SUMMARY

Huntington's disease is a debilitating neurodegenerative condition with significant burdens on both patient and healthcare costs. Despite the identification of the causative element, an expanded toxic polyglutamine tract in the mutant Huntingtin protein, treatment options for patients with this disease remain limited. In the following review I assess the current evidence suggesting that a family of important regulatory proteins known as histone deacetylases may be an important therapeutic target in the treatment of this disease.

Keywords: Epigenetics, Histone deacetylase, Huntington's disease, Neuromuscular disease

Huntington's Disease

Huntington's disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant, late‐onset neurodegenerative disease characterized by cognitive dysfunction, psychiatric symptoms and movement disorders [1]. The disease is caused by an expansion of a polyglutamine repeat within the amino terminus of the predominantly cytosolic protein huntingtin [2, 3]. The expanded repeat region results in nuclear translocation and aggregation of huntingtin, and has been implicated as the causative event in the pathogenesis of this disease [4, 5, 6].

Evidence Linking Histone PTM Machinery with Huntington's Disease

KATs and HDACs

Several studies have shown that the repeat‐containing mutant huntingtin interacts directly with the histone acetyltransferases KAT3A (CBP) and KAT2B (P/CAF) [7, 8, 9, 10]. This complex has been shown to associate with p53 and to repress transcription of p21WAF1/CIP1 and MDR‐1 [8].

Evidence also continues to accumulate implicating the functional association of huntingtin protein with histone deacetylases (HDACs). Two studies have shown that huntingtin associates with the HDAC‐binding proteins mSin3a and N‐CoR, which would indicate that a complex containing HDACs may be recruited [8, 11]. One of the recently identified functions of mutant huntingtin is that it acts to increase nuclear corepressor function and enhances ligand‐dependent nuclear hormone receptor activation [12].

Additional support for the importance of histone deacetylases in HD comes from a caenorhabditis elegans model, where specific targeting of HDACs was found be capable of reducing the associated neurodegeneration in worm neurons [13].

HDAC6 has been shown to be a microtubule‐associated deacetylase [14]. Defects in microtubule‐based transport have been shown to contribute to neuronal toxicity in HD [15, 16, 17]. In a recent study examining tubulin acetylation in HD it was found that levels of acetylated tubulin were reduced in the brains of Huntingtons patients. Subsequent in vitro cell studies targeting the microtubule specific deacetylase HDAC6 was found to result in increased acetylation at lysine 40 of alpha‐tubulin, and resulted in the alleviateion of transport‐ and release‐defect phenotypes in the cell models [18].

PPAR gamma coactivator 1alpha (PGC‐1alpha) has also been linked to the development and pathogenesis of HD. Two studies have now shown that particular small nucleotied polymorphisms (SNPs) most particularly within intron‐2 of the gene for PGC‐1alpha are associated with a delay in age at onset of motor symptoms in patients with HD [19, 20]. It is well established that PGC‐1alpha functions as a transcriptional coactivator/corepressor through associations with both KATs and HDACs to regulate expression of genes involved with mitochondrial energy and metabolism [21]. Significantly studies have shown reduced levels of PGC‐1alpha in the muscle of HD patients, and in the muscle of HD transgenic mice, while “knockdown” of mutant Htt in myoblasts leads to increased PGC‐1alpha [22]. Early studies also demonstrated the reduced expression of PGC‐1alpha target genes in both HD patient and mouse striatum [23]. When PGC‐1alpha knockout (KO) mice were crossbred with HD knockin (KI) mice, increased neurodegeneration of striatal neurons and motor abnormalities occurred in the HD mice. Additionally expression of PGC‐1alpha was able to partially reverse the toxic effects of mutant huntingtin on cultured striatal neurons, while lentiviral‐mediated PGC‐1alpha in the striatum of the transgenic HD mice provided neuroprotection [24].

Lysine Methyltransferases (KMTs)

Levels of trimethylated histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3) are elevated in both HD patients and in R6/2 transgenic mice, and are associated with markedly increased levels of the lysine methyltransferase KMT1E (also known as known as ESET/SETDB1) [25]. This enzyme methylates H3K9me3, and while this is generally considered to be a mark of transcriptional repression and heterochromatinization [26], it has also been associated with active transcription genes particularly in disease states such as cancer [27].

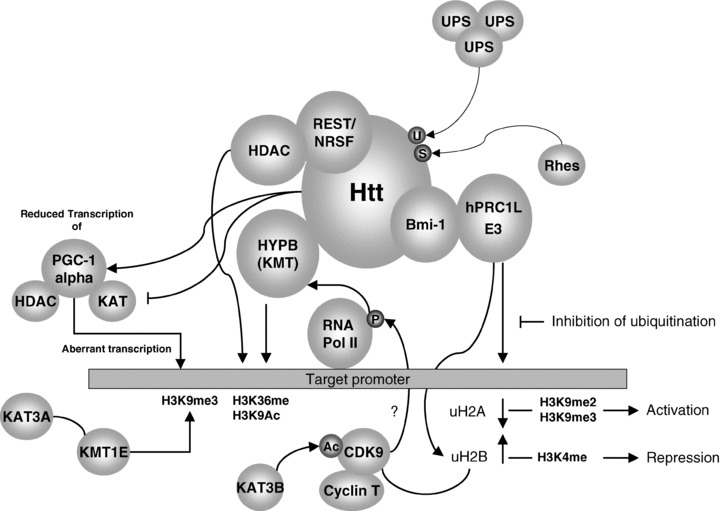

A link between histone acetylation and ESET mediated H3K9me3 was found when monoallelic deletion of KAT3A (CBP) resulted in the induction of KMT1E (ESET) with concommitant increased H3K9me3 in neurons [28]. This may indicate that KAT3A (CBP) is a transcriptional repressor of KMT1E (ESET) gene expression raising the notion that increased KAT activity may be a way of targeting the aberrant KMT1E (ESET) mediated H3K9me3 levels in patients with HD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

An overview of various pathways involving epigenetic regulators in Huntington's disease.

RE1 Silencing Transcription Factor/Neuron‐Restrictive Silencer Factor (REST/NRSF)

Levels of the micro‐RNA miR‐9/miR‐9A have also been shown to be downregulated in HD [29]. In the same study this micro‐RNA was shown to regulate the expression of RE1 silencing transcription factor/neuron‐restrictive silencer factor (REST/NRSF), a critical repressor complex known to associate with both Htt [30], KMTs and HDACs [31]. Indeed, REST/NRSF has been shown to regulate a number of miRNAs [32, 33]. As nuclear REST/NRSF activty is increased in HD patients, a series of miRNAs identified as being regulated by REST/NRSF were subsequently shown to be downregulated in HD patients [34].

Aberrant Gene Expression Caused by Alterations to the Histone Code in Huntington's Disease

Because Htt has been shown to associate with the cellular machinery responsible for regulating the histone code, it was postulated that this may lead to aberrant gene expression in patients suffering from HD. One of the most important features of the association of mutant Htt and KATs was that the nuclear localization of KAT3A (CBP) is altered such that it aggregated into intranuclear inclusions in neuronal cells [8, 10]. Thus a depletion of this HAT from its normal localization may result in aberrant transcriptional control. However, cell‐free assays have shown that the mutant huntingtin protein also has the ability to directly inhibit the activity of the KATs KAT3A (CBP), KAT3B (p300) and KAT2A (P/CAF) [9] (Figure 1), and thus a direct interference mechanism may also be involved. In addition, a cell line model of neuronal death found that mutant protein was associated with degradation of KAT3A (CBP) indicating that the mutant Htt may actively eliminate this KAT from the affected neurons [35, 36, 37].

