2 receptor agonist. Neuropharmacology 2005;48:301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yukuhiro N, Kimura H, Nishikawa H, Ohkawa S, Yoshikubo S, Miyamoto M. Effects of ramelteon (TAK‐375) on nocturnal sleep in freely moving monkeys. Brain Res 2004;1027:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Miyamoto M, Nishikawa H, Doken Y, Hirai K, Uchikawa O, Ohkawa S. The sleep‐promoting action of ramelteon (TAK‐375) in freely moving cats. Sleep 2004;27:1319–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. France CP, Weltman RH, Koek W, Cruz CM, McMahon LR. Acute and chronic effects of ramelteon in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta): Dependence liability studies. Behav Neurosci 2006;120:535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hirai K, Kita M, Ohta H, Nishikawa H, Fujiwara Y, Ohkawa S, Miyamoto M. Ramelteon (TAK‐375) accelerates reentrainment of circadian rhythm after a phase advance of the light‐dark cycle in rats. J Biol Rhythms 2005;20:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Miyamoto M. Pharmacology of ramelteon, a selective MT1/MT2 receptor agonist: A novel therapeutic drug for sleep disorders. CNS Neurosci Ther 2009;15:32–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Erman M, Seiden D, Zammit G, Sainati S, Zhang J. An efficacy, safety, and dose‐response study of ramelteon in patients with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep Med 2006;7:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zammit G, Erman M, Weigand S, Sainati S, Zhang J, Roth T. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of ramelteon in subjects with chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med 2007;3:495–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Roth T, Seiden D, Wang‐Weigand S, Zhang J. A 2‐night, 3‐period, crossover study of ramelteon's efficacy and safety in older adults with chronic insomnia. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;23:1005–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Roth T, Stubbs C, Walsh JK. Ramelteon (TAK‐375), a selective MT1/MT2‐receptor agonist, reduces latency to persistent sleep in a model of transient insomnia related to a novel sleep environment. Sleep 2005;28:303–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Griffiths RR, Suess P, Johnson M. Ramelteon and triazolam in humans: Behavioral effects and abuse potential. In: 19th Annual Meeting Associated Professional Sleep Societies, LLC. Denver, CO, 18–23 June 2005. Sleep 2005;28(Suppl):A44 [Abstract 0132. [Google Scholar]

- 84. US National Institute of Health . Available from: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00463242?term=agomelatine&rank=1 [Assessed 27 September 2010]

- 85. Papp M, Gruca P, Boyer PA, Mocaër E. Effect of agomelatine in the chronic mild stress model of depression in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003;28:694–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bourin M, Mocaer E, Porsolt R. Antidepressant‐like activity of S 20098 (agomelatine) in the forced swimming test in rodents: Involvement of melatonin and serotonin receptors. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2004;29:126–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Loo H, Hale A, D’Haenen H. Determination of the dose of agomelatine, a melatoninergic agonist and selective 5‐HT2C antagonist, in the treatment of major depressive disorder: A placebo‐controlled dose range study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2002;17:239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kennedy S, Emsley R. Placebo‐controlled trial of agomelatine in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2006;16:93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Montgomery SA, Kasper S. Severe depression and antidepressants. Focus on pooled analysis of placebo‐controlled studies on agomelatine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2007;22:283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Olie JP, Kasper S. Efficacy of agomelatine, a MT1/MT2 receptor agonist with 5‐HT2C antagonistic properties, in major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2007;10:661–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Kennedy SH, Rizvi S, Fulton K, Rasmussen J. A double‐blind comparison of sexual functioning, antidepressant efficacy, and tolerability between agomelatine and venlafaxine XR. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2008;28:329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Montgomery SA, Kennedy SH, Burrows GD, Lejoyeux M, Hindmarch I. Absence of discontinuation symptoms with agomelatine and occurrence of discontinuation symptoms with paroxetine: A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled discontinuation study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;19:271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Lemoine P, Guilleminault C, Alvarez E. Improvement in subjective sleep in major depressive disorder with a novel antidepressant agomelatine: Randomized double‐blind comparison with venlafaxine. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:1723–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Pandi‐Perumal SR, Moscovitch A, Srinivasan V, Spence DW, Cardinali DP, Brown GM. Bidirectional communication between sleep and circadian rhythms and its implications for depression: Lessons from agomelatine. Prog Neurobiol 2009;88:264–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Lichtenberg P, Belmaker RH. Subtyping major depressive disorder. Psycother Psychosom 2010;79:131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Calabrese JR, Guelfi JD, Perdrizet‐Chevallier C. Agomelatine adjunctive therapy for acute bipolar depression: Preliminary open data. Bipolar Disord 2007;9:628–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Pjrek E, Winkler D, Konstantinidis A, Willeit M, Praschak‐Rieder N, Kasper S. Agomelatine in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder. Psychopharmacology 2007;190:575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Rajaratnam SM, Polymeropoulos MH, Fisher DM, Roth T, Scott C, Birznieks G, Klerman EB. Melatonin agonist tasimelteon (VEC‐162) for transient insomnia after sleep‐time shift: Two randomised controlled multicentre trials. Lancet 2009;373:482–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. http://www.vandapharma.com/development.html [Assessed 27 September 2010]

- 100. Laudon M, Peleg‐Shulman T. Pyrone‐indole derivatives and process for their preparation. US7,635,710 B2, 2009.