Microarray gene profiling studies on HD patients have identified a subset of up‐regulated mRNAs that can distinguish between controls, presymptomatic individuals carrying the HD mutation, and symptomatic HD patients [38]. Furthermore, in a microarray analysis of a yeast model of expanded polyglutamine tracts, the changes in gene expression profiles closely matched those of yeast strains deleted for components of the SAGA (Spt/Ada/Gcn5 acetyltransferase) lysine acetyltransferase complex [39]. Additional evidence came from studies in transgenic mice models of HD. For example, histone H3 is hypo‐acetylated at promoters of downregulated genes of R6/2 transgenic mice [40, 41], while in transgenic N171–82Q [82Q] and R6/2 HD mice the reduced histone 3 lysine 9 acetylation (H3K9Ac) is concomitant with increased histone lysine 9 methylation (H3K9me) and associated gene expression changes (Figure 1) [41].

Htt has been shown to associate with the REST/NRSF repressor complex [30]. Normally neuronal REST is largely sequestered together with Htt in the cytoplasm, but mutant Htt is unable to form such a complex resulting in increased translocation of REST/NRSF to the nucleus with associated aberrant repression of its target genes (Figure 1) [30], and this increased binding of REST/NRSF was confirmed at multiple genomic RE1/NRSE loci in HD cells, animal models, and postmortem brains [42].

In the R6/2 transgenic mouse model of HD, nuclear activation of the mitogen‐activated protein kinase/extracellular regulated kinase (ERK) failed to induce histone H3 phosphorylation, an expected response of nuclear ERK activation. It was subsequently found that this was due to a decrease in expression of mitogen‐ and stress‐activated kinase‐1 (MSK‐1) a kinase downstream ERK, critically involved in H3 phosphorylation, a finding subsequently confirmed in the striatal neurons and postmortem brains of HD patients, and suggesting that aberrant MSK‐1 expression is involved with the transcriptional dysregulation and striatal degeneration in patients with HD [43].

Mutant huntingtin has also been shown to affect histone monoubiquitylation. The functional consequence of this results in aberrant gene expression via altered histone methylation. In their initial study Kim et al., found that in a cell line model, mutant Htt was found to have disrupted interactions with Bmi‐1, a component of the hPRC1L E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (Figure 1). This resulted in increased levels of monoubiquityl histone H2A (uH2A). When gene expression patterns were examined in the brains of transgenic R6/2 mice, promoters of genes which were repressed were found to have increased levels of uH2A and decreased levels of uH2B, while active promoters had the opposite (increased u2H2B and decreased uH2A). Furthermore, targeting histone ubiquitin in cell line models demonstrated that reducing uH2A led to the reactivation of repressed genes associated with a reduction in levels of H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 at the reactivated promoters. Conversely reductions of uH2B induced transcriptional repression through inhibition of monomethylation at histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me) (Figure 1) [44].

In yeast, deubiquitylation of H2B initiates in the recruitment of a complex containing the kinase Ctk1. Ctk1 phosphorylates the RNA polymerase II (Pol II) C‐terminal domain (CTD), an event essential for the subsequent recruitment of KMT3A (Set2) lysine methyltransferase [45]. This KMT functions at one level to regulate RNA Pol II elongation [46, 47, 48, 49, 50]. However, KMT3a (Set2) mediated H3K36 methylation also functions to recruit histone deacetylase complexes to restore normal chromatin structure in the wake of elongating Pol II [51, 52]. Critically, a homologue of Set2 has now been shown to be the huntingtin interacting protein B (HYPB) (Figure 1). This protein contains active histone H3 lysine 36 specific KMTase activity. This suggests that HYPB KMTase may coordinate histone methylation and transcriptional regulation, and play critical roles in the pathogenesis of HD [53]. While to my knowledge no data has yet emerged on whether the human homologue of Ctk1, cyclin dependent kinase 9 (Cdk9) associates with HYPB, it is well established that the P‐TEFb, comprising of CDK9 and a cyclin T subunit, is a global transcriptional elongation factor important for most RNA polymerase II (pol II) transcription in eukaryotes [54], and it has been established that the activity of P‐TEFb itself is regulated through acetylation of CDK9 [55]. Thus it is highly likely that interactions between CDK9 and HYPB may occur.

The evidence is now overwhelming that mutant Htt results in aberrant transcription regulation via its interactions with the cellular machinery whose role is to modify/regulate the histone code. Therefore, targeting this cellular transcriptional machinery may help to alleviate symptoms of this disease.

Evidence for a Protein Code in Huntington's Disease

The activities of enzymes such as histone deacetylases are not strictly limited to histones, and indeed HDACs play important roles in regulating various proteins though acetylation [56]. It is now well established that the Huntingtin protein itself undergoes many PTMs (Figure 1, Table 1), all of which which can have important clinical implications for HD pathogenesis.

Table 1.

Sites in the Htt protein which undergo PTMs.

| Sumoylation |

| K6, K9, K15 (67) |

| Ubiquitination |

| K6, K9, K15 (67) |

| Phosphorylation |

| T3 (142) |

| S13 (62, 142) |

| S16 (62) |

| T407 (143) |

| S413 (143) |

| S421 (57, 59, 60, 144, 145, 146) |

| S434 (58) |

| S533 (147) |

| S535 (147) |

| S536 (147) |

| S1181 (61, 147, 148) |

| S1872 (143, 148) |

| S1876 (143, 149) |

| S1201 (61, 147, 148, 150)] |

| S2076 (147) |

| S2653 (147) |

| S2657 (147) |

| T2940 (143) |

| Acetylation |

| K6 (142) |

| Palmitoylation |

| C214 (151) |

The table was generated through a combination of literature searches and through the use of SysPTM (http://lifecenter.sgst.cn/SysPTM) (152), and through PhosphoSitePlus® (http://www.phosphosite.org/).

Htt Phosphorylation

For instance phosphorylation of serines (S6/S13) promotes the degradation of Htt by both the proteasome and lysosomes. These modifications however also result in enhanced translocation of Htt to the nucleus, which may result in both aberrant gene expression and enhanced neurodegeneration over time. In contrast, a different study demonstrated that phosphorylation of Htt on serine‐421 (S421) reduced nuclear accumulation of huntingtin fragments by (i) reducing huntingtin cleavage by caspase‐6, (ii) the levels of full‐length huntingtin, and (iii) its nuclear localization [57]. Phosphorylation of serine 434 (S434) by CDK5 was found to reduce caspase‐mediated htt cleavage at alanine residue 513 (A513) [58].

Phosphorylation of Htt may also regulate Htt function, as phosphorylation at S431 restores its axonal transport [59], whereas phosphorylation of Htt at S431 by Akt is critical to controlling the direction of vesicles in neurons [60].

Phosphorylation of Serines S1181 and S1201 are critical to HD pathogenesis. If phosphorylation is absent at these two residues this confers toxic properties to wild‐type huntingtin in a p53‐dependent manner in striatal neurons and accelerates neuronal death induced by DNA damage, while if present they prevent these effects [61].

Recently it has also been shown that phosphorylation of mutant Htt by the inflammatory kinase IKK, regulates additional posttranslational modifications, including Htt ubiquitination, SUMOylation, and acetylation, resulting in increased Htt nuclear localization, cleavage, and clearance mediated by lysosomal‐associated membrane protein 2A and Hsc70 [62].