- 101. Yalkinoglu Ö, Zisapel N, Nir T, et al Phase‐I study of the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and sleep promoting activity of Neu‐p11, a novel putative insomnia drug in healthy humans. In: 24th Annual Meeting Associated Professional Sleep Societies, LLC San Antonio, TX, 5–9 June 2010. Sleep 2010;33(Suppl.):A220 [Abstract 0656. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Tian S, Laudon M, Han L, Gao J, Huang F, Yang Y, Deng H. Antidepressant‐ and anxiolytic effects of the novel melatonin agonist Neu‐P11 in rodent models. Acta Pharmacol Sinica 2010;31:775–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Faust R, Garratt PJ, Jones R, et al Mapping the melatonin receptor 6. Melatonin agonists and antagonists derived from 6H‐isoindolo[2,1‐a]indoles, 5,6‐dihydroindolo[2,1‐a]isoquinolines, and 6,7‐dihydro‐5H‐benzo‐[c]azepino[2,1‐a]indoles J Med Chem 2000;43:1050–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Fisher SP, Sugden D. Sleep‐promoting action of IIK7, a selective MT2 melatonin receptor agonist in the rat. Neurosci Lett 2009;457:93–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Sanchez RO, Cohen G, Spadoni G, et al Selective increase of Slow Wave Sleep (SWS) by a novel melatonin partial agonist. In: 37th Annual Meeting Neuroscience . San Diego , CA , 37 November 2007. [Abstract poster 735.22/UU9.

- 106. Mattson RJ, Catt JD, Keavy D, et al Indanyl piperazines as melatonergic MT2 selective agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2003;13:1199–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Epperson JR, Deskus JA, Gentile AJ, Iben LG, Ryan E, Sarbin NS. 4‐Substituted anilides as selective melatonin MT2 receptor agonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2004;14:1023–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Hu Y, Ho MK, Chan KH, New DC, Wong YH. Synthesis of substituted N‐[3‐(3‐methoxyphenyl)propyl] amides as highly potent MT2‐selective melatonin ligands. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2010;20:2582–2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Yous S, Durieux‐Poissonnier S, Lipka‐Belloli E, et al Design and synthesis of 3‐phenyl‐tetrahydronaphthalenic derivatives as new selective MT2 melatoninergic ligands. Bioorg Med Chem 2003;11:753–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Poissonnier‐Durieux S, Ettaoussi M, Pérès B, et al Synthesis of 3‐phenylnaphthalenic derivatives as new selective MT2 melatoninergic ligands. Bioorg Med Chem 2008;16:8339–8348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Descamps‐Francois C, Yous S, Chavatte P, et al Design and synthesis of naphthalenic dimers as selective MT1 melatoninergic ligands. J Med Chem 2003;46:1127–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Larraya C, Guillard J, Renard P, et al Preparation of 4‐azaindole and 7‐azaindole dimers with a bisalkoxyalkyl spacer in order to preferentially target melatonin MT1 receptors over melatonin MT2 receptors. Eur J Med Chem 2004;39:515–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Di Giacomo B, Bedini A, Spadoni G, Tarzia G, Fraschini F, Pannacci M, Lucini V. Synthesis and biological activity of new melatonin dimeric derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem 2007;15:4643–4650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Audinot V, Mailliet F, Lahaye‐Brasseur C, et al New selective ligands of human cloned melatonin MT1 and MT2 receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol 2003;367:553–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Mesangeau C, Peres B, Descamps‐Francois C, et al Design, synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of novel naphthalenic derivatives as selective MT1 melatoninergic ligands. Bioorg Med Chem 2010;18:3426–3436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Sun LQ, Chen J, Takaki K, et al Design and synthesis of benzoxazole derivatives as novel melatoninergic ligands. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2004;14:1197–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Sun LQ, Chen J, Bruce M, et al Synthesis and structure‐activity relationship of novel benzoxazole derivatives as melatonin receptor agonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2004;14:3799–3802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Sun LQ, Takaki K, Chen J, et al N‐[2‐[2‐(4‐Phenylbutyl)benzofuran‐4‐yl]cyclopropylmethyl] acetamide: An orally bioavailable melatonin receptor agonist. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2004;14:5157–5160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Sun LQ, Takaki K, Chen J, et al (R)‐2‐(4‐Phenylbutyl)dihydrobenzofuran derivatives as melatoninergic agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2005;15:1345–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Nonno R, Lucini V, Spadoni G, et al A new melatonin receptor ligand with mt1‐agonist and MT2‐antagonist properties. J Pineal Res 2000;29:234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Spadoni G, Bedini A, Guidi T, Tarzia G, Lucini V, Pannacci M, Fraschini F. Towards the development of mixed MT1‐agonist/MT2‐antagonist melatonin receptor ligands. Chem Med Chem 2006;1:1099–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]