Htt Acetylation

Acetylation of Htt has been shown to target the mutant protein to autophagosomes for degradation. Increased acetylation at a critical lysine (K444) was recently shown to facilitate the trafficking of mutant Htt into autophagosomes, and significantly improved the clearance of the mutant protein by macroautophagy. In experimental models this reversed the toxic effects of mutant huntingtin in primary striatal and cortical neurons and in a transgenic C. elegans model of HD. If the protein was altered to be resistant to acetylation this resulted in dramatic aggregation leading to neurodegeneration in cultured neurons and in mouse brain [63].

Htt Ubiquitination/Sumoylation

Modification of proteins with polyubiquitin chains regulates many essential cellular processes including protein degradation, cell cycle, transcription, DNA repair and membrane trafficking. As discussed in previous sections monubiquitination of histones has been shown to generate altered gene transcription in mouse models of Huntington's [44].

Aggregation‐prone proteins have been suggested to overwhelm and impair the ubiquitin/proteasome system (UPS) in polyglutamine (polyQ) disorders, such as HD. Using a model of mutant Htt to test this possibility it was shown that accumulation of ubiquitin conjugates in the HD disease model occured without global ubiquitin/proteasome system impairment [64]. However two separate studies have also found that UPS dysfunction is a consistent feature of HD pathology with impaired UPS in the synapses of HD mice [65], and with polyubiquitination chains occurring on Htt lysines‐11, ‐48 and ‐63 [66].

Htt has also been shown to be either ubiquinated or sumoylated at the same lysine residues (K6, K9, and K15). Critically, sumoylation of these residues stabilized the Htt reducing its ability to form aggregates, enhanced transcriptional repression, and exacerbated neurodegeneration in a drosphila model of HD. In contrast ubiqiuination of these residues abrogated neurodegeneration in the same model [67]. More recently, a novel striatial protein Rhes has been shown to associate with Htt (Figure 1). This protein has now been shown to induce Htt sumoylation leading to neuronal cytotoxicity [68].

Linking Inflammation to the Huntington's Protein Code

It is well established that inflammation is a central element of HD. Cultured cells expressing mutant Htt and striatal cells from HD transgenic mice have been shown to have elevated nuclear factor‐kappaB (NFkappaB) activity [69]. Furthermore, several family members of the I‐kappa‐B Kinase (IKK) proteins have been shown to be functionally involved in HD. The IKK proteins are critical reguulators of NFkB. Indeed in the study demonstrating activation of NFkB, it was found that mutant Htt associated with and activated IKKgamma [69]. Additional studies have shown that both IKKalpha and IKKbeta are involved in the proteolysis of Htt in response to external cues such as DNA damage [70].

IKK has been shown to phosphorylate Huntingtin which targets it for degradation by the proteasome and lysosome [62]. Critically once phosphorylated IKK regulates additional posttranslational modifications, of Htt including ubiquitination, SUMOylation, and acetylation. Furthermore, this subsequently enhances Htt nuclear localization, cleavage, and clearance mediated by lysosomal‐associated membrane protein 2A and Hsc70. The authors propose that IKK activates mutant Htt clearance until an age‐related loss of proteasome/lysosome function promotes accumulation of toxic posttranslationally modified mutant Htt [62].

ER Stress

The ability of a cell to sense, response to and circumvent stress is essential for maintaining homeostasis. There are many ways in which stress, either endogenous or exogenous, can be manifested in a cell; these include pathogenic infection, chemical insult, genetic mutation, nutrient deprivation, and even normal differentiation. The process of mutant protein folding is particularly sensitive to such insults. As such for the cellular compartments in which mutant proteins are processed and folded, there are adaptive programs that enable both their detection and correction for more efficient processing [71].

The ER is a large cellular organelle comprising a network of interconnected, closed membrane‐bound vesicles. It is the site of synthesis, folding and modification of secretory and cell‐surface proteins and serves many essential functions, including the production of the components of cellular membranes, proteins, lipids, and sterols [72]. Only correctly folded proteins are transported out of the ER while incompletely folded proteins are retained in the organelle to complete the folding process or to be targeted for destruction [73]. Due to the important roles of this organelle, its proper functioning is essential to cellular homeostasis. However, various conditions can interfere with the ER function leading to ER stress. Stress is the response of any system to perturbations of its normal state. Thus, ER stress can arise from a disturbance in protein folding which results in an accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins within the organelle [74]. During such disturbances, in order to carry out the correct folding of proteins, the ER has evolved as a specialized protein folding machine with cellular mechanisms that promote proper folding of aberrant protein, thus preventing its aggregation. Therefore, when ER homeostasis is altered by misfolded proteins the ER responds by inducing the expression of specific genes in an attempt to restore normal ER function to and maintain stability [75]. The principle mechanisms of conformational disorders contained within the four pillars of Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) stress: [1] Protein degradation, [2] Endoplasmic overload response (EOR), [3] Unfolded protein response (UPR), and [7] Cellular Death pathway. This four‐stage model of ER Stress toxicity helps explain its role in the onset of clinical manifestations. Two ER stress‐induced signal transduction pathways have been described: the UPR [76] and the EOR [77]. The function of these pathways is to adapt to the disturbance and attempt to re‐establish normal ER function [78], and in the case of misfolded proteins this is known as ER‐associated degradation (ERAD), the process by which these misfolded proteins are exported to the cytosol for degradation by proteasomes [79]. However, excessive or prolonged ER stress may overwhelm the cells ability to cope and elicits the cell death program or apoptosis [80].

ER Stress and Huntington's Disease

The first indication that ER Stress may be involved with HD cam from a study of aggresome‐like perinuclear inclusions generated using huntingtin exon 1 truncated protein model in human 293 Tet‐Off cells. In depth analysis of these inclusion bodies demonstrated the presence of markers of ER stress including the the molecular chaperones BiP/GRP78, Hsp70, and Hsp40 [81].

Mutant huntingtin fragment proteins have now been shown to elevate Bip (another ER chaperone), increase levels of Chop and the phosphorylation of c‐Jun‐N‐terminal kinase (JNK)(regulators of cell death), and cleavage of Caspases‐3 and ‐12 (mediators of cell death). Inhibition of ER stress using salubrinal counteracted both neuronal cell death and protein aggregation by mutant Htt [82]. Functional anlysis of Htt has identified a membrane association signal in the form of an amphipathic alpha helical membrane‐binding domain that can reversibly target to vesicles and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Normal Htt is released from these membrans n response to ER stress and rapidly translocates into the nucleus. Once ER stress has been alleviated the Htt is capable of nuclear export and re‐association with the ER. However, this release is inhibited when huntingtin contains the polyglutamine expansion seen in HD. As a result, mutant huntingtin expressing cells have a perturbed ER and an increase in autophagic vesicles, indicating that one of Htt's functions is to act as ER sentinel, potentially regulating autophagy in response to ER stress [83, 84]. Mutant Htt has also been shown to interact with and abrogate the function of gp78, a critical ER membrane‐anchored ubiquitin ligase (E3) involved in ERAD resulting in the induction of ER stress [85].

Overexpression of HspB8, a small heat shock protein has been shown to prevent mutant Htt aggregation by an autophagic activity [86, 87, 88, 89]. Furthermore, a novel protein, SCAMP5, which functions to regulate the formation of expanded polyglutamine repeat protein aggregates has been shown to be induced in cultured striatal neurons by either endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress or mutant HTT [90].

ER Stress has also been shown to upregulate expression of early disease markers in a presymptomatic knock‐in mouse model of HD [91]. These markers, regulator of ribosome synthesis Rrs1 and its interacting protein 3D3/lyric (also known as metadherin and astrocyte elevated gene‐1), were found to be localized in the ER, are induced by ER stress, and are involved in the ER stress response in neuronal cells. Indeed levels of Rrs1 mRNA have been shown to be elevated in the brains of HD patients [92]. Furthermore, in the Hdh knock‐in mice model, ER stress was found to occur prior to the formation of amyloid intranuclear or cytoplasmic inclusions indicating that it plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of HD [91]. Postmortem analysis of patient brains has found increased mRNA expression of the ER Stress‐related genes BiP, CHOP, and Herpud1 in HD Postmortem Brain [91].

Taken together these results clearly indicate a critical role for ER Stress inHD pathogenesis.

HATs/HDACs and ER Stress

The evidence linking HATs/HDACs to ER Stress is not as well established as that for inflammation, and most studies which link these proteins to ER stress have utilized histone deacetylase inhibitors. However, a recent study on Mallory body (cytokeratin aggresomes) formation in hepatocytes found decreased histone acetyltransferase activity with a concommitant increase in histone deacetylase activity [93]. Similarly in a study on oxidative stress induced inclusion formation, treatment of cells with the histone deacetylase inhibitor 4‐phenylbutyrate alleviated formation of such inclusions [94].

Now, direct associations between HATs and HDACs with critical regulatory elements within the ER Stress pathway are emerging. CHOP (C/EBP Homologous Protein) an ER stress‐inducible protein which plays a critical role in regulating programmed cell death in stressed cells has now been shown to directly associate with the histone acetyltransferase p300, and inhibition of HDACs prevents the degradation of CHOP [95].

Chromatin immunoprecipitation studies have shown that ER Stress regulators are regulated at the transcriptional level via histone posttranslational modifications [96]. For instance, p300 has been shown to bind to the promotor for the GRP78/BiP [97], while CHOP has been shown to be regulated by a complex containing JDP2 and HDAC3 [98].

B lymphocyte‐induced maturation protein‐1 (BLIMP‐1) has been shown to be associated with cellular stress and is rapidly upregulated during the UPR in some models [99]. Interestingly this repressor protein directly associates with HDACs to repress transcription [100], and may therefore indicate that BLIMP‐1 may utilize HDACs to downregulate important genes during ER stress.

ER Stress and the Ubiquitin Proteosome System

As discussed in previous sections the UPS system in HD is severely disrupted. ER stress has been shown to have a general inhibitory effect on the UPS [101], which may explain the long‐term gradual accumulation of misfolded proteins in patients with HD. Intriquingly in a neurodegenerative model for spinobulbar muscular atrophy, it was found that compensatory autophagy was induced to compensate for impaired UPS function in an HDAC6‐dependent manner [102]. In addition HDAC6 overexpression was sufficient to rescue the degeneration associated with UPS dysfunction in vivo in an autophagy‐dependent manner [102]. As such it may be possible to use antagonists of HDAC6 as an intervention to induce a compensatory autophagy in HD. However it has also been shown that inhibitors targeting HDAC6 alleviates the microtubule transport‐ and release‐defect phenotypes associated with HD [18].

HDAC6 would appear to be the critical regulator controling cellular response pathways to cytotoxic accumulation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates. Initially HDAC6 was shown to interacts with both dynenin motors and misfolded proteins to form an active transport system to transport misfolded proteins to the aggresome [103].

HDAC6 also plays a role in regulating chaperone‐mediated responses to cellular stress. Impairment of proteasome activity by ubiquitinated cellular aggregates is essential to trigger a HDAC6‐dependent cell response involving the induction of major cellular chaperones by triggering the dissociation of a repressive HDAC6/HSF1 (heat‐shock factor 1)/HSP90 (heat‐shock protein 90) complex [104].

These and other data showing that HDAC6 is critical component of environmentallly induced stress granules [105], popint to an essential role for HDAC6 as a cellular stress surveillance factor, where it can acts as both a sensor an effector of stressful stimuli mediating and coordinating appropriate cellular responses [106].

Targeting ER Stress via HDACi

There are indications that HDACi may have a role in reducing or alleviating ER Stress in disease. For instance, the valproate/valproic acid upregulates the expression of GRP78/BiP, a key ER‐mediated chaperone [107]. Valproate can also increase the expression of additional important endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins, GRP94/HSP90B1 and calreticulin in cultured brain cells [108, 109, 110], which results in a neuroprotective capacity [111, 112, 113].

In vitro data has emerged which indicates that another histone deacetylase inhibitor, 4‐Phenylbutyrate, is also able to act as a chemical chaperone to alleviate ER stress in various disease models including models of ischemia [114, 115], cataract formation [116], retinitis pigmentosa [117], glaucoma [118], and cystic fibrosis [119]. 4‐Phenybutyrate has also been shown to relieve the ER stress observed in diabetes, where it has been shown to reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes, by the restoration of systemic insulin sensitivity, resolution of fatty liver disease, and enhancement of insulin action in liver, muscle, and adipose tissues [120]. Furthermore, in hepatocytes, ER stress in liver induced ischemia is ameliorated by treatments with 4‐Phenylbutyrate [115], and alleviates oxidative stress induced ER stress in cultured hepatocytes and hepatoma cells [94].

The ability of 4‐phenylbutyrate to act as a chemical chaperone has also been observed in three models of diseases involving the accumulation of protein aggregates mutant alpha1‐ATZ (alpha1‐ATZ) [121], parkinsons disease [122], and hereditary haemochromatosis (HH) [123].

Taken together, it would appear that HDACs may be valid targets for alleviating ER Stress in HD. In the following sections I describe the current evidence that suggests HDACi have therapeutic potential in the treatment of HD.

HDAC Inhibitors in Models of Huntington's Disease

Sodium Butyrate

In a cell culture model treatment of cells with sodium butyrate caused the redistribution of Huntingtin‐positive nuclear bodies [124]. The first indications that HDAC inhibitors may prove useful in the treatment of Huntingtons came from yeast and fly models where treatments of HD models were found arrest neurodegeneration or mitigated the effects on affected gene promoters [9, 39].

Phenylbutyrate

Following on from these studies it has since been shown that the HDAC inhibitors SAHA, sodium butyrate and phenylbutyrate can ameliorate Huntington motor deficits in mouse models [125, 126, 127].

In vitro and in vivo models of huntington's using ST14a/STHdh cells and R2/6 mice demonstrated a marked histone H3 hypoacetylation in downregulated genes, and treatment with HDAC inhibitors was found to both reverse the mRNA abnormalities, and led to histone acetylation at the promoters of these genes [40].

Currently clinical trial are undergoing in relation to the use of PB to treat HD. A Phase II safety and tolerability trial (NCT00212316) has been completed and a serum analysis has identified individual‐specific patterns of ca. 20 metabolites, which could provide a means for the selection of subjects for extended trials using this drug [128].

Valproic Acid (Depakene® Depakote®)

Early clinical trials examining the use of this compound for the treatment of HD were disappointing, and did not show any clinical benefit [129, 130, 131]. More recent studies have shown that some benefit can be accrued in HD patients either as specific montherapy [132] or as a combination therapy with olanzipine [133].

A recent paper has shown that high dose valproate treatment of the transgenic mouse N171–82Q model of HD significantly prolonged survival and ameliorated their diminished spontaneous locomotor activity, without exerting any noteworthy side‐effect on their behavior or the striatal dopamine content at the dose administered (daily i.p., 100 mg/kg) [134]. It must be noted that there has been one report linking valproic acid treatment with Pisa syndrome in a patient with HD [135].

Other HDACi

In the R6/2 transgenic mouse model of HD, a novel pimelic diphenylamide HDAC inhibitor, HDACi 4b, significantly improved motor performance, overall appearance, and body weight of symptomatic mice, with associated significant attenuation of gross brain‐size decline and striatal atrophy [136].

On Jan 8th, 2010, Siena Biotech announced the initiation of a Phase I clinical study involving single‐ and multiple‐doses study with a randomized, double‐blind and placebo‐controlled design to assess safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of SEN0014196 an orally active, selective Sirt1 inhibitor SEN0014196 (6‐chloro‐2,3,4,9‐tetrahydro‐1H‐carbazole‐1‐carboxamide), as a disease‐modifying therapy in HD.

Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid (SAHA)

Several studies have now shown that the first FDA approved histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA (Zolinza®) has efficacy in modulating the severity of HD models.

SAHA is a pan‐specific HDACi broadly inhibiting inhibit the class I, II, and IV HDACs [137], but it has also been shown to specifically downregulate HDAC7 [138]. In agreement with this, Bates and colleagues demonstrated that SAHA was functionally able to decrease the levels of HDAC7 in the mice of both wid‐type and the R6/2 transgenic mouse model of HD [139]. Despite this complete genetic loss of HDAC7 did not alleviate the symptoms in HD models [139]. As such, HDAC7 would not appear to be the main target for the therapeutic benefits of HDACi in HD models.

While it has pan‐HDACi activity, SAHA has also been shown to inhibit HDAC6. This deacetylase has a special function in that it deacetylates microtubules in vitro and in vivo[14]. HDAC6 may therefore be an important target in HD as levels of tubulin acetylation were also found to be reduced in HD brains, while treatment with the HDACi TSA ameliorated the phenotypic effects of HD [18]. Indeed, microtubule dynamics associated with HDAC6 have also been shown to be of broad potential interest in conditions of neurodegeneration. In Alzheimers disease the protein tau has been shown to inhibit HDAC6 resulting in increased microtubule acetylation, and prevents the induction of autophagy by inhibiting proteasome function [140]. Similarly, HDAC6 has also been shown to regulate the cellular location of Parkin, a protein‐ubiquitin E3 ligase linked to Parkinson's disease [141].

Conclusions

The previous sections have described how HDACs may be influencing the pathogenesis of HD, and have shown that inhibitors for these proteins affect many of the pathways involved in the disease process. Several HDAC inhibitors have good safety/tolerability profiles and are undergoing clinical trials in neurodegenerative disease. It therefore seems imperative that these drugs should continue to be tested for their potential therapeutic role in patients afflicted with HD.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Walker FO. Huntington's disease. Lancet 2007;369:218–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase K, et al Huntingtin is a cytoplasmic protein associated with vesicles in human and rat brain neurons. Neuron 1995;14:1075–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Group THsDCR . A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington's disease chromosomes. Cell 1993;72:971–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klement IA, Skinner PJ, Kaytor MD, et al. Ataxin‐1 nuclear localization and aggregation: Role in polyglutamine‐induced disease in SCA1 transgenic mice. Cell 1998;95:41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sieradzan KA, Mechan AO, Jones L, Wanker EE, Nukina N, Mann DM. Huntington's disease intranuclear inclusions contain truncated, ubiquitinated huntingtin protein. Exp Neurol 1999;156:92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saudou F, Finkbeiner S, Devys D, Greenberg ME. Huntingtin acts in the nucleus to induce apoptosis but death does not correlate with the formation of intranuclear inclusions. Cell 1998;95:55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kazantsev A, Preisinger E, Dranovsky A, Goldgaber D, Housman D. Insoluble detergent‐resistant aggregates form between pathological and nonpathological lengths of polyglutamine in mammalian Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:11404–11409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steffan JS, Kazantsev A, Spasic‐Boskovic O, et al The Huntington's disease protein interacts with p53 and CREB‐binding protein and represses transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97:6763–6768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Steffan JS, Bodai L, Pallos J, et al Histone deacetylase inhibitors arrest polyglutamine‐dependent neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Nature 2001;413:739–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nucifora FC, Jr ., Sasaki M, Peters MF, et al Interference by huntingtin and atrophin‐1 with cbp‐mediated transcription leading to cellular toxicity. Science 2001;291:2423–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boutell JM, Thomas P, Neal JW, et al Aberrant interactions of transcriptional repressor proteins with the Huntington's disease gene product, huntingtin. Hum Mol Genet 1999;8:1647–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yohrling GJ, Farrell LA, Hollenberg AN, Cha JH. Mutant huntingtin increases nuclear corepressor function and enhances ligand‐dependent nuclear hormone receptor activation. Mol Cell Neurosci 2003;23:28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bates EA, Victor M, Jones AK, Shi Y, Hart AC. Differential contributions of Caenorhabditis elegans histone deacetylases to huntingtin polyglutamine toxicity. J Neurosci 2006;26:2830–2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hubbert C, Guardiola A, Shao R, et al HDAC6 is a microtubule‐associated deacetylase. Nature 2002;417:455–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Muchowski PJ, Ning K, D'Souza‐Schorey C, Fields S. Requirement of an intact microtubule cytoskeleton for aggregation and inclusion body formation by a mutant huntingtin fragment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:727–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoffner G, Kahlem P, Djian P. Perinuclear localization of huntingtin as a consequence of its binding to microtubules through an interaction with beta‐tubulin: Relevance to Huntington's disease. J Cell Sci 2002;115:941–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trushina E, Heldebrant MP, Perez‐Terzic CM, et al Microtubule destabilization and nuclear entry are sequential steps leading to toxicity in Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:12171–12176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dompierre JP, Godin JD, Charrin BC, et al Histone deacetylase 6 inhibition compensates for the transport deficit in Huntington's disease by increasing tubulin acetylation. J Neurosci 2007;27:3571–3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weydt P, Soyal SM, Gellera C, et al The gene coding for PGC‐1alpha modifies age at onset in Huntington's Disease. Mol Neurodegener 2009;4:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Taherzadeh‐Fard E, Saft C, Andrich J, Wieczorek S, Arning L. PGC‐1alpha as modifier of onset age in Huntington disease. Mol Neurodegener 2009;4:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lawless MW, O’Byrne KJ, Gray SG. Oxidative stress induced lung cancer and COPD: Opportunities for epigenetic therapy. J Cell Mol Med 2009;13:2800–2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chaturvedi RK, Adhihetty P, Shukla S, et al Impaired PGC‐1alpha function in muscle in Huntington's disease. Hum Mol Genet 2009;18:3048–3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weydt P, Pineda VV, Torrence AE, et al Thermoregulatory and metabolic defects in Huntington's disease transgenic mice implicate PGC‐1alpha in Huntington's disease neurodegeneration. Cell Metab 2006;4:349–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cui L, Jeong H, Borovecki F, Parkhurst CN, Tanese N, Krainc D. Transcriptional repression of PGC‐1alpha by mutant huntingtin leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration. Cell 2006;127:59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ryu H, Lee J, Hagerty SW, et al ESET/SETDB1 gene expression and histone H3 (K9) trimethylation in Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:19176–19181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hublitz P, Albert M, Peters AH. Mechanisms of transcriptional repression by histone lysine methylation. Int J Dev Biol 2009;53:335–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wiencke JK, Zheng S, Morrison Z, Yeh RF. Differentially expressed genes are marked by histone 3 lysine 9 trimethylation in human cancer cells. Oncogene 2008;27:2412–2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee J, Hagerty S, Cormier KA, et al Monoallele deletion of CBP leads to pericentromeric heterochromatin condensation through ESET expression and histone H3 (K9) methylation. Hum Mol Genet 2008;17:1774–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Packer AN, Xing Y, Harper SQ, Jones L, Davidson BL. The bifunctional microRNA miR‐9/miR‐9* regulates REST and CoREST and is downregulated in Huntington's disease. J Neurosci 2008;28:14341–14346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zuccato C, Tartari M, Crotti A, et al Huntingtin interacts with REST/NRSF to modulate the transcription of NRSE‐controlled neuronal genes. Nat Genet 2003;35:76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gray SG. Histone deacetylase inhibitors as a therapeutic modality in multiple sclerosis In: Zouali M, editor. The epigenetics of autoimmune diseases. Chichester , West Sussex : Wiley‐Blackwell, 2009;403–432. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu J, Xie X. Comparative sequence analysis reveals an intricate network among REST, CREB and miRNA in mediating neuronal gene expression. Genome Biol 2006;7:R85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Conaco C, Otto S, Han JJ, Mandel G. Reciprocal actions of REST and a microRNA promote neuronal identity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:2422–2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bithell A, Johnson R, Buckley NJ. Transcriptional dysregulation of coding and non‐coding genes in cellular models of Huntington's disease. Biochem Soc Trans 2009;37:1270–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jiang H, Nucifora FC, Jr ., Ross CA, DeFranco DB. Cell death triggered by polyglutamine‐expanded huntingtin in a neuronal cell line is associated with degradation of CREB‐binding protein. Hum Mol Genet 2003;12:11–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cong SY, Pepers BA, Evert BO, et al Mutant huntingtin represses CBP, but not p300, by binding and protein degradation. Mol Cell Neurosci 2005;30:560–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jiang H, Poirier MA, Liang Y, et al Depletion of CBP is directly linked with cellular toxicity caused by mutant huntingtin. Neurobiol Dis 2006;23:543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Borovecki F, Lovrecic L, Zhou J, et al Genome‐wide expression profiling of human blood reveals biomarkers for Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:11023–11028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hughes RE, Lo RS, Davis C, et al Altered transcription in yeast expressing expanded polyglutamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:13201–13206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sadri‐Vakili G, Bouzou B, Benn CL, et al Histones associated with downregulated genes are hypo‐acetylated in Huntington's disease models. Hum Mol Genet 2007;16:1293–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stack EC, Del Signore SJ, Luthi‐Carter R, et al Modulation of nucleosome dynamics in Huntington's disease. Hum Mol Genet 2007;16:1164–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zuccato C, Belyaev N, Conforti P, et al Widespread disruption of repressor element‐1 silencing transcription factor/neuron‐restrictive silencer factor occupancy at its target genes in Huntington's disease. J Neurosci 2007;27:6972–6983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Roze E, Betuing S, Deyts C, et al Mitogen‐ and stress‐activated protein kinase‐1 deficiency is involved in expanded‐huntingtin‐induced transcriptional dysregulation and striatal death. Faseb J 2008;22:1083–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim MO, Chawla P, Overland RP, Xia E, Sadri‐Vakili G, Cha JH. Altered histone monoubiquitylation mediated by mutant huntingtin induces transcriptional dysregulation. J Neurosci 2008;28:3947–3957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wyce A, Xiao T, Whelan KA, et al H2B ubiquitylation acts as a barrier to Ctk1 nucleosomal recruitment prior to removal by Ubp8 within a SAGA‐related complex. Mol Cell 2007;27:275–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Morris SA, Shibata Y, Noma K, et al Histone H3 K36 methylation is associated with transcription elongation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Eukaryot Cell 2005;4:1446–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schaft D, Roguev A, Kotovic KM, et al The histone 3 lysine 36 methyltransferase, SET2, is involved in transcriptional elongation. Nucleic Acids Res 2003;31:2475–2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xiao T, Hall H, Kizer KO, et al Phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II CTD regulates H3 methylation in yeast. Genes Dev 2003;17:654–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li B, Howe L, Anderson S, Yates JR, 3rd , Workman JL. The Set2 histone methyltransferase functions through the phosphorylated carboxyl‐terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem 2003;278:8897–8903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Krogan NJ, Kim M, Tong A, et al Methylation of histone H3 by Set2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is linked to transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol 2003;23:4207–4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lee JS, Shilatifard A. A site to remember: H3K36 methylation a mark for histone deacetylation. Mutat Res 2007;618:130–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Keogh MC, Kurdistani SK, Morris SA, et al Cotranscriptional set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 recruits a repressive Rpd3 complex. Cell 2005;123:593–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sun XJ, Wei J, Wu XY, et al Identification and characterization of a novel human histone H3 lysine 36‐specific methyltransferase. J Biol Chem 2005;280:35261–35271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bres V, Yoh SM, Jones KA. The multi‐tasking P‐TEFb complex. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2008;20:334–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fu J, Yoon HG, Qin J, Wong J. Regulation of P‐TEFb elongation complex activity by CDK9 acetylation. Mol Cell Biol 2007;27:4641–4651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xu WS, Parmigiani RB, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: Molecular mechanisms of action. Oncogene 2007;26:5541–5552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Warby SC, Doty CN, Graham RK, Shively J, Singaraja RR, Hayden MR. Phosphorylation of huntingtin reduces the accumulation of its nuclear fragments. Mol Cell Neurosci 2009;40:121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Luo S, Vacher C, Davies JE, Rubinsztein DC. Cdk5 phosphorylation of huntingtin reduces its cleavage by caspases: Implications for mutant huntingtin toxicity. J Cell Biol 2005;169:647–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zala D, Colin E, Rangone H, Liot G, Humbert S, Saudou F. Phosphorylation of mutant huntingtin at S421 restores anterograde and retrograde transport in neurons. Hum Mol Genet 2008;17:3837–3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Colin E, Zala D, Liot G, et al Huntingtin phosphorylation acts as a molecular switch for anterograde/retrograde transport in neurons. Embo J 2008;27:2124–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Anne SL, Saudou F, Humbert S. Phosphorylation of huntingtin by cyclin‐dependent kinase 5 is induced by DNA damage and regulates wild‐type and mutant huntingtin toxicity in neurons. J Neurosci 2007;27:7318–7328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Thompson LM, Aiken CT, Kaltenbach LS, et al IKK phosphorylates Huntingtin and targets it for degradation by the proteasome and lysosome. J Cell Biol 2009;187:1083–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jeong H, Then F, Melia TJ, Jr ., et al Acetylation targets mutant huntingtin to autophagosomes for degradation. Cell 2009;137:60–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Maynard CJ, Bottcher C, Ortega Z, et al Accumulation of ubiquitin conjugates in a polyglutamine disease model occurs without global ubiquitin/proteasome system impairment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:13986–13991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wang J, Wang CE, Orr A, Tydlacka S, Li SH, Li XJ. Impaired ubiquitin‐proteasome system activity in the synapses of Huntington's disease mice. J Cell Biol 2008;180:1177–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bennett EJ, Shaler TA, Woodman B, et al Global changes to the ubiquitin system in Huntington's disease. Nature 2007;448:704–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Steffan JS, Agrawal N, Pallos J, et al SUMO modification of Huntingtin and Huntington's disease pathology. Science 2004;304:100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Subramaniam S, Sixt KM, Barrow R, Snyder SH. Rhes, a striatal specific protein, mediates mutant‐huntingtin cytotoxicity. Science 2009;324:1327–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Khoshnan A, Ko J, Watkin EE, Paige LA, Reinhart PH, Patterson PH. Activation of the IkappaB kinase complex and nuclear factor‐kappaB contributes to mutant huntingtin neurotoxicity. J Neurosci 2004;24:7999–8008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Khoshnan A, Ko J, Tescu S, Brundin P, Patterson PH. IKKalpha and IKKbeta regulation of DNA damage‐induced cleavage of huntingtin. PLoS One 2009;4:e5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rutkowski DT, Kaufman RJ. A trip to the ER: Coping with stress. Trends Cell Biol 2004;14:20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hebert DN, Molinari M. In and out of the ER: Protein folding, quality control, degradation, and related human diseases. Physiol Rev 2007;87:1377–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Rapoport TA. Protein translocation across the eukaryotic endoplasmic reticulum and bacterial plasma membranes. Nature 2007;450:663–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lai E, Teodoro T, Volchuk A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Signaling the unfolded protein response. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Caruso ME, Chevet E. Systems biology of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Subcell Biochem 2007;43:277–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007;8:519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Pahl HL, Baeuerle PA. The ER‐overload response: Activation of NF‐kappa B. Trends Biochem Sci 1997;22:63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Xu C, Bailly‐Maitre B, Reed JC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Cell life and death decisions. J Clin Invest 2005;115:2656–2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Vembar SS, Brodsky JL. One step at a time: Endoplasmic reticulum‐associated degradation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008;9:944–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rao RV, Ellerby HM, Bredesen DE. Coupling endoplasmic reticulum stress to the cell death program. Cell Death Differ 2004;11:372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Waelter S, Boeddrich A, Lurz R, et al Accumulation of mutant huntingtin fragments in aggresome‐like inclusion bodies as a result of insufficient protein degradation. Mol Biol Cell 2001;12:1393–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Reijonen S, Putkonen N, Norremolle A, Lindholm D, Korhonen L. Inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress counteracts neuronal cell death and protein aggregation caused by N‐terminal mutant huntingtin proteins. Exp Cell Res 2008;314:950–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Atwal RS, Truant R. A stress sensitive ER membrane‐association domain in Huntingtin protein defines a potential role for Huntingtin in the regulation of autophagy. Autophagy 2008;4:91–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Atwal RS, Xia J, Pinchev D, Taylor J, Epand RM, Truant R. Huntingtin has a membrane association signal that can modulate huntingtin aggregation, nuclear entry and toxicity. Hum Mol Genet 2007;16:2600–2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Yang H, Liu C, Zhong Y, Luo S, Monteiro MJ, Fang S. Huntingtin interacts with the cue domain of gp78 and inhibits gp78 binding to ubiquitin and p97/VCP. PLoS One 2010;5:e8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Carra S, Sivilotti M, Chavez Zobel AT, Lambert H, Landry J. HspB8, a small heat shock protein mutated in human neuromuscular disorders, has in vivo chaperone activity in cultured cells. Hum Mol Genet 2005;14:1659–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Carra S, Seguin SJ, Landry J. HspB8 and Bag3: A new chaperone complex targeting misfolded proteins to macroautophagy. Autophagy 2008;4:237–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Carra S, Seguin SJ, Lambert H, Landry J. HspB8 chaperone activity toward poly(Q)‐containing proteins depends on its association with Bag3, a stimulator of macroautophagy. J Biol Chem 2008;283:1437–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Carra S, Brunsting JF, Lambert H, Landry J, Kampinga HH. HspB8 participates in protein quality control by a non‐chaperone‐like mechanism that requires eIF2{alpha} phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 2009;284:5523–5532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Noh JY, Lee H, Song S, et al SCAMP5 links endoplasmic reticulum stress to the accumulation of expanded polyglutamine protein aggregates via endocytosis inhibition. J Biol Chem 2009;284:11318–11325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Carnemolla A, Fossale E, Agostoni E, et al Rrs1 is involved in endoplasmic reticulum stress response in Huntington disease. J Biol Chem 2009;284:18167–18173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Fossale E, Wheeler VC, Vrbanac V, et al Identification of a presymptomatic molecular phenotype in Hdh CAG knock‐in mice. Hum Mol Genet 2002;11:2233–2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Bardag‐Gorce F, Dedes J, French BA, Oliva JV, Li J, French SW. Mallory body formation is associated with epigenetic phenotypic change in hepatocytes in vivo. Exp Mol Pathol 2007;83:160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Hanada S, Harada M, Kumemura H, et al Oxidative stress induces the endoplasmic reticulum stress and facilitates inclusion formation in cultured cells. J Hepatol 2007;47:93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Ohoka N, Hattori T, Kitagawa M, Onozaki K, Hayashi H. Critical and Functional Regulation of CHOP (C/EBP Homologous Protein) through the N‐terminal Portion. J Biol Chem 2007;282:35687–35694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Donati G, Imbriano C, Mantovani R. Dynamic recruitment of transcription factors and epigenetic changes on the ER stress response gene promoters. Nucleic Acids Res 2006;34:3116–3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Baumeister P, Luo S, Skarnes WC, et al Endoplasmic reticulum stress induction of the Grp78/BiP promoter: Activating mechanisms mediated by YY1 and its interactive chromatin modifiers. Mol Cell Biol 2005;25:4529–4540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Cherasse Y, Chaveroux C, Jousse C, et al Role of the repressor JDP2 in the amino acid‐regulated transcription of CHOP. FEBS Lett 2008;582:1537–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Doody GM, Stephenson S, Tooze RM. BLIMP‐1 is a target of cellular stress and downstream of the unfolded protein response. Eur J Immunol 2006;36:1572–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Yu J, Angelin‐Duclos C, Greenwood J, Liao J, Calame K. Transcriptional repression by blimp‐1 (PRDI‐BF1) involves recruitment of histone deacetylase. Mol Cell Biol 2000;20:2592–2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Menendez‐Benito V, Verhoef LG, Masucci MG, Dantuma NP. Endoplasmic reticulum stress compromises the ubiquitin‐proteasome system. Hum Mol Genet 2005;14:2787–2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Pandey UB, Nie Z, Batlevi Y, et al HDAC6 rescues neurodegeneration and provides an essential link between autophagy and the UPS. Nature 2007;447:859–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Kawaguchi Y, Kovacs JJ, McLaurin A, Vance JM, Ito A, Yao TP. The deacetylase HDAC6 regulates aggresome formation and cell viability in response to misfolded protein stress. Cell 2003;115:727–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Boyault C, Zhang Y, Fritah S, et al HDAC6 controls major cell response pathways to cytotoxic accumulation of protein aggregates. Genes Dev 2007;21:2172–2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Kwon S, Zhang Y, Matthias P. The deacetylase HDAC6 is a novel critical component of stress granules involved in the stress response. Genes Dev 2007;21:3381–3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Matthias P, Yoshida M, Khochbin S. HDAC6 a new cellular stress surveillance factor. Cell Cycle 2008;7:7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Wang JF, Bown C, Young LT. Differential display PCR reveals novel targets for the mood‐stabilizing drug valproate including the molecular chaperone GRP78. Mol Pharmacol 1999;55:521–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Bown CD, Wang JF, Young LT. Increased expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins following chronic valproate treatment of rat C6 glioma cells. Neuropharmacology 2000;39:2162–2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Chen B, Wang JF, Young LT. Chronic valproate treatment increases expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins in the rat cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48:658–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Shao L, Sun X, Xu L, Young LT, Wang JF. Mood stabilizing drug lithium increases expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins in primary cultured rat cerebral cortical cells. Life Sci 2006;78:1317–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Wang JF, Azzam JE, Young LT. Valproate inhibits oxidative damage to lipid and protein in primary cultured rat cerebrocortical cells. Neuroscience 2003;116:485–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Shao L, Young LT, Wang JF. Chronic treatment with mood stabilizers lithium and valproate prevents excitotoxicity by inhibiting oxidative stress in rat cerebral cortical cells. Biol Psychiatry 2005;58:879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Cui J, Shao L, Young LT, Wang JF. Role of glutathione in neuroprotective effects of mood stabilizing drugs lithium and valproate. Neuroscience 2007;144:1447–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Qi X, Hosoi T, Okuma Y, Kaneko M, Nomura Y. Sodium 4‐phenylbutyrate protects against cerebral ischemic injury. Mol Pharmacol 2004;66:899–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Vilatoba M, Eckstein C, Bilbao G, et al Sodium 4‐phenylbutyrate protects against liver ischemia reperfusion injury by inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum‐stress mediated apoptosis. Surgery 2005;138:342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Mulhern ML, Madson CJ, Kador PF, Randazzo J, Shinohara T. Cellular osmolytes reduce lens epithelial cell death and alleviate cataract formation in galactosemic rats. Mol Vis 2007;13:1397–1405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Bonapace G, Waheed A, Shah GN, Sly WS. Chemical chaperones protect from effects of apoptosis‐inducing mutation in carbonic anhydrase IV identified in retinitis pigmentosa 17. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:12300–12305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Yam GH, Gaplovska‐Kysela K, Zuber C, Roth J. Sodium 4‐phenylbutyrate acts as a chemical chaperone on misfolded myocilin to rescue cells from endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007;48:1683–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Vij N, Fang S, Zeitlin PL. Selective inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum‐associated degradation rescues DeltaF508‐cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator and suppresses interleukin‐8 levels: Therapeutic implications. J Biol Chem 2006;281:17369–17378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Ozcan U, Yilmaz E, Ozcan L, et al Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science 2006;313:1137–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Burrows JA, Willis LK, Perlmutter DH. Chemical chaperones mediate increased secretion of mutant alpha 1‐antitrypsin (alpha 1‐AT) Z: A potential pharmacological strategy for prevention of liver injury and emphysema in alpha 1‐AT deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97:1796–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Kubota K, Niinuma Y, Kaneko M, et al Suppressive effects of 4‐phenylbutyrate on the aggregation of Pael receptors and endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Neurochem 2006;97:1259–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. De Almeida SF, Picarote G, Fleming JV, Carmo‐Fonseca M, Azevedo JE, De Sousa M. Chemical chaperones reduce endoplasmic reticulum stress and prevent mutant HFE aggregate formation. J Biol Chem 2007;282:27905–27912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Kegel KB, Meloni AR, Yi Y, et al Huntingtin is present in the nucleus, interacts with the transcriptional corepressor C‐terminal binding protein, and represses transcription. J Biol Chem 2002;277:7466–7476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Ferrante RJ, Kubilus JK, Lee J, et al Histone deacetylase inhibition by sodium butyrate chemotherapy ameliorates the neurodegenerative phenotype in Huntington's disease mice. J Neurosci 2003;23:9418–9427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Gardian G, Browne SE, Choi DK, et al Neuroprotective effects of phenylbutyrate in the N171‐82Q transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease. J Biol Chem 2005;280:556–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Hockly E, Richon VM, Woodman B, et al Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, ameliorates motor deficits in a mouse model of Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:2041–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Ebbel EN, Leymarie N, Schiavo S, et al Identification of Phenylbutyrate‐Generated Metabolites in Huntington Disease Patients using Parallel LC/EC‐array/MS and Off‐line Tandem MS. Anal Biochem 2010;399:152–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Bachman DS, Butler IJ, McKhann GM. Long‐term treatment of juvenile Huntington's chorea with dipropylacetic acid. Neurology 1977;27:193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Pearce I, Heathfield KW, Pearce MJ. Valproate sodium in Huntington chorea. Arch Neurol 1977;34:308–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Symington GR, Leonard DP, Shannon PJ, Vajda FJ. Sodium valproate in Huntington's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1978;135:352–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Saft C, Lauter T, Kraus PH, Przuntek H, Andrich JE. Dose‐dependent improvement of myoclonic hyperkinesia due to Valproic acid in eight Huntington's Disease patients: A case series. BMC Neurol 2006;6:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Grove VE, Jr ., Quintanilla J, DeVaney GT. Improvement of Huntington's disease with olanzapine and valproate. N Engl J Med 2000;343:973–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Zadori D, Geisz A, Vamos E, Vecsei L, Klivenyi P. Valproate ameliorates the survival and the motor performance in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2009;94:148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Salazar Z, Tschopp L, Calandra C, Micheli F. Pisa syndrome and parkinsonism secondary to valproic acid in Huntington's disease. Mov Disord 2008;23:2430–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Thomas EA, Coppola G, Desplats PA, et al The HDAC inhibitor 4b ameliorates the disease phenotype and transcriptional abnormalities in Huntington's disease transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:15564–15569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Khan N, Jeffers M, Kumar S, et al Determination of the class and isoform selectivity of small‐molecule histone deacetylase inhibitors. Biochem J 2008;409:581–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Dokmanovic M, Perez G, Xu W, et al Histone deacetylase inhibitors selectively suppress expression of HDAC7. Mol Cancer Ther 2007;6:2525–2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Benn CL, Butler R, Mariner L, et al Genetic knock‐down of HDAC7 does not ameliorate disease pathogenesis in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington's disease. PLoS One 2009;4:e5747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Perez M, Santa‐Maria I, Gomez De Barreda E, et al Tau–an inhibitor of deacetylase HDAC6 function. J Neurochem 2009;109:1756–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Jiang Q, Ren Y, Feng J. Direct binding with histone deacetylase 6 mediates the reversible recruitment of parkin to the centrosome. J Neurosci 2008;28:12993–13002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Aiken CT, Steffan JS, Guerrero CM, et al Phosphorylation of threonine 3: Implications for Huntingtin aggregation and neurotoxicity. J Biol Chem 2009;284:29427–29436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Dephoure N, Zhou C, Villen J, et al A quantitative atlas of mitotic phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:10762–10767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Pardo R, Colin E, Regulier E, et al Inhibition of calcineurin by FK506 protects against polyglutamine‐huntingtin toxicity through an increase of huntingtin phosphorylation at S421. J Neurosci 2006;26:1635–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Rangone H, Poizat G, Troncoso J, et al The serum‐ and glucocorticoid‐induced kinase SGK inhibits mutant huntingtin‐induced toxicity by phosphorylating serine 421 of huntingtin. Eur J Neurosci 2004;19:273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Humbert S, Bryson EA, Cordelieres FP, et al The IGF‐1/Akt pathway is neuroprotective in Huntington's disease and involves Huntingtin phosphorylation by Akt. Dev Cell 2002;2:831–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Schilling B, Gafni J, Torcassi C, et al Huntingtin phosphorylation sites mapped by mass spectrometry. Modulation of cleavage and toxicity. J Biol Chem 2006;281:23686–23697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Daub H, Olsen JV, Bairlein M, et al Kinase‐selective enrichment enables quantitative phosphoproteomics of the kinome across the cell cycle. Mol Cell 2008;31:438–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Xia Q, Cheng D, Duong DM, et al Phosphoproteomic analysis of human brain by calcium phosphate precipitation and mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res 2008;7:2845–2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Brill LM, Xiong W, Lee KB, et al Phosphoproteomic analysis of human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2009;5:204–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Yanai A, Huang K, Kang R, et al Palmitoylation of huntingtin by HIP14 is essential for its trafficking and function. Nat Neurosci 2006;9:824–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Li H, Xing X, Ding G, et al SysPTM: A systematic resource for proteomic research on post‐translational modifications. Mol Cell Proteomics 2009;8:1839–1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